Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Hastreiter in her former Paper magazine office.

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Kim, thanks so much for joining us today.

KIM HASTREITER: Thank you for having me.

AZ: A couple days ago, I noticed your email signature that reads, “Kim Hastreiter: Cultural Troublemaker, Original Gangster, People Collector, Idea Machine, Enthusiast, and Co-Founder of Paper.” More formally, you’re known as a journalist, editor, publisher, and curator, but I want to start with the first one, which is “Cultural Troublemaker.” Where are you currently making trouble?

Hastreiter's email signature.

KH: I’m doing so many different things. So I’m making trouble—I always make trouble, I love making trouble, because I’m a punk at heart. I mean, I am working with all these different creative institutions and people and I’m trying to mostly make trouble for Donald Trump, if possible—

AZ: That’s what I was getting at.

KH: That’s my number one cause of troublemaking. I loved what they did with the Presidential seal. I can’t believe I can’t come up with a solution—I’m like a problem-solver. I can’t believe that we haven’t come up with a solution to get rid of this person or do something, you know, have like ten million people go to the door of the White House and demand—

AZ: It’s not for a lack of trying.

KH: I don’t know, I think we’re all—everyone’s really in PTSD, we’re all in this traumatic state of mind.

AZ: Where are you finding the light these days?

“The only thing I’m talented at is to inspire people.”

KH:The only thing I’m talented at is to inspire people. Art is the only place I find light—it’s creating things that inspire people. I want to make the little hairs on the back of your neck stand up, I want to give you goosebumps, I want to help people just kind of put good energy out to counterbalance the racid stuff that’s happening. I’ve been doing that for two years, but it seems it’s just getting worse. It feels like no matter what I do, nothing—I don’t feel hopeless, but it’s just getting worse. It’s tipping the wrong way, it’s not tipping the right way.

AZ: Have you decided who you want to support?

KH: I’m supporting everyone. I’m working for Pete Buttigieg because I love him and I want his voice to be heard, and I know he’s problematic. That’s who I’ve kind of gotten behind, to help him—and I love like Stacey Abrams. My dream fantasy was Pete Buttigieg and Stacey Abrams as a team, but she wasn’t running for president.

AZ: So a little bit of politics, book publishing, curating—you’re doing a lot of different things.

KH: But I’m also doing books, I’m making books. I’m writing four or five books now, working a lot with Creative Growth Arts Center [in Oakland], curating a lot, doing a lot of curation. I have a lot of ideas. I want to do some museum curating—it’s really hard. I have some insane ideas. I want to start this nonprofit. So I’m doing, like, a million things.

AZ: Which after thirty-three years of running Paper magazine, which you co-founded with David Hershkovits in 1984, is a big transition.

KH: Thank God.

AZ: One of the things I really want to talk about is that moment of re-entry. I think that whether you ran a magazine for thirty-three years—whatever it is, in life, we have these moments where everything changes. What was that like, like day one?

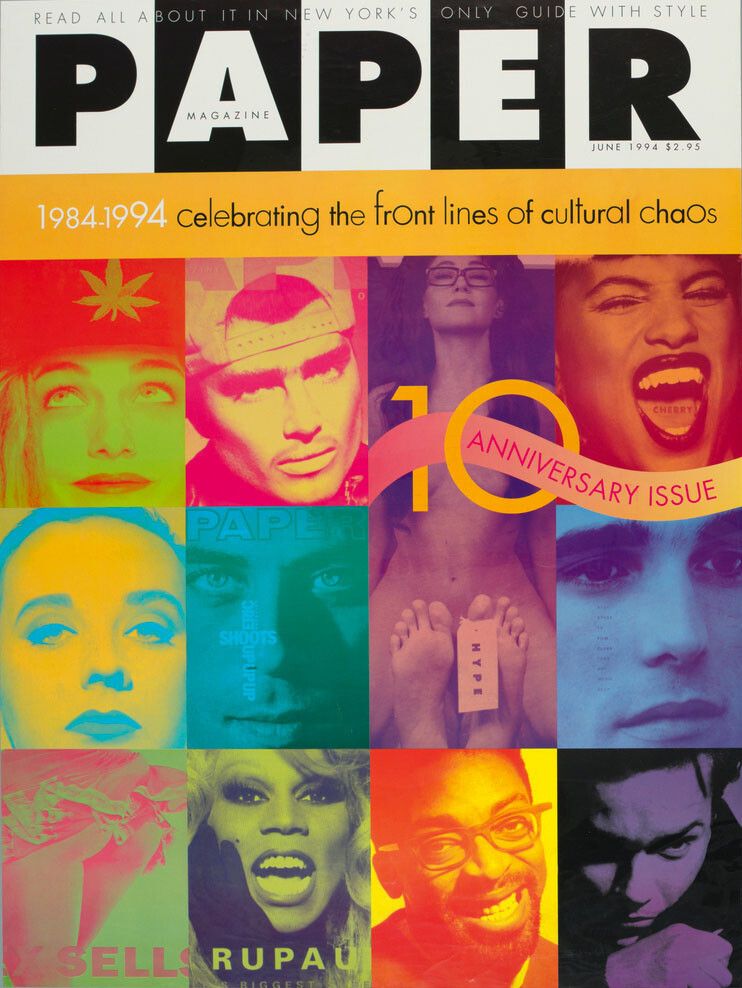

The cover of Paper’s 10th anniversary issue, from 1994. (Courtesy Paper)

KH: Well, really, it changed four years ago—five years ago—when I realized that all I was doing was dancing as fast as I [could] to keep the doors open. I wasn’t doing anything that I loved anymore. All I was doing was managing people and scrambling to get enough money to pay everyone’s salaries. And every month it was a shit show of “How am I going to get this money?” and I had to hustle.

I was just hustling, and I was just exhausted from it. It’s exhausting because, you know, a magazine is not a business model anymore. So I had clients and I was doing everything to try and bring in the money—with help, I had some help. But I mean, it was so much pressure, and I wasn’t doing what I do. I’m an artist, I’m creative. I wasn’t able to do any of the things that I loved anymore. And I was caring for my mother who was sick.… She was older, and she was sick. So those two things, it was like a sidebar, it was like a full-time job with my mother. She lived in New York, but I had to get her into a place—it was a whole thing.

Then to try and sell Paper or get out of Paper, I had a wonderful person who was working for me who was a visionary, [with a] completely different vision from me, who worked for me for many, many years, and was really great, brought in a lot of money, had really creative ideas. And I just said, “You should have Paper. Do you want it, Paper?” And he was like, “Yeah,” so I said, “Okay, well, let’s make a plan.” Because Paper was kind of me, in a way, partially. Like I was going to leave, what are you selling, right, you need to sell people, it’s really people, because Paper was like ideas. I had this amazing person named Drew Elliot who now is one of the owners of Paper. So that was my scheme, was to figure out, with Drew, how to sell it so then he could be an owner.

AZ: So then you sold it.

KH: I sold it, yeah, but it took, like, four years. It was really hard.

AZ: But then one Monday morning—

KH: I sold it, and my mother died two days before I sold it. So it was all happening in the same week. Yeah, it was crazy. My mother died, and then two days later, we signed the deal.

AZ: So what was that Monday morning like, when life’s completely different?

KH: After? Well, yeah, because when you sell something, you go into contract, and when your mother dies, you still have to empty out the apartment. So it was like a month. So you sign the contract, and then in a month, you close, because they have to do all this stuff. So when you sign the contract and you sell it, then you have to put out a press release. Then my mother died… I had to deal with that, it was crazy. It was a crazy week. I wasn’t going to be relieved until the next month when it closed, so then when we signed the deal, the new owners of Paper said, “Well, you know, next month, on that day when we’re closing, you have to get all your stuff out. It all has to be gone because we’re going to renovate the office,” which—it’s theirs, right? So I was kind of like, “Oh, shit,” and when my mother died, the place that she was living, which was kind of like a wonderful assisted living on Chambers Street, said, “You have to vacate in a month.” So I had these two things I had to vacate in a month. So that was really the intense week, or day, when I went and we closed with the lawyers and we gave the keys and then I had moving people, they moved it all into my apartment. So I moved everything from thirty-three years of Paper into my apartment, and then I moved everything from my mother’s house into my apartment, like all in the same week. So my apartment, you couldn’t even walk into. I had furniture and I had to—in a way, I just had a lot to deal with physically.

AZ: When the dust settled, when you were finally kind of like, “Okay, this is the new life…”

KH: Yeah, so it took me like—it was good because I had this kind of like physical thing to do. I had to get rid of stuff, I had to edit, I redid my apartment—so really it took until like March. I had my new apartment, I edited it, I sold a lot of shit, I gave stuff away. In March—and then I had these ideas, in the meantime, I was like, “Oh, my God,” because I’m very interested in the food and chef kind of thing. That was kind of a cultural movement that I got very involved in, that I’m very interested in. These people came to me and said, “We have this space, would you be interested in kind of creative directing what we’re going to do with it?” Like, make a restaurant. I was like, I never want to have a business again, I never want to have a job, I never want to manage people again. I’m done with it. So I said, “No,” but then I started thinking, “I could do such great things if I had a restaurant.”

So I got this crazy idea that I wanted to do this nonprofit cafeteria in Manhattan and raise money to give grants to people with amazing ideas. Because I use the word amazing a lot—I love ideas. That’s what my whole career has been about. Amazing ideas that, as I said, will give you goosebumps, will make [your] hair stand up on end, will make your heart stop. I love that. And I do that a lot. That’s what I strive for—I strive to have that moment of like, “Oh, my God, this is so good.” So I’ve done them in my career, and I’ve been kind of like a hustler where I would raise money to execute these ideas, so I would find other people to pay for them, and I did tons of them—I’m actually making a book about all of these things. But other people have amazing ideas, but a lot of people with amazing ideas never execute their ideas. So I want to give grants to people with amazing ideas. I made this little committee, I did all this work. I wanted to come up with an amazing idea in order to raise money and I would change it, so it would be like an ongoing, kind of like a nonprofit foundation. I talked to people about giving grants, I kind of got it conceptually together, but then, [for] the actual operation, I would come up with these different ways of making money, and the first one was to open this cafeteria. I wanted to do a pop-up, and I got every great chef in America to sign up.

AZ: I’m sure.

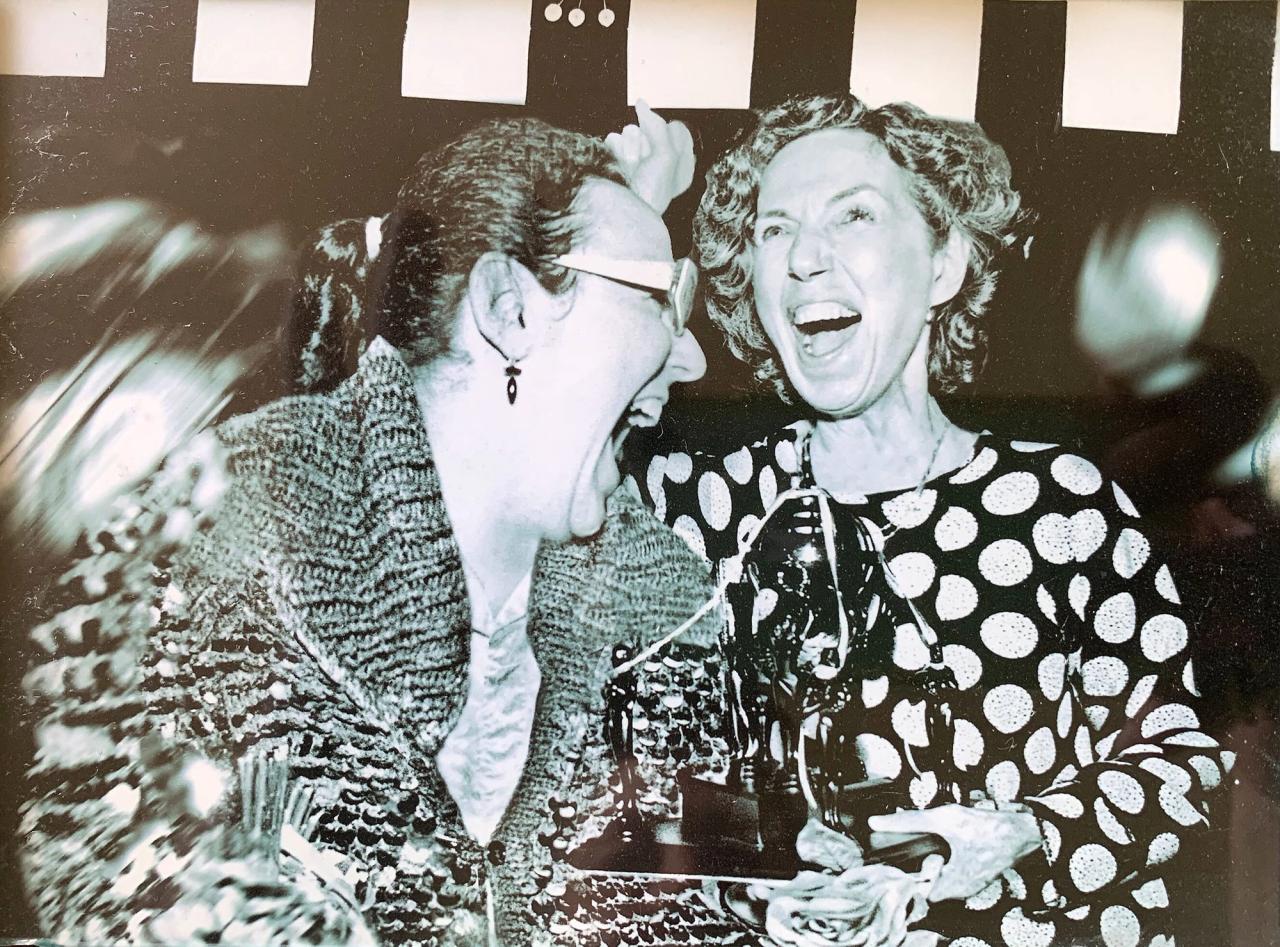

Hastreiter and her best friend, Paige Powell.

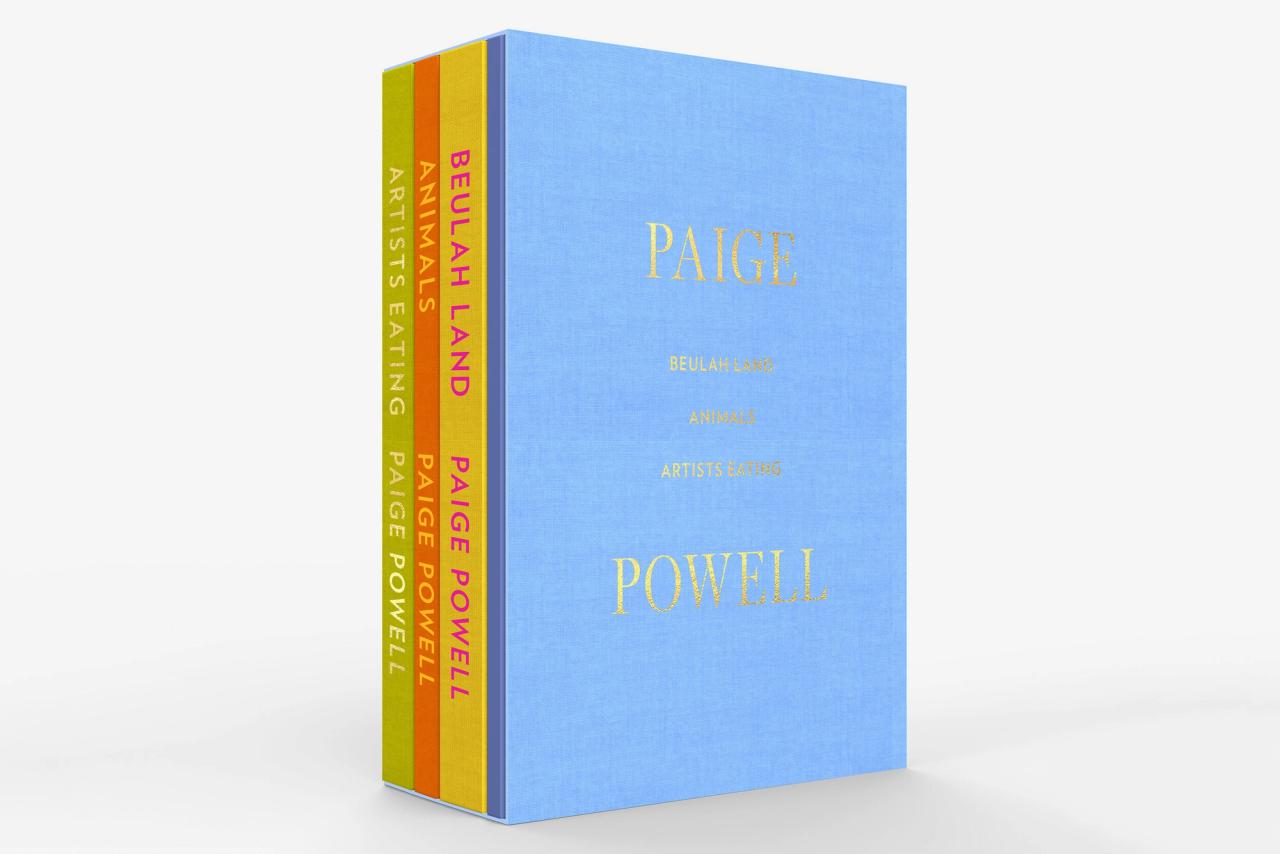

KH: It was going to be the best. So I had this whole plan, and I went to get my nonprofit status, and it was really fucking complicated. They said, “You can’t have a nonprofit if you’re going to have any kind of a business. You have to own the business.” So I was like, “I’m not owning a business. I don’t want to own a restaurant. I don’t want to do this. I’m only doing it for a year.” I only wanted to do it for a year. I said, “And then I’ll do something else, maybe I’ll do a store…” So I said, “I’ll even do it for six months.” What’s the difference between me doing a pop-up restaurant to raise money and someone doing, like, a fundraiser? But they were like, “No, you have to make it a business and you have to pay taxes—” I mean, the whole thing, it was so complicated. So at that point, I was approached to do these books about my best friend, Paige Powell. And it was four books. She is one of my dearest friends, and she worked with Andy Warhol and photographed and documented from 1980 to 1992.

AZ: The most amazing images.

KH: Right, did you see the book?

AZ: Of course.

KH: Yeah. So she had all the negatives and contact sheets in a garage in Portland. For years, we had been trying to get them out and trying to get them archived, and she was approached by Gucci to do something with them. And she said, “I want Kim to edit the books.” And so we came up with this idea to do this box set and do four different books. I had only like four months to do it. They were like, “Can you do four books in four months?” Because they wanted to do one every four months, and I was like, “No, that’s not good. We have to do them all together, a box set.” But I’ve done magazines. I do a magazine in a week, so I can do a book in a week. I’m really fast, I’m a really good editor. That’s what I’m the best at. Give me like a thousand pictures, [and] I’ll find the best two pictures in like a half hour. Or send me into the biggest thrift store on Earth—I’ll find the Hermès scarf. I’m really good at that. I’ll interview a hundred people, and I’ll find the one best person. That’s something I’m really good at: finding the best whatever. So I went to Portland, you know, my eyes aren’t what they used to be, but it was all contact sheets and those looking glasses, whatever they’re called—

Paige Powell’s book that Hastreiter collaborated with her on.

AZ: Loupes.

