Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

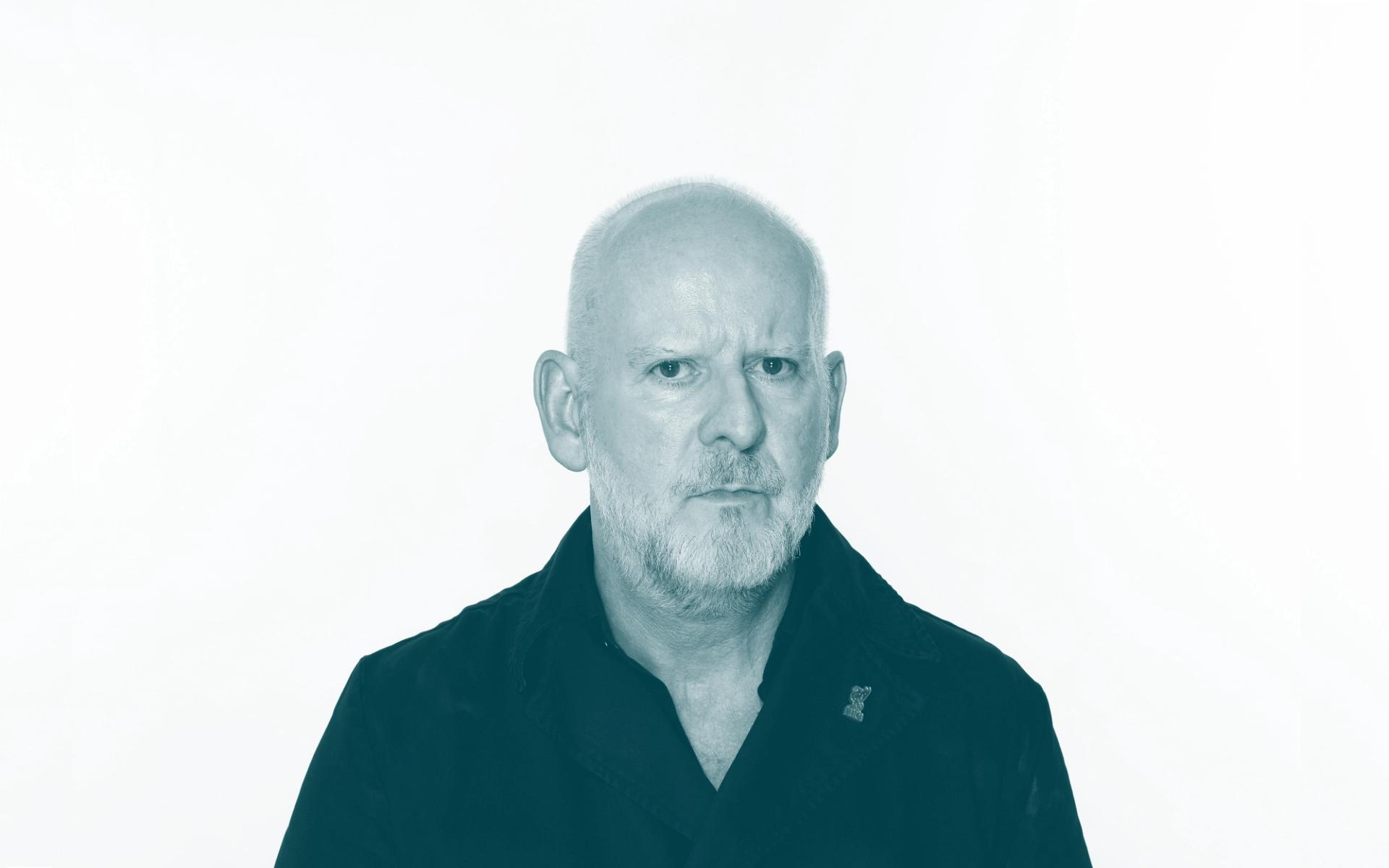

Simon Critchley. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Welcome, Simon. Thanks so much for joining us today.

SIMON CRITCHLEY: Thank you very much.

AZ: In the midst of a global pandemic.

SC: Indeed.

AZ: So, I wanted to begin today’s conversation with disappointment. Disappointment is a big theme in your life and work.

SC: Yeah.

AZ: And part of the thing that I want to explore a bit of your biography through is disappointment. You’ve argued that philosophy begins in disappointment.

SC: Right.

AZ: Which I want to give you a moment to explain for the listeners.

SC: All right. Well, I thought I should have an overview of a big story, about twenty years ago. People like the idea of philosophy beginning in wonder, because it sounds wonderful. It sounds very kind of Terrence Malick: Wonder! Which, of course, is a view that Aristotle attributed to philosophers who came before [him], who were wrong. So it’s not a view that Aristotle himself held. But it’s a popular view.

“I think it’s good to keep your mind in hell, and despair not.”

I looked to the world, and thought, That’s not a source of wonder. [Laughs] That’s a source of crushing disappointment. Philosophy can begin there. And then I began to build a picture of all sorts of different kinds of disappointment, but mainly political disappointment and religious disappointment. Religious disappointment—death of God—[and] political disappointment—what it is to live in a world that is unjust and where blood is being spilled in the streets as if it were champagne, as Dostoevsky says. That gave me a kind of frame to organize my work [with] until, I’d say, I don’t know, ten years ago. It’s still there. I still have it in mind, but I’ve got other things to say. It becomes kind of a one-trick pony.

Critchely in Brooklyn's Cobble Hill neighborhood in 2014. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

It begins at disappointment, but doesn’t end there. It ends in something else, which is more affirmative. But I think it’s good to keep your mind in hell, and despair not. That’s my approach: Keep our minds in hell.

AZ: The productive angle that I’ve learned from you is that disappointment can also be the source of creativity, and in many cases is. How did you come to that?

SC: I don’t know. I mean, it’s—

AZ: Is it simply that you feel most creative when you’re most disappointed?

SC: [Laughs] Yeah, right, when I’m really miserable. I wish that were true. But that’s not even true, and I can measure that. I mean, I remember when I was really, really sad and depressed in my twenties, I made these notes. And then, when I was less sad, a bit later on, I made other notes, and I compared them, and they were more or less the same. So my mood didn’t seem to affect my thoughts entirely.

But in relation to creativity, I think that I’m a product of the world that the 1960s left behind. And the world of the sixties—peace, love, revolution, and all of that—was a world that people like me experienced as a horrific collapsing, a kind of J.G. Ballard drowned world of disaster and social decay, and a dystopia from the get-go.

“Disappointment finds its voice in music, which is really, for me, how everything started.”

I think that disappointment finds its voice in music, which is really, for me, how everything started: listening to music and listening to songs. I think [of] someone like David Bowie, who I love, as someone who is working in relation to a disappointed context. [Editor’s note: We recommend reading Critchley’s recent New York Times op-ed “What Would David Bowie Do?”]

It’s a world which is decayed, a world which alienates, which threatens to engulf us at every moment, which we have to kind of stay away from. It’s in relationship to that, that we can perhaps make something happen. That disappointed context is the context out of which things like punk [music] emerged, and that’s where I—

AZ: Defining yourself by negating—

SC: Yeah.

AZ: In a way—

SC: Yeah. So not peace and love, but hate and war, and things like that. And it was a feeling of, I guess, why punk really worked in the U.K., and worked in a different way in the U.S,—although you could say that [the reason why] so much of the good stuff came from [America], which is obviously true, was [that] Britain was going through a period of real social and political disintegration in the seventies at a national level. And punk just spoke to that, and it found a context that was incredibly receptive.

And so, that was where I grew up. And then everything that I did in terms of what became study, which was much later, flowed from that for me.

AZ: Yeah. You’re a philosopher, I guess, by craft, and a writer.

“Calling yourself a philosopher always strikes me as pretentious.”

SC: I would say that I teach philosophy. A philosopher by accident. I think calling yourself a philosopher always strikes me as pretentious.

AZ: You’re just guilty by association. [Laughs]

SC: Right. I teach it, and I can teach it. I have an odd relationship to the academy, although I’m an academic. It’s how I teach students, and that’s how I make a living, and that’s fine. Yeah, and then, I write.

AZ: I’m curious, how much of being a philosopher is—and you can speak about others, I guess, in this case, if you’re not going to claim [to] be a philosopher—is about your own life, about your own experience?

Critchley in the Netherlands in 2010. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

“Everybody’s lost. Everybody’s messed up. Everybody’s got problems. But I think it’s a question of how you can take those problems that everybody has, and discipline them with form.”

SC: It’s about how you turn the idiosyncrasies and neuroses and weirdnesses that make a personality into something like a style, into an idiom. And that takes time. Everybody’s lost. Everybody’s messed up. Everybody’s got problems. But I think it’s a question of how you can take those problems that everybody has, and discipline them with form, which, in my case, is the form of writing, of trying to read and explain difficult texts and stretches of argument. And somewhere between those idiosyncrasies and weirdnesses and the discipline of a form, you can begin to find a voice. But if it were just me talking, that would be [just] as uninteresting as anybody else talking about their problems.

