Episode 132

Thomas Keller on Cooking as a Pathway to Happiness

With one small, clever—and now-trademark—idea in 1990, the chef Thomas Keller turned not only the notion of the ice-cream cone on its head, but the fine-dining world, too. Now, 35 years later, his restaurant group comprises 10 establishments, including The French Laundry in Yountville, California, and Per Se in New York City—both of them three-Michelin-starred—as well as Bouchon Bistro and Bouchon Bakery in Las Vegas and The Surf Club Restaurant in Miami. At The French Laundry, Keller has, over the past three-plus decades, built one of the most impactful and inventive kitchens in the world. Across his entire hospitality operation, a highly refined, expertly tuned set of standards feeds his “one-guest-at-a-time” philosophy and culture.

Keller may be one of the most revered chefs and restaurateurs of our time, with his The French Laundry Cookbook (1999) selling more than a million copies worldwide, but his climb to the top of the global culinary scene has been anything but straight. With great candor and refreshing openness, on this episode of Time Sensitive Keller reflects on how it took two decades of failing and learning from mistakes before at last, in 1994, he opened The French Laundry, which was immediately praised by critics, including The New York Times’s Ruth Reichl, who hailed it as “the most exciting place to eat in the United States.” In many respects, he was at the forefront of a local-focused cooking movement. He was also a pioneer in making fine dining more relaxed and approachable—and decidedly less fussy. The food world today would not be the same were it not for his wide-spanning influence. Keller’s kitchens and dining rooms remain beacons—celebrations of the farmers, fisherman, foragers, wineries, and other purveyors who sustain them, and his teams that make the food and service sing.

On the episode, Keller discusses his recent Chef’s Table episode on Netflix and his cameo on the FX show The Bear, memory-making as a key part of his hospitality operation, and why persistence is the greatest form of pleasure.

CHAPTERS

Keller begins by explaining the “Sense of Urgency” sign that hangs under clocks in his kitchens. More than just a mantra, it serves as a philosophical attitude of progress and preparedness.

Keller considers time his greatest tool in the kitchen—not just for cooking, but for creating, ideating, and experimenting. He reflects on how carving out time has opened doors for deeper creativity, connection, and community for himself and his team.

Looking back on the 25-plus years that have passed since he first published The French Laundry Cookbook, Keller speaks about slowness as it relates to cooking and eating, insisting that dishes requiring a great deal of attention are worth the time and effort—and always will be.

Keller recalls his childhood in Palm Beach, Florida, with appreciation for the ways that his mother, then the manager of a yacht-club restaurant, instilled in him a sense of urgency and precision.

Keller notes how, when he bought and reinvented The French Laundry in 1994, ignorance was his biggest asset.

Keller takes a long view when considering his career in the kitchen and explores how memory-making, persistence, and joy have have become personal pillars.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Thomas. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

THOMAS KELLER: Thank you for welcoming me. Thank you for allowing me to come. I’m excited to be here.

SB: I thought we’d kick this off with Chef’s Table. It’s—

TK: Sure.

SB: —timely and relevant and features you in its tenth season this year. In the episode, I immediately noticed this Vacheron Constantin clock in your kitchen at The French Laundry with the phrase “Sense of Urgency” underneath it. I thought we’d start there. What do you hope to instill in the kitchen with this “Sense of Urgency” phrase on the wall?

TK: Well, the Vacheron clocks are very special. I think we’re the only people that have Vacheron clocks—and wall clocks—in the world, and I was very lucky to receive one for… Well, five for Per Se and five for The French Laundry. So those are kind of where they hang. And the “Sense of Urgency” sign is underneath all of our clocks in the entire restaurant group.

So if you walk into a kitchen or to the restaurant or into the offices, underneath the clock is, whatever the clock may be, the words “Sense of Urgency” are there. Sense of urgency is a philosophical attitude that we have on how we work or how we progress, how we are preparing ourselves for the future. This is very important for young people to understand because your ability to progress in your life and in your career is based on you being prepared for the next stage of that, of your career or your life.

For me, when I was a young cook, I worked with a sense of urgency. I wanted to work quickly, get my work done to the standard that the chef expected with some time left over so I could learn what somebody else was doing in a case of me being the poissonier and finishing my work and having ten, fifteen, twenty minutes left over where I can go to work with the saucier for that amount of time and learn what he was doing. So when the chef needed a new saucier, I could raise my hand and say, “Hey, I’m ready. I’ve been over there for the past three or four months, five months, six months, preparing myself to take over the job.”

That’s what “sense of urgency” means: preparing yourself for your future because if you’re not preparing yourself for your future, your future won’t happen. Now, what does sense of urgency feel like? [Laughter] This is interesting because sense of urgency feels like the time when you’re on freeway, and you have to use the restroom, and the next restaurant is fifty miles away. [Laughter] That’s what sense of urgency feels like.

SB: I imagine some of this also connects a bit to carpe diem. This idea of you only have so many hours in a day. Seize them while they’re here.

TK: Yeah, exactly.

SB: What does it mean to you to finally be featured in Chef’s Table? Connected to that, what impact do you think Chef’s Table has had over the past ten years on food and restaurant culture?

TK: That’s a good question. Finally… I wasn’t really waiting for anything. So it was not like “finally” for me. It was like my turn. It wasn’t something I anticipated or something that I sought or anything. I mean, Chef Table came ten years ago, and I think I saw a couple of episodes.

I don’t really enjoy watching food shows, so I didn’t spend a lot of time with Chef’s Table. I know that they’ve done extraordinarily well. They’ve won many Emmys. Many of my friends and colleagues have been on the show. In fact, I didn’t watch Grant [Achatz]’s episode until just before we did my episode, just so I could kind of see what it was like for him.

SB: His quotes, by the way, about your work are just—

TK: Very nice, very generous.

