Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

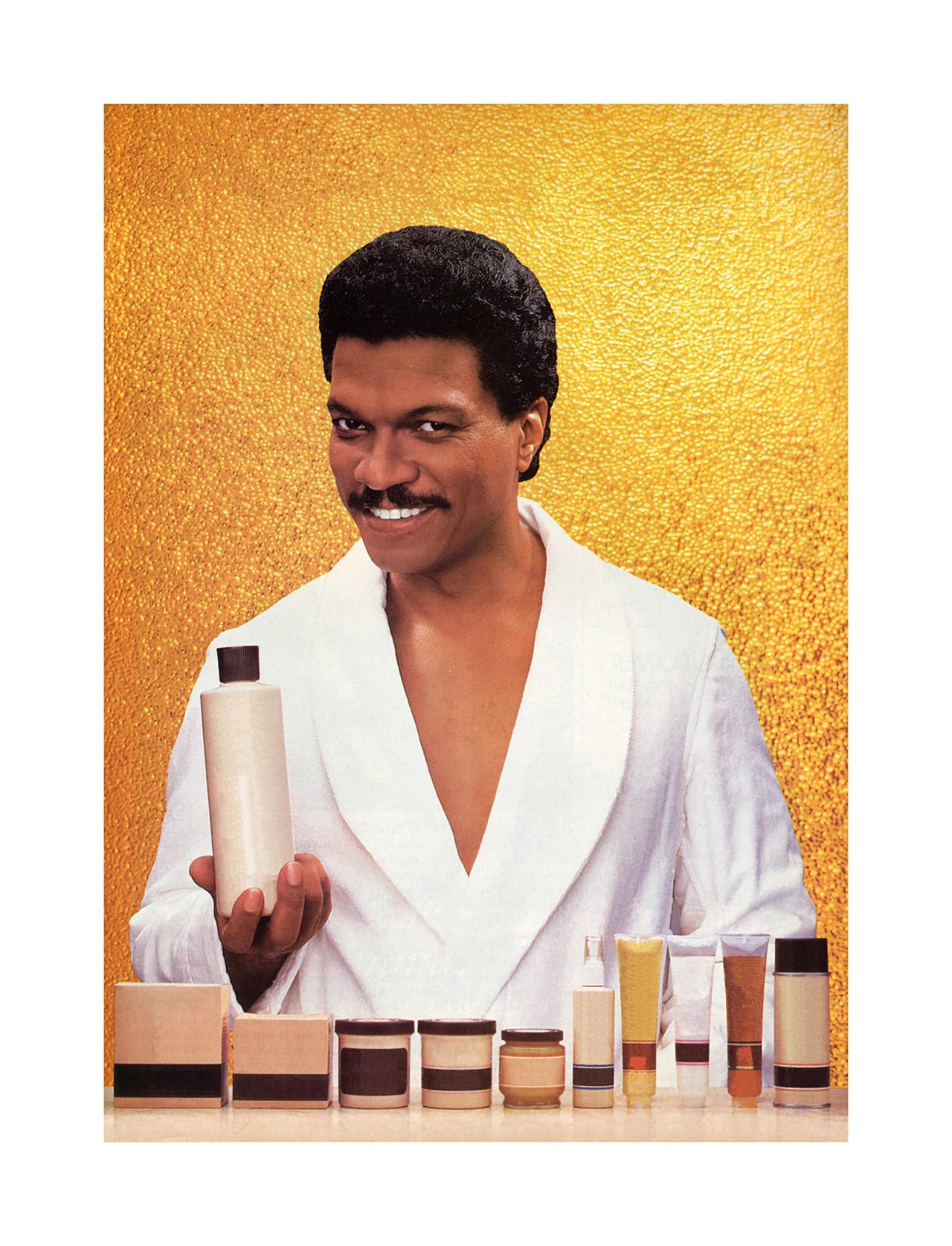

Hank Willis Thomas. (Photo: Levi Mandel. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts London)

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Hank. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

HANK WILLIS THOMAS: Thank you so much. It’s really great to be here.

SB: So you’re someone who spends a lot of time thinking about words, symbols, advertising, images. Looking at and processing archives of photography and consumer culture has largely been what we might say is your life’s work, and so I wanted to start there. It’s a broad question, but how do you think about your time spent reconsidering photographic messages?

HT: How do I think about it?

SB: Yeah, the time spent.

HT: Well, this is a time-sensitive question. Well, the way you ask it makes me feel like I’m wasting my time. [Laughs] I definitely appreciate the power of now, and funny that you asked that because as a photographer, it’s all about capturing the moment and being in the moment completely so you can capture the moment. As a photo conceptual artist, I’m usually referencing the past thinking about the future. So the now rarely plays a role in the work that I do, and I’d never really thought about that until you asked this time-sensitive question.

SB: Well, has this work reshaped how you think about time more generally? What role does time play in your work, and how do you think about it philosophically?

“As a photo conceptual artist, I’m usually referencing the past, thinking about the future. So the now rarely plays a role in the work that I do.”

HT: Well, again, I got into photography not only because my mother, Deborah Willis, is a photographer, and art historian, and a photo historian, but because I loved the process of capturing time. Putting split seconds of time in a window of art was really exciting to me, and then the processing. Everything, when you’re capturing the film, and then you’re processing the negatives, was all about time. And then, you print the photograph, and it was all about time.

In the digital age, literally, you can take a photo and print it almost instantly. Time has become, especially in this post-Covid moment, very elastic. When I think about 2020, it seems like that was ten years or five years in one year, and I think about 2022, it feels like three months. So, I am, from a personal perspective, really excited about presencing the very moment that I’m in with you now. I’m also thinking about the people in the future who are listening to this now, or then. And my work, especially on the cusp of putting a monument in Boston Common—

SB: We’ll get to that.

HT: —is timeless.

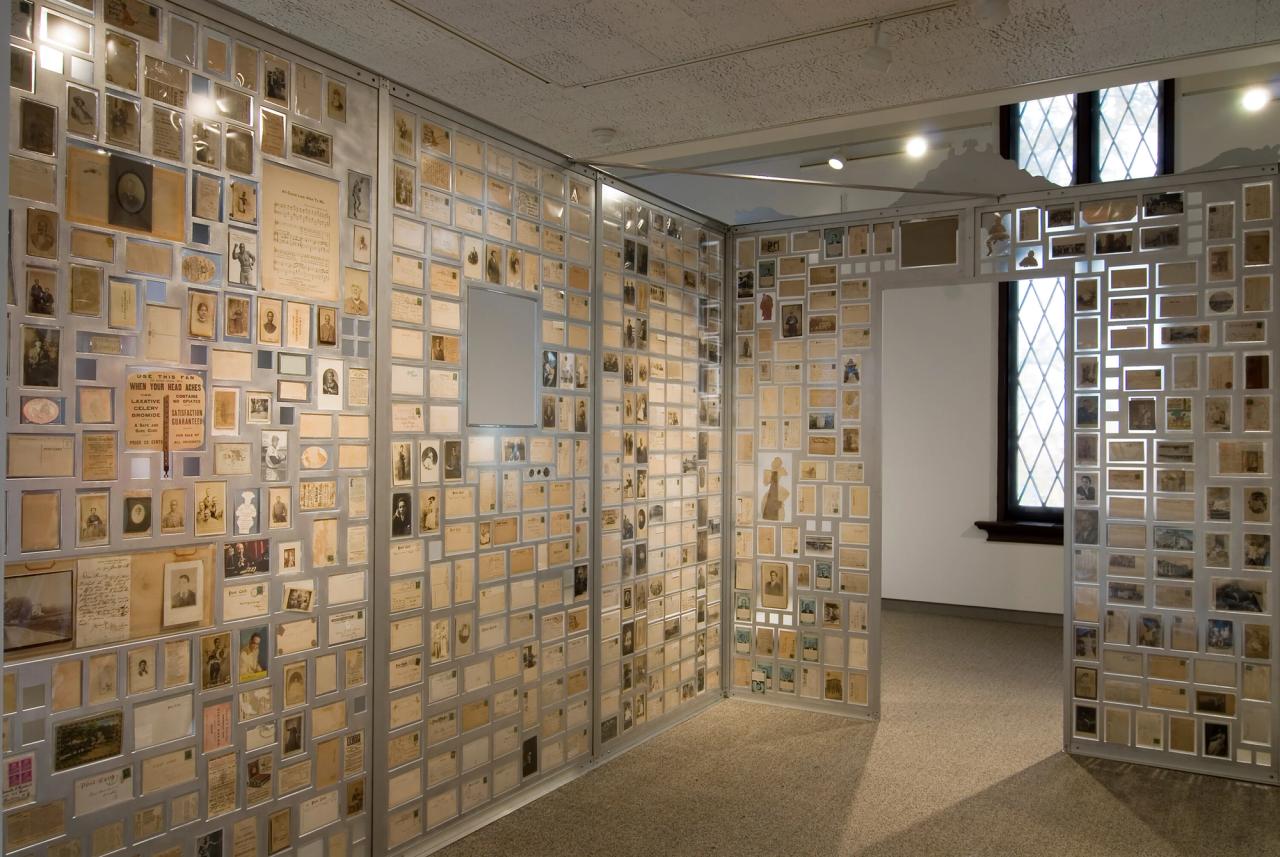

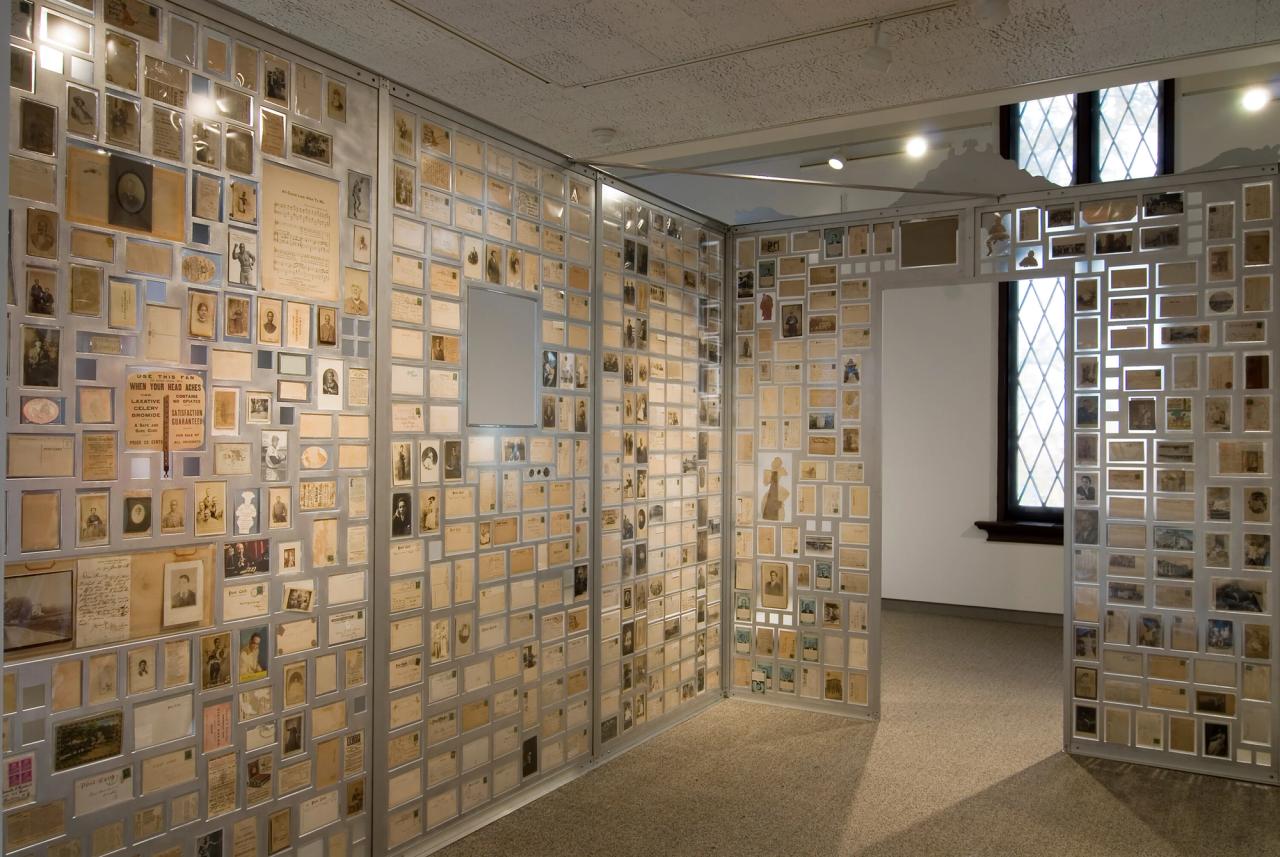

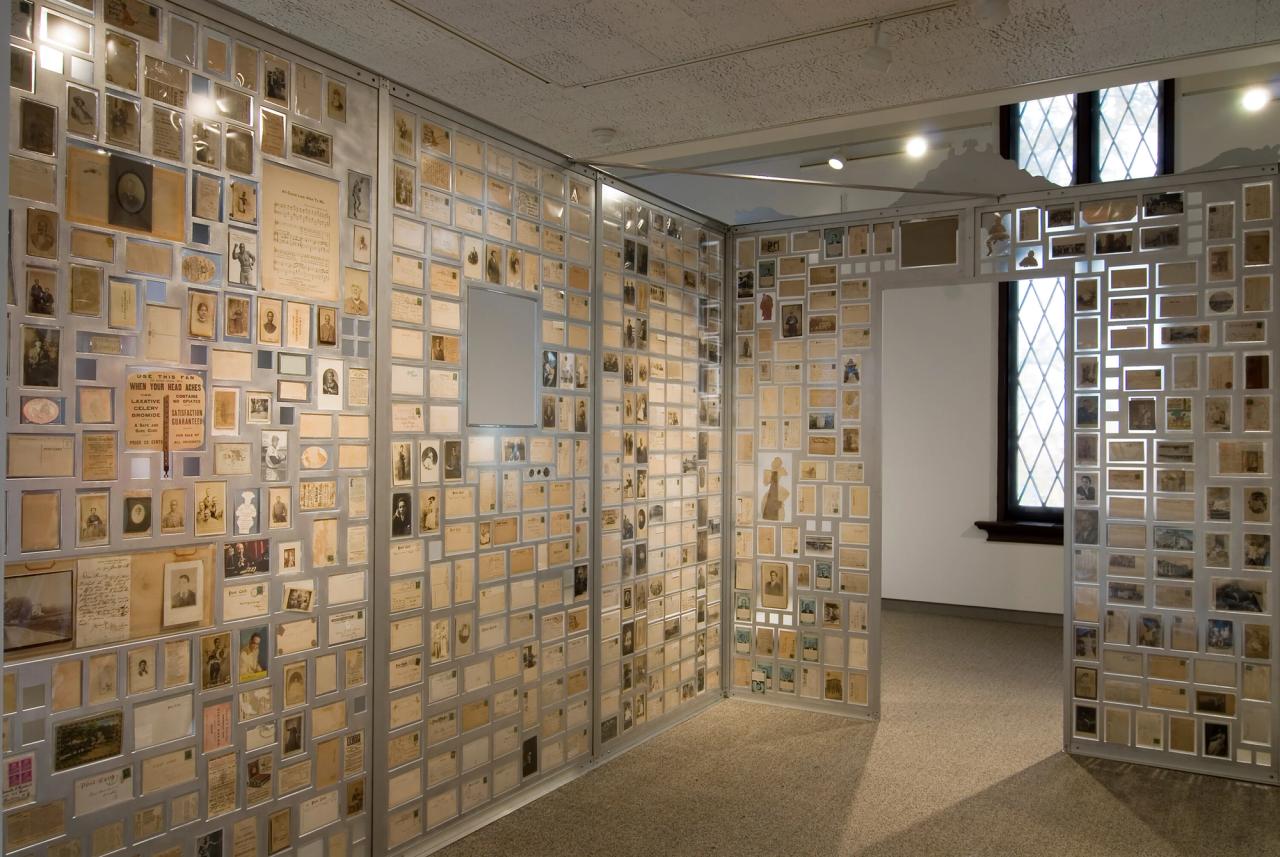

Installation view of “Remember Me” (2014) at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York. (Courtesy the artist)

SB: I was hoping you might speak here to a specific piece, “Remember Me,” which was recently on view at the Parrish Art Museum in terms of finding the source material, thinking about how to use and incorporate that source material. Basically, talk about that piece from the perspective of time.

“I think about postcards as nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century email.”

HT: Sure. Well, I was in a show [“Digging Deeper”] in 2009 that was a collaboration between myself and another artist named Willie Cole at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum [Museum of Art]. Willie and I were tasked to go through the archive and dig deeper, and so we spent a lot of time up at the museum in the stacks and the archives, and I was fascinated with all of these postcards. They had this amazing postcard collection of a lot of caricature racist postcards. And then mixed in were some very contemporary of that moment—nineteenth century and early twentieth century postcards—that were colloquial. People were quotidian. I guess people were just writing postcards to their loved ones and sending them. I think about postcards as nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century email. They were the first generation of people who could have an image or text—

SB: DMs.