KH: Loupes. And I start editing, and this wonderful art director I was working with that Paige found named Nathaniel Kilcer—who I loved, turned out he was fantastic—because the art director is really important. So I did these books and I did them in four months, we did four books, and I had signed all the—

AZ: Which were exquisite and were loved when they came out a few months ago, and it was kind of an amazing first big project. What I’m curious about is how your sense of time changed when you were not on this production schedule. I mean, for thirty-three years, you were on a very regimented schedule. Even though your life was not necessarily like that, you were in production—I mean, people talk about this when they come out of films, when they exit sort of big situations—

“Paper was kind of very loosey-goosey. I never had a normal business. It was like a family—everyone was like crazy there.”

KH: But Paper wasn’t like that. Paper was kind of very loosey-goosey. I never had a normal business. It was like a family—everyone was like crazy there.

AZ: You started out of a house.

KH: It was in my house. And even in the office, there were dogs running around and barking and pooping on the floor. It wasn’t like a normal place. Now, it’s much more normal—they have rules and whatever. People came in whenever, my door was always open, anyone could come in my office, I would scream at people to get their attention—everyone always made fun of me because instead of calling somebody I would scream for them, you know—so there was always me screaming, it drove people crazy. So it was never regimented, I could go whenever I wanted. It was my own business, so—

AZ: Yeah, but you still managed to be in that production.

KH: Somehow the joy of doing these issues—because I couldn’t really do what I used to do—became less. It all became like, you had to put celebrities—I don’t like celebrities. I never did celebrities, and I’m not good at that, you know what I mean, unless it’s like an idea.

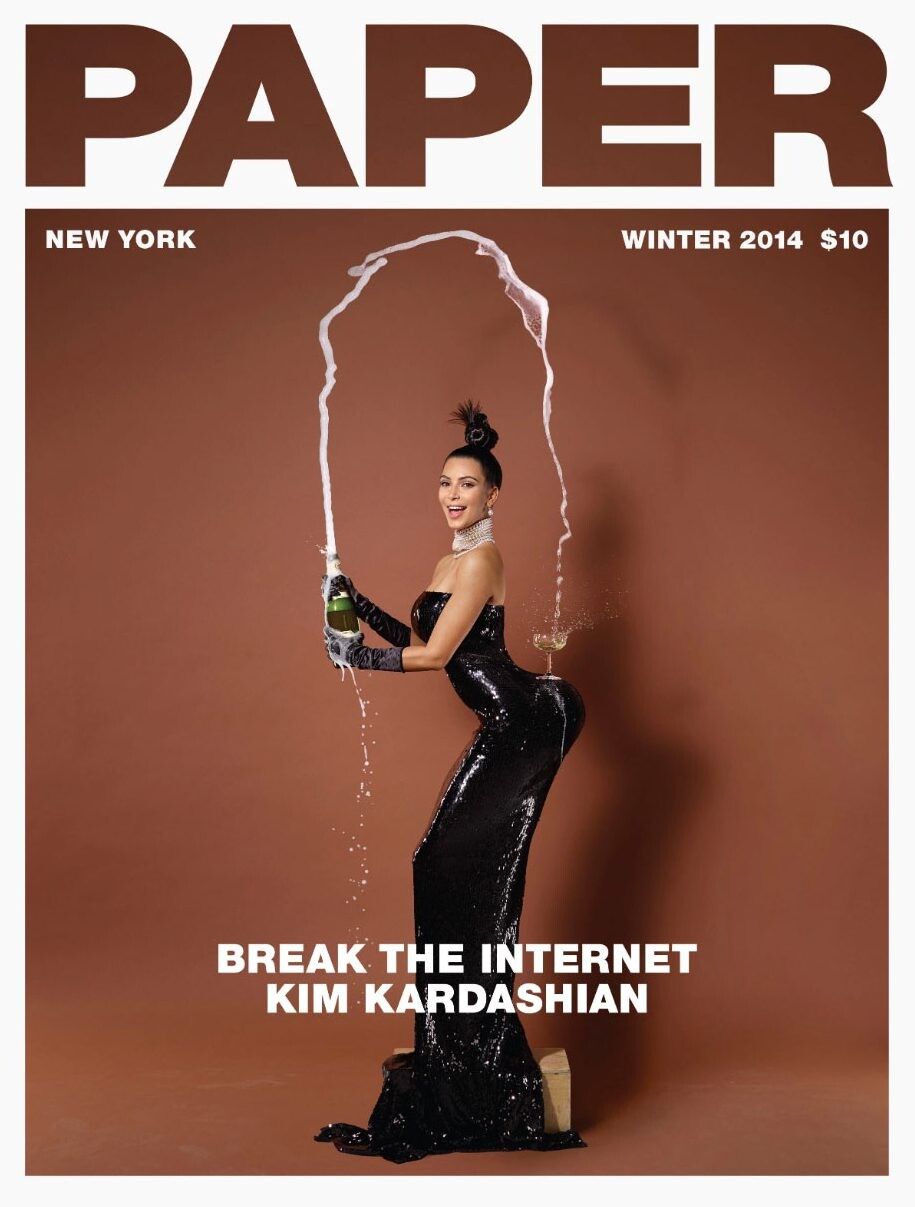

AZ: Like when you “broke the internet.”

KH: Well, that was like an idea that really Drew had, but I kind of tweaked it to make it—because he wanted it to be our thirtieth-anniversary issue and he wanted Steven Klein to photograph it, so I kind of helped a little bit because Jean-Paul Goude is my hero—

AZ: I mean, conceptually, such a brilliant, brilliant moment.

Kim Kardashian on the Winter 2014 cover of Paper. (Courtesy, Paper)

KH: Right? But it was Drew’s idea to do a whole issue about “Break the Internet” because I rejected—he wanted to put Kim Kardashian on the cover of our thirtieth-anniversary issue, photographed by Steven Klein. I said, “Over my dead body” are we going to put her [on it], she doesn’t represent thirty years of Paper, she’s not Paper. Turns out that Drew and Mickey had already told her she could have the cover, so they got really freaked out because I said no. They went downstairs, [and] a half hour later Drew and Mickey came up and said, “We have an idea. We’ll do the next issue after the thirtieth anniversary and we’ll put her on the cover and we’ll make an issue called ‘Break the Internet.’” It was totally Drew’s idea. “And everything in the issue will be about breaking the internet.” I was like, “That’s a genius idea, I love it, yes. A thousand percent.” It was a genius solution. Sometimes you come up with [big] ideas because of big problems.

AZ: You need a solution, yeah.

KH: And that was so much better of a solution than her being on the cover of our thirtieth-anniversary issue.

AZ: And then the Jean-Paul Goude…

KH: Well, so what happened was, they had already asked Steven Klein—who I didn’t think was the right photographer, in my mind, they knew. But then Steven, I think he broke his wrist or arm or leg or something and he couldn’t do it, so I was kind of like “Oh, thank you.” So Jean-Paul Goude—he’s like my hero, he’s one of the reasons I started Paper from George Lois days—George Lois discovered Jean-Paul Goude. And I know him, and he did a whole book of asses, it’s always been about asses for him. I was like, “He is the one.” So he calls Jean-Paul in Paris, he said he would do it. He’d never heard of Kim Kardashian, which I loved. And then, really, Drew and Mickey went to Paris to the shooting, and Kim Kardashian—this is good because she was in between management and PR people, so she didn’t have anyone firewalling her at that moment in time—it was a blessing, because those are people who are like cockblockers. They prevent anything good from happening, all those PR people—they’re there to say “no.”

“Those are people who are like cockblockers. They prevent anything good from happening, all those PR people—they’re there to say “no.””

So we were really lucky, and Kim came to the shooting. Mickey [Boardman], Drew, Jean-Paul, his assistant, Kim, and she just brought her makeup and hair. And that was it! There were no cockblockers there. So Kim, who was really nice, she was just game. And she also always has to approve the photographer, but someone told her, I forget who—maybe Kanye said, “Oh, Jean-Paul Goude’s good,” because he did the Chanel, you know. So they approved using him, which … thank God. I mean, literally, Mickey called me and said, “She just took off all her clothes.” And Jean-Paul does these drawings, and he has it all prepared, he wanted to redo that shot of the champagne.

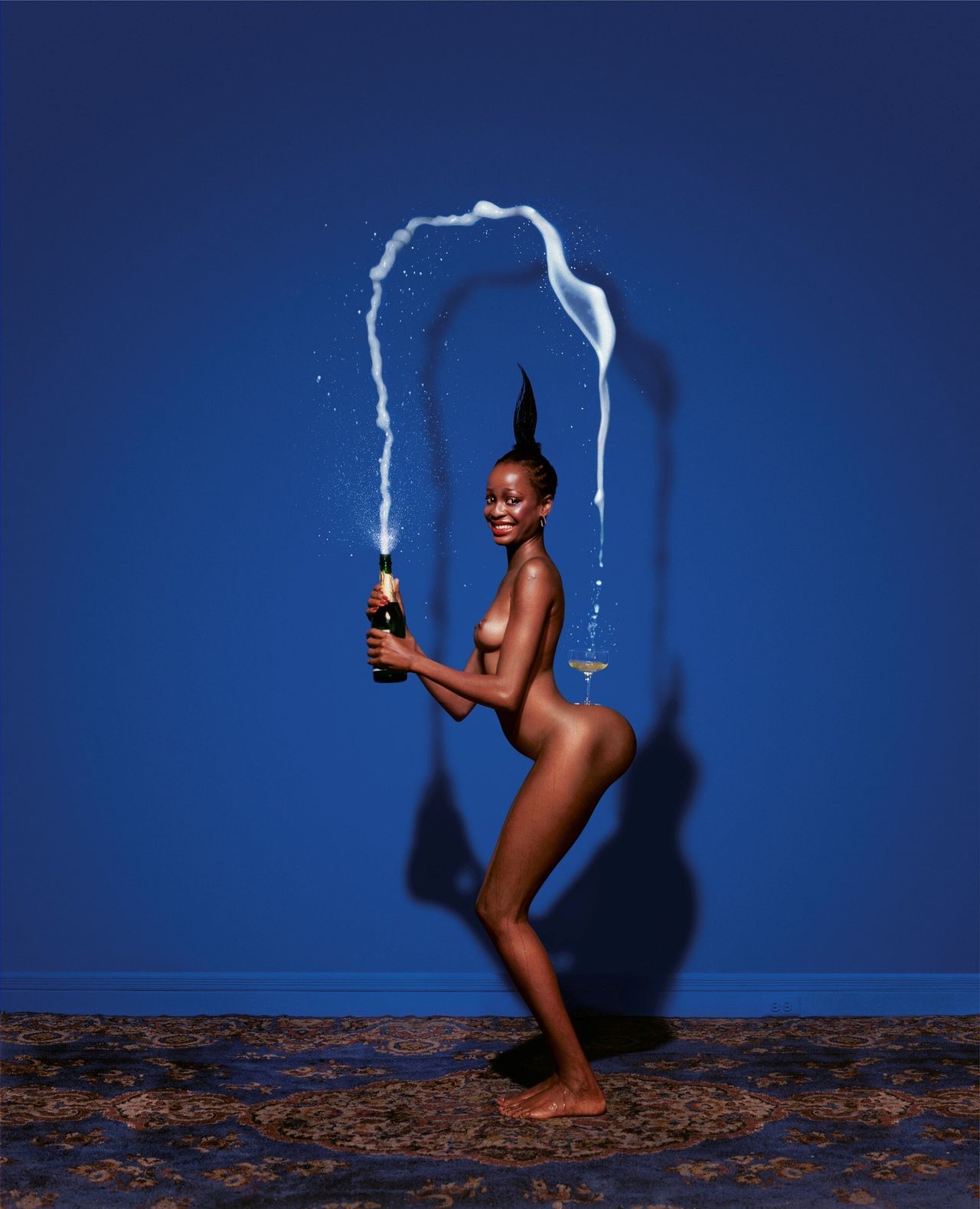

AZ: Which, conceptually, was fascinating.

KH: It was perfect.

AZ: I mean, that image was made in the mid-70s, when the ideas behind the internet were just being born.

KH: And also, Jean-Paul was before Photoshop. Everything was done with airbrushing, all of Jean-Paul’s stuff. And then he showed how he would enlarge people’s butts and enlarge their breasts and it was very, you know, in a way, now, we probably maybe couldn’t have done that this year, because it’s racist, if you look back at it. It’s really dicey in a way, Jean-Paul, what he did is considered racist now.

So it was just one of those miracle moments where no one was cockblocking, and it was a true, pure—they had this drawing, Jean-Paul wanted to do a spread in the magazine with Kim, naked, bending down, looking at the camera through her legs, like a total two-page ass shot, but nude. And Kim was like, “I’ll do that.” She would do anything. So when they got these shots and she took off her clothes, they had frontal everything, completely. After the champagne shot, she started playing with it, and we had all those shots, so Jean-Paul was like, “Oh, my God, these are so good,” everyone was like, “Oh, my God,” and they were going to finish up and she said, “Aren’t we doing that other one?” She wanted to do it. So they were kind of like, “Okay…” She was that game.

AZ: To break the internet, I figure you have to be—

KH: So she did it, and Jean-Paul—she did that shot. And it exists somewhere. I’ve never seen it. And Jean-Paul, who is outrageous, said to us when he sent us the pictures, I was like, “Where is that shot?” He said, “Kim, if you want to go to the gynecologist, that’s what that shot was.” He said, “All the other stuff is so great—you don’t want that,” which I thought was so great that he did that.

“Carolina Beaumont, New York, 1976” by Jean-Paul Goude, the original work that the Kim Kardashian cover was based on. (Photo: Courtesy Jean-Paul Goude)

AZ: Well, it was a real moment in time and became a massive meme, and one of the—

KH: And then in the issue, if you read the issue, every story—we did The Fat Jew, we did everything about asses and every person that was breaking the internet, and that was really Drew’s specialty. Drew was kind of like a genius at viral… You know, it was his idea, “Break the Internet,” that slogan, everything, that was Drew. So I kind of helped it along, but after that, I just kind of gave it to Drew. I said, “Drew, it’s yours.” So then Drew was kind of doing the issues, he started doing them, and then I was trying to sell it. I was just kind of stepping back a little and letting Drew—his aesthetic and everything is different from mine, but it was more, I guess, what people wanted from a magazine. I didn’t know, they didn’t want me, doing my underground shit, that wasn’t going to work. So I knew it wasn’t me. I kind of shifted out even though I wasn’t out, and I focused on how I was going to exit. It’s really hard to exit.

AZ: Yeah, but you did it really beautifully.

KH: What I love is that Drew, someone who was an intern that worked there for like fifteen, seventeen years, took the reins. Isn’t that cool?

AZ: It’s real art when it lives beyond you.

KH: Right?

AZ: So one of the things I wanted to talk about with you is collecting. Because you’re an incredibly unique collector. There are many collectors in the world. It’s generally based on monetary things—not for you. You save things for a different reason, for narrative storytelling. I want you to tell me a little bit about your feelings on the power that objects have to transport us to time, to tell stories.

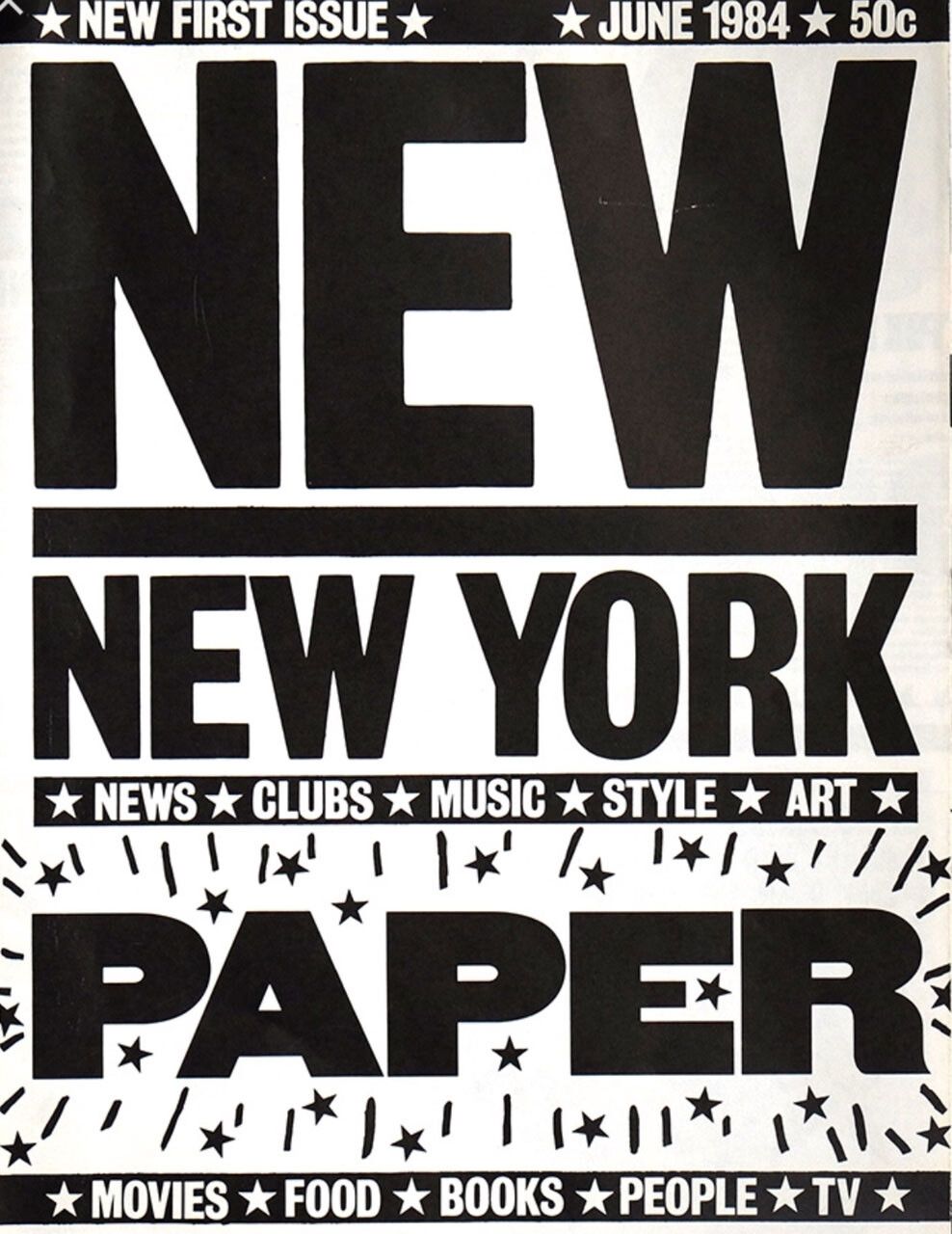

KH: For me, I feel like my life, I have witnessed such huge, shocking things. When I started Paper, there were no computers. I was on a typewriter, we [used] fax machines, we would use matte knives, there were no computers, there were no cell phones. The fax machine was a huge thing. There were no computers! Can you imagine?

