Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Min Jin Lee.

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Min. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

MIN JIN LEE: Hey, Spencer. What’s up?

SB: I thought we’d start today just with right now. I understand you’ll be speaking with Viet Thanh Nguyen this evening—

MJL: Yeah, in a couple of hours.

SB: … at the 92nd Street Y.

MJL: Yup.

SB: How are you feeling about that conversation, and also just this current moment in time?

MJL: I’m really sad and angry and confused. I did an event on Wednesday, and I think that, if I could, I would not be on stage this week, because I think that New Yorkers feel really hurt in a very specific kind of way. There isn’t a person in New York who hasn’t been touched by what happened on October 7th. Our hearts just can’t comprehend the level of cruelty of the whole situation, and there’s so little time for nuance. There’s so much misinformation on the internet, so there’s a part of me that just feels really heartbroken.

Of course, also, I study war and genocide and displacement. [Laughs] I’m considered very often a diasporic writer, but I take a really long time to write about something, so I’m processing, and I’m listening, and—it’s very hard. It’s a very, very, very hard topic, so I don’t know what to do. I’ve been crying a lot. I did an event on Wednesday, and, to open it—because I wanted to address the situation—I did something really strange. I don’t know what made me do it, and I’ve never done this before.

Cover of The Best American Short Stories 2023. (Courtesy Mariner Books)

I actually gave a benediction that I have when I go to church, at the very end: “May the Lord face … put His face…. May the Lord shine His face….” I can’t even do it. I’m gonna get really upset, so I’m not going to do it now. And I just started to cry. Because I want the blessing. I want people to feel a blessing. [Tears up] Oh, Spencer, why did you do that?

[Laughter]

SB: I actually thought that was a softball question. [Laughs]

MJL: Oh, no. I don’t know how to do that. I don’t know how to do this chitchat.

SB: Well, I also thought—

MJL: You could cut that out if you want.

SB: No, I think it’s important to keep. But another place I wanted to begin was you’re known for these two gorgeous, sweeping novels, Free Food for Millionaires and Pachinko. But before we talk about novel-writing, I wanted to start on the subject of the short story.

You’re the editor of this year’s [The] Best American Short Stories [2023] anthology, which just came out. I was hoping maybe you’d speak a little bit about your time working on that project, how you selected the works, and what it’s taught you maybe more deeply about the art and craft of the short story, having to go through so many, select them, and put this collection together.

MJL: That’s why I was on stage on Wednesday, and I think that if I hadn’t been so committed to supporting beginning writers, especially, I don’t know if I would’ve been able to get up on stage on Wednesday. But I do think that fiction writers really need advocates. If you are a literary citizen, part of your job, I think, is to hold up other people’s work and to uplift, especially the next generation. I think that publishing has changed so much. It’s really, really hard to sell books—to share ideas—because I don’t think most writers are in it for the money. [Laughs] I mean, most writers have enough education that they can pretty much do anything.

“If you are a literary citizen, part of your job is to hold up other people’s work and to uplift, especially the next generation.”

When you decide to write, you’re making a conscious decision of obscurity, poverty, and, in many ways, being ridiculed. And to write short stories, I mean…. The world doesn’t really respect it. Maybe the world is wrong. I think the world is wrong. So that whole process, when I decided to undertake it, there are two things I was thinking about. I was thinking about, in the history of Best American Short Stories—the most important anthology in the world dedicated, in English, to short stories—there’ve only been three Asian Americans who’ve been asked to be the series editor, and it was Amy Tan and Salman Rushdie.

And then I got to do it, and I thought, Oh, that felt meaningful to me. Kind of like, Oh, I should do this, and I should take it seriously, and if I do a good job, maybe they’ll have other Asian Americans do it. That’s sort of the way I think. There are many people who don’t feel this way, but I definitely feel a sense of: I owe people, sort of, my work. And then the other thing that I thought about was: [Sighs] How do I change things? How do I get people to read fiction? Because it’s so good [laughs], and it can bring your brain back, and we can—

SB: And our stupefied Instagram, Netflix state.

MJL: Yeah, which is causing, probably, some of the greatest mental health crises right now [that] we’re seeing. I teach college. I see it in my students. I see how distracted and how our brains have been rewired so irresponsibly by so many smart people who have worked for these tech platforms—which I participate in. And yet, I also think it’s created so much polarization in terms of discussion—how we don’t listen. And I do think that fiction can heal the brain.

Canadian short story writer Alice Munro. (Photo: Derek Shapton)

SB: Mm. I was hoping maybe you’d speak a little bit about your own relationship to short stories as a reader and writer of fiction, and how certain stories of yours—“Bread and Butter,” “Motherland,” “The Best Girls,” to name a few—have shaped you and really helped propel your path forward as a writer toward becoming a novelist.

MJL: That’s so kind of you to even know those. I haven’t written that many short stories. They’re really hard to write. When people write them I kind of think, “Oh, you also polish diamonds for a living?”

Whenever I meet somebody who’s really good at it, I just kind of think, “Oh wow.” Like William Trevor, Alice Munro—the greats, you know, when you think about the greats. I’m sort of astonished by it. I started writing short stories because when you take classes—and I took a lot of cheapo classes in New York—it’s really the only way you can learn how to write fiction, even just page by page.

Irish novelist, playwright, and short story writer William Trevor. (Photo: Jerry Bauer)

And then, of course, making a short story work, it’s like magic, because you can tell immediately when it doesn’t work. But I do like the discipline of it. Every story I’ve ever written, I’ve published. However, they took so much time. I couldn’t get over how long things took. And I think the one that I ended up making into Pachinko—I can’t even remember when I published it. It was like fifteen, sixteen years ago? And that story [took], I don’t know, maybe fourteen, fifteen drafts.

SB: That was “Motherland”?

MJL: Yeah, that was “Motherland.” But I think that I’m not normal. There are a lot of people who are very easy to let things go. I am not that author.

