Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Flight 232 approaching Runway 22 at Sioux Gateway Airport in Sioux City, Iowa, on July 19, 1989. (Photo: Gary Anderson/Sioux City Journal)

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Spencer, thank you for sharing your story with us. Let’s begin with what you remember. Do you have memory from that day?

SPENCER BAILEY: I don’t remember anything. It’s everything I’ve read or that people have told me. I was in a coma for five days. I was in a hospital bed for the first nine days after the crash, and only then was I able to kind of start moving around. I had such bad brain trauma, and my head was so swollen that my eyes were shut. Like, physically shut. And coming out of that coma was like a rebirth for me. Only instead of being born out of my mom, I was now a motherless child.

AZ: Your mother, of course, was one of those people who tragically didn’t make it through the flight.

SB: Right.

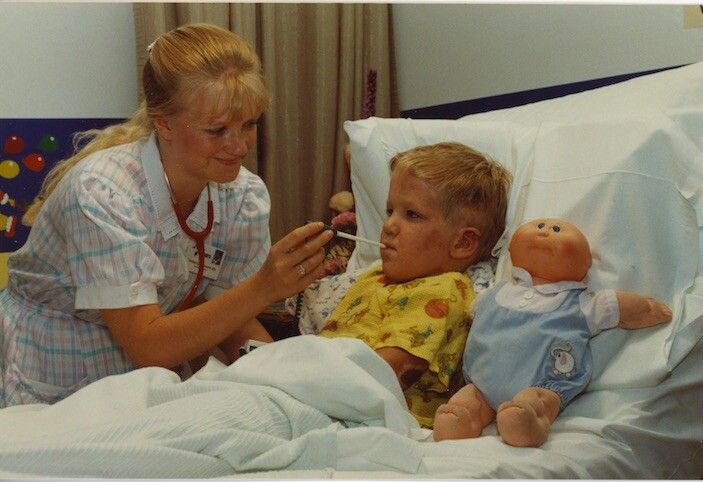

Spencer with a nurse at St. Luke’s Regional Medical Center in Sioux City, Iowa, in July 1989, after coming out of a coma.

AZ: Your older brother Brandon did [survive], and his experience was very different than yours.

SB: The only way that I know anything that happened [on the flight] is through my brother Brandon, and I could never do justice to tell his story here. But he remembers a lot of what happened. And, of course, I’ve read about it. I know a lot of the technical things that happened through finding articles online, reading about the [National Transportation Safety Board] investigation that happened after the crash.

AZ: There was a book, there was a TV movie [called A Thousand Heroes and starring Charlton Heston], there’s been a lot of media around it.

SB: Yeah, there was a book that came out a few years ago by a journalist Laurence Gonzales. I didn’t participate in any interviews for that book, but there were things that I read in that book that I actually didn’t know about. I remember, when I was reading that book, getting chills learning about the woman who found my body. It was an out-of-body experience, actually, to read about my little three-year-old body being found in the wreckage. I actually had to put the book down. It was the first time that it felt really real for me. Because for a long time it never felt real. It did feel like it was somebody else.

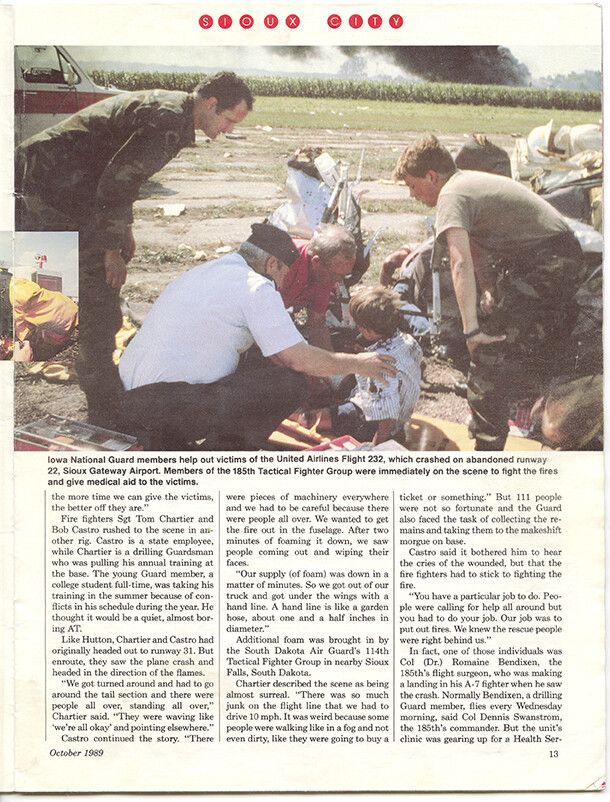

As seen in the October 1989 issue of National Guard, a photograph of rescue workers helping Brandon Bailey, with both of his legs broken, on the runway.

AZ: What did Brandon teach you about what happened that day?

SB: Well, there’s a certain humility involved in learning his experience, which was far beyond anything that I went through. He remembers everything.

About eleven years ago—he was living in Austin, Texas, at the time—I flew down to see him. And me being a nerdy journalist, I had a tape recorder [with me], and I asked him if I could interview him about the crash. We had never talked about it formally. We had dealt with the aftermath as brothers growing up together, but we had never formally talked about it.

I asked him about that day, and he shared his story with me. Which included some really haunting details, like, as the plane was going down, our mom had her arms around the back of us. Almost like an angel or something. And when it crashed, everything for him just went gray. I’m sure it was pretty similar for the rest of us in that section of the plane, which was toward the back—row 33. He didn’t go unconscious. He woke up on the runway with his legs broken. A six-year-old boy, thinking if he could flip his legs around, he could get up and walk away. Almost like if it were a video game. Because that’s what a six-year-old’s imagination does. His recovery was much longer than mine. His physical injuries were much worse than mine.

I had brain and head trauma that was very severe, but my body actually was extremely resilient, so my worst injuries were brain injuries. Physically, my only issue that I had was my left ear, which had almost been sliced off and had to be stitched back on.

A National Transportation Safety Board inspector looks at the rear engine mount of Flight 232 two days after the crash. (Photo: Ed Porter/Sioux City Journal)

AZ: Did Brandon know that he had lost his mother at the moment that he had woken up?

SB: I think so. I mean, according to the reporting in Laurence Gonzales’s book. That [question] wasn’t a part of our interview, so I actually don’t know for sure. But I know that he remembers our mom and has memories that I don’t have. And I know that he was much more aware of what death meant than I was. So that whole experience for him is a whole different kind of trauma than what I’ve gone through.

AZ: There were one hundred eighty-four people who survived that extraordinary crash. How did that happen? When you see the footage, you couldn’t imagine that anyone would have survived that crash.

SB: I feel like every single survivor on that plane is indebted to those who were in the cockpit. Especially Capt. Al Haynes. Now, in more recent times, people know “Sully” Sullenberger, but Capt. Al Haynes was also a miracle-maker, back in 1989. And I would not be sitting in this chair right now, I would not have started this company with you or be where I am, were it not for that man. I’ll be forever grateful to him.

“I would not be sitting in this chair right now, I would not have started this company with you or be where I am, were it not for [Capt. Al Haynes]. I’ll be forever grateful to him.”

It really is a miracle when you understand the mechanics of what happened that day. Which starts with an aluminum part that Alcoa made for a General Electric [CF6] engine. It was a faulty metal part that ended up in this engine, which was placed in a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 plane, later sold to United and in use from 1973 until the crash in ’89. I believe it was around 17,000 cycles, or flights, until this incident happened. To think about the odds, and to think about what a small crack in a metal part could do as it expands and gets worse, to the point that it explodes in the air above Iowa and sends shards through the hydraulics lines of the plane, which control the steering—the fact that they even got near a runway to land the jet is a miracle. The fact that people survived even more so.

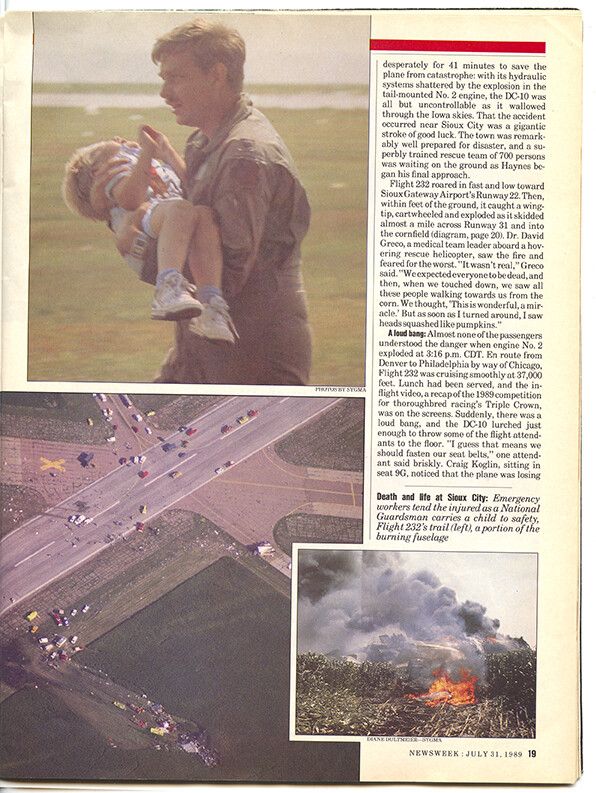

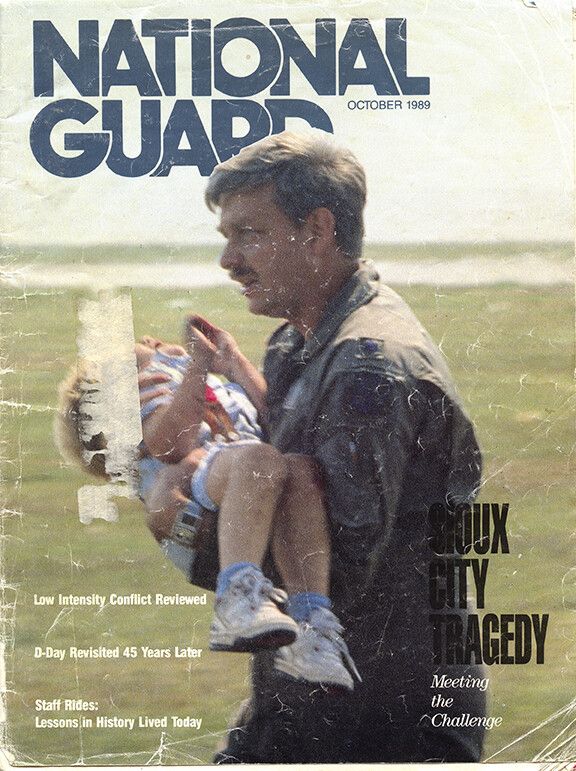

The famous photograph of Lt. Col. Dennis Nielsen carrying then-3-year-old Spencer Bailey after the crash-landing of United Airlines Flight 232. (Photo: Gary Anderson/Sioux City Journal)

A page inside the July 31, 1989, issue of Newsweek featuring the Anderson photo.

