Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Sarsgaard takes the first sip of cider off the press at his Vermont orchard.

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: When people think of Peter Sarsgaard, they think of the actor Peter Sarsgaard. Probably the villainous actor Peter Sarsgaard. Which is pretty funny.

PETER SARSGAARD: Yeah, my day job.

AZ: But there are also a lot of people—your friends, people who know you—that don’t think of you as an actor first.

PS: Yeah, I don’t think of myself as an actor first.

AZ: What do you think of yourself as?

“I feel like what acting has given me, and not every actor deals with having well, is time on my hands. Luckily, I’m someone who knows how to use that.”

PS: A lucky guy. I think of myself as someone who—I remember once being told that a lot of the great poets were people that had a lot of time on their hands. W.S. Merwin—this was told to me; I don’t know if this is a fact—had some degree of wealth. And so he had time on his hands. Or even someone like Lucian Freud had time on his hands. I feel like what acting has given me, and not every actor deals with having well, is time on my hands. Luckily, I’m someone who knows how to use that, because there are actors who don’t know how to use that, and, of course, it can become a time of wild self-destruction. I fill it with all kinds of things. Usually, what happens is, I’ll get on a jag about something, and then something else tangential will come up, and then they kind of join. I’ll try to marry music and running a small orchard. [Laughs]

Cover of the book Born to Run, which Sarsgaard had written a screenplay for and was going to direct—until the project fell apart. (Image: Courtesy Vintage Books)

AZ: I want to talk specifically about two areas of your life that you somewhat mastered—or are in the process of mastering. The first one being running.

PS: Well, that’s a very handy one in terms of my career, because the great thing about running is that you can do it anywhere, and you need nothing. It’s meditative as well as being, obviously, physical. For me, running is the time that my creative mind comes to life. Right after [a long run]—that’s a really fertile time.

AZ: You got into running because of a film that never happened.

PS: I did, yeah. I was going to direct—and I wrote the screenplay for—Born to Run, and then the movie fell apart. It was a very long, sad ending. I think part of the ending was when Caballo Blanco died. He was the main character in it, an American who was living in the mountains of Mexico.

AZ: Let’s explain what Born to Run is. Many people may not know.

PS: Born to Run was an extremely popular book [published in 2009] that was about our true nature—there is a runner in each and every one of us. We are a running people. Humans are specifically good at long-distance running because of our ability to sweat, and because we are built on two legs.

AZ: So this book comes out, you read it, and …

PS: Yup. I read it on the set of Green Lantern. I actually finished it right before a take on Green Lantern. I remember sitting there, in a huge prosthetic head, and closing the book and thinking, There’s something about this book that needs to be seen.

I’ve since worked with Errol Morris, who did this [kind of thing already], but I liked the idea of combining something that had elements of documentary and feature, because there are things in that book—some kind of convincing pop science about our origins on the southern tip of Africa, and about it getting hotter, and about being able to run down our food. The “running man” theory—[I thought] that would be great doc style. There’s a really charismatic scientist who is in the book, whom I got to know and thought would be good in the movie.

Anyway, the whole thing is now being done in a completely different way [than I would have done it]. I really do wish them luck, but—

AZ: Maybe it’s not [being done] by people who actually became serious runners in the process of trying to write this …

PS: No. So I had grown up being athletic—my dad ran marathons, but I wouldn’t say he was a sporty person. He just liked it. I think I know why he liked it: Everyone respects that time after a while; it’s like brushing your teeth, except it takes an hour, and you just walk out the door. That time is completely yours. No one can catch you. No one can walk in the room. That’s what’s amazing about it on some level, in addition to all the other obvious things. It’s also hard on your body. So yeah, Born to Run was also about how we’re uniquely adapted to do it. It shouldn’t hurt us. We shouldn’t have to wear really thick-soled shoes in order to do something that we are adapted to do perfectly well. In fact, maybe those [shoes] are bad for us. I found, though, that no matter what I did, I always had to pay attention to whether or not I was getting injured. I would say that’s probably true for almost anything you do. Even sitting on the sofa.

Sarsgaard on a hike in Vermont.

AZ: What’s the longest distance you ever ran?

PS: I ran a 50K all in one go. I also used to do this thing when my wife [Maggie Gyllenhaal] was filming in Pittsburgh, which is really hilly. I like running hills, because I like going down them mainly, but there’s some sort of payoff for hard work. I used to keep track of how far I’d run over the course of a day. I’d call it a “running day,” and I’d run to the record store. I wouldn’t be buying things, but sometimes I’d wear a backpack. I was running pretty slowly. I imagine on one of those days I would have run that or a little bit longer.

AZ: When I think about your passion for running, it happened because of this.

PS: Because of the book?

AZ: Because of the film project.

