Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Tom Dixon.

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Tom. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

TOM DIXON: Nice to be here.

SB: I thought we’d start on the subject of longevity.

TD: [Laughs]

SB: This is perhaps central-most to your work or even, I would say, a desire of everything you do. Could you share a bit about how you think about and define longevity?

TD: Well, in terms of product, it’s become more and more important as the sustainability question becomes urgent and prominent and every company has to think about it. I think there’s an advantage to being in domestic or furniture products, which is that you just can’t consume in a throwaway mentality. It’s got the benefit of being a fairly slow sector anyway, whether that’s in retail or consumption.

I’m now old enough—if you’re talking about longevity—to have seen my stuff bounce back. That might be on eBay, it might be at a car boot sale, but I’ve even seen it in antique shops or in auction houses.

So, trying to understand the value that comes with intertemporal objects and thinking about how people, or even in fashion cycles, how things are quite cyclical and come back. I mean we’ve seen Midcentury Modern come back in a huge way, then being superseded by postmodernism. A second time round. Modernism came round again in the eighties and will be back.

“I think if you do your job correctly, you’ll see things have a second, third, or fourth life.”

So I think if you do your job correctly, you’ll see things have a second, third, or fourth life. The best example I always use is my great-grandmother’s writing desk, which she bought as an antique, which must be around Louis XVI and presumably has served ten generations. It’s actually quite a good laptop desk now.

SB: I did want to bring that up. I mean, it’s rare that we think about furniture in terms of centuries.

TD: Mm-hmm.

SB: Is that a desire you have with objects you make?

TD: Well, I spent a lot of time in museums as a kid. I think it’s interesting to see how things fall in and out of fashion, and then the things that survive, right, whether that’s in style or robustness or build quality or even materials, which I’m very interested in and which things actually might improve with age as well, which is obviously a thing which is quite hard to define. But I’ve forgotten what your question is.

Dixon’s Flame-Cut chair. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

SB: Do you want the objects you make to last centuries or—

TD: Oh centuries? Well, I mean that would be amazing, right? And I’ve toyed with a thousand-year guarantee. It’s very hard to convince anybody in business to underpin that.

SB: Right, your Flame-Cut furniture.

TD: The Flame-Cut furniture was a project which came from working in a British castle that had been burnt down three times over a thousand years. So the idea came from this idea that the architecture was surviving, but the contents had vanished, and that even the wall finishes or the floors had gone, but the building still stood. So I just thought, well how could you make a set of furniture that would survive alongside the building? And to that end, I just use shipping steel, and obviously if you left it outside it might rust over a thousand years, but indoors it would definitely survive a house fire or a civil war, which is what this castle was subjected to over a thousand years.

SB: When it comes to design and production, on the subject of time, you’ve said, “The best thing is not to race toward instant gratification, which I’ve been guilty of, or trying to go faster the whole time, but maybe slow down completely and do things which may take three or four or eight years to mature and sell them in a small or more select way.” Do you see a future where this sort of slowed-down design process can exist? Even in the world of A.I. and machine making…. Do you see it though there could be a stronger desire for that kind of thing?

TD: There’s a lot of threads to that question. It was not the design process in that project which was taking three or four years; it was the manufacturing process.

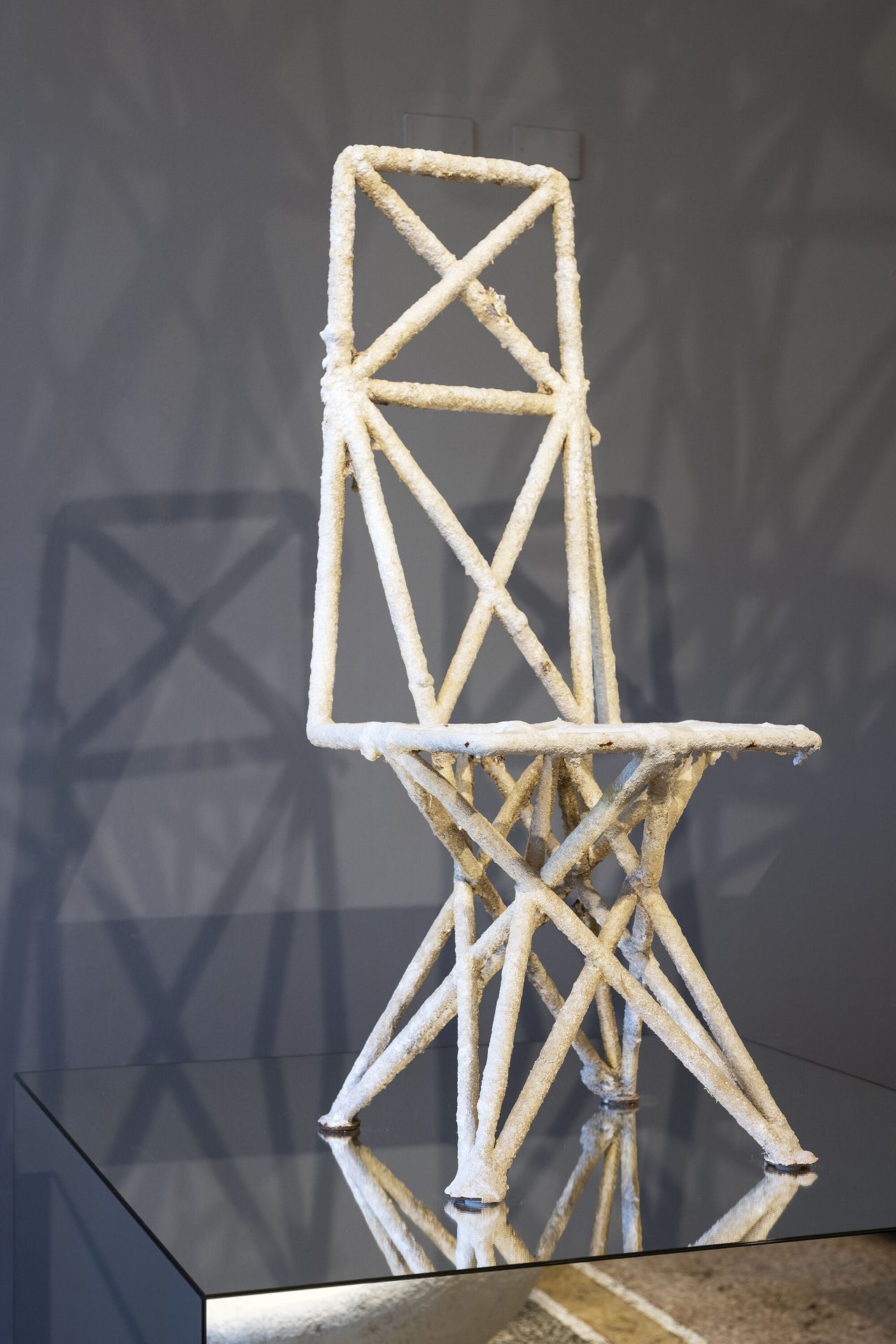

So this is a project I’m still noodling with, which is [an] underwater factory. And it requires a sort of electroplating process to accumulate minerals on a metal framework, which takes two, three or four years according to how thick you want the deposit to be on the furniture. So a means of making reinforced concrete using the minerals in seawater. So the design is whatever the design is, but the manufacturing process takes three or four years.

“A long-term view is something that’s vanished from corporations, but in farming or in other sectors, it’s intrinsic.”

I’ve shifted from thinking that it might be a good idea for manufacturing because it just isn’t. I mean, nobody could really afford to buy things that take four or five years to make. But having said that, some of the raw materials in your furniture take a hundred years to make. Wood, for instance, is quite obviously something where you have to have a long-term view. And I’ve been inspired more recently by the people doing cork products, which also takes seven years between cork harvest and twenty-five years to grow the plantation. So people that are thinking of working in those sectors have to have a long-term view. And that’s something that’s vanished from corporations, for sure—the quarterly report, the annual targets—but in farming or in other sectors, it’s intrinsic. So I think there needs to be a readjustment. Whether our fast-paced consumption habits allow for that or short-term profit goals allow for that is the difficult question.

But these subjects are getting much higher on the agenda right now. I think a combination of some of the things that you’re having to do in sustainability, combined with how you manufacture things, might be an answer. And specifically, to go back to this underwater factory idea is that you could, in principle, do something which had two, three, or four outputs rather than just a single one. So you make frameworks that go into the water, they serve to regenerate coral, they serve potentially as a tourist destination for locals to make money out of tourism, as a dive center. Could also serve to manufacture products—I imagine it’s a bit like a fruit-in-an-orchard kind of thing. And as rising sea levels start to threaten coastal areas, it might serve to reduce beach erosion, for instance, which is becoming increasingly a problem with extreme weather events.

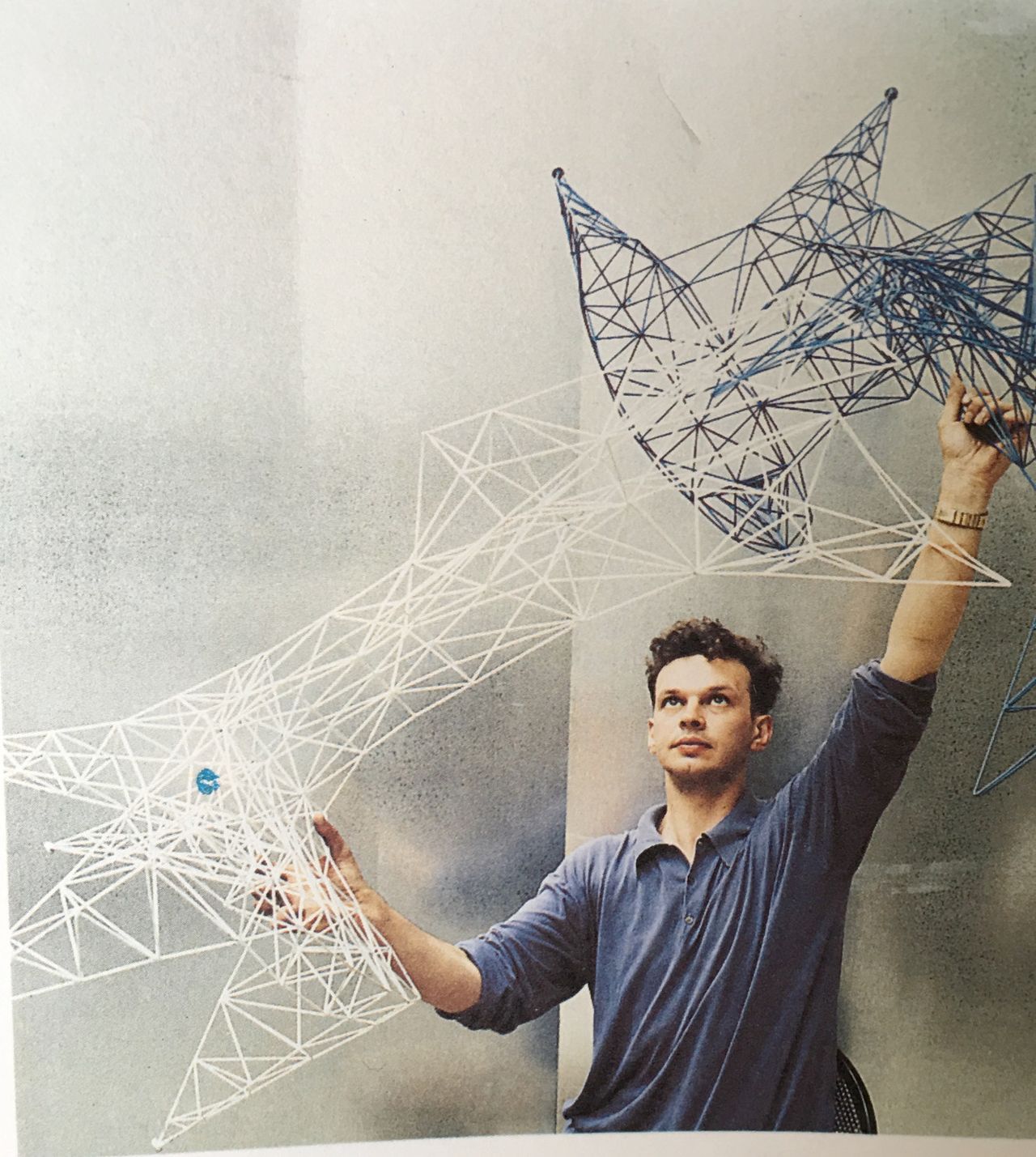

A piece from Dixon’s ongoing Underwater Factory Furniture collection. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

SB: When did this underwater idea begin? I was reading that in 2008, at the Design Miami fair, you had brought these works to Miami, but there was a recession, there was trouble, you didn’t want to have the trouble of getting them home. Is that where it began?

TD: That was the start of the thinking about underwater and the idea that really these were incredibly monumental and heavy pieces of kit. There was nowhere better to show them than Miami and rather than store them in the warehouse and ship them back to the U.K., tipping them over the edge into the bay, because I knew somebody with a jetty, Craig Robins [the guest on Ep. 28 of Time Sensitive], who’d actually created Design Miami. It was possible just to have them in a place where they might also acquire some patina and some authority over time as well. I mean, we’re talking about timelessness here and about how things might improve with age. There’s something about the uniqueness of an object which has been sunk in the water, which is unreproducible with conventional finishing techniques, the way that rust and barnacles….

So we tipped them in and we retrieved them a couple of years later, and still didn’t sell them. So the recession hadn’t gone away. There was a proper market crash. I think the banks collapsed, whatever. So nobody was buying fancy furniture and certainly not interested in the thousand-year guarantee. But the thing came out and what was quite nice is that we showed it again in Design Miami, but it smelt of fish, basically. It smelt of seaweed and barnacles. It acquired not so much patina but a stink.

[Laughter]

SB: And you kept the buoy on.

“There’s something about the uniqueness of an object which has been sunk in the water, which is unreproducible with conventional finishing techniques.”

TD: Yeah, there was a buoy tied to things so that we could retrieve the object and that became part of the installation. But we still have it for sale, by the way, for any of you long-term customers out there.

SB: [Laughs] And these accretion chairs and this underwater project, tell me about how that works. What’s the process? I guess you have at least some of these chairs underwater in The Bahamas or….?

TD: No, so you were asking me about where the idea came from. It was developed by a 1970s visionary scientist and architect. He was called Wolf Hilbertz, and he decided that he was going to grow cities underwater and float them to the surface. Of course, there was a big ecological movement in the seventies and you wonder why it vanished and then had to reemerge, because there was a lot of really interesting work going on at that time.

View of a piece from Dixon’s ongoing Underwater Factory Furniture collection. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

Anyway, he wasn’t able to grow the cities underwater, but he found a way of making A, this natural concrete, which has been trademarked as Biorock, and then B, that it actually regenerated broken coral. So you can graft or just tie on bits of broken coral onto these structures and they themselves, once you’ve charged the metal structures with a tiny voltage of electricity, usually taken from a solar panel, the coral will grow three, four, five times faster than it might in natural circumstances. And then it also encourages other forms of sea life, so mussels or oysters or lobsters. There’s something about the electrical charge and the metal framework, which seems to encourage not just the electroplating of the structures with the minerals in the seawater, but also a vast variety of sea life.

So no, I don’t have any in the Bahamas anymore. We’re working with some wreckers—effectively, some pirates—out there, and the Bahamas was great, but we wanted a larger-scale project and I think we might have found one in Australia. Obviously Australia, [is a] great place where they’re very concerned about their coastal regions where there’s a pressing need to look into coral regeneration. The only problem there is man-eating crocodiles. Well, sharks as well, but sharks are more a fear thing than the reality, whereas crocodiles are very, very real. They like eating mammals.

SB: I’m sensing a Two Thousand Seats Under the Sea project here. [Laughs]

TD: Yeah. No, we’re just preparing to dunk some more structures in the sea and see how it reacts in a different time zone and in a different marine environment. So northern Australia there.

SB: It’s interesting to think of furniture as potentially an ecological fix in some ways or contributing to a larger ecological movement or conversation.

TD: Well, everything has to start referring back to that very extremely pressing issue, which is how we deal with consumption and our very bad habits that we’ve got into as a race.

SB: I wanted to talk about a few more materials with you. You’ve done a lot of work in cast iron, which is another fascinating material from a manufacturing perspective—not always something associated directly with furniture. How is it that you go about picking or obsessing over particular raw materials? And I guess let’s start with cast iron. Why did you hone in on that one?

“Everything has to start referring back to that very extremely pressing issue, which is how we deal with consumption and our very bad habits.”