AZ: There’s a famous photograph that was taken by Gary Anderson that shows [Lt. Col.] Dennis Nielsen carrying you, the unconscious three-year-old boy at the time, from the wreckage of the DC-10. The image became kind of a symbol of the heroic rescue effort that happened. But just moments before that image, Dennis Neilsen wasn’t actually the person that pulled you out. Tell me about what happened once the plane had crash-landed into the cornfield. It did a cartwheel …

SB: Well, it appeared to do a cartwheel; it actually wasn’t a cartwheel. But the plane landed on a tilt, and it’s right wing went into the ground, which catapulted the plane forward and it rolled and broke into several parts. I was in row 33, so we were in the back section of the plane, and we were flung forward. When my brother woke up on the runway, my mom was not in sight, I was not in sight.

AZ: Where were you?

SB: In some part of the fuselage. Somewhere. And I’ve never heard the story of how Lt. Col. Dennis Nielsen ended up being the person carrying me—basically, the story behind that photograph. But when I read Laurence Gonzales’s book [Flight 232], there is a scene where this woman, Lynn Hartter, finds my body in the wreckage, and she tells that she heard a sound. Which couldn’t have been my sound, because I was in a coma, but nonetheless she heard a sound. And so, not only am I grateful to the rescue crew and pilots and the captain, but also this woman, who, without her, I don’t know how soon they would have found my body.

The October 1989 cover of National Guard magazine featuring the Anderson photo.

AZ: From that story, Ms. Hartter finds you in the wreckage, pulls you out, and hands you off to Dennis Nielsen. And Gary Anderson is on a telephoto lens, far away from the scene, and makes a seminal photograph that winds up on the front page of all the newspapers globally. How does your father find out about what had happened?

SB: He was getting on the first flight he could to Des Moines, and then renting a car and driving to Sioux City. He had to connect through St. Louis, and, as I understand it, by the night of July 19th, he had received a call from the hospital [St. Luke’s Regional Medical Center], and there was a boy there that the doctors were describing as “Randy,” but it was actually Brandy, which is what we called Brandon when we were little. He matched the description of Brandon. So my dad knew that Brandon had made it and was in really bad condition.

He found out about the photograph, actually, when he was connecting in St. Louis. He had had a phone call with my great uncle Don, who I believe was on a business trip in Austin, Texas, at the time; had seen the picture on the front page of the paper; and told him, “I believe that’s Spencer.” Because [the paper] hadn’t labeled me—they didn’t know who I was. I was just a little boy who had survived. My dad went by a newsstand at the airport and saw the photo of me, and he told me he just had a feeling in his gut that I had made it. He kind of assumed that, on some level, they wouldn’t have put a photo of a dead boy on the cover of the newspaper.

AZ: Was he aware at this point that his wife may not have made it?

SB: I think he had a feeling in his gut that she had not. But I guess I’d leave that for my dad to say.

AZ: And was Trent with him?

SB: Trent stayed with family on the East Coast. We reunited about a month later at our fourth birthday.

AZ: So Trent was not at your mother’s funeral?

SB: No, Trent was. Trent and I were both at my mom’s funeral. And we didn’t really know what it was. We were two four-year-old kids playing around. I had tons of scabs all over me from the crash, and I was asking my dad to itch my scabs. [Laughs] And Brandon was still in the hospital. He couldn’t be there.

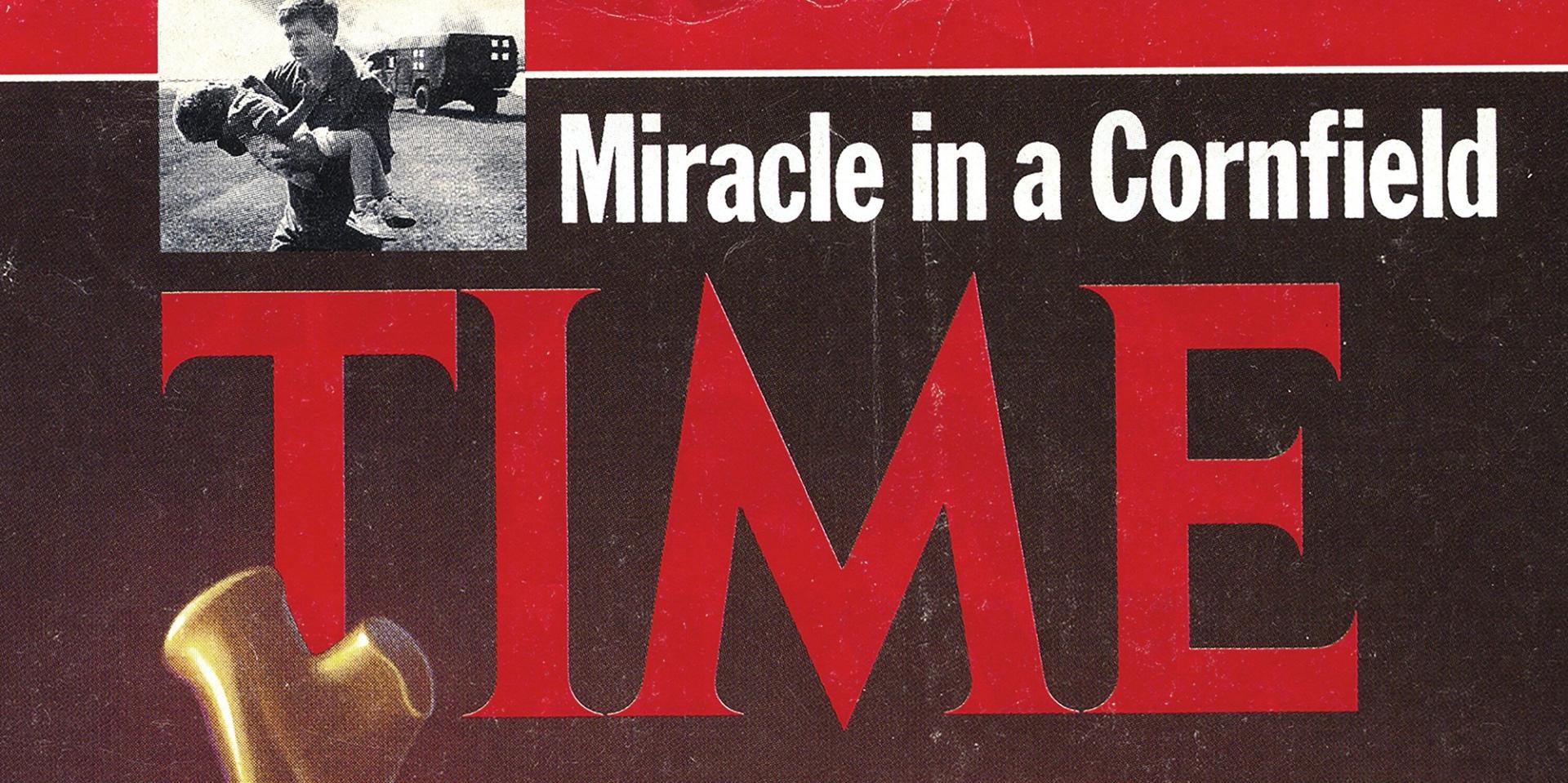

The July 31, 1989, cover of Time featuring the Anderson photo.

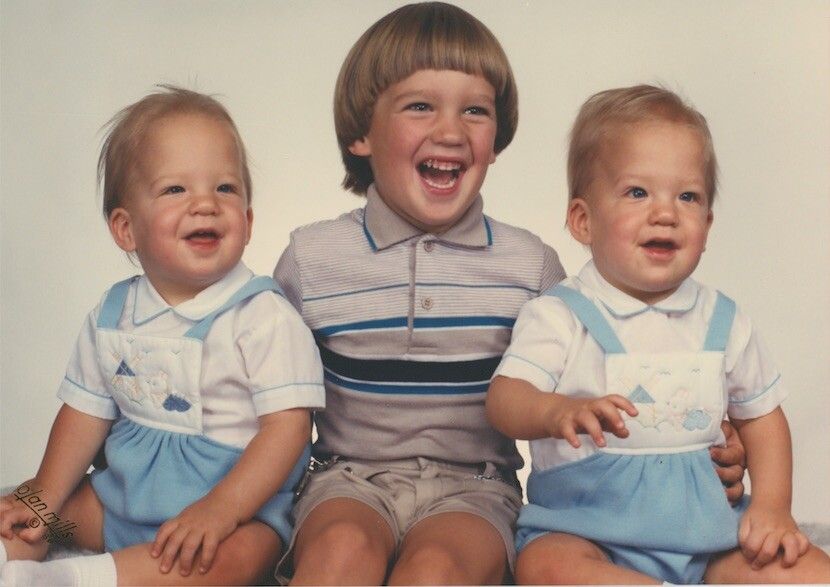

The three Bailey brothers with their mother, Francie, on a “runway” at a mall in Colorado in the late 1980s, modeling children’s clothing of her design.

AZ: Tell me about your mother—what you know about her, who she was.

SB: It’s all secondhand story—from family, from friends of hers. My godmother [Karen Hatt] was her best friend. So I’ve heard stories from her.

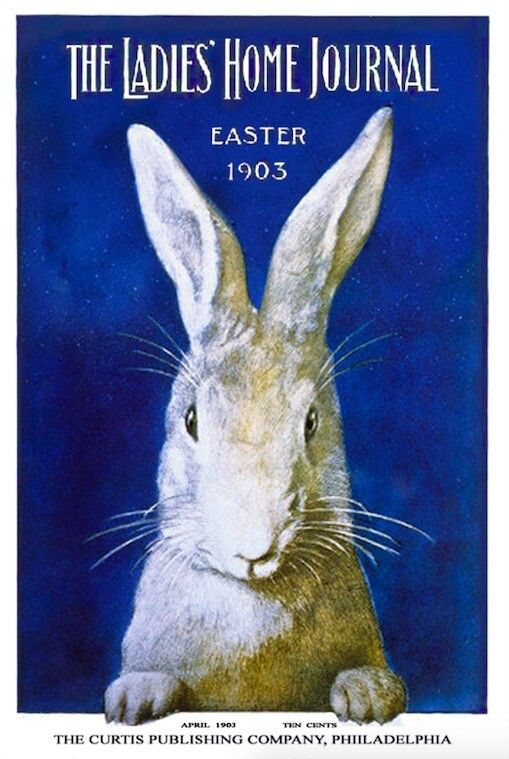

My mom was an artist and also designed some childrens’ clothes. There’s a photo of us in a suburban mall in Littleton, Colorado, modeling her clothes down a runway. [Laughs] She was just somebody who had so much creativity inside her, and I think it came from family. I mean, her grandfather [Herbert M. Kieckhefer] was an inventor. Her great grandfather—my namesake, Frank Spencer Guild—was a painter who at the turn of the twentieth century was the art director for Ladies’ Home Journal. So there was art and creativity and invention and engineering in the family.

