Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

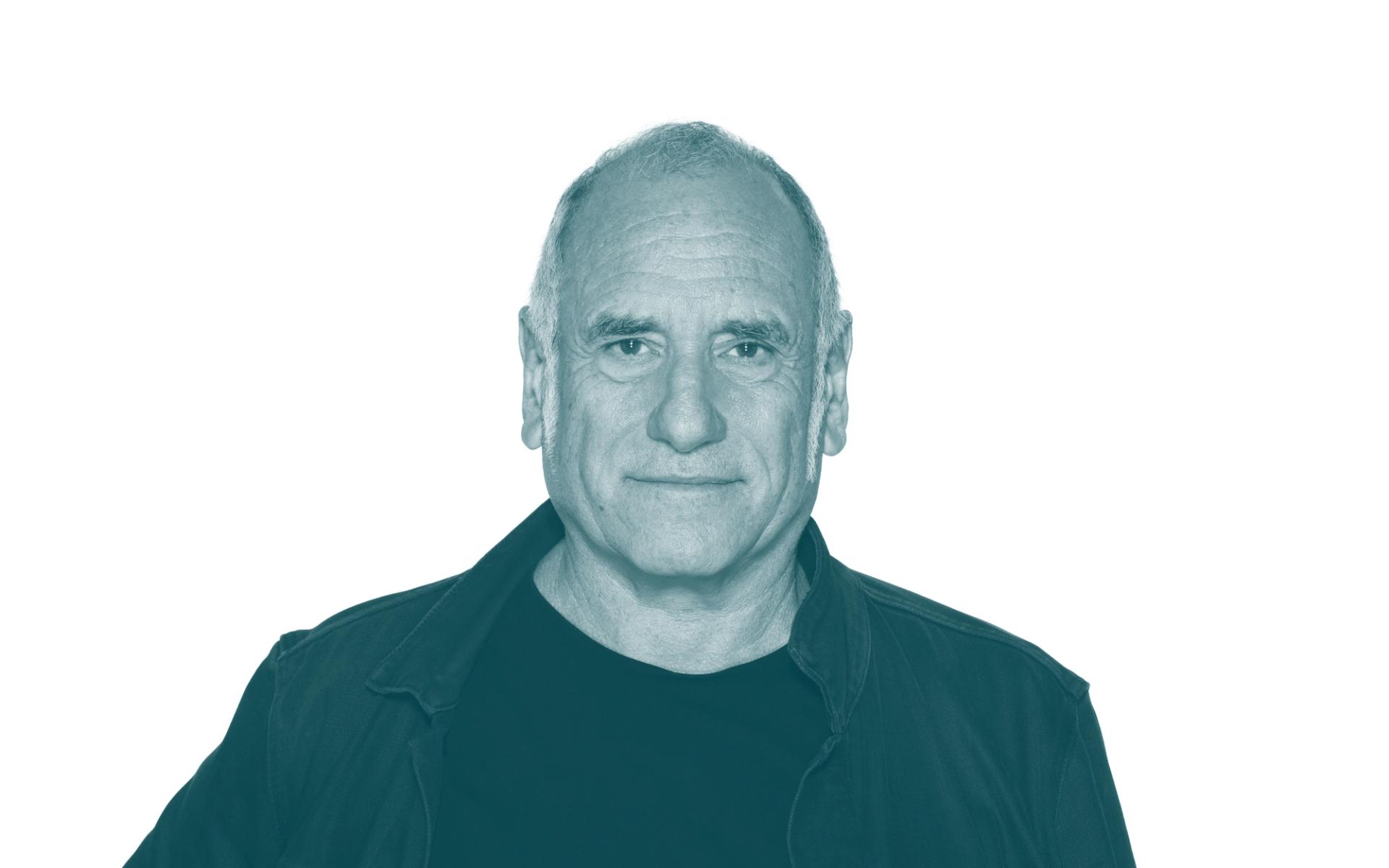

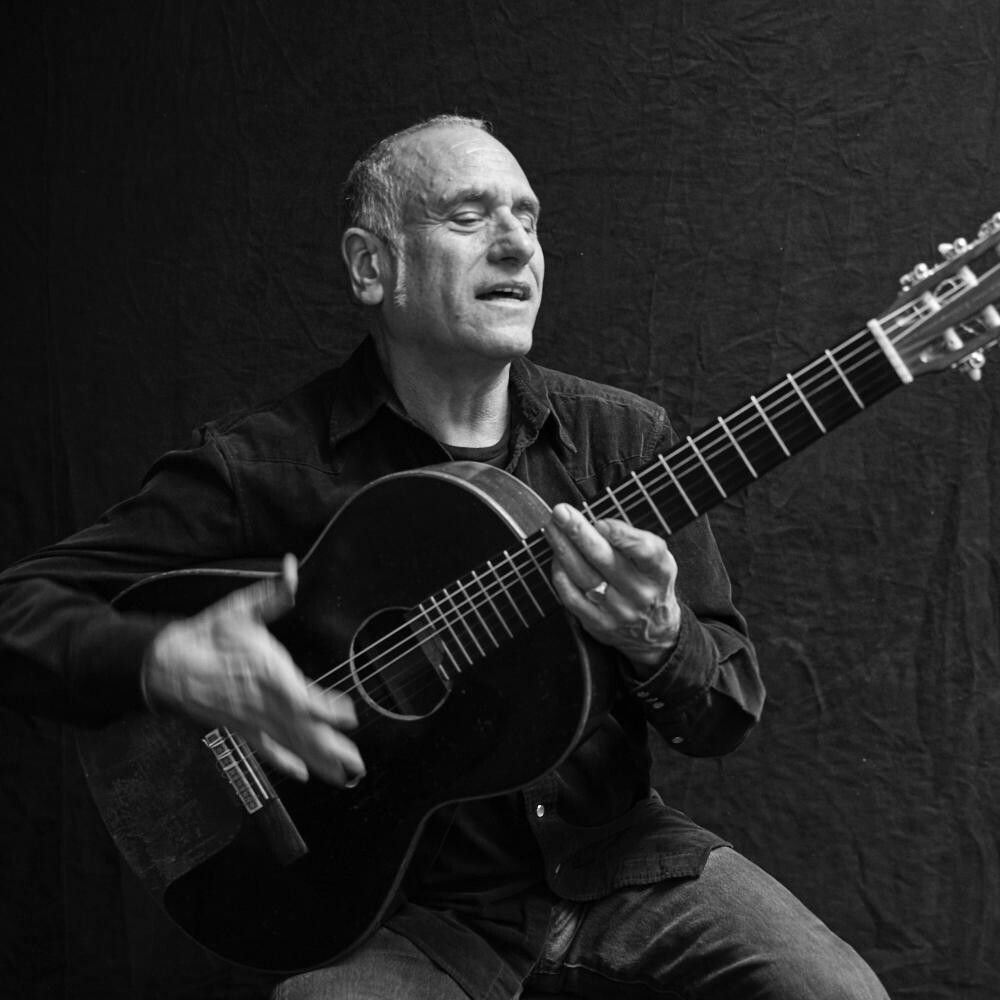

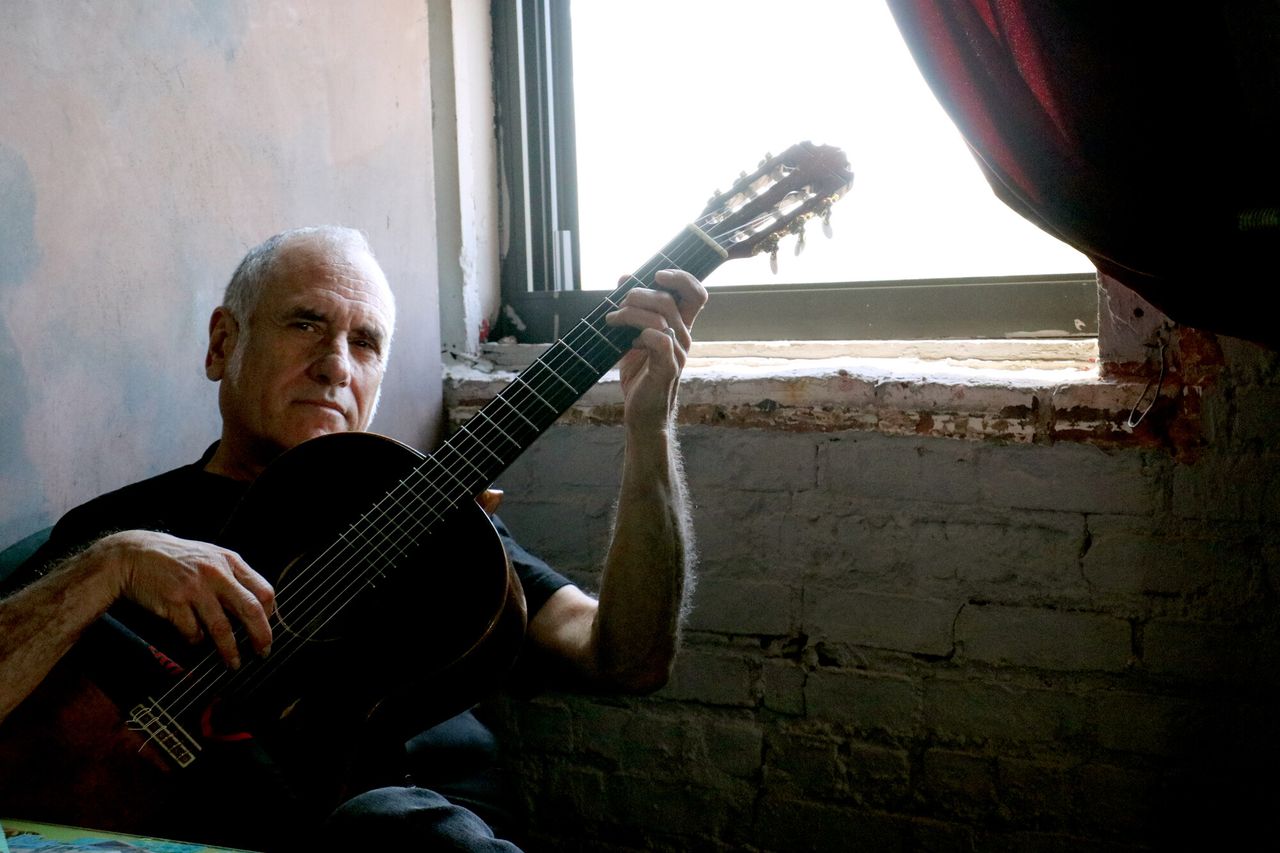

David Broza.

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Welcome, David. Thanks so much for joining us today.

DAVID BROZA: Thank you. I’m still getting myself acquainted with you, and with the room, and the great morning light.

AZ: So, I’ll start light. You’ve said that with your music, you “want to be evocative, not provocative.” I want to start there. How do you think about that balance, especially in the arena of politics and people? Which is what you deal in.

DB: Well, when I say I want to be evocative, it means I have to be aware of the fact that there are always two sides to every coin. To declare that I have an opinion, and I rule out anybody else’s opinion, who doesn’t agree with me, for me—I’m not saying it’s the way to be—but I would recommend that one would respect others. And in order to respect others, you have to know the other. If you have to know the other, you have to be in dialogue, or some relationship. Once you know the other side, then you can decide on which side you want to be, but you can’t disregard.

And so being evocative is, I want to be profound, thoughtful, evocative, inspirational. But also, provoke does not mean a violent act. To provoke is also to inspire. So you provoke, you bring a thought into someone’s mind. He’s unexpecting. For example, when people say “politics.” In the first opening line, you want to be light. But then you go, “You said the word ‘politics’? Okay.” He’s just tied a cement block to my fanny and threw me into the Hudson River. Let’s try and float with that. [Laughter] No.

“To provoke does not mean a violent act. To provoke is also to inspire.”

But, imagine that I do a lot of work with Palestinians. And then, I’ve got immediately an audience that loves me, and says, “We don’t want this guy feeding us with his pro-peace and Palestinian lover….” All of these little things that they say, they put clichés on you. And yet, if you do it in the right way, and you do it in an evocative way…. For example, I’m anti-boycott, for the same reason. Because once you boycott, you build a wall. You don’t even put a lock on the door. You just seal it and say goodbye to the other side. That’s it. You’ve decided the fate of your life, and the other side’s life in regards to where you stand in the picture. But if you keep the door open, there’s always a chance something will change. And so, if I’m confusing the listener, it’s not because I’m confused. It’s because it takes a little bit of dancing.

AZ: Yeah. I mean, what we’re really talking about—

DB: It’s a tango.

AZ: It’s about conflict resolution, and empathy.

DB: Empathy and openness. So, I will do my work. And then, if I get booked to play or invited to play in a West Bank settlement of very right-wing zealots, I take it. I don’t give them any discounts. I will not be censored. But I will listen to them as well, if there’s any room for us to talk. Normally I leave space for that. I love meeting the audience after shows, and having conversations. And I think when people are heard, the element of being an enemy of yours, or ruling you out, is out of the picture.

AZ: Yeah, because it’s humanized.

“When people are heard, the element of being an enemy of yours, or ruling you out, is out of the picture.”

DB: You can be two sides of the field, complete enemies. But it’s like in soccer: you’ve got one ball to play with. You’ve got to get that one into each other’s goal. There’s always going to be one winner. The next time, you might be the loser.

It’s the same in politics. One day is up. One day is down. If you look at Alsace-Lorraine, if you look at all kinds of borders in Europe, one day they’re Polish; the next day they’re Russian. Another day they’re French; the next day they’re German. Things move around. Things change. It’s very sad. Look at Ukraine now. Donbas. East Ukraine is going to become Russian, most probably, and anybody who doesn’t want to live there will have to find a way to migrate to Ukraine. These are things that we’re watching in real time now. And you try to help, but you can’t stop what is bound to happen.

AZ: Yeah.

DB: Now, we don’t know what’s bound to happen.

AZ: No. But it brings me to possibly your most famous song that you wrote with the poet Yehonatan Geffen.

DB: Yes.

AZ: Which is actually your first song.

DB: True.

AZ: It’s amazing. “Yihye Tov,” “Things Will Get Better.” What was the genesis of this song, and what was happening in ’77 when you wrote it? What was the arena? What was life like both personally and broadly?