SB: I mean, “The Best Girls” you wrote from 1989 to 2019. [Laughs]

MJL: Yeah, yeah.

SB: That is a level of—

[Laughter]

MJL: Record. Yeah, I could win a record on that. Kind of like, “The biggest idiot writer of the year would be Min Jin Lee, because she took so damn long.”

“I’m a very sober person, and I’m okay with that. It’s kept me out of trouble.”

SB: Talk to me about the sort of endurance or the commitment of that. What compels-slash-propels you to do that for so long, writing and rewriting? And when, with that story, did you know you were finished?

MJL: I think the last publication that I have in it now, which is available on the Amazon Kindle Original Stories series, I’m very happy with that draft, so I’m done. But it took decades, because I did write it in college. I wrote it in college for a class, and it won a minor flex that nobody cares about. [Laughter] I wrote it in college, and I won the Best Fiction for that year for all the undergraduates. And as a non–English major, I was so shocked, because I didn’t know that I won that thing. But I remember thinking, Oh.

Lee during her time at Yale. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

And I didn’t do very well in that class. I got, I think, a B-plus, which I think that other people may not respect. It’s fine. It’s a perfectly fine grade. But it wasn’t like the professor was thinking, Oh, this is the best student in the class. But I had submitted that story on blind submission to the English department at Yale, and they had decided that it was the best work of fiction for all the undergraduates. So clearly, that just tells you why prizes… mean nothing [laughs]—that you don’t really know what people like. And then having written that and then having published it recently, it really goes to show you that when a writer has something to say, they’re still thinking about it. I’m still thinking about a lot of things, and I hesitate to say something quickly. I’m a very sober person, and I’m okay with that. It’s kept me out of trouble.

SB: In the introduction to the book, you note that, “In the book world and in art circles, it is considered impolite to discuss money and time.” I understand the money part, but I wanted to hear you talk about the time part here. Why do you think it’s impolite to talk about time in those circles?

MJL: Well, because it sounds like it’s judgment. It sounds like, “Oh, there’s only one way to do something.” I recently heard Stephen King, maybe two years ago, say something about Donna Tartt and about her production schedule, and he was very complimentary. And I don’t know Stephen King, and I don’t know Donna Tartt. But I felt a little pang of, “You write your way, and Donna Tartt writes her way. And both of you have audiences.” There’s enough space to have different kinds of audiences.

The tail of a book is so long, if you’re fortunate. So there are people who say to me, “Oh, I just read Free Food for Millionaires,” and I think, Thank you. One, thank you. It’s a long book. And then two, it was published in 2007. And people are saying, “Oh, it really changed X, Y, Z for me.” And I think, Oh, that’s the tail of a book. So I always find the whole—what do you call that—marketing schedule of a book to be kind of funny, because if you’re lucky, you get a week. [Laughs]

SB: It’s a hype cycle.

MJL: Right.

SB: It’s not the long duration of the book’s life.

MJL: And it certainly didn’t take a week to write a book. No one can write a book in a week. Not even Stephen King. [Laughs]