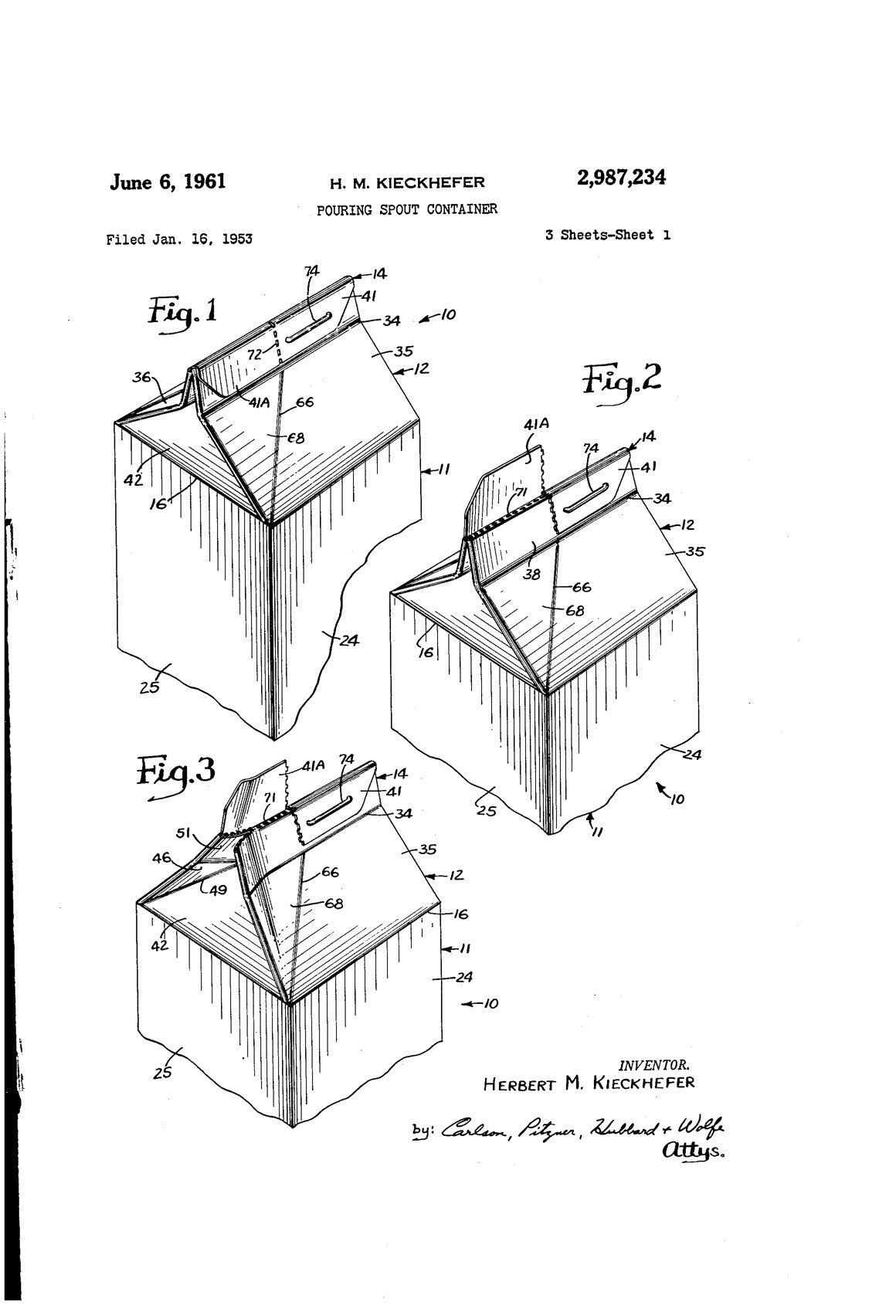

AZ:One of the great inventions, of course, was the cardboard milk spout.

SB: Yeah, well, that was one of several that sort of—I can’t say that my great grandfather invented it, per se, but he did create an iteration of it that is one of the main patents for it, developed a bunch of different cardboard inventions. I know that my mom really tried to instill this creativity in us, because there’s photographic evidence of us painting and drawing and doing creative things from when she was still with us.

The cover of the Easter 1903 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, painted by Spencer’s great-great grandfather and namesake, Frank Spencer Guild.

AZ: Yeah, and when a family loses the sort of matriarch—how did you four boys pull it together?

SB:Three boys.

AZ: Well, your father.

SB: [Laughs] Fair.

AZ: This is a family with a lot of male energy.

SB: Yeah.

AZ: And you think about the aftermath of trauma like this—what do you think happens when the female energy gets pulled out of the family?

SB: [Long pause] I’m still coping with that question. It’s so … [pauses] … so hard to answer that. Like, I feel like I just got punched in my gut trying to even find an answer to that, because the void—the weight of that void—is so big that probably even in thirty years from now I’ll still be wondering what it’s like to have that.

There is a reason, I think, that as I’ve gotten older in my adult life I have become friends with a lot of strong older women. One of my chief mentors early on in my career was Kate White, who is the former editor-in-chief of Cosmo, and I’ve become really close with several other people in the design world and architecture world who are also these really strong women who are kind of, on some level, who I imagined my mom to be. In a way, it has been a constant searching for Mom, knowing that she’s never coming back.

AZ: Yeah.

SB: I think I realized that pretty quickly. It took me a few years to understand what death was. I mean, I had my head trauma injuries to deal with, let alone trying to comprehend what death was. But I think probably around five or six—within a couple of years I understood that she was gone. That she wasn’t coming back.

I did see a child therapist as a kid, and that, I think, also really, really helped. Probably from within a couple years after the crash until I was eleven or twelve, I was seeing this therapist who definitely helped me work through a lot of that trauma.

You grow up fast in a situation without a parent, maternal or paternal. You just grow up fast. By the time I was seven or eight, I was doing my own laundry, making do, helping clean the house, contributing, doing what you could.

A patent filing for a pouring-spout container by Spencer’s great grandfather, Herbert M. Kiekhefer, who was an inventor of cardboard and paper products.

AZ: Your father, who I’ve been fortunate to spend some time with, talks about that period as just, “Well, things changed in a moment, and I had to get it together and run a household.”

SB: Yeah, and it took him some time. And I don’t think it was ever fully “together.” We were a broken house.

By the time I reached thirteen, I kind of convinced my dad it was a good idea to send me to boarding school. With Trent. We had collectively sort of convinced him of this. And Brandon, who had become an incredible athlete—that’s worth noting. He defied all expectations or childhood taunts or any assumption that the boy who had his legs destroyed was never going to be able to walk or run again. He became a Division I athlete. So, he had already gone off to a top school [Loomis Chaffee in Windsor, Connecticut], and I think Trent and I kind of saw an opportunity to be independent—to, I think, separate ourselves, too. We ended up going to different schools [Spencer to Pomfret in Pomfret, Connecticut; Trent to Kent in Kent, Connecticut]. We had grown up being identical twins, and had been kind of this unit. I think it was a way to get out of the house. Not to run away from Dad by any means, but to actually kind of open up a new life for him, too. I think it was—for a thirteen-, fourteen-year-old—a really mature decision.

It also came, in part, having to do with my injury. Growing up, I had a really hard time reading. I actually had to spend a lot of time to learn how to read across the page. And then, I’d be able to read, but I couldn’t actually comprehend what I was reading. It wasn’t until I was probably in seventh or eighth grade that I actually became able to read at a level that was similar to my peers.

Francie, in Colorado in 1985, pregnant with Spencer and Trent.

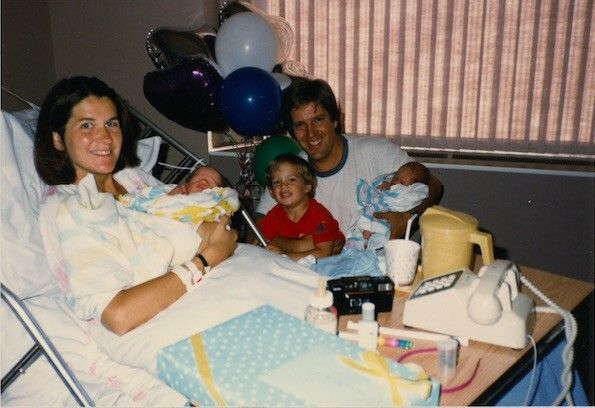

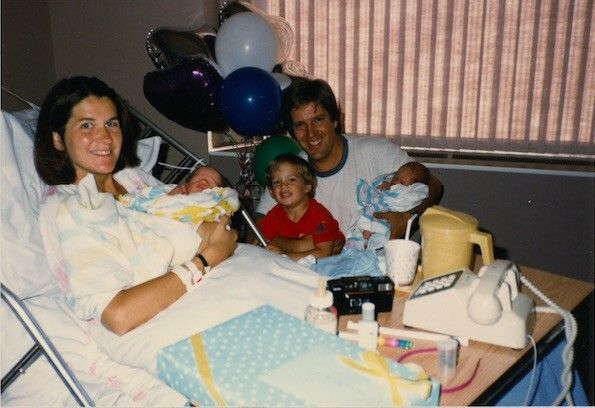

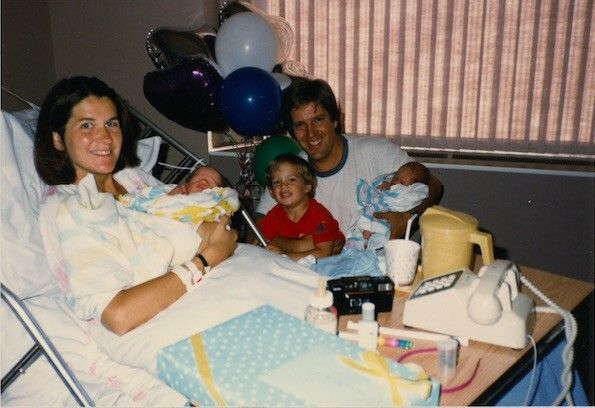

At the hospital in Denver after the birth of Spencer and Trent.