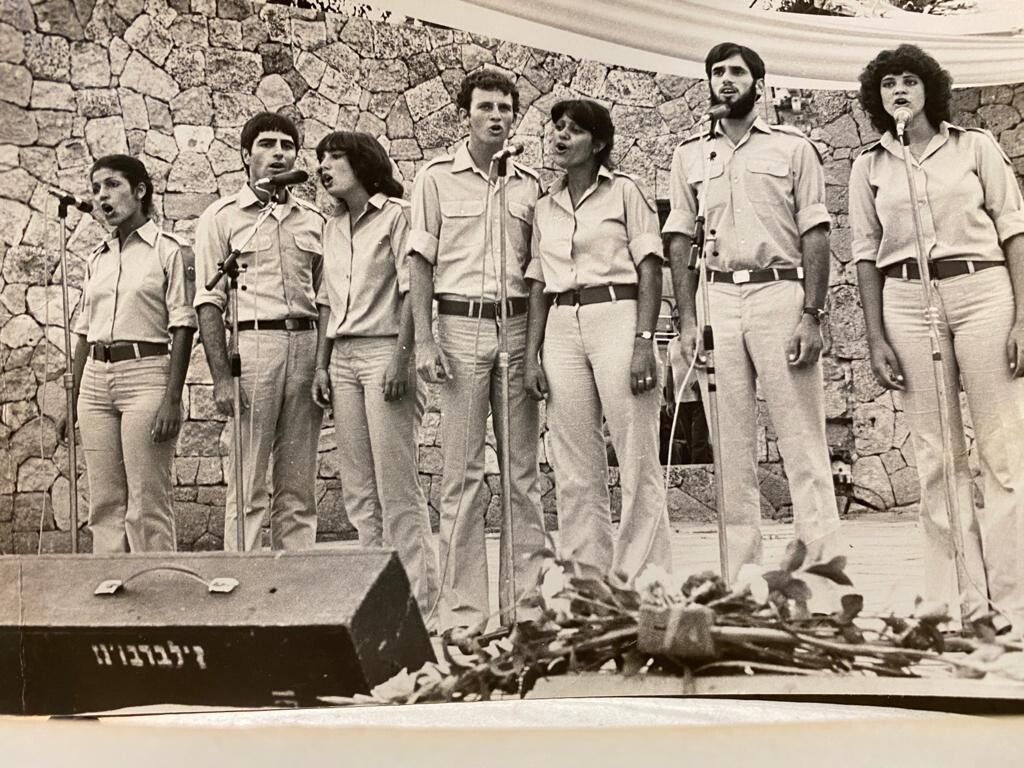

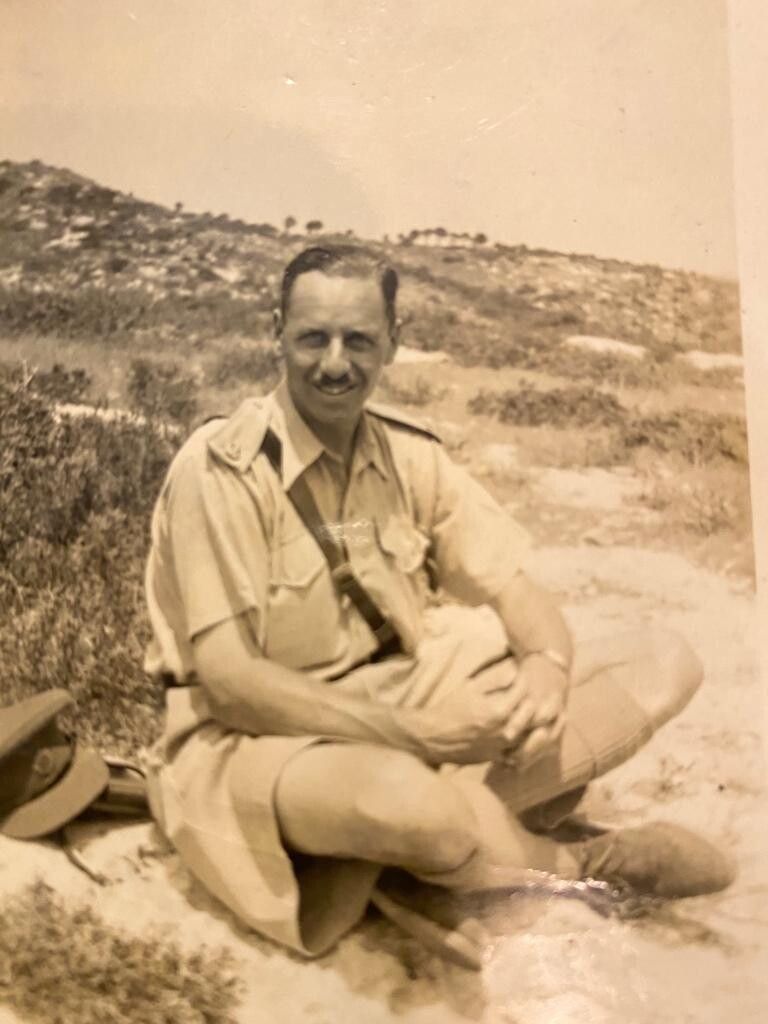

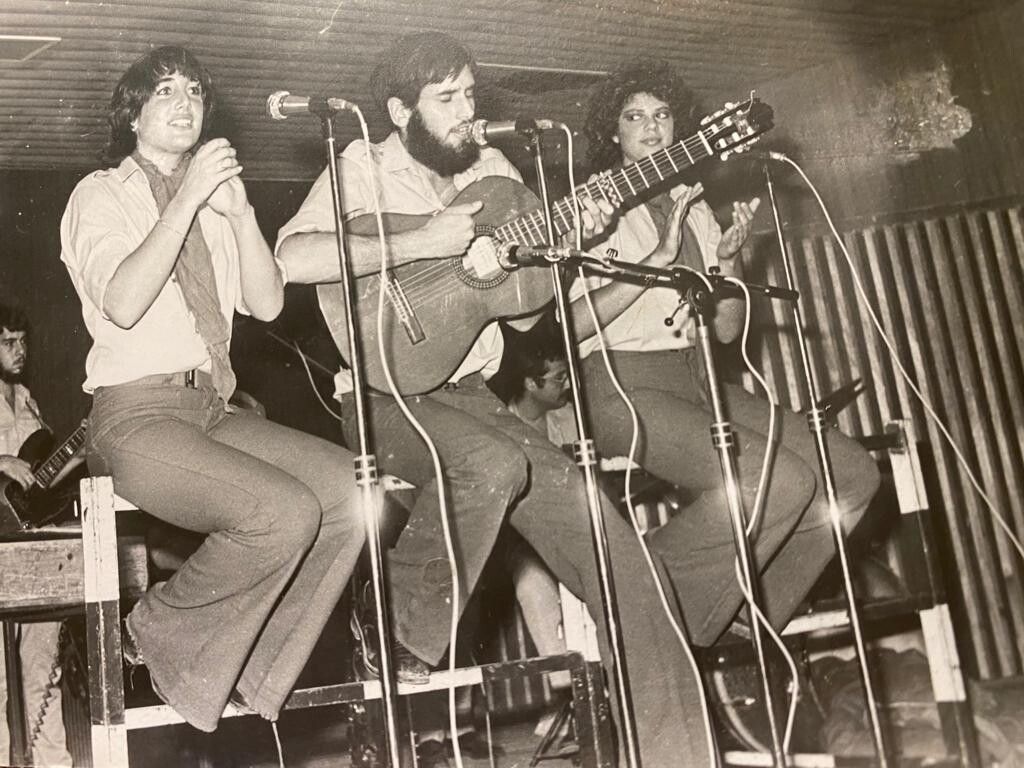

Broza as part of the entertainment corp in the Israeli army. (Courtesy David Broza)

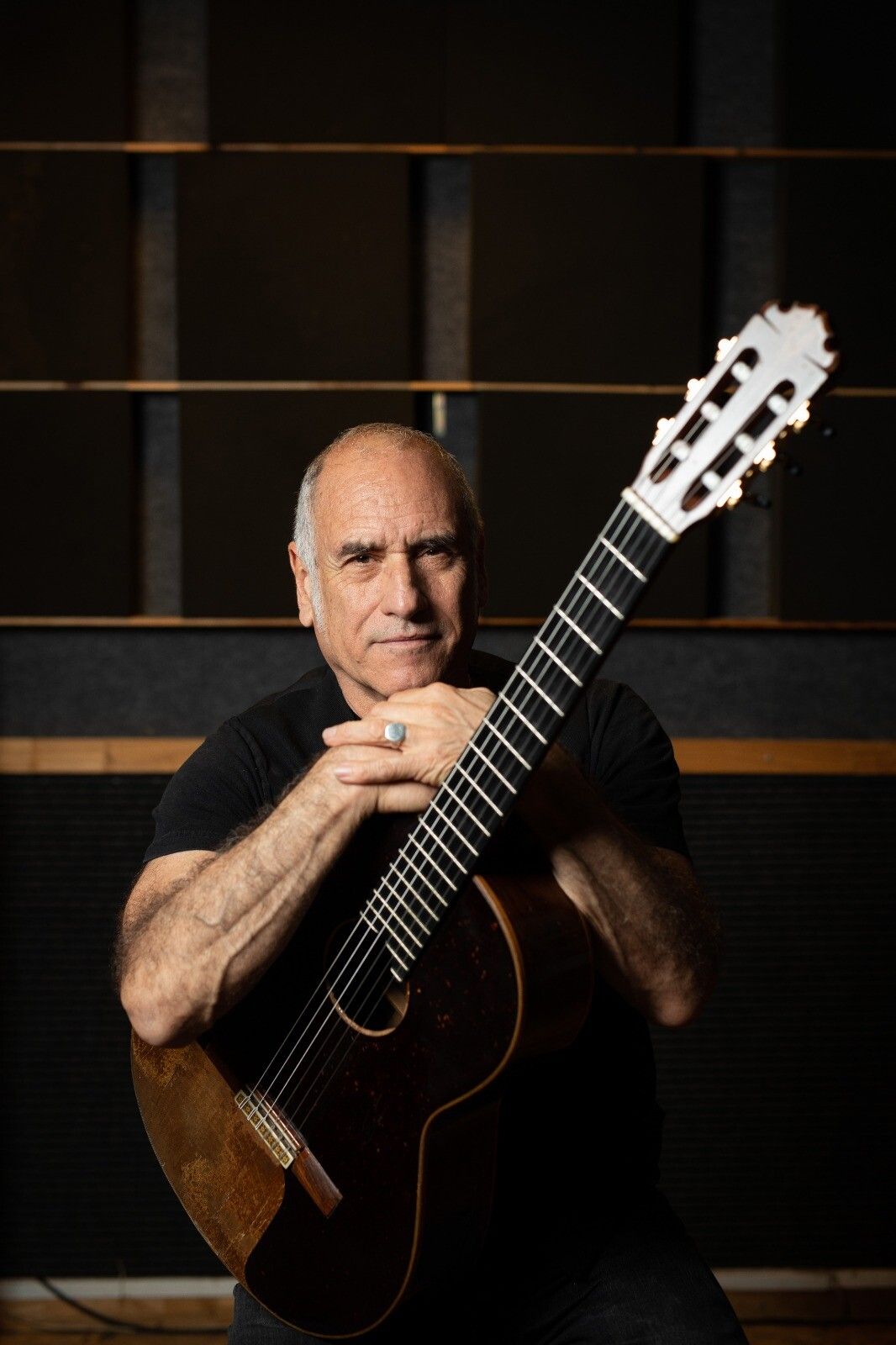

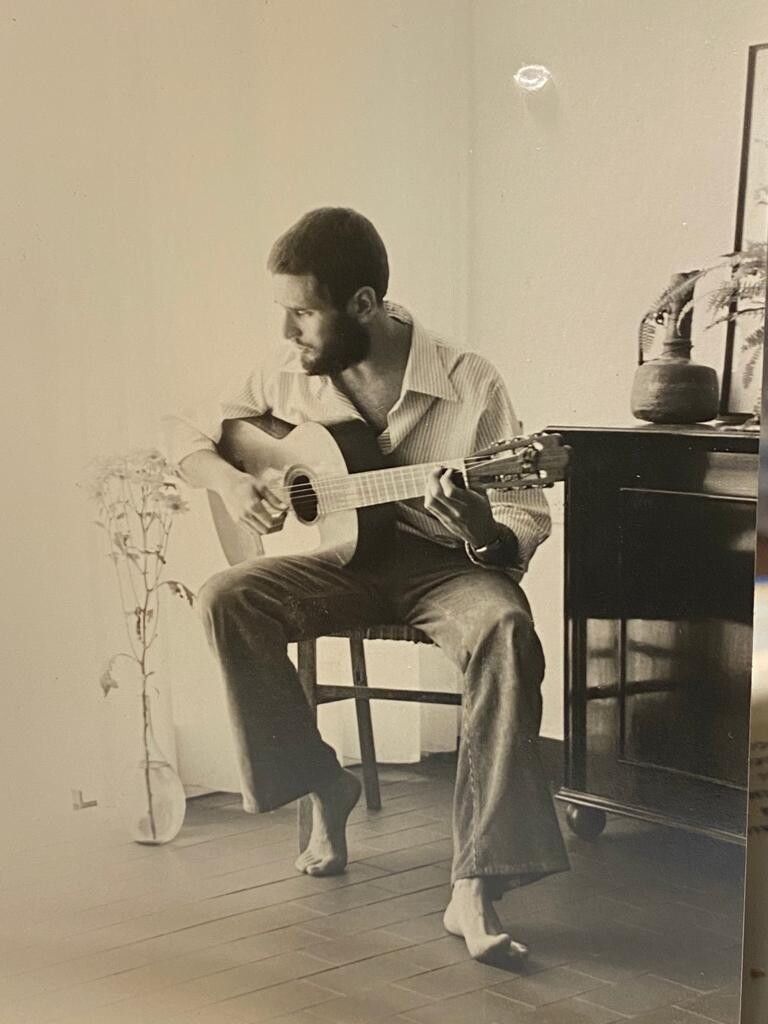

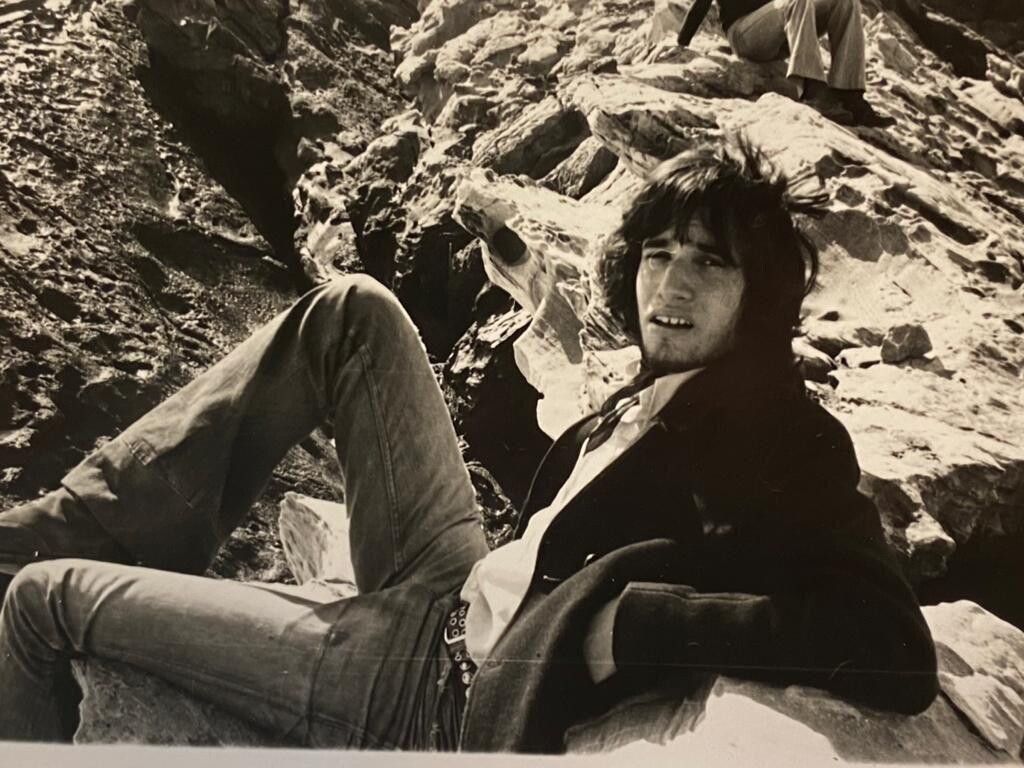

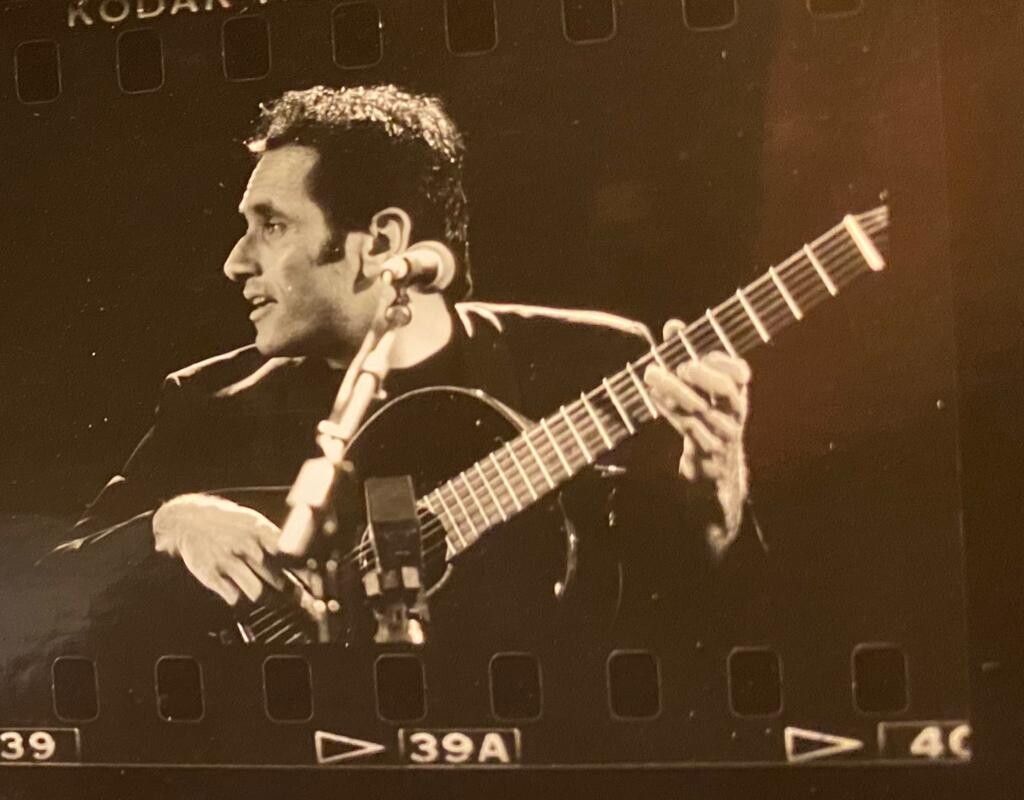

Broza at age 22, just after completing his service in the Israeli army. (Courtesy David Broza)

DB: Well, to start with, I was 22. Life was beautiful. I was just out of the army, serving three years. I was like in the cartoons, the sad sack. I was a private. I was nothing in the army, but I made my time valuable. I painted. I’d been a painter since I was a kid. I played guitar. I performed at night. I had to be a guard in the base somewhere. There’s a reason why I was not in some combat unit, which is what I wanted to be. It was for what they call a profile, when you enlist. They check your health. And they found a fault in me—asthma—which I had not declared. They wanted to court martial me immediately, because sometimes people enlist, and then a month later—and they know they have asthma—they find the army is the culprit and then they become supported financially. They use it.

