Episode 138

Olivia Laing on the Pleasures and Possibilities of Gardens

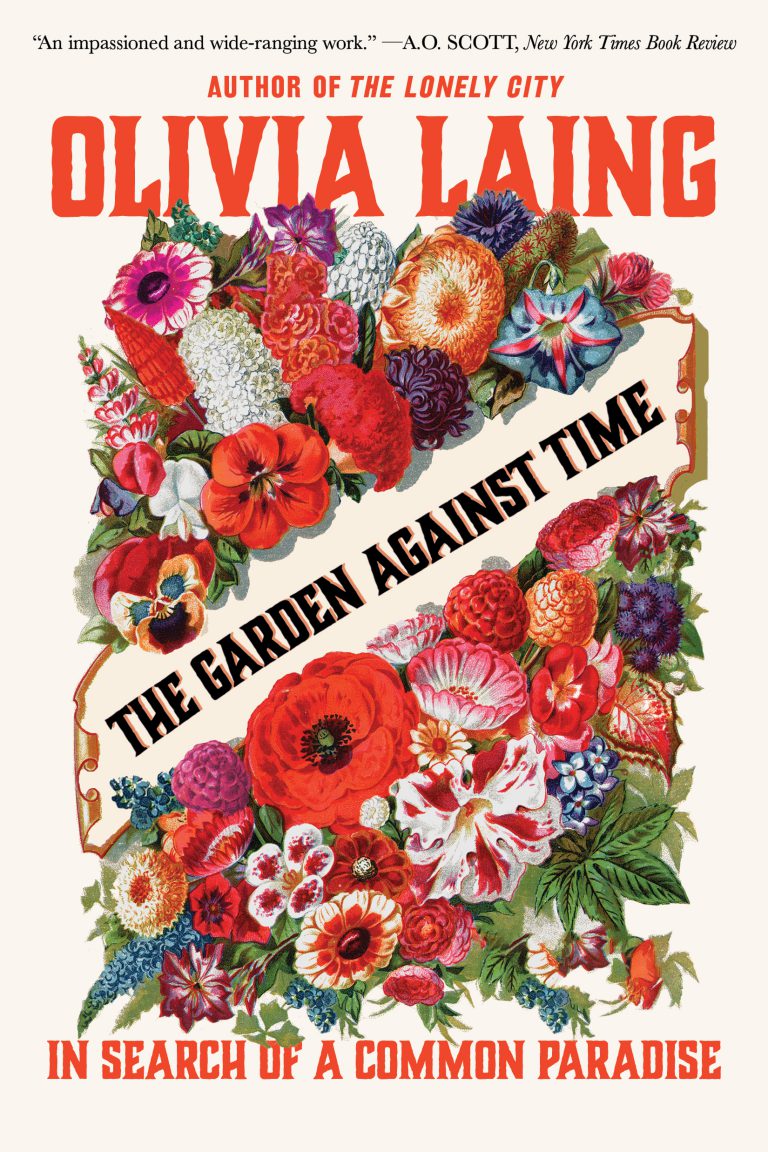

For the British writer and cultural critic Olivia Laing, restoring and tending to their backyard garden has prompted complex questions of power, community, and mystery, concepts that they beautifully excavate in their latest book, the fascinating and mind-expanding The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise. Whether in their nonfiction works, including the critically acclaimed The Lonely City (2016), their art and culture writing and criticism (2020’s Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency), or their novels (2018’s Crudo and the forthcoming The Silver Book, out this November), Laing turns an incisive eye to examining what it may take for people to forgo loneliness and isolation, reconnect with nature and one another, and flourish on a planet in crisis.

Gardens have, not so surprisingly, long threaded through Laing’s life, serving as a grounding source of fascination and peace, from their twenties as an environmental activist to their present-day life as an internationally celebrated author known for their probing, clear-eyed writing on art and resistance. A move in 2020 with their husband, the poet and academic Ian Patterson, to a house in Suffolk, England, formerly owned by the distinguished gardener Mark Rumary, opened up a new world of creative possibilities for Laing. Outside the back door, they found a hidden, untamed garden in deep need of care. Rehabilitating it opened up a portal to the extraordinary mysteries of what Laing calls “garden time,” rooted in cycles of rot and fertility, decay and rebirth. Gardening, for Laing, also prompted a deeper immersion into the subject through the lenses of history, politics, culture, and literature, as exemplified in The Garden Against Time.

For this episode of Time Sensitive, Spencer meets Laing in their apartment at the Barbican in London. The two discuss the symbiotic relationship between gardening and writing; the act of rebelling against a reactive, adrenaline-fueled culture by prioritizing and embracing slowness, in-person conversation, and what they call the “temporal self”; and the importance of imagining, in vivid detail, the kinds of utopias we could one day very well live in.

CHAPTERS

Laing shares their path to restoring the garden at their home in Suffolk. They also reflect on what gardening as a daily practice has taught them about cyclical time and finding fuller immersion in the present moment.

Laing speaks about discovering herbalism in their twenties, engaging in activism in the early nineties, and the formative texts—from Milton’s Paradise Lost to Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature (1991)—that put language to the magic, joys, and precarities of gardens.

Laing revisits memories of their youth in the U.K., growing up in a gay family during a period of state-sanctioned homophobia and the AIDS crisis. They also underscore the necessity of ongoing struggle and protest for bodily liberation and LGBTQ+ rights amid intensified present-day violence.

Laing considers the often imperfect, ever-mysterious practice of looking deeply and intently at something and the process of translating the visual into the written word.

Laing discusses The Silver Book, their forthcoming novel, set in the lead-up to Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s unresolved murder in 1975, which they wrote in a fever dream–like state while living in Rome.

Laing considers some of the technological, social, and cultural barriers to reaching a more utopic society and offers some possible paths toward building greater human connection and solidarity.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Olivia. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

OLIVIA LAING: Hi!

SB: First off, I should say how lucky I feel to be sitting here in your apartment at the Barbican in London, this magical place. I’ve always wanted to visit one of these apartments, so this is particularly special to be sitting here.