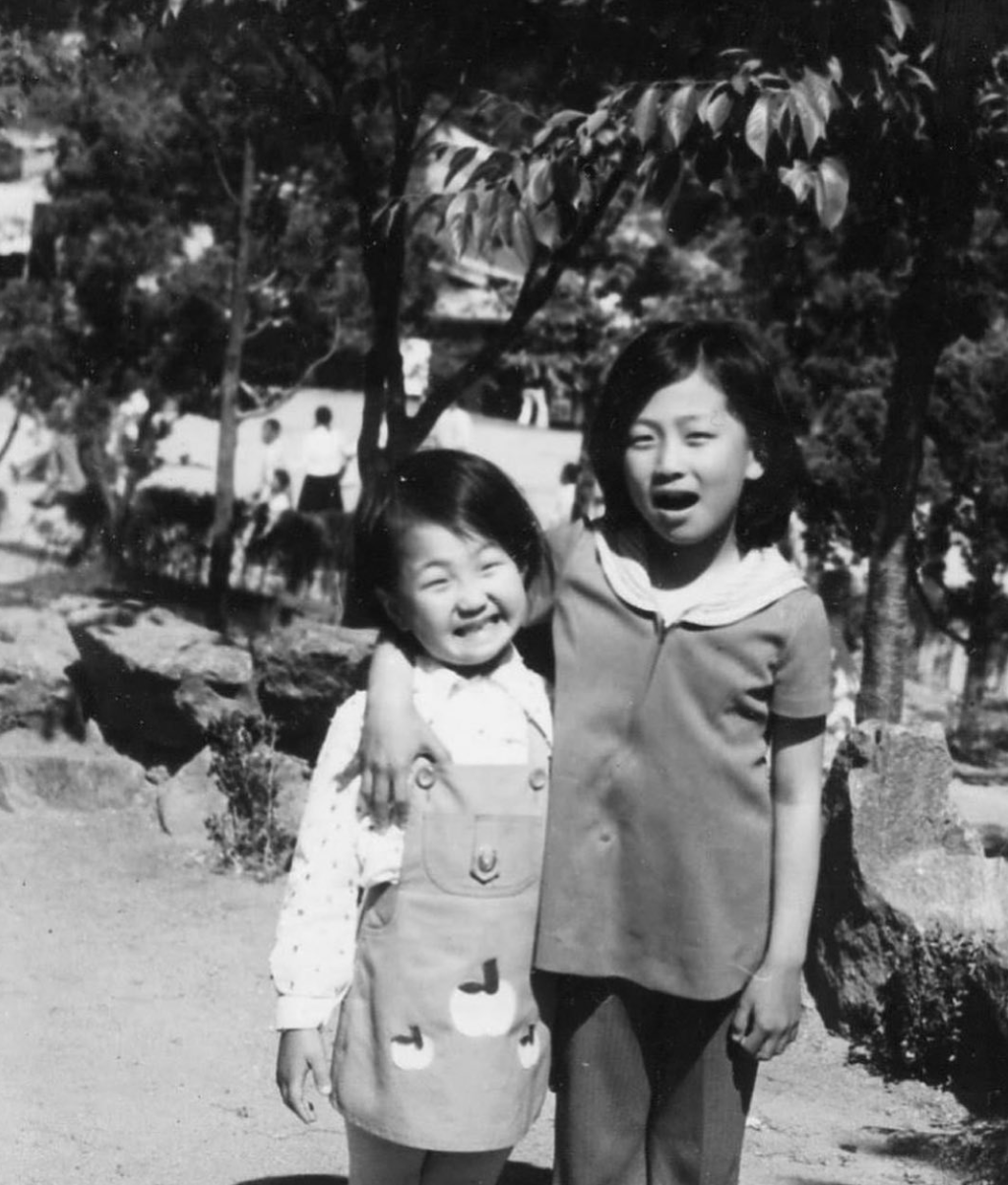

Lee (left) as a child in Seoul. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

SB: Both of your novels took an extraordinary amount of time to write.

MJL: Yes.

SB: If I have it correct, Free Food for Millionaires was around five years to write from when you first started, but by the time it was published, it was actually twelve years since you had quit your job as a corporate lawyer.

MJL: Yep.

SB: And Pachinko technically took thirty years.

MJL: Yeah, it did.

SB: Could you talk about your relationship to time as a writer? How do you think about it in this process, and do you just lose track of it? Because it seems like these are such long-view projects where you’re like, “Oh, well, I might finish in five years. I might finish in ten. I don’t know.”

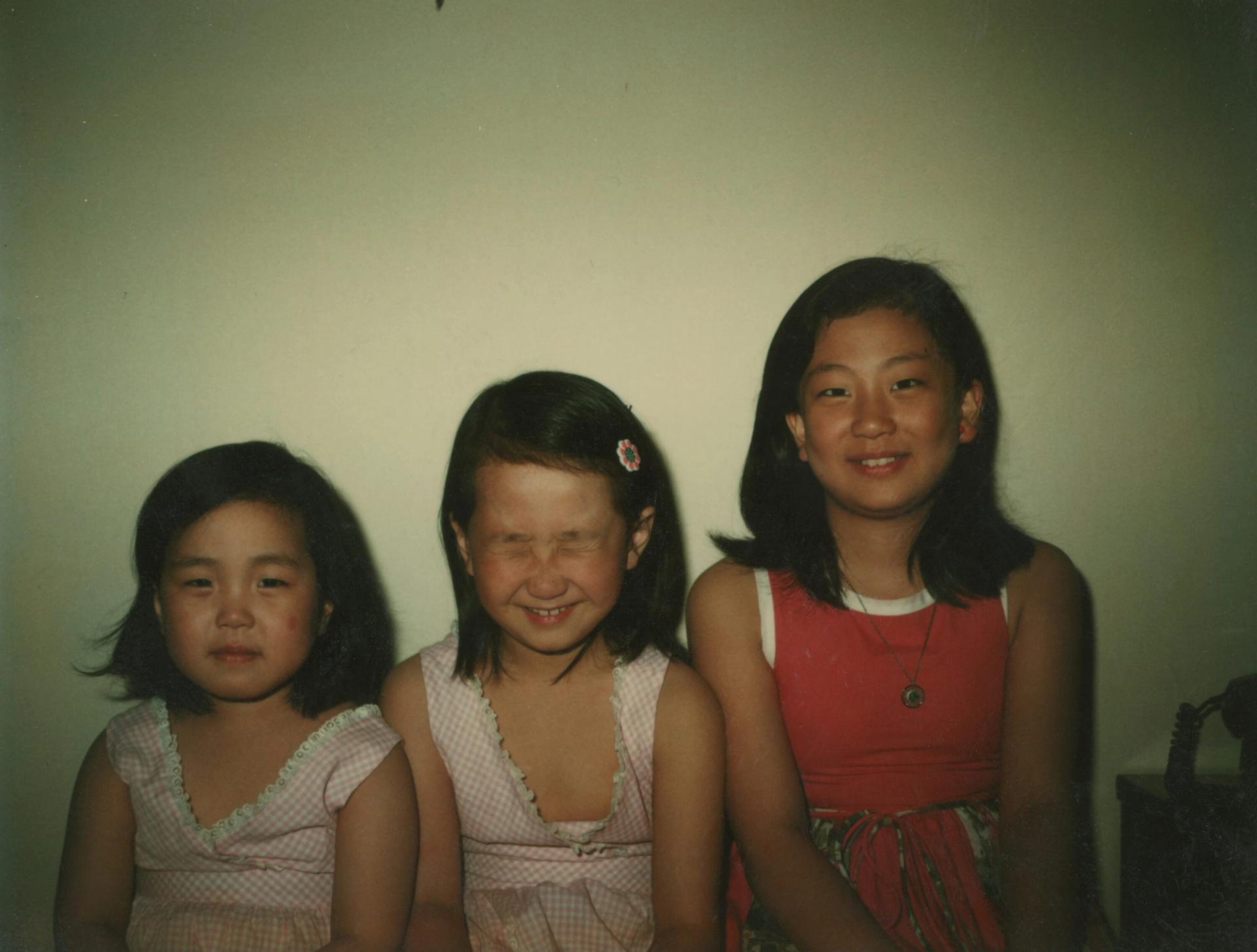

MJL: Well, I had this real freedom of having given up so many things. I also have a fairly low overhead, and it’s a decision that I’ve made. In my family, there are three girls. I’m the middle one, and both my sisters are really fast and smart, and I was always considered the slow one. So my father actually calls me Turtle. There’s two nicknames that I have. One is Turtle, and the other one’s Popeye. I can’t get into it now. [Laughter]

Lee (center) with sisters Sang (left) and Myung (right) circa 1976. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

“If someone ever has an argument with me, I will go to the mat, and I will fight for my work.”

