Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Ramdane Touhami

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Ramdane. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

RAMDANE TOUHAMI: Yeah, cool. Hello.

SB: I should begin by stating up front that The New York Times has written that Ramdane “speaks so quickly that he can leave his listeners downright dizzy.” We’ll see if that happens today.

RT: No, no, no, no. I don’t think so. Maybe, who knows? Depends on the subject.

SB: [Laughs] First question, and I feel like this is where an interview with you related to time should start, because your many projects are so detail-driven and also rigorously rooted in history: What’s your approach to thinking about time and temporality when it comes to the work that you do?

RT: I think time is the most important thing for everything. People forget that. When you hire someone, basically you buy time from someone. You say, “How much are you going to sell me every hour of your life?” That is something people forget. You buy time from people; they sell time. When you buy something very expensive, the brands are trying to make sure that they spend a lot of time creating it…. They crafted it. It took them a lot of time to do it. Basically, we’re living in a world where we trade time, but no one calls it like that.

SB: Let’s talk about the—I think I’m pronouncing it right—Drei Berge?

RT: Ahh, Drei Berge.

SB: Drei Berge, the hotel that you opened in Mürren, Switzerland [in 2023]. How did this project come about?

RT: I have just a problem. I don’t use my brain. It’s creating problems.

SB: [Laughs]

RT: I hate holidays, I love mountains.

SB: [Laughs]

“I hate holidays. I love mountains.”

RT: I always said to my wife, “When we’re going to have a little bit of money, I’m going to buy a place in the mountains, but I want to work there.” The best thing was a hotel. One day a friend of mine called me from this place in one of the most beautiful valleys, because for the last twenty-five years, I did valley by valley and all the Alps, almost all of them. I discovered that the most beautiful is this one. After reading a book of this anarchist geographer called Élisée Reclus, who did La Commune de Paris, the revolution. He was the biggest geographer of the late 19th century, and I read the book, and he said, “I didn’t like the mountains until I went to this valley.”

A view from a guest room at Hotel Drei Berge. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

I remember reading this book and thinking, Oh, what is this valley? I went there and you have these three mountains, which means “the drei berge” [in German]. You have the Jungfrau, the Mönch, and the Eiger, which are the most beautiful mountains in the Alps. Of course, you have the Matterhorn, “the Cervin” in French…. You have a few nice mountains, Monte Rosa. You have also in Italy a few beautiful ones, but these ones together, there’s nowhere in the Alps you can see the most beautiful like that. They’re all more than four thousand [meters above sea level], except the Eiger’s three thousand nine hundred and forty-five or something like that.

Big mountains always in front of you. Magic view. People know very well Wengen or other cities around, but Mürren, it’s a little hidden gem on the top of the mountain. You cannot access it with a car. You have to take a gondola. I went there and I fell in love directly and a guy said, “There’s this hotel for sale.” As I said, my brain doesn’t work always. I said, “Okay, I’ll buy it.” I didn’t check. It’s very stupid. We found out after we had a lot of problems, but I took it and I said to my team, “We’re going to redesign it. Refabricing a wall and we have two months to make it new.” Changed the name. The name was…. What was the name?

SB: Bellevue.

RT: Bellevue. It was a very dumb name, like the place where you put the old people, this hospital. One movie was shot in the sixties, seventies, early seventies called The [Eiger] Sanction. I bought it and I revamped it and here we are.

SB: This place was first opened in 1907, and your revamp does manage to keep a bunch of the original details.

RT: Yeah, yeah.

“The culture in America is very different. You like to redo. It’s part of the capitalist system. In Europe, we love to keep.”

SB: How did you decide what to add and what to leave? How does that work in your mind?

RT: Actually, it’s not 1907. That’s what we wrote, but we just found out it was 1894, actually.

SB: Oh.

RT: It’s much older than expected. It had a name, which was beautiful. It was the Hotel of the Star, in the beginning. We started when the name became Bellevue, but we found out it was earlier. The culture in America is very different. You like to redo. It’s part of the capitalist system. You like to erase, remake, erase. In Europe, we love to keep. When you arrive basically, automatically with your eyes you know what you’re going to keep. I changed a few things. I changed the color. I changed, of course, all the furniture. I changed the beds. I changed all the bedrooms. They were terrible. I mean, it was like cow prints everywhere—a caricature of Switzerland.

SB: [Laughs]

Exterior view of Hotel Drei Berge. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

RT: It was a family, owned by this couple who were, like, from the canton of Uri. Super deep, deep Swiss people. Very, very, very, very racist—that I found out after…. It was Swiss and it was cheap! You can have this old bed from the 19th century and an Ikea thing next to it. We erase. I have to redesign everything. Because we moved with my wife and the kids from house to house, I have a huge collection of furniture. I’m a big, big collector between Italian ’48, 1980, and now I have from all the movement—[Angelo] Mangiarotti, [Tobia] Scarpa…

“All my life is a huge improvisation, and it’s going to be like this to the end.”

SB: I read you have a lot of Dieter Rams.

RT: Yeah, I have a whole collection. I didn’t put any Dieter Rams in this hotel, but I have a JBL 4350 in the lobby. I brought all that and I made, actually, my dream chalet. One very funny story: At that time, a friend of mine was buying these bedsheets, a company called Beltrami in Italy. I called him, I said, “I’m looking for bedsheets for my hotel. You know a guy?” He said, “Yeah, you go there.”

I end up buying a part of this company with him. They do the most beautiful bedsheets in the world, much better than Frette. In this little hotel, we have the bedsheets of The Ritz. It’s how I do things. Very— I told you, I don’t think so much. I improvise. All my life is a huge improvisation, and it’s going to be like this to the end—to the end!

SB: I noticed that the Financial Times, when writing about the hotel’s look and feel, turned your name into an adjective: “Touhamified.”

RT: What? [Laughs] How do I call it? I didn’t even notice—

SB: They took your last name and turned it into an adjective.

A public area at Hotel Drei Berge. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

RT: Touhamified. I’m going to tell you one thing. I have a particular idea as a designer. I work for a lot of brands, a lot, a lot of brands. People don’t know, because I don’t allow the brand to say I did it. I’m maybe one of the only designers on the planet who can sue a brand because they, in the press, said, “He did it.” It happened lately: We sue the brand. I will not say the name of the brand; I don’t want to do an advertising on them again. This company calls me and I “Touhamified,” like you said, the company in one year. The company went from forty-five million turnover to ninety. They were so happy! When the press asked them what happened, they said, “Ramdane did it.”

I said, “No, you’re not allowed. This is your brand. This is not my brand. Me, I’m your doctor. I fix you. When your doctor fixes you, you’re not in the street screaming the name of your doctor, ‘He fixed me,’ all day long, man. I’m happy you paid me for that, but I don’t want to be the star of the thing.” The star is the brand, it’s not me. Also, I don’t want my name to be hurt because maybe at the moment we did a good job. What they’re going to do with the work I’ve done in the future, I don’t know. I don’t run the company. I don’t want my name to be mixed up with things like that.

It’s very strange. I know my friend, they do a tiny thing in the brand and they put it on social media. “I did that! I did that! I did that!” It’s very interesting. We are the opposite, voilà. Because I like to keep my name fresh. When I do Drei Berge, the press are happy to talk about it. We didn’t call them twenty times in the same month to say, “Ramdane did that! He did that! He did that! He did that!” Your name is something you have to use carefully.

SB: What, to you, makes a truly great hotel?

“Your name is something you have to use carefully.”

RT: A great hotel, super simple and super complex. Let’s use the word a friend of mine uses: simplexity. It’s very simple and complex at the same time. It’s a combination of wows. I do that for all my businesses. You open the door, wow. You see from outside, wow. The car will pick you up at the train station, wow. The guy, how he dresses up, wow. The music in the car, wow. The smell in the car, wow. Oh, la, la, my God. How polite he is, wow. You open the door, wow. Everything is wow.

You arrive at the counter. How you do the chicken, wow. You see the lobby, wow. All the music, wow. The coffee you drink, wow. You go to the room, wow. You sleep, wow. All day long you’re thinking about your bed. Wow, wow, wow. It’s wow, wow, wow, wow, wow, wow, wow, wow! You go back home, you took so many pictures. You don’t have to do PR. Your client will do it. You have to convert people like a religion. Business is a religion. Religion is a cult that did well. That’s it, and—

SB: It’s actually funny you say that because I always talk about how the word “company” means com pane, like, “with bread.”

