Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Monique Péan. (Photo: Noel Manalili)

SPENCER BAILEY: Today on Time Sensitive, we’ve got jewelry designer, artist, and activist Monique Péan. Welcome, Monique.

MONIQUE PÉAN: Thank you for having me.

SB: Let’s start with the fact that your jewelry, objects, and sculpture work explore time, cosmic history, and geology. You have a fascinating mind when it comes to thinking about these sweeping, far-reaching temporalities. You’ve said that you like working with fossils because they’re capturing tens of thousands of years at a time, if not hundreds of millions of years at a time. How do you think about time in your work?

MP: It’s a really interesting question that I am constantly grappling with, and I think it all stems from having lost my sister. I was 25 and she was 16, and she passed away in a car accident. She was about a minute from home, driving. It was the day that everyone was celebrating Halloween.

I think about it constantly. Sometimes you’re physically in an environment, and you might be having a conversation with someone, but you’re not one hundred percent present because you’re thinking about other things. I find myself often contemplating time, on a day-to-day basis, thinking about her, thinking about what could have been, what should have been.

That constant yearning to have her back, or to potentially want to trade [places] with her, and to realize how much she wasn’t able to experience in life, has had a significant impact on my work and wanting to understand where we come from, the universe, and the creation of time. That led me to this exploration of taking time to think about what it means to live a successful life. That took me a few months, and I realized that, for me, it’s not necessarily about how much money one makes, but much more so about, while we’re here on Earth, during the time that we have, are we using it wisely? And before we go, are we making this world a little bit of a better place?

“I had this desire to start living my life in a very different way.”

I took time to think about what I’m really passionate about. I’m very passionate about the arts. I’m very passionate about culture, and nature, and I had this desire to start living my life in a very different way, where I could create space and time to explore the things that I truly am passionate about, because I don’t know how much time I’m going to have.

Sometimes I live my life in a very bizarre way, because I make these split-second decisions and I jump all in—and I think sometimes my husband is, like, “Really? We’re doing that?” I’m like, “Yes, we are!” Like when I called him on my way back from Antarctica, and I said, “I’ve now been to six of the seven continents, and we need to go to Australia immediately.” He said to me, “What do you mean by ‘immediately’?” I said, “Next week. Let’s go.” And we did. We dropped everything and we went.

Péan visiting with a Native-Alaskan hunter in Shishmaref, Alaska. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Time for me is—I’m constantly exploring it with regards to my work. I first started after my sister passed away, and I did a complete 180 and went from the world of finance to exploring the arts in different mediums.

I went up to this small village called Shishmaref in Alaska. It’s about thirty miles south of the Arctic Circle. You can see time disappearing, and climate change happening, before your very eyes. It made such an impact on me, when I went there. I spent time with these Native-Alaskan communities, [its] Inupiat and Yupik communities, who are really known as some of the world’s environmentalists. They’re so respectful of nature, and of culture, and appreciate time.

They have these fossils, which they’ve been collecting for generations, that they introduced me to and exposed me to. It opened up my whole world, because I realized right then and there, when this Native-Alaskan Inupiat welcomed me into his igloo, and as we sat in his living room—which was also his bedroom, which was also his kitchen, which was also his studio—there were carving tools and there were hunting tools. He opened a small little plastic bag, and he took out fossils that were hundreds of thousands of years old.

Marcia Bjornerud’s 2018 book Timefulness. (Courtesy Princeton University Press)

To think that, in this small little bag, he had these relics, these incredible pieces that were capturing time—it was really a spectacular moment for me. I started thinking about what these pieces represented and how I could incorporate them into my work, and [ever] since, I’ve just been traveling around the world, trying to find unique materials that are vessels that can transport one back in time.

SB: Like portals.

MP: Completely.

SB: This got me thinking about the phrase “timefulness.” There’s a book of the same name by Marcia Bjornerud. I don’t know if you’ve heard of it, but it’s basically the idea that there’s a power that comes from thinking about time like a geologist does—so understanding time through rocks.

In [the book], she writes about the geologic time scale, this sort of deep-time map that’s put together by paleontologists, geochemists, geochronologists, and others, and the immensity of this geologic time as something that most of us kind of ignore, day-to-day, sadly. I’m wondering, how do you think about the geologic time scale? You’re obviously using a lot of these materials in your work that speak to time through geology.

MP: I have to go purchase that book immediately.

[Laughter]

I think “timefulness” is just fascinating. I think that we’re constantly yearning for an understanding of where we come from, and how the universe was formed, how life was formed, how we got to where we are here on Earth, and what the future is going to entail.

“We’re constantly yearning for an understanding of where we come from.”

These fossils and specimens that I work with are clues that scientists are able to break down, think about, inspect, and research to help us have a better understanding of where we are and where we come from and where we’re going—and what we can do to slow down the negative effects of our day-to-day actions. And hopefully, through biomimicry, improve and figure out how we can interact much more positively with our communities.

“I do find that when I spend time with these fossils or these extraterrestrial materials, [I] can be transported.”

When you start to slow down a little bit—which sometimes in New York City, can be very challenging to do—and you think about materiality and you think about the time that’s frozen within these pieces, it’s calming, and there’s an incredible energy. I’m not a religious person, but I do find that when I spend time with these fossils or these extraterrestrial materials, [I] can be transported. They just help you to pause and to transcend into a different place. To think that the universe is 13.8 billion years old—what does that even mean?

SB: Right.

MP: How do you contemplate that, and how do you start thinking about how our solar system came about, and how life was formed on Earth? At the rate that we’re going, will there continue to be human life on Earth?

Fossilized walrus tusks sourced by Péan. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

I think when you start to spend time with these materials, and explore them, and hold six billion years in your hand, you start to think that you can play a greater part in creating the world that we want to see—not just for our children, but also for ourselves. I’m very interested in that relationship between science and art and nature. How do you bring that all together within the built environment?

SB: There’s a line from the book I referenced that says, “If more people understood our shared history and destiny as Earth-dwellers, we might treat each other and the planet better.“ This idea of a shared history, I think, we need to talk about more, and that idea of shared history comes—

MP: And we all come from the same place.

SB: Yeah. And it comes also through a lot of the materials you’re using, which we’ll get to, but include fossilized dinosaur bone, pyritized dinosaur bone, fossils, walrus ivory—I mean, these are amazing materials that tell a lot about shared history, not just with the actual physical planet, but with living beings that once existed here.

Could you talk a little bit about this idea of understanding time through rocks? Precambrian time is almost ninety percent of Earth’s history. We’re mere specks in the grand scheme of things.

MP: Completely. When I first went to the Arctic Circle and started working with these Alaska Native hunters—they find these fossils that come in and out with the tides when they go hunting. They’re seafaring people. And [on the surface of] these fossils, depending on the minerals that they’ve been exposed to over tens of thousands of years, if not hundreds of thousands of years, minerals [have] permeated the tusks and the fossils, and create these incredible hues. Many of them look like nature’s Mark Rothkos.

When I spent time with these Native Alaskans, they welcomed me into their community, and they started showing me these fossils that had been passed down for generations. When you start to think about objects, and what they can mean to someone—it’s really amazing that these fossils are their art, in and of themselves, that they collect and that they’re proud to share with you. Many of [them] are pieces of fossilized woolly mammoths that are 150 million years old.

Péan visiting Easter Island. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

That was where I started to think about time through fossils, and then, that transported me back 150,000 years in time, and I thought, How much further can I go? What does that look like? How can I continue exploring temporality? It took me back to the Jurassic period. I had this yearning to begin traveling the world, specifically looking for sustainable materials that would allow me to explore temporality and culture, and immerse myself in different cultures.

Sometimes we can become so jaded. But when we have the opportunity to go to a country that we’ve never been [to] before and immerse ourselves in a culture that is foreign to us, time, in a way, freezes, or goes backward, and we become just as open-eyed and yearning for understanding as we were when we were children. I realized that I could do that through rocks. So, [I began] traveling to Easter Island and working with cosmic obsidian and learning from the local Rapa Nui people, and thinking about how you can learn about culture through materials.

“Time can, in ways, be so fleeting, and then, in some ways, it can kind of seem like it is never-ending.”

The dinosaur bone is just so incredible to work with. I mean, life is so fragile. But also to hold 150 million years in your hand, and in ways, have it be encapsulated and frozen, but in other ways, to know that it could crumble within a moment if you were to drop it. It’s very interesting that time can, in ways, be so fleeting, and then, in some ways, it can kind of seem like it is never-ending.

SB: I was just thinking about how, in a way, these objects are sort of memorials.

MP: Most definitely. Not only do they capture the past, and the specific animal, or moment in time, but also what was happening during that time, and I think that that is just really fascinating to even just try to begin to unpack.

SB: You were mentioning travel, and you’ve done all these material-searching trips in countries including Japan, Norway, Easter Island, Antarctica, Guatemala, French Polynesia. Tell me about these trips. Why do you go on them? What’s the process while you’re there, and how does time shift for you during these trips?