OL: The nicest thing about this apartment is it has huge glass windows, but we’ve actually drawn the curtains, so we’re sitting in a darkened chamber. You’re not really getting the full vibes.

SB: [Laughs] Well, let’s talk quickly then about the Barbican. How do you think about this home in the trajectory of your life and your homes? What is residing in the Barbican—which, you’ve put it as a utopian burst of a building, or burst of building—what does this mean to you?

OL: It’s a really magic place. So, this building, it’s Europe’s biggest art center, but it was built out of the wreckage of the blitz. There was this period of mass bombing of London. This area—we’re in the city of London—was the most affected. So, the old city, the medieval city, was completely annihilated. You have this postwar moment where people looked at that space and they didn’t think, “How much profit can we ring for this?” They thought, “Let’s make an art center. Let’s make a library. Let’s make a huge housing estate that is very beautiful, utilitarian and generous.” It has all kinds of gardens around it. So, it feels to me like it’s a physical, concrete embodiment of these dreams of communal possession, of public wealth that I, as a socialist, am deeply invested in. It’s a magic place to work. It’s a one-room studio, and this is my office. It’s where I do my thinking. It’s my retreat spot. So, yeah, it’s a very special place. I’m happy to have you here, Spencer.

SB: Thank you. Well, I was just thinking, too, how almost like your writing and your life, I guess, your extended life, this structure, this compound that is the Barbican, is a radical act.

OL: It’s a radical act, it really is. Yeah, and people still hate it. Right up to the present day—there’s a restoration project happening at the moment, and The Times newspaper said, “That building should be knocked down. It’s so ugly.” It infuriates people, because it really embodies that Modernist dream. It’s brutalist, it’s confrontational. But it’s about generosity. So, yeah, I’m on the side of the Barbican.

SB: Even though it’s brutalist, it’s also a garden.

OL: It’s full of gardens. Yeah, it’s actually quite gray and almost rainy today, but otherwise, I’d be suggesting that we were recording in one of the gardens, because they’re very special. There’s a great big lake, which, it’s the bomb site that was turned into a lake, and there are these beautiful gardens with really exciting plantings. It’s not the kind of ethos that you see in parks today. It’s really about making it as good as possible for as many people as possible. I like that.

SB: Well, this is a smooth, easy transition. I wanted to turn to your latest book, The Garden Against Time, which, as soon as I saw it on bookstore shelves, I was like, I have to get Olivia on the podcast. Since we’ve spoken a little bit about this Barbican home here, I was wondering if you could just speak also to your house in Suffolk, which had been owned by the distinguished gardener Mark Rumary.

OL: I’d lived in New York, then I was living in Cambridge. I got married to a Cambridge historian and academic who was coming up for retirement, and we decided that we wanted to live somewhere with a garden. I spent my whole life in rented accommodation and really moved an awful lot. I had a very turbulent relationship with housing over the years.

SB: It was like sixteen times in thirty years I read, something like that?

OL: Well, I think it was sixteen times just before I was 18. Yeah, we moved and moved and moved. I mean, for lots of, alcoholism, traumatic reasons. And then, just economic insecurity in late capitalism—everybody’s reason. Anyway, we ended up deciding that we would move to Suffolk and [we were] looking for somewhere with a garden, and that process of looking went on for a few years. Then, I saw online this description of a house, but particularly a description of a garden. And it was like, “It’s divided up into rooms. It’s got a quatrefoil pond.” Just very romantic descriptions. And I was like, “Oh, well, I need to see this place. It’s probably not a possibility at all, but let’s go.” It said that it had been designed by Mark Rumary, and that was interesting. I didn’t know him then, but I knew the Suffolk nursery, Notcutts, that he worked for, because it’s one of the most famous nurseries in the country.

We went to see it on a winter’s day. Traditionally not a great time for gardens, but he planted it both for structure and for scent. So, you come out the back door of the house, and it’s almost like these enclosed chambers; they’re very beautiful. They’re divided by hedges, they’re divided by walls. And there are plants like daphnes and witch hazel that just send these currents of perfume out into cold air. And it was absolutely bewitching, but also it was very neglected, it was very wild, and it was clearly a restoration project. And actually, when I look back at photos from that, I think I completely underestimated the level of restoration, because I was so excited. It was a big job to draw it back, but instantly enchanting.

SB: Right. He had passed away in, what, 2010?

OL: He died in 2010. The last, maybe five years, I think, of him being there, he couldn’t really cope with it anymore. So, I think that, putting it together from photos later, I think that it was already getting a bit wild. But then, very luckily for me, the people who took it on weren’t gardeners. They treated it like it was antique furniture. So, they were like, “Don’t take anything out. Don’t touch anything, just leave it.” So, I came back and nothing had been lost, but it was all hidden under ivy. It was a real secret garden, Sleeping Beauty kind of situation. The dream situation, as long as you’re willing to carry ton after ton bag of ivy out, which I was.

SB: There’s definitely a metaphor there somewhere, right? [Laughter]

OL: Yeah, absolutely.

SB: In your book, you write about the garden as a “mysterious timepiece.” I’m going to quote here from perhaps my favorite passage in the book. You write, “The garden as a clock: what a beautiful image. Garden time is not like the ordinary time in which we live. It’s different to a watch or the glowing numbers on an iPhone lockscreen. It moves in unpredictable ways, sometimes stopping altogether and proceeding always cyclically, in a long unwinding spiral of rot and fertility. To pay attention to the garden as a clock means entering a different relationship with time: as circular, not linear, as well as the acknowledgement that one of its recurring stations is death.”

OL: That’s my favorite paragraph, too, actually. I love that.

SB: Could you elaborate on this? It’s so beautifully put there, but maybe speak a bit to your time in gardens and gardening and how this has shaped or reshaped your temporal landscape.

