Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Paul Smith.

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Paul. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

PAUL SMITH: It’s very nice to be here. Thank you.

SB: I’d like to start this interview on the subject of Japan. This year marks forty years since you first opened your Tokyo store. Japan is your brand’s strongest international market and, over the past four decades, you’ve opened one hundred sixty-five stores across the country—just Japan. [Laughs]

PS: I know.

SB: Let’s start with your first trip there. It was in 1983. What brought you there? How’d you respond to the place? How do you think you became such a phenomenon so quickly?

PS: Well, how I got there was I was standing in my store in Covent Garden—I was often in the store myself—and my office was above, and this gentleman came in, a Japanese gentleman, and he said, “Can I talk to you?” And I said, “Yeah, of course.” He had more about me than I had about me, which was press cuttings, photographs, fashion shows. He turned out to be a scout, a Japanese man who was employed as a scout looking for European designers. And I was on a short list of— There was one Italian, one French, and I was the English/British one. They ended up choosing me, and then they invited me to go to Japan in ’82, was it? You’ve got it written down, probably.

SB: ’83.

PS: ’83, yeah. I went with my wife because we always used to try to go to a brand new place together. The two of us went economy via Alaska—with my long legs. [Laughter]

SB: Oof.

PS: It was nine hours to Alaska and then another nine hours. Then we got on the train. We flew to Tokyo because there was no direct flight to Osaka, but the company I was working with was from Osaka.

Then we got on the bullet train, which of course was very exciting. And then the thing that blew my mind was that we arrived in Osaka and the train pulled in and the three people we were meeting were standing at the door where I was getting out, which, now, you get. “It was in coach three, seat four.” But then it seemed like, “How do they know which coach I’m in?” And they said, “Mr. Paul, we are very sorry.” And I said, “Sorry?” “Train is three minutes late,” they said to me, and that sort of was the start of the phenomenon of my relationship with Japan.

It went on from there, and I’ve been well over a hundred times now. I think the success is just based on the love of Japan and my work ethic and trying to calmly understand both people’s points of view, really.

SB: Tell me some of your experiences there that maybe stand out, including, perhaps, befriending Rei Kawakubo—that might be one.

PS: Yes. The first thing probably was the fact that in ’82, ’83, there were very few gaijin—foreigners—very few foreigners. And being quite tall, if you came across a group of school children, it was always, “Ohhh” … Like, looking up at you. That was absolutely mad and interesting. Of course, now we’re so familiar with Japanese food, so the food was amazing and different. And then the jet lag. I was so fortunate that I had one Japanese friend who was a designer who was making some bags called Porter bags. They were quite cult then and continued to be thought of very highly. We were good mates—actually we met here, in New York.

So I met him and he then introduced me to a lot of people from the press and stylists. One of the people was Rei Kawakubo from Comme des Garçons, who is notorious in being quite shy, quite hard to have a conversation with and almost impossible to actually ever meet. But we met and became quite good friends. And still, if I go there, I still will try and speak to her if she’s in town.

The Paul Smith store in Tokyo’s Ginza district. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

SB: You’re someone who can truly say, “I’m big in Japan.”

[Laughter]

PS: Yes, that’s true. In more ways than one, yes. I went to—on about my fourth trip—I got invited to one of the Paul Smith staff’s family house, which was unheard of, really, really unusual and really rare. It was in Kyoto. We went to this lovely wooden house and the boy from my company knocked on the door and the door opened and we couldn’t see anybody. I nearly trod on his mum because she was completely flat on the floor, because she’d never met a person from a different country before, ever.

I said, “Mr. Arcada, is your mum, okay?!” He said, “Oh yeah, she’s so humbled to meet somebody from a different country that she’s bowing—or, actually, lying—on the floor.” Then I was saying, “Oh, please get up. Please get up.” She wouldn’t eat with us, either. She insisted on eating in the kitchen and only served Mr. Arcada and myself some food. All sorts of very interesting experiences that now probably wouldn’t happen in the same way, many years later.

SB: You mentioned you’ve made more than a hundred trips there. You go, from what I understand, at least twice a year for around ten days each.

PS: Yes.

SB: Beyond the business, what’s kept you so engaged and wanting to keep going back?

PS: I think I made a lot of good friends there that are not in the world—my world—not in fashion. There’s a very beautiful magazine called Casa Brutus, and it’s one of my favorite magazines in the world, and Pen magazine, as well. And both of those, the editors and the writers for those magazines are just so interesting and so passionate about the subject that they’re working on. It could be ceramics or pottery or something, and the ghost from Raku ware and Bernard Leach and the history of Raku ware in Kyoto.

But then they’re talking about mountain pottery and the finesse of creating a piece of pottery, and they just dig in deeper than anybody else, really. If they were doing a magazine on pen knives, there’ll be, like, forty pages of pen knives—

SB: [Laughs]

“I’m constantly playing with big and small or rough and smooth or kitsch and beautiful.”

PS: —or forty pages of shoes, loafer shoes, or whatever it is. It’s fascinating.

SB: Yeah, and there are many quite obvious connections between your background and interests and what you do and Japanese culture. There’s of course the craftsmanship, but there’s also the attention to detail, the obsessiveness with going in depth in one area or even just the surreal juxtapositions between things that the….

PS: Yes, the love of contradiction and opposites, which I love. I’m constantly playing with big and small or rough and smooth or kitsch and beautiful. I did a collaboration of shirts with Comme des Garçons, and they were all hand-buttonholed and hand-stitched, and they were absolutely mad. They probably never sold one—

SB: [Laughs]

PS: —but both Rei and I adored the project because it was so self-indulgent. [Laughs]

An example of Japanese joinery and woodwork. (Courtesy Japan Up Close)

And then I fell in love with Japanese joinery and woodwork, for instance, and learnt a lot about why their joints are so intricate, which I never really realized, which I’m sure you know. But years and years and years ago, all the houses were wood and they were built out of wood that was quite mature and had a long time just sitting there, the wood. But then, eventually, as they built more and more houses, the wood wasn’t so mature and often because it’s very humid, often the joints would just twist and they weren’t that stable. So they invented all these amazing woodwork joints, which were double joints so that they couldn’t twist. And so things like that, where just the passion and the detail…. It’s just lovely.

SB: Yeah. We could probably go on with Japan for a long time. I do have a couple more questions. One is just overall, how do you think about your “Japan time,” if we could call it that—all these months that you’ve spent there over the course of your life, and how do you think it has impacted Paul Smith the man and Paul Smith the brand?

Smith as a young man. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

PS: I think one of the things I learned very early…. Because I went when my business was quite young, and I left school at 15 and started my business in my early twenties, so I never really had education in anything. So I learned, going to Japan, that they used to have these things called “meetings.”

SB: [Laughs]

PS: I thought, “Oh gosh, maybe I should have a meeting. I’ve never had a meeting.” [Laughs]

When they did have meetings, there’d be the person you were meeting, but also there’d be six or eight or ten people just listening. And I thought that was intriguing. I just thought that was fantastic because then they were all in the picture. They understood what the conversation was about if they had to be involved in that topic later. And that was very interesting.