For me, I just had it when I was a kid. I had forgotten I had it. I didn’t even think—I was a sports guy, athletic. Anyway, they said, “Okay. In your case, you’re going to be stuck with us for three years. We’ll put you as a guard.” I started playing at the gate, playing guitar. And then I was a dishwasher in a restaurant. I’m giving you a brief. After washing dishes at two in the morning, I would break the last plate, and I would come out with a guitar, and play it. Everybody in the bar would wait for two or three o’clock in the morning, when they would hear the plate break, and they know the guy’s coming out, and I’m going to play until morning. Then I got offered all kinds of jobs. All kinds of gigs. I was covering other people’s songs. It was just fun. I was a painter, I was an artist, and I was a soldier at the time.

When I finished the army, I didn’t have a penny to my name. My parents couldn’t help me financially, but they did have a house in Tel Aviv, which was being constructed. But they didn’t have money to finish it. So I lived in it with no water, no electricity, no floors, but it was still four walls and a roof. And everybody in town heard about it. They’d already heard about it when I was in the army, and all the musicians would come around, and hang out, and play, and jam. It was amazing. A private house in the middle of the city.

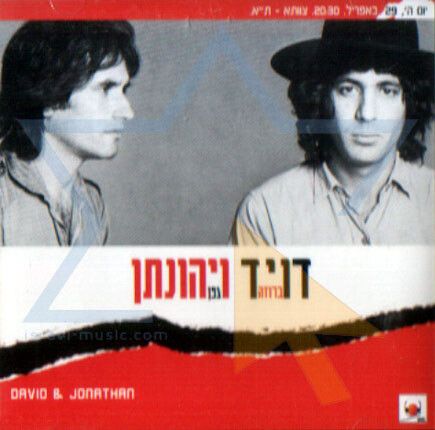

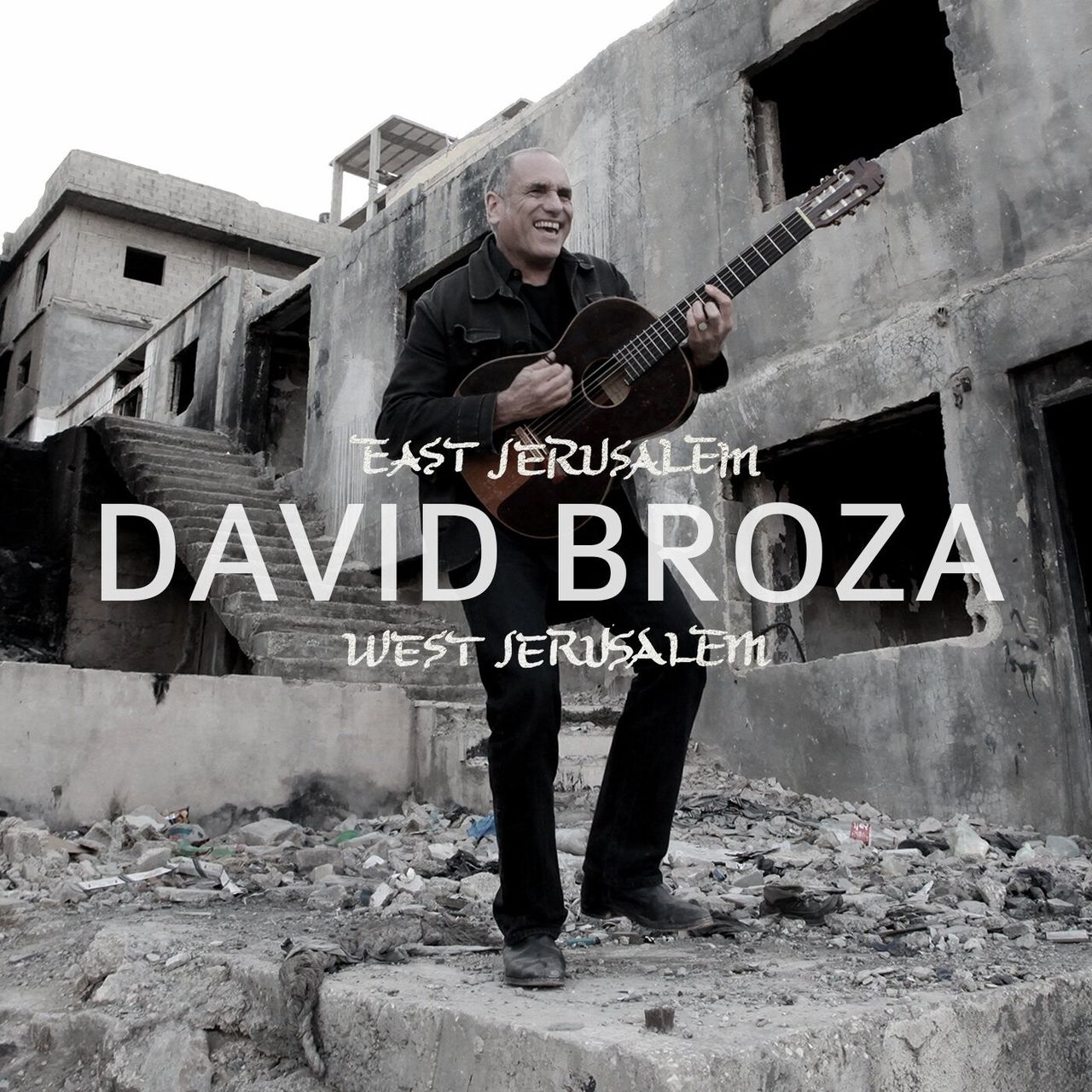

Cover of Broza’s album David and Jonathan (1982) created with Israeli poet and songwriter Yehonatan Geffen. (Courtesy David Broza)

So I’m finishing my military, and I’m out of any form of disciplinary life. And I get a call from Yehonatan Geffen, this great poet, whose show I saw before. He’s like the Lenny Bruce of Israel. Very controversial. And I loved Lenny Bruce. I saw the show, and I saw the musician. I was with him. The musician got sick, and they need a replacement. They called me and asked if I could replace him. They don’t know for how long.

Turned out the musician could never come back again. His nickname was Churchill. Klepter was his family name. Yitzhak Klepter, an amazing guitarist and songwriter. So I took his place in the show, and I was given forty-eight hours to learn the entire show. And I get on stage, the most prestigious stage in Tel Aviv—Tzavta, it’s called. This is September or October, 1977. A month into the show, Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, surprises everyone and lands in Ben Gurion Airport and pays the first visit of an Arab leader with a peace pipe, and meets [Menachem] Begin and his government—

AZ: To make the famous photograph.

DB: That’s unreal. Me and Yehonatan Geffen are looking at each other. We’re looking at the news as they unfold. And he’s jotting down, writing something on a piece of paper. It’s a poem. He hands it to me and he says, “Listen, you better get going with life, do something good. And I’m giving you, again, forty-eight hours. You’ve got to come up with a song. Write a melody to this.” And this was “Yihye Tov.” So this is the beginning. This is the start.

Now “Yihye Tov,” “Things Will Be Better,” talks about the time. About the time when kids, as still today, go to the army with their parents. Now I am the parent. My parents were telling me, “You’ll probably be the last generation to go to the army. There’ll be peace very soon.” Not knowing that there’s going to be peace, but only with Egypt. So the promise keeps going. But the song tells of that: how the kids go to the army, come back, and nothing changes. Our government is made up of generals, militant people, and military people. Whether they’re pro peace or not, whatever, they are all military.

AZ: It’s their job.

DB: At least by discipline. Which is also a good thing, if you take away the wars. That’s the song. At the end of every stanza, there is the chorus that says, “Well, but after all this, generals come, generals go, Anwar Sadat arrives, he tells us to leave the conquered territories. If you do, then we will have conclusive peace. But everything, at the end of the day, it’s with you that”—you know, I talk to the woman I’m with, or somebody I love—“and tonight, I’m staying with you.” As a matter of fact, I once did it with Jackson Browne, and we translated, [singing] “And it’s alright./It’s okay./Sometimes I just feel down./But tonight, my love, tonight, love will come around.” Something like that. We kind of translated it and hit it right on the nail. When we did it, we performed on at—

AZ: At Masada.

DB: At Masada in 2007.

AZ: Yeah. At like five in the morning, or something.

DB: The show starts at three, that’s a regular. Because I did it for thirty years. Starts at three until the sun is in the middle of the sky, which could be seven o’clock.

AZ: Right. So thirty-five years later, the song is still incredibly relevant to people.

DB: Forty-five years later.

AZ: Forty-five years later.

DB: Even more.

AZ: Amazing. What are your thoughts when you think about that? The power of art, and how meaning can morph and change over time. That song is written in the moment of Sadat arriving in Israel, but it holds a certain relevance now in the exact same way. Is that what makes a song successful? Its ability to morph and change?

“I don’t know that a song can change. But it can change one’s mood. It can unite people as they sing.”

DB: That’s a great point. I started making a movie, a documentary about the power of song—like “Blowin’ In The Wind,” like “Biko,” Peter Gabriel, South Africa. Like “Yihye Tov.” I don’t know that a song can change. It can change one’s mood. It can unite people as they sing at an event. And I know that it does that. When I sing it in Israel, all these forty-five years. I can sing it three, four times a day. Same emotion comes up. The same hope. It’s like a prayer. It’s like a mantra.

But I’ll tell you, that song came out, and was immediately played four or five times an hour, on every channel in Israel, every radio station, then television. Just then, when President Sadat arrived in Israel and Menachem Begin, then the prime minister, could not get his party to support the peace initiative, they were concerned. They were very right wing. This is the difference in Israel between right and left. It is not so much in the social arena, in how to distribute money to health and to education. That also is a problem, but it’s more [about whether to] conquer territories or not conquer territories. Do we stay in and claim that this is part of the old ancient Palestine, which is Israel now, et cetera, which is what the zealots are forcing and proving?

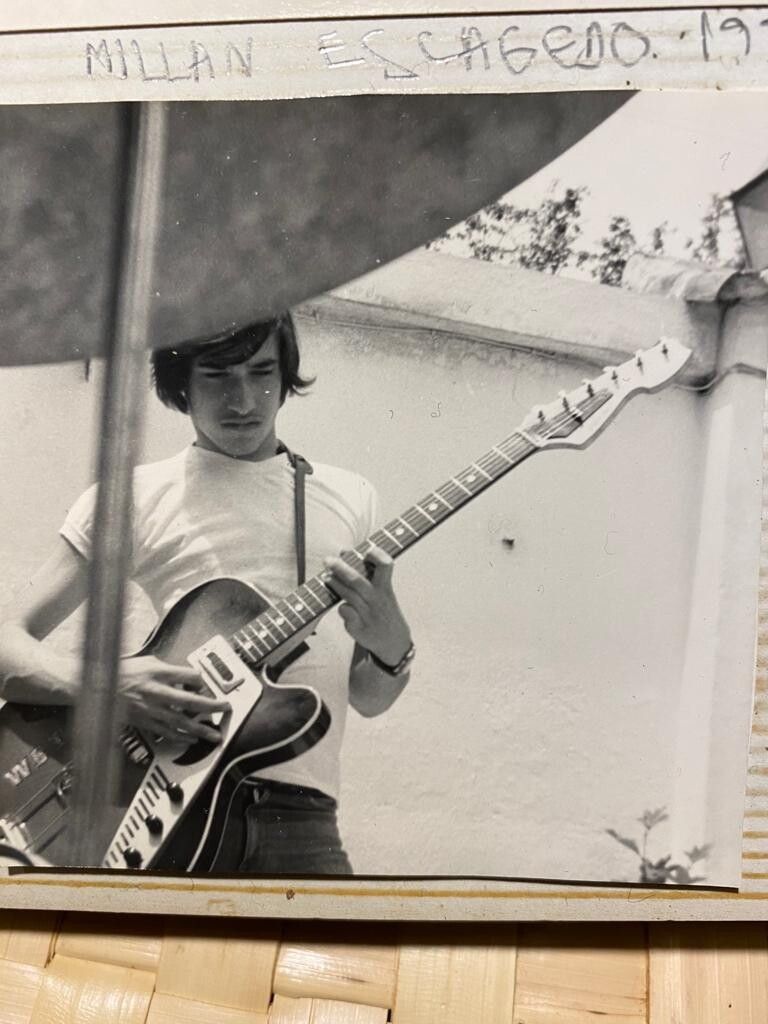

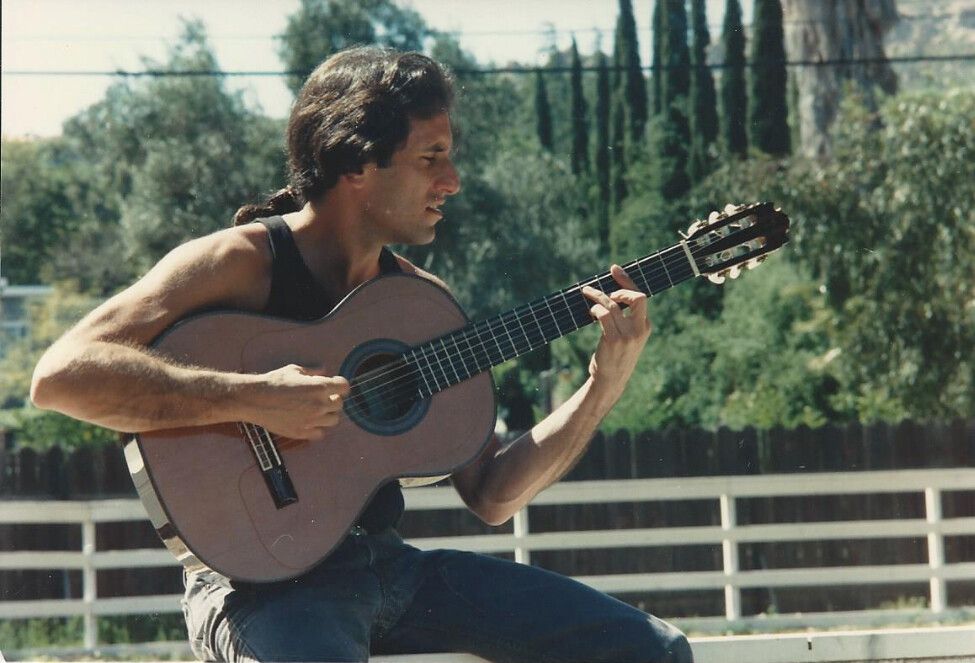

Broza in Spain at age 18. (Courtesy David Broza)

Back in the day, a group of activists got together and started a movement called Peace Now, Shalom Achshav, and they needed a song. Because they were doing not protests so much as manifestations, in support of Begin—in every corner and every square, in every town in Israel, all the way from the south through the north, including Tel Aviv. So they called the 22-year-old who’s singing. Also, being the fact that I grew up in my teenage years in Spain, between 12 and 18, till I went to the army. I grew up under [Francisco] Franco, which enhanced my understanding of life under dictatorship, made me more into an anarchist, an activist, a provocativist, or whatever it is.

AZ: Provocateur.

DB: Provocateur. Correct. And I follow these great artists. Joan Manuel Serrat, the greatest songwriter in Spain, makes an album dedicated to Antonio Machado, who died while running away during the civil war from the Franco forces. Miguel Hernández, who was jailed and a poet, another album that Serrat does. Paco Ibáñez does the songs of [Federico García] Lorca, who was assassinated by the Falangists, by the Franco supporters for whatever reasons. We can discuss that also one day.

AZ: Yeah.