OL: Yeah, absolutely. But I guess it’s also important to say that I wrote this book and I did this restoration during the stopped clock of the pandemic. So it was already situated in this strange time where time wasn’t moving forward. The numbers were moving forward, but nothing was happening. I think that really allowed me to pay attention to time in a different way; to think about time in a different way. The thing that fascinated me was this idea of time as a cycle. This idea that time moves through these moments of glorious fertility, the moment of roses, but then things die away. And realizing, reading my Milton and reading the Garden of Eden and realizing more and more how we have fallen into this very seductive trap of thinking that we should always be inside summer, we should always be inside the summer of capitalism, where there are strawberries, but it’s Christmas, where there are roses anytime of year. This idea that we can constantly force the earth to keep us in an impossible summertime, and the intense ecological cost of that.

SB: Yeah, the grocery store clock is not the same as—

OL: The grocery store clock is not ticking. It’s a stopped clock. And the more I thought about that, and its intense environmental costs—often hidden from us in the cities that we tend to live in—but elsewhere, enormous costs to this illusion. That made me think that the garden clock really has something to tell us, and that something is that we have to allow ourselves to move through these cycles of rot and decay and almost nothingness before coming out the other side. It was a real invitation into a different understanding of time.

SB: Well, tell me a little bit about your time in the garden then, too.

OL: Yeah, that’s a different time altogether.

SB: … and that’s beyond time in a way, as well. I’m not just talking about Covid time here. I’m thinking about your youth, your father taking you to these gardens. Even in The Lonely City, there’s a garden in New York City that appears. I mean—

OL: Oh, yeah, the East Village Gardens. Yeah. So, I mean, gardens are threaded through my life. Like I said earlier, it was an erratic childhood, and gardens really formed this place of security. My parents divorced when I was quite young, and my dad’s way of spending time with us was pretty much always to take us to gardens of stately homes. So, these really big and beautiful, but often slightly melancholy, slightly past-their-best places that felt like they were separate from the world, suspended in time, often with this very compelling sense that you were stepping through a portal in time, that you were somewhere else, that you were in a different time.

So, I always had the sense that the garden had an odd relationship with time. It had this capacity to take you out of the time that you physically were situated in and move you somewhere else. But I think the other thing… There’s a lot of complex ideas about time in the garden. The other thing is that, when you are gardening, when you are physically doing something in a garden, you almost inevitably and very rapidly find that you have lost track of the daily preoccupations, and that you are in that state of fluidity or flow that is absolute immersion in the present moment, and I think that is what makes it such an addictive, compelling practice.

That’s the thing that I most love about it, is that I go out and I start fiddling around with my secateurs, cutting back a fuchsia, and five hours have passed. And in that entire time I’ve just been swimming through time. It’s very different from my normal experiences of, “I’ve got five minutes. I’ve got five minutes. I need to run.”

SB: It’s interesting you just said, “swimming through time,” because it makes me think of how swimming in its own way is another one of these methods of… Actually, when I interviewed the author Jhumpa Lahiri on the show, she talked about that. She talked about how when she’s swimming, it’s almost a form of losing track of time. There’s something that takes over the body.

OL: Yeah, those repetitive tasks where you’re just very… I mean in swimming, you’re literally immersed, but that is very immersive, I think they take you into a different kind of time. And I think honestly, we crave that so badly that that’s what makes those activities so desirable and why you keep coming back to them and coming back to them.

SB: There’s something also very therapeutic about both, but gardening in particular, and I hope this doesn’t sound name-drop-y, I don’t want it to sound name-drop-y, but maybe it was 2012, I think, I interviewed Rodney King. It was one of the last interviews before he was—

OL: Wow.

SB: … found dead at the bottom of a swimming pool, actually. And we talked about gardening. Gardening had saved his life.

OL: Oh, my God.

SB: He, of course, had been an alcoholic—suffered and dealt with just horrible trauma—and gardening was the thing that helped get him out of it. He talked about the power of being in the dirt, digging.

OL: I think that’s really true. It’s a very physical existence, and often we’re very divorced from physicality. Increasingly, as we’re moving into more and more virtual realms, to actually be touching, caring for things physically, I think is very important to us. And it’s constantly exciting because things are constantly changing. So, you’re invited into this universe of the present moment, in which there is continual action. Everything is a present moment. There’s a bird passing. There’s an apple falling off a tree. There’s stuff happening around you, and you’re a participant in that. I think, back to socialism, it’s a sense of us as networked. It’s a sense of us as part of an organic community of beings, rather than this dominating individual, which actually is a weary thing to carry around, I think.

SB: Yeah. You go into so many different nodes in The Garden Against Time when it comes to gardening. There’s no way we could unpack them all here. But in that book, I did want to bring up one of those nodes, which is that you write that “War is the opposite of a garden, the antithesis of a garden. It’s the furthest extremity in terms of human nature and human endeavor. It is possible that a garden will emerge from a bomb site, but it is certain that a bomb will destroy a garden,” which reminds me of, and I had just done this interview recently, not for the show, but for a magazine piece with the Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf.

OL: Oh, great.

SB: In it, he said, “Beauty is what we need in life next to war and all this craziness. It’s an escape from reality.” Your view of gardens also looks at the costs of this beauty, though, and I wanted to touch on that. Could you speak to the costs of the beauty of the garden or the under layers of the garden that we don’t talk about, because we get so transfixed, I suppose, by the beauty.

OL: Yeah, absolutely. There’s beauty, and there’s beauty, and I think the kind of gardens that Piet’s making are genuinely really beautiful. But what I wanted to really interrogate was the idea of the great gardens of power and what they’re concealing in terms of who’s excluded, but also in terms of what’s funding them. What’s the actual financial trail that leads to that sort of production of beauty? Because I think sometimes beauty is a performance of power. The way that I did that in the book was to track this family called the Middletons, who started in Britain, who went to the West Indies and then to America, made their fortune in slavery, came back to England and really cleansed that fortune by way of the production of an increasingly beautiful and elaborate garden that really physically moved them up the social echelons into the highest rooms of power—they became friends with the royal family.

As I was writing it, I was thinking the analogy for this is really the Sackler family. The Sackler family used art in order to wash the blood of their enormous wealth. I think the Middletons worked in a similar way, but instead of art, it’s gardens. That kind of sinister side of beauty is something that I really wanted to be alert to, to talk about, because that’s not something you tend to hear about in garden histories.