AZ: Which is how a lot of people who haven’t delved deep into it can think of philosophers. It’s sort of like the cliché of a philosopher as someone who sits around and thinks about stuff and doesn’t really do anything.

SC: Yeah. What I do is, really, having decided at a certain point that weekends were a disappointment—I think it’s the Kirsten Dunst character in the last Lars von Trier film. Which one is it? Melancholia?

AZ: Yeah.

SC: She’s the kind of person who expects more from a sunset. So you begin from the idea. It’s a sunset: “It’s nice, but I was expecting more!” And you take the gaps, the weekends, and you say, “Well into these spaces and times, I am going to spend time on my own and try and cultivate something. Try and really work.”

Critchley visiting Vladimir Lenin's mausoleum in Moscow in 2018. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

I’ve worked in all the gaps, all the time, forever. I’ve had a great time, and I’ve got friends, and something of a social life, but it’s about persisting with that. And the odyssey of doing that is persisting with that largely on your own, where really, there’s no external confirmation [of] what you’re doing—and what you’re doing looks like the activity of a crazy person who won’t leave the house. And that’s odd. A lot of time, I’m sitting at a desk or I’m lying down.

AZ: You were built for quarantine.

SC: For me, the world has finally turned into how I’ve always experienced it. I’ve had a really good pandemic. I haven’t been ill—touch wood. But the kinds of anxieties, worries, fears, hypochondria, insomnia, all the things that periodically can affect [a person], suddenly, everybody is in that situation.

AZ: It’s like, “Welcome to the party.”

SC: Yeah. It’s like, this is how it is. I’ve found the whole thing incredibly sad at the human level. I mean, things that touch me—like, I live in Cobble Hill, in Brooklyn, and there was a moment in April when forty-two people died in a seven-day period at the Cobble Hill [Health Center], which is somewhere I walk past a lot.

Things like that hit you really hard. And what was happening in the hospitals is that catastrophe, but in terms of the mood of the pandemic, and how people were feeling, I suddenly found myself kind of [thinking], Yeah, finally. This is what people should be experiencing.

AZ: So I want to go all the way back.

SC: Okay. All the way back.

AZ: All the way back. Where did you grow up?

Critchley (bottom right), around age 5, with his family at a Butlin's holiday camp in England. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

SC: I grew up in a town called Letchworth Garden City, which is about thirty miles north of London. But my family are all from Liverpool. Liverpool was always considered to be home. We were from the North. This was very important, and became more important when we ended up in the South as the one bit of our family that had moved South, and moved South because of the effects of the Second World War.

Liverpool was flattened in the Second World War. The Germans bombed it because it was a major port connecting Britain to the Atlantic economy, and all that stuff. But Liverpool was home. And to come from Liverpool meant that we were meant to be funny. You were able to do a turn, sing a song, and to be kind of engaging, be well-mannered.

My family is a working-class family, and a very articulate working-class family, but not a family that read books or considered education to be important. Both my parents left school at 14. But really that was a time defined by the Second World War and they were both evacuated from Liverpool.

AZ: Did that give you a certain license to handle school at that age, in the way that you did?

SC: With me? Well, I went to what you call it here “elementary school.” And at 10 years old, I realized that there was an exam. Back then, it was called the 11-Plus, that you took in Britain. And that 11-Plus exam determined whether you went to a grammar school or you went to a secondary modern school. And secondary modern schools, what I’d heard about them, is that 12-year-olds with beards, these giant, bearded 12-year-olds—

AZ: Are you sure they were 12, or were they just held back?

“I thought school was ridiculous. So I decided to fail all my exams.”

SC: They hit puberty at 10, these people. And they were huge. They took you into the bathroom, and shoved your head down the toilet. I remember thinking, I don’t want my head shoved down the toilet by bearded 12-year-olds. So I decided to work harder, and I got into the grammar school. Grammar school, then, was an academic education. It’s a public school, but you got a more academic education. The older teachers wore black gowns. The younger teachers were kind of hippies. And then, I failed everything. At 16, I took exams. My mum and dad broke up when I was 14, and I was kind of wildly free. And I thought school was ridiculous. So I decided to fail all my exams.

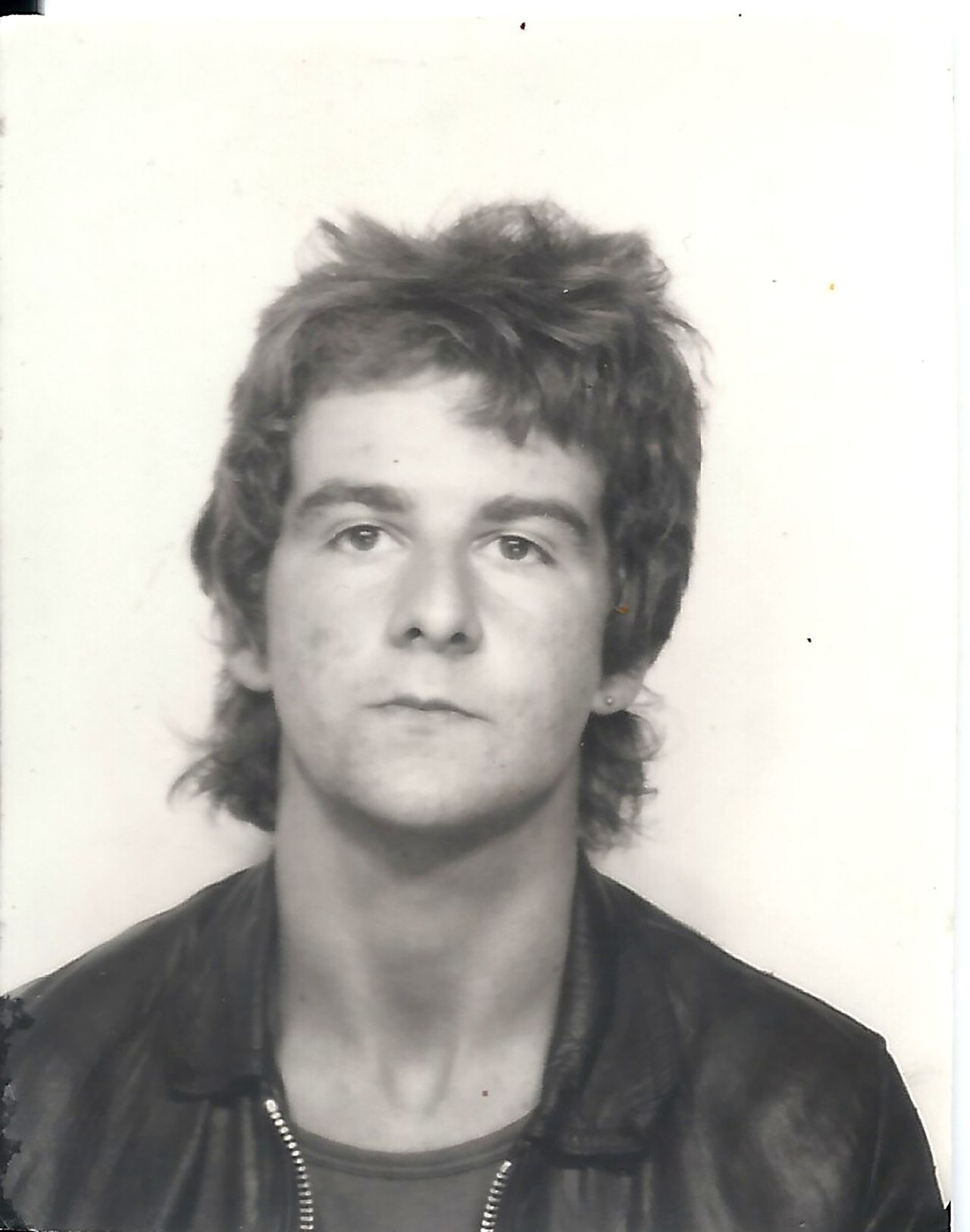

Critchley in 1978. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

AZ: You decided to fail or you failed trying?

SC: I decided. I very purposefully decided to fail everything.

AZ: What does that look like? Just, not showing up, or….

SC: I wrote weird science-fiction stories in my—

AZ: Oh, so you actively tried.

SC: Yeah. Actively messed things up on the papers. And I thought I was being so clever. I did pass geography. I got a C grade in geography, something to do with sheep farming or capital cities. And then, I left school at 16 with no qualifications. All my friends had got some qualifications, and they were going off to do A-levels, the exams that you would take in order to maybe go on to college. I didn’t, because I was already playing in bands. I was obviously going to be a pop star, so I just needed cover. I went to a catering college for two years—and not a good catering college and not good exams, that kind of really, really shitty one.

AZ: And you weren’t working?

SC: I was working…. I had all sorts of jobs. I was thinking about this recently, because I was trying to explain it to someone. I worked in factories, because my dad was working in factories. So from 14, I was working on the weekends in factories. When I describe this to students of mine, it sounds like I was living in a [Charles] Dickens novel or something.