Then I worked as a photographer, as a hobby, really. And then I did photographs for several magazines in Japan as well. One of the magazines, I think it was for Elle Decor, and we went to a very, very old village in the middle of nowhere where the houses dated back for many, many years. There was a walk from one village to another. I did photographs of that, and that was really lovely. And then I took these photographs and then I realized, I said, “What is that sign?”

There was a sign and a small bell, and they said, “Please take this bell when you go on this walk from this village to that village, and if you see a bear, just ring the bell.” And the bell was like one inch high on a ribbon.

SB: [Laughs]

PS: I just had this image of like, “Hi, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding.” And the bear goes, “Oh yeah, sorry about that. I’m off now.” [Laughter] It just blew my mind that you would see this big grizzly bear and you’d just ring a very tiny little tourist bell.

SB: You’ve spoken about how in Japan they respect age, that wisdom….

PS: Yeah, I love that. I love that.

“The thing I’m most proud of, really, is continuity.”

SB: This feels like something we should adopt in Western culture more. I’m not saying that we don’t, but we definitely don’t to the degree that they do in Japan. What do you think about that?

PS: I think the whole world is moving so fast that I don’t think we consider many things enough anymore. And I don’t think we appreciate every day like we should. And I don’t think we appreciate simple things like conversation, love, touch, emotion, calm hobbies. What’s so lovely there is that they really respect experience. So with an older person, yes, you might not be able to walk very well or you might be hard of hearing, but they really respect that you’ve led a life which is to do with a certain job or a certain way of life, or you’ve brought your family up in a certain way, and it’s really charming and lovely, really great.

SB: Now that you’re 77 and you have more than five decades in business, a remarkable feat—more than remarkable—what are the bigger reflections that you have about the subject of age or about things that occur over a long span of life experience?

PS: I think the first thing is that I’ve been in business for, I think, fifty-four years this year. And I think the thing I’m—this is not answering your question really, but just as an observation—I think the thing I’m most proud of, really, is continuity.Because I think especially in business, so many people just want to build a business which they then sell on after ten years or fifteen years, or—that’s the whole motivation is to actually build a business to then sell, or sadly they don’t really keep their feet on the ground, so the business comes and goes quite quickly. And it doesn’t have to be a business—it could be your job, it could be a magazine or a musician, restaurants.

“Getting older, the key thing is not being too proud or silly to think that you can’t relinquish some of the points of your business to younger staff.”

In this city, lots of the restaurants I used to adore to go to are no longer here. So continuity has been really, really lovely. Getting older, I think the key thing is not being too proud or silly to think that you can’t relinquish some of the points of your business to younger staff and trying to observe the talent of younger people around you, and then really bringing them on to have a bigger job. And that’s, for a lot of autocratic people, which probably I am, I don’t really know, but just try and make sure that you’ve got a team around you that you give them a chance rather than always try to interfere with the decisions they’re making.

SB: Speaking of continuity, for any business to have five decades of continuity is remarkable. But in the fashion business, I think it’s particularly so. What do you make of your longevity? What has been key to sustaining the Paul Smith brand for so long?

PS: I think one of the things in Japan was the fact that they could say Paul Smith.

SB: [Laughs]

PS: You can imagine if I was called “Herbert Von Heidelberg” it might’ve been more difficult [laughs], but I think Smith is…. Actually, they can’t say Smith that well. I think the love of life—on a serious note. Every day is a new beginning to me. It’s such a joyful job. And I’m the boss, but I’m not really a shouter or an arguer—I just enjoy discussion and work it out. Very much a—I hate the word win—but it’s like everything’s both people coming out with a satisfactory result, really, from a situation. I think that helps. And then also knowing your job, really understanding your job is what you do for a living. It’s just clothes.

SB: As I was preparing for this interview, I was looking at what’s been written about you over the years, trying to decipher and understand what makes the success. Of course, a lot of people have written about this notion of “classic with a twist” which goes back to the early eighties. But The Guardian has said that, “He has always succeeded because he has anticipated the shape of things to come.”

PS: Yeah, I think that’s true.

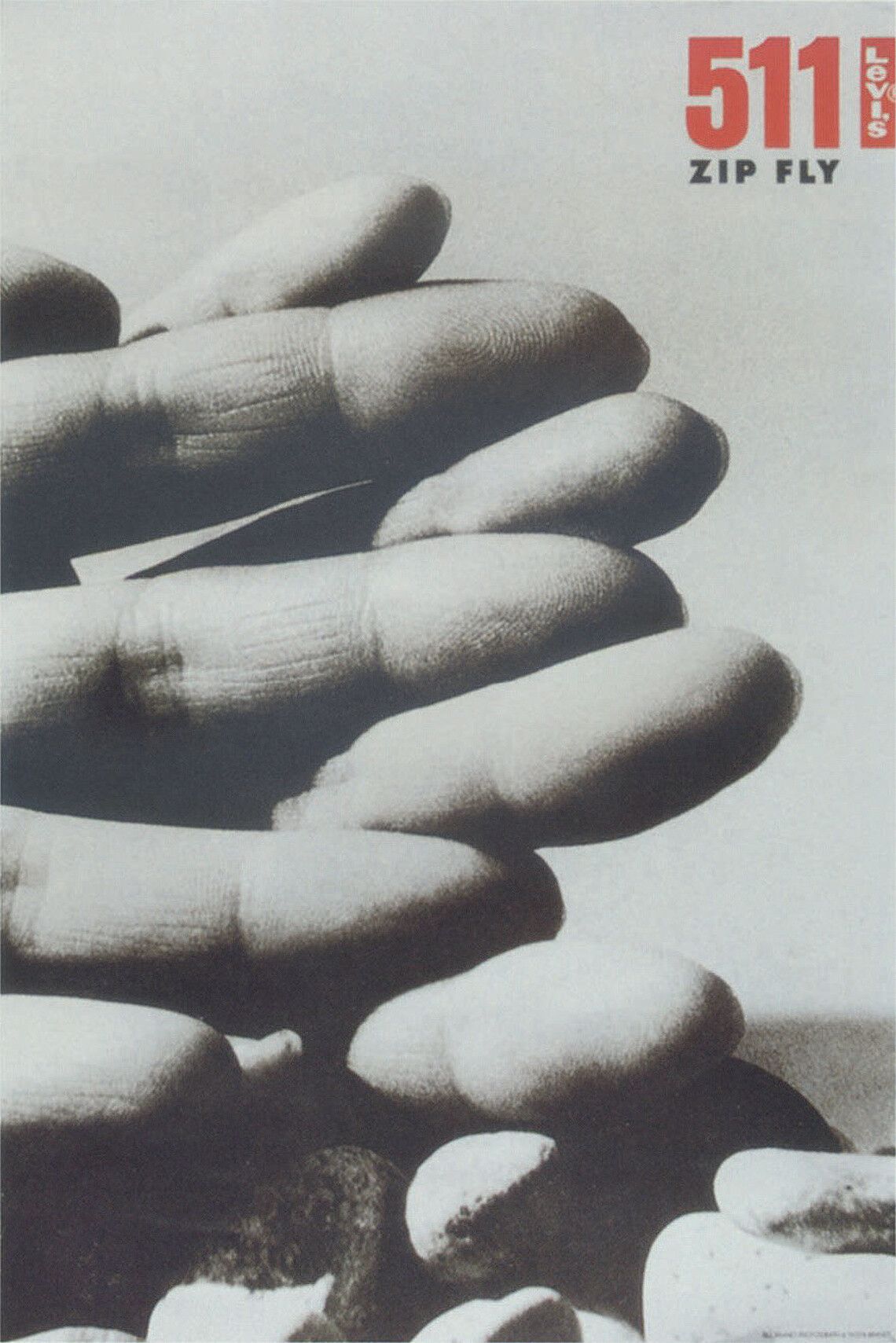

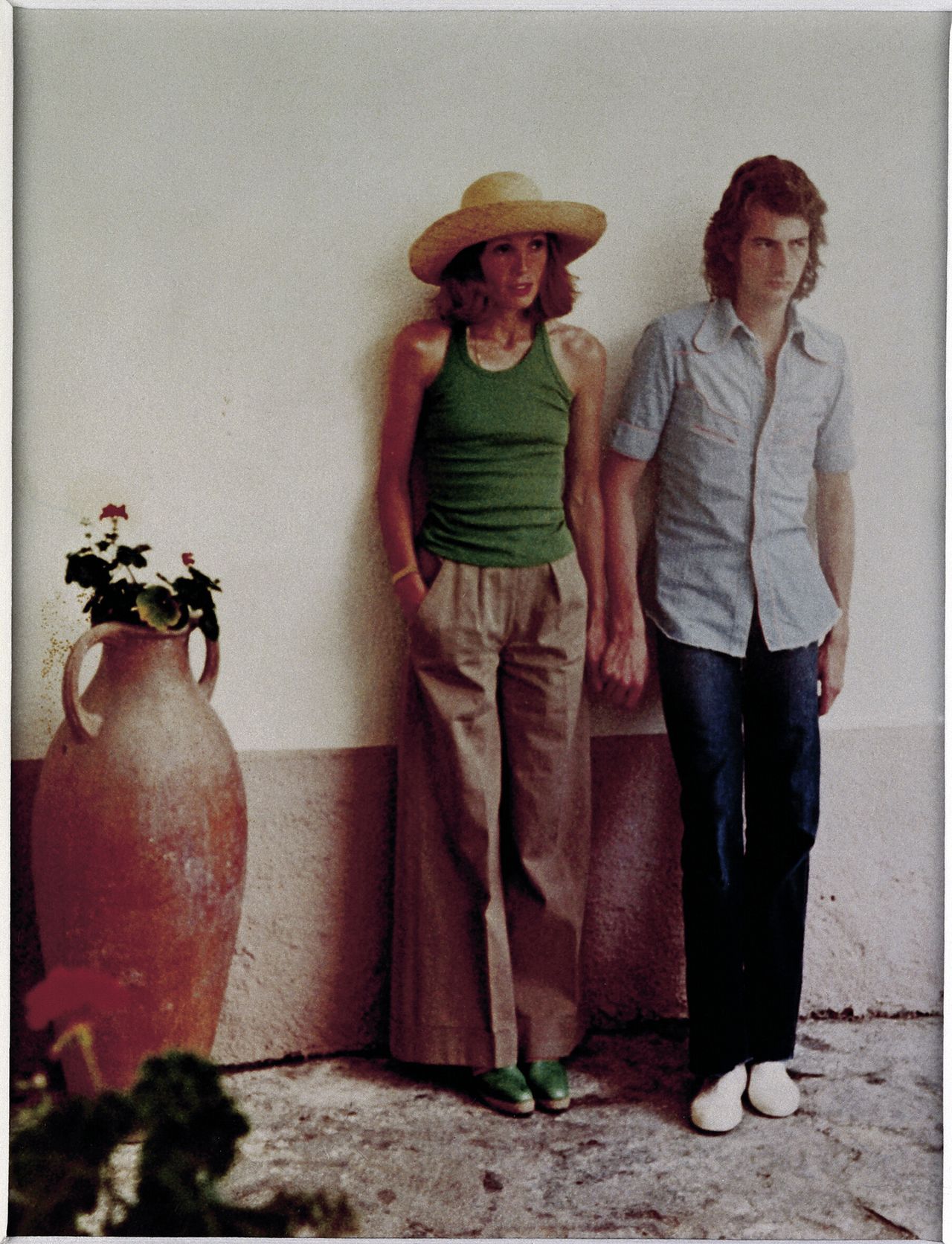

A 1982 Bogle, Bartle, and Hegarty ad for Levi’s. (Courtesy Luerzer's Archive)

SB: So this forward-looking—and the Financial Times has mentioned your “good-natured boyish enthusiasm.”

PS: Yeah, I think both of those are true. [Laughter] Hopefully you’ve seen that already today.

SB: And our friend Deyan Sudjic has written of the “private flamboyance with public sobriety” of your clothes, which is, I thought, a really interesting way of speaking to the visual charm that is the Paul Smith brand.

PS: Yeah, well, they’re all lovely things—thank you, all of you—but I’m interested in life. I’m interested in new ways of doing things, and I’m interested in communication. I’m interested in why, how. I suppose it’s childlike rather than childish. It’s the fact that you question, “I wonder why that bottle has got a dimple in it,” and then you realize it’s very sensible, because that’s exactly where your thumb and your first finger go to stop you dropping it. So there’s all sorts of just everyday observations that—things you notice.

I did walk down the street one day with John Hegarty from the Bartle Bogle Hegarty—in those days, the famous man who did the famous Levi adverts all those years ago. I walked down the street and, I don’t know what happened, I must’ve said something. He said, “You’d walk down the street and see fifty things. And I walk down the street and see six things.” And I said, “Wow, thanks a lot, John. That’s very complimentary.” And it hadn’t really occurred to me, but I do seem to see— You know, even just coming from the airport, I took two, three photographs out of the car window of big, not-used advertising, do you call them holdings? Billboards.

SB: Billboards.

PS: —that had been graffitied, and they had interesting graphics on them, and that’ll probably end up turning up as an element of a shirt print or on a window or something.

SB: I wanted to bring up mentorship here, just speaking about this current moment, because it does seem to be a big part of where your head’s at this moment and thinking not just about legacy, but about the next generation.

PS: Yeah.

SB: In 2020, you launched Paul Smith’s Foundation. I love the name, by the way, that it’s not The Paul Smith Foundation.

“I have no idea what I do, but it seems to be helpful.”

PS: It’s Paul Smith’s Foundation.

SB: Casual. And you launched this foundation in part as a way of passing down some of the knowledge you’ve gained along the way, whether it’s via the “&PaulSmith” program, in which you’re partnering with a young creative to help them further develop their career, or the just-launched fashion residency at Studio Smithfield, this twelve-month industry boot camp for six designers. Tell me about your vision and ambition for this.

PS: What I hadn’t realized, but was pointed out by members of my staff is that, for years and years and years, I’ve been advising, helping, talking to young designers or even entire school classes come age 8, 15, 20. I’ve got….

SB: Oxford University.

PS: Yeah, I mean they’ve got an Art Center, is it from Pasadena, is that Art Center?

SB: Yeah, Art Center.

PS: Yeah. They’ve come every April. Have done for years. I’ve got a group coming from Australia, they’re coming in May. There’s a school from the north of England, the Oakham School, they come every year. They’re 15 years of age. And then I suddenly realized that John Galliano came to see me when he was 21, or Alexander McQueen came. Many of the designers have come in saying, “What is a license? What is a contract?”

SB: Even Jony Ive has said you had a massive impact on him.

Smith (right) with the designer Henry Holland at Smithfield Studio. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

PS: Yes, that’s true. I knew him before he was at Apple. So I go back a long way with Jony.

I have no idea what I do, but it seems to be helpful. I had a group come from Vienna, and I showed them around the building and talked to them. And then at the end of an hour and a half, it was the end of the day, so I said, “Oh geez, let’s get some beers and drink and sit down.” Rather embarrassingly, one of the students, in front of the two tutors, said, “I’ve learned more in an hour and a half than I have in three years at college.” [Laughs]

And I was like, “Oh, oh, sorry about that,” to the tutors. [Laughs] But I don’t know, I think it’s probably because people…. It’s a very relaxed atmosphere where I work and maybe they feel that they can say, “I don’t really understand…. What is a franchise? I don’t know what that is.” And whereas to your tutor, you might be nervous to ask that question, because you think you should know or something. I don’t know really, no idea.

But if you please come to my room in London, which Deyan loves and I can’t get rid of him. A lot of visitors come and want to stay. It is full of just things that are sent from around the world all the time and amazing, generous, and ridiculously simple things. Real extremes, like, last Tuesday, a man arrived from Tokyo with a bike to give me, and then somebody arrived from the awful war in Ukraine, but a lady came on my birthday with a bike from Moscow, which was made in the year I was born—and didn’t even know I was going to be there in the building and went back to Moscow in the afternoon. It’s been just the most wonderful, amazing thing.

There’s a young lady from a provincial town in Belgium who’s now in her twenties, but she started writing me when she was 11, and she said, “I don’t like fashion, but I like you.” I’d never met her, so I don’t know even how she knew who I was. So these extraordinary things that just….

The debut of the Smithfield fashion residency program, established by Paul Smith’s Foundation in February 2024. (Photo: James O Jenkins. Courtesy Paul Smith)

SB: Gestures of connection.

PS: Yeah. And just the fact that they think they can send this, I mean, she sent me little things she just made, like little bits of ceramics. Yeah, Jony Ive, he stands in my office and he said, “How did this start?” And I say, “I have no idea, Jony. I have no idea.” This young lady sent me, for Christmas—when she was 11—this is a long time ago now. She sent me a nativity. She made the box, she wrote the letter by hand, and I opened the box—baby Jesus was a peanut—

SB: [Laughs]

PS: —and angel Gabriel was a peanut, and the three kings were peanuts. And so it was a peanut nativity that she’d made for me. I always just think, I wonder if she sent one to Mr. Armani or Tom Ford or something. Like, “I know, let’s send you a peanut nativity.” I’m not sure whether that would happen. I don’t really know.

Rabbit figurines that Smith has been sent in the mail. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

SB: One element of your collection that I find really entertaining are the bunny rabbits that have seemed to sprout up everywhere.

PS: That was a huge mistake because obviously what I should have said was diamonds, because I was on a train in the eighties with a friend from New York, actually, on a train traveling, and I was daydreaming looking out the window. He said, “Why are you looking so intently out of the window?” I said, “If I see a rabbit, my next collection will sell really well.” And I just made it up. And he came back to New York and sent me a rabbit, and he told somebody who told somebody, now I get between six and twenty rabbits a week. And so as I said, what I should have said was diamonds, I’m looking for diamonds—between six and twenty a week. That would be brilliant.

[Laughter]

Yeah, so we’ve got boxes and boxes of rabbits everywhere. Wooden ones, ceramic ones, rather beautiful ones, little kitsch ones. We’ve got one rabbit sender from Rimini who sends rabbits on a very regular basis. There’s certain fans from different countries. We’ve got one fan from Milan that just sends anything to do with packaging for fruit. [Laughs] So I get tissue paper that fruit was wrapped in. I get stickers that fruit was stuck to. I get the stickers from the end of fruit boxes. I get fruit-related mail. I’ve never met these people. Some of them….

SB: But they just have some profound connection to you that—

PS: Yeah. And what’s so delightful is that there’s never a demand, which I think in this “What’s in it for me?” world is really amazing, really amazing. It’s just so humbling.

SB: And you’ve used this humble medium of clothing to actually transfix and transform some of these people’s lives.

PS: Yes, yeah. Without knowing it, just probably the little sense of humor that, you open a jacket and you see that there’s a patterned lining or the sweater I’m wearing with a little hidden stripe at the back that you don’t see from the front. Just little things.

SB: Winks.

PS: Yeah.

SB: So you’re the boss, you’re the head of design, you’re the main shareholder, you’re the brand stylist.

PS: [Laughs]

SB: I like how you put it to Giorgio Armani a couple years ago—you told him that you’re “a down-to-earth boutique owner.” How do you view your role today within the company? Is there such a thing as an average day for Paul Smith? I can’t imagine.

PS: Not at all, no. No, luckily, there isn’t an average day at all. I suppose the hardest challenge, which I’ve never really worried about. It’s just the diversity of my job. I’m sure you know that I wanted to be a racing cyclist, and then had a bad crash at 17, nearly 18, and then ended up getting into fashion completely by chance: After coming out of hospital, I went to this pub, which was where all the art students went, and I thought, “I wonder if you could earn a living doing something interesting.” They used to talk about the Bauhaus, and I thought it was a housing estate near Nottingham. [Laughs] I didn’t realize, it was the iconic German school at the time.

So I suppose I never really think about my job at all. I just think, “Let’s try and work it out.” I didn’t really answer that question very well, sorry about that. I went off on a tangent.

SB: No, well, I think as I was going through, “Is there anything Paul does that would be a daily routine?” One that I came across, a consistent thing for you has been swimming at around five a.m. every day.

PS: That’s right, yeah.

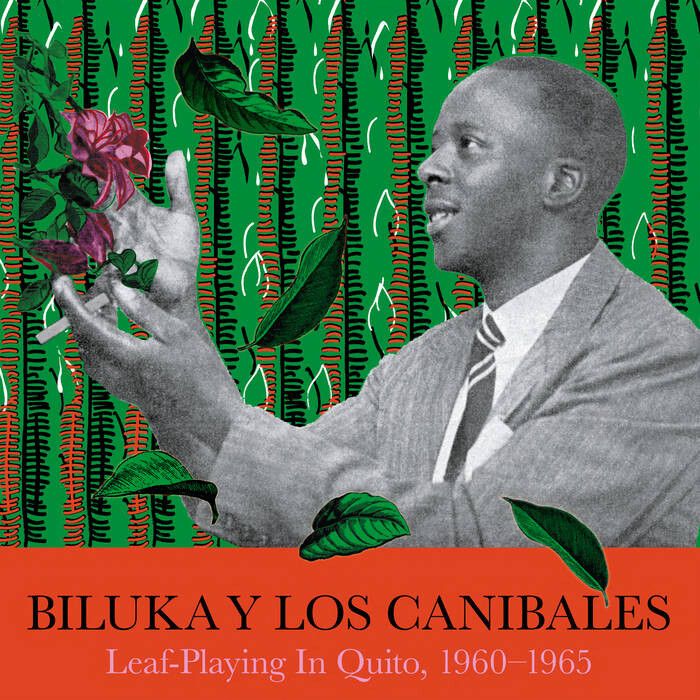

Leaf-Playing In Quito, 1960–1965 by Biluka y Los Canibales. (Courtesy Dilson de Souza)

SB: When did this ritual start, and what do you think that time in the pool does for you?

PS: [Laughs] 1992, and I swim more or less every day. Between 5 and 5:30. I don’t swim well—nobody ever taught me to swim—so I do the breaststroke, nicknamed “the swan” because of the way I swim. And then occasionally if I want to get my long hair wet, I’ll do the backstroke—well, it’s sort of a backstroke. But I do ten lengths if it’s a long pool, sometimes twenty lengths, sometimes half an hour. It’s never routine, but the routine is the fact that I do it. I find it opens up my body. Because I travel a lot. I was in Denmark for four hours on Friday and I’m here now, and it’s just one of those things where it opens your body up.

And then I get to work. Then the first thing I do, around six o’clock, I put some vinyl on. More recently, I’ve been listening to Thelonious Monk again and Herbie Hancock. And then I mostly write postcards to people that have sent me things for the first half an hour. And then normally my first member of staff comes at 7 or 7:30. Some of the early birds who like to work in the building before anybody arrives. I’ve got a new album I’m really excited about. It’s a man called Dilson de Souza, and he plays the leaf. So he’s a leaf-blower. He plays the eucalyptus leaf.

SB: Wow.

PS: He’s rather disappointed that he can only get five tunes out of one leaf. [Laughs] So I’ve been listening to that recently.

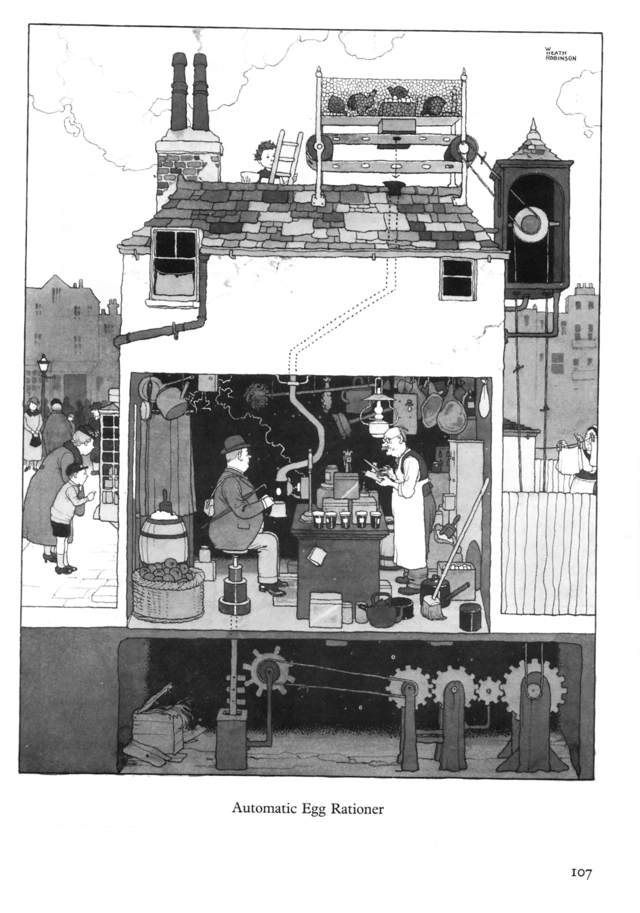

A page from the 1981 book William Heath Robinson Inventions. (Courtesy William Heath Robinson)

SB: Leaf-blowing, fascinating.

Let’s go back to your upbringing in Nottingham. You were the youngest of three children by eight years. Your father, Harold Smith, was a credit draper, and I think perhaps more importantly in your life story, a passionate amateur photographer and co-founder of a camera club. And when you were 11, he gave you these two life-changing gifts.

PS: Yes.

SB: He gave you a camera and a pale-blue Paramount bicycle. Let’s start with the camera. Looking back now, how do you think about how taking pictures has transformed your life? Even listening to you talk about the pictures you took on the way from the airport today—there’s your dad’s impact.

PS: A Kodak Retinette camera with his Zeiss lens. He built a darkroom in the attic of our house. And my father—are you familiar with Heath Robinson?

SB: No.

PS: Heath Robinson was this completely mad inventor, and I’m sure my father was Heath Robinson number two. So the ladder to get into the attic was held by a piece of rope and a weight made out of a paint tin and filled with lead…. There were all sorts of mad things. And so what was amazing about the camera was the fact that you have—if we talk in inches—you have a quarter of an inch of a viewfinder or one or two centimeters, this tiny little hole where your viewfinder, where you look through to get your shot, what you’re going to look at…. And of course, it was film, so it was pocket money. It was a roll of twelve. You didn’t see the photograph until you finished the roll and you developed it, so every shot was precious.

And now, of course, we take twenty pictures at a time with our camera, which is a phone, and then delete them. The thing was, looking through this little gap, and it taught me to look and see, which never had occurred to me before. If I was taking a picture of you now, I’d know that if I was slightly to the left, it would be the chair and the desk, and if it was to the right, it would be the other chair and the desk. In fact, if I carefully look, I’d get you and the microphone. That was a big, big, fantastic thing. And then doing the developing and printing, I’m just about to show you, this is the red light from the darkroom.

“Looking through the little gap [of a camera’s viewfinder], it taught me to look and see.”

SB: Oh, wow.

PS: That was the homage to my dad.

SB: On the back of a watch Paul has handed me [looks at an illustration of a red light on the reverse side of Paul’s watch].

PS: So it’s a Paul Smith watch, and it’s got a bulb, red bulb, which is what we used to have in the darkroom so you could develop and print. And my father, the other thing I learned from him was humor. He was a great communicator, but also he worked. I came home from school one day and in the garden there was the white sheet from my parents’ bed on a washing line, and then three fruit boxes with a rug on top of them that was wired at the edge.

And he said, “Oh, before you do your homework, just sit on the rug and pretend you’re flying.” I was like, “Dad, I’ve got my—” “It won’t take a minute. It won’t take a minute.” So I sat there, age 11 or something, cross-legged with my arms lifted up as though I was on a flying carpet. And three weeks later or something, he showed me this photograph of the famous Brighton Pavilion in the south of England with its onion-shaped top to it—it looked like it was from the Orient or somewhere—and I was flying across this pavilion on a rug. And of course he’d taken the two negatives and put them together. So that was mind-blowing.