SB: Well, those are your two subjects—or two of your big subjects, anyway—art and gardening. So it makes sense that you would draw that analogy.

OL: Yeah, absolutely.

SB: One of the other things that I was hoping to get into was that, in part, you came to gardening or botany, anyway, through herbalism. This was a very particular time in your life, the herbal medicine time of your life. Could you speak to that? It was your twenties, basically. What led you to herbalism? I mean, it was really activism, right? A jump from activism to herbalism.

OL: Yeah. I dropped out of university at 20. I was studying English literature, and I got very involved in environmental activism. This was thirty years ago, and I was very worried about the climate crisis thirty years ago. I’ve got to say, I’m a lot more worried now. I was particularly involved in campaigns against road building. In that period in the early 1990s in the U.K., there were a lot of literally encampments in woods that were on the pathway of proposed roads where people would come in, they’d set up a camp, they’d build tree houses, live in the trees—literally live in the trees. We’d have houses in the trees. We’d build double lines of ropes between trees so we could move around inside the trees. It was this extraordinary life. It was really an amazing experience of living in a very different way within the twentieth century.

Like many activists, I burnt out on that after a year or two, and it’s a very extreme life. So I left. I ended up living in a field in Sussex, an abandoned pig farm, and I built my own… I’m trying to draw it with my hands. I built my own sort of… They’re called benders, and they’re a kind of tent structure that you make by bending hazel poles with a tarpaulin on top. I had a window, I had a double bed and a sofa in there. I had a wood burner. I wanted to do something that was useful, but also that did no harm—that real strong activist sense of wanting not to contribute to the myriad damages that were being done to the planet. So, I decided to train as a herbalist, and actually a lot of the attraction of that, it was literary.

I had read Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature as a teenager, and it’s full of all this stuff from medieval herbalism. It’s full of this kind of spell of language about plants. And I loved it. I found it very seductive. So I trained, which is a five-year equivalent to a medicine degree. Then I set up practice and I saw patients and, before I even qualified, I knew that I was on the wrong road. I knew that I wanted to be a writer, but I didn’t want to drop out of something else. So I finished it.

And really, I think it was an incredible grounding, of course, as a gardener to learn botany, to learn materia medica. But it was also a training ground to be a journalist, because what you were being taught to do was take case histories. You were being taught really how to interview somebody about the most difficult regions of their life. So I don’t regret my twenties. They were pretty strange, and they were very wild, but they were foundational, Spencer.

SB: Radical.

OL: They were radical. They were out there.

SB: Yeah, when you read your work, it becomes so clear that that time was such a key foundation to everything that came after. I enjoyed learning, too, that, prior to writing The Garden Against Time, you’d never read Milton’s Paradise Lost. Of course, as you were just saying, even before you began gardening in earnest, you were learning about plants. You were reading all these books, and there really is this interesting intersection between literature and plants, or literature and gardening, and to that point, writing and gardening. Could you talk about all that? Your immersion basically from books to plants?

OL: Yeah, because I think that the language of plants is extremely exciting and very, very beautiful. When I was writing The Garden Against Time, and there was a bit of discussion with my editor about, do we want to have all these lists of plants? What if people don’t know what they are? What will they do? I’d had that previously with The Lonely City, where it was like, “Well, all these artworks, should we have pictures of them?” And I was like, “There’s this thing. It’s called the internet. People will Google them.” So I was very confident that if people wanted to see what restharrows looked like or what Rosa Mundi looked like, that they would Google that and they’d see it.

But I wanted the language to be there, because I think it carries out its own kind of magic operation—that people just love that language. It’s very, very old. It’s very culturally dense for us. I think our relationship with plants and our sense of wanting to talk about them and think about them goes back a very long way. That felt very important. I’ve forgotten what the second part of that question was.

SB: Well, I was just asking about—

OL: Oh, language generally.

SB: Yeah, exactly, and the connection between writing and plants.

OL: I think the idea of the garden is so entangled in literature, but also in children’s literature: The Secret Garden, Tom’s Midnight Garden, and all this sense of gardens being places where things happen; gardens being portals between worlds; that idea that the garden is an imaginative space. What a garden actually is, if we think about it abstractly, is that it’s situated exactly on the boundary between nature and culture. It’s not wild, but it’s not completely tame, either. It’s alive, it’s interacting with us, it’s pushing back.

We might want to dominate it. We might want to allow it to dominate us, in a way. So, it seems to me that it’s situated in a very interesting place, and I think that is why it has such an outsize role in our literature and in our culture. It’s there in Mughal miniatures. It’s there in all of these different realms of culture, because people find them not just beautiful, but kind of strange—just at the edge of our power.

SB: Tell me about your Paradise Lost time.

OL: Okay, I mean, this is really a pandemic story. [Laughs]

SB: That is a tome. I mean, admittedly, I still have not read Paradise Lost.

OL: You are missing out, because it is the greatest… I mean, it’s the invention of cinema. Some centuries before cinema was invented. It’s a graphic novel. It is so kinetic and funny. It’s got fart jokes. None of the things I thought about Paradise Lost are true. It’s very different.

So, you have this very dramatic story. There’s a war in heaven, but you don’t start with that. You start with the losers, Satan, and his Satanic crew literally falling from heaven, smashing through the air, crashing down in a sea, and it just carries on like that. It’s very physically dramatic. The language is astoundingly rich. Like I say, I was reading it during the pandemic, and hadn’t seen any people for quite a long time. I was reading it aloud to myself, and I tend to sort of mutter my way through books, and I’d read a chapter and then I’d leave awhile, and then I’d come back and get back into it. On the page, it might look inert, but when you start saying it, you realize it’s got this sort of driving rhythm. So it’s very exciting. The story is very exciting. Then there’ll be gossipy bits or kind of playful bits or dramatic bits. That Milton was really good at telling a story. Shocker.

SB: Well, another text that I wasn’t familiar with is the poem “The Garden” by Andrew Marvell, which you say, “I’m not sure there’s anything in literature that better enacts the spell of being in a garden than the middle stanza, in which plants are weirdly more active than the speaker. And time itself is” … this is a great word … “ensorcelled, slowing line by line until it stops dead. Stunned.”