MP: Time moves so quickly here in New York City—not during the pandemic, but previously. Going on these trips is an opportunity to slow down, to be much more present than I am day-to-day: to really take the time to take in my surroundings and to learn from others, to look at the relationship between nature and the built environment, and look at architecture and geometry within nature, and to explore. There’s an opportunity to try to encapsulate or freeze the experience that I have through my work, and bring that all together through form and structure, and that tension that exists between nature and structure.

Each trip is so distinct. I’ve had my studio for the past fourteen years, and there have been so many unique experiences. Some of the moments that I’ve had from these trips have equated to the best moments, I would say, of the last fourteen years, whether it’s being with Native Alaskans in an igloo, or traveling with scientists and glaciologists and marine biologists in Antarctica, and seeing these incredible glaciers that are calving and flipping over because of climate change.

An iceberg seen by Péan on a trip to Antarctica. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty” (1970). © Holt/Smithson Foundation and Dia Art Foundation /Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (Photo: Nancy Holt. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York)

SB: Another interest of yours is art and culture. I’m interested in the timelessness of some of this work, like the architect Tadao Ando, or I know you’ve mentioned Nancy Holt’s “Sun Tunnels.” You’re involved with Dia Beacon. Walter De Maria is another interest, [as is] Isamu Noguchi. Could you talk about minimalism and art and where that comes into this picture for you? How do you think about time in relation to these works, and also how these works connect to nature?

MP: My mother is an artist, and I’ve always been fascinated by all mediums of art. When it was raining outside, she would always give me an art project. Or if it was sunny outside, we would do an outdoor art project. I grew up in the Washington, D.C. area, and the Smithsonian [institutions] are free, so we were always going to different museums. I grew up around art, and I love it.

An oil painting by Péan’s mother, Gail. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

My mother is definitely a collector. She has so many things, that I think that I had an adverse reaction to that and said, “I just cannot live with this many things!” I think less is more, for sure, because life can be so complicated. I have a yearning to live in a pure, minimalist environment, and to try to live a much more minimalist lifestyle, which is challenging. I find peace looking at abstract and minimalist work.

Conceptualism is really fascinating, because it sometimes can be less about the finished work, and much more so about the idea. I’ve tried to explore that and capture culture through my work in different mediums, exploring these relationships that exist through people and nature and time. Like, how does one bring that together, that conversation between Earth and cosmos?

Nancy Holt, Walter De Maria—the list goes on in terms of artists who are really creating spaces of contemplation for the viewer, to not only think about where we are [and] help us to slow down and be more thoughtful, but [also] give our minds a break, and transport us through materiality, whether it be with metal, or with concrete, or framing the sky. Getting us to, instead of focusing on the ground, to look up.

Nancy Holt’s “Sun Tunnels” (1973–76) in Utah’s Great Basin Desert. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Sometimes you can get into your own head, and then get a little bit depressed. But when you look up at the sky, it’s like your whole being lightens. So many of [Noguchi’s] sculptures cause the viewer to look up. While he could be very introspective and, at some times, depressed, there was so much light in his work, which I think is really interesting in terms of causing the viewer to think more broadly.

SB: Right. Well, light and shadow, and the positive and negative space, is such a core component of not just Noguchi’s work, but a lot of this work that you’re talking about.

MP: Absolutely. I’ve always been fascinated by light and shadow. I’m not a photographer by any means, but I always have a sketchbook with me and a camera with me. I try to photograph geometry within nature and spend time in a specific environment that may inspire me to see how the light and the shadows move, and then those series of images often inspire the final work.

SB: Let’s talk about the materials you use. As I mentioned earlier, they range from fossilized dinosaur bone found in the Colorado Plateau, to pyritized dinosaur bone from the Volga river [in Russia] and the Caspian Sea, to fossilized walrus ivory, antique diamonds, black Guatemalan jade, meteorites…. I think I could go on. How do you choose the materials you use, and how do you work with these particular materials? What makes a material right for you?

“Sometimes I feel like I’ve broken into the back of the Metropolitan Museum [of Art], just in my studio.”

MP: There are so many things. It started with fossilized walrus tusks and transporting oneself back about 150,000 years in time, and then going further backwards to the fossilized dinosaur bone, and finding these materials that are so rare, that have stood the test of time. To be able to work with them is really a privilege and an honor. I mean, sometimes I feel like I’ve broken into the back of the Metropolitan Museum [of Art], just in my studio.

[Laughter]

Because of the rarity of these materials, which, in many ways, are much more rare than diamonds, I wanted to explore setting them and creating these sculptural forms around them, or, celebrating and highlighting the natural geometry that already existed within the piece.

For example, [one of] the pieces that I’m currently wearing is a vertebra of an ichthyosaur, which is from the Jurassic Period, and it’s perhaps one of the world’s first mirrors. Sulfur permeated the bone over 150 million years and made it reflective. You can see yourself within it. This piece did not need to be carved—nature carved it. That is also so interesting for me to explore: finding these sculptural elements within specimens, and not having to change them in any way.