SB: Yeah.

TK: It wasn’t really something on my radar. I don’t necessarily migrate towards television or interviews, for that matter, although I’m expected to do them, and I think I’m pretty good at it. I’m always apprehensive, and it’s always awkward for me to see myself, hear myself, or even read about myself in anything. It just doesn’t feel quite right for me. So I’m not… that’s not something that I’m trying to do a lot—and obviously, because I’ve never been on a lot of television shows.

Bobby Flay or Tom Colicchio or Emeril [Lagasse], they migrate to that, and they’ve done it really, really well and have influenced so many young cooks, and not just in the profession, but outside the profession as well. I think all of it is great stuff, right? What they’ve done, I think what Chef Table’s done or any of the food shows have done have really influenced generations of people, whether they’re consumers, whether they’re hobbyists, or whether they’re professional chefs. It’s all good for the profession and good for America.

In this case, you see these things migrating around the world. All of this didn’t exist when I started cooking. So my history wasn’t about that. My reasoning for cooking had nothing to do with becoming famous or wealthy. It was more about the nurturing of people was the reason I became a cook. If you went home to tell your parents that you were going to be a cook in 1975 or ’76, they would label you a loser. “What? Are you kidding? You can’t do anything better than being a cook?” Because cooks back then were like, you consider it was like a short-order cook. Yes, there were some great restaurants in New York City, obviously, all the La, Le restaurants. I think Le Pavillon, the first one, opened in 1941. You had the World’s Fair here in 1936, I think, which really kicked off that whole French chef migration to New York. So you look back on that, and you understand where we all came from in certain ways, but it wasn’t something where there were droves of young Americans trying to be chefs during that period of time in our history.

SB: I have to bring up The Bear here. You were on Season Three, Episode Ten. What was that experience like?

TK: It was great. I mean, I know Christopher Storer, who we… We hired Christopher in 2014 to direct a documentary on our restaurants, twenty-four hours in the life of our restaurants. [Editor’s note: Sense of Urgency, the short documentary directed by Christopher Storer, was filmed and completed in 2013.] So he went to all of our restaurants and filmed, and then, of course, edited to a point where you had seventeen minutes featuring all the restaurants throughout the entire day from the morning until the closure of most of the restaurants. Hans Zimmer actually did our music for that, which was great. So I’ve known Chris since then.

When The Bear came out, I was really like, Wow, this is great. Super happy for him. He has a show. He’s directing, he’s producing it. I mean, he’s writing it, he created it, and I love that when people that you know, and even if you don’t know, become successful in the profession that they’re working in. I never expected to be on the show. It wasn’t something, once again, I’m not trying to be on The Bear. I didn’t call Christopher and say, “When are you going to put me on?” He asked, I think towards the end, or when he was developing the third season, he called me and said there was a piece about roasting chickens, and Jeremy [Allen White] was going to roast a chicken for his mother, and that was kind of the premise behind it. There was no better person than me to do the roasted chicken because the roasted chicken from our restaurants and from Bouchon and the roasted chickens I’ve done on YouTube have been very popular.

So I said, “Of course, why wouldn’t I do that?” The day came, and there wasn’t really a lot of preparation for it. He sent me what Jeremy was going to say and what was going to do and kind of the scene, if you will, but there was not a script for me. He just said, “You be the person you are. Just say what you would normally say to a young person who’s in your kitchen and just starting.” So that was the conversation and we did it in forty-five minutes. It was one take and we were done and I was back to work in the kitchen. So it was all over. I am very grateful and blessed to have had the opportunities to do things I’d never thought I would ever, ever, ever, ever do and to be part of things that I never thought I’d be part of. So yes, I’m not going to necessarily turn them down, but it’s not something I searched for.

SB: Right.

TK: The Bear was fun. I got a hat, which was really nice, and I got to see Christopher again and work with him again. It was a nice kind of reunion, if you will.

SB: Turning here to the subject of time, you’ve written, “I’ve realized that of all the tools of refinement, time is the greatest—having the time to refine and refine and refine. I’ve managed to create more time by opening the kitchen up and adding more chefs. When you’re rushing to be ready for service, the final refinements sometimes get lost. Time is the ultimate tool.” Could you talk to me a bit about your philosophies on time? How do you think about it in your life and work?

TK: It is fascinating. I mean, we’re all thinking about time throughout our lives, and certainly, we focus on it more and more as we get older, right? How much time that we’re spending on things, and what’s the important things that we really want to spend time on? For me, as a young cook, I was really impatient, as most young cooks are. We always want to do the next thing before we’re ready to do the next thing. So I’m always advising young chefs to be patient. Be patient with your career. This is a moment in time that you’re doing this specific role.

One of my best times as a young cook was working on the line with three or four other cooks or five other chefs de parties. That’s kind of when you are on the playing field. I’ve always associated my profession with sports franchises. It’s really important to realize that that’s when you’re playing the game, when you’re actually cooking food. You become a sous chef. It’s different. You become a chef, a CDC—a chef de cuisine—it’s different. You become an executive chef. It’s different. So enjoy those moments when you’re actually doing the job that you … that you’re doing the job that you always wanted to do. The reason you became a cook was to cook. So, be patient with your career. Enjoy the moment while it’s there, spend the time doing it around the stove because once you’re done, it’s hard to go back. That’s a really important aspect about what I’m trying to get my younger team members to understand: time. It’s not just in the kitchen. It’s also in the dining room. I mean, every young person in any profession wants to be … wants to move up as quick as they can. Sometimes it takes time [to] appreciate those moments.

Time for refinement is just that. It’s time to be able to reflect and think about things, and it becomes more and more difficult when we have more and more distractions in our lives. I mean, I hate to say it, but this is kind of a distraction. I could be in the kitchen, right?