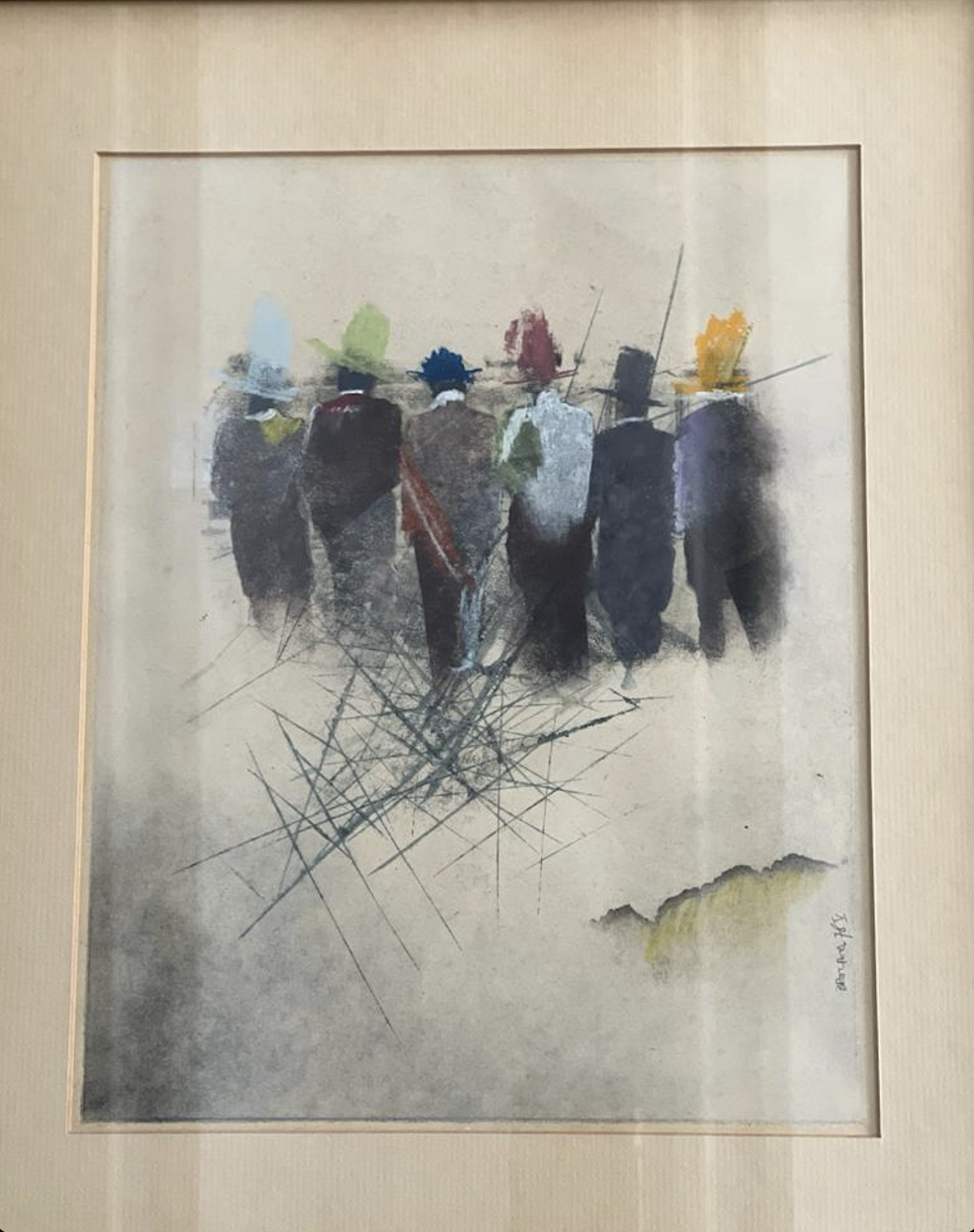

A painting by Broza. (Courtesy David Broza)

DB: But all these poets who had obviously instigated, and provoked thought, and expressed freedom. Suddenly I realize, I have this gift. I’m becoming a musician, and I have not committed to becoming one yet. I’m still a painter. All I want to do is paint. But for now I don’t have money. I’m out of the army. This is a great job. I love Yehonatan Geffen. We become close friends, and here’s my song. I’m being approached by Shalom Achshav, Peace Now Movement, and I joined them. There’s only five of them, and now there’ll be six. We go from town to town to town. By the time we get to Tel Aviv, there’s eighty or a hundred thousand of us at the square. Menachem Begin can fly to Camp David, and sign the first peace accord with an Arab country, with Egypt, the largest of them.

You asked me if the song has anything to do with it. No. But the song was definitely in the air. The song was definitely part of the glue. The song was definitely something that united all the voices into singing “Things Will Be Better.” It’s a song of hope. So even now, in 2022, unfortunately, it’s still very relevant. And even if I sing it in the deep south, in Mississippi…if I sing it in the Midwest, if I sing it down in Texas, if I sing it in California, sing it down in Argentina, Brazil, you name it, Sydney, Australia—anywhere, any corner of the world, wherever I take it, I bring with me that feeling. Because this is what I will sing, even if you don’t understand Hebrew.

AZ: They say that emotion travels faster than logic. And you’ve used an emotional lens through which you deliver these messages, which is why I think your work has resonated for so long: because there’s an under story, and a mirror, to what’s happening in culture, but it’s delivered through emotion. That’s where it leads.

DB: It is. And my friend Yehonatan Geffen also doesn’t shy from throwing at me a new verse just about every year. So this is a never-ending song, you know?

AZ: It also seems that your own experiences change the filter through which you perform them.

DB: Every day. And so—

AZ: So it is a new song whenever you play it in a way.

DB: Absolutely. And I think when Isaac Stern, the great violinist, stood and played every night a Chopin piece, or a Beethoven piece, it was brand new every day. I think what distinguishes one artist from another is the ability to really transform the air, and to magnify reality into the surreal.

AZ: Yeah.

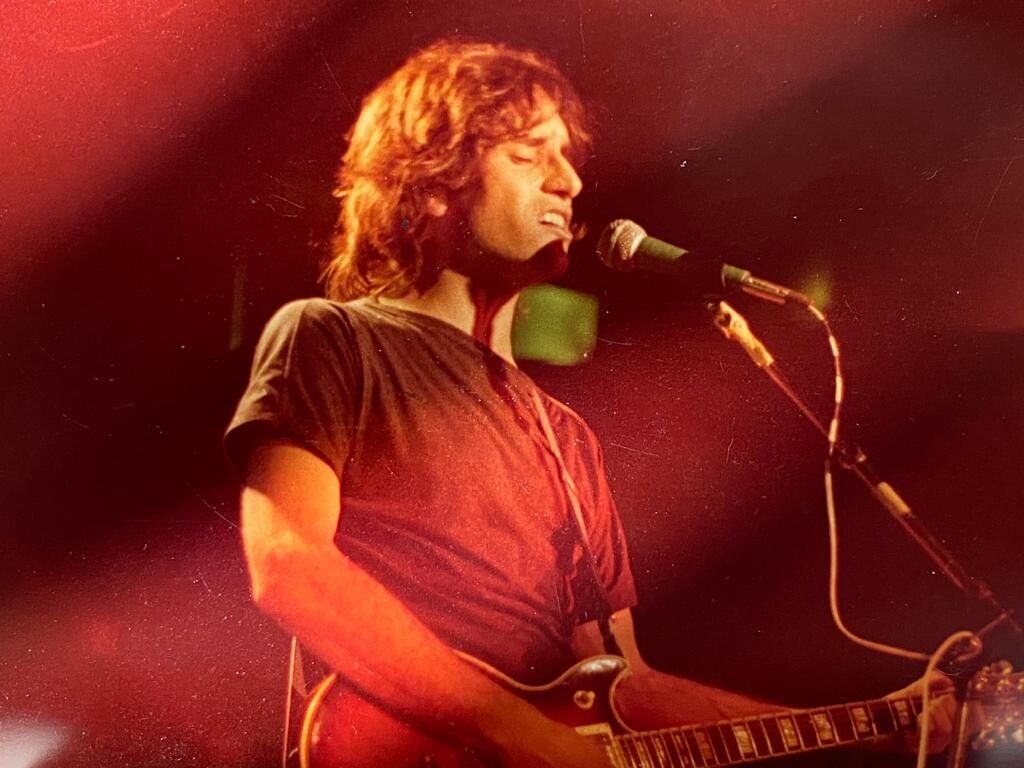

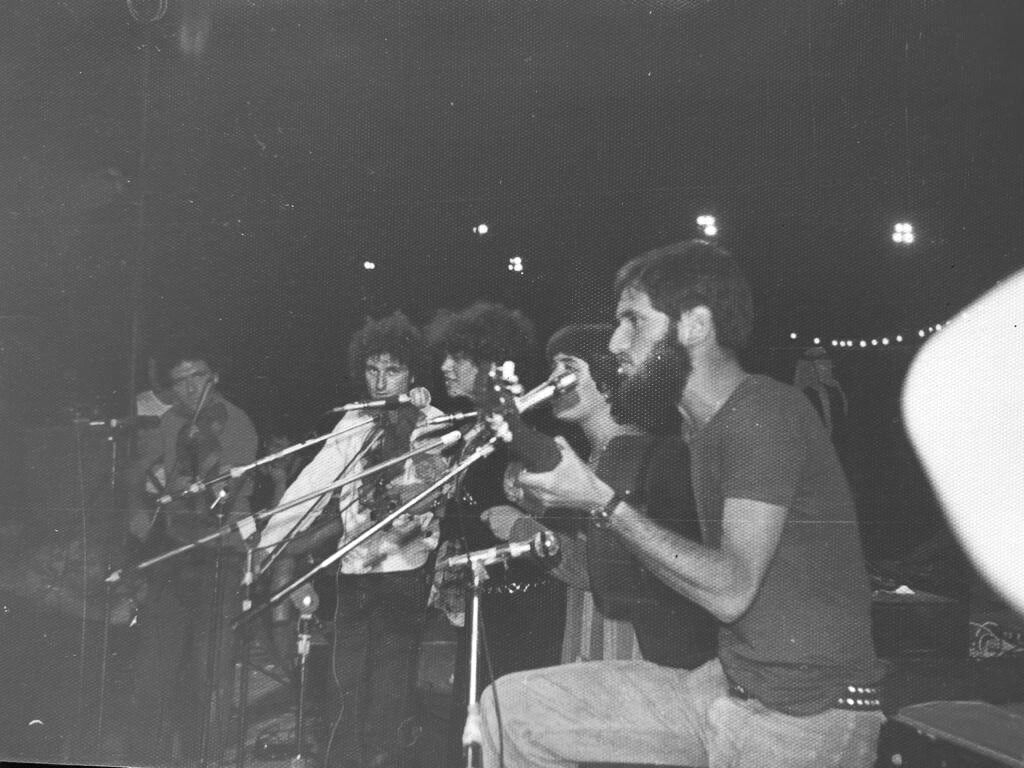

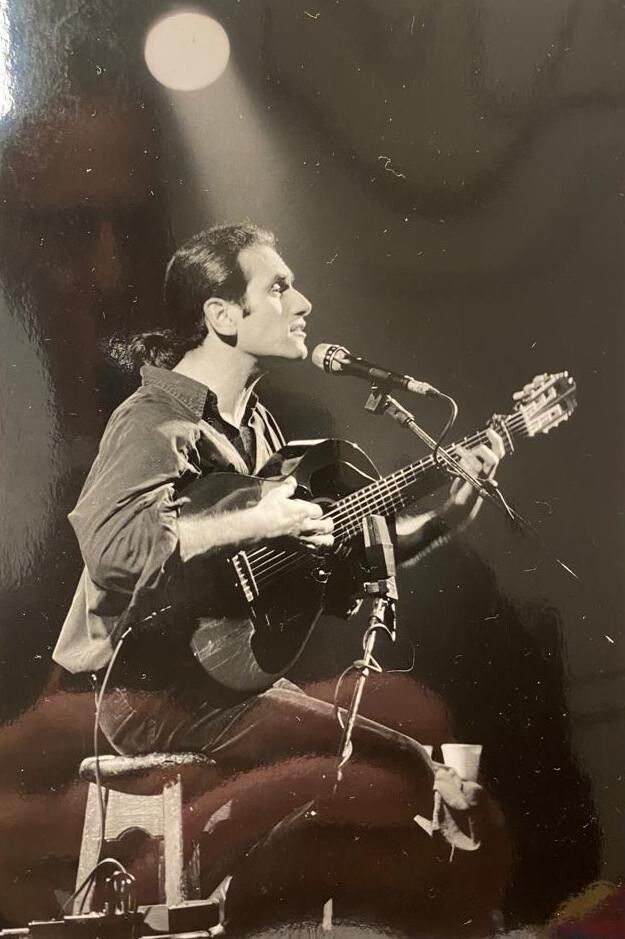

Broza performing his album KLAF at a concert in Israel in 1982. (Courtesy David Broza)

DB: Every show that one does is surreal. There is nothing real in a show, because when you walk out of a show, all you take with you is the impression. The impression is in your heart, in your soul, and in your mind. Go tell somebody what it was like to have an orgasm. You can never explain it.

AZ: You don’t remember the specifics. It’s like, we speak to a lot of chefs on the show. And we talk about how it’s a great meal when someone can’t remember what they ate the whole time.

DB: [Laughs]

AZ: They just leave with a feeling, a kind of impression. That is very much what it seems the show is like. But your life really changed at that moment. Your early twenties, and you’re a superstar.

“I love being successful, but the measure of success that I agree to is the one that I decide. It is the one that actually really helps me feel accomplished.”

DB: Yeah. I mean, being a superstar doesn’t relate to me. Excuse me for…. I’m not denying it. But frankly, this is not what I am here to do. It’s something, ah….

AZ: Did you resist it when it started?

DB: Maybe after that. I don’t refuse. I embrace it. I love being successful, but the measure of success that I agree to is the one that I decide. It is the one that actually really helps me feel accomplished. In the art, because I switched from visual art, from painting, to music—and I know that many artists that are successful started at a very young age, even Bob Dylan. They started listening, fantasizing to radio and all that. Everybody that I know, almost everybody. Until 22, I didn’t even think the guitar would be my instrument through which I would make a living and I would express myself for life. It was always with me, but I was covering Dylan, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Arik Einstein, Shalom Hanoch, Serrat. I was covering music I liked. Not great, but I did good. Obviously it was in me somewhere, but I didn’t dedicate my life to it.

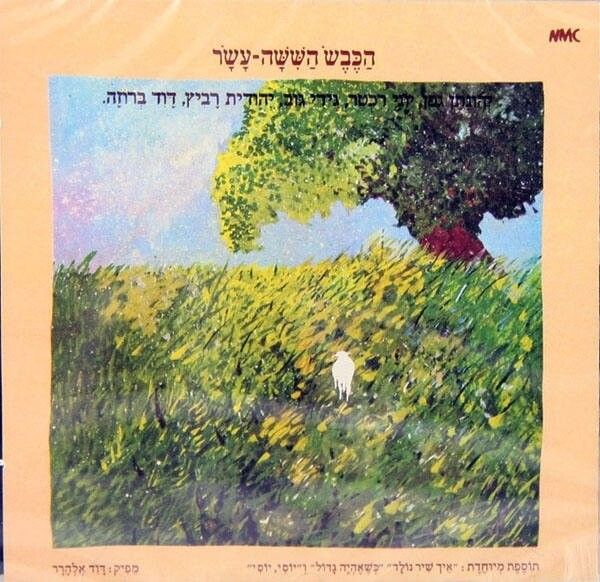

Cover of Broza’s album The Sixteenth Lamb (1978).

The idea of being so big, as I became—but not with the first song. With the first song I became very popular, but as a singer-songwriter and with Yehonatan Geffen. Then I did a children’s album with Yehonatan Geffen called “The Sixteenth Sheep,” “Ha-Keves Ha-Shisha-Asar,” that still today is the most popular, and partly best children’s album ever, in Israel. And I would say one of the best. If one were to take all the best children’s albums from Raffi to whatever you want—American, British, French, German, whatever—this would be in the top hundred ever produced. So I was very lucky to be on that incredible path.

And then I do my third album [Ha’Isha She’iti], which was an ode and a homage to Spanish popular music, by choosing songs of artists that I loved. I mentioned Serrat, Paco Ibáñez, Manzanita [José Manuel Ortega Heredia], Cecilia [Evangelina Sobredo Galanes], all these. And translating them into Hebrew with my good friend Yehonatan Geffen, who doesn’t speak a word of Spanish. We did an amazing job together. He’s such a brilliant poet. So I would translate things to him. It all started with him being frustrated that I’m singing songs to myself—covers—and he doesn’t understand a word. English okay, but Spanish—

AZ: Someone that deals in words.

DB: Exactly. He was so frustrated. I’m flustered because I’m singing. My cheeks are getting red. I’m sweating. It’s all before a show, because I’m warming up, and he wants to know, “Hey, can you share this with me? What is going on in that story?” Then I would start translating. I’m not a great Spanish speaker at the time. So with every translation, I have to check: What does the word mean? How it resonates for real, not just the poetry of it. We go into these lengthy discussions, and then he makes notes, and then he comes back an hour later or two hours later and-—

AZ: Finds the essence.

DB: Sings. And it’s one-on-one. It’s—

AZ: Oh, wow.

DB: Not adaptation. It’s really—

AZ: It’s a close one.

DB: It’s the closest to describing making love in different languages. It’s unreal. So yes, it changes my life. But it takes me, if you want me to be honest—after all these years, forty-five years as a professional musician—over thirty years to accomplish the moment where I can say I’m a master of my art, and a master of my craft. Whereas if I had started at six—because as an artist, I was already established. By the age of fifteen, I was selling paintings—

AZ: Paintings in the market.

DB: In the market, and in galleries. I was destined. I saw myself as…even if it’s a graphic artist, and then a painter on the side, or painter and a graphic artist, whatever.

Broza (right) and Yehonatan Geffen (left) performing together. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: What is it that creates such a bond between you and Yehonatan Geffen? In your life and your work, what is it that you share? Are you similar? Are you very different? How do you—

DB: So different. We’re literally black and white. I’ll give you that. That’s very easy. So I was born in Israel. My mother was born in Palestine. My grandmother, too. So just—

AZ: I’m going to get into your whole family. I have a lot of questions about that.

DB: So my—

AZ: Fascinating lineage.