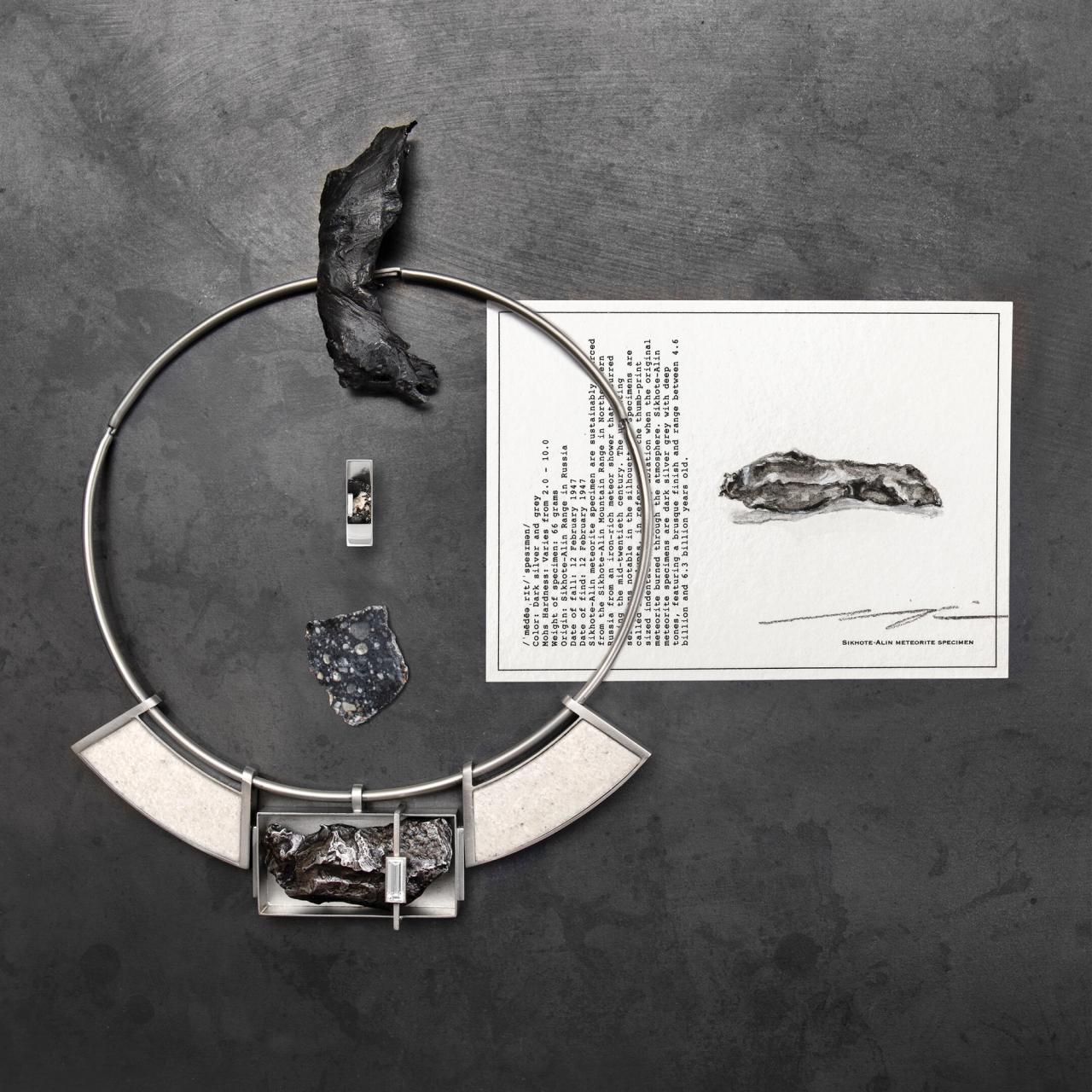

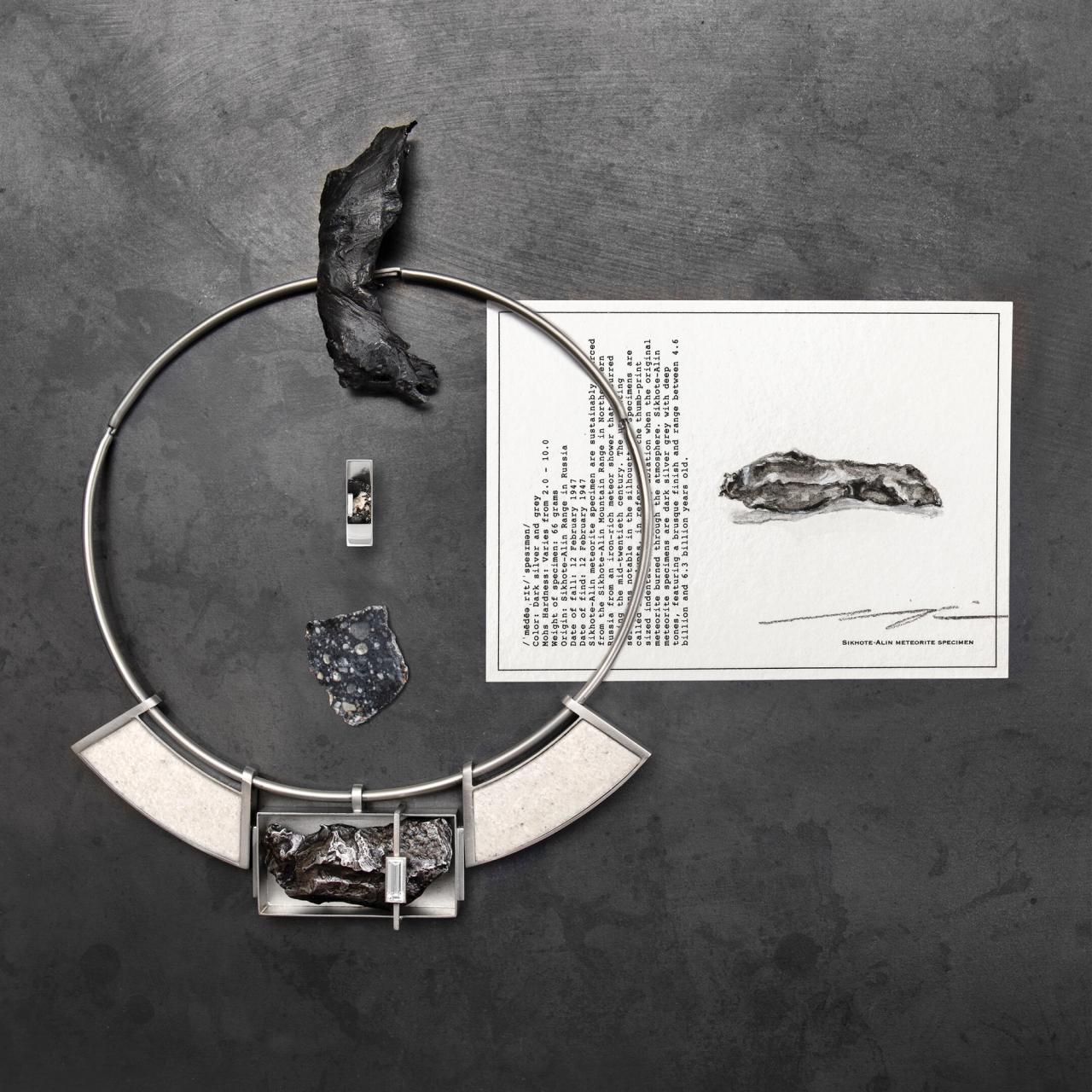

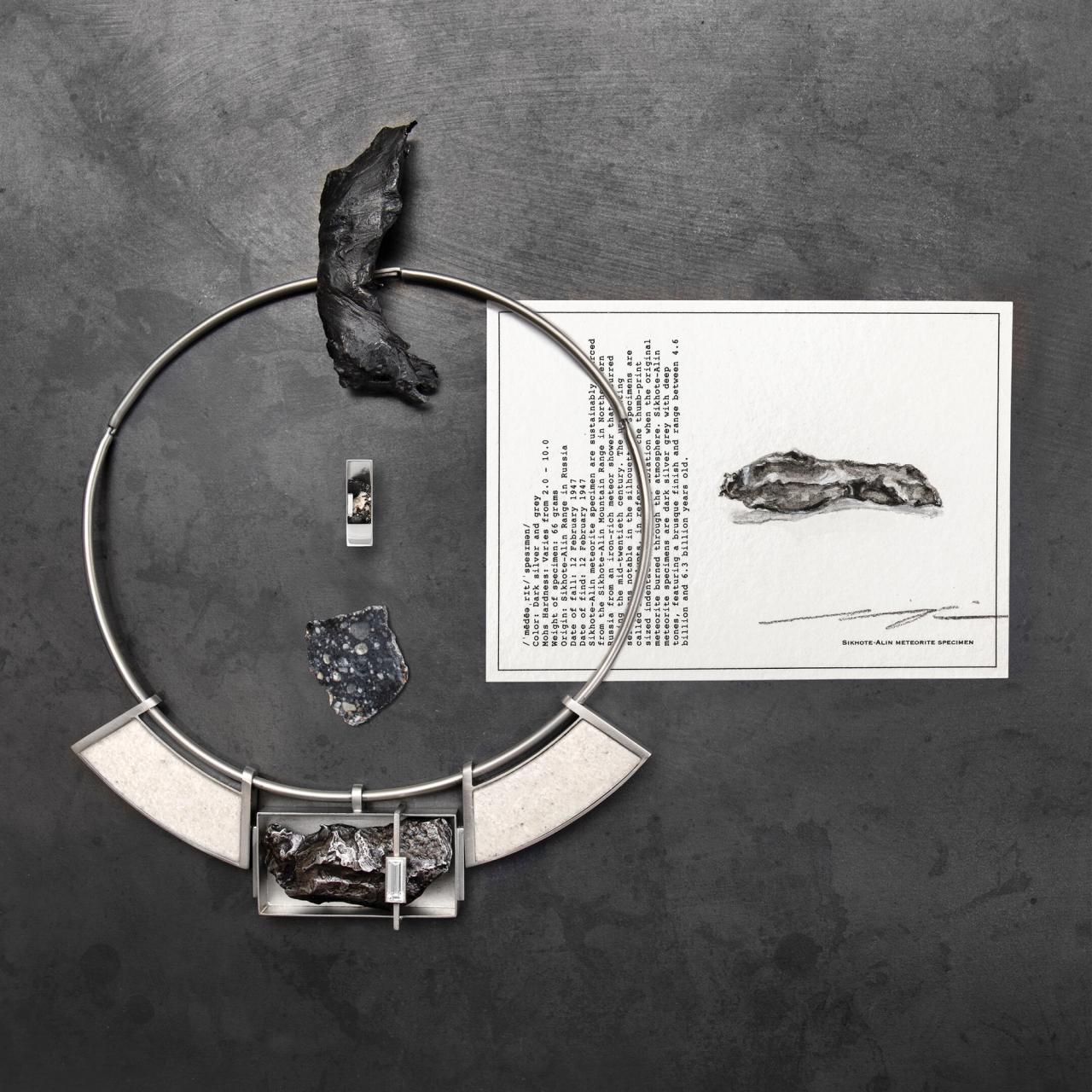

The meteorite and recycled platinum ring that Péan wore during her Time Sensitive interview. (Courtesy Monique Péan).

SB: When do you know that you have to add your hand, or the hand of a craftsperson?

MP: It’s funny. I think sometimes the specimens speak for themselves. You just know. It’s instinctual. This meteorite [points to the ring on her hand], it has the formation almost of a flower.

SB: The ring you’re wearing?

MP: Yes. This meteorite, I didn’t sculpt this. It was sculpted by its travel and its entrance into the earth’s atmosphere from outer space, from the heat and the pressure. This is older than the earth itself. It’s approximately five billion years old, so it’s a few hundred million years older than the earth. To think that it was formed by its traveling and somehow ended up in my hands—

Péan with fossilized dinosaur bones in Colorado. (Photo: Amanda Hearst)

SB: Well, that’s a good point. How do you get these materials? How do you find them?

MP: I’m constantly searching and traveling and looking for specimens that I can incorporate into my work. Over the years, I’ve built relationships with paleontologists, scientists, and geologists who know that I’ll appreciate these specimens more than most. Of course, sustainability is such a huge part of what I do. These specimens will, of course, be offered to the scientific and curatorial community prior to [being offered to] a private collection, or to be used as objects.