Critchley in the Hackney borough of London in 1982. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

And I got a number of industrial injuries. I lost the top of this finger that the listeners can’t see, but that was when I was 14. That came off when I was trying to put steel metal through rollers. And then I had another much worse accident when I was 18. So the industrial life was not for me, although factories were—that’s what I knew, and what I grew up around. And that was—

AZ: And at the same time, trying to play music—

SC: Yeah.

AZ: You’re fucking up your hands.

SC: Yeah. We rehearsed in the factory, because that was the only space that we had. So we’d take our gear to the factory, which, of course, ruined my ears, because there was so much reverberation and the acoustics were terrible.

AZ: Did these injuries have a lasting impact?

SC: Yeah.

AZ: You’ve talked about them before.

SC: I’m actually disabled in my left hand. So in the U.K., I’d be entitled to a disabled sticker and a parking space. I can’t make a fist, and I got skin grafts, and it’s a real mess. And I was a guitarist.

AZ: That’s what I keep thinking.

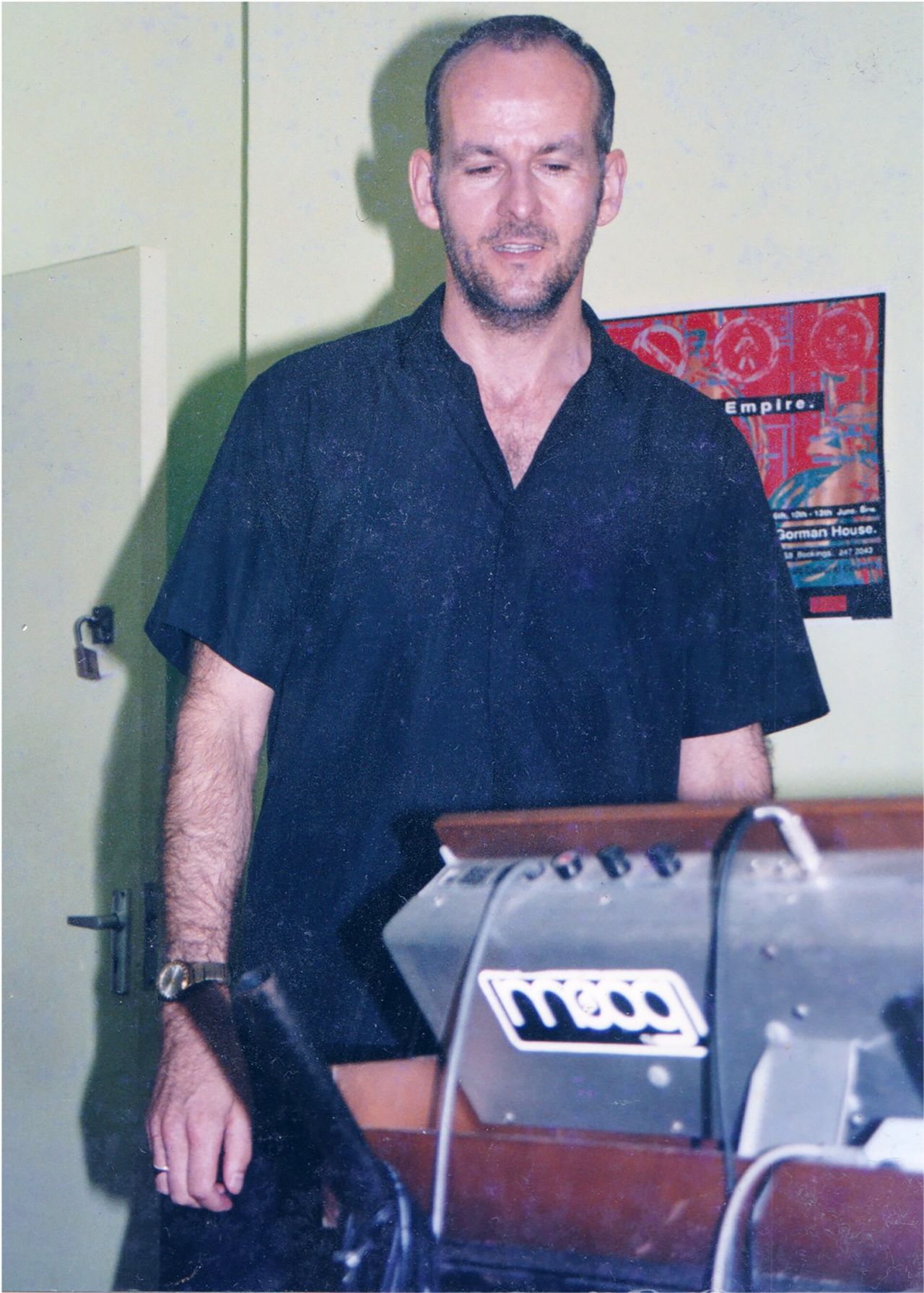

Critchley at the London studio he shared with his longtime collaborator, John Simmons, in 2002. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

SC: So, I was told after two weeks that I could keep my hand, because the hand was effectively severed, and then put back on. It’s a long story with the accident. I won’t go into that. I didn’t realize that I could have lost it at that point. But anyway, so that was, Okay, so I can keep it. And they said, “Well, you’ll never play guitar again.”

And so I bought a synthesizer. [Laughs] I bought a synthesizer. It was a kind of Wasp synthesizer, one of the first more cheaply available synthesizers. And then I found a way of playing guitar really, really—

AZ: Well, thank God you’re in punk bands.

[Laughter]

SC: Yeah. It wasn’t difficult stuff I was playing. It wasn’t technically that complicated. Then I found a way to play in a rudimentary way, and then played in bands. So, going back to the disappointment theme, that’s kind of—the disappointment was that that didn’t work out. Bands around me that we played with went on to do great things. I mean, [when] I played in bands, we supported, like, Siouxsie and the Banshees and—

AZ:The Police.

SC: The Police. Yeah. Supported The Police. Those frauds. I mean, they looked great, and were good guitarists, but [people] always supported them and nothing happened to us. We had a manager who was a drug dealer, and never made any money, and we kept trying to make it. And then, when I was about 21—and at this time I was reading a lot more, because—not at the stage in this story. I could tell a story about working in a billiard hall and how I got introduced to—

AZ: I want to hear about you being a lifeguard, though.

SC: Oh, right. I was a lifeguard. Yeah. Like Joe Biden. Right. When I was 19 to 21, I was working in swimming pools. Firstly, as the toilet attendant, I should point out. I say “lifeguard” because it sounds more grand. My job was actually—I was in the cloakrooms. And the cloakrooms are basically, you know, getting people’s clothes, hanging them up, giving out empty hangers, and then making sure that the toilets were clean.

So I was a toilet cleaner, which again is a good job to have, because in the summer days at the pool, when there’d be a lot of action in the toilets, the drains would get clogged, and you’d have to take a manhole cover off and get in there with a hose. Clogged up with the excreta of 10-year-olds, and that was…yeah. I eventually graduated to poolside work. But what I couldn’t do, either in the toilet, cloakroom, or on poolside, was read.

“I was forbidden from reading, and this really got me interested in reading.”

I had to deal with people. I was forbidden from reading, and this really got me interested in reading. So I read, and I read and read and read, and I’d had this accident, like I said. And the accident—this isn’t because it’s dramatic. It was dramatic. But there are two ways of thinking about life, and of how you shape a self, a personality. One view, which is the common view, which goes back to Freud, it’s the early stages of your life: mother, father, infancy. This is when you form your neuroses, your problems, what gives you the capacity to love or the incapacity to love, blah, blah, blah.

Another view, which you can find in [Jean-Paul] Sartre—because Sartre didn’t believe in the unconscious—Sartre had this idea of what he called a “radical project,” and that you could begin, at whatever point in a life, certainly not at the beginning. And that radical project, that kind of cut, is what could then—once you’ve made that decision, then you became that person. And the example that he liked to give was the example of Jean Genet, the French writer, who, of course, had been in prison most of his life. And Genet’s decision, when he was 14 years old, was to become a thief. Genet became a really good thief until he was caught. And Sartre says that’s what’s interesting about Genet. At 14 he says, “I am a thief.” And I think about that in relation to the accident.

When I was 18, I also suffered significant memory loss. So most of my childhood disappeared. One of the effects of physical trauma is memory loss, so I had that in a very profound way early on. Things came back, but there was a period when I, in a sense, didn’t really remember much about my childhood.

That also gave me the possibility to reinvent things. It was like a blank slate, like a tabula rasa. [At] 18, I was a bit of a mess, but I had enough money to get by. I had different jobs, and the accident had led to a situation where I was getting paid for six months, basically, to do nothing apart from take a lot of speed on the weekends and go and listen to bands, and play in bands. But it gave me that blank slate, [which] meant I could then begin to fill things in with whatever I wanted. And that was a real feeling of freedom actually.

AZ: And a reset. I mean—

Critchley at the University of Essex in 1983. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

SC: Absolute reset.

AZ: A reset that drew you to University of Essex, which changed everything. And so one question I have when I think about your history is, you’re 22. Everyone else is maybe 18.