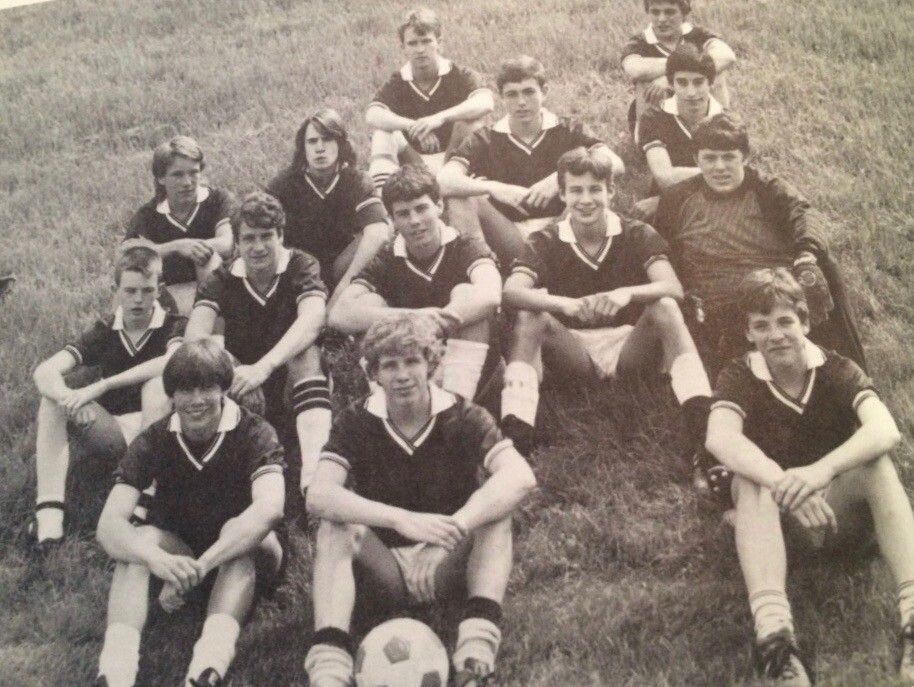

Sarsgaard, front right, on his youth soccer team, with his friend Eli Torgeson, front middle.

PS: Sort of. I think it reignited something that I had always had in me. When I was a kid growing up, I had this friend named Eli Torgeson, who I still know. At that point in my life, he was the best long-distance endurance athlete I knew. He was a kid who I just played soccer with, but he was really an endurance athlete. He would take me at, like, four o’clock in the morning on these epic runs. I’d go running with him, and he was just way better at it than I was. He was a fast runner. I looked up to him, and his ability, the way young men do with one another.

To this day, he’s someone I contact. I’m actually going to Albuquerque soon—he’s an anesthesiologist in Albuquerque. I think he won a race there running in snowshoes through the desert. He also bikes, and has won many bike races in the Albuquerque mountains. So I’m going to bring my bike down there and get crushed by him once again. But I used to have this thing—I really liked being behind someone running. It’s like having a pacer, especially if they’re a little faster. I think that’s always been a position that I’m really comfortable in. There’s something about that. I don’t like leading out; I like ducking right behind. Even if I’m racing someone, I’m the type of runner that would do that until the last ten feet, and then I’d go for it.

AZ: You took the Born to Run project all the way and developed close relationships.

PS: Oh yeah, I wrote it, did the whole thing. We had financiers, but what ended up happening—I actually met Caballo Blanco.

AZ: Who was?

PS: Anyone who’s read the book would know this guy as sort of the heart of the book. He’s this guy who lived in the mountains in Mexico. He befriended the Tarahumara Indians, who were an ancient tribe that runs. They’re called the running people, or the Rarámuri. They’re on the license plate in Chihuahua, Mexico. He ran hundreds of miles at a time with them—men, women, children. Running is one way they’ve been able to survive for so long living in this area. Before the logging roads, it was the only way to get around.

Everything has changed so much since then. But he went down there, and he just dropped out of society. This guy had no income, job assets, nothing. He started this race down there basically for those people, to try to raise money, to help them, because these logging roads were going in. Then the cartels used the logging roads to plant drugs. They basically enslaved the [Rarámuri] to mule the drugs, and it’s become a messy situation. Also, since civilization has touched them, there have been lots of problems within the community.

So he ran this race to try to help them. When this writer went down, he met him and ended up writing this book about all these racers who came down—including the best runner in the U.S. for over a hundred miles, Scott Jurek, who’s a very good friend of mine—to run this race in the mountains there with the Tarahumara. [The question was,] is Scott going to win or is the best Tarahumara runner going to win? In the end, who wins is really not that important.

I thought it was a really interesting book about the clash of modernity with the past—which we romanticize and have all these feels about. But also, it’s our past as being a people who are uniquely gifted at running—all of us, according to the thesis by Dr. [Daniel] Lieberman, who’s at Harvard and the scientist who talks about the “running man” theory. I was at a point in my life where things were going well in terms of my job, but physically, I felt like I was deteriorating. I was coming up on forty. I guess I also wanted to …

AZ: Shortly before this you were shooting Knight and Day with Tom Cruise, who also gave you a bit of advice. I’d like to hear that story. Tell me about that, because that was the predecessor to Born to Run in a way.

PS: I was shooting Knight and Day with Tom Cruise and Cameron Diaz, with James Mangold directing. We were shooting in Spain and Austria, and it was a long time. You get on location, and you’re just sort of, well—you’re not on your best behavior. So I was deteriorating pretty quickly. The type of movie I’m used to shooting is, you go in and the day is so filled in terms of making artistic decisions that you can’t actually keep up. Part of the skill I’m good at is making one and letting it go; making one, letting it go; and not Monday morning quarterbacking anything. I let everybody figure it out later, but I just go with my instinct on that movie. It was like: line up the kick, shoot it through, line up another one. And it all just felt very slow and thought-out. It was difficult for me. Those [action] movies are difficult for a lot of actors, and the ones who are good at it, god bless them. I mean, they kind of wear two hats at once.

