Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Viet Thanh Nguyen

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Viet. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

VIET THANH NGUYEN: Hi, Spencer. Thanks for having me.

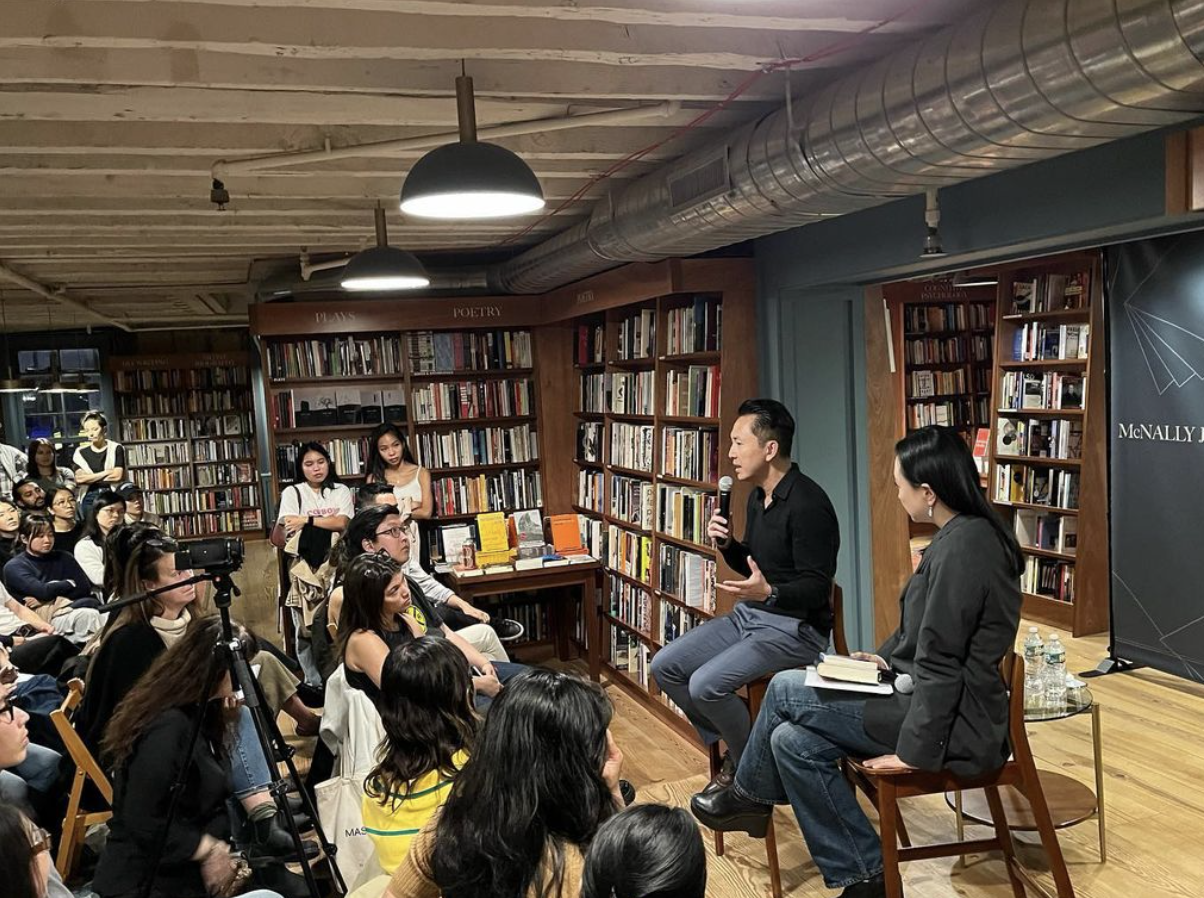

SB: I thought we’d start today on one particular moment in time—October 20th, 2023—and then we’ll get to the current moment. I bring this up because I interviewed the novelist Min Jin Lee that morning for this podcast, and you were scheduled to appear at the 92nd Street Y with her that night. Obviously—as the news reports soon after shared—the event was canceled. You did end up doing a talk, but just not at the 92nd Street Y. Now that a little more than six months has passed, you’ve probably had a little bit of time to reflect on this. How are you thinking about that particular day and moment?

VTN: That was one of the most stressful moments of my life and probably the most stressful moment of my authorial life. Min and I had some extensive conversations that afternoon or early evening trying to figure out what we were going to do and her concerns for my safety. It was the beginning of just a moment of intense, I think, moral and political and artistic testing for me—which I appreciate in retrospect is certainly something that I wouldn’t have chosen. But it was a consequence of things that I did choose to do, which immediately preceding October 20th was to sign a ceasefire letter along with seven hundred or so other writers—a letter that I think, in retrospect, was very, very moderate in the tone that it took, and what it was asking for in terms of a ceasefire, things that I think would not be very controversial right now, but in the wake of October 7th were quite controversial. So with the passage of time, I think that, as I said at that moment, I have no regrets over anything I’ve said or done regarding Israel, Palestine, Gaza, the war, ceasefire, and everything related to that.

I see myself as a writer who deeply believes in art and beauty, but also in truth and commitment. That’s the kind of genealogy of writing that I come out of. That was a real test for me, and I’m actually grateful that I had that opportunity.

SB: You write a bit about F. Scott Fitzgerald in your new book [A Man of Two Faces], and there’s a quote there that you’ve referenced that I wanted to pull up. I wasn’t familiar with it, and it’s so great and it connects to this, which is, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” [Laughs]

“Sometimes two things can be true simultaneously, and there’s no simple or easy resolution, no matter what some politicians or leaders or friends might want to tell us.”

VTN: It’s a beautiful quote. It’s one of my favorites from F. Scott Fitzgerald, because I think he’s right. We’re not unique in that we live in times in which there are radically diametrical political beliefs in operation at the moment. And sometimes two things can be true simultaneously, and there’s no simple or easy resolution, no matter what some politicians or leaders or friends might want to tell us.

We have to dive right into the murkiness and the conflict. It’s not very pleasant, obviously, but for people who work in ideas as artists or as intellectuals, as teachers—hopefully as university administrators—that’s exactly what we should be grappling with. That’s what we do with our lives and our work. Again, I would rather just spend my time sitting in my nice office writing up my nice novel, but the friction that Fitzgerald indicates, that uncomfortable friction, that’s actually where I think really provocative work comes from.

SB: Contradiction, too.

VTN: Yes.