TD: I think we’d used the series of tropes about British industry as a means of giving ourselves a…. It was something I was always interested in anyway, and the Industrial Revolution, just the general aesthetics of how we became industrialized and it seemed like a quite good backdrop to creating the label that we did maybe twenty years ago. And cast iron was intrinsic to the Industrial Revolution—really powered quite a lot of the bridges and the engines that made it all possible. And aesthetically, it’s effectively a molded material so you can get quite a lot of decoration and detail into it. And then, more recently, where[as] pattern-making for cast iron used to be a very skilled and increasingly dying out profession, now you can create your models and your patterns on the rapid prototyping machines.

So you’re back in this thing, it’s actually a relatively primitive way of working metal that’s available everywhere. In Birmingham, we make some objects; we make some in India, for different reasons. For China, Poland, depending on the finish that we want or what we’re matching it with. So it’s a universally available material and it’s, again, a material that has an immensely long life when treated properly. And you’re still seeing in the U.K., in New York, manhole covers, fire hydrants, bridges that are all made with this wonder material, which is both very primitive to work and very sophisticated. So that’s why I like it. And there’s a weight to it, which I’m interested in the ideas of lightness and heavyweight-ness as well.

SB: I really enjoyed the piggy bank you made out of cast iron.

[Laughter]

TD: Yeah, not my greatest commercial moment, but yeah.

SB: Cast iron–shaped factory, for the listeners who don’t know this particular piece.

TD: Yeah, money boxes have kind of gone out of fashion, haven’t they? I mean you need to make one which has got a digital—

SB: Where you can store your—

TD: Crypto.

SB: Yeah, exactly.

TD: Okay, good idea. We’re coming up with product ideas right here and right now.

SB: [Laughs] Talk to Ledger. You’ve also worked, of course, with copper a lot—you’re quite famous for that—glass, felt, stone, and marble. How do you think about materials as you use them across time, both from the raw-material perspective but also the end product and how that material stands the test of time?

TD: Well, I think the encounter with materials, as I kind of post-rationalize my interest in design, really came from the ceramics department at my secondary school—in America you’d call that, what? I don’t know, I was basically 14. I was in a school which was failing academically. I was not that interested in lessons. I was quite a bookish boy, but I found refuge in an amazing ceramics department that we had at that school and just discovered the joys of transforming this mucky, muddy, universally available material into desirable objects.

“I was selling cannabis pipes to my peers, age 15, at school. That thing of understanding the value of design into small industry, into commerce, is still with me today.”

Thinking about it actually now, my mother gave me a box of my tools that she’d been storing since that time. And it was a series of hash pipes that I’d been making at school and indulging not just in making but in commerce as well. So I was selling cannabis pipes to my peers, age 15, at school. That thing of understanding the value of design into small industry, into commerce, is still with me today. So I can’t believe that I was actually doing that at that age and using the available facilities to do that.

But the great thing about clay and then going back to materials just in general is, that’s a departure point for every design. I think the contemporary designer is faced with lots of possibilities on the computer, where you can press a button and suddenly something goes transparent and it’s made out of glass instead of cast iron. The reality of materials is that they’re not as smart as the computer and you have to really know them to be a reasonable designer if you are interested in those things going into production rather than just inhabiting a virtual world. So the materials at the departure point, the processing of them as materials is the reality of what you can do with them.

My interest in design starts off with the clay and then mutates into welding, which is obviously a very quick and flexible way of making quite solid structures. So somewhere between the raw material and the way that you convert it, whether that’s an industrial technique or a craft technique, lies all of these unbelievable series of possibilities. My method of designing isn’t really conventional in the way that an industrial designer might be. The approach is more sculpture, because I like to make the thing full-size out of as close to the real materials as possible from the get-go. And I like to understand how you manipulate those machines. So even if I’m not a weaver or a glassblower, I’ll have spoken to the people that actually craft those things or the engineers that work on them and try and understand what I can do that’s different from what’s already there.

So materials do become specific obsessions, and at the moment we’re deep into cork and aluminum for a variety of reasons. But plastic is still really interesting despite it having very negative connotations at the moment. And glass is still fascinating, as is clay. And I’m never going to get away from steel or copper, I don’t think either, because it’s still, in my view, full of potential, unresolved potential in my eyes.

SB: Do you view yourself in some ways as an alchemist?

The Cork Round dining table designed by Dixon. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

TD: Well, I use that as a kind of analogy for this idea that, unlike a lot of designers, because I didn’t do design theoretically, I didn’t study at school for four years. And the only way I became a designer was by people actually buying the objects I was tinkering with. So I think that transactional thing is kind of interesting because I don’t think I’d have had the confidence in my own ideas if other people hadn’t endorsed them with the cash. For a lot of designers, the money side of things is a dirty word, or you’re just involved in the service industry of coming up with the idea and you don’t really think so much about the commerce. For me, it was almost the motor which made me believe that I had an ability to make things that people would desire. I’ve never divided out the commerce and the design in the way that a lot of other people do artificially by going to college. For me, that endorsement is still a thrill. I can’t believe that people will still buy things that were, a few months ago, just an idea in my head. And that’s a great way of making a living. It’s more like being a baker or something. You see the thing all the way from the raw material to somebody’s home. And that’s a quite complicated journey sometimes, but we’re involved in every part of it.

SB: How have you seen the speed shift of what you make from the early days, which were much more, I would say, raw or crude designs than some of the more industrially manufactured designs of more recent decades?

TD: Well, it’s interesting that I’ve managed to have really quite a broad series of experiences in design and manufacturing and commerce as well. So making things with my own hands, not really as a craftsman because I can’t claim to be a good craftsman. Running my own factory with juniors that I taught how to do metalwork and moving on to working for the Italians that were doing really luxury goods. Then going back into proper commerce on the High Street level, so much more affordable things. Experimenting with giving things away for free, so going even cheaper than the cheap, going completely free. Trying to mimic some of the internet companies that give away their core service and then charging for it through advertising. So I’ve gone from free to really expensive and mass production to craft.

At the end of it all, I don’t actually see as much distinction as a lot of other people do in these different levels of pricing, or luxury versus mass consumption, or even craft versus engineering. Obviously, if you make things in smaller quantities, they’re going to be more expensive. But I’m fascinated in things that we do in hundreds of thousands and I’m still fascinated in the unique object. They all have their legitimacy and their different characteristics and their different values according to how they’re made, what they’re made from and who’s supposed to be buying them, in what quantities. So I don’t actually separate out the ideas in that. I’ve just managed to have a lot more exposure to the different levels of perceived value than a lot of people in my sector, I guess.

“It takes quite a long time to shift people’s mindsets about what’s valuable or what’s not.”

SB: Yeah, I think it’s really interesting. It’s rare to talk with somebody about this, so I wanted to ask it: How do you think about how society places certain values on materials? Because you’re looking at it from a very designer-maker point of view, but once these things are out in the world, there’s a certain value system placed on material.

TD: Yeah, and I think also perceptions are shifting in terms of the value of different things or the non-value of different things. And it takes quite a long time to shift people’s mindsets about what’s valuable or what’s not. Our big struggle at the moment is trying to convince people that recycled materials or sustainable materials are worth the money that they cost. So recycled material typically performs less well, looks cheaper, and is more expensive—because you’ve had to recycle it—than virgin material. And trying to convince people of the value of that is a big communication exercise which designers increasingly have to become good at.

The Cork dining table designed by Dixon. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

Same with cork. Cork is a wonder material. It’s carbon-positive, it’s really beautiful and tactile, but people associate it with a throwaway product, which is basically the cork in your bottle that you throw away. So convincing people that a softer, lighter, throwaway material has got value in something that is permanent is also a mindshift as well. So I think we’re dabbling with people’s perceptions on the value of different materialities and the rest of it. A big part of the job is trying to explain these things in a way which makes them appealing or make them appealing.

The latest battle which has probably been won has been, for instance, with LEDs. So you’ve got to remember that it sort of happened in the opposite direction, that LEDs fifteen years ago were the light that nobody wanted. It was too expensive, it was too blue as the light, it flickered. Nobody wanted that stuff because it was…. So a combination of government legislation, which I think is underestimated in terms of the need for that, to challenge consumer behavior. The massive leap forward in engineering to make things at a price, so big scale becomes important in that. And then designers working to beautify the things and make them acceptable for consumption. These are the three things that will allow the value to rise, the perceived value to rise. And the prices default to a point where things are affordable for consumption.

The LED thing’s been an interesting recent topic, which is of great interest to me. The shift from electrical lighting to electronic lighting is a moment in time where things changed, just like when it went from gas to electricity. And it’s kind of underestimated as an amazing shift which allows designers to come up with new ideas.

SB: And lighting’s been of course such a core of your offering. I imagine this has been really fascinating to see that shift in the culture happen.

“We’re living in a moment which is revolutionary in terms of the tools that we can use as designers. And it’s only just starting.”

TD: Yeah, because as a designer you’re always looking back and thinking, Oh, my God, if I’d been around in the 1920s and been part of that amazing Bauhaus scene where there was— Or, in the sixties, when there was all the amazing possibilities in terms of the new plastics and the materials from the war effort and the change in people’s behaviors. You can get nostalgic, and actually, we’re living in a moment which is revolutionary in terms of the tools that we can use as designers, and it’s only just starting.

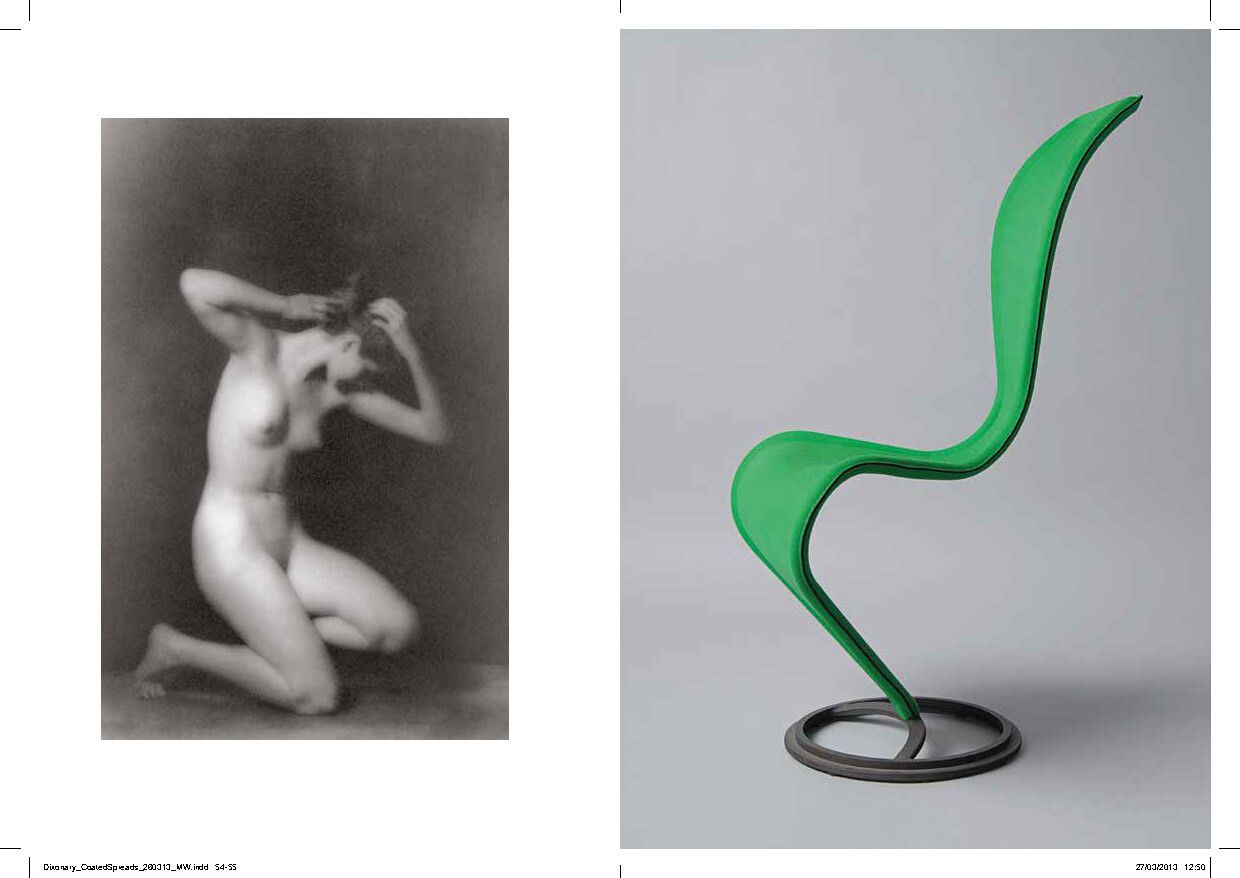

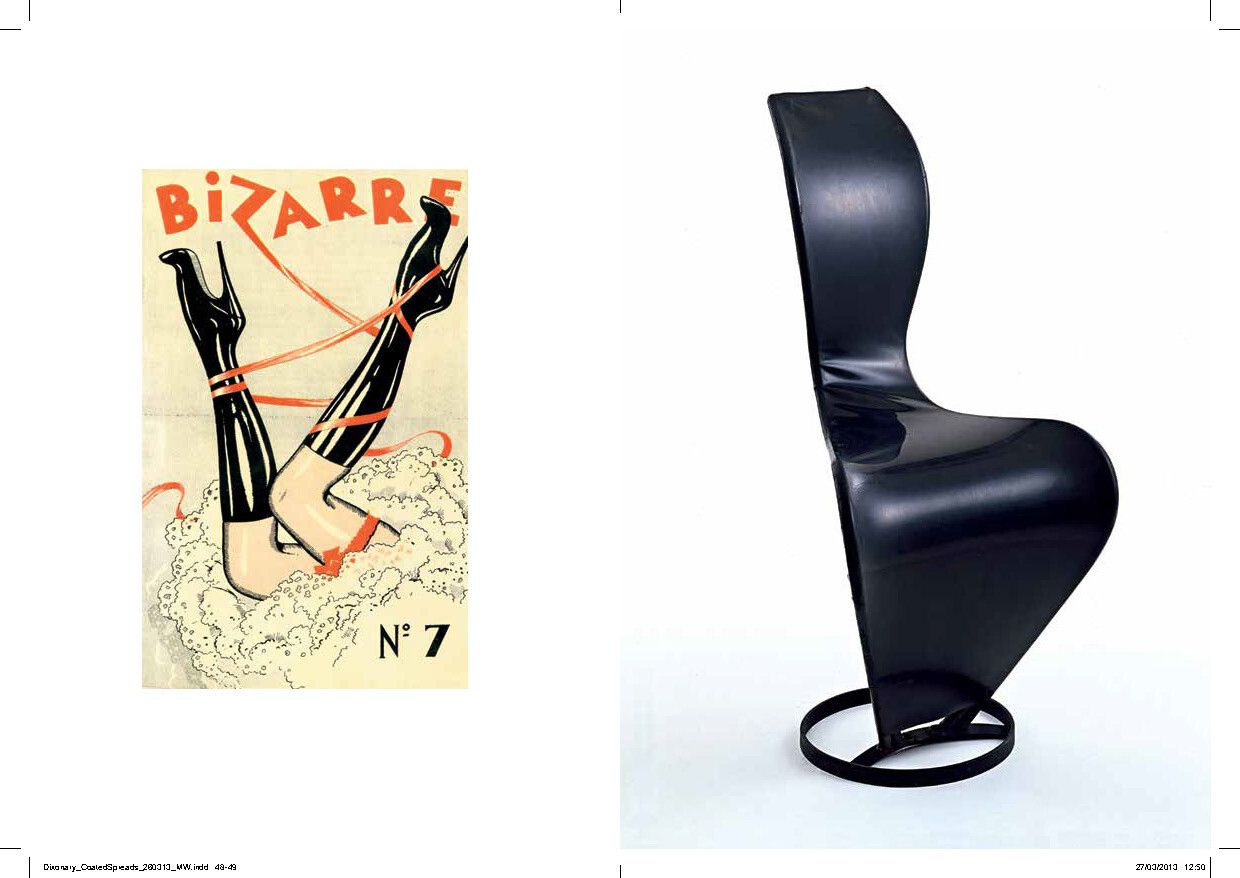

SB: Yeah. I did also want to bring up, while we’re on the longevity tip, the S-Chair, which you’ve called an “old friend.” It’s thirty-five years old this year, technically.

TD: Don’t remind me.