RT: Yeah.

Touhami (right) participating in a traditional ceremony during his travels. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: It’s literally based on religion and breaking bread and sitting at the table.

RT: Totally that. I mean, a catalog is a fucking bible.

SB: [Laughs]

RT: It’s what I’m saying. The store is the church. It’s very simple! They did the pattern. I’m sure many people tried religion two, three thousand years ago, but a few of them, like branding, were not doing well. It’s branding from back in the day. The one who’s remained is the one who created a good atmosphere, a good book—a good catalog—good churches, a mosque, temples, churches, cathedral.

Cathedral is like, mmm! This is the big store. This is the big one. We have the small one, the tiny one, the church, and we have the big one, cathedral, man! Bring the best designer! Ouais! It’s exactly that. The dress, the uniform, Christianity killed it, I mean, nailed it. [Laughter] It’s very simple to check it out and the brand, look at that. Oh, it’s interesting. Hmm. Maybe we do the same. Every religion, they want you to never forget them. Brands do the same thing right now. “Hello, we exist! Hello, social media, we exist!”

SB: How do you think about time when it comes to hotels? How do you use time in the hotel sense?

RT: Oh, we are lucky we’re in the mountains. We don’t see our clients a lot. They wake up, they have breakfast, they go to ski. They wake up, they go to hike, whatever. We don’t see them a lot. We’re not a beach hotel. Beach hotels are pretty complex. The guy goes to the beach, sometimes they stay by the pool. You have to entertain them.

An aerial view of the town of Mürren, Switzerland, where Hotel Drei Berge is located. (Photo: Chensiyuan)

We have to talk about the size of my hotel. It’s twenty rooms. In twenty rooms, we created our own radio, for example, which is crazy for the size of the hotel. We created also our own channel of selection of mountain movies. Really, you can spend five hours a day for a week just watching crazy movies about mountains and documentaries where we did a selection.

SB: [Laughs]

RT: We did a lot of things like that. Now, when you’re in the mountains, we don’t have a problem of…. I mean, we have lunch, dinners. A hotel is like your house. You’re just here to sleep and eat. That’s it. People don’t really spend time. Maybe you do, because I see your house is pretty comfortable—

SB: [Laughs]

RT: —but to people who work like you, writing things and think, but the people who don’t think and write things, they’re at the office. They are somewhere else. They actually put all their money on the spot they really do nothing in. It’s very, very serious. It’s like their house is storage. For ninety percent of people, house is just a place you leave your stuff and you live outside and you [come back to] sleep.

“If you want to have a hotel, make it like your house, because you’re going to welcome people like yourself.”

SB: You mentioned the only transport there is this cable car. There’s an electric train, I guess, too, but…. From a time perspective, that’s pretty interesting, too—the journey being a part of the experience of getting there.

RT: It’s the most exotic place in Europe. Coming from Paris, London, in four hours you’re in a different world. Tolkien wrote all his books there.

SB: In this town?

RT: In Mürren, Tolkien used to write books.

SB: Wow.

RT: All his childhood was there in the holidays. You are far from everywhere. The path for the hike is protected by UNESCO as the most wide path of the Alps. You are far from everywhere. Me, I wanted something very close to my house, like three, four hours including train, and even five hours from Paris, and by car six hours. In a random place like, “Wow,” and I wanted that, this feeling of— I want people to take the gondola, to see, really to go far from their normal life, normal habits.

Exterior of a store for Touhami’s outdoor-clothing brand, A Young Hiker. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

You arrive in this bubble of a hotel, where you can have Mos Def music and this view on this mountain. It’s very crazy. The music is very random. It’s the things I like. My iPhone is really my selection. You’re in my world. We did the smell I like of the mountains. We did a lot of things. It’s really my world. Don’t try to do a hotel that doesn’t look like you. It’s not good because you’re going to hate it. Do the things you like. If you want to have a hotel, do your house because you’re going to welcome people like yourself.

SB: I wanted to bring that up, because as an outgrowth of this hotel, you’re developing this line of outdoor clothing—like, seven hundred pieces, I read.

RT: Yeah. My jacket, my pants, and my shoes right now are prototypes—

SB: Okay. [Laughs]

RT: And the glasses as well.

SB: Do you view it as, beyond just being a place for people to come stay, it’s this ethos, a way of being, almost—if I can say this—a lifestyle?

“I’m going to Wyoming tomorrow night because I need to go to see a mountain.”

RT: Yeah. I don’t like the word, but yes. We are doing a Drei Berge Café now in Paris, and the magazine, Useless Fighters, our own mountain magazine. We are doing a lot of things around mountains. Mountains are my passion since I’m 8 years old.

SB: Where do you think that comes from?

RT: It may be DNA. I have no idea. I’m the only one in my family who has this passion; I’m obsessive about mountains. I’m here in New York, and I’m going to Wyoming tomorrow night because I need to go to see a mountain.

SB: [Laughs] You need to go to see a mountain.

RT: Yeah, this is it. I have this…. It’s like meeting friends. “Oh you, I never see you. Wow, I love you, you look great.” I did the Fitz Roy, Toubkal in Morocco. Everything, like Kilimanjaro. I went to see Sikkim last year to see one mountain in the Himalayas, but we had leeches attack, so we had to stop in the middle. It was the leech season. They came up, they take all your blood, like, “Oh, that was not good.”

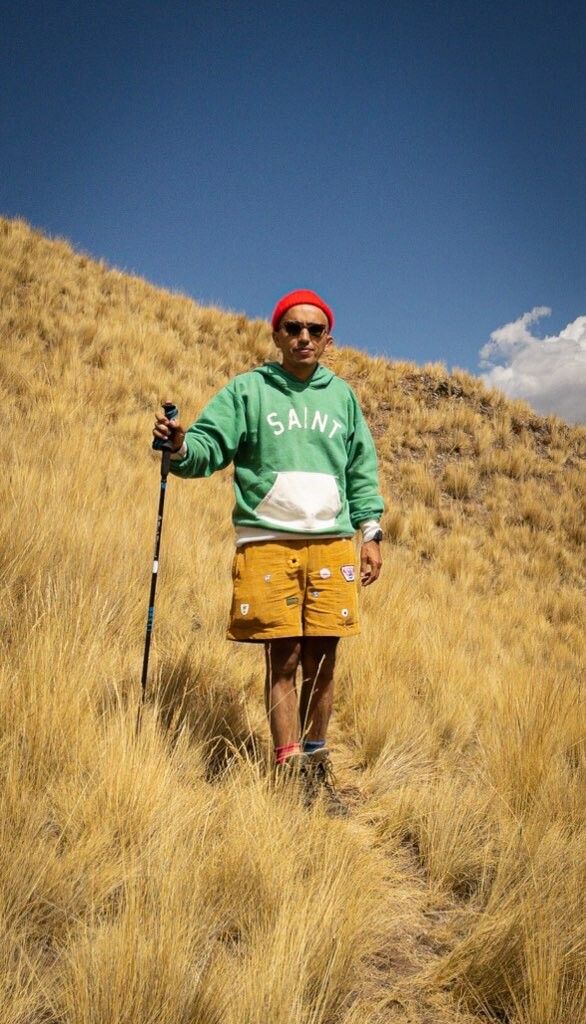

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Touhami during his many travels to mountainous regions. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

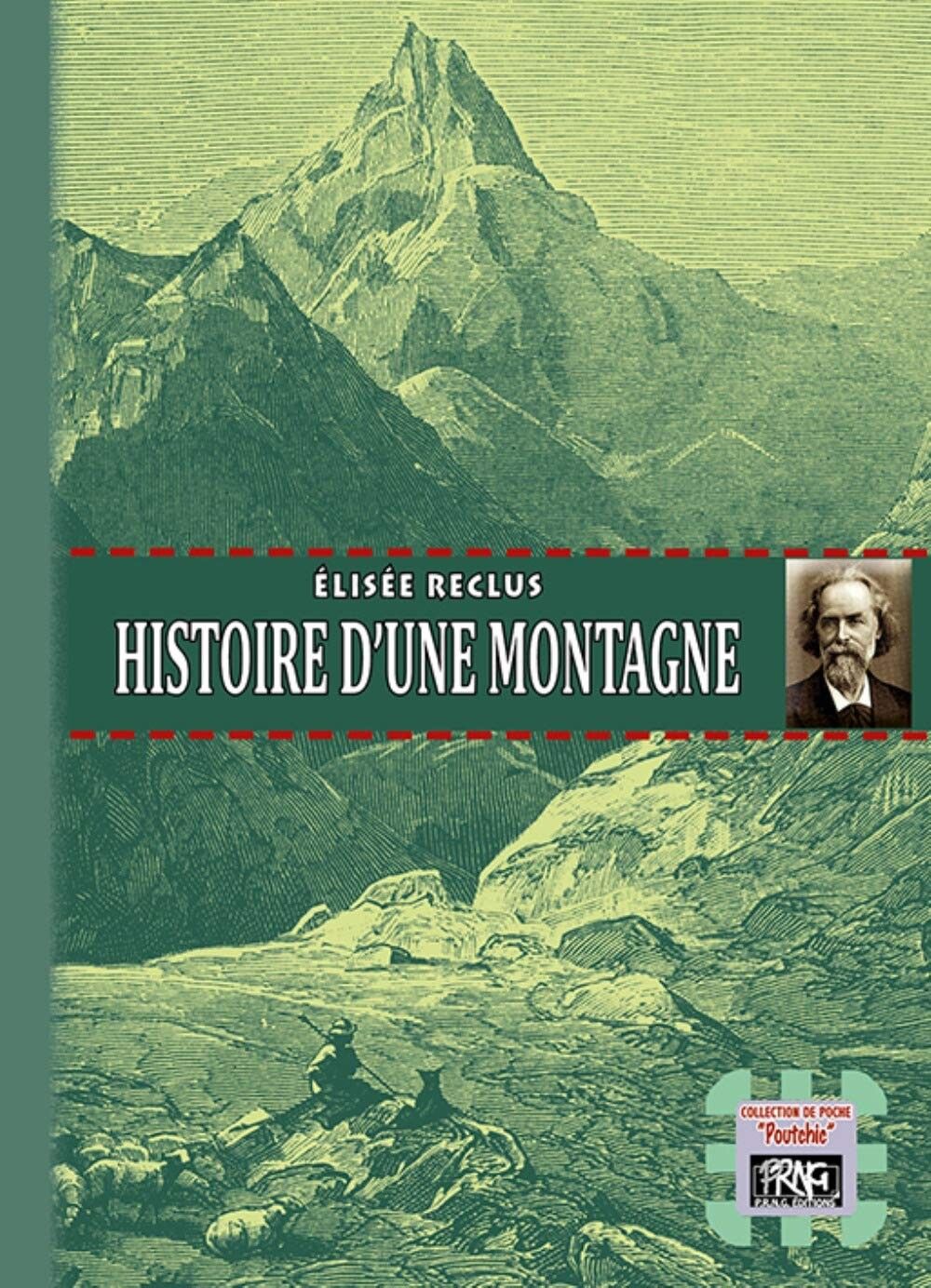

Cover of Histoire d’une montagne (1875) by Élisée Reclus. (Courtesy PRNG)

SB: There’s been a lot written about “mountain time,” you know? This idea of “mountain time.”

RT: Yeah, [Henry David] Thoreau wrote a lot about it, but also Élisée Reclus. I’m a big fan of—it’s called Histoire d’une montagne, “Story of a Mountain.” Histoire d’un ruisseau, he did also for a river, and—

SB: Even in Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time—he’s this Italian physicist—he writes about how time is different up in the mountains than it is by the sea.

RT: True, and it’s very strange. I don’t like the sea because I get bored. In the mountains, I’m never bored. The weather changes in one minute. The light changes nonstop. Mountains move…. It’s very funny. Sometimes they’re closer, sometimes they’re further. I call my magazine Useless Fighters. It’s like when you go up in the mountains, super risky. You take risks, stupid, useless. It’s like a fight that is useless. You’re just at the top. You’re happy.

Nothing else, but this happiness is very special. You feel you did something. You’re breathing good air, water is good. The sun on your skin is amazing. It’s very different, the sun on your skin in the mountains and, I don’t know, you feel closer to the sky. Oh, you feel much better, much better. If you stay one week more than fifteen hundred meters high, you have more oxygen in your blood. You come back, you have so much energy for the next three weeks. It heals a lot of things.

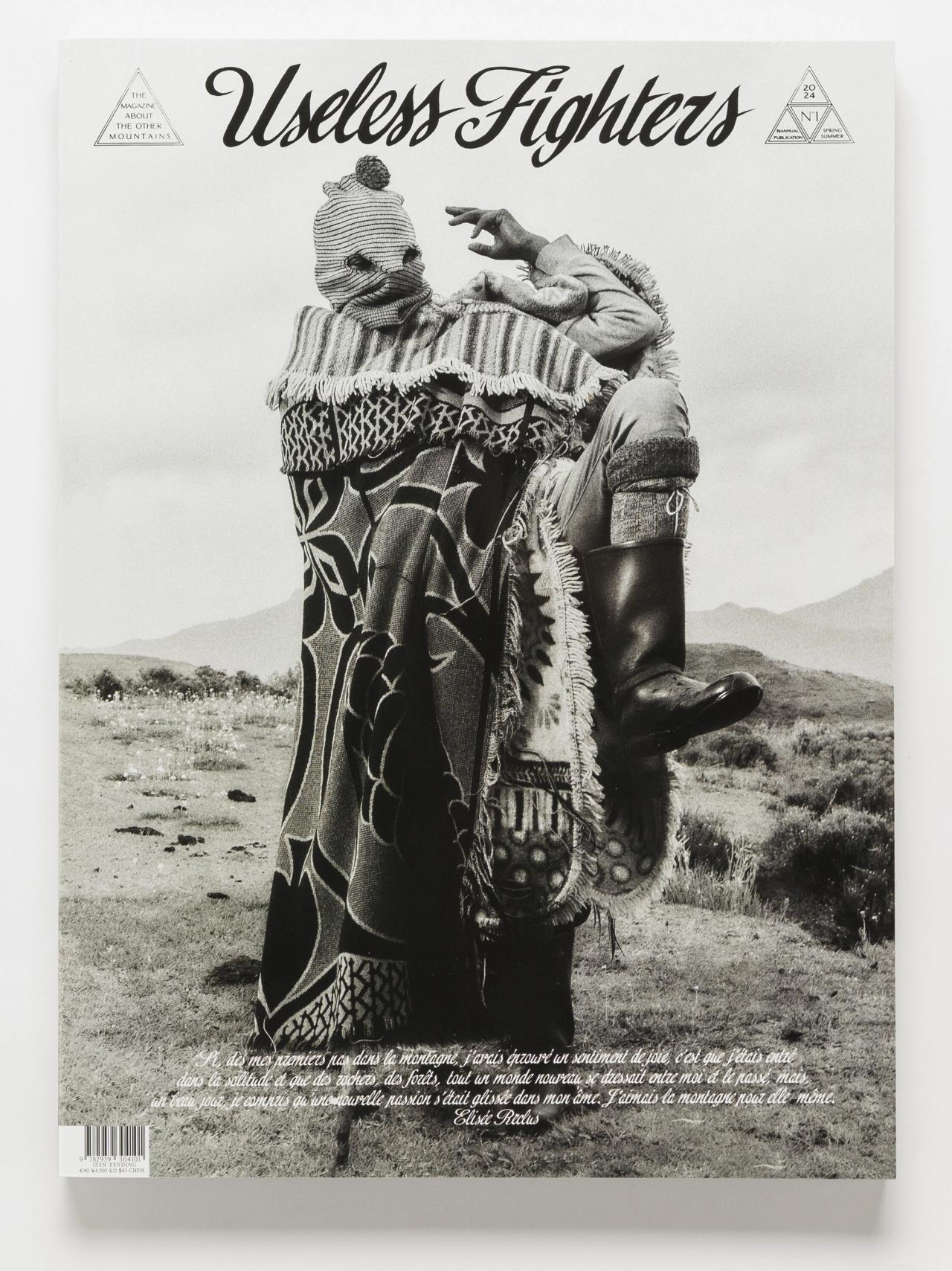

Cover of a recent issue of Useless Fighters. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: I read that you’ve got something like five more hotels in the works?

RT: Three right now.

SB: Oh, three.

RT: Actually, I can have twenty because since I did Drei Berge, the business model was so unique that everyone in the hotel business came and every time they come they say, “Do you want to do a hotel with me?” Because they’ve never seen that. I never did a benchmark in my life. When I do a hotel, I do it from my own experience and from what I want. I never look at the business of other people. Buly [1803], never watched, never did… Even for the smell of Cire Trudon, never checked what people there…. I do what I want, and it’s something I…. If you work with me in my office and you have just the idea of doing a benchmark, you are fired in a minute. It happens a lot because the new generation, they arrive and say, “Okay, let’s see what the other people say.”

No, no, no, no, no. We do from your brand, straight from your brand and from your own experience. Yes, right now I’m thinking about two other hotels, one in Udaipur—I saw the location, and I’m going back mid-May—and one in Japan. In Japan in the mountains.

SB: Hokkaido?

RT: No, no, no, no, no. There’s many places next to Nagano. It’s easy. You can buy a village, actually, right now with the yen so low. You buy twenty little houses. You do something unique and you have fun. You become the king of hôtellerie. Right now, I want to go… Ramdane wants to do Aman. [Laughs] I just discovered that with a hotel, you can say a lot of things in one place.

Inside Ramdane’s home in Paris. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: It’s Ramdane A to Z.

RT: Not A to Z, I think the A to T, there’s a few things you cannot do in a hotel, but it’s not bad. It’s not bad.

[Laughter]

SB: You’ve also got these restaurant projects going. I read that you have one, a French izakaya restaurant in the works.

RT: It’s a very funny story of this restaurant. The restaurant was done, designed, staff hired, everything. The week before we opened, I was walking, it was 7:20, 7:30, I was walking up to my house and I say, “If this restaurant is open, it’s going to be the moment where the people will call me to tell me, ‘Here are the reservations of today, na na na na na na.’” I said, “Ahh, I’m tired. It’s 7:20. I don’t want anyone to call me at that time.”

I was walking up to Pigalle, where I live, and I called back the chef, and the chef was in not a good mood that day, a Japanese chef called [Ryutaro] Kobayashi. He’s still working with me, but that day he was not in good mood. I just hung up and said, “Ummm, I don’t like this project.” I have this freedom in my mind, and I told you I’m a little bit dumb. I walked, I remember, I called the guy and said, “Guys, I’m not doing it.” He said, “What do we do with the stuff?” I said, “I don’t know. We can find another job, do other things.” I canceled everything. I didn’t want to be bothered at that moment out of the day. The hotel is already a lot of work, a lot of energy, and I didn’t—

SB: It’s interesting. I mean, what you’re saying is that you’re respecting your time. You don’t want to have your time impeded by—

RT: My friend, I have one life. I don’t know if you have two, but me, I have one. I did everything well. I was homeless twenty-five years ago and now I’m doing very well. I have the house and everything, and I just discovered that I don’t need anything, nothing. I don’t need this hotel even. I did it because I like it right now. This is a good experience. Sometimes people say, “Why do you stop companies like that?” It’s just I don’t like it at that moment. I have something magic; it’s my brain. I don’t need money. I just need my brain, and—

“I don’t need money. I just need my brain.”

SB: You’ve had this sort of serial entrepreneur streak. You make something, you finish it, you sell it, you move on.

RT: Sometimes I close it down.

SB: Yeah.

RT: I wake up in the morning and say, “Fuck it, I’m done.”

SB: [Laughs]

RT: I’m super, super free in my mind and super anarchist.

SB: Yeah.

RT: I have sometimes deals people don’t understand. Sometimes I insult banks and I put on speakers like all my staff listen to it. I insult bankers. I explain to them how they’re useless for this planet and for myself. I don’t know, I’m totally crazy and I love it. I always say to my wife, “It’s not what we’re going to do, it’s how we’re going to do it.” This is the most important. Right now I like the hotel and it’s very annoying because I really like it, but sometimes it’s hard, but this restaurant, I said, ‘Fuck it. I’m not going to do it.” I don’t want to deal with a lunatic chef, and I speak with Ignacio [Mattos] here in New York sometimes. I say, “How do you do it?” “This is part of the game,” he says. I say, “No, I don’t like this game. Play it you. I don’t want to do it.”

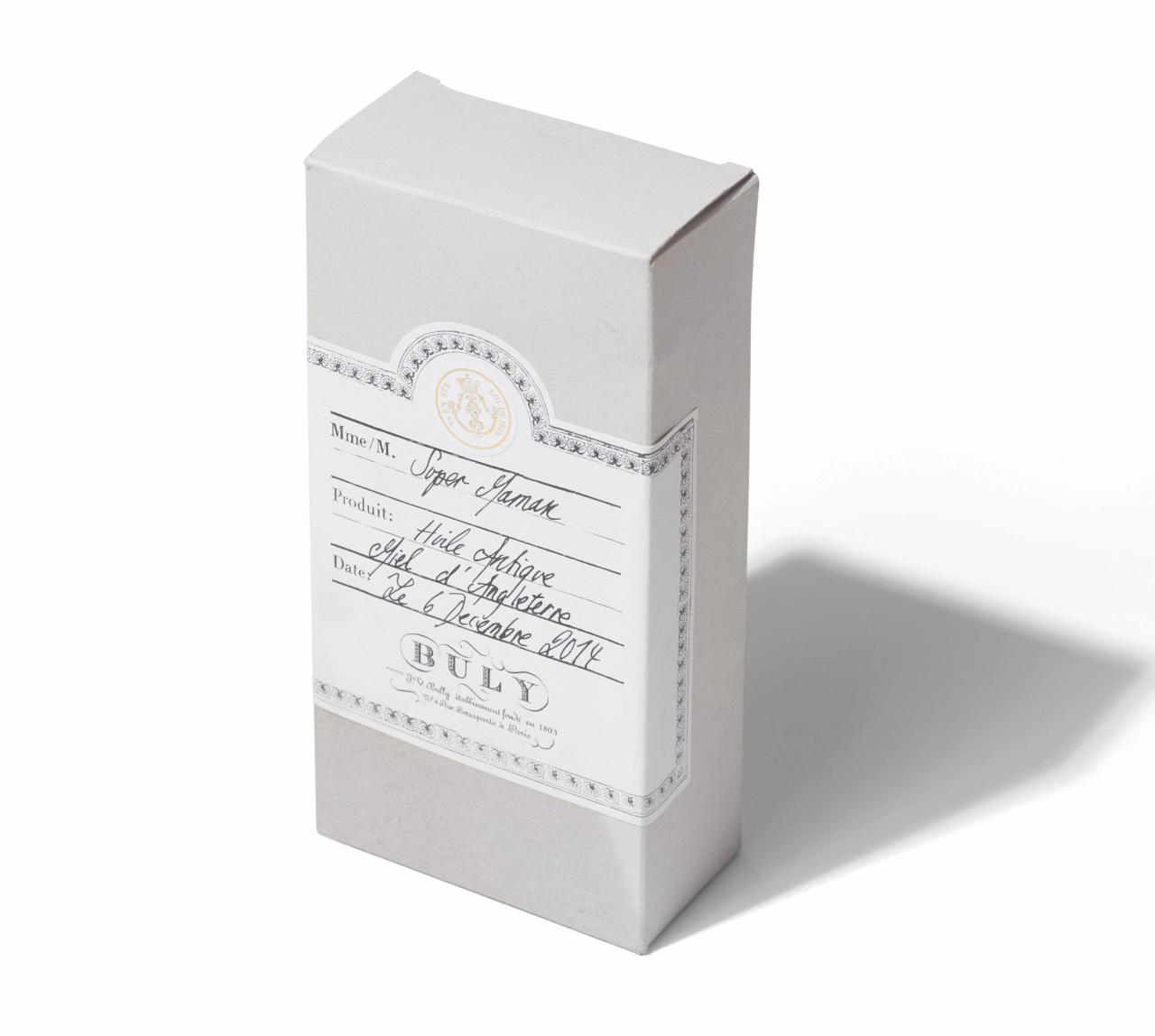

An early product from Officine Universelle Buly 1803. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: Here we have to talk about Buly, this cult grooming brand that you and your wife created in 2014. It’s based on this “lost” Parisian perfumer.

RT: No, it was a…. It was—

SB: It was real.

RT: No, no. The brand was around.

SB: It was real.

RT: It was one product.

SB: Yeah, but you took that DNA and made it something totally new.

RT: Yeah, yeah. Based on one thing that was existing.

SB: It was so incredibly successful that you were able to sell it in 2021 to LVMH. Now that a decade has passed since you initially re-created this Buly brand, what’s your take on why it was so successful? Why did it catch on in this particular period of time?

RT: I remember I was living in New York when we started this project. It was just the moment I sold Cire Trudon, my shares, my forty percent shares at Cire Trudon.

SB: The candle company that you—

RT: Also revamped from A to Z.

SB: When was that candle company—

RT: 2006.

SB: That was 2006, but when was it originally from? It’s like in—

RT: 1643.

SB: Yeah. Incredible.

RT: No, the company was here. 1643. It was the supplier of the king, and you have to—people forget, but candles were the light. It was basically the light provider. It was a big company, whatever. It remains working, and they were doing only the church business. When I arrived I said, “Guys, let’s do something,” and we did Cire Trudon. Actually, the number one seller of this company is the Abd El Kader candle, and it’s the name of my father, which is very funny. Then, when I was with this guy, we didn’t get along, whatever. Sold my shares, did my thing.

I had this project in 2002 with a friend to go to source all over the world all the beauty secrets. This girl was working at Estée Lauder. She didn’t want to quit and stop this project, but I had that in mind. Why don’t we go to Morocco and ask the grandmother what they were using before the soaps? Rhassoul, these kind of clays and oils, argan oil and other things. That is the more known, but there’s a lot of other things. I start to ask that of all other countries, I mean, the brown world, which means America—South America, not North America—South America, Africa, and Asia.

We went to India, we went all over, and I did this trip and I started to…. We wrote a book with [my wife] Victoire de Taillac about that, which actually he sold at Simon & Schuster. We did that and we never did anything with it. When I sold Cire Trudon by myself, without Victoire at the beginning. I said, “I want to be able to show how good I am and I want to do a project that I do A to Z: packaging, bottle, label, smell, texture, everything. At the beginning it was just a massive project to show all my skills to clients and to start an agency from that. Just one store to show how good we are and people come to us. They use my brand and I do things for others.

An outpost of Officine Universelle Buly 1803. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: But it lit like wildfire and you did fifty-one stores.

RT: Actually more now. Right now, I don’t know, I will stop counting. I think we are more than seventy, seventy-five with whatever. I did this first store. The store went crazy. After we did the second one and the second one, I said, I’m not going to replicate the first one. I have to do another one because I don’t want to be bored and I want to show the people I’m able to do another style. At the end, I ended up doing sixty-five or sixty-six different stores one by one and—

SB: Each is really about its—

RT: Totally different.

SB: —specific space and place. It’s very much this hyper-local idea. How do you take what’s ingrained in this structure? What’s ingrained in this location?

RT: Very important. I call it “aesthetical deglobalization.” I mean, the idea of taking an American brand. I take an example: Le Labo, super industrial, made by French people, business school, coming from L’Oréal, do the shitty things, whatever. I’m sorry, it’s a lost bullet, and not shitty, but different. Let’s call it like that. Not my taste. You do this very industrial New York kind of thing. Pretty well done in New York, and you basically do the same industrial concept, New York, all over the world. No matter if the building is eighteenth century in Paris, twentieth century in Tokyo…. You don’t care where you are. You sell this massive, “This is what we have to sell.” I don’t like it. I think when you go somewhere, you cannot destroy the whole thing.

The first thing I think when I do a design in Tokyo or somewhere else: What happens if we crash? I want people to be able to reuse my furniture. That’s why I try to keep a local side of the work I’m doing everywhere we go. The first two, three stores, the first one we did actually outside Paris was Taipei. In Taipei, I came and I did this very super French thing in this Taiwanese building. I was like, “Oh, it doesn’t work.” The store did well, but I didn’t like the experience. Maybe I was wrong. We did the second one, Korea. The first one was super Korean. I did something very Korean. I went there, I talked to the designer. “What metal did you use?”

Then, we went to Japan and we did this half-half. This half-half, it’s funny. There’s a book here on the shelf [of this recording studio] of a guy who was supposed to do the Japanese half and me the French half. He sent a fucking—sorry—amazing heavy invoice. I said, “I don’t have the money, man. We are tiny.” I had to design the Japanese part and I liked it. I did this both, and I did all the Japanese ones who became the success we know now, but we had fun. I’m still designing all the stores. I just delivered two last month.

I still love it. Building is really my kingdom. I do whatever I want, it’s funny. Bernard Arnault and I get along on that. I believe he told me he likes the shop we are doing. He likes the work we’re doing. He really gives me a hundred percent freedom. This company respects, really. When they like the designer, they give you the keys, they really do the thing.

Interior of an Officine Universelle Buly 1803 store. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

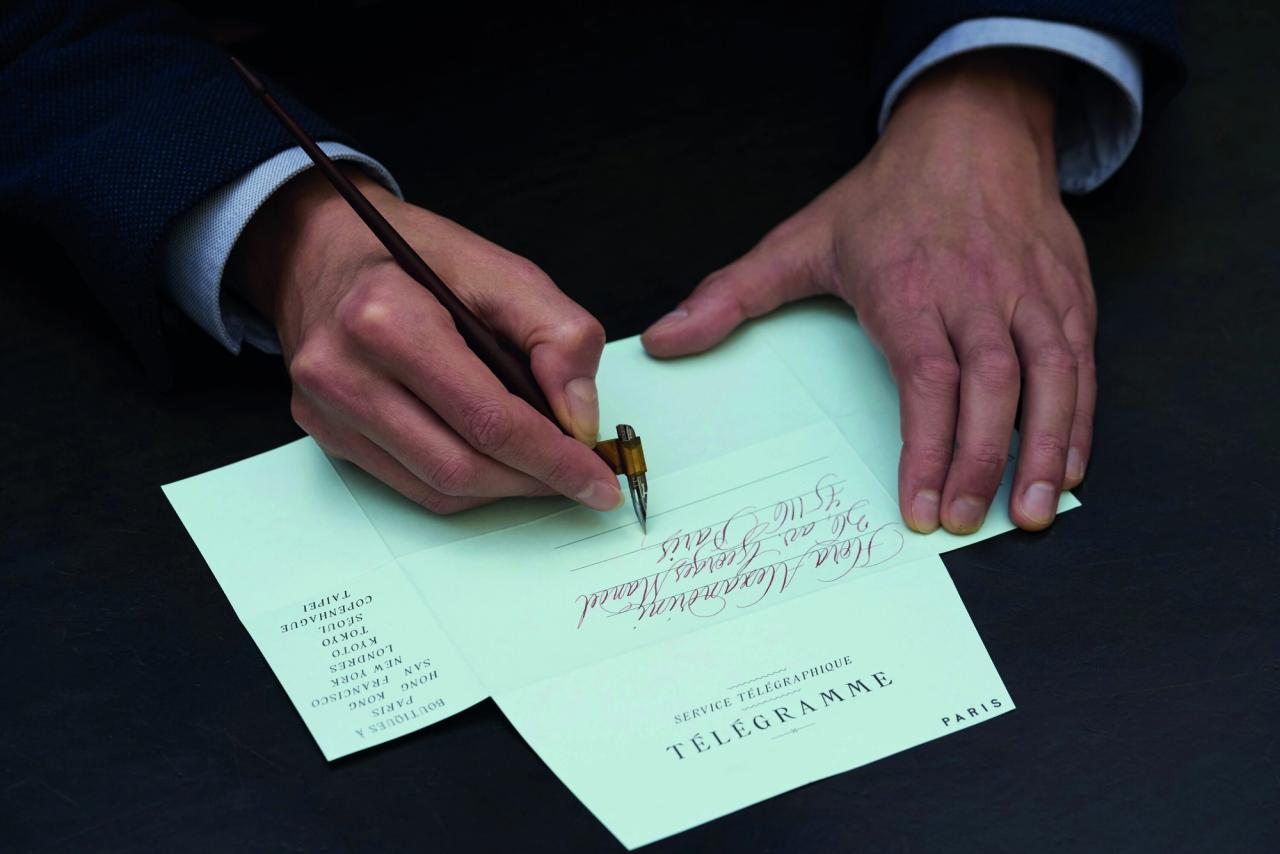

Typical gift wrapping by Officine Universelle Buly 1803, complete with handwritten calligraphy labels. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: One of my favorite things about Buly is how you employ the origata gift wrapping. You should explain it because—

RT: I can see your passion for Japan there.

SB: This gift wrapping is very special and it goes back centuries, this tradition.

RT: It’s a family, actually, who does that for the emperor. It’s the art of gifting. It has hundreds and hundreds of different ways of saying things through pleats and wrapping actually. Actually, this origata history, and also craft, went to fashion. You can see it with—Izumi Aki did things with it. It’s magic. It’s part of the culture of Japan, and there’s one family that does for four hundred and fifty years the same wrapping only for the emperor. It was men’s, men’s, men’s, men’s forever, and the last generation, it’s a woman who does it. She was touring to see some posh French whatever all over Europe. We had access to her and I said, “Listen, we are working on that project and I want to do the most beautiful gift. Can you help us or teach us how to wrap all these things and show us a little bit of origata?” She was like, “Okay.” We hired her for a consulting thing at the beginning and she helped us, too. But that is one detail.

Calligraphy, calligraphy, people think, “Oh!” You know why we add this calligraphy project idea to Buly? Because I didn’t have money to do packaging for each product, and I said, “Oh, we’re going to do a label, write the product.” If you see Buly, which is very funny, the brief is super complex. No plastic. It has no plastic—except the lip balm. The whole brand, no plastic, no tubes, caps, everything is metallic or glass.

Every product is on the box and they say, “Okay, we’re going to finish it by hand. We’re going to write it.” I didn’t like the writing or the first stuff we did. I say, “Okay, let’s find a professor of calligraphy.” We bumped only guy. He was not doing very well. No one was going to his school of calligraphy. He was about to crash, and we said, “Do you want to work for us?” He said yes. This guy taught calligraphy to four hundred or five hundred people, and now every single staff member at Buly knows how to do calligraphy. We have a system to teach you in three months, and it works very well, except one or two countries and we withdrew from these countries.

“I’ll never do something without a political agenda.”

No one writes anymore with his hands. We write on our phone, on the computer, we don’t use…. This idea of writing with hands will disappear within one generation. This is something I don’t like to happen. I say, “Guys, let’s push it to this.” I’ll never do something without a political agenda. There’s always something political with what I do. No plastic, it’s for the nature. Reusing the bottle, reusing the candle jar. You have to have a second life of the product, but calligraphy also gives this envie to the people to go back to writing with their hands.

SB: You’re using the system of capitalism to sell beauty goods, but for an end also to promote this craft and this art, this dying art, which is—

RT: Also for the beauty secrets.

SB: Yeah.

RT: The oils, the clays, I remember we had…. What was the name? This bird shit was the best scrub in the nineteenth century, eighteenth century in Japan. We went there and…. The Treaty of Washington on the birds, this beauty thing was disappearing. We were the last in the world to have it, and we bought all the stock. The guy was super surprised and we sold out in five minutes. It’s funny, you see things right now disappearing very quick because the whole perfume world is destroying everything. It’s a dictator of perfume right now. Your house has to have a smell, na na na na, and all these beauty secrets are very efficient—if you use this oil or this oil. They are much more efficient than the beauty chemical things that have been used by humans forever. They’re all disappearing. Sometimes the farmers don’t produce any more of this plant…. In ten years I’ve seen plenty of them disappearing.

We were the last to buy it, like black soap from the Ivory Coast made with clay from the soil. We have seen a lot of things disappearing and we have seen things overused. Shea butter. Shea butter, big boom, everyone is using it. Same for argan oil. They are destroying whole argan trees. This is one of the only trees in the world you cannot have a seed, put it, and it grows. No one knows how it grows, still now. Now, they’re doing it industrial. They don’t even let the argan seeds grow enough to be very efficient.

Same for shea butter. Shea butter is like tomatoes. You have very bad ones, what you see in the supermarket, and the best ones, who have enough sun and are very tasty in the south of Italy in August, in the summer. We discovered the difference between the quality of the things, and Buly, we just pick the best. When we take a tsubaki oil, a camellia oil, we go to the Gotō Islands. The Gotō Islands are the best. For the Japanese it is the pick of the pick of the pick, and we go. We pick from the best of the best. Buly was, at the beginning, one store and it became a lifestyle because I start to travel all over the world. I go to island of Chios. I’m going to buy sponges.

People are like, “Wow, you’re going?” Yeah, it’s my work, and I go there and I’m going to find in the same village I go to for sponges, same place for sponges since the Roman time. I discovered the gum of Chios. Gum of Chios is like the ancestor of the gum, like chewing gum, and it’s very good for the gum of your mouth and everything. I went for the sponges and I bought also gum of Chios. I did that all over the world. I go for something and I buy another thing and I buy more and then from the stones, from the clays. We used to go to Ukraine to buy the blue clay, and after we went before the war to Russia to buy another stone, I went all over the world and it became a crazy life.

SB: It’s like a game.

RT: It was super amazing, actually. It started with a store and it became a lifestyle. It’s what I’m doing with the hotel right now. It has to be my life. It doesn’t have to be a business.

SB: I wanted to add here, too, you mentioned the magazine Useless Fighters, but you do a lot with printing and publishing, too, and—

RT: Yeah.

SB: … and are a typography obsessive. You’ve got this really impressive printing operation which includes this factory in Switzerland.

RT: No, we have France also.

SB: You have France, but you also have this factory in Switzerland whose acronym is, hilariously, SHIT.

RT: It is SHIT, Société Helvétique d’Impression Typographique. Yes, I changed the name to be more funny.

A “calligraphy telegram” from Officine Universelle Buly 1803. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: The printer in Paris is an antique printer. You’re using eighteenth-century techniques. Talk a little bit about that.

RT: Even older. It’s an art. It’s engraving. It’s a very Parisian technique, and when you go to Paris, you want to do a business card. There are all these little shops who does all the business cards have only one supplier. Collusion. During Covid, this guy was about to crash and we bought him. He was the last guy remaining who knew how to do this technique and we saved it. We sent three people, who learned it by heart with him for three years, and then we bought the company. It’s still here. A hundred percent of the fancy business cards in Paris are made by one company, my company, and we used it also for Buly at that time.

This is what we do, basically, and after we bought him, I didn’t know I was going to put a hand on the biggest collection of monograms on the planet. We are talking about fifteen or sixteen thousand monograms. Wow. As a font freak like me, wow. This is bingo, but before we bought another company was one of the oldest with some Heidelberg Red Ball machines from Switzerland. We merged these two companies and we are doing things, and I used it, but now we added a silkscreen studio with it. We are adding things.

Inside the Société Helvétique d’Impression Typographique (SHIT). (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

Various lettering stamps at the Société Helvétique d’Impression Typographique (SHIT). (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: You’re making magazines, you’re making books.

RT: We do magazines, we are.

SB: You have this bookstore. Tell me about that little publishing unit.

RT: We have also a publishing company. We publish more political super lefty magazines because this is my side. I’m more anarcho-social, but I’m super lefty. Also with a guy called Émile Shahidi. We have the biggest collection of radical magazines from all over the world. I have the biggest collection maybe in the world, twenty-two thousand publications from the Black Panther Party magazine. I have all of them, like LGBTQ, whatever. All the number, letter you want to add, we have all of them.

SB: Where do you store all these?

RT: In Paris. It’s a foundation. It’s called Radical Media, and we have all these Radical Media things, publications from 1946–7 to 1980 also, that we are buying every day. My money goes there. It’s that or a Ferrari. I bought things like that. We have a huge collection, but we are right now digitizing and we’re going to show to all the world.