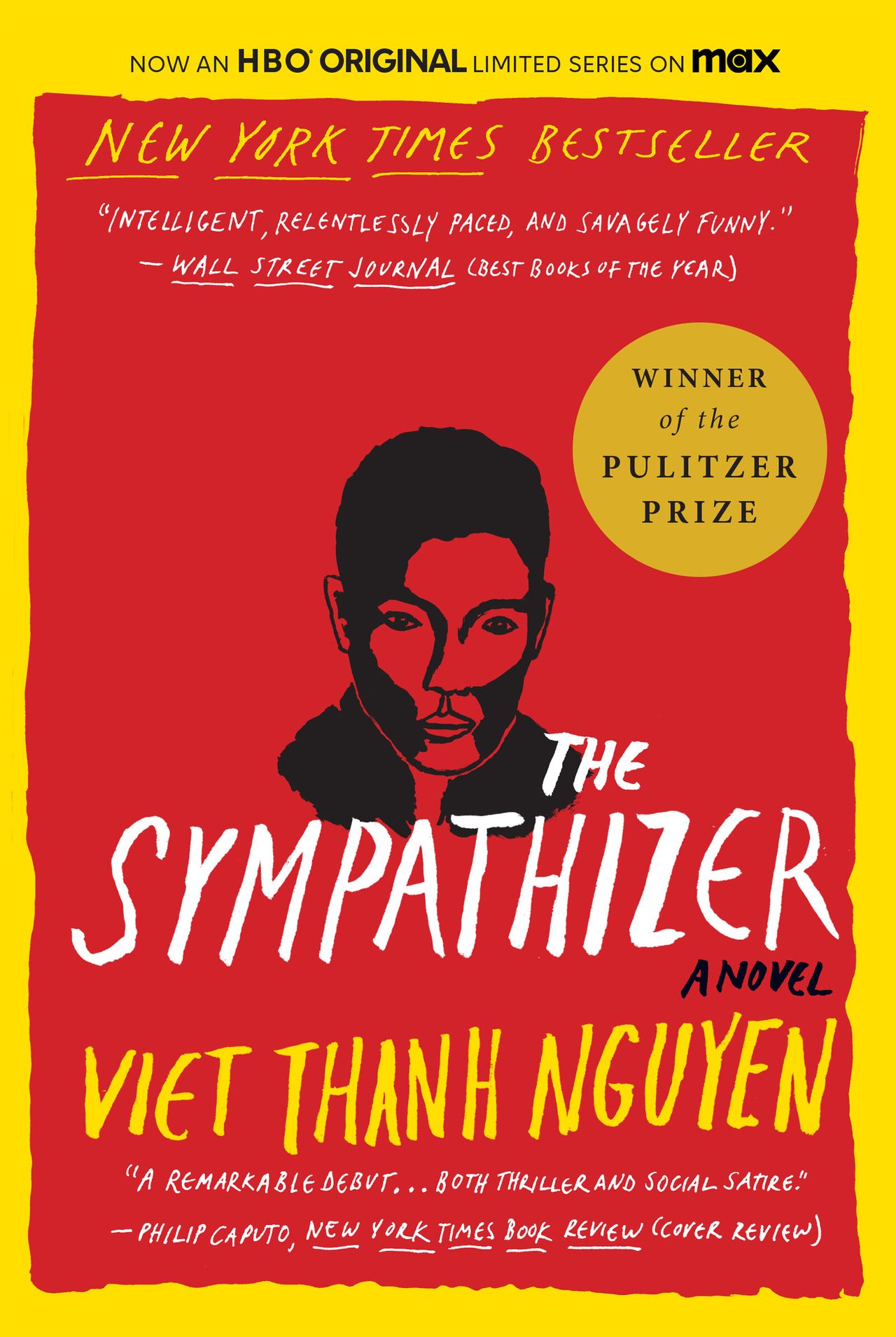

Cover of The Sympathizer (2015) by Viet Thanh Nguyen. (Courtesy Grove Press)

SB: Bringing this into this very moment, it’s a really exciting time for you. Just three nights ago you made your on-screen debut [laughs], in The Sympathizer, the HBO miniseries adaptation of your 2015 novel of the same name, of which you’re an executive producer. What was it like for you to enter the world of HBO and Hollywood in this way and on-screen?

VTN: It’s really interesting, because I live in the world of books. I love books, and so do all my friends, but honestly, even my friends who are writers and professors and so on, they were so excited about this TV show. “Congratulations on the TV series.” I’ve gotten so many more congratulations and excitement than I had upon publishing the book itself. It just illustrates the world of entertainment, ideas, and media that we live in, in which what I care about the most, which is writing and ideas and novels, is still quite secondary for most people—even to those people working in these spheres—to television and entertainment and movies and this entire spectacle.

I’m seduced by it, too, because it is a lot of fun to go hang out and have a private lunch with Robert Downey Jr. for example, or do a photo shoot with Sandra Oh. These are incredible opportunities, and I’m enjoying them greatly. I think of it all in the same way that the Fitzgerald quote that we just talked about—that this is the reality we live in, so I want to operate in it so that my ideas can be leveraged and transmitted out through a different medium that will reach a different audience and maybe a larger audience. And yet, at the same time, I also recognize that it’s also just entertainment.

SB: Hollywood is something you write a lot about in your memoir, A Man of Two Faces, which came out last year, and which I should clarify is as much a memoir as it is a book of history and a memorial. It gets into this Hollywood mythologizing, so I imagine this HBO experience has been particularly heady in light of that. [Laughs] In the book you note the “hypnotic power of Hollywood,” which, fairly, I think, you call “AMERICA™’s unofficial ministry of propaganda.”

Nguyen (right) on the set of the HBO miniseries The Sympathizer in 2023. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

Elsewhere you note several classic Hollywood films, particularly related to their depictions of Vietnam: Casualties of War, Apocalypse Now, Platoon, and The Deer Hunter. I should also add that you’re authoring much of this book in the second person. There’s a quote here I wanted to bring up, which is, “You are determined, against the dehumanizing force of Hollywood and its drive of representation against Vietnamese people, to humanize the Vietnamese and give them a voice.”

A long-winded question [laughs], but now that you’ve had The Sympathizer find its way to HBO, how are you thinking about this evolution and time span, from the twenty years it took to publish your first novel, the two years it took to write it, and now this HBO show, in light of that quote I just mentioned?

VTN: I think about the fact that when it comes to being a writer, the only thing that’s really required for a writer is the writer’s life—and no one cares about the writer’s life, so that costs nothing except to the writer—whereas a TV show of this scale that we’re talking about is at least a hundred million dollars. Now everybody cares because it’s a hundred million dollars.

Nguyen giving a talk on October 20, 2023, at McNally Jackson Books that was originally scheduled to take place at the 92nd Street Y. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

The project of dehumanization and humanization is really complicated when you look at it in that landscape, because I think the dehumanization is real. I was deeply affected by watching America’s movies about the Vietnam War. I felt that we, as Vietnamese people, were dehumanized in so many different ways, and I think that most of the world didn’t recognize that dehumanization. Most of the world who saw these movies just accepted them as stories or as entertainment or as spectacles. We didn’t matter for most of the world in that. So the necessity to humanize and to seize whatever methods we can to tell our stories is really, actually, pretty important. At the same time, of course, now that it’s taking place, I can also very easily say that that humanization is still trapped or working through this gigantic corporate mechanism with all kinds of its own contradictions and its own complications.

I think the book itself and my work, in a larger way, complicates even that desire for humanization, because I do ask the question, I think in the book and elsewhere, well, what does it mean to be human? Why do we have to prove our humanity? And what about the complexities of “humanity”? Most people are so eager to claim their humanity and not recognize the inhumanity within themselves or their friends or their collectivities, their nations. That’s really where the larger project goes towards.

SB: And in a way, it’s funny, because it makes me think, hearing you say all this, of this New York Times review that came out following the publication of The Sympathizer where, and I’m going to paraphrase—I’m probably not getting this exactly right—the reviewer wrote that you were “giving voice to the voiceless.” Keeping that in mind, I guess [laughs], how do you think about that notion? Obviously, I’ve heard you write and speak about this idea of voicelessness and you do write about it in the book, but how do you think about that in the context of Hollywood and this particular project?