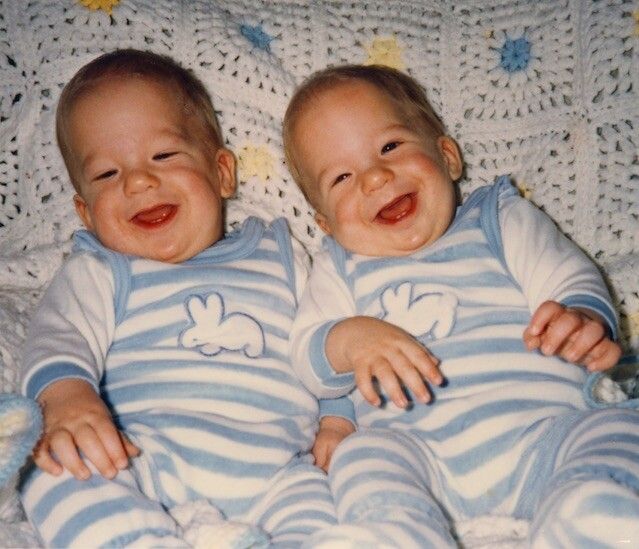

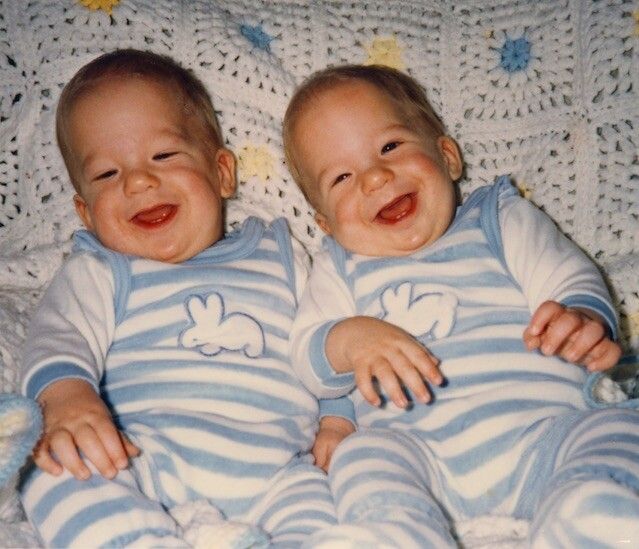

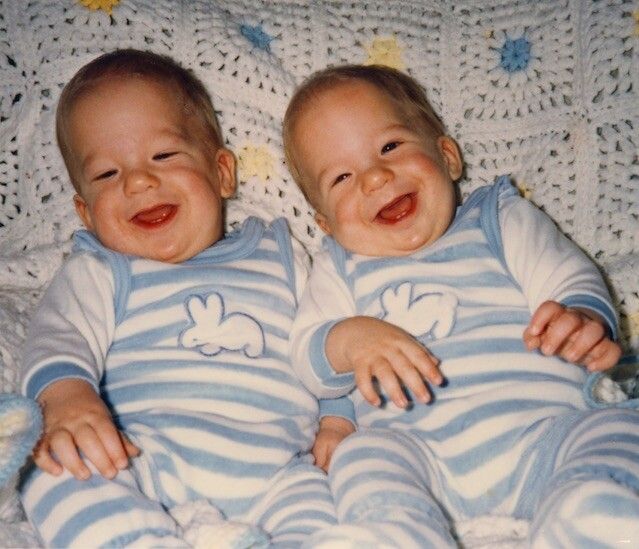

Spencer and Trent in 1985.

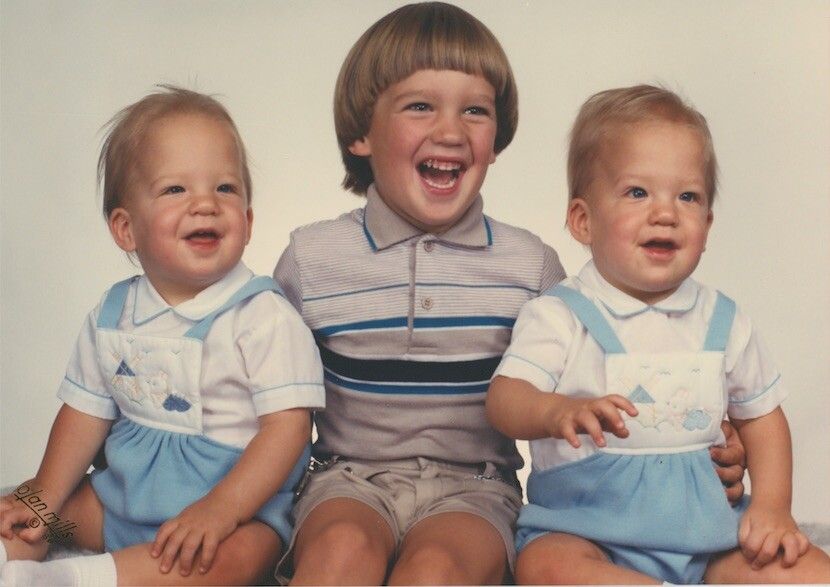

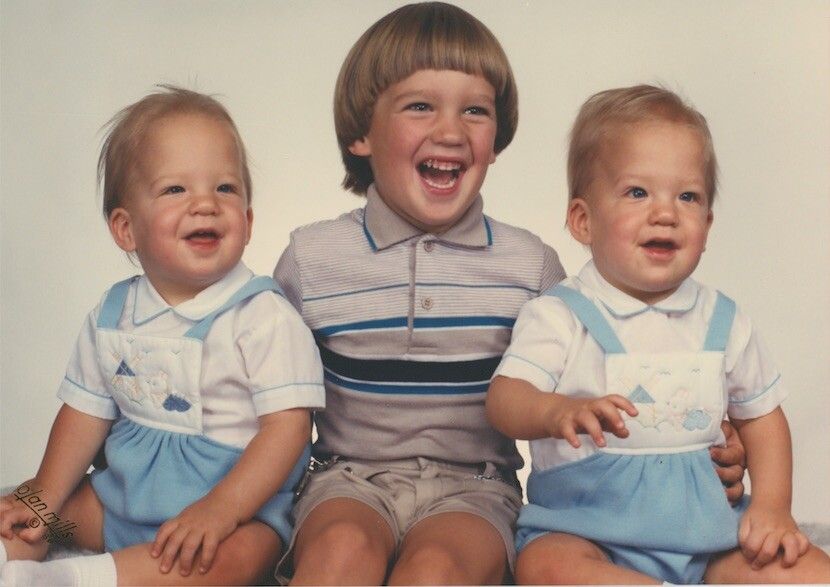

From left, Trent, Brandon, and Spencer.

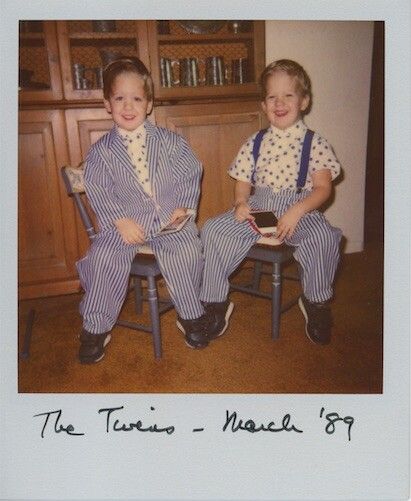

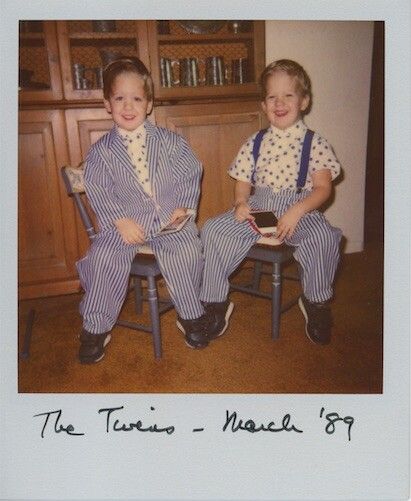

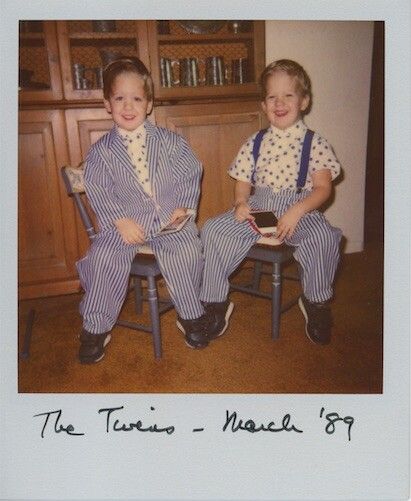

A Polaroid of Spencer, right, and Trent in March 1989, four months before the crash of Flight 232.