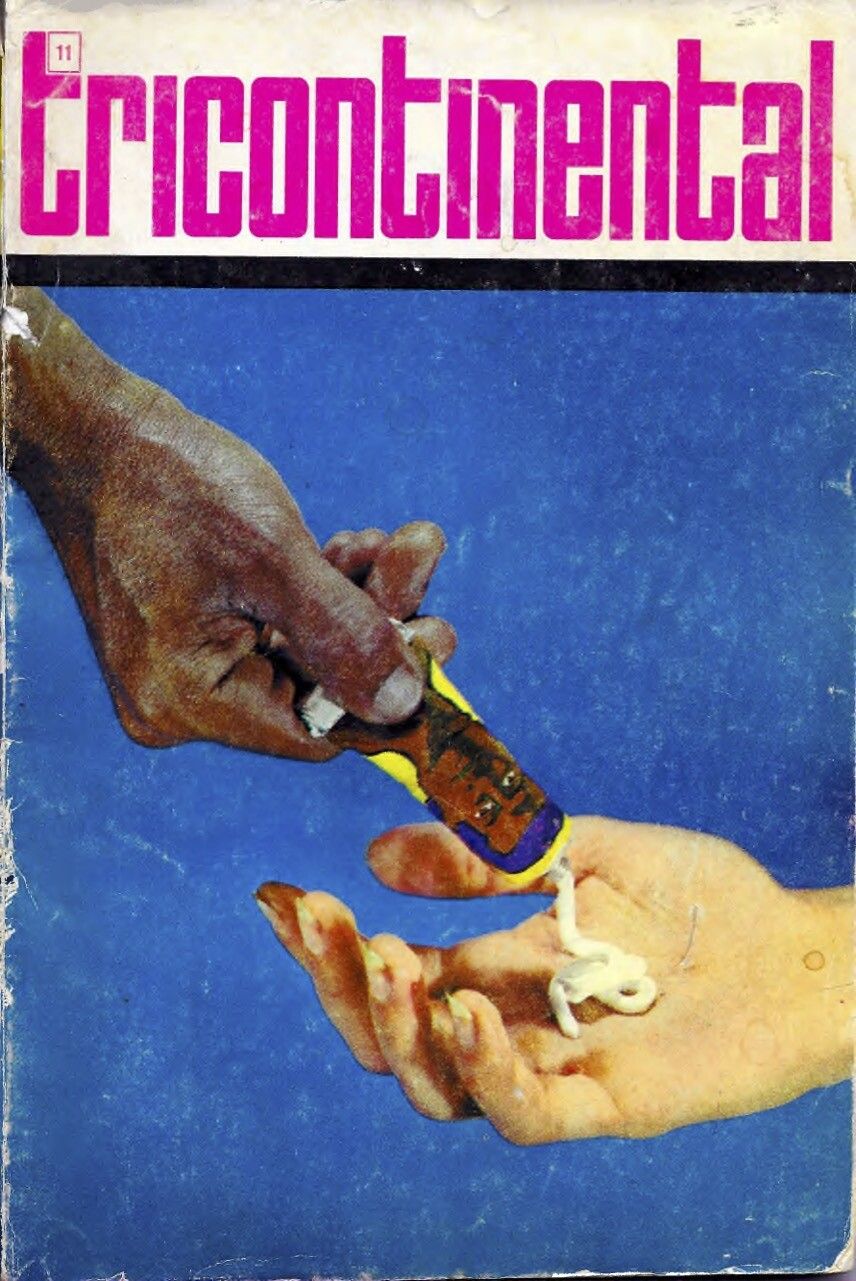

Last year, I had a very funny story. I wanted to buy this Tricontinental magazine. It was very political from…. The headquarters was in Cuba and closed. It was online for the last 20 years, but before it was a paper magazine and the Tricontinental is South America, Africa, and Asia, a magazine about brown people, very political. The archive disappeared when they stopped during Covid. And guess what? We found them in a Trump supporter’s garage next to Fort Lauderdale in Florida, and when we found out, I took a plane and I bought the whole archives and we moved them to Paris because—

A cover of Tricontinental magazine from 1969. (Courtesy the Freedom Archives)

SB: I just love this image of you getting on a plane and flying to Fort Lauderdale. [Laughs]

RT: Yes, and meeting this guy and say, “Are you lefty? Why did you buy it?” No, this guy hates Cuba, but he buys all these vintage things from Cuba to try to sell them in America, like a crook. I mean the worst guy on the earth, but super happy. We had original drawings of [Patrice] Lumumba and things like… I was super happy. Super expensive. He gave the price. I was shocked, but said, “Well, let’s pay for it because it is history.” We bought all the things. It’s an adventure. My life is very—

SB: Yeah, it seems—

RT: I told you, I don’t think so much.

SB: Have you ever watched the TV show How To With John Wilson?

RT: No.

SB: It’s on HBO. Anyways—

RT: Ah, How To, I remember. I never watched it. I know the name.

SB: In it, though, he basically goes down these different wormholes. I feel like your life is kind of like that. You discover something that you’re obsessed with, and then you follow that obsession into the next one and into the next one.

RT: Exactly, and I learn a lot. At the end is what is left in my brain—

SB: And you find yourself in Fort Lauderdale buying these Cuban magazines from a Trump supporter.

RT: Yeah. I assure you, we did a beautiful video introducing all these projects, and I’m super excited because this thing brings me to another idea: Why don’t we digitalize all the best magazines in the world and do a kind of Netflix of the best magazines? We’ve been working on that, and it’s going to happen because I saw it’s out in six months. We developed it already. We did a company in Switzerland. It’s happening.

SB: It’s so incredible. You also have this podcast studio. You do so many things. [Laughs]

RT:I have seventeen companies right now.

Touhami (right) during his childhood in southwestern France. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: I feel like we could just keep going, but I do want to have the opportunity to talk a little bit about your upbringing because it’s so fascinating. You grew up in this Moroccan-French family in southwestern France, in the countryside.

RT: Yes. Yes. Next to Spain. Next to the Pyrenees. Let’s talk about the mountain.

SB: The son of an apple picker, and I also read that you’re the grandson of a Moroccan hero, so I have to hear that story.

RT: Moroccan hero, yeah, if you ask him. He died, sadly. He’s my grandfather. First, I have a great-grandfather who had also a crazy life. He grew up in the north of Morocco when it was a French colony. They picked him up when he was 17. They say, “Man, you’re going to do the first World War.” He arrives in ’17 or ’18. He arrives in France. He fights for the French, and in 1917, he has a bullet in his leg. He stays in France in the hospital, and actually he’s going to work in the mine in the North of France. He’s going to work in mining, stay in France. Like a hundred years ago in France and he stays. Everyone left, he stays. Then, after a few years he decides to go back to Morocco and he stays there. It’s 1934, ’35.

Touhami’s grandfather. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

At that time, [Francisco] Franco was building his army to attack Spain for the counterrevolution and becoming the fascist country that Spain was going to be until 1975. He built his army of North Moroccan people. Don’t forget, in 1926, Spain also destroyed all my villages in the north because we tried to fight against colonialism. Whatever. He picked my grandfather. Joined the army. My great-grandfather was saying he was doing two things: mining and wars. He’s going to fight for Franco and go to Spain. Then, 1937–38, go back to the village. Nothing to do. 1944, joined the French Army, does [the Battle of] Monte Cassino in Italy, goes back to, say, France again. This is his life basically. A crazy guy.

He fought all his life. Crazy, when I think about it. And you have his son who worked for the French, and my village is at the border between Algeria and Morocco. We are on the Moroccan side. The story is very funny. The French said, “Okay, you have to look at the border. Be careful. Some Fellagha from Algeria can pass the border.” He had a shotgun and he was just at the border. There’s one guy from the French Army who was going to all the villages. He was showing the French torturing Arabs, and he said, “Guys, if you want to go against France, this is what is going to happen to you guys.” He was showing this video in all the villages. He was a colonel or a captain, I forget. This guy was a number one target for all the Fellaghas, the people who were fighting France. [Laughs]

Touhami’s grandmother. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

We had a curfew, and my grandfather was at the border and he sees a guy on the bicycle and he said, “Aah, first un, stop. Stop, it’s curfew.” First, second, third warning, my grandfather takes the shotgun, bah! Shot. Guess who he shot? This captain who was showing the videos—my grandfather killed him, and the French came to him. They said, “Man, we told you to shoot Fellaghas, not the French.” He said, “It’s dark. I didn’t see. I shot the guy on the bicycle. There’s a curfew.”

He said, “Yeah, but you have to kill only Arabs.” He said, “I’m an Arab. I’m not going.” Whatever, they put him in jail. Very strange, funny thing. I don’t know how. He had the keys of the stock of the weapon in his pocket. In the middle of the night, he didn’t know, but my grandfather became a hero because he killed a guy who was number one on the list. In the middle of the night, they went to this jail and they saved him. He said, “Guys, I have the keys of the stock of the guns.” They took all the guns and they hid him in the mountains. He became a hero by accident, actually.

SB: What an origin story. That you’re here because of them and—

RT: Right after the war, the first thing he did, he went to France [laughs]. Whatever. But it’s just a very funny story, and of the grandchildren—

Touhami’s mother (far right). (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: You yourself have this incredible story of, you’re 18, you drop out of boarding school, move to Toulouse. But then you’re kidnapped and tortured.