“Most people are so eager to claim their humanity and not recognize the inhumanity within themselves or their friends or their nations.”

VTN: There are narratives out there that are very easy to fall into. “Let’s all be human together,” for example. “Well, let’s all get along.” Who can dispute that and “giving voice to the voiceless”? Who can dispute that? I mean, people still say it to me and to other people in my similar situation, “Thank you for speaking up. You’re giving voice to people whose voices can’t be heard,” which is actually probably more accurate than “the voiceless.” I like to quote Arundhati Roy, who says, “There’s really no such thing as the voiceless. There are only the deliberately silenced or the preferably unheard.” That’s much more accurate.

We have to draw attention to the fact that, in order for someone like me to speak, all these other people have to be silenced. There’s an agency; there’s an action taking place. I distrust anybody who willingly embraces that idea that they’re going to be a voice for the voiceless or the people who celebrate that kind of thing, without acknowledging that these voices wouldn’t exist without condemning all of these unknown numbers and masses of people to conditions where, no matter how loud they shout, they can’t be heard.

I grew up in a refugee community surrounded by really loud Vietnamese people. They definitely had voices—

SB: [Laughs]

VTN: —and if you lived within the Vietnamese community, you heard them all the time. Even if we talk about a country like the United States, I think we have to recognize that there are some voices that are much, much louder than others. They get the platform, they get the megaphone and all of that. And then there are all of these diverse populations having all of these conversations within themselves that can’t be heard on the larger stage.

That’s where someone like me appears. I have to be very conscious of that dynamic so that I’m not naïve when I say words like the human or voice. I can’t be naïve and think that just because my story has been told that, oh, we’ve solved the problems that I’m talking about. We haven’t. So I think of myself as a writer who both wants to tell his story, but also draw attention to what I call “the conditions of voicelessness” that have to be abolished.

SB: It makes me think about the importance of what it means to have a voice, whose voice. And in the case of your voice, obviously you win the Pulitzer Prize and then you’re kind of catapulted up to being a quote “thought leader” or whatever.

VTN: Oh, don’t call me that.

SB: [Laughter] I said “quote.”

VTN: Influencer, thought leader.

Nguyen (center) at the Pulitzer Prize award ceremony in 2016. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

SB: But yeah, put on that pedestal or platform. And how did you contend with that, going from a very respected professor, but maybe not a household name?

VTN: When I was in school at Berkeley as an undergraduate and a graduate, the writers and intellectuals I admired were what we at the time called “organic intellectuals”—writers who did believe in art and beauty and all that, as I said—but also believed in writing from very particular historical conditions about particular political revolts and who attached themselves to social and political movements in addition to artistic movements.

In fact, I think I was always working in that vein, even as an undergraduate. I didn’t want to call myself an “organic intellectual.” That, to me, was as pretentious as “thought leader” or “influencer.” It’s not something that one should claim.

SB: [Laughs]

VTN: That’s really a title that people should give to you whether you like it or not. But it was always something that I wanted to do, and I think my career was dedicated to it.

Winning the Pulitzer Prize just amplified that situation, but it wasn’t as if it changed what I was saying or who I was. I simply took advantage of what we now call a “brand” or a “platform”; again, terms I really object to, but this is the terrain in which something like a prize or a publication or a TV series happens. This is not up to me. This is the entire media apparatus of attention and celebrity and amplification that takes place. I am very wary of it, but I also recognize that I have opportunities to use other people’s perceptions in order to get my point across. So people who invite me to things and say, “We want you to be provocative,” should be a little bit careful about what they think of in terms of provocation, because I’ll try to seize that opportunity.

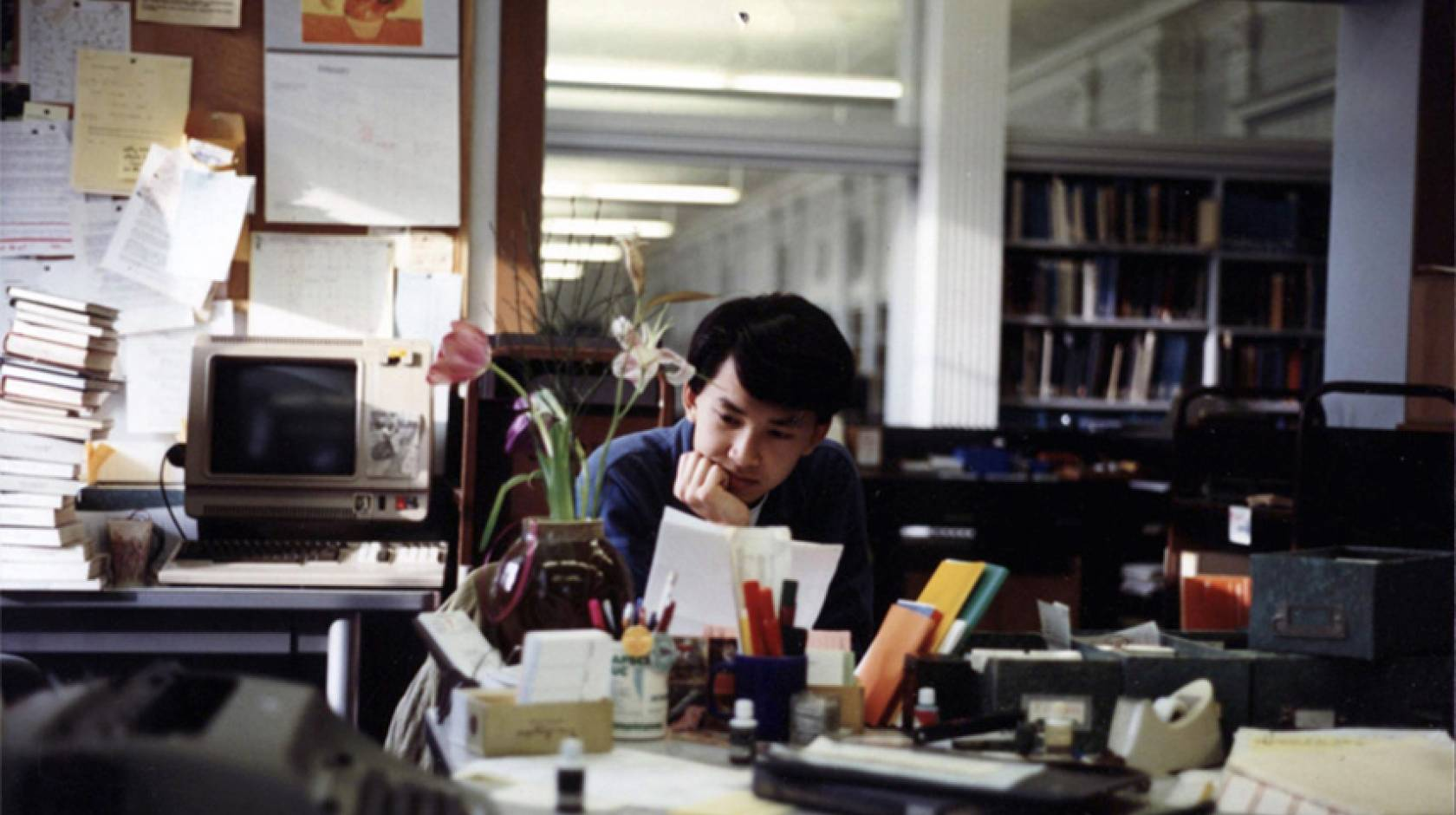

Nguyen during his time as a student at the University of California, Berkeley. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

SB: Connected to this, you have written about how majority populations live in—and I love this phrase—“a luxury of narrative plenitude,” this idea of narrative plenitude, whereas there are fewer stories of or about minority groups who, as you put it, “dwell in narrative scarcity.” This dichotomy between plenitude and scarcity, could you add to that a little bit and how you think about it through a time and memory and maybe even memorial perspective? Because I think you’re a really interesting example of someone who’s been able to experience it firsthand, but also see the ups and the downsides of both the plenitude and the scarcity.

