Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Rachel Comey.

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Welcome, Rachel. Thanks so much for joining us today.

RACHEL COMEY: Thanks for having me.

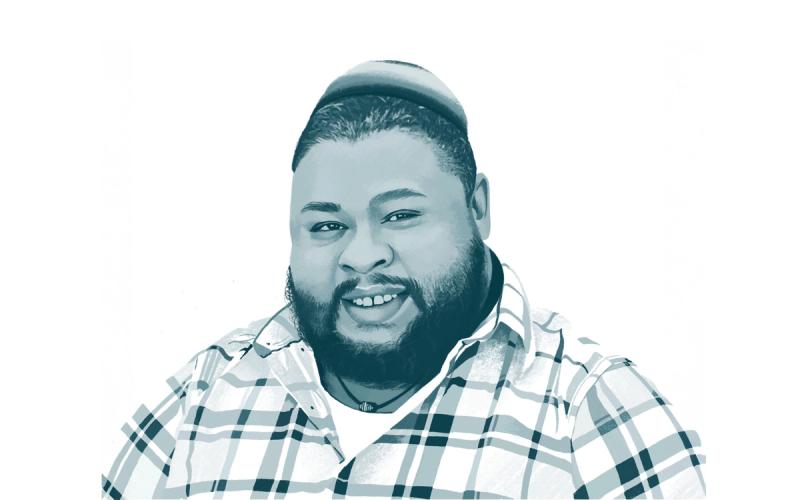

AZ: So, today I wanted to start with your recent post on Instagram, which was amazing, I think for a lot of people.

RC: Okay.

AZ: You wrote, “Finally we found alternatives to the hideous monopoly on cardboard and shipping supplies, Uline.”

RC: Oh. Mm-hmm. Right, right. Yeah. [Laughs]

AZ: Did you think it was another Instagram post? [Laughs]

RC: Well, we had a really nice one just this week about this natural dye company that we worked with, which is a smaller touchpoint than this Uline one actually, but also really beautiful and nice storytelling.

AZ: By the end of it, you write that buying a cardboard box from [Uline] is ultimately funding anti-abortion movements.

RC: Right, right.

AZ: Open gun laws, et cetera. How did you arrive at that? How long did it take? It doesn’t seem you dropped this stuff. You don’t virtue signal.

RC: No, no. I mean, it’s been a frustrating thing for me for a long time. They’re the biggest supplier of, if you’re a wholesaler in any way, or manufacturer, do any kind of shipping—even art shipping—they’re the biggest, most sophisticated supplier.

Comey’s recent Instagram post about Uline. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

I share that kind of thing when it’s useful to people. I finally found legitimate suppliers through this Refuse Uline movement, which was just a small Instagram handle. I don’t even know the people behind it, but since they were listing solid resources, I thought, “Oh my God, I can’t wait to share this with people. Everybody needs this information.”

AZ: Had you wanted to get off of Uline for a long time?

RC: Oh, for a long time. Long time. I’ve been trying, and they’re just so big and they have warehouses everywhere. When you’re shipping and every single day from some place, they just make it too easy to go to other places. So finally, we have some options. We found a place on the West Coast, there’s a place on the East Coast. So I just wanted to share it. As you can see from that post, so many other companies, and individuals, and even people not in our industry, have been reaching out, “Oh, great. We’re not doing Uline anymore either. We are going to…” So, yeah.

AZ: Well, it had this open-source quality, which is rare today for someone to say, “And here’s a solution, I’m not just going to vilify something.”

RC: Yeah, yeah. I mean, I like to be actionable about things. I can’t just share my random politics without feeling like there’s something collaborative, or informative, or potential to kind of learn from—something that I learned that I want to share, or something along those lines.

AZ: Your business is now more than twenty years old, you turned 20 last year, I guess?

RC: Yeah.

“I can’t just share my random politics without feeling like there’s something collaborative, or informative, or potential to kind of learn from—something that I learned that I want to share.”

AZ: Which is amazing.

RC: I know.

AZ: It seems along the way, at least on the outside, you’ve kept so close to your intentions. The business and the work and the creativity, all of it seems to be cohesive.

RC: Thank you.

AZ: It’s sort of values-driven, and it has never felt thirsty for scale. I think that that’s something that a lot of fashion designers, specifically people in your industry, struggle with, this idea of scale. Because a moment happens. So, how have you kind of kept it close to your intentions? How do you think about it?

RC: Well, I don’t know if that was intentional or just the way that I was able to do it. In the early days, I didn’t have access to scaling anything. I think I do now, but then it was either figure it out or don’t do it. It wasn’t like there were huge opportunities at the time. But then, I guess just kind of staying true to what we want to do and want to make. I mean, there’s been a million times and we haven’t been able to scale because of these different parameters.

A department store comes in—even Barneys, back in the day, I remember their first order with us. I was making men’s wear mostly at the time, and they wanted to buy the men’s shirts and put them in the women’s department. But my intention was that they were for men at that time. There was a specific kind of thing we were doing. They just want to pigeonhole you into this like, “No, you’re going to be the shirt person, but we’re going to do this with you.” But it wasn’t our intention, so we were never really able to go into a department store. I’m not explaining this well, but flourish in their kind of framework that they want you to flourish in. They want to pigeonhole you someplace. Like, “You’re going to be the denim brand. You’re going to be the flouncy dress brand. You’re going to be the minimalist, blah-blah-blah brand.” I never wanted to have a company like that. I like to explore creatively, silhouettes, lifestyle. There are a lot of things that I like to do and make. I don’t want to be pigeonholed into a tiny little thing, a tiny little segment.

“I don’t want to be pigeonholed into a tiny little thing, a tiny little segment.”

AZ: Well, it seems like you’ve built a business almost like an art practice. I mean, different in terms of the output, but in terms of integrity and your own narrative-driven idea.

RC: Yeah, I guess.

AZ: You mentioned how fortunate you’ve been to learn so much over twenty years in all the times you’ve spoken about turning twenty. Do you feel that you’re learning more now, or has it slowed?

RC: Hmm. No, I’m still learning I think for sure, but just different things. We’re learning a lot right now about sustainability as an example. That’s kind of an interesting one. More and more over the past years, the whole industry is learning together. Our suppliers at the mills, they have discoveries that they’re figuring out with the yarns and the traceability.. So all of that, we’re kind of learning as an industry, which is great. Then now, I’m learning a lot about data analysis, I feel like, a little bit because of all of the shift to e-commerce and how powerful that is.

AZ: Just in the last three or four years for you?

RC: Yeah, yeah. Really from the pandemic forward, it became the kind of front runner of the business and how to better communicate through there, what the tools are, all that stuff. So there’s a lot of learning there.

AZ: So as time has shifted and changed and evolved, the world culture has shifted. You’ve had to learn different things.

RC: Yeah. Yeah, for sure.

AZ: But your own intuition seems to be something that you’ve stuck to the whole time.

“I spend a lot of time thinking about my customers: their lifestyles, where they’re going, what they’re doing, how they want to feel, how they want to feel in that room, how they want to feel on that vacation, how they want to feel in their private time.”

RC: Perhaps, yeah. But I have good collaborators and I’m very dialogue-driven in the design process. As a designer, I feel like part of what you’re doing is trying to fill a need of some kind, to address it. So, I spend a lot of time thinking about my customers: their lifestyles, where they’re going, what they’re doing, how they want to feel, how they want to feel in that room, how they want to feel on that vacation, how they want to feel in their private time. And what are the fibers and the fabrics and the things that I can do to facilitate and enhance that feeling?

AZ: Right.

RC: So that’s constant—thinking around all that stuff.

AZ: Do you feel like you’ve been intuitive and instinctual with your decision-making over time? It’s something I think you’re known for is making choices and kind of not waffling. Has that shifted over time?

RC: I would say yes and no. Yeah, there’s things that happen that will hit my confidence a little bit where I don’t feel so confident in the decision I’m making. I definitely have those experiences, for sure. But the nature of this business that I’m in is that you just have to keep going.

I’ve really learned over time to just kind of keep moving. If you make a bad decision, you can recover from it, and you can evolve, and you can learn from it, and just keep going.

AZ: The pace kind of helps in terms of-

RC: Yeah, it does.

AZ: There’s a churn…

RC: Yeah, it does. I’ve always really liked that about my business versus being in an art practice where I feel like your deadlines are fewer and farther in between. I don’t know if I could spend all that time with the contemplation of the deadline further in advance.

AZ: Right. You’re just next up at bat constantly?

RC: Yeah. I just kind of learn by doing, like, “Keep going.”

AZ: Yeah. You’ve remained independent as a business, which is just an extraordinary thing, I think. Very few—

RC: Thank you.

AZ: More and more in our generation, actually, if you look at other businesses, but—

RC: You think more in our generation are independent than younger and older?

AZ: Than older.

RC: Yeah. Yeah.

AZ: There’s more independent fashion businesses, it seems like. But you’re really closely connected to designing, manufacturing, and also retail. And you have a family and you have a social life. Multitasking is a big thing with you.

RC: Right.

AZ: Well, I was over the weekend with a friend of yours who you work closely with. I asked her what it’s like to work with you, and she said something that she loves about you and your work is your boundless energy. That you would come in and say, “It’s Monday. Isn’t everyone psyched?!”

RC: Yeah, I do love Mondays.

AZ: “I love Mondays.” I thought, I wonder if she sees herself this way, and what do you love about Mondays?

“I love the engagement of different people that you work with that you wouldn’t necessarily have relationships with, if you didn’t have that job and that place. I love experiencing that.”

RC: I like working. As we just talked about, I learn so much by working. You can experience so much. I love the engagement of different people that you work with that you wouldn’t necessarily have relationships with, if you didn’t have that job and that place. I love experiencing that. And I just like trying stuff, like taking risks and let’s see what happens. Let’s go for it. So Monday’s a good time to start all of that. The weekend is for the recovery, I guess. So I feel ready for that.

AZ: Do you consciously consider time or try to remain in the moment? Do things take care of themselves naturally? How do you deal with the number of things you have to do and the need for extreme focus?

RC: Well, I make a lot of lists. I’m a list maker, that helps me. I like to multitask, but I think part of it is because maybe I can’t quite stay on one task. Maybe that’s part of my challenge that I’ve just found a workaround for. I like to just layer on the things in a practice where I feel I come back. I start something that I’m into, explore it, and then I know I need to sleep on it or rest on it to come back to it to decide if I’m on the right track or not. So I do a lot of that. That’s where the layering, I think, of multitasking is, in a way, because then I’m able to circle back, explore that thing, keep going. I guess the things communicate with each other in a way.

Rachel Comey ads in New York City. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

AZ: Right. You also made a big shift in your life pre-pandemic. You moved upstate. You left the city.

RC: Correct, yeah.

AZ: Which is a total, I guess, lucky thing. You must have been laughing when everyone else was trying to get upstate.

RC: I did feel really lucky. Well, I also know I would never have done it during that time. So I feel lucky to have been there because it was such a hard time for the business. I just don’t know that I would have been able to take that personal risk at that time when I was so busy worried about how we were going to get through that pandemic.

AZ: Right, you and every single business, especially independent ones, which I want to get into in a bit. But how has this move shifted your life? How has having kids shifted the way you’re thinking about work?

RC: Well, I think originally when you go from no kids to kids, suddenly your job becomes much more heavy in a way. Before that, I thought, “Well, if this falls apart, I can always get a job. These are marketable skills. Now I know how to do this. I know how to do that. I can get a job.” But then the farther you go into it, and then you have children, and then the responsibilities start to get a lot heavier and—

AZ: The stakes are certainly higher.

RC: Yeah.

AZ: And employees, by the way, I mean—

RC: Of course and their families. Yeah, and all the stuff that goes along with that, the health insurance and the blah, blah, blah. So yeah, it got heavier, the responsibility, but—

AZ: Moving upstate….

RC: Moving upstate. I had lived close to my store and close to my studio. When I had the children really young, that was great because I could just pop home all the time. The babysitter could bring the children to me in the office, and I could nurse them at the office and send them home with the babysitter, and go back and forth. I lived five minutes walking distance. When I would come into the door at the end of the night, I was always late. When I went back to the office, I was always late. Not late, but just, like, I couldn’t be everywhere. All the places that I wanted to be. I always felt it didn’t make a difference. So then the idea of moving upstate was like, okay, well now I have an hour-and-a-half commute. What am I going to do on this commute? There’s nothing I can do about it. So I kind of gained an hour and a half twice a day to myself in which I have a little bit. Usually I just kind of work or listen to podcasts or something. In a way, a five minute commute or an hour-and-a-half commute… I’ll buy some time, but we live in a beautiful, quiet, rural place outside of the city, with the birds and the bees and the snakes and the coyotes. I love living up there. The commute is tough.

Courtesy Rachel Comey

AZ: Well, no, I mean, it’s kind of wild that you’re still coming into the city most days. You’re commuting three hours a day. You completely extracted yourself from the life you’d sort of built your business on.

But somehow it’s benefited you in tons of ways.

RC: Yeah. On a personal level it’s great. It’s great for my family, I think. I mean, you never know. You’re always like, “The grass is always greener.” During the pandemic, like, “Oh, this town is tiny. Maybe we should—maybe my kids need more exposure.” But it’s always the opposite of what you think.

AZ: Yeah. Yeah.

RC: Question your decisions.

AZ: What are you giving your children? Are you giving them the city life or are you giving them the country life?

RC: Yeah.

AZ: Because you can’t do both.

RC: No.

AZ: What have you adopted in your life that you didn’t do in New York [City]? Time in nature? Walking?

RC: Oh, well, I mean hiking. I do a lot of hiking, which I love. Gardening, middle-aged hobbies that are very—

AZ: Exactly, I know all about it.

RC: Yeah. I make hot sauce and can our peaches and our tomatoes and stuff like that.

AZ: You grew up in Vermont, so in a way, you know this.

RC: Yeah. I grew up outside of Hartford, Connecticut.

AZ: Ah. Oh, right. You went to school in Vermont [at the University of Vermont].

RC: Yeah, and then I went to school in Vermont, but I spend a lot of time up there. I love Vermont. My parents live there part-time of the year. I do love the landscape of the hills and the mountains and everything. I find it super peaceful and energizing. It’s nice to get on the train and come into the city and just be part of the fabric of the city again. We’ll see when the kids grow up, what will happen then. Will we come back to the city more or will we stay up there? I don’t know.

AZ: Have you noticed any shift in how you’re working though?

RC: Well, hmm. Not really in a huge way. I mean, I’m always working, so it doesn’t so much matter. Before the pandemic—everything is pre and post, right?

AZ: Totally.

RC: So pre-pandemic, when I would work from home, it felt like a big deal. Like, I was working from home. But now, it just seems normal because everybody’s kind of taking the days here and there. So there’s a little bit more flexibility there. Now we’ve gotten also good at the Zoom meetings. I just stack them all up on one day, and that’s a work-from-home day. That day, I usually hike. That day, I have dinner with the kids and you know, stuff like that.

Comey as a child, growing up in Connecticut. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

AZ: What was your childhood like in Connecticut?

RC: I lived in a suburb of Hartford, just to the south. It was a classic, middle-class suburb. Running around the neighborhood with dozens of kids, and playing whiffle ball, and dress-up, and roller skating, and chalk on the driveway, and that kind of thing. So yeah, doing that—

AZ: Seems like themes and—

RC: Pre–school shooting, pre-internet. Seems pretty dreamy, I guess.

AZ: Yeah, and it seems like that sort of vision comes into your work sometimes. I mean, there’s individual pieces that will definitely feel like that nostalgia.

RC: Yeah, I think about that. I’ve talked about that before because I had teenagers that lived next to me in the seventies. There were four brothers and sisters and they were 16, 17, 18, 20, or something like that. They had pool parties and I would hang on their chain link fence and just kind of watch them hang out. The boys had big feathered hair and chains and clogs. Washing their car, really cinematic stuff. I feel it sticks with me, some of that stuff.

Comey, bottom right, with her grandfather and grandmother. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

AZ: You tell this beautiful story about your grandmother.

RC: Oh, which one?

AZ: And the pearls.

RC: Oh, the pearls, I know! Isn’t that a nice story?

AZ: Which is so fitting for what our podcast is. I wanted you to share that with us a little bit.

RC: Sure, sure. Oh my God. So, that is such a nice story. So ever since I was little, my grandmother would give me every Christmas and every birthday, one single pearl. By the time I was eight… Or then every couple years she’d strand it together and there would be like five pearls on this-

AZ: And you’d wear it that year?

RC: Yeah. We would wear it to church on Easter or something like this. My pearl necklace that had maybe five pearls on it and then this teeny, teeny, teeny little chain. Then a couple more years, I’d get another pearl, another pearl. She’d add it and she’d add it. By the time I was 12 and 13, 14 I was very much rolling my eyes about this pearl necklace that was going to take twenty years to give to me. But, I think probably when I was 18 or something like that, when I graduated high school, I had the complete necklace, which was so beautiful. I finally appreciated it in my adult life, that it actually took her twenty years to give me this necklace. Sadly, it got stolen out of my apartment on Elizabeth Street. But whatever, I still have the necklace obviously in my heart.

AZ: Have you carried this on with your own kids?

RC: I haven’t, no. Maybe with my grandkids.

AZ: Yeah. That’ll be good. And you went to boarding school. Did you wear uniforms?

RC: No.

AZ: No. But did you have a sense of style at that time? Did you—

“I was never the kind of person that was obsessed with glamor or luxury or wealth.”

RC: Oh, I was into clothes when I was younger. I was into clothes as a kid, honestly. I liked how people communicated through their clothes. How you would see people from another town or another foreign country. If there was a student that came to live and go to your school from another country, like, “Their jeans are so different. Their T-shirt is so different.” So I was always into the nuances of style, I think, and communication through it. I was never the kind of person that was obsessed with glamor or luxury or wealth. I enjoy glamor in all of these things, but it wasn’t via that—

AZ: Yeah. You weren’t interested in the labels. You were interested in the phenomena of it.

RC: Yeah, and that continued for a long time. When you go to boarding school there’s definitely some codes and things that you learn from other demographics, from this type of people, from this area of the world. This is what the rich preppies wear. This is what the hippies from upstate wear. You start to kind of… Yeah, so I enjoyed studying and unlocking that kind of thing.

AZ: But you ultimately went into sculpture and art?

RC: Correct, yeah.

AZ: What drew you to that?

“I just always liked making things. I mean, separate from the kind of communication point of clothes, I always loved materials and proportions.”

RC: I just always liked making things. I mean, separate from the kind of communication point of clothes, I always loved materials and proportions. I studied art and it just kept drawing me towards the three dimensional elements. So I studied that through college.

AZ: Then you started a company, an underwear company.

RC: Oh yeah. Oh my God. So, well after college—

AZ: Which I don’t think a lot of people know, right?

RC: No.

AZ: But that was your first business.

RC: No, no, that was teeny, yeah. That was just kind of a learning thing.

After I got out of college, and I started working first at a bakery—I was just recounting this to my husband this weekend, because we were in Vermont dropping my daughter at camp. Then I waited tables for a year after college. I was thinking about all this, about my-

AZ: In Vermont.

RC: Yeah. Yeah. After college in Vermont.

AZ: Why did you stay?

RC: I just think I didn’t know what else to do. I had a lot of friends. At the time, Burlington had a kind of growing scene, music scene and a lot of artists. A lot of them that now live here in New York that I’m still friends with. But it wasn’t even Burlington quite at that moment, because I moved south, even to a more rural area. I was just waiting tables and making art. I did some assisting for some artist up there. I was changing his oil and weeding his yard. It was the weirdest job. Just waffling around really. Then I got a job at a design firm in Burlington, which drew me back to Burlington. I got a job as a receptionist, making fifteen thousand five hundred dollars for the year, was my salary.

AZ: In ’95 or something?

RC: Yeah.

AZ: Yeah.

RC: I would work seventy-hour days just… I was the receptionist, but I would just, I don’t know. I think I discovered I loved working around that time and maybe at that place even.

AZ: Feeling useful.

RC: Yeah. Just that the things that you did had consequence and you can create something. At that time, we we moved into a new building. We created a gallery there. I started having art shows that they let me run. Then that took off in a weird way in Burlington. We had all these beautiful shows, actually. During that time is when I started the underwear company, too. My friend Pascal [Spengemann]’s mom worked in the theater department at Dartmouth [in Hanover, New Hampshire], and she made all my first patterns for me. Because she could make patterns, and I didn’t really know anything about making patterns.

AZ: Why an underwear company?

RC: Well, I just thought it would be the most basic place to start. [Laughs]

AZ: Right. Start at the first thing you put on.

RC: Start at the bottom. Yeah. I had a little concept for it. The underwear, some of them had pockets. It’s like an art project that kind of turned into a little tiny brand. I was able to learn a little bit about the process, the pattern making, the sizing, the grading, the manufacturing, the costing, whatever.

AZ: Begin working it out, and then you got to New York somehow?

RC: Then I came to New York in my later, after a few years, of graduating college.

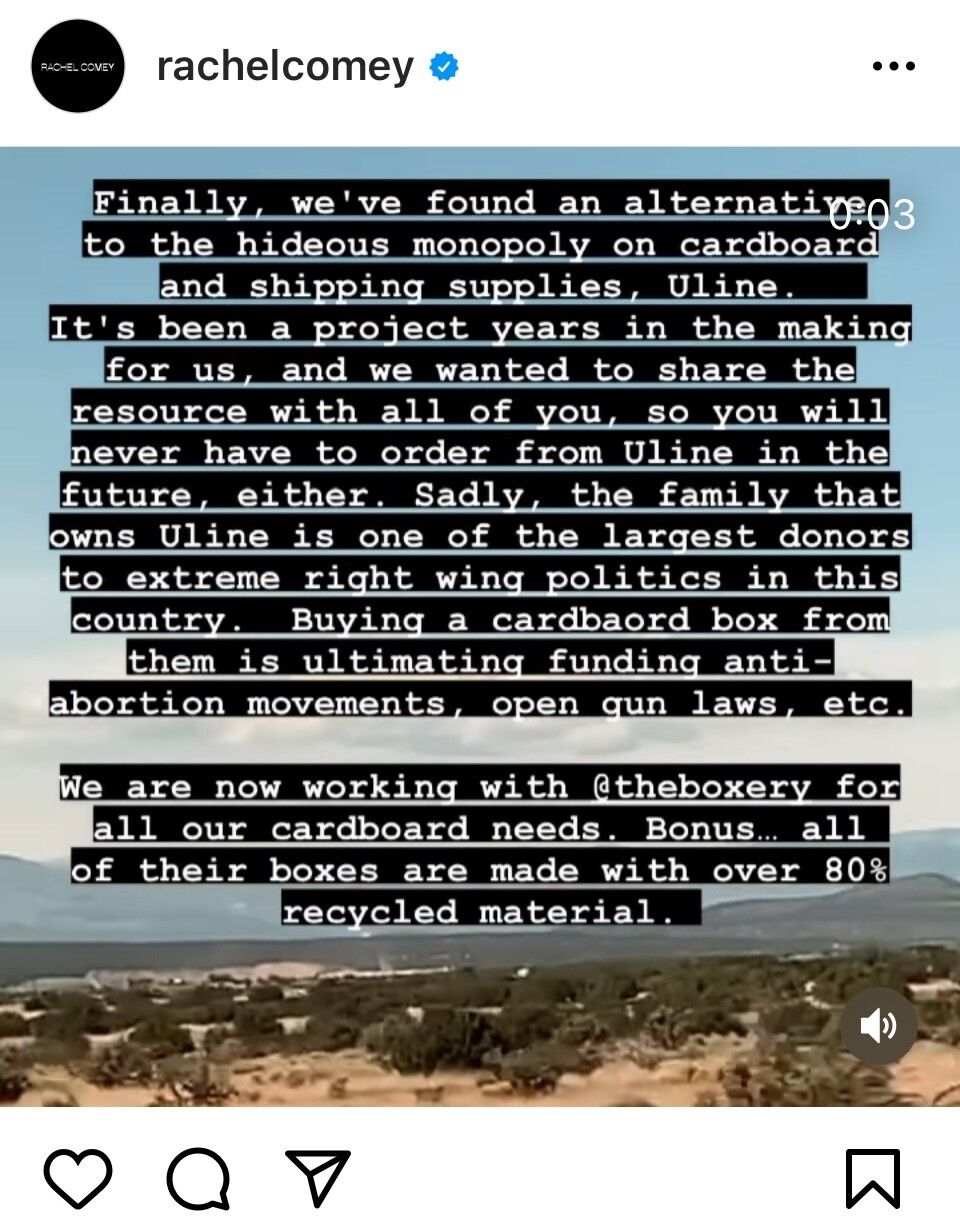

A spread from the zine Comey made for her Paris pop-up shop. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

AZ: You had a life after college in Vermont.

RC: Yeah.

AZ: It’s not like you came directly down.

RC: No, which was weird when I finally came, people were like, “Finally, where have you been?” My first job, the next day, one of these friends from college said, “Okay, I have a job for you.” I’d already had some success in my small pond in Vermont. I was running the gallery. We had press on it. It became a thing with my friend Pascal, who also has a gallery here now, but he stayed in that business. I did not. So I come down, my friend says, “Tomorrow, will you help me on this job I’m doing?” It was four hundred dollars for the day. And I was like, “Oh my God, that’s insane how much money I’m going to make tomorrow. Whatever, sure.”

So my job was to go pick up this sports car and then go pick up a model. The model got in the backseat of the car, and I was like, “Oh wait, am I a driver right now?” I just discovered, I didn’t even know what I was doing on the job. I was like, “Oh, okay. I’m her driver.” So, she didn’t speak English very well. She made me pick up her boyfriend. Then we’re supposed to go upstate to some photo shoot, like a Ralph Lauren photo shoot or something like that. She wanted me to go to Midtown and I had to circle around Niketown for an hour and a half while the photo shoot people were like, “Where are you?” I’m like, “I don’t know. The model and her boyfriend wanted to go to Niketown.” Anyway, so that was my first day in New York, was being a P.A. So I did that type of work. I mean, some of it got a little more–

AZ: But it was like gig work.

RC: … That used some of my actual skills later, like some styling and type of things.

Courtesy Rachel Comey

AZ: You got to Theory somehow?

RC: Yeah, and then so after maybe, I don’t know the years exactly, but maybe after a year of doing some styling work, and then trend scouting was kind of a thing at that time. Do you remember this?

AZ: Late ’90s.

RC: Yeah, I remember this type of job. So I did some of that type of thing. Maybe a little editorial, some theater stuff, some costumes. What else was I doing? Some P.A. stuff.

AZ: But you weren’t worried. You were just kind of doing?

RC: I don’t know. I wonder, my parents were probably worried. But I mean, I was experiencing stuff. It was interesting. I think that was one of my parameters for life in my twenties, was, “Is it interesting?” And it was, it was so exciting to be in New York. I mean, I loved it. I loved New York when I came.

AZ: Especially that time, late ’90s.

RC: It was so much fun. We were going out all the time, late, late, late, late, late out. Helping to put on exhibitions, or music shows, or did the costumes for this thing, or props for this other thing. I made this prop, like yeah, just—

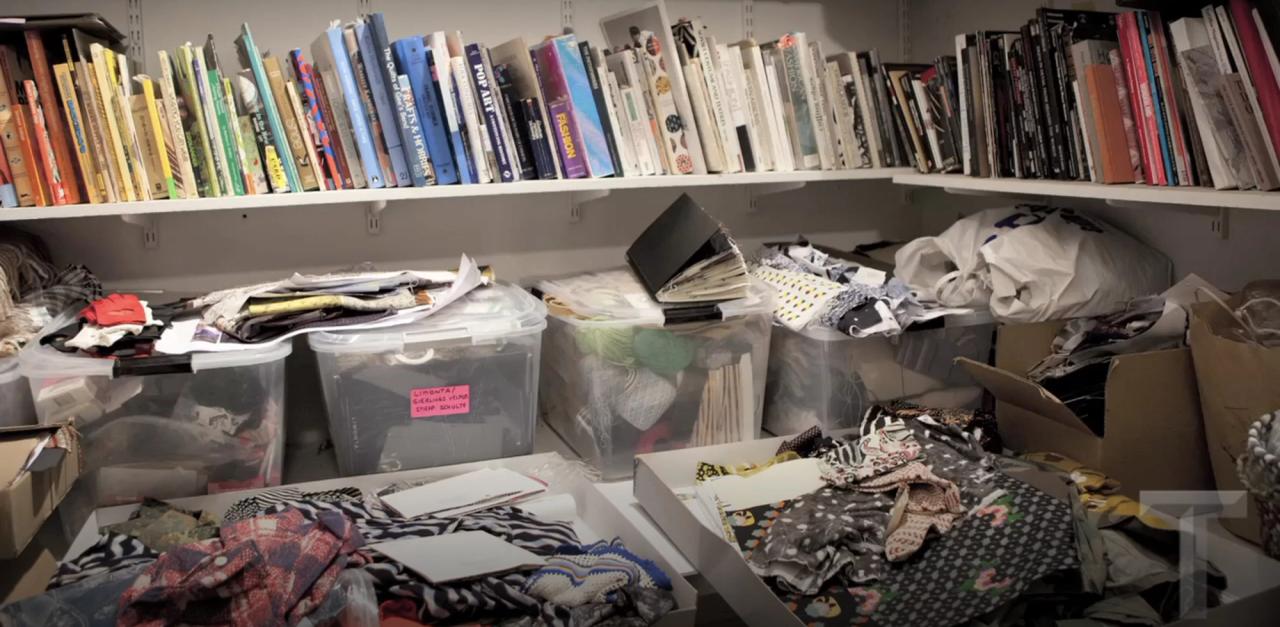

The Rachel Comey supply closet. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

AZ: You made what?

RC: I made this prop once that I was just thinking of in Joe’s Pub, for this musician, performers. I took this suitcase, filled it with wood, and then drilled little holes, and put all those matches—strike-anywhere matches—and then on the bottom of the shoes of the performer, I put sandpaper, so that he would jump on it and make little fire. I remember just whatever, stuff like that.

Then the Theory job came along. A friend of a friend was working there and they were hiring. Or maybe, even at that time I was like, “I think I gotta get a job with health insurance or something.” That might have been it. That makes sense. It’s probably that.

AZ: Right, like, “I gotta get a real job.”

RC: Yeah, like “I don’t know how much longer I can do this.” So that was that. That was the real job that I got. I was there, I don’t know, a year and a half. I don’t actually know how long, but—

AZ: And then you got fired?

RC: Yeah, I got fired. I was a great worker. I’ve always been a really good worker. It’s just, it was really, it’s pretty boring. I mean, it was somewhat interesting, a little bit, to see that side of the fashion biz.

AZ: It was the beginnings of fast fashion.

RC: Yeah. I mean, it was interesting. I had some nice bosses that I liked. It was just very narrow creatively.

AZ: You weren’t creatively doing it?

RC: Yeah. I was supposed to be the kind of color trend person, but I’d make some mood boards and suggest this or that, but it wasn’t like I had a lot of responsibility. So there wasn’t a ton for me to sink my teeth into, I think. So that’s why on the side, I thought, Oh, I’m making these costumes and things. Maybe I’ll try to manufacture these shirts—those shirts I was talking about at Barneys. So, I found this shirt maker in New Jersey, this second generation maybe, I think it was his second generation, and his name was Mel Gambert. He was about to retire. I think he had a son that worked there. Anyway, they did custom shirts for all the custom shirt type of stores that they had around the country. You could make really small quantities there. So, they helped me make a bunch of my first shirts, so that was fun.

AZ: You were doing stage costumes for Gogol Bordello?

RC: Yeah. I’m trying to think, and some others too, at the time. Different stylists were calling me at that time because of the stuff that I was doing for them and saying, “Do you have any other stuff? I’m doing this other shoot for these other people, other band.” I was like, “Sure, yeah, come and get this.” I was cutting, pasting, gluing, sewing, mish-mashing stuff together.

AZ: It was also this moment where the handcrafted T-shirt was coming out and the shirt like, they were selling three hundred dollar spray-painted T-shirts at Ron Herman.

RC: Yeah, probably.

AZ: It was this moment of D.I.Y. and fashion and kind of fucked-up, and—

“We thrifted like crazy.”

RC: Yeah. We didn’t use the word at the time, but like an “upcycling” type of mentality, you know, which I think makes sense for our generation actually. We thrifted like crazy all through my teens and college years and afterwards. We’d go to this barn up in Vermont where you just climb up on top of this mountain of clothes. Just pull out and go and buy it by the pound. Then take it back and cut.

AZ: What was that place in Brooklyn that you could do that?

RC: Domsey’s, Domsey’s. Oh yeah. I probably still have things from Domsey’s.

AZ: Which was the same thing, you could buy it by the pound.

RC: Yeah, by the pound, yeah.

AZ: And somehow you got a shirt on David Bowie?

RC: Exactly. That was around the same time.

AZ: How did that happen?

RC: The stylist, Avena Gallagher, who was kind of a friend and in the scene that we were hanging out in. She was doing David Bowie’s tour and she asked me for some items. I said, “Sure.” I gave her these things that I’d been working on. Then she called me a couple days later, “David Bowie loves them. He wants to buy them off of you. What do you want to sell them for?” And she’s like, “Charge whatever you can.” I was like, “”A hundred dollars?.” Because I’d gotten them, they were kind of transformed from some thrift-shop stuff, you know? So I thought that was so much money. She was like, “Okay, sure.” So he bought four shirts or something, and she gave me four hundred dollars cash. Like, “Here you go.” I was like, “Oh great.” I was so excited.

AZ: Then it showed up on [Late Night with David] Letterman?

RC: Yeah, and then it was on Letterman. He kept wearing the shirts. I mean, it must have been his tour look or something, but for me that was—

AZ: And that started things?

RC: … insane. Yes. Yeah, that helped. That threw some confidence my way, I guess. So then I thought, Oh, I think I’ll have a show. I think I’ll do a show. That sounds fun. What’s Fashion Week like? What’s the show? I’d already helped to put on other types of shows. Let’s just put a fashion show on. I don’t even know if I’d ever even been to one or even knew how it went. We got this, we convinced some guy with a parking garage down on Washington Street below Canal. We set up, rigged some lights up in there, and got some benches, I don’t know how. My friends helped me produce it. We just cast all of our friends. Taisa [Skulsky]’s husband, [Borys Jaramovich], was in it. So many people were in it. We just cast all the different guys that we knew. Very few models, but mostly just guys that we knew and then had a little show. It was very fun.

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Comey’s spring/summer 2017 ready-to-wear show. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

Then that was Saturday, I think. Then this showroom came to me and they said, “We love it. We think we can sell this. We’ll represent you.” That was on Sunday or something. They were like, “Bring the collection over.” “Okay.” So I bring the collection over, and, “Where’s your line sheet? How much do these cost?” I’m like, “Oh, what’s a line sheet? I don’t know.” I didn’t really know anything and so they helped me put it together. Then on Monday they had some appointments, and a lot of their buyers were from Japan. Japan loved New York at that time. It was like one of those moments when Japan was loving New York. And my—

AZ: People saying “you’re big in Japan” was the thing at the time.

RC: Exactly. The fit of our shirts were kind of skinny and more tailored, so it suited the frame of a Japanese man quite well. So immediately I got all these orders on Monday and then Tuesday was 9/11. So, market shut down, Fashion Week, the whole world changed on that day. So anyway.

AZ: So 9/11 happens and you’re like, “Wait, what the fuck am I going to do now?”

RC: Well, because I had gotten fired from Theory. So what happened with the Theory firing was that someone in the office, this gal that I knew worked at Time Out New York, and they were doing a thing, up and coming thing, up and coming designers or something. She said, “I’m going to put you in.” I was like, “Okay, thanks. Cool.” For whatever reason, she put a big picture in there. You couldn’t miss it. So then I go into work the next day and it’s photocopied on everybody’s desk in the office. Somebody had put it, somebody, I guess didn’t like me, or just didn’t like me going against the policy. The company policy that I didn’t really know about, the non-compete. I didn’t see it as competition in any way. I thought, Well, it’s kind of thriving, what’s the difference? Anyway, the owner of Theory [Andrew Rosen] came in and was like, “I’m sorry, but you should have told me, so now I have to let you go.” So I said, “Okay.” So then I had unemployment. I lived on unemployment for, and then because of 9/11 they extended unemployment, so I had eight months of unemployment to kind of help recover from, and start the business, I guess.AZ: You’re freelancing at the Gap. You’re making seventy-five bucks an hour making copies. But after six years, somehow you get out of debt and you hire your first two employees.

AZ: I guess I’m curious, having also experienced a similar thing myself was, through that period, how did you convince yourself that it was going to work? Because when you think about it now, it seems crazy. But at that time somehow-

RC: Yeah, like naive ambition. How do you get your head around that?

AZ: The risks you take now are probably so much lower than the risk you took then.

RC: Well, the stakes are way higher now though.

AZ: Right.

RC: So, I mean, I don’t know. I think that what I said earlier, where I thought, “Oh, well I’m learning, these are marketable skills. I can always get a job.”

AZ: They wipe your credit after seven years.

RC: Yeah.

AZ: That’s what I used to think. .

RC: Well I didn’t, I never had to file for bankruptcy or anything. I just kept it going, kept it moving.

AZ: But it didn’t give you anxiety? You were able to manage that?

RC: I was younger, so I don’t know. I think I felt part of a community where we were all doing stuff. We were all trying to make our way,so I didn’t feel different necessarily, than other people. I knew tons of other designers that were in my shoes. I knew lots of artists, lots of musicians, a lot of people that were just scrapping things together. I just, I find that now sometimes, my young employees when they start out, they’re so stressed out, they think they have to be a CEO tomorrow or a founder of some big deal thing. I see them with so much more pressure than I really did feel. I mean, I didn’t start my business until my late twenties, and I didn’t get out of debt until mid-thirties.

“I had a fear of failure. I think I do have that, which does keep me kind of moving, and trying, and working hard.”

I guess I had a fear of failure. I think I do have that, which does keep me kind of moving, and trying, and working hard. That’s probably part of it. And then I think the naïveté is also a key, but I think also just the community of other people was helpful.

AZ: Were you thinking about money as an equivalence to time? In terms of like, “This is as much money as I have and it’ll keep me going for this long”?

RC: Well, in manufacturing it’s hard to think like that a little bit because it’s more like, “Okay, I have this amount of orders. How am I going to front the money for the fabrics and the manufacturing before I can get paid by these stores?” So there’s a little bit of a different way of having to deal with money.

AZ: Right, because you know it’s coming.

RC: Yeah. You know it’s coming, but it could not come. They could cancel the order. They could bail somehow, which is not unusual. So there’s a lot of risks associated there.

AZ: At some point, you left showrooms and you took sales in-house.

RC: Yes.

AZ: What did you learn at that point? You were getting advice from lots of people. I’m sure it was a tough decision. What did you learn about your own decision-making?

RC: I guess to trust it. I think at that time, and I think our friend that we talked about, Taisa, she was… I kind of put out a call to friends, “Did you know anyone that wants to work in sales?” She wrote to me and said, “You know what? I think I could do it. I believe in what you’re doing and I think I could sell it.” I mean, that was huge, obviously, for someone to say that to me. A friend, especially. I think it builds your confidence and then you believe it. Then between the two of us, and then maybe at that time we probably had one or two employees. If we’re all believing in it, then there must be others too. So it’s just kind of that faith, I guess, a little bit.

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

A piece from Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

A piece from Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

The dyeing process for Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

A piece from Comey’s limited edition collection of 100% silk pieces, hand-dyed by Green Matters Natural Dye Company. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

AZ: Then cut to whatever, fifteen years later, Covid hits, where every small independent company is hyper-worried about their financial health.

RC: Yeah.

AZ: How did you manage that process and what did that feel like?

RC: That was horrible, horrible. I think I still have PTSD from that. But I mean, I wish I’d known about that PPP thing was going to come, earlier.

AZ: Yeah, we didn’t know anything.

RC: Because when we had to close the stores, lay people off during a pandemic. I mean, that’s one thing when you’re starting a business and you’re hiring people and you’re never thinking like, Oh, if a health crisis comes, I mean, you’re going to have to lay people off. Ugh, that’s so hard. Then for some, it wasn’t the worst thing. Some of the ones that we furloughed came back after we were able to open the stores again, refreshed. More refreshed, I would say, then the people that stayed on staff and were in it with me day after day.

AZ: You talk about your process as very people-oriented, design-driven. You were also in lockdown. How did you manage to stay connected to people?

RC: Well, we did an online sample sale, so we shipped pallets from my warehouse up to my house and put these three pallets in my garage. Me and my husband and the kids, we unpacked it. We had an online sample sale. We packed it all ourselves. We wrote little notes, and we just got into it and just enjoyed it. It brought me a lot of joy, honestly, to see that during this time of dark period, so much fear and sickness and just sadness, that people were buying. When I would see somebody’s order, they’re buying the sequins and this colorful print and this fun thing that we made. I think, “Oh, great. This is great.””It was so much joy for me to send it out.

AZ: While everyone was in sweatpants?

RC: Yeah, and just to know that life was going to go on a little bit, I think.

AZ: Off of that, do you think that this athleisure thing is ending and people are getting back to being dressed up? How do you feel about…

RC: [Laughs] I don’t know. I don’t know. I saw some comic the other day that said, “Oh, do you know that you can wear your yoga clothes to the gym?” I thought it was so funny. I think people enjoy getting dressed up, for sure. It ebbs and flows. I think the fact that people are traveling and moving into experiences again, that inspires people to dress. I think one of the joys of dressing for your friends, so that they experience—that you’re bringing this effort to them or something. There’s a lot of joyful dressing, I want to say, that’s happening post-pandemic where prior, I think I was focused a lot on work experiences for women. And like, “How do you want to feel when you’re in that boardroom? How do you want to feel when you’re whatever?” Depending on your vocation and your passion and outfitting that—whether you’re a chef or an artist or a lawyer or on a book tour. Just feeling like, “What are those clothes?” That’s going to be important. It’s still important. But I think that right now there’s a bit more of a joyful experience because of the coming together of family and friends again after that pandemic.

AZ: Well you’ve always focused on the complete person, how a woman feels, moves in the garment.Do you think clothing transforms someone’s experience in life?

“I spend time thinking about people that don’t like clothes. They just want it to work in this way for them and their life. If I can find a way to make those things for them, then I think that is transformative.”

RC: I think it can. I also spend time thinking about people that don’t like clothes. When I talk to them, when they struggle with it, and they just want it to work in this way for them and their life. If I can find a way to make those things for them, then I think that is transformative.

AZ: Well, seeing the other, understanding the other is something you’ve talked about as crucial to the creative process. How does empathy, if you think about that, figure into design for you? Is it part of it? Is it crucial to it?

RC: For sure. For sure. For sure. Not just the vocation—a woman’s experience, this is a woman, man, anyone—experience as they age, how their body changes. There’s lots of things to think about.

AZ: Right. But a lot of designers anchor their work in some sort of inspiration. Like, “I went to Mexico and saw this.”

RC: Oh yeah.

AZ: You don’t seem to work that way.

RC: Yeah, I’m not so themey like that, or like escapist or something. I think I am sometimes. We do a little bit of that here and there. But I think it’s a little bit more subtle ways, like, “How do you feel feminine and mature? Or feminine and relaxed? Or what if you want to dress up for a red carpet thing, but you don’t want a dress? What if that’s just not your vibe? What if you’re more boyish in your styling? What’s that look like?” So it’s just kind of getting into the different experiences, different lives, bodies.

AZ: You seem to design for your own age, in a way, or your own community. You’ve grown with that. Do you have a consumer base or customer base now that’s in their early twenties?

RC: Certain products are the gateway that you might buy first. Then you come back again, and you come back again, and you grow a little bit with the brand. I don’t even like to use the word brand that much, but…

AZ: The company.

RC: Company. You grow with our products, or you experience our products, over time because some of them are more of a stretch, more of a like, “I’m not sure if I’m ready to try that volume or this fabric that feels riskier in some way.” But if you start to trust us through some other entry, beginner products, whether it’s a pair of shoes or jeans or a sweatshirt, then you might come back and say, “Oh, okay, now I’m going to try this and I’m going to try that.” So I think there’s certain places that a younger customer might start and then as they grow with the brand. Or, maybe their mom brings them in and then the daughters, “Okay, no.” That kind of thing.

AZ: Back to the shows: You were talking about your first show, but your shows or performances have always been widely discussed. They’re always engaging the audience in some way, almost as a part of it.

RC: Thank you.

AZ: How do you think about the audience as part of the show in the same way you’re thinking about the person you’re designing for, the individual?

RC: Right. Well, I think about what experience they want to have. Like when we used to do the dinners at Pioneer Works [cultural center in Red Hook, Brooklyn] at—

AZ: At Dustin [Yellin]’s place—

RC: … Dustin’s place. For a long time, we did dinners there. At the time, that was so crazy. ”How could you expect an editor to come to Brooklyn? How can you expect them to give you three hours of their time?” Because they’re used to being like, show, show, show, show, show in their schedule. All the PR people like, “You can’t do that. You can’t do that.” I finally said, “Well, it feels right. We’re going to just try it. If they don’t want to come, they don’t have to come.” We just decided to do it. I wrote all the people I wanted to be there personally, also, and just reached out and said, “I’d love you to come. We’re doing a show and a dinner in Brooklyn. Will you come?” “Sure, sure.” Everybody said yes, everybody came.

“If I like somebody’s work and whatever they’re putting out in the world, there’s a fair chance they’re going to like mine too. That’s one thing I’ve learned over the years.”

People want to have unique experiences. So I just think that if you do it well, then they’re gonna. I think that your things that I’m into that you’re, if I like somebody’s work and whatever they’re putting out in the world, there’s a fair chance they’re going to like mine too. That’s one thing I’ve learned over the years. So if you take a risk and you write somebody that you don’t know, like you guys [at The Slowdown] did to me, there’s a fair chance that I’m going to enjoy your podcast. I was thinking, Oh, this is a, really, this makes sense, this exchange. So I think that with the shows, there’s that. The audience person is somehow somebody that I want to communicate with, or they are already communicating with me in some way, through their work.

AZ: Like High Maintenance, that’s how that happened, right?

RC: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

AZ: What’s the story on that? Because they did a whole episode.

RC: I know, isn’t that so funny? So High Maintenance, I didn’t know them. I just fanned them. One of my younger employees introduced me to it and I just fell in love with it. I love their point of view about New York. I totally identify with it. Everything about it I love, so I just wrote them to say, “I just love your work.” I just wanted to say, “Keep it up. It’s awesome. I love it.” Then they wrote back, “Oh my God, I love your work, too. Let’s meet.”

Then they came and we met a month later or something. I said, “Come to my studio, we’ll get a coffee or something.” They came, and they pitched the idea for their episode with their character. I was like, “Yeah, I’m game. Of course, I’ll do it, whatever.” So we made some clothes for Dan [Stevens], and they used some of my studio. Then they were like, “Can we get you in it for us?” “Okay.” And some of my staff. So it was just fun, you know? It’s just a good time.

AZ: That’s the kind of fascinating communication that a company can do that you can’t buy.

“I just really enjoy casting—the experience of casting and connecting people.”

RC: I also just really enjoy casting—the experience of casting and connecting people. I introduced them to some other friends that ended up in some of their later episodes. So then that’s kind of a nice, fun thing to try to do, especially in New York.

AZ: Expanding your own world in a way in exchange, totally.

RC: Yeah, and connecting people that might be interested in each other.

AZ: You follow fashion seasons, but you don’t show every season?

RC: No, we don’t show every season, but we follow the same schedule, global schedule.