SB: Sorry, Thomas. [Laughs]

TK: No, no, it’s okay. But this is what happened, and this is now part of our profession and part of our responsibility as chefs. I mean, this didn’t happen last generation. This was not something that chefs did before. My generation began this in America. You look at the last generation in France, yes, there was that kind of interaction between media or marketing or those kinds of things. But in America, I’m part of the first generation of American chefs. This was all new. I appreciate the position I’m in, and I’m trying to be responsible to sharing, having conversations in and around my career, my profession, and what I’ve learned throughout this forty-seven years of being part of the hospitality profession and the restaurant profession. It’s a wonderful thing that when we would sit down at The French Laundry in the first twelve years when I was actually part of that team and sit down at the end of the night and talk about what we were going to do tomorrow because the menu changes every day.

Those moments were the moments that we would set up the idea of what was going to happen tomorrow, and then we would come in and start to execute it and refine it as we went. That was really a fascinating process. I’m not sure any other restaurant does that, but we could plate the rouge going out on the first table and refine it for the next table. That’s how dynamic we were, how flexible we were, because we were always thinking about what is it we can do to make it better, to improve on what we’ve just done. That could be from one table to the next. That’s how quick we could be. That’s really a luxury because in most restaurants, they don’t… the young chefs de parties aren’t really part of that. They don’t have any influence over what the dish looks like or the composition of the dish.

At French Laundry and Per Se, we always had that interaction between chefs de parties, sous chefs, chefs de cuisine, and/or myself. That sense of refinement was quick sometimes. Other times, we would think about it over a period of the entire year, thinking about the asparagus coming in the springtime. We would get excited when the asparagus came back because we would revisit what we did the year before and refine it. The sense of refinement is not just about a moment. It’s about a specific technique or specific ingredient, a specific plate with all these different moments of refinement.

SB: This approach really makes me think of this piece I read preparing for this from The Wall Street Journal a few years ago. You noted in it that you have an allergy to brainstorming, and you’re quoted as saying, “If you try to set time aside for that, you’re actually trying to force something that may not be ready to appear or reveal itself.” For you, it really seems like it’s like this. You’re doing it in the act. It’s actually… But I should also note here that, and the piece notes this too, that you have daily 7 a.m. and 3 p.m. meditation sessions.

TK: Yep.

SB: So I definitely agree with you that you can’t force true creativity. It is really about being open and letting it come when it calls you.

TK: Mm-hmm.

SB: Being in the moment.

TK: Creativity is an interesting word because you have to really question the idea: Do we really create anything? Everything’s here. There’s nothing new on earth. Creation’s a difficult word for me to embrace, yet I understand how it’s used. I think that there’s moments in my life where I’ve been strongly influenced and “created” something that had not been done before in that way. The cornet is the perfect example, right. I mean, yes, it’s an ice-cream cone. That’s what I saw. I saw an ice-cream cone at Baskin-Robbins. That influenced me to do the cornet. Was it creation? No, I don’t think it was a true creation, but it was certainly something that had never been done before. That in and of itself gives this idea of something that Thomas Keller created this cornet. That’s fine, and I’ll take the credit. But when someone says to you, “What are you going to create tomorrow?” It’s like, “Really? Who knows? What does that mean? How does creation work?”

It’s really about being aware of the world around you, of having this sense of awareness so that when there’s something happens in your life that influences you or inspires you—that’s another word, inspire… inspiration, right? It’s interesting because, yes, I mean, I was sad. I was depressed. I was leaving the city here, New York City, that I love so much, and I had to do something in L.A. that was going to wow the Angelinos. I had no idea what I was going to do, but the young girl put the ice-cream cone up there, and I immediately saw that. So I was aware. I was aware from what was the pressure on me at the moment, what I was going through, what I had to do, and I saw something different that day. You do the same thing. We all do the same thing. We could be walking down the street and a leaf blows across the street, and that can influence you to do something different. Poets do it. Artists do it. Everybody is influenced by things that they see and interpret that. Interpretation is the second thing.

The awareness, influence, inspiration, interpretation, interpreting is something that’s meaningful for you and whatever it is, whatever you’re doing, that’s an important thing. Then the last part, the last word there is evolution. How does that continue to evolve over time? You do it based on what you first saw, but how do you continue to improve it day after day?

Sometimes improvement is a hard thing to do. The cornet has been improved over time, but it’s still the cornet. The Oyster and Pearl, which is another very famous dish that we do at French Laundry and Per Se… We’ve tried to do the Oyster and Pearl 2.0 and it failed every single time. So it kind of just stays the same. The same preparation we did thirty-two years ago, it’s the same. The dish may be different, a little more refined.

SB: That’s the new. Some things are meant to say the same.

TK: Yeah, yeah.

SB: Some things can…

TK: Then the problem is that then people kind of criticize you. Like, “What? He’s been doing that thing for thirty-two years. Can’t he think of anything else?” Well, it’s like The Rolling Stones. I mean, Mick Jagger gets up there and sings “[I Can’t Get No] Satisfaction” every time he goes to the concert because why does he sing “Satisfaction”? Not necessarily because he wants to, but everybody that’s there in the audience is expecting him to sing “Satisfaction.”

SB: It’s the cornet.

TK: Yeah. Exactly.

SB: It’s the ice-cream cone.

TK: If he doesn’t do it, they’re like, “Shit, what happened?”

[Laughter]

SB: Well, in Chef’s Table, you say, “If you’re not having fun, then what’s the point?” And it’s interesting because it reminds me of—this is just a funny, nineties, growing-up-in-America childhood memory I have, but my dad had a bumper sticker on one of his cars that was a Ben & Jerry’s quote, and it said, “If it’s not fun, why do it?” I was laughing thinking about that in the context of your journey with this ice-cream cone becoming the cornet. I mean, it is ultimately about fun, or even, to quote the Stones, “satisfaction.”