I do feel like I’m this very slow and steady person. I always finish. As long as I have breath in my body, I feel like I’m going to finish my books. I keep my promises. I’m usually early for appointments. I pick up on the first ring. So it isn’t as if I take everybody else’s time without conviction and seriousness. But when it comes to creating something that I put my name on, I want to be proud of it. I’m very proud of my work. I stand by my work. If someone ever has an argument with me, I will go to the mat, and I will fight for my work. So it isn’t that I’m shy about the quality of my work, but by the time you get it, I have really thought about it. [Laughs]

SB: Yeah, I mean, research is so central to your process. You basically research like a journalist and conduct—

MJL: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

SB: … anthropological-, sociological-, journalistic-level research work. I mean, for Free Food for Millionaires, you interviewed these people who went to Harvard Business School, and then—

MJL: I went to Harvard Business School.

SB: Yeah, and then, even went to Harvard Business School, sat in on a class. I also read that you took a semester of millinery at FIT. And for Pachinko, you read all of these sources about the Korean Japanese. Talk to me about this research process. I think for the non-novelists listening, they should know this is not an ordinary process, I would say, to go into writing a novel.

MJL: No, it’s probably not advisable. I don’t tell my students to do this. I don’t. I think you have to be a certain kind of stupid or crazy, but I can’t really imagine working in any other way. I like the way I work. Also, it engages me emotionally and intellectually. It also makes me feel really confident about what I talk about. Very often people ask me, “Why is it that you’re talking about X, Y, Z?” And I think, “Well, I know a lot about retail and fashion now because I wrote Free Food for Millionaires. I understand a lot about craftsmanship. I also know so much about Wall Street.

“I know what it’s like to be questioned for being in the room. I think that I feel very confident about walking into any room now. You can send me to Davos, and I’d be okay.”

Oh my gosh, I have things to say about capitalism, and I can explain to you return on investment. So, in that sense, even though I didn’t write about ROI, I understand it. And you can’t scare me. I think one of the things about being an immigrant and an outsider, having grown up in a certain kind of way, is I know what it’s like to be questioned for being in the room. And I think that I feel very confident about walking into any room now. You can send me to [one of the World Economic Forum’s annual meetings in] Davos, and I’d be okay. I don’t think I would embarrass you. I think that’s the kind of position I want to have about my printed work.

It’s one thing for you and I to have a conversation, which feels so evanescent. But it’s another thing entirely to say, “These are my words. And my name is on this. And this is what I’m saying about this subject.” Because I speak about Koreans and Korean Americans and about certain families, even just in fiction. Whether I like it or not, people take that quite seriously now—especially now. And I do feel the sense of responsibility. I know a lot of writers don’t like that, but I don’t want to pretend like it’s not happening when it is happening.

Lee (right) speaking with Claire Messud (left) at Harvard University in 2018. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

SB: Yeah. I heard several interviews where you spoke about—in the writing of Pachinko in particular—feeling this heavyweight and responsibility about writing about the Korean Japanese as a Korean American.

MJL: Absolutely. Because I’m not Korean Japanese, and I think that all the discussion about cultural appropriation makes people insane. It doesn’t make me feel insane at all. I think, “You know what? I’m not Korean Japanese, but I did the homework.” And I know because a lot of Korean Japanese people have said to me, “Thank you for getting it right.” I’ve never had a Korean Japanese person tell me I didn’t get it right. So I know that those decades that I spent were not in vain.

SB: Another element of time in your writing is the omniscient narration, which, as you pointed out in this great conversation you had with the novelist Claire Messud, takes a long time. Tell me about this, the time element of omniscient narration.

MJL: It’s weird because it’s a device that used to be used pretty much universally. And then, apparently, some literary critics have said, “Because God is dead, the omniscient narrator has to die.” And I thought, That’s really interesting. Because the idea of omniscience is that you know everything, from beginning to end. And for me, that’s the most interesting way to write. I can’t imagine writing fiction anymore in any other mode. And I think it’s because I am really interested in every person in the world. Crazy, because you can’t put everybody in the world in your book.

“I am really interested in every person in the world.”

SB: [Laughs]

MJL: But even if I chose, let’s say, thirty characters, I’m fully aware that they’re in the world. I’m not writing speculative fiction. I don’t write fantasy, I don’t write mystery—all categories of fiction that I think are wonderful. I am writing realistic social novels, and that means that I need to include everybody.

And that takes more time, because I don’t know what it’s like to be an HVAC contractor. So if I’m writing about an HVAC contractor, I talk to some. I meet them. I follow their work. And I think every journalist, every academic, would understand what I’m saying.

Every anthropologist, certainly, would understand this idea of being an observer participant. But it has given me so much humility about what I don’t know because there are things I still want to say, but I don’t want to get it wrong. I really think sometimes the problem with being in media—and you and I participate in media and culture—is the astonishing blindness for the lives of people and what they go through. I don’t want to be that writer. I’m not interested in that. I didn’t give up money and power and status for that. Does that make sense?

SB: For sure. I also think I should mention—and I found it interesting that you mentioned this transition away from the omniscient narrator—that before you sit down to write, you read passages of the Bible.

MJL: I do. So weird. Yeah. [Laughs] It’s my Willa Cather thing, yeah.

SB: What does that time mean to you, the time you spend sort of taking in the Bible in that way? Not necessarily at church on Sunday, but before you ritualistically sit down to write?

“Looking at a holy text with all its controversy reminds me of language and the need to record what we believe.”

MJL: [Sighs] It’s such a weird thing, and my friends and my colleagues have told me how strange it is, but I can’t imagine not doing it anymore. What does it do? It gives me a sense of eternity. It reminds me how people in the world believe in God. It reminds me that we need a governing philosophy for life. And whether you’re agnostic or atheist, whether you are a secular humanist, whether you’re a Buddhist—whatever you are—I think looking at a holy text with all its controversy reminds me of language and the need to record what we believe. I look at it in a very strange way.