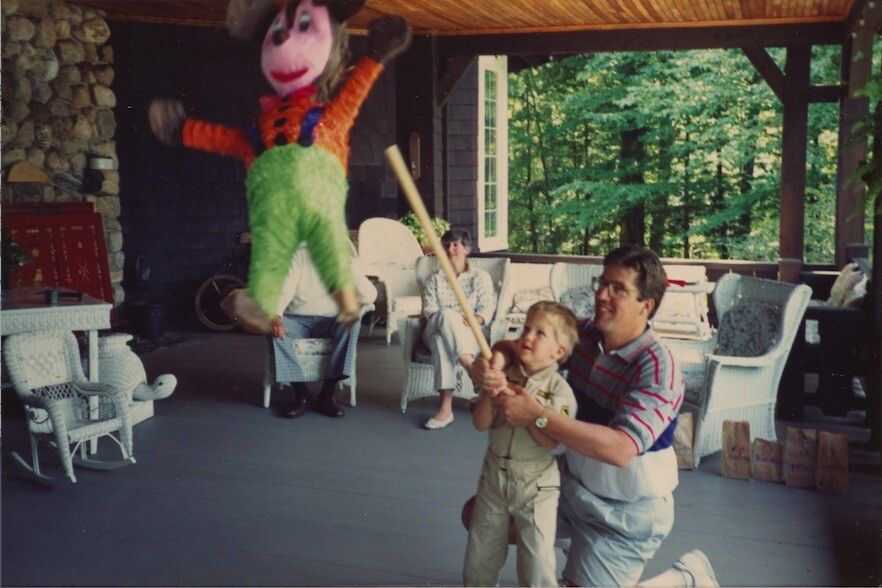

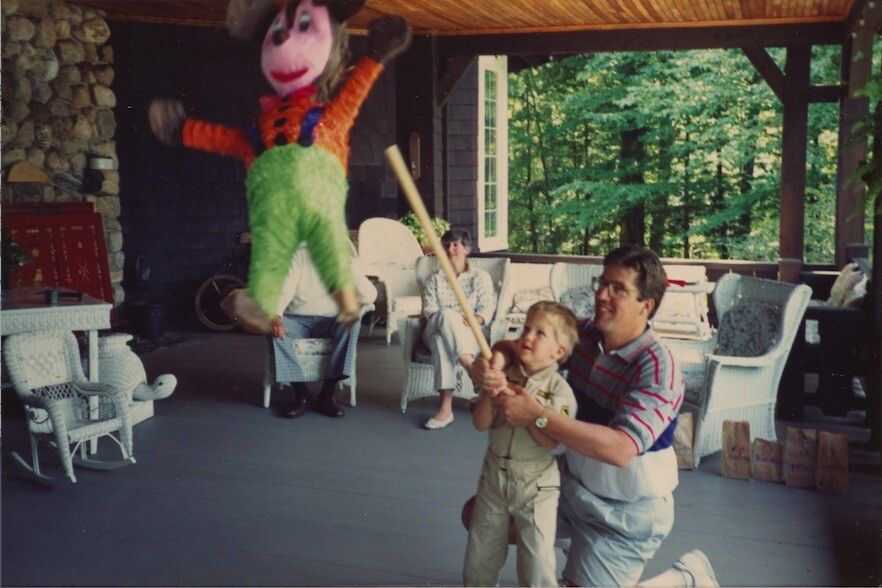

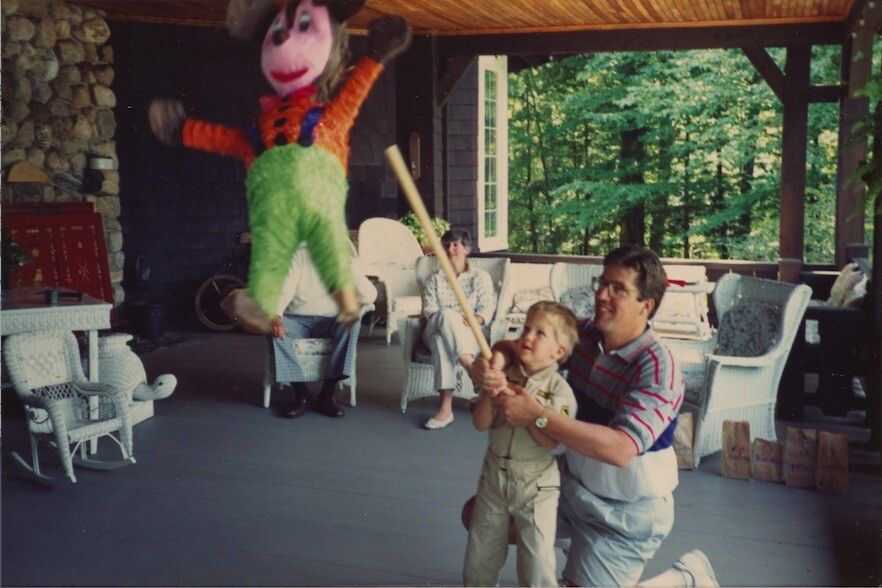

Spencer and his father in Lake Placid, New York, breaking open a piñata on his fourth birthday in August 1989.

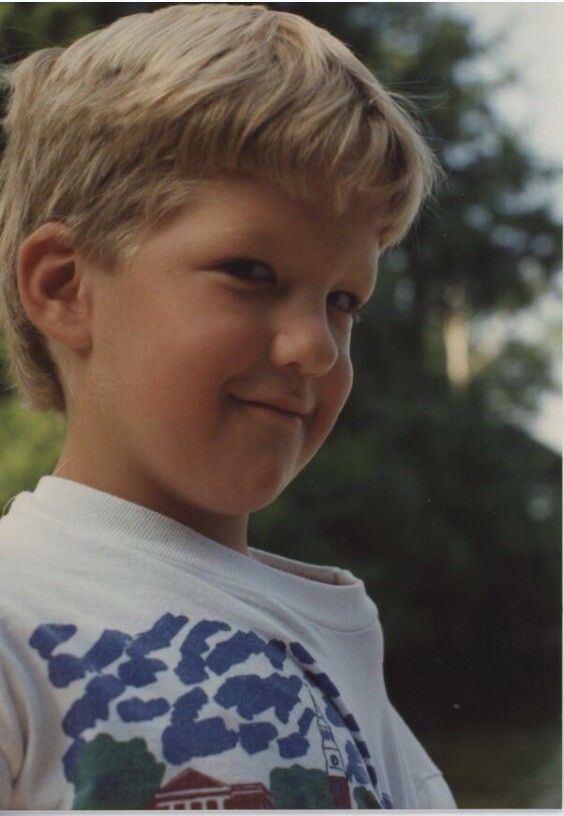

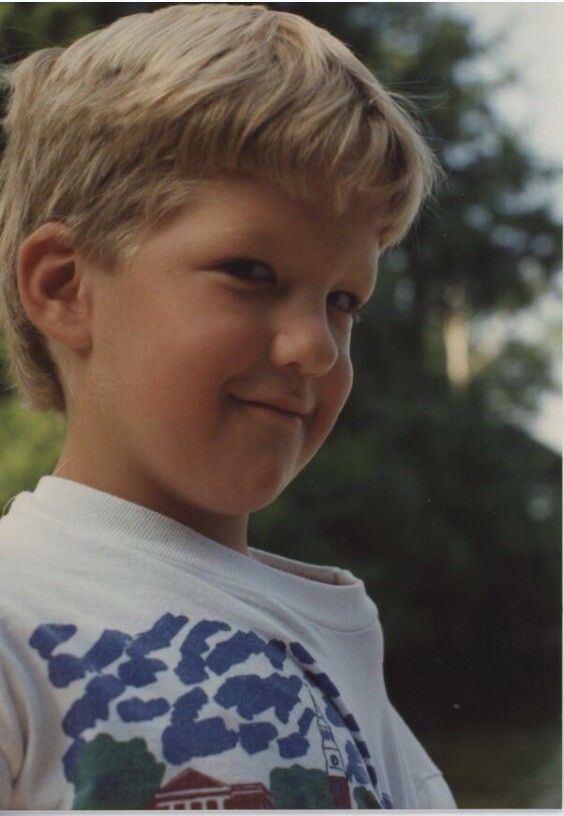

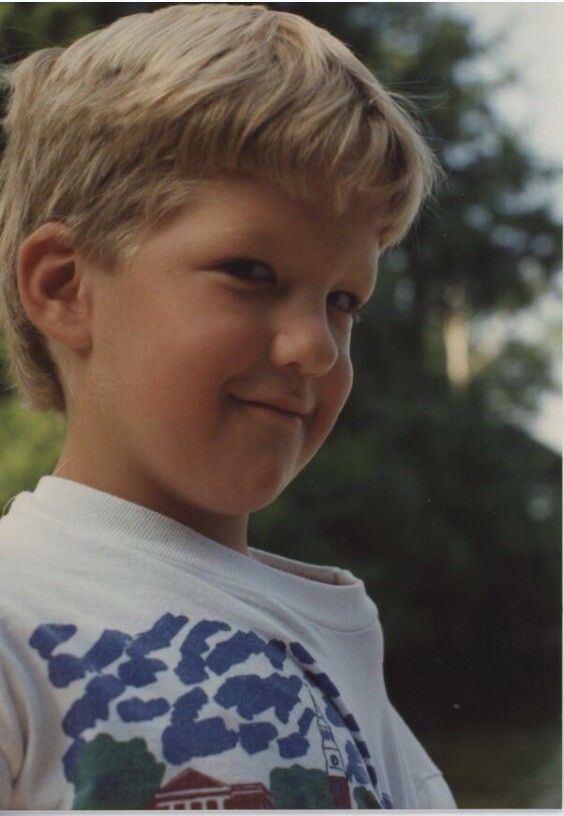

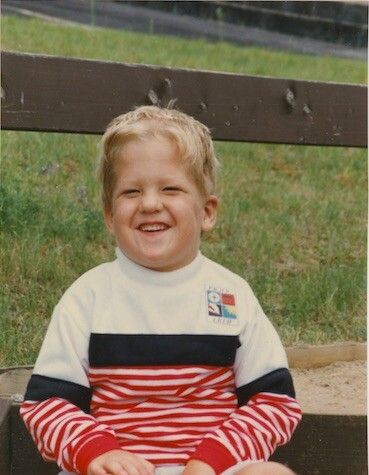

Spencer, age 5.