AZ: I read this great quote. You said, “To show twice a year can feel a little glutinous, so I think it’s nice to slow down and step back sometimes.” Do you think this ultimately has worked for you in terms of letting it rest for a second, keeping it special, kind of go away for a second, to come back?

RC: Well, I hope so. I hope so. [Laughs]

AZ: Is that part of the drive though? Even if you, say, had the budgets to do a blowout show twice a year and everything?

RC: I think it’s a lot to try to do that. Not that I couldn’t do it. Because when you don’t have a show, it’s just as much work preparing the photo shoot and all of the materials that go into that.

AZ: Sure.

RC: But yeah, the hubbub, the press aspect of it, seems too much twice a year these days.

AZ: Right.

The Legion pant. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

RC: It’s because I’m older and it just seems like, “Boom, a year went by.” When I was younger, twice a year… Also, when I was younger, we only did two collections a year. Now we do four.

AZ: Right.

RC: So anyway. Yeah, I think it makes sense. I mean, clearly a lot of companies are just throwing the schedule out the window and doing different types of things now.

AZ: I was curious how you’ve reacted to being ripped off. Because you have been so many times, the most famous one being the Legion pant.

RC: Oh yeah.

AZ: What did it feel like to be this company with a lot of integrity, that’s doing things on their own scale, finding your own way? In this case, a very personal piece.

RC: Right. Well, at that time I kind of wished where our manufacturing could speed up, so that I could meet the demand that was out there because other companies could clearly make it happen a lot quicker than me. We make everything to order. We don’t stock a huge amount of inventory, and all of that type of thing.

AZ: That keeps you sustainable.

RC: Yeah, keeps us sustainable and just a general lower impact for everybody. But in general, it’s fine. It’s flattering. We have tons of new ideas. I don’t really sweat it, honestly.

AZ: Right. So there’s nothing that the Legion—

RC: It’s fun for it to take off, in a way, and see how it’s interpreted.

AZ: When you designed the Legion pant, it somehow had some touchpoint with your childhood? There seemed to be some connection?

RC: Yes, I can share that with you, yeah. When I was younger, me and my brothers were all on the shorter side, so my mom would hem our pants, sometimes four inches or something. Then as you grew, she would take out the hem, and take out the hem, and then it was always super embarrassing that there would be on your jeans some kind of worn line along the hemline as you grew. I didn’t like it—I was embarrassed by it. But later, when we were exploring denim at my company for the first time, that kind of experience came back to me and I thought it was a fun nod, actually, to your experience with denim in general. Because denim does hold so much history to it and nostalgia, and I think it’s fun to explore those references.

“Denim does hold so much history to it and nostalgia, and I think it’s fun to explore those references.”

AZ: Yeah, like making time visible—

RC: Yeah.

AZ: … in a way. Another thing I wanted to ask you about was when you stood up your retail [on Crosby Street], which was such a big deal in New York.

RC: Thank you.

AZ: Beautiful board-formed, concrete interior.

RC: Thank you. Oh, thank you for noticing.

AZ: Such a special—

RC: I loved making that-

AZ: … space. It really was so dynamic. The fitting rooms, I remember well, when I would go with my wife [Nicole Bergen].

RC: Thank you.

AZ: Had such a vibe, and they were kind of big, so two people could sit in them.

RC: Yes.

AZ: What were your goals with that space? Because it wasn’t a regular retail. It felt something different when it arrived.

RC: Well, after wholesaling for twelve years or something, thirteen years, your work gets interpreted by the buyer and put on a rack with a bunch of other brands. But this is kind of even before websites and stuff.

AZ: It’s like a group show.

The Rachel Comey fitting room in SoHo. (Courtesy Rachel Comey)

RC: Yeah, like a group show. So there’s no real kind of “world of,” and with that space, with our first space, I wanted to show the materiality exploration that I do in our garments and in our footwear, accessories, and everything. I wanted to do that with the interior. I loved some of those materials, like the board-formed concrete, the rocks that are on the shoe display. We hauled those back from Long Island, from the North Fork. My husband made that display. Because our apartment is right next door, so we would be down there while the baby was sleeping. He would be down there working on that, casting that concrete display. So I think the hardness, juxtaposition with some of the softness. There’s also some bits of humor, I would say, that appeal to me, and surprises. I wanted with the dressing rooms to have this intimacy. The sound, I think, is also important in there because we put that shag rug on there, so that you feel protected a little bit because the dressing room is kind of a vulnerable place. Yeah, just a lot of different thought went into it. I still love it. I think it needs a little renovation though, but—

AZ: It’s imbued with a lot of feeling, though, and that’s something really different.

RC: Yeah, but there was a lot of expectations we had for it.

AZ: How did you think about the staff? Because for the first time you had people that worked with you that were-

RC: I know, that represented us.

AZ: Public-facing.

“Having people that understand their customers, understand their bodies, what they’re looking for. There’s a lot that needs to happen in that experience for the shopper.”

RC: I know, that was exciting. I had a great store manager right from the get go who, her name was Diana [Lin], and she was just so ready to front the experience. So, she brought a lot to that at the beginning. We have a really great, interesting, diverse staff and a great retail director now. So having people that understand their customers, understand their bodies, what they’re looking for. There’s a lot that needs to happen in that experience for the shopper.

AZ: One other kind of specific thing I wanted to ask you about that you’ve done recently is the collection with Target, which I think is—

RC: Oh right.

AZ: … fascinating that you were a very kind of cool, New York brand that is not inexpensive—not wide and populous. Then you did something at Target, which they have, of course, a long history of doing [fashion collaborations]…

RC: Yeah.

AZ: What was this opportunity really about for you? Why did you take it? I mean, besides the obvious, it’s a great business opportunity. But what were you thinking about in terms of the customer?

RC: Well, in terms of the customer, and also they have an incredible staff there and they know so well what they’re trying [to do], who they’re serving, and how. They have an incredible size range, from—I don’t even know what it goes up to or down to, but it’s very broad, so it can fit a lot of different bodies. So that’s incredible. Huge opportunity. It was nice, too, during the pandemic, to collaborate with another team that was so dialed and so not phased by it exactly. That was nice to be working remotely and—

AZ: With stability.

RC: Yeah, yeah. And amazing to see the structure of a company like that. Incredible.

AZ: So before I let you go, I just want to ask, you’re turning 50 this year, right?

RC: Yes. [Laughs]

AZ: What do you love most about this period of your life, your business, this whole moment?

“I love being part of the creative fabric of this town.”

RC: I don’t know. I feel I should answer that after I turn 50. But what do I love most about my life? Well, I mean my family, my children. I love being part of the creative fabric of this town. I like opportunities like this, to meet people and explore their creative expressions. Honestly, I don’t take that time to reflect on that. Maybe I should. I’m just always kind of keep working on the new thing, the new thing, and whatever. But I probably should. I am taking a hiking trip that I’m looking forward to contemplating on.

AZ: Amazing.

RC: Yeah.

AZ: Thank you for coming in today, Rachel.

RC: Thanks for having me.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on August 2, 2022. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity by Jennifer Grant. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, and Johnny Simon.