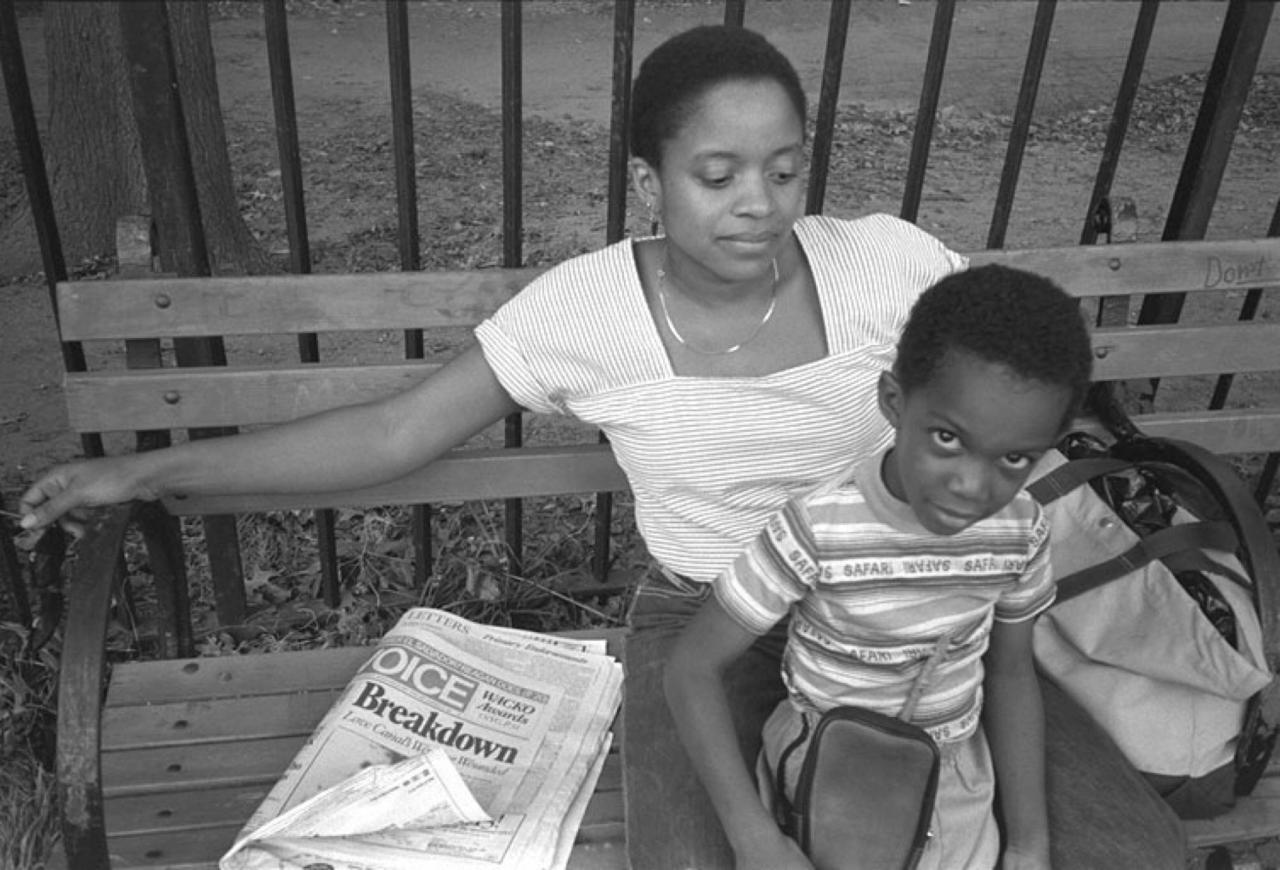

“For people who were either the generation of slavery or one generation removed, to be able to take a photograph of yourself and send it to your loved ones was huge.”

HT: Yeah, and send it far away, and someone would get it, which was pretty nuts. For people who were either the generation of slavery or one generation removed, to be able to take a photograph of yourself and send it to your loved ones was huge. And so looking at African American vernacular photography, as my mother has done, I’ve recognized that the Black experience is not what we read about in newspapers, or in history books, or in popular culture. In fact, it is a human experience. There is no specific Black experience. There are people of all kinds of ethnicities who leave their families, who have been ostracized and leave their home or leave their family because of systematic oppression and also, still want to be seen, as an attempt to be seen as human beings. Photography has been a landscape where a lot of people have been dehumanized, and also, people have chosen to claim their humanity.

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

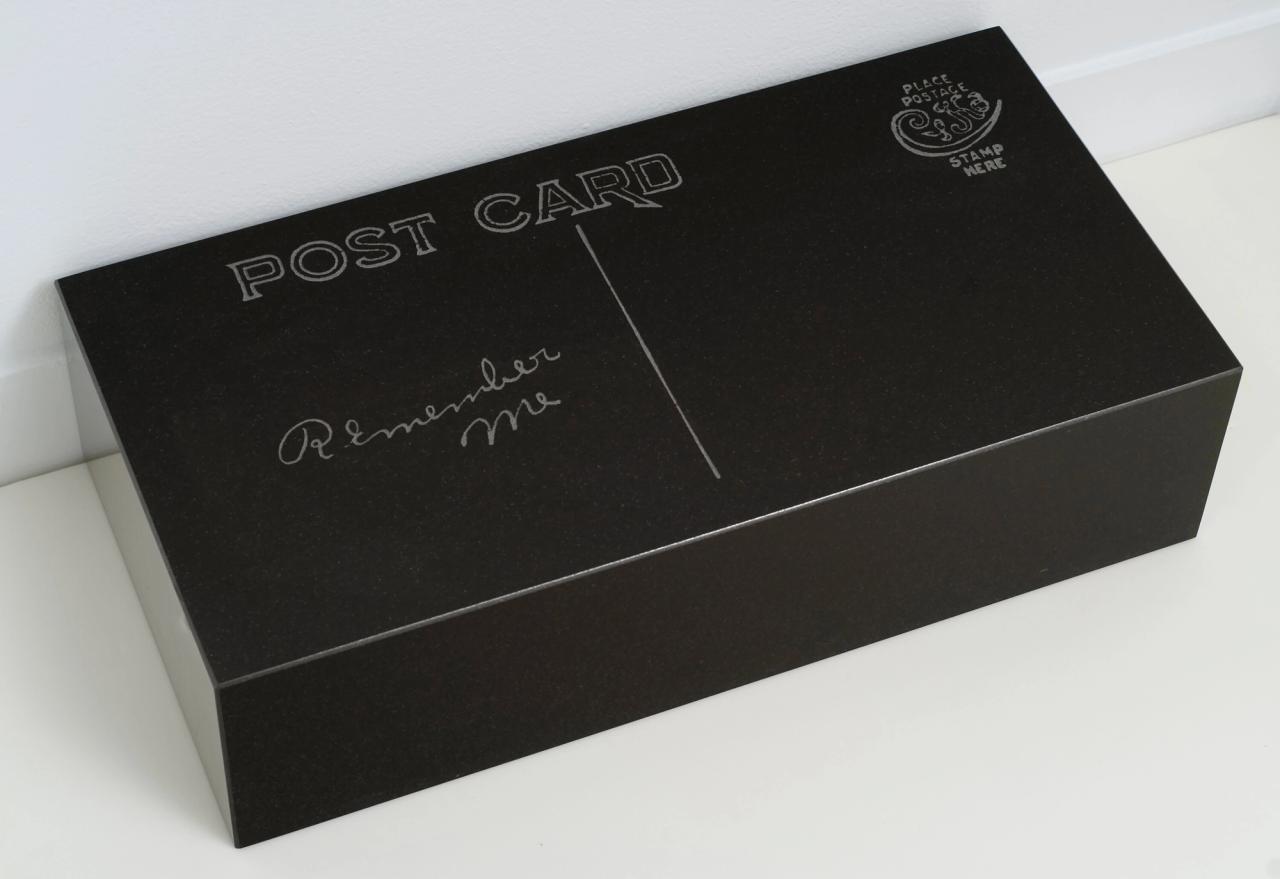

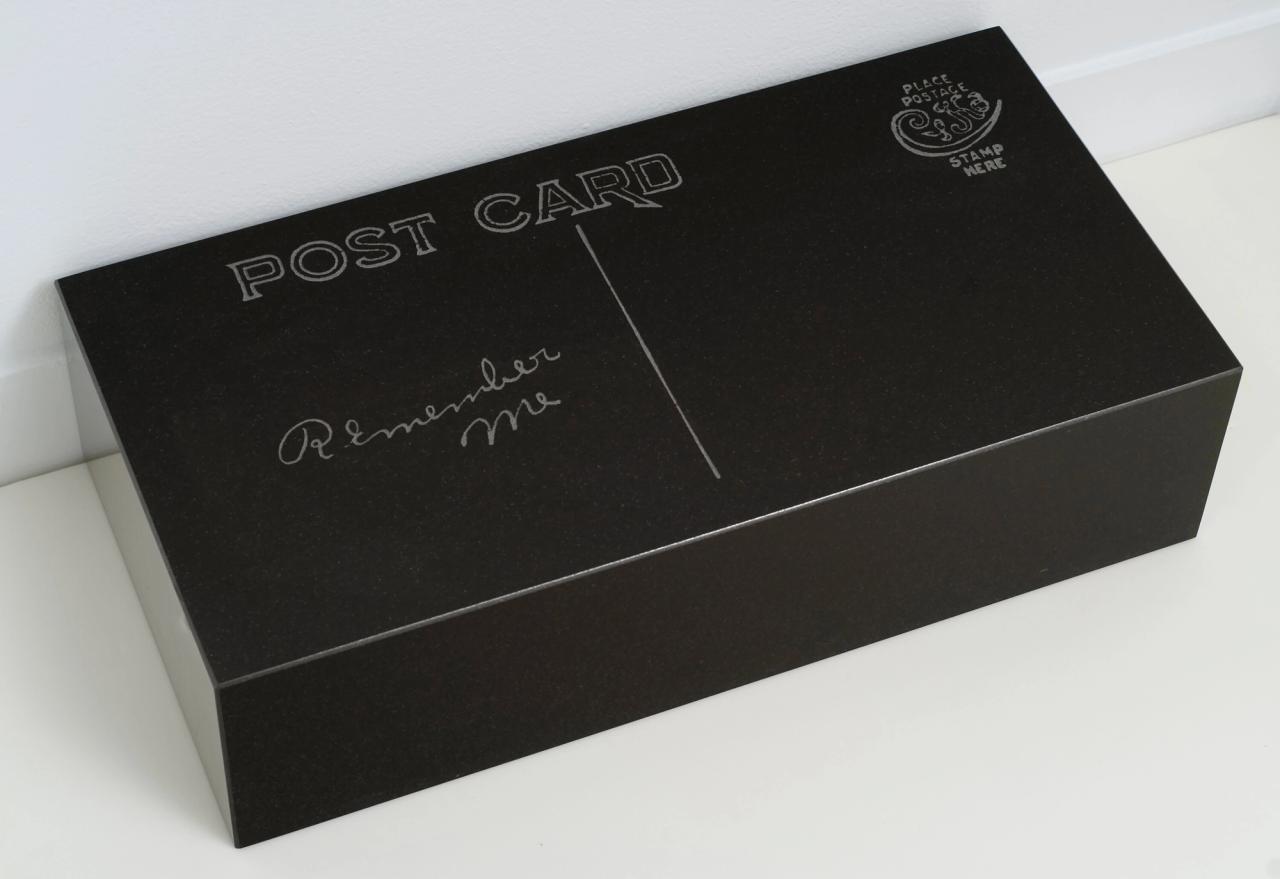

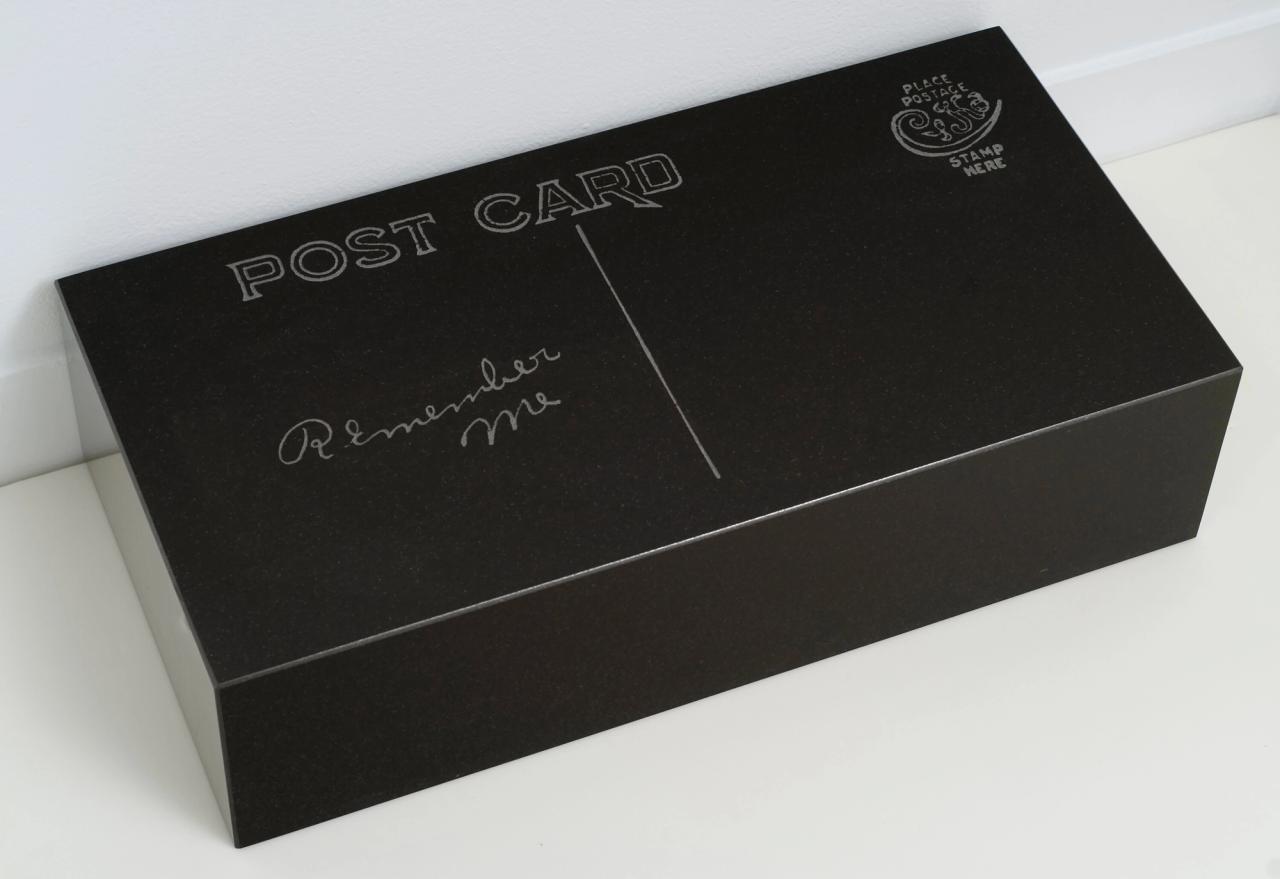

An item on view at Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

An item on view at Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

An item on view at Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

Installation view of Thomas’s show with Willie Cole, “Digging Deeper” (2009), at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

One of the postcards Thomas presented at his joint show “Digging Deeper” (2009) at the Amistad Collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. (Courtesy the artist)

And so, how I think about time is related to that, as you can tell—one of the postcards I found, I should say, said… It was a postcard of a presumably African American man with a World War I cavalry hat on, standing in front of a barn and a farm with a rifle, denim jeans, and a white button-up coat, which looks like his Sunday’s best. Just looking at that postcard, I’m like, “Okay, a Black man from a hundred years ago with a gun, who clearly is signifying that he was a soldier.” Then I turned it over, and all that was written was, “Remember me.” That was like, “Whoa.” Because he, in that instance, whoever wrote that, transcended space and time. They brought me back to their moment. They brought them into the future.

SB: And it becomes this neon sculpture at the Parrish.

HT: Yeah. So, ten years after I find it or twelve, thirteen years after I find it, I did make a neon, like five years, of that handwritten text. It was so beautiful. But in the Parrish and also in work that I finally got around to making, I actually used that image with the retro-reflective technology that I’ve developed in photographic printing and that handwriting in that way. But now, also, many people who are going up and down [Route] 27 will be seeing at nighttime and daytime that person’s handwriting. For all we know, because this was found in Hartford, Connecticut, and we know that there was a long tradition of Black farmers in Eastern Long Island, it could be where this person was standing when they took the picture, which is really nuts.

SB: Memory and remembering in many ways are the core of your work, and I was hoping, maybe could you speak to the relationships between slowness and memory, and between speed and forgetting, and how this distinction connects in your artmaking? Because I think it’s very visible there.

HT: Well, when I think about digital photography, that’s where I’m mostly connected to speed and forgetting. What I loved about analog photography is that I did have to remember so much to take a picture, and I did have to remember so much in the process of making the print. The memories I have of making that work are very different than a picture I took, and then maybe I did some Photoshop work on, and then put out into the world because it’s… There isn’t this, and I’m not romanticizing it—actually, there was a muscle memory in the making of pictures before. Where now, it’s like, if you give me a digital camera, I’m just going to take a thousand pictures, and then maybe I’ll edit them, maybe someone else will edit them, and it will be like, “Okay. That one sounds good.” But I’m not as careful as some other photographers about the finest detail of every picture, because I feel like their pictures are forgettable in a way that they weren’t before. I remember the [World Press] Photo of the Year, and we now consume tens of thousands of photographs every day. So how does one stick out? And if it does, it’s usually a meme. It’s not like…

“We now consume tens of thousands of photographs every day. So how does one stick out? And if it does, it’s usually a meme.”

SB: A GIF or a… [Laughs] Yeah.

HT: Yeah.

SB: Memorialization—or the idea of it, anyway—and the relationship between art and civic life runs through your work. If not all of your work, most of your work. And soon, you’re going to unveil with one of your collaborators, MASS Design Group, “The Embrace,” which you were alluding to earlier, this twenty-foot high circular bronze monument in the Boston Common that honors Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King. Tell me more generally about your approach to the notion of memorializing something and how that comes to light in this King project.

A rendering of Thomas’s sculpture “The Embrace” (2023) made in collaboration with MASS Design Group. (Courtesy the artist)

The photo of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King, on which Thomas based his sculpture “The Embrace” (2023). (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

HT: My approach to memorializing things really does start with the work of my mother, Deborah Willis, who I mentioned earlier. Her first book was called Black Photographers 1840-1940: A Bio-Bibliography. What’s critical when you just think about the title, Black photographers in 1840.

SB: Astounding.

HT: Which is, what does that even mean? When we’re told that at that time, everybody that’s Black was illiterate and everyone that’s Black was a slave or disenfranchised. And it’s not to say that these people were literate or not disenfranchised, but it is to say that their lives were clearly more complicated because to be able to make a photograph in 1940 or 1939, as Augustus Washington, one of the photographers she highlights, did, is like, you had to know… You had to understand physics, and chemistry, and mechanics, and then—

SB: It’s a science experiment.