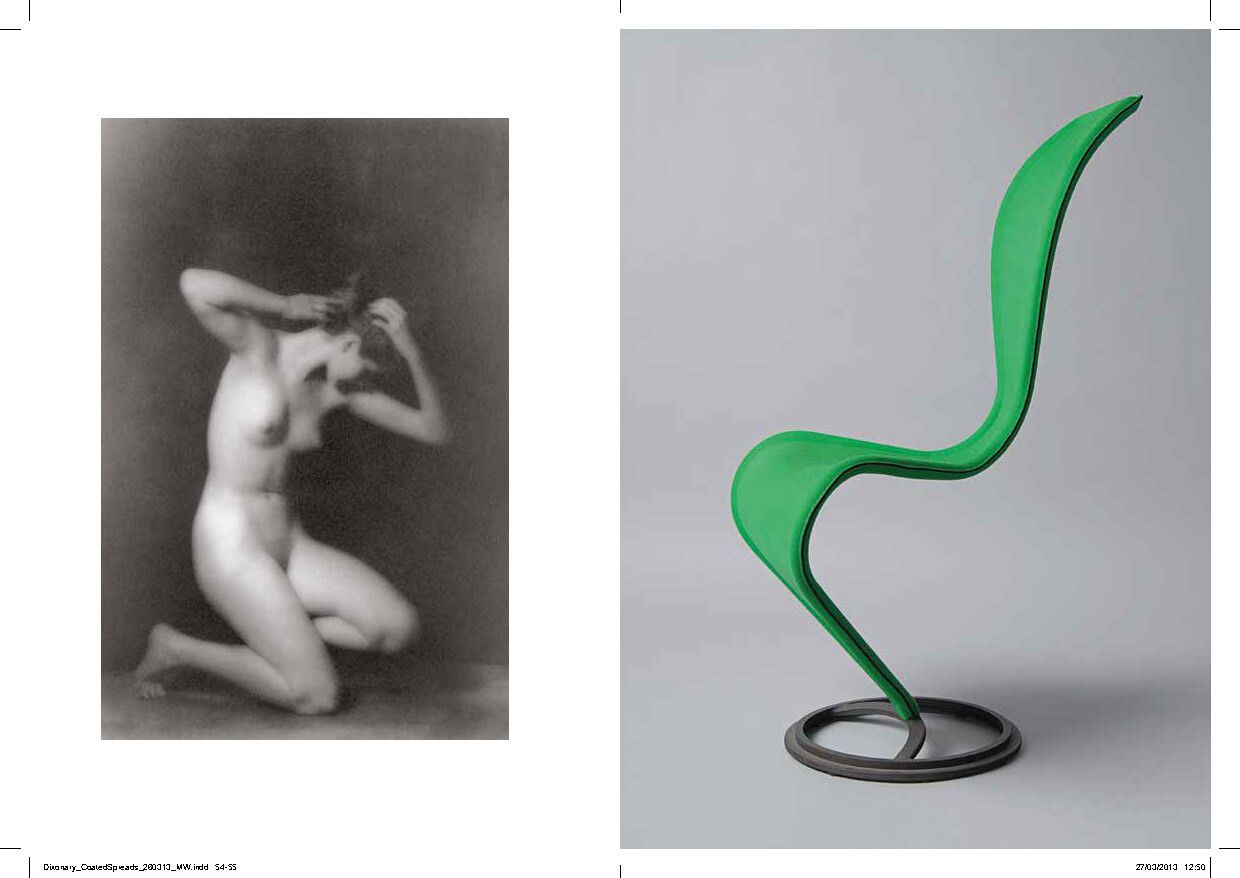

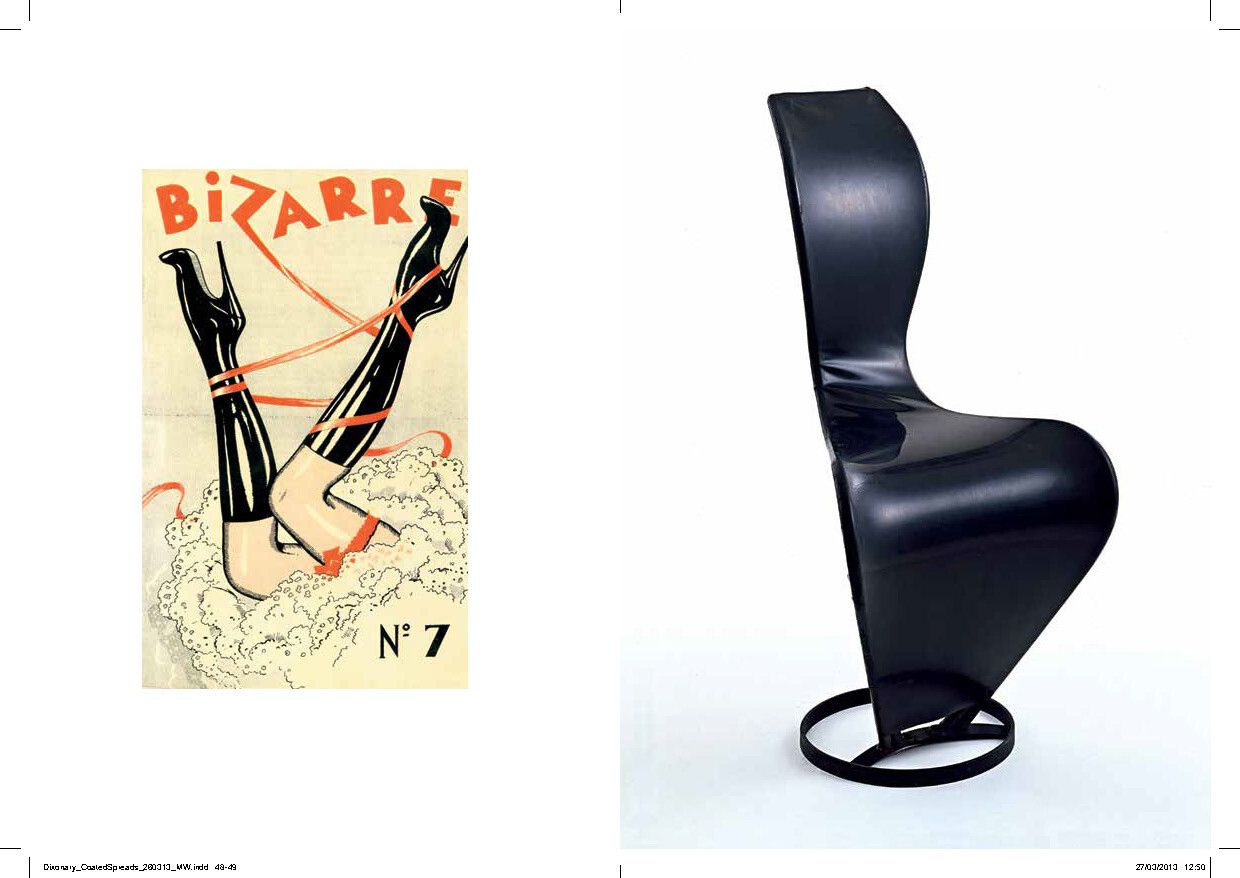

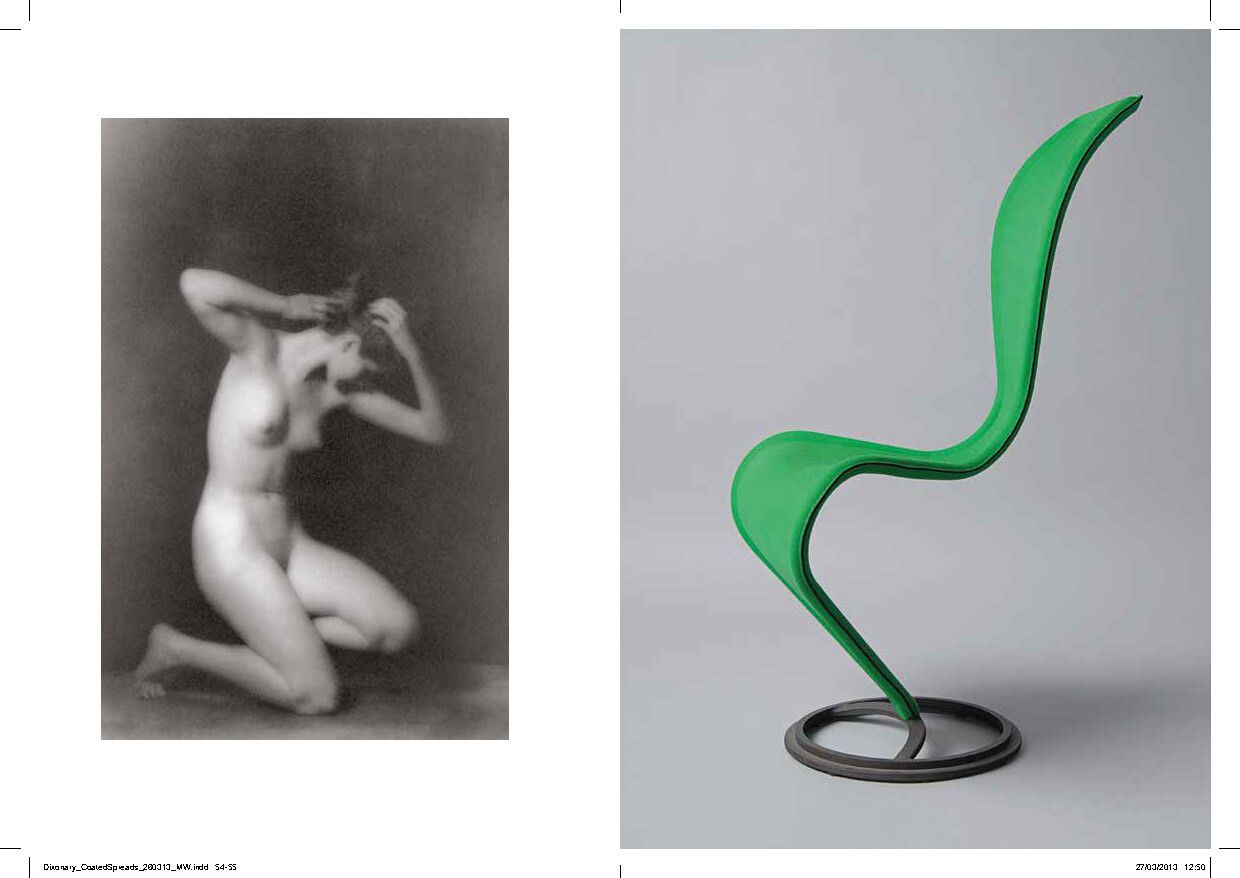

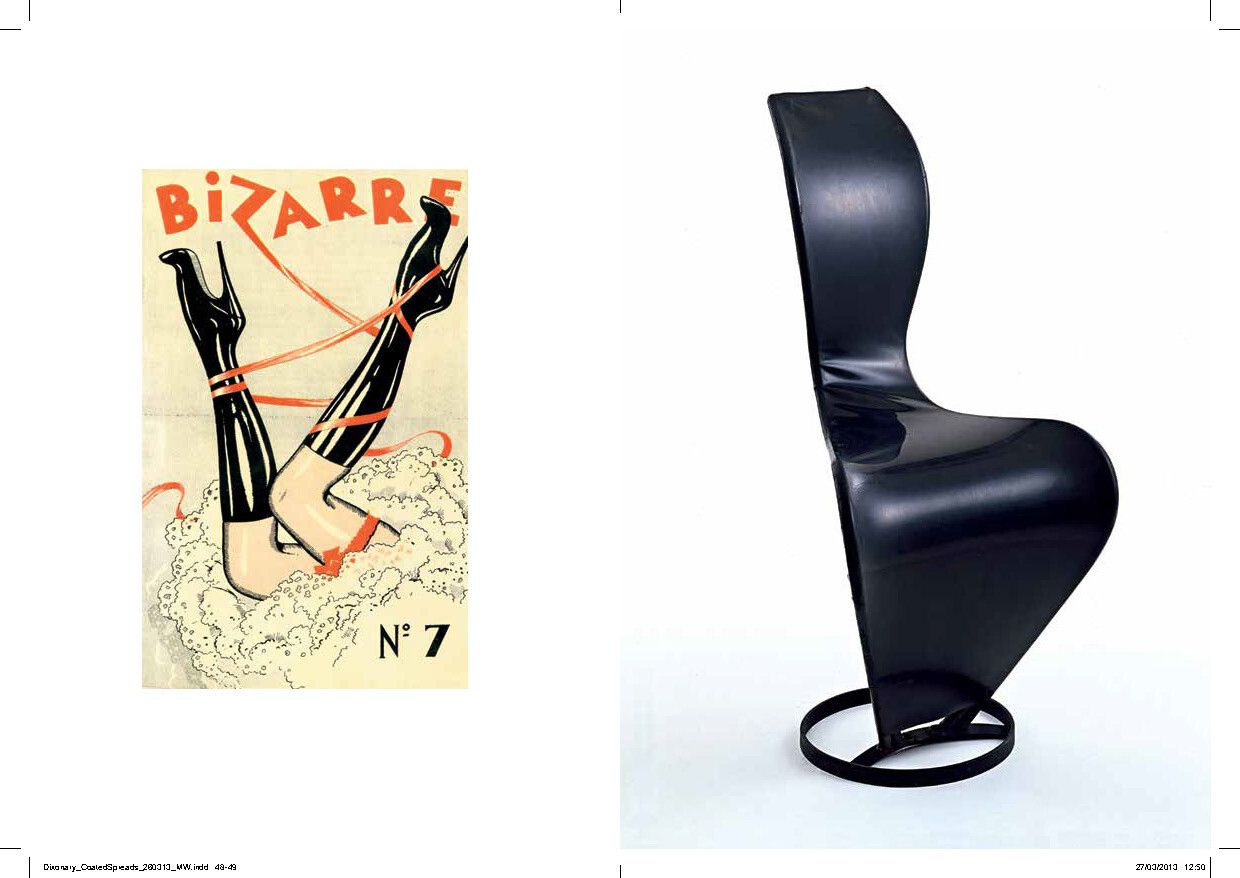

SB: [Laughs] And it started with this doodle you did of a chicken, and then morphed into this sinuous form. Could you talk about this chair across time? I mean, it’s had so many different iterations and, particularly once the Italian company Cappellini picked it up, it kind of became a more mass phenomenon.

The S-Chair, designed by Dixon. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

TD: Yeah, it’s instrumental in my development as a designer, and it sort of followed me around in lots of different iterations.

So I had a friend that had a hairdressing salon and I was still making things out of scrap at the time. And I discovered that the rubber inner tube from car tires was a great upholstery material. And I convinced him to allow me to make a few chairs using some scrap metal and the rubber as upholstery. Hairdressers tend to be really keen on having contemporary interiors, so they’re great clients. For some reason they like the new, the latest thing. So anyway, I set about making these chairs and there were kind of mono-ped chairs with a rotating base—because that’s what he wanted in his salon—and it was very ungainly as an object. So then I moved from making a chair with a round base and a seat above it to try and link the seat and the base in one line, which is when I started drawing chickens for some odd reason.

So it went from being this very ungainly object to being actually quite an elegant and sinuous line, and very anthropomorphic actually. So following the line of the spine and then the legs—and so a great silhouette. Obviously, in rubber, it was a complete disaster from a commercial perspective because people in white jeans at the salon would get black marks—the stuff still stank of the road as well. Rubber, some people love the smell of rubber, many people don’t. So it transformed. I had a great assistant at the time that had been to a furniture college and she’d learnt how to do rush-weaving. We then used a conventional seating material, which would’ve been used for drop-in seats in British traditional chairs, in an unconventional way on this sinuous framework. And suddenly we had a little hit.

So it was my first multiple production item where, rather than just making things out of found objects, like I’d been doing previously, there was enough demand to set up my own tiny production line. It got [to be] too much bulrush to be done by my single assistant, so we got the assistance of the Royal National Institute of Blind People. So blind people used to come into the workshop with guide dogs and amazingly rush these things or weave the rush.

SB: Oh, wow.

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

An iteration of the S-Chair, designed by Dixon, as featured in his book Dixonary. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

TD: It was at that point that Italian industry came calling. So Giulio Cappellini, who’d founded this great, innovative design firm in Italy, had decided that he wanted to go beyond the Italian studios. And there was a moment where everything was in luxury.