But many of them are just found. I mean, I’ve surveyed the land and trekked for miles throughout the Four Corners and Colorado, and you can find dinosaur bone [there]. You can pick it up on the ground. Parents take their children to Disneyland, and you can actually go to Colorado and find dinosaur bones on the ground. There are just these incredible miracles around us every day that we don’t even take the time to recognize and to see. And so, when you start to open your eyes a little bit more when you travel, and just day-to-day, you can see so much beauty in the world.

“There are just these incredible miracles around us every day that we don’t even take the time to recognize and to see.”

That’s what I try to do, is do research in terms of sustainable materials that are resting on the surface rather than [those that] require mining. Materials that require mining I’m not interested in, because the mining process is just so destructive. That’s kind of what led me on the path towards exploring fossils, because they are these found, forgotten objects that are right there in front of us, and you can spend time with the earth and immerse yourself in nature and find these treasures.

After the dinosaur bone and the fossilized walrus tusk, I thought, Now I’ve gone back hundreds of millions of years in time. What would it look like to go even further, and to contemplate space, and think about the formation of our universe and the solar system? That got me to working with meteorites and extraterrestrial material.

“I thought, Now I’ve gone back hundreds of millions of years in time. What would it look like to go even further, and to contemplate space, and think about the formation of our universe?”

SB: Which, how do you find that?

[Laughter]

MP: Actually, I started in the Arctic Circle in Alaska, but then ended up going to the Arctic Circle in Norway. Many of the meteorites that I work with are Scandinavian. Also, I work with Sikhote-Alin meteorites from Russia, as well as Campo del Cielo meteorites from the Southern Hemisphere and Argentina, and most of these pieces are found by nomadic individuals, by scientists, by geologists—but you’re just picking them up off of the ground.

You can find meteorites much more easily in icy terrain because it’s much more visible to spot when you see this dark, extraterrestrial steel gleaming against the snow. Having this relationship with scientists has been so fascinating, because while I think these materials are absolutely, breathtakingly beautiful, they’re so much more than that. Being able to understand a little bit about the science behind them, and what scientists are able to learn from these pieces that can help us to put together the building blocks of the formation of our Earth and help us understand more about how we can continue to exist on it, has just been incredible for me.

SB: In Norway, were you in Svalbard, by chance?

MP: Yes!

SB: I ask because—

MP: Have you been?

A meteorite acquired by Péan. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

SB: No. But Svalbard is fascinating from a time perspective, because it literally is out of time. They don’t have clocks there. They don’t follow—

MP: It’s very disorienting.

SB: They don’t follow time.

MP: It’s incredible.

SB: The only place on earth where there’s no—

MP: It is an incredible place to be. Yes, time is moving, and at the same time, standing still in Svalbard, especially because, for the majority of the year, it permanently feels like it’s around 11 a.m. because it’s so bright.

Traveling through Svalbard is one of the most incredible things that I’ve ever done. When I was there, I spent a few days trekking through the snow and looking for meteorites, but also just looking for inspiration, spending time amongst nature, and I came across a mother polar bear and two cubs, which was—

SB: I guess there are more bears than people there.

MP: [Laughs] But many people actually have lived in Svalbard for years and have never seen a polar bear.

SB: Oh, wow, okay.

MP: And now, with climate change, they obviously are facing so many challenges, so I felt very fortunate to be able to spend time with the polar bears. But also to be able to spend that much time alone, where, for days, I only saw one other person who was traveling by dogsled with a pack of Huskies. I’m thinking to myself, Where are you going? What are you doing? Hello!

Time, in ways, during these trips, can stand still, because everything around you sort of ceases to exist and doesn’t become important anymore, and you can really focus on the moment.

SB: I understand you’re now working with lunar material. How did you come across lunar material, and what are your hopes for what you might be able to do with it?

MP: I’ve actually been collecting lunar material for years. I’ll often have the opportunity to purchase a unique specimen, whether it be extraterrestrial or from the earth, and I don’t entirely know what it is, but I know that one day I’ll connect with a scientist who will appreciate that specimen. I have a few lunar specimens where I didn’t understand the rarity—lunaites are different from moon rocks in that we traveled to the moon and we picked up moon rocks and brought them back to Earth. That’s very different from a lunar meteorite making its way by happenstance onto the earth.

Péan sourcing sustainable spectrality in Norway. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