HT: You had to have the means to get or build a camera, and build glass plate negatives or whatever that would be able to make a lasting image. Then you had to have the curiosity to go about looking at the world in this contemplative way that photographers do. And then you had to have the confidence that you were the one worth doing it, so that your name is still attached to that image. So when I think about memorial, I think about how people a hundred fifty years from now might consider what I’m doing and what I’m a part of.

“Most of what we know about past societies and civilizations is what remained or was retained in the art.”

So “The Embrace,” which is a monument to love, is as much about love of all human beings as it is about Dr. King and Mrs. King because a hundred fifty years from now, if human beings are still alive, there probably won’t be any internet, and there probably won’t be any form of knowledge about this post-apocalyptic time. But seeing this embrace, these arms embracing, that will be something that they can still connect to and translate. Most of what we know about past societies and civilizations is what was remained or retained in the art. We don’t always understand how the languages were spoken, or who was important, or what was important, but we can actually look at the art and get some form of sensibility that we can relate to. So my memorials are for those people.

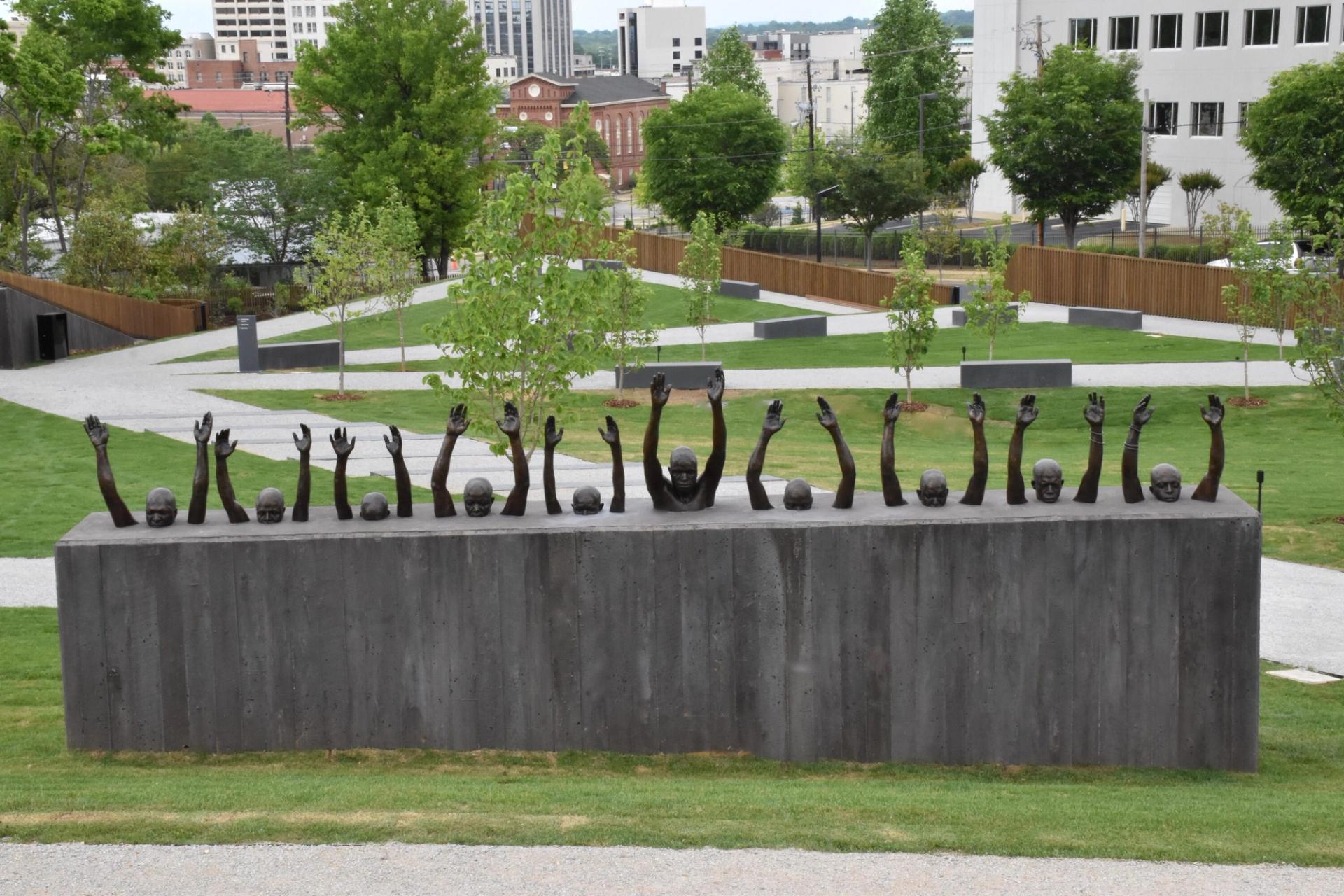

Thomas’s sculpture “Raise Up” (2014) at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s sculpture “Raise Up” (2014). (Courtesy the artist)

SB: Yeah. Another memorial of yours, at least how I view it, is “Raise Up.” It’s this sculpture, ten heads and twenty raised arms at MASS Design Group’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. It has also existed as smaller sculptural works elsewhere. Could you speak to the particular approach to conceiving that piece, and do you view it as a memorial?

HT: Sure. So, Bryan Stevenson, a civil rights lawyer who is from Alabama who recognized that in order for us to really address the atrocities of slavery, and lynching, and also, even mass incarceration, we needed to have a locus. So he invited me to consider with him what to do to do that, to make a memorial to those, in this case, people who were lynched. In talking to me, he talked to MASS Design, Michael Murphy specifically for MASS Design, and other people, and MASS came up with a really brilliant concept in collaboration with him, which what ultimately became the memorial site that we see in Montgomery now, and what was going to be my brilliant idea [laughter] wound up being a part of the larger memorial, which is a huge honor.

“I am often asking myself and others to be aware of the multiple readings that we can have on history and on a specific moment.”

The work “Raise Up” that’s in it is about submission and surrender, but it’s also about faith and humanity overall. I am often asking myself and others to be aware of the multiple readings that we can have on history and on a specific moment. That comes from my experience being a photographer where I could be standing right next to someone, and their picture may not be any more true than mine, but it may be more seductive, and realizing that ten people can be taking a picture or looking at the very same thing and have a very different truth be emerged because of the seductiveness of the image.

SB: I think what’s also interesting here is this merging of the figurative and the abstract, and that there’s enough figuration to allow you to imagine what’s being depicted, but there’s so much abstraction within it that it allows for a multitude of interpretations.

HT: Mm-hmm. You’re giving me all kinds of images now.

Installation view of the Gun Violence Memorial Project at the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial. (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

SB: [Laughs] Another memorial you’ve worked on also with MASS Design Group is the Gun Violence Memorial Project done in partnership with the prevention organizations Purpose Over Pain and Everytown for Gun Safety. This debuted in 2019 at the Chicago Architecture Biennial and most recently was on view at the National Building Museum in [Washington] D.C. It comprises a series of houses each made with 700 glass bricks, this reference to the number of people in the U.S. killed by guns every week. When Michael Murphy was on the podcast, he told me a little bit about how this project came to fruition, but I thought it’d be meaningful for you here to share your own personal connection and reason for feeling so tied to the project, and so, why it’s so personal for you.

HT: Yeah. Well, I did, from my recollection, and Murphy’s might be different, but we were walking up to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and he had just been speaking to Everytown, and Purpose Over Pain, and other people, around the impact of that monument. I mentioned that I’d always wanted to do a monument for victims of gun violence because I went to high school in D.C. I grew up in New York, but I went to high school in D.C. and was surrounded by memorials everywhere. There’s a World War II Memorial. There’s a Vietnam [Veterans] Memorial. There’s a Lincoln Memorial. There’s all kinds of memorials.

“There are more people shot and killed every year in the United States than have died in the past two dominant American wars. To think that in some parts of this country, you are less safe than those in a war zone is pretty insane.”

HT: Now, there’s a MLK Memorial. There’s a [Thomas] Jefferson Memorial, et cetera. But there are more people shot and killed every year in the United States than have died in the past two dominant American wars. To think that in some parts of this country, you are less safe than those in a war zone is pretty insane, and that there will be justified memorials to the soldiers who dedicated their lives and lost their lives to these wars. There is no place to memorialize people like my cousin, Songha Thomas Willis, who was murdered on February 2, 2000, and then the nearly half a million people who were shot and killed since he died, which is just kind of crazy to think that we have, if not a pandemic, an epidemic in our country that we’re unwilling, much like lynching, to make a space to really come to terms with.

And so, I have made my own memorials where I’ve been taking, using flags—well, making flags—that are thousands of stars representing the number of people who were shot and killed by others in each year and draping these kind of all-star flags across the ground. But I was excited about the idea that we came to with MASS around the artifacts because my cousin, Songha, I still have some of his clothes. When I’m gone, who will be able to tell the difference? I thought that it would be really important to memorialize some essence of him through putting an artifact in a memorial like this. I am really just excited to be a part of that memorial, which is really just a prototype for what hopefully will either become an obsolete idea or a really important memorial in the future.

Installation view of Thomas’s sculpture “Unity” (2019) at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge. (Courtesy the artist)

SB: Extending out of this work, I did want to bring up one last public work of yours, “Unity,” this twenty-two-foot bronze arm with an upward pointing index finger. It’s at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge. Do you view that as a memorial, and how does that connect?

HT: Well, “Unity,” again, is something that someone a hundred years from now, or 1,000 or 500 years from now will see, and they will have their own phenomenological relationship to it just like someone today. There is another symbolic message to have a twenty-two-foot bronze arm pointing to the sky in this moment because bronze is typically not used to represent, across our country, people of African descent, whose skin is bronze.

For this work, I did 3-D scan the arm of Joel Embiid, who’s got a rather large bronze arm. He’s a center for the Philadelphia 76ers and an African immigrant. That sculpture was inspired by a photograph I found in 1987 or ’86 of Meadowlark Lemon of the Harlem Globetrotters spinning a basketball on his finger in front of the Statue of Liberty. I recognized the connection between upward mobility and social mobility through sports and the mobility of immigrants from foreign places to the United States, and I thought that Joel and his story is a powerful connection between those things. Then, the simplicity of that, an arm pointing to the sky, could just be an arm pointing to the sky. It could be symbolizing unity. It could be saying we’re number one. When I put it up, reputable news agencies asked me if it was an ISIS symbol. [Laughs] So, art is open to interpretation.

SB: Wow. [Laughs] Let’s go back to your youth, and I want to start here with Roy DeCarava’s 1983 exhibition, “The Sound I Saw,” which was at the Studio Museum. You’ve described that show as “major” for you, and that you see it as what you’ve called a “head trip.” What about DeCarava’s work do you find so moving, and are there any particular images from that exhibition that stick with you in your mind today?

“Where we are conditioned or trained as photographers to capture an image, freeze it, and make as much visible as possible, Roy DeCarava was really digging into the darkness.”

HT: Well, first, I saw the show at the Studio Museum as a child and didn’t really connect to it, but the catalog from that show was on either my coffee table or in the house. It was one of the most prevalent books in my childhood. But when I saw his retrospective at MoMA [in 1996] when I was in college, I had a very different relationship to the work. What I saw in that book with photographs of John Coltrane and various other luminaries was an artist painting with light. Where we are conditioned or trained as photographers to capture an image, freeze it, and make as much visible as possible, Roy DeCarava was really digging into the darkness, and so he would use elements and highlights of light as the whole form of the photograph. And so, the book being titled The Sound I Saw was a head trip for me, even as a kid, because I was like, “How do you see sound?” As a photographer who’s really invested in translating experience through his medium, Roy DeCarava did that with motion and light. I recognize that photography is clearly an art form when a person can make such poetic, and profound, and deep, and sometimes abstract, images through their approach to representing their experience.

“Sometimes I See Myself in You” (2008) by Hank Willis Thomas and his mother, Deborah Willis. (Courtesy the artists)

Thomas speaking with his mother, Deborah Willis, at their joint TED Talk in 2017. (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

SB: So, your mother, as you mentioned, is a photographer and art historian. She’s written thirty-some books. She teaches at N.Y.U. Your father [Hank Thomas, Sr.] is a jazz musician, film producer, was a member of the Black Panthers. You and your mom have spoken a bit about your symbiotic relationship in this great TED Talk, and you grew up in this house full of not just great books on photography, but great photographs. How would you describe this environment, and in retrospect—and yes, this is probably a pretty obvious, but vital question—what impact do you think your parents had on you becoming a photographer and artist?

HT: Well, my parents—my father was born in the segregated South, my mom was born in a version of the segregated North, in Philadelphia. But they both were the first generation of African Americans to get a crack at freedom. I use “crack” because I’m referencing Jackie Robinson with the cracking of that baseball bat in 1955 when the Brooklyn Dodgers won the World Series. That sound of his iconic home run really did open the door for generations of African Americans who were coming up to go out into the world in ways their parents never could have imagined.

Thomas as a child with his mother. (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

So, my father lived in Europe. I mean, he was drafted into the war because of racist draft policies, blah, blah, blah, but he lived in Europe, and he studied at Columbia, and got a Ph.D. in physics, and traveled the world doing art, and real estate, and whatever else he wanted and did. My mother, who did go to junior college for typing, decided that at some point, she could and should be a photographer, and went to graduate school for photography, and again, traveled the world doing what she loved.

Growing up with two parents who followed their dreams, I don’t think I had much choice as to whether or not I could or should. I was not really interested in art, per se, because all my mom’s friends were broke. Many of them now do have MacArthurs, and I don’t know how rich they are, but they’re not broke. Many of them are. But I also realized that you don’t go into making art to make money; you go into art to make an impact on yourself first, and then on the audience that interacts with the work. There is no greater reward than feeling transformed by something that you’re a part of making.

Thomas as a child with his mother. (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

SB: I want to touch briefly on your education. In high school, you left to Episcopal, this boarding school in Alexandria, Virginia, for a year, then attended Duke Ellington School of the Arts in D.C., as you mentioned, which had a museum studies program. Then, you go on to N.Y.U. Tisch—

HT: Before my mom was there.

SB: [Laughs] Spent four years there, then onto California College of the Arts for your M.F.A. first in photography, then for a second master’s in visual and critical studies. You studied with Jim Goldberg, Chris Johnson, Larry Sultan, and from what I understand, CCA and the Bay Area at the time—this is the early 2000s—was sort of a training ground for collectivist thinking. I mean, it’s long been that, but particularly around artmaking, the sort of collective art groups, and that’s something that’s become really central to your work today. And so I wanted to ask, how do you think now about this path from Episcopal to CCA? And what did your time at CCA, in particular, do in terms of shaping this collectivist artist approach?

“These critical moments in my youth—like, 14, 15, 16—each year, I had to almost reimagine myself.”

HT: Well, first, I do want to start, I mean, I went to elementary and junior high school in New York City. I didn’t get into any of the fancy public schools or private schools, but my cousin, Songha, who I mentioned, was going to this private boarding school. He was an athlete in D.C., and I got in because I was his cousin, and they just assumed because of either racism or sleight of hand that I would be talented in sports and academics the way that he was. I was not in either [laughs], and so that’s the main reason that I only went there for a year. But I also got to go from being in a pretty multiethnic environment in New York to a place where it was, like, three hundred students—all boys. Maybe there were twenty Asian international students; two Latinx people—they were also international; and eighteen Black students, mostly African Americans. So I went from being kind of one of many, in New York, to being part of a super minority, in Virginia. So, this case, Confederate flags were in dorm rooms and statues to Confederate soldiers were things that people had in their rooms or on their desk. They talked about the pride of the South, and that was like a whole learning for me, around the complexities of American patriotism.

Thomas’s parents, Deborah Willis (left) and Hank Thomas (right). (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

And then going from there to Duke Ellington School for the Arts, which is even named after an African American transcendent artist, where that case was almost the exact opposite where I became part of a super majority. There were like thirty white students, and 400 African Americans, and five Latinx, and five Asian students. So experiencing the racism from the super majority to being part of a super minority that was not as sensitive as some might think to other ethnicities was really profound because I had to figure out, “Who am I?” I’m a New Yorker, then I find myself in D.C., and then in Virginia, then I’m in D.C. So these critical moments in my youth—like, 14, 15, 16—each year, I had to almost reimagine myself.

SB: Yeah, and from what I read at Tisch, you were, during your four years there, the only Black student in the photography program.

HT: Only Black male. Yes. So I went to N.Y.U., and there was that experience in Tisch. I kind of felt the burden of representing Black male identity in school, which was a heavy burden for an 18 year old. And then in graduate school—so after I graduated undergrad where I studied photography and Africana studies, not knowing I was really following my mom’s footsteps, but then, I did work as a photographer’s assistant, and a production assistant, coordinator, et cetera on film and commercial shoots. But I interned at The Chris Rock Show, I was on the Saturday Night Live film unit, which were both social commentary media. It wasn’t typical, and there were commercials—Victoria’s Secret and others—that I worked on. But being part of film sets that were looking at popular culture and critiquing it, was really educational to me.

Thomas (center) with his mother (second to left) receiving his honorary doctorate degree at the Maryland Institute College of Art. (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

So when I went to grad school, and I was studying with Larry Sultan, who was both being a commercial photographer, I think my first year, he shot the first [Air] Jordan campaign for Jumpman. It was right after Songha was murdered. But Larry had also in his practice, Larry collaborated with Mike Mandel on doing nearly a hundred billboards where they were what we now call “culture jamming,” where they were like making critiques of consumerism in often co-opted billboards that they were doing. But it was very much about collaboration.

I like to say I got to the Bay Area right after it was fun because the first dot-com boom in the late ’90s kind of killed all the true creative energy in the Bay Area. But when I got there, it was a dot-com bust, so there was still some residue. [Laughs] They hadn’t kicked everybody out like they had now, but there was some residue of the carefree, creative, collaborative, Summer of Love artmaking energy. Yeah, artists like Jim Goldberg, and Todd Hido, and Chris Johnson were very much critical to my education. And Suzanne Lacy, who had created the Center for Art and Public Life, had introduced me to this idea of social practice and making art that has social impact. So I took all that together and started collaborating with other artists, almost from the beginning, but primarily in 2006 with a public art video called “Along The Way.”