VTN: When you live in narrative scarcity, almost none of the stories are about you and people like you. Of course, that means you and people like you put enormous burdens on stories that appear that are about you or people like you, and it’s an unfair burden. But the way that time, I think, and memory filter into this is because once you have this opportunity—if you live in narrative scarcity, and then you have the opportunity to tell “your story,” and I’m putting quotation marks around that—then time often comes in because the writer or the artist oftentimes feels an obligation to the community that they come from. To memorialize that community, to think nostalgically—and that’s about time—to think back on what their parents and grandparents or their ancestors had gone through.

“Nostalgia becomes problematic, because of course we should love and respect our ancestors and our elders, but they were people—as are we.”

That’s all very crucial, but it can lead to an art that is invested in sanctification. That’s when the nostalgia part becomes problematic, because of course we should love and respect our ancestors and our elders and so on, but they were people—as are we. And as I mentioned earlier, that means we’re human and inhuman, which means they were very imperfect people almost by definition. So that’s the contradiction that narrative scarcity produces the desire to tell very necessary stories, but then also the desire to whitewash or homogenize these stories in certain ways.

What plenitude means for me is to create conditions where we don’t have to worry, we don’t have that anxiety about having to pretend that there aren’t these imperfections, these flaws, these—even evils—that have existed within our people, our community, whoever we’re telling stories about. And that’s not just a luxury; that’s a real source of power to be able to think in that way and to create in that way.

SB: Story is time in that sense. And the time we give to story, I think, really can be reflected— I mean, you hear people talk a lot about “time scarcity.” We don’t hear people talk about story scarcity so much, narrative scarcity. I think that that’s actually really a compelling thing to think about. If we give more time to the narratives that don’t get enough time, what might happen.

VTN: Time operates in many different ways. I mean, there’s certainly time as in attention, what you’re talking about. We have a finite amount of time and we have to decide which books we’re going to read, which shows we’re going to watch and so on. I’m quite aware of this because I’m looking fairly closely at the reception of The Sympathizer, not just in terms of what does Time magazine think of it or these professional reviewers, but what’s Twitter saying? What’s Reddit saying?

And there are a lot of comments where people are like, “Well, I don’t know. I mean, I just watched Shōgun. Maybe I should watch Fallout. Maybe I should watch Ripley.” So people are already debating, with the finite amount of time they have, which TV series are they going to watch? What are their priorities going to be? And that’s a complicated set of criteria that people are bringing to it.

But the other aspect of time, I think, is the time of the creator, the person or the people who make something. In order to have that time, that’s also a luxury. My parents, when I was growing up, they worked in a grocery store—or they owned a grocery store—and they had no time because all their time was being sucked up into survival, into running this grocery store. They had no time to read. In their luxury time, what do they do? They watch crappy TV series like Shōgun and The Thorn Birds [laughs], things like this.

“I grew up with the sense that, to have the time to be a writer or to be a student, to have time to think, to have time to work with ideas, to do podcasts—that requires luxury because you have the time.”

I grew up with the sense that, to be a writer, to have the time to be a writer or to be a student, to be a scholar, to have time to think, to have time to work with ideas, to do podcasts—that requires luxury because you have the time. You’re not worried. I don’t know about you, but I’m not worried about whether or not I will survive in this country. That’s not a concern. I have more mundane concerns than that.

So that sense of, for a writer, that time is a luxury that other people are paying for with their lives or their time—that is something that I think a lot of us who come from these kinds of conditions where we’re very aware of the sacrifices of the people around us, that conditions how, at least I think of myself as a writer. And oftentimes there’s a feeling of guilt and obligation because I recognize, and people like me recognize, we wouldn’t have the luxury of time if other people hadn’t sacrificed for it. Therefore, we better make some really good use of this time that is given to us as a privilege by other people’s sacrifice.

SB: Beautifully put. On the subject of time, in your new memoir, there’s this paragraph—it’s a stanza, really—and I should say here that there’s…. Would you call it poetry? There’s definitely a poetic sensibility to the book and the way that you’ve arranged it. It gets at what it was like or what it is like to be a refugee through a time lens. I wanted to read it here.

“Being a refugee always involves time traveling.

From one country in one time to another country

in another time. And most of all living in the

present while feeling the past, always

lurking, always haunting.”

VTN: Let me give you an example of that. I’m a refugee from the war in Vietnam; my entire family is. And in the chaos of 1975 of March and April, and April 30th was just yesterday, in our conversation, that was the end of the fall of Saigon. My family fled and we left behind my sister. I wouldn’t see her for twenty-seven or twenty-eight years, until I went back to Vietnam. Then after that, I didn’t see her again for twenty more years until she came last month to visit me and my family here. And that was her first visit to the United States, first visit to L.A., first visit to Hollywood.

“My consciousness, my thinking, my emotions have been shaped by this sense of multiple times that exist.”

And she timed it perfectly because I was able to take her to the premiere of the TV show, and she got to have her picture taken with all these movie stars and everything. She loved it. But that’s time, because my brother also came to participate in the premiere. And when he met my sister, that was the first time they’d seen each other in forty-nine years. So I’m always aware of time. I’m always aware of how history has shaped my time, both as a writer, but also as someone who, my consciousness, my thinking, my emotions have been shaped by this sense of multiple times that exist.

The time that my sister went through, that could have been my time if I’d been left behind. And her life went in a completely different direction versus me. So, time is relative, and I’m always cognizant that my time is paralleled by other people’s times—such as my sister’s—that are real, but also the possibility of alternate realities, parallel universes where my time would’ve been completely different. I am haunted by that, not haunted just by the past, but haunted by the consequences of the past in the present in terms of alternate possibilities of my own life.

SB: This in-betweenness isn’t just about being between two nations, it’s being between different times as well. You’ve talked about this experience as a “terrifying void between nations.” There’s the nether-land between here and there, and this is sort of a central theme, I would say across most of, if not all of your work. Like in The Sympathizer there’s a moment where the narrator goes, “When I reminded him that I did not belong here, he said, ‘You don’t belong in America, either.’ ‘Perhaps,’ I said, ‘but I wasn’t born there. I was born here.’”