I read a chapter, I read the commentaries, I read it again, and then I try to write down something that puzzles me. There are things I don’t agree with, and I go, “Well, why is it that way?” But it’s wonderful because it sort of engages me. People have other things. I know that other authors may turn to classic Latin text or Greek text or the Bible or the Koran, or I know people who light candles. [Laughs] There are a lot of things people do to get themselves away from the world. For me, I turn to something that means so much to so many people. And also, it is a text that’s despised by so many people, too, and that’s as important to me.

SB: Turning back to Pachinko. When it comes to time, I had to ask you this. And I actually don’t know that I’ve ever seen you speak so much about this, so I’d love to hear you elaborate on the timeline of the book, the span of the eighty years. You’ve mentioned previously that it was going to be a five-year book.

MJL: Yeah.

SB: And it became this eighty-year book. The story spans from 1910 to 1989. How did you come to this particular timeline, and what was it like for you to span such a vast—I mean, a lifetime, really—eighty years?

MJL: I think if I had known how difficult it is, I wouldn’t have done it. So because I wrote a draft called “Motherland” before about Solomon, I thought, Oh, this book is not very good, but I guess I’m done. And then, when I moved to Japan in 2017 with my husband—

SB: 2007.

“I needed to meet a couple of hundred Korean Japanese people, and that’s what I did.”

MJL: I’m sorry, 2007—with my husband. See, I wanted to pretend like it didn’t happen. [Laughter]

So when I moved to Japan in 2007—and you were with me, right, Spencer? [Laughter] I have a primary witness. When I went there in 2007, I really wanted to think more about this book, because it had been haunting me since I was in college. And then, when I started to interview everybody, I started to realize, You don’t know what you’re talking about. All that research that you did in books, and even meeting a couple of people who are Korean Japanese in New York, didn’t mean shit when you went to Japan. Because I needed to meet a couple of hundred Korean Japanese people, and that’s what I did. I went to their houses, their businesses. I went to all the different places where they live in Japan because they were everywhere. And there aren’t that many now. It used to be almost a million, and now it’s probably down to like six hundred thousand. Then, of course, you have this issue of intermarriage. Or people who don’t want to identify. So you had all that stuff, and I wouldn’t have understood to take the numbers and then to have the stories.

And again, I had to go there and listen and watch and really rethink everything that I knew. Then I realized, “Oh, it begins with the first generation.” Then I thought, “Okay, I guess I’ll try that.” Sunja didn’t exist in 2007. She existed around 2010. Noa didn’t exist. I only had Isak, and I only had Moses. So the fact that those people showed up in Japan—[laughs] that those characters showed up…. See, I call them people because in my mind they’re so clear, I could see them.

Lee (right) with her husband Chris (left) in Tokyo in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Lee (right) with her husband Chris (left) in Tokyo in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Lee (right) with her husband Chris (left) in Tokyo in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Photo taken by Lee in Ikuno, Japan, in 2007. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

Lee in Tokyo in 2007. (Photo: Kerry Raftis. Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

SB: But it was these four years you spent living in Japan, where your husband had relocated for his job, and immersing yourself in the lives of these people in a way that I think, had you not moved there, maybe you wouldn’t have had that level of access. I mean, being able to live in Japan for that duration of time and interact with all the people you got to. It’s quite extraordinary.

MJL: Also, I think it was helpful that I got older. I think very often when we think about time and delay, you think, I didn’t get what I wanted. Very often, the thing that you want—the wish, whatever the wish is—you kind of want it fast. This is a problem with our brains right now. We don’t want delayed gratification. We want gratification. We want it yesterday.

That said, when I was living in Japan, and also when I ended up publishing [Pachinko] in the United States, in 2017, all that delay, I was also getting older. I was also a parent and a wife, a friend, the daughter of aging parents. I’ve lost friends to cancer, to suicide. All those things, they change you and they change the way you write because they change the way you think. They change what you believe. And I think the older writer, in that sense, is really in Pachinko in a different way. When I’m working on this book right now…. I’m going to be 55 soon, and I think that I’m a different person than when I was 35 and I liked me at 35; I like me at 55. But I think at 55, I feel so much more compassion for people and what they’re going through, just because I think, Oh, I could lose you. I could lose you, and my life would be impoverished for it.

SB: In Pachinko, time also appears in the form of this gold pocket watch.

[Laughter]

MJL: Yes.

SB: It might seem like a minor detail in the book, but it’s this gift that Hansu gives to Sunja.

MJL: Mm-hmm.

SB: Hansu teaches her “the difference between the long hand and the short hand and how to tell time.” While this subject might seem minor, I—

MJL: It’s not minor.

“At 55, I feel so much more compassion for people and what they’re going through, just because I think, Oh, I could lose you. I could lose you, and my life would be impoverished for it.”

SB: It’s not. And I wanted to get to that because there’s so much meaning and metaphor buried, embedded into that device, that watch, about the value of time, who controls time, how to mark time [laughs], and why all of that matters so much. How do you see it? And what was your thinking by inserting that particular watch into the story?

MJL: Well, it’s really important that he purchases the watch for her. He spends his own money to give it to the person that he loves, and he wants her to know that time exists now. Because, remember, this is a person who never had a watch, who never had a clock, who never had anything to mark time, but all of a sudden, she wants to see someone, and it’s really difficult to know what that time means.

He’s actually saying, “You will now always associate time with me.” What an incredibly wild thing. [Laughs] it’s an act of domination, but it’s also an act of communion. Like, “You and I will have watches in a world where not everybody has a watch. And then also this symbol, this piece of jewelry that men have—it’s a pocket watch. It wasn’t meant for a woman. So he’s giving her a masculine totem to a woman who’s an uneducated, poor girl.

SB: And it’s from England.

MJL: And it’s from England.

SB: So there’s colonialism embedded in there.

MJL: Thank you. So there’s colonialism, and there’s capitalism—all in this thing that he purchases for her. And then also when she sells it, she’s also doing something really quite astonishing.