DB: My roots are in Israel, Palestine, Middle East—deep. But I grew up in my teenage years, in Spain. I become a cosmopolitical Israeli. I see the world. I understand Israel from afar. I go through all kinds of breakdowns and I become who I am. At the age of 18, 19, I come to do the army.

Yehonatan Geffen comes from a family of farmers, from the heart of Israel, from a very famous farming village called Nahalal. He is the nephew—he’s the son of the sister, therefore the nephew—of Moshe Dayan. The Dayan family are like this dynasty in Israel. So he’s very rooted, and I’m very uplifted, uprooted. I’m the cosmopolitical, and he’s the provincial. First of all, that.

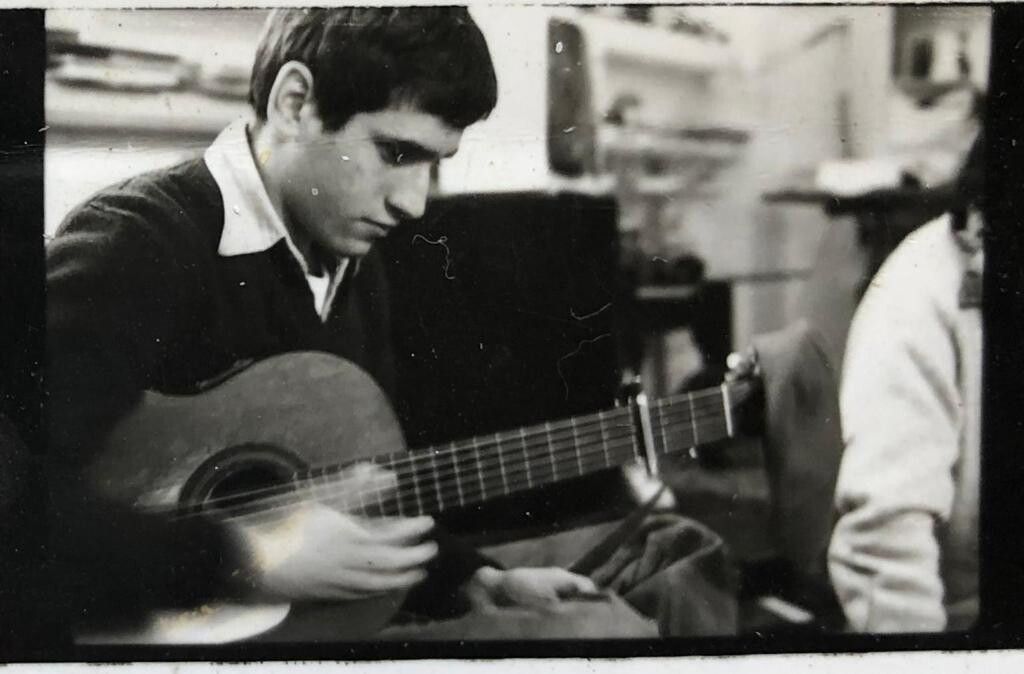

Broza in Spain at age 14. (Courtesy David Broza)

What happens when I leave Israel at the age of eleven for Spain, I’m torn. I’m really torn. I’m so comfortable in my skin in Israel. I’m so out of the water in Spain. No language. I am put in an English school; I don’t speak English. I’m on the streets in Spanish; I don’t speak Spanish. Yet the faces of the people on the streets are so similar to Israeli faces. That mix of the Arab blood, the Moorish blood, and the Nordic blood—and not Nordic, but most North European, all that mix, that became the Iberian persona. Everything looks familiar, because Israel is such a mixed crowd. And I actually, I refused—at the age of eleven, when we arrived in Spain—I refused to speak Hebrew to my parents, which was a terrible shock to them. Something in me just kicks. It says, Never…. You took me out of my comfort zone. I’ll show you what—stupid things.

So when I come back to Israel, I come to the army, and my Hebrew is really poor. I read all these years. I read Hebrew, avidly. I’m good at expressing in writing, but I can’t—the words don’t come out right, and I feel very embarrassed by it.

AZ: Languages sound very different. Spanish included.

DB: Hebrew and Spanish could sound with a ch and resh and ereh.… But yeah, languages. It’s a mentality, too. So now I’m a master of that. But back then, and when I met Yehonatan, suddenly I’m thrown into this—“Take the place of Churchill,” the musician, who is the side guy on Yehonatan Geffen’s show. I’m sitting next to the guy who is so rooted in Hebrew, and he’s a poet, and I love poetry. I love poetry. Always did.

When I was a kid, I would read Spanish poetry, Hebrew poetry. And when he gives me the first song, “Yihye Tov,” I find I’m actually singing the best Hebrew that I love. And then he gives me another song, “Señorita,” and then he gives me another song. And then he shows me a song of Nathan Alterman, another Israeli, grand poet, which I write to music. And then I do another one, and another. And through him, the Hebrew becomes not only comfortable, I regain my identity, which I’d lost when I left for Spain. I’m back to being that kid, and I own my identity. It’s so important. It’s so vital for me as a person. And I think it’s somewhere in every person that is born into this world—identity is so important. This is what wars are all about, but I’m in a cultural identity.

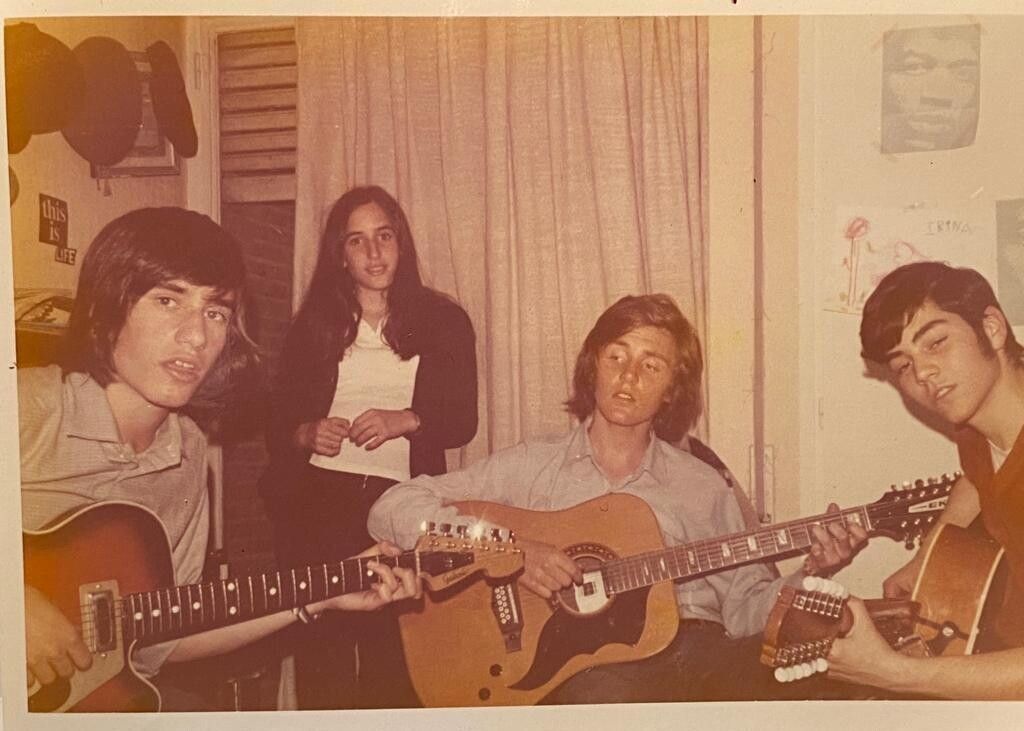

Broza (far left) at age 15 with his sister, Talia, and two friends in Spain. (Courtesy David Broza)

Just before I came, I wrote Yehonatan Geffen: “Hey, have a great weekend. I hope you’re feeling good.” He’s nine years older than me. He’s post-trauma from the Six-Days War and Yom Kippur War. Heavy post-trauma. I mean heavy, heavy, heavy. Never treated. He should have been, but he’s one of those heavily damaged who are so proud, that they would never allow themselves to admit that they can’t function. With all this functionality, he’s one of the greatest poets, one of the greatest writers, one of the most provocateurs by nature. How would I not? I’m not all of those.

AZ: Yeah. There seems to be that, together, you have this sort of duality of pain and beauty.

DB: Absolutely.

AZ: What I was thinking about, actually, was the simultaneity of emotions when you work together, and this idea that’s very much an Israeli thing, that I think people don’t totally understand. The pain and the beauty, the softness and the sharpness. And what is it about life in Israel that everything contains both, much like your music does, much like the collaboration you had with them?

Broza at age 21, performing with a folk band at a concert in Israel. (Courtesy David Broza)

DB: Wow. Such a good question for analysis. First of all, Israel is a land of immigrants, very similar to New York, or to America. So there are similarities, and I think, on those similarities, maybe people can identify, if your listeners are American. But even if not, imagine, all immigrants—some of them are refugees, and some of them are by-choice immigrants. They’re all uprooted.

When they arrive in a place, they have to build roots. They have to make roots. And that makes them dependent. Until they have those roots, they are dependent on one another. They’re not alone. They would stick together. Like in America, you have the Greek—used to have—the Greek neighborhoods, the Irish neighborhoods, the Italian, and the Jewish, and the Russian. And now, you still have some of that. In Queens, you’ve got the Korean, this and that, from all over the place. Until they have roots, they will stick together to one another where they can speak the language. Like in Israel, it’d be the Moroccans, the Yemenites. The Algerians who don’t talk to the Moroccans, the Libyans who don’t talk to Egyptians, the Polish who don’t talk to the French, the French don’t talk to the Germans. The British hate everybody. Woah.

What was it, Tom Lehrer? Who was it? He used to have a “National Brotherhood [Week]” song: [sings] “Well, the British hate the French, the French hate the Germans, but everybody hates the Jews. And this is national….” [Laughter] In Israel, it’s very much like that. It’s the land of immigrants, for the most part. And then there’s of course the Arab local population, which comprises about twenty percent of the population, and is more and more now becoming integrated.

Broza playing the guitar in his childhood home in Tel Aviv. (Photo: Ziv Koren. Courtesy David Broza)

But let’s talk about my Israel. When I was a kid, there was no integration. So I think in the character of the Israeli is depending on one another, very much so. And there’s also differences. But then where would you find a German who marries a Yemenite, or an Argentinian who marries a Moroccan? It doesn’t happen. It doesn’t happen. Two different cultures, different food, different approach to love, to respect, to religion. Wow. So different.

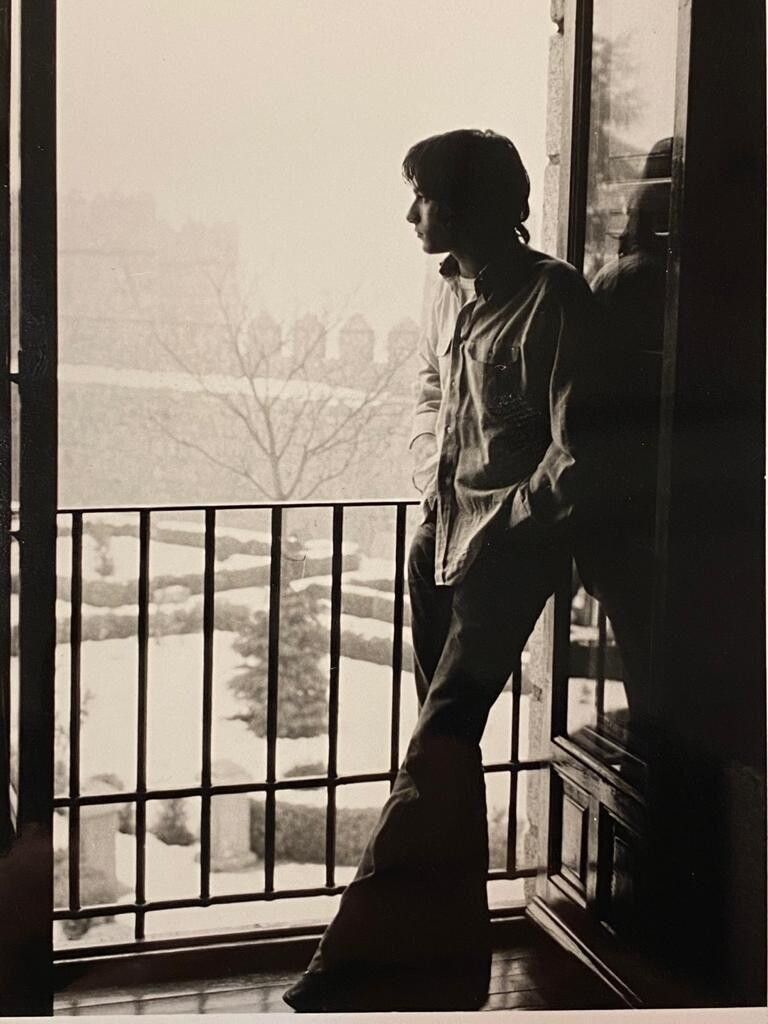

Broza at age 19 upon returning to Israel. (Courtesy David Broza)

In Israel, it’s all over the place. It’s what it is. So we bond. Then, whether you went into some kind of a movement as a child—the Scouts, or socialist movements in Israel, or not, if you didn’t go—then at 18, you’re drafted to the army, whether you like it or not. And you’re sleeping on a bunk, and the guy next to you is, again, one is a Russian and one is a Moroccan. And you know what? You’re sharing the same misery together. So you become best friends. One is a rich man, one is a poor man, sharing the best. Listen, this is the beautiful thing about the army. Forget the wars.

AZ: Eating the same food.

DB: Eating the same food, being clobbered by the sergeant. Oh, man. It’s amazing. It has an amazing effect on creating a unified society. There’s a bonding, and there’s a trust, that can never happen [elsewhere]. And here, the only place you could try it is on college campuses. But colleges also, there’s the colleges for the rich, for the poor. There’s the Ivy League, and there’s the regular.

AZ: There’s no equalizer in this country.

DB: Except in the army.

AZ: Except in the army, of course.

DB: Except in the army. I remember when Ross Perot was running for president, his story, you know. And you suddenly understood that all the people that he turned to trusted him because he was one of them, because they were all military people. To everybody, that’s the American spirit. But it isn’t, because not everybody goes to the army. There’s no bonding place. There’s no place where everybody is stripped of their class and their identity and they become one. In Israel, there is. You’re all stripped. Everybody’s, “Thirty seconds on the double! Move it!” “What? Huh? What?” “No, move it!” Otherwise you’re going to do fifty push ups now. Run around that block a hundred times. You’re going to be in jail now for twenty hours, or whatever. Everybody is in this together.

AZ: Yeah.

DB: And no matter whether you’re going to be a combat guy—which is, let’s say, the toughest—or you become a little sad sack private like me, you still have to go through the basic training. You still have to be exposed to everybody. It’s fantastic. On that level, that is what makes Israel very, very different.

AZ: I want to jump to now and your most recent stuff, a little bit of a pivot. You recently reinterpreted the Friday night service for Temple Emanu-El with an [album] called Tefila, which is essentially a liturgical body of music. How’d this come to be, and how did you ultimately approach it? And then what I want to get to is if things shifted for you in your relationship to the religion, and not just the culture through it. So let’s start with just how it started.

Broza at his first performance of Tefilah at Temple Emanu-El on May 6, 2022. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza at his first performance of Tefilah at Temple Emanu-El on May 6, 2022. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza at his first performance of Tefilah at Temple Emanu-El on May 6, 2022. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza rehearsing Tefilah with his musicians. (Courtesy David Broza)

DB: Well let’s say, I’m still figuring it out. I’m still learning it. First, imagine being who I am, dedicated to writing music and by the way, my entire career: By decision, I decided I’m not going to be the sole one who writes lyrics of the songs I compose. I will work with poets. So I’ve always collaborated—whether it’s the Israeli poets, Yehonatan Geffen, the great Meir Ariel, who passed away, Nathan Alterman, who’s dead, or Lorca, Machado….

AZ: You used to sit in Gotham Book Mart reading poetry.

DB: Yeah. Wow.

AZ: I mean, this is a lot of commitment to that.

DB: And I taught creative writing.

AZ: Yeah.

Broza in Spain at age 17. (Courtesy David Broza)

DB: I came from rock and roll, and from jazz. I was far, far removed from any liturgical works, but I was not unaware of it. I come from a house where my father grew up in a more observing and observant family. Not very religious, but I think they were observant to the degree that they probably didn’t drive on Shabbat, on the sabbath. He was not observant, but he liked to keep Friday nights and he liked to keep the High Holy Days. And he made sure that we have something of that in the house, in a very patriarchal way, like, “David, don’t even think of going out on Friday. We’re having dinner together. After dinner, you can do whatever you want.” And it limited me a lot, because my friends were all secular, completely secular, and I am, too.

Then I was sent at the age of 16 from Spain, where, due to music and my character, I guess, being a renegade at heart, but evocative…well, not a provocative one. Maybe I was provocative then. I was asked by the principal of the school not to come back. My parents were asked, “Find another school for David. He’s 16.” So they sent me to a boarding school in England, which was Orthodox. My parents are living in Spain and I’m from Israel. So this is starting to look bad, and it gets worse as I’m in school. And at the end of that year, I’m asked not to come back to that school.