Furniture was made by Italians and designed by Italians. And I think that that cycle had run its course over the fifties, sixties, seventies, and eighties. And there was a need for a bit of fresh blood. And Giulio came looking in London—and Japan, actually—where he found Marc Newson was working, in Japan. Jasper Morrison was working in London, as I was, and he [Giulio] was looking for new ideas and our stuff looked unusual to him and had a rawness and a roughness, which he quickly bred out of the objects and gave them a slickness and a luxury finish, which gave it a global market.

So I was introduced to the wonderful world of international design through the Italians. And then subsequently it ends up being right here in your city, in the Museum of Modern Art, which is kind of an amazing accolade apparently. So I’m with the big [Bell-47D1] helicopter in the MoMA.

It gives me an international presence. I’d been very local until then, British people would seek me out. The U.K. didn’t really have a design constitution, in a way, it was before the Design Museum, before design magazines really became popular. And I still make it [the S-Chair] to this day, a different version. I’ve done a prequel for our company and Giulio’s still making the one that he made and the lady’s still rushing the original one thirty-five years later.

Yeah, I mean, that’s a reasonable amount of time if we’re talking about time. We are, aren’t we?

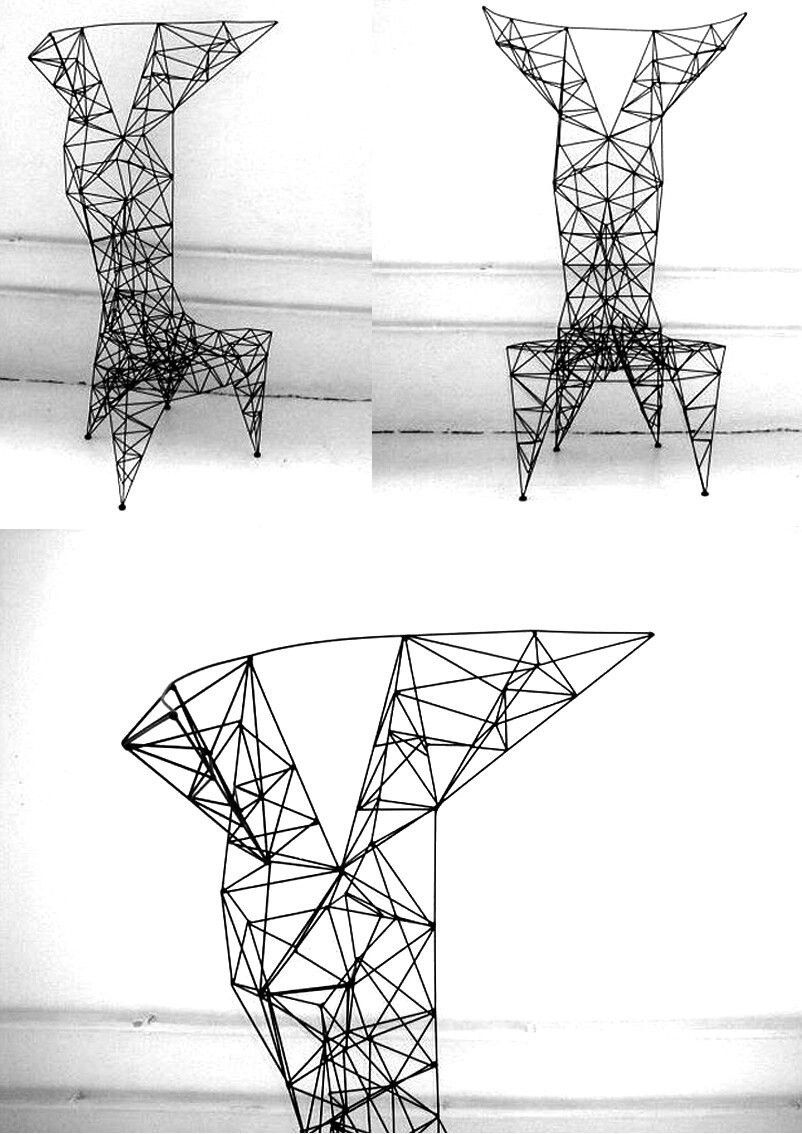

Views of the Pylon Chair, designed by Dixon in collaboration with Cappellini. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

SB: And it led to all these other great products with Cappellini: the Fat Chair, the Pylon Chair, the Bird Chaise.

TD: Yeah. I discovered after a small while that actually working for royalties I wasn’t very good at. So what Giulio was doing was cherry-picking the best designs from the studio, which were the things that were making me my living. So I was selling things that we made direct to galleries around the world, but then going from that scenario to not having anything to sell because it was going through Italian industry and getting a royalty eventually was not a great way of actually making a living for me. Because I was never prolific enough as an industrial designer to have that many ideas. Maybe I should have stuck with it, but I didn’t.

SB: You also had these other great light products in the early nineties, I wanted to bring up, Paper Totems, the Star Lamp. And these were really interesting, I think, from just a simple material perspective—you’re basically using paper. They did remind me a little bit of Noguchi’s Akari lanterns. And I understand that you showed the Totems here in New York at Comme des Garçons in ’92.

TD: Yeah, I discovered Japanese paper through…. I was more interested in geometry than I was in paper lanterns. And I’d made a series of frameworks coming from the Pylon Chair, and I started playing with using tissue paper and it was my first lighting hit. But the problem with paper and metal frameworks is that, although they were quite desirable and we sold a lot of them, as soon as people would pull them out of the box, they would stick their thumb through the paper. And it never really worked commercially because they had so many returns.

So that’s when I started dabbling in plastic, actually, to try and find a way of making things which had more permanence. So the totemic phase was actually more in sculpture terms inspired by [Constantin] Brâncuși, in terms of the shapes. But of course there’s a lineage from Brâncuși to Noguchi, right?

SB: Indeed. 1927.

TD: 1927. So yeah, like I say, for me, sculpture, I work much more in that way rather than [as an] industrial designer. And my inspiration was definitely sculpture for a long time, and I didn’t really understand how much work Noguchi had done, but obviously I’d seen the stuff, yeah.