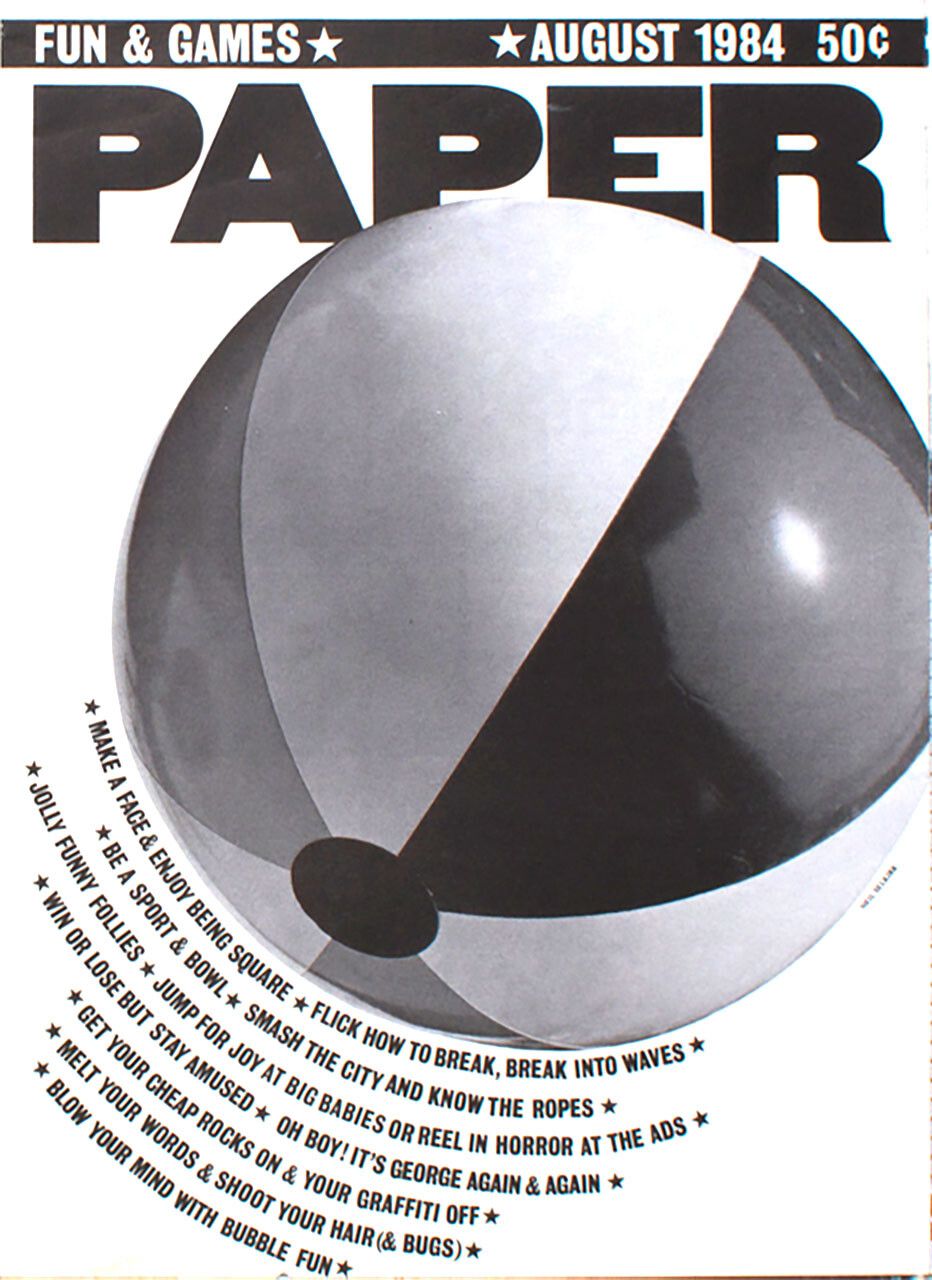

AZ: It was 1984.

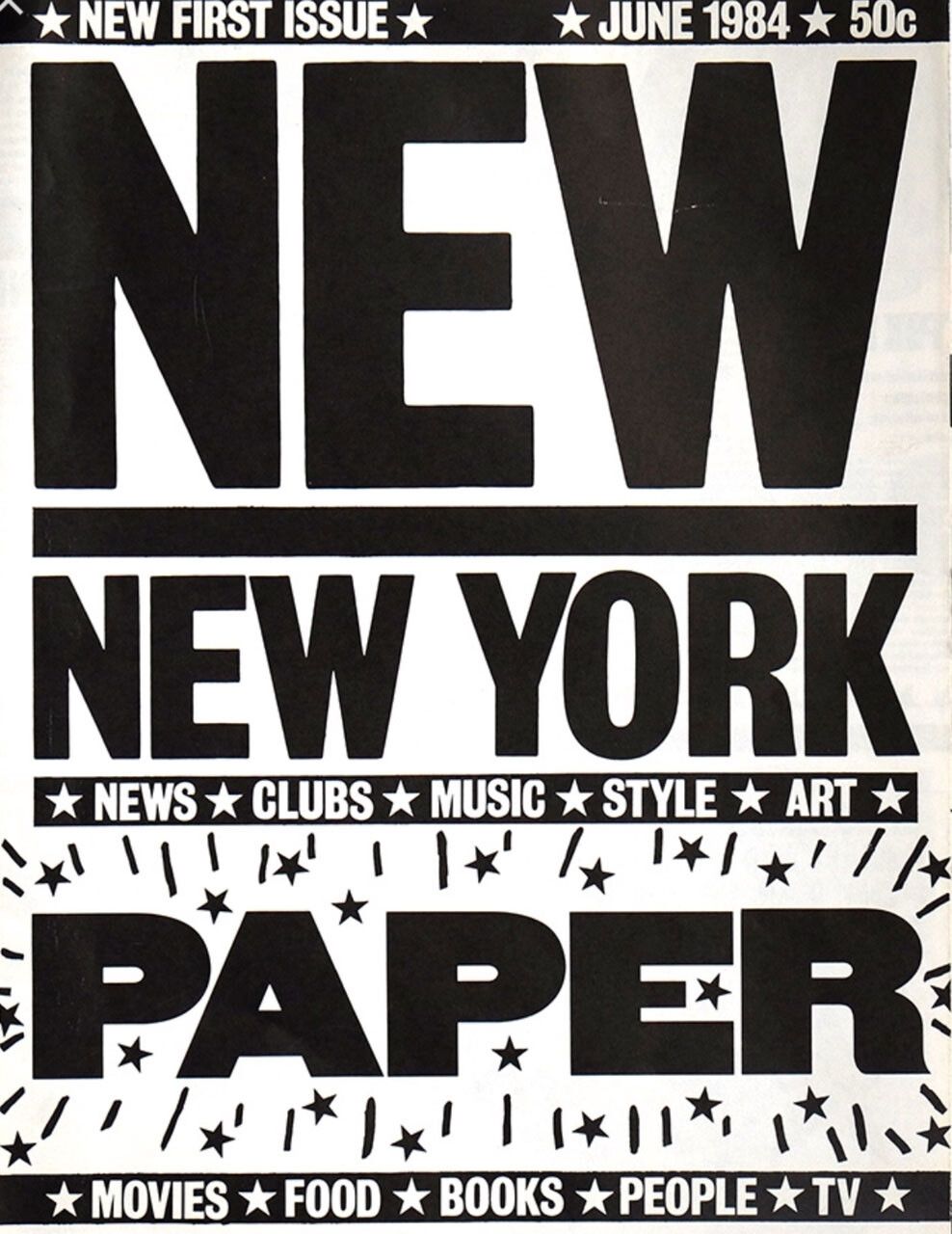

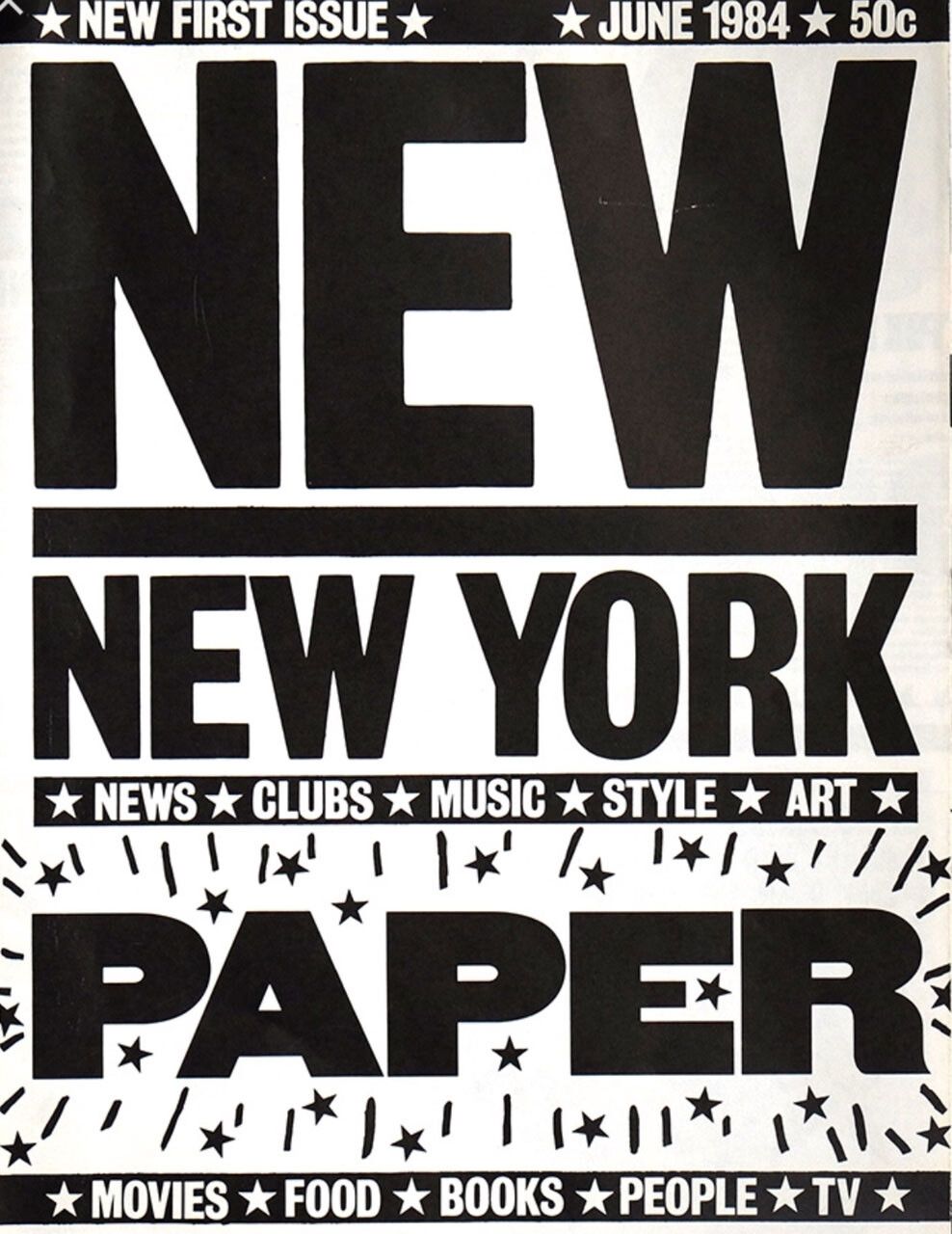

Cover art from Paper magazine’s first issue in June 1984.

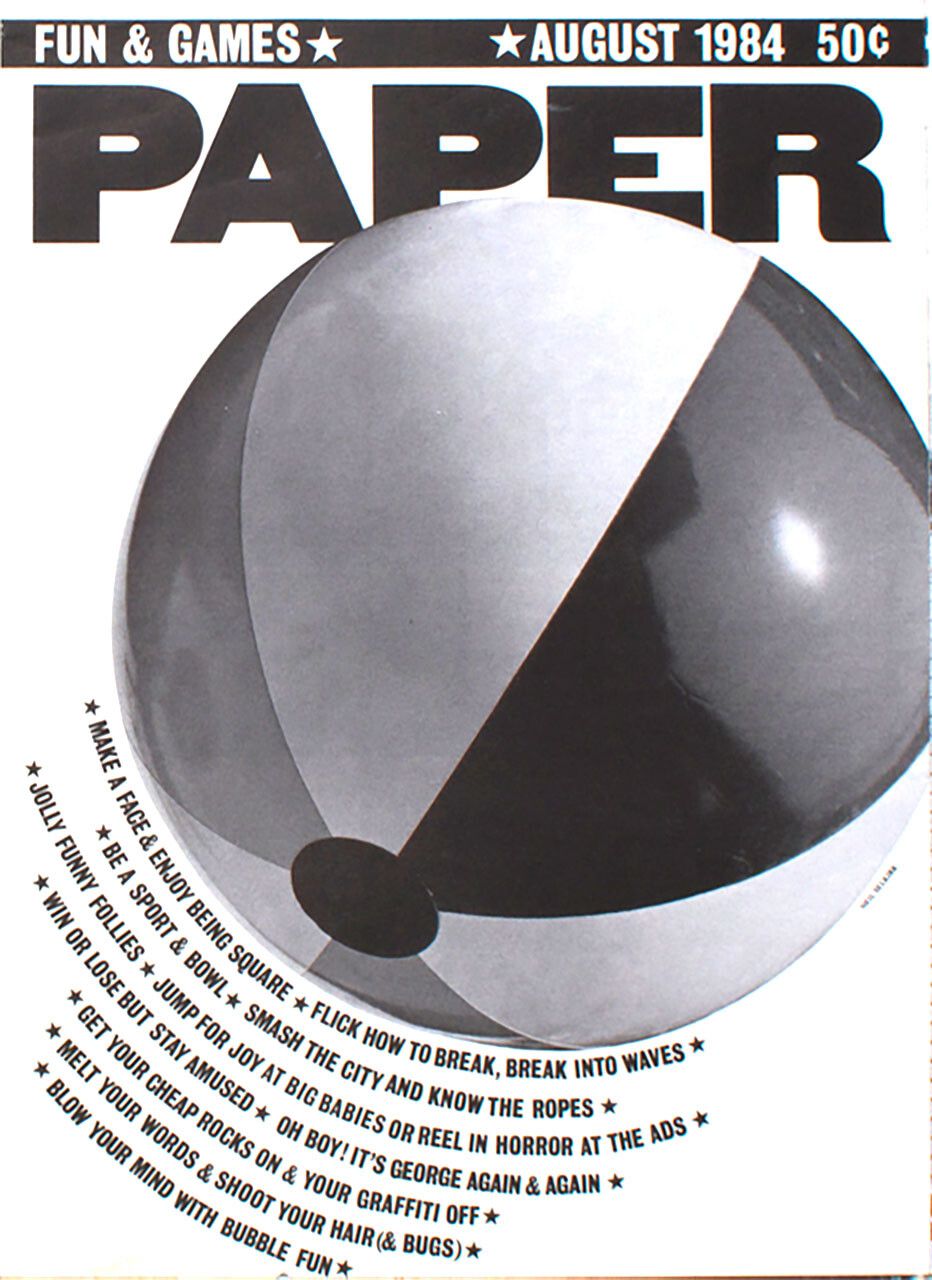

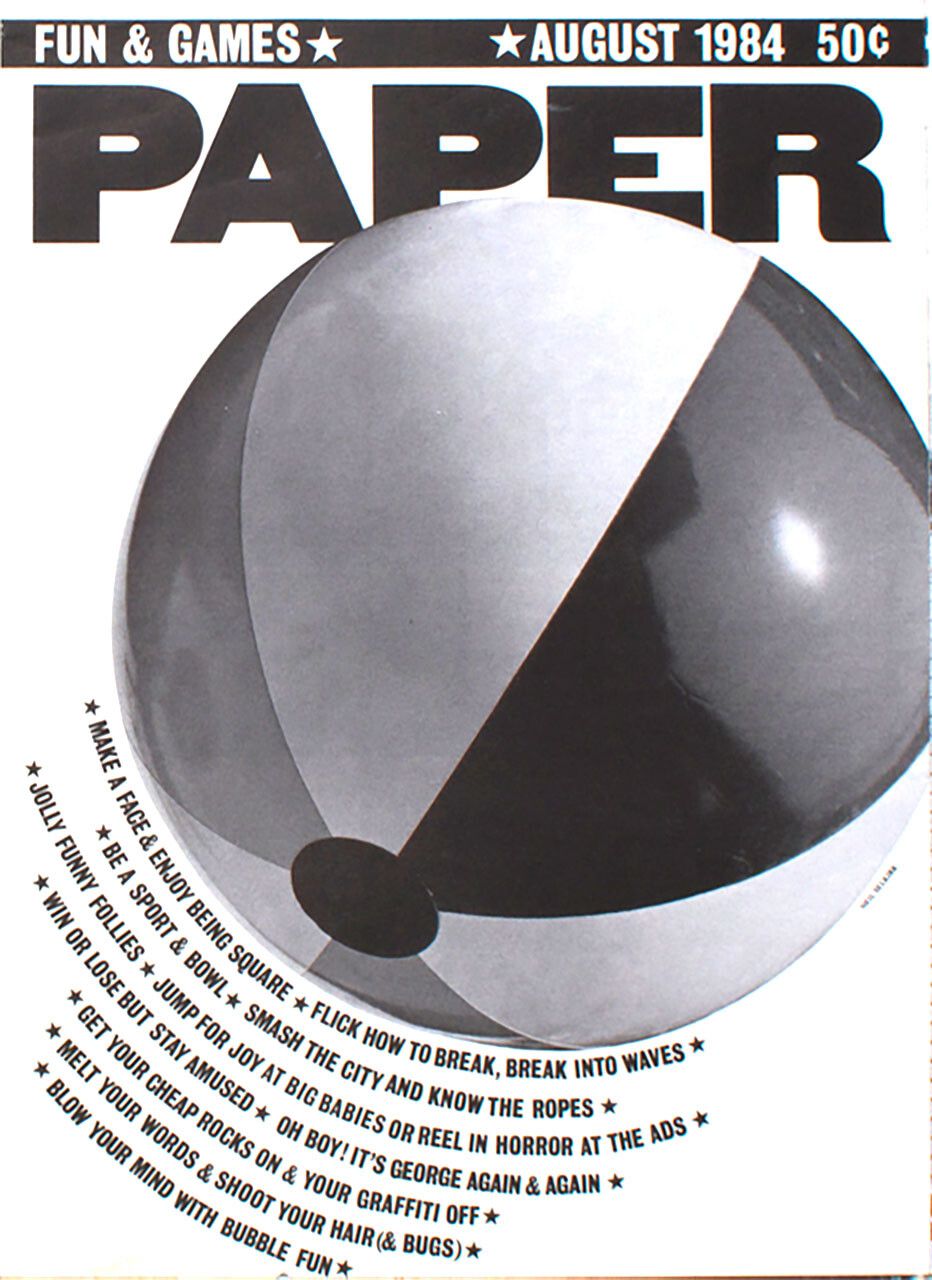

Cover art from Paper magazine’s August 1984 issue.