SC: Yes. Right.

AZ: What did that feel like?

SC: It was great because I was older and cooler, and I’d done all the things that 18-year-olds wanted to do in a lot more interesting circumstances. So I had those few years’ advantage. I could be cool in their eyes. But when I got to university, at 22, I thought, Now I really, really start to work. There’s a library. There are clever people here. I’ll find out who those people are, and I will spend time with them. And the rest of the time, I’ll spend in the library, and I will just throw myself into it. And that’s what I did.

AZ: You had so much agency at that moment, when I think about it. It’s like—

SC: Absolutely.

AZ: Those four years, five years of time, and having these other experiences, you were just in such a different position to take advantage of that context.

SC: Yeah. I mean, for whatever reason—this is Dave Chappelle’s advice: Be nice and don’t be scared. This is advice I’d give to anybody. [It’s] very hard to do. People are not nice a lot of the time. They’re assholes to each other, and people are scared. For whatever reason, back then, I wasn’t scared. I was anxious, but I wasn’t scared. And I thought I could use this. I could read everything—

“This is Dave Chappelle’s advice: Be nice and don’t be scared. This is advice I’d give to anybody.”

AZ: Well, for five years, you were practicing vocalizing against fear, which is the music you were making. I mean, what was punk, really? “I’m not scared.”

SC: Yeah. Not being scared. It’s true.

AZ: I’ve thought about that a lot in terms of this story of yours, that you enter school at that moment, [and] you’ve been playing punk music. You had a major hand injury. You’re very comfortable in that space.

SC: Yeah. It felt like a continuation. I wasn’t the only person that played in punk bands that wound up at the University of Essex. There was a bass player. There was a band called The Lurkers, who everyone’s forgotten now, but they had a great song called “Shadow.” It was, [sings] “Shadow, shadow, shadow.” It was really kind of a simple song.

Two of them wound up doing sociology at Essex. Universities back then, and this is what kind of winds up [to] what I’m doing, they just felt like these free spaces where there were these weird people—teachers, lecturers, professors—and these people felt they were intelligent. They were wild.

AZ: And there was one in particular that affected you.

SC: Oh, right. [Robert] Bernasconi. Yeah. I did really well in my first-year exams. I was kind of identified as talent, and then cultivated, and basically allowed to do what I liked. And then I did what I liked and Robert Bernasconi was incredibly kind to me and gave me enormous amounts of time. So I spent hours just talking to him about things.

AZ: And did he help you do the switch from literature to philosophy?

SC: This is what made it so interesting. The people that you were taught by were so odd. The guy that got me to do philosophy was someone called Frank Cioffi. C-I-O-F-F-I, who was a New Yorker. New York–Italian, a Sicilian, who’d grown up somewhere close to Washington Square [Park]. Both his parents died. He was brought up by his uncle and aunt. At the end of the Second World War, he was in the U.S. Army, and was involved in these mop-up operations in France.

And then somehow, because of the G.I. Bill, wound up going to the University of Oxford and doing philosophy. And he was six-foot-four tall, and he didn’t write very much, and was just this wild character full of tremendous stories. I was sitting in his office because I had this—I said, “I’m not sure whether I should do philosophy or not.” And he had no interest in that.

“My life’s work will be trying to save souls, right? People that were like me.”

He just started to say, “Well, when I was in Singapore, teaching, there was this moment, because I thought there was no problem of other minds when it came to animals. I thought, Well animals, [they’re] not really an issue for me. I don’t really think about the question whether they suffer or not. And then in Singapore, we had a problem with cockroaches in the offices. And so I put down this poison in my office, and then I’d come in the morning, and you see these cockroaches wriggling in pain in their death agony. And at that point, the problem of other minds came alive for me again.”

So he’d tell stories like that, Frank. And his only advice to me when I got a job in that department was, “Always check your fly.” That was his only advice. “Always check your fly.” Which is actually really good advice, because you don’t want to be teaching with your fly undone. So these were weird, bohemian, free characters who I kind of loved. And then I thought, well, I could—

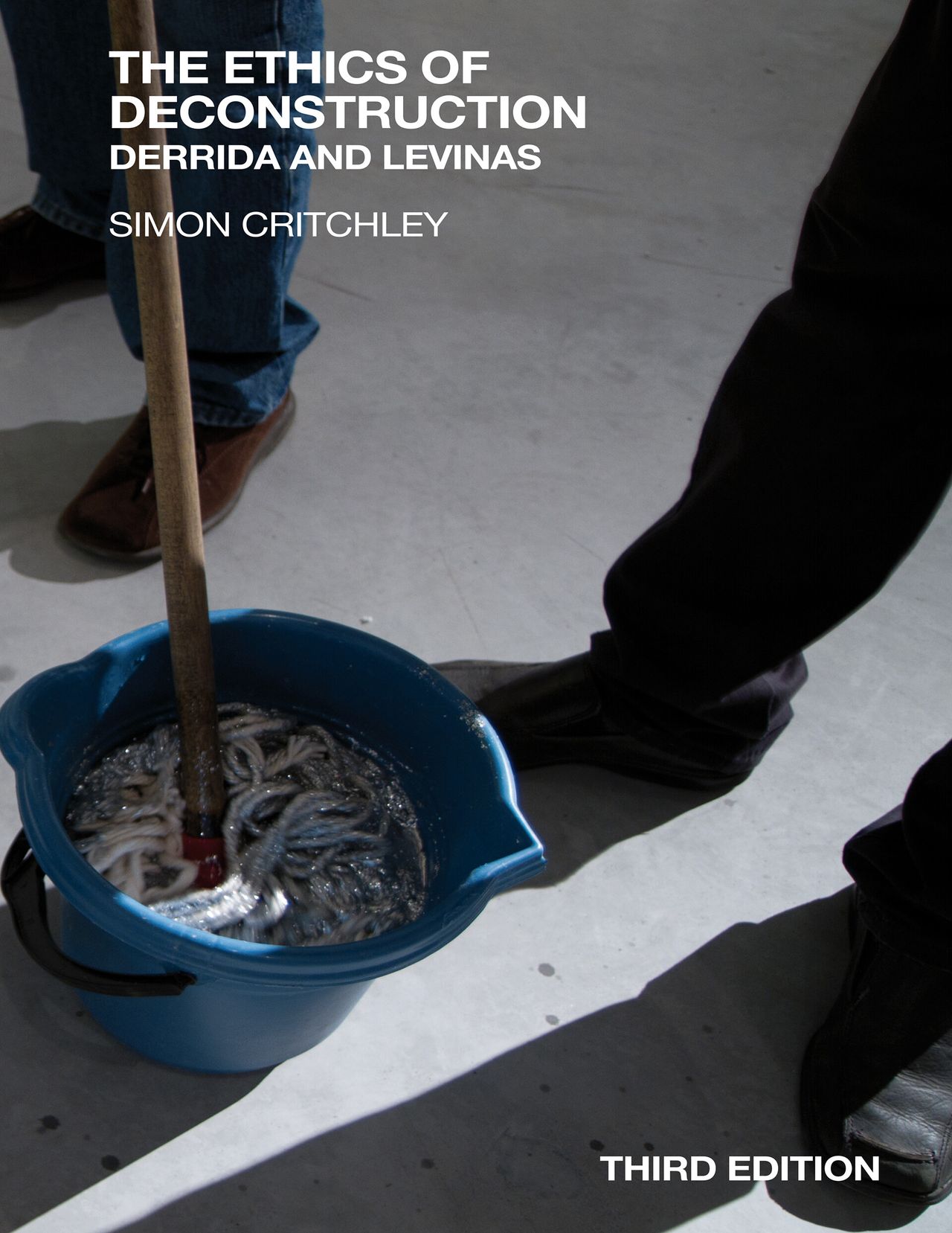

Critchley's 2014 book The Ethics of Deconstruction: Derrida and Levinas. (Courtesy Edinburgh University Press)

AZ: Find a home.

SC: I found a home. I thought, “Well, I could do that.” So my life’s work will be trying to save souls, right? People that were like me. And it’s still the way I try and think about teaching: I’m looking at a group, and I’m always trying to find the one or two weirdos, and pull them out and say, “You could do this, and this and this and this.” And you find out what they’ve been reading, and you just push them.

Because if someone is clever and turned-on as a mind, then they don’t need much teaching. If you can say, “Just go on,” that’s enough. And say, “Go on, do that, and yeah, you can do that here.” It’s a question of—a sense of permission, and license, I think, is really important. So for me, universities were these amazing, free spaces where people could just develop their minds. And I worked like a dog. But it was … yeah, it was a joy, you know?

AZ: You had some very early success. At 29, you’ve got this job in the philosophy department at Essex, and then your book, The Ethics of Deconstruction, came out, which became a huge deal. A lot of people won’t necessarily know about that history. Help us understand what caused the stir. And also, what was the experience for you? What was the confluence of things?

SC: I went to France after I finished my degree, because I thought that this is where interesting thinking is going on.

AZ: [Jacques Lacan] and these are the people you were—

Jacques Derrida (right) talking with writer and scholar Chinmoy Guha. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

SC: [Jacques] Derrida, [Michel] Foucault, [Gilles] Deleuze—all these people fascinated me, and back then much of it wasn’t translated. So I read French. I taught myself to read French slowly, and then ended up doing a degree in French, writing in French—which is actually another bit of advice that I give people: If you can write in a foreign language, it’s actually a really good discipline. It really cleaned up my style.

So I wrote a two-hundred-page dissertation in French with a relatively small vocabulary. It was in France that I really learned to do research and how to use a library and organize a bibliography. And [I] finished the Ph.D., [and] got a job. I’d written this Ph.D. dissertation on [Emmanuel] Levinas and Derrida. Levinas was this Lithuanian-French-Jewish philosopher who[se work] I fell in love with when I was 22, and is still the only philosopher that I would defend.

AZ: Most of the others you’ve challenged. [Laughs]SC: Well, they come and go. But Levinas, I just think, I will defend him with my last breath. And he has very poor arguments as well. That’s the strange thing about him. He doesn’t really argue. He’s not a very good philosopher. [Laughs] He’s just got really interesting intuitions. And so, back then, the philosophical avant-garde, as I understood it, was represented by Derrida. Jacques Derrida’s work was what people were thinking about.

Emmanuel Levinas. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

People talk about soccer, or whatever, or basketball. There’ll be basketball players. And then there’ll be the basketball player’s basketball player, or the soccer player’s soccer player. Derrida was like the philosopher’s philosopher. He was like [the soccer player] Lionel Messi. He could do anything. And I thought that his work was driven by a very clear ethical commitment. And I couldn’t figure out why no one else had seen this, because it was seen as being that deconstruction was “free play,” relativism, postmodernism, all that. It’s still in the air, with people like [psychologist and philosopher] Jordan Peterson. All of the people still say that stuff.

[Derrida’s] work is driven by a very clear ethical commitment, which I linked to this other guy, Levinas. I published that, and then, the good fortune I had was that there was an idea, a proposal, for Derrida to get an honorary doctorate at the University of Cambridge, and the philosophy department decided against it. And it became a sort of fight, a kind of a cause célèbre. Eventually, he did get approval to receive the honorary doctorate, but this was front-page news in Britain. The front page of the Independent newspaper, or The Guardian, was, I think, “Cognitive Nihilism Hits English City.” So “cognitive nihilism,” Derrida, hits “English city,” Cambridge. People were reading about this. What everybody was clear about was that Derrida was a kind of value-free, nihilist thinker. And my book came out arguing the opposite, so it got some play. I found myself with a different kind of audience, and that was a lot of fun.

AZ: It didn’t shift their decision to give him a doctorate or not, though.

SC: They eventually did.

AZ: Do you think your book had anything to do with it?

SC: Nah, I don’t think at all. And Derrida and I kind of fell out about the book, because he’d been very kind to me. But he was very sensitive to criticism. And I criticized him very hard in the end of that book on questions of politics, which wasn’t developed in his work. And he took umbrage for a while, but then eventually, we got back along. I saw a lot of him, but I was never really close to him in the way that [other] people were close to him. [When] you put something together and it gets some play, it gets some attention, so of course everyone’s saying, “Well, the next thing you should do should be exactly the same thing. Do Ethics of Deconstruction II. More Ethics of Deconstruction.” I decided very soon after that book that I was going to go in a completely different direction.

Critchley in Paris in 2002. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

I spent five years writing [Very Little… Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy, Literature, published in 1997] a book about philosophy, literature, and nihilism, and other stuff, which is a very different book. And that’s something that I’ve tried to do over the years, is that when you find the form—and art, photography, cooking, everything is about finding the form, and philosophy, too—once you’ve found the form, since it’s [then] no longer of any interest [to you], then you need to take a right angle, move in a different direction, and find something else. So when things have gone particularly well, [I’ve tried] to go off in a totally different direction, just to see where that will take me.

AZ: Which is something we’re going to get to. But I mean, [that] is why your books are so varied.

SC: Yeah.

AZ: They all kind of ladder up to something similar, though. But what I didn’t want to forget at this moment in the story is, at some point you had a son.

SC: Oh yeah.

“Art, photography, cooking—everything is about finding the form. And philosophy, too.”

AZ: So there’s this whole career happening, but you’re also creating a family and a relationship.

SC: The proudest thing in my life is my son, Edward, who is the apple of my eye. He was born actually the month after the first book came out. I remember my father coming to the hospital to see his grandson. I gave him a copy of my book, and he looked at it and picked up Edward, as he should have done.

AZ: I find it interesting that your first kid happens at the same moment as your first book. You have this huge success, and then you have this kind of—not distraction—but this other thing to focus on, which is the beginning of a life.

SC: Yeah.

AZ: In those early days of parenting, were you feeling like, “I should be writing. I should be drafting off the success I just had”? Or, “I can kind of hang out, and get into this”?

SC: I didn’t really think about it in those terms. It just seemed that there was a whole [other] set of things to do. I was teaching in a provincial university in another part of my life in these years. In the eighties, and the first half of the nineties, I was a member of the Labour Party and an activist—but not in that way that people talk about it now, as if it’s some, “Oh, I’m an activist.” I was a useless activist. I was crap at going onto doorsteps and getting people to vote.

But my partner at the time, she was very good at it. So we spent a lot of time doing that, just, getting-the-vote-out kind of work for the Labour Party, because the threat in Britain at that time was the threat of Thatcherism, the reality of Thatcherism, and the only vehicle to remove Thatcherism was the Labour Party. Therefore, the Labour Party had to become electable. And I was involved in, as a lot of people were, who were on the different parts of the left—we joined the Labour Party, and we were pragmatists. We wanted Labour to get power.

It took eighteen years, and it took the form of Tony Blair, whose period has been largely misunderstood because it’s all seen through the lens of the Iraq War—

AZ: Of [George W.] Bush.

SC: And Bush, which is a real pity because good things happened in the early years with Blair and Gordon Brown. Like, my mother’s pension went up, and the health service was better provided for and—

AZ: Yeah, but there was a major trauma that shifted everything and that was the time you came to New York.

SC: Oh yeah. Later on.

Critchley in Philadelphia in 2008. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

AZ: What brought you to New York?

SC: It was fairly clear from around the late nineties that the intellectual context that I had at the University of Essex and in Britain was becoming less interesting. People had left, had retired, had died, or just kind of run out of steam. So I was part of a generation of people who felt very lively, and a lot of people didn’t follow through with that.

So it felt like the context was less interesting. I was becoming less interesting. The work was becoming less interesting. I could feel myself ending up as a university administrator with a few Ph.D. students, and I’d stopped really teaching new stuff. This happens a lot in Britain. It happens a lot in universities.

And there’s a much longer version to this story. But when my son was old enough, so that he could fly here, to New York, and I kept a bit of my job back in England—so I was going back and forth a lot for the first five years, and he was coming here. When that was doable, I thought, Well, the intellectual level in the United States was higher, seemed more exciting, more interesting.

Critchley in his office at the New School for Social Research in 2018. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

And the New School for Social Research was somewhere where I.… It just turned out that I knew everybody. Everybody was called “Bernstein”: Richard Bernstein, Jay Bernstein. He was my first undergraduate teacher, Jay Bernstein. There was this department, and I had the chance to work there, and it was—

AZ: Which has this amazing history.

SC: This amazing history [that is] kind of saturated in the German intellectual tradition, French intellectual tradition, and also, somewhere that’s a direct consequence of the effects of national socialism. The fact that the New School for Social Research was set up in 1933 in New York to house German Jewish professors that had just been sacked because the Nazis had come to power—it’s a history of being a university in exile. And a university in exile of a political character, with very particular ideas of intellectual rigor and standards. And so, when I got to the New School, I was particularly proud because, at that point, I was the only non-Jew in the philosophy faculty. I was like the honorary gentile. Shabbos goy, I think it’s called.

AZ: Shabbos goy.

SC: I was a shabbos goy! They needed one non-Jew around—

AZ: They needed you to turn the lights on and off.

SC: That’s right. He’s not that smart, but he’ll do! [Laughter] And I realized that if I was going to survive here, I had to raise my game. Because I was with people—Agnes Heller, Yirmiyahu Yovel, Richard Bernstein—these were people who could teach me into the ground. These were serious intellectuals. So coming to New York was a real feeling of having to really increase the levels of quality in what I was doing.

AZ: Did you like teaching as opposed to writing?

SC: I shouldn’t say this. I don’t think I like teaching. I think it’s something I do. I don’t think I’m particularly good at it. I think I can find certain people and pull them through. And I’ve had some extraordinary students at the New School who I’ve been able to help develop their talent, and that’s a joy.

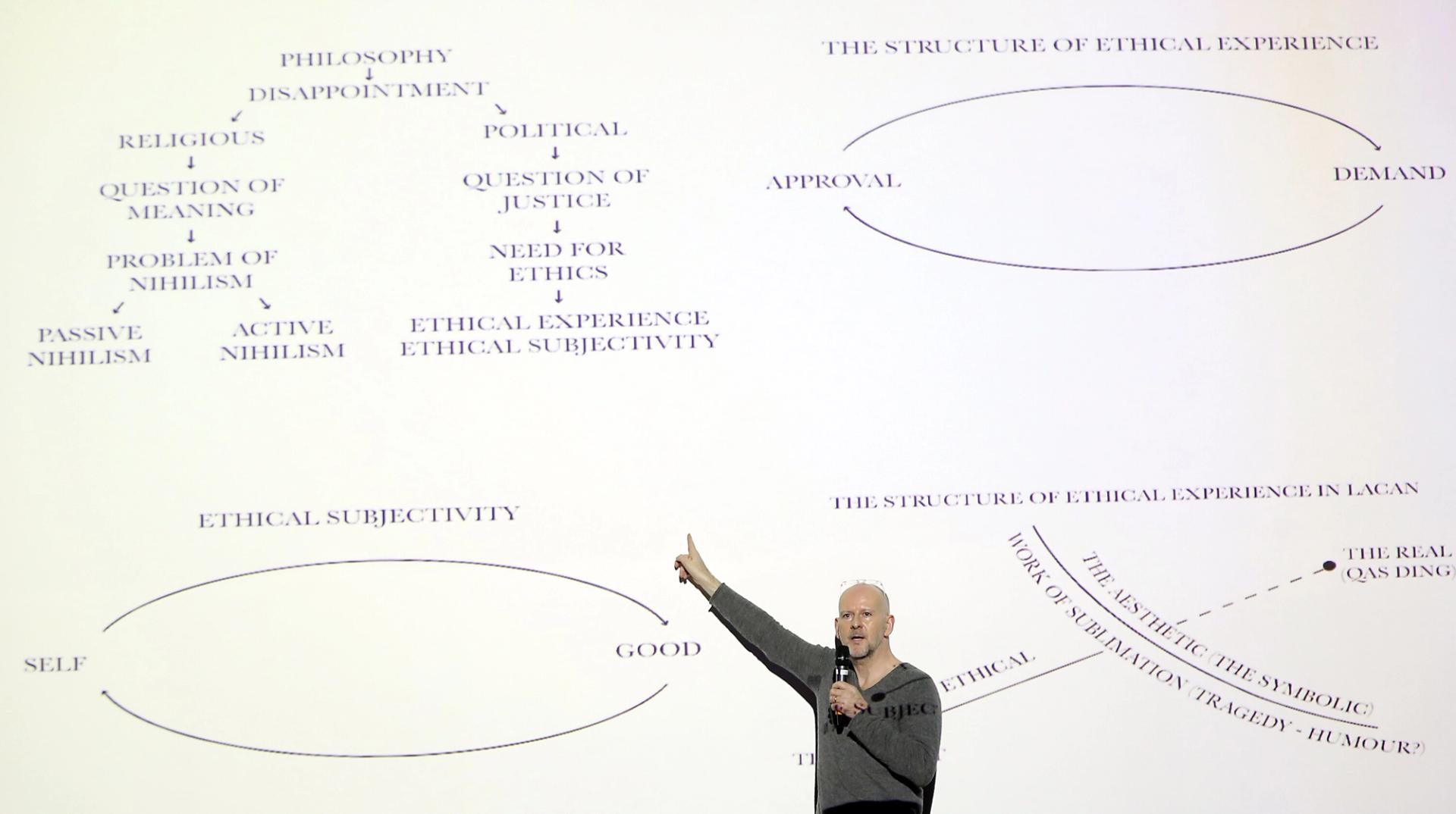

Critchley lecturing on his theory of ethics at Moscow's Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in 2012. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

“I like to hide things under the surface.”

I think there are better teachers than me, but I think I can turn a sentence. I’ve been able to develop a form of writing. What I’ve consciously tried to do, in the last fifteen years, really since being here, is to try and develop an idiom of thinking that I think is serious, and it’s deep, but it’s also—I like to hide things under the surface.

I don’t want to name-drop. I don’t use jargon. All the stuff is there, if you want to look, but you could read this as just a straight, say, op-ed. So while I like writing right op-eds for The New York Times, and this was something that I had to learn to do and it’s been a real joy, is that I worked out that I could hide things in op-eds, like little submarines. So you can write for an audience, and it just seems you’re making a clear, compelling case—

AZ: Very objective. Yeah.

SC: Right. But under the surface, there can be all this other stuff going on. That way of doing philosophy, where you hide the engineering, you hide the drainage systems, and the—

AZ: Well, it leaves room for people to come in.

“You can say things that are deep and straightforward. That commitment to clarity doesn’t mean you have to sacrifice rigor and seriousness.”

SC: Yeah. It’s accessible. And I think everything can be said clearly and simply. Philosophy’s not difficult. Jargon is pointless and inexcusable. And I think that things can be said clearly, but that doesn’t mean that they’re simple.

AZ: Exactly.

SC:You can say things that are deep and straightforward. That commitment to clarity doesn’t mean you have to sacrifice rigor and seriousness.

AZ: There’s another part of writing that I’ve never forgotten, where you said, “I write in order to forget.”

SC: Yeah.

AZ: That can mean a lot of things. What does that mean to you when you say that?

“There are things rumbling round my head, and when I’ve written them, they’re gone. And then I can fill my head up with other things.”

SC: It means to get things out of your head. There are things rumbling round my head, and when I’ve written them, they’re gone. And then I can fill my head up with other things. For me, it’s like a detox, or going to the toilet, or something. It’s an evacuation. Once I’ve got that out, it’s out, and I don’t remember it. I can remember it—I could look at it and [think], “Oh yeah. Okay. I said that.” But it’s not what’s going on in [my mind] at the moment. So I clear out [my mind] in order then to open up space, and allow new things to happen.

AZ: Disown in a way

Critchley in Athens in 2019. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

SC: Yeah. To disown, and also to try and maintain a curiosity and an openness to things. What I do like about teaching is that it gives me extraordinary access to the minds of young people and what they’re thinking about.

And now, with Zoom—people complain about online teaching, [but] I love it. I’ve done one-on-one Zoom meetings with my students. I know where they live; [I’ve seen] inside their rooms. In a sense, there’s a kind of revealing that takes place here. And you can talk to them as adults, because they are adults. And then they’ll [ask], “Have you read this? Have you looked at this?” And I’ll always follow that. So at the moment, I’m reading the best book I’ve read in the last month, The Psychopath Test by Jon Ronson, because a student mentioned it to me. I can’t stop reading it. It’s just so good. I wish I could write like Jon Ronson. I wish I could make documentaries like Adam Curtis, but—

AZ: These things are not for everyone, though. I’m glad you don’t make documentaries like Adam Curtis, actually. And I think if you did make documentaries, they’d be more understandable than Adam Curtis’s, who we both love, of course. So—

SC: But he’s found form.

AZ: I think we bonded over [Curtis’s film] HyperNormalisation actually, when we first met.

SC: Yeah. Absolutely.

Critchley in New York, before the 2018 Union of European Football Association's Champions League final. (Photo: David Buckley)

AZ: Brilliant, brilliant film. You’ve explored a number of topics in your books: [David] Bowie, football. The last one I read was on the Greeks, [called] Tragedy, the Greeks and Us, which is so interesting. But before we get into the specifics, what generally starts that process? I mean, I’m always wondering, How did he come to write about Bowie? How did he come to write about the Greeks? What starts the decision to write?

SC: I’m very good at having one-on-one working relationships with people who are often men, right? So there’s a strange kind of homo-social side to the way I operate, which it’s not something I think about. But if I think back…. Say, for example, the Bowie book. There’s a friend of mine called Colin [Robinson], who [is the founder of OR Books], is an editor, but more importantly, he’s from Liverpool, and we both support Liverpool Football Club.

AZ: Do you spend a lot of time watching—

SC: I spend an awful lot of time watching Liverpool Football Club, and it means the absolute world to me, that team. We’re talking about sons, or kids—my primary activity with my son…. I mean, week on week, day on day, we’ll be going over the team. And the joy of being a parent is that point you get to when they know a lot more than you do. And so you become the student, and they become the teacher.

This happened about ten, twelve years ago with my son. So we talk a lot about that. So there’s me, and I’m 60 years old. My son, who will support the team for another thirty years, and on my grandmother’s gravestone is the Liverpool Football Club crest, which I didn’t even notice. I photographed it about ten years ago. She died in 2001, and I photographed her grave, and I showed it to someone, who said, “There’s a Liverpool, LFC, crest [on it].” And I said, “Of course there is. It’s [her] team!” [Laughs] Of course, there’s that. You’d expect it to be Manchester United or something? What did you think? So from my grandmother to my son, that’s a century of that team, and that connection to place, which is a place that, in my mind, I’m from, although I’m not really from.

Another reason to come to New York is the John Lennon story, right? Lennon would say that in a certain light, in a certain time of the day, a certain day of the week, New York would remind him of Liverpool. I feel that. They’re similar cities. Liverpool, smaller.