TK: Yeah. The basis of cooking is to make people happy. That’s what we need to do, right? So many chefs get caught up in other reasons why they’re cooking it, forget that they’re nurturing their guests, nurturing their team, nurturing those individuals that bring us our food, our farmers, our fishermen, our foragers, our gardeners. That’s all a part of the nurturing cycle that goes on in our lives, in restaurants’ lives. Whatever we can do, whatever I can do to lighten somebody’s experience at the restaurant and make it more fun, then that’s what I’m going to do because we want to have fun as well. In the kitchen, if we’re not smiling in our kitchens, then we’re not having fun either.

In some ways, it’s a very serious business, but in other ways, it’s also an experience that we have every single day. We eat every single day, two, three times a day. So it can’t be so serious that we forget the purpose of what we’re doing. It’s to nurture one another.

SB: There’s this element of thinking fast and thinking slow, and somehow fun rears its head in between. I did want to talk about slowness because your practice to me embodies that. I was going through The French Laundry Cookbook from 1999, and in it, you write, “Our hunger for the twenty-minute gourmet meal, for one-pot ease and prewashed, precut ingredients has severed our lifeline to the satisfactions of cooking. Take your time. Take a long time. Move slowly and deliberately and with great attention.” I mean, this is 1999, so we’re now here almost, what, nearing thirty years later, what do you think about that quote and also just this notion of slowness in your work now that you see it over these four, nearly five decades now?

TK: Yeah, I think we’ve grown in our culture to want things quickly, and I’m not sure why. Think about the panini, right? I mean, somebody went to Italy fifty years ago or whatever, sixty years ago, and they had a panini, and the panini was made to order, and it was put on the panini grill, and it took five, six, seven minutes to grill. And they had this wonderful experience with panini. Now you come to… They bring it back to America, and it’s all the rage. Now, at Bouchon Bakery, for example, we do a panini, and they want it in a minute and a half. It’s like, “Well, how can you do that?” Well, they’ve created this microwaves out of the griddle. I mean, it’s a whole different kind of piece of equipment that will produce a panini in a minute and a half. Is that truly a panini? Can’t we really wait for seven minutes to experience something that is more true to the origin of the panini?

It’s just sad to see that we’ve taken some of these wonderful experiences around food, modified them to a point where we get them quicker, but [have] diminished the quality of them so greatly that we don’t even recognize what it is. Now, maybe the person has never been to Italy, so never really had a real panini. So yes, to him, that’s what it is, and that’s redefined what we have.

I remember one time I was in London, and I did a food show there. There were two chefs. At the end of the show, there was a contest like, who could make the omelet the quickest. I’m thinking, I watched Daniel Boulud do it, I think, on some video. Maybe it was YouTube, and it was a total disaster when he was trying to cook an omelet in thirty seconds. [Laughter] I’m thinking, “Why are we doing this? Why are we telling our viewers that they can cook an omelet in thirty seconds or forty-five seconds or whatever time it is?” It gets towards the end of the show, and I’ve got my mise en place underneath my little cook station, and he says, “Go.” I turn the fire down really low, and I bring out my mise en place, my omelet pan, my eggs. I started saying, “If you don’t have seven or eight minutes to make an omelet in the morning, then don’t make an omelet.” [Laughter]

He’s standing behind me because now he has a timing issue, right? He needs to complete this segment in a minute. He’s kind of kicking me from behind going, “Thomas, you got to move. You gotta move.” This is the process of making an omelet. So just take your time because you’ll be so much more satisfied than trying to do it quickly.

I think those things we kind of get confused on around food. What is a preparation for food? It’s progression. You start here and you end there, and there are specific steps that you have to go through for the result to be something that you’re going to really enjoy. That only happens if, you know… if you have experience with the dish prior.

SB: The relationship between time and taste is so fascinating. I think we could unpack many of your—

TK: Yeah, I know.

SB: —dishes through time and taste. I mean, I love how you’ve talked about French onion soup—leave it overnight.

TK: You’d have to. Maybe two nights. maybe.

SB: Yeah. Or some of your dishes. There’s the meat one where you bake it for five hours inside of dough.

TK: Yeah. Yeah.

SB: I mean…

TK: We’ve become short-order cooks in many restaurants, right? Cooking a piece of meat, cooking a steak, or cooking a piece of fish, it’s just all sautéing, pan-roasting, quick, quick, quick. The things that I love are like a daube de boeuf, which takes three days to make, because then you really kind of understand the transformation of food. It’s that transformation of food that gets me so excited. Yes, I can grill a steak in five minutes, and that’s fine, and I’ll do that when I want a steak like that. But the actual transformation of food, making tripe or those types of things, which are really… Or even the transformation of a chicken, roasting a chicken, and understanding how to do that well.

SB: Let’s go back to your upbringing here. You were born at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California, the youngest of five boys. Your parents divorced when you were young, and your mother raised you while managing a restaurant called the Redwood Inn in Palm Beach, Florida.

TK: Yep.

SB: Around 15, you started working for her as a dishwasher, sort of a night gig, I guess. After high school, your mom put you in the chef seat. Your brother Joseph taught you some basic cooking skills. We could definitely dig deep into your childhood, but I wanted to ask just with hindsight how you think about your mother’s influence on your life in the kitchen and the impact on you becoming a chef that she had.

TK: My mother’s influence went way beyond the kitchen. [I was] the youngest of five boys—two of my older brothers had already left the nest, so to speak. I had a half-sister, and it’s funny because I [got] two half-sisters when my parents remarried. Well, they had four, five boys together. They each had a girl with their new partner. So there were three and a half of us at home because my third oldest brother was in and out.