So I was on that movie, and Tom Cruise was like—I don’t actually remember what he said then, but when we finished the movie I just went on a total dive into running. I quit drinking. I just went on a health bender. It was really stark to a lot of people around me. I think they thought, Oh my god, he’s lost his mind, because I was also approaching forty. Then, two and a half months later, it was at an Oscars party and no one had said anything to me about it. I think people were just sort of like looking at me—even the people closest to me. Tom Cruise crosses the room and goes, “What’s happened to you? Something’s going on with you.” I said yeah. And then he went, “Great.” I was like, That’s amazing that he—that’s partly his gift, being hyper-aware, a hyper-perspective of everything around him. Now, I’m sure it doesn’t always serve him. Anything you’re fantastic at is also your achilles heel.

AZ: But you knew for sure he was concerned about the state of your health.

PS: Oh yeah, totally.

AZ: And he encouraged you.

PS: I actually knew, at that moment, what all the little things he said meant, because in the moment, you’re just like, “Yeah, yeah, yeah”—I’m eating another hot dog or drinking another beer. It was at that moment that I was like, “Oh, he’s tapped in.”

AZ: This is sort of what we’ve been talking about in a lot of ways—and why I’m interested in having you on this show today. It’s this idea that projects happen, projects don’t happen, it doesn’t really matter. Because the fact that Born to Run wasn’t made may have been the greatest thing for you.

PS: Oh yeah, I’d actually say something even further. The periods where I’ve not worked as an actor, and I’ve gone through periods that are pretty long where I just didn’t work, and then coming up now—I mean, actually, I didn’t work from the end of the spring last year, maybe end of May, beginning of June, all the way through November. Then I did two weeks on a movie [Human Capital] with Liev Schreiber and Marisa Tomei that Marc Meyers directed, but it was just a little thing, and now I will start working again, on March 4, but it will be a very intense period, doing two things simultaneously. I’ll be shooting March 4 through the end of June.

Let’s just take that period over the summer. I got whooping cough, lots of stuff happened. That wasn’t great, and actually, even running-wise, physically, I wasn’t doing as well as I have been. Mainly because of the whooping cough. But, it’s like that type of hibernation, you go to another part of your mind and your mind really opens. I went to go see this guy in New Hampshire, Michael Phillips, who is, I would say, one of the most interesting guys to talk to about having an orchard. He’s an apple grower, but he’s also a teacher up in northern New Hampshire, right near the Canadian border. He has lots of interesting ideas about prophylactically enhancing the health of your trees, to protect them against disease. Instead of putting stuff on them that kills things, you’re putting stuff on them that makes bacteria and Mycorrhizal fungi grow around them, to protect them against the bad stuff. Now, that seems very technical, and I went for a workshop. I took lots of notes, and I learned lots of things. I’m sure I remember half of them at this point, but, to me, he’s a kind of artist. When I meet someone like that, I’m thinking about him and his life and what he’s devoted it to as much as I’m thinking about the information. It makes me think about my life and even the way I got into music. Sometimes these things converge, but …

A bucket of apples on Sarsgaard’s orchard in Vermont.

Sarsgaard takes the first sip of cider off the press at his Vermont orchard.

The apple press on the orchard.

Apple trees on Sarsgaard’s Vermont property.

A bucket of apples on Sarsgaard’s orchard in Vermont.

Sarsgaard takes the first sip of cider off the press at his Vermont orchard.

The apple press on the orchard.

Apple trees on Sarsgaard’s Vermont property.

A bucket of apples on Sarsgaard’s orchard in Vermont.

Sarsgaard takes the first sip of cider off the press at his Vermont orchard.

The apple press on the orchard.

Apple trees on Sarsgaard’s Vermont property.

“I’m mostly interested in everything that happens when I’m not acting. My acting is just the expression of my life.”

AZ: I wanted to get to the Bill Monroe [biopic].

PS: Yeah, the Bill Monroe project is another good example.

AZ: These are the two examples I can think of that, if asked why you act, why you’re an actor, there’s a complicated sort of answer to that. But I’d expect you to say, “Well, you know, because it’s the vehicle to learn and explore the world on my own time scale.”

PS: Yeah, but it’s also really just the end of the process. In a way, I’m mostly interested in everything that happens when I’m not acting. My acting is just the expression of my life. It happens in such a short period of time. People don’t realize this—it’s super-condensed. My gift during that time is really in letting it rip. The life I’ve been living, I’ve gotten interested in things that may either literally be something to do with the project—like I was learning about astronauts, and I’m playing an astronaut, but that’s rare. Mostly, I’ve been living my life accumulating whatever you want to call it—information, I guess. I’m cross-pollinating in a way that’s very random.

Promotional photo of Bill Monroe for WSM Radio in Nashville, Tennessee, from the late 1930s or early 1940s. (Courtesy Nashville Songwriters Foundation)

AZ: It’s random, but then there are certain things—I can think of maybe two or three that you have had the opportunity, and the excuse, to have a sort of hyper-focussed period of education on. The Bill Monroe story is …

PS: The Bill Monroe story is interesting because of who I met off of that project. Mainly, Michael Daves, of course. The Bill Monroe project came to me from the guy who was going to direct it and wrote it. He wrote the first draft. And my wife was interested in playing Bess, who was Bill Monroe’s girlfriend. So we went to Callie Khouri and T Bone [Burnett]—they’re a couple; Callie wrote Thelma and Louise. And Callie was like, “I’m going to rewrite this whole thing. I know Bill Monroe. I know the story. I got it.” And she was really on to something. Then T Bone, of course, is just a musical goldmine there. I mean, he’s the only guy that I know of who has invented an entire musical genre. It’s like, who invented jazz? A lot of people invented jazz. Bluegrass—it was Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys. They first played that music, which was developed in that Appalachian Mountains around Kentucky. It involved Scottish music and Eastern European music and shape-note singing and all kinds of stuff coming together.

