Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Deborah Needleman.

SPENCER BAILEY: Joining me in the studio today is the writer, editor, and craftsperson Deborah Needleman. Welcome, Deborah.

DEBORAH NEEDLEMAN: Thank you, Spencer.

SB: I wanted to begin with a specific period of time, which is the past five years. At the end of 2016, after twenty years as an editor for design and fashion magazines—T, WSJ., Domino—you turned your time to really be devoted toward crafts, such as herbal tea–making, broom-making, basket-weaving. What spurred this shift in you and slowdown for you?

DN: I guess it is a slowdown. In some ways, it seems like a radical shift in my day-to-day life, but in other ways it seems like it was all sort of leading that way. But I think, in part, it was this idea of time, of like, okay, time is limited. How do you want to spend your time? How have I been spending my time? And not in a maudlin way, but I’m in, if I’m lucky, the final third of my life, and…. There are a lot of things that went into it, and in part it was just this idea of, I want freedom. I want to be able to make up my own day, every day. I want to be able to research things, learn new things.

Because I was thinking about this before going on the show, and I usually answer this question in terms of basketry, but I think a big part of it was also wanting to tend to the important relationships in my life better. And when you’re super busy, you can’t do that. Although, as my children like to point out, I became a stay-at-home mom when they left the house, so actually my timing was good. But in other ways, it was like I just wanted a new chapter. Editing and writing is all in your head, and I wanted to do something more physical. I wanted to live more in tune with the seasons. I was done, as weird as that sounds.

“Editing and writing is all in your head, and I wanted to do something more physical. I wanted to live more in tune with the seasons.”

SB: Yeah. And there’s something to this that makes me think about this idea of, like, tending.

DN: Of what?

SB: Tending.

DN: Yes.

SB: Tending to a garden, tending to relationships, tending to—

DN: Yeah. I hadn’t thought about that, but yes. And I think it was sort of tending to myself. As a magazine editor, what I loved was this idea of being able to celebrate other people and people—the way you do on the show—to create a platform where ideas and creative output and people’s work that I think is incredible, to create an outlet for that and to celebrate other people. And I got to a point where I just wanted to do my own thing. I also think, as an introvert, I had had enough of an extroverted life for a lifetime, and I wanted solitude. I wanted to do things on my own and to be responsible for what I make and what I do just myself.

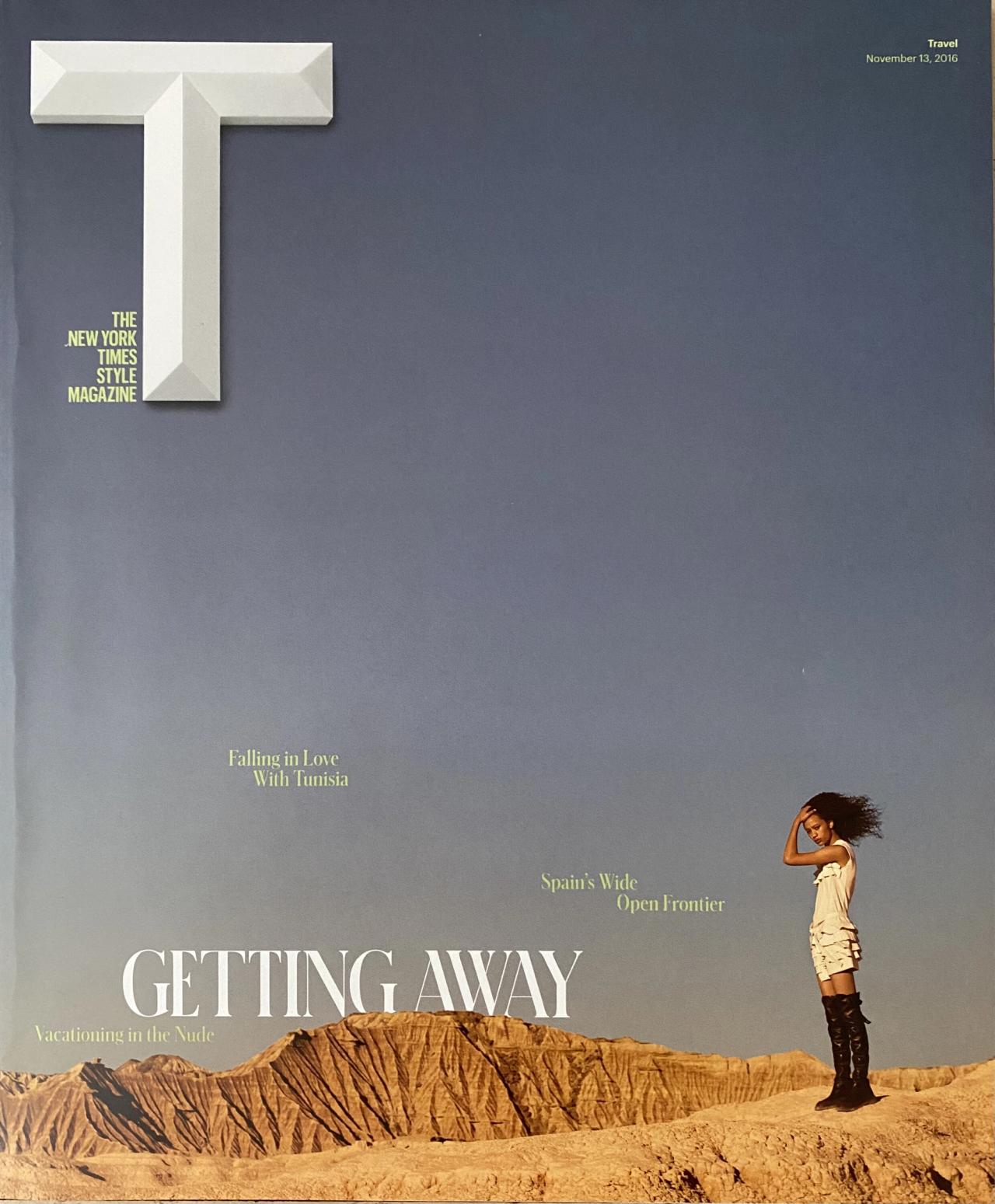

Cover of T magazine‘s Nov. 13, 2016, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: It made me smile when I was researching for this interview that—I don’t know if it was your last issue—but that the cover line of the November 13, 2016, issue was “Getting Away.”

DN: So that was November. My last issue: When I left my job—so my last job was at T, at The New York Times—and when I was thinking about leaving…. I’m not very organized and I don’t plan well, and I’ve never had any sort of career plan or path, but I was very organized about leaving, because I just didn’t want to have regret—that seemed like not a good way to live, and so I was very organized. There was a final issue that I did that I knew I really wanted to do, but I don’t think that was it. [Editor’s note: Needleman’s final issue of T as editor-in-chief, dated December 4, 2016, featured the actor Isabelle Huppert on the cover with the headline “Enduring Allure.”]

SB: Yeah, I still appreciate it.

DN: But yeah, I’m sure you’re right.

SB: In the lead-up, too, I was like, “Oh, I’m getting away.” Subtle wink.

[Laughter]

DN: No, no, I’m sure you’re reading my subconscious very clearly.

SB: But you planned this well in advance and with time on your side.

DN: Yeah, it’s the only thing that I’ve ever done in that organized way. But I thought about it for about a year, and even, like, charts and lists and “what will I miss?” I really wanted to kind of leave it all, I guess in a clean way, but just so that I was really mentally prepared for really changing my life.

Needleman with photographer William Eggleston in 2016 at a T magazine event at the Carlyle Hotel. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: The week after you left your job at T you went to take a workshop at the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, North Carolina.

DN: [Laughs]

SB: Where they teach and preserve the folk arts of the Appalachian Mountains. Tell me about this experience. And also, I have to mention that there probably isn’t a place farther afield from The New York Times Building as—

DN: It gets farther afield than that, because the week that I left and the week that I was in Brasstown, which they would say, it’s nowhere. It’s exquisitely beautiful, but I was meant to be at the couture shows in Paris being driven around in a black car and staying at a fancy hotel where they knew my name and they saved my things from one time to the next. It was crazy. So it was really, really different. And there was a moment of kind of culture shock when I got there. It was a place where every day started with music and song and banjo playing and storytelling—it’s very communal—and clog dancing. But quickly, I went from quite…. First, sitting in this room with all these people, it sounds horrible to say, but I was like, “Oh, my God, everyone has gray hair.” And then you realize people in New York don’t really get old, for the most part, because they are mitigating it all the time. But it was an incredible experience. That place, I would recommend it to anyone. It is an incredible craft school, unlike something like Haystack [Mountain School of Crafts], which is quite professional and [for] professional artists. It’s really about process.

Brooms crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s broom-making equipment. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Brooms crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A broom crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A broom crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Brooms crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s broom-making equipment. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Brooms crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A broom crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A broom crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Brooms crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s broom-making equipment. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Brooms crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A broom crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A broom crafted by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

And I went there. I wanted to do a basketry course and they didn’t have one when I wanted to go so I just ended up doing a broom-making course thinking, “Okay. Well, that’s also making something with natural materials.” And it was just the most incredible experience, to just be in a group of people, all from different backgrounds, all there for different reasons, and all being engaged in the same activity. There’s a reason why there were quilting circles. There’s something incredibly nice about learning with other people, but making with other people. And it’s also quite leveling. There was this intimacy when you’re focused on making, where people were saying things quite personal and revealing. It was just a really great human experience, if that makes any sense.

The dining room of Da Giacomo in Milan. (Courtesy Da Giacomo)

SB: I actually appreciated that your first piece for T, after departing as editor-in-chief, was on Giacomo Bulleri, of the restaurant Da Giacomo, in Milan.

DN: Oh, yes, yes, yes.

SB: Which is one of the most beautiful rooms and refreshingly unfussy restaurants I’ve ever eaten in. In a way, I kind of saw that piece as a celebration of tradition, taste, culture, community—all these things that are an apt or a subtle hint almost at where your focus was turning. This new craft focus.

DN: It’s true. Da Giacomo is one of the most beautiful restaurants in Milan, but his trajectory from the south and his father packed him up at 11 to move north to make money…. So he was probably in his late 80s when I interviewed him, and I don’t think he’s alive anymore. But how the women prepared food and it was all day long, they were in the kitchen prepping and then cooking and then cleaning up and then it would be time for another meal. But yes, I do think, despite all these disparate things that I’m interested in, I do think they’re all related, and food and culture and the land and hard work and the idea of this very rurally based food in such a beautiful, beautiful environment.

SB: Yeah. That was a challenge for organizing this interview. There is a kaleidoscope of interests that you have.

“Part of it is this idea of freedom, of just being able to, at this stage in my life, dive as deeply into one thing and then move on, or not.”

DN: Yeah. It does seem sort of schizophrenic, but I think it is all about connection and making connections between these different disciplines and things that interest me. And also, I guess part of it is this idea of freedom, of just being able to, at this stage in my life, dive as deeply into one thing and then move on, or not.

SB: I appreciate—

DN: So yeah, sorry about that, that must have been some really chaotic Googling.

[Laughter]

SB: Well, I appreciate also that if there is a central undertow, it’s literally this idea of cultivation, which connects directly to gardening, which is really where a lot of your early work was. It’s something you’ve practiced and written about for a long time now, gardening. Philosophically, how do you think about your own relationship with gardening, with writing about gardening, and, I guess more broadly, the relationship between gardening and time?

DN: Wow. That’s a big question.

SB: Yeah. Three-parter. [Laughs]

“For me, gardening is all about time.”

DN: And it’s a really good question. For me, gardening is all about time, in a way. As with basketry, I think I first got interested in gardening in an intellectual way. I read about it, and I thought about it. It seemed so alluring. And then I thought, Am I really going to want to do this if I spend all my time? And so I started gardening probably, I don’t know, thirty years ago. And then I got away from it when I was super busy in journalism, in magazine-making, but it always seemed sort of absurd. Like you’re fighting against nature in a way, but maybe not—it’s a dialogue. But for me, it always was this sense of, I don’t have a good memory, I’m not good at remembering dates and time. There’s something about how time is moving and the seasons are changing, regardless of whether you’re involved in it or not. It’s all going on around you. And so the idea of sort of wedging myself into that process, I find really alluring. The cycles of nature, it’s a huge thing, and that you can get a tiny, tiny foothold, I find incredibly satisfying. And again, it’s making things with creating space and trying to create beauty out of the materials of nature, which is a real throughline with the craft and the basket-making.

SB: There’s also this element, which you touched on in this New York Times book review in 2013, where you talked about how “in the garden, we play out fantasies, desires, and longings.” And it is, as you said, this sort of “tussle with nature.”

DN: Yes.

SB: There’s even a line in that review where you wrote, “Like sex, quite a lot of gardening happens in the mind.”

A rush bread basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A willow basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A willow basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Rush baskets made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A basket made by Needleman out of foraged sticks. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Willow baskets made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush bread basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A willow basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A willow basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Rush baskets made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A basket made by Needleman out of foraged sticks. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Willow baskets made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush bread basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A willow basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A willow basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Rush baskets made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A basket made by Needleman out of foraged sticks. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

A rush basket made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Willow baskets made by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

“You can look at a basket and it can be interesting or not interesting, but the more you think about it and the more you learn about something, the richer it becomes.”

DN: [Laughs] God, I don’t remember that at all. But it’s true! And that’s interesting because I do think a lot of what is interesting is the way one thinks about it. You can look at a basket and it can be interesting or not interesting, but the more you think about it and the more you learn about something, the richer it becomes.

SB: And you keep a garden at your house in upstate New York, which you and your husband purchased in 1995.

DN: Oh, my God.

SB: Tell me about your garden.

DN: How long have I been married? Do you know? I don’t. Go ahead, sorry.

[Laughter]

SB: Tell me about your garden there. How do you think about the evolution of this garden? What has been your approach to it over time? And obviously you’ve been able to put a lot more time toward it in the past few years.

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Needleman’s garden in upstate New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

“The first time I heard the term ‘landscape architecture,’ it was like a light bulb went off.”

DN: It’s interesting. So I grew up in suburban New Jersey. There were no gardens to speak of. [It was a] very cookie-cutter, suburban development. What got me interested in gardening was the first time I heard the term “landscape architecture,” it was like a light bulb went off. And I did think about studying it. I applied to landscape architecture school; I did think about it for a time. But it was really just this idea of both design and nature together that I thought was so compelling as an idea—that you could work with the materials of nature to create space.