My older brother Joseph always wanted to be a chef. He would come home from school at 13 or 14 years old and turn Graham Kerr on if you remember The Galloping Gourmet. He had all of his cookbooks. I was kind of a lost soul. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I didn’t have any… I had the hobbies. Yes, I played baseball, basketball, football, things like that. But there was nothing that piqued my interest enough to continue to pursue that like my brother. My mother gave me a great sense of awareness, attention to detail, a sense of work ethic that began when I was 6 or 7 years old. Part of that was she did work at night. My older brothers did take care of us for a period of time, and we all had chores to do, and I had to do not only my chores but my older brother’s chores as well because they forced me and my brother Joseph to do their chores. So, understanding the sense of urgency, getting the chores done in time, understanding the standards that they had to be performed because my mother came home and [if] the vacuum cleaner wheels weren’t on the carpet correctly, perfect lines that she would be upset with us. So that was something that my mother gave me was a sense of urgency.

SB: And precision, it sounds like. [Laughs]

TK: And precision. Exactly. Sense of awareness, right.

SB: Yeah.

TK: Work ethic, these kinds of things. I just took that into my life, and it’s still part of it. So, my mother being really my first mentor, as many of our parents are, right? Your mother, your father, they make decisions for you, and they’re your mentors and help you find your way and hopefully give you the right direction to actually discover the way you want to go, and that was my mother.

Even though I wasn’t interested in becoming a cook, to keep me out of trouble, she put me in the kitchen washing dishes. Years later, I realized [that] the six disciplines I learned washing dishes helped me become who I am today. My brother always kind of got to be with the cooks, and I stayed at the dishwasher. She was running a small private club in Palm Beach called the Palm Beach Yacht Club, which was basically a lunch place for local businessmen who weren’t very adventurous about food. The most adventurous that they were was maybe eggs Benedict. So learning how to make hollandaise sauce for my brother Joseph was critical. But other than that, grilling hamburger, making an omelet, grilling flank steak. It’s fascinating because if you just look at sourcing food then—when I started—and sourcing food now, I had two people to go to source everything. I called my baker every night to order the bread and one other company to order everything else, from chemicals to vegetables, to placemats, to anything. It was all coming from one person.

Now, of course, today, it’s much changed. But that’s kind of where it began for me. I wasn’t really interested in cooking, although I started doing it well. I could multitask. I paid attention. I can replicate what I was taught fairly quickly. But the Yacht Club was challenging in many ways, but nonetheless, I was able to excel there. Most importantly, it gave me the opportunity to travel because you can go anywhere and get a job as a cook.

SB: I wanted to sort of unpack your journey from there, but in the interest of time, I thought I would try myself to lay it out here for the listeners. I’ll see if I can do it justice.

TK: Sure.

SB: After working for your mom’s restaurant, you entered a period of, as you’ve put it, “two decades of failing.” [Laughter] This journey begins more or less with a summer job at The Dunes Club in Narragansett, Rhode Island, where you’re working under this French-born chef, Roland Henin, who became your mentor.

TK: Mm-hmm.

SB: Then you work as a failed chef and owner of a restaurant called the Cobbly Nob in West Palm Beach. [Laughter]

TK: Right next to the jai-alai fronton by the way.

SB: I just love the name the Cobbly Nob.

TK: I know, yeah.

SB: Then you go to another job at Café Du Parc in North Palm Beach [editor’s note: Café Du Parc is actually located in West Palm Beach], then to three years as a chef of a sixty-seat restaurant near Catskill, New York, then to an assistant chef job at the Grand Hyatt in New York, which lasted for ten days?

TK: Probably, yeah. [Laughter] Wasn’t my thing.

SB: Then to a chef job at Raoul’s in SoHo in New York, and after that, to Maurice at the Parker Meridien Hotel. Then to a poissonier, or fish cook, job at the Polo Lounge at the Westbury Hotel, which was being helmed at the time by Patrice Boëly and—

TK: Exactly.

SB: —Daniel Boulud.

TK: Yeah.

SB: From there, you went to Paris for a year, working in half a dozen two and three Michelin-star restaurants. Then, in 1985, you became the chef and a partner of the restaurant Rakel in Manhattan. This is when you get your first big reviews.

Florence Fabricant wrote in The New York Times, “What makes Keller notable in a city that’s well populated with talented cooks are his daring flights from the ordinary. A few of the items on his menu even verge on the bizarre.”

TK: Oh, wow.

SB: Adding, “Keller’s solid foundation in classical French cooking elevates his dishes and saves them from absurdity.” [Laughter] But by 1990, Rakel too was gone, and soon enough, you find yourself in downtown Los Angeles, which you were talking about earlier, the cornet, where you’d gotten this job as an executive chef of Checkers. You stayed there for a year. Next, you left the restaurant world for eighteen months, and began making olive oil commercially.

TK: Yes.

SB: That’s where I’ll leave the story. I’m glad I was able to sort of unpack your early résumé there.

TK: Yeah, you did. I mean, obviously, you condensed it a little bit. [Laughter] There was a couple of little things in there, but yeah, that’s a really great summary of my life up until that moment in time where, when you say I left Checkers, I mean, I was fired from Checkers. I’m not afraid to say that. It was okay because I wasn’t enjoying the job. I was a chef de cuisine. I was the executive chef there, but I’m really a chef de cuisine of a restaurant?

At Checkers, as an executive chef, you are responsible for everything. Breakfast, lunch, dinner, room service, banquet, staff meal, amenities, all the different things, and I didn’t really migrate very well to that type of job. So the manager came in one day or invited me to his office and said, “You’re out of here.” And I left. Funny enough, though, I met his wife because they lived there for a little while, and I got to know them. Fast-forward ten, twelve years, and his wife runs up to me. I was doing an event somewhere, and she said, “I need you to meet somebody.” And I did. I met the person that she wanted to meet, and I invited her and her husband to dinner. This is the gentleman that fired me twelve years earlier. When he was coming back to the kitchen, I said, “Great to see you. I just want to thank you because had you not fired me, I would not be here today.”