But during that year, even though I’m very much…. I don’t want to join the prayers three times a day and all that. But the rabbi, Rabbi Rosen, one morning catches me, and he sees that my mind is not with a prayer. And he says, “Okay. You’re constantly [doing] something. You’re playing music.” He knows that I’m playing guitar all the time. That’s another issue, because I play on the Sabbath as well. I never stop playing.

He says, “Let me teach you something. If you’re already here, contemplate. Contemplate about your life, contemplate about the day that you’re going to have.” Because we’re praying in the morning, the early morning, Shacharit. And I think that’s one of the most important lessons I got, because I learned how to contemplate, which kept me out of trouble in so many places, and out of depression, especially in the army. I come to be a combat, you know this, and my profile goes because of asthma to one that there’s nothing you can do with me. And I have to go through these—and how do I learn how to? I don’t know, but I’ve got it instilled in me, that contemplation.

Broza (far left) and his basketball team at Carmel College in the U.K. (Courtesy David Broza)

So, cut to the chase. Forty-five, fifty years later, I get a call, literally on the first month of Covid. It’s April 2020, and I get a call from the program director at [one of] the largest synagogues in New York City, Temple Emanu-El. It’s reform. I know the building. I’ve actually rented out one of their rooms, which seats eleven hundred, to do my annual “Not Exactly Christmas” show, which I do on the Christmas Eve for twenty-five or twenty-six years. And I ran out of places. I used to do The Town Hall, then I did the 92nd Street Y, now I did a couple of times at the Temple Emanu-El auditorium.

And he’s telling me that they’ve talked about it, and on behalf of the temple, of the synagogue, he would like to ask me to consider writing music—new music—to Friday night prayers, what’s called Kabbalat Shabbat, receiving of the Sabbath. Which actually is the funnest, nicest, happiest prayer in the week that I know about. Don’t know much. I don’t remember from the years I was in boarding school, the year I was in boarding school. So I tell him, “Listen, I don’t think I deserve this. I don’t think I’m the guy for it. You got to get somebody who understands prayer, who practices.” He says, “No, it’s exactly what we don’t want. We want a completely new, objective outlook.” I say, “Okay listen, if this is what you wish, I will consider, but I’m not accepting right now. Just send it to me. Let’s see what it’s about.”

And he sends it to me, but we’re getting into quarantine. The quarantine goes on for several months. I read every book that was on my bucket list. Normally I do two hundred shows a year. So I’m traveling nonstop. I do twenty flights a month. I take books for the flights, but I fall asleep before take off. I wake up, and I’m lucky, that’s how I spend my years and my life traveling—most of the time, asleep, for the hours that I will not sleep later.

So I finished my bucket list four months into Covid, and I remember that email. I look for it. I open it up and I see the fourteen prayers that this liturgic piece wants to be made of. I look at it, I read it, I study it, and I study it as poetry. I don’t look at it as a liturgical piece at all. I take away all the importance of liturgy, all the importance of prayer, all the melodies that I know as a child passed on by my father, passed on by his father, passed on by generations. And I just look at it completely objectively. I pull the guitar after I contemplate this, and the first melody comes out. And it’s really cool. I mean, look, I’m thinking liturgical—who would think that a liturgical piece would be: [plays guitar and sings in Hebrew] “Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech haolam/Asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’hadlik ner shel Shabbat.” [Editor’s note: The English translation is “Blessed are you Adonai our God Sovereign of all/Who hallows us with mitzvot commanding us to kindle the light of Shabbat.”]

Very bluesy. Wow, this will be a blues thing. And I’m thinking that, and I’m singing this for an hour or so, just making sure that I’m tightening it, and being sure that this is the melody I want. Then my wife sticks her head in the room and says, “What was that?” She hears it from the other room. She’s working on her stuff in the living room. I say, “I’m looking at the prayers.” She says, “Wow.” And it really excites me, like my heart jumps. I closed the email, put the guitar down, I recorded it on the phone, and I sleep on it. Next day, I wake up, go through my routine. Ten o’clock or eleven, I sat in my study. I open up the email. I go to the second one, second prayer. Same thing. I translate it. I mean, I contemplate, I look at it, I read, I study the rhythms.

AZ: It comes out.

DB: Another one. So for the next fourteen days, I’m writing all these pieces. I’m not calling the guy at the temple. I don’t want to commit to nothing. I want to know that I can deliver before I take it on.

AZ: Yeah.

DB: After fourteen days, I sent him all the songs I recorded on my phone. And I’m saying, “If this is what you’re interested in, this is it. I got it. I can do it.” He’s emotional. He’s literally emotional. He’s got no words. He can’t speak. He’s like, “Wow.” And I’m thinking, Okay. I mean, I love the music and the Hebrew. I’m mesmerized by the Hebrew. I’m like, Woah. I’m blown away. I don’t need nothing. I don’t need nothing. Just let me have that language. [Singing] “To see you, le ratzon.” [Editor’s note: In Hebrew, le ratzon translates to desire.]

It becomes flamenco, it becomes Latin, it becomes klezmer. I play everything that I know, all the music I’ve ever collected, and basically taken in all these years by all my travels. In the meantime, it’s forty-five years. I spent the years in Israel becoming successful. I spent the years in the United States learning the American way, recording six albums dedicated to American poetry. Then I moved to Spain. I do three albums in Spanish with the best Spanish writers. I perfect my Spanish. Suddenly, finally, I talk Spanish like a Spaniard. I really speak the language. I read the language. I perform in the language. Talk about how long it took me to become the master of my art and my craft. This is it. It’s what I really wanted to be when I decided to become a musician.

Argentinian folk singer Mercedes Sosa. (Photo: Annemarie Heinrich)

Now, with the liturgical, and I’m thinking, So what? He’s excited. We discuss budgets. I tell him, “This is my vision. And this is what I need to be able to do this.” And it’s a big production. And this brings me to some piece of music which I was exposed to when I was about 15, called Misa Criolla. In English, you would say “Misa Criolla.” The one that Mercedes Sosa [did], the great voice of South America…. Mercedes Sosa was the best folk singer of all time in South America. She was Argentinian. We were very close friends. I was lucky to meet her. She was like the Otis Redding of soul. I was very lucky that I got to know her. But I listened, from the age of fifteen, on Saturday morning, on the Sabbath, I would put her, then I would put John Coltrane, maybe [Jimi] Hendrix, maybe The Band. That was my playlist, as albums, as a kid, records. But that Misa Criolla was with me, I don’t know, for about the next twenty, twenty-five years.

So when I got those fourteen prayers and when I put the music, I wanted to create my Misa Criolla, which is the prayer. Tefila in Hebrew is “the prayer.” So I called it Tefila, and I left it as such. It’s my Tefila, my Misa. And the way they did it—so it’s Ariel Ramírez, he’s South American. He wrote Misa Criolla. It’s got choirs, it’s got ethnic instruments. So I mixed other things. I took a classical choir, gospel choir, jazz musicians, rock musicians, strings, horns, and mixed all this into a wonderful, amazing production, which now, I committed…. Originally, I committed to do two live performances of it, and now we’ve extended it to ten. So I’ll be with it until next June, the first Friday of every month, except for July, August, September. But now I’m saying, I’m still discovering and understanding it, because now I’m doing it live. And when you do it live is when you really become acquainted with the power of beautiful poetry that is liturgic.

AZ: It’s so interesting because they say, or the most resonant ideas that I’ve heard about these services, is that it’s about a personal relationship. It’s your moment to have a personal relationship with God. And you seem to have found the most personal way into your own narrative, and this idea of the world around you through this project. Do you think of Judaism differently now than you ever did?

DB: No, no. It’s the same Judaism that I practice when I sing Lorca, Alterman. Elizabeth Bishop, Walt Whitman, Matthew Graham, Liam Rector, Bob Dylan, anything. It’s all in there.

AZ: It’s about the collective.

DB: It’s beyond the collective. It’s about my connectivity, and my total commitment to the poem that I’m about to interpret with the help of my music. When Liam Rector writes a poem, and it doesn’t sound any less…. [Playing guitar and singing] “With the window sitting with you,/and the glass with air to see it/there I came with you to be with/there and if….” Just the words. [Singing] “And the snow was wet and moving/Soon we brought the afternoon in/Soon with gin we poured the eight down/Soon we felt the air we moved with.” I don’t know. When I sing these words, I literally go into tunnel vision. I’m in that space—this is what I mentioned when we just started the conversation—is that performance is surreal. Because it goes—

AZ: Time is different.

“[Performing] goes under your consciousness. It’s subconscious. It’s deeper than anything. It’s the closest thing to the flame, to the essence of being for me.”

DB: Yeah. It goes under your consciousness. It’s subconscious. It’s deeper than anything. It’s the closest thing to the flame, to the essence of being for me. I know it was that for Otis Redding, for a lot of people, a lot of very successful…Janice Joplin, Amy Winehouse, everybody. Everybody who’s successful in interpreting is surreal.

AZ: And time really is different for you in that space.

DB: Time stands. Time stands. There’s no time. There’s no time. There’s nothing. Not even Einstein—nobody knows how big space is there. I’m telling you, this is for real. This is what has enabled me to perform my music for all these years. Sometimes twice or three times a day. Every time, it’s the first time I’ve ever done it. And you’re entering a realm, you’re entering a dimension that is not a formula. It’s a martial art. It’s brilliant. It’s so precious. And I own it, so I can use it anywhere I want, whenever I want. Which is why people know—especially in Israel, they know, some in Spain—that they’ll find me in a restaurant after a good meal, pulling out my guitar, and singing a bunch of songs for my own good.

A Zoom concert Broza held in June 2020. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: Well, you famously sang in the bomb shelters and—

DB: Oh, yeah.

AZ: All night. I mean, this is—

DB: Yeah, I own it.

AZ: You live and breathe it. When I was thinking about you and the life you’ve lived in prepping for today, I was thinking about what it must’ve been like to just stop all of it in Covid.

DB: I didn’t.

AZ: Well, in terms of the ability to connect with people. You did it for yourself, obviously, all day long.

DB: No, I did over one hundred and fifty shows from my couch.

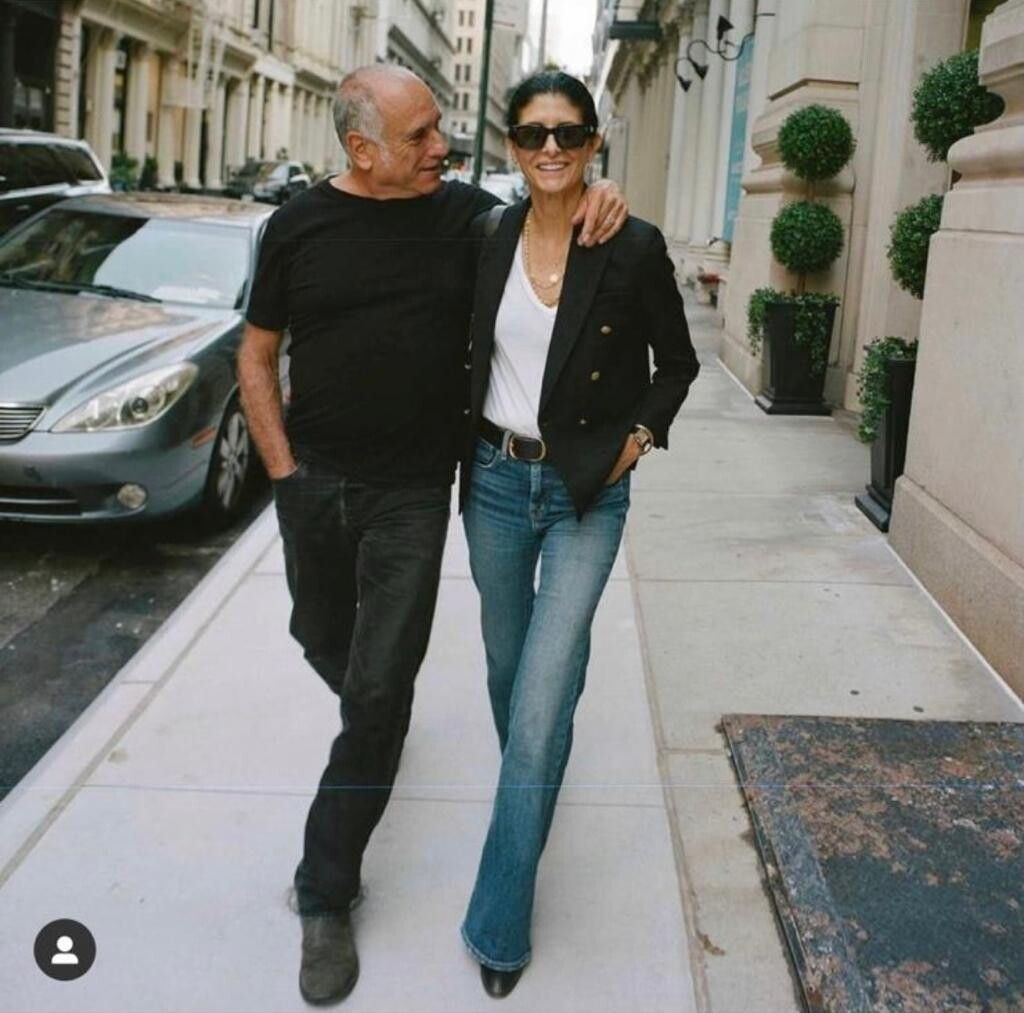

Broza with his wife, the fashion designer Nili Lotan. (Courtesy David Broza)

DB: The best part of it was actually being locked with my wife, Nili [Lotan], and locked with my guitar, and discovering things I had never done before. And ultimately, doing this Tefila, this great liturgical piece, which I would’ve never been in such a peaceful, open space.

AZ: I want to switch back to your childhood a little bit, which we’ve touched on, but you have such an incredible history in your family, generations back. I just want to start: Your mother was in Israel, pre-’48?

DB: My mother was born in Tel Aviv, in 1927. Yeah.

AZ: Born in Tel Aviv. Wow. And she was a folk singer?

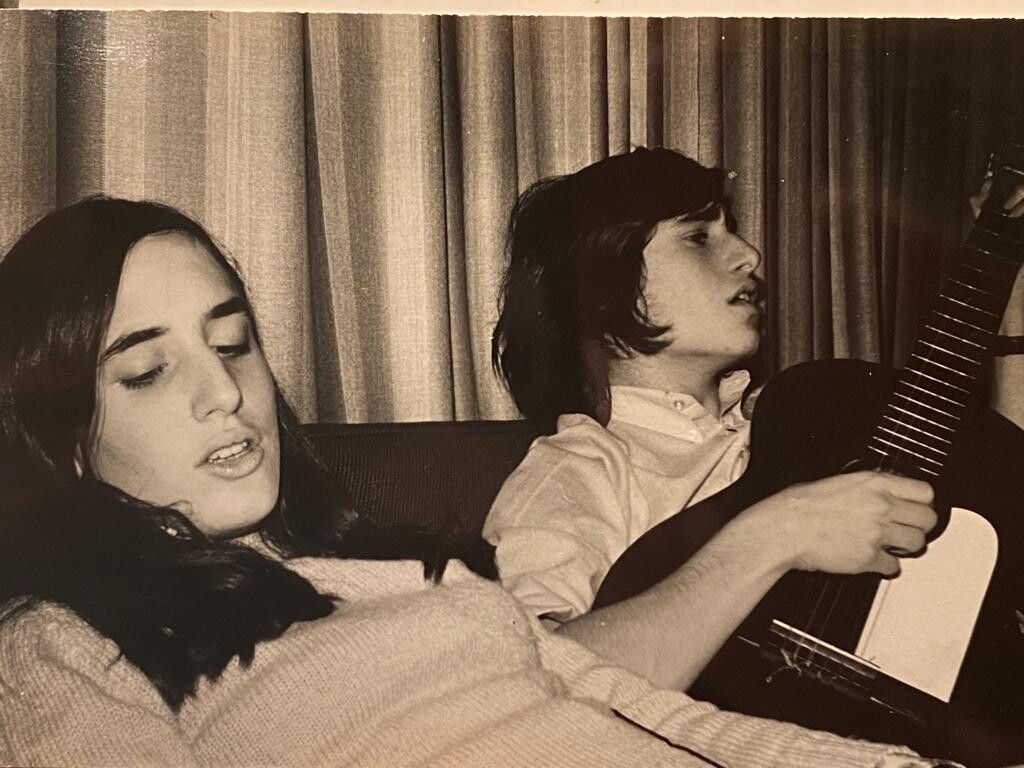

DB: She was one of Israel’s first folk singers with guitar. Her name was Sharona Aron. It all started here in New York City. She came here at the age of 18, or maybe later, right after the army. She did the army. She was Israel’s first announcer in the Israeli IDF Radio, which is the number one radio. She was the first one, in 1948. So she came probably after she completed the army. And at Columbia University, they had an international house. I think once a week they would get together, and everybody would play a song from their country. She knew maybe two or three chords in guitar, so she played.