The traveling of that pocket watch in the story was really important to me. In the same way, I learned about time in a different kind of way. But what I love also about this idea of time, and it’s no different than when you have that aphorism about, if you see a gun on the mantel, it has to be used in the story. There’s a plotline of the pocket watch, no different than there’s a plotline for any of the minor characters in Pachinko. I guess that’s the other reason why everything takes me so long, because I am literally thinking about the plot of an inanimate object and the metaphor and the imagery that it bears. But thank you for noticing it. I’m going to walk away happy now.

[Laughter]

SB: Well, this makes me also think a little bit about something you said recently on a BBC Sounds segment. You said, “Women are constantly negotiating spaces and negotiating time and negotiating hierarchies.” And the same was true for Sunja one hundred years ago. This feeling of negotiation, I found that very powerful, that link between what you were talking about in this present being so tied to this world you were depicting in the book happening a hundred years ago, and not that much has changed.

“I have so much privilege as a woman. But even with me, I’m endlessly negotiating the management of ego if I want to be persuasive.”

MJL: It’s heartbreaking for me to think about how women are treated now and in the world. I’m an American citizen with education and privilege. I have health insurance. I have so much privilege as a woman. Even with me, I’m endlessly negotiating the management of ego if I want to be persuasive. And there are things I want to persuade you [of]. I want to persuade the listener of this podcast. It’s odd, because you’re thinking, Well, you’re not running for Congress. What is it that you want to persuade? And I think, Well, if I could change the way you think, maybe the things that I want would change.

So, for example, I was recently talking to two women, and I said, “I feel like I can be incredibly pleasant, but I could be really difficult because I’m not giving up on the thing that I want.” But it’s that combination of being pleasant and difficult. But I think that’s a very gendered way of trying to get what I want, and it’s considered shameful to want things. But I’m 54; I don’t know how much time I have. I could live to 95, but I could live to next week. I don’t know.

When you’re aware of that, and I think having had an illness for such a long time—and I don’t have it anymore—I’m so supremely aware that I’m not going to give up on my wishes just because it’s considered greedy. That’s a word that women are often told. “You want too much.” And I think, Actually, I’ve already given up on these things. People like me don’t get those things. So, fine. So then I’m going to want other things. I could be wrong. Things are different. But I’m fully aware that I’m not going to get a hundred out of a hundred, and I’ve decided to want what I want anyway.

SB: Yeah. You’ve also described this before, that you feel really outside, and that doesn’t just apply to being a woman. It applies to all these other different things. And we’ll probably touch on these “tribes,” as you call them. But this one tribe, you said you’ve really felt a sense of being in line with is books [laughs], the tribe of books, and that there’s this existential alienation you’ve felt that has become a really useful lens. Could you talk a bit more about that, just elaborate a little bit on this existential alienation?

MJL: Yeah. I remember when I was younger, I thought, “Oh, if I had a friend, I would find love. I would find acceptance.” I have some friends now, and even then, I can still feel like, “Oh, we’re different.” But I want so much not to be. There are people who want to be different. And I’m like, “No, I’m just a weirdo,” and that’s okay. [Laughter] But because I’m not willing to conform entirely. Like, I’ll be pleasant, but I’m still difficult. When I went to college, I thought, Oh, I’m going to meet “my people,” and I didn’t.

That was upsetting. I thought, Oh, if I meet the right Koreans…. And then I met them, and it was like, Oh, no, I’m strange for Koreans too. And I thought I’d meet the feminists, and I thought, Oh, I like them. But no, I’m different because I have this other way of looking at things. And then I thought I would meet the writers. [Laughs] So, in a way, what I’ve done is I’ve actually built an increasingly huge, beautiful, heterogeneous community. I can call upon, actually, I think a lot of people now and say, “I love you.” And they love me, and I’m accepted. And yet I think, Oh, no. And then I realize that all the philosophers had been thinking about this for a long time. That, in the end, we are still so different. If you’re really honest, you really are so different. You can have comfort and love.

“Because I can call upon centuries of books, it makes me realize, ‘Oh, I’m not alone. This person has felt this moment.’ I think that can be so comforting.”

And then, when I think about all the people that I’ve lost to suicide, I think it’s because this was the hardest thing to accept. Very often, when people are in a lot of pain, we want to say, “Oh, please get out of the pain because we love you.” Then you realize when they’re suffering, you don’t know what they’re going through. So we’re going right back to this decision. Do I think that suicide is justified? No, that’s not what I’m saying. But I am saying that this feeling of alienation and not understanding what people are going through is something that I really respect. But books? I’ve noticed that because I can call upon centuries of books, it makes me realize, “Oh, I’m not alone. This person has felt this moment.” I think that can be so comforting.

I’m so sad that people don’t see that. Because if you are just going to go to the internet and the phone or social media to find that comfort—I hate to say this—but I don’t think you’re going to find it, and it’s certainly not going to last. Perhaps for a moment, a cat video or a picture of a good act could give you some comfort and connection—perhaps—but it’s not as lasting as something that you can find in a book. Maybe that’s why I do feel the sense of the missional aspect of literature.

SB: Yeah, you’ll return to the book much more likely than the cat video again and again. Although I guess the cat video could be considered something addictive to look at, but I think the level of depth you’ll find returning to a book will be a little different.

[Laughter]

MJL: Yes, the otter videos are pretty good, too.

[Laughter]

SB: So going to this “tribes” thing, you wrote a piece in The New York Times a few years back where you sort of laid out all these tribes: “immigrant, introvert, working class, Korean, female, public school, Queens, Presbyterian.” Did you write this in an intentional order? Do you view yourself as an immigrant first and foremost before being an introvert, working class, Korean, et cetera? I was curious because I found—

MJL: Oh, I love that.

SB: … I found the order of that quite interesting. I think a lot of people would identify, “Oh, I was born in Korea, so I’m a Korean first,” for example.