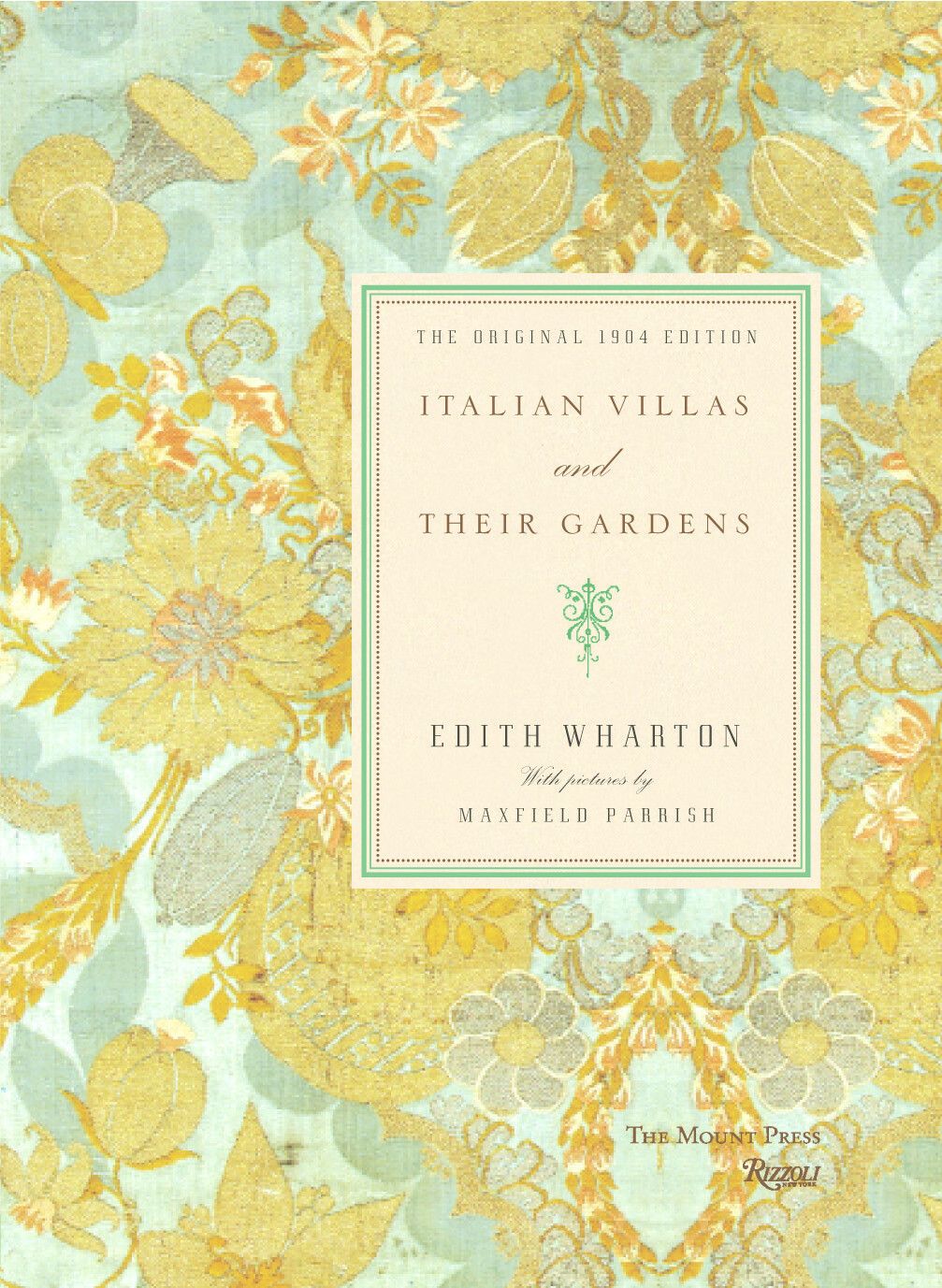

Cover of Italian Villas and Their Gardens by Edith Wharton. (Courtesy Rizzoli)

In the beginning, I had been a garden writer and when I started the garden, I was very into Italian gardens and I had done a tour. Edith Wharton wrote a book about Italian villas and gardens in early, early twentieth century, and I went and did her tour. I followed in her footsteps of her trip and went to all these amazing Italian gardens, Renaissance gardens. And so the first thing I did was create a very strict boxwood parterre, like a low boxwood hedge, and then filled it with just wild, wild plants—and that’s still there. And then I got really interested in the idea of cutting flowers and created a cutting garden, and then growing vegetables, which I’m terrible at, and they’re much better at the farmer’s market than they are—“five-hundred-dollar tomato,” is what my husband [Jacob Weisberg] calls it. [Laughter] And just recently, I’ve now planted a big meadow using mostly native plants, but in a very designed color palette. A lot of native plants are orange and red and yellow, and those aren’t my colors. So I’m very curious to see what it looks like this summer and fall.

SB: Going back, I really wanted to bring up this Slate article from 1997.

DN: Oh, my God. This is like a This Is Your Life episode.

SB: You note in it that you’ve always “always been drawn to the drama of landscape, of wild nature and grand, cultivated gardens. To be able to fashion beauty from light, scent, earth, flora, and fauna, and then to give it over to the uncontrollable forces of time and decay seemed an endeavor noble and humbling.” Now that it’s been twenty-five years since writing that, I was wondering what sort of wisdom do you feel you’ve learned or experience have you gained through this time you’ve spent tending to gardens, plants, flowers over these years?

DN: It’s interesting because when I look back on things that I’ve written, I usually cringe. And actually, I’m not sure that I’ve learned any more than that.

SB: [Laughs]