You think about the significant decisions that are made for you and the significant decisions that you make yourself. That was a significant decision in my life when he fired me that propelled me to find another path. I needed to find something else to do. Yes, I was out of the profession for quite some time before being able to open The French Laundry. That was probably a little more than two years. That was a significant decision, just to buy The French Laundry without any resources at all. I had no money. I had no job. I didn’t have the skill, the knowledge, or the experience to actually buy a restaurant and do the things I had to do. But Don and Sally Schmitt made a significant decision for me and said, “We’re going to support you through this process.” Eighteen months they supported me through the process, and I was truly blessed to have their commitment to what I wanted to do with their restaurant when they left.

I always say my biggest asset at the time was my ignorance. If somebody had laid out for me in a list of all the things I’d have to do to buy the restaurant, I would’ve said, “This is impossible. I can’t do any of these things.” Maybe a couple of things, but most of them I couldn’t do, and therefore, I would’ve given up from the very beginning. But it was the ignorance and the little successes along the way that continue to propel you forward. It is like golf, for example. I mean, you hit one good shot out of ninety shots, and you’re like, “I’m going to play golf again,” because you have some success, and you feel that success to motivate you and motivate you in strong ways [to] continue to persevere and do the things that you don’t think you can do or couldn’t do before. You realize that you can do anything that you want if you really put your mind to it—if you put the effort behind it. If you’re determined and committed, anybody can do anything they want. I sit here today because of that, not because I was smarter or a better chef, or… I was just persistent. I was not going to let that opportunity pass me by.

SB: You also had the wonderful bounty of Napa Valley and Yountville, California. I would say also the time in which this was occurring was also really important, especially from a food perspective. The definition of fine dining was changing, and you were a big part of that. You got to kind of create all these inventive high-low dishes that I think really would push it over the years.

Here I’m talking about Per Se, too, and your other restaurants. I mean, some of these dishes include Tongue in Cheek, comprising braised beef cheeks and veal tongue and baby leeks and horseradish cream; Oysters and Pearls, as you mentioned earlier; Bacon and Eggs; Coffee and Donuts. I mean, you’re serving this at a fine dining establishment. You even did a PB&J out of slow-poached Hudson Valley foie gras, Concord grape gelée, peanut brittle celery branch, and Kendall Farms crème fraîche.

TK: Yeah. Yeah. Don’t forget macaroni and cheese. [Laughter]

SB: And steak and fries.

TK: Being an American affords you the opportunity to actually bring these things back and reinterpret them in different ways. We found that to be a path forward for me. And we had fun. It wasn’t me who was developing all the dishes. The great thing about The French Laundry is the sense of collaboration. Anybody can have an idea and share the idea, and we let people share their ideas, which doesn’t typically happen in a restaurant.

SB: I wanted to ask you about The French Laundry kitchen because, obviously, from a time perspective, that’s also so interesting. There were multiple iterations of the kitchen, the most recent of which was this major overhaul in 2017, where you worked with the architecture firm Snøhetta. This eleven-million-dollar kitchen renovation, or at least that’s what I read in The New York Times.

TK: Yeah.

SB: All the details that went into making that kitchen—it just reminds me of even the precision you were describing of vacuuming your mom’s floor, right? Everything was done for a reason.

TK: Mm-hmm.

SB: Could you talk about that? How the design impacts the culture, impacts the food, sort of beginning with the smallest detail and then finding its way to the plate, basically?

TK: You just mentioned that everything has a beginning point and an end point. And the end point is giving our guests this experience, both in food and service and wine, all these different things. But the beginning of that really is manifested in where we are, who we are, and what we’re able to do. That is the fifth kitchen of The French Laundry. The first kitchen was Don and Sally’s kitchen, which was my kitchen for the first year when we built the second kitchen, which is on the same site as the fifth kitchen. So that was the second kitchen. And the third kitchen, when we opened Per Se, there was… We blew up that kitchen and redid the whole thing for the third kitchen. The fourth kitchen was the temporary kitchen [when] we were building the fifth kitchen. For two and a half years, we worked out of three, I should say, four shipping containers that were modified and put in place to accept the equipment that was in the third kitchen where we built the fifth kitchen. We’re already in plans for the renovation of the fifth kitchen because we always realize that we can do better.

That’s always… It’s a curse. It’s a double-edged sword. Why can’t we just be satisfied with what we’re doing today? Why do we always have to search for betterment? That’s just the way I am, and therefore, that’s our culture, and that’s what we do. This is also when you think about where we were before… The generation before me in America, chefs didn’t really run their restaurants. They didn’t own restaurants. So the kitchens weren’t necessarily acceptable, if you will, or appropriate to work in as they are today. So making sure that we, as chefs who own our own restaurants, are not only spending time on the dining room, making sure that that is comfortable as it needs to be, but making sure the kitchen is as comfortable as it needs to be, has the resources that it needs, has the equipment that it needs, has the space that it needs for us all to be able to work comfortably. There were times in The French Laundry kitchen when it wasn’t comfortable.

Before we did the renovation in 2004, we didn’t have air-conditioning in the kitchen. I mean, it’d be a hundred and ten degrees working in the corner, and it was really difficult, but it was almost also a norm, right? It was normal to actually work in a kitchen like that. We realized we needed to make a better environment for us. And so the new kitchen represents a wonderful environment with enough space for all of us to work. The right equipment for us all to excel at what we’re doing.