Broza’s mother, the folk singer Sharona Aron. (Courtesy David Broza)

And she started playing around, and people liked what she sang in Hebrew. And she says that once, on the way back to Israel, she stopped in London, and she was talking to a friend in a café, and a gentleman heard her voice, and asked her if he could speak to her for a minute, and said he loves her voice. “Do you sing?” She says, “Well, I sing one song, two songs.” He says, “Would you come with us?” And he took her to Abbey Road Studios, put her in front of a mic, and signed her to HMV, onto Victor Records, and then Columbia Records. And she recorded the first Israeli folk songs as-

AZ: Wow.

DB: As Sharona Aron. She knew nothing about…. She didn’t even know this was coming her way. And she was amazing at it. Amazing. Some of the most important songs, of the basic folk songs of Israel, were hers.

And over the years, when artists would come to Israel, like Pete Seeger, Harry Belafonte, The Platters, Odetta [Holmes], they would want to meet their colleagues from Israel, and people would say, “Oh, go meet Sharona Aron.” So they all came to the house. They all sat on this couch in the living room, and I was five, and six, and seven, grew up with these faces.

Last time I met Pete Seeger, he was 95, It was before he passed away. We did a show and Peter Yarrow, from Peter, Paul and Mary, said, “You got to come with me. We’re performing with Pete Seeger. Get on stage.” I said, “What am I going to do?” He goes, “Don’t worry. He’ll sing.” So I met Pete Seeger and Peter Yarrow says, “He’s Sharona Aron’s son.” Now, this is a few years ago.

Broza’s mother playing the guitar. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: This is how you were reintroduced?

DB: Fifty years have gone by. He remembers, and he sings me my mother’s song, in Hebrew. He sings it to me on the shoulder, without a guitar. And then he says, “Since you’re Sharona’s son, I want to teach you a song. You got to sing this.” As if he’s leaving me with some legacy. And he sings this long song. There’s a long line of people waiting to talk to him. And he’s just taking his time, beating on my shoulder. At the end of which he says, “Learn that song.” “What song is it though? Where do I find it?” “You’ll find it.” I don’t even remember it, anyways. Like a minute later, I was so in awe. So that was my mother’s present to me.

AZ: And that’s where you found guitar, her guitar?

DB: Her guitar I found actually in Madrid, and I just wanted to play, and I taught myself how to play, basically. She allowed me to use it.

AZ: And she was obviously supportive of all this?

DB: She didn’t know what she was supporting. She was just supportive of me playing guitar, because I would listen to all this great music, The Doors, Hendrix. And I started playing on her guitar. Then I started the garage band, so I needed an electric guitar. So my dad rented one, rented a guitar, electric guitar and an amplifier for me to have. That’s how we started.

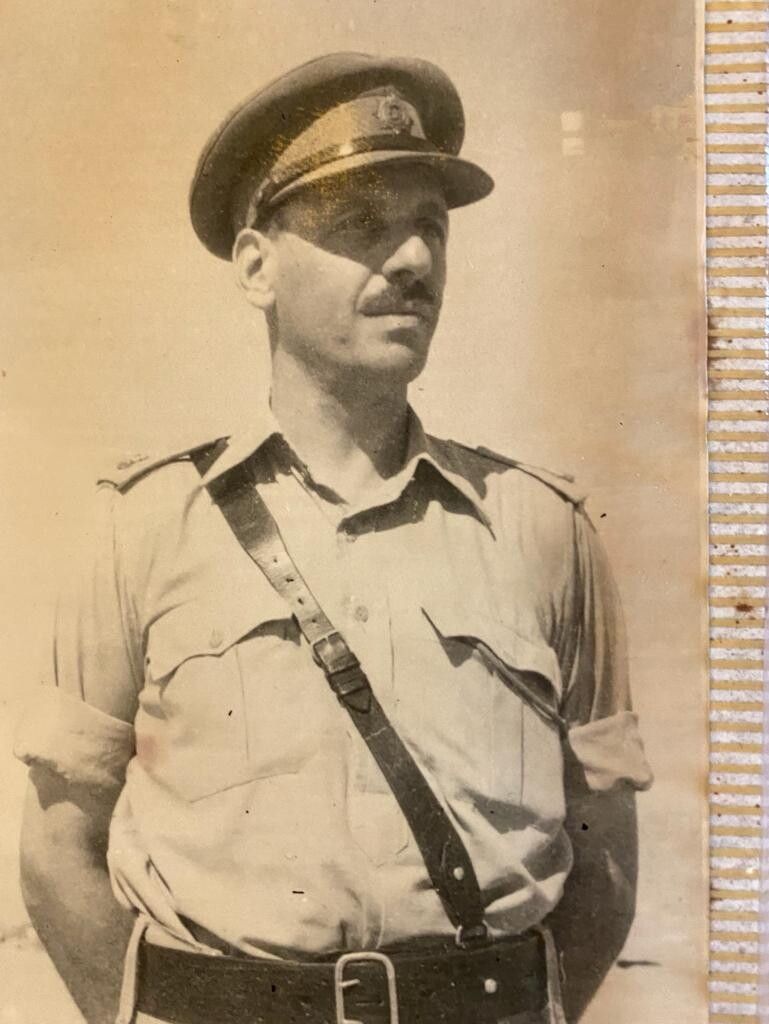

Broza’s grandfather, Wellesley Aron. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: But this whole desire to unify is really, I mean, your mother, but it also goes back to your grandfather, Wellesley Aron, who founded the Jewish youth movement, Habonim. And also helped establish Neve Shalom, Oasis of Peace, which really was right around the same time. It was ’78. So around the same time you wrote “Yihye Tov.”

DB: Correct.

AZ: Were you connected to him at the time? Was this part of the whole….? I mean, when you tell the story, we think of you as this kid, and 22, 23, alone, and traveling, but you also were connected to these generations of this.

DB: For sure.

AZ: Did people know that about you? Were they aware of who your grandfather was?

DB: They still don’t. They still don’t. They think of me as this cosmopolitical guy. Yesterday, we had a dinner, and we met with some people I’d never met before. And I told them that I was born in Israel. My mother was born under the British Mandate in Palestine. And my grandmother was born under the Ottoman Empire, the Turkish empire, in Palestine. They arrived in 1880, in Palestine. So I’m the only Israeli; they’re all Palestinian. Everybody looked at me and said, “What do you mean you were born in Israel?” I said, “Yeah, I was born in Israel.” “Oh. We thought you’re from Spain or South America.” Which, everybody thinks that’s where I’m from.

Broza’s grandfather while serving in World War II. (Courtesy David Broza)

So nobody knows of this incredible family, which to me—because our family is not a dynasty. The Dayans are a dynasty, because that was their business to become…. Moshe Dayan, they had big names. They made a lot of noise. My grandfather was this political secretary to Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first president. He was born in England and actually came from a very strange background, because his family, his siblings were from another mother, the first wife of his father, who was Christian. They were raised as Christians. There was five of them. When she died, he was about 60, and he didn’t feel strong enough to raise these kids alone.

So he went back to where he originally came from, in the German territories of Weimar, and he brought the rabbi’s daughter, and had one son. That son was named Wellesley, which was after the Duke of Wellington. Again, very waspy, very Protestant name. And his brothers, his siblings, raised him. So he wasn’t ever attached to Judaism, until when he went into Jesus College. He was accepted to Jesus College because he was a great athlete, and his older brother got killed in World War I, and he’d been to Jesus College in Cambridge. He was Christian. In his honor, they accepted his younger brother, who was already Jewish, but they didn’t know it, and let him be in Jesus College. And he became the captain of the first [eight] rowing team, and it was a high jump. He became an [athlete] along with Olympian Harold Abrahams, who they did the film about, Chariots of Fire. That was when he discovered that he was Jewish. That became—

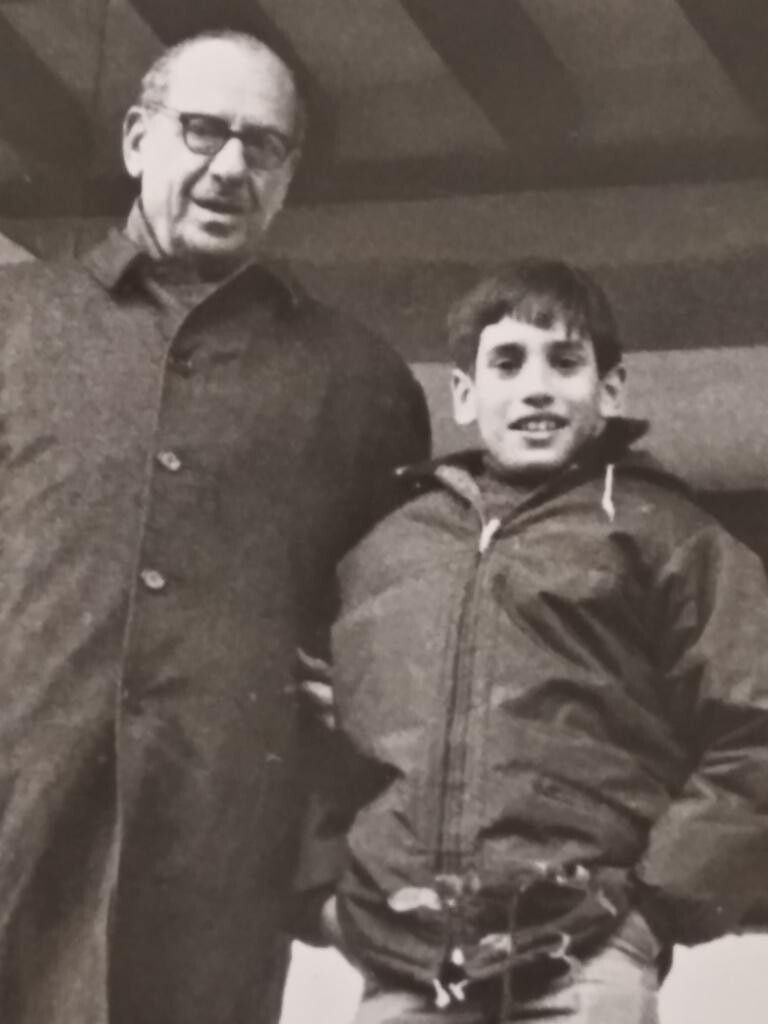

Broza at age 12 with his grandfather in Spain. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: Your grandfather?

DB: Yeah. Then he went and he heard one of the first Zionists speak to him, which was Chaim Weizmann, and his mind was blown away. Said he found a purpose. Connected to him, and inspired by the Zionist dream, he created in 1925, a Boy Scouts movement called Habonim, because he was a Boy Scout. But he was a disciple of [Robert] Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scout movement, which was a Christian movement. He wanted the Jewish kids from East London to have something, some activity.

So he translated what he learned in Boy Scout-ism into Habonim, which became basically a global, Anglo movement, which was responsible for a lot of people. It changed their lives. Then he immigrated to Palestine in 1925, and started his life in Tel Aviv, where he married my grandmother, who was born in the Turkish empire, and they moved to Tel Aviv together. My grandmother’s family founded a town called Rehovot, where the Weizmann Institute is, and her brother is one of the founders of the first kibbutz, Deganya. So this is heavy. It’s so deep.

AZ: It goes so deep, which is why when you think about being pulled out at 11, moving to Madrid under Franco, this crazy dictatorship.

DB: Oh, and there’s another angle to it. We moved to Madrid and my father’s mother…. Well, the listeners are probably, by now, dizzy. When my father moves us to Madrid, right after the Six-Day War…. His mother, who is Dutch, from Amsterdam, they’re Marranos, who escaped the Inquisition five hundred years before.

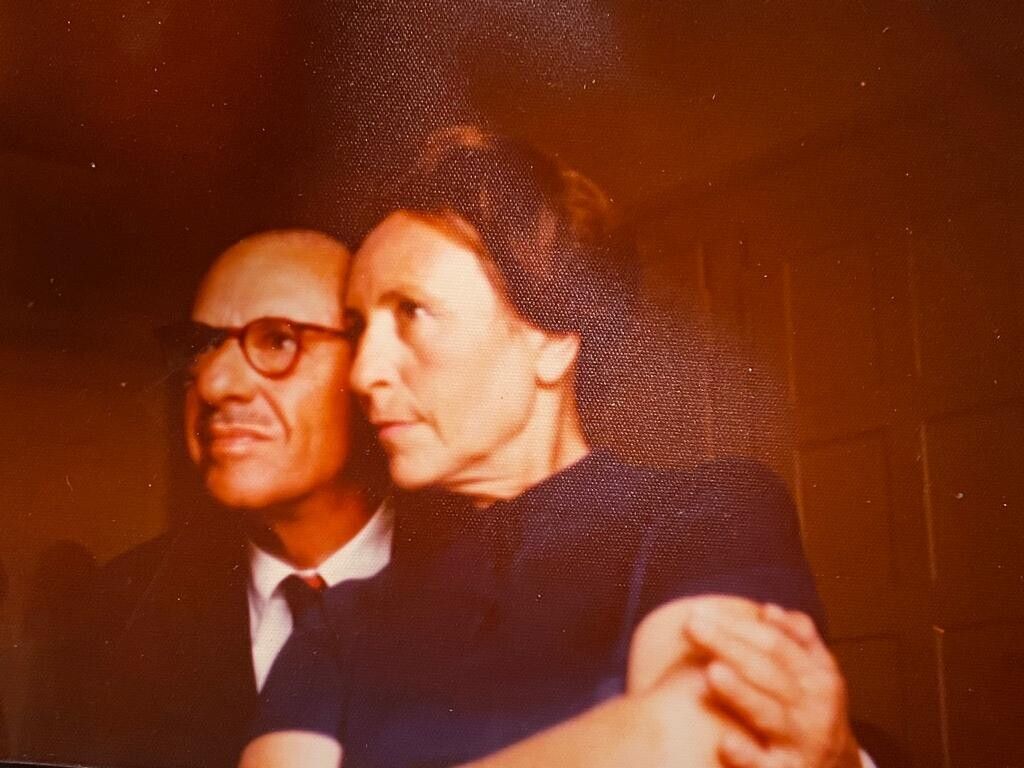

Broza’s grandfather, Wellesley, and grandmother, Rose. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: I mean, I was going to get to this idea of—

DB: No, unreal. So she says to him, “If you move to Spain, I will sit shiva over you.” Sitting shiva means you’re dead, and I have to mourn you now. That’s how extreme the effect of the Inquisition, let’s say, is on these people, on the Jews five hundred years later. Nevertheless, he moved to Spain. And three years later, she comes to visit. She misses him. So she brings him back from the dead. She didn’t sit shiva in the end, she just threatened. He was too dear to her, but she did come and visit us in Madrid.

AZ: The guilt.

DB: And it was hard. It was hard. So this is historic, because my father’s father comes from Hamburg which is another place where the Jews escaped to, from Spain. They got a passage that they could go to Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Hamburg, port towns. So he arrived at the port. His family had traveled to Hamburg, Poland, back to Hamburg, then London. My grandmother’s family in Amsterdam established one of the first synagogues there. And during World War I, she moved to London with her siblings, eight sisters and brothers that she was taking care of. They moved to London. That’s where the Dutch meets the German, and creates the Broza family. My father is born in London as a first-generation British. But by the time he’s ten, he’s already moved to Palestine. So he only spent ten years of his life in England, but he was never able to get rid of the English style of….

Broza’s parents, Sharona and Arthur, in 1953. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: Well, it starts with his name.

DB: The name?

AZ: Yeah.

DB: Well, Broza. But Broza was really a Spanish name, later on, I found out.

AZ: Right. So you go to Spain, and you’re under this rule of Franco. Is this the beginning of thinking about intolerance, and were you feeling it? Do you remember feeling it at that age? Like, “What is this about? Why can’t human beings get along?”

DB: No. I did read a lot of interesting books, and the principal of the school, the headmaster of my school [Runnymede College], was a Trotskyist. As a matter of fact, he was a Trotskyist. His name was Arthur Powell, a brilliant, great man with a vision, and he started this school. We were forty-five students in the entire school, and it eventually became a bigger school, several hundred. But he always guided us. He was my history teacher, too.

So I think all of these elements contributed. Mind you, he was a Trotskyist, but I sat in school for seven years next to Maria Romanov, the Grand Duchess of Russia. So it was a very, very intense history class, in which we all became experts in the Russian Revolution, And poor Romanov, Maria, she was trembling in every class, because it’s about how you get rid of the Czar. And that’s her family.

AZ: Fascinating. So we talked a little bit about it, but you’d originally planned to become a visual artist. You were making paintings, you were selling them in the market, and you wanted to go to RISD.

DB: I did.

Broza at age 16 with his sister, Talia, in Madrid. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: And somehow, that didn’t happen. The army happened.