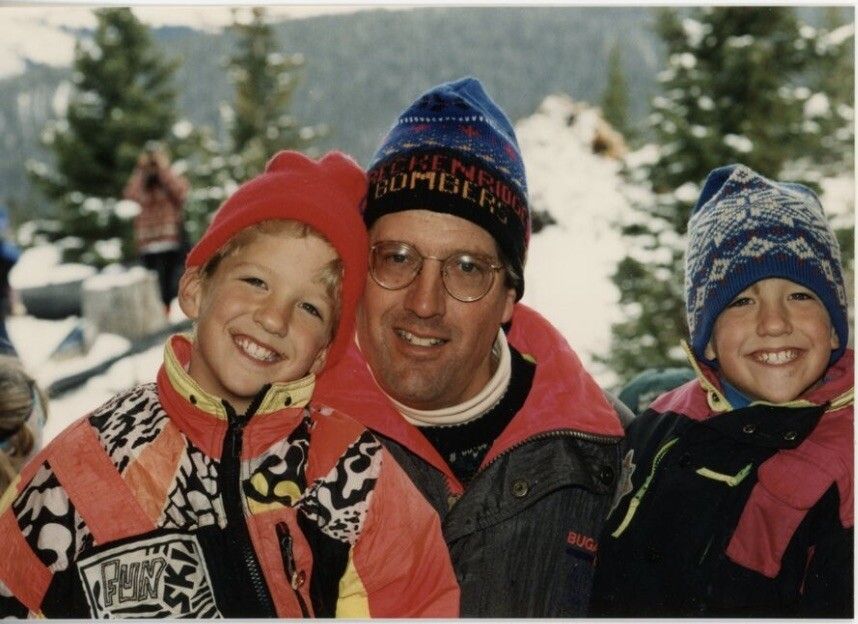

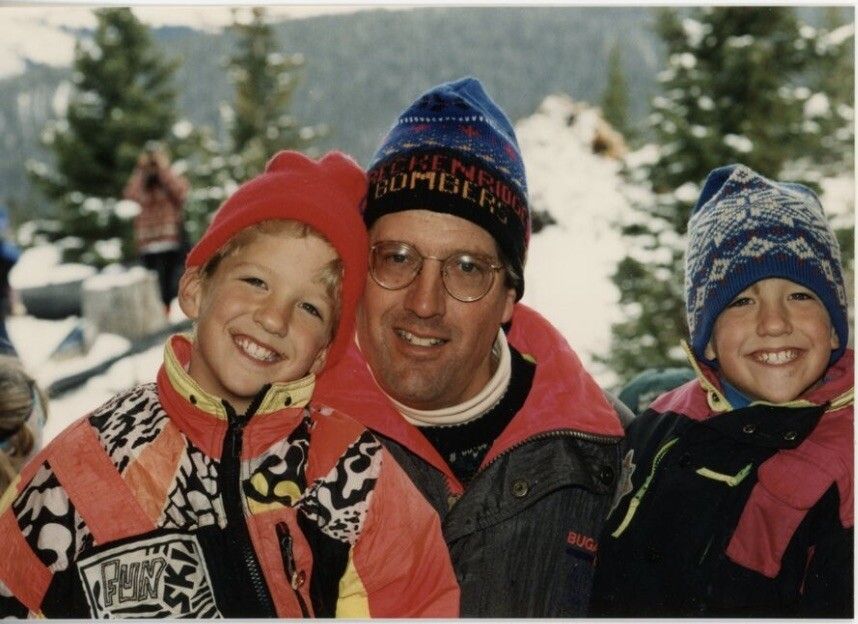

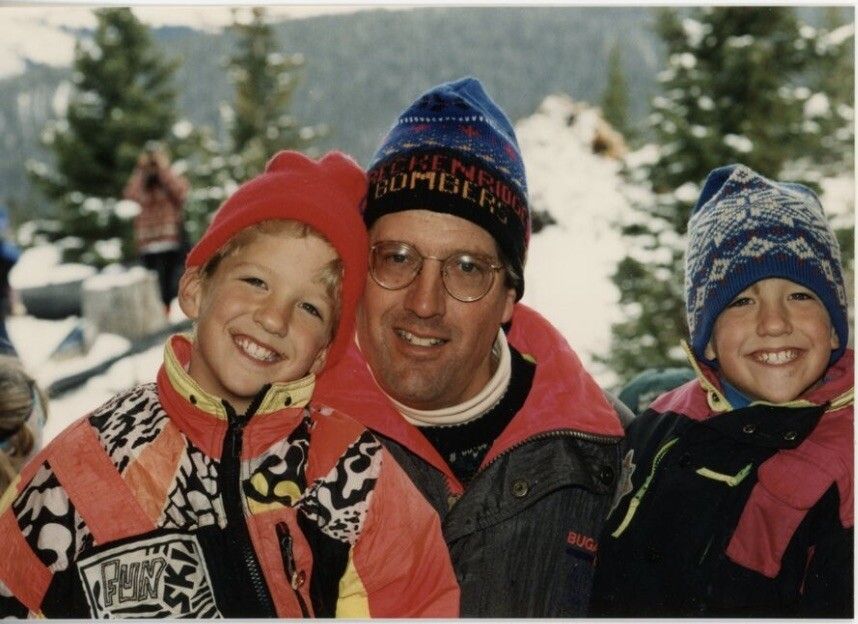

Spencer, at right, with his father, Brownell, and twin brother, Trent, in the early 1990s in Breckenridge, Colorado.

Francie, in Colorado in 1985, pregnant with Spencer and Trent.

At the hospital in Denver after the birth of Spencer and Trent.

Spencer and Trent in 1985.

From left, Trent, Brandon, and Spencer.

A Polaroid of Spencer, right, and Trent in March 1989, four months before the crash of Flight 232.

Spencer and his father in Lake Placid, New York, breaking open a piñata on his fourth birthday in August 1989.

Spencer, age 5.

Spencer, at right, with his father, Brownell, and twin brother, Trent, in the early 1990s in Breckenridge, Colorado.

Francie, in Colorado in 1985, pregnant with Spencer and Trent.

At the hospital in Denver after the birth of Spencer and Trent.

Spencer and Trent in 1985.

From left, Trent, Brandon, and Spencer.

A Polaroid of Spencer, right, and Trent in March 1989, four months before the crash of Flight 232.

Spencer and his father in Lake Placid, New York, breaking open a piñata on his fourth birthday in August 1989.

Spencer, age 5.

Spencer, at right, with his father, Brownell, and twin brother, Trent, in the early 1990s in Breckenridge, Colorado.

“It was a weird thing to be labeled a ‘survivor.’ I struggled with it.”

AZ: Of course you had all these challenges, both from the injury but also as you were developing your identity. Did you feel like you were kind of marked? Like everyone knew that you were the kid from the plane crash?

SB: Yeah, I did, and it was a weird thing to be labeled a “survivor.” I struggled with it. There were years in my teens—probably twelve, thirteen—that I had very bad self-confidence, and I kind of, at moments, probably even felt, wrongly, pathetic. And I don’t know why. I don’t know what caused me as a thirteen-year-old to feel that way, but I did, and a lot of that, I think, stemmed from this: Am I going to spend the rest of my life being that little boy in the photograph? That little boy in the statue? I think it was actually that feeling that led me to trying to figure out: What am I going to do with my life? What am I passionate about? What am I good at?

AZ: You wanted to become something other than the boy in the statue.

“I feel like I can now own the story in a way that ten years ago I couldn’t, because ten years ago I was still the little boy in the photograph.”

SB: Exactly. And I didn’t know what that “other than” was. It’s turned out to be a journalist, writer, editor.

AZ: But it had to be something. And it could have been something outside of writing, journalism, whatever it was. You needed to transcend, and you needed to move on, into another identity in a way.

SB: To get away from it. It’s kind of how I feel comfortable talking about it right now. Because I feel like I can now own the story in a way that ten years ago I couldn’t, because ten years ago I was still the little boy in the photograph.

From left, Lt. Col. Dennis Nielsen, Trent, Brownell, Brandon, and Spencer at a press conference on July 19, 1990, one year after the crash. (Photo: Mark Fageol/Sioux City Journal)

AZ: Did you hide it as a kid? When you went to boarding school, did you not reveal it?

SB: Yeah, only my best friends knew. And then, to graduate my high school, you had to give a senior speech. It was my girlfriend at the time who actually convinced me to do that. It felt so freeing. It was the first time I had publicly shared the story to any audience. And it was three hundred fifty students and—

AZ: Who had no idea.

SB: Yeah, the room was silent.

AZ: You kept it a secret, in a small boarding school, with tons of gossip? No one knew that story?

SB: Very few [people].

AZ: You had good friends.

SB: [Laughs] Yeah, apparently. And it was an interesting day, actually. The speech right before me was a woman [Sarah Vaillancourt] who went on to play ice hockey at Harvard and was an incredible player. Won Olympic Gold before graduating high school. And she got up to the stage and put her gold medal in the air and her head down and started crying, and I’m like, “Really?! I have to follow that?” [Laughs] And then I go tell my story. And my buddy Jon [Doodian] was third in line. I felt especially bad for him.

AZ: Yeah, following those two. What’d Jon talk about?

SB: I don’t remember. Sorry, Jon. [Laughs]

AZ: [Laughs] We mentioned for a moment this famous image became this memorial, a bronze statue, that’s still there. Did you visit it? How’d it make you feel when you saw it for the first time? What was that experience like? What’d you imagine people were seeing when they looked at it?

From left, Capt. Al Haynes, Brandon, Spencer, Lt. Col. Dennis Nielsen, Trent, and Brownell at the 1994 dedication of the Flight 232 memorial in Sioux City, Iowa. (Photo: Courtesy Sioux City Journal)

SB: I did not see myself in that statue.

We went to the inauguration of the memorial, which I believe was in 1994, and I was such a confused nine-year-old boy. But I’d grown—I’d grown up. Dennis Nielsen was there, and we tried to redo the— [Laughs]

AZ:He couldn’t lift you?

SB: He couldn’t lift me. I was too big. [Laughs] But it made for a good laugh anyway. And I think that’s important. There is some levity in the darkness.

AZ: Of course.

SB: We never went back after that at least for another probably ten years, maybe five years. The last time I went back was with my dad, in 2009. The year before, the Sioux City Journal had done a story on the anniversary of the crash, and I was asked about how I felt about seeing myself in statue. Actually, I think I would still say the same answer today, which is: I’m sure oftentimes people go back and look at that statue, and think that I’m a dead boy. They probably don’t realize I’m still alive.

“If you’re alive in the world, at some point in time you deal with trauma. It doesn’t matter the magnitude of the trauma. You deal with it. We’re all dealing with it right now.”

AZ: Yeah. It’s interesting how you say you don’t recognize yourself in that, and in essence that’s the purpose of good art. The photograph is an extraordinary piece of art, and the statue is a kind of three-dimensional rendition of that. But it isn’t about Spencer; it’s about all the survivors.

SB: Exactly.

AZ: And Dennis Nielsen, from everything I’ve read, is such an extraordinary human being. With having zero hubris, he sort of thinks of himself as the person who represents all of the rescuers.

SB: In a way. I mean, yeah, with zero hubris. He was even asked what saved me, and he said, “God did. I just carried him.”

AZ: Do you think that there’s a connection in some way between trauma and empathy?

SB: Totally. It’s why I became a journalist. Journalism requires deep empathy, if you’re good at it. And I love profile writing. I love telling other people’s stories. It’s probably why I haven’t gone and tried to tell this story. I realized—probably in high school, around the time I wrote that speech—that this is just my story to tell. Everybody has a story. If you’re alive in the world, at some point in time you deal with trauma. It doesn’t matter the magnitude of the trauma. You deal with it. We’re all dealing with it right now. Climate change. I don’t need to talk about politics, but that’s trauma. And I think when people realize that—that your situation isn’t that unique, that everybody deals with it—it opens up this thing inside of you, empathy, and allows you to think about trauma as something that everybody experiences, and that they all have their own versions of that story. There are so many stories out there that are similar to this one, even if they don’t have the graphic nature of the plane crash.

The memorial statue depicting Spencer and Lt. Col. Dennis Nielsen in Sioux City, Iowa. (Photo: Patrick Cunningham/Flickr)

AZ: And the image following it.

SB: I think about—just taking the picture of Lt. Col. Dennis Nielsen carrying me. After what happened at the Boston Marathon [bombing in 2013]. That was a famous picture, too. The young man [Jeff Bauman], who had lost his legs, being pushed in a wheelchair by a guy in a cowboy hat. The second I saw that picture, I thought of the one from Flight 232, because they’re totally different events, but the iconic nature of that image is what sticks in peoples’ minds. It represents that event. I wasn’t in Boston. I can’t grasp what happened that day. But the small semblance of what I can grasp comes through that picture.

AZ: Yeah, and empathy really is the ability to stand in somebody else’s shoes. It isn’t sympathy. It isn’t feeling sorrow for someone. It’s without judgement. Sorrow and sympathy have a kind of judgement involved. There’s almost a patronizing nature, in certain ways. But empathy is nonjudgemental, is neutral—you’re standing in the shoes of the other.

The reason I wanted to bring this up with you: I’m wondering if the fact that this experience is with you—it’s been with you for thirty years, but you don’t remember it. In a way, you had to develop an empathic way of dealing with it, even to understand it for yourself. You had to sort of stand in your own shoes.