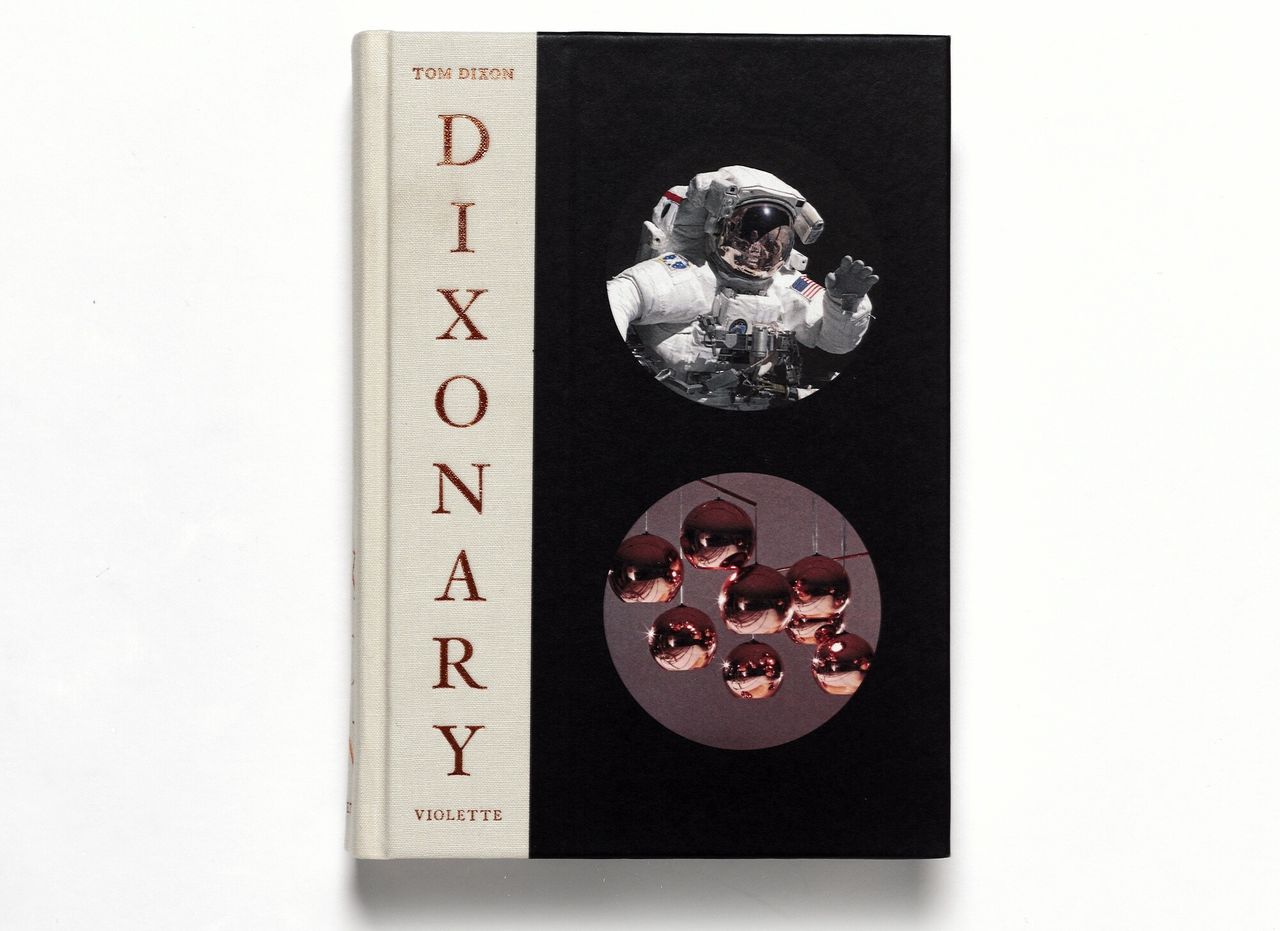

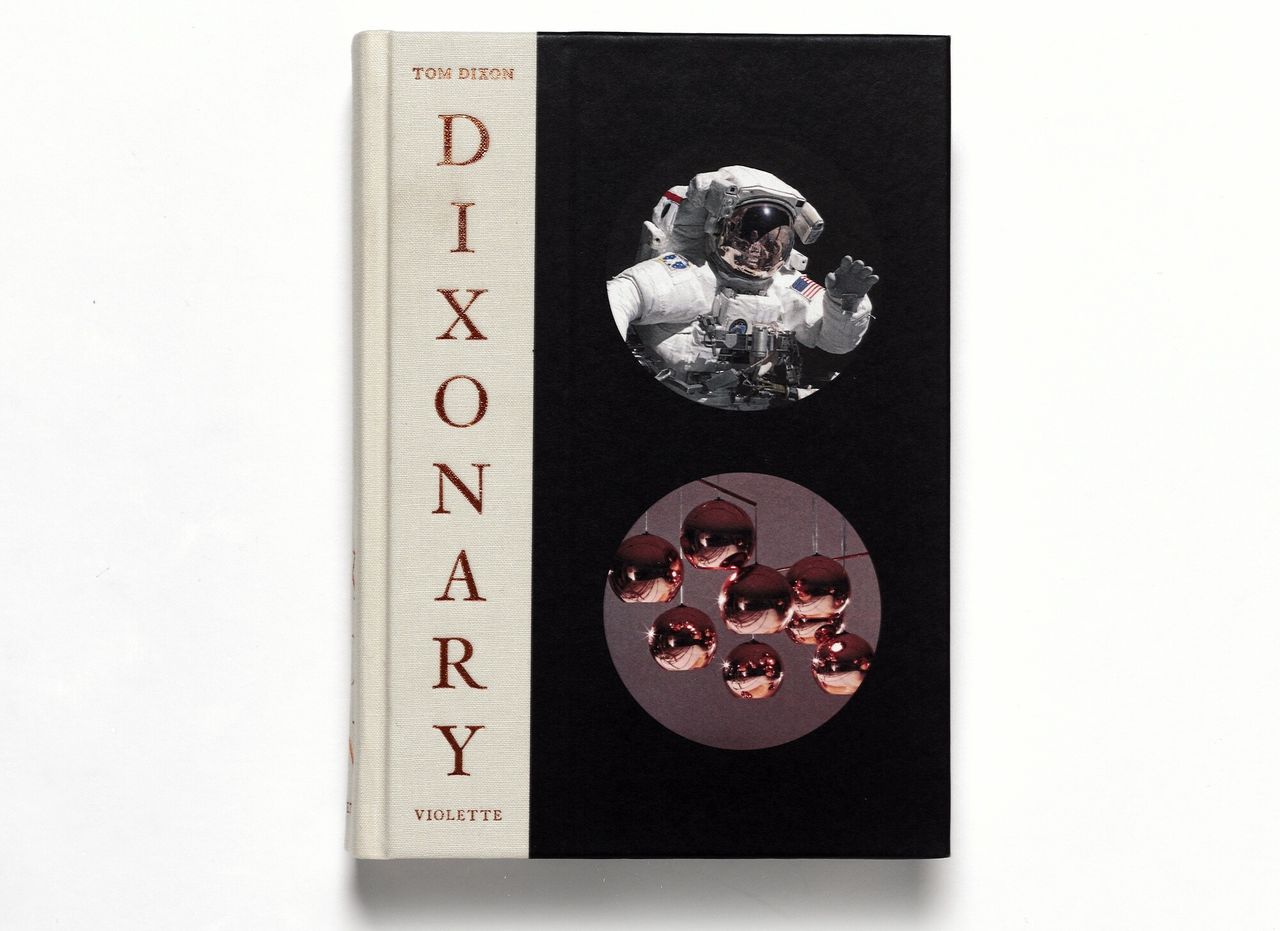

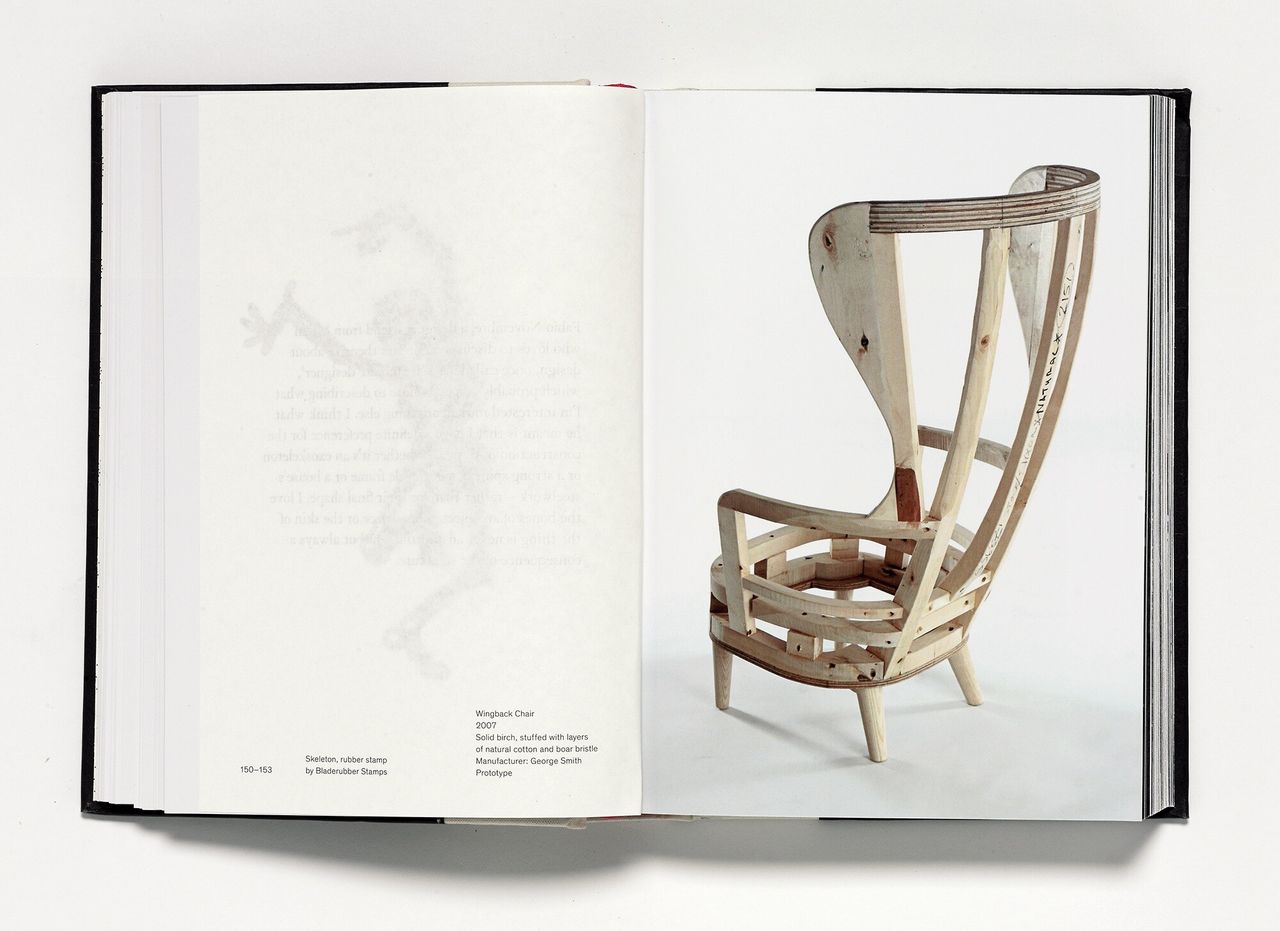

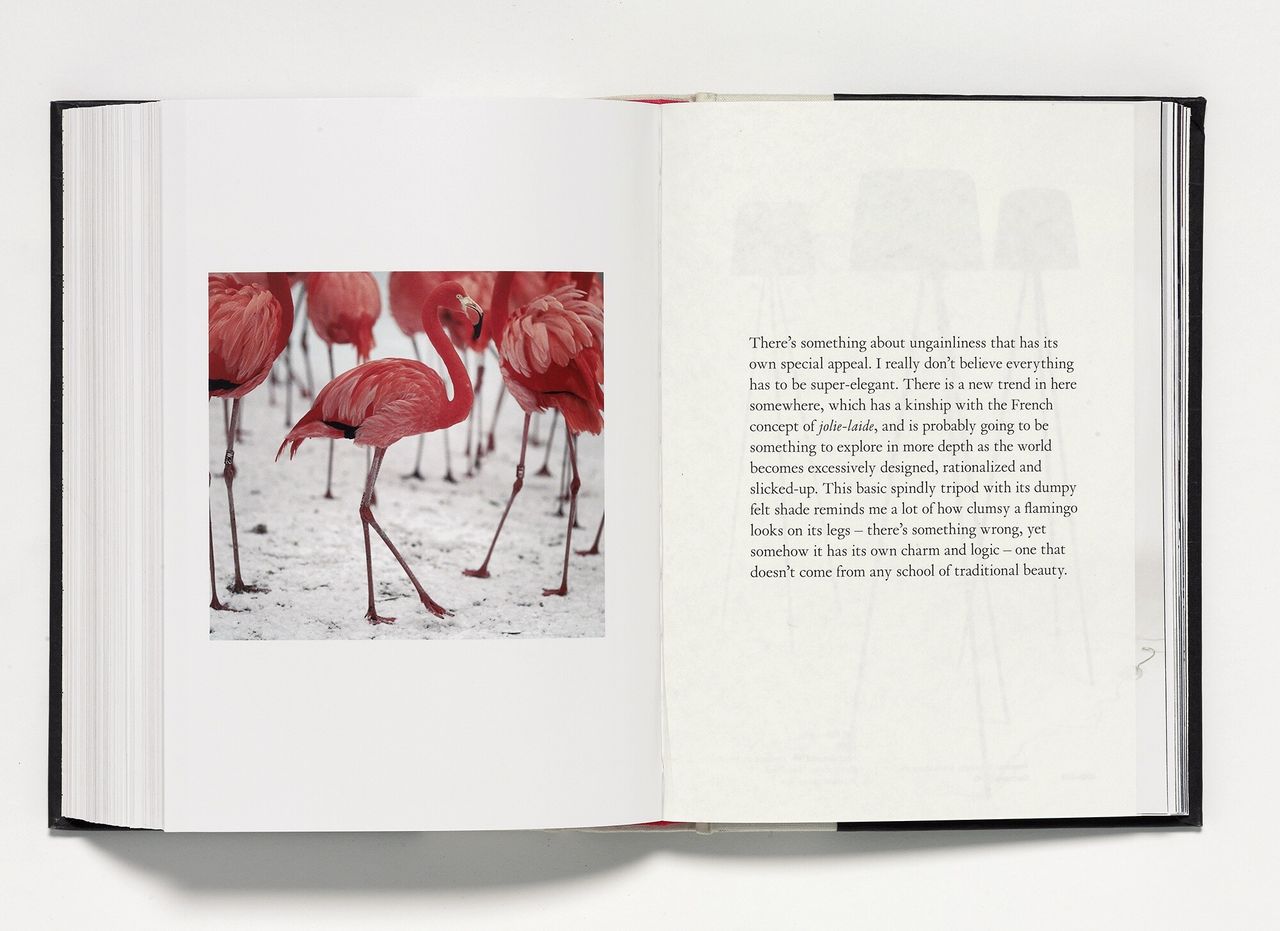

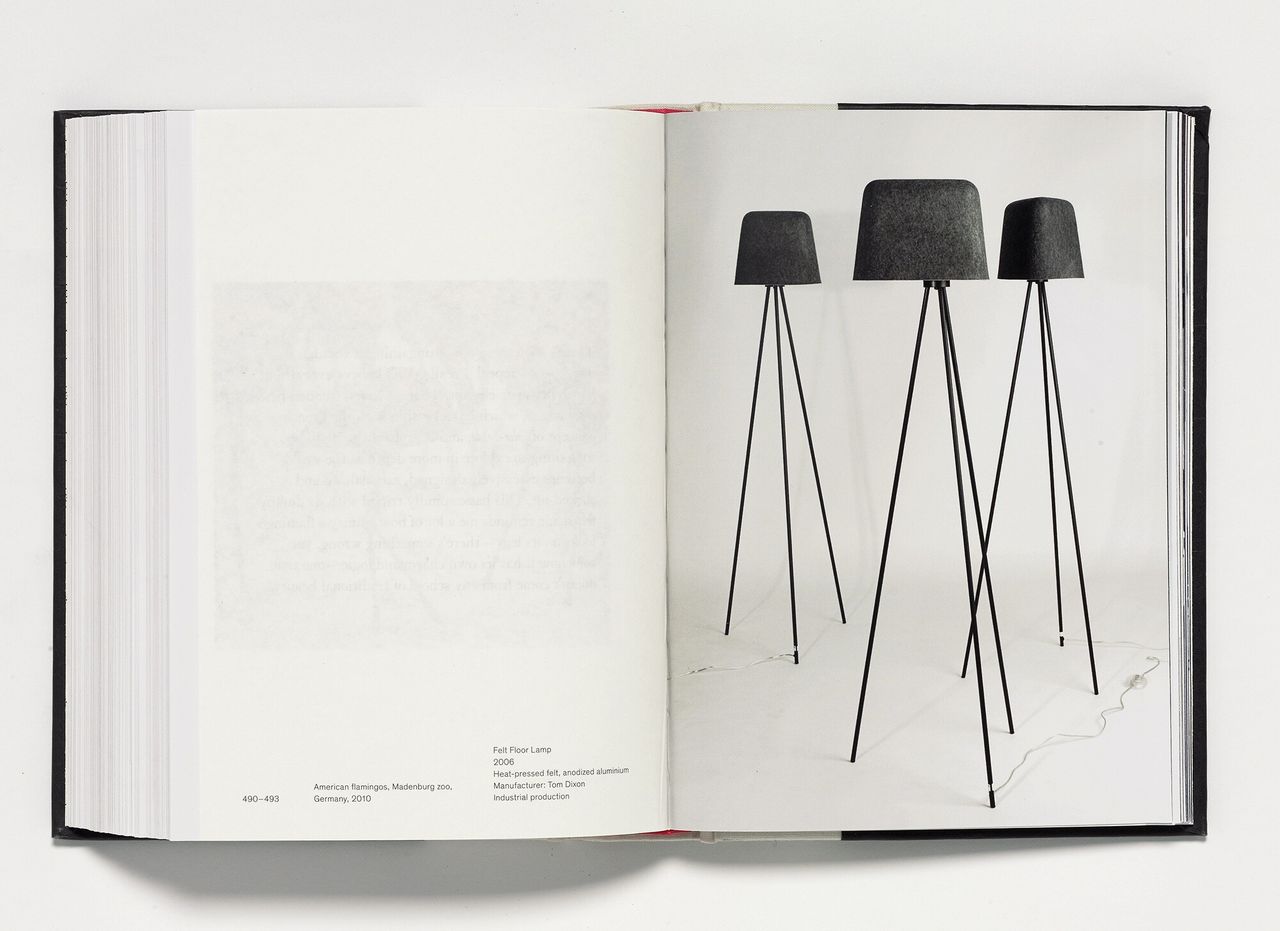

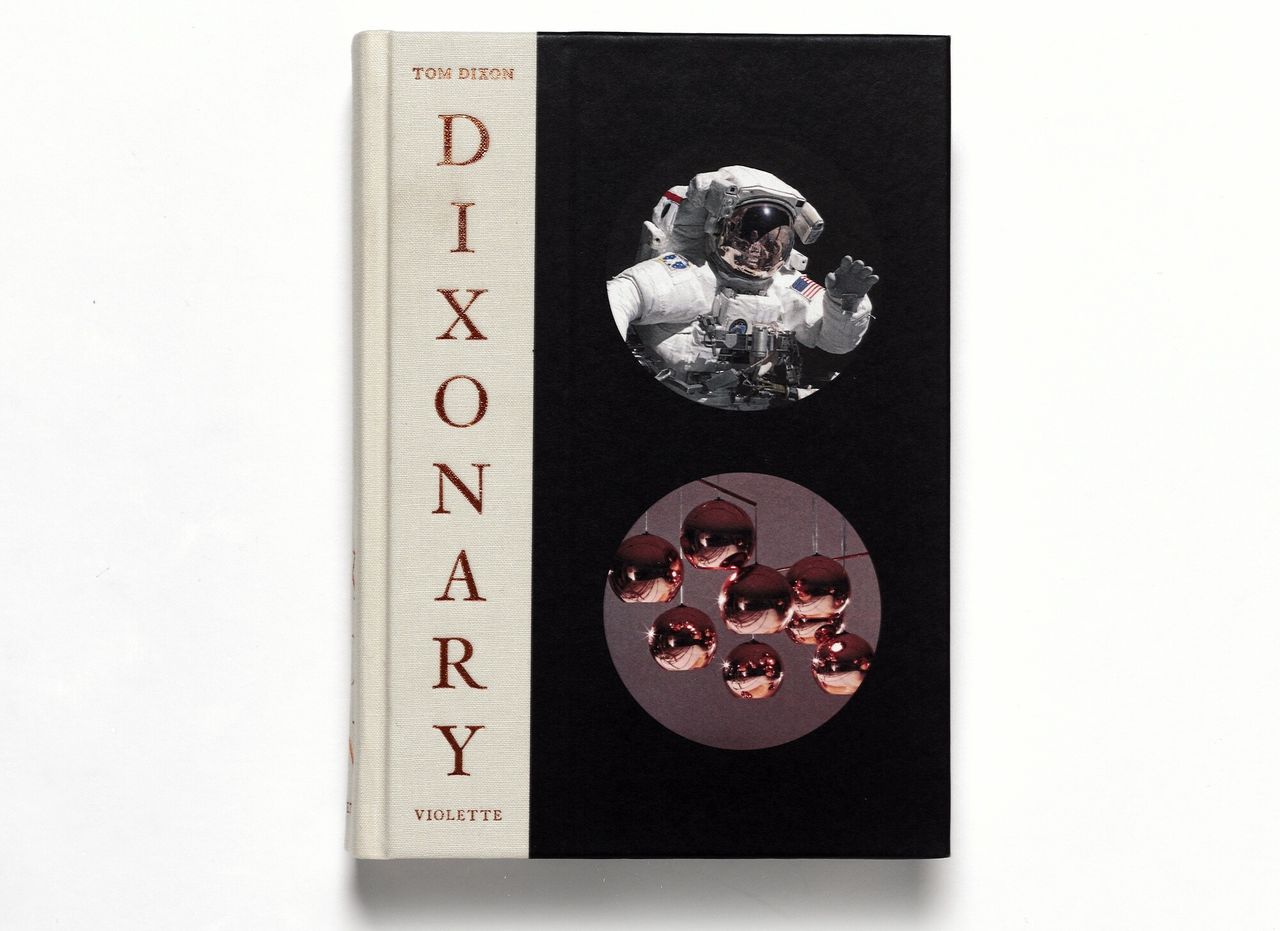

Cover of Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

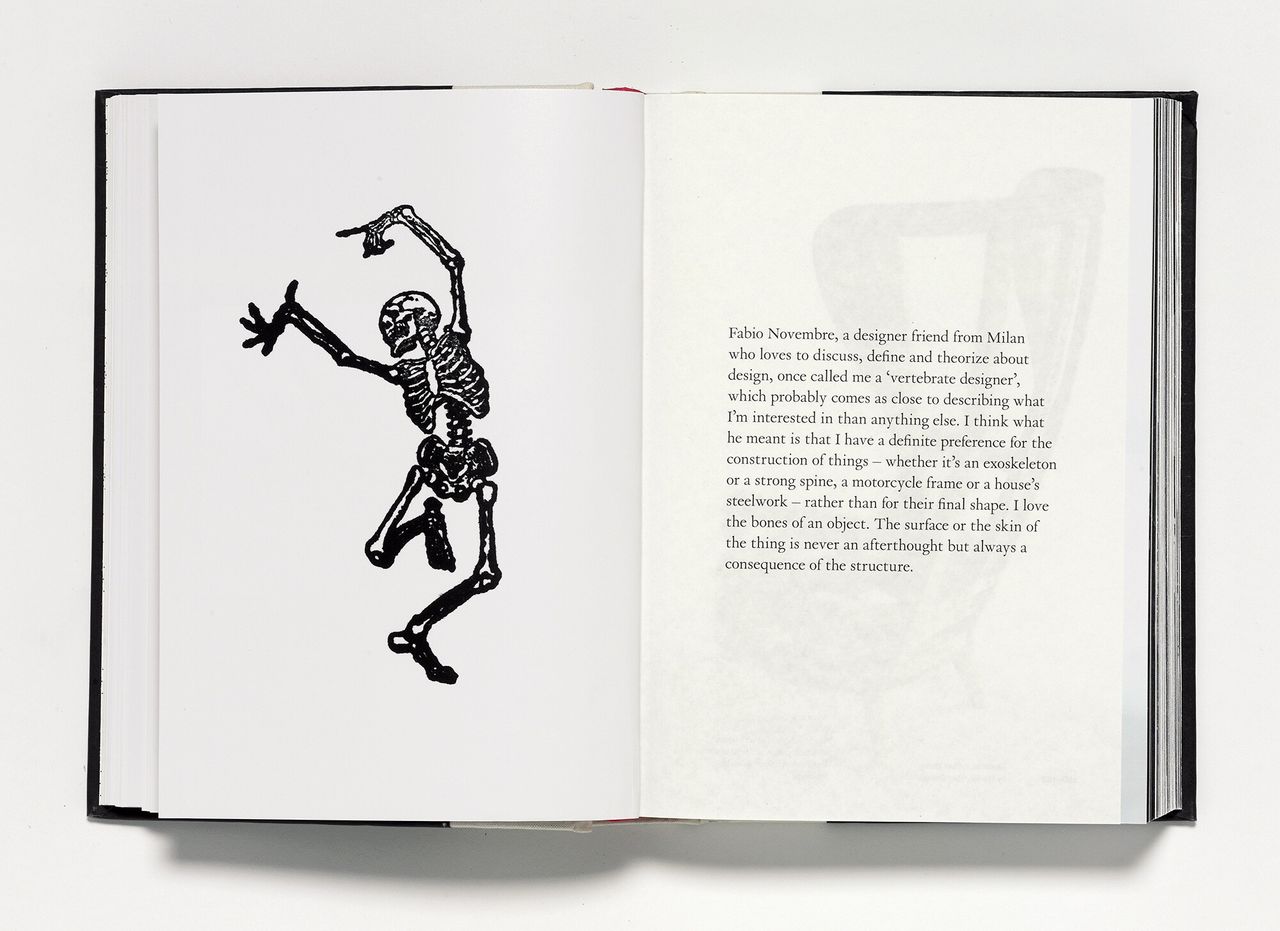

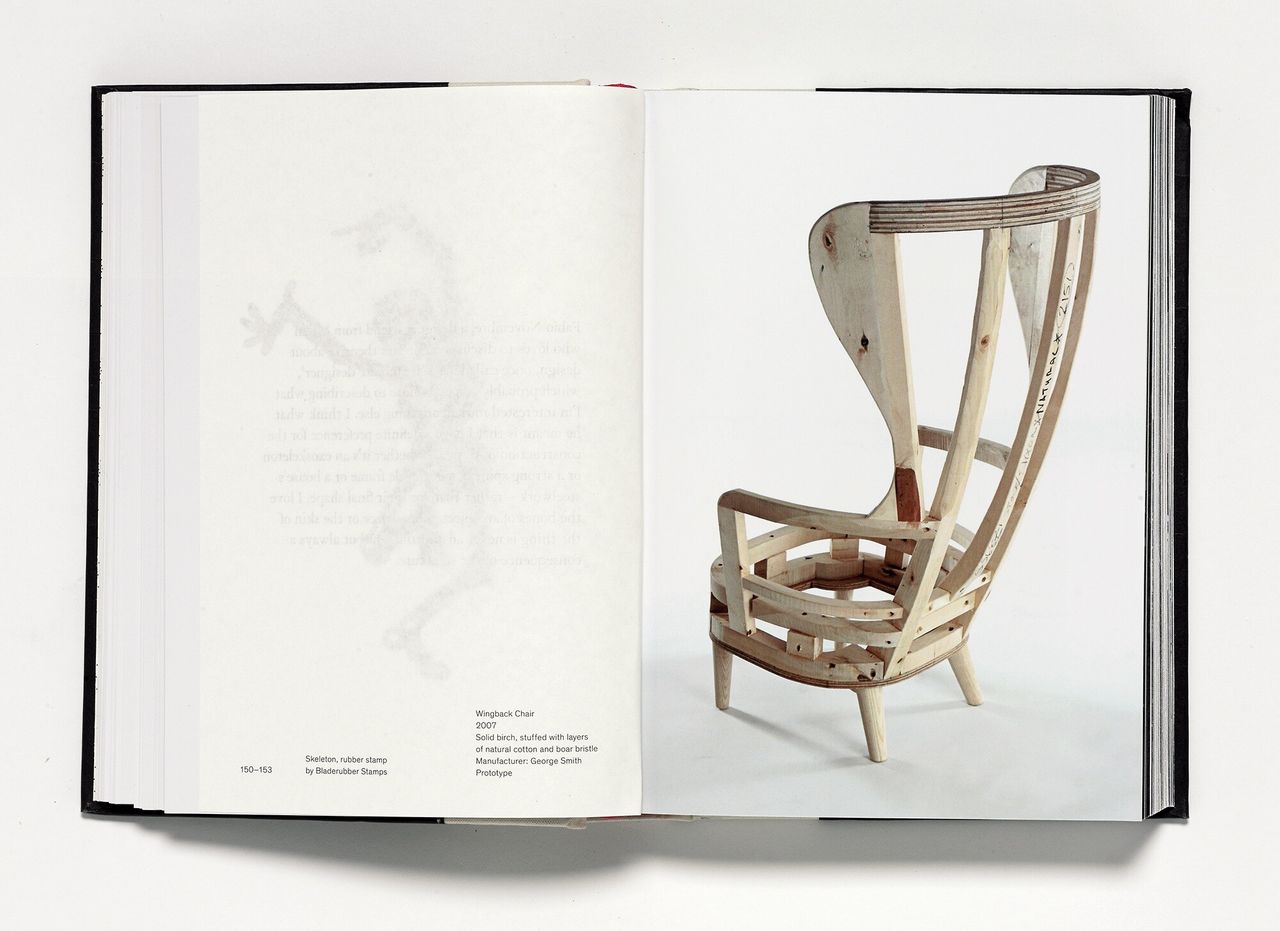

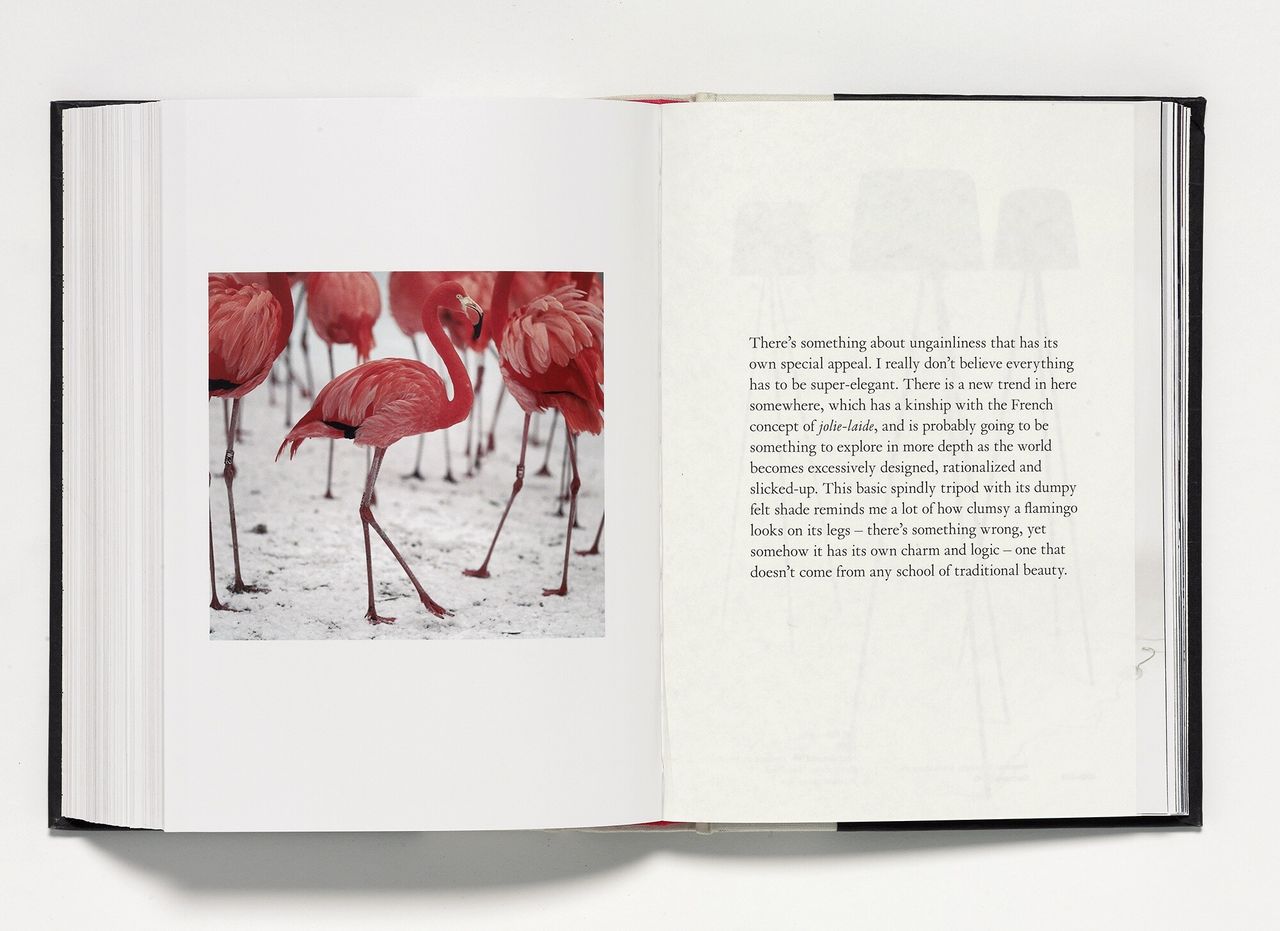

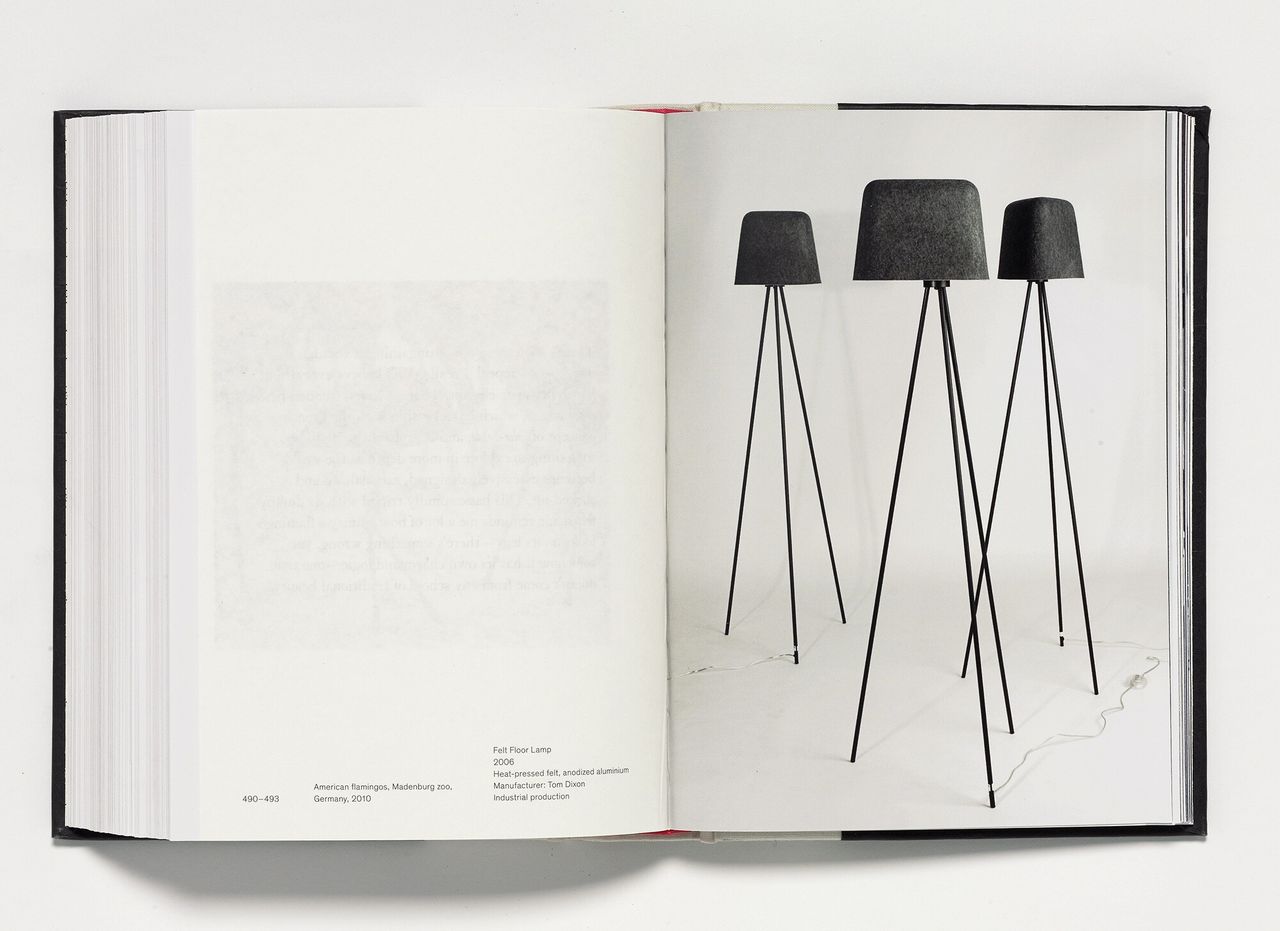

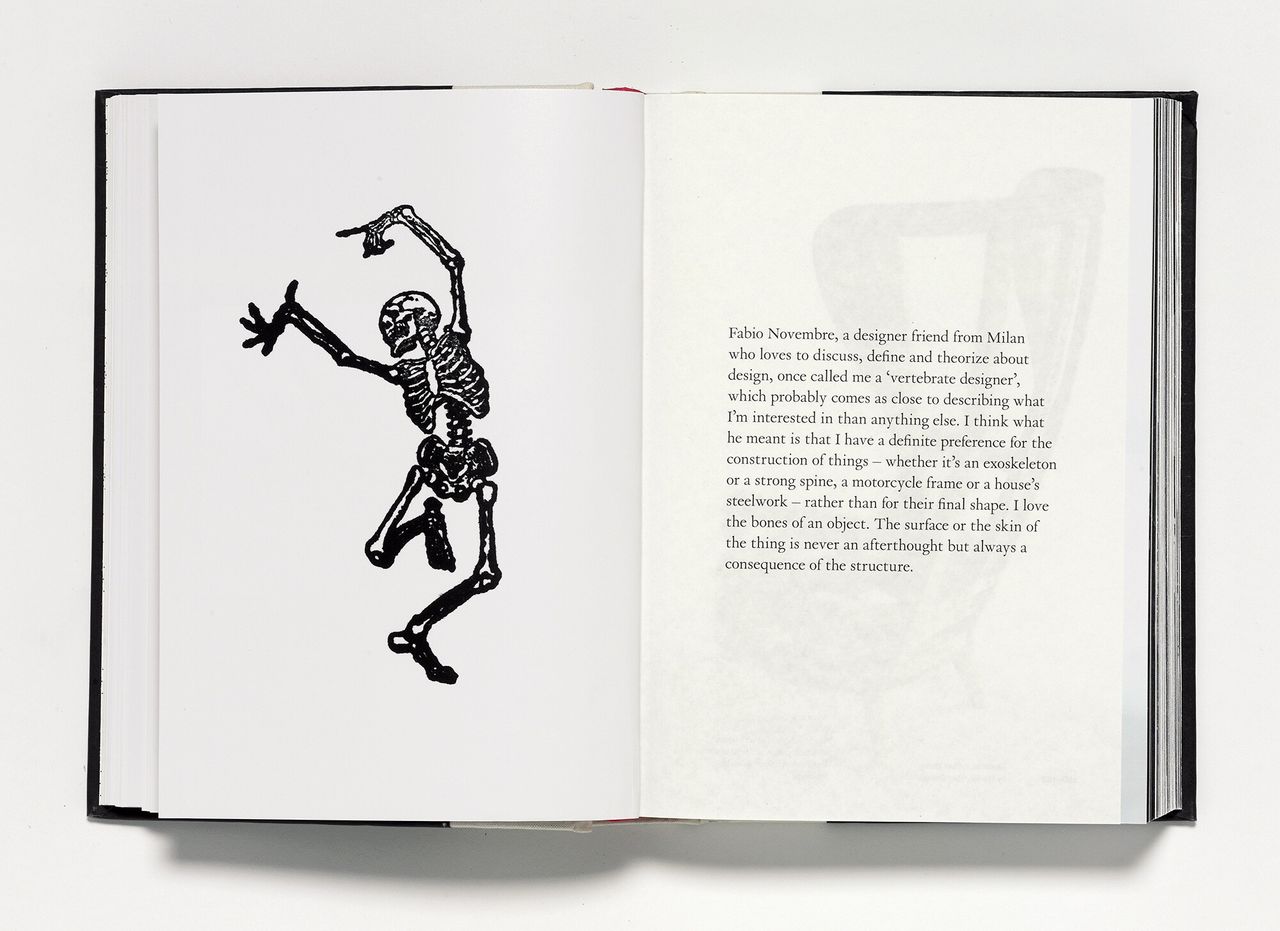

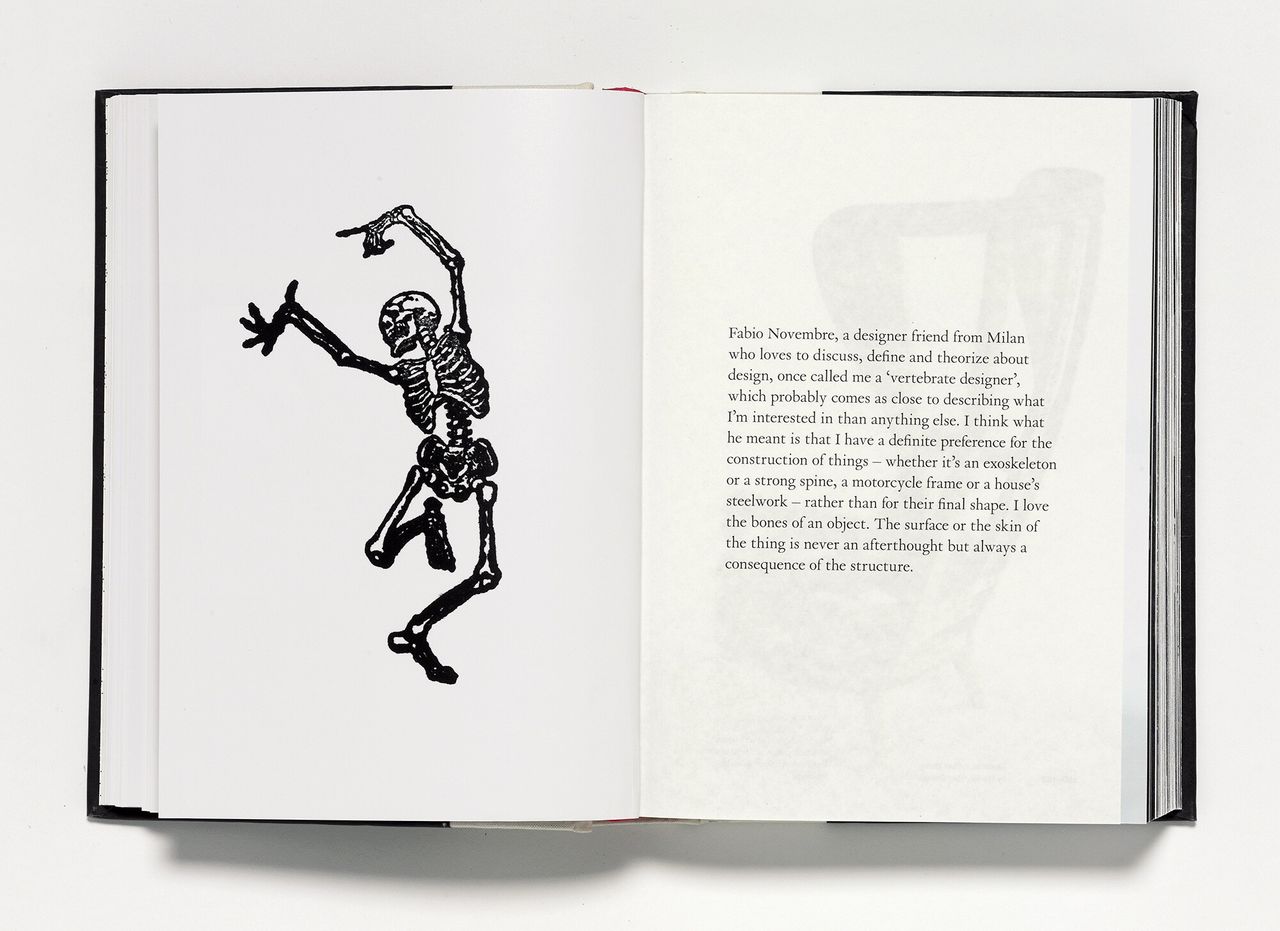

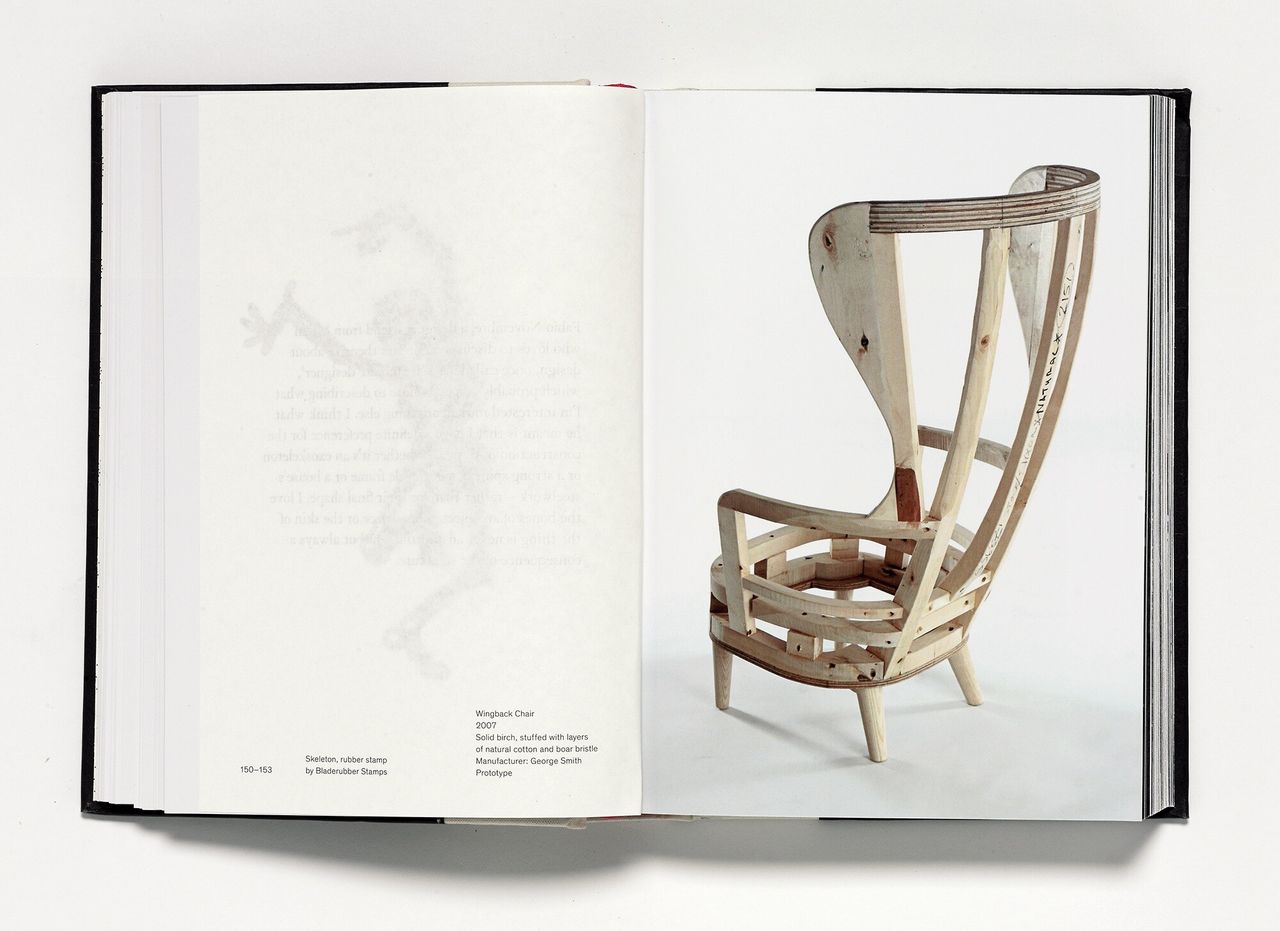

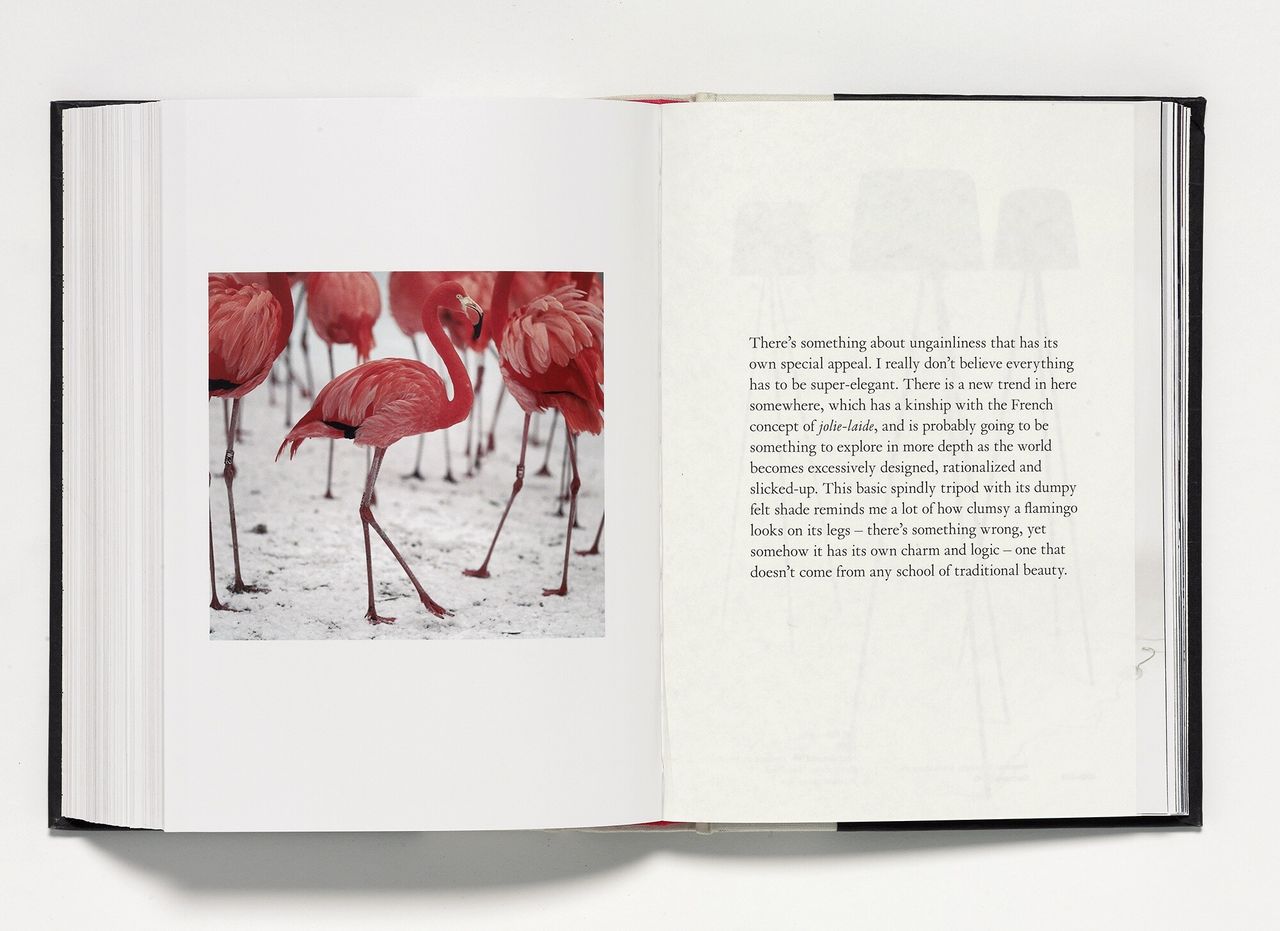

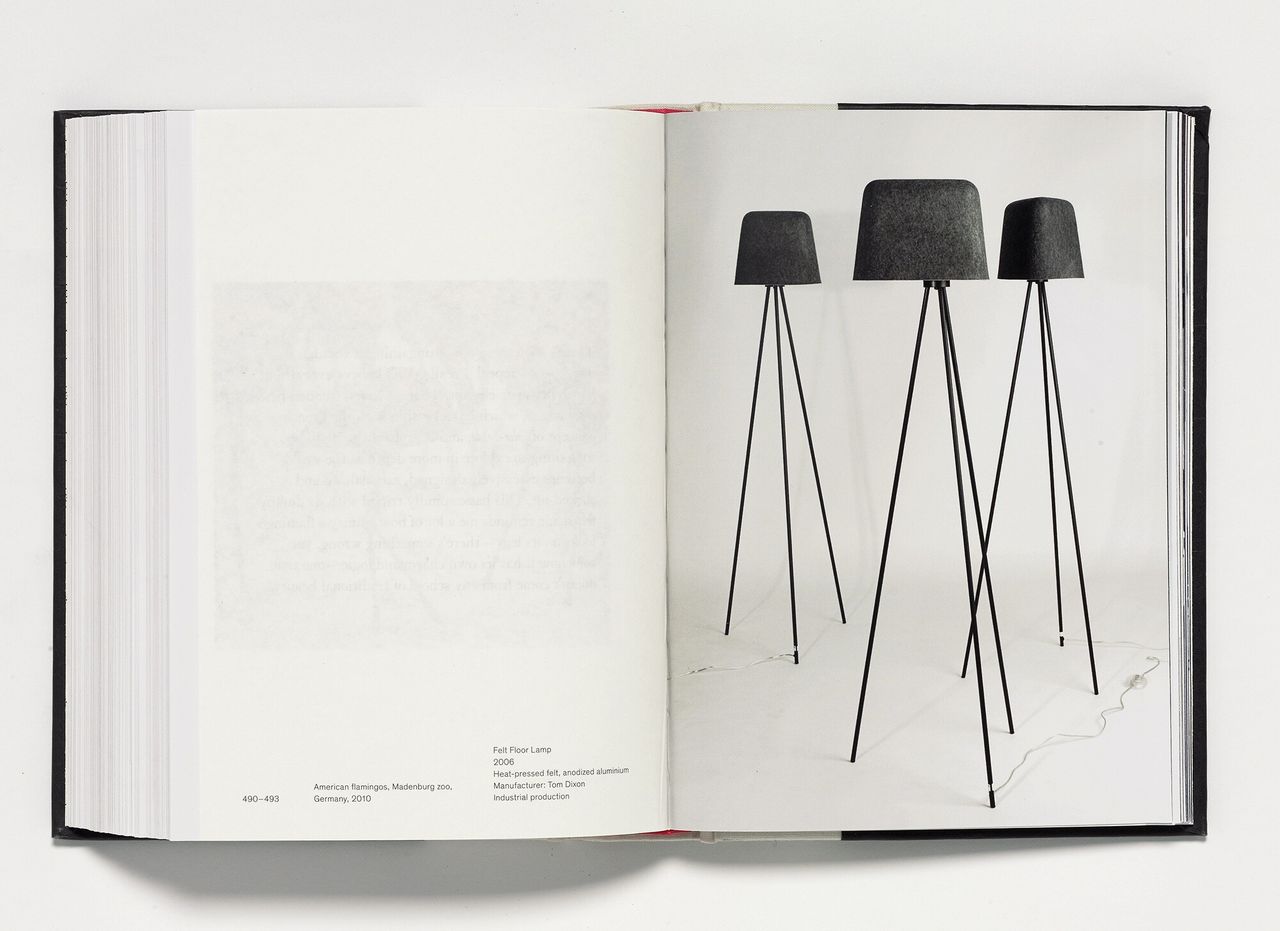

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

Cover of Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

Cover of Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

A spread from Dixonary (2013) by Tom Dixon. (Courtesy Violette Editions)

SB: And in your book Dixonary, you do show a few Brâncuși pieces, including “Torso of a Young Man” and “Fish,” which kind of were loose references to your work, it seems. Can you talk a little bit about the Brâncuși influence on your particular.…

“The thing that I like about sculpture is that attention to materials and the idea of extracting the most out of the material.”