AZ: By the water.

SC: They’re commercial cities. They’re cities by the water. They’re ports. They’re places where there’s immigrants, where people are moving through.

AZ: There’s a roughness, but a humor.

Critchley at Brooklyn's Long Island Bar in 2014. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

SC: Yeah. There’s a roughness. There’s a humor. It’s about money and about culture. That’s it. These are not centers of government. These are not metropolitan centers. This is not Paris or London or Berlin. These are ports, and I love ports.

I live in Brooklyn, and I can see the water, and the [New York] Harbor, and the Verrazano[-Narrows] Bridge, and the idea that there is the Atlantic Ocean…. This is hugely important to me in terms of the spiritual sense of this place.

AZ: Of place. Yeah.

SC: And also with the pandemic, what I’ll say is that I find that, I love New York, as they say, but during the pandemic, and now, I feel a renewed fanaticism about the place.

AZ: But you have to be careful to avoid what you’ve always criticized after 9/11, which was the sort of hubristic pride in New York.

“Moods are not things in the head. Emotions are things which are out there in the world.”

SC: Yeah. But it’s a unique and odd place, and I’m very happy to be here. And also, I’m a kind of Heideggerian, so I believe that moods are not things in the head. Emotions are things which are out there in the world. And I found it an enormous comfort in the last six months that what I’m feeling is what seems to be felt in the city. That it’s not just me.

AZ: There’s a phenomenon.

SC: There’s a phenomenon, and it changes. And during April, May [2020], it felt—and then obviously after the killing of George Floyd, we went through this series of moods—but you felt it was a shared phenomenon. We were all going through this. And that’s cool, right? That’s a really cool thing to be part of. So your question was something else though. I’ve forgotten it.

AZ: We were talking about your books, and—

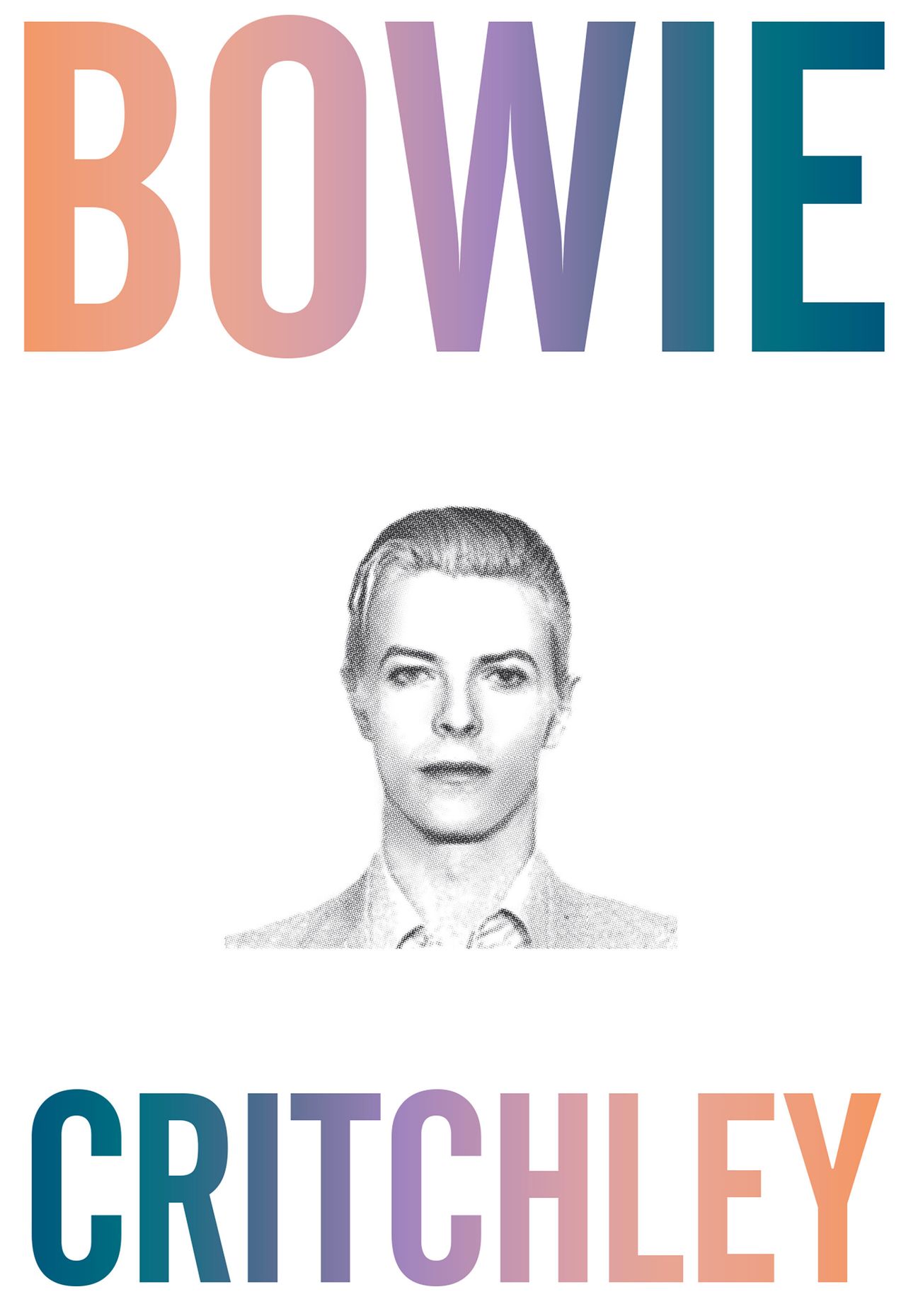

Critchley's 2014 book Bowie. (Courtesy OR Books)

SC: Oh, yes. So I was talking to Colin about Liverpool, about the team, and we had to do a season review. Because you’ve got to do a season review. A new season was beginning. He was away for the summer. So we met, [and asked each other], “So what do we think? What’s going on? What’s going on with the team? What’s going to happen?”

There was a lull in the conversation, and he says, “What else are you doing?” [I said,] “I seem to be writing something on Bowie. I’m thinking about writing something on Bowie.” I explained it to him. He said, “Oh, well that could be a book.” So I wrote it. And then Colin said something else. He said, “Well, it’s a bit linear, isn’t it?” When I wrote it, it was [about Bowie’s] life and work. He said, “It’s a bit dull. Couldn’t you do it in some other way?” So then I was thinking about the cut-up technique of [artist] Brion Gysin. And so I got a hard copy of the manuscript and I then began to move pages around, and do cut-up, and kind of think, Well, I could put that—

AZ: Cut with pages instead of single words.

SC: Yeah. And then just say, “Well, actually, if I put that with that, that actually kind of works.” So I began to do a kind of counterpoint structure. I do believe in counterpoint as well.

AZ: Yes, you do. And it comes out in a lot of your work. One of the things I’ve been thinking about with your writing that I wanted to ask you is, I always wonder, Do you like to write? I know that it’s sort of a job for you. “Like” is a tough word. You like to do other things.

SC: I’m teaching this class with [philosopher and business advisor] Christian Madsbjerg on human observation this semester. It’s the third time we’ve taught together. We’re trying to get students to think clearly about phenomena, to observe phenomena, which is a very hard thing to do.

“[George] Orwell says that writing is a ridiculously painful activity that is driven by vanity and narcissism.”

The first week, I give them two essays by George Orwell: “Why I Write” and “Politics and the English Language.” Just to say that, here’s someone—look at what Orwell says about writing, and look at how Orwell writes. There’s no fat here. [He follows] basic rules: If there’s a word with many syllables versus a word with less syllables, use the word with less syllables. Use the active voice, not the passive voice. Things like that. Orwell says that writing is a painful, a ridiculously painful, activity that is driven by vanity and narcissism. You have to begin from that. Writing is hard, and what’s driving the writing is a basic vanity that writers have. But if you’re cunning and you’re clever, you can push yourself out of the way of the writing, and allow something else to appear.

AZ: You’ve got to get to that place.

“You have to pull away at yourself, strip things away, in order to open a space where you can actually think and write, and develop a form where that becomes possible.”

SC: Right. [French philosopher and political activist] Simone Weil had this idea of de-creation. You have to de-create, pull away at yourself, in order to open a space that, for her, was a space of the relationship to God. For me, it’s more that you have to pull away at yourself, strip things away, in order to open a space where you can actually think and write, and develop a form where that becomes possible. So I think the good bits about writing are when you’ve found the form, when the form begins to appear. And then you—

AZ: And you can get a stress-test right after you go.

SC: Then you can mess with it, and you can begin to stretch it, and pull it. Then you can begin to bury things. So if there’s all these references, then lose the references, bury those, and then someone might see you’re passing—

Critchley at a David Bowie tribute in 2016. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

AZ: You also explore the possibilities of what you’re becoming, in a way, through your writing. That’s why I think they’re so varied, because you’re new every time you’re writing.

SC: Yeah, absolutely.