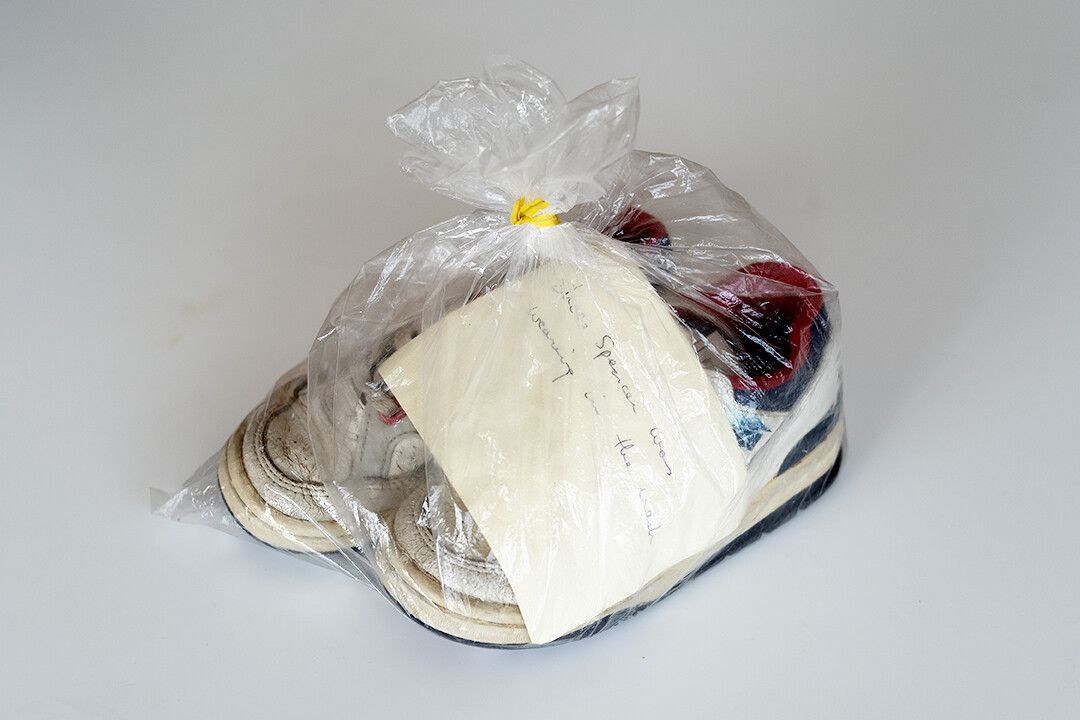

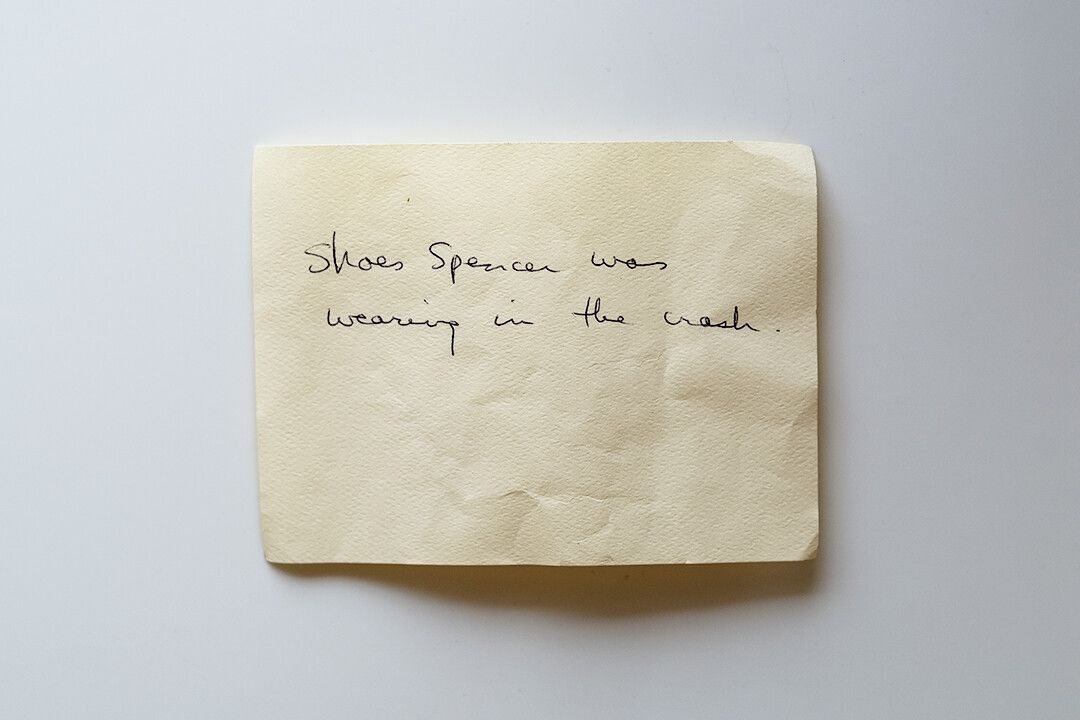

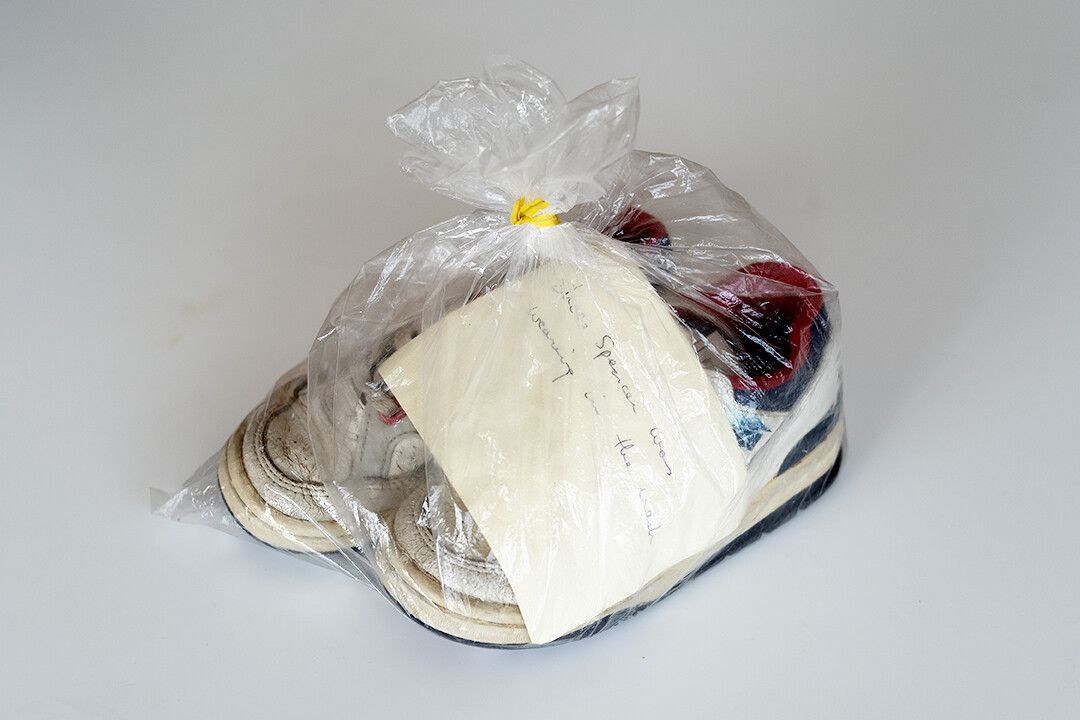

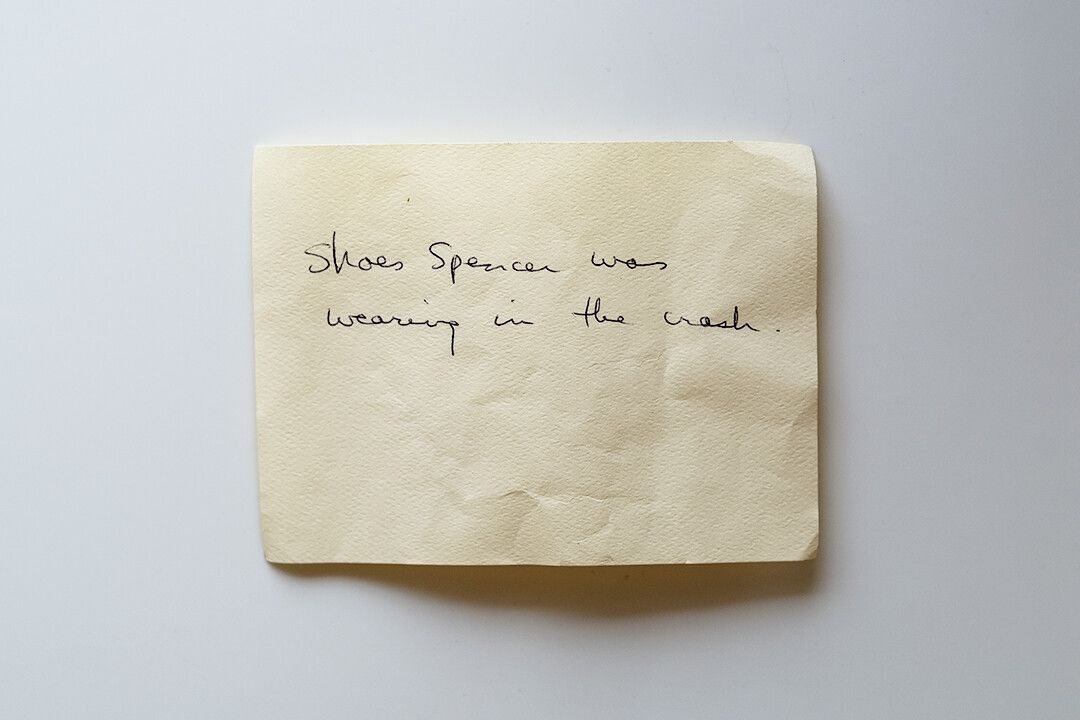

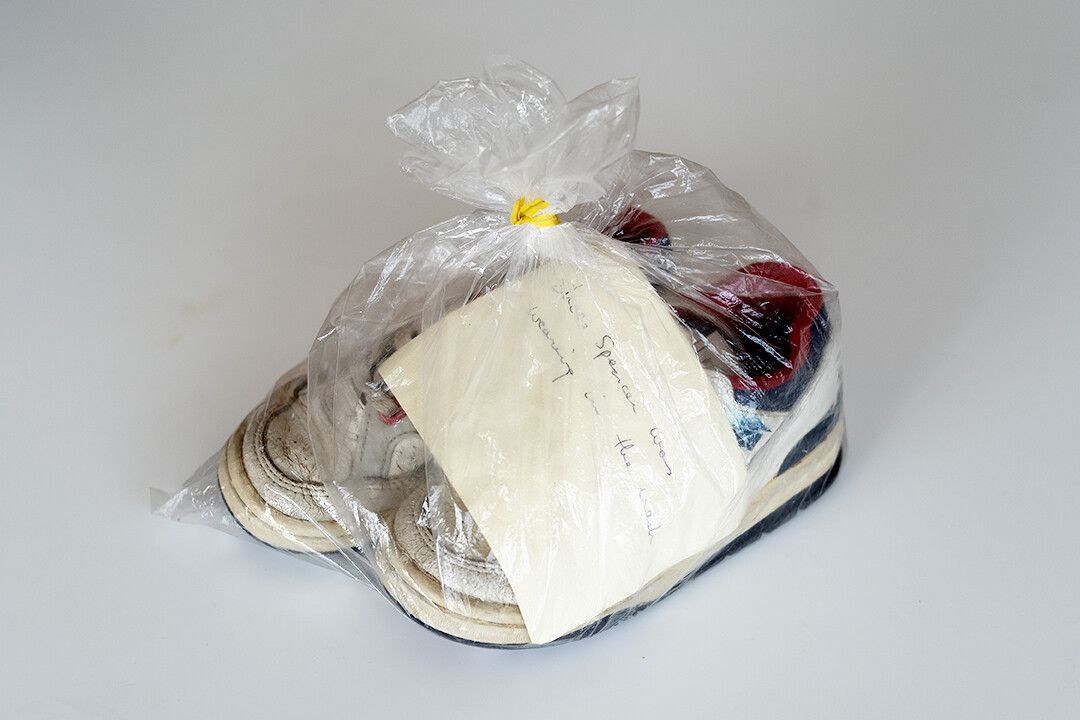

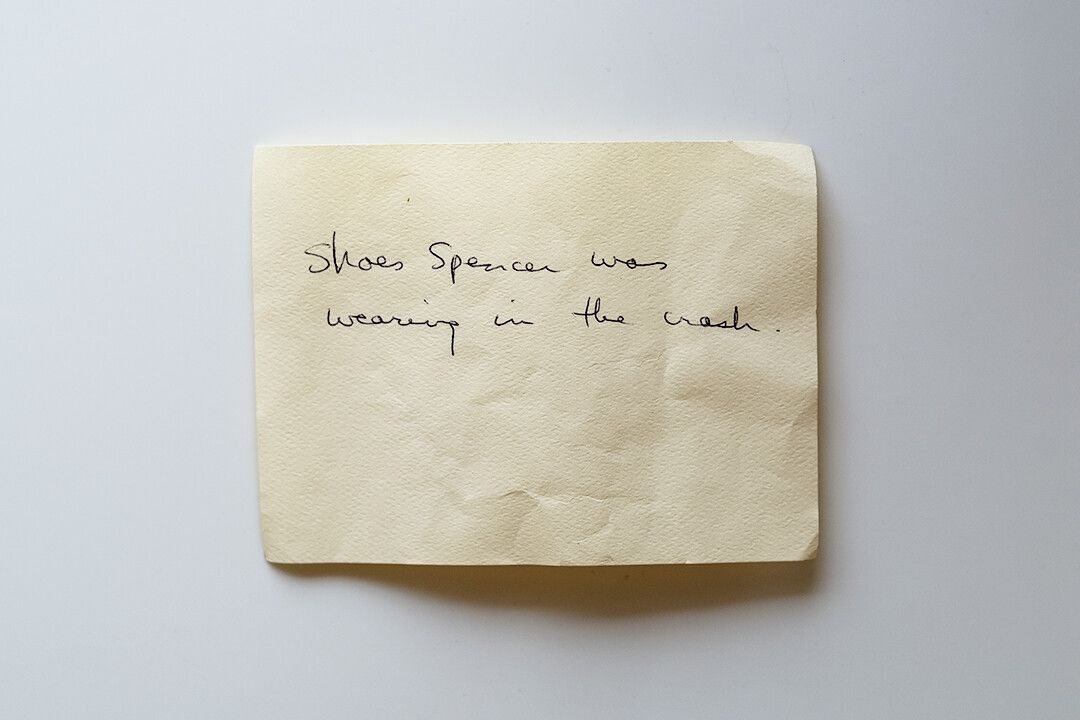

SB: It’s interesting you mention the shoes because, actually, the only thing—the only object—I still have from that day is the pair of shoes that I was wearing. Around fifteen years ago, my grandmother—my mom’s mom [May Louise Lockwood]—gave me the shoes. So they must have come with me after the hospital to Lake Placid [in the Adirondack Mountains], where there was a fourth-birthday celebration. And she had kept them. They were in a ziplock bag, and she had this little yellow sort of prescriptive note she had written: “Shoes Spencer was wearing in the crash.” I remember her giving those to me, and I thought, What a gift. That I have anything from that day. And that it’s actually these white shoes.

“Those shoes mean a lot to me. If there were a fire in my apartment, they’d be the first thing I grab.”

You, of course, know this a little bit, because I brought them into the studio [in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood, where The Slowdown is headquartered]. It was the day that I brought them into the studio, and we took them out of the plastic bag, that I had the first visceral [reaction to them]. I had never taken them out of the bag for some reason. I had always—and I don’t know why—kept them in the ziplock bag. But the day we took them out of the bag, I remember feeling immediately—especially when I turned them over and I saw dirt on the bottom of the shoes. I don’t know if that dirt is from the cornfields of Iowa, or the runway, or whether it was just from me playing in the backyard in Denver before we got on the flight. I don’t know. But it’s there. It’s caked in.

Those shoes mean a lot to me. If there were a fire in my apartment, they’d be the first thing I grab.

The shoes Spencer wore in the Flight 232 crash, stored in a plastic bag, the way his grandmother had kept them after the accident.

A detail of one of the scuffed-up shoes, with marks that indicate the impact of the plane crash.

A note written by Spencer’s late grandmother, May Louise Lockwood.

The shoes Spencer wore in the Flight 232 crash, stored in a plastic bag, the way his grandmother had kept them after the accident.

A detail of one of the scuffed-up shoes, with marks that indicate the impact of the plane crash.

A note written by Spencer’s late grandmother, May Louise Lockwood.

The shoes Spencer wore in the Flight 232 crash, stored in a plastic bag, the way his grandmother had kept them after the accident.

A detail of one of the scuffed-up shoes, with marks that indicate the impact of the plane crash.

A note written by Spencer’s late grandmother, May Louise Lockwood.

AZ: I find it interesting that, now in your life, you travel a huge amount. I’ve flown with you several times. You’re flying every other week. You have no fear of flying.

SB: None.

AZ: That doesn’t make sense to me.

“I continue to enjoy travel for that very reason: It makes me feel alive.”

SB: I mean, it’s kind of this idea of “What’s the worst that could happen?” And the worst that could happen, truly, is that I’m in another plane crash. But I think having that mindset, and also sort of just wanting to take as much as you can of what you’re given—you know, the opportunity of life, the opportunity of waking up in the morning and breathing, and being able to realize “I can get on a flight and experience this culture or this place, or help grow my business this way, or go meet this person I’ve always wanted to meet.” To feel afraid to do that—I’m really glad that I don’t. Because it’s allowed me so much experience. I continue to enjoy travel for that very reason: It makes me feel alive.

AZ: That’s so interesting, because when we first started working together, and we started sharing a calendar, your calendar was so incredibly dense. I’ve got three kids, I try to keep up my friendships, I work pretty hard. [But with you] it’s a breakfast, lunch, and fucking dinner every day with someone.

SB: [Laughs]

AZ: And, at first, it took me a while to understand how the hell you did this. I came to understand that it’s true that you really want every single day to be as meaningful and as opportunistic as possible. And I say “opportunistic” in a positive way, not a negative way. I say it in a way of, you really want to take advantage of every single opportunity that’s possible in that day.

It’s been inspiring to be around, because I don’t have that. I’m focused, I work hard, but I’m not as aware of the time of the day and the scheduling. Even when we first started working together, everything was, “Okay, let’s schedule that hour for that thing.” Big adjustment for me, having worked for twenty years in a very different way. I kind of go with things, and it’s been interesting to work with you in that way, to look at time as a scheduled, kind of precious [thing].