Lee (left) as a child in Seoul. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

MJL: Mm-hmm. I think the ordering of the list is curious, depending upon which you see as first and which you see as last because it can actually be inverted. I don’t think I walk around thinking I’m Presbyterian all the time, but then I realize how I behave, and I think, That is so weird that you’re a Calvinist. [Laughs] How did this happen? I don’t really understand how this happened to me where I became a Christian.

I don’t understand how this happened to me that I became an immigrant. It wasn’t my choice in some ways. My parents brought me here. I didn’t say, “Oh, I want to live in America.” Now, if you ask me, I’m going to tell you I do want to live in America. I want to be an American citizen, because I can choose. I can. If I wanted to go to Spain and maybe wanted to become a Spanish citizen, perhaps I have a shot. I could probably call lawyers and ask, “How does this work?”

But I guess that order—I do think that it changes a lot, and every decision to put one in, I know that there’s a cost. When you tell people what team you belong to— It’s kind of like if I said to you, “Well, I’m a Jets fan” or “a Giants fan.” People have responses. [Laughter] So if you think about the marginal cost of declaring a sports team, just imagine saying, “I’m a feminist,” because in parts of Korea, they’ll want to burn me at the stake. Whereas other people might say, “Oh, you’re one of us. I’ll hide you in my attic.”

“As much as I love Korea and Koreans and being in South Korea, I don’t have as much skin in the game because I could always leave.”

SB: To go back to Korea, or to Seoul, your memories of Seoul, you’ve described them as “tinged with gray scale.” I think there’s this romantic thing that happens when you have early childhood memories of a place. And I know you’ve traveled back to Seoul and to Korea, and I was wondering what you think about this dissonance between your experiences as an adult in Korea versus what your memories tell you of the time that you lived there until you were 7.

MJL: I have such a romantic view of Korea because the adult Korea that I know comes from books. It comes from other people. When I’m there, I have such a positive association. The reason why I have to say that is because it’s not that experience for people who are in Korea. There are many people in South Korea today who call it “Hell Joseon,” literally, like, “Korea is hell.” A lot of young people feel this way. The reason why I bring that up is because there’s a part of me that wants to believe that the Korea that I experience is wonderful.

Lee (left) as a child arriving in the United States with her family for the first time in March 1976. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

It’s kind of like when you and I, let’s say, go to a nice restaurant, somebody might be really nice to us. Let’s say the maître d’ is incredibly nice to us. They’re like, “Oh, Spencer’s here, Min’s here. Wonderful. Let us bring you a drink.” And then later on, if there was a camera, let’s say this maître d’ is yelling at a busboy in the kitchen. We don’t know. But you see, I know that I’m treated differently in Korea than other people are. Most people who are in other countries have that experience of complexity and inequality.

I have to be really so careful of not drinking the Kool-Aid. As much as I love Korea and Koreans and being in South Korea, and I have so much fun there, I don’t have as much skin in the game because I could always leave. I think that criticism can be charged and leveled against people who are visitors. Does that make sense?

SB: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. And I guess extending that out to Queens, I would love to hear what your memories are of that place and what it’s like for you to go back to Queens now, and the dissonance maybe that exists between that time and today.

MJL: Well, when I was growing up in Queens, it was so much more culturally mixed with white ethnic people. That has changed. If I go back to Elmhurst right now, Elmhurst is in Maspeth. Back then, there were lots of Asians, but there were also more German immigrants, Polish immigrants, Czech, Hungarian—that was very normal—Italian Americans. And they had just got there. Or second generation, maybe, very one point five. Also, there were South Asians. Very few Koreans.