Nguyen in Hạ Long Bay on his first return trip to Vietnam in 2002. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

VTN: I think about how when I went back to Vietnam, I would meet these men who worked there as businessmen from Korea and Taiwan. They had a nostalgic sense of Vietnam at the time—this was early 2000s. And for them, it was about time. They were thinking, wow, Vietnam of the early 2000s looks like Korea from twenty years ago, or Japan from twenty years ago. So they had a sense of time that was different as well. And by that, what they were sort of signaling to me was that the interruption of war and colonization had shaped the times of these nations differently: Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and so on.

If war hadn’t intervened in Vietnam, it would’ve been just like Korea. That’s what they were saying. That’s what they were implying. So there’s already a sense in which historical intervention transforms the times of the nations. If you think about time as developmental, as these businessmen were thinking, their thinking was, “If war hadn’t interrupted Vietnam, it would be just as capitalist as we are today, and it will be as capitalist if we just give the country time.”

In the example from the book that you read, I think that that narrator of that novel, who is not me, but who shares some emotional similarities to me, is a man out of step, out of time. He’s thinking in a different time register than a lot of other people. He’s thinking about revolutionary time. He understands how time operates in both Vietnam and the United States. And it’s like that Fitzgerald idea. Everybody wants to be in step. If you’re in step, you’re in the same time as the people you’re walking with. But if you have two ideas in your head, you have two beats going on. How do you walk to that? How do you step, how do you be in tune in time with everybody else around you? That’s what it means to be out of time, out of sync, if you’re aware of different historical possibilities and realities that your fellows around you may not be aware of.

Cover of A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial (2023). (Courtesy Grove Press)

SB: It really makes me think of the title of the book, A Man of Two Faces—a man of two times, in a sense. That title comes from this line at the beginning of The Sympathizer. It’s on page one. You sort of alluded to it that you’re not the narrator, but there are connection points. Could you go a little further there?

VTN: The opening line of The Sympathizer is, “I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces, and perhaps I am also a man of two minds,” something like that. I was growing up as this refugee, and in my parents’ very Vietnamese household, I felt like an American because that’s what I was exposed to in terms of popular culture and literature and so on. But when I stepped out of my parents’ Vietnamese household into the rest of the United States, I felt like a Vietnamese person spying on Americans. And I think that’s actually a very common experience for someone who is a so-called minority refugee, immigrant, outsider to have that experience of at least two faces, two times, two spaces. You’re trying to be in sync with these two communities, and if you are doing that, you’re always going to be out of sync at the same time.

Again, that’s a very normal experience. I felt that when I was 25 or 30 or 40 trying to be a writer that, why would I want to write about that? Because it’s so boring. But I took that feeling and I put it into the body of the spy who’s in The Sympathizer and amplified it drastically. After all of that, I think I realized, in fact, as banal as my feelings are, as quotidian as my existence is, that the job of a writer is actually to investigate not only the dramatic and the spectacular, but the banal and the quotidian, and to find the human and the universal in that. That was one of the impetuses for writing A Man of Two Faces, was for me to go back and to interrogate what seems so banal and so quotidian, but actually is deeply terrifying to me.

“To write a good memoir, you have to expose yourself. You have to go into the part of yourself—whatever that is—that is so terrifying that you don’t want anybody else to know about it.”

I think that one of the points of writing a memoir is to understand that, to write a good memoir, you have to expose yourself. You have to go into the part of yourself—whatever that is—that is so terrifying that you don’t want anybody else to know about it. You may not even want yourself to know about it, even if you’re just a banal-looking person on the outside. I think that exists for a lot of us, at least it does for me.

In order for me to access that, I had to start writing A Man of Two Faces with a pretense, which is that I wasn’t writing about myself. I was the sympathizer writing about me. So I created this character. I wrote through him for at least eight hundred pages now in two books, and then I turned his perspective back on me, the creator, in order to excavate myself.

SB: Fascinating. We could probably also have an hour-long conversation about the subject of memory alone.

VTN: Well, memory’s related to time.

SB: [Laughs] Personally, I find your use of language around memory to be profound. As I was reading your book, I kept underlining many of your phrases such as “the lost detritus of our past,” “a flickering single frame of memory,” “another Polaroid of memory,” “that marrow of memory.” I took particular note of this one line: “Through the windows of my sandcastle of memory, I can hear the ocean of amnesia, perpetual, invincible.” This is probably a very tricky and even slippery question, but how do you approach thinking about this intersection of time and memory or even time in memorial in your life and work?

“We’re always changing the facts of our past to better suit our present.”

VTN: Time and memory are definitely related and inextricable. I think the challenge for anyone who thinks about memory, whether it’s in a scholarly or artistic way, or even simply reflecting on one’s own life, is to realize that time inevitably changes memory. I don’t know of a way of escaping that conundrum because memory is not stable. Facts may or may not be stable, but memory is definitely not stable and we narrate facts in retrospect through our ever-changing memories.

I’ll give you an example that comes directly out of this book. The genesis for this book is that I took a writing class when I was a college student. I wrote an essay for that class, which was about my mother going to a psychiatric facility, which is obviously devastating for her, but also traumatic for me. I wrote that essay when I was 19, and I put it into a box and I didn’t look at it again for thirty years.

I only opened it during the pandemic to start investigating myself. And I certainly did not forget over those thirty years that my mother had gone to a psychiatric facility. What I thought I remembered was that she had gone when I was a little boy. I opened the essay, read it, a couple of years ago, and realized that I was 19 when I wrote that essay. And my mother had gone to a psychiatric facility when I was 18, so it was only the year before.

Somehow, even as a full-grown adult, my memory had changed the facts. And if I hadn’t written that essay, I wouldn’t have the facts as I saw them at that time. But the indisputable fact is that it was when I was 18, not when I was a little boy. So whether my memory was a part of me or not a part of me, it had changed these facts in order to, I think, better express how I felt—that this was so traumatic that I was reduced to childhood in the face of watching what was happening to my mother.

Time itself had been changed in my remembering, but time had probably also affected my way of remembering, simultaneously. And that basic paradox, I think, is something that we live constantly. We’re always changing the facts of our past to better suit our present.

SB: Could you share your earliest memory?

VTN: My earliest memory was when I came to the United States—I was 4 years old—as a refugee with my parents, and we ended up in a refugee camp in Pennsylvania. In order to leave that refugee camp, you needed a sponsor, but there was no sponsor willing to take all four of us. So one sponsor took my parents, one sponsor took my 10-year-old brother, one sponsor took 4-year-old me.

“My family had to try to survive in the United States. We all had to look forward. And yet we were, I think, always being pulled into the past.”

So my first memories were of me howling and screaming as I was being taken away from my parents, which was being done for benevolent reasons. But when you’re 4, you don’t really, obviously, understand that. And what was interesting about that is I came home after a few months and then we all had to get on with our lives. We all had to try to survive in the United States. We all had to look forward. And yet we were, I think, always being pulled into the past—that Fitzgerald quote, another one from The Great Gatsby, where this boat’s being pulled forward, but being borne ceaselessly back into the past.

I think that that was true for a lot of refugees. We all had to move forward to survive economically, but so many of us were being pulled back into the past at the same time. So there was always that tension between the forward and the backward. In regards to that particular memory of being 4 years of age, I certainly never forgot it. But I also felt that, in a teleological sense of time, that I had moved beyond it, that it was all in the past.