TD: Well, I like primitivism and I love the idea that he walked from Romania to Paris and set up in what must have been really a quite tough environment. Of course his studio has been moved into the Centre Pompidou, adjacent to it. And you can still visit and see that real simplicity and the emergence of minimalism and sculpture happening there. And a real moment in time in the twenties in Paris where everything was being challenged and rethought. But of course his craftsmanship in stone and wood and bronze is kind of beyond belief. And the constructions— He was super influential in so many ways. And for so many people as well, it was like [Antoine] Bourdelle and Noguchi and all the rest of them, presumably Henry Moore in the British school as well.

It would’ve been amazing, being there at that time. So anyway, the thing that I like about sculpture is that attention to materials and the idea of extracting the most out of the material.

A painting of Joan of Arc.

SB: Let’s go back in time to your family, and I want to start with Joan of Arc [laughter], who I understand you’re related to, twenty-seven generations past.

TD: Yeah. Okay. So Joan of Arc is a bit difficult because Joan of Arc, obviously—being a virgin—did not have any descendants. And so I’m related to her brother. And of course, they were a peasant family. So normally, peasant families would not be documented, being illiterate and there being no documentation. But because the family really organized a sainthood as well, as soon as she becomes a saint then the family becomes very documented indeed. Her brother turns out to have been, according to some accounts, a bit of a crook and kind of organized her re-arrival as an afterlife figure and paraded her around and made money from it. It sounds great, but you wonder whether it was the right part of the family that I’m associated, with him.

SB: And your parents, your father was an English teacher, your mother worked for the BBC, and you were born in Tunisia. In 1965, the family moved to London. Tell me a little bit about your upbringing and also maybe the schooling you were alluding to earlier with the ceramics.

TD: Yeah, so I guess a lot of people that have traveled a lot or come from mixed backgrounds, it seems to fuel creativity in a way. So I was born in Tunisia, but I lived in Morocco and Egypt until I was about 4. Then we moved to Northern England. My mother’s half French, half Latvian. So I’ve got a bit of Nordic. If I tell people that I was born in North Africa, people instantly assume that I’m Arabic, but I’m not.

Yeah, so we moved to London and so I’m effectively a Londoner, but I’ve always spoken French to my mother—still do. And it gives you another dimension, another sense of humor, another culture, and a different way of looking at the world, if you are bilingual, I think. And so that was instrumental.