OL: Yeah. I can’t say anything more than that. Everyone needs to go and read, if not the whole thing. And it’s very short, but that middle stanza is spectacular, because it really does feel like time gets heavy and syrupy, and you have that sense of lying in the sun under an apple tree on a midsummer day, where there are bees, and the air’s heavy, and it’s very voluptuous, and you just feel like time has sealed you up inside this gorgeous little honeycomb. I like that.

SB: I don’t want to leave the honeycomb, but let’s turn to your childhood. Actually, I wanted to start here on the subject of birth, because you’ve written beautifully about this subject in your book, Everybody, or maybe it’s pronounced Every Body, I don’t know—

OL: You can say it either way, it’s up to you.

SB: …which was published in 2021. You write, “To be born at all is to be situated in a network of relations with other people, and furthermore to find oneself forcibly inserted into linguistic categories that might seem natural and inevitable but are socially constructed and rigorously policed. We’re all stuck in our bodies, meaning stuck inside a grid of conflicting ideas about what those bodies mean, what they’re capable of and what they’re allowed or forbidden to do. We’re not just individuals, hungry and mortal, but also representative types, subject to expectations, demands, prohibitions, and punishments that vary enormously according to the kind of body we find ourselves inhabiting.” Could you speak about your personal experience through this lens?

OL: Yeah, but I mean, how many years ago did I write that? It’s become so much more violently the case. It’s kind of sad to hear, because I think that is the fault line that we’re on right now, and the rhetoric around it—and not even the rhetoric, the violence and violence of laws around it have become so much more intense in the past, I guess, five years since I wrote that bit.

My experience, again, was kind of radicalizing. I grew up in a gay family. My mom was gay in the 1980s in the U.K., which was a time of intense state-sponsored homophobia. There was a law called Section 28, which meant that schools and local councils couldn’t teach about the so-called “pretended-family relationship” of homosexuality. It was really about the gay family almost above all else.

So to live in a gay family, in those times where you are actually explicitly outlawed, and to grow up inside that kind of closet, and then to come into teenage years during the AIDS crisis, and to experience that level of hatred is to give you a really strong insight into how some types of bodies—how some types of people—are treated compared to others, and to have a deep, intrinsic skepticism about the state’s capacity to put people into categories and to treat people in some of those categories in absolute different ways to others; to make people feel that these divisions are natural and that the people who are the natural category that’s applauded, that’s desired, don’t even see until they find themselves crossing over those lines.

SB: You’ve described yourself as an anxious, not very happy child, and how could you not be in those conditions?

OL: Yeah, I think that’s true. I mean, I’m a trans person, and I think that was something that was probably going on for me through those years, as well. But to grow up in that level of homophobia. Add to that, growing up in an alcoholic family, which has its own sort of layering of secrecy, so it’s like this almost double closet, these sort of two layers of secrecy and concealment, I think that’s a very difficult experience personally. It gives you a sort of X-ray vision into how a society works.

Also, to have those very formative experiences of protest to be on gay pride in the eighties when the police weren’t marching, the banks weren’t marching. It was a very, very different experience, and it was much more radical and much more—

SB: Now we hear the kids. [Faint sound of schoolchildren in a schoolyard outside Laing’s window.]

OL: … on the brink, I think. Yeah, here come the kids. [Laughter] It was an awakening at an early age in a way that I’m very glad I had.

SB: There’s another bit of text from The Garden Against Time I wanted to bring in here, because you write about how “we all travel into adulthood bearing particular burdens, some of which are necessarily personal, individual, idiosyncratic, and some of which are more properly categorized as political, to do with the kind of history doled out to the people who shared our circumstances.” I mean, this is almost—

OL: Same point, really.

SB: It’s an extended version of the birth thing. It’s you’re born and then you travel into this, carrying this. And reading Everybody brought me back to a book I spent some time with early in the pandemic, actually just before the pandemic and then Covid, which is Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score, which you also reference in that book. Reading your book was almost like, “Oh, here’s a cultural, political, social theory version of everything Bessel’s writing about.”

OL: Yeah, I think that’s true. Actually, I mean, the central character in Everybody is Wilhelm Reich, who is a controversial and deeply interesting psychoanalyst, activist, anti-fascist, and who had this idea of character and that had this idea that our bodies carry things around that we can’t speak verbally. And I think that is at the core of what Bessel is doing. I think that’s the core of The Body Keeps the Score. So, we were definitely interested in the same set of ideas.

But I really wanted to think about the political realm outside of that and both how people are damaged by the social systems that they find themselves within, but also how people, by way of their bodies, can change that. So it’s a history of freedom movements. It’s really a history of feminism, gay rights, civil rights: these different movements that manage to change the lives of so many for, what, a few decades? It’s so unclear now how long those victories are going to last. I think one of the big things about writing Everybody was to say, “These victories are not permanent and this struggle is not over.” The Italians say lotta continua: the struggle continues.

SB: Well, then gardening is sort of this extended method, mode, way of being beyond that. You’ve noted how there’s a “fragile” aspect to gardening, and this is a big question, and maybe I’m reaching here, but—

OL: I’m cracking my knuckles, I’m getting ready. [Laughs]

SB: I wanted to ask, do you see a link between the gardening you’re doing or gardening generally as a release from your past or one’s past, as a way forward? Is gardening in some sense a form of opening up, of letting go, of processing the past? Or not moving on from it, but I like the word processing. Is gardening a form of processing?

OL: I think what I came to realize was that, first of all, gardening and writing were very similar for me. They’re these very complex activities that have an architectural element where you’re building something and then a daily element where you’re tending something. I think both of those things are a way of handling trauma, a way of thinking through trauma, a way of perhaps semi-compulsively needing to make something orderly out of the disorderly, and the drive, I feel, to do both is similar. It’s not that I think all artists are traumatized people, but I think traumatized people often have a desire to make things, to create things, to engage in these processes that have a relationship with complexity and have a relationship with a movement from disorder toward… A movement from chaos and ugliness toward beauty.

But then you can’t stop there. You can’t rest. You need to keep continuing it. I think that’s why the garden is so wonderful, because, unlike a book, the garden isn’t finished. I didn’t finish that garden. I finished the book. The garden continues to resist my attempts.

[Laughter]

SB: Well, one of the other things that I would say is a thread through so much, if not all of your work, but certainly through your writing about art and now gardening, is the role of looking. The study of botany is all about looking, but so is the study of art, and you’ve spent a lot of time looking.

Could you speak to that? I know it sounds sort of like an abstract question, “Just tell me about looking.” But how do you think about the time spent looking?

OL: So, the first two books I wrote, I was really using books and literature as my cultural material. I write these large books that are investigations into culture and politics, but they use art-based material.

The big revelation, the big turning point, I think, in my career was with The Lonely City, realizing that I didn’t want to write about books anymore. I wanted to write about art. Somehow, it felt to me like traveling into this hall of mirrors, writing books about books. Whereas having these physical objects, it just did something. It allowed me to write and think in a different way. It was incredibly freeing.

From then on, I suppose, there has been this strong relationship with looking. But with translating the physical object, the David Wojnarowicz “Magic Box” or an Ana Mendieta photograph: these very charismatic, powerful things that I’ve written about over the years, finding a way to translate them into language, so that the reader can see them without seeing. That’s a strange and mysterious process in itself. And that’s something I find very compelling to do, because it’s impossible. What I’m doing is impossible. That act of ekphrasis, that act of turning the visual into the linguistic isn’t—

SB: It’s a form of magic in a way.

OL: It’s a form of magic, because—

SB: Alchemy.

OL: … you’re never going to be able to pull it off. There’s always going to be ways in which you failed to fully summon the—

SB: And yet—

OL: … thing, because the thing is real.

SB: … I would say as an art writer, you have shifted how I think about certain art. Agnes Martin—

OL: Yeah, that’s a good one to talk about.

SB: … I’ll use as an example. I love Agnes Martin’s work. I’ve seen it many, many times. I had never thought about Agnes Martin’s work the way I thought about it until I read your words on Agnes Martin—which probably came from a lot of looking, I imagine.

OL: A lot of looking. A lot of looking. Actually, to just think about that act of looking, it’s looking and note-making, because I have realized that what I think is looking often isn’t looking at all. It’s a kind of gazing. It’s not until I’ve got a pencil in my hand that I go, “Hey, is that an eyelash stuck to this kind of peach-colored line below the blue line? There are snags in that pencil mark where her pencil has jumped. These are paintings with stripes where she’s drawn lines.”

It is the act of writing about looking that makes my looking better. I’m really certain of that. I’ll kind of scan through a gallery and I’ve hardly taken anything in, and when I try to resolve it into language, I’m like, “My looking was imperfect. I need to go back and I need to write down what I’m seeing as I’m seeing it.” So strangely, actually, language makes looking come to life in some strange way for me.

SB: I’ve seen it called “slow looking” as well, where someone’s almost, by reason of trying to understand something much more deeply, you have to do it slowly, because at a quick glance, you might get a snapshot, you’ll get some information, but it’s only by almost painfully looking.

OL: Yeah. Coming back, coming back, coming back. And I am the kind of person who will walk through a gallery in five minutes and just wait and see what catches my eye. I am a quick looker, but I’ve had to train myself.

I’ve said this to writing students: You come into a room, you think that you are seeing it and therefore you’ve absorbed it. But if you don’t write down what color the carpet is, in a year’s time when you come to write it up, you will have lost all of the texture of that, and those are the textures that the reader needs to enter the world that you’re building. Other senses matter too, but visually in particular, it has to be visually rich.

SB: For all those who haven’t read it yet, I highly recommend reading Olivia’s book Funny Weather, which is a collection of their art writing from over, what? About a decade or so?

OL: I think a decade.

SB: In the introduction, you write, “What I wanted most, apart from a different timeline, was a different kind of time frame… The stopped time of a painting, say, or the drawn-out minutes and compressed years of a novel.” So you were using these columns of art to kind of make sense of things, and time actually was this incredible element in that.

OL: Time was driving me crazy at that time, because this is also around the moment that I wrote Crudo, and I think—

SB: Your novel.

OL: My novel, which is, again, this kind of intervention into time, because this is the period, I guess around 2017, 2016, where time seemed to be speeding up. It was the beginning of that rise of the far right. It was the beginning of the refugee crisis. Brexit was happening here and, I don’t know about you, but I was on Twitter a lot then, and it felt like something was happening to time, that it was this horrific tidal wave that was coming over us all the time with information that felt absolutely urgent, but that was replaced the next microsecond by information that was absolutely urgent, so you just had this sense of being overwhelmed by a sort of constant, horrifying present. And I felt this very powerful need to pull back and to find some way of processing what was happening, rather than having reaction after adrenaline-fueled reaction, cortisol-spike reaction.

SB: You just articulated why I started a company called The Slowdown—

OL: [Laughs] The same—

SB: … in 2019. I mean, really started thinking about and organizing it in 2018, so it was right at the—

OL: Because it was that moment.

SB: It was that moment. And I remember feeling like, “What the hell is going on to time right now? Is everyone else feeling this, too? This is insane. I’m feeling insane.”

OL: Yeah, absolutely. And it’s only got faster and more intense. I think I made a conscious decision then that I was going to pull back.

The two things I did sort of simultaneously were Funny Weather, those essays that were trying to use art to look and make sense and get different kinds of perspectives, and then Crudo, which was this attempt to just catch what that feeling felt like, that sense of overwhelm and that sense of the political and the ultra-personal being smashed together in a way that really felt unprecedented and grotesque and very hard to process and make sense of.

SB: Well, I mean, my whole theory was there’s going to be a slowdown. I don’t know how it could be. I actually never thought of a pandemic at the time, but—

OL: Well, there you go!

SB: … that’s what ended up happening. There was a pandemic, and then we’re all stuck at home behind our screens, looking out at the world out our windows as if it’s sort of like we were in our own little spaceships or something. It was this very strange moment. And now, I think, I don’t know. I’m sure a physicist could probably study this somehow, but time to me feels even faster in 2025 than it was in 2018 or 2019.