I got really interested in that, and I wasn’t sure if I was going to play and sing in the movie. But I wanted to feel like I could. I was playing someone who was a virtuosic singer, and easier to play a lot of the time on the mandolin, because it’s the chop most of the time—maybe not the solos. He didn’t play like Chris Thile or anything.

T Bone first introduced me to John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin because I was in London. He was like, “I know a guy who plays the mandolin, and he’ll come down.” John Paul Jones had a lore mandolin. There are, I think, four or five of them in existence. It’s an extremely expensive object that should be behind glass. I remember he just handed it to me, and he gave me some tuners that said his name on them. He showed me how to hold the mandolin in cool ways, because he sort of assumed, probably rightly, that I just needed to look like I had some game. He was like, “You might take a knee, you might hold it out here.”

So I met him, which was really exciting—I’m a huge Led Zeppelin fan, and I’m a huge fan of him. But then I was just learning how to be a presence on stage, which I felt I could do intuitively. Anyway, when he came back to Brooklyn, he introduced me to Michael Daves, who’s a virtuosic guitarist and singer. Everyone should go and listen to him. His album with Chris Thile, Sleep With One Eye Open, is just a marvel. You can watch him play online. He’s just virtuosic.

AZ: And an incredible human being.

PS: And an incredible human being, who’s my friend now. We do midnight mass together at the local church. I’ve helped raise money with him to fix the church’s ceiling. I started taking mandolin lessons, and he was helping me sing like Bill Monroe. We went and recorded the music in Nashville with T Bone. It was a marvelous experience—everyone came out for T Bone. And Del McCoury was singing my parts some of the time. Incredible singer. I had a whole journey with it.

Then I started to sense [something was off], because the musicians weren’t getting paid and stuff. A lot of movies are put together like this, but there was a little bit of wishful thinking going on, and that’s to be kind about it. People will say they have the money so that they can get the money. Then, if they don’t get the money, and they keep saying “we have the money,” they start to get into criminal territory. This guy really wanted to make the movie. I’m sparring everyone his name because it’s not important. He was the only person who knew where the money was coming from exactly, how much there was. He was the only one.

Ornette Coleman. (Photo: Andrew Zuckerman)

AZ: But it fell apart, just as Born to Run fell apart, in a sort of dramatic way. The point is, you can run your ass off and you can play music.

PS: I can run my ass off and I can play music. Then what happened is—this is the end of that story, actually. Several years go by, I’ve been playing music. I meet Ornette Coleman. I actually played with Ornette Coleman before he died. Not in that I’m not vouching for my ability, because I played drums with him and I don’t even really play the drums, but Ornette said that didn’t matter. I went really deep thinking about music. I started teaching music to both of my children, who are both now deeply into playing music. I’ve always listened to it, and thought about it, but I started thinking about it in a way that was like, It’s not off-limits to me.

A lot of people think of music like, Oh, that’s something off-limits to me. Or even running, too. Think of any other animal in the kingdom looking at us with these crazy ways of amplifying our voices, whether it be through electronics or acoustics or whatever. They think we’re amazing, or mad, or something, but we’re clearly all hook line and sinker for it as a society. Look at the way we listen to it. We’re all knowledgeable about it, even on the most simple level. And running. What you say to a room full of children: Who in this room runs? And they’re eight years old. Every hand goes up in that room. To a full room of adults, suddenly, it’s, like, two people. I think there’s a story there that’s worth exploring.

AZ: Well, they’re both hooked into time.

PS: Yeah, and about getting back to our true nature as people.

Anyway, I do that, and then this movie comes along that I did, The Sound of Silence, which just was at Sundance. It seems like it’s successful. I have a hard time deciding.

The reaction has been extremely positive about it. The movie is so archian. It’s about a person who’s mapping out the route-tonics of every neighborhood in Manhattan, and believes that sound is affecting our everyday behavior and that the way to be happier is to try to manipulate it so that suddenly, you know, you’re vibing an A-flat minor in your apartment instead of a G-major or some cacophonous cord. He’s trying to help people this way. I really do think that it’s just all I got into, the idea of that movie, because of where my head was at, because of that other movie a long time ago.

AZ: Human connection.

PS: Yeah, it’s like I dropped bluegrass on some level. Which I still love. I mean, I’ve always loved all kinds of music, but then I started thinking about this idea of who we are as people and our relationship to sound. That abstract idea also really interests me.

AZ: Well, with running as well there’s this interplay between loneliness and human connection.

PS: Yeah.

AZ: In both music and running.

Sarsgaard showing a video on his iPhone of a flute player, whose breathing he enjoyed, on the New York City subway.

PS: Yeah, and breath in much of music, and much of running. I mean, the guy that I showed you that I listened to on the subway this morning. I don’t love his flute playing—it’s fine. His flute playing is really an excuse for his singing, and one of the things that’s really cool about his singing, I can tell as an actor, is the way that he uses his breath. He’s very clever about really supporting it, and it’s irregular. It’s wild to watch him.

AZ: I want to talk about two other things that are also about time, and are deep areas of your life that I think came later than running and music. These are your current passions: gardening, or just generally growing organic material, and writing. I want to hear from you about these two areas of your life in terms of time. I think about “earth time” with gardening. Tell me a bit about—

Sarsgaard in his Vermont garden.

PS: Gardening is all about time. It’s literally about when you get your seed packet, and it says “This takes one hundred sixty days to grow” or whatever. I’m not going to grow it in this part of the world, but you are deeply connected to a sense of time and change, especially up here in the northeast, where the seasons are so dramatic.

A vegetable garden, to me, is nice because it’s popular in your family, because you have something to show for it. I would also say perennials I get mostly interested in because that’s a plant that you’re dealing with year after year—you’re coming back to it. Maybe you’ve done something to help it, maybe you’re just watching it, but to see that type of change happen [is fascinating]. Most people think it’s really slow, but it’s actually remarkably fast.

I planted some pear trees two years ago, so this year I might take one piece of fruit from them. Then, the next year, there’s going to start to be fruit, and that’s when you first plant it—you start to think, Oh, it’s going to be four years until I get a pear. That seems not even worth it, but then I guess I don’t view the event as the pear. I see the event as the continuation of the whole thing, all the way up to when it dies. I even had to take down an apple tree because the person who planted it there didn’t anticipate how wet it was going to be in that spot. So I took it down. But I actually took some amount of joy in doing that, because I turned it into wood chips, and I put it on the other apple trees. There is nothing an apple tree likes more than that because it’s the Mycorrhizal fungi. Living with a piece of property over a period of time, and making it not just more fertile to you but to everything around you, [is important in this context]. I think that’s also because I’m in the middle of the National Forest. I’m thinking, These bears are really going to like this pear tree.

AZ: This sort of bifurcation of your time now between the urban environment, where you normally live, in Brooklyn, and up in the National Forest, north of New York, you’re using it to garden, you’re using it to live your life, basically, and to connect deeply with nature. But you’re also using it in this new practice you have, which is writing—not that it’s that new, but you have been writing [quite a bit lately]. I want to hear from you a bit about writing in general and how you think about time on the page.

PS: Writing is actually the first thing that I ever got psyched about in my life. It was the first thing I was ever told I was good at. I was really really poor student—I mean, like a “let’s have him evaluated and see what’s up with him” poor student.

AZ: You moved twelve times as a child. We’re going to get to that shortly, but let’s stay with the writing. We’ll unpack your childhood in a second.

PS: I took a test to get into high school where you had to write, and they reacted so positively to it that they put me in all these fancy classes that I didn’t belong in, because I still was a poor student. I could just write well, but I knew I could write well because people started to respond to it. It’s something that I actually have done in private almost the way that some people play music in private—they never do it publicly. I’ve done it privately for virtually my entire life.

Only recently—what you’re talking about is recently—I’ve been encouraged by a lot of people around me to write something, and then share it with them. I’ve shared my writing over the years with, like, one person here or there, but very, very rarely. I really like the practice of doing it. I think, to a lot of people, that’s hard to understand, but to me it’s probably how knitting would be to someone. But it’s more involved than that because my child knits, and that looks like a meditation. Writing is sort of an alternate world that I can go hang out in—that I’m writing quite literally. I just love the way it’s like a dream that you can control and live in. I really do fully submerge into it when I’m doing it.

“My perception of time gets as altered [when writing] as it would if I were on LSD. It’s that strong for me.”

It’s interesting that you mention time, because my perception of time gets as altered [when writing] as it would if I were on LSD. It’s that strong for me. Of course, one of the greatest things about writing is that time is completely up to you. You can take three hundred pages to write about five minutes or you can take five pages to write about three hundred years. It’s completely up to you as to how you do it, and both are completely satisfactory. You can mix the two, and that’s usually what a decent writer does.

For me, as a kid, it was almost something I did in the way that somebody else might watch a movie. But I actually didn’t watch that many movies. I read books, but I would rather write.

AZ: You’re finding that, to be truly creative, you need to slow it down in the writing process. Not that you can’t write quickly, because ideas come and you can’t get them on the page as fast as they’re in your brain.

PS: Well, I can because I took typing.

AZ: Oh, so you’re a good typer?

“I think that every kid out there should be taught touch typing. I see them pecking [at their smartphones], and I’m like, That’s no way to live.”

PS: I have to say, I think that every kid out there should be taught touch typing. I see them pecking [at their smartphones], and I’m like, “That’s no way to live.”

AZ: Voice recognition is getting pretty good. So we just have to talk.

PS: Okay, typing is not the same as talking, though.

AZ: No, it’s not. I mean that you need to not be involved in multiple activities; you need to slow down and get into a specific space. Time needs to shift a little bit when writing.

PS: Yes. I would say, if I were getting paid by the hour for writing for things that I might one day show, I need to feel really compelled in order to show it to people. Otherwise, I just think, Well, that’s something I did for myself. But I do have something that I am working on now in which I’ll end up doing that. If I think about the per-hour rate, it’s unfathomable. It’s next to zero.

AZ: It’s this idea that Einstein talked about: time being this illusion, and the theory of relativity, from 1915. He predicted that time passes more quickly when you’re high up than if you’re nearer to the earth. So if you had a twin and—this was from Carlo Rovelli’s book The Order of Time …

PS: So if they were at the top of Mount Everest, and I was at sea level …

AZ: You guys would be a different age.

PS: Is that like centripetal force being away from the earth’s surface or something?

AZ: Your sibling would be slightly older than you now, but there isn’t this absolute true time. There are multitudes of nows.

“We’ve all felt time go really fast and felt it go really slow. The only way we have of dealing with the world is through perception.”

PS: It’s so funny, my daughter and I talk about this all the time. She actually just wrote a play that’s sort of like a Samuel Beckett play. It’s all about time and words. But we talk about time all the time in my house. To me, it’s completely obvious that it’s something that’s not an absolute—but is perceived. We all know it. We’ve all felt time go really fast and felt it go really slow. The only way we have of dealing with the world is through perception. If there’s an absolute, nobody knows about it, nobody’s experiencing it, so why deal with it?

AZ: Well, there’s this thing that’s happening. We’re hearing about it a lot now, and we’re all clearly thinking about it, but it’s this sort of weaponization of time, this sort of violence of it, through the smartphone, through technology and the convenience economy. We’re living in this Amazon convenience economy.

PS: That’s actually something I dropped out of over the summer. I drop in and out, but yeah.

AZ: You drop in and out of technology? One of the things I admire about you is that you don’t believe in too much for too long.

PS: Exactly. It’s not like I’m a Luddite, like I’m going to dismiss all of it and walk away. I do that so that when I come back I can appreciate what is actually valuable, because there’s such a flood of all of it. I go to what is actually valuable.

I started carrying my phone again, partly because then I can video the guy on the subway. Because, for a while, I wasn’t, and I was like, “Oh, I would really like to share that, because that’s cool” But if you’re just using [your smartphone] to look at the latest CNN, whatever happened, then we’re all just like [puppy sounds].

AZ: I think your relationship to technology is completely related to your protection of your own time. Technology becomes, at times, a sort of villain against your own sense of time.

“People run with headphones on, listening to a podcast, because they think that they’ve just gained an hour by doing something that could have taken two hours. But I would say you’ve just lost everything because you’ve experienced neither as completely as you could have.”

PS: What’s interesting is the way that everybody tries to do everything at once. It’s called “multitasking” or whatever. People run with headphones on, listening to a podcast, because they think that they’ve just gained an hour by doing something that could have taken two hours. But I would say you’ve just lost everything because you’ve experienced neither as completely as you could have.

AZ: I wanted to come back quickly to your origin story. You were born on an Air Force base in Illinois. And you’re an only child. And you moved twelve times.

PS: From birth until I was eighteen, yeah. My dad worked for three places. He worked for the Air Force. Then he worked for—wait for it—Monsanto.

AZ: Brilliant.

PS: Wonderful place [sarcastic tone, referring to Monsanto]. I think he saw what was going on at Monsanto and split. And then he worked for IBM, which also stands for “I’ve Been Moved.” Those three places are all famous for sending people everywhere. It’s not that I grew up on Air Force bases all over the place; it’s that I had a father who was extremely good at computers. He was a valuable person during that time.

“I’ve always thought of St. Louis as being an important place for me for some reason.”

What was interesting is, I think I’ve always thought of St. Louis as being an important place for me for some reason—[my daughter] Ramona just read Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. I was like, “Hannibal is right there—I was born right there.” I really connect with that character; there’s something I’ve always liked about Samuel Clemens. I understand how there’s some dated stuff, including race, but there’s a fundamental feeling about being American that I really identify with. Because of my last name, it’s funny, people frequently think of me as being Scandinavian. It’s way, way back—my parents are from Mississippi, and they met in Mississippi. My dad went to Mississippi State; my mom went to the Mississippi University for Women. They dated in college. I really connected with that feeling: the Mississippi River, St. Louis, the heart of the country, some interesting modern architecture there. St. Louis was culturally vibrant.

AZ: You learned how to hang out with yourself.

PS: Totally learned how to hangout with myself. I moved to Oklahoma—I lived there for a year and a half, I think. For one point, I had everyone call me John, just because that’s my first name: John Peter Sarsgaard. But my dad’s name is John, so we never called me John. I just thought, I know we’re not going to be here for long. I’m going to try out John. I fought in Oklahoma. I messed around in after-school brawls.

AZ: How old were you?

“Luckily, my parents, god bless them, never defined me.”

PS: Ten or eleven. My first and only fights were in Oklahoma. This was right at the end of an oil boom. DeLoreans were rusting out on the sides of the street. There were lots of homeless people. It was not a good time for Oklahoma. My dad actually always says, “Thank god IBM had this thing where, if they moved you, they would buy your house and be responsible for selling it.” They had bought it, had an appraiser come. They bought it at the appraisers’ value. My dad was like, “There’s no way we would have gotten half that.” He was psyched. We moved from there, and, uh, what was after that? Ridgefield, Connecticut. In Connecticut, everybody played lacrosse. There was a whole “style” thing going on, with polo shirts, collars up, and music that I wasn’t aware of.

I value having all of that time, tons of time by myself. I would frequently have an [influential person], whether it be Eli [Torgeson, with running] or this guy Andy Flynn, who helped me really explore music that I wouldn’t have known about. I would frequently find those people who were local, who would be my tastemaker. That’s what I really got into: Who’s going to be the person to give me the inside? Andy Flynn took me on my first trips to New York City. He had a girlfriend in the Bronx, and we would go down. My first trips to New York City were all to the Bronx. I saw The Pogues play there. But I didn’t end up a lifelong Pogues fan. I was, for a moment, a Pogues fan. I still respect them. But it frees you up, because the people around you, I think—even the people that love you—define you. And when they define you, it can be like a cage. Luckily, my parents, god bless them, never defined me. They were like, “Who knows what the hell’s going on with Peter?” A lot of people thought of me as a soccer player. I never identified as an athlete. I just thought soccer was something that was incredibly beautiful. I thought of it as one of the most beautiful games I’d ever seen.

AZ: [You were also] informed by your ballet training.

PS: Exactly. I’m really into balance, and I’m really into what they call proprioception. That understanding, of where my body is in space, has made it so that I feel perfectly comfortable running down the stairs in the dark, because I’ve known those stairs a million times.

AZ: You studied modern dance.

PS: I performed here in the city with Meredith Monk. These are all little rabbit holes that I got down.

The whole [soccer] thing was really about proprioception; it was really my connection with a ball, and whatever angles I’m touching it at in space, sending it to someone who’s going a speed behind me, toward an open space, to have it land in the right spot. If they hit it one touch into the goal, it’s … beauty. If we won because of slide tackles, I hated it. I hated it so much I thought about quitting it all the time. I would say a lot of things are like that for me. Like acting. There were times where I went through hating it so much because it wasn’t beautiful, meaningful, or valuable. I couldn’t find the value, in this manifestation in it, and that’s where I’d say I actually become a professional. I know what to do to just patch this up a little bit.

AZ: You go all the way from Mississippi and Illinois and St Louis and all these early spaces you pass through, then you find yourself at Bard College.

PS: I went to Bard College for one year, and I was a completely different person there than most. See, I was never a hip person. I did lots of interesting things, but I didn’t have an outside me looking at me. I didn’t think about my personal style, or what I looked like. I was guileless and that way for a long time, until I met my mentor. Which happened at a certain moment. I actually think right around Boys Don’t Cry [in 1999] is where I started to think about what I looked like.

AZ: Which is where I was getting to. It’s interesting that you bring up [Boys Don’t Cry].

PS: The people I met during Boys Don’t Cry—and even the topic of Boys Don’t Cry—were something that I only became aware of because I went to Bard, because at the all-boys school that I went to in Connecticut [Fairfield College Preparatory School] nobody talked about transgender anything. Nobody there would have watched this movie. And I probably, when I read it, would have made head or tails with what was going on with it, except that I went to Bard, met lots of people who were all over the map in terms of gender, and even now it’s something that I don’t feel like I understand quite as well as my kids do. For me, it’s something new still.

So yeah, when Boys Don’t Cry came along, those were like Bard people to me. Kim Pierce, it was like, “Oh, you’d be at Bard.” Kelly Reichardt was at Bard. Stephen Shore was at Bard. Lots of interesting artists were there who I got access to, and became—this is just a quick aside. When I listened to Patti Smith’s book about coming to New York—

AZ:Just Kids.

PS: The way that she talked about seeing Cézanne and the masters and all of that, if you’re knowledgeable about art, if you’re sophisticated about art—you can see me asking, what is the guilelessness about her? It’s a naïve point of view, where you can look at a Van Gogh and go, “Oh, it’s a beautiful picture,” instead of saying, “Oh it’s a Van Gogh, I’ve seen it a thousand times.”

AZ: Van Gogh [jokingly said in a snobby pronunciation].

PS: Van Gogh. [Laughs] So I was still in that guileless place for a long time, where everything was fresh for me, until I think that was all the way up until Boys Don’t Cry, where I met a pack of people that were super-aware of a cult of cool, and of the way you appear. Not just what you wear, but the way you act in that clothing. The way you that you could have a persona. That glamour is an illusion.

AZ: But it never really stuck for you.

PS: I was never good at it.

AZ: Yeah, but you never wanted to be.

PS: It never interested me enough to do it myself. It was interesting enough that I hung around it for some period of time. I mean, like Sonic Youth is really interesting: sometimes, they sound good; sometimes, they don’t sound good. But even when they don’t sound good, they’re interesting.

AZ: Doing Boys Don’t Cry and playing [ex-convict] John Lotter was certainly a turning point for you. When I think about that film, I think about you playing a kind of despicable human being. But somehow, as the audience, you don’t think of that person as despicable, and that dissonance is where the beauty of that role and that film really is—

PS: John Lotter was such a familiar person to me. When I read it, in some way he was the only familiar person in the script to me. I didn’t know anyone like Brandon Teena, and I didn’t know anyone like Chloë [Sevigny]’s character. But I knew plenty of these guys, and and I had hung around them. I had also hung around people that did morally reprehensible things, despicable things, bigoted things, and because I was where I was at the time, I didn’t say anything. Sometimes, my wife actually says, I bait them into being even more authentically who they are, and I do think I do that I think. I will see just how far it goes instead of trying to change their minds about something they’ve believed forever or even shaming them. It’s a kind of curiosity that I have.

I once met this guy, a driver in Louisiana, and he said, “You wanna see the Lower Ninth Ward?” It was after [Hurricane Katrina]. I said, all right. He was driving me and my wife around. The way he was talking about it made me say this: “Was the hurricane a little bit like a cleansing for this neighborhood?” And he said, “Yeah, it was a cleansing, and this neighborhood’s never coming back, and you know what, it’s not such a bad thing, those people shouldn’t have been living there, we don’t need those people here, and New Orleans is better for it; it’s smaller, but it’s better.” And then you read about the way the people were shot on the [Danziger Bridge] and go, “Oh, that’s where that comes from.” This is hardcore. This isn’t like—you have to get curious about bigotry, you have to get curious about racism, in order to know how to deal with it.

AZ: This was Sacha [Baron] Cohen’s career.

PS: Exactly, except I do it with no …

AZ: You just do it socially. You don’t ever do it when anything’s recording.

PS: No, no, no. So yeah, when I read John Lotter[‘s lines], I said, “One hundred percent I can play this.” I also thought to myself, stupidly, Too bad no one’s going to see this movie.

AZ: You were wrong about that. Another turning point was Shattered Glass. One of the things that sticks in my mind about Shattered Glass is when I first noticed your ability to do absolutely nothing and create stakes on-screen.

PS: Well, that’s called good writing. That’s also working with Billy Ray.

AZ: I mean, when you don’t say anything.

PS: Right. That’s because I know, as an actor, that the mechanisms—the tsunami of the plot, the structure of what’s behind me—requires me to do nothing. Doesn’t mean I have to do nothing; it just doesn’t mean I have to do something.

What’s great is when you work with a real pro—Billy Ray is a real pro with the writing and directing—you have less responsibility. I’d say the thing I’m good at knowing is, yeah, I’ve been writing stories to myself since I was a kid. I know, gosh, I’m writing a story right now, where I just started to realize there are twenty pages in it where no explanation was necessary, because I had created such a strong tsunami of inevitability behind the story. You can know, as a storyteller, that that’s a time you can just lay off.

AZ: You’ve done a lot of theatre beautifully. Three amazing Chekhov experiences: Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters, The Seagull. It started with The Seagull.

PS: I would clarify and say, regardless of the quality of what they were to anyone, they were three great experiences I had. People like things, people don’t like things, but I’m certain that the experiences were great to me.

Sarsgaard starring as Hamlet on Broadway in 2015. (Photo: Carol Rosegg, Courtesy Classic Stage Company)

AZ: And then you did Hamlet. I bring up Hamlet because of another sort of experience in your life, where you were able to really stretch time through the process of preparation. How long did you prepare for Hamlet? Or, better question, how long was the Shakespeare book on your person?

PS: Oh, a little over a year. I just carried it with me all the time. I’d read it on the subway. I would linger for weeks at a time over a section, and I knew the whole thing. I would read the whole thing maybe twice a month, but then daily I would jump ahead and go, how about that scene where he talks about the handwriting? To me, the most interesting parts about it were the ones I didn’t know the answer to.

AZ: The final thing I wanted to talk to you about—and I saved it for last—is politics.

Back to what you were saying about how our friends, or the company we keep, are almost like the aggregate of our portrait: it’s like the roadmap to our life in a way. You’ve had some pretty interesting political friends, and the one I think of as being the most interesting, if I was going to put a hierarchy on it, is Jeremy Scahill.

PS: That’s exactly who I thought you’d say. And I’ve actually kind of preformed for him on his podcast. I read those NSA papers—internal NSA documents, which were just unbelievable. [Laughs] I mean, if you can laugh at Guantanamo, which is very hard to do, but …

“To give all of us the opportunity to be artists, to be able to grow an apple, to try to learn a musical instrument—all of these things, I think, are not the side part of life. I think of them as the main part of life.”

AZ: What have you learned from your time with Jeremy?

PS: The very interesting thing about Jeremy is, in a time where everybody’s on one side or the other, Jeremy will criticize a Republican or Democrat almost in the same breath equally. Jeremy is no great believer in the drone strikes of Obama, and Jeremy certainly is no great believer in anything that Trump does. But when I think of Jeremy, and as I go back to the Catholic Worker Movement he springs out of, and some of the literature that he’s given me, and our conversations about Thomas Merton, and to why he does what he does, there’s no amount of this frothing, gossipy, vicious rankor if you listen to his podcast. Sometimes, he seems like he’s enjoying what he’s doing on some level, because he really believes in it. If you get him in front of a room full of people, which I saw in Bushwick [in Brooklyn], he is a fantastic motivator. No matter what you believe, you can find something in what he says. He’s really defending not just America, but peoples’ right to happiness, actually.

He and I were once talking about Helen and Scott Nearing, that book The Good Life that they wrote. These are people who, during the Depression, dropped out of society, because it was too hard to live in the city. The price of an ax got a piece of land in Vermont, in an area that was not particularly valuable, and they really structured their lives with almost no money, to live a happy life doing what they wanted to do. They lived off the land, but they tried to make it easy. They had other people come and take the maple syrup off their trees, and make them maple syrup, and they got a cut of it in exchange for letting them use these trees, which they had gotten for the price of an ax. This idea of “the good life”—that we are all entitled to the good life, and what is the real way that all of us, not just in America, but how we can make sure as many people as possible across everywhere has an opportunity to have a good life? It doesn’t mean the rich life. Helen and Scott Nearing were not wealthy, but they had time for love. They had time for music. They had time for all these things.

Which brings us back to what I say W.S. Merwin had: because, I was told, he was raised wealthy, he had time for poetry—who else can write a poem like that? Who has all the hours in the day to walk around thinking about it and not worrying about their daily sustenance? To give all of us the opportunity to be artists, to be able to grow an apple, to try to learn a musical instrument—all of these things, I think, are not the side part of life. I think of them as the main part of life. Acting, to me, is like the manifestation of all that I do the rest of my time. But it’s just the tip of the iceberg, hopefully. Wouldn’t it be great if more people had the opportunity to have that?

I really want to stress that that I’m not talking about money, because I really do think—and I know—some people up in Vermont, where the Nearings were in and around, that live on very little but are putting their energy toward their children, their spouses, the land around them, whatever floats their boat, whatever makes their mind expand.

AZ: I think that’s where we’ll end.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown‘s New York City studio on Feb. 6, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by our director of strategy and operations, Emily Queen, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.