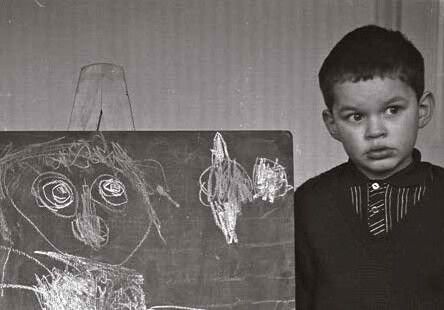

Dixon as a young boy. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

I went to what we called “comprehensive school” in London, a place called Holland Park, which was a kind of experiment in education where there was no streaming, so people weren’t put in classes according to their talent. They were just lumped together. And there wasn’t a great deal of academic excellence at that school, but it had been purpose-built. So it had a really great metal shop and wood shop, and they taught technical drawing, for people that weren’t academic, and ceramics and photography.

Effectively, it acted as a little art school for me, and I could really bury myself in making things rather than studying them. I wasn’t bad academically, the school was bad academically. I was very bookish. I could read, I could write—a couple of languages—but I wasn’t encouraged in mathematics or geography or biology or anything scientific. But the art departments were—and have vanished, actually, even in those schools. Those art departments don’t exist in that way anymore.

So I was very fortunate in that way, although I do sometimes feel a bit jealous of people that are good at maths.

Dixon in his younger years. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

SB: I read that your first job was at age 12 as a newspaper delivery—

TD: Oh, my God, that was right. Well, everybody had an early-morning job. Yeah, I delivered newspapers. Did you not?

SB: [Laughs] No, I didn’t.

TD: Lemonade stand?

[Laughter]

SB: True.

TD: Yeah. So yeah, delivery boy, whenever there was work going, I would do work. I like working.

SB: I can’t have this interview if we’re talking about the life of Tom Dixon without talking about Funkapolitan.

TD: It’s not a very good name, right? But yeah, it was an interesting moment for me.

SB: This band you played in, which was signed to Polydor [Records], toured with Ziggy Marley, The Clash—you even appeared on Top of the Pops.

TD: Is Top of the Pops a thing in America? Surely not.

SB: Not really. I think most people might know it, though.

TD: Yeah? Okay. It doesn’t exist anymore. So just like any self-respecting British lads, we were in a band, so—I mean, that’s America as well. But in kind of retrofitting my history, I’m very aware of the role that music played in, first of all, stopping me being introverted, right? Because I wasn’t super confident. But you have to fight for your spot in a band—eight other lads in a transit van. You’ve got to fight for your spot, and then you’re pushed onto stage, you’ve got to perform.

So what was interesting, and again the story that I like to remember is this idea that you learn your own instruments. There’s no formal training, there’s a lot of self-determination in the tunes that you make up or the gigs that you play or the posters that you make. And you’re effectively making a little industry there, you’re eventually then bought by a big corporation.And I’ve mimicked, a bit, that in the design world, picking up my own instrument, which at that point was the welding torch, and then making my own things and doing my own gigs was effectively doing exhibitions. And so that whole experience in music was very much a kind of awakening to the potential of creating your own destiny and making a living out of your own ideas.

I don’t think I was consciously doing that, but if I look back, it’s definitely a pivotal moment and also at an age where that’s really influential, to be able to see your ideas turning into something that people buy.

SB: Yeah, it was also creating a sort of attitude, which is interesting. I mean, I did before this interview, listen to a couple of the songs.

TD: Oh no, I hope you’re not going to play them on your podcast.

SB: No.

TD: Thank you.

SB: No, we won’t, don’t worry. But we can link to them. These songs “If Only” and “In the Crime of Life”—it was interesting to hear the mix of influences going into this music. Clearly, you were trying to capture some sort of, as a band does, spirit, attitude.

TD: Okay, well you can see me wriggling in my chair, not on the podcast, but you’re making me feel very uncomfortable. I mean, the tunes and the music—particularly the recorded ones—did not really come up to the level of our expectations. In fact, we were more fun and more interesting as a kind of loose and very kind of punk-y disco band playing in London.

As soon as we signed to a record label, a lot of the fun and energy went out of it. So suddenly you went from playing to a home crowd that was very enthusiastic, with real momentum and people recognizing your tunes to being forced into a recording studio, probably with the wrong producer. That was August Darnell, Kid Creole actually, who didn’t really understand the London vibe, I don’t think. He was a professional, proper musician rather than what we were, which was improper in the extreme.

But it was a moment. And like I said, the transition from being amateur to being professional, to being in a record company, to touring the world was really quite fast. That was my first encounter with New York, actually, was on Broadway with The Clash. And that was all about growing up. I mean, people really didn’t want to hear what we were doing. They wanted to hear The Clash. So we had some very uncomfortable moments on stage at Bonds International Discotheque on Broadway.

SB: [Laughs] Things thrown at you?

“We had a lot of plastic cups chucked in our direction.”

TD: Yeah, I mean, luckily glass was already banned, but we had a lot of plastic cups chucked in our direction. And weirdly, I didn’t even listen to The Clash. We could hear them in the background, but I wasn’t really interested in that. I’ve become more interested in them since, unfortunately.

SB: You also had these two really life-changing motorbike accidents, sort of back to back.

TD: Mm-hmm.

SB: One where your leg was injured and one where your arm was injured. Could you talk about those, and also how your response to those led you on the path you’re on today?

TD: Well, I’d started at art school. I really didn’t know what I wanted to do when I was, I guess, 18. I didn’t enjoy it at all. Three months in, I had a motorbike crash, broke my leg, and couldn’t move for a couple of months. And so I never went back. And then got my first proper job, which was as a technician in another art school, which was revolutionary for me—earning money, getting up and getting to work at seven, working with some engineers that were looking after the workshop. And that was kind of great.

So I had a series of odd jobs that went from workshop technician, [to] coloring in cartoon for cartoon films when they were still colored in by hand, [to] working as a kind of like—

SB: That must have been painstaking.

TD: It was boring, but it taught me a bit of precision. I did fruit-picking, I did motorcycle delivery, I did printing…. I was assisting in a printing works. So a wide variety of odd jobs whilst the music started growing underneath it all. And suddenly we were being signed up and professionalized as a band.

But I think those experiences of getting out of art school and getting into real life, which was something that I realized I was desperate for anyway, and earning money and enjoying life a lot more—because I really hadn’t enjoyed school very much—was fundamental. And then the band took off, the band went on the road, and then maybe a year into signing a record contract, I was on the motorcycle again and crashed into a BMW car and smashed my arm up, on the eve of a tour. So I was replaced by a much more effective session bass player who took my place and I wasn’t able to return. So obviously I was bitter at the time, but he was a friend of mine—and still is.

SB: The bass player?

TD: The bass player, plays with Pink Floyd, that his….

SB: Now?

TD: Yeah, he’s a replacement for Roger Waters when they tour. Guy Pratt. He’s got a podcast as well, if you want to listen to it. [Laughter] Yeah, so that was the end of my music career. By that time we’d already been to New York; we’d seen a lot of clubs in the kind of nascent rap scene, which at the time was much less commercialized, and it was closer to poetry than it was to what you think of as rap now. And some of those clubs were really quite chill cultural places and we thought we’d start that in London. So we started, alongside the band, we started a few clubs in London and they became reasonably successful.

So when I had my motorbike smash, I had another means of living, which was the nightclub business. And obviously you make money on Friday and Saturday nights and then the rest of your week is available for tinkering, which is what I did.

SB: The welding. And in the mid-eighties you started Creative Salvage. Could you talk about that project? That seems like an interesting thing to bring up here, given that so much of the experimentation happening during that time, I think, led to the S-Chair, you could argue.

“We ended up using it as a means of entertainment, welding, live on stage at the nightclub.”

TD: Well, so I’d learned to weld in a friend’s kind of car shop where he was restoring vintage cars. I’d acquired a few vintage cars and motorcycles along the way, and I always thought that I’d be good at doing that. We ended up using it as a means of entertainment, the welding, live on stage at the nightclub.

What was kind of interesting about the nightclub business is that you suddenly have this big demographic of people that you know vaguely—people that are themselves, hairdressers, musicians, photographers, fashion designers, eventually. And they will need something. So when they saw me welding on stage, they knew that I was making stuff and people would come to me for things. So the hairdresser for the chair, the people from Paul Smith, or…. A lot of fashion designers were early clients. We talked about Comme des Garçons. Or Vivienne Westwood. All these people were hovering around the clubs and needed stuff, whether it was a stage set for a photography shoot or a piece of shop fit for a fashion store.

Dixon painting. (Courtesy Tom Dixon)

And so alongside making things for my own pleasure, we very quickly had work to do, making all kinds of stuff. And that’s how I learned how to be a designer, by actually making things. It’s been my reflection that practice is everything, in every profession, and possibly underestimated in design. Actually making things, seeing how they work, and making more things and seeing how they work, and then them falling apart and you remaking them is the way it worked for me. So I turned what was the disadvantage of not having a formal training in design into an advantage by just being prolific and making a lot of stuff and seeing how bad it was, and then wanting to make the next one.

SB: And over time, of course, this sort of rolls into a more professional setup.

TD: Well, yes and no. I mean professional…. More organized. I get more assistants: some people doing more welding, other people doing administration. And I open a retail shop and I try making things for industry and for Cappellini, but it’s all quite self-propelled.

And I didn’t really know enough about finance or marketing or sales or factory management—or even design actually, for that matter. So I mean, it was all self-invented. It was a time in London where it was possible to do that because rent was cheap and there were a lot of people flooding in from all over the world, in the finance sector. Most of my clients were foreigners, actually.

SB: One of the things I wanted to ask you was about your time in factories. You’ve traveled the world, spending time in India, Poland, Newcastle, Lagos, all these different factories. How do you think about this time spent? What have you learned through that time spent? And what’s kind of … not surprised you, but maybe shifted your thinking in terms of making?

TD: Well, I think it is a bit of a sad world at the moment, where a lot of traditional craft and manufacturing is vanishing. So there’s a sadness about some of the stuff that I knew and loved actually not being available anymore and not being commercially viable, actually, in a world which prizes affordability over everything. I mean, at the same time, the opposite is true, that there are so many more possibilities and opportunities and techniques that allow you to make things as well. And definitely the rise of digital manufacturing and digital methods has mirrored a bit what happens in the music industry, where you can make things from a laptop and get them printed.

“It is a bit of a sad world at the moment, where a lot of traditional craft and manufacturing is vanishing.”

Yeah, so it is a story of two separate processes. One which is the vanishing of a lot of traditions and a lot of knowledge, actually, in the craft sector. And then a reducing of the scale or an increase in the availability of high-tech manufacturing methods to the designer or the craftsmen to use for themselves.

So you’re seeing quite a big fusion even in small craft workshops or independent designers of people that are able to use very high-tech machinery to their own ends in a kind of craft way. So there might be an overlap between the two, but we’re seeing our addiction as a society to very affordable consumer goods really destroying a whole raft of really fabulous and interesting handmade possibilities that used to be local. And even the Noguchi thing [Akari lamps, produced by Ozeki & Co. in Gifu, Japan] is something which is probably on the at-risk register.

SB: Akaris are selling really well.

TD: No, I know they’re selling really well, but can you get people to make them anymore?

SB: True.

TD: Are people even interested in working in mulberry-bark paper anymore? It’s like the whole chain of the framework, the excellence in papermaking, the patience that you need to hand-make those things. If it hadn’t been for Noguchi, that would’ve died out in favor of much more mechanical means—even if people like paper lanterns in China or in Indonesia—of making those in a much more affordable, more mechanical way.

SB: I wanted to bring up IKEA here because you’ve worked with them. You’ve also, as you’ve put it, been a sort of “parasite” in terms of your relationship to working off of them. And they represent this sort of larger process, both good and bad, in terms of what’s happened in design. Also, they owned Habitat, which you were the creative director of for a decade. Could you talk about how you think about IKEA in this context, and also how you yourself have responded to that sort of fast design side of the business?

“For me, it was an enlightenment to go from being a self-producing, independent designer to jumping on being part of what effectively was the biggest furniture producer on the planet.”

TD: For me, it was an enlightenment to go from being a self-producing, independent designer to jumping on being part of what effectively was the biggest furniture producer on the planet. And a lot of my friends were like, “You cannot do that. You’re a radical; you’re not allowed to be corporate.” But I found it as the most amazing platform for really understanding all the things I didn’t know about the design, production and sales of interior products business and the scale of IKEA allowed it really to be able to do things that other companies couldn’t.

Habitat was a midget in comparison, but it was still a three quarters of a billion–dollar company with seventy or eighty stores at the time. And just working on that scale with experts in product development and logistics and marketing and finance and product development really opened up a completely new window onto the made object and gave me an insight into how most of the things in the home are made, whether that was rugs or plush toys or art prints or tableware or cookware. All of the different categories that you see around you, I suddenly had access to understanding how they’re made, where they’re made, and how much they cost, and how many of those people buy if you offer it up to them. So it was kind of a huge university of all the stuff I didn’t know about design.

I wasn’t designing; effectively, I became a creative director and was able to commission design. So I was able to work both with the young, upcoming kids that were so talented—the Bouroullecs, a variety of independent designers—but also the oldest and most vanishing of the fifties and sixties designers like Enzo Mari or Castiglioni or Verner Panton in a project that I’d called “Living Legends” until I started contacting them and they started dying on me. So I had to change the name of the project halfway through. But it was a great moment to meet some of those giants of fifties and sixties design that had such an amazing, transformational impact on the way that we furnish our homes and the way we live.

Courtesy Tom Dixon

SB: I liked learning about this other cheeky kind of pitch you had to IKEA at one point where you were basically—it was sort of redefining the idea of a life-cycle product, you were suggesting to create a project from birth to death?

TD: Yeah, I was actually being completely rational. I wasn’t being cheeky at all. I looked at the selection of products that IKEA was doing and really they didn’t do anything for babies, and they didn’t do anything for disabled or dying people, either. So that seemed like a rational business opportunity rather than a cheekiness about it. Although the idea of doing a coffin is definitely provocative in that way because people are scared of death. I’m terrified of death. But the symbolic nature of a coffin is kind of amazing. At the time, I actually bought a coffin and had it in the studio just to see how it was made and it had a chilling effect on the whole studio and I was forced to get rid of it.

SB: [Laughs]

TD: So there is something about the end of life which probably requires a bit of creative thinking. I mean, there’s a lot of activity around babies, but it tends to be very plasticky and felt like an opportunity as well. But anyway, that project was roundly rejected by IKEA, so it never saw the light of day. So yeah, I don’t know, maybe Target will do it?

SB: [Laughs] To close, how are you thinking about the future of your studio? And I ask this because you’ve previously said, and I believe this was almost fifteen years ago: “I think that’s the ideal future of manufacturing: You’re making smaller quantities closer to home, for a specific audience, and adapting to that audience’s needs.” Would you still say that now and do you see the power of the local?

TD: Yeah, I think there’s a lot of talk about it. It’s just not a unique way of looking at what we should be doing. I think the big obstruction to that is really, like I said earlier, the addiction to affordability. And that can only really happen through mass production. But the equation’s changing. So where, previously, we were always having to go to the other side of the world—that was IKEA, ourselves—to get components or to get things made. Trade barriers are coming down, wages are becoming more even across the societies anyway. As I was alluding to earlier, the manufacturing technologies are becoming agnostic to where they exist and less dependent on cheap human labor.

“It’s not that we should; it’s that we’ll be forced to buy things closer to home.”

So there’s a re-adaptation of the whole chain of events. And then, as we saw in the pandemic, the cost and the complexity of global supply chains sometimes means that maybe— It’s not that we should; it’s that we’ll be forced to buy things closer to home. So that’s a good thing.

The whole world order is never static. It’s seen a lot of very quite frightening jolts recently. And I think people need to wake up and smell the imported coffee and say, Well, in reality, what is it that we need? What can we really afford, when you look at the real cost of things? And then I do think that this extraordinary shift in technology, which is the digital sphere, can—if it doesn’t destroy us first— save us. So you’ve got this kind of battle between the good and the evil of these tools. And certainly from a design perspective, if I was starting up now, I’d have a much easier route into manufacturing, into distribution, into marketing than I ever had at the beginning. But then everybody’s got access to those tools as well, so it’s more competitive.

So I think the same as in that quote. Whether it’s realistic or not, depends on a lot of exterior levers, some of which have already come true and some of which seem really still quite distant.

SB: Tom, thank you so much. This was a pleasure.

TD: My pleasure entirely.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on May 26, 2022. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Emily Jiang, Ramon Broza, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo.