RoseLee Goldberg

Episode 24

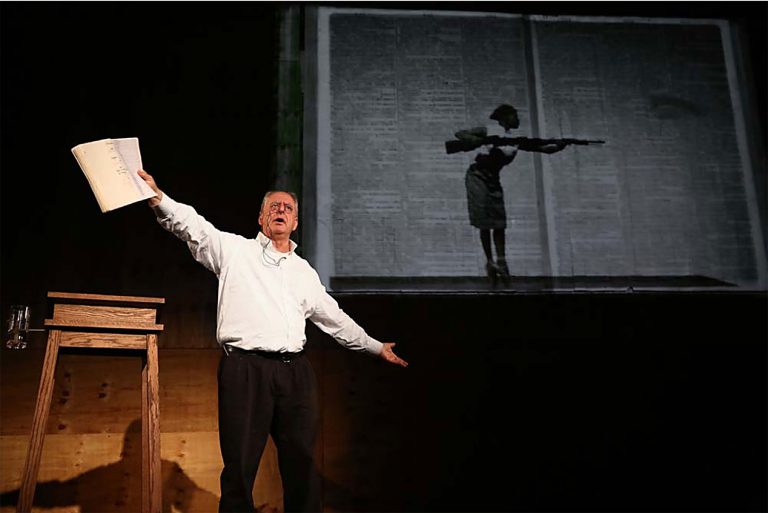

How RoseLee Goldberg Reshaped the Landscape of Performance Art

It’s safe to say that, if it weren’t for art historian RoseLee Goldberg, performance art would not be what it is today. Not even close. The founder of the nonprofit organization Performa, which for nearly 15 years has been putting on biennials of live performance around New York City, has for decades helped shape and steer the conversation about what “performance art” even is—and what, at its best and most inventive, it’s capable of achieving. A scholar, critic, and New York University professor, Goldberg has written important texts on the subject, including Performance Now: Live Art for the 21st Century (Thames & Hudson), and has established new modalities for organizing and presenting performances. Her astute understanding of the multidisciplinary medium is unparalleled.

With Performa, Goldberg has radically shifted the landscape of the field through collaborations with hundreds of artists, including Adam Pendleton (in what was a breakout moment for the artist), Yoko Ono, Rashid Johnson, Joan Jonas, and Julie Mehretu. Following previous overarching themes like Futurism (2009), Surrealism (2013), and Dada (2017), this year’s biennial, which runs from November 1 through 24, will explore ideas about the Bauhaus on its centenary year. Among the performances will be works by Taiwanese artist Yu Cheng-Ta, who will unpack Western “influencers” and reality TV culture; Gaetano Pesce, who, at the Salon 94 Design gallery, will create a studio atmosphere, evoking the typical conditions of a day, via his assistants molding, pouring, and crafting; and Bunny Rogers, who will turn various spaces at a public high school—including hallways, a gym, and an auditorium—into a “living installation.”

On this episode of Time Sensitive, Goldberg speaks with Spencer Bailey about her upbringing as a young dancer in Durban, South Africa, when that country was under apartheid rule; her adventurous journey into the beating heart of the art world, first in London and ultimately in New York; and her path to establishing Performa—and elevating performance art as we know it in the process.

CHAPTERS

Goldberg and Bailey get into the importance of slowing down and how performance art can facilitate that. Bailey recalls profound performance works by Bryony Roberts, Taryn Simon, Isaac Julien, and Brendan Fernandes.

Goldberg discusses the intersection of performance art and photography, and why she’s never one to say, “You had to be there.”

Goldberg talks about her childhood in South Africa, and how she became interested in the Bauhaus—the theme of this year’s Performa biennial—and the painter, sculptor, designer, and choreographer Oskar Schlemmer.

Goldberg looks back at her evolution in New York, to which she moved in 1975 and became a curator at The Kitchen.

Goldberg shares how she created the non-profit Performa, which started, in a way, with a project with the artist Shirin Neshat and grew to become an organization that produces a biennial and has collaborated with hundreds of artists over the past 15 years.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.tv) and Twitter (@time__sensitive), and subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Today in the studio we have RoseLee Goldberg. She’s an art historian, author, critic, curator of performance art, and the founder and director of Performa. CR Fashion Book has called her the “O.G. multi-hyphenate,” which I thought was pretty fun. Welcome, RoseLee.

ROSELEE GOLDBERG: Thank you so much. Really great to be here.

SB: Let’s start with the idea of slowing time down.

RG: Can I take a deep breath? Slow down.

Yes, absolutely. I’ve used that expression, which I think we all hanker for, as regards to Performa, which I created in 2004, officially (we launched the biennial in 2005). I was, specifically, in that case, relating to the way we see so much video performance, all new-media art. We tend to race through galleries, race through major exhibitions like Documenta. I think one year it just seemed that every single space was a very long video or installation or projection, and the reality is I don’t think any of us ever finish seeing any one of those. I think we pretend to ourselves that we’ll be back, but somebody walks over your foot, somebody’s dog runs out the room or something, and it’s not a focused, concentrated viewing experience. To me, that was one of the several items that I wanted to really look at closely with Performa, was to create performances that held you tight in every imaginable way. That really showed you an artist’s thinking, their work, and had a beginning and middle and end, even as abstract as that might be. That’s my reference to slowing down time, to look at work, to really—

SB: Pay attention.

RG: —pay attention.

SB: I like this idea of holding you tight. The notion of intimacy is so important today, I think, with just where we’re at culturally, politically, socially. It’s so hard to find intimate moments. Is that something you hope to create through what you do with Performa?

RG: Absolutely. That’s the continuation of that idea of slowing time. I really feel a responsibility that we’re making work, and I want to be able to say to anyone I speak to across a range of audiences, “You must see this work because it will actually move you. It will change the way you think about humankind.” There has to be that sense of one-on-one changing what happened to you. I think a lot of that actually comes from coming of age during so much of the conceptual art in the seventies, where you walked into a work and you came out the other side a Bruce Nauman. You walk into a corridor. The lights are yellow and you come out and the world’s turned green, and that to me is almost an idea of, how do you leave a piece, how do you come out the other side and have it be part of your thinking, part of your visceral response to the world?

SB: Right. You almost become an actor-performer.