And the attitude of the team that comes into that, into the kitchen, both dining room and kitchen team, is one that is uplifting, right? They’re proud to be in the kitchen. They’re happy to be in the kitchen, and that’s the way it should be. Most people who go home are happy to be in their kitchen. And so trying to establish [the] same vernacular that we have at home, this idea that there’s a front and back of the house in restaurants, that’s just weird to me.

SB: Kitchen and dining room.

TK: Exactly. It’s like if I go home and there’s a kitchen and dining room. Why in the restaurant is there a back and a front of the house? It’s just wrong. So we work on those things and trying to redefine who we are and how we work, and it’s an important way to accomplish it. The new French Laundry kitchen was actually built to accept more guests in our kitchen, so there’s more space for the guests to actually come in the kitchen and hang out for ten, fifteen minutes, or five minutes to take a visit. That’s something that Sally had done from the very beginning. She’d always invite guests back to her tiny kitchen. We just kept that tradition going. Today, it’s part of the experience for the guests to come in, have dinner, come into the kitchen, say hello, take a picture, or whatever. Just hang out for a few minutes just to see how a kitchen operates.

SB: I want to talk about longevity—well, longevity and pleasure, I suppose. You’ve written, “To give pleasure, you have to take pleasure yourself. For me, it’s the satisfaction of cooking every day … the mechanical jobs I do daily, year after year. This is the great challenge: to maintain passion for the everyday routine and the endlessly repeated act, to derive deep gratification from the mundane.”

I mean, this is time in the kitchen, and in the Chef’s Table episode, you say, “The ritual of doing the same thing, over and over again, and getting really good at it—that was magical to me.” But maybe more to the point or a different way of phrasing the question would be, is persistence the greatest pleasure?

TK: I think the result of your persistence is the greatest pleasure. To see a guest that has that joy and the experience because that’s what it’s all about. The word delicious is such an important word for me. People say, “Oh, I had this amazing meal. This extraordinary meal.” Yes, but was it delicious? I mean, that’s what I want to…

SB: Did it taste good?

TK: Right. I want somebody to come back and say, “Wow, that dinner was delicious.” That’s all I need to hear because then you know you’ve made that person happy. You know you’ve succeeded in your quest. You know you’ve working with the ingredients and the farmers and fishermen and foragers and gardeners that are bringing you those ingredients and representing those in the way that gives pleasure to a person and nurtures their body and their soul is so, so, so, so fundamental in the way I believe the way we work—and that’s a beautiful thing. So I’m not sure I’m answering your question, though.

SB: [Laughs] Well, I mean, I think it’s really this idea of longevity through the lens of the repeated act, the ritual.

TK: Going back to the analogy of a sports franchise, we’re athletes when we walk in the kitchen. We become a comme. We’re the rookies, and if you’ve been hired or you’ve been recruited to be part of this team because of qualities that you represented, but you have to learn everything along the way. You’ve never played at that level before. As you grow and as you succeed, you become a chef de partie. So now you’re part of the team on the field. That’s why I said earlier, that’s the moment in your life, which is one of the most gratifying moments of your life at that period of time, and enjoy it because you are part of that field team. Then you become a sous chef. Now you’re managing other people, and that’s a hard transition from being one of the guys to actually managing the guys because they look at you differently, and you have to look at them differently. You have to have this opportunity to actually mentor, to lead them, to criticize them, to celebrate them—all the different things that a leader needs to do. Then you become a chef de cuisine, and now you’re running the entire kitchen, not just the section of the kitchen. So you’ve moved yourself away.

As you go through your career, and if you look at sports, you have the rookie, the field player, then you’re the manager, the field manager, or one of the field managers, then you become the general manager, then you become the owner. Finding success at each level, at each interval, at each era for me has been my biggest quest is making sure that I can continue every day to have an impact on the youngest team members that are there, all the way up to the chef de parties, the sous chefs, the CDCs. Even in the dining room, the same thing, right? To influence the young individuals that are coming in, the service staff, it’s a wonderful thing, to watch the transformation that they go through.

A young kid coming in as a runner, which is one of the first jobs, who doesn’t really understand a kitchen, doesn’t have the confidence, doesn’t have the vocabulary, and six months later, their fathers are coming to me, their parents are coming to me saying, “I can’t believe the transformation that’s happened in my son or my daughter working in this restaurant.” You think about that, and you go, “Shit, that’s pretty cool.” Because you’ve given this young person the opportunity to transform themselves into something different. And they find joy in that. We find joy in that. So when you think about a restaurant, yes, we all think about a restaurant, it’s a place to go to eat and drink. But a restaurant has so much more that it gives to so many people. That’s something that excites me. Yes, our ultimate goal is to feed our guests and give them delicious food. But everybody that’s involved in that and how they learn, how they are transformed… I’m really proud to be able to be part of that.

SB: You mentioned success, and I love your definition of success. In a TED Talk you once gave, you linked success with memory, saying, “One of the biggest compliments I can receive is when a guest comes to our restaurant, has dinner, and I meet them, and they say, ‘This reminds me of…’” In your French Laundry, Per Se cookbook, from 2020, you define fine dining, in a sense, as “memories that only expand with time.” I was hoping in the time we have left, that you could elaborate on the importance of memory-making for you, this link between success and memory, and this intersection of time, taste, and place.

TK: I think we’re all searching for memories, for experiences, I should say. We’re all searching for those experiences that result in a wonderful memory. And sometimes, a wonderful memory could be a disastrous experience, but it turns into a wonderful memory because you’ll actually live through it. We, as individuals, I believe, we continue to deposit in our memory banks these wonderful moments in time throughout our life that really make us rich. It gives us the sense of enjoyment, like, “Oh my goodness, remember that? Remember this?” Then there’s the reference points that are also established around memories, like my memory of my first roasted chicken. So everything that is associated with roasted chicken for my entire life is based on that, that first memory. Yes, I’ve had better roasted chickens than the first one, but that’s the reference point that you begin with.