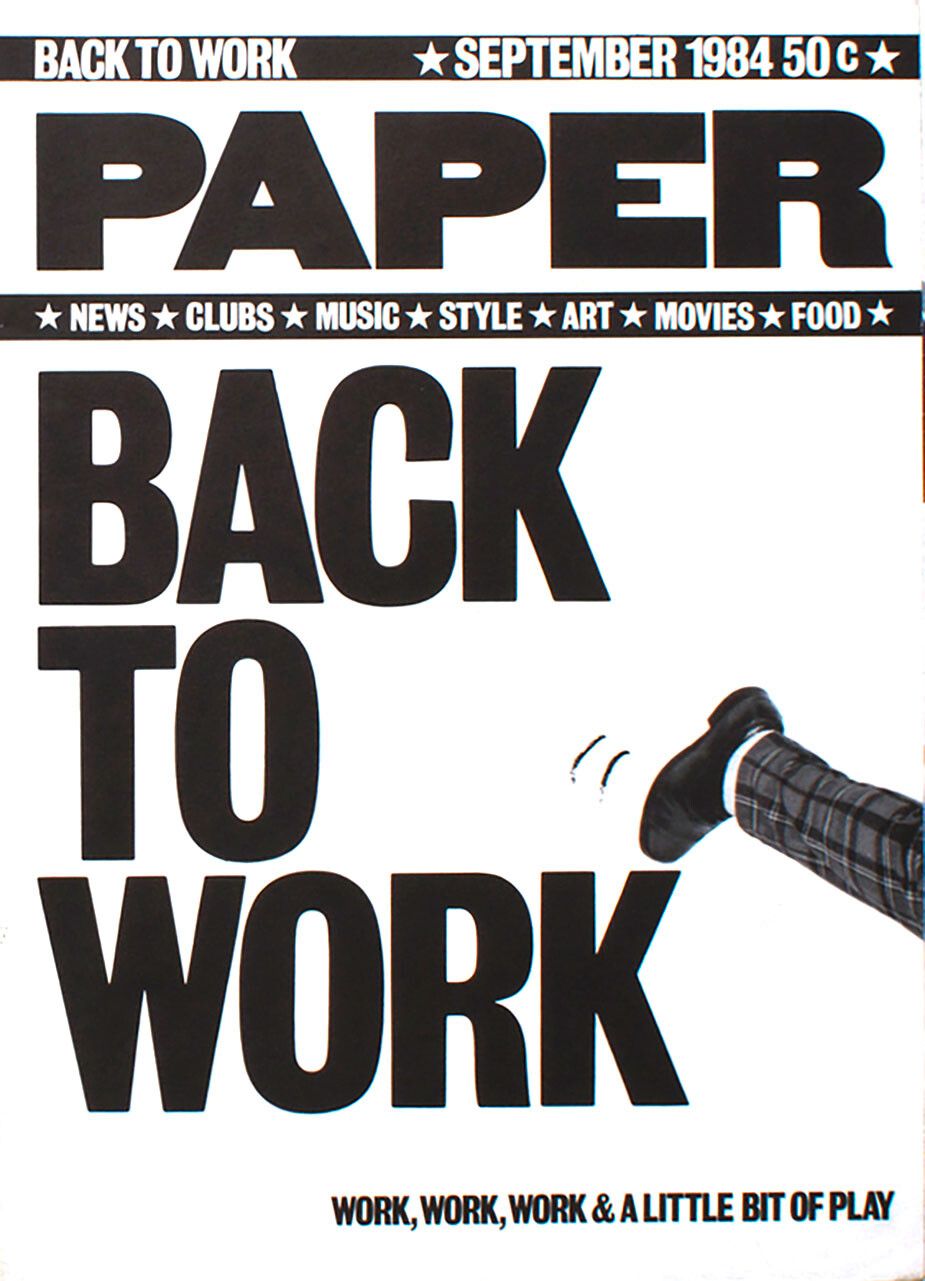

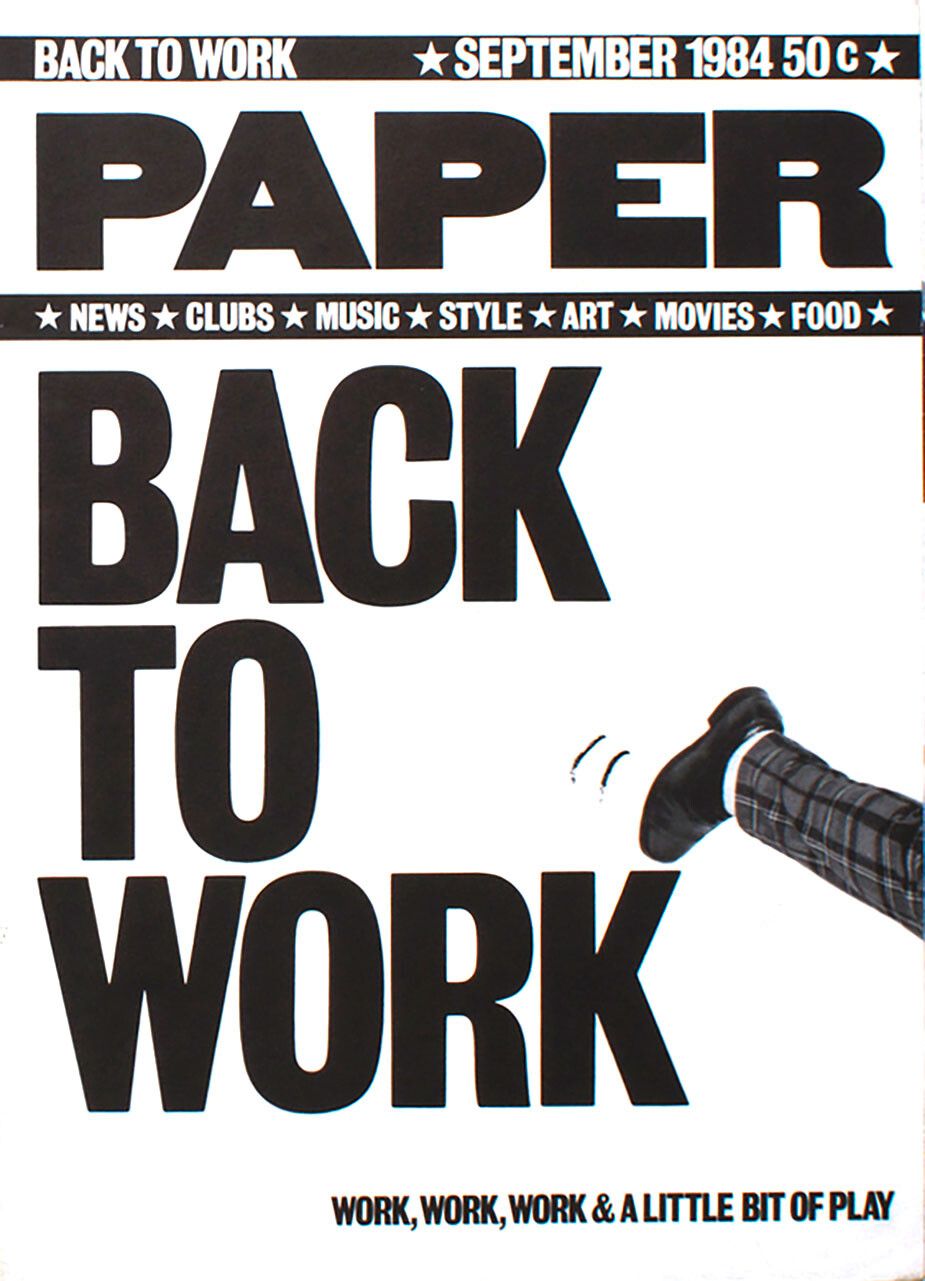

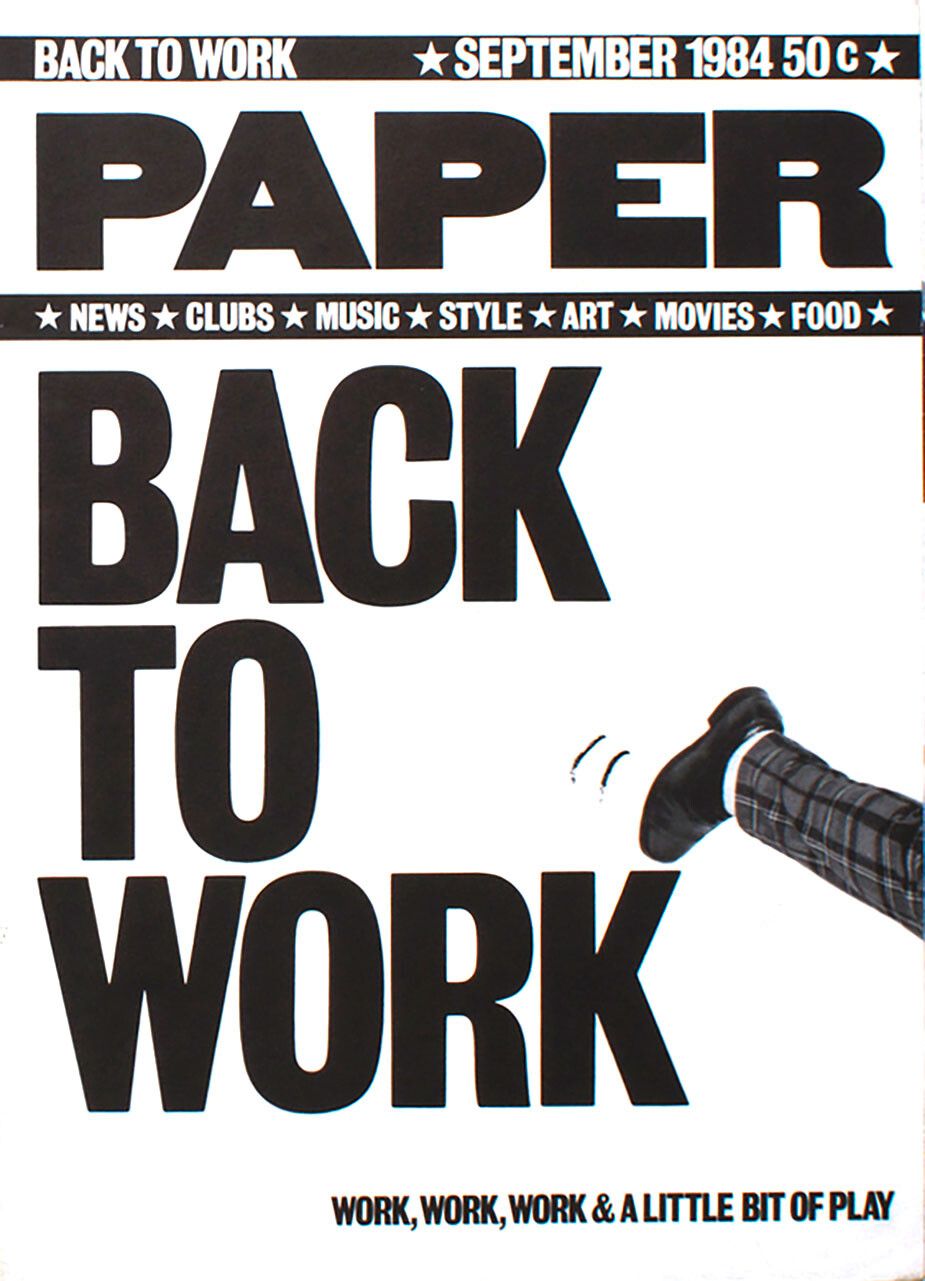

Cover art from Paper magazine’s September 1984 issue.

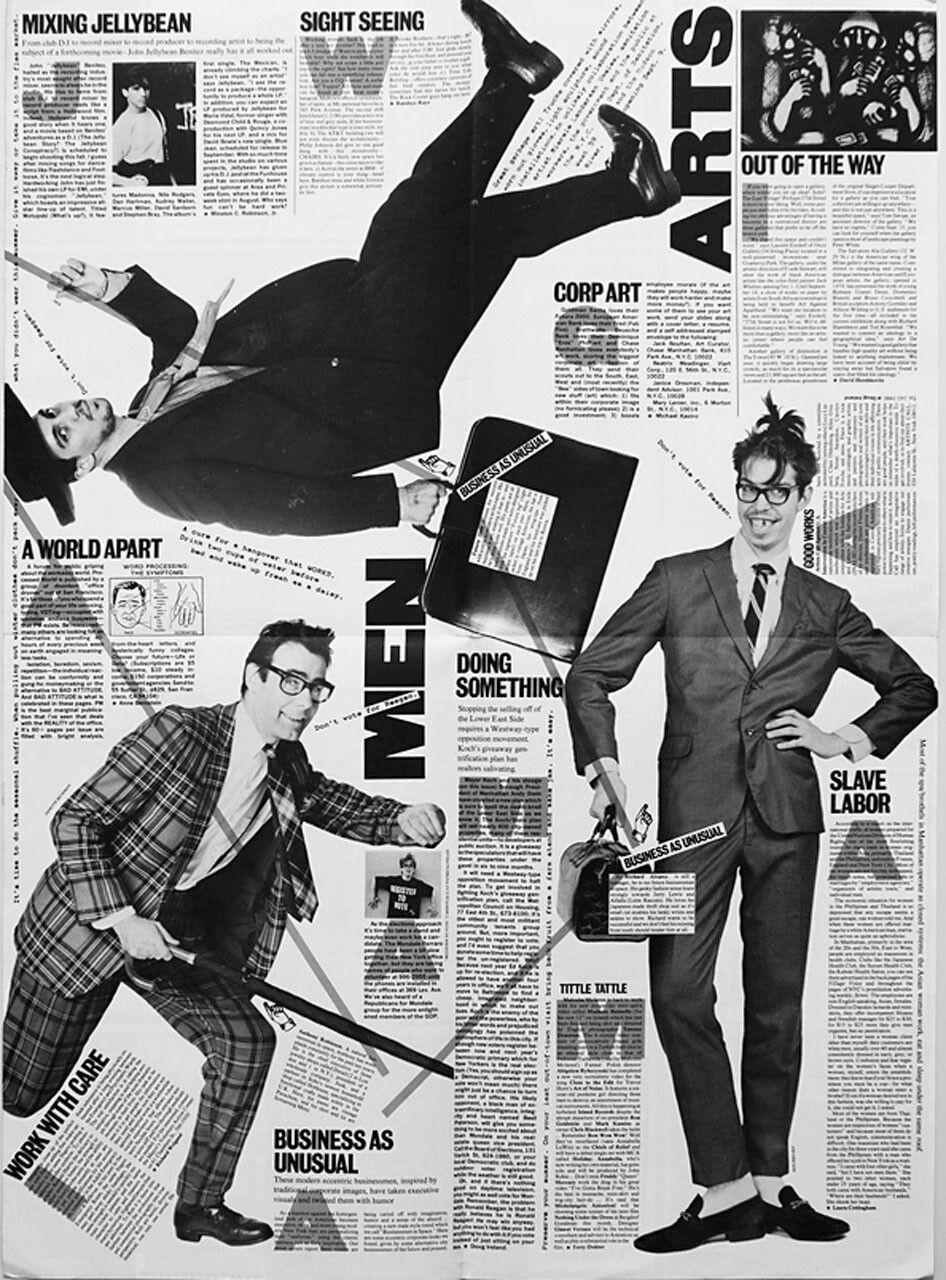

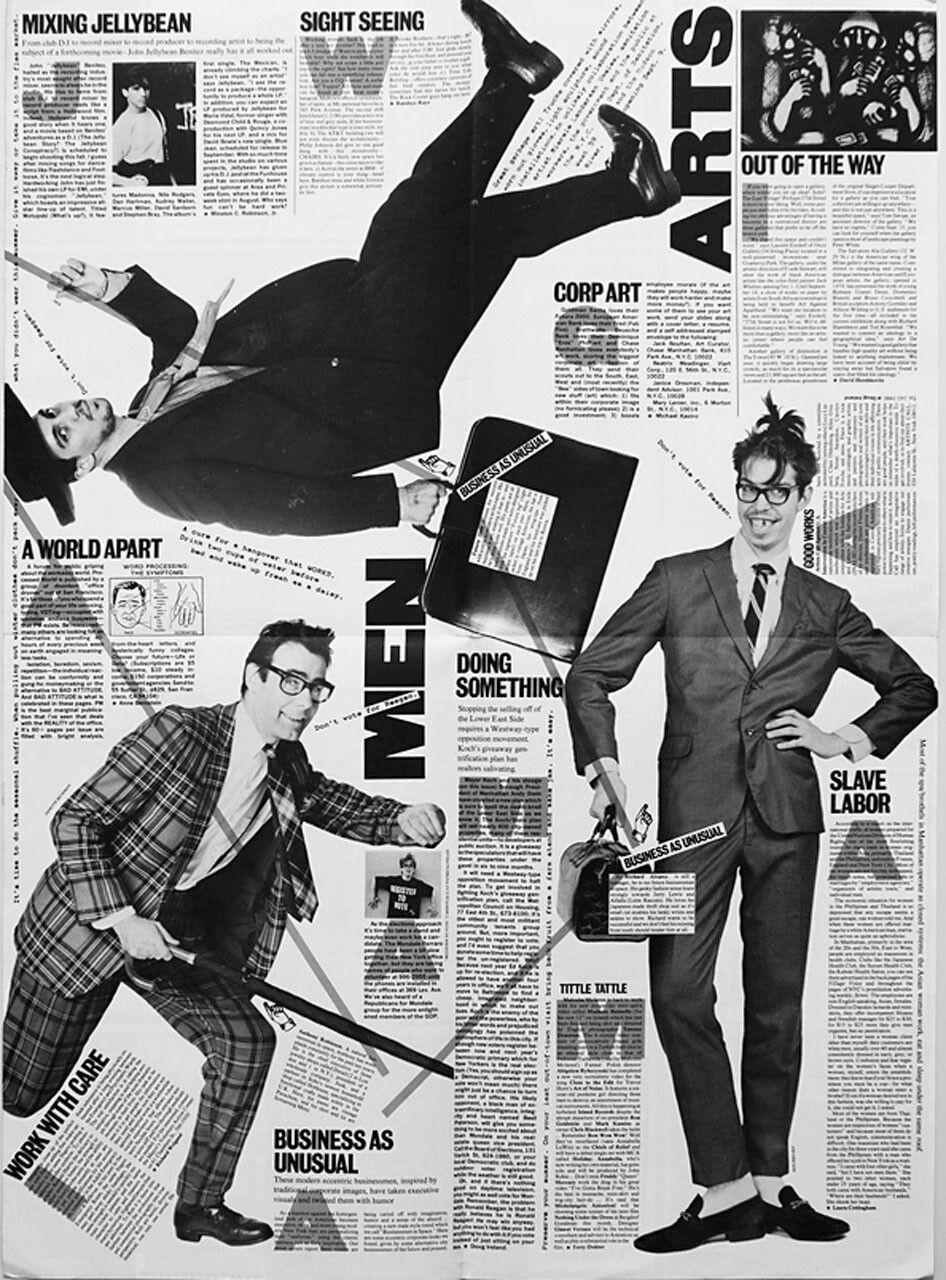

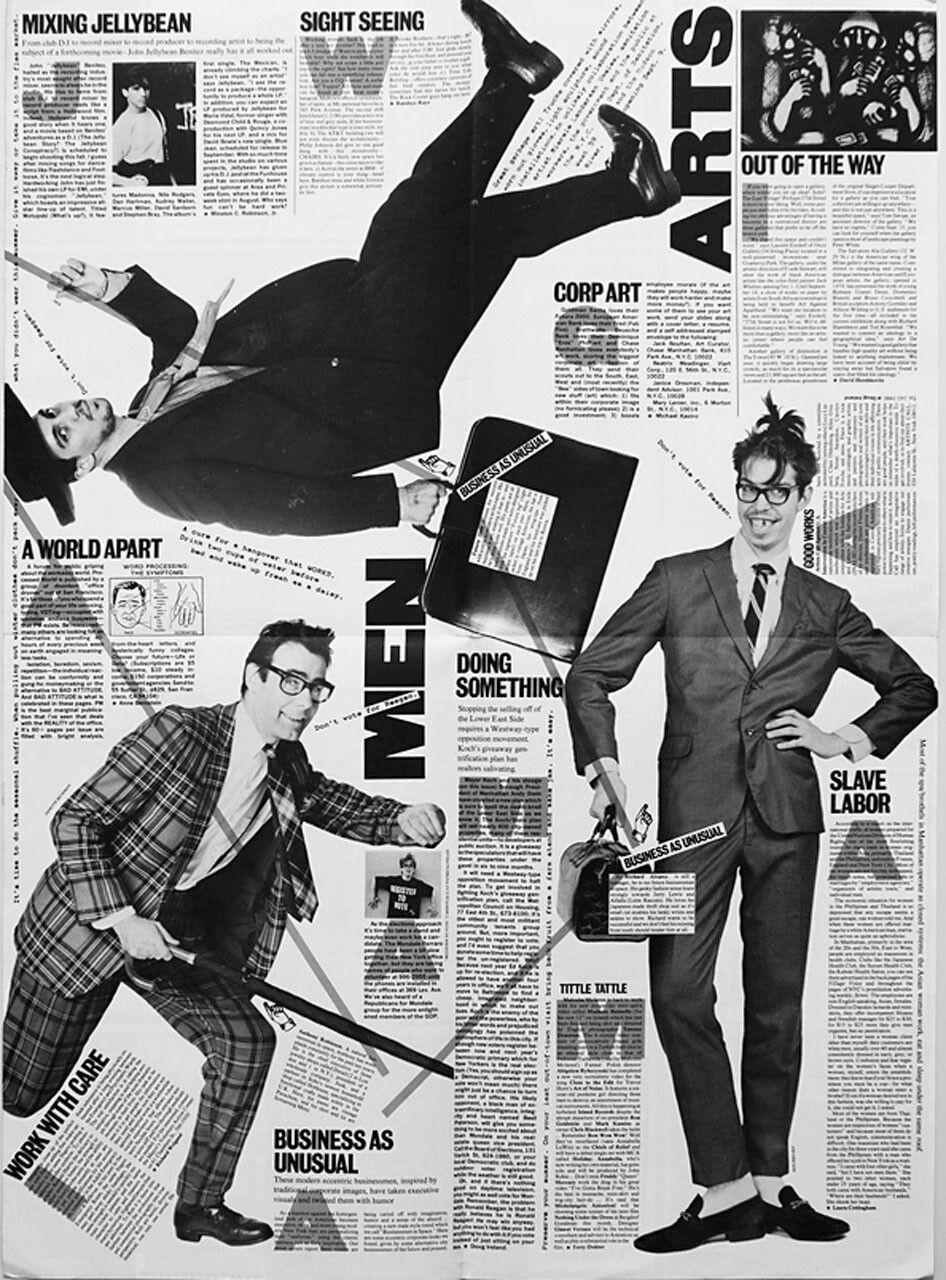

Inside design of an early Paper magazine.

Cover art from Paper magazine’s first issue in June 1984.

Cover art from Paper magazine’s August 1984 issue.

Cover art from Paper magazine’s September 1984 issue.

Inside design of an early Paper magazine.

Cover art from Paper magazine’s first issue in June 1984.

Cover art from Paper magazine’s August 1984 issue.

Cover art from Paper magazine’s September 1984 issue.

Inside design of an early Paper magazine.

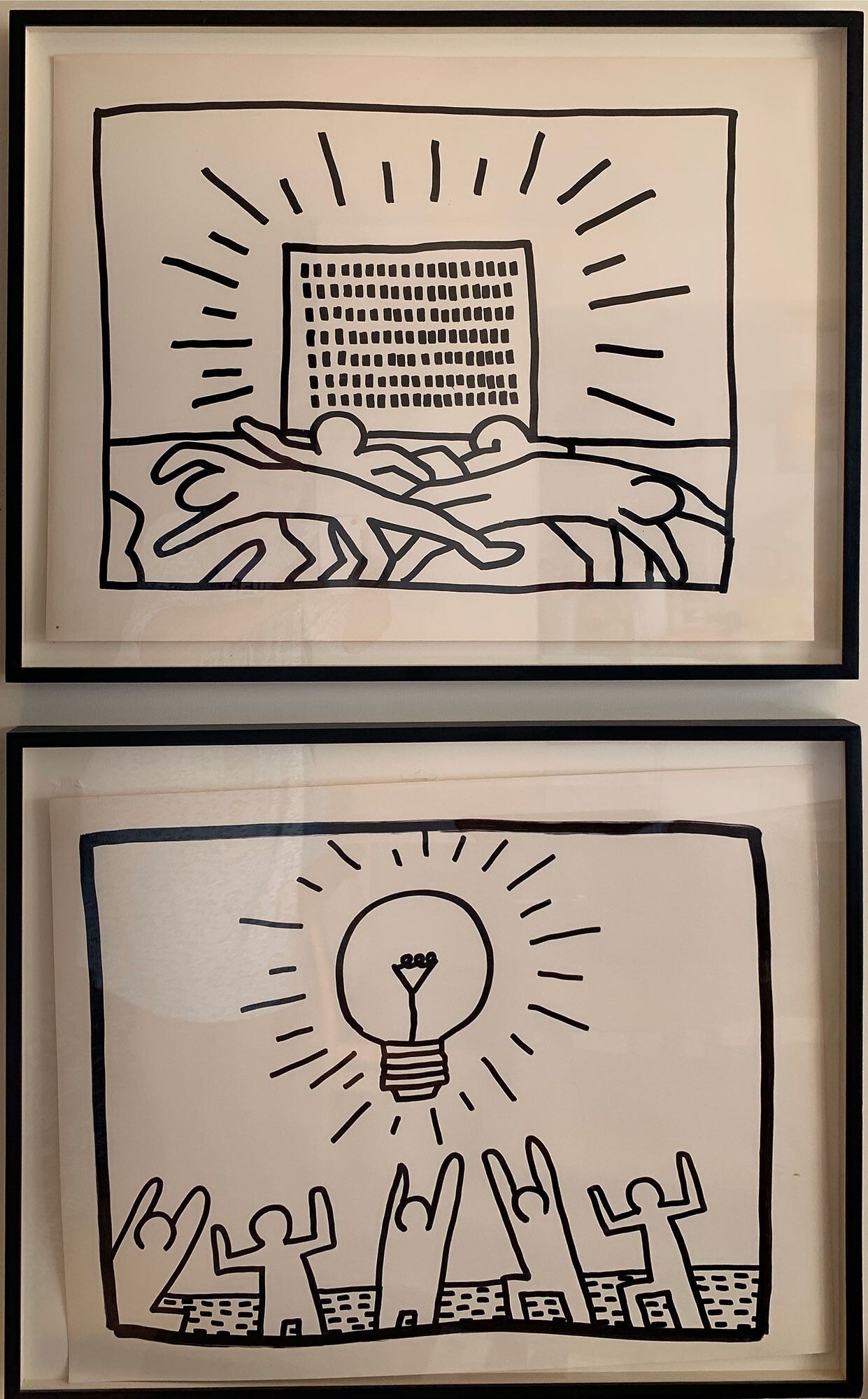

Artwork by Keith Harring in Hastreiter's New York City apartment.

KH: 1984. But really, I started doing it in 1979 at this other place. But how downtown New York—how we found out what to do was through people handing out cards and this thing called the SoHo News, which was like a newspaper [that] you’d get every week, and you’d find out every art show, every club night, every party to go to. And people would give out or send cards, like invites. That’s how you found out everything. And wheatpaste. So I also felt like I have a good sense of history. And I didn’t get that until after I started Paper—and then AIDS happened. I’m like, “Oh, my God,” AIDS was like huge. I’m twenty-four or something, and I have a list of thirty friends that have died and are dying. It was crazy, it was insane. Plus, then we started Paper in my house, because, still, there was no computers. Anyway, I just started saving, I didn’t buy art yet—I bought my first art in 1982, which was Keith Haring. I used to go to clubs, Mudd Club… I went to school to be an artist—I was supposed to be an artist—so all this was by mistake.

AZ: We’re going to get into all of that.

KH: This is all by mistake. So I ended up hating the art world, because the art world was too conservative for me. I felt like it was so conservative, the people in it were conservative, all they wanted was stuff that they could hang on the wall. I just saw all this stuff happening: people were making films and music and fashion and art and it was all collaborative, and Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren were doing these albums and they’d open stores, they’d have Sex Pistols and she’d make a punk line of clothes—that, to me, was more art than anything. The art world, they just wanted stuff they could put on a wall, and I was like, “Come on!” I was doing these paintings but I became much more interested in culture. So I left the art world. I had to get a job—I’m not even answering your question, what was your question?

“I ended up hating the art world, because the art world was too conservative for me.”

AZ: Well, we’re going to get into all of how you got started in a minute.

KH: You asked me a question, what was the original question?

AZ: The idea of—

KH: And now I’m going off it.

AZ: It’s okay. [Laughs] I could listen to you forever. The idea of objects sort of testifying to culture.

KH: Yeah, objects. So anyways, so I have experienced incredible culture. The beginning of the internet. AIDS. Watching the World Trade Center, two planes crash into—

AZ: From your apartment.

KH: From my living room, like what? I mean, hip-hop, the skate, sport, the cultural movements, the politics, Bill Clinton getting elected. Everyone thinking, “Oh, my God, he’s young, this is fabulous,” and then the Starr Report. And I remember collecting all these things. And I remember the day after the World Trade Centers—our offices were down there—crashed, my friend Espo, the artist—his studio’s next to our office on Franklin Street—he said, “Kim, you’ve got to come down here.” You couldn’t even move around the city because they wouldn’t let you below Canal Street, but I had a business there, so they would let me. He said, “The Koreans are selling these t-shirts. In one day, in twenty-four hours, they made all these T-shirts of Bin Laden bending over with the Empire State Building up his ass, with the firemen and the American flags.”

AZ: Yeah, it was quick.

KH: He’s like, “You’ve got to come here,” so I went and I bought fifty T-shirts. And I realize, I have to put these in my closet. And I bought every single newspaper from that day—

AZ:The Norman Schwarzkopf trading cards.

KH: Well, no, I just got like the New Yorker cover—everybody did these very major things that day, and I put them all into my closet. And I realized, these are markers, these are collector’s items. I love a collector’s item.

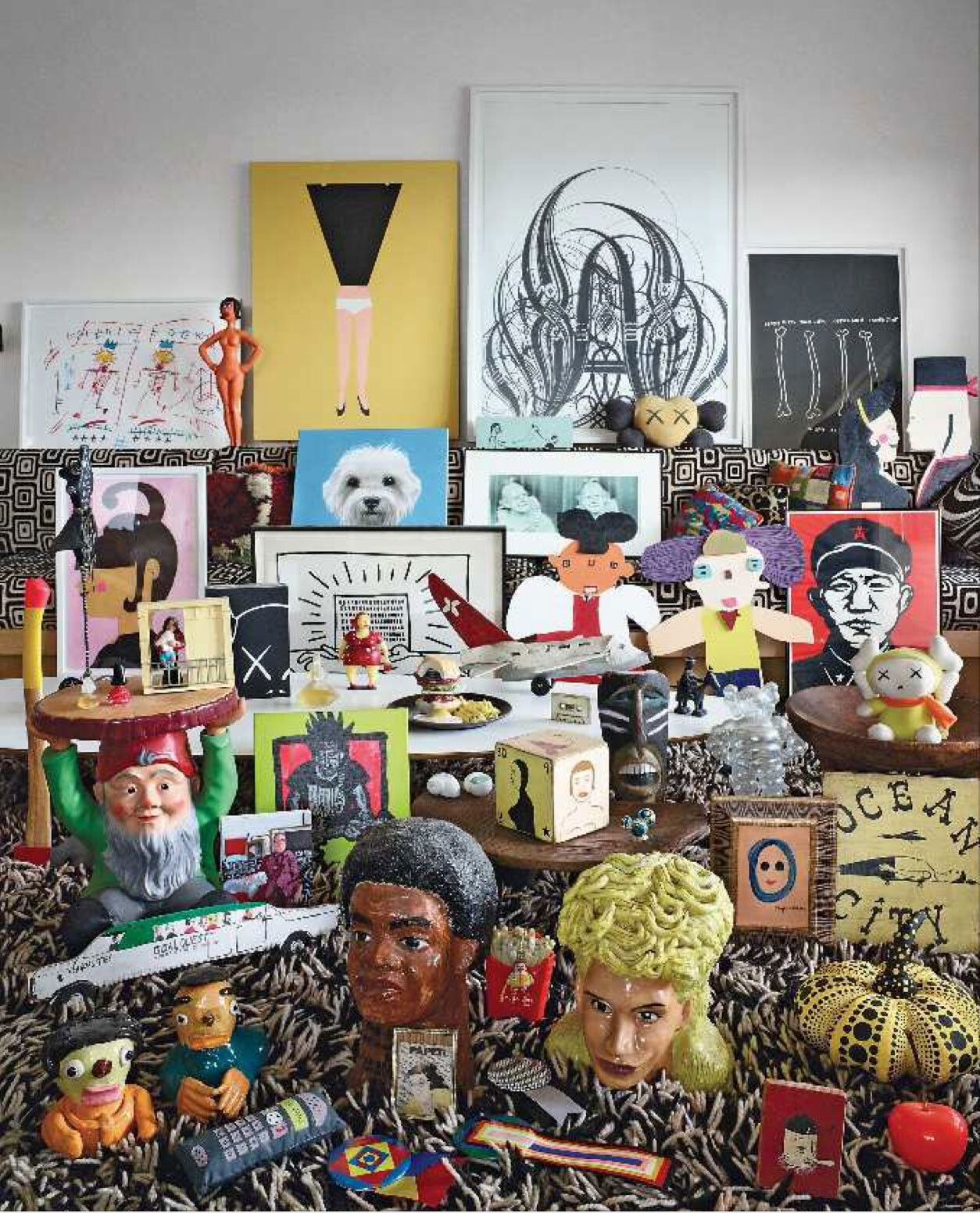

Select objects from Hastreiter’s Manhattan apartment.

AZ: So it’s all these cultural moments, it’s art, but I feel like going through your apartment—

KH: It’s my life…

AZ: Not just your life.

KH: It’s the history of New York. So what I’m doing now, [is] I’m archiving everything. Also, since I’m a really good editor, I’ve edited it down. Because [as] a collector, when you get to my age, it gets out of hand. So you really have to be ruthless at editing. When my mother died and all that stuff happened with Paper, I really had to be ruthless.

AZ: What were your criteria for keeping things?

KH: The best. The greatest. I had to get rid of stuff I really didn’t want to. I gave stuff away to people I thought would appreciate it. I’m archiving now because I’m doing a memoir through my stuff. And the stuff is going to be what is the memoir, and the stories about the stuff, it’s going to be the memoir of New York and my life.

AZ: What are some of your favorite objects from the collection?

A wood maquette of Hastreiter’s glasses.

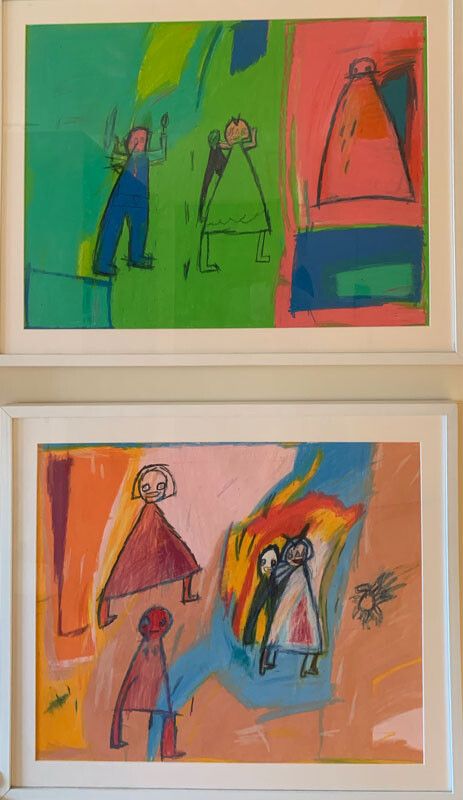

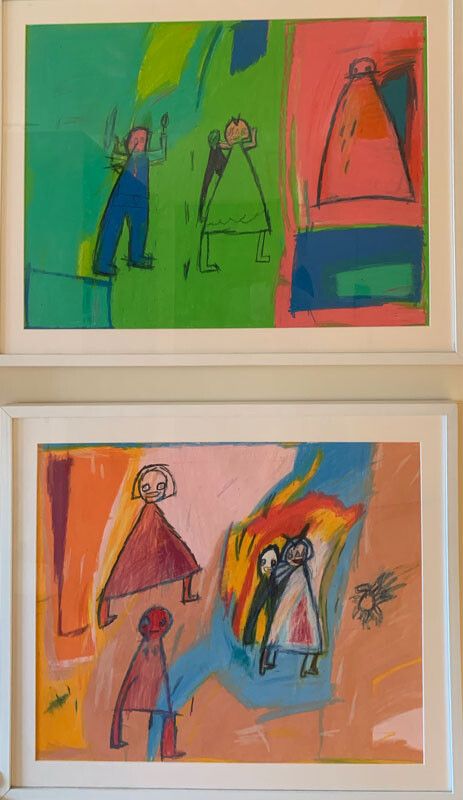

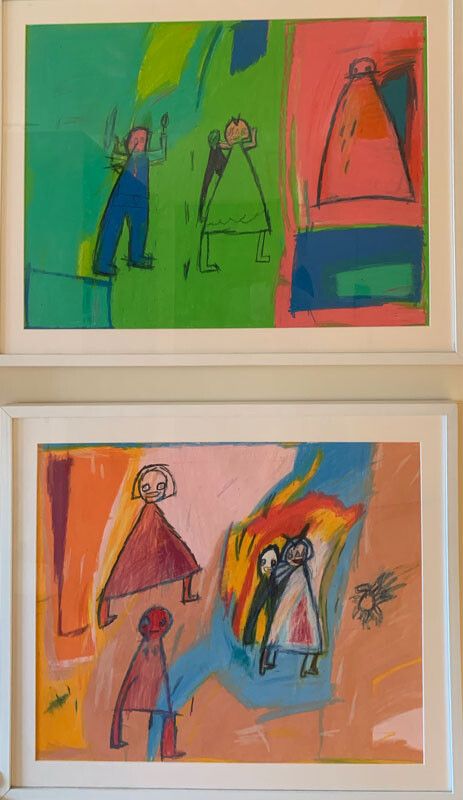

An illustration of Hastreiter by Phyllis Diller.

Hastreiter’s collection of colorful glasses.

A wood maquette of Hastreiter’s glasses.

An illustration of Hastreiter by Phyllis Diller.

Hastreiter’s collection of colorful glasses.

A wood maquette of Hastreiter’s glasses.

An illustration of Hastreiter by Phyllis Diller.

Hastreiter’s collection of colorful glasses.

Hastreiter's beloved Nakashima dining table.

KH: Oh, I can’t even say. I have… Every single thing I have has a story, from my dining room table, which is Nakashima because my parents knew George Nakashima, and he had stories, to my ottoman that was owned by a New York Times film critic where the strap broke on the bottom and he put his belt—

AZ: The Mies one.

KH: The Mies van der Rohe, yeah. To my art, the Keith Harings that I had that he gave me that I bought from his very first show in the basement of Club 57 for a hundred and fifty dollars, to the Jean-Michels that, when he got kicked out by Annina [Nosei] on the street, we all went and got stuff. I worked at this store when I first came to New York, and I was a salesgirl because I needed a job. It was this crazy store on Madison Avenue, so I would go up to Madison Avenue every day. The other day I hire an archivist who is archiving everything for me—and I have art; I have objects. To my neighbor Ingo Maurer, who is like my dearest friend who is a lighting designer, I got this loft on Lispenard Street. I mean, I went to Nova Scotia College of Art, where I met Vito Acconci and Joseph Beuys—

AZ: You have all that beautiful Italian glass… I mean, it just goes on and on.

KH: But I mean, the glass I got at Martha’s Vineyard in a thrift store. Because I didn’t have money, everything I got was either friends’ or had stories—I was a big thrift shopper. But the other day, I’m finding stuff from the eighties and the seventies; this girl brought out this box of letters that I was going through. I found this torn piece of paper, and it just said, in handwriting (it was, like, in pencil), “Mrs. Jacqueline Onassis, 1040 5th Avenue,” and then her phone number. She was my customer at Betsey Bunky Nini, where I used to sell clothes. She loved me. I was her favorite salesperson. She would call me, and I would call her if there was a certain thing that I thought she would like, and she lived around the corner, but I just found this piece of paper where she had written… I guess I had saved it.

AZ: Well, editing and curating [are] similar, it is storytelling.

KH: Yeah. I’m a really good editor, and I’m a really good curator. It’s the same thing.

A scene from the Art Parade in New York City.

AZ: Right, and it extends beyond objects, you’ve curated events, moments… One of them that stands out is the Art Parade, which I’d love to hear a bit about.

KH: So I started doing these experiential things. The very first one I did was in Bryant Park. The first time I ever did it was because the people from the CFDA—I think it was called the CFDA in those days—it was a long time ago, and the shows were in Bryant Park. They put up tents, and they were going to do men’s shows and women’s shows, and they had a tent that was going to be empty for three days. They thought, Maybe we can make some money, so they said, “Let’s do a young designer thing.” Meanwhile, everyone I knew, all the young designers, they would never go there. They hated the tents, they hated the CFDA. They were punk, downtown people.

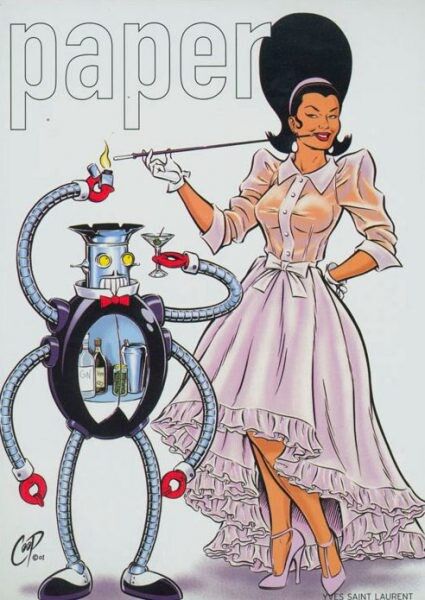

An early poster by Coop for a Paper party.

So they called me up, and they said, “Kim, would you curate shows if we gave you a tent for three days? Young designer shows.” So I was like, no one will do it. And then I thought about it and said, “Okay, I’ll do it, only on one condition.” They’d said, “We have sponsors.” I said, “The sponsors are not allowed to talk to the designers, there can be no signage of the sponsors, and you only talk to me, you can’t talk directly to the designers. And I’m in complete control.” So they were kind of like, “Ooh,” you know. I said, “That’s the only way I’ll do it.” But they were kind of desperate and they had this sponsorship, so I said, “I will talk to the sponsors, and I will try and make something happen for them that will give them something, but they’re not allowed to talk to the artists.”

So they gave me this tent, they said, “Okay,” and I curated this crazy thing for three days, I made three different things. All the sponsors were happy. I looked at what they did, I came up with ideas, I would go to designers saying, “Gore-Tex makes this really good camouflage, can you do something with it?” And they were like, “Oh, yeah.” So Gore-Tex is happy, you know what I mean, and they put the name Gore-Tex in the program because they got free fabric. So anyway, I came up with ideas like that. So that was the first thing, it was a huge success. Geoffrey Beene even did it. I had bands playing, AsFour [now threeASFOUR] had their first show with me, Rick Owens had his first show with me.

AZ: Wow.

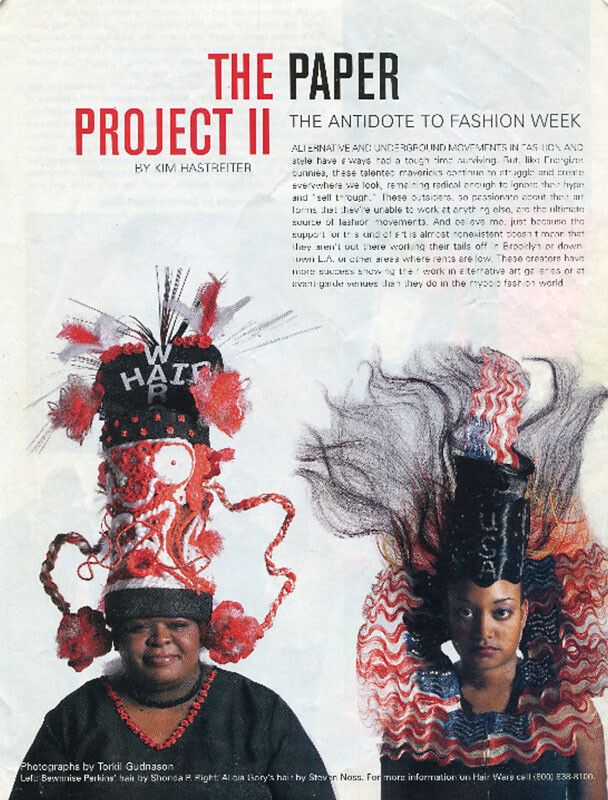

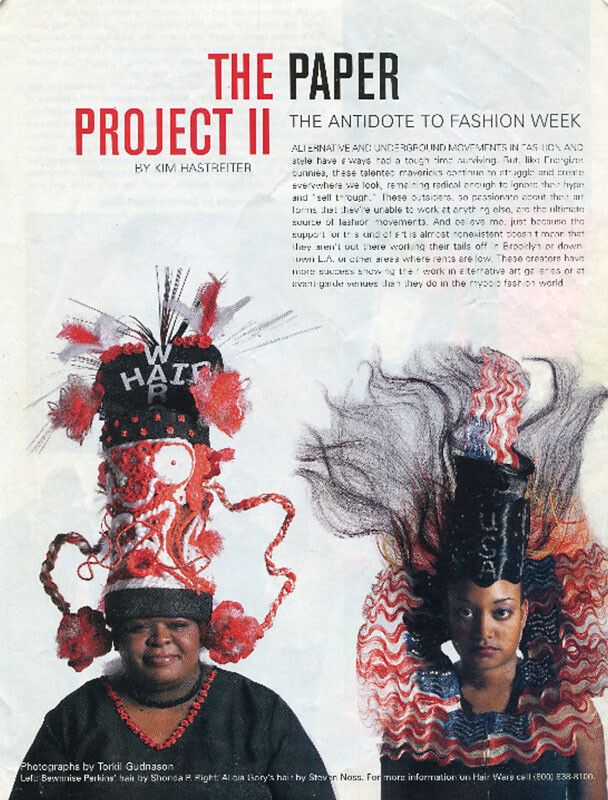

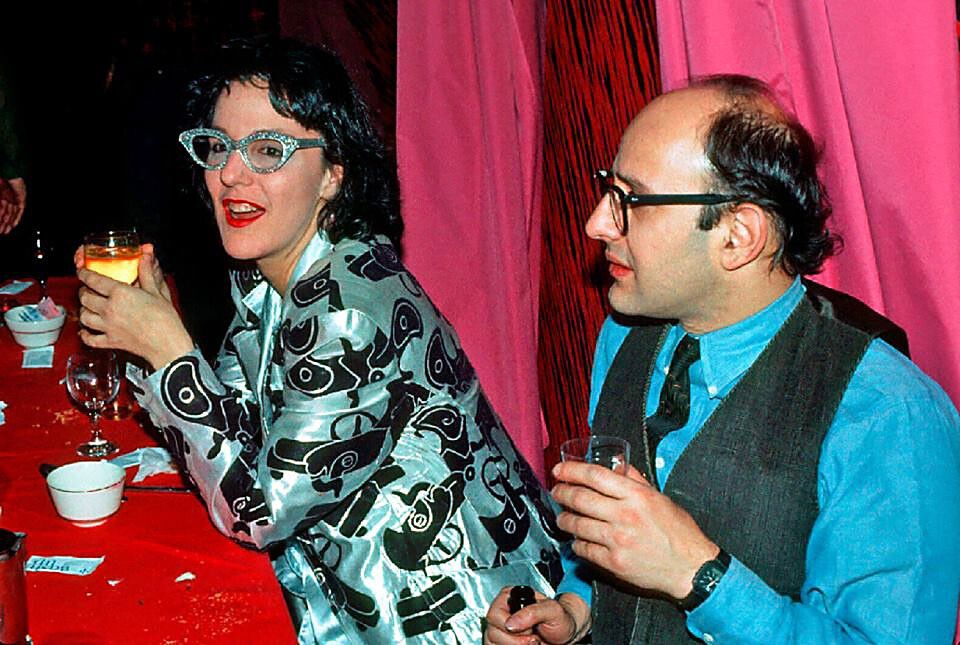

KH: A lot of people had their first shows then—it was outrageous. And then, I always hated Fashion Week, so I went to Jeffrey Deitch, and I said, “I want to do what I did at the CFDA the next year, but I want it to be an antidote to Fashion Week, so I want it to be, like, art and fashion. Art that is informed by fashion and fashion that is informed by art.” And Jeffrey was like, “Do it, I love it.”

Andrew Andrew in a deejay booth at one of the 24-hour department stores Hastreiter curated in LA. They deejayed for 48 straight hours, and the Post-its were requests from shoppers.

So I went into his gallery on Grand Street, and he took over the whole building. And [that] was September 9, 2001. Two days before [9/11]. It was crazy. We had this huge—AsFour did a concert on the roof with theremins, I had Walrus, who’s, like, famous now, Waris [Ahluwalia] had a turban wrapping—Waris used to sell turbans in those days. I had [the DJ duo] AndrewAndrew—people came in, they would take their clothes off, they gave them bathrobes, and AndrewAndrew would sew shit onto their clothes and give it back and put a big label on. I had this guy called Nelson [Loskamp], the Electric Chaircutter [who] would blindfold you and put you in this chair, and he had these scissors that were connected to a musical synthesizer, and you just had to go with it. I don’t know if his eyes were blindfolded, but yours were, and you had to just get a haircut in this chair but it was like a performance. And then I had Coop. Coop did this couture—I got couture pictures from Paris, and he put his big, giant ladies, like those crazy women, in couture. We blew them up, and we had a huge show. And then I had fashion wrestling, I had people in gowns wrestling.

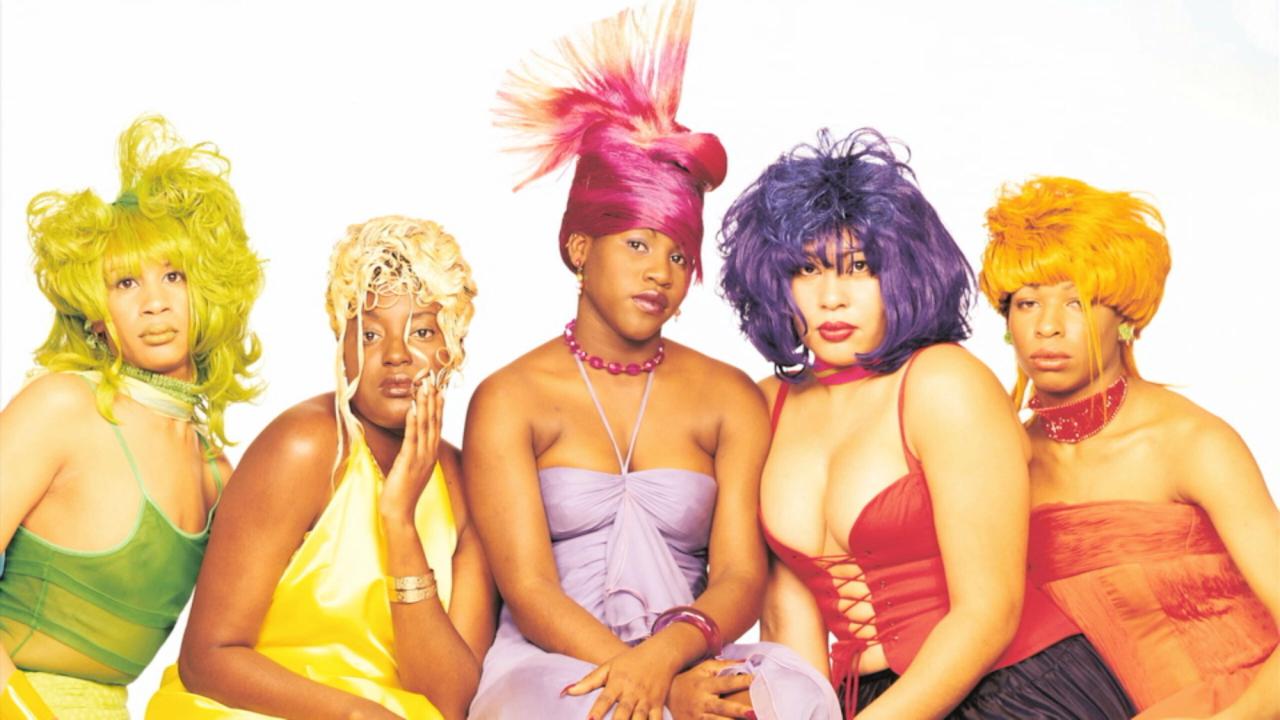

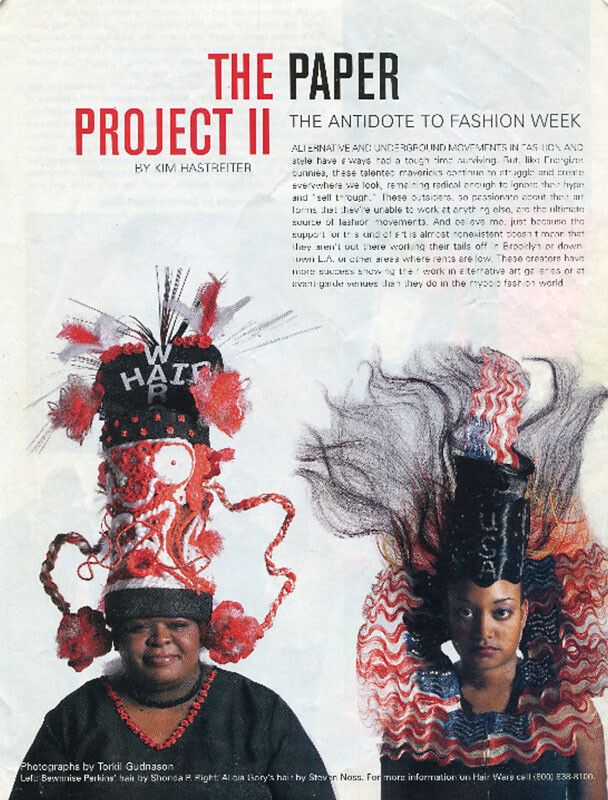

So then, Jeffrey was like, “Oh, my God, this is the best thing,” and it went out on the streets, and there were concerts, but it was Fashion Week. So then the next year, later, Jeffrey said, “I want you to do it again, but I want you to do it in the big galleries.” So I got the hair designers from Detroit who do those topiaries to come, Hair Wars, I got Alabama to bring all these quilters there. I had this one fashion designer, I forget his name, and at the end, he gave out goodie bags, and each bag had a live, giant cockroach in it. Jeffrey Deitch, that was the only time I ever saw him freak out. He freaked out.

Hair Wars. (Courtesy Council of Fashion Designers of America)

The ice cream truck at Art Parade in New York City.

AZ: He doesn’t like cockroaches.

KH: He freaked out. I’ve never seen Jeffrey Deitch—it was the only time. It was crazy. I had spin artists doing like—it was so fun. Jeffrey was so into it, and then the next year after that, he said, “Let’s start a parade.”

So it was like the third year that we started this parade. Because I was like, “We have to do it again, but we have to keep making it different.” So it was Jeffrey who said, “I want to do a parade, will you do it with me?” So I was like, “Yeah!” We just got all these crazy people, and we marched through SoHo on Fashion Week. It was like the antidote to Fashion Week. It was called a “Paper Project,” and then we called it the “Art Parade.” So we did the Art Parade, I think I got a vintage police car—I rode in a vintage police car, Jeffrey had an ice cream truck, drag queens, people made costumes, I had designers marching—it was so good.

AZ: People love—I saw it, of course, I was there.

KH: We did that for a couple of years.

AZ: Yeah, well, I remember the Deitch show in 2001, it was such a big deal.

“The Antidote to Fashion Week,”an article written by Hastreiter about the Paper Project event.

Scenes from an early Paper art party and shopping extravaganza.

Scenes from an early Paper art party and shopping extravaganza.

Paper storefront in Los Angeles.

Lindsay Lohan and Jeremy Scott at an early Paper event.

Jeremy Scott lounging at a 24-hour department store party in L.A.

A scene from the 2007 Paper Project in Los Angeles.

Bill Cunningham capturing a moment at one of Paper's early events, The Super Duper Market, in New York City.

“The Antidote to Fashion Week,”an article written by Hastreiter about the Paper Project event.

Scenes from an early Paper art party and shopping extravaganza.

Scenes from an early Paper art party and shopping extravaganza.

Paper storefront in Los Angeles.

Lindsay Lohan and Jeremy Scott at an early Paper event.

Jeremy Scott lounging at a 24-hour department store party in L.A.

A scene from the 2007 Paper Project in Los Angeles.

Bill Cunningham capturing a moment at one of Paper's early events, The Super Duper Market, in New York City.

“The Antidote to Fashion Week,”an article written by Hastreiter about the Paper Project event.

Scenes from an early Paper art party and shopping extravaganza.

Scenes from an early Paper art party and shopping extravaganza.

Paper storefront in Los Angeles.

Lindsay Lohan and Jeremy Scott at an early Paper event.

Jeremy Scott lounging at a 24-hour department store party in L.A.

A scene from the 2007 Paper Project in Los Angeles.

Bill Cunningham capturing a moment at one of Paper's early events, The Super Duper Market, in New York City.

Hastreiter and John Waters.

KH: And then, that kind of morphed into something I did in Miami with Jeffrey: the ninety-nine cents store. Do you know about that? Yeah, because that was amazing, I love shopping, I love stores.

So that was the first time I did a store, it was when people were starting to do collaborations, like in 2005. So I said, “I want to do an arts store,” where [there’s] no art, just shit that’s done by artists, so I had like John Waters china, I had Cindy Sherman’s soup tureens, I had Kiki Smith rugs, Keith Haring sneakers that Jeremy Scott did. Supreme did Damien Hirst skateboards, but it was millions of things. I did it like a ninety-nine cents store and it was ninety-nine cents to 9,999,000 dollars. It was so good. It was before the Design District had anything in Miami, and it was just these empty warehouses. We did it in an empty storefront and Jeffrey paid for it—Jeffrey was my angel, I love Jeffrey Deitch.

Hastreiter and Jeffrey Deitch.

AZ: He was the patron to your conducting.

KH: Yes. He loved my ideas, and he would just say, “Let’s just do it,” and he would just pay for it. I didn’t have to get sponsors. [Laughs]

AZ: People say New York changed. People are always saying that. They probably said that in the fifties.

KH: Everything changes all the time.

AZ: Everything changes. But you seem to embrace that change.

KH: I hate when people—my biggest pet peeve, you might’ve read, I always say, is when people say, “It used to be better…” I hate you if you say that. That’s like the stupidest. “Oh, New York used to be so great, this used to be so great, it used to be so much better.” No, you’re wrong. It’s always greatest, the best, now. You just have to find where it is. It’s never the same place, stupid. It’s never in the same place. You have to look for where it is.

AZ: Absolutely.

KH: And, you know, you can make [it] great. So just because New York changed—yes, it changed—doesn’t mean that there’s not great people or not great things—there are.

AZ: When I think about you roaming the city, I imagine you see ghosts everywhere, and you sort of mark time through all of this, because the physicality hasn’t changed.

KH: I do. The other day, I just drove down Broadway, and I saw two of the old Paper offices, one of which has turned into this high-rise building—we had the funkiest offices, always. One was on Spring and Broadway, that was our first office, and then our second office was on Franklin and Broadway, and that one turned into a condo of some sort. I actually photographed it from my Uber because I was like—I have those photos on my phone I can show you because that was just kind of a memory, so much happened in those spaces, in those Paper spaces.