And then when my son turned 4, in 2017, it was the moment when the Trump administration was enacting a border policy where children were being separated from their parents and being put into cages and being lost in the system. I was very upset and angry about that, partly out of my own political convictions, but then also out of my own memory of what had happened to me. Looking at my son who was at 4 years of age, it just propelled me right back into the past.

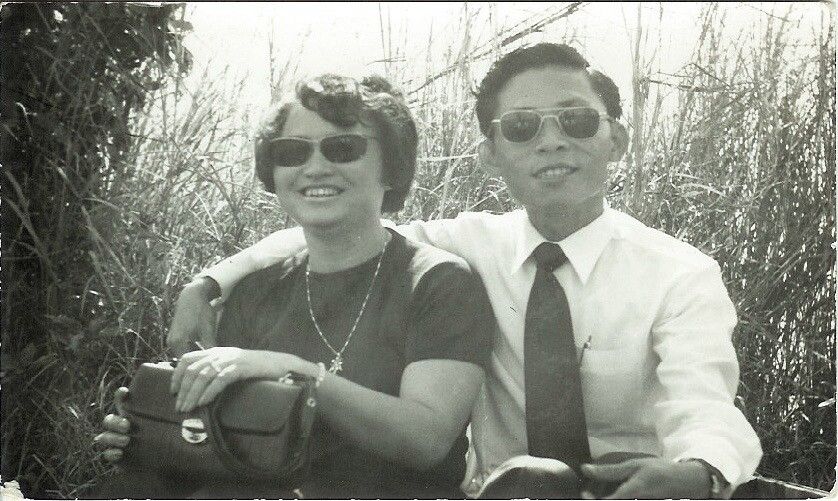

Nguyen's parents, Linda and Joseph. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

For the first time, at that point, in forty years or so, forty-plus years, I looked back on myself as that 4-year-old boy and had greater empathy for him and what he had gone through. I had greater empathy for my parents, which I never thought about before. I never thought about, Well, what did my parents go through? And I realized, looking at my own 4-year-old son, I would never under any circumstance agree to having him taken away from me. So what was it like for my parents to have to agree to that?

That was just a moment where, again, it was very clear to me that time was not linear because I could already see ahead and see that those families at the border who had lost their children and the children themselves, they would never forget this moment. They would be scarred forever by this, and their entire lives would pivot around this moment. There was no moving beyond that for them, even as their lives obviously would move forward, hopefully, in some way. Likewise, even though I’m moving forward in time, I’m aging, I’m dying—at the same time, I’m still that 4-year-old boy from back there as well.

Nguyen during his childhood in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, around 1976. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

SB: Remind me, how long were you with the sponsor family?

VTN: Just a few months.

SB: Just a few.

VTN: It felt like a long time when you’re 4 years old.

SB: Yeah, of course. I mean, you’re at that age, and it’s like, where’s Mom? Where’s Dad? Wild.

In 1978, your family moved from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to San Jose. Obviously quite a shift from central Pennsylvania to California. But looking back on it now, what are some instances or moments that come to mind for you when you think about your “San Jose time”?

Nguyen as a teenager in San Jose in 1987. (Courtesy Viet Thanh Nguyen)

VTN: Well, back then, the only thing people knew about San Jose was the song “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?” I just remember it as a time that was really wonderful in some ways because I just spent all my time in the library reading books, escaping via stories. That was a wonderful time, where I lost track of time. I just had so much time to read books that I don’t have anymore. So I think of it in a very utopian sense, but—

SB: You write that you were “kidnapped by literature.” [Laughter]

VTN: Kidnapped by literature, right, exactly. And my poor parents, they were complicit in the kidnapping because I think their way of babysitting was well, we’re just going to drop them off at the library and this is what they did. They would drop me off Saturday morning at the library before the doors even opened. I’d just be hanging out with a bunch of strangers outside. That wasn’t even the worst of it because it was what was inside the library that was dangerous. My parents never realized that. They didn’t think books were dangerous but I was reading all kinds of things that really messed me up.

SB: Yeah, tell me some of the dangerous books that you discovered.

Cover of Portnoy's Complaint (1969) by Philip Roth. (Courtesy Vintage)

VTN: The most relevant for our purposes was Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth, which in the weird sense of time, he published that book in 1968, I probably read it in 1983—only twenty-five years! To me, it seemed like an ancient text, but it was only a twenty-five-year-old book. The only thing I remember from that book was Alex Portnoy, this Jewish-American adolescent who was so horny that he basically masturbated with anything he could get his hands on, culminating in a slab of liver from the family fridge, which—he did his business, put it back in. And then his mom cooked it later that night for dinner. [Laughs]

Then I thought, Gross, who eats liver for dinner? It was like, we do, as Vietnamese refugees. So I totally felt this sense of resonance with Alex Portnoy and his Jewish-American experience overshadowed by the horrible past and everything like that, which I felt was in so many ways parallel to the Vietnamese refugee experience.

And then of course, I would never forget that moment, and I would pay homage to Philip Roth and Alex Portnoy in an episode in the novel The Sympathizer, which if you watch the TV series, episode two, Park Chan-wook goes all the way.

SB: He sure does.

VTN: He puts that squid masturbation moment in there.

SB: Don’t eat it! Don’t eat it!

VTN: Yeah, don’t eat it.

[Laughter]

VTN: That was a magical time in San Jose in the library. But it was magical because the flip side of it was, the reason why I was there was because of this horribly difficult life my parents were leading, which they were trying to shelter me from and which I was trying to close my eyes to. But I could still see it anyway, their economic and personal struggle, which was so arduous for them. That’s what I remember about this decade in San Jose from 1978 until 1988, when I graduated from high school, and I just could not wait to leave San Jose. That ten-year time span was that emotionally radioactive core of myself and memory that I think has still shaped me as a writer.

SB: I must mention your first job, too, at the hilariously named, at least in this context, Great America amusement park. [Laughs] You’ve written, “To be an American…. is to be squeezed in the vise between these binaries of memorialization and murder.” And when I think about this quote in the context of your job at the Great America amusement park, it’s almost too good. America as an amusement park in general is already a very good metaphor.

VTN: And the ironies abound because that whole amusement park—it was all full of roller-coasters and things like that—but all the themes were around American history. So as we talk about time, here’s this manufacturing of nostalgia through a handful of very flat tropes that people can consume while they’re riding roller-coasters. I worked in an area of the park called Yankee Harbor, so that’s all that needs to be said. [Laughter] And our uniform in Yankee Harbor was a pirate uniform or sailor uniform, I don’t know what it was, but a black bell-bottom pants, a white shirt with a ruffled collar and a tricorn hat.

Most of us were young people of color, Filipinos, Vietnamese, this kind of thing. And here we were manning Yankee Harbor. Yeah, the ironies were just fabulous. And of course, the whole culmination of that is most of us got fired because we were breaking all the rules, riding these rides when we weren’t supposed to in our uniforms, but riding these rides without our safety gear on because we were 16 or 17 and just basically idiots. [Laughter]

This one guy— I manned the ride called the Tidal Wave, which was a roller-coaster that goes into a big loop. So there’s good reason why you want to have your safety restraints on. And this kid got in there without the lap bar on, so he had no restraints. I was like, “What are you doing?” He gets fired into the loop. He comes back and he jumps out and without having fallen into his death, and he says, “Centrifugal gravity,” “Centrifugal force,” whatever. I was like, Oh, okay, we have a living demonstration of physics taking place here. I’m going to do that, too. I’ve never been so brave and so stupid in my entire life.