AZ: You’re not returning, as many ineffective writers do, where you feel like, Have they learned something since the last book?SC: Actually, I was listening to [actor] Steve Coogan and [director] Armando Iannucci talk about this yesterday afternoon. Coogan was talking about improvising and writing. Improvising is writing. Writing is improvising. I’ve always been very interested in comedy and in writer’s rooms and what goes on [there]. And the sense that what you get as a writer is that, if you give yourself that license to just do it—and you know that you’re not totally going to screw it up, because it’s kind of worked in the past—but at that point, you go out to the edge of the springboard and you just…. You’ve got to hold yourself out there.

“Improvising is writing. Writing is improvising.”

The problem with writing is that people are too consumed with anxiety, inhibition, and all of that stuff and that gets in the way. You have to be bold and take risks. And as you get older and you’ve done more of it, then you can begin to let that go where it goes. Which is what I think, with a great comic—a great comic, every night, or every act, is doing that, is putting themselves out there. They know that it’s probably not going to go wrong because they’ve done this a thousand times. But still, they’re taking that risk.

AZ: There’s that edge.

SC: Yeah, of completely falling on their face, of dying.

Critchley's 2002 book On Humour. (Courtesy Routledge)

AZ: You wrote a book about it, called On Humour, where you explore the role that humor, jokes, laughter, [and] smiling play in human life. What did you discover in the process of writing this? I knew you were a huge fan of comedy, from the Marx Brothers, growing up, but you’ve also been deeply interested in contemporary comics and their role in life. What did you discover [while writing] the book?

SC: Firstly, you don’t need a philosophy of humor. That’s my point, is that humor is itself an activity of philosophical reflection. So I like that. It’s a book you don’t need. The book is a kind of ladder you can kick away, a ladder you don’t even need. To be able to tell jokes, or to engage in humorous banter, requires a level of cognitive conceptual complexity, which is worthy of any philosophy, it seems to me.

To ask yourself, Well, what’s going on in humor? There are a thousand different ways of doing that. But for me, it really comes down to the distinction between laughing at others and laughing at yourself. Often, bad humor will be laughing at others, and interesting humor is usually laughing at yourself. I think about this in relation to a joke that Freud tells [in his 1927 essay, “Humor”], because Freud was funny, and collected jokes, which people always forget about Freud.

He says, There’s this joke. A man is condemned to be hanged. He’s in his cell. On the morning of his execution, he comes out from the cell, walks into the courtyard, and sees the gallows ahead of him. [He] looks at the gallows, looks up at the sky, and says, “Well, the week’s beginning nicely.”

Freud says, “Why is this funny? What’s going on in this?” And his answer is that, in humor, we look at ourselves from outside ourselves, and we find ourselves ridiculous. And that finding oneself ridiculous is the key thing. Comedy, jokes, have a relationship to the unconscious, Freud says. So if I made a series of, say, homophobic gags, right right now, if I did seven homophobic gags—Andrew, you might think, Well, maybe Simon’s got a problem with his relationship to homosexuality, and the jokes are kind of a way of dealing with this, this repression of that. That’s Freud’s view.

“Humor is this ability to reflexively look outside yourself, and then to find yourself ridiculous. And in that moment, you are both diminished and elevated.”

So jokes are kind of repressed content. And that’s fine. They’re ways of reading the unconscious. [Donald] Trump is a good example of that. But humor is something else. Humor is this ability to reflexively look outside yourself, and then to find yourself ridiculous. And in that moment, you are both diminished and elevated.

AZ: The best comedians can shift your thinking in the ways that the best philosophers can, so they can take you down a road, and you have a problem with it. And then they can take you down a deeper road that you have even more of a problem [with]. You go, “That’s not so bad, is it?” Louis C.K. does that very well.

Critchley dressed as French philosopher Michel Eyquem de Montaigne in 2016. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

SC: Yeah. And there are certain traditions, certain cultures…. I remember when Jews were funny. I’m that old. So for me, Jewish humor, the exposure to Jewish humor, in the form of the Marx Brothers, in particular [was influential].

Recently, I went back to Jack Benny because he was the biggest star in the 1950s. The Jack Benny Show. Did those people out in the Midwest know that Jack Benny was Jewish? Is that—

AZ: Did they understand it?

SC: There’s that question. But if you look at the technique that Benny had…. Firstly, it’s hugely funny. It’s all about indirection. Some of those early shows were as wild and as complex as Charlie Kaufman narratives. He’ll do things by this ability, the Jack Benny ability, to pause, and kind of look to his side. He does nothing. He’s doing nothing. He’s looking to his side—

AZ: He’s holding space.

SC: Yeah. He’s holding the space, and people are laughing. And he waits. I think you can learn a lot from comedy. This is kind of my late-evening pornography, things like The Larry Sanders Show. I will delve and dive and I’m always in the market for new stuff, and I hope to find new things. And I like jokes. Like, What do Winnie the Pooh and Attila the Hun have in common? The same middle name! Things like that.

[Laughter]

AZ: Well, one of the big fears about this current moment of cancel culture is that the confidence and fearlessness you need to actually practice humor is being threatened right now.

SC: A lot of people say that. A lot of people criticize that—[Dave] Chappelle, who I like a lot [for instance]. And again, I get what people get wrong about comedy, and Chappelle’s a good example of how people get that wrong. Dave Chappelle, it seems to me, has a commitment to form. It’s the form of stand-up comedy, right? A one-hour routine. And Chappelle, like great comics, will produce that form.

AZ: Plant the seeds, let it grow, brilliantly.

SC: Let it grow. Come back to it, divert the audience, plant the fake joke. And if you read that semantically—Dave Chappelle said, “Michael Jackson didn’t do it!” You’re missing the form. That’s not the form of humor. There’s a huge pair of scare quotes around the stage when you’re watching comedy, and these big scare quotes are important, because it gives people freedom and license to say anything.

“Saying anything—it’s comedy!”

And that saying anything—it’s comedy! It reveals all sorts of—but it’s comedy. I see Chappelle in direct continuity with not just with [Richard] Pryor, but with traditions of Jewish humor and English humor—

AZ: All of that.

SC: It’s about a commitment to form. And I think there has to be a fearlessness at that level. It’s hard to do. And people can be pretty stupid. And the thing about humor is that—

AZ: It requires context.

SC: It requires context. And it also requires the cultivation of intelligence, right? It means that to be a proper, grown-up human being, part of that apparatus is the intelligence to both tell gags, or to receive gags, and let them circulate. This is the kind of—

AZ: Outside of the self.

“What I do is like stand-up comedy, except it’s not funny and you don’t have to stand up.”

SC: Yes. The sunshine of life. It really is. And it’s dark. Nothing is darker than comedy. So I think about if I was going to be rather grandiloquent, [I would say that] what I do is like stand-up comedy, except it’s not funny and you don’t have to stand up. So it’s a kind of sit-down, non-comedy. That’s how I see it. But it’s a living.

AZ: The other thing you do that I didn’t want to let go is, you’ve kept a music practice up your whole life.

SC: Yeah, with some gaps, but I try to.

AZ: And you produced a song during the pandemic.

SC: Yeah.

AZ: You [and longtime collaborator John Simmons] wrote a particularly profound track that you produced during the pandemic. I want you to talk about it a little bit. We’re actually going to break for a second to hear it.

SC: Okay.

[An excerpt from Critchley and Simmons’s new song, “Eat Your Funky Dasein,” plays]

AZ: That was a little snippet of “Eat Your Funky Dasein.”

A still from the “Eat Your Funky Dasein” music video by artist Liam Gillick. (Courtesy Simon Critchley)

SC: “Eat Your Funky Dasein.”

AZ: Ultimately, what was the message of the song?

SC: Oh, I don’t know.

AZ: And how did it come out of this moment?

SC: Well, there’s no message. “Eat your dasein” is a phrase that [French philosopher Jacques] Lacan uses and I never knew what it meant, but I like it. “Eat your Dasein.” And then, “Eat your funky dasein” just sounded like a strange thing to say, and it kind of made sense. Then that “Feel your pain go by”—I’m thinking about that in relation to the pandemic, and just feeling that [after] what we’ve been through, we need a break. We need something simple, powerful, [and] memorable that’s going to say to us, “It’s okay, and you can have a good time. Life is not great, but it can be good fun. There’s music, which can just light things up.” I don’t know. Just to get people to feel that joy that you only feel when you’re listening to music. Because it’s something I only feel when I listen to music.

AZ: Yeah. And there’s so much about it that is about integrating this experience and owning it, and feeling it and not rejecting it, which I think is fantastic. So I think I’m going to end there. Simon, this was amazing.

SC: Pleasure, Andrew. It was good fun. Thank you. I love talking about myself. I’d be happy to do it for hours. [Laughter] Yeah, it’s great. It’s nice to be…. We’re actually [together] physically—this is not a Zoom conversation.

AZ: No, we’re physically in the same room.

SC: We’re actually physically in the same room, socially distanced, and it’s been a great pleasure.

AZ: Thanks very much for coming.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on October 2, 2020. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity by our executive editor, Tiffany Jow. This episode was produced by our managing director, Mike Lala, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.