And then the Paramount bike was a second-hand bicycle bought from a man from the camera club. And he said, “If Paul ever wants to join the local cycle club”—called the Beeston Road Club—“he’d be welcome.” And if you want to come out at the weekend with the club members, there’s normally about twenty of us. We’ll make sure we take care of him.” So at the age of 12, I started doing that, and then that same year I started racing and realized that I liked the camaraderie of racing. That helped me in my business, definitely, about playing to strengths and weaknesses. The day you’re on a mountain, you help the mountain climber and the day you’re on the flat, you help the sprinter. And so with one thousand six hundred staff, you understand people’s strengths and weaknesses and use them accordingly.

SB: I imagine cycling gear must have been an interesting thing for you, too. Obviously this notion of maybe one of your earliest deep engagements with hardware design.

PS: Yes. I used to keep the bike in the bedroom, and I’d worship it every night and make sure it was always clean. But I loved all the detail of the way the frame was welded, and—they call them lugs, the way they joined together, whether they were hand-painted or not. And then the famous Campagnolo Italian gears and chain set and just saving up pocket money to get them because I hadn’t got them on the original bike.

SB: All the individual parts that create the whole.

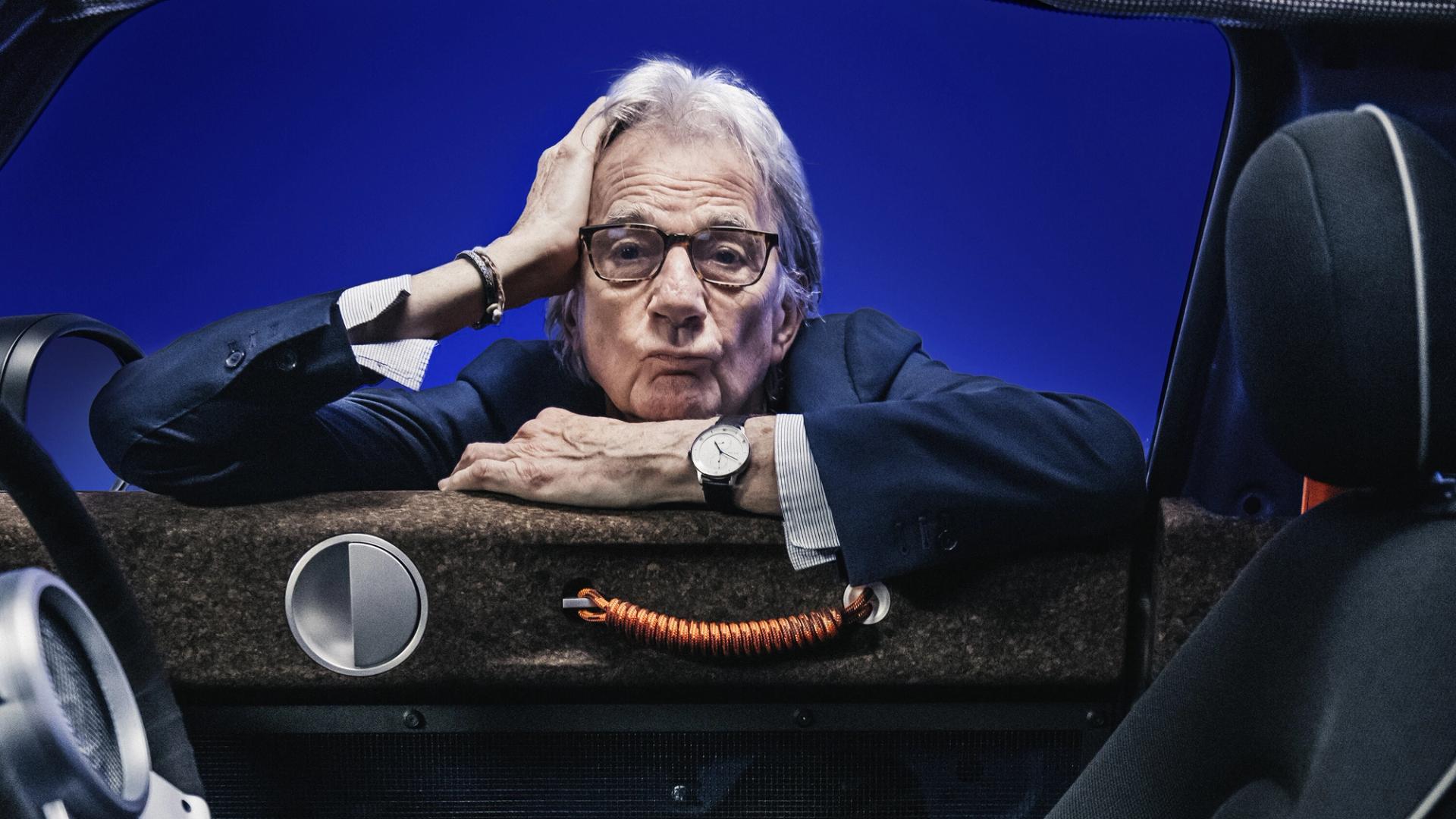

PS: Yes, that’s right. And building the bike of your choice, which was very interesting. Years later, recently, I think two, three years ago, I designed a one-off mini car. The main point of the car was sustainability. But a lot of the points of the car I did were where you could actually take bits off the car yourself—because most of the fixings of cars these days are on the inside.

But I put the fixing on the outside of this one-off concept car. When I realized, years later, that it was really to do with building your own bike and almost like building your own car, something linked there somewhere.

Smith with his design for the Mini Strip in 2021. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

SB: You mentioned it earlier, but I feel like the way you talked about it seemed almost casual, this terrible bike accident you found yourself in at 17. You were in the hospital for, from what I understand, close to six months?

Smith cycling in his youth. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

PS: Yeah. Now they would repair you a lot quicker. I know most of the professional cyclists now, and one of them, Mark Cavendish, he’s broken his collarbone three times. I broke it once. He broke his femur, now he’s got stainless steel in there or something like that—whereas when I did it, it was just a slow process. But it was an interesting time and I think I grew up a lot then as well, because I came from an area where there was a lot of coal miners, so a lot of the accidents, a lot of the patients were coal miners and there were like sixteen people who died while I was in the hospital over a period of time. And so it was a real sort of growing up.

SB: But in this sort of roundabout way, it was through cycling and then this accident and your time in the hospital that you met people that led you to a pub.

PS: Exactly.

SB: So these people you meet in the hospital take you to a pub.

Smith in a cycling uniform as a young man. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

PS: Yeah, two of the people. We all got let out at the same time. And one of them said, “Why don’t we meet? We all got on so well.” Because we used to shout to each other across the ward, like, “Morning, how are you?” Yeah, they used to call me the “praying mantis” because I developed a skill of using my right leg with a spoon in it to be able to feed myself with this long leg of mine.

And so I think I was the court jester, or the ward jester. And then they suggested we go to this pub called the Bell Inn in Nottingham, and completely by chance it was the pub where all the art students went. And so all this language— Kandinsky. Who? What is Kandinsky or the Bauhaus or Andy Warhol, pop art? These are mind-blowing things. What are they? Can you ever earn a living doing something…?

SB: It almost seems foretold. You see the stripes and the colors of Paul Smith and it’s all there.

PS: Yeah, the joy of everything, of seeing the colors from a Kandinsky or Oskar Kokoschka painting, things like that. And I’ve always been blessed, I think, from my dad, to have a way of being able to communicate in a quite relaxed way. So I soon got to know a lot of the students from the pub and ended up working for one of them for a few years, just helping her run a shop that her father was sponsoring for her.