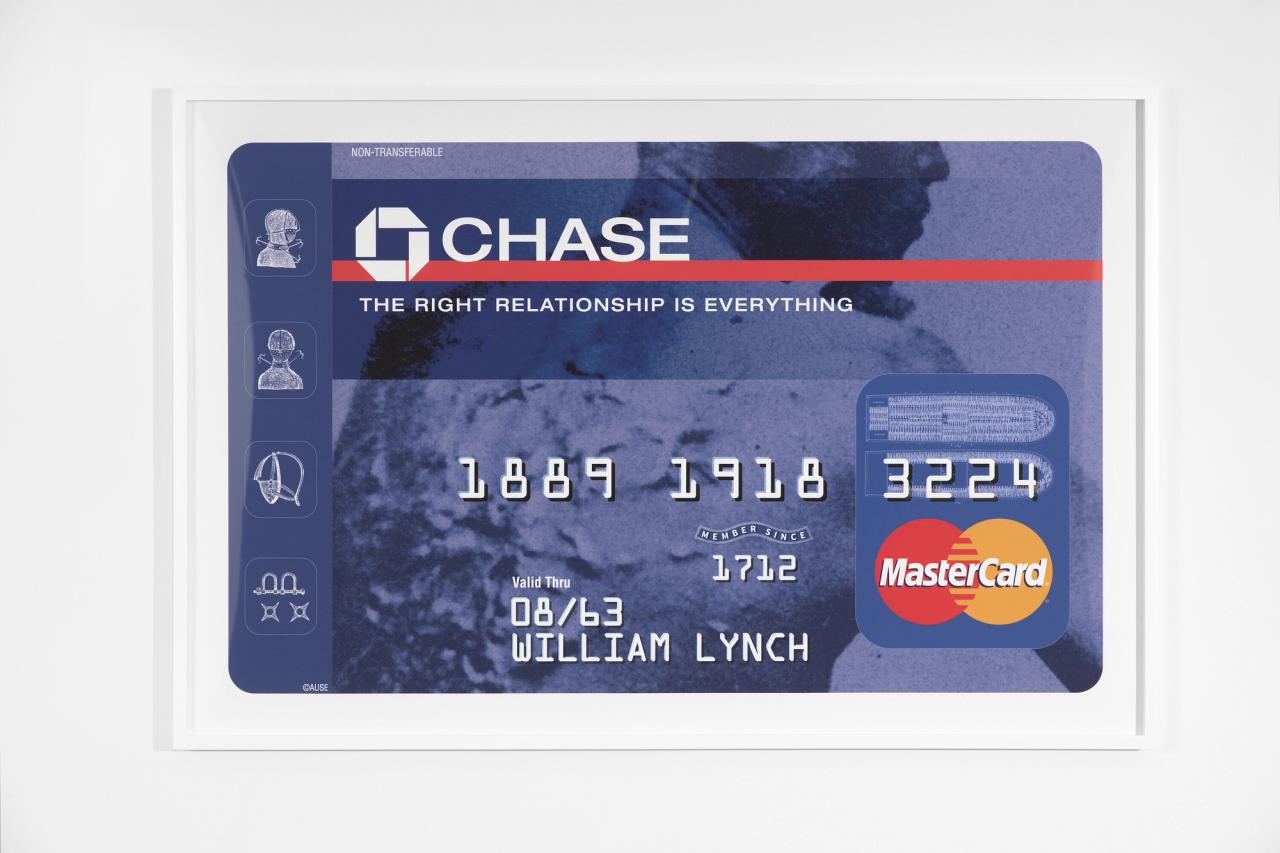

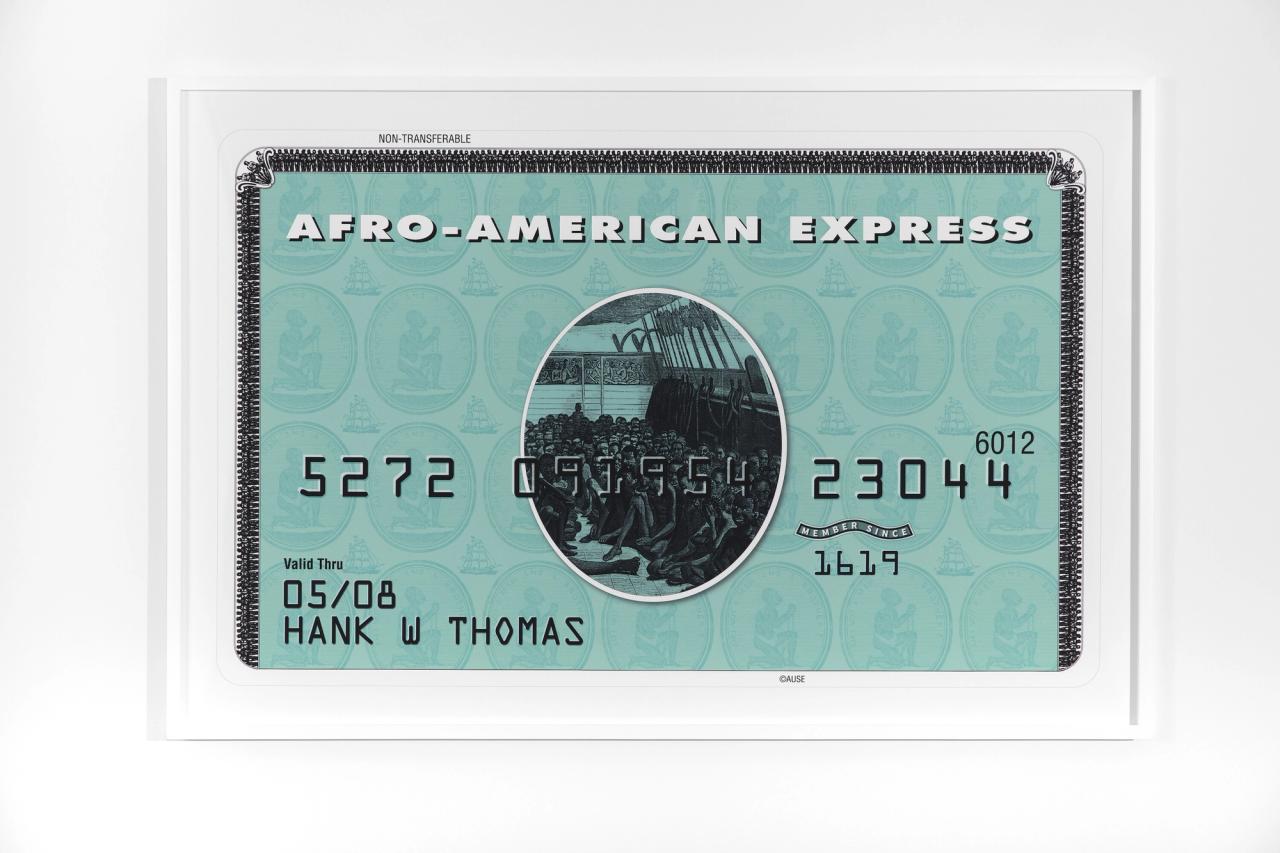

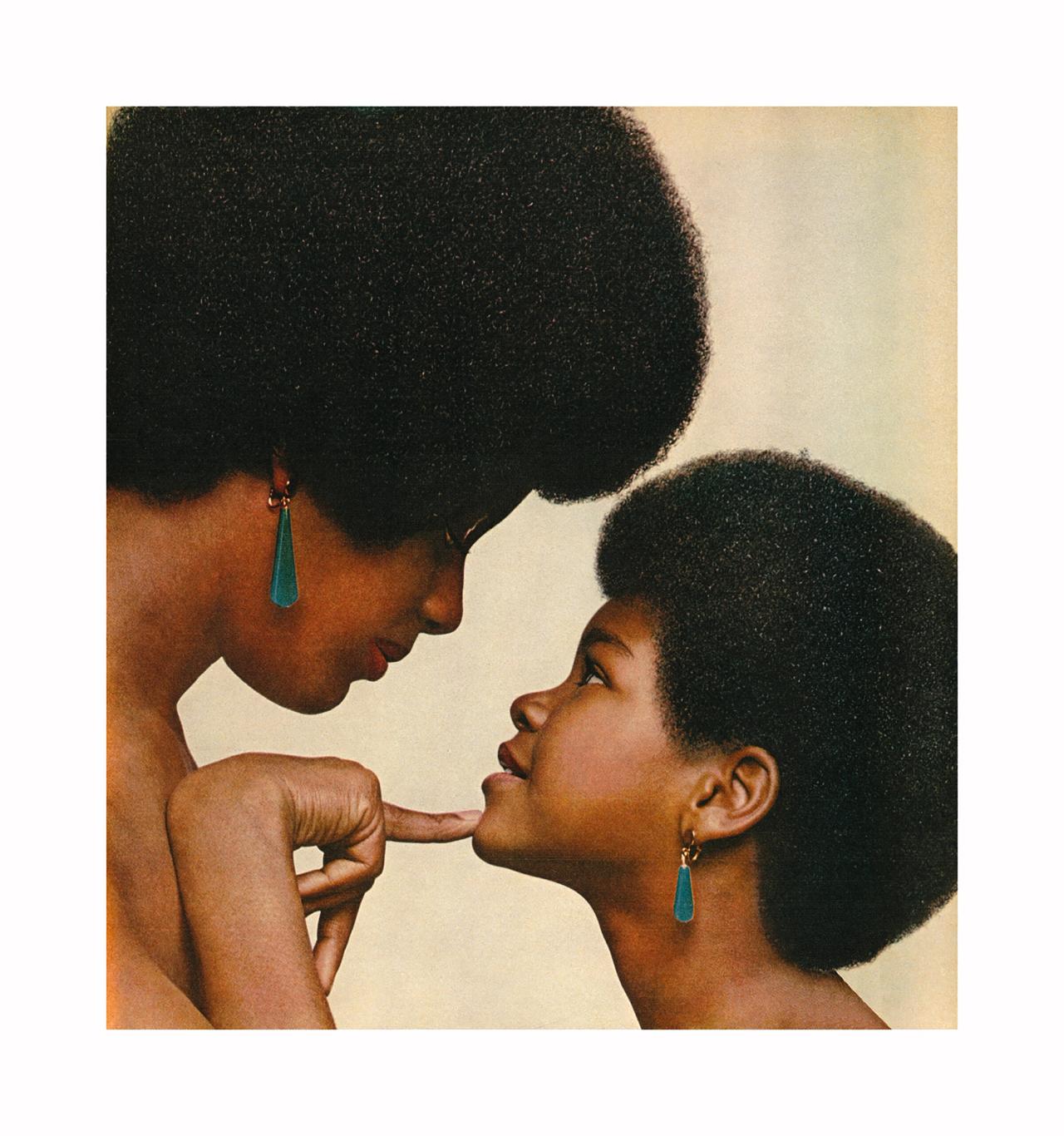

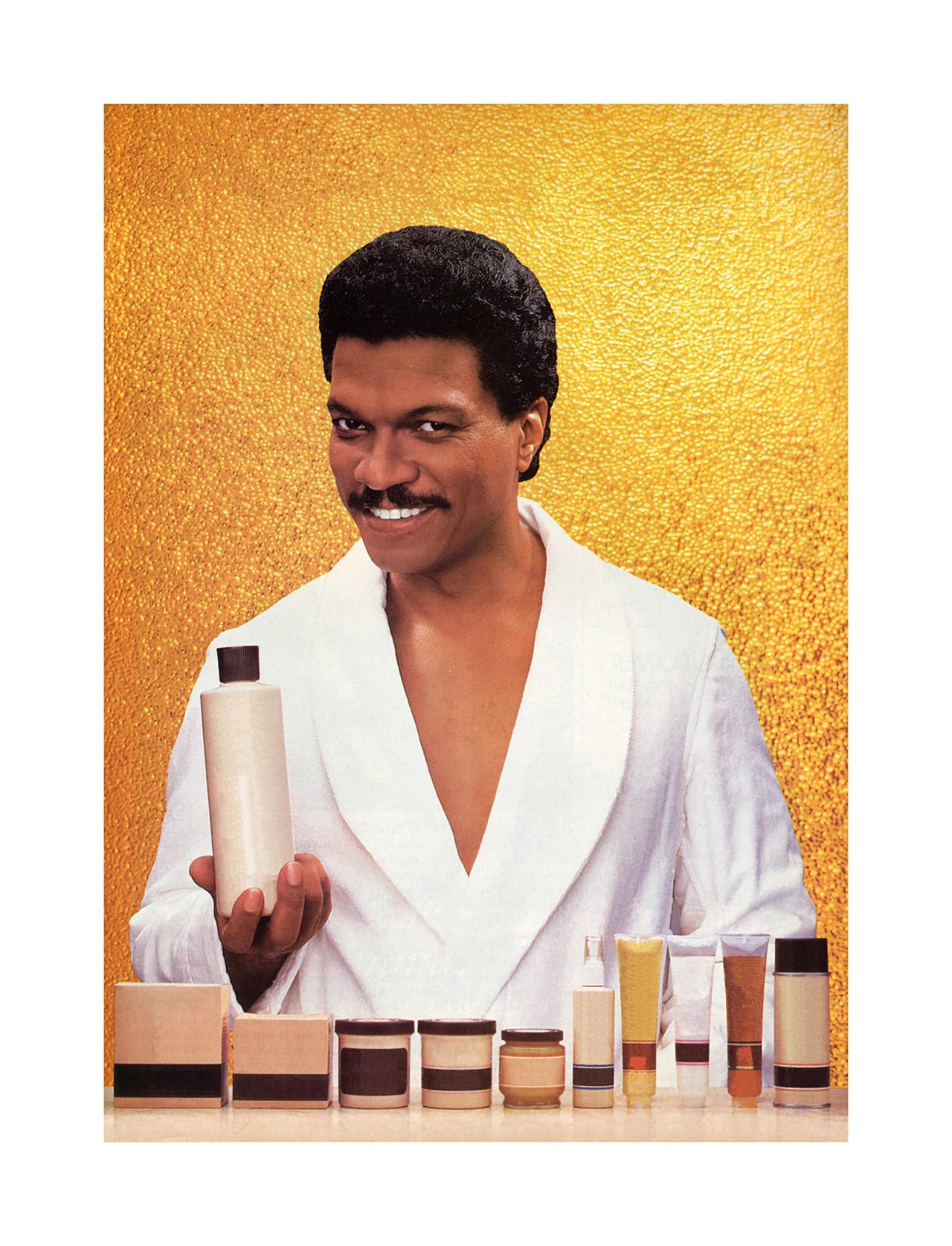

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Branded” (2006). (Courtesy the artist)

“Absolut Power” (2003) by Hank Willis Thomas. (Courtesy the artist)