SB: What was your first roasted chicken?

TK: My mother’s roasted chicken, which wasn’t really… My mother wasn’t a cook, by the way. So she tried, but she didn’t practice it very often. I think memories give us a sense of internal wealth that can’t be replaced by anything else. That’s what I search for—those memories. Giving people memories is memorable for myself.

People come in the restaurant. Like I said, this experience reminds me of a great memory that they had. And it’s like, “Oh, my God, I remember those. I remember what they say.” We’re exchanging these moments of time throughout our lives that intersect with others. Some people we know; some people we don’t know, but [it] enriches our lives and enriches their lives. That’s really what success is all about.

SB: Not to end on a macabre note here, but I was fascinated to learn that you cooked your father’s last meal.

TK: I did.

SB: Which was barbecued chicken with mashed potatoes and braised collard greens. What did it mean for you to do that? How do you think about the notion of a last meal more generally? I think it’s fascinating that in the cycle of life, or even in thinking about religion, the last supper does seem to play this oversized role.

TK: Obviously I didn’t know it was my father’s last meal. It was a Sunday afternoon. He’d become a quadriplegic about a year before that, [in] a horrific accident. He persevered to find ways to do things that he did before. And the doctor said he would never eat again, like that. So inviting him over to the house and making him that dinner was a Sunday afternoon. It wasn’t a ritual, but we would do it occasionally. Then, of course, the next day is when he passed away. You don’t realize it, but the idea of it, the idea of the composition, the barbecued chicken, the mashed potatoes, and the collard greens were things that he loved, and that all of those had reference points in his life. We finished with strawberry shortcake, by the way, which, again, coming from his time, strawberry shortcake was such a luxury in life. He was born in 1918. So think about fresh strawberries and having it on a piece of cake with whipped cream. That was the cat’s meow, as he would say.

Those are the moments that we experience, and those are the moments that I, once again, I’m grateful for. Not many of us get to spend the last moments with our parents. To be with him when he passed was an extraordinary moment in time for me. Extremely sad. Even though you think you’re prepared for your parents’ passing, you never really are until it really happens. Then it’s still extremely, extremely sad. But we all go through it. Our parents are supposed to pass before us. That’s the way life is. Appreciating those moments is what we have to do, and appreciating where we came from and who was part of our lives, who brought us into our lives, who influenced our lives, it just becomes much more focused when your father or your mother passes away.

SB: How beautiful that you got to give your dad this sense of fun and joy and memory, honestly—

TK: Yeah, yeah.

SB: —at the end.

TK: Yeah.

SB: Well, Thomas, thank you.

TK: Thank you.

SB: This was a pleasure.

TK: I appreciate it. Thank you for having me, and I’m grateful to be here.

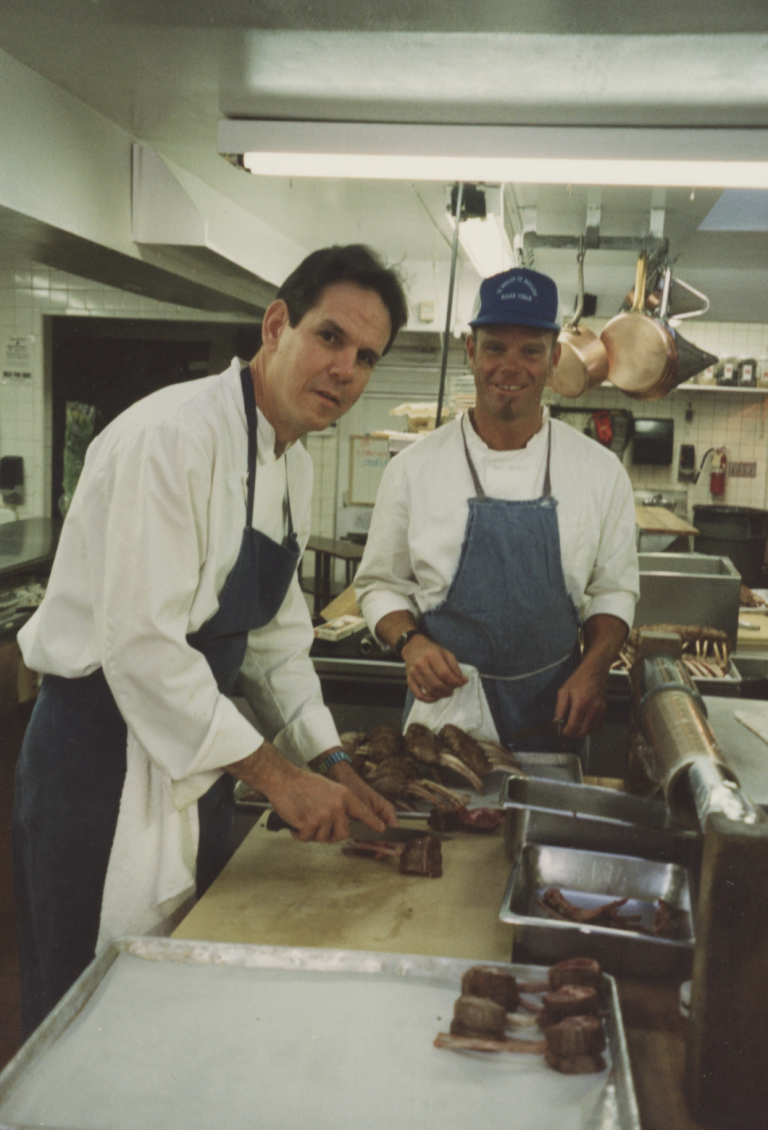

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on April 25, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, Kylie McConville, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Deborah Jones.