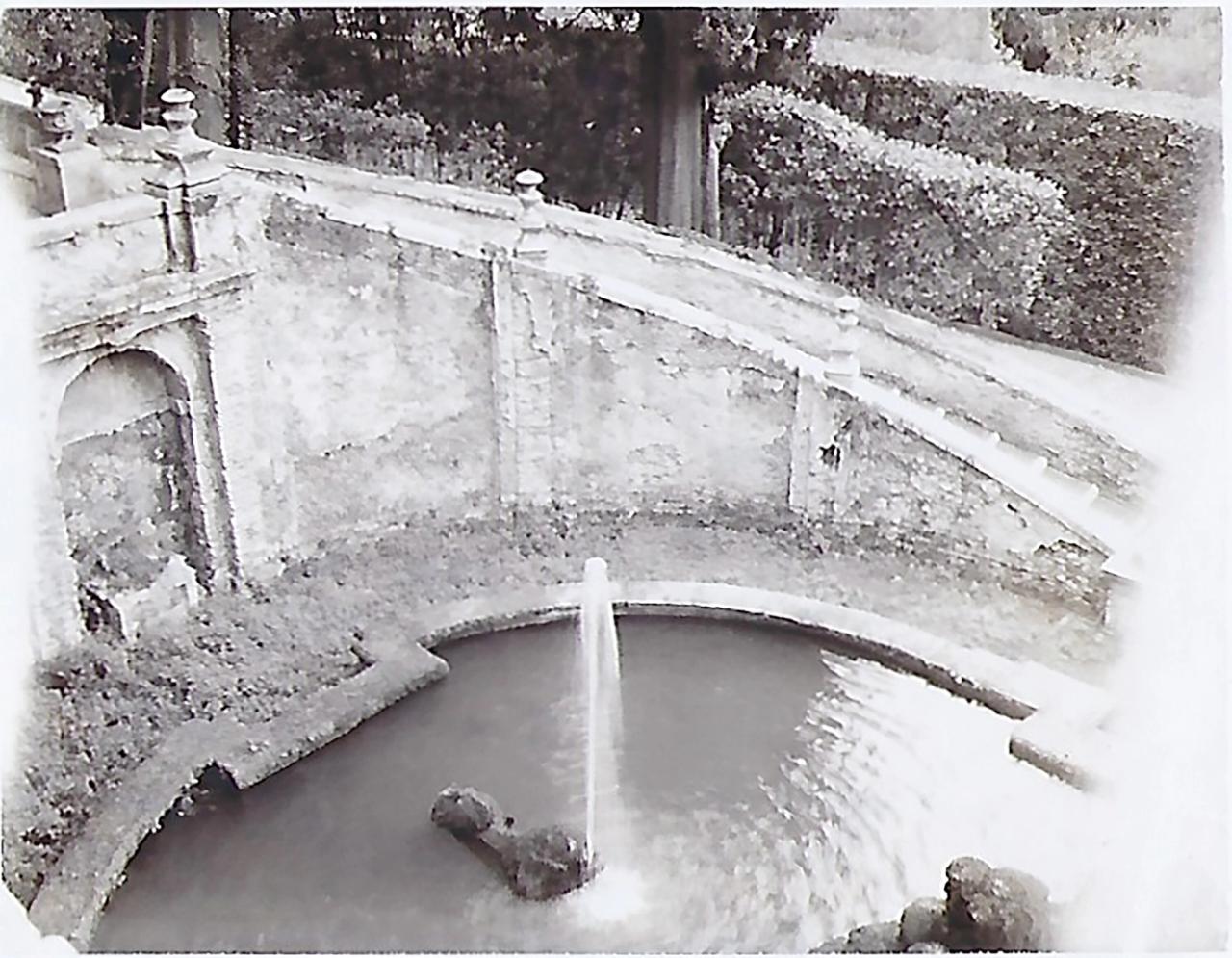

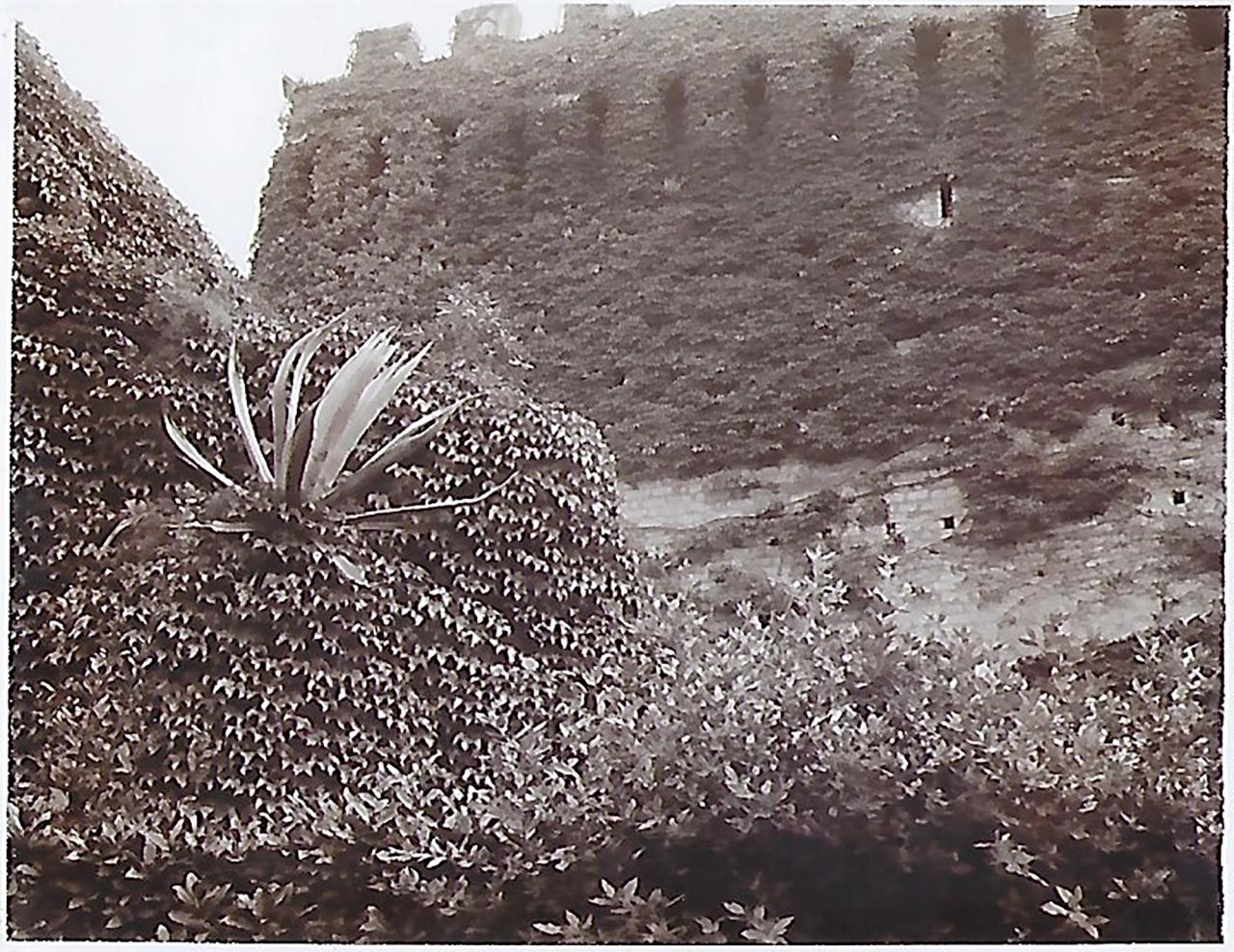

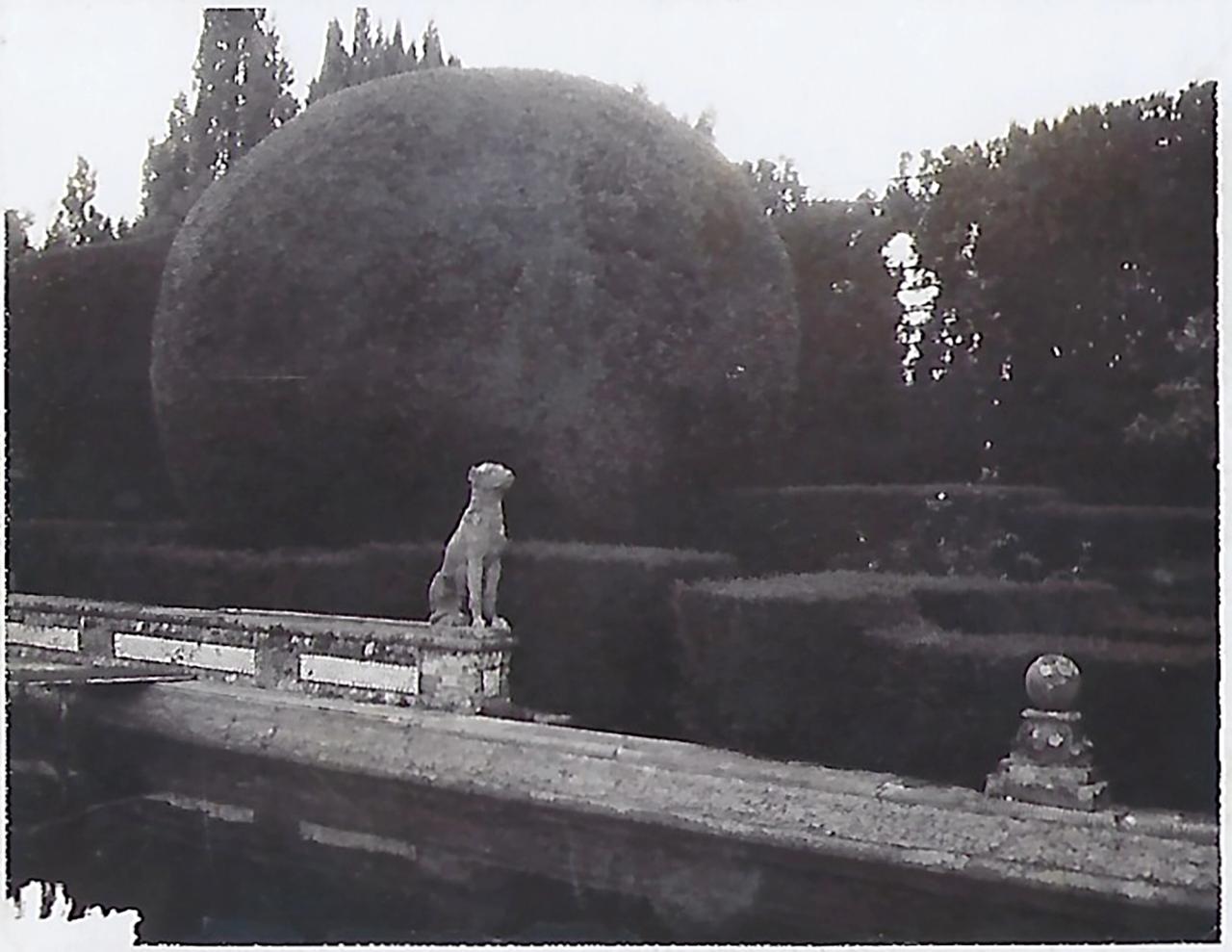

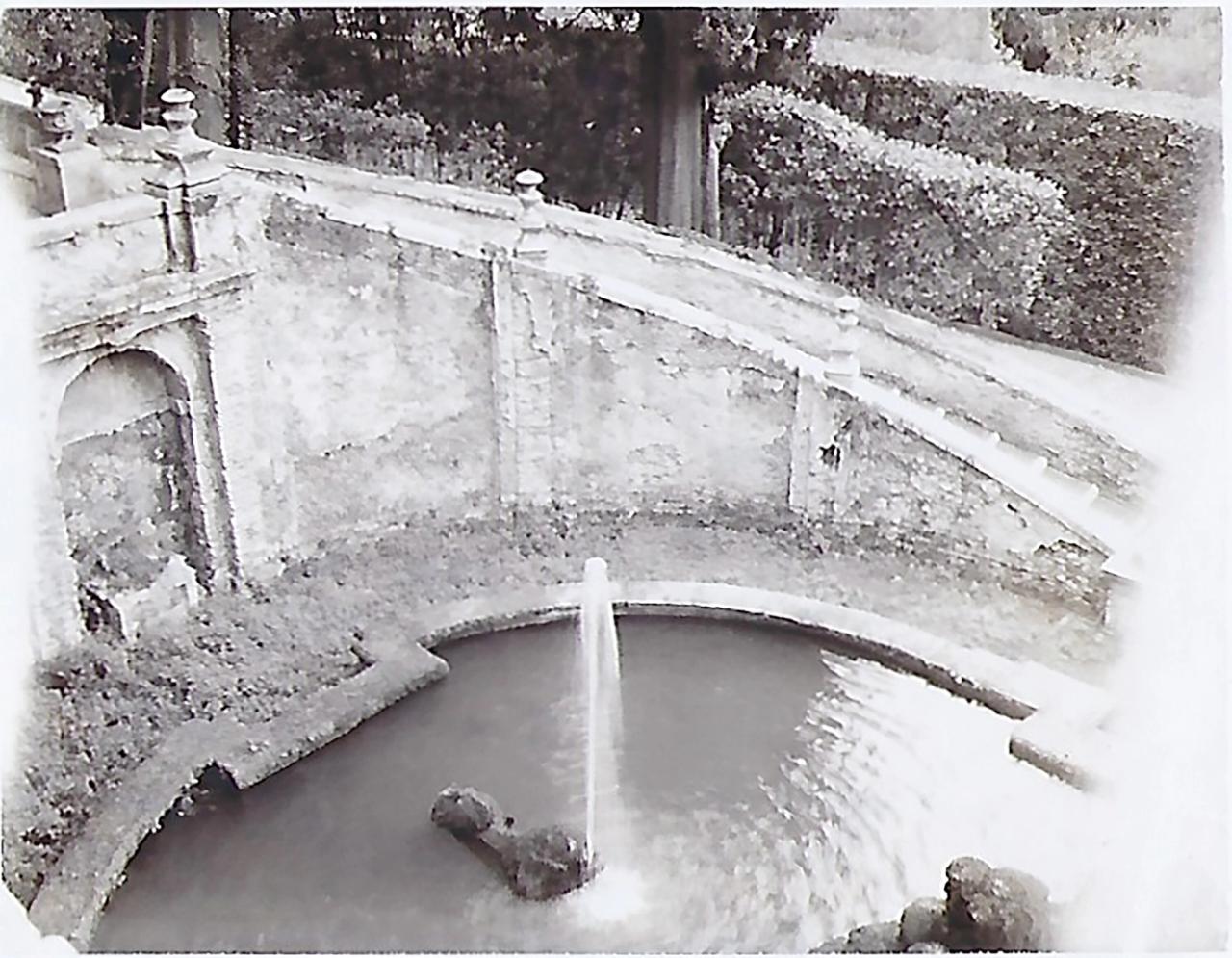

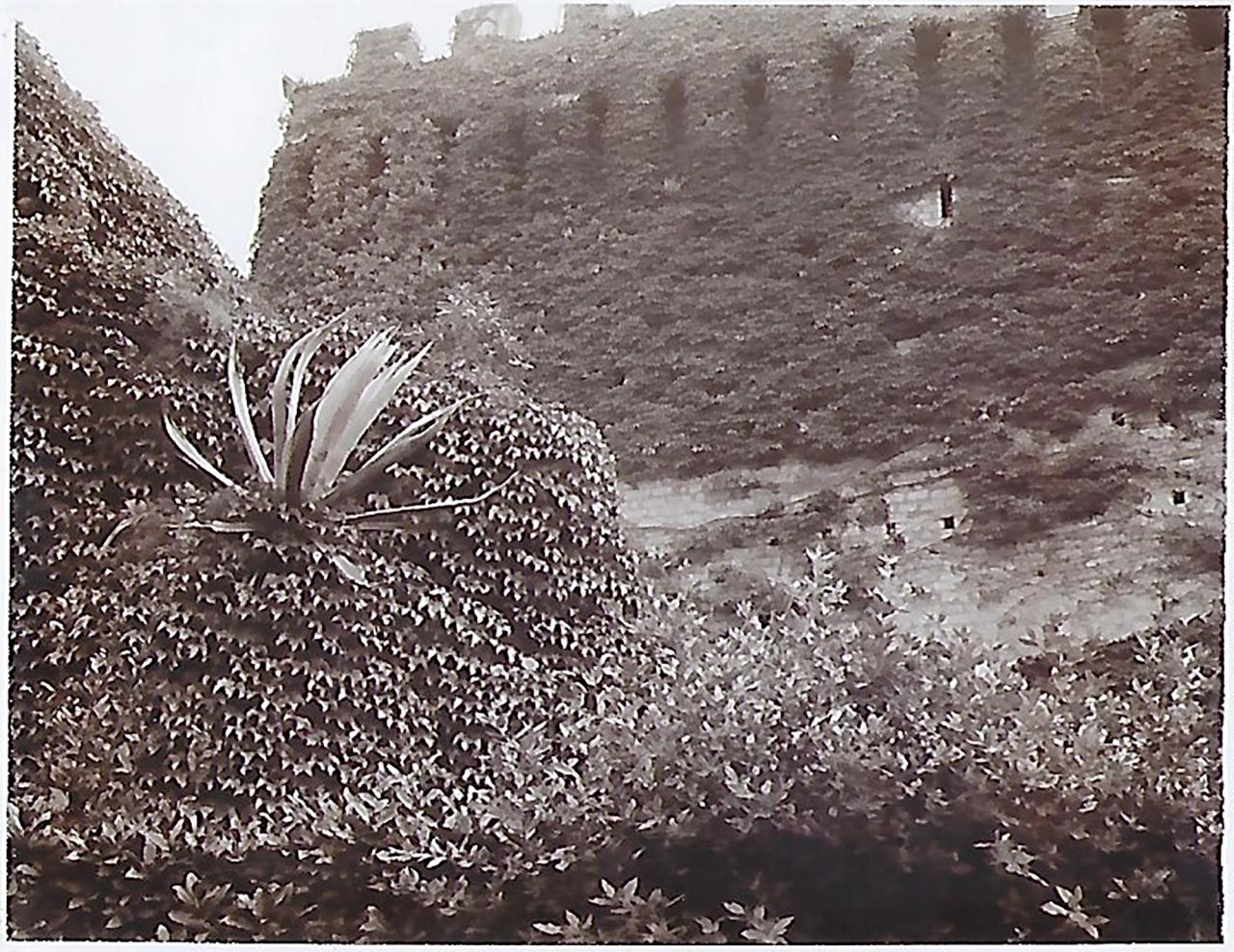

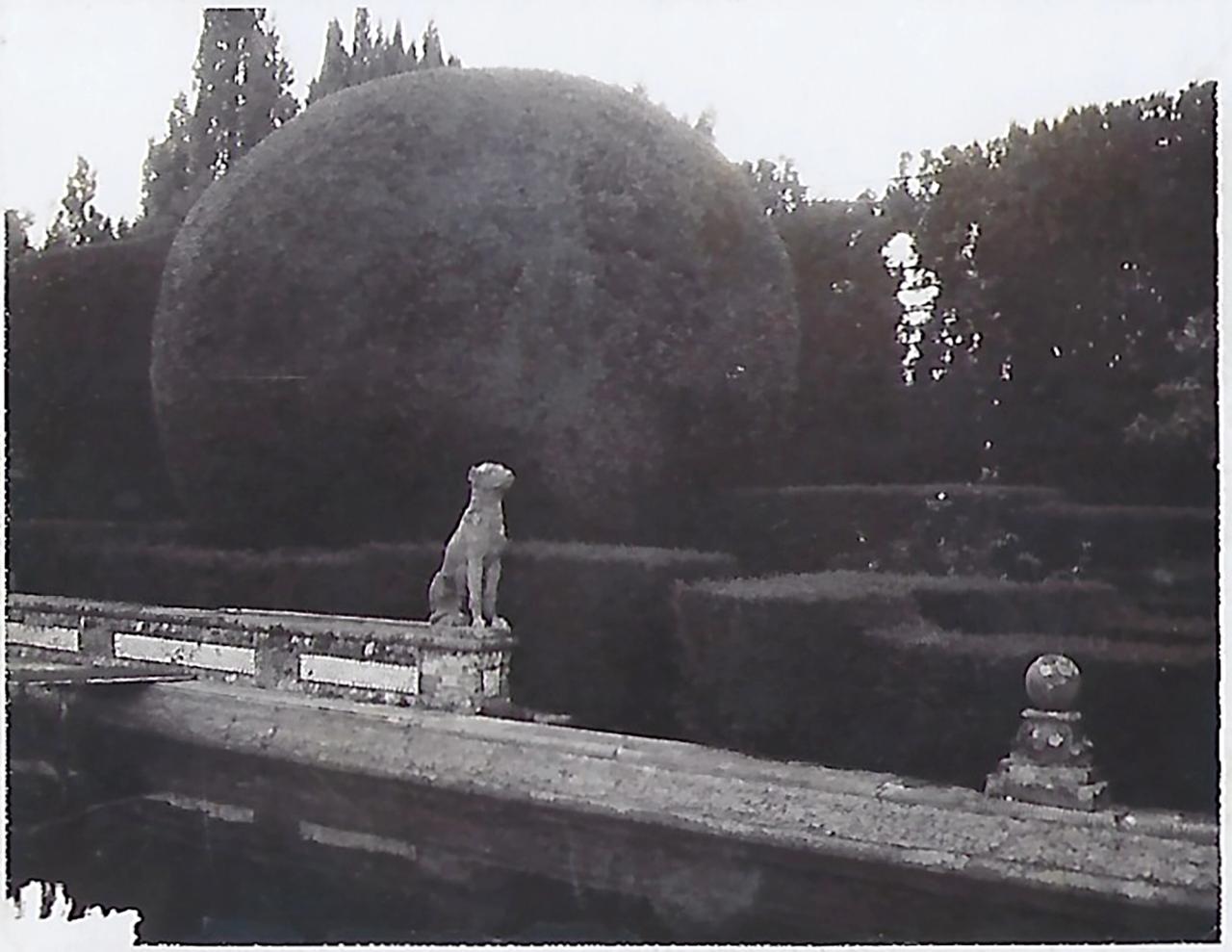

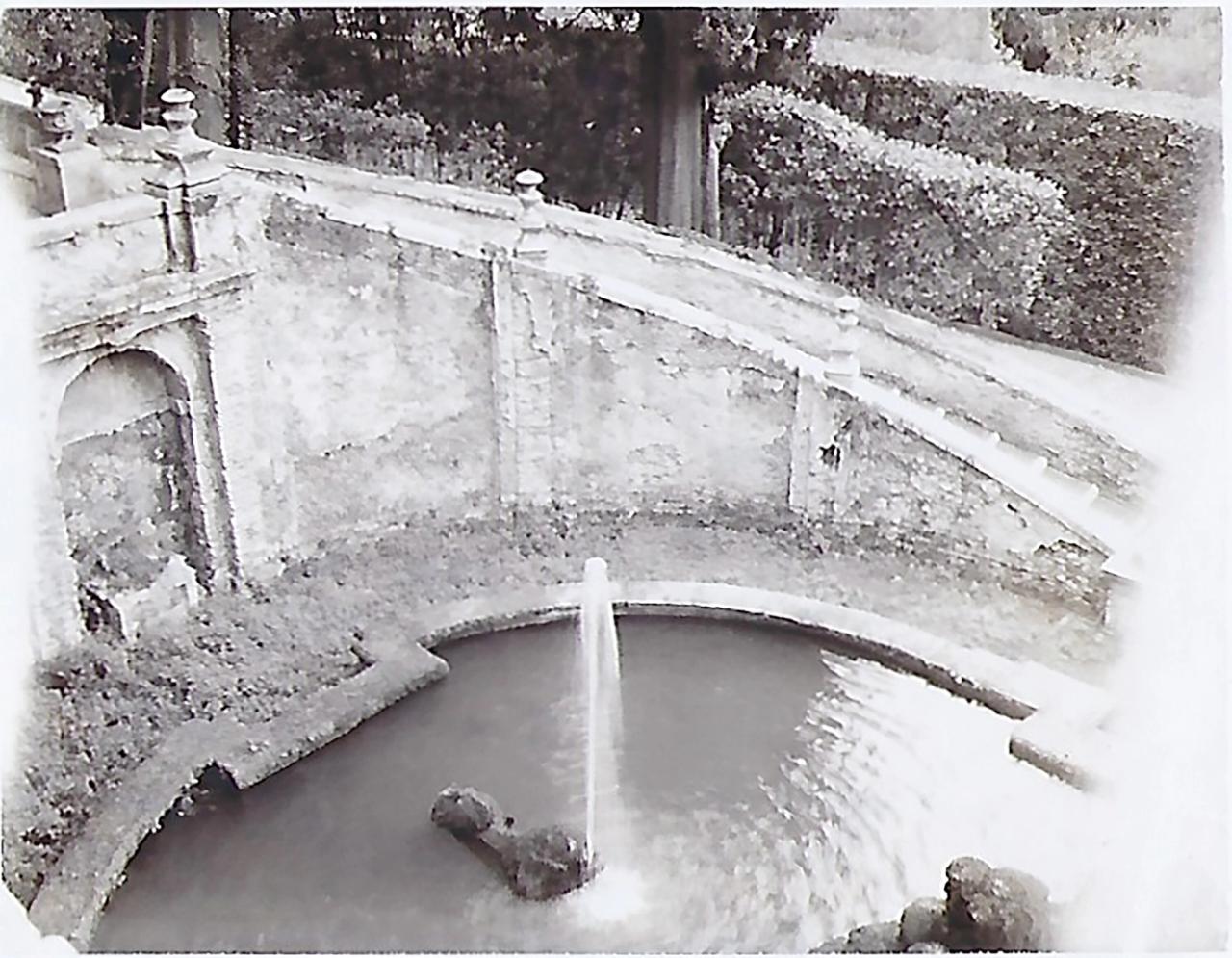

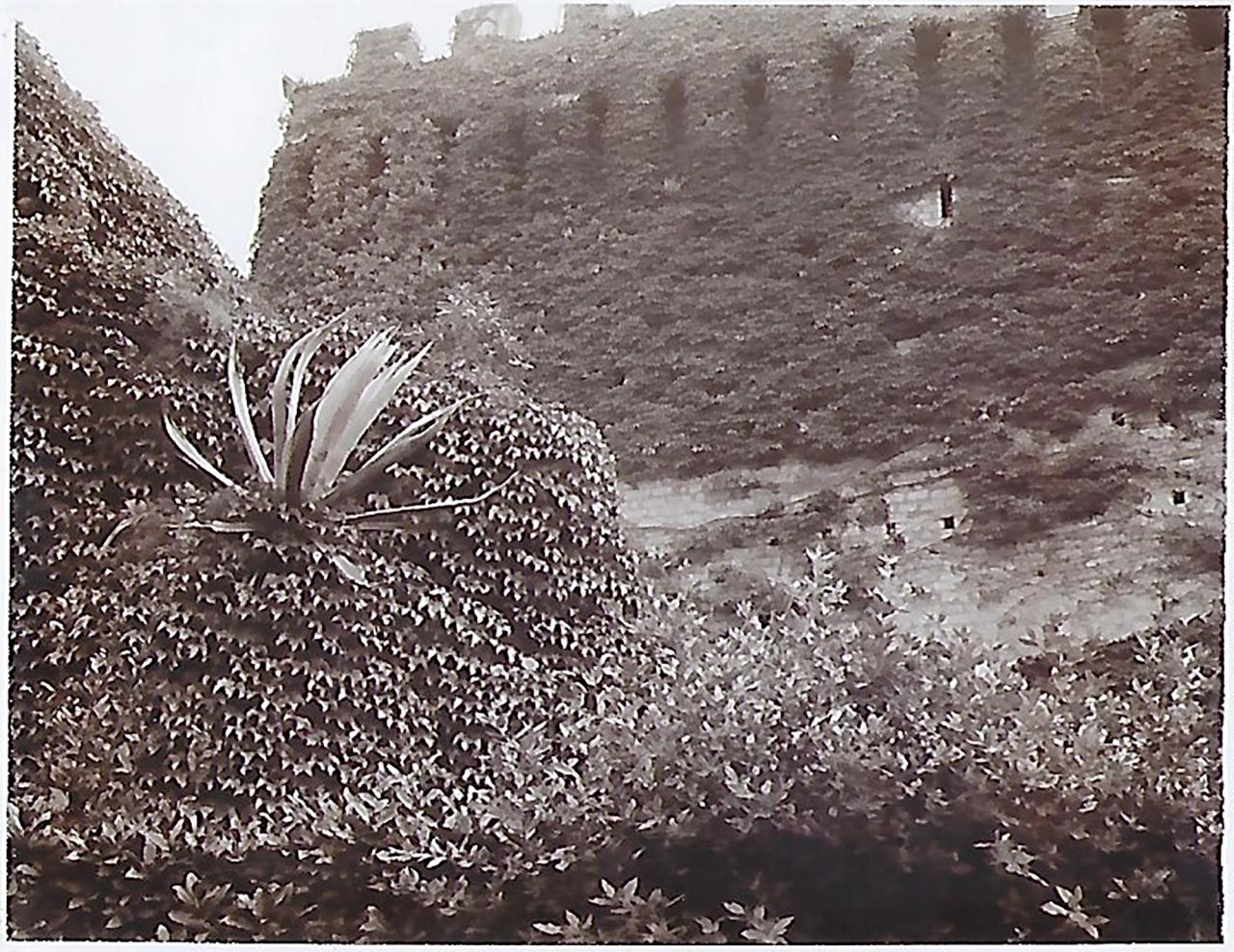

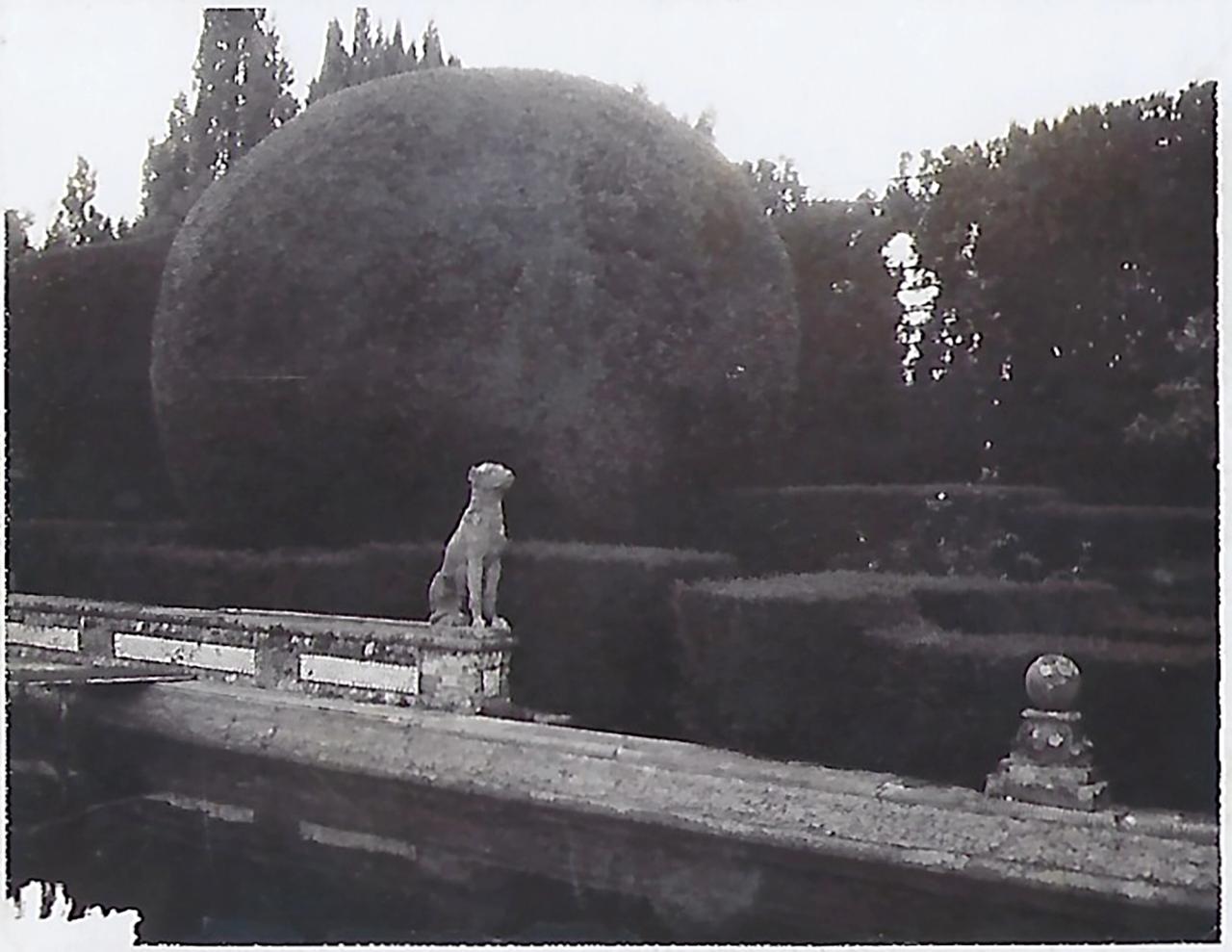

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Image from Needleman’s tour of Italian Renaissance gardens in 1996. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

“Landscape, nature, it doesn’t give a shit about you. It’s going to carry on doing what it’s doing.”

DN: Except for that the process is deeply, deeply, deeply satisfying. Being engaged with nature that way is still really, for lack of a better word, nurturing to me. So I’m sort of pleased that I still feel the same way. It does feel like this privilege to engage with the forces of nature, and of course it’s humbling because the landscape, nature, it doesn’t give a shit about you. It’s going to carry on doing what it’s doing. I don’t know, I really like things that are humble. Like the idea of creating beauty from humble materials is very satisfying to me.

SB: In this context, I did want to also bring up the garden writer Henry Mitchell.

DN: Oh, my God, I love your research.

SB: He died nearly thirty years ago, but for around two decades, he’d written a gardening column called “Earthman” for The Washington Post and you wrote a piece about him, again in the late nineties for Slate, hailing him “the anti-Martha.” Could you share a bit about what made his thinking perspective so special, so essential, and why did it resonate I guess with you?

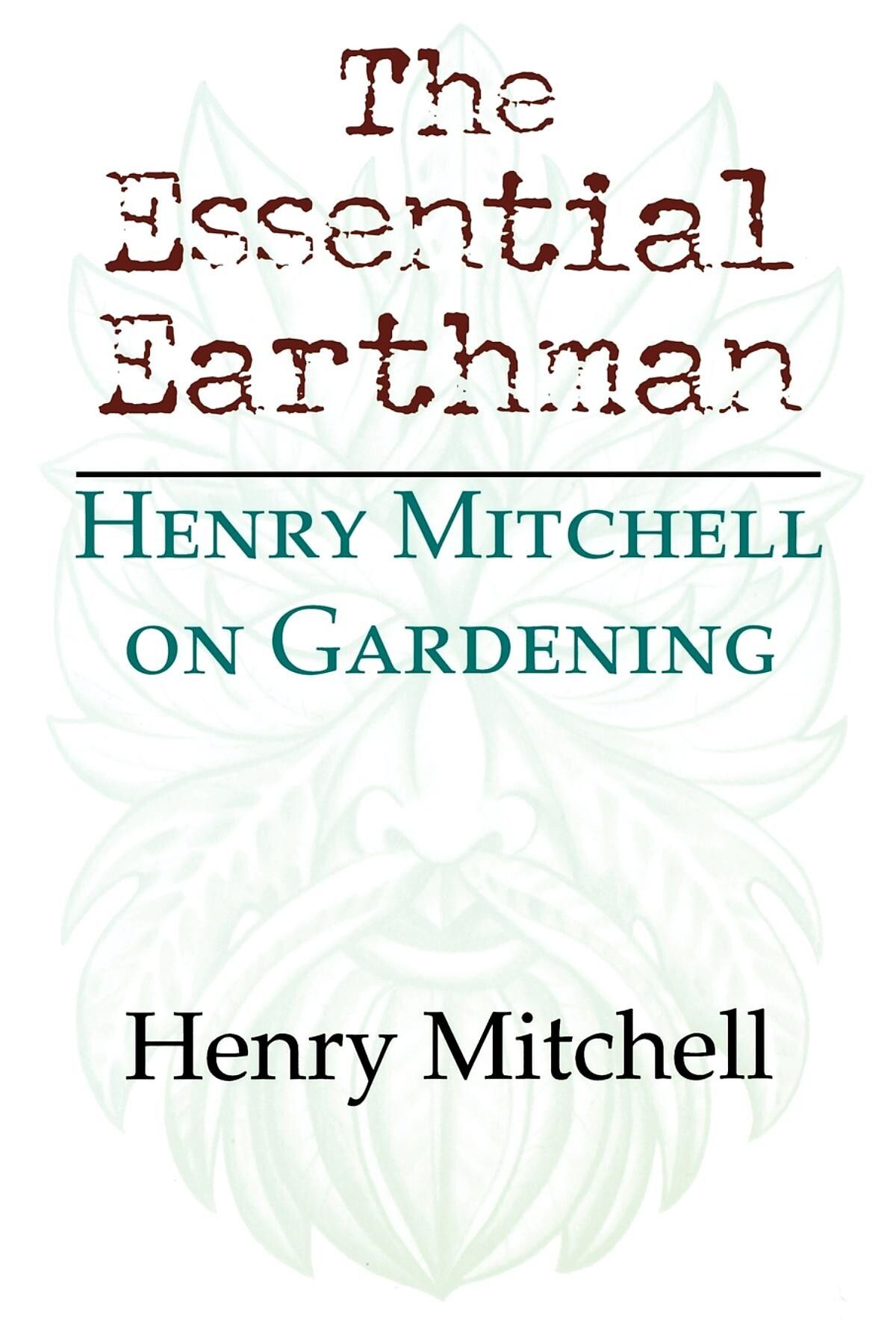

Cover of The Essential Earthman: Henry Mitchell on Gardening by Henry Mitchell, a collection of the best of his long-running column, “Earthman,” for The Washington Post. (Courtesy Indiana University Press)

DN: I’m so glad you asked that. I think he’s a writer that even in the garden world, he’s not that well known and he should be better known. He was incredibly literate, just a great writer, really smart, really funny, really eccentric guy. But what he showed me was that you could use something as simple as gardening or looking at a flower and use it as a window onto the world, to think about anything.

He was amazing. I can’t remember if it’s in his books or he told me—so I worked with him for a short time at The Washington Post back in the days when there was a smoking room. It was like a tiny room like this, just filled with smoke, and he was a great smoker. But he would take the day off when his bearded irises bloomed so he could watch them or he’d make little diving boards for the dragonflies to get into the water and watch them have sex. And he was just a great writer.

I don’t know if I wrote about it in that article you’re referring to, but he wrote about Katherine White, who was E. B. White’s wife, and was a longtime editor at The New Yorker and wrote really beautifully on gardening, that when she was dying in the fall of the last year of her life, she went out and planted bulbs knowing she would never see them bloom. And that just has always really stayed with me. I think I would do the same. And I was thinking the other day, there’s Atul Gawande’s book, [Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End], which is a book with the idea that people should think about what are the things they want to live for, if they’re very sick at the end of their life. So it’s this idea of, instead of just extending your life as long as possible regardless of how many interventions are being done. And I just thought, I would always want to live to see another spring. And that sounds quite—

SB: We won’t turn it into a pull quote.

[Laughter]

“Especially when you’re learning something for the first time, you’re thwarted a lot, and you have a lot of failure and a lot of frustration.”

DN: Exactly, exactly. “I just want to live for another spring!” But I feel like that would be one thing, but I also just think there’s something about the hopefulness and about putting it out there and someone else is going to see those flowers. I just think that’s such a beautiful thing. And I think, for me, basketry is a little bit like that, too, because it’s just this humble thing. You make a basket and it goes out into the world, and it goes into one person’s house and they may love it and cherish it, or they may never think about it again, or it might get beat up, or it might get thrown onto the compost pile. But it’s just like a tiny offering that goes out that I find kind of pleasing, maybe intellectually in the same way. Or viscerally.

SB: Yeah. In that piece, you did write that it was also sort of learning a means to get over yourself, which I found interesting.

DN: Yeah. Especially when you’re learning something for the first time, you’re thwarted a lot, and you have a lot of failure and a lot of frustration. That’s interesting that you bring that up because that’s part of what I face now, trying to learn a completely new skill and way of life at my advanced age. But yeah, because you can have the amazing ideas in your head of what you’d like to make and then a storm comes or the deer come or whatever. So yes, you realize that you have to sort of give up a bit of control and not worry about it too much.

SB: What, to you, makes the perfect garden?

“The more in tune a garden is with its location, the more beautiful it is.”

DN: [Laughs] I think it’s similar to the perfect house, in the sense that it reflects the person who’s made it, the person who lives there, the place it’s being done, the vernacular, whether that’s materials…. But I think the closer it is connected to a place—and that doesn’t mean that it has to be all native plants, but it does need to be all plants that would be happy in that environment. So I think the more in tune a garden is with its location, the more beautiful it is. I don’t know, it’s not that I’m indiscriminate, but there are so many different kinds of beautiful gardens.

SB: You’ve mentioned you have this affinity for the work of Piet Oudolf, who’s this incredible Dutch garden designer.

DN: And we’re sitting here right next to the High Line, which he did.

SB: Yeah. What is it about his work that appeals to you? He’s really known for his use of perennials and grasses and—

DN: He really started cultivating meadow plants. Actually, to answer your question before, I think a meadow is my ultimate—something that feels wispy and wild and moves with the wind is probably my favorite kind of garden space. And Piet was incredibly innovative in thinking about plants. People always thought about plants of like, “a rose, it blooms in June,” and he really thought about the entire life cycle of a plant and was one of the first people to really popularize the idea of beauty throughout the seasons. That a seed head is beautiful; that, covered in snow, a plant is beautiful; that its skeleton can be beautiful. But in his own garden, in Hummelo, where I went and stayed with him once, there is a lot of structure. The High Line is all this sort of wildness because it was this idea of recreating the abandoned, neglected space but he does have a lot of structure. I think you do need structure in a garden, or probably in anything.

And maybe that’s similar with craft, too, and basketry. I hadn’t thought about it, but as a craftsperson, as opposed to a fine artist, you’re not inventing anything. You’re definitely not reinventing the wheel in any way, and you’re working within a structure and within these limitations that have been going on for centuries. I mean, basketry hasn’t really changed, and you’re still working with the same basic weaves. The creativity happens in the small places in between and in the repetition, which—we think of repetition as being boring, but that’s sort of where everything happens in craft and that’s where you learn and that’s where…. Anyway, but I do think this idea of structure is important in a garden, and it’s completely a real fact of life in doing craft.

SB: Well, I’m struck, too, that it’s so central to magazine-making, this idea of structure, of having a form and rigor and sort of these—

DN: Yes, exactly.

SB: You can play within the pages, but there is a certain—

“I don’t really see these things as being so disparate, making a magazine or making a basket.”

DN: There’s still a cover and there’s still the back and there’s still the middle, it’s so true. And that’s why I don’t really see these things as being so disparate, making a magazine or making a basket. They are different in the sense that one is a very collaborative effort and one is a very individual [one]—you can only do it by yourself. But I think part of my great joy in making magazines, and even the way I talk about it is, it was making this thing every week. And yes, how do you fill that shape? And how can you be creative within…? You’re dealing with words, pictures, layout, pages. That was always a really fun puzzle. I guess I like some structure.

[Laughter]

SB: You’ve also written about, and done a lot of work around, flower arranging. And obviously this extends out of the garden, but you’ve thought about flower arranging, the art of ikebana. In your book The Perfectly Imperfect Home—

A flower arrangement by Needleman. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

DN: My God, this is really…

SB: —you note that that “the thought of arranging flowers can unhinge even the most stylish people,” which made me laugh, and that “the secret to ‘doing’ flowers is to not be intimidated.” And so I was wondering, how do you think about the act of arranging flowers? Why do you think it’s so fulfilling? Why do so many people put so much time into this ritual?

DN: For me, the way I do it now mostly is, like, cut and plunk, and I find that satisfying enough and beautiful. And I don’t really do elaborate flower arranging, but I do think it is really beautiful. And I think, as with ikebana, as with any kind of flower arranging, it’s really that you’re looking closely at the elements of nature and trying to create a composition and trying to create a sense of harmony. And I don’t know, it’s just pretty. It’s just nice to have them in your house, but I don’t know, I guess maybe flower arranging is something I’m not thinking about so much anymore. Although, I’m obsessed with flowers and I grow cut flowers, and I have to have flowers in every room. But I think for me, at this point, a single stem in a vase is enough, a bunch of wild flowers or weeds, even is enough that it’s not a way I really spend my time.

SB: Let’s turn to tea-making. Tell me about your path to this art and what’s involved in it. The planting, the harvesting, the drying. I remember ordering a bunch of this tea, actually, in the fall of 2020, and it was extraordinary. There was texture, there were layers. This was a tea that—

DN: Spencer, you’re amazing.

SB: I could tell that this was on a certain level. Something, if I can be as bold to say, crafted. It’s not the store-bought variety.

Packets of Needleman’s Garden Tea. (Courtesy Saipua)

The herbs Needleman uses to make her Garden Tea. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

The herbs Needleman uses to make her Garden Tea. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Packets of Needleman’s Garden Tea. (Courtesy Saipua)

The herbs Needleman uses to make her Garden Tea. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

The herbs Needleman uses to make her Garden Tea. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Packets of Needleman’s Garden Tea. (Courtesy Saipua)

The herbs Needleman uses to make her Garden Tea. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

The herbs Needleman uses to make her Garden Tea. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

DN: [Laughs] So it’s all herbal tea, and the idea was, or how I have been doing it, was growing everything and making this tea. And it sort of happened by accident. In a way, I think it was sort of like a gateway drug until I could really get the basketry thing up and running, because it gave me away, immediately, as we were talking about before, of getting a foothold into the seasons. I don’t even drink tea, but I just loved the whole idea of what you were saying—of this idea of planting, harvesting, processing, and that it took me through the months of the year in a way that felt very connected to nature. That said, last year I tried to sort of scale it up, so to speak, and by that I mean going from three hundred units of it to six hundred, and it just became sort of a chore. And it’s a lot of work. And so I’m not sure that I’ll keep doing it. I think I’ll do it for friends, but I think in a certain sense, it was a way for me to be involved with plants right away when I was still trying to set up a studio and plant my own willow and learn—basket-making, you can’t just get out there and do it, it’s a lot to learn. And so this was a sort of easy way to just insert myself into the life of plants.

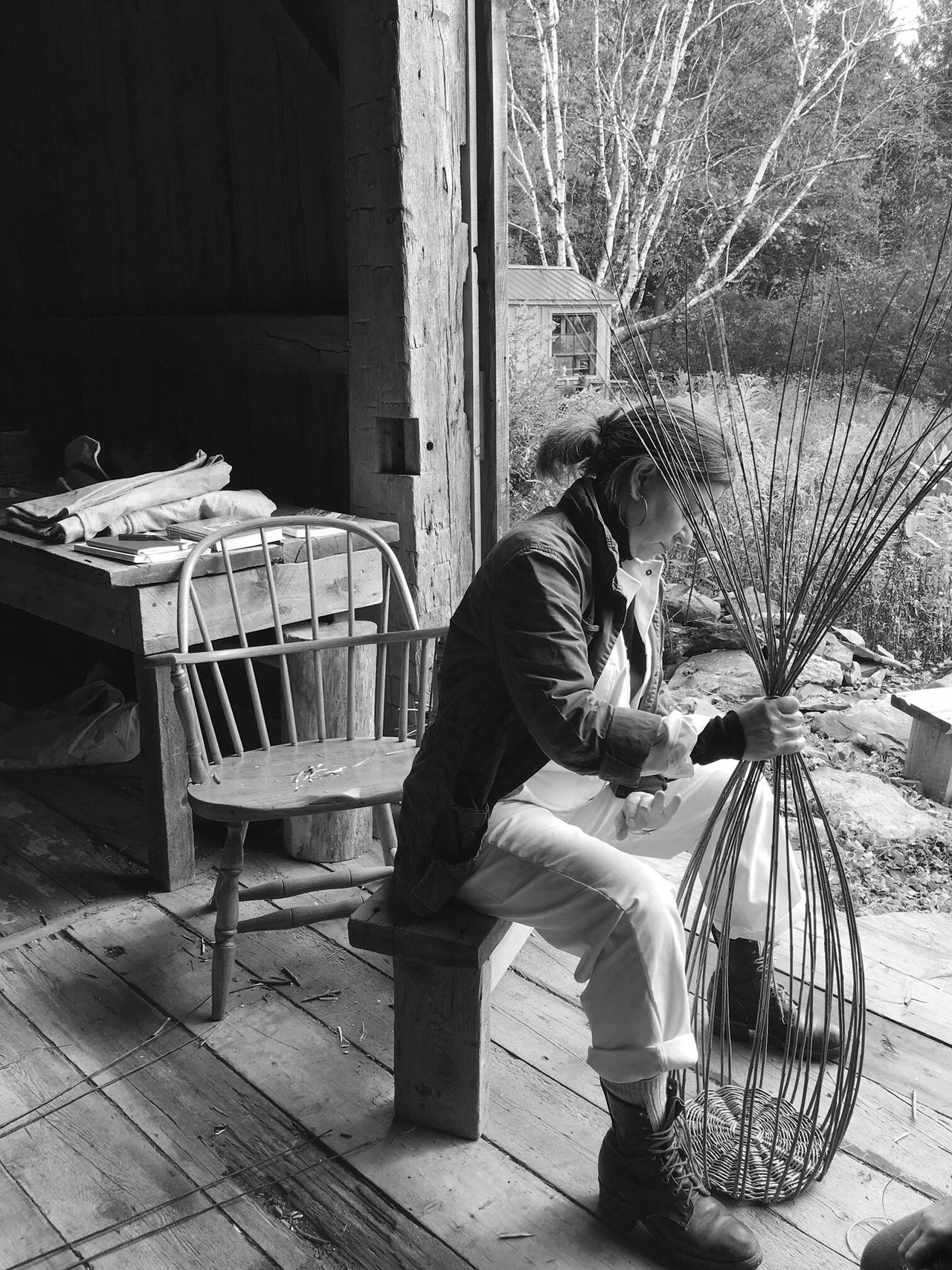

Needleman weaving a basket. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: In wine-making, they like to talk about terroir, but with this, what struck me, is I really felt like I was getting to experience your gardens now.

DN: That’s so nice. They are all plants that I love. Obviously the taste is important, so I had other people taste with me since I’m no expert, but it was that I really wanted it to be redolent and to be beautiful and to have a lot of different colors in it. So I did think about all that, so thanks for noticing that.

SB: So switching gears a bit, but staying on the craft tip: You’ve written that “modern consumer society has grown dissatisfied with using economic efficiency as a basis for appraising time.” [Editor’s note: This quote was also referenced by Spencer in Ep. 50 featuring curator and scholar Glenn Adamson.] And I wanted to approach your craftwork with this quote in mind. What does broom-making, basketry—all craft, really—reveal about time, its value, and our relationship to it?

DN: So most objects of craft are not things that people really think a lot about, and there isn’t a high value on them monetarily. I think people do appreciate these things, and craft always gets sort of stuck in any capitalist economic system because it’s so wildly inefficient. But that said, I think, if it’s possible, it can be an incredible way to organize your life, to live your life, to think about these things and have a relationship with things. The more you know about them, the richer that experience is. I mean, you had Glenn Adamson on, who is just an incredible historian and thinker about craft. And there is a thing that has sort of tripped up every philosopher or thinker about craft since the Industrial Revolution, when craft basically became a thing. And it became a thing because before that—

SB: It wasn’t called craft.

DN: It wasn’t called craft, it was called just getting on with your life and making things you need.

SB: [Laughs] Yeah.

“I think everyone can have some bit of luxury in their life.”

DN: But once you start to think about craft as a thing that people do and as a choice and as maybe something that’s valuable or interesting in the world, people get caught up in this idea, well, it’s a luxury and it’s not democratic because it is expensive and economically inefficient. The idea that it’s a luxury, I think, is not necessarily a bad thing because it means that people value it and not everyone has to…. I think everyone can have some bit of luxury in their life, and you don’t have to have every pot in your house thrown by hand, but to have one or two things and to appreciate them is amazing. And I think that there’s no reason, really, to get tripped up on a philosophical level that craft is a luxury, that it is expensive. That doesn’t concern me. But it is not viable as a way to organize a modern society. So, it is also a luxury for someone like myself, who chooses to be a craftsperson. And in lieu of financial rewards, you have this other thing, which is freedom and this relationship to your materials, relationship to yourself, doing what you want to do with your life. Which is incredibly valuable.

A broom made by Motonao Yonezawa. (Courtesy Analogue Life)

SB: I wanted to go back to broom-making.

DN: Okay. That is the humblest of humble. No one thinks about brooms. [Laughs]

SB: Let’s talk about brooms. You’ve written about and visited with Motonao Yonezawa, who’s this third-generation Japanese broom-maker, and you’ve also written about Berea College, which has this incredible broom workshop in Kentucky. I was hoping you could speak to both of these experiences.

DN: So Berea is this incredible college in Kentucky that is for the bottom rung of the economic ladder. So you have to be incredibly smart. It’s entirely free, and you have to economically not be able to afford college. And it’s a great liberal-arts education. I’m sort of surprised this school’s not better known. And in return for this free education, the students have to work ten hours a week at either one of the craft workshops. They have a broom workshop, a pottery, a weaving workshop, and there’s also a farm and then there’s this gallery, so there are a lot of different jobs that one could have. And I sort of fell in love with this place and this college and the broom workshop.

Chris Robbins, the master broom maker at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

A student in the broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

Chris Robbins, the master broom maker at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

A student in the broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

Chris Robbins, the master broom maker at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

A student in the broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

The broom workshop at Berea College. (Photo: Justin Skeens. Courtesy Berea College)

And so there the guy that runs the broom workshop [Chris Robbins] is a guy from Appalachia. I can’t remember if he’s from Kentucky, and I don’t even remember how he learned, but is just completely enthused by what he does. I just was so blown away that he could make something that someone else would buy. And you know, the tradition of broom-making…. And not “you know,” because people don’t really think about brooms, but the broom[-making] in Appalachia comes largely out of the Shaker tradition, which is the first kind of flattening of a broom. Brooms in Europe were round until then and made out of other kinds of sticks. And it’s very much a means to an end. I don’t think most of the kids are going to become broom-makers, but it is a way for them to learn about responsibility and to learn about craft. It’s an incredible program.

“There’s no reason, really, to get tripped up on a philosophical level that craft is a luxury, that it is expensive. That doesn’t concern me.”

And then, on the other hand, you go to Japan, where craft is much more revered and understood within the culture and this whole idea of intangible assets and intangible treasures. And the process there—everything was so beautiful. This maker and his parents, they grow the material right outside the studio. It’s like the way of tea or so much about Japanese craft. There’s great consideration at every step of the process. And that is not our American tradition. As wonderful as what’s going on in Berea is, that kind of broom is not thought about in the same way. Even at the time I was there, the broom corn gets imported from Mexico. Who knows what kind of pesticides, sometimes they dye it with Rit or R-I-T. It wasn’t thought about in a holistic, even sustainable way.

SB: Right. It’s process, it’s not necessarily of—

DN: Yes, in America, it was much more, okay, the product. And it is really nice to use a broom that’s handmade, but there isn’t the respect given to the whole process.

The seat cushion Needleman wove for a chair commissioned by the Italian interiors magazine Cabana. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: And what about basketry? And basketry is fascinating for multiple reasons, but I think chief among them is the fact that it’s something that can’t be mechanized. It’s probably the one craft that isn’t being done in a factory—

DN: I’ve been saying that, and I believe that is true, that it is the one object that can’t be created by a machine. And I’m not sure if it’s because of the weaving and the three-dimensionality. But I do think that’s true. And I think another thing that’s amazing about basketry is it’s the only thing I can think of—I’m sure you can think of something else, but—where the materials aren’t transformed at all. In the end, it’s still a bunch of sticks just woven together. It’s not glazed, it’s not fired, it’s not sand turned into glass.

SB: There’s a purity.

DN: A real simplicity. So that you’re still looking at a bunch of sticks. And I just think those bunch of sticks are so beautiful, and that it’s so magical that you can twist them up into an object, and you can’t really see how it was done. I don’t know, I think there’s a certain magic to that.

SB: You’ve woven a chair.

DN: Well, I didn’t weave the chair frame, that was for a project for an Italian magazine called Cabana. They gave you the chair frame and I covered it in a weave.

SB: Still extraordinary.

DN: But then I wove the seat cushion. I guess I sort of did. That was really fun and a great learning experience. And part of what’s just amazing is learning new things at 58, which I think that’s what I am. I feel really lucky to get to do that.

SB: And over the past few years, you’ve written about a lot of different crafts: Japanese indigo dyeing, Sardinian weaving, Jaipur block printing, and wicker furniture made of rattan. I realize it’s probably impossible to choose, but I was wondering which of these crafts have stood out to you as the most extraordinary amongst all this reporting—

DN: I like your “favorite color” questions: favorite garden, favorite kind of craft…. [Laughs]

SB: Well, I think it’s, like, amongst your reporting….

“Craft since the Industrial Revolution has always been in peril. It’s always about to be extinct or has become extinct.”

DN: So when I left my job at T, the editor who replaced me, Hanya Yanagihara, gave me a column [called Material Culture], and it lasted for a year, where I was to go around the world and check in on the state of traditional craft around the world. So it was this big kind of mandate in a tiny, fifteen-hundred-word column. But what blew me away was not any one craft over the other, but just the idea that so much of this is still going on, and it’s been someone weaving on a hand loom or a katazome stencil dyer in Japan, who’s cutting his stencils himself, tending to an indigo vat by himself in his backyard, or the broom-makers in Berea, Kentucky—just the fact that this stuff is still going on and so that there’s this connection between knowledge that people have now to knowledge and practices that have gone on forever. And craft since the Industrial Revolution has always been in peril, and it’s always about to be extinct or has become extinct. The knowledge is very tenuous because there’s so few people who do it, and yet somehow it’s been carried on. It’s just amazing to me, that connection, and people still working and creating within ancient traditions.

A chair by Larsson Korgmakare. (Courtesy Larsson Korgmakare)

SB: And I think there’s something about—obviously, with great privilege, you got to go travel and see this in person. But I think there is something about seeing the act of it, and one of the places you wrote about, in Stockholm—I might butcher the name, but it’s Larsson Korgmakare, I think. It was established in 1903. It’s a wicker furniture company, most famously having worked with the designer Josef Frank. I actually got to go visit that same place in Stockholm a few years—

DN: Are you serious?!

SB: —ago and saw this wicker-maker and was blown away. And I feel like—

DN: That is crazy.

SB: The only way to do it justice on this episode is to kind of just explain how extraordinary it is. You’re in this tiny little, kind of sunken basement room watching this one—

DN: It’s one woman [Erica Larsson]. She learned from her parents and she’s the only one left. And there used to be hundreds or thousands of rattan and wicker—wicker is the weave—but rattan furniture-makers across Europe. And there’s one left in Sweden, one in Italy, I think one in America, one in England. There’s just so few. And so it is just amazing. You were there, and if something happens to her, that’s probably the end of it. Then there’s not one in Sweden anymore.

SB: And the intimacy of being in that kind of environment, smelling the smells, being able to touch the wood. There’s just something that I don’t think can be even expressed on a podcast about this.

Erica Larsson of Larsson Korgmakare crafting a wicker chair. (Courtesy Larsson Korgmakare)

DN: Yes. No, when I walk into my studio in the morning, the smell of the willow is incredible. It affects you in all your senses. That’s amazing you were there.

It’s such a small world, craft, and it is a way into other cultures, and a way to meet people when you’re in another country and it’s a way of seeing and understanding culture. So when I started making brooms, which was really just by accident, in a way, it was like stubbing your toe, and all of a sudden you realize, “Wow, my toe was there all the time.” I was looking and seeing brooms everywhere I went, and I could see in India or in Mexico, or what street sweepers use in other countries, and it’s all from the materials that they have.

Oh, but what I was going to say was when I was in Japan, I went randomly to a craft fair in Matsumoto, and I met this guy and his brooms looked sort of familiar. It turns out he had studied at the John C. Campbell Folk School, because so many times Japanese artisans are obsessed with American—it’s so authentic to study an Appalachian broom. It was just incredible, that kind of synchronicity or whatever.

SB: In October 2017, on Instagram, you described these pursuits as “a slippery descent into middle-aged Jewish hippiedom.”

DN: [Laughs]

SB: Which of course made me laugh.

DN: Really, I have no memory of anything.

SB: How do you actually view these efforts now, though, now that you’ve seen some of the fruits of them? Because what you’re making is at a very high, especially the basketry, it’s at a very high level of craft. And I’m just wondering, how do you view the fruits of your labors?

DN: I think that you’re viewing them more kindly than I would. I have a basketry teacher in England, in Sussex, that I go to see as often as I can, which is not very often. And in England, until probably the eighties, there was this sort of journeyman basketry tradition. I forget how long they studied. Ten years or something until they were good enough to make money at it or to call themselves a basket-maker. And I still feel like I just have so much to learn. I don’t view my work as wonderful or as where I want it to be, but that’s okay. Part of what’s great, is still being excited about, well, the next one’s going to be great, or soon I can make this. It really kind of projects me into the future in a nice way.

SB: The humbling act of creation.

DN: Exactly. [Laughs]

SB: Let’s go back to your youth.

DN: Oh, dear. [Laughs]

SB: So you grew up in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Tell me about your house, your parents. What was your childhood like?

DN: Well, gosh, I hope they’re not listening. [Laughs] I very much rebelled against the environment I grew up in. It felt very cloistered. I was thinking, actually, this morning, for some reason, it was this, as I said, kind of cookie-cutter neighborhood, so there was no sense of place, there was no sense of garden. I have a very distinct memory of the landscape outside our house when I was growing up: where the trees were, what they were. But it was a very sort of suburban landscape planting. But I remember, once, taking a long walk and coming to a wood and realizing, Oh, that’s what all of this must have been like at one time, and now it’s literally like just the backstage to this suburban development. It was like, Now I’m backstage at The Truman Show and you’re not supposed to see this little woods and meadow. That wasn’t part of it—that was just waiting to be leveled.

Needleman as a child, growing up in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

I wish I could say I read books or I became fascinated with X or Y. I didn’t—I was just super rebellious, and I just kept saying no, no, no. And then I got to college, and I hadn’t done very well in high school. I wasn’t interested in school. It was just an “aha” moment and like, I can choose my friends, I can choose what I want to study, there are experts in certain fields. I just became interested and excited about things for the first time in my life.

SB: And you have described your mom as someone who was quite influential to you, at least in terms of her style, her sense of kind of…. Let me see.

DN: You’re such a good researcher, I really do think more about what I think than I do.

SB: So this one’s a throwback.

DN: So unfair, these throwbacks.

SB: I found an interview you did [in 2008] with Philadelphia Magazine.

DN: Oh, my God.

Needleman at one of her birthday parties as a child. Her mother is pictured at right. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: And you said that, “My mother had great taste, but it was more about the way she dressed. I have these memories of her in short white tennis skirts and Tretorns with super tan legs or wearing—”

DN: She was hot.

[Laughter]

SB: “Chic, but not fussy. Very laid-back,” you described her.

DN: That’s funny. She did have a Jackie O kind of seventies look, but I think it just was a very closed environment. She was great-looking and it was a very seventies childhood in the sense it was a bit Ice Storm–y, but less rich. I was weirdly the youngest child ever to take EST, which was this kind of…. There was a thing called Lifespring, there were all these self-actualization courses, and I was just looking for something. There was a lot of seeking.

SB: Yeah. You’ve described, obviously, the environment as quite suburban. And the house itself, you’ve mentioned that there wasn’t really anything personal in it. And it just strikes me that there was this sort of void in your youth of like this overt style, and out of this void, you then go on to create one of the most popular shelter magazines of all time.

DN: Oh, that’s sweet.

SB: You think about environments, nature, interiors in a way that is so the opposite in many respects of what your childhood was. I found that pretty fascinating.

DN: My childhood was not unhappy, but yes, it was…. That’s why I was saying I get attached to these ideas like the garden [as] this wild magical place, or a house that actually feels alive, where people come over and there are things in it that reflect you. And there was nothing wrong with my childhood, but it didn’t appeal to what was in me, which was wanting a house where people came and went, and where things in it meant something to you. It was decorated, it was fine, it was comfortable and we were quite fortunate—

SB: Safe, maybe. Less wild.

“I just longed for something else, and for more chaos and more personality and more bumping up against the world.”

DN: Yes. Safe. Culturally and socioeconomically, everyone was the same. It was all my parents’ friends were middle-class professional Jews the way they were, and I just longed for something else, and for more chaos and more personality and more bumping up against the world.

I guess part of what’s great about journalism is that you don’t have to be an expert and you can gather people that know a lot, and you can ask a lot of questions and that you can get entrée into other worlds. I think I always use journalism as a way to explore these things that were not handed to me. So, in creating Domino, it was, in large part, like, I want to know about all this stuff, I don’t know about it, and how can I learn about it?

Needleman interviewing Michael Govan, director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, at the first New York Times Luxury Conference, which she co-hosted with Vanessa Friedman in 2014. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: A lot of your earliest writing was about gardening. Do you think gardening, in a way, was like an entrée into media somehow, in this maybe roundabout way?

DN: No. I’ve had a weird career path. But my first job was a photographer’s assistant and then I became a photo editor at the Sunday magazine at The Washington Post. So, the whole journalism thing sort of happened by accident. I was a photo editor, then I became interested in gardening, and I was lucky enough to sort of parlay that into a garden editor-writer job at House & Garden, when it was relaunching at Condé Nast.

I don’t think I ever would’ve become a magazine editor if I didn’t have this one magazine that I wanted to make. I had this idea for Domino quite fully formed. It was based on Lucky, which was a fashion version of this same idea of a very user-friendly, practical magazine that spoke to its readers in a much more direct way, as opposed to the sort of fashion dictates from on high. And I think I only became a magazine editor because there was this magazine I wanted to make and I wanted to create and I wanted to explore.

SB: So tell me about that. How did you—you ended up pitching this [to James Truman, Condé Nast’s editorial director at the time].

DN: This was all incredibly out of character for me, because, until that point, I feel like—and I was almost 40—I was quite, I think, fearful. I never wanted to say, “I want to do this.” I was not ambitious; I just was trying to be happy and to do something that I enjoyed. And then I thought, Oh, my God, I’m going to be 40. I better get on with it, snap on. And I had this idea and I’d never done anything like that. I’d only ever been a writer or worked in an office. And it really just came out of me. I saw it, I created a prototype, pitched it, and it took. When I think back on it, I don’t know where all of a sudden I just got confidence. I think it was because I sort of believed in the idea. So I went from being a writer, and maybe, at times, shared an assistant with somebody, if I was lucky, to having a huge staff. I was like, “I don’t know how to run a meeting.” I didn’t know how to do anything. But I did know the magazine that I wanted to make.

Needleman (center), during her Domino years, with creative director Sara Ruffin Costello and design director Dara Caponigro. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: How do you think about that period of Domino? Which was an incredible run—several years. At its peak, you had a rate base of subscribers of eight hundred fifty thousand.

DN: It was fantastic. I really feel like it was a great, great group of people. I was incredibly lucky to work with such talented people. And we created this thing from scratch and that was incredibly bonding, incredibly rewarding. And it did have this incredible engagement with the readers. Frankly, I think Condé Nast didn’t fully understand that at the time, because it was still where everything was driven by ads, and they weren’t really thinking about—

SB: Audience.

DN: Audience. And audience could be bought. It was all about ad revenue. And we had this incredible reader engagement. So the magazine lasted about five years and then it closed during the housing crisis in—

SB: ’08.

DN: ’08, yes.

SB: Lehman Brothers and—

DN: Exactly.

SB: The Great Recession, the rest.

“I realized that I don’t really like running things. I like making them and creating them.”

DN: And in some ways it was a really sad time, and all this, I don’t know, sixty or seventy people that worked there, we all lost our jobs, but I realized also I was incredibly relieved. I felt like it was a great job, I never would’ve left it, and it was taken away. I realized that I could be without a job. And maybe that’s what paved the way for my feeling secure enough to quit a job much later.

I realized that I don’t really like running things. I like making them and creating them. And I think that’s also why I didn’t stay at The Wall Street Journal for very long, or I didn’t stay at The New York Times for very long. I like setting up these things, and I’m not great at being a manager. So when I talk about why I left, I don’t usually talk about one of the reasons that I think also was a real motivating force, which was [that] I didn’t deal with stress well, and I didn’t really like who I became in these environments of stress, where I was dependent on other people to make things. I have very exacting standards, and I wasn’t always my best self. And I wanted to take myself away from that and to not…. I got to work with incredible people who were incredibly talented and worked incredibly hard, and I just felt like I could be so hard on them from my own sense of internal stress. So a big part of it was just like, I want to be nicer. [Laughter] Not that I was—I was also very supportive. But I do think being busy is not all it’s cracked up to be.

“Being busy is not all it’s cracked up to be.”

SB: Right.

DN: Well, there is something nice about: When you have a job, you wake up and you know exactly what you’re meant to do that day. And I think that’s very reassuring in some ways. Every day is sort of structured and you can fight against it or you can do what you’re meant to do, but there are deadlines and there’s people depending on you, and there are places you have to go. Whereas, trying to organize my life around craft, I have to make it up every day. It’s like, who am I today? What am I doing? And it’s liberating, but it’s a lot more work to try and figure out who you are every day and what you’re going to do that day and how you’re going to organize your time. But it’s an incredible luxury.

SB: I did want to touch on that seven-year period between WSJ. and T and some of the work you were able to do during those years. What, in your mind, stands out the most from that time?

DN: I don’t know, I just feel really lucky that I got—as we were saying, when we started talking—the chance to celebrate interesting people and to make connections between various disciplines, to show the connections between different industries and the throughline of creative endeavors. But I don’t know. I’m not good at these “What stands out?” [questions]. It was super fun.

SB: I mean, your first issue—

DN: I just like problem solving, and so you’d have these problems, where it’s like, The Wall Street Journal is super business-y, super dude-oriented, super type A. People only read it during the week, and so it was this problem of like, how do you broaden the audience, and how do you get people to bring it into their homes on the weekend? I just like trying to solve those problems. I started there as a freelancer creating the “Off Duty” section. So, I don’t know, I just like solving problems and not sticking around and making them tick well.

[Laughter]

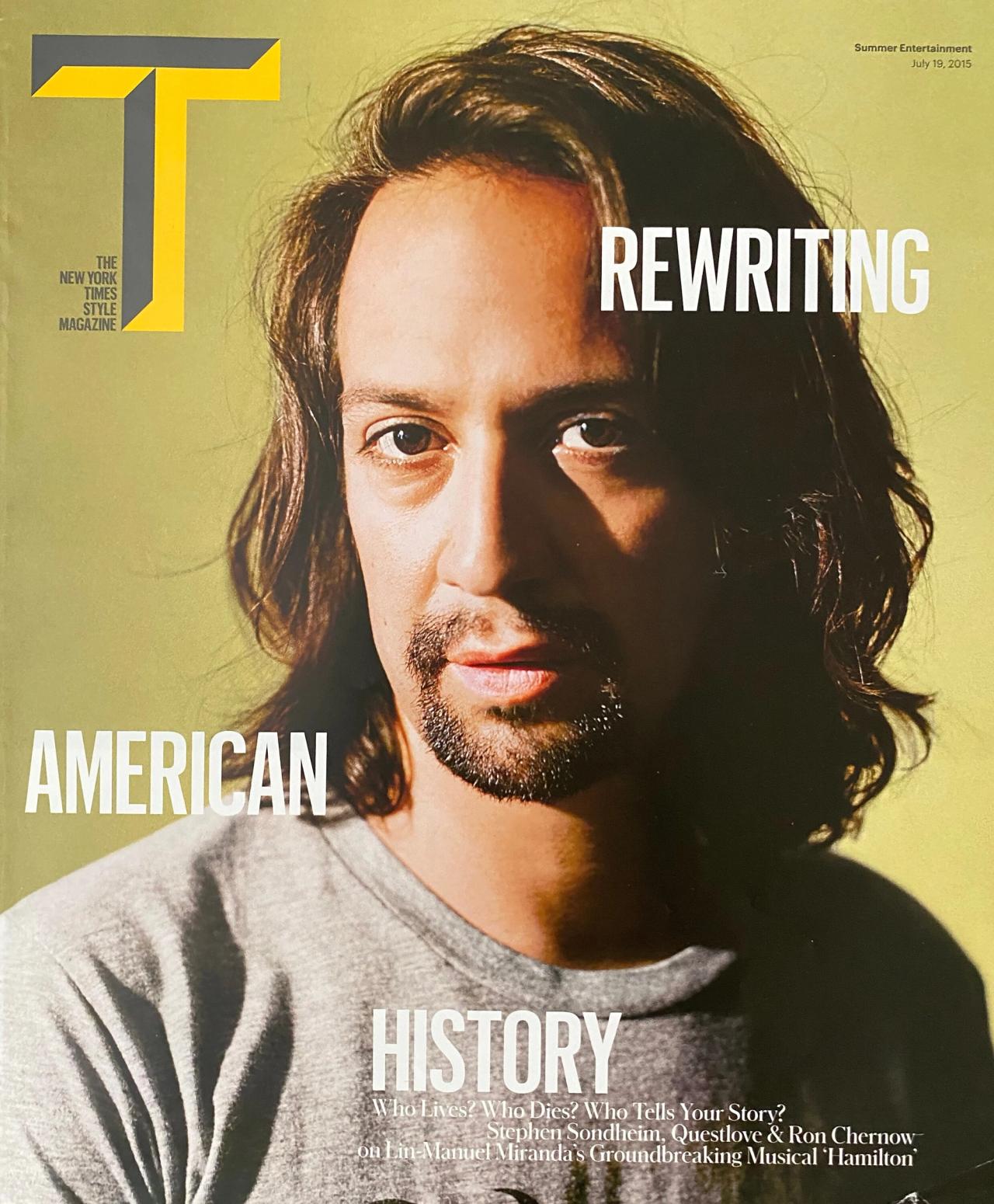

Cover of T magazine‘s Feb. 17, 2013, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

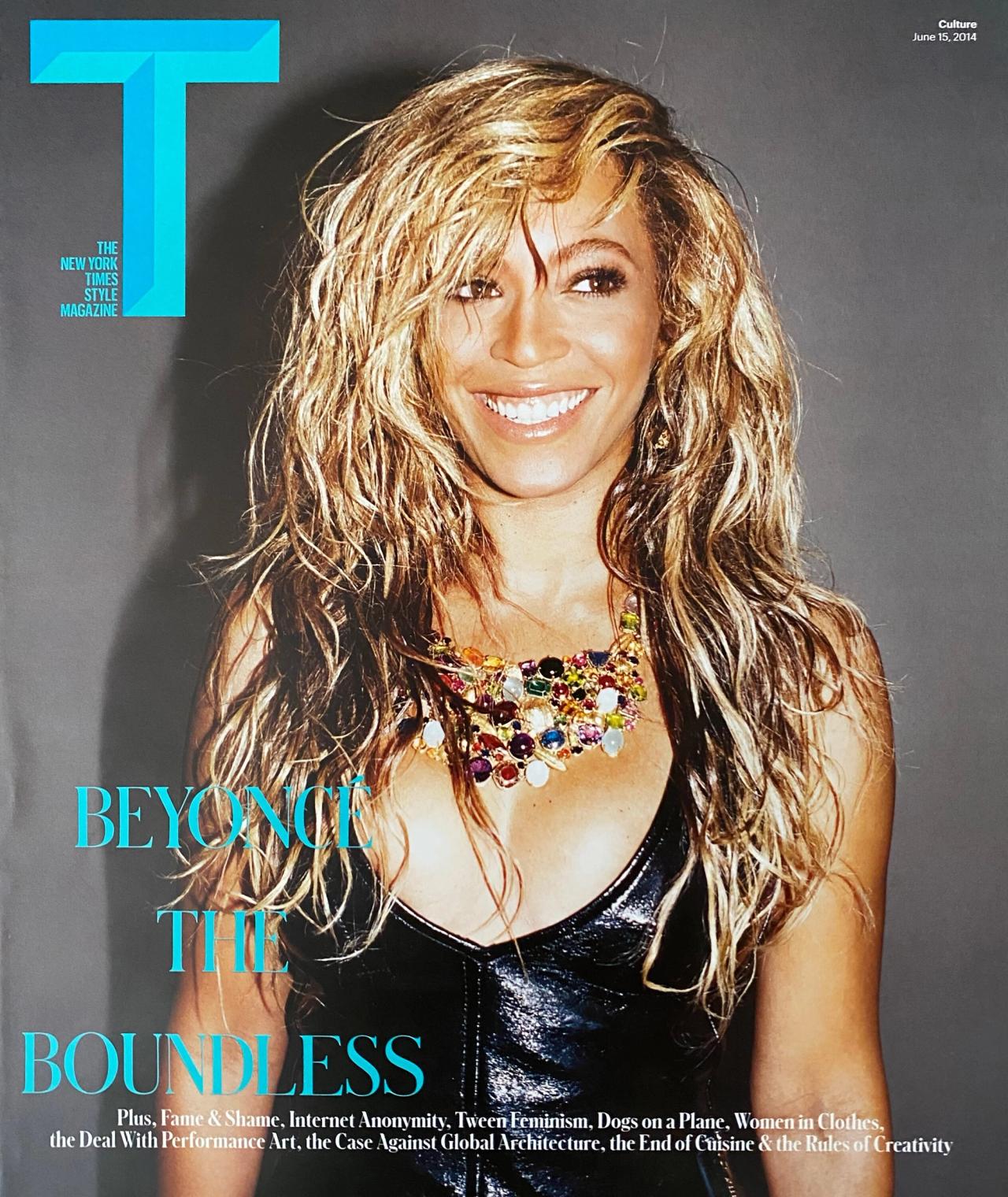

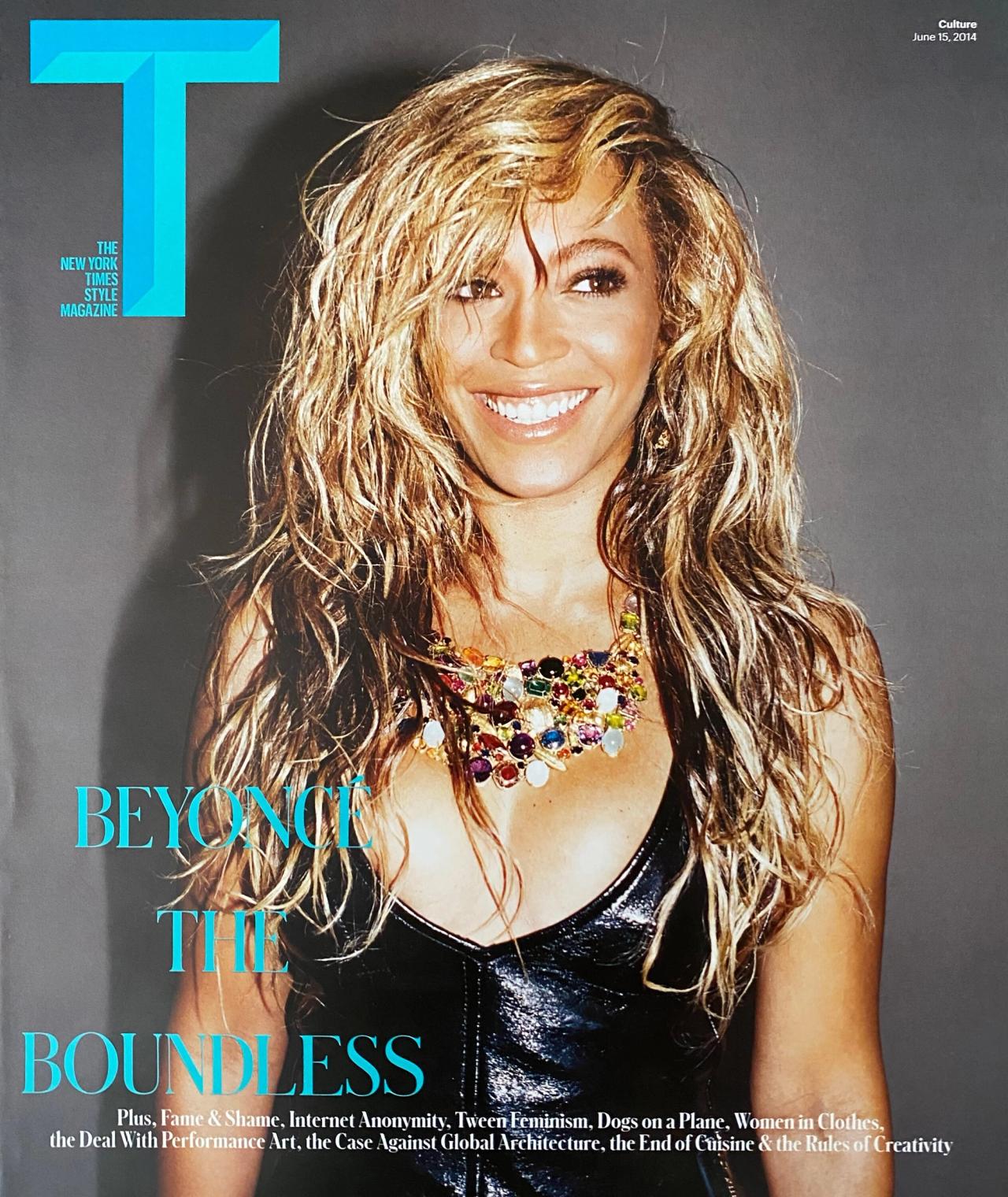

Cover of T magazine‘s Jun. 15, 2014, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

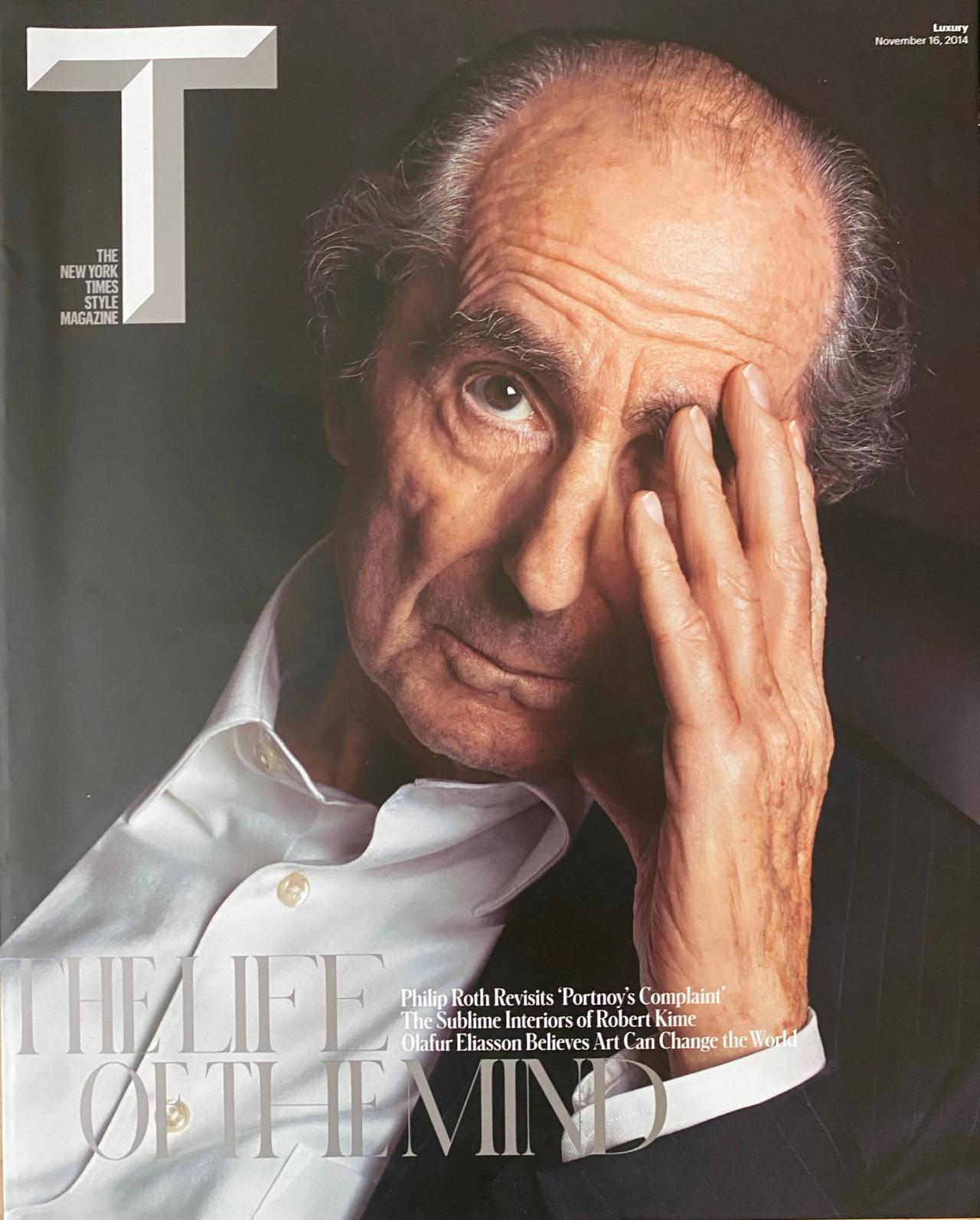

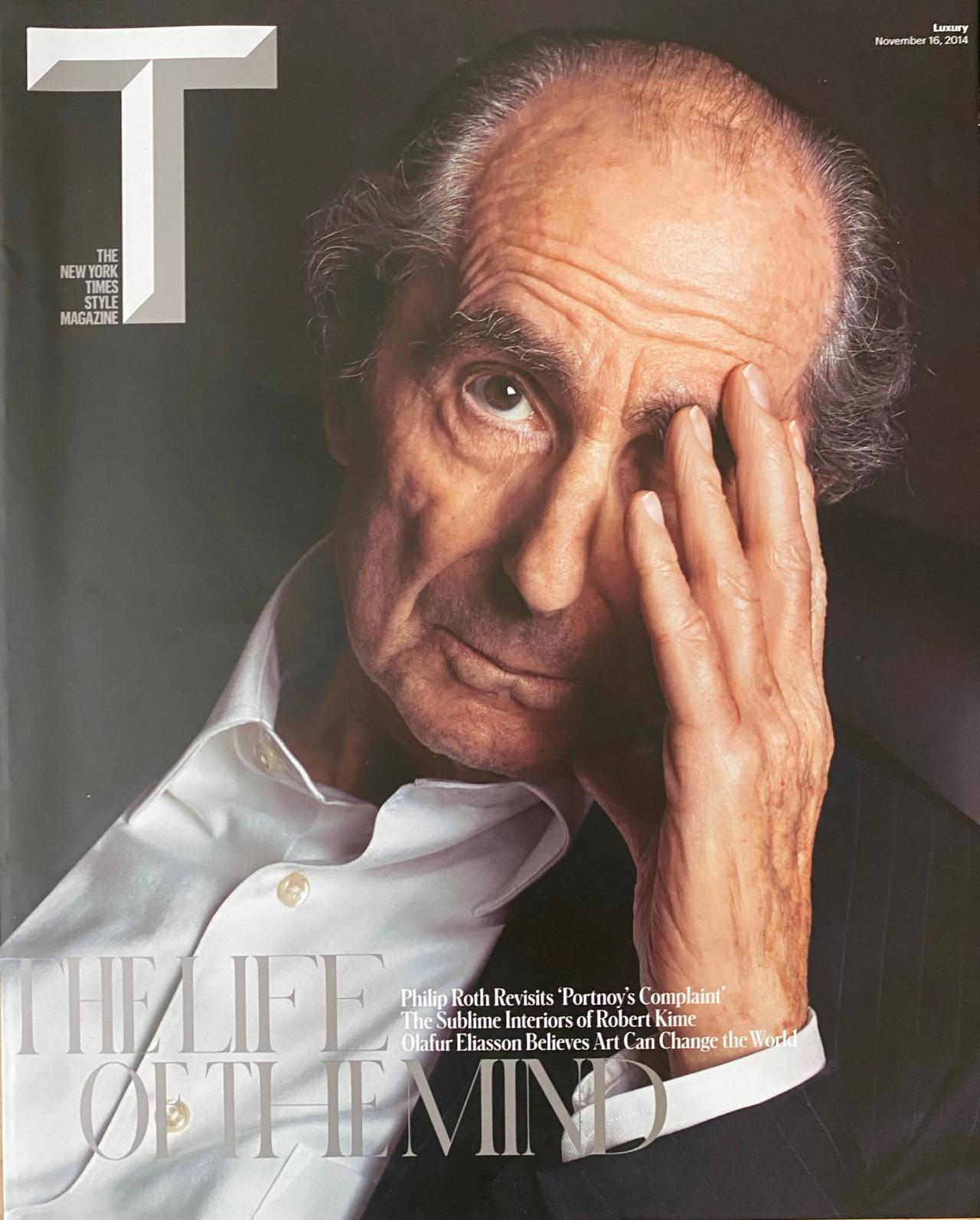

Cover of T magazine‘s Nov. 16, 2014, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