SB: Of course, this led to your introduction to Pauline [Denyer], your now wife, who was a fashion graduate of the Royal College of Art—first became your girlfriend, then business partner, then designer, and then wife. Speak a bit about her impact on Paul Smith.

Smith (left) with his wife, Pauline Denyer. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

“I would say, without being too humble, that I probably wouldn’t be sitting here without my wife’s influence.”

PS: Enormous impact. Enormous impact. In fact, I would say, without being too humble, that I probably wouldn’t be sitting here without her influence because she went to the Royal College at a time when they were still teaching couture fashion. That’s very much about how things are made…. She used to talk in these strange terms, almost talking about architectural terms, like the proportion of the pockets and the opening of the rise of the trouser or the opening of the jacket. She would talk about [Andrea] Palladio and I’d have no idea what she was talking about—the perfect proportion that Palladio did with these buildings—and then the perfect proportion of two pockets sitting on the side of a jacket, and then how they were made and what pad stitching was and what a dart did.

What does a dart do? A dart creates fullness at the end when it finishes, and that’s how you get the piece that goes over your chest. And then, of course, she was there with [David] Hockney, Peter Blake, a lot of those, Joe Tilson, all those pop artists… a very important time at the Royal College as well, because she’s a bit older than me. She came to Nottingham to live with me, and I was living at home with my parents, still. It was fairly mind-blowing. Two dogs, two cats, two kids, and a lady from London, aged 21.

Smith (right) with his wife, Pauline Denyer. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

SB: Right, she had brought two kids from a previous….

PS: Yeah, she was married with, I think they were 5 and 7 or 6 and 8, something like that.

SB: And you’re 21 at the time?

PS: Yeah. So I got instant family. Two Afghan hounds—and I looked exactly like an Afghan hound. [Laughter] And two long-haired cats, two-long haired kids, and suddenly renting an apartment and having to suddenly worry about how am I going to afford to keep— Luckily, she was earning quite good money. We lived together for many, many years. And then she said, “I’ve got to go and live back in London.” She’s a Londoner. She was famously at the Hammersmith Art School, aged 15, and I think she’s still the youngest person ever to go to the Royal College. And she was at Hammersmith Art School with Michael Chow.

SB: Wow.

PS: Yes. And so there was this sort of connection with a very interesting time in London. And then we both moved, in her case, back to London. Then I moved to London, and it was good. And then eventually she said she wanted to get married. And so we got married and, completely by chance, it turned out that I got knighted on the same day, which was not planned at all.

SB: This was in 2000, right? Yeah.

PS: Yeah. I got knighted in the morning. She became a Lady [laughs], and then got married in the afternoon, and then a party at the Tate Modern in the evening. It was a busy day. [Laughter]

SB: Speaking of Nottingham, I just want to touch on that because it’s really the roots of the brand. It’s your roots. You opened the first shop in 1970, just two days a week, but it was open. And then in 1974, you incorporated the company, which I guess could be another major milestone this year.

PS: Yeah, that’s— Absolutely.

SB: Fifty years. And opened your first full-fledged Paul Smith shop, also in Nottingham, but it was your first London shop that I think really kind of brought the awareness. And this was in 1979 at 44 Floral Street in Covent Garden. I wanted to bring up this Floral Street space because it’s quite remarkable. It’s a compound, really.

Smith in his first store in 1979. (Photo: Stuart Harrison. Courtesy Paul Smith)

PS: Deyan wrote very nicely about it for Design Week, I think it was called. He said there was no other shop like it. It was a concrete shell with…. The first minimal shop in England, as far as I know. It was quite a few years later when the Japanese came to Europe in the eighties, ’82, ’83, but it was very minimal. It was done with a friend of mine from the Slade School of Art, who was a sculptor. He and I loved Mies van der Rohe, the Bauhaus, Corbusier. And the dream was: shutter-board, concrete staircase. Because I’d bought the building in ’76, all on borrowed money, and then couldn’t afford to do anything to it. I’d never been inside.

But I bought it by looking at it from the outside, from a retired baker whom I’d never met, who was very kind because he indirectly lent me the money to buy it. And then when I eventually went inside, I realized that it didn’t have a staircase, but it had four floors, and it had a goods lift for bananas—not even a lift that you could stand in. It was just for boxes of fruit. So the process was long, but it was fantastic in the end. I think that was really the key to knowing people like Deyan Sudjic, Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Vico Magistretti.

SB: It built a community around the….

PS: Yeah. All came to this shop, John Hegarty and a lot of the Saatchis, Jack Nicholson, Harrison Ford, all those people just came to…. And it was tiny, the shop, tiny, tiny, tiny shop, three hundred square feet, on the ground floor. But it was just so modern and so different. And also it tied in with me going to Japan for the first time. So I’d bring back these amazing things like matte black watches and matte black cigarette lighters and a watch that was a robot and was used to talk.

The Braun ET66 calculator, first designed by Dieter Rams in 1981. (Courtesy Braun)

And then on top of that, I managed to get to know Dieter Rams, and I was the first person to stock the Braun calculator. There was the Braun calculator, a matte black watch, a pen that looked like— I got the pens from the Pompidou Center, which has the famous ventilation…. The pen was like the ventilation shaft that curved at the top. My little shop attracted all these people who adored design.

SB: And now you have shops in more than seventy countries around the world, from New York to Los Angeles to Paris and Hong Kong. You’ve said, “Our business was built very gently and very slowly.”

PS: Yeah.

SB: So I was curious because obviously from that first Floral Street shop to now, it’s quite a journey. What would you say has been your philosophy, if there is one, on scale and growth—day by day, month by month, year by year?

PS: The main thing is that Pauline and I started the business when I was 21 because we thought it might be a nice way to earn a living, and that was it. So it’s never been, really, about money and expansion. Of course we’ve been offered— And now that I’m 77, maybe I will think about letting somebody buy into it or something. Because you can’t be around forever, but we’ve never been attracted by any of that at all. But as you get to a certain age, you think, “Well, maybe it’s the time to take care of the younger staff and do something like that.”

But it’s never been a business that’s been motivated by money. It’s been motivated by having a great day and really enjoying it. And just, over the years, I’ve just met so many interesting people, a wonderful mix of people, from the King down to a few kings and lots of film stars.

“It’s never been a business that’s been motivated by money. It’s been motivated by having a great day and really enjoying it.”

SB: And also just all the collaborations. It’s seeing your brand extended beyond clothes and to Maharam textiles, Mini cars, Burton snowboards, the outfits you’ve done for Manchester United Football Club.

PS: Yeah, we’re working with The [Rolling] Stones at the moment, for instance. I designed a new album cover for The Stones recently. The main cover was designed, but then they asked me to do just two thousand of one special one.

SB: Paul Smith edition.

PS: Which sold out in, like, two hours or something. I like to do things that scare me a bit. Suddenly doing something that takes a lot longer, that the set-up charge is a lot more expensive, that the way of approaching it is more complicated….

SB: You’ve even done a hotel suite at Brown’s Hotel.

PS: Yes. Yeah, with a banana handle.

SB: Yeah, on the door.

PS: Yeah, the door handle’s made out of a bronze banana, which—we actually took a banana to the casting place. [Laughs] I don’t think we’d had a job like that before.

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

The Sir Paul Smith Suite at Brown’s Hotel in London, designed by Smith in 2023. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

Paul Smith’s “Perspective” textile collection created in collaboration with Maharam. (Courtesy Maharam)

SB: Well, to finish, I’d like to end on two subjects, one that you touched on, which was humor, and the other being music. But let’s start with music first. You’ve got this big vinyl collection in your office, and musicians have long been tied to you and the brand, whether it’s David Bowie or Patti Smith. Even at age 18, I read that you were making clothes for Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page.

PS: Yeah, I think Jimmy was 19, I was 18. He was 24-inch waist, and the bottom of the trousers were 28-inch. So you can imagine they were very flared. They were in panne velvet. I recently went to his home to see his—because he’s got all his collection of clothes still, and I was pleased to find a Paul Smith shirt there, which was nice. And Clapton and, oh, many of them.

SB: What do you make of the music connection to the brand? Why do you think it’s so tied?

PS: I don’t know, really. I mean, David Bowie became quite a good pal, and we did a T-shirt to go with the final Blackstar album, which was launched literally a week before he passed away. And he used to come to my studio and say, “Why have you got that book, Smithy? Why have you got that? Why have you got seventy books? What’s in that book?” He was always fascinated.

A T-shirt Smith designed for David Bowie’s Blackstar album in 2016. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

Patti Smith loved coming to my office to see all the amazing things. “It’s really full of stuff, very, very eclectic.” And Dieter Rams, David Chipperfield, and John Pawson have all been there and didn’t die of a heart attack. [Laughter] I think that’s amazing because it’s so opposite to their concept. [Laughter] Dieter came and he was like, “Wow, can I look around?” I said, “Sure, sure.” And I thought he’s just going to go “Oh!” and pass out, but he didn’t.

SB: It’s a maximalist shrine.

PS: Yeah. The music world— I’ve just been close to, from the Rod Stewarts in the early days to The Stones—we’re still working with The Stones now. Different bands like The Lumineers and… very varied. I sold my house to Van Morrison.

SB: Oh, wow.

PS: [Laughs] Which was funny. I managed to get to meet him because he couldn’t switch the heating on, so I felt, “I’ll go around and fix it.” There was nothing wrong, it was just a switch. That way I got to meet him.

SB: He was one of your Desert Island Discs.

PS: Yeah, he was. He came to one of my shows as well. “Astral Weeks.” A lot of the songs on Desert Island Discs were just—First of all, I chose them very spontaneously, because I think so many people labor too long on them, and I’d just done them really quickly. They’re very of a particular point of time as well, like “Layla” with Eric Clapton, and Bono [U2’s “Even Better Than The Real Thing”], “Imagine” by John Lennon. But I used to travel the world, which I did today actually, on my own a lot. I went to Japan a hundred times, almost every time on my own. So in those early days with a Walkman, those songs would get you through the trip when you woke up at all the wrong times and you’d put Astral Weeks on and you were just—

“In those early days with a Walkman, those songs would get you through the trip when you woke up at all the wrong times and you’d put Astral Weeks on. It just felt good.”

SB: Alright.

PS: It felt good. Yeah, it felt very nice.

SB: And then humor, of course, has probably been a big tool for getting you through it.

PS: I had a complaint, though, recently, from one of the girls at work. She said, “The only problem about working for you is I get a stomach ache with laughter.” I figured that was probably a good complaint. [Laughs] I think I’ve got the humor from my dad, actually. He was very spontaneous and quick with humor, and a very nice person.

SB: Yeah. You’ve said that you’ve been able to survive in business for so long, partly because of this humor. And I just think it’s worth mentioning for those who don’t know these stories, that you almost famously—or infamously—would bring, like, a rubber chicken into a meeting, or you’d have a briefcase with a model train set in it. And these were things like—business is tough, meetings can get tense, you gotta loosen the mood.

PS: Yeah. In Japan at four o’clock in the afternoon, which was, as you can imagine, eight hours different, so it’s the middle of the night to you. “Paul-san, only one more meeting.” And I’d just lean down into my bag and go, “Ahhh!” and bring out the rubber chicken. And they’re squeaking and they all go [gasps] like this. And I said, “Only joking. Okay, come on, let’s get on with the meeting.”

Smith as a child with his father. (Courtesy Paul Smith)

And then my wife got this amazing—it’s a really pretty dreadful suitcase made out of metal. She got it made in Germany, and it’s got a real model train set. So I used to just, they’d say, “Only one more meeting.” I’d say, “Oh, no, no, no, I’m going to play with my train set.” And I’d bring the suitcase, open the lid, and they would be going [gasp]…. [Laughs] They were so astounded. And then the next time they’d say, “Where is the train set?” [Laughs] They’d missed it because I hadn’t brought it. I was always in trouble.

SB: Clearly, humor is literally in your DNA because of your father, but I think also through gimmicks or….

PS: Humor is very much about timing and understanding the correct moments. So in Japan and on those two occasions I mentioned, it was definitely okay because I’d put my work in, I’d worked hard, and it was a good time to do it. My father taught me always just when to get it right for the humor.

SB: Yeah. And it makes me think about your brand and so many of your clothes, which is sort of this rigorous tailoring, the sort of seriousness, but then a letting go.

PS: Yes. And how you put it together. During Covid, a lot of people stopped wearing suits because they were just at home. But now, people are still buying our suits, not in the same quantity yet, but they probably will. But you put them with a chambray shirt, you put them with some sneakers, or you wear the jacket on its own with some blue jeans.

So it’s the way you put it together. Don’t take yourself too seriously. When I started, suits were to do with funerals, weddings, job interviews. And then in the eighties, I managed to put some color in there. David, Mr. Bowie, started buying suits, not for stage, but for his personal use, and they had just a little bit of color in them. They were just a bit different, slightly bigger shoulders, softer construction, and just more relaxed, really.

SB: I guess just to finish, how do you view humor in the Paul Smith brand yourself?

PS: [Laughs] Well, I think the thing is that humor is very much about spontaneity, I think, and secrets, as well, with the clothes. The fact that you know there is a different-colored cuff hiding under your shirt—in terms of business, you look fine, you’re very acceptable—but there’s this little secret. I always remember selling to Jean-Luc Godard, the film director, and getting into France in the seventies when they had a very cliché look: It was the leather jacket, the roll-neck, all the classic suits, just selling something to him that just had something hidden. I can’t even remember what it was now. I think it was a blazer, just a navy blue blazer. But when you opened it up, it had a brightly colored pocket or something. I always call it a nudge rather than a shove.

SB: I like that. Paul, thank you so much for joining me today.

PS: You’re welcome. Well, it’s lovely. So nice to talk to you. And unfortunately, I could bore you for hours and hours and hours with jokes and anecdotes and stories, but time is up.

SB: [Laughs] A good way to end. Thanks.

This interview was recorded in the Paul Smith New York City showroom on March 5, 2024. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo based on a photograph by Matt Healy.