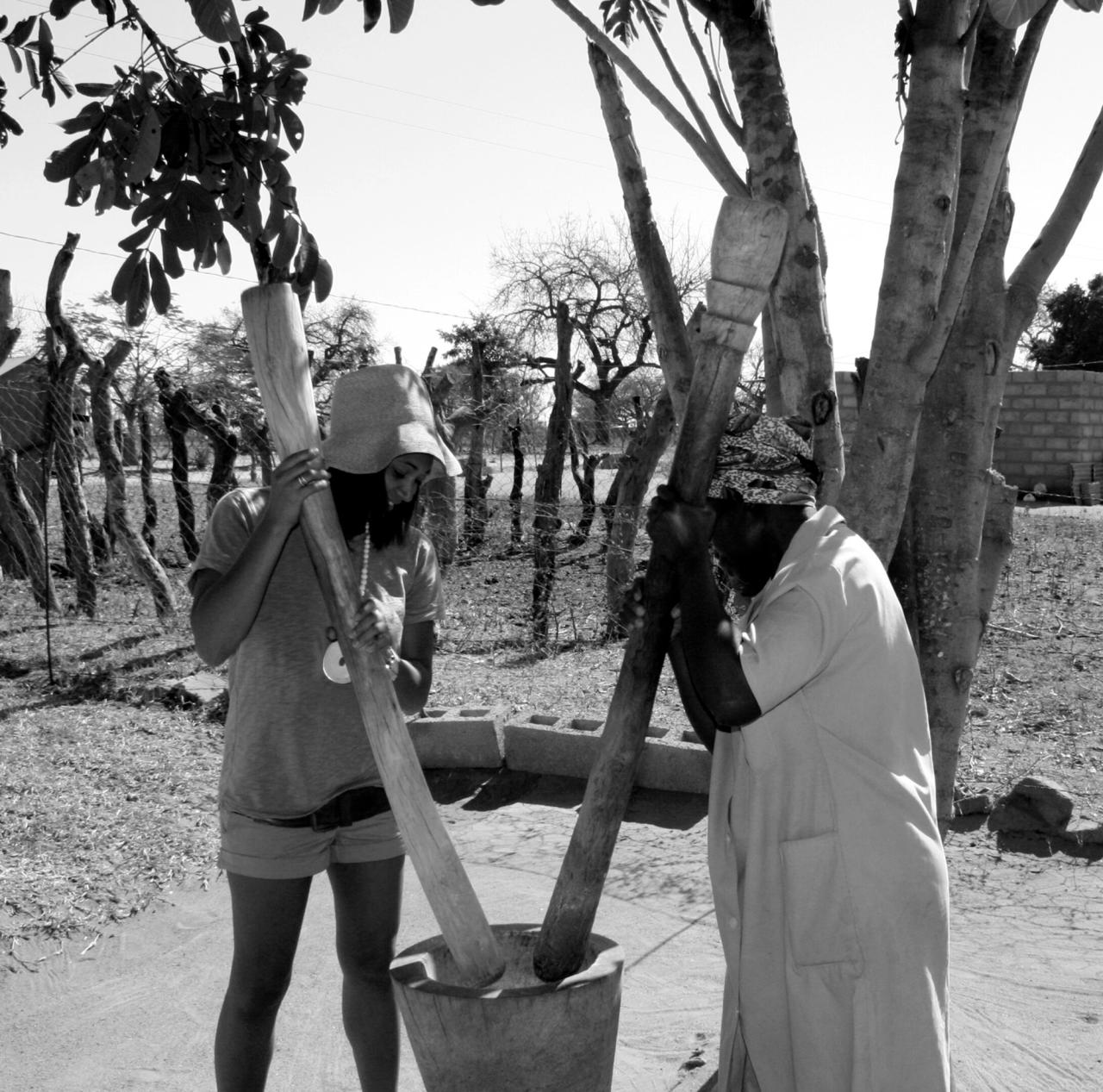

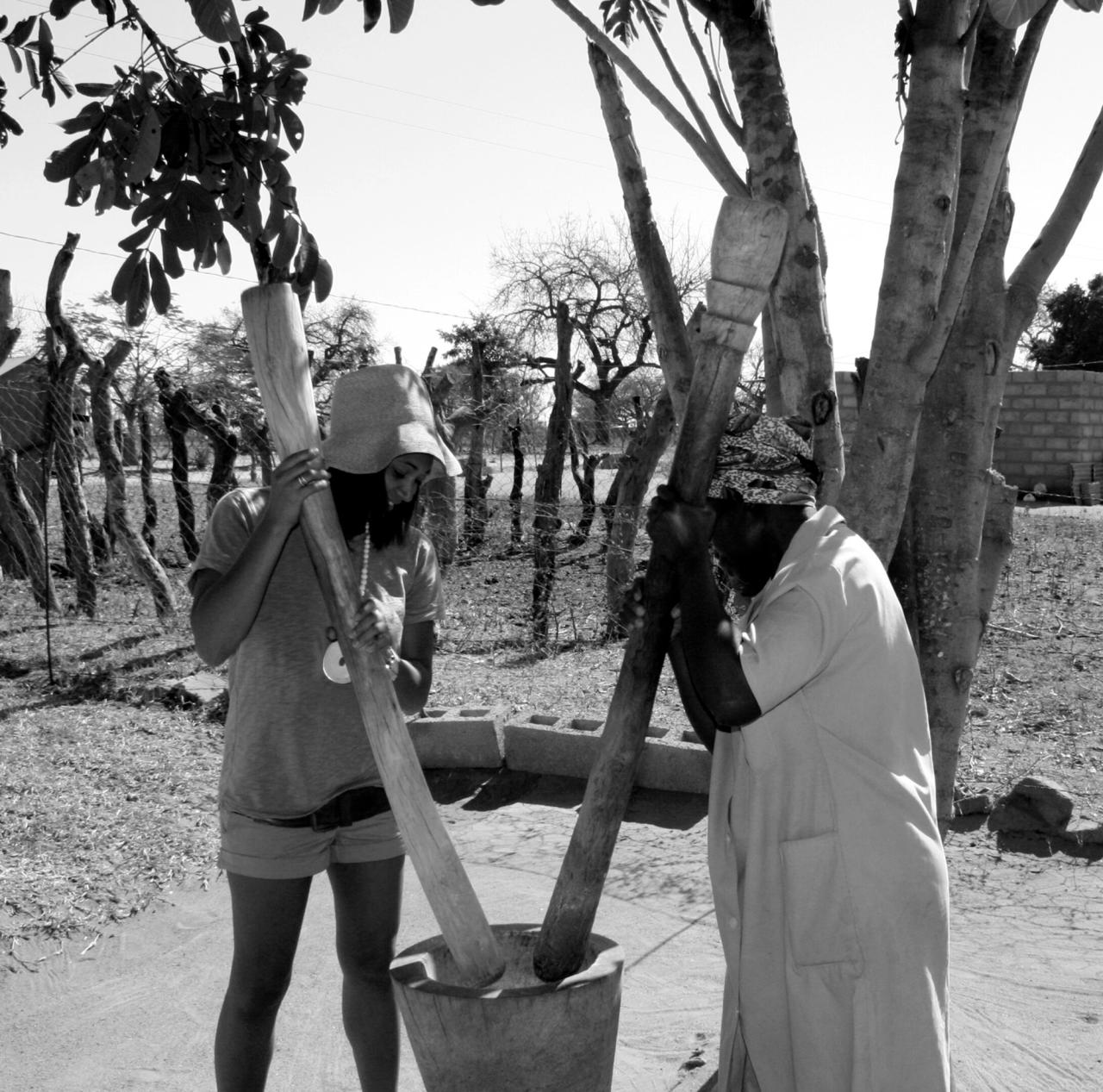

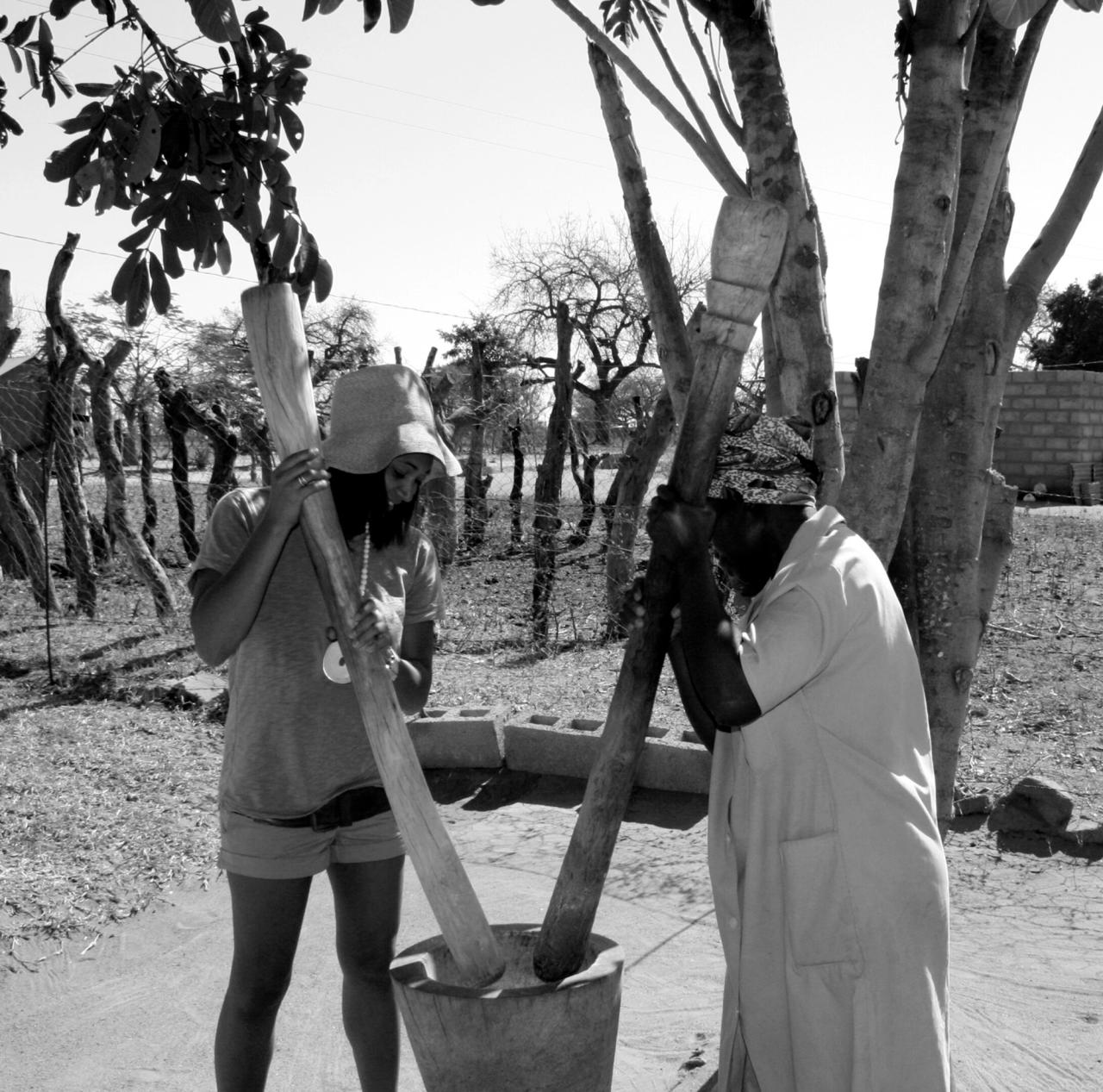

Péan in Mozambique. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Péan visiting Guatemala. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Péan sourcing sustainable spectrality in Norway. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Péan in Mozambique. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Péan visiting Guatemala. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Péan sourcing sustainable spectrality in Norway. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Péan in Mozambique. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

Péan visiting Guatemala. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

“To be able to hold a piece of the moon in one’s hand—it’s incredible. It really, in a way, makes time stand still.”

There’s less than 2,000 pounds worth of lunaites that have ever been found on Earth. So, an asteroid hit the moon, ejected a piece of moon, and the gravitational pull of the sun or the earth brought that lunar material into orbit, and then, eventually the earth’s gravitational pull brought it down onto Earth. Then, there had to be an incredible, by chance [occurrence, where] an individual happened to find this specimen.

To be able to hold a piece of the moon in one’s hand—

SB: Amazing.

MP: It’s incredible. It really, in a way, makes time stand still.

I’ve already started working with the lunar material in sculptural form, working on different sculptures, and working on wearable works as well. I’m right now working with scientists to learn more about the specific pieces that I have. What’s really interesting is that, if you lived on a different planet and you were to come to Earth, and you were to take soil from Nevada, versus Antarctica, versus Easter Island, versus French Polynesia, the soil is going to be so different.

The specimens that we have from when we landed on the moon are completely different from the different lunar material that I am working with. It’s really interesting to be able to converse with scientists and learn more about these materials and what they can tell us about our solar system and the universe.

“1130g Sikhote-Alin Iron Meteorite Vessel” (2020), part of the “Objects: USA 2020” exhibition. (Photo: Brittany Meyer)

SB: You’ve got a meteorite-and-bronze vessel [titled “1130g Sikhote-Alin Iron Meteorite Vessel” (2020)] that’s part of the “Objects: USA 2020” show [at New York’s R & Company gallery], curated by Glenn Adamson and Abby Bangser [as well as Evan Snyderman and James Zemaitis]. The vessel is encasing this rare meteorite that was found in 1947 and, as you have put it, “sculpted in outer space.” Could you talk about this piece, and how it connects to this idea that we were speaking of earlier, about the portal and about this notion of time travel?