OL: Yeah. I think that’s true, and I think this oppressive speed-up is beyond our capacities. That’s where art, in the larger sense, including literature and film, is so crucial: to allow us almost these escape hatches into a different kind of time where we can make sense. The process of making sense isn’t fast. The process of sort of apprehending is very fast. We can be very fast at grasping the—

SB: Yeah. It’s the Malcolm Gladwell—

OL: … significance of things.

SB: … Blink thing, you know? It’s just, okay, you get it?

OL: Yeah.

SB: But?

OL: Absolutely. But no, I haven’t got it at all. I haven’t begun to get it, and some of these things really take a lot of thought. And they involve things like ambiguity and ambivalence, which can’t be registered in an Instagram post or a click. It has to take time and space to hold all of these different positions.

I think that’s where something like the novel is so crucial, that it can have this artful relationship with time, where you can look at consequences, where you can see how things land over the not just days and weeks, but decades and centuries.

SB: Well, I did want to bring up a book that you wrote about, which is in Funny Weather. I wasn’t familiar with this text. It’s Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time. I’m bringing this up, because it was a book that Powell started at age 40, which you describe as “the age at which you begin to notice how strange time is, how it repeats and returns, how the group you travel with is inexorably diminished. On you go, go you must, bound feet moving on damp ground. The weather isn’t looking good, time’s running out, a shrapnel of light falls whitely on the birch.” [Laughter] This is where I should say, I also just turned 40. So reading this, I was laughing.

OL: I mean, actually I’d forgotten I thought that, because subsequent to reading Powell, I read, Anthony Powell, I read Proust. And it has similar sets of revelations. And I was like, “Oh, I’m really thinking these thoughts for the first time.” But actually I think I’d thought them before. And that’s the great joke of Proust, is like, you’re always coming back to things as if for the first time, and then realizing that you had exactly the same thought ten years earlier, in exactly the same place. We repeat, and we repeat.

But I suppose the big revelation of the forties is that all those things you thought were done and dusted come back to you, making a completely different sense. It’s almost like you’re given back your teens and twenties anew, in new forms, in a way that you can’t possibly guess when you are living inside them, because time keeps producing more and more facets, and I think that’s the thing that makes getting older so, actually, exciting.

SB: Yeah, it’s not linear. It’s a circle.

OL: It’s a circle, yeah. And you’re coming back from these strange loops through time where you see something absolutely from the opposite side, like seeing a film twice from different perspectives. It’s extraordinary.

SB: Going back to the same place, swimming in the same lake, or these sorts of experiences, these sensory—

OL: And they get more and more layered, they get more and more rich. Yeah.

SB: Well, let’s talk about your next book.

OL: Okay.

SB: I want to hear about the next book. In the fall, you’re going to be releasing The Silver Book, your second novel. Tell me about this. I know that you wrote it over the course of three sleepless months in Rome. [Editor’s note: Following the conversation, Laing clarified that it was, in fact, two and a half months, and that they did sleep.]

OL: Yeah, it was a very, very exciting writing experience, not something I’ve really experienced in my career. Because Crudo is auto-fiction; really, everything in Crudo happened. I was just trying to find a way of writing it down. But this book is a novel. It’s fictionalized, it has a plot that’s fairly complicated, and I had the idea for it in Venice a couple of years earlier, but I couldn’t write it, because I was so involved in touring The Garden Against Time. So I was holding it, like this sort of burning ember, for a long time.

And as soon as I got to Rome… It was very odd. It was almost like a frequency opened up, and I could hear, and I could type as fast as I could type, and I could keep hearing and hearing until it finished. And, during that time, it was really about finding the stamina to be able to write for as long as I was writing, which was dawn until the small hours, because it was moving so fast. I think if that had been my first book, I would have a very wrong idea of what writing is like, because it isn’t like that.

SB: Yeah, yeah. I mean, tell me a little bit about your writing, generally. Because this feels like a fever dream, right?

OL: This is a fever dream.

SB: This is a fever dream, but—

OL: Writing is not a fever dream; you will not have these experiences. They do not come along. And writing is often painful, boring—it takes a long time. As a nonfiction writer, I’m an archive-based writer, so I’m spending a lot of time gathering, researching, sifting. It’s a slow process of construction. That building site is up for a long time. So, to have this experience where something moved so fast, I think it’s clear that it’s a book by somebody who’s written a lot of books, that it wouldn’t have been possible, new to the game.

And it had an element of—I don’t want to use the word magic—but there was something strange happening, as well. There was something uncanny about the experience. And it’s a novel set in 1974 and 1975, in Italy. It’s about the making of Fellini’s Casanova, and Pasolini’s last film, Salò, and it’s about the murder of Pasolini. So, it’s this very turbulent period, but it’s about people who are making something. It has a lot of the kind of excitement and interests that have drawn me in the past. It’s about art making and it’s about fascism and resistance to fascism, which have been the big themes of my work over the last decade.

SB: And cinematic, it sounds like. Maybe a little Paradise Lost. [Laughter]

OL: Yeah, absolutely. Milton invented cinema, Fellini realized Milton’s dream. I mean, I think Paradise Lost is actually Fellini’s great theme, isn’t it? That’s what all his films are about, is this lost paradise of ecstatic childhood, and the difficulties of being an adult in the world. And Casanova is a film about lost dreams and Salò is a film about the horrors of fascism, and the dangers of compliance. I mean, could anything be more relevant right now?

SB: I want to talk utopia.

OL: Okay.

SB: I feel like in this moment we’re in right now, we could all use utopia now.

OL: Yeah. Seriously.

SB: And, “There’s no point looking for Eden on a map,” you’ve written. “It’s a dream that is carried in the heart: a fertile garden, time and space enough for all of us.” You’ve also written that utopia is— That you have this imaginative ability to frame utopias, and then purposely move toward them.