DB: I couldn’t afford RISD. Nobody offered me. I mean, my father could have never—it would’ve killed him. Had I asked him, he would’ve wanted to, very much so, to support me. Carmel College was hard enough. That was one of the most expensive schools in England, where I went to that religious school, but he had money that year. His life, as a venture capitalist, he just was ups and downs, and ups and downs. But he was a bon vivant. He had a wonderful approach to life, which I certainly take from him. I’m lucky.

AZ: Did the army shift it? Because after the army, you could’ve pursued visual arts, but did something about the army and all the playing, did something shift for you?

DB: No doubt.

Broza (center) performing with his sister, Talia (left), and Israeli pop and rock singer Dafna Armoni in 1976 during his time in the army. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: Did you continue to draw during that time, and paint?

DB: I continued to draw. I continued to draw all the way until the day when I wrote “Yihye Tov,” that first song. And I continued to draw even after that, a little bit. Yehonatan Geffen, my friend, loved those drawings, and I gave him a couple.

Broza performing at a concert. (Courtesy David Broza)

But I had a record company starting to pursue me, and trying to get me to sign a record deal, because I already had a number one hit on the radio. But I didn’t take it seriously. And she was following me since the army days. And she said, “No, you have something in you. I don’t know why you think you want to go to RISD, or any other university, because you’ll be studying five years, and then you’ll start your career. Here, I’m giving you a five-year, five album contract.”

AZ: “Let’s go.”

DB: “Let’s go! All financed. You can do shows and live.” And eventually, I signed with her. It was CBS Records.

AZ: And at some point, you met your first wife, Ruth [Gabison].

DB: Yes.

AZ: Who is also your collaborator in business.

Courtesy David Broza

DB: Yes. So Ruthie was working in the hospitality business. She was in the hotel, Sheraton hotel, and we met, we married within seventy-two hours. We were married, and a year later, we had—

AZ: The day you met?

DB: No.

AZ: You had already done “Yihye Tov?”

DB: Oh, yeah. I already had an album.

So she met me and we went out on a Friday, and I proposed on a Saturday, and we married on a Monday or a Tuesday. On Monday. Not important, but yes. Nobody was there except my sister, and a friend of mine, and another friend who was studying to be a rabbi. So we had two witnesses. That’s all you need in Judaism in order to marry by faith. If you want to marry by law, you have to go to the rabbinical or somewhere, and sign the papers, but we were married by faith.

AZ: And you guys eventually went on to make three children.

DB: Oh, no. We already had two children.

AZ: You already had two?

DB: We were 23, 24. We already had two children.

AZ: Amazing.

DB: Yeah. We got married in three days, and had two children in four days.

Broza (center) with daughter Moran (left) and son Ramon (right). (Courtesty David Broza)

AZ: And then you moved to New Jersey. I think about this move. It happened a few years after this, but you were this huge force in Israel.

DB: A meteor.

AZ: Yeah, and then you just yank and go to a place nobody knows you.

DB: Correct.

AZ: Why did you do that?

DB: It goes back to that question of yours about celebrity, or superstar. Well, as I said, I was not an accomplished artist. I’d started at 22. By the age of 26, I’m a household name. By the age of 27, every house has my album. Well, two or three of them, the same album.

AZ: It went triple platinum.

DB: Quintuple, six-platinum. Endless. Let me tell you, the record industry did not report to me how many they sold. By my account, they sold a million records. The report that I know was about two hundred and twenty thousand. So imagine how much is missing out of my pocket.

AZ: At that moment. Yeah.

“I was very, very big, but it meant nothing to me, because I hadn’t worked for it. I didn’t sweat like I did in paintings from the age of six, learning techniques and trying things out.”

DB: So forget it. I’m not even claiming. It doesn’t matter anymore. But I was very, very big, but it meant nothing to me, because I hadn’t worked for it. I didn’t sweat like I did in paintings from the age of 6, learning techniques and trying things out. Wow. Obviously, it brewed in me for years, but I was not aware of it. And I did not envision myself [as a musician] because my mother was a singer. And whenever I saw her sing, I would cringe. I would be so embarrassed. I’d cry. I’d pee in my pants, in front of audiences. I would sit in there, and that gave me a terrible fear of the stage. I didn’t want to be on stage, nothing. Didn’t mind playing rock and roll in my garage band, but I didn’t want to be on stage.

So now, I become this artist, and I have to get over all these.… I don’t know. I mean, in today’s world, it’s a little different. You can become from nobody to somebody who has a million followers or a hundred million followers on Instagram and on TikTok, and all that. It means nothing. If you’re not the artist that you’re selling, you walk out of that realm of TikTok, you’re on the street alone. It’s nothing. I don’t want to be that. Not my type, not my style. My integrity—I was born with that in me.

“If you’re not the artist that you’re selling, you walk out of that realm of TikTok, you’re on the street alone. It’s nothing. I don’t want to be that.”

So, I’m big. I have a lot to learn. I have a lot to discover. I want to see where Hendrix came from. I want to see where Bob Dylan came from. I want to see where Rauschenberg came from. I want to see where Andy Warhol came from. I want to see where all the arts came from—the jazz, the folk, the pop, the visual. I want to see it all. Where is it all? It’s all in America.

Broza performing at a concert. (Photo: Ehud Lazin. Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: You wanted time to hone, though.

Broza in April 1989 during his time in the U.S. (Photo: Tami Porat. Courtesy David Broza)

DB: I needed to earn it. So I earned it by doing a seventeen-year tour in the United States—in the back roads, and the coffee houses, and the stinking bars, playing with a one-hundred-and-two-degree fever, sick or well, rain or shine—and always on the road. Always performing. And at the same time, raising a family, and constantly being back home, trying not to be away from the house for more than a couple of days. Always. It was crazy to manage all that. And, at some point, to maintain my status in Israel, to keep on going back there. Because I’m pragmatic, on top of being an artist, which is what I have to maintain…. Also, I’ve earned something. I’ve been given the success, not to be thrown away as, “Oh, I’ll come back later.” No, no, no. You got to maintain it somehow.

But the first few years, I didn’t maintain it. Everybody was wondering, “Why did he leave?” I didn’t know what to answer. What do you mean, why? I’m still trying to figure it out myself. But there was something missing. I’m not here just to make a quick buck. I’m not here just to become famous. I want to be able to perform in any room, at any given moment, for one person or one hundred thousand. It’s the same thing to me. I want to manage this, and I want to be able to know, if I play the blues, I want to know the blues. You know?

“That’s why when I came to do the liturgic work now, it was such a great experience: because I discovered the music that lies within the words in front of me.”

That’s why when I came to do the liturgic work now, it was such a great experience for me, because I discovered the music that lies within the words in front of me. I was able to bring in all these miles, and miles, and miles that I’ve spent in trying to meet, and bring myself to the core of where it all [started]. So when I play flamenco—I’m not a flamenco player—but trust me, I emulate, because I’ve heard and I’ve been with the original source.

Now I’m giving it my interpretation. Call it what you may. Which brings me to this great guy, Bruce Lundvall, who was one of the greatest executives in the music business, ever. And he signed me on to his label at the time, Manhattan Records, EMI. And he said to me, “In this country, they’re not going to be able to pigeonhole you. And that’s a problem. But you have one label under which you should be proud to be, and they will have to learn how to write it. It’s called unique. Don’t be afraid of it. It’s not a four-letter word, as poetry is not a four-letter word.” And he was so into it. He poured money into my first album, and he believed in it. And he saw the results immediately.

But then he was moved to another company, so we didn’t enjoy the road together, the journey. But it was part of my journey. And I remembered that. Being unique doesn’t mean that you have to look different than anybody. I don’t have an ethnic background. I’m of no ethnicity, because I was born in Israel as an Israeli. It’s a young country. It doesn’t have an ethnic background yet. Maybe one day, it will.

AZ: Your identity was formed by so many different voices.

DB: By the arts.

“Being unique doesn’t mean that you have to look different than anybody.”

AZ: Yeah. And just by—

DB: Culture.

AZ: So many different voices.

DB: The voice.

AZ: Yeah. And just by being—

Courtesy David Broza

DB: Culture, the culture. I’m assimilated—Spaniard assimilated American, assimilated Englishman. But I’m an Israeli. I have many friends who are ethnic: Moroccan-Israelis, Argentinian Israelis, Yemen Israelis. Amazing. And the Russian Israelis, Polish Israelis, German Israelis, French Israelis. Like you have an Italian American, Greek American. These are cultures. That’s ethnic. My ethnicity has not been identified yet. It’s interesting, huh?

AZ: Yeah.

DB: Really interesting. And it manifests itself in my music, and the kind of work I do.

AZ: And all the mix of languages. I mean….

DB: Well, I’ve mastered three languages.

AZ: Are there some things that work in certain languages that don’t work in others?

DB: Of course. Most things don’t work. But interesting that Hebrew and Spanish have a similar rhythmic pattern to the language, the weight. So: [singing in Hebrew] “Ha’isha she iti einah mitakeshet….” [singing in Spanish] “La mujer que yo quiero no necesita….” In English, it would be, “The woman with me that makes”—that’s not a good phrase. “The woman I love”—no, that’s not a good one. In Hebrew and Spanish, it’s perfect. For me, it’s not a good one. Somebody else might find a translation—

AZ: And the music transcends all language, the guitar. I want to switch a little bit to twenty-one years after “Yihye Tov” came out, and you get into a terrible car accident in 1998.

DB: Oh yeah. Wow.

AZ: And your left arm was badly hurt.

DB: Wow.

AZ: What happened in the aftermath? And what I’m hoping to get to is to hear a bit about what some of the positive aspects of that experience were, when you got to the other side.

DB: Okay. Yeah. A lot of positivity, but first it was a tragic event.

AZ: What happened?

DB: So I was performing in a show in the desert, a very late show. Not very late, but kind of late. I was the headliner. And I took on a driver who was in NA, Narcotics Anonymous. And the police had warned me about him. He was also a convicted burglar, sat in jail and stuff. And I loved him. And I said, “Look, with me he’s going to be cool.” To the degree that he ended up owning three vans, a coffee house, opening another coffee house. Through me, he got the job driving David Bowie, Madonna, when they were in Israel. He was treated as very trustworthy.

So he was safe in my environment, because also the musicians with me respected it. You could smoke weed and all that, but he was not allowed. And that one night, he felt too good with himself. People saw him smoking, and he was hitting on girls. He should be asleep in the van, waiting for me to finish my job and to drive us. And he fell asleep at the wheel, driving ninety miles an hour. So he drove me and my band. I had a guest artist, who was two months pregnant, sitting in the front seat without a belt. I was behind him, as I always sit behind the driver, without a belt. Then I had my sound guy and my lighting guy. The car was totaled, and I was the only one hurt in the car.

Imagine the girl sitting next to him, the singer, her daughter’s now 22 years old, or 23 years old. Nothing happened to her. He broke his pinky, and all the other—they all had to be sawed out by the fire department. And with my teeth—literally, as you would say in a horror show—I pulled with my teeth, and I broke out of the car with my teeth, my head. I guess it’s survival, right? Of a human being. I hit it with my head and I came out. I was all bleeding, and I lost a lung at that moment, and I was paralyzed [on] my left and my…. Every bone was broken in my upper body. My legs were okay.

And we sat there, and I was taken away. And that singer, who was pregnant, held my hand. And since I have asthma—I thought I had a problem breathing, because I had an asthma attack. Actually I had lost a lung. I didn’t have an asthma attack.

AZ: A lung collapsed.

DB: A lung collapsed. But because I was asthmatic, I knew how to breathe when I can’t breathe. The same thing that you learn just out of sheer dealing with it on a daily basis. But when I got to the hospital, it was very severe, and the prognosis was that I might never get to play again, because my nerve was severed thirty-five centimeters above the hand, the palm of my hand on my left hand. I’m left handed, although I play right handed. So the prognosis was not good at all, but there was a doctor there who was very brilliant. And he said that there’s this very slight chance that the nerve will grow itself again, a millimeter a day. So we have to wait three hundred and fifty-five days.

So, my point of view was, don’t touch if you don’t have to. I trust these guys. And for the next year, many, many surgeons came to me and wanted to take the credit to bring me to the operating table, and do microsurgery, and all kinds of innovative stuff. And I went with his prognosis. I remember traveling to Spain while I was still paralyzed, and I was down in the south of Spain visiting a friend—a new friend, Javier Riba, a most incredible singer-songwriter. We’d become close friends and collaborators, and would write songs together on my Spanish albums. That’s when we met.

“I died. I know. In the accident—I saw that white light. I saw the whole thing. I actually was very happy, and I said goodbye to…. I saw everything.”

He invited me down because he’d heard about my accident. I had a lot of following in Spain due to the success of the album. I did translate Spanish hits to Hebrew, but it was mostly musician’s musicians—only real aficionados who knew, the ones who follow music worldwide. And he invited me out of concern and love, and respect, to visit him in Puerto Santa Maria, which is near Cadiz. Puerto Santa Maria, historically, is also the town where Columbus left with his ships, and discovered America. Cool little town.

So I go to visit Puerto Santa Maria. I stay in a monastery there, and Javier meets me. So we go to his house, and he tries to teach me two songs. He says, “That’ll be a good exercise for you, to get your hand working.” So I’m trying to learn, and I feel something. The next day, the hand was like this [moves hand]. The next day, suddenly the hand flickers, goes…. [Moves finger] Suddenly moves. [Gasps] It’s the three hundred and fifty-fifth day. Unreal. Unreal. I call my promoter in Israel, Suki Vice, a great guy. I say, “Suki, book Masada. We’re going back to business.” I didn’t even know if it was going to happen or not, but I saw the flicker. What is that? I’m asking you, what do we know? What is it that makes you feel…. While there’s even a little bit of breath in you, you still get up. Can you explain this?

Photo: Ehud Lazin. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: If you feed the life force so much over so many years, it’s got to feed you back.

DB: I guess.

AZ: The amazing thing about time, which ultimately is what we’re so interested in with this program, is that all of the technology and all of the things that were offered to you may well have made it not come back, but allowing the time for the body to heal itself—

DB: Of course.

AZ: Is what happened. It’s so fascinating. And a year of commitment, ten days short of a year.

DB: Wow. Well, first of all, after the accident, I came back to New Jersey many, many months later. I couldn’t fly. There was a gentleman who wanted to take me through a hypnosis to let the trauma surface, and see what it was. I didn’t want to. I was reluctant. No, no. In the end I went, and I actually saw everything. I actually saw an out-of-body experience. I recognized it. I saw the whole accident. Everything. I also discovered that I embraced it, and that I embraced the pain. I remember it… just, take me.

AZ: And you come back super strong, and a lot happened. In 2012, four years later, you were appointed a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF. When you were asked, did you have a sense of what that opportunity was going to become? Because you…I don’t know what more you could have done with it. It’s kind of phenomenal what you did.

DB: The truth is, I could have been much more useful for UNICEF, but it’s a very big body. In Israel I can be, and I do what I can. I find that when I do my own thing, rather than working with big bodies, I get results—real results. A big body is UNICEF. But if I do my projects of conflict resolution, coexistence, my work with Palestinians, Palestinian refugees…. Now I have this beautiful project called One Million Guitars, which is to me…. I mean, I wish a big body would come and say, “Look, here’s the budget.” One organization feeds the world. Another one feeds them with inspiration. This is what these guitars do. I designed this guitar. I manufacture it. We’re in with organizations that are in forty-three states in this country, in thirty-three hundred schools. So we just have to—

Broza speaking to a class as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza with children who received guitars as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Children who received guitars as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza speaking to a class as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza with children who received guitars as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Children who received guitars as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza speaking to a class as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Broza with children who received guitars as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

Children who received guitars as part of the One Million Guitars project. (Courtesy David Broza)

AZ: How many have you given out today?

DB: Several thousand. Probably so far, about forty-five hundred. But the beautiful thing for me is, besides the United States, where it’s in almost every corner, but in Israel now, we have the entire program. Not just giving the guitars to programs, but we are the program. We have teachers on salary teaching our curriculum. And the schools are in very kind of neglected corners. Although there’s a neglected corner even in the privileged corners. There’s always the wealthier and the poor. The poor are the ones that need more support, because the system can’t see everybody.

I’m not trying to blame anybody. This is the system. And in Israel, so now we have Bedouin villages, where children definitely are not guided to play music. Absolutely not. In the Arab world altogether, music is not secondary, is out of the realm, but there’s a beautiful school called Polyphony, which is based in Nazareth. Beautiful school. I’ve been advising them. I’ve been on the advisory board and all that since almost when they started, and they teach classical music.

When I decided to bring One Million Guitars to Israel, instead of opening my own foundation, I said, “Let’s do it with them.” With Polyphony, we have ten thousand students learning music, appreciation and music. Polyphony is actually taking care of the curriculum. We have dozens of schools already, even though the Covid stopped us from moving [quickly]. We’re only two years into it. And now I’ve already given out fifteen hundred guitars in the country. We come into a class, whether it’s in the United States or in Israel—

AZ: Which, they want more than a violin, probably.

DB: You know what? They’ll take a violin.

AZ: Yeah.

DB: I don’t relate to violins like a guitar. That’s my instrument.

AZ: Yeah.