SB: Time, for me, grew into that. I don’t think time felt so precious when I was a kid. In fact, large chunks of my youth have been forgotten, intentionally. There are years I don’t really remember. Years my dad didn’t really take a lot of pictures. There’s a whole chunk of my youth, probably from age six or seven until twelve or thirteen, that there are maybe a few hundred pictures, but not a ton of memory from that time.

“The older I get, the more conscious [of time] I am, the more time sensitive I am, the more I understand that I cannot waste my time doing things I don’t want to do, being around people I don’t want to be around, pursuing something that I don’t believe in.”

AZ: He was pretty busy.

SB: He was busy. And truthfully, I don’t think picture-taking was top of mind. In high school, [my schedule] was a bit militant. It was a bit—you’re going to do this, this, this, this. And I kind of continued that through college. Always doing too much.

AZ: Mm-hmm.

SB: But also knowing that when I reached too far I had to pull back a little bit. The older I get, the more conscious [of time] I am, the more time sensitive I am, the more I understand that I cannot waste my time doing things I don’t want to do, being around people I don’t want to be around, pursuing something that I don’t believe in.

AZ: When people pass on and leave us, we have to find ways to honor their memory—through ritual, through conversation. And that’s, in a way, how people stay around.

I’m curious—and I’m sure it’s changed over time and has become formalized in different ways—but how did you guys, at first, as a family unit, keep the memory of your mother around in the house? And then, how did you share that with the world as you moved forward?

SB: That question could go so broad. [Laughs] Well, one of my first memories, post-hospital, was my fourth birthday in Lake Placid. And this wasn’t really a memorial to her, I guess. But this is the kind of thing that, if there were a memoir to be written, this detail is just pretty uncanny.

Francie’s Cabin near Breckenridge, Colorado, built in 1994 as a tribute to Spencer’s mother. (Photo: @michaelclarkphoto/Instagram)

AZ: This was the first time the family was all together after the crash.

SB: Yeah. I mean, my brother [Brandon] was still in the hospital, but the family was all together. My cousin Whitney [Lockwood Berdy]—I think it was a shared birthday with her. And there was a hunt for M&M’s throughout the living room of my grandmother’s house. I never thought about it at the time, but then, in retrospect, I’m like, “Wait, M&M’s were my mom’s favorite candy.” We were hunting for Mom.

Then, of course, there are some more literal interpretations of your question. The one that is the most meaningful to me and, I think, my entire family is this cabin that’s part of a hut system, called Summit Huts, in Colorado. My parents had moved to Breckenridge, Colorado, in, I believe, 1980. My mom loved the outdoors, loved hiking. This cabin, which is in the backcountry of Colorado and sleeps around twenty people, is part of a system of huts that includes Tenth Mountain Division huts—former military World War II [training] huts that have been maintained by this nonprofit. Anybody can rent them, like Airbnb, and just reserve them far enough in advance and enjoy the wonders of nature. This hut [Francie’s Cabin] has had tens of thousands of visitors and has allowed so many people to enjoy this incredible part of the West. I’ve gone up pretty much every year since 1994, when it was built. It was built through donations from the family, from foundations, and it’s continued to be this incredible place of escape, of quiet, of reflection, and of getting to know Mom a little bit.

Spencer, age 4.

There is, of course, also her grave in Lake Placid, New York, where she’s buried. I’m going there next week for the thirtieth anniversary.

I do always want to take moments to remember, but I don’t want it to hang over my head every day. I don’t want it to be something that runs my life.

AZ: Because you’re here now, living your life.

SB: Exactly. In a way, I’ve moved on, but in a way, I’ll never move on. I think I’ll always be processing it.

AZ: We don’t get over things. We sort of integrate them.

SB: No. But if there’s something that I think about the most, it’s probably how grateful I feel to be alive every day. How I feel what a miracle it is to breathe. To wake up in the morning and be able to simply take a breath. Which sounds so mundane in a way, but when you go through something like what I went through—and I guess especially at the age at which I went through it, and to realize how fragile life is, because your mom’s not alive, because that’s your reality—I think that that is actually, for me, the most meaningful thing: taking a breath.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on July 11, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by sound engineer Pat McCusker. Special thanks to Bruce Miller and Tim Hynds at the Sioux City Journal.