MP: The show, with Covid, is now going to [open in February] 2021, but I’m very excited about it. [The vessel] is one of the first sculptures where I’ve tried to encapsulate time in a much larger form and a larger scale, to the weight of the meteorite. It’s rather significant. It’s really fascinating to be able to hold 4.6 billion years in your hand, and to have it impact you physically. When you hold it, it changes you. I want the viewer to be able to activate the work and to experience this extraterrestrial sculpture that I did not form, but can create a conversation around, and hopefully create an experience where one can be transported.

Péan’s charcoal sketch for the “Objects: USA 2020” vessel. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

SB: What you did create, though, that I think is interesting to point out, is a sort of alchemy between that form and material and this other material. So, could you talk about alchemy in your work, the notion of mixing these…?

MP: Sure. Working with metals and materials and bringing them together, and having that dialogue, I think, is really important. Just thinking about the [periodic] table of the elements, and thinking about bronze and how it’s made up of copper and tin, and then that relationship of bringing it together with this extraterrestrial steel…. The remnant bronze is also reflective, so it, in ways, is reflecting in the meteorite. Then, depending on the angle that you look at the work, the meteorite is continuing to travel through time.

Péan’s New York City studio. (Courtesy Monique Péan).

A fossilized walrus tusk bracelet from Péan’s first jewelry collection. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

A bench designed by Péan, seen in her studio. (Courtesy Monique Péan).

A meteorite necklace with a corresponding charcoal sketch, both by Péan. (Photo: Brittany Meyer)

Péan’s New York City studio. (Courtesy Monique Péan).

A fossilized walrus tusk bracelet from Péan’s first jewelry collection. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

A bench designed by Péan, seen in her studio. (Courtesy Monique Péan).

A meteorite necklace with a corresponding charcoal sketch, both by Péan. (Photo: Brittany Meyer)

Péan’s New York City studio. (Courtesy Monique Péan).

A fossilized walrus tusk bracelet from Péan’s first jewelry collection. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

A bench designed by Péan, seen in her studio. (Courtesy Monique Péan).

A meteorite necklace with a corresponding charcoal sketch, both by Péan. (Photo: Brittany Meyer)

“You can think of fossils as the world’s first photographs.”

I also think it’s really interesting to explore when these extraterrestrial materials impact the earth, and the formation that is created within the earth, that depression. In ways, you can think of fossils as the world’s first photographs, because there is that documentation of time. So I’ve carved out, within the remnant bronze, the sculptural imprint of the meteorite and really tried to explore documentation. I have also worked with charcoal to create a sketch of the meteorite itself and capture that beauty, and think about documentation the way that we, as people, document experiences, meaningful moments, [and] knowledge by writing things down or recording our ideas, and that this documentation is not only happening naturally through these materials landing on Earth, but that you can encapsulate it and bring those conversations together within the piece.

SB: I want to transition to a much shorter span of time: your life. You were born in Washington, D.C., to a Haitian-born father, who was a senior economist at the World Bank and then a consultant at the United Nations Development Program. Your mother is Jewish American, of Russian and Polish extraction, and, as you mentioned, a painter of impressionistic landscapes and portraits in oil. Could you talk about your parents, their influence on you, and what it was like being raised in Great Falls, Virginia?

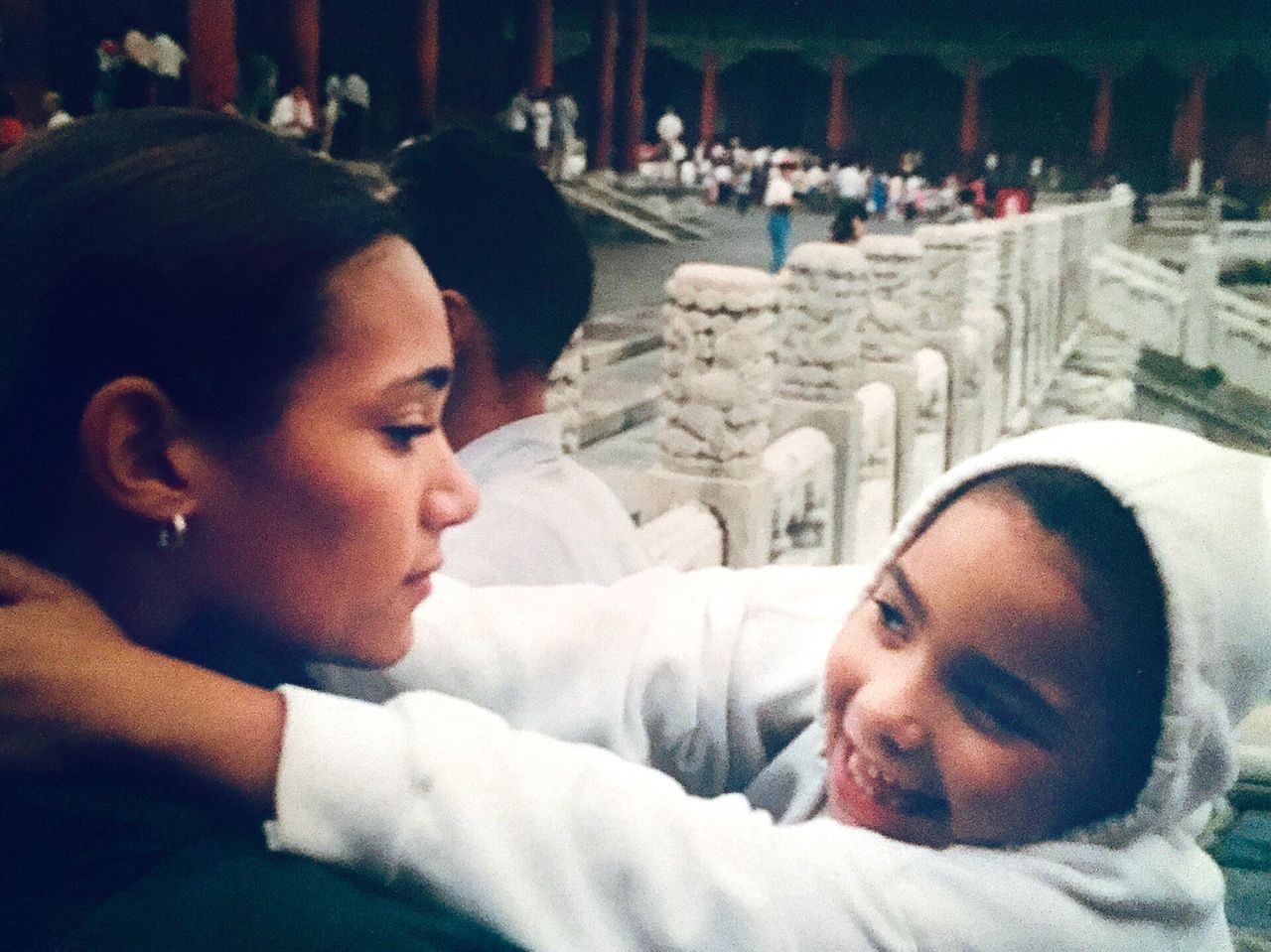

Péan as a child, with her mother (right). (Courtesy Monique Péan)

MP: During this very complex time that we’re currently living in, of civil unrest and environmental unrest, I think we’re all trying to unpack what’s going on around us and think about the difference that we can make, and take some time to think about where we stand in society. My parents, because they chose to be with one another, had to create their own little bubble to thrive. My mother, coming from a Jewish upbringing—my grandmother was raised in an orthodox home—was encouraged to marry somebody who was Jewish.

When she said, “I’ve met this man and he’s incredible, and he speaks thirteen languages, et cetera, et cetera,” my grandparents said, “Well, that’s great. Is he Jewish?” When she said, “Not exactly. I think maybe he’s technically agnostic, and happens to be Black.” That didn’t sit well with them. They disowned her and they canceled her—she was in college at the time, and they canceled her tuition. Her family stopped speaking to her, including her sister. My father experienced a similar situation where, because he chose to be with a white woman, he was ostracized as well. They decided they loved one another and they were just going to give it a chance. That meant that the world around them, their world—while it wasn’t accepting, they were going to create their own little world, and they had me.

When my parents were young, we lived in a studio, and my parents were on food stamps. Their love was everything. My father, coming from Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, with dirt floors and no electricity, was really focused on education. Education was your opportunity. Education was what would uplift you. People could take anything away from you, but they can’t take your education.

“When my parents were young, we lived in a studio, and my parents were on food stamps. Their love was everything.”