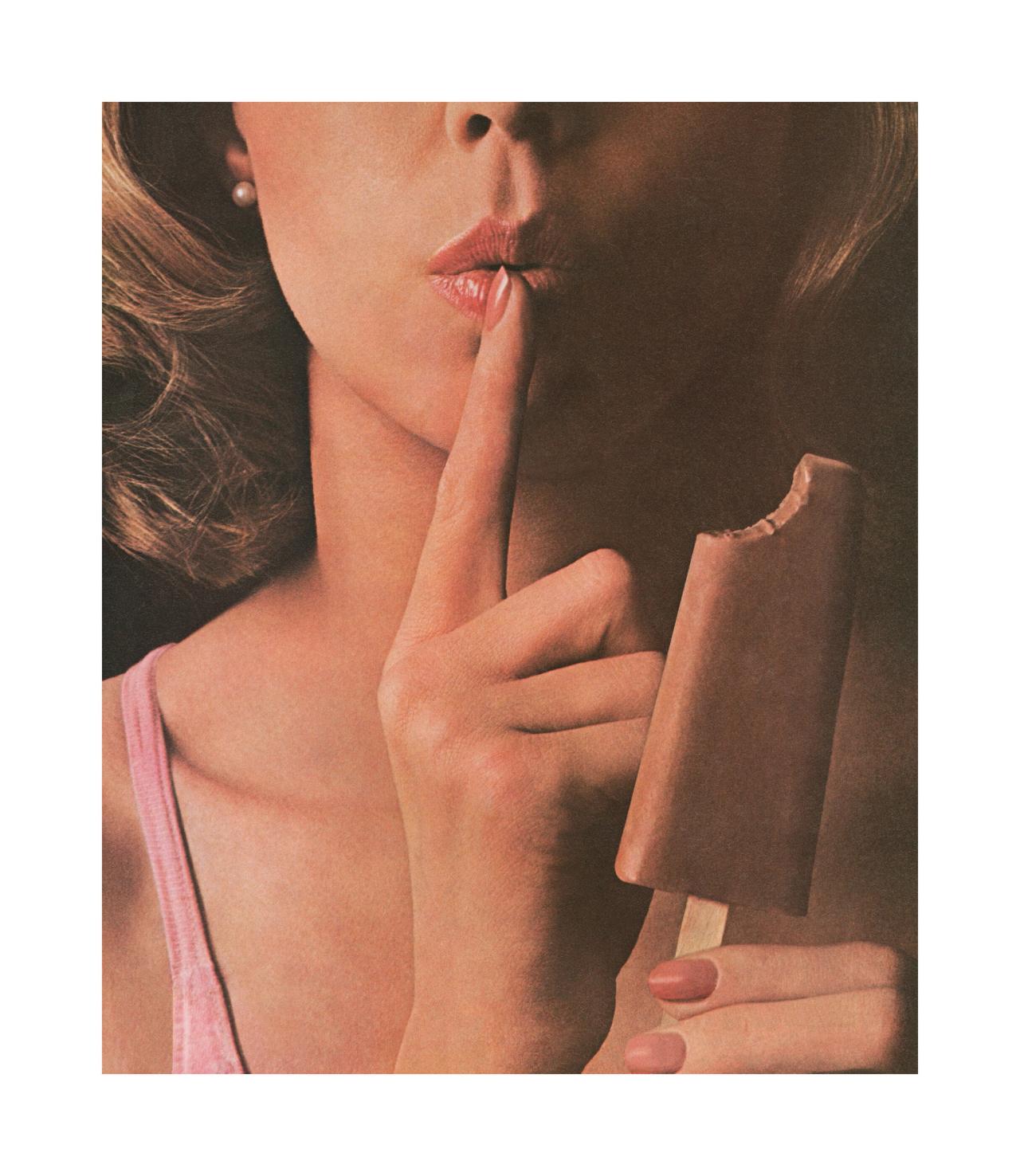

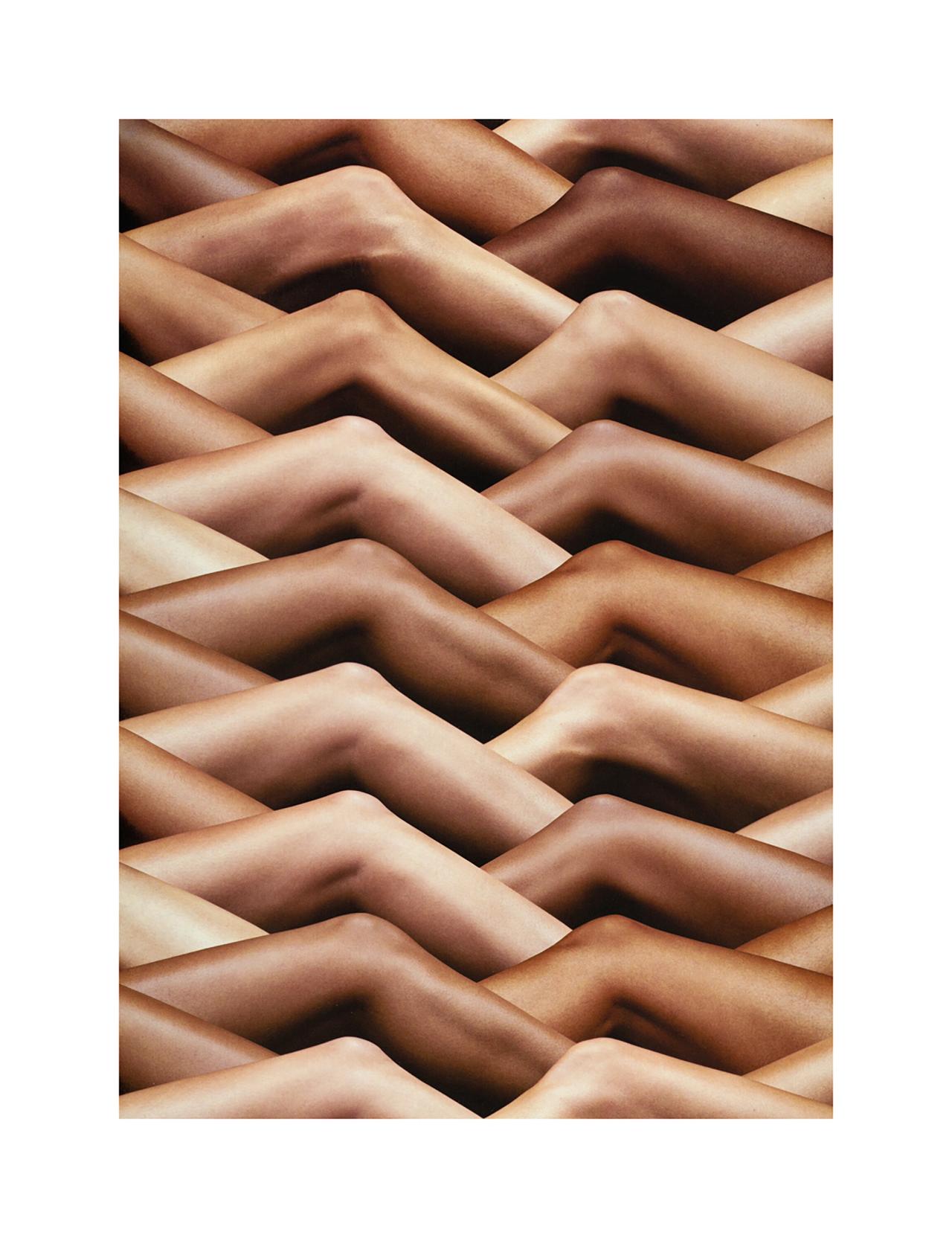

SB: Well, the Sultan connection with the Jordan campaign is interesting given so much of your early work was really focused on the language of advertising, series such as “Branded,” “Unbranded,” “Rebranded.” Could you share a little bit about what you learned about American society and culture, and its history of racism through this work? Because I mean, you have a piece from this series, “Absolut Power,” rendering of this Absolut Vodka ad that really speaks to this, I think, that retranslates, re-presents so much of the visual language that we’ve been served over the past few decades.

HT: Sure. Well, my jobs in undergrad and grad school, two of the jobs that had a huge influence on me, were working in the library, in the photo library at Tisch and in the art library at CCA. When you work in a library, you look at a lot of books [laughs], and you also look at a lot of magazines. I became pretty versed in the landscape, the visual cultural landscape, and I was really fascinated with… Something that it crystallized for me in my mom’s work, is that if we know that some young woman from north Philadelphia, out of her curiosity, can find images and tell stories about the American experience that really counter a lot of what we’ve been told, what is the value of what’s being told?

Then I realized that there is a grand narrative, a master narrative. I think Public Enemy says, or put it, “Real history isn’t history; it’s his story.” [Editor’s note: The exact lines, from “Brothers Gonna Work It Out,” are: “History shouldn’t be a mystery / Our stories real history / Not his story.”] Typically, it is his story that’s being told, and he is usually the victor. In our society, he is usually an Anglo-Saxon-descended, wealthy person. And so his story is not our story. I became interested in our story because when I looked through all of these books and all these images, I recognized that there is a much more complicated story being told, but we seem to only prioritize one. So I started to think about, like, “How can I insert myself and other voices into his story?”