“Fashion is, like, so old news. The kids don’t like fashion—it’s about culture. It’s not about luxury, it’s about culture. If you’re not culturally relevant, you can’t just make fashion, unless it’s like art.”

AZ: Do you think that the shift in the idea of luxury has been constantly happening?

KH: Yes!

AZ: What do you think luxury is today?

KH: Fashion is, like, so old news. The kids don’t like fashion—it’s about culture. It’s not about luxury, it’s about culture. If you’re not culturally relevant, you can’t just make fashion, unless it’s like art. I just think that luxury… what’s luxury? I mean, everything’s so bad now. Luxury is like escape. I always would joke that it was so hilarious that luxury is basically going back to everything before we fucked it all up. That’s what luxury is.

AZ: Primordial.

KH:Clean water, pristine places. That’s luxury, going back to where, if you can find any place that’s not yet fucked up. That’s luxury to me.

“Clean water, pristine places. That’s luxury, going back to where, if you can find any place that’s not yet fucked up. That’s luxury to me.”

AZ: Amazing. So now I want to talk about the second descriptor in your email, which is “Original Gangster.” And before you made a magazine, before you lifted up all of these creative people who really shape culture, when you think about all of the people you touch, you were a kid in West Orange, New Jersey. Were you interested in culture as a kid?

KH: My mother was. I had an amazing mother. So my mother was, really, the reason why I am. My mother was a culture vulture. In her day, she was a wife, and she had two kids and she was living in a suburb, because my father had a jewelry store in Newark, New Jersey, that his father had started. She loved art, she was a voracious reader, she was a voracious intellectual, political, creative—she had really good taste.

Hastreiter as a young child.

Hastreiter's mother on a porch in Martha's Vineyard.

Hastreiter's mother showing off her “Impeach Nixon” T-shirt.

Hastreiter as a young child.

Hastreiter's mother on a porch in Martha's Vineyard.

Hastreiter's mother showing off her “Impeach Nixon” T-shirt.

Hastreiter as a young child.

Hastreiter's mother on a porch in Martha's Vineyard.

Hastreiter's mother showing off her “Impeach Nixon” T-shirt.

I grew up with Dansk and Nakashima. She went and drove to New Hope to meet George Nakashima to get her dining room table, you know. She told me all these stories, that George Nakashima said how you shouldn’t worry about the table getting scratched, that his favorite thing was when his kids would do their homework on top of the table and their pencils would make marks, because he said [those are] memories. So it always made me treat my Nakashima table like that; you shouldn’t be precious. Because my mother would be like, “What should I do if it gets this on…” And as I got older—so I grew up with that kind of a mother—but as I got older, when I was in high school, she was kind of like, you can work for your father during the summer. Work—either get a job or work for your father—or I would have some other option. She would give me options. She was strict, you know. She said, “You could go to this Festival of the Arts in New Hampshire that I read about,” which was [at] Dartmouth College—they had a program. So she would find these weird things.

So of course I would always pick the weird things, because I didn’t want to go work in a jewelry store all summer, it was more fun. So I would go to do these weird things, and my last year in high school—this is a good example—because at the end, I would just say, “What am I doing this summer, what do you have up your sleeve?” and she said, “You’re going to go to Arizona to work for this architect, Paolo Soleri, who’s building the city of the future in the middle of the desert. You’re going to sleep in the desert, but you’re going to get college credit for it.” So I applied to college, and I got into Washington University of St. Louis. I had no idea what I was going to do. I always liked art, and my mother was a huge influence on me because she liked art. My mother kind of always wanted to be a shrink, for some reason. That wasn’t my goal, but she always wanted to be a psychiatrist or psychologist, but she could never do it because she was a housewife—she put everything into us. But she sent me to this—do you know who Paolo Soleri—

AZ: Of course.

Hastreiter as a young adult.

KH: So I built the first building at Arcosanti in the summer of 1969. I was so young, I didn’t know anything. I just would do what my mother—

AZ: One of the most famous summers of the twentieth century.

KH: 1969. So that was like also—

AZ: Your Summer of Love was building the city of the future.

KH: Right. So I went to college in the fall of 1969. I immediately started protesting—it was like, I went right into it. Well, first I went to Arcosanti where I did construction in the summer, in the desert. It was like 120 degrees, they grew their own food—it was a kind of vegan situation. This is 19… This is early, it was hippies. There was a girl who drove the forklift. Forklift? Not a forklift. The tall thing?

AZ: Backhoe?

KH: It’s the tallest thing that you put things in buildings…

AZ: A crane.

KH: Crane, yeah. A girl crane-driver. It was very radical. Hippie, total hippie.

AZ: This was before the slow food movement. This was really where the ideas were starting.

KH: Yeah, and they had a garden, and it was on a mesa. We would sleep—there was like a little camp and Paolo Soleri had made these—they weren’t tents, they were made out of concrete cubes but they were open, they had these big circles. So it wasn’t like a room—you were sleeping outside, but if it rained, you had something over your head. And we slept in sleeping bags. And you slept in these cubes, but the cubes had big holes in them—you just walk through the hole to get in. Then there was a main room where you would eat, and they had a garden, and all the staff lived down there. And every morning, you would go to the top of the mesa—I had a Jeep, I had bought a Jeep that summer to drive there, I decided I wanted to drive there. My Jeep was fucked up, and it was really hard, it kept dying. But it was so hot that you would get up at like five. You would get up to the top to start work at six, come back down at eleven, and then you’d go back up at like 2:30. So you would take the middle of the day off because it was too hot to work. And you’d have to eat salt pills, and they had Kool-Aid…

AZ: Did you have any idea at the time that you were taking part in something globally happening that’s radical? Superstudio, Archigram, all these things were—

KH: No. I had no idea. And Paolo, who lived in Phoenix, he would pay for things by selling these bells. So first he would go for the indoctrination at his—he had this thing called Arcosanti Foundation where they would pour and make these beautiful metal bells, which they still make. I mean, I’m like, I need to buy some. Mental note. Because you can still buy them, they’re fabulous. And that paid for everything, and then he had all [these] students working for free, and they would get college credit. And I met all these weird people, I just met interesting people. I was so young. That summer, I saw rattlesnakes, scorpions, tarantulas—it was crazy. I was sleeping outside in the desert for a whole summer. And we built these two buildings. And then, really, it didn’t come back to me, the impact, until when I was at Paper, and I looked back. It takes a while. And the young generation discovers it. To me, I never talked about it, really, but at a certain point, young people started noticing it. You know, Miu Miu showing an ad campaign, or whatever. I remember I was working for Levi’s and we were doing something on this train. Remember the crazy train?

AZ: Doug Aitken.

KH: Doug Aitken, yeah, the train. So we were in this crazy place in Arizona that had the train stop. So I took Levi’s there, I did a little side trip there. I went, and we had this lunch there, it was fun. But I went back, and I was like, “Oh, my God, look what happened to this place.”

AZ: It’s an amazing moment in time, for you in your own journey, and also culturally.

KH: So then I go to St. Louis and it’s all exploding. I was in a dorm, and I was like, “No, this isn’t for me.” Then I moved off campus and I became a hippie. I started taking acid. Acid was a big part of my childhood; that was an important part of my—

AZ: You had started in New Jersey or you dropped for the first time in St. Louis?

KH: No, St. Louis. New Jersey was just pot. But the acid was an important part of my formation. I loved acid.

AZ: Yeah, for many.

KH: And mushrooms.

Hastreiter in her younger years.

AZ: Are you still interested in illicit drugs?

KH: No, but you know, I just read John Waters’s amazing book—have you read it?

AZ: Not yet, but I just listened to an interview on it.

KH: It’s so good! He wrote the best book. It’s like a memoir. It’s called Mr. Know-It-All. It’s such a good book. And John is a friend who I love. But this book is kind of a memoir, looking back, and at the end of his book, and what he told me is that when he went to his publisher, that was really what he sold the publisher on. He wanted to take acid one more time. And you know, he’s like seventy-three or something. And he was scared to take acid—I’m scared to take acid now, I would never take acid now, I’m too old. Your body, it’s hard on your body to take acid.

AZ: So you were taking lots of acid, early seventies.

KH: And then there were protests, and then we would take over the ROTC building. I just fell into this radical crowd. All these people like the FBI came, and people got busted, people were getting pot sent to them in the mail, marijuana, people went to jail, and the FBI was on campus and arrested some people for the radical stuff, like the protesting. And then my friend got pregnant, and we had to go to New York for an abortion because they didn’t have abortions. I was just like… went there. I became like that.

AZ: And then you went to Nova Scotia.

KH: Yeah, so then I did that for a year and I was in normal college and I was like, “I can’t relate to this, I want to go to art school.” So I told my mom and dad, “I want to transfer to art school. But before I transfer to art school, I want to take six months off and go to, like, Morocco. I want to go somewhere.” At that point, all my friends were getting disowned by their parents because parents were conservative—old people were people you didn’t want to be friends with—they were really conservative. The kids love old people. I hated old people, except for my parents. When I told my parents, I was ready to have them say no, and I was going to go anyway if they said no. I was ready to have the fight and I was like, “Well, fuck you, I’m going.” And I told my parents what I wanted to do. I wanted to go to art school, I wanted to take a year off and travel—I would work for six months, save money, and then go. And my mother said to me, “You have my blessing. I only wish that when I was young, I could have done that.” And I was kind of like … she completely diffused any of that—

AZ: Amazing.

KH: I was like, “I have these parents…” They were like, “What can we do to help?” That was the theme through my whole life. Whenever I said “Crazy idea, I want to quit my job, I want to start a mag—” “What can we do to help?” It was never like, “You shouldn’t do that.” No judgement, no “Don’t do this.”

AZ: Full support.

KH: Completely, like blind support.

AZ: Which has been a theme in your life that I want to get to, on both sides, and that apparently is where you learned it. You go to Nova Scotia and then you take this drive with your friend to New York, this cross-country trip.

KH: Well, I went to CalArts after Nova Scotia. So I went to Nova Scotia—I left St. Louis, I went to art school—

AZ: Yeah, how could we skip [John] Baldessari, actually?

KH: Yeah, I went to Europe, to Morocco, by myself, hitchhiking through Europe. I was by myself, hitchhiking, it was crazy. Then I went back to art school in St. Louis, I did it for like a semester or a year, I don’t remember, and I was kind of like, “I don’t want to do normal painting.” I started doing my own work, but [the environment] was too conservative.

There was this place called Nova Scotia College of Art that was really crazy, avant-garde. Artforum would write about it all the time—Jonas Mekas [and] Joseph Beuys taught there—all the conceptual art was happening. It was like the place. And I applied, and I got accepted. There were very few people that got accepted, but I was doing my own work; they liked my work. So I was like, “Okay, I’m going to Nova Scotia.” My parents were just kind of like, “Fabulous.” They were supportive.

By this time, I bought a pick-up truck. I had my friend paint a dragon on the side—it was called “Dragon Wagon.” And I just drove to Nova Scotia, I lived there for a year in Halifax, where I met, like, everybody. All these artists—literally, Joseph Beuys, Vito Acconci, they all were there, all the conceptual artists. Germano Celant taught there, Daniel Buren taught there—it was all artists that taught there. And it wasn’t really classes, it was just about making art. It was very avant-garde. It was connected to CalArts, so a lot of the people from Nova Scotia would go to CalArts, et cetera: you went to CalArts, you went to Nova Scotia. They were connected.

So then, when I graduated, that was the year Nixon got impeached. So meanwhile, I had gone away during all the protests, but when I went to Nova Scotia, it was in Canada—they weren’t even in the war, they had all this money because they didn’t even have an army. They just gave money to art, it was amazing. I watched the whole Nixon thing—Nixon got impeached, that was amazing. Then I decide to go to graduate school. I got a scholarship to go to L.A. I just drove myself, I did it myself, I drove my Dragon Wagon cross-country to L.A. I didn’t know anybody.

The first person I met was David Salle, the artist, because he was the boyfriend of this girl I knew from St. Louis who was at CalArts. And I got this apartment—John Baldessari became my mentor. He lived in Santa Monica, and I got this apartment across the street from him. He got me a job—I was a maid. I would clean people’s artist studios and stuff. And then I got this other job delivering sandwiches in Beverly Hills, and that’s where I met Joey Arias, who was working at a frame store. You know who Joey Arias is?

AZ: Yeah, that’s who you drove—

KH: Yeah, so Joey was really into thrifting… I would go to CalArts every day from Santa Monica. It was like an hour drive. It was going into the desert, you know. I had a studio there. My studio was next to Sue Williams—she’s such a great artist, I love her. Who else was there? It was just amazing. Laurie Anderson… CalArts was wild. But I didn’t live there.

AZ: And you were hanging out with John Baldessari, one of the most absurdist—

KH: John was a great teacher and a wonderful mentor. He loved my work, and he was amazing. I ended up being in a lot of his work. He was doing a lot of videos; he would use all his students to be in his videos. I have one of the videos that I was in, that was amazing. We used to have to recite these lines from Sunset Boulevard. They were very dramatic, these videos.

AZ: Paint yourself out of a room.

KH: It was very different. Nova Scotia was very serious, conceptual, and CalArts was more humor. And then I met Chris Langdon, who was my boyfriend, who was this amazing artist from CalArts who then later became a woman. He was this amazing filmmaker. I met amazing people at CalArts.

AZ: Why did you leave California?

KH: Because I graduated from CalArts. CalArts was really no classes, it was all making art and figuring out how to get in the art world. So John hooked me up with Paula Cooper, and the Whitney Biennial—they had them come look at my work. He really believed in me—he helped me, he’s really generous. He’s an amazing mentor. We all moved to New York, my whole class. A lot of whom became—Ross Bleckner was there, I think a year before me. Sue Williams, of course.

AZ: He paints upstairs, in this building.

KH: Who?

AZ: Ross Bleckner.

KH: He does? I’ve known Ross forever; I love Ross. He has a studio here, really? I’ve known him forever. But then there was this whole group of artists that went to Metro Pictures, like I don’t know if you know their names, but Troy Brauntuch, Jim Welling, Matt Mulligan… Those were all people I went to school with.

AZ: Yeah, that’s a huge generation you were right in the middle of.

KH: So we all move to New York together to go in galleries. And all the boys got galleries, and none of the girls got galleries. And I was fucking pissed off, because some of the boys were not as good as artists as I was. And the girls—no one got galleries. Meanwhile, I had to have this job, I got this job selling clothes, and meanwhile Joey and I got an apartment together. Joey ended up staying here, and I became involved in nightlife. I was just like, “Fuck you, your art world is so stupid.” I thought whoever made the best art got in the gallery. No. It was like, whoever could hustle and smoke the cigars, and… sorry, it was just…

AZ: So you were hanging out at the Mudd Club instead.

KH: Yeah, and then I kind of saw hip-hop and the artists, I was hanging at the Mudd Club and then I really got in deep at Club 57. I met Keith [Haring] and Kenny [Scharf]. Joey [Arias] was involved, they put on plays, and it was amazing. There was so much, so much stuff going on. Movies and making performances…

Hastreiter and Bill Cunningham (with Mickey Boardman, at left) in New York City.

AZ: And one day, you meet Bill Cunningham.

KH: Well, I met Bill Cunningham because I had this job selling clothes, because I had to pay my rent. I kept thinking, How am I going to be an artist if I have to have a full-time job to pay my rent, and then I go to the clubs—how am I going to do this? So I just got kind of stuck selling clothes and I would do windows, and then I met Ted Muehling, who’s one of my oldest friends. I just made friends outside this strict art world. I saw all my friends—they all went to Mary Boone, it was like a boy’s club. But they weren’t doing anything else. They were too serious, making the art. That’s why I love Jeffrey [Deitch], because art is more than just that [for him]. They just think art is that only thing—museums, no, that’s not what art is. So that’s one of the subjects of my book, like “art is everywhere.” And they were all looking at me like, “What is she doing?” And I was like, “You don’t know what’s going on here, you’re losing out. Because this is better than what you’re—art.”

AZ: Which was cross-pollinating with all sorts of people.

KH: And Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, the two, was a big inspiration. They were doing these amazing collaborations where he would come up with these crazy bands, and she would come up with these crazy looks. Do you know the history? Bow Wow Wow and the Sex Pistols, and they would make these clothes. And I would go up to Betsey Bunky Nini, the store, every day—

AZ: Which was Betsey Johnson’s—

KH: Yeah, she was one of the three partners. Bunky was this other lady, Betsey, and then this third girl, Nini, who I never met. She dropped out or something. I would sell clothes to Jackie Kennedy, and it was a weird store, but really expensive, that always had weird designers. So people who liked avant-garde—but it was still on Madison Avenue and 64th Street, and it was very expensive. They always hired artists to sell, so it was interesting. Like Norma Kamali was across the street, I remember, in those days.

So I got into this fashion thing, I was like, “Oh, my God, this is so wild.” They had Kansai Yamamoto, they had some of the early Japanese designers… Zandra Rhodes. This woman Bunky bought really crazy things. And famous people came in all the time, like Barbra Streisand. They had one big dressing room, so everyone would get naked together. But, like, Barbra Streisand in the communal dressing room, and then like…

AZ: At the height of her career.

KH: …Linda Ronstadt. I mean, everyone would come in. But also, one of the owners was a Rockefeller, so it was this weird mix. And Jackie Kennedy used to shop there—they loved it. It was famous, kind of. I did the windows, I did these crazy windows that became kind of famous. I loved selling clothes, but it was like—my mother, that was the only time where my mother was like, “Kim,” like after a year, she started on me. My mother was like, “Kim, okay, get real. You’re not going to be selling clothes…”

AZ: But you were also developing a sense of identity and your own fashion.

KH: I know, but I was getting a little comfortable doing that. And my mother was like—she was good, she kicked my ass. She was like, “What are you going to do?” And I remember I met Beth Rudin there. You know Beth Rudin? She was a customer, and she invited me to her wedding. Nora Ephron was a really good friend, she was my customer—she loved me, I would go to her house. Nora Ephron. And now I know her son Jacob Bernstein. He loves me because I knew his mother so well. But I had really good customers.

AZ: Yeah, you met all of these amazing people. But then why did Bill Cunningham stop you?

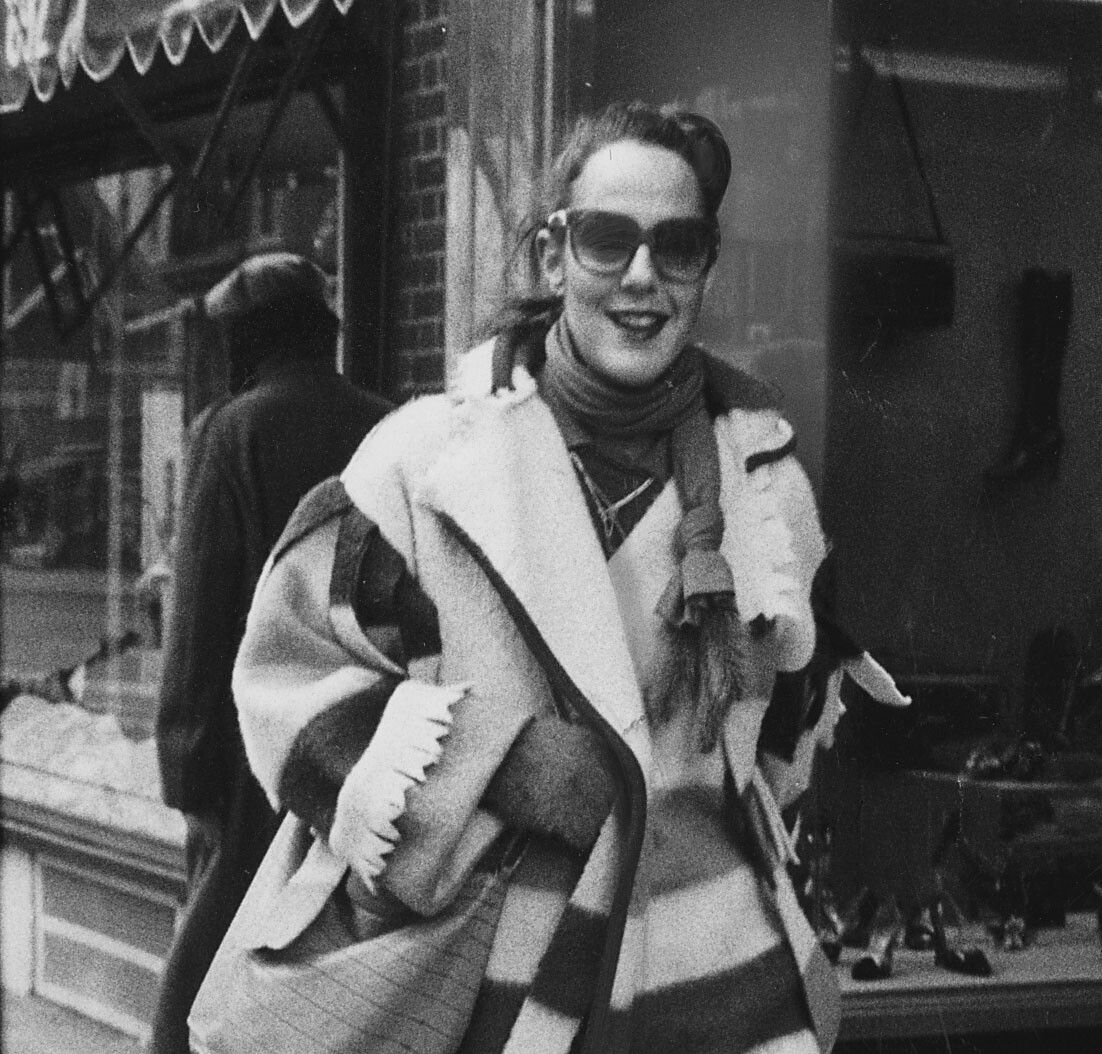

Hastreiter, captured by photographer and friend Bill Cunningham.

KH: So Bill would just photograph me because I would dress… I would stay up all night—I would take speed to stay up. I was in the clubs all night, at the Mudd Club or—so I would come up wearing punk things like hot pink boots and bondage pants. I would dress crazy, and I had this crazy coat, and Bill would go crazy. Every time he would wait for me, I would come out of the subway, he would photograph me, always. He just kept photographing me. And then I saw him downtown at the flea market, so we kind of became friends, because I was living on West Broadway in a tenement in those days. And then my grandmother died while I was at Betsey Bunky Nini, and [she] left me twenty thousand dollars, I remember. And I was like, “Oh, good, I can get a studio, I can just relax.” And my mother was like, “I want you to buy a loft with the money.” Because in those days, you could buy a loft for like ten or twenty thousand dollars. My mother was like, “Please, take the money. Otherwise you’re going to fritter it away, [and] you’ll never get anything. Buy a loft.” And I was like, “Oh, okay, I’ll do that.”

So my mother and I went looking at lofts. I bought this loft on Lispenard Street for sixteen thousand. That was where I lived—I moved into this loft. And then Bill was like, “What are you doing here?” The SoHo News, this newspaper, wanted to hire him; he was working for The New York Times. And that was like our Bible—the SoHo News was the best. That’s where we got all the information. Remember, no cell phones, no computers. We got everything from the SoHo News. It was like the hip downtown newspaper. Every Wednesday it would come out—you would buy it Wednesday morning, and you’d plan your whole week around everything it told you to do. It was just the hippest. And Bill was like, “They want me to be style editor, and I think you should be the style editor.” And I was like, “Bill, I’m an artist, I never did ‘editor.’ I don’t know what you’re talking about.” He was like, “No, you’re perfect because you live downtown but you like fashion. They need you.” My mother was already [encouraging] me to stop with the selling clothes, and I was like, “It’s better than selling clothes, right?” So I said, “Okay, I’ll talk to them.” So Bill got me this job. It was a hundred and forty dollars a week, it was like… no money. But that’s how much I was making at the store, you know—we didn’t make money. And I got this job and it was on Broadway between Spring and Broome. That’s where SoHo News was, the storefront. And they were growing pot in the window … it was amazing, they had the whole floor. It was this amazing place, and I went. I was the style editor.

AZ: Which gave you a sense of power, probably, for the first time.

KH: No, I didn’t know what I was doing! I was petrified. I was like, “What?” They were like, “You have ten pages every week that you have to fill.” And actually, they hired me and this girl Branka, who I had gone to CalArts with who’s also working at the store. She kind of came along because she wanted to get out, too. So I said, “Well, Bill…” That’s why we only got a hundred forty dollars, because I said I want Branka to come to SoHo News, too.

AZ: So you split a salary. [Laughs]

KH: Kind of, yes. It was probably three hundred dollars, probably. So we split it. So Branka came with me. Also, because I was scared. And Branka didn’t want to sell clothes. So we both came and we both shared this office. It was Branka and me at the SoHo News. We had these pages every week, and we would go to the Mudd Club. Everyone didn’t come into work until one in the afternoon because we were all out all night. You did your layouts at one in the morning, you had to go to get the art director at the Mudd Club, and she was on acid, and you had to bring her over to do your layouts—it was crazy, it was really fun.

And then I met Vivienne and Malcolm, and then they wanted to meet Keith Haring. Keith was my friend, so I introduced Malcolm. Vivienne was like, “I want Keith to do a collection for me,” and he’d never heard of her, so she said, “Could you help me?” So I hooked them up. I told Keith, “They’re good, you should do this.” And so he did it, and he did a whole collection, and I have all the clothes in my closet. But it was the first time I connected—it was fun to do that. And then I gave my pages to [Tseng] Kwong Chi, who was this amazing artist … all these artists that are dead now. Like, Keith Haring would model for me and Kwong Chi would do all the pictures, and Robert Mapplethorpe would shoot for me. I would do these crazy kind of conceptual pieces in the SoHo News. Kenny Scharf did a whole home design of the “future” section for me once. So I brought in all my artist friends to do it.

AZ: And then it folded.

Hastreiter and Paper co-founder David Hershkovits.

KH: And then it folded. [I] freaked out; I didn’t know what to do. We tried to start another newspaper. David Hershkovitz was the managing editor, so he was the word guy. But he didn’t really have the style thing under his belt. So I went to him, [and said] “If you start something, I should come with you, and let’s make it style because we’ll probably get money easier if there’s style in it.” So he was like, “Yes.” So we became partners looking for money to do it.

Meanwhile, I was working for Condé Nast, which was hideous, and I saw exactly what I didn’t want. Because corporate thinking—that’s another book I’m writing about, corporations—corporate thinking and corporate processes prevent any kind of great work. That’s when I, all of a sudden, had that “a-ha” moment when I was working for Condé Nast. I would come up with great ideas, I would pitch them, they would say yes, and then they would ruin them. I was like, “I can never work for a company.” The only thing I can do is do my own company. So that’s why I started Paper. And I’m actually going back to that because I’ve seen, through my career, the devastating effect of corporate thinking on ideas and creativity and greatness. You can never really have greatness come from a big corporation if they don’t have a megalomaniac—

“I’ve seen, through my career, the devastating effect of corporate thinking on ideas and creativity and greatness.”

AZ: Single leader…

KH: Right, which is rare. Or very few of them have this, but every once in a blue moon, you have a visionary CEO who understands this and allows the power—the whole point of corporate thinking is to not allow power for anyone.

AZ: And creativity requires freedom; you can’t control it.

KH: Yeah. My whole thing is always, the person who comes up with the idea needs to do the idea. You don’t have someone do an idea and give it to someone else to do it—you’re stupid, you’ll never get anything good out of that.

So that’s why I started Paper. I started in my house, finally, with a thousand dollars each. I was in my house for a year. My father would drive us around to the Xerox—my father would help us with distribution.

“Paper was so commercially unsuccessful because we weren’t a music magazine, we weren’t a fashion magazine. We weren’t anyone. The world wants you to be in a box. And we were about culture.”

AZ: At this point, though, you were developing a platform of your third descriptor in your email signature, which is “People Collector.” This gave you the ability to continue to meet…

KH: Yeah. And how we survived was—I remember in the old days, I remember Keith going to the show at Club 57, no one knew—and then I saw, all of a sudden, someone had told Tony Shafrazi to go to this show. And I saw Tony walk in and I was like, “Uh-oh, what’s going to happen?” And sure enough, Keith then took off like a rocket ship. And I saw Madonna dancing at the Roxy with Jellybean, and she was surrounded by Latin boys. I just watched these people take off. Absolut Vodka was starting, and they were doing ads in Interview, and I met with them and they started doing ads in Paper.

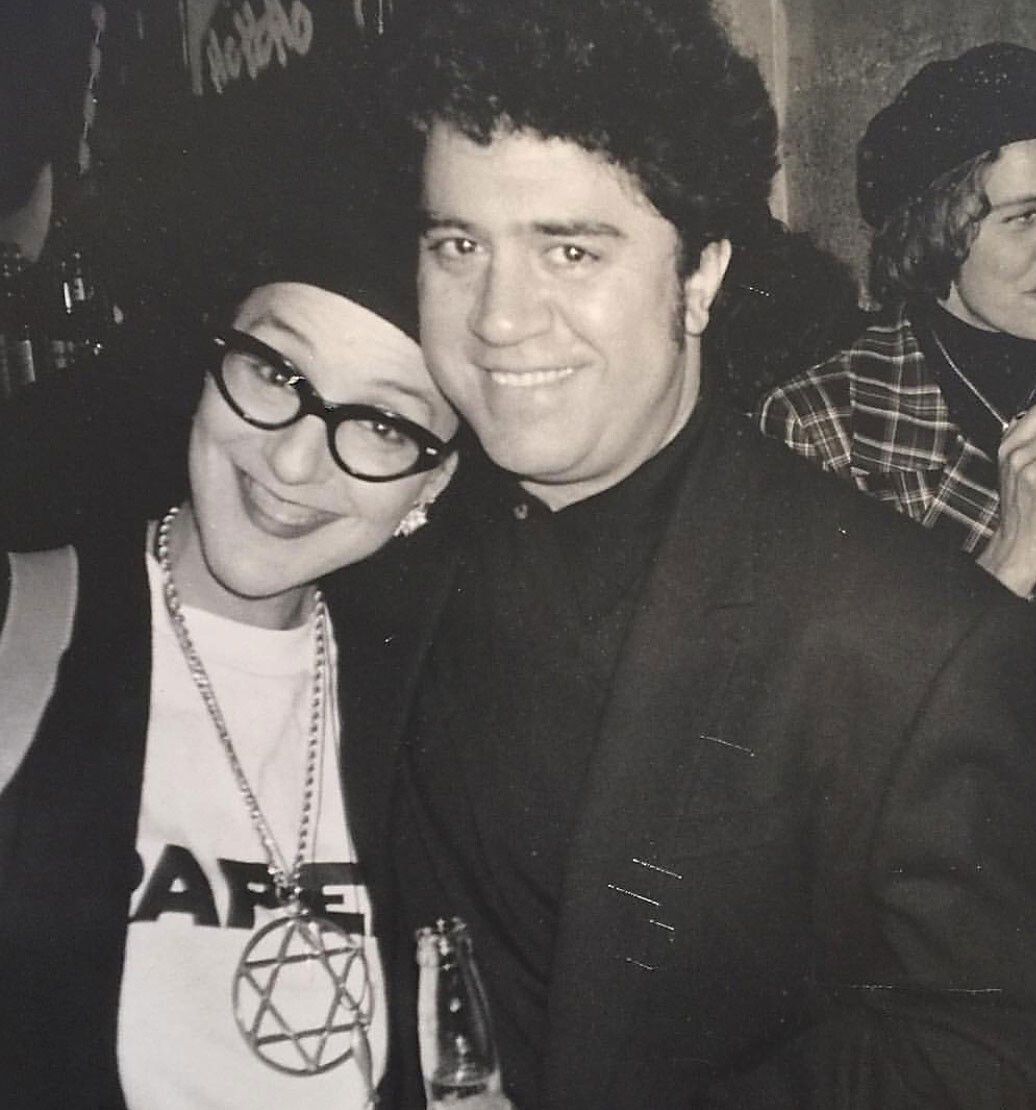

Hastreiter with her friend the filmmaker, director, screenwriter, producer, and actor Pedro Almodóvar.

I realized that all my friends were the ones who were either knew everyone who was going to be successful, but they definitely knew everything that was going to be big—if my friends loved a product, in ten years or fifteen years, that product would be popular in Iowa. That’s how I would tell them Paper, but Paper was so commercially unsuccessful because we weren’t a music magazine, we weren’t a fashion magazine. We weren’t anyone. The world wants you to be in a box. And we were about culture.

So they didn’t have a budget, these ad agencies, and our circulation was so small. I said, “Wouldn’t you rather have a hundred somebodies than a thousand nobodies?” These hundred somebodies, they are the ones that are the people that tell all the other people what to do. You have that friend—if your friend comes in town and says, “What are the top ten things?” There’s always that person that you call that knows everything. That’s the person that was our reader. Those are the people who work for us, that wrote for us, and that read us.

AZ: Do you think that’s changed? Do you think now people understand that it’s about the hundred somebodies?

KH: Yes, it’s called “influencers.” It became a name and all that. But in the early days, the ad agencies, they don’t care about that. They just want the money now, and they have the budget—you put this much money into a fashion magazine, this much money into a music magazine. “This product wants music!” So they wouldn’t advertise with us, even though we covered music, because we’re not a music magazine. So we wouldn’t get any money.

So I ended up, because I’m scrappy and I needed money, calling up the CMO or the CEO of the company, going to see them, explaining to them “a hundred somebodies to a thousand nobodies,” [thing] and they got it. I realized the people in the companies—the visionaries, the head people, because they understood—I said, “This is like an insurance policy. Buy this ad, and you’ll be popular in Iowa in ten years!” The agencies don’t think like that.

“I said, ‘This is like an insurance policy. Buy this ad, and you’ll be popular in Iowa in ten years!’”

I remember Evian was the first one. I met with the CMO of Evian, and I was like, “Well, what do you want?” and he said, “We just want to be in Chateau Marmont, we want to be on all the tables of Indochine, we want to be on the table at Odeon.” I was like, “Well, those are all my friends who own those restaurants. I can get you on the table.” He was like, “You can?” I was like, “Yeah, buy twelve ads. Twelve pages, one every month, and buy an extra quarter page, and we’ll give free ads to my friends in exchange for putting Evian on the table.”

AZ: Brilliant.

KH: So he did it. And in like two months, he was in every dream restaurant and hotel that he wanted to be in. He called me up, he said, “Kim, I spent three hundred thousand dollars last year at Condé Nast, and they couldn’t do what you did for me in six weeks.” It was like that, and I realized, that’s how I have to sell ads. So that’s what I did, I did marketing. Because it was useless to go to agencies. I went to the companies, and they understood the hundred somebodies versus a thousand nobodies, which is now called an influencer.

AZ: Right, but now, to be an influencer, you need a [hundred] thousand nobodies following you. So it’s no longer—it’s sort of become something else.

KH: No, it’s countable now. That’s what the internet did, it’s countable. And then [they] became celebrities. But to me, the other part of Paper of why we didn’t have a million circulation is because we would put people on the cover before they were famous. They would get famous in five years. Everyone who we put on the cover became really big, but not when we put it out, so we never had the big circulation. So we always missed all commerciality. We never made money. We were always poor. But we got a really amazing reputation with all the celebrities: “Paper made my career. Paper gave me my first cover” and they always gave us love because even when they became really famous, they would always do stuff for us.

AZ: And of course, these relationships extended way beyond just being on the cover. You’ve mentored so many people, and continue to today. What does it mean to mentor? How do you see it?

Hastreiter and her intern at the time, Peter Davis.

KH: I love it. I’m doing it now, actually, through April. I remember when we had money to hire one person at Paper; it was still in my house, and we said, “Okay, we can hire one person for like two hundred dollars a week.” I decided I was going to hire an office manager/intern director. An intern director, that was important. Because that person could get us more people for free. So that was my first hire, was an intern director. And we started this very robust intern program. Interns don’t just want to be schleps. They want to understand what they’re schlepping, and why they’re schlepping it, and then maybe go to the shoot and see the clothes that they schlepped on somebody and then see it in print. That’s like inspiring for them, you know? So I took a great interest in interns. I loved interns.

The people who wanted to intern for Paper were always a certain type of person because they discovered us—they were kind of like… they found their home. Everyone I hired was from interns. Drew was an intern, Mickey was an intern, they were all interns. We had an amazing internship program. Before it got complicated and people started suing, I mean, this was the early days. We lived for interns. When we got a good one, it would spread. Like they were like, “Oh, there’s a really good intern, Mickey Boardman.” You know Mr. Mickey, right? He was an intern. He was so smart. And everybody would then—we just gave them huge responsibility, we’d give interns big responsibility, “Oh, write an article.” These interns would be writing for us or going to a celebrity shooting and sitting and seeing Barry White—

AZ: But even outside of these people, you’ve always had people who you took an interest in and gave them opportunity.

KH: Well, also, I’m a truffle hunter, so if I find someone doing genius work, I freak out. I have to meet the person—I don’t care if it’s an artist, furniture designer, writer—

AZ: Chef.

Hastreiter with Tauba Auerbach.

KH: Photographer, chef, anybody—I have to meet this person. Then I’m like, “Oh, my God, who the fuck are you and where’d you come from?” I meet them, I have lunch with them, I write about them, I get them to maybe do something for Paper.

Tauba [Auerbach], who’s very reticent and she was a hard one to crack, but I fell in love with what—I went to her first show, I got her “A,” her seminal piece, “How to Spell the Alphabet.” I loved Tauba’s work, and I just stalked her until I became friends with—people like to be appreciated, you know. And also, when they came to Paper, if they were photographers or illustrators, like Coop, you know, I loved Coop. But I’d come up with an idea and I would just give him the pages. I was like, “Here are the clothes,” I’d send him pictures of my favorite couture from every designer, and he’d do these insane things and I’d run them twenty pages. Or if I loved a photographer, I’d say, I need to shoot shoes. “Here are the shoes. Make sure you can see them, that they’re not like this [pinches fingers] big, and do whatever you want, and give me like eighteen pages.”

AZ: Have you found that old saying “When you give, you’ll receive” to be true?

Hastreiter and David Byrne.

KH: Yeah, I mean, definitely. Just when you give freedom to amazing creatives, you have to trust it. And yes, there’s failure, definitely, but like… As Four were people that I mentored forever, these crazy kids. And the first time I gave them total—I had them do a piece in Paper, I just said, “Okay, just do. Whatever you do, I just want to see.” And they shot this amazing piece in a supermarket in New Jersey. It came out really amazing. I didn’t get a lot of credits, but it was still fantastic. And then I gave them a show. And they came to me because I kind of wanted to know about this thing in Bryant Park, “What are you doing?” And they said, “Well, we have these dolls from Canal Street, and look what they look like without heads.” They were this big [gestures] “and we’re going to buy a lot of them and we’re going to do something amazing.” And I was like, “I have no idea what you’re talking about, but okay,” you know what I mean, you just have to go with it!

AZ: Have you found that there are sort of throughlines between creative people?