Growing up, my father really focused on education. He told me books were my friends, that I didn’t need to go and have sleepovers, and that, in life, I needed to constantly be striving to learn and for betterment. He chose to put me in an international school and made real sacrifices for me—and my sister—to be able to attend private school. He sent me also to Spanish school on Sundays. I was the only non-Hispanic kid there. I went to Korean math class every Tuesday and Thursday afternoon. Education was paramount in our family.

SB: And travel, right?

MP: And travel, absolutely, and travel.

SB: I understand you visited something like 20 countries as a child, including Egypt, Israel, Turkey, and Bulgaria.

MP: Absolutely, and it formed me and shaped me to really be a global citizen, which I think is very important and has played a huge part in who I am.

Going to an international school was an incredible experience because I learned to celebrate diversity from a very young age. But now, looking at where we are today, with all the civil unrest around us, I realize that I was so sheltered, because not everyone obviously celebrates diversity.

SB: What was it like for you growing up of Black and of Jewish descent? Did you feel ever like an outsider, or, in this school, did you kind of feel embraced?

“Because I grew up in an environment where the more different you were, the more celebrated you were, I developed a strong sense of self.”

MP: I don’t think that I really thought about racial inequities until I was in seventh grade, and I think because I grew up in an environment where the more different you were, the more celebrated you were, I developed a strong sense of self. But then, in seventh grade, I was exposed to a young girl who, unfortunately, was very racist and made a lot of racist comments. I had to think through how I felt about these really complex issues.

SB: Do you remember what she told you?

MP: Yes. Specifically, she said that she would never consider dating a certain boy because he was Black, because of the color of his skin, and I was horrified by that. I said, “How could you feel that way?” I think that when you’re that young—I don’t think that those were her ideas. I think that that was the family she grew up in, an environment where racism was around her, and these ideas were shared [with her].

I told her that I didn’t agree with her ideas, and I thought that they were racist, and that I didn’t want to be friends with somebody who was racist. That created quite a conflict, because I no longer wanted to be friends with somebody who had been part of my friend group, and then it created factions within the school.

It was pretty crazy because they brought my parents into the school, and they said, “Monique has to be friends with this little girl. Because if she’s not going to be friends with her, she’s now convinced so many other people not to be friends with her.”

SB: Which is basically like saying, “It’s okay to be racist.”

MP: Completely. My parents obviously refused to tell me that I had to do so. I ultimately chose to leave the school. I was twelve or thirteen years old when this happened, and it really opened my eyes up to the inequities and the systemic inequalities and racism that exists in our society—even in that little international bubble that I was in.

In ways, I’m so thankful that I was shielded as long as I was. But at the same time, I think that perhaps my parents should have taught me about the world around me, in terms of all the injustices that exist. Right now, reading through Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Anti-Racist, and his version of the book for children…. I’m taking the time to read this to my three-year-old and my five-year-old, and to try and unpack these ideas. And I do wonder, Is this the right thing to do? Do you bring up these social constructs that we’ve created with children who are so young? Perhaps you do, because not everybody has the ability to ignore them. They’re very complex topics, to say the least.

SB: You went on to earn your bachelor of arts in philosophy, political science, and economics from the University of Pennsylvania. What stands out to you from that time? Did you have mentors there? Were there particular classes or areas of study that perhaps led you on your circuitous path into finance, and then eventually, into jewelry and playing with rocks, basically?

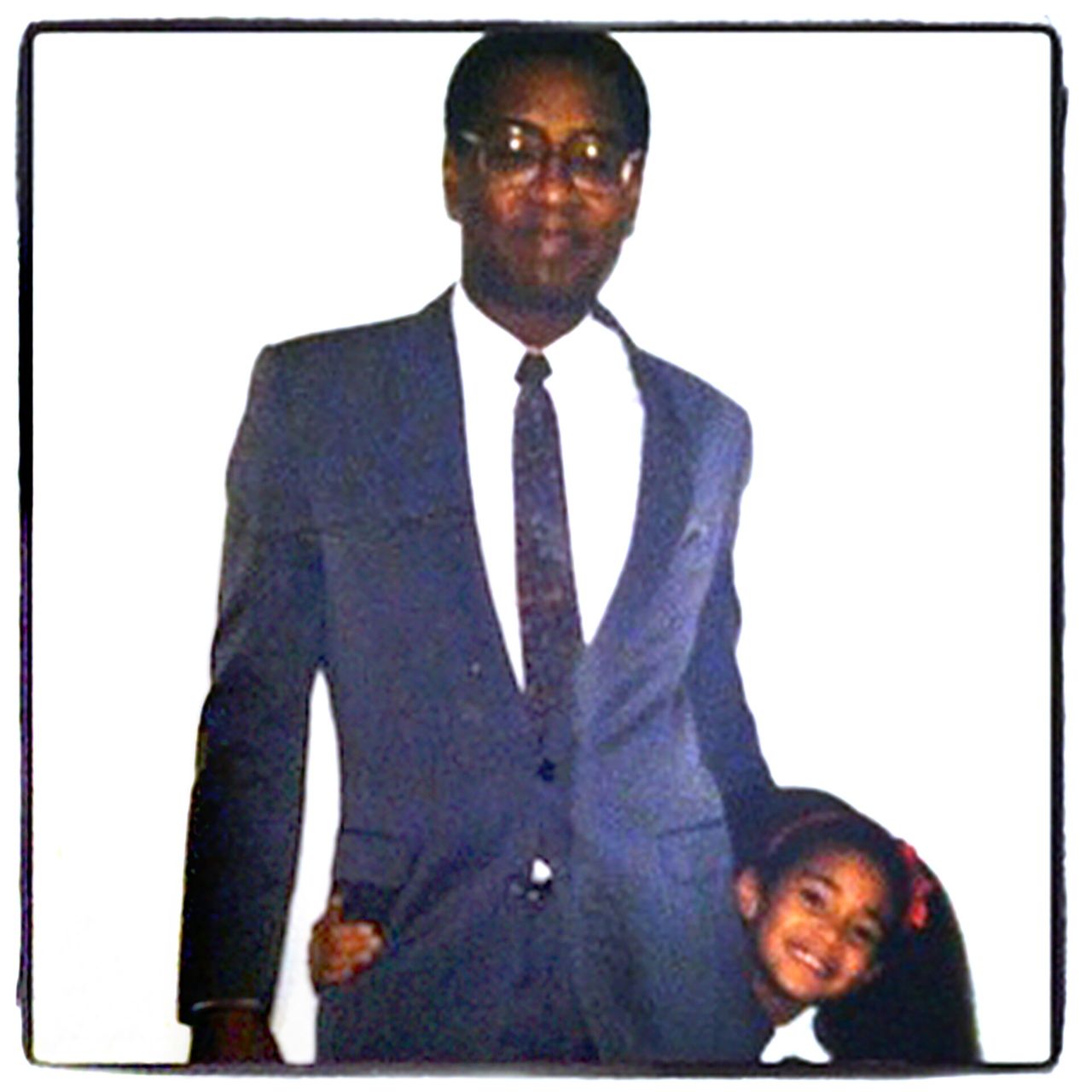

Péan as a child, with her father. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

MP: My father focused on education, and coming from next to nothing, told me, “In life, one can be one of three things when they grow up: a doctor, a lawyer, or a banker.” I immediately said, “What about an artist? I think that’s what I want to be.” He said, “Let me repeat that for you: doctor, lawyer, or banker.”

So I didn’t really have much of a choice. I was basically told I had to major in economics. Then I started thinking, Okay, well, if I’m going to major in economics, what are the other things that I can learn and focus on? And so, philosophy, political science, and economics as a major, as a concentration, was very exciting for me.

Looking back on my time at university, I think the most memorable and impactful [moments] were really the philosophy courses that I took. I think about John Rawls and his veil of ignorance all the time. Every morning, when I read the news and think, Oh my God, how am I going to get up today?, I think about the veil of ignorance and the concept that if we made decisions, and if we made our laws so that they would benefit the greater good of society, we would be in such a better place. If you had this veil over you where you didn’t know what your stature would be in society, or what opportunities you’d have, whether you’d be rich or poor, whether you’d have challenges with your health—you’d make decisions that would help everyone. I think that we really need to take the time to think about how we can do better.

“We really need to take the time to think about how we can do better.”

SB: Yeah, and the humanities, the liberal arts, is a huge part of navigating that. You, after college, worked as an analyst on the fixed-income desk at Goldman Sachs. [Laughs] Sorry to laugh—I don’t mean to laugh.

MP: [Laughs] Yeah, it was a crazy time.

SB: Yeah, and in 2005, this incredible tragedy happened that you mentioned earlier, where you lost your sister, Vanessa, who, at the time, was a high school student. What was it like for you to find out about that? What was your immediate response to what had happened?

Péan (left) with her late sister, Vanessa. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

MP: Time stands still. You freeze, and the air becomes extremely thick. My mother knew that something had gone very wrong. My father was traveling for a development project at the time, and my mother said, “Vanessa should have been home fifteen minutes ago.” And I said, “Okay, but I’m sure she’s just running a few minutes late.”

SB: Wow. It was that fast. Wow.

MP: She knew instantly. She just knew. In her body, she knew. I don’t know if there was energy that was sent. I mean, my mother was able to drive to the site of the accident—or not able to, she did. She drove to the site of the accident and came upon my sister within twenty minutes of her passing. I was supposed to have gone to a party that night; everyone was celebrating Halloween. For whatever reason, I decided that I didn’t want to drink at all that night, that I didn’t really want to be at this party, and instead decided just to have a much more low-key evening. Being in my twenties, that was, in New York City, not the normal Saturday night decision.

My mother called me—and I normally also wouldn’t pick up the phone around 11 p.m. on a Saturday night—and she said, “I’m concerned about your sister. She should have been home about fifteen minutes ago.” I said, “I’m sure it’ll be fine. She’ll be home in a few minutes.” She said, “No, I just know that something’s wrong.” She said, “I want to go out and search for her.” I said, “Mom, I think that you’re overreacting. I think she’s going to come home, and then she’s going to find that you’re not there and she’s going to be extremely worried.”

I argued with her for a little bit, and then she said, “I’m going to make her favorite cookies, and then when they’re done, if she’s not home, I’m going out to look for her.” Living in Northern Virginia, right on the border of Washington, D.C., and Maryland, I said, “She could be in Washington, D.C. She could be in Maryland. Where are you even going to go?” I thought that this just seemed like an insane concept, for her to go out and search for my sister.

Then, a few minutes later, the cookies were done, and she said, “I’m getting in the car. I’m going to go try and find her.” Within a minute and a half of driving, she came upon the accident. I was on the phone with her. It, in ways, is crazy, because we’re coming up on fifteen years [since] her passing, and it seems, in ways, that it was yesterday. But then, as we get closer to enough time going by that it will have surpassed the age that she was…. When we get to sixteen years, that’s going to be very challenging. So thinking about time, and how, in ways, it can be frozen, but then—

SB: And then seeing your own children when they reach that age.

MP: Completely.

SB: What was your process for healing and grieving in the aftermath? You launched your jewelry line in 2006, just a year later. How do you see the work you’re doing in the context of this, coming out of the ashes of this event?

“You can either choose to be engrossed in despair, or you can channel that energy and create something positive, and I think that the latter is really the only way to live life.”

MP: Grief is so complex, as you know. Unfortunately, our club is much too large. But I think you kind of really only have two choices: You can either choose to be engrossed in despair, or you can channel that energy and create something positive, and I think that the latter is really the only way to live life. I think when someone loses a loved one, they just know in their heart that that loved one would want nothing more for them [than] to live their life to the fullest. To maximize the time that they have, and to contribute.

I knew that that’s what my sister would have wanted. I also think about what it means to lead a successful life all the time: Am I doing things the right way? Should I be doing more? Am I raising my children in the right way? Is this the right location to be raising them during these challenging times to be living in America, in New York City?

“A successful life is not about how long one has lived.”

I think a successful life is not about how long one has lived. It’s about, did they live life to the fullest day-to-day, and did they make real contributions while they were here, so that when they leave, have they left this world a little bit of a better place?

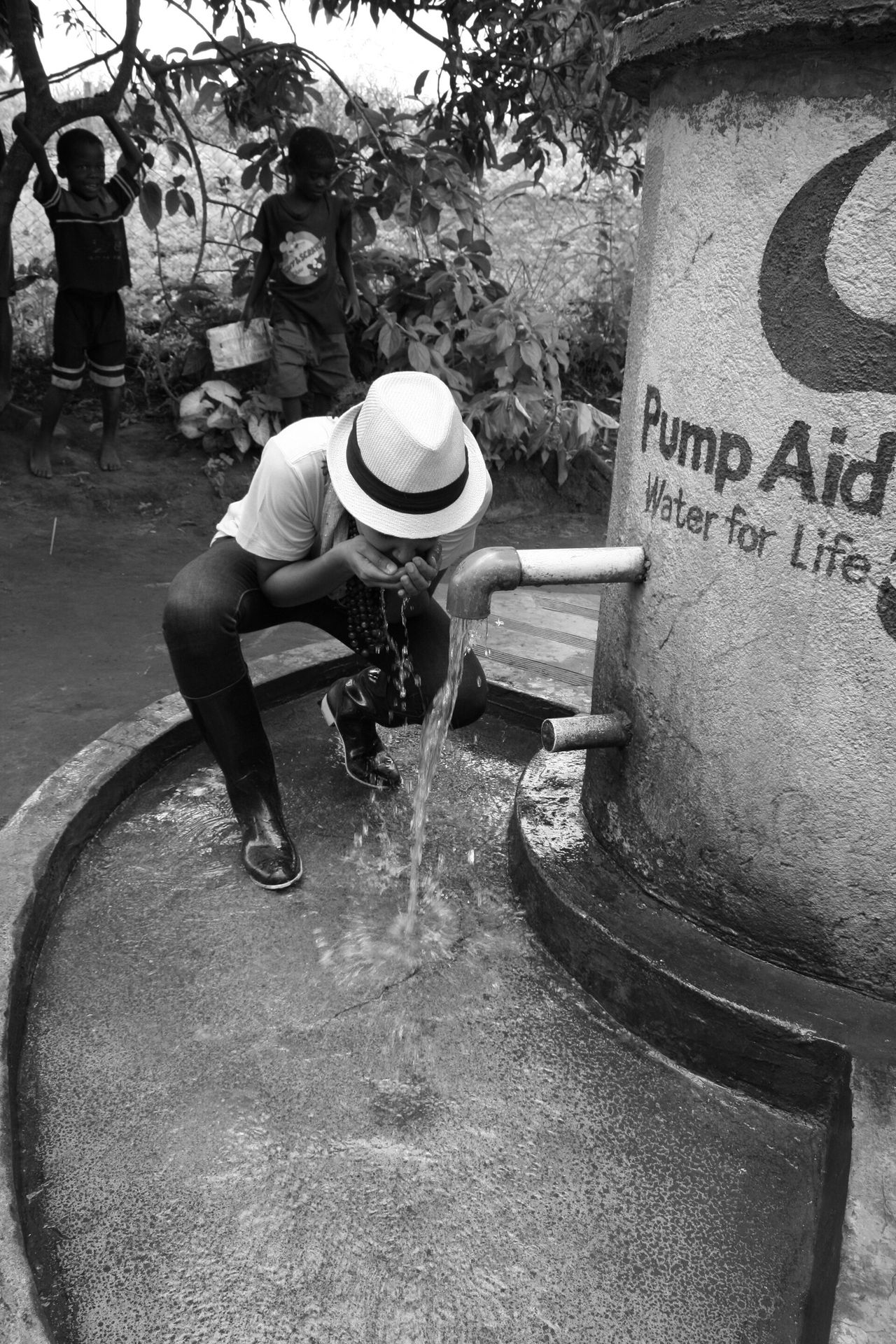

Péan in Malawi, drinking from a clean water well created by Charity: Water. (Courtesy Monique Péan)

In just sixteen years, my sister was able to do that, And that has been such a life lesson for me. You don’t need an extensive amount of time to be impactful. At the age of 16, she recognized the power of philanthropy, and had been to Haiti with my father for a development project. She said, “I think I could help to raise [money for] scholarships,” and raised tens of thousands of dollars to be able to provide scholarships to young students in Haiti.

I realized that at that time, at the age of 25, I was moving bonds around a marketplace, and I wasn’t making the world any bit of a better place. So I needed to stop and think about what I wanted to do with the rest of my life, and how I could be impactful. Some of it has definitely been selfish. I love to travel. I’ve found a way to have a career that [allows me to] pursue my passions and learn about art and culture, and nature and the environment, and bring all those together to create work in a responsible way that can give back. I have my sister to thank for that.

SB: In a way, do you see your work as a tribute to her?

MP: Ten thousand percent. With each piece that I sell, I work to provide clean water to communities in need [by donating a percentage of the proceeds to the nonprofit Charity: Water]. There are so many water-stressed places in the world, and lack of access to clean water is the leading cause of death for most children under the age of 5, and one out of every ten people in the world lacks access to clean water.

So when I’m able to build a new clean water well that I know is going to last for an average of twenty years and is going to give young children, girls, and women time to be able to develop their minds and to develop community, and go to school, and hopefully start a business, and develop the land, I think that it’s a tribute to my sister.

“I definitely believe that matter can neither be created nor destroyed.”

I definitely believe that matter can neither be created nor destroyed, and that she is somewhere smiling down on me and watching over us.

SB: Monique, thank you so much for coming in today. It was so great to talk with you.

MP: Thank you so much for having me.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on September 24, 2020. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity by our executive editor, Tiffany Jow. This episode was produced by our managing director, Mike Lala, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.