OL: I mean, not me personally, I think we have that capacity. I think—and I feel like I’ve been saying this for a long time—that we have spent too much time and energy in the past decade, or decades, imagining dystopias, and I don’t think that artists should be doing the imaginative work of the right. I think we need to stop doing that, and I think we need to start thinking about what worlds we want to live in, because without having that idea, and that idea being really tangible, really full of detail, it doesn’t happen. You pull in a direction toward something that you imagine—the imagination comes first. I think in a lot of ways, the right have very powerful imaginations, and very powerful skills at conveying those dreams, those fantasies. Fantasies of order, fantasies of discipline, fantasies of control, fantasies of punishment. We also need to be engaged in that work.

One of the major characters in The Garden Against Time was William Morris, the utopian socialist, the great artist. And he saw that that was a crucial thing. He was present at the very early days of socialism, and he wrote this wonderful book called News from Nowhere that really was … let’s call it a seduction. It was written as a seduction; it was written to not lay out a blueprint for a future society, but to try and enter imaginatively into what that society could be like on a sensual level, on a sort of friendship level. What would relationships be like under a changed set of political priorities?

I think that’s the thing that’s really lacking in our world. We’re great at imagining what the end game of our current trajectory is. We all are aware of the sort of road-style horrors ahead. But what we’re not good at doing right now, interestingly and troublingly, is imagining what this thing that we would like to move toward would look like, what it would feel like, what it would smell like, how we would engage with each other inside it. And I think that’s where I really want to engage imaginatively at the moment.

SB: We need this engaging. Something about it to me also has to do with just all of us trying to feel more in our bodies. Something you’ve written a lot about, especially in Everybody, but I would say also in The Garden Against Time; it’s a book about feeling, it’s about exploring a certain sense of paradise, internal and external. You’ve written, “As long as we’re still capable of feeling and expressing vulnerability, intimacy stands a chance.” I kind of think there’s this interesting link between intimacy and utopia, and I was wondering if you see that, too?

OL: Yeah, I think so. I think that’s true. And I think in a way, all of this work started for me with The Lonely City and thinking about loneliness. I think loneliness is really at the core of everything that’s happening in our world at the moment. This sense of people being alienated and afraid, and that being very easily driven into hatred, into separation, into people hiving off into these very disparate, siloed communities. Especially with young men, but with all kinds of people, I think loneliness is at the root of things. And that the answer to loneliness is clearly not hatred. The answer to loneliness is the kind of intimacy that isn’t just about romantic love, it’s about a sense of what I said earlier on: networked thinking. Being part of a community that is beyond human, being at home on a planet, and being tender with each other on this mortal world that we live in. We don’t have much time.

SB: I just feel like this makes sense to say: We’re sitting in this very intimate studio apartment in the Barbican, right? This sort of utopian setting, having a conversation in person, not behind a screen. In the flesh.

OL: Yeah. That was one of the strangenesses of the pandemic, is that everyone had this experience of migrating online, really having to live their lives behind screens, and realizing how much there was this communal longing for physical togetherness. I was writing the body book, Everybody, at that time; it came out at that time, and it felt like there was such a longing for bodily reality. We come out into the world again, with those feelings, and what’s the next thing that happens? It’s like, “Here’s AI. And by the way, there’s no discussion about it. Here it is. This is where we’re going,” almost as if we’ve been sort of rushed into the next kind of chamber of screens without having a moment to say, “Hold on. I have come to my own conclusion. And my conclusion is less of this, not more of this.”

So, I think that’s something that is incredibly important, is to have physical conversation, have conversation with people who don’t agree with you, enter into your community, be around people. And so much of that is about learning to tolerate the discomfort of, “Other people are real, and they’re not identical to us. They have different feelings; those feelings provoke feelings.” That sense of messy discomfort is intimacy. That is what we need.

SB: And the Rilke thing, “No feeling is final,” right?

OL: No feeling is final. Absolutely. Yeah. Feelings are weather, feelings keep changing and—

SB: Funny weather. [Laughs]

OL: Funny weather. It’s funny weather out there, in the human continent.

SB: Well, this I think is a beautiful place to end, which is that, and you’ve written this very simply, “The fundamental thing we all share is the fact of a limited lifespan.” I think this is the thing that really brings us all together. We talk about being human, but actually it’s about time. It’s about, we have a limited amount of time. What are we going to do with it? What are we going to make of it? And it’s not just us, it’s the next generation, and the next generation.

OL: Yeah, and this is, the terrible fantasy of life online is, well, you don’t have to be trapped by your body. You don’t have to be trapped by mortality and temporality. But the fact is, we do. The fact is that that’s what we share. It’s so interesting that so much of what’s happening now is this sort of attack on the physically vulnerable, in very different ways: refugees, trans people. All these different sort of violent attempts to dominate have at their root this sort of terror of physical vulnerability. I think instead, it should be this kind of invitation, that that’s the place where our solidarity begins: with our physically vulnerable, temporal selves.

SB: On the opposite side of that spectrum are these sort of figures, many of them actually in Silicon Valley, who are doing the opposite. They’re trying to live forever.

OL: Well, they want to live forever with their little head in a vat of, I don’t know, what is it? It’s nitrogen, or something. That’s the fantasy: that you can live off-planet, off-body, that you can engage in some pure realm of the mind that is all about power and great wealth. These are ancient fantasies. These are really… The fantasy of having nonhuman labor is a really old fantasy. It’s the golem, that’s what AI is. I feel like these are sad fantasies. We know from fairy tales, they end in disaster. It’s not the best way to live our small time here.

SB: Well, I’m hopeful. I’m maintaining hope. That there’s still—

OL: Spencer’s looking kind of tentative about this hopeful—

SB: … there still can be the—

OL: … but convinced.

SB: We’ll find utopia now, somehow.

OL: I think we have to, but I think also it’s talking, it’s being with people. It’s being open to the constantly changing world. There is always this possibility that things change. None of this is set in stone, and we are actors inside it.

SB: Olivia, thank you.

OL: Thank you.

This interview was recorded in Olivia Laing’s apartment at the Barbican in London on September 26, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Olivia Aylmer, Mimi Hannon, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Suki Dhanda.