SB: [Laughs] You made this choice in the book to title-case “AMERICA” and include a trademark logo after it. You also redacted in black all mentions of the 45th president. Could you talk about these two particular editorial choices?

“When people say ‘America,’ there’s this timelessness—it’s a mythology.”

VTN: When we say the word “America,” I think time is implicit because, well, what’s really implicit is timelessness—“America” when Americans say it. But people all over the world as well, maybe not in Latin and Central America, but people outside of that area, when people say “America,” there’s this timelessness—it’s a mythology, this idea of America and all of the various kinds of implications that we’re all very, very familiar with. I wanted to disrupt that easy sense of mythology and timelessness that hangs on to that word.

Of course, the book talks about that history in various ways, but just at the level of the word, I wanted to stop readers from coming across that word and just sliding right over it as we normally do. That’s why it’s capitalized. That’s why there’s a trademark. So people have to pause and say, “Well, why? Why is it capitalized? Why is it a trademark?” And of course, for me, America is the ultimate embodiment of capitalism. There’s also other things like—

SB: [Says in gruff voice]’merica. [Laughs]

VTN: Yeah, ’merica. But it’s all around this idea that the New World was the genesis of a new world order based upon globalizing capitalism. And it didn’t start in America, but it certainly accelerated there. And we’re still dealing with the consequences some four hundred and fifty years after the first English settlers came to these shores. I think of Donald Trump as a part of that history. I think of Obama as a part of that history too. And both of them come up in the book as symbolic faces in opposition to each other. America doesn’t have just one face; it has two faces, just like me, and it’s Donald Trump and Barack Obama in recent history.

Of course, our ideological divides and divisions in this country are very binary at this moment and these two presidents have come to symbolize this binary. And each side looks at the other in sheer shock and surprise, like “How are you an American?” To me, that division goes back in time to the very origins of “AMERICA™,” because on the one hand, I think it’s true that this is a country of freedom and democracy. It’s given me the opportunity to be a writer, which I could not have pursued in Vietnam in the way that I do now. Freedom and democracy for some. At the same time, it’s also a country that wouldn’t have been possible without genocide, colonization, enslavement, warfare, slavery.

SB: And as you point out, the pilgrims were the original boat people.

VTN: They were the original boat people. They were just lucky the Indigenous peoples didn’t have cameras to take pictures of them because they were probably a pretty nasty looking bunch getting off of the little boats that they were in. [Laughter] But yeah, Donald Trump was in there because he is as American as they come, from the very origins of the country. And he embodies that America that is so self-reflexive, that we don’t even think twice about it. But so does Barack Obama. Those two mythologies operate simultaneously.

The reason I redacted Donald Trump’s name, besides just maybe being petty, is because I was also thinking about how redaction is, to me, symbolic of self-censorship and the processes of memory. We talked about how I redacted my own memory, but this country redacts its own memory. It’s not to say that other countries don’t—every country does, but I’m an American talking about the United States. The redaction becomes symbolic because I was also writing at a time when we have redacted documents that come out all the time about the various kinds of things that we’re doing that are arguably either very American or very un-American, depending on your idea of what America is, what we do in Guantanamo [Bay], what we have done in our wars overseas and so on. These official documents, we have them because we’re a country of freedom of the press, and yet we redact all the things that would be quite bad for our image as Americans globally, but also quite bad for our self-image to ourselves as Americans.

SB: I love when artists and writers do this. Reginald Dwayne Betts, who’s been a guest on this show, he has a series of redaction poems that are brilliant, relating to America’s carceral system. Jenny Holzer, also, the artist, she famously has done redaction artworks, and I think it’s really effective. Again, it’s another moment similar to the “AMERICA™.” It does cause the reader to pause and reflect and say, “Oh.” And a redaction is also a void, so there’s this sort of void element, what’s not there, what’s not shown.

I want to move forward a little bit to beyond your youth, to your Berkeley years, which you did mention briefly. But we didn’t get to mention Maxine Hong Kingston, this incredible novelist whom you got to study under and who wrote this note to you at the end of your course, basically encouraging you to seek counseling at the university counseling center. But that wasn’t all she wrote in that note. And there’s something I particularly loved, which is she wrote, “Questions are creative and dangerous. To ask a question is to be open to change.” And I feel like those words, when I think about your work and what you’ve been able to do with your thinking and your seeing and your being and your writing, it connects so much to that notion of questioning. You’re nodding, but how do you see it?

VTN: Absolutely. Maxine, a wise and wonderful writer and woman and teacher, got me. She saw me. She saw me falling asleep in her class every single day [laughs]; that’s why she thought I was alienated and depressed and needed help. I of course did not think I was alienated and depressed and in need of help. I thought I was perfectly self-functioning and all of that. But there were warning signs. I started dating a young woman who would become my wife, and I told her, “Oh, I’m pretty well-adjusted,” and she said, ”No, you’re not.” [Laughs] So she was right, as always.

SB: [Laughs]

“To become an adult is partly about absorbing the rules of one’s society so deeply that you can’t see the hypocrisy that you accept as being normal.”

VTN: But it would take me becoming a writer, instead of seeking counseling, for me to try to figure out what was wrong with me. And part of what was wrong with me, and Maxine saw it right away, was that I was afraid to give of myself in my writing and also in my interactions with my fellow students and other human beings. And part of giving of oneself is to ask questions, ask questions of oneself, to interrogate oneself, but also ask questions of other people. I think we’ve all had that experience of talking to someone who only talks about themself and they never ask you questions. It’s a bad sign.

I’ve been fortunate to learn from my teachers, both in an intellectual sense, but also in a personal and emotional sense as well. So if we talk about time, I look back upon my 19-year-old self with great empathy. And there’s a part of him that I want to retain, which is the anger, the passion, the conviction. We’re at a moment where college students around the country are being arrested, beaten by police, and so on. Their futures are being threatened because they believe in something. Whether or not you agree with them, they believe in something, and they’re really putting their bodies and their lives on the line.

I was like that when I was 19. I don’t want to be 19 anymore because I think I was not a very good human being. I’ve spent thirty-plus years trying to become a better human being through things like writing, interrogating myself, trying to figure out how to better access and deal with my emotions. But what was so important about remembering myself at that time was to try to retain the core of conviction. Because yes, adults can always say, Well, those kids don’t understand the complexities of this and that. It may be true but what they do understand is that there are principles and they can detect hypocrisy.

To become an adult is partly about absorbing the rules of one’s society so deeply that you can’t see the hypocrisy that you accept as being normal. These younger people, they can see that, and I could see that. I admire myself at that time just for that, just as I admire the students of today for doing what students should always be doing, which is reminding the adults of the absurdities, the hypocrisies, the oversights, the contradictions of our society that adults have learned to accept and students have not yet learned to accept.

SB: Great transition because I wanted to talk about youth, and particularly these two children’s books that you’ve worked on. This is a total left turn here [laughs], but it is connected. I mean, there’s a sort of playfulness, and maybe we’ll touch on this, a humor to your work, even though there’s so much serious stuff at play. One of these books is Chicken of the Sea, which originated in the mind of your son, Ellison, and the second, Simone, comes out, I think if my dates are right, six days from today. I imagine these kinds of projects are really generative for you in that way. I can imagine that wading through the grief and trauma and memory stuff is tough, and having an outlet like this seems like a fun way out. Is that a fair assessment?