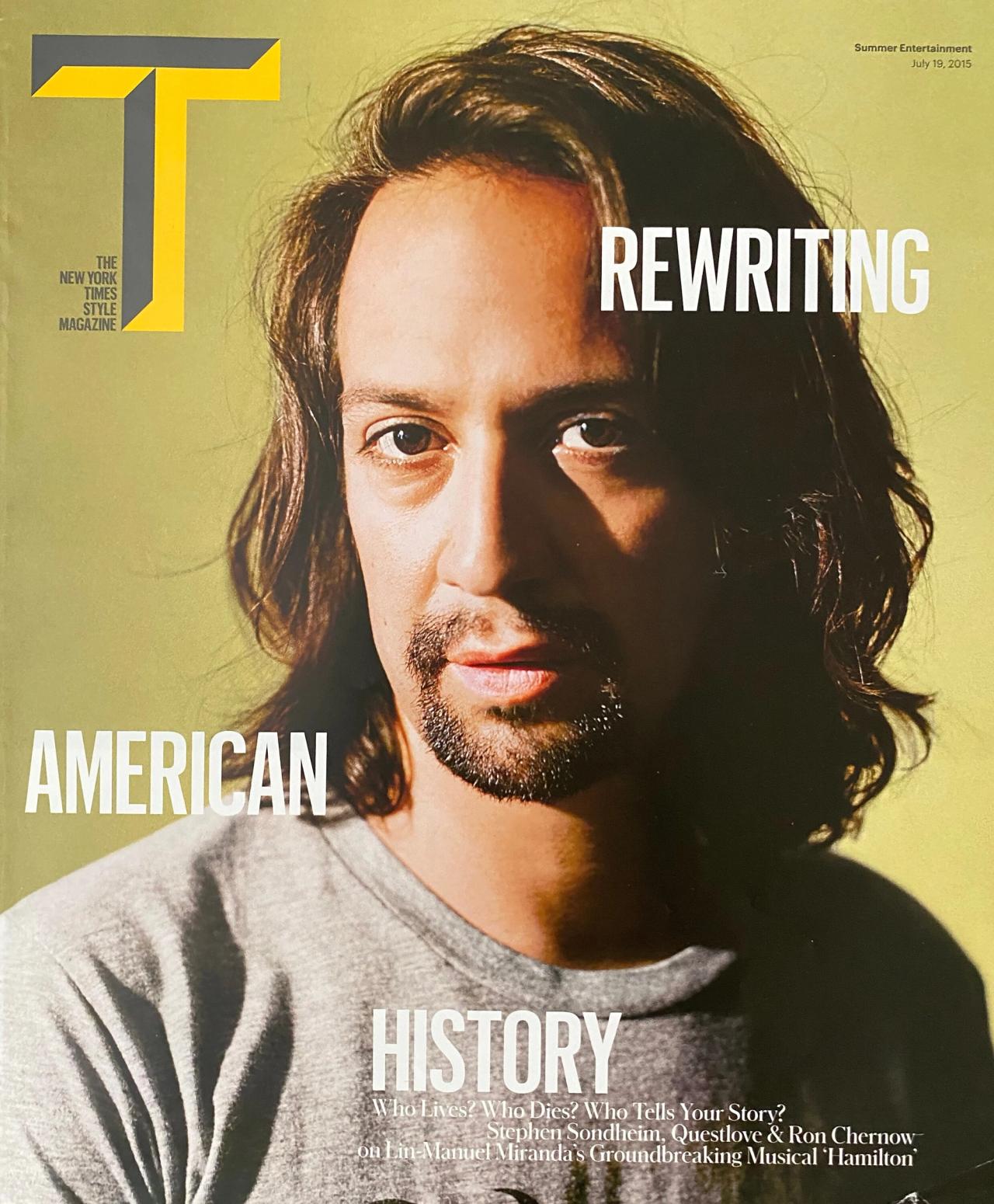

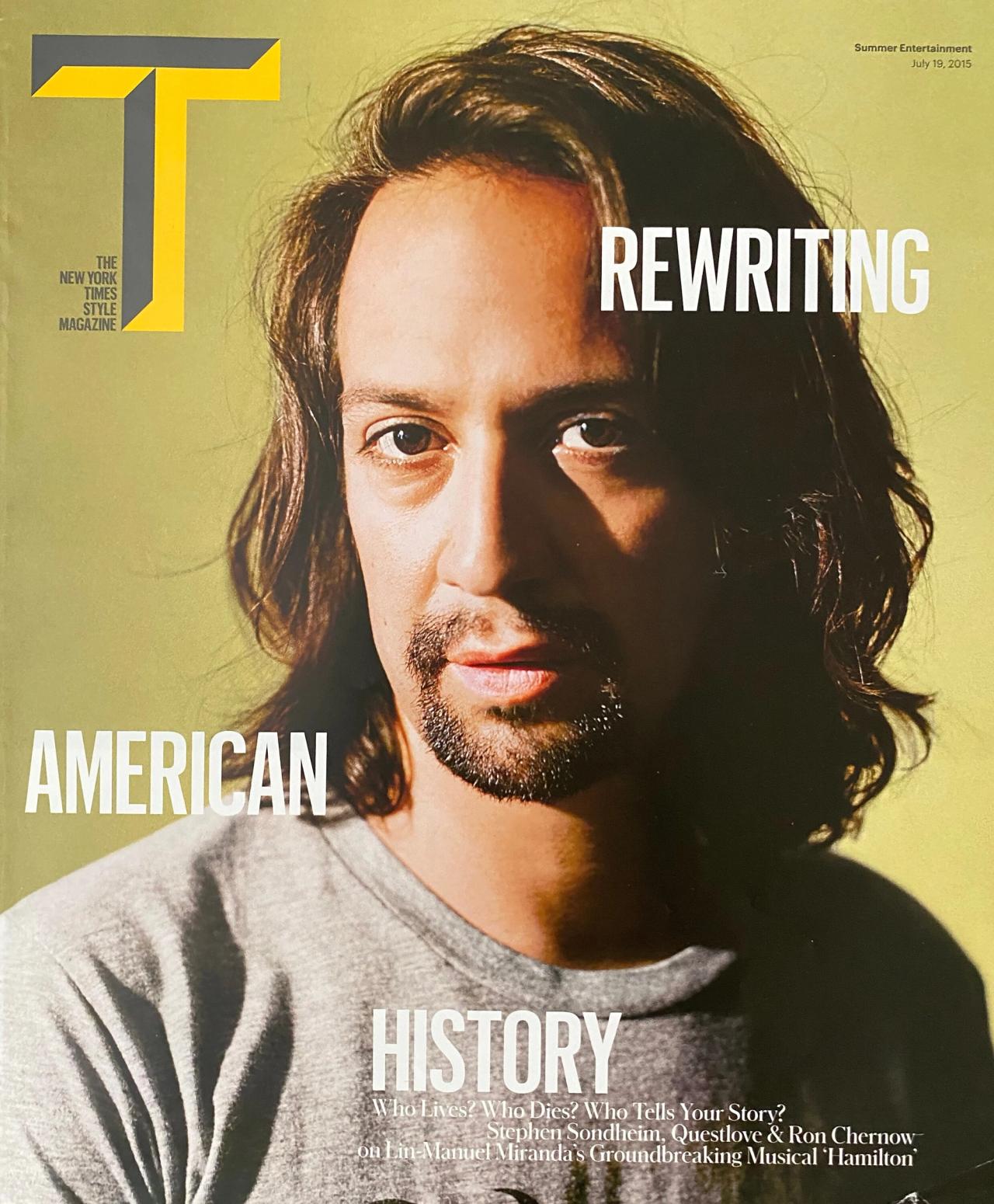

Cover of T magazine‘s July. 19, 2015, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s Feb. 17, 2013, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s Jun. 15, 2014, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s Nov. 16, 2014, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s July. 19, 2015, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s Feb. 17, 2013, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s Jun. 15, 2014, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s Nov. 16, 2014, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

Cover of T magazine‘s July. 19, 2015, issue. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

SB: There were a lot of people you highlighted during your time at T that wouldn’t get the attention they ordinarily would deserve.

DN: Well, I hate a celebrity. That’s a really weird thing for a magazine editor. [Laughs]

SB: You did put Beyoncé on the cover, but you also put—

DN: But she’s so badass, but yes.

SB: But you also put [the socialite, former public-relations executive, interior decorator, and younger sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis] Lee Radziwill on the cover, which was your first cover, and was really, as I read it, this celebration of the good life, and of aging well.

“Why is a 20-year-old cool? An 80-year-old who has lived a long life is way cooler than that to me.”

DN: Yeah. I think now magazine covers are much more democratic and diverse than they were at that time. But to me, it was like, why is a 20-year-old cool? An 80-year-old who has lived a long life is way cooler than that to me. You just have to be hot when you’re 20. [Laughs]

SB: But I remember when you did that. I had just become editor-in-chief of Surface at the time, and I was struck by that cover. I similarly went looking for these kinds of people who were 60-plus, who had a lot of wisdom, a lot of wrinkles, and a lot of perspective to share, and ended up putting people on the cover like Azzedine Alaïa, Jenny Holzer, Paola Navone, Rosita Missoni. And it was that kind of reflection of: Why do we celebrate youth so consistently and ignore all this wisdom that’s around us?

DN: Right, right. I just felt like it’s this opportunity to celebrate talent and to celebrate people who aren’t—not that Lee falls into the category of people who aren’t celebrated or someone….

SB: But yeah, your Philip Roth cover is a good example.

DN: Right. But yeah, that just always seemed much more exciting and much more fun than to put yet another celebrity…. I don’t know, I just don’t like the celebrity-industrial complex. And that was also a little bit like the fashion-industrial complex. I don’t like to be told what to do.

SB: I think, probably, your most zeitgeist-y cover, if I could pick one, was Lin-Manuel Miranda. And you covered that like right on the precipice of Hamilton blowing up. Which was pretty amazing timing.

Needleman with her husband, the journalist Jacob Weisberg, co-founder of the audio company Pushkin Industries. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

DN: When you’re early on things, you don’t usually get credit because no one remembers. But yeah, I think it was before Broadway. I just remember my husband came home from—I think PEN, the writer’s organization, had brought a group of people to Hamilton [at New York’s Public Theater, where it was running from January 20–May 3, 2015]. He was like, “I’ve just seen the most amazing thing,” and then I went to see it. And that is such a great pleasure that you can see something amazing and that you have this platform. And then people just get recycled and recycled, and you see them over and over again on the same magazines. But yeah, it sounds like you loved the same thing. Someone like Rosita Missoni, she’s been around forever, she has incredible energy, and she’s a lovely, lovely person.

SB: And somebody who transcends any one [discipline]…. When I interviewed her, it wasn’t about fashion, and it wasn’t about design necessarily, either, although we touched on that. It was kind of like—

DN: Family, love.

SB: As lame as it sounds, it was about like sunsets [in Sumirago] over the mountains in Italy. [Laughs] But it was really about time, actually. If we really strip it away, it’s really about looking at a life through time, and really appreciating what people have [done].

DN: Yeah. They’re an incredible family and they’re so close. They’re like a great, old Italian family that is not defined by their relationship to fashion and by fashion.

SB: Looking back on your media years, and now, looking ahead to what you’re working on now, what are some of the throughlines or big things that you want to continue bringing forward? What impact do you, yourself, want to have?

DN: That’s interesting. I think I’ve realized that my impact will be small, but hopefully powerful to the people around me. But I feel like I was lucky that I had a microphone for a while, and now, as corny as it sounds, it is about just how I want to spend my time and spend my days. So I know what I’m looking forward to, but I don’t know what, if any, my impact will be.

I think part of the thing of people thinking scale is so great…. I’ve always had this idea about—I don’t know if you can say this on this podcast, but—I’ve always wanted to write a book called Fuck Scale.

SB: [Laughs]

DN: Everyone thinks you’ve got to get bigger, and obviously scale is important for various things, but I think a lot of times people get more successful and lose touch with the thing that brought them into that industry or that field to begin with.

So I think I’m okay with my impact being really small and hopefully just affecting the people around me, and hopefully leaving a few of these baskets—these objects—out in the world that survive beyond me. The same way a bulb planted in the fall rises in the spring, whether you’re with it or not. I think I’m okay with that.

SB: Well, I wanted to end on this on a subject that links to this. You mentioned earlier you’re in the last third of your life, and there’s this process that happens with aging that we like to call in the design world “patina.”

DN: [Laughs]

SB: And so I just was hoping to get your thoughts on that, the value of patina, and to really kind of understand…. I think a lot of people, when they look at a piece of furniture or whatever it is that gets a little ding or a scratch, they want to brush it—

DN: Polish it up.

SB: They want to clean it, they want to—you know. And I think the lives we’re talking about, the Lee Radziwills, the Alaïas, the Rosita Missonis, they’ve lived lives full of patina. And I think that idea doesn’t get applied so much to life. People are constantly trying to be in this form of control—

DN: Of stasis and—

SB: Yeah.

Needleman weaving a basket at her friend Sarah Ryhanen’s farm, World’s End, in Esperance, New York. (Courtesy Deborah Needleman)

DN: No, I feel that, in a way, it’s too bad you don’t have the energy and body of a 20-year-old when you’re 60, because it’s all, to me, so much more interesting as you get older, in part because you’ve had relationships with people that have been going on for thirty or forty years. And that’s just incredible, to know people through different stages in their lives. And you’ve read so much more, you’ve seen so much more, you’re so much more empathetic, and, I think, compassionate, for the most part. And also, you’ve been roughed up a bit by life, so you’re more realistic about what’s precious about it and what’s not really worth getting in a tizzy about.

But yeah, I’m not ready to let it all go and stop every kind of New York lady cosmetic intervention, but— [Laughter] But I do think having a life that shows on you is an amazing thing, the same way it is with a piece of furniture. I’m looking at the amazing, beautiful worn leather on your chair, and to me, I don’t know, that’s so much nicer than a brand new, shiny bit of leather upholstery. I guess it is the same with an object of craft: It’s been around. If I’m lucky enough, an object I make will get to hang around long enough to get its own patina, and to be worn where people have used it, or to be mended, or to be passed down. That would be great. But once it’s out of my hands, it’s out of my hands. But I do love the idea of stuff getting worn and used, and patina.

“I do think having a life that shows on you is an amazing thing, the same way it is with a piece of furniture.”

SB: [Laughs]

DN: Yay, patina. [Laughs]

SB: Deborah, thank you so much for coming in. This was a pleasure.

DN: Thank you, Spencer. It was really, really nice to talk to you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on May 10, 2022. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity by Mimi Hannon. The episode was produced by Emily Jiang, Tiffany Jow, Mike Lala, and Johnny Simon.