RT: Oh no, that was because I had a lot of cash.

SB: You created this brand that led to you having a lot of cash and, for whatever reason, this gang kidnaps and tortures you?

RT: Yeah, yeah. Because I carried a lot of cash in bags. They found out, whatever. That is the street problems. That happens when you grew up in the poor areas and whatever.

SB: But your money’s stolen. You flee to Paris, where you’re homeless for about a year.

RT: In the Métro, yes.

SB: Stabbed by a vagrant.

RT: That’s— These things happen.

SB: This story sounds like it’s out of a novel. [Laughs]

Touhami (second from left) with his siblings and father (far right). (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

RT: Shit happens [laughs], but I always had this enthusiasm to rebound and this is my thing. “No” is not an answer for me. Actually, I like “no”s. People are looking all their life for “yes.” Me, I like “no”s. Actually, my motivation comes from when every door was closed. Do you know we are the Black of France? France hates Arabs. That’s why I don’t thank France for what I did. What they did for me. When I do things, “Oh, you can thank France.” No, no, I don’t. I became what I became because they said no. I was looking for a job. I actually, you forgot to say, but I’m an accounting guy originally. This is what I graduated—

SB: Numbers.

RT: Yeah. When I went to find a job, I said, “No, we don’t hire Arabs in the offices.” So I decided to do another thing. Every time it was a no, I had to do my own. I didn’t have clients from an agency. I did Buly. Buly was bigger than the client, but I said because people didn’t want to give me good…. They were giving me small projects, but it was tiny ones compared to my friends’.

I love “no”s. People ask sometimes if I’m depressed when someone says no. But I fought hard to be able to say no myself. That’s why I love “no”s. Now, I’m very happy to say no. I saw two clients yesterday. It’s going to be “no.”

SB: I’m glad you said yes to the podcast. [Laughs]

RT: I said yes to the podcast because you asked nicely and you started this podcast with a guy I like a lot [Andrew Zuckerman], and I said, “Okay, let’s do it.” I remember him asking me to do this podcast two, three years ago. I said, “Yeah, if I have time, I do it,” and I keep my word. If I said yes, I never come back on that.

SB: You mentioned France, but I would say Switzerland and Japan seem to have this grip on you. Even though your roots are in France and you’ve done so much in Paris, and this is maybe both culturally and temporally. Why Switzerland and Japan and—

RT:They’re the same country—seventy percent mountain, both of them. Thirty percent are flat. First country in the world with the train on time, Japan—second, Switzerland, Oldest people in the world, Japan.

SB: Watches.

RT: Number two, Switzerland. There’s a lot of numbers that are exactly the same between Japan and Switzerland.

SB: Why do you think that is?

“Japan and Switzerland are the same country—seventy percent mountain, thirty percent flat. First country in the world with the train on time, Japan—second, Switzerland.”

RT: I have no idea, man. It’s just a thing, and I think I like them because seventy percent is mountains, and I like mountain people. I don’t know. Japan, they came to me first. They discovered my talent before the others. A guy called Riku Suzuki came to me. I was living in my office; they saw a store I did. They said, “Do you want to do the same in Japan? I said, “Yes.” They are more curious. The Swiss are not curious, but the Japanese are. I learned a lot in Japan. I came with my big arrogance. I was 25, 24. I thought I knew everything. I learned everything there. I came—wow! I learned a lot of things, and actually I was shocked. I remember the day I saw A Bathing Ape store in ’98. I was depressed for one month. The only time in my life I said, “Fuck, I’m really bad,” and I said so to Nigo, actually. I learned a lot.

SB: You lived there with your family in 2016, right?

RT: Yeah. Nihongo shaberu? I speak Japanese and everything. I’m curious about this world, and it’s funny. I’m not a huge fan of Japanese cuisine. I like it, but I’m not obsessed. I like much more flavorful things. I like spicy things. But I love Japan, and I hate it after one month. When I stay there— I have a house in Nakameguro, and after a month I want to leave because I’m tired of them. It’s very strange. I have very complex feelings with them. It’s too perfect. It’s like Copenhagen. I hate Copenhagen. All these people, good health, on bicycles, all good-looking. Really? Aargh!

SB: [Laughs]

RT: I love Napoli! I like the mess! I like the smells! I like people stabbing people! I like pickpockets! [Laughs] Sometimes it’s too clean. I’m tired.

Touhami during his travels. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: All right. Final question. What do you do to slow down?

RT: I don’t. I don’t slow down. Why do you want me to slow down?

SB: You don’t go on hikes? You don’t—

RT: Yeah, my slowdown is hikes, but you don’t really slow down when you hike, really. What I like with hikes is I focus on every step. It’s very funny because you remember almost where you put your feet. If you do thirty thousand steps in one day in hiking in a mountain, trust me, your brain was focused on each of them. Walking the street right now, after two seconds, you don’t look—it’s automatic. Your brain knows how to do it. In the hikes, you’re focused, and I love that. The fact that you did thirty thousand little things and you had to focus on all of them. That is, you’re telling me it’s slowing down, nahhh. It’s a different part of your brain that you’re using, and I like to use this part sometimes.

I don’t like to slow down and I will never slow down. I don’t know. It’s not my thing. After two hours I say, “Wow, wow, I’m wasting my time here!” What did you do? I can panic. Honestly speaking, I love my life. I really like my life. Sometimes I wake up in the morning in this mansion. I have a pool in my house, man. [Laughs] It makes me laugh still now. I wake up and I go to this fancy bathroom that was on the cover of T magazine, and I look at me in the mirror and I say, “Man, is it real? Really real? How did you do that?” It’s really that. It’s: you did it. My wife, it’s normal for her. She’s bourgeois. She grew up in a fancy thing. She knows. She has a castle.

A living room in Ramdane’s home in Paris. (Courtesy Ramdane Touhami)

SB: But you were homeless twenty-five years ago.

RT: But for me, every step…. It’s funny. Right now this afternoon, I’m hesitating between going to this meeting and go to see this Bentley S3 1956 that’s for sale in Queens. I have to look, and this morning was really the big hesitation. Really, my life is very funny, and I might buy it [laughs], because I’m collecting these stupid things sometimes. I have a passion for Bentleys. I don’t drive them. I just pile them one by one, and this one is missing a back wall of finishing and I like it.

“I had such a stupid and bad childhood that, right now, I’m thirsty for life like it’s just the beginning.”

I had such a stupid and bad childhood that right now I’m thirsty. I’m still angry. I’m thirsty for life like it’s just the beginning. I’ve been to…. There’s very few countries I didn’t go to on this planet. Sometimes I laugh. I say, “Oh.” Right now, I say, “Oh, I went to Benin. I went to Senegal. Oh, I just went to Ghana.” This one is missing. It looks the same actually sometimes. They look the same.

SB:Easter Island? Galápagos?

RT: No, no, no. They are touristic places. There’s no trees. It’s like a rock. I’m not going to a rock. I mean, you have to be crazy to go to—

SB: Where’s the next place you’ve never been that you want to go?

Courtesy Ramdane Touhami

RT:This summer, I’m doing this crazy trip. I’m going from Paris to Tokyo by car. Because I’m turning 50 and I said, “It’s on my list and I didn’t do it.” I’m driving and I’m not doing the Northern Silk Road. I’m doing the Southern Silk Road, Georgia, Kazakhstan. Go to Russia, end up in the Vladivostok, take a ferry to Korea, then to go to Niigata and arrive in Tokyo by car. I did all of the Mediterranean in 2004 with a Lotus Seven. I like to drive, and as I say to my kids, going every year to the same place for holidays, it’s kind of dumb. It’s very bourgeois. It’s how I consider you’re becoming a bourgeois. Every summer to this Greek thing, whatever, to Marseille, I don’t like it. My idea is we go to a place we’ve never been.

SB: Probably in the mountains. [Laughs]

RT: Ninety percent of the time there’s mountains, yes. Not ninety, actually. A hundred percent. It has to have mountains. We went to Aman the other day with the kids and they were so pissed because we were by the beach and they said, “Guys, let’s go to the mountains!”

SB: [Laughs]

RT: They hated it. They loved it after, but at the moment, they hated it.

SB: Ramdane, thank you.

RT: My pleasure. Thank you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on May 2, 2024. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo based on a photograph by Pierluigi Macor.