Cover of Chicken of the Sea (2023) by Viet Thanh Nguyen and his son, Ellison Nguyen. (Courtesy McSweeney’s Publishing)

VTN: Oh, absolutely. Not to idealize childhood, but if one has a good childhood, part of what happens, I think, is that you have access to freedom and playfulness, and hopefully your parents and your environment are encouraging all of that. That’s something that I think we, most of us as adults, have lost—that sense of a very different sense of time. Because when you’re a child, everything is infinite. When you’re an adult, your sense of time has closed down because you’re counting the years until death. But when you’re 4 or 5, hopefully you’re not thinking about that very much, and you don’t have the rules and the boundaries yet that will be imposed on you and that you will internalize. As I look at my children, I experience time through them. I experience trying to remember who I was when I was their age at any given moment, and then, I think, try to understand that their sense of time is vastly different than my sense of time, and that produces a different approach to the world.

I’m also trying not to idealize fatherhood or parenting. [Laughs] A good number of people should not be parents, okay, but for those of us for whom it’s been a positive experience and for our children, it’s positive in one way because it’s reminded me to be playful. It’s reminded me that rules are meant to be broken. That’s really important for politics and for creativity. We talked about the student protesters. I think besides the very seriousness of what they’re doing, they’re also being playful. And I think that’s what’s also annoying to adults: How dare you set up camps in the middle of the campus?

SB: It’s provocative.

“Parenting has reminded me to be playful. It’s reminded me that rules are meant to be broken.”

VTN: Yeah, right. So it is a sense of theater and play and spectacle in addition to very serious politics at the same time and that’s what makes it fun. I’ve been to my university’s encampment. It seems like fun to me! [Laughs] Until the cops are called in and start arresting people. And that’s like adults coming in, saying, “No, you can’t do this. How dare you break the rules?” For creativity, it’s really important because in the world of adult writing, there are all these conventions that you know you’re supposed to follow, both the conventions of the form, but also the conventions of the world in which writers work. You want to win that prize, you want to get that agent, you want to go to that dinner. You have to conform in various ways, whatever the world of publishing and writing is.

Kids don’t care about that. They don’t care about that in terms of their rewards, and they don’t care about that in terms of the books that they’re reading or the art that they’re looking at. I’ve learned a lot from being a father to these kids in terms of trying to capture some of that creativity and unleash it in my own writing. Because ultimately, in the end, writing is not just art with a capital A—writing is play. For me at least, it’s a painful but also powerful way to try to make my way in the world and try to make a living is through this kind of paradox of serious playfulness.

Cover of Simone (2024) by Viet Thanh Nguyen. (Courtesy Minerva)

SB: Your children also connect to art across time because of their names; Ellison, named after Ralph Ellison, and Simone, after Nina Simone.

VTN: And Simone de Beauvoir. Names are an opportunity, a challenge, a burden, and so on. My name, Viet Thanh Nguyen, or Nguyễn Thanh Việt in the original, it’s as Vietnamese a name as you can get [laughs], because the surname Nguyen is shared by about forty million Vietnamese people, I think. And Viet the first name, it’s a very common name. It’s like being called George Washington or John Smith, because Viet is the name of the people, and Nguyen is the name of this gigantic part of the people.

So I’ve always felt that burden of my name, so much so that when I became a citizen, my parents said, “Do you want to change your name?” And I grew up in a household where I was told I was 100 percent Vietnamese and then here are my parents becoming Joseph and Linda.

SB: [Laughs]

VTN: I was like, what? What’s going on? But they were so effective in teaching me that I couldn’t change my name. So I understand the burden and the opportunity of naming. With my own children, they have Vietnamese middle names as well, but I wanted them to have names that would be opportunities and challenges for them once they understood who these people were that they were named after. Hopefully they won’t resent me for giving them such explicitly symbolic names. Hopefully they’ll see these names as an invitation to participate in history.

SB: Final question, because we haven’t talked about humor or laughter so much yet [laughs], I want to end on that. There are these core components to your work and lines in The Sympathizer that made me chuckle. It’s a war novel after all. But wartime is in and of itself an absurdity. And there should be somewhat, I think, an opportunity to laugh at the absurdity of it. As you write in A Man of Two Faces, “Laughter could help the Vietnamese and the Amercans recognize not only the idealism and valor of their holy revolutions but the inevitable absurdity and hypocrisy because nothing is so holy that the human species will not fuck it up.”

VTN: I hope that’s truth. I think about the fact that if we look back at World War II, for example, just from the American perspective, within a decade, Hollywood was making comedies about World War II, this horrible experience. And yet we had Operation Petticoat. And I don’t know, I grew up watching I Was a Male War Bride. I grew up watching these kinds of comedies, and then of course, we had Catch 22, which is a more serious comedy about World War II. For me, I read very serious books and watched very serious movies about war, but also watched these comedies and these satires. I think they’re all important registers for us to cope with this experience of war, because like every other human experience, war has all the emotional registers.

“Jokes are a form of truth-telling.”

Whether we’re talking about something in the past, like World War II, with a finite time span, or whether we’re talking about our reality as Americans today, where we’re, I think, still living through forever war, as far as I can tell, perpetual war—it’s a condition that structures our daily lives as Americans, whether we are aware of it or not. It’s not just one emotional register. It’s many emotional registers that war operates on. And humor is really important, because jokes not only help us survive by making us laugh, obviously, but jokes are a form of truth-telling. And I’ve actually learned quite a bit, not just from reading Joseph Heller and Catch 22, but also watching stand-up comedians, because the good stand-up comedians have a sense of timing as they deliver the joke, but also a sense of timing in terms of knowing what time they live in and what function their jokes can serve.

So in A Man of Two Faces, I quote Richard Pryor in 1975 talking about the arrival of these Vietnamese people as the new, you-know-what to take the place on the American firing line instead of African Americans. That’s a very painful joke for Richard Pryor to deliver and it has so much truth in it and so much timing in it. I can’t even replicate the joke for obvious reasons, but also because of the impeccable sense of timing that Pryor has to deliver that joke in that way, in that time. I’ve tried to learn a lot from comedians and stand-up comedians who are not just funny, but provocatively funny because of their timing. It’s fun to watch.

SB: Yeah, I just watched the HBO special with Ramy [Youssef] and it’s so of this moment and so right now in a way that I haven’t seen a comedian do in a while.

VTN: You have to have the courage to have the time. I mean, he didn’t have to make these jokes, but now is the time. Now is his time. I’m looking forward to meeting him. He reached out to me.

SB: Oh, great.

VTN: I was like, “Hey, we’re back in the world of Hollywood now.” So you can do both. You can be entertaining and you can be provocative at the same time.

SB: Mm-hmm. I’ve quoted you a ton today, and I actually don’t…. Sometimes I’ll do quite a few quotes in an interview, but I feel like I’ve been quoting you with every question. There’s one quote I wanted to leave our listeners with that I hope will linger in their minds and it is, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Thanks, Viet.

VTN: Thanks so much, Spencer.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on May 1, 2024. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo based on a photograph by Hopper Stone.