RG: Really. There’s a wonderful quote from a friend of mine with this idea of curb-to-curb—that from the moment you step onto, into, or even near the venue, or even en route to it, there’s an experience that you’re being asked to pay attention to, and throughout that process, by the time you come out, and even maybe about the time you get home and close your eyes, there’s a sense that you’re still wondering about what that experience was.

We talk about that a lot with the artists as we work on commissions, like, “Well, what do you want somebody to feel? What do you want somebody to go away with?” These are very close-knit, intimate questions that we talk to the artists that we are working with over a long period of time, and it’s really fascinating because everybody seems to enjoy being asked those questions, and we all really take part in that conversation.

SB: Andrew recently spoke to Kim Hastreiter here on the podcast, and Kim was talking about how one of her missions and visions is this idea of creating spine-tingling moments.

RG: That’s great. Absolutely. I think I for a while I was talking about work that made me cry. I think of so much of the productions that I could refer to where I was so moved, and at one point I had to stop saying that, because it was like… Seeing Adam Pendleton stand up and give this extraordinary performance, the very first piece he’d ever done, and using a gospel choir and Jason Moran music, one of the early pieces that Jason was in for us and Performa in 2007, I would invariably say “It made me cry.” So I had to stop saying that, because I’m not a crybaby. And I love Kim [Hastreiter] saying that, and by the way, she’s actually a dear friend, one of the first people I ever met in America. We go back a long way.

SB: Yeah, we’ll get to your SoHo years because I did notice some crossover there.

RG: Yes.

SB: I was thinking about—in the research I was doing for this interview and thinking about performance art generally—some of those experiences I’ve had that have really moved me in recent years, and it’s so interesting that performance art is linked to memory in this very, as you put it, sort of visceral way, yet there’s a response mechanism. The number of galleries I’ve walked into over the past decade—I’ve forgotten so many of those shows, even if the work was great.

RG: Yeah.

SB: But I haven’t forgotten a single one of these performances, and I listed a few of them here.

RG: Go for it. I want to hear.

SB: One was in 2015—it’s actually in your book Performance Now—Bryony Roberts did a performance called “We Know How to Order,” with the South Shore Drill Team at Mies van der Rohe’s Federal Center, in Chicago.

RG: Oh. Yes. Beautiful.

SB: I heard the music from blocks away, and that was how I got there. There was no agenda. I just heard the music, and I went.

RG: Fantastic. You know, I love that we’re talking about this experience, the visceral. I’m going to go up a little, too—I think the visceral somehow always refers to somehow your gut. The visual people don’t talk enough about in relation to performance, and I spent a lot of time in my various books talking about that, how visual this material is. It’s actually also that visual impact that you won’t forget, like I’m sure as you heard the sound of the marching bands, but those pictures that exist—

SB: The way the architecture shaped the scene…

RG: The architecture. It’s the visual. I actually have realized, too, that when I see something, this visual memory is in my image bank forever, whereas, for example, I have a harder time with theater, which is about language, and I could see something that I think is absolutely riveting—as storytelling, as acting—but because a work isn’t… Not necessarily. Some, of course, are. But [since it] doesn’t have this huge visual impact, I actually don’t recall it in the same way, either. I kind of take photographs in my mind—

SB: I completely agree.

RG: —and retain these photographs forever. So I think that visual impact and the sound are those two things that really take us…

SB: Yeah. What’s interesting, [in] another one of the performances I was going to mention, it was smell for me. It was Taryn Simon’s “An Occupation of Loss” at the Park Avenue Armory in 2016.

RG: Yes.

SB: And what was so fascinating about this installation, aside from the monumental architecture [by Shohei Shigematsu of OMA], these concrete tubes going up to the ceiling of the armory, and the sound of course. The different chants and hymns and—

RG: Weeping.

SB: —ways of commemoration, was because of the smallness of each space that you went into, I can’t remember how many. [Editor’s note: There were eleven of the tubes.] I think there were maybe ten or fifteen of these concrete tubes, [each] with a different immigrant singer—or, I guess they were immigrants to the U.S. [only] for this event, but it was interesting in that you had this sort of profound experience of traveling through time in each space you went into, and each space not only sounded different—and aesthetically, you had a different appearance from person to person—but the smell. The smell was actually the thing that I…

RG: Really? That’s so interesting.

SB: I’ve brought this up with multiple people, and they’re like, “Oh, I didn’t think about the smell at all.“ But for me, that was actually… Smell is so connected to memory.

RG: So real. Absolutely. And again, what’s so fascinating about live performance is these many, many layers that you could be… That’s another element that, you know, you talk to an artist about “Maybe there’s a need to heighten the smell” or “Let’s bring sound in in a different way,” or “How are we…” Again, heightening the visual aspect of it. So, yes. It’s really this idea of touching every possible sense imaginable, and then of course we all carry huge historic reference and intellectual references and political storytelling that’s surrounding us every day. So the fact that so many aspects can be captured is extraordinary.

SB: Yeah. Aesthetically, the one that I found probably the most profound in recent years was this summer in London I went to the Victoria Miro Gallery, and there was an eight-screen video installation by Isaac Julien called “Lina Bo Bardi: A Marvelous Entanglement.”

RG: Marvelous. Absolutely.

SB: It was the most aesthetically stunning thing I’ve ever seen, pretty much. What was so amazing, I found, about it were the layers of narrative woven into this piece, which was, yes, video art, but also performance art.

RG: Absolutely. I don’t know if you know that we did an extraordinary commission of Isaac’s in 2007. He worked on it for more than three years, actually, and it was a development of several videos, and installations, and then it went live. We did that at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and also at Sadler’s Wells, in London. That involves both of what you’re talking about, this capacity to envelop you visually, to tell incredibly rich, complicated, complex stories, and also somehow bring you into the mood “stopping time,” and the stopping time there is—can you imagine spending an hour and a half with Isaac’s work in a wonderful theater as it was at BAM, at the Harvey, or Sadler’s Wells in London, and being drenched in that work for an hour? Not walking through, not being interrupted, no distraction, just spending time with your eyes literally in the excitement of visual images crossing the room and hearing music and seeing dance.

It was absolutely stunning. The pleasure of reaching those heights of keeping the viewer in one space (in my mind, locking the doors, keeping them in—but of course we wouldn’t dare do that). But spending time with an artist’s ideas is an extraordinary, extraordinary moment for us, for all of us to watch that process develop, and to arrive at that end, that you’re being invited to spend time.

SB: Yeah, time almost becomes suspended. I felt that way anyway watching Isaac’s video at the gallery in London this past summer.

The fourth standout I wanted to mention is currently at the Noguchi Museum. [Full disclosure: Spencer is on the museum’s board.] It’s Brendan Fernandes. He has a performance piece there called “Contract and Release.” It’s dance, and, so, fascinatingly, these dancers contort their bodies in such a way that they actually almost mimic or resemble Noguchi’s sculptures.

RG: Fantastic.

SB: To see dancers in such a way take something that’s so solid—stone or metal—and twist themselves in such a way that it actually becomes animated.

RG: It’s a wonderful reference. Yes. Which, just as you’re talking, brings back so many different references. Reminds me, actually, of Dennis Oppenheim talking about his early performances where he referred to almost resembling the inherent feel of being a piece of sculpture, whether you were concave or convex.

More importantly, to me, I love what Brendan’s doing and the way of using the body to actually define space and to understand the body as this visual object, slow it down, make those relationships where we’re looking at negative space, positive space. We’re actually articulating the things that you would do in sculpture, but you’re actually having the dancer internalize that, which then takes me to Oskar Schlemmer and Bauhaus performance, which of course we’re celebrating this year at Performa.

It’s the hundredth anniversary since the school began. The note there is about how important performance was for teaching dance, architecture, sculpture, space. Schlemmer had a course that he called “The Art Figure,” Kunstfigur, and again, using the body to articulate all these different aspects that we think about in the making of art. So it’s both didactic and very experiential, because if you watch carefully you can learn something about sculpture that you didn’t know you felt, and yet also have the visual pleasure of watching those contortions, as you mentioned.

SB: Yeah. Well, I’m going to return to the Bauhaus very soon, but while we’re on this point I wanted to bring this idea of photographs of performance art, the notion of frozen time, because obviously I’m flipping through your Performance Now book. You’re experiencing something that was ephemeral and happening in time, in a picture. And of course we can reference Bryony’s drill-team performance in Chicago, where I experienced it in person and then I see the pictures in your book, and I’m experiencing them in a slightly different way. Still connected. How do you think about pictures in the context of performance art, and how we interpret performance art through pictures?

RG: Such a great question. We could spend several sessions discussing this, because of course I think about it a lot. I love, just going back to your reference, flipping through the book and looking at these images. I think one thing that I really insist on now that these are images are made by visual artists. The origin of the performance that creates that image… No photographer could dream up such an image.

Also in the book, Vanessa Beecroft or Marina Abramović… Vanessa is that unforgettable image of a frieze of naked women in the Berlin building, in the Mies van der Rohe [Neue Nationalgalerie]. Not quite naked. They were in flesh-colored underwear, tights and so on. Or Marina doing that extraordinary piece of scrubbing bones and somehow evoking the horrors of ethnic cleansing. No one could come up with that except a visual artist. They’re not necessarily thinking of making the photo, but the nature of the piece is so visual to start with. Their entire being is focused on what this piece will look like.

I’ve often said that we need to learn to look at photographs. I’m sure if anyone listening, or if you studied art history, one of the things we do most of all, almost like detectives, is how to look at pictures. You take inch by inch by inch, looking at the way a painting is put together, or if you go find a Hugo van der Goes painting or a Cézanne, square inch by square inch, how is that paint put on the surface?

I would like to suggest that we learn to look at the photographs of performance, because what we learn from that is an entire civilization. If you look at the photos taken in the seventies in a loft in SoHo, you can tell from the size of the floorboards and the finish of the floorboards what date it was. It’s dating. It’s anthropology. How come everyone’s sitting on the floor? Nobody sits on the floor anymore because they’re wearing very expensive leather pants and they’re not going to crease their pants. Sitting on the floor is not really the way things go these days. My point is, as a historian, as an anthropologist, as a sociologist, you can study those photos and come up with a larger cultural picture than you ever thought you could.

I also don’t ever use… I probably do use the word sometimes, but I don’t think of this material as “documentation.” I think of it as an image in itself, and I like what you said, too, that you had the experience and then you see the photo. That’s a very interesting place to stop for a second, just to think about that, because, think of your childhood. What comes to mind are always through photographs. You don’t really remember what it was like to be two years old or three years old sitting on that pony on the beach somewhere or whatever. But you know that photograph, and you will see that over and over again, and if you look more carefully you will see all these details in the background and who was there, which cousin, which uncle, whatever.

But that experience is through the photograph, and I think we’re too quick to say that the photograph is not the piece or the photograph is merely documentation. The photograph is an extraordinary result of this work, and yes, you can look at it ten years later or twenty years later or go back to it often, over and over and over, and discover entirely new things or remember if you were there, recall new details. Or see details that you hadn’t noticed because you were there but you couldn’t be looking everywhere.

SB: Yeah. Or it’s a photo of you before your memory really forms.

RG: Yeah. So I think the photograph of performance art is still an extraordinary subject to be thinking about, and that’s of course what I think about every time I make that selection. Do I put this photo or that photo? Which one is going to allow me to tell the larger story or the more complicated story about what occurred? And again, in my looking back and back and back at that photograph, so many new ideas come up. They’re these triggers for ideas and feelings, and the photographs are phenomenal.

SB: Yeah. I think about the process that, say, a photo editor at The New York Times must go through.

RG: Yes.

SB: Considering, “Why use this photo over that one?” and then the power therein of selecting a certain image to represent a certain event.

RG: Absolutely, and then I think, seeing the Times, I’m always keeping photographs that I find [in the] Times. I have another question, but maybe I shouldn’t… Just about why suddenly this tendency to show people’s feet. Have you noticed that? Feet and hands has become something that’s trending at the moment.

SB: Yeah. I don’t know. Maybe it has to do with … Yeah, I’m not sure what that would be.

RG: Look out for it. It’s there. But yes. The photograph… Again, I think we’re too quick to dismiss the photograph as, “You had to be there.” That’s another famous line that’s come up around performance, like you had to be there, and I say, I wasn’t at the Battle of Waterloo, either, or the barricades of the French Revolution. We learn about absolutely pivotal events that change society, that change culture forever, through so many means. Through writing, through texts, through drawings, through photographs and film since the 1800s. Through rumor, through so many different ways. So I am not one to say, “You had to be there.”

I think often the audiences at any time for performance have always traditionally been very, very small, but that rumor of that event is never forgotten. A John Cage performance at Black Mountain College that everybody will refer back to as this pivotal moment—there’s barely anything there except a diagram of how the audience might have been laid out. But it’s this moment that everyone refers back to, of a certain kickoff to the sixties and seventies.

SB: Let’s talk about the Bauhaus. Obviously, that’s sort of the focus of Performa this year, as you mentioned, and you also mentioned Oskar Schlemmer, who is a central figure in this. I find it interesting that it actually is a coming full circle for you in some ways, the Bauhaus, because when you were studying at Wits University, in Johannesburg, you had a program there where it was art history and painting in a school with architecture, very much like the Bauhaus. There was this notion of looking at all the disciplines, and it was just a little later, when you were studying in London, at the Courtauld Institute of Art, that you discovered the work of Schlemmer in a big Bauhaus exhibition at the Royal College of Art. [Editor’s note: It was actually at the Royal Academy, not the Royal College of Art.] What was it about Bauhaus thinking about Schlemmer that so appealed to you?

RG: This is really the origin story of the performance and the books I’ve been writing. To backtrack quickly, you’re right. The Witwatersrand University was set up very much like the Bauhaus school. Art history and painting and fine arts was part of the architecture department, so we shared the foundation course actually that was Bauhaus’s gift to teaching about art.

I was a dancer, professionally, from the time I was very small, and I also did a fine-art degree and was painting and drawing, and really making art. There was this moment of, “What am I going to do? Am I a dancer? Am I a painter? What is it?”

I went to London, wanting to leave South Africa for all kinds of reasons, mostly having to do with politics, but also I decided to pursue art history, and discovered—it was at this moment where you have to decide what the research is. Went to a Schlemmer exhibition—actually, at the Royal Academy, not the Royal College of Art—and there was Schlemmer. I actually started reading his diaries and going through the materials in great detail, and discovered that his constant refrain was: “Am I dancer or am I a painter?” He then actually related that in a very European mind-body discussion about the difference between Apollo and Dionysus, Apollo being the god of intellect, Dionysus being the god of play and pleasure and theatricality. That became my dissertation, and that was really the beginning of pursuing an idea about the importance of performance in the history of twentieth-century art.

SB: Your personal connection to Schlemmer obviously also has to do with this idea of, yes, you had grown up a dancer. Schlemmer also had this sort of personal dilemma of choosing between dancing and painting. You’ve said, “I finally felt like I found someone who understood me.”

RG: Well, yes. There was a great sense of excitement about pursuing his ideas, and of course what he then showed us was how he could take those different elements and actually explore them and use them as part of an education.

He’s teaching young artists and asking them to think about space, so he creates very specific dance demonstrations that show us about space, like the Slat Dance. He’s really thinking about this very, very deeply, about how we move the body through these different art forms, whether it’s in color or light or shape, or moving space around. Each of his writings are very wonderful models and templates for teaching art. And again, as we talked right at the beginning about the visceral quality, making us somehow a performance more… That every part of your body is tingling with this sense of awareness, of consciousness, of space, of time, of color, of smell. That we’re actually in this process of heightening all those responses.

He has endless texts about this, and he’s also fascinating because he looks across at other artists’ work as well, and he’s unusual in his diaries. At a very personal social level, you can get all kinds of gossip from the diaries about who was doing what to whom in the Bauhaus environment of lots of really extraordinary people being gathered together in one small town. But he’s also referring to the playfulness of one side or the more theory-based aspect of another, or the idea of pure form versus the idea of Dionysian surrealism and absurdity. So he takes one through so many different issues, and each of them endlessly become another way to investigate artmaking.

Not just performance, but artmaking. How we treat color, how we treat painting. There’s this extraordinary moment whenever I go to MoMA and see Schlemmer’s painting of the Bauhaus stairwell—even that to me talks about performance and dance, because everybody seems to be en pointe. They’ve got these very pointy feet. The placement of the body going up the stairs is that each of them look like dancers, no question. Unusually also for paintings, several figures are from the back, which I guess to me is also the way a dancer more typically turns in space. You don’t very often find paintings of figures from the back.

SB: Your personal connection extends even further in that the first piece you wrote for Artforum in 1977 was on Oskar Schlemmer and performance.

RG: Yes. I’ve just recently rediscovered that piece. Wow, it’s great. It really does come around.

Very early on—and again, why does one get obsessed with these stories?—there was that identification, like I felt I really understood deeply what he was talking about and would use that. And before I discovered him, I know when I was doing painting in life class in Johannesburg, I still remember almost… Now I’m just demonstrating here … but almost like holding a part of my body in order to draw. There was this direct sense of making a body but recognizing that I could actually physically hold my own body in a certain shape, and physically—not even through a mirror—take the feel of that body and draw it.

Back to that article, yes, that was before even a book was in mind. And they also, as far as I recall, that article, too, said very seriously, “This work needs to be looked at equal to visual art as we understand it,“ because I think so often, which is again the reason for creating my first book, and forty years later, thirty years later, for creating Performa, was to say this work needs to be looked at as a serious, integral part of art history. It is not something playful and on the side. It is not a sideshow. It is a very, very important part of the evolution… We don’t like that word particularly, but of shaping and shifting art history through the last several hundred years, is where the body comes into play, and especially in the twentieth century, where most of the work we look at is multidisciplinary. But it just doesn’t get called performance. It gets called something else, like video or…

SB: Yeah. I want to go back to South Africa and your childhood there. You were growing up in Durban while the country was under apartheid rule. Talk about that experience, and tell me a little bit about your parents.

RG: It’s a very long story—a very deep, complex sense of what that meant to be growing up there. South Africa under apartheid was a police state. It was very disturbing, every minute of the day. Telephones were tapped, because to be in a privileged position there didn’t mean that one wasn’t very, very aware of every moment that was going on. Friday night, going to my grandparents for dinner, as children we’d all want to get home before curfew came on, which I believe was at 10 p.m., when all Africans had to be off the street and policemen would go running around with truncheons and arresting people. It was frightening, upsetting, very, very disturbing. My parents were—are—remarkable, deeply caring human beings.

My father was a doctor and real old-style G.P. Would get up at three in the morning to go to see patients, often in some of the apartheid closed-off areas, and my mother was always a teacher. She taught children and handicapped people, [the] hard of hearing. There was always a sense of doing as much as we could, being very concerned. A very, very deep sense of consciousness and feeling of responsibility about how we could all engage with each other.

The extraordinary side was growing up in Africa, waking up to the sound of extraordinary birds and mynas, and the hadedah birds screaming their heads off. The landscape, the music, turning on the radio and there’s a Zulu program and the most phenomenal music. Going into town—downtown I guess you’d call it here. There was still much more traditional clothing in the streets. Or going to the Indian market. There’s a big Indian population. [It was like] those gorgeous pictures you see from India, of curries and colors and saris. Again, a “multicultural” life, before that word took hold. A multicultural, very politically conscious—I think [I was] very conscious even as a child about women and men, black and white, religion, any kind of prejudice…

SB: It’s interesting, your parents seem to be very neutral, in a way, in the sense that you were given access to all these different worlds and able to be very aware of that from a young age. I understand when you were studying dance, you started as a tap dancer, you did classical, ballet. But what I found most interesting was the Indian dancing.

RG: Yes. That was my mother’s idea. She was great! [Laughs]

SB: I read that you were the only white girl in the entire Indian dance class.

RG: Right. Well, it was actually a dance concert that we did at the city hall, and I was in disguise. Again, my parents were neutral in that they just encouraged us to take off, and my mother taught in Indian school, so I had an Indian math teacher come to try and coach me after school, which was not easy, math being one of those subjects that made me very anxious. His niece was a Bharatanatyam teacher. It was immediately, “Oh. How about RoseLee starting Bharatanatyam,” which was totally extraordinary. Indeed, I studied Indian dance for quite some time and got to perform at a big concert with a lot of other children my age.

SB: It’s interesting hearing a little bit about your parents, and I can’t help but think that some of the—let’s call it “bridging of boundaries” that they were doing, you sort of discovered performance art as a vehicle to do something quite similar, to be able to bridge boundaries in a way that few other media could.

RG: You’re right, that that sense of lack of boundary or no boundary, borders between art, politics, film, music, sound, everything around us, really does come from growing up in South Africa, again because, somehow, even early on it registered to me that each of those parts of what one was looking at, feeling, seeing, was equal.

It wasn’t like, “Oh, let’s go to a museum and see an art work and separate it out from this extraordinary person standing in front of me wearing African beads” and so on. I guess that that heightened sense of looking and appreciating so many parts of what was around, and because the politics was so dire and because it was so inescapable, I think it also was very clear from early on that you couldn’t separate politics from the way we read the newspaper, from the way we looked at images, from the way you looked at people on the street. From seeing the daily life roadways, or the whole separation, the whole apartheid idea. Every one of those aspects translated into art, politics, movies, film, what everyone was looking at.

I think I might have lost your question.

SB: No, no. It makes sense.

RG: I said in some ways that last year when we bought a big South African group to Performa was really my year to come out as a South African. I think after living here for a long time I probably didn’t talk about it, but somehow recognizing what this work was and how I felt so connected to it, and that it was such a revelation to me as well, it really was time to go back in and see how much that first twenty years of my life really is who I am.

SB: Of course you, before coming to New York, went to London, where you studied and from 1972 to ’75 were director of the Royal College of Art Gallery. At, I have to point out, an impressively young age.

RG: A big surprise to me, too, when I got that job, and I think I know the answer. I applied for the position, which was director of exhibitions at the Royal College. I had just finished the Courtauld, and I didn’t really know anything about contemporary art. Schlemmer was as far as I’d gone. To their, probably, surprise—the powers that be at the Royal College—they actually invited several students to be on the interview panel. There was I, in my sailor’s pants and Japanese jacket with a big dragon on the back, meeting very highly respected—some of them literally lords and ladies who were part of the school, and about four students who were heads of various student bodies in the school. For some reason, I just said that I wanted to work with all different departments, find a way to make every department talk to each other, and little did I know that “inter-departmentalization” was the word at the time. Everyone was trying to figure out how to get the graphics students to talk to the painting students to talk to the art history and so on—

SB: And here you are with this Bauhaus-like education that you had.

RG: I talked away about how one could make this all work, and lo and behold I got the position. I still remember… Again, we won’t name names, but a dear friend who’s still a friend that has a major gallery saying, “What do you know about contemporary art?” and I said, “I have no idea, but I’m going to Venice tomorrow, so I’ll let you know.” I just took off for the Venice Biennale, for Documenta, for Los Angeles and New York, and there was my education. I just jumped into the deep end.

SB: Well, there’s something to be said, I think, about having an insatiable appetite for culture, and just being curious, period.

RG: Just being absolutely determined and obsessed, yes. And to be part of the present. I really didn’t know at that point… This was way before curatorial-studies departments, and I really didn’t know if you paid artists to exhibit or they paid you, or the economics of it—how any of it worked—but again, that first Venice Biennale, where I think I met everybody imaginable, from Germano Celant, to [Joseph] Kosuth, to Marcel Broodthaers—I met him at Documenta. And coming to New York the first time, literally my first night was at Max’s Kansas City, and there was Bob Smithson at the bar and Vito [Acconci], and New York at that time was a very small art world, so it felt like you could meet everybody in a week, you know?

SB: Yeah. So it was osmosis for you, just coming straight at you.

RG: Yes. Really just absorbing it all and being absolutely fascinated by the different… And again, coming to New York that first time, I had studio visits with Brice Marden. I went to see Robert Ryman. Just anyone when called, they’d say, “Oh … Sure! Come on by.” And possibly saying I was director of the gallery of the Royal College of Art was a nice entrée, but….

SB: Yeah. Well, and while you were there, you did exhibitions with the Kipper Kids, Brian Eno, Christian Boltanski. A pretty amazing run.

RG: It was great. We did the first “Line Describing a Cone” with Anthony McCall. I had Carl Andre come around. I had Vito [Acconci]. We did an Avalanche magazine. I came to New York and said to anyone—you know, London was very quiet in the seventies—and said, “You know, if you’re passing through, just let us know.” Christo arrived and did a fantastic slideshow, and I still remember his response, like, “Oh, you’re just a kid. We were expecting some grown-up in this position.” It was like, “Welcome.” It was fun. And you know, in some crazy way, I think I’m still doing the same programming now that I did then.

SB: Yeah. Well, so you moved to New York in 1975. This is a time of, a rich scene in SoHo. You’ve got Robert Wilson, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Blinky Palermo, Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman. That’s the world you’re in.

RG: That was the world. Amazing. And the world downtown was very confined geography, too. I liked to say we owned downtown, everything below 14th Street. People wouldn’t dare come there. There were no lights in the street. It was a really rough-and-tumble place, and we loved it that way. Indeed, Cindy and Robert wrote to me and said they wanted to get together and meet because they had read some of my early articles from London. They were very aware of what everybody was doing. So this endless conversation about what we were seeing, that conversation is really what… It was hard to resist, hard to leave, and [I was] just wanting to come back and live here forever.

SB: And it was at The Kitchen, which, you became curator of video and performance art there in 1978, that you did some of, I guess the first solo shows for Robert Longo, David Salle, Cindy Sherman… Names we all know now.

RG: Yes. Indeed. We had also the beautiful Sherrie Levine, there was Jack Goldstein, “The Jump,” which was quite extraordinary. At The Kitchen, again I just took this idea further to say that we needed to show all disciplines all the time. Small correction there, I never think of myself only as a performance art historian, but really as art and culture and the full picture at all times.

I also created a video viewing room there, the idea being that you could just hang out. People were notoriously late, so at any time you could find Bill Wegman sitting there or… Just endless numbers of people would just come and hang out in the video room.

Again, this notion of using all the different spaces. This was a big loft and a lot of different spaces for different kinds of mediums. There was a dance program run by Eric Bogosian, there was a music program run by Rhys Chatham, and we were all in on the game every morning and night and then we’d all go to Broome Street Bar afterwards for dinner or CBGB’s later. So the geography of SoHo was really part of the story, too.

SB: What do you think it was about that time? It seemed like, especially for you in the context of your career, such a rich moment coming out of London and having this curating opportunity. And, of course, in 1979 you had your first book, Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present, come out, which was a groundbreaking book for understanding performance art. It’s still in print. It stayed in print for forty years.

RG: Well, everybody enjoyed being poor, or not being rich. Antimaterialism I think was a big part of the ethos of artists, and conceptual art in the seventies was really against the marketplace. New York was bankrupt, too. That was something else. I think cheap rent, the sense of excitement of the city, of downtown, was phenomenal. To have a two-thousand-square-foot loft for $200 a month, that’s…

SB: Something. [Laughs]

RG: Something, and hard to resist, like “I want one of those. I’m coming. I’m moving over.“ The concentration of people coming from so many different places, meeting everybody—that first time I was in New York and making friends right then with Laurie Anderson or soon after with Laurie Simmons, or with Longo and Cindy and Jack Goldstein.

And the conversations were really profound, I have to say. I think we tend to get carried away by the excitement of the seventies and look at a lot of pictures, but I always want to go back to how serious the conversations were. People were really obsessed about talking about what the different concerns were, everything from post-Vietnam to what was going on in Nicaragua, and politics and conversations about feminism, and men and women. It just seemed that every time you got together, the conversation was what I found so riveting. It wasn’t just social and having fun and wearing lots of black.

SB: [Laughs] What do you think changed? Obviously in the eighties, so much became about money.

RG: Big change. My rent went from $200 a month to $2,000 a month, overnight. I think uptown discovered downtown and real estate. We have the beginning of the Reagan era, and that spills over into what was happening in England and really the beginning of another level of finance. To suddenly be on Wall Street was really shocking. People never admitted to being in finance before, whereas finance became the goal.

A really big shift, I think, high art and low art… There were exciting aspects to it. I think the beginning of cable television. Hard for you to imagine now, but that did also seem to say that everybody was going to have their own cable TV.

A real big change in economics, and we could go into that in so much detail. The beginning of another layer of collectors that came with that economics. Young collectors, the sexy kind of art world … coming almost as a relief after the very austere conceptual seventies. The conversation about mass media and popular culture. These are things that I recall endless conversations [about] with each of these artists. In the back rooms of The Kitchen we’d be watching Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman and laughing our heads off, or The Gong Show, and at the same time everybody was absorbed with [Jean-Luc] Godard and looking at really extraordinary movies.

I think, yes. This gang had a lot to say to each other. It’s very exciting.

SB: It seemed like another really pivotal moment, especially in the context of performance art and the work you’ve been doing, came at the turn of the new millennium. You did “Logic of the Birds,” a multimedia performance with Shirin Neshat in 2001. Also during this time you were developing what would in 2004—and publicly in 2005—become Performa.

RG: Yes. Thank you for starting with Shirin, because that was a big moment. Just backtracking a little on the personal level, yes. I was writing about so much performance. It’s interesting to think that I wrote that book in ’79. I didn’t know—it was like a marriage—that I would spend the rest of my writing about it, but there’s so much to say and there always is.

But coming to the 2000s, where the marketplace had become so strong and yet I was still going to performances on the Lower East Side and seeing these very rough and engaging but very often unfinished work, and still, in a sense, wondering what could occur to get that work to another level, where these very important, persistent discussions that were going on in performance could have a wider audience. And there was that sense—I don’t know at which point one reaches it—like “Can I really keep going to all these places and very underground, literally, places, and when does it grow up?” When does that work go the next phase?

So the idea to commission Shirin to do work literally came while I was sitting in Venice watching “Turbulent” [1998], and it was one of the early times they had started using the large spaces at the back. Looking at this work and just feeling, “Why doesn’t performance look like this? This is so beautiful to look at. It’s profound.”

Everyone wants to say performance is political. It is. Shirin’s work was deeply political. It was men and women, East and West, and it was beautiful. It just caressed your eyes with its visuals. It had sound that could make you weep. It was so meaningful in every possible way, and that was that moment I came back, and I knew Shirin, not that well, but I knew her, and I said, “Would you ever think of doing a live performance?”

I remember I was at her loft in Chinatown and said, “You know, you have all the ingredients. You have this incredible, cinematic choreography. You understand time. You understand how to evoke emotions, but very abstractly. I could just imagine those performers walking off the screen into the space and making a live theater piece.” She said, “Yes,” and essentially that is the beginning of the idea of Performa, because commissioning that new work, and I really—again, like my first job—had no idea what it meant to produce something. I didn’t know what it was going to cost or what it would entail.

But we went off to MASS MoCA, where we did a residency, and I’m not going to go into all the detailed stories, but suddenly we did open it at The Kitchen and I decided I knew it was too important, that I wanted that to be the workshop and not the premiere, and that we could work on it a bit longer. I had Nigel Redden come from Lincoln Center and we went for a drink afterwards. He says, “We’re taking it to Lincoln Center.” So the very first piece that I commissioned and produced went straight to Lincoln Center, essentially.

SB: Not a bad start.

RG: That was a nice start, and that was where this idea that I want to commission new work for the twenty-first century, find a way to support it curatorially, production-wise, financially, so it can really step up onto a larger stage, and work with artists who not necessarily have ever done performance before.

SB: Well, I like the idea of also sort of channeling a lot of what was happening for you in the seventies, this notion of free experimentation and ideas, and not doing something that’s all about the money. It’s not about a marketplace; it’s really about the ideas and the conversation you’re trying to start. You’ve even described, also, some of it as this notion of radical urbanism and bringing performance into places you might not expect it or bringing it to a larger audience than normally would understand it or be willing to go experience it.

Connected to all that, how do you choose the themes for Performa? In ’09 you had Futurism. In ’11 it was Russian Constructivism. ’13 is Surrealism. ’17 is Dada. This year, of course, the Bauhaus.

RG: Well, if you remember the original book, you’ll find we’re going chapter by chapter. But in fact it is tied to time. ’09, 2009 was… I called it “Back to Futurism.” I couldn’t resist. I knew that was waiting. A hundred years of Futurism, and that was that startling moment where with the futurists and the Manifesto of Futurism in 1909, really talks about this need for all disciplines to come together, to work together.

[Filippo Thommaso] Marinetti was very, very clever, both as a publicist and marketing his ideas, but also in insisting, as a poet, that he had a painter, an architect, a dancer, a theater person, a noise musician. He was really going through each discipline and ripping it apart and saying, “Let’s write a new manifesto for the twentieth century.”

I felt this complete… this identification. “Wow! He’s looking at the twentieth century, taking each discipline and just really picking it apart and saying, “How do we make the twentieth century absolutely riveting?” and saying here we are a hundred years later. We’re right at the beginning of the twenty-first century. What are we going to do similarly? That was very easy to say: 1909, 2009 we’re going to celebrate this very radical idea of bringing all these departments together, breaking it apart, and coming up with new ways of looking both at history and our own present.

So I really use history as inspiration. It’s always a touchstone. Look at that and see the amazing things that were done—how all these different parts came together—and try to compare and predict and use it as a provocation for the future.

SB: Yeah. It’s like creating new memory out of history, which is so fascinating.

RG: And what’s exciting… Just to take you through how we do that, that’s what I call the history anchor, and it’s less the theme for the biennial, although it kind of becomes that, because what’s so interesting…

Okay. I still teach at NYU using [these] techniques. You give students a reader, so we started making readers that very specifically showed why this period and why it’s relevant. We have a reader on the Futurists, all the best material that we felt was relevant to performance at that time. We did one on Surrealism, but blowing Surrealism out of the water, looking at Dakar and Cuba and South Africa and Johannesburg and not just Surrealism in Paris in 1924 in maybe three cafés. Really pulling that open, “What is Surrealism?”

SB: The multicultural idea you were after.

RG: The multicultural. Really looking around the world.

We did similarly with the Renaissance. The Renaissance came about because often, if I’m talking to a very general audience, the best way to get attention is to say, “And you know what? Even Leonardo da Vinci did performance,” and suddenly everyone goes, “Ah. Okay. Now we’re talking.”

But it’s true. He really created performances… In fact, there’s a wonderful part in his diary. It’s a letter that he wrote to Ludovico Sforza, in Milan. He’s looking for a job in the court, and he says, “I make pageants. I’m an engineer. I’m an architect. I’m a lute player. I’m a poet. I’m a performer, and I’m also a painter.” Completely reversed the way we think of Leonardo. He went through all his action type of activities and ends with, “and I’m also a painter.” We know he actually finished very few paintings.

We use those history anchors, that research, as a way of informing as many people who will listen about this remarkable history. First it informs our team, so I would say that anyone who’s worked at Performa is the best-educated in these different histories because they’ve gone through this course of “What was performance in the Renaissance?” We can hand you a reader. Performance in Russian Constructivism. And you can get that reader or I’ll take you through it, or if you saw that program you would have learned so much about that period. It’s a way of educating larger and larger numbers about the importance of live performance in the history of art.

SB: How do you select the artists that you work with? It’s been such an incredible array, from Mike Kelley to Francesco Vezzoli, Marina Abramović, Adam Pendleton—as you mentioned earlier—Sanford Biggers, Derrick Adams, Rashid Johnson of course (who you’re honoring at the Performa gala this year and, actually, who we’re going to have on the podcast later this season).

RG: Oh, fantastic. Amazing. You know, it’s very personal and initially [it] was my personal stories, and now the curators on board have been through the, let’s call it training, or understood how we work, and start to read that themselves and bring in. As with Shirin, that’s my example of seeing the work, feeling it has all this hidden, this built-in theatrical possibility and what would happen, and possibly looking at a lot of those artists and feeling, especially… Again, maybe to backtrack a little to the late nineties, where so many artists, Shirin, Douglas Gordon, Stan Douglas, Steve McQueen, Isaac [Julien]; and on projections, major, major projections with film and video installation… Again, this idea of work that is so seductive visually, that just literally tickles your eyeballs because it’s so beautiful the whole time.

A lot of the time, that’s where it begins. With Rashid, for example, for years I would say, “Rashid, I know you don’t typically do performance, but if you ever have an idea, I’m waiting. Just let me know.” It almost became this mantra. Whenever I’d see him, I’d say, “Remember, whenever you’re ready.” One year he said, “I got an idea.” I said, “What is it?” He said, “I want to do Dutchman, the Amiri Baraka play, but I want to do it in the baths on 10th Street.” As we know, those baths are pretty seedy. It’s not a spa. It’s very rough-and-ready. And we went from there.

Isaac Julien actually… That’s another one. He came to see Shirin’s production that I did, and he was at The Kitchen when we did the original workshopping. As we left, I saw him there and I said, “Isaac, you’re next. I want to work with you.” For the same reasons. That I just felt his work had the capacity to go live and to bring a whole other idea to what performance could be or performance art could be. Shirin, Isaac, Sanford Biggers, all these different people.

Adam Pendleton—I would like to say jump-started his [success]. He was very, very young. He was only 23. He had never had a major. He was just starting to show, and I’d only ever heard him once do a poetry reading, but something about him made me feel “This guy, he’s amazing. What would he do if he went live?” I think the day after his performance opened—it was literally the next day. I think it was Holland Cotter. It was almost the proverbial “A Star Is Born.” People were just knocked out to see an artist, a very, very young artist go way beyond even his own expectations. That was really fantastic.

The choosing is very personal because we work for two years with an artist, or sometimes more. Sometimes things seem to need another year or to wait til the next session. It’s very, very personal for each of us and how we work with the artists. It’s very, very engaging. It’s not like, “Oh, you have a commission. Here’s a budget. Come back in two years. This is—”

SB: Well, yeah. Performance is a different level of intimacy and, I think, high stakes in a way.

RG: High stakes is something to think about, because I recognize for everyone I speak to it’s not a dare so much as… I think my mantra there is “a hundred percent risk, a hundred percent trust,” because [it’s a] huge risk for any of these artists to say, “Yes, I’m going to do live performance and everyone’s going to come and see this work.” Yet they’re already very well known perhaps for their painting or Julie Mehretu is last year. But high risk, high trust that somehow the imagination of the artist is so profound and we will be there as safety nets and as guides and support, but they will do it. It’s this balance. Risk and trust. It’s very exciting.

SB: I want to finish on how we got here. Of course, the term “performance art“ was around in the seventies, but its origins are still sort of unknown, as far as I can tell. I’ve also read that you don’t like the term “performance artist“ or you don’t care to use it that much. I’m curious, in the evolution that we’ve discussed throughout this episode and just in thinking about what performance art even means, especially today, where we have this sort of matrix of online life and social media and the complications that come with that, what it means to be a performance artist or what performance art even means today.

RG: It’s the big question. Yes. Thank you.

Several different parts to answer there. I think performance is really major in the sense that it’s getting the attention finally that… I’ve been banging this drum for so long to say there’s a huge history. There’s enormous knowledge and information. I used to think the subtitle of Perfoma should be “We are your performance-art department,” and send that around to each museum, because I felt museums had not fully understood or recognized that material. Lo and behold, finally, mission accomplished, in that sense.

MoMA is now this week reopening with a performance studio at the very heart of the collection, and the collection has been rehung related to those holdings. My point being that actually in every contemporary art museum, performance is hiding in plain sight. It’s just being called something else. Robert Rauschenberg, [Claes] Oldenburg—

SB: You mean the Tate Turbine Hall has…

RG: The Tate Turbine Hall definitely changed that, just hugely. The museum has changed, too, along the way, of course. In the seventies, a museum was a hushed place. It was like walking to the library. You whispered, you walked very quietly. Nowadays you expect to go into this culture palace. They have lots and lots of people and—

SB: We have The Shed just north of us here.

RG: And we have The Shed.

Back to the term—it was a big term used in the seventies very specifically, so that’s another reason for me to try to find other ways… It’s not easy to find another word, because that was the name in the seventies. But so many artists who work in performance will tell you that they’re not necessarily “performance artists.”

I see Joan Jonas as a visual artist. She’s an extraordinary visual artist. We worked with film and video and drawing and painting and objects and performance. Marina [Abramović] is an extraordinary sculptor. Her understanding of space is phenomenal. Her objects are beautiful. In each case these artists also do performance but they’re also visual artists.

I try to get people to think of that more, because there’s so much dismissive… Performance is sort of weird or it’s strange, which came a lot out of a lot of the work from the seventies. Even in the seventies, “performance art” was used alongside—there were subcategories like body art, land art, autobiography, and so on. So terminology can get a little dicey there, but it works both ways. I use it, but I also try when I use it to say, “But hold on. Let’s expand it to understand it’s also contemporary art.” Seventies conceptual art is performance, so vice versa. Or if we’re talking about the so-called “relational aesthetics,” which is a complicated term to come to grips with, that’s performance by another name. All those artists are doing live pieces, but it has another message to it, which talks about the complexity of the material within that work. But it is all invariably live work.

Where are we going? Performance is, paradoxically, very accessible. On one hand, it’s like “Well, I don’t understand performance,” but actually put a person in front of another person. We’re looking at each other. We can read each other in some fashion, from all the aspects that come across: just one person in front of another. So I think it’s accessible. I think it’s more accessible than, say, an abstract painting. Someone will look at abstract painting and say, “I don’t really understand it. I never studied this. I don’t get it,” or they’ll feel intimidated to try to get it. Some people stand in front of Marina and make their own story out of that. They might not totally get it in relation to some very nuanced idea that she’s thinking about, but they have a story to tell. They can respond, and start this huge conversation, because everyone can have big arguments about it.

Performance is accessible. It can have and does now have a much larger audience. I think the general public are intrigued by what they’re being asked to think about, their surprise.

And I think the fact that it is so layered—that it allows people to talk about these complex times in which we live—is something that will hold it in very, very interesting ways going forward. Life is so complex. Every minute of every day, what’s going on politically, what’s going on in the media, what we’re reading online, the shifts, the changes, whether we’re all going to throw our phones into the fountain like she did at the end of that movie or not; this fast-moving idea of culture as sped up through technology is something that performance can really respond to.

I think all the things we’ve talked about with your fantastic questions show how rich it is and how much potential it still has. It doesn’t have to be limited in any way. It’s not limited in any way. It’s really about the imagination of the artist, and I think when people talk a lot about what’s going on and the scale of galleries and museums and art fairs—look at this conversation we’ve had. We’re touching on so much. We haven’t even touched on music and philosophy and other concerns. But performance is very, very rich that way, and I think if we were talking about the state of the art world right now, we’d have such a different conversation. I don’t think we could have gone on for this long.

SB: Well, we’ll have to have you back. [Laughs]

RG: Thank you very much. It’s been terrific.

SB: Thanks, RoseLee.

RG: You’ve really explored lots of different things. Thank you.

SB: Thanks for coming today.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on Sept. 27, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by our director of strategy and operations, Emily Queen, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.