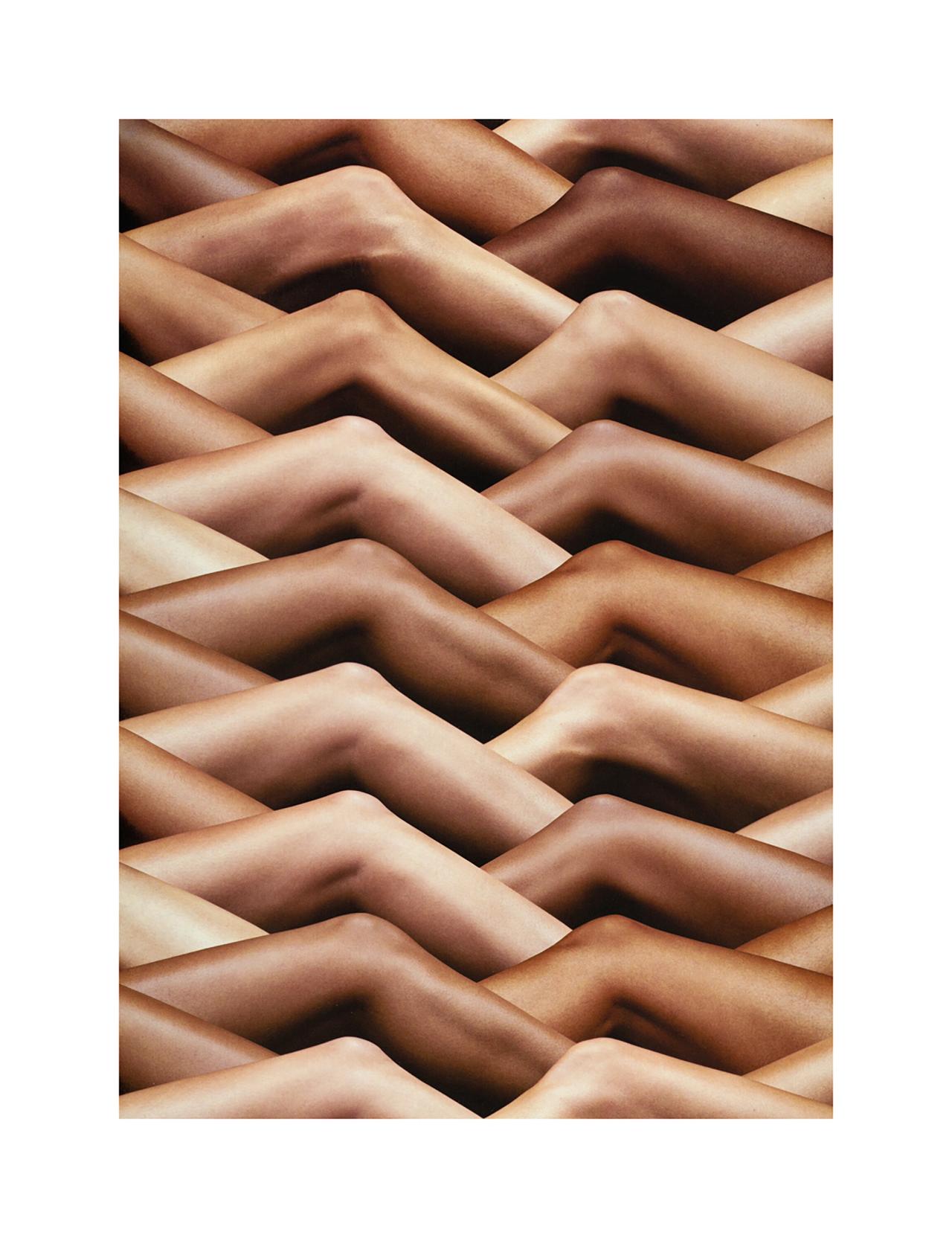

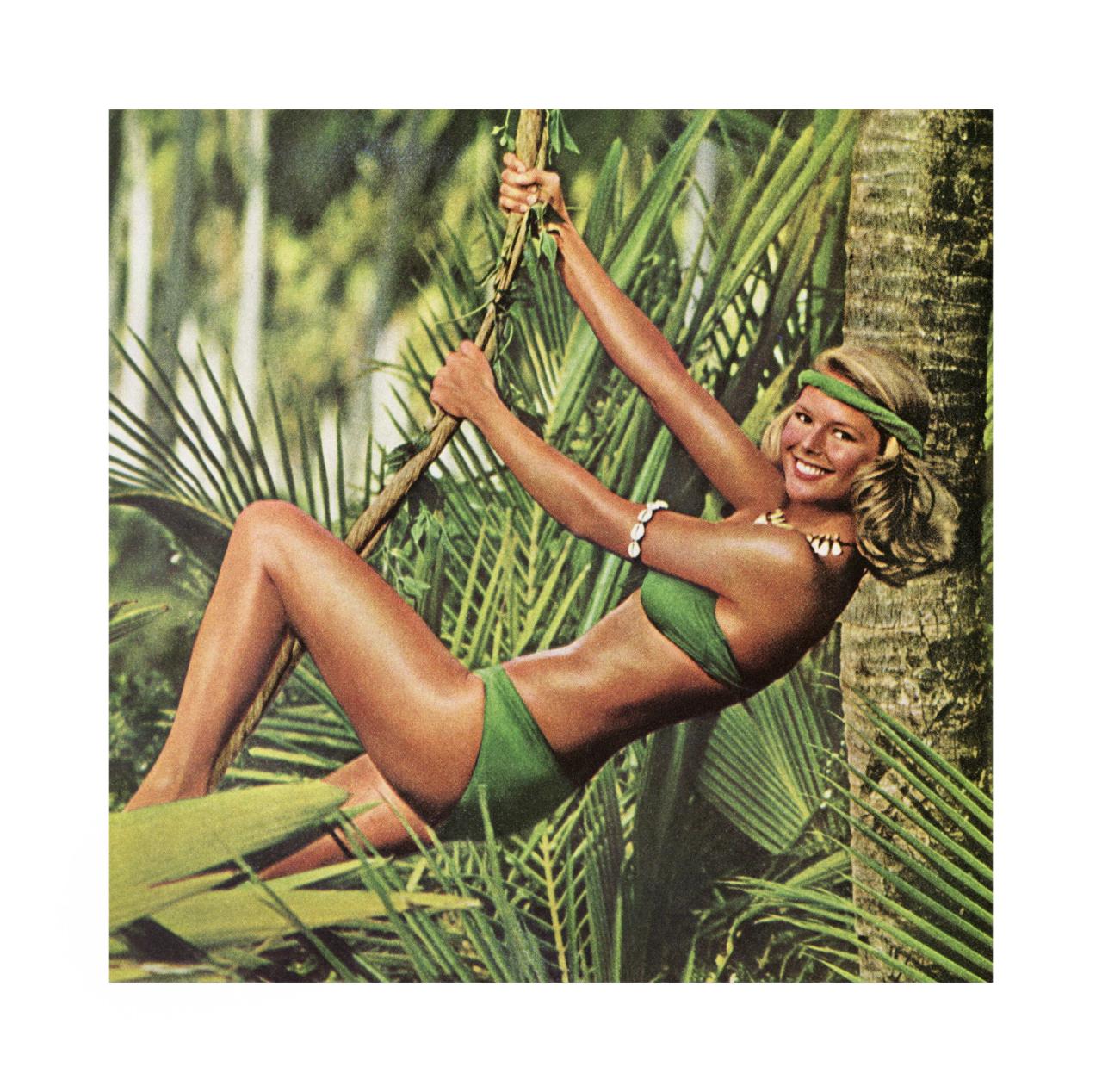

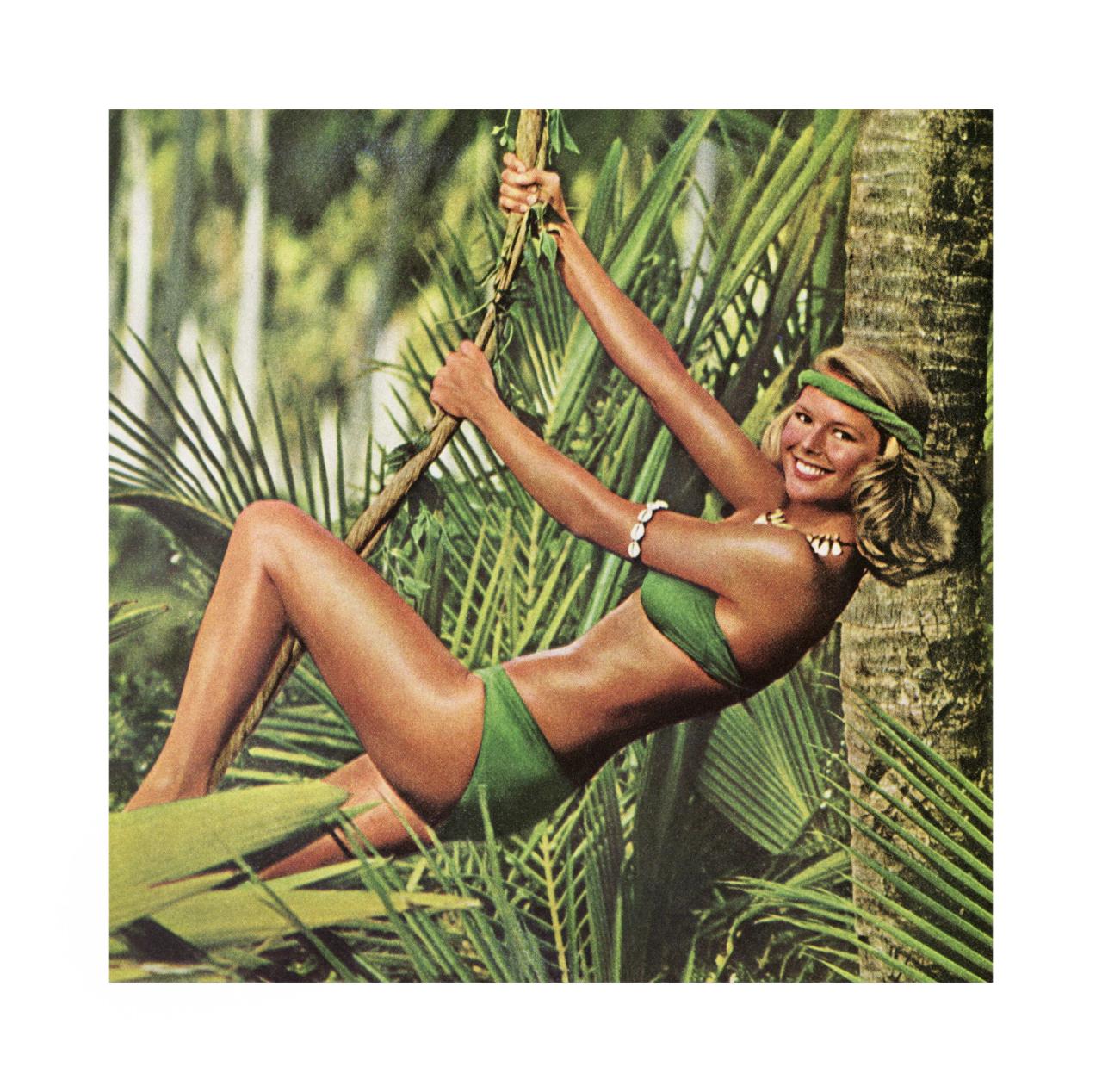

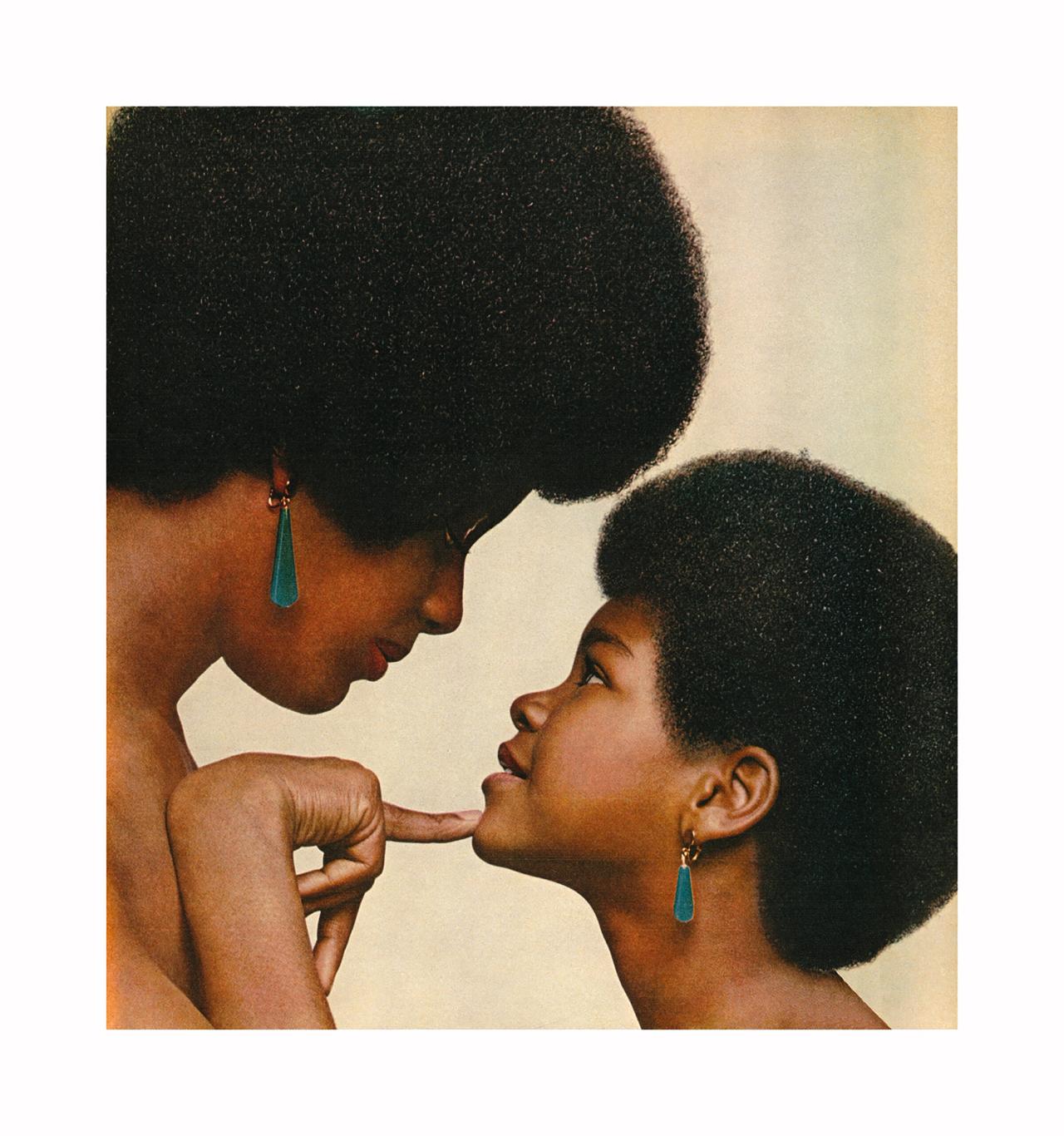

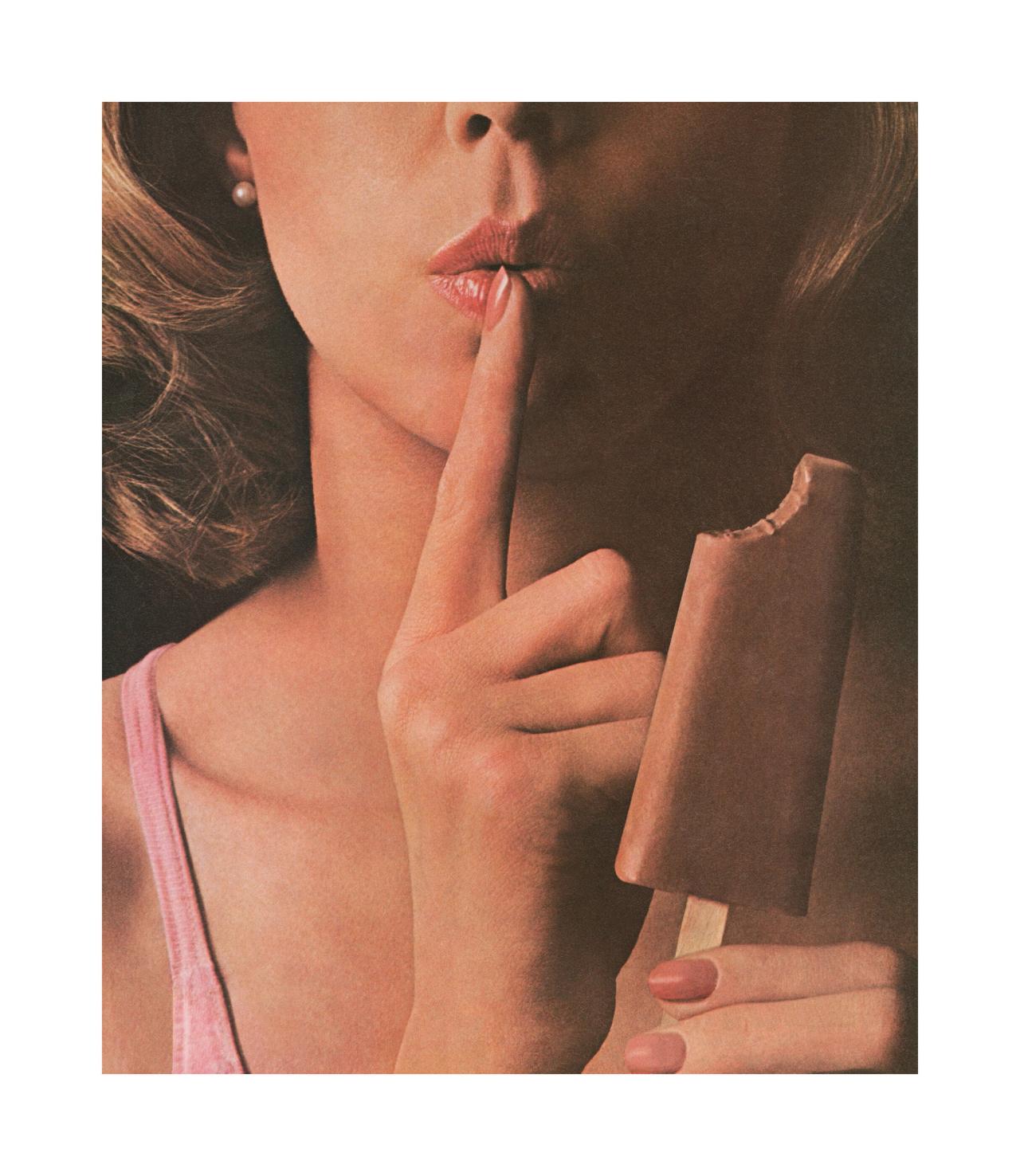

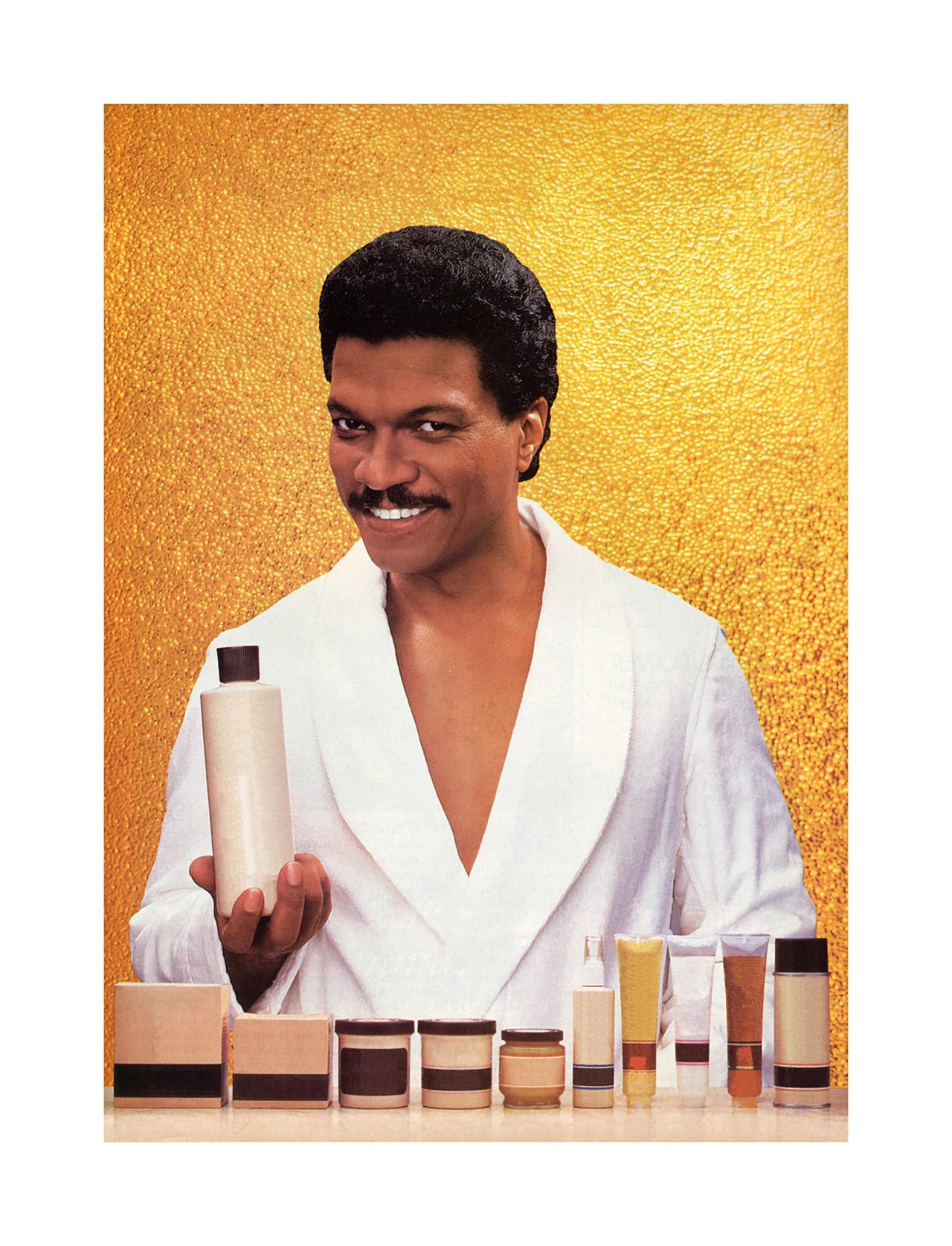

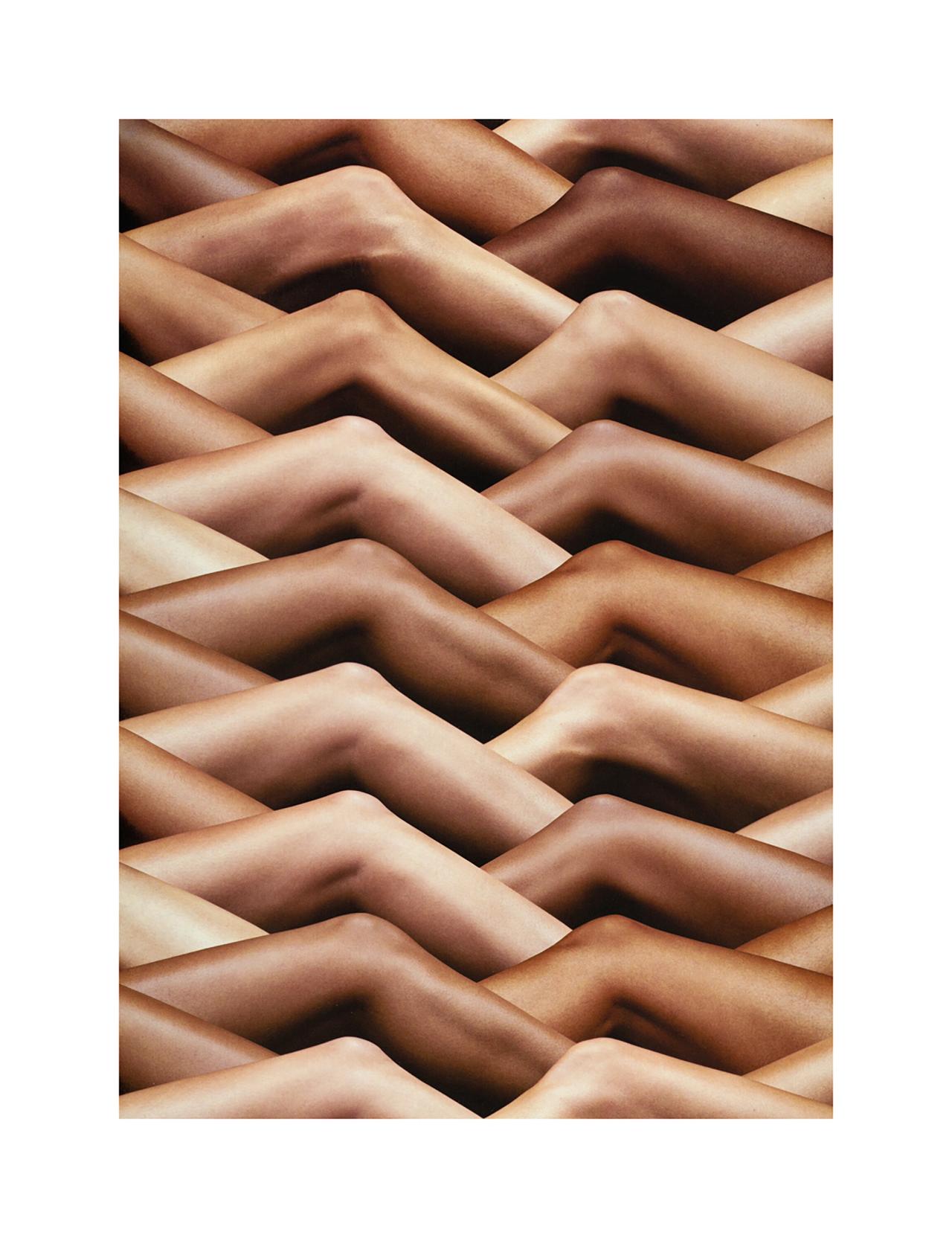

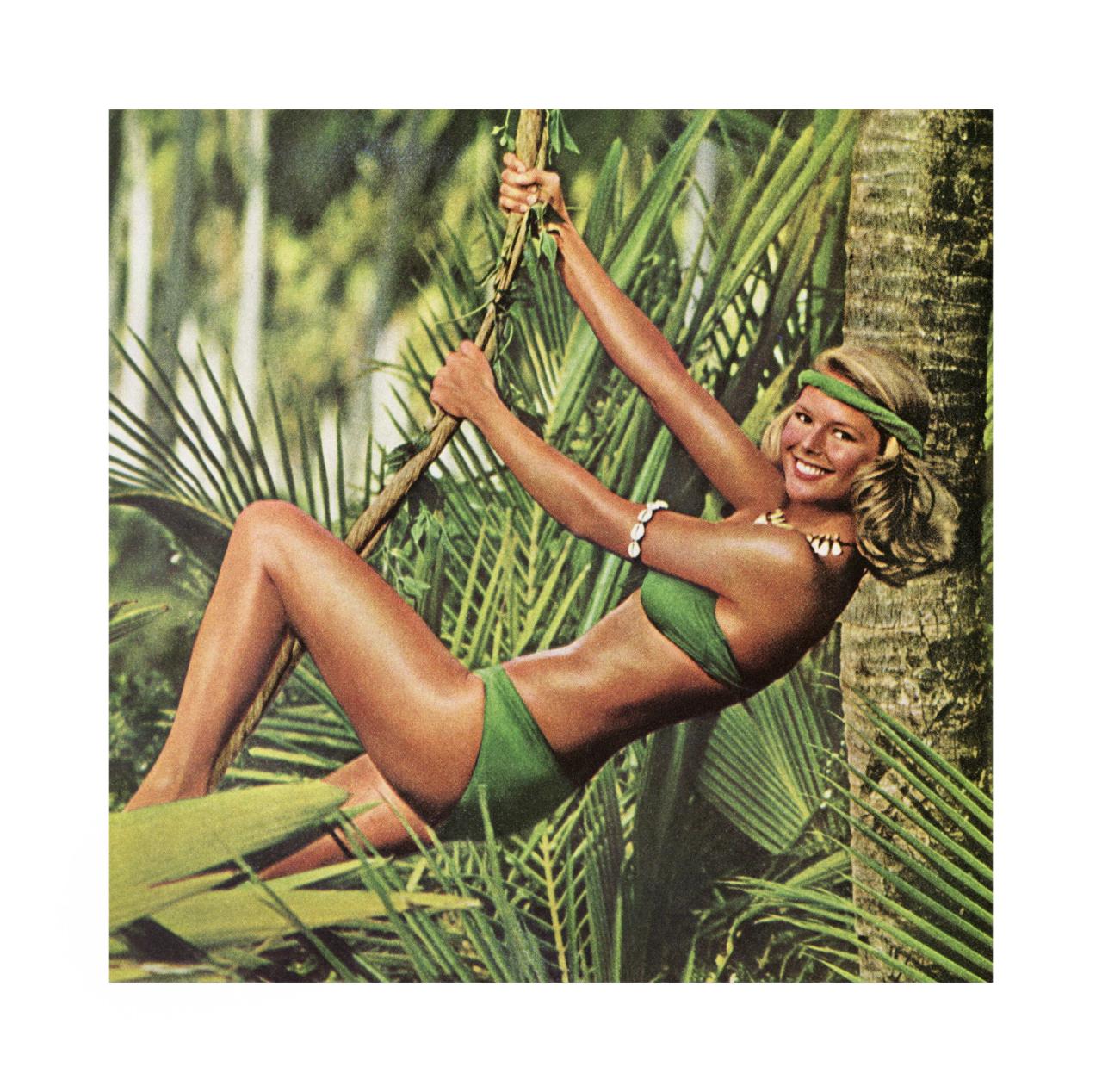

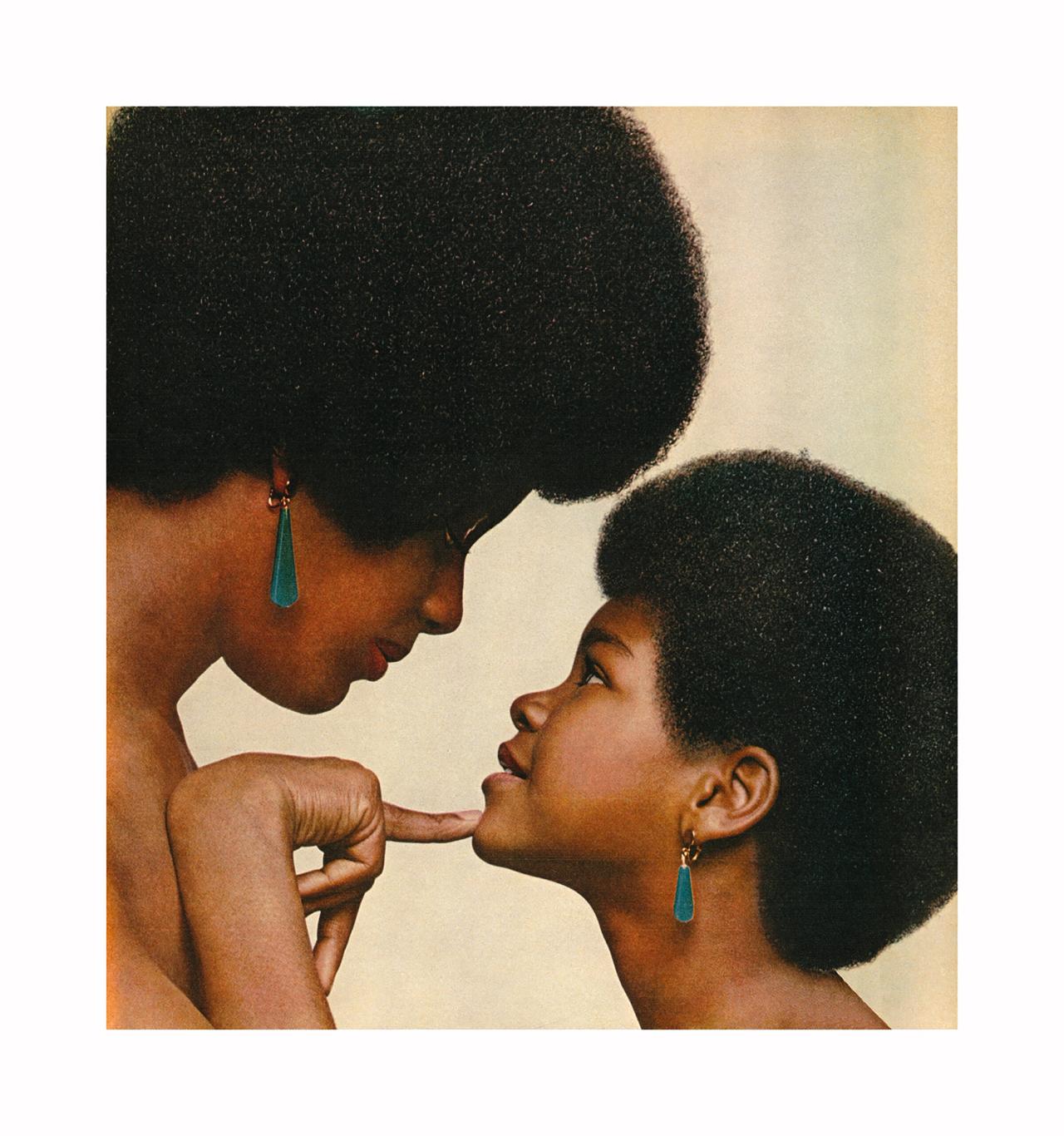

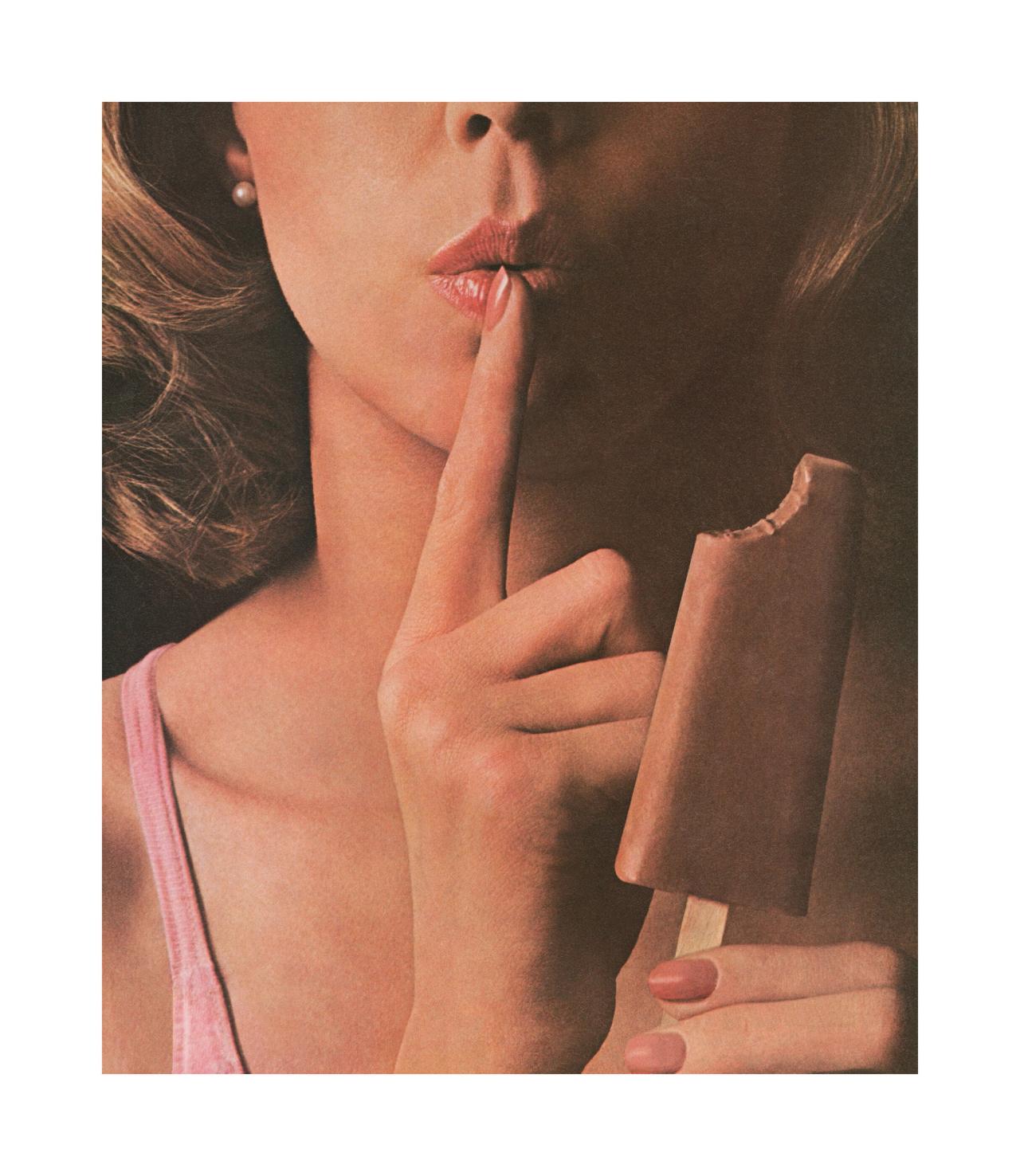

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

A work from Thomas’s series “Unbranded” (2018). (Courtesy the artist)

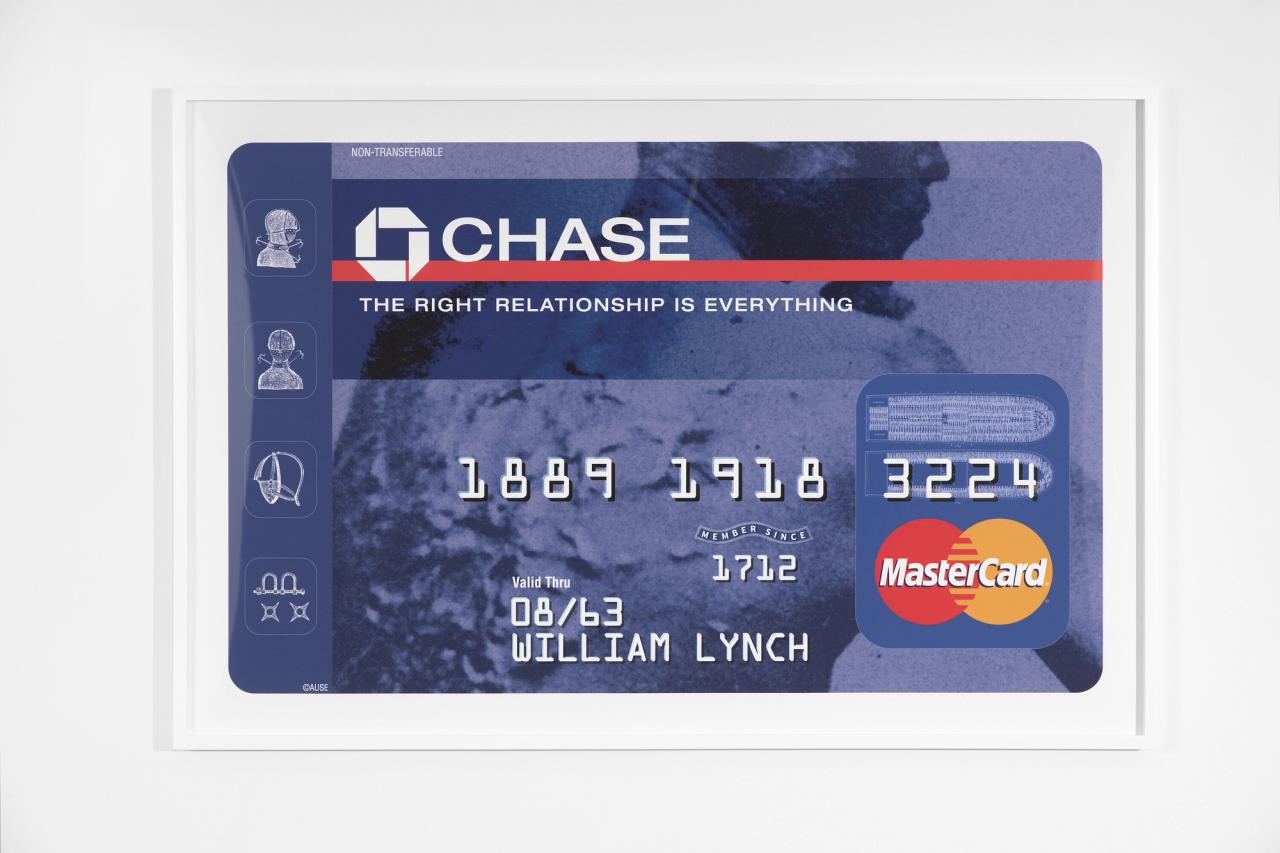

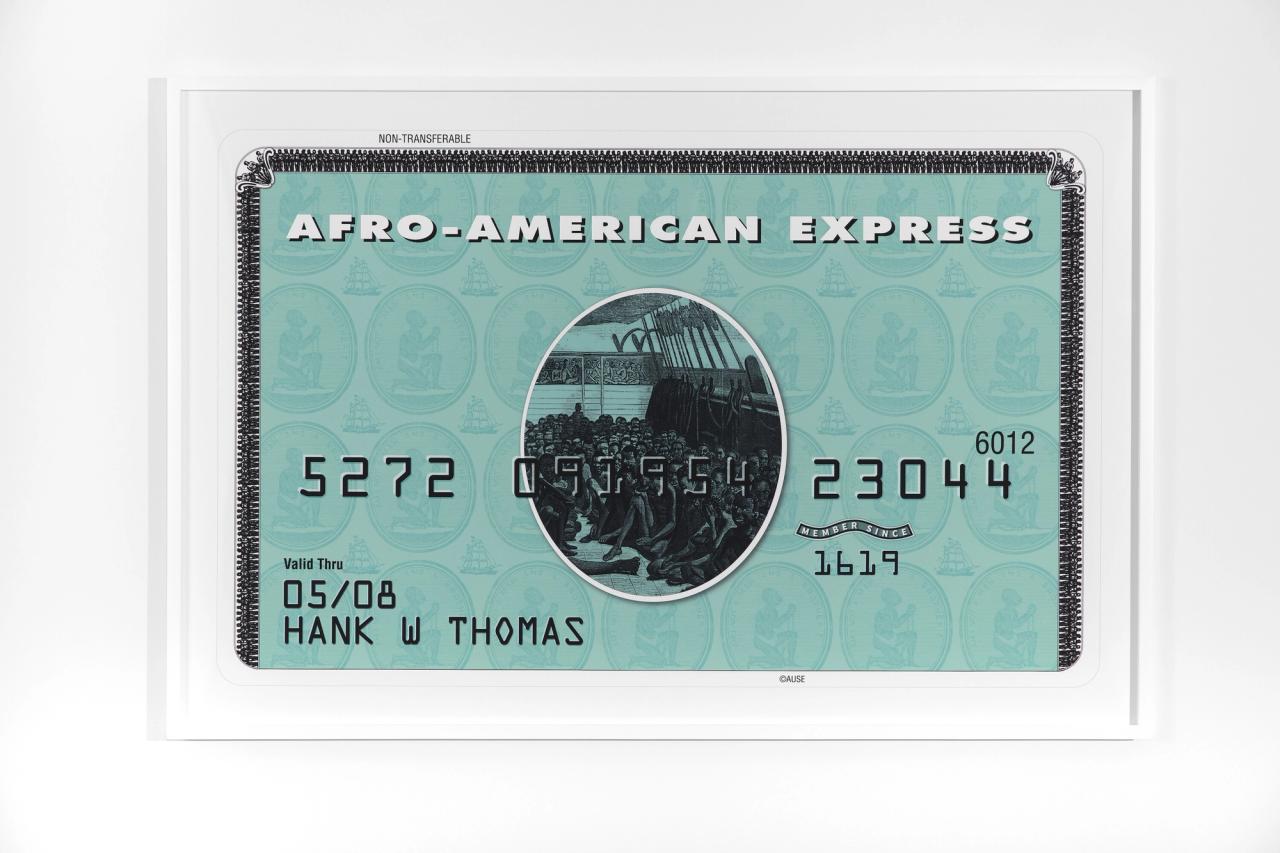

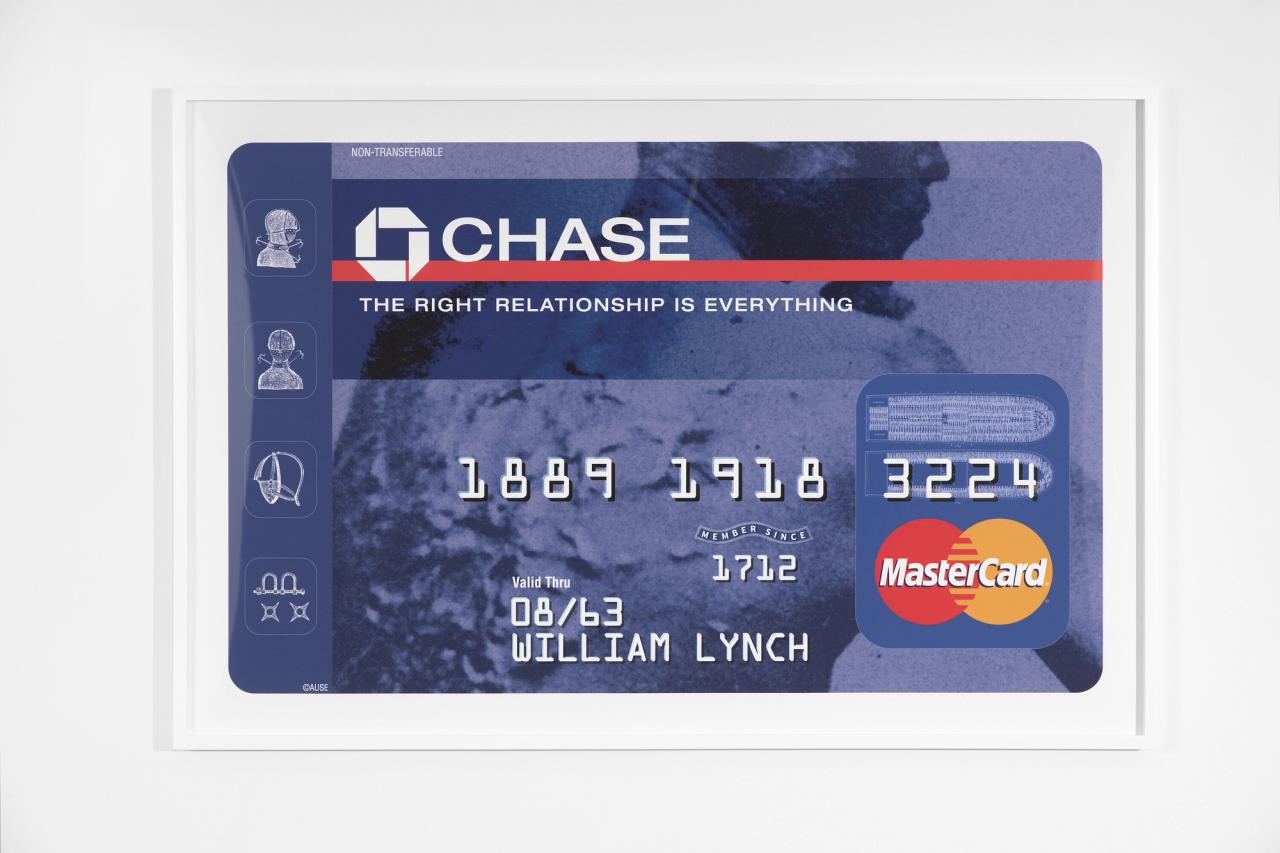

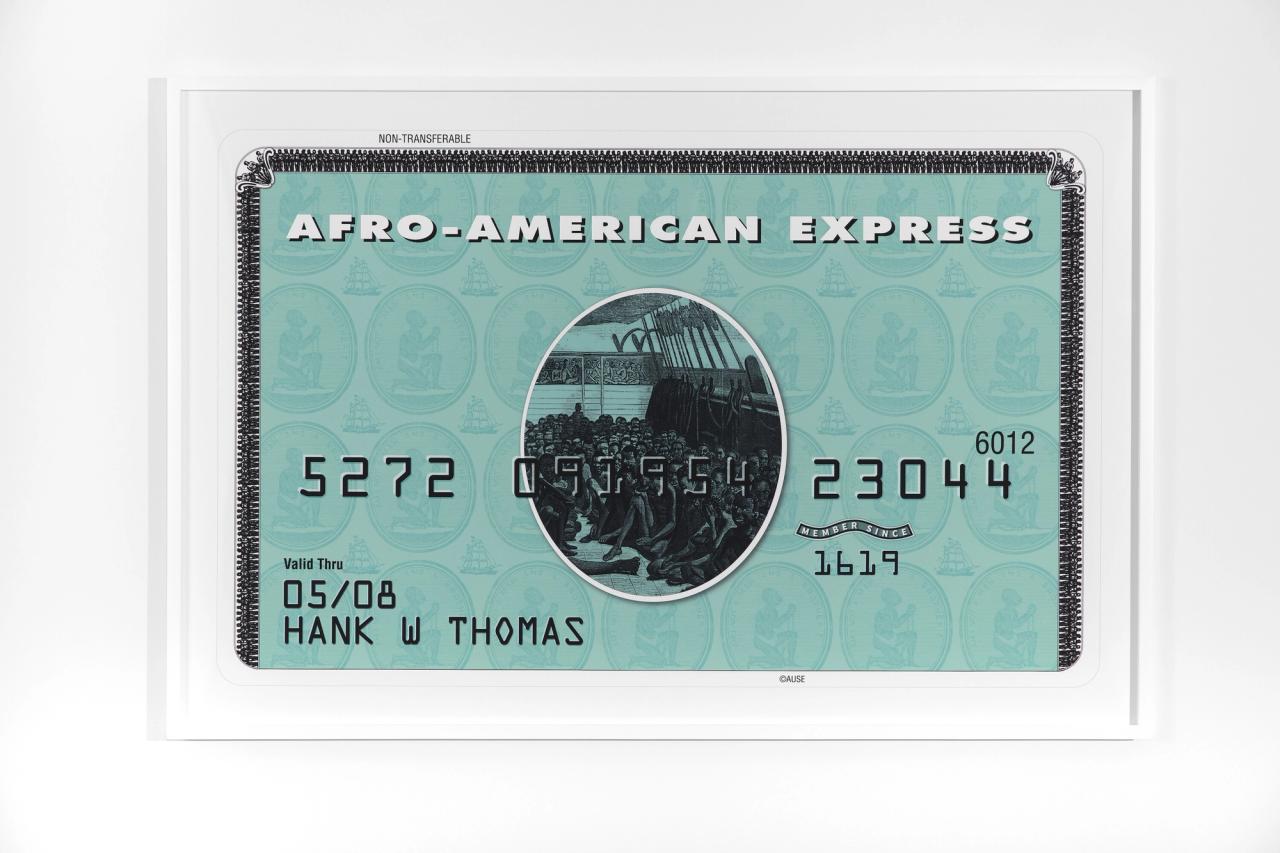

A work from Thomas’s series “Rebranded.” (Courtesy the artist)

So I looked at advertising and realized that most people who were making advertisements were, you know, if you watched the show Mad Men, upper middle class and white men. His story to his wife about what she should care about really served him. And his story to the person who cleaned his house was serving him. So I was interested in what was her story, and what was his, the other his story, and how could those combine. And so I started to use…. I realized that advertising is the most powerful language in the world because you don’t necessarily have to speak the language to be able to decode it because we’ve all become media literate and therefore conditioned to read images, to perceive things that are definitely not there objectively.

So I started to realize, “Well, how can I use that language of advertising to talk about things that advertising couldn’t responsibly talk about like slavery, like gender issues, or…” So, yeah, the “Branded” and “Unbranded” series were really looking at advertising as a tool for communicating ideas. Also, I like to point out that race is the most successful advertising campaign of all time, and whoever created it probably had a vested interest in making themselves better than others. And if only because of the absurdity of the term “Caucasian,” because most people who are defined Caucasian—

Installation view of “A Place to Call Home” (2020). (Courtesy the artist)

SB: Aren’t from the Caucasus.

HT: —aren’t from the Caucuses. And so already, we’re starting off crazy, and to say that there’s a billion people in the continent of Africa, but they’re all basically the same. Then, even the concept of Europe being a continent. What did you learn a continent was when you were in elementary school?

SB: It was just a land mass, I don’t know. [Laughs]

HT: I learned it was a land mass that was surrounded by water on all sides. Europe is just a tiny part of Asia, but the myth because the Europeans telling the story did not want to acknowledge—

SB: This makes me think. There’s this great work you did, and its name is escaping me.

HT: “Africa America [Reflection]”? “A Place to Call Home?”

SB: “A Place to Call Home.”

HT: Mm-hmm.

SB: Yeah. There’s this great work you did, “A Place to Call Home,” where you merged two continents. Could you talk about that here?

HT: Yeah. So, that’s part of what I realized, is like, “Okay. When I call myself ‘African American,’ where is that? Where is Africa America?” It’s clearly a figment of my imagination. And so I made a work where I merged the continent of Africa and the continent of North America to make a place that I could call home because I’ve been all over the continent of Africa, I’ve been all over North America, and I haven’t felt “home” in any place. That’s because it is my imagination, and that’s what I’m saying, that our identities are all a figment of our imagination, and we use these myths as a way to codify and to brutalize and romanticize others and ourselves.

Stills from Thomas’s video installation “Question Bridge: Black Males” (2012). (Courtesy the artist)

“Our identities are all a figment of our imagination, and we use these myths as a way to codify and to brutalize and romanticize others and ourselves.”

SB: Another component of your work I wanted to get into this is the participatory nature of it, and particularly through “Question Bridge” and “Truth Booth.” In many ways these are time-based works, they’re collective works. Could you share a bit about these two projects, and how did they develop? What did you learn through creating them?

HT: One of the reasons I also love collaborating with other people is that my ego is forced to find a comfortable space in a larger thing. As an artist, as an independent artist, I’m focusing on what I care about and what I think is important. But when I invite someone to collaborate with me, it’s what do we think and how do we feel about things. The more different their biography is than mine, the more complicated, the more we both get to stretch as a way to come together around something, which means that the audience also has some form of a stretch. So “Question Bridge: Black Males” was a video-mediated magalog between African American men, self-identified African American men, and my collaborators—three of whom were African American men, two of whom were not—we recorded one hundred fifty self-identified African American men asking questions of other self-identified African American men.

Stills from Thomas’s video installation “Question Bridge: Black Males” (2012). (Courtesy the artist)

The goal of the project was to show that there was as much diversity within any demographic as there was outside of it. But our premise was faulty from the beginning because we thought we would ask one, we’d take that question up, and one African American man asked, and take it to another African American, and then get the best answer, and then use that to make a piece. But what happened is we took that one question to ten different people, and we got ten different answers. There was no better answer because even though they were ten different Black men, they were really just ten different human beings responding to a question in ten different ways, which means that there are probably thirty million different ways of answering that specific question.

I realized that is the very truth, that the imaginary lines that we place around our identity, that “Question Bridge: Black Males” wasn’t just about Black men, it was about people. What happens when people are put into groups? How they relate to the notion of the group itself, and other people within the group, and how they find agency knowing all of the constraints of being marginalized in a group? That challenges the notion of the truth, and so the “Truth Booth,” which followed that, was a modern day confession booth where we invited thousands of people to go into this inflatable speech bubble and respond to the prompt, a video prompt, “The truth is…” So they would come in, and they’d record themselves saying, “The truth is…” and they would just go from there.

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Stills from Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Stills from Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Stills from Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation in Ireland. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

Thomas’s “Truth Booth” installation. (Courtesy the artist)

And many times, much like with “Question Bridge” where the viewer—in this case, me—would see a person read them and be like, “Okay, I know what kind of question they’re going to ask.” Or, “I know what kind of truth they’re going to talk about.” Or the way they start, it’s like, “Oh, they’re talking about this.” And then it goes left. All of a sudden, all of my prejudice is called into question and recognizing that my truth and their truth can exist and both be true, even if they appear to contradict itself. That’s the nature of being human beings. I’m looking at you, you’re looking at me. My truth looks very different than your truth.

SB: Yeah.

HT: The more that we can acknowledge that our lived experience is about a multitude of truths in harmony or in conflict existing, the more we can be conscious about how we navigate that reality.

SB: There’s a sort of artist-as-reporter quality to this work, too, and I did want to ask you, How do you view the connection between artmaking and journalism or reportage? Do you, in some ways, view yourself as a reporter?

“We realized, in part from watching the news, that nobody knows what the news is, so why don’t we be the news?”

HT: Well, For Freedoms, which is my most prominent current collaboration, is currently embarking on a new venture, which you’re welcome to work on it with us, called For Freedoms News [FFN]. We have operated over the past eight years as artists, as “political operative” in an anti-partisan platform that we created. Now, we realized, in part because watching the news, that nobody knows what the news is, so why don’t we be the news? And so, we are now operating or performing as journalists because the legitimacy of being called “the news” is something that we believe is creative. Journalism, again, is rooted in a very…. Well, we cannot detach the forms of journalism that we now have from the history of imperialism and colonialism. If you learn about popular journalism going back at least until the mid… Well, we can talk about the pamphlets as a form of journalism in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, which were both a combination of propaganda and the news, which morphed into different news forms. But thinking about people like Henry Morton Stanley who became famous for his exploits into Africa where he found his famous statement, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” where people learned about, through The New York Times and The [New York] Herald, about Africa through these salacious stories that this journalist would write. Right?

Thomas (right) with his parents. (Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas)

SB: “Africa” in quotes. “Journalist” in quotes.

HT: Yeah. This is the “dark continent.”

SB: Yeah.

HT: You can’t detach that history from what’s happening now. The reason that I believe Donald Trump became president was because he understood that the news was just what you could get people to talk about. So he could say, “Mexico is sending rapists,” and then the news would say, “He is opposed to immigration,” which is not what he said. He said, “Mexico is sending rapists.” And all of a sudden, this issue that was maybe an issue that was relevant is now the central issue. Then, he could just say, “Okay. We’re going to ban Muslims,” and then that becomes a thing. And this reality that—

SB: “China virus.”

HT: Yeah, the China virus, but where it’s like… because he saw what happened in 2003 with Iraq, and it was super critical of it that the news was interested in shock and awe, and weapons of mass destruction.

SB: Even the sounds they make when they’re cutting between news broadcasts.

HT: [Doosh, doosh, doosh] Well, that’s the other thing. If you now look at CNN, a lot of times, it will be like, “So and so slammed so and so,” or even NPR, “So and so rips so and so.” I’m like, “Is this the WWE?” Like, that’s what we’re calling journalism? Because it’s always been a revenue-based model or subscription.

SB: I just saw a tech publication [The Information] write about S.B.F. [Sam Bankman-Fried] as like a contagion, and I was like, “This is insane.”

HT: Yeah. The more that you can get anxiety, and fear.

SB: Well, I think it can’t be understated, the importance also of having Columbia Journalism School’s first Black dean, Jelani Cobb, at the helm, at this crucial, critical moment in how we define truth, how we think about journalism.

HT: Mm-hmm.

SB: It’s really important.

“I do see myself as a journalist, and I see myself as a historian, I see myself as a political figure. I also just see myself as a mass of organisms that are just struggling to survive, and maybe using ego as a means of nutrition.”

HT: Right, and he was not seen as a central voice ten years ago. Right? That tells you how elusive and elastic the medium of journalism is, and so why—artists, we specialize…. What I like to say is, “Good art asks questions, and good design answers them.” And the quality of the questions dictates the quality of the answers. If you don’t have people asking good questions in the form of artmaking, then how can you have great answers? So that’s why I do see myself as a journalist, and I see myself as a historian, I see myself as a political figure. I also just see myself as a mass of organisms that are just struggling to survive, and maybe using ego as a means of nutrition.

SB: Before we finish, I want to continue just briefly on For Freedoms, which started as this first artist-run super PAC. You co-founded it. We just got through the 2022 midterm elections in which this widely anticipated or reported red wave didn’t happen, and I was wondering, how are you feeling about the election, and what are your thoughts looking toward 2024?

HT: I gotta go back to Public Enemy: “Don’t believe the hype.” Be the hype. We were not the first artist-run super PAC. We just said we were.

SB: [Laughs]

HT: And then somebody, a journalist, wrote about it. Then another journalist fact-checked that, and guess what? We were the first artist-run super PAC. [Laughs] That’s how I view the news. Right? So when the news is like… First, it’s like, “Oh, well, the Republicans aren’t going to do particularly well these midterms.” Then, it’s like, “Ah, there’s going to be a massive red wave!” And then, “Oh my god, who’s going to make it? Is this going to be the person? Is this going to be the person?” “Let’s give a lot of… We know that giving airtime definitely gives people credibility, so why don’t we just give Herschel Walker a lot of airtime?” “Oh my god, the news is getting close. The race is getting close. Oh my gosh, what is going to happen?”

It’s like, “Okay…” I mean, it’s entertainment. We can be cynical about the fact that somebodys are making billions of dollars off of keeping us engaged in the “news,” or we can say, “These are narratives that we can actually claim for ourselves.” And that, like, “The Democrats winning, is that going to save the day?” I love my parents, and [President] Joe Biden seems like a relatively decent human being, but—he’s 80. I’m not saying that somebody who’s 20 or 40 has any more power or awareness of what’s happening now, but if the fate of humanity lives in people who are looking at the other side of life, then that should say a lot about what’s going on. Meaning that, like, why are the people most invested in the direction of humanity, the people who’ve been living the longest?

So, I don’t know. Also, if the Democrats, who tend to have the majority of people in the country in agreement with them, tend to have a slightly better grasp on the truth, tend to be more decent in their behavior, and civil, are struggling to beat people who are flying by the seat of their pants, lying, avowed greedy, selfish people [laughs] who are also self-righteous and hypocritical—like outwardly, not even secretively. They’re like, “I just said this yesterday. No,. I didn’t say that.” And often, xenophobic, and racist, and sexist, and homophobic, even if that includes themselves. If they can’t beat them, how are they going to affect global warming? It should not be close, “Hey, I’m a pathological liar. You have been doing this for forty years and people think that you’re a really honest, genuine person. Let’s duke it out.” [Laughs]

SB: Yeah.

HT: The pathological liar almost wins?

SB: Election deniers.

HT: I mean, I love it because I realize that it’s all about storytelling. If I can tell a good story, then I can get people to do whatever I want. And that’s, as a creator, who again, I’m an artist, so I can ask a lot of good questions, but you guys are storytellers. Also, I’d like to point out that lawmakers are designers. Storytellers are designers, but lawmakers are also designers. The laws that are written for our society, that’s social design.

SB: They shape [culture and society]. Yeah.

HT: The fact that they are devout, non-creative people designing our society, and we got very creative people like you, sitting in rooms like this, with very creative people like me, talking shit while they’re designing our society, says that we are not doing what we’re supposed to be doing. It’s cozy, it’s nice in here, but we should be in a dark room with no windows plotting on how we’re going to rule the world.

SB: [Laughs] Well, I want to end this conversation on quilts.

HT: Did I go overboard just then?

“Guernica” (2016) by Hank Willis Thomas, on view at the Portland Art Museum. (Courtesy the artist)

SB: No, this will connect. Throughout your work, you’ve created a wide range of quilts, stitching together prison uniforms, sports team jerseys—“Guernica” from 2016 really comes to mind here; incredible piece you did. A quilt motif will even appear in the labyrinthian granite plaza beneath the King Memorial in Boston.

HT: Mm-hmm.

SB: Maybe it’s an obvious metaphor, but I did want to use it as a way to end because when looking at your work as a whole as a quilt, there’s this profound idea of referencing the past through selective materials. It also gets at this idea of the archive, how it’s always present, that there’s this constant presence of the past. It kind of connects to Saidiya Hartman’s notion of “temporal entanglement.” How do you think about quilts and quilting in your work, and I guess perhaps metaphorically too within the context of your career?

“I’m constantly weaving disparate things together. Stitching is most of what I do conceptually.”

HT: Well, I’m constantly weaving disparate things together. Stitching is most of what I do conceptually, and I really got into the making of quilts through—my mother made quilts for a long time with my aunts, and my grandmother made quilts. My mother made all these quilts of her father’s ties after he died, and it was called “Daddy’s Ties.” She made photographs with those ties. That was really powerful because for her, my grandfather, every day he went to work, he’d put on a tie. Part of being a man in that moment was the way in which you carried yourself. You dressed like a man. Not like us. [Laughs] So these memories that were in this fabric for my mother about her father, and also, the fact that this is the fabric that he wore around his neck for, you know, thirty, forty years.

SB: It’s a memorial.

HT: Yeah, it’s a memorial. It’s a commemoration. Yeah. There’s intimacy in that. And so when I think about sports jerseys, where I’m putting on something that has someone else’s name on it, where I’m asking other people to recall moments of inspiration that this person had for me. Or, prison uniforms, where these are people who are anonymous, and that their life and labor that’s lived in these materials is seen as something that should be discarded. What happens when those become material for representation of images or stories? It’s sticky, it’s complex, and it’s, I guess, that’s what you call art.

SB: Hank, thank you so much. It was really great, as always, to sit down with you.

HT: Thanks so much. It’s really fun to talk to you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on November 17, 2022. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity by Jennifer Grant. The episode was produced by Emily Jiang, Ramon Broza, and Johnny Simon.