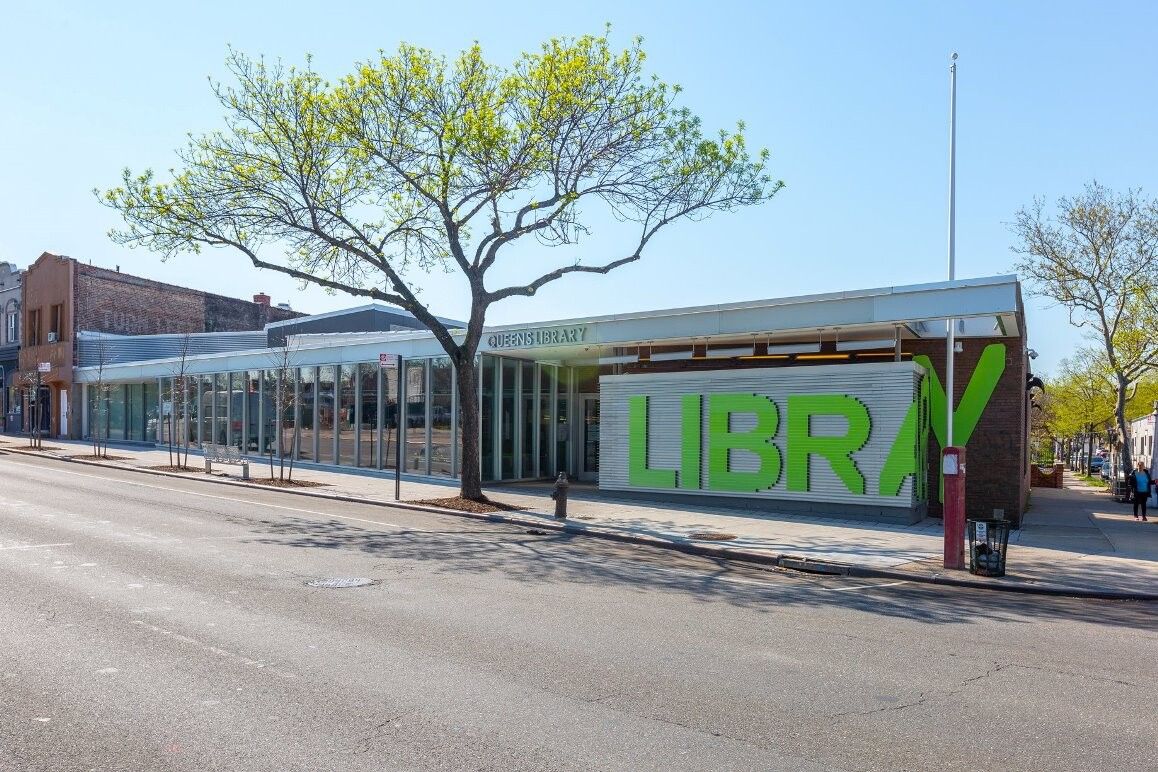

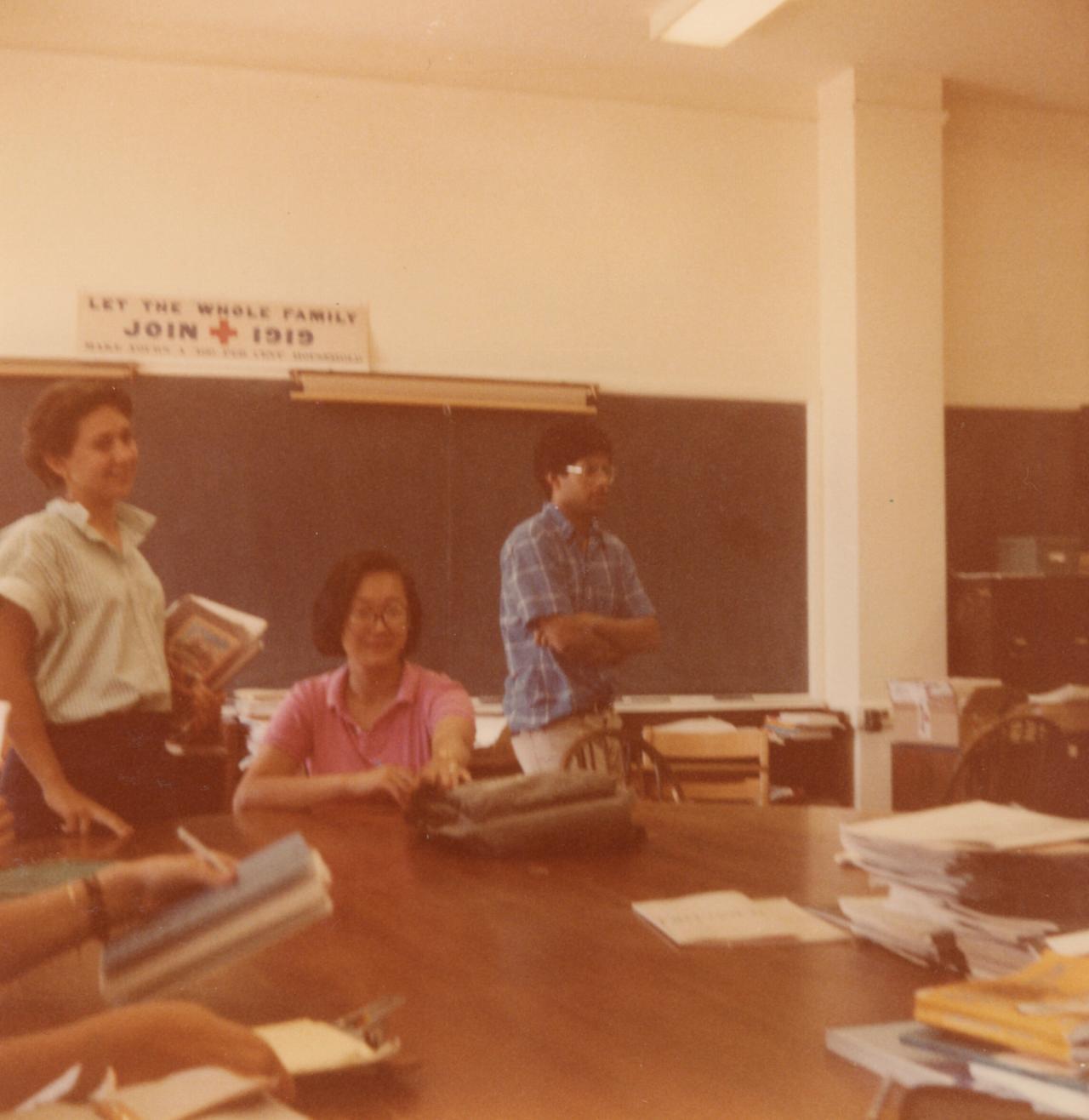

The Queens Public Library at Elmhurst. (Courtesy Queens Public Library at Elmhurst)

Now, if you go to Elmhurst, you will have some of the residual white ethnic immigrant communities, but you also have a lot of Latino and a lot more Chinese American. I know this because I was recently at the Queens Public Library in Elmhurst, which I really care about, and it’s so gorgeous. Oh my gosh, it’s so nice. It’s like all this glass and auditoriums and all the shelves with different language books. I just thought, Whoa, I loved it then. But this is awesome. It’s almost like going to a high-rise compared to what it used to be. So there are wonderful improvements.

SB: And I have to bring up the introvert tribe here, which, I think to the listeners, they’d probably be surprised to hear that you were such an introvert. I guess maybe, to a certain extent, still are, but—

MJL: I’m really an introvert. I would rather be home.

[Laughter]

“I’m really an introvert. I would rather be home.”

SB: But I guess I could say your ability to be a public speaker has completely transformed over time. You didn’t speak much as a child.

MJL: I hardly spoke at all. People were very worried. You can confirm this with my family. I took a lot of classes to learn how to speak. I think that right now, I feel this real sense that there are times when I need to speak, and therefore, I should. The thing that really helps me is to think about what’s needed. If I didn’t think that what I needed to say needs to be said, I wouldn’t say it, so I don’t. If I don’t comment on something, it’s because I think, I don’t know if that needs to be said by me.

Lee during her time at the Bronx High School of Science. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

SB: Well, I was curious to hear a little bit about this, because during your high school years at Bronx Science, you sought out these summer classes at two different boarding schools.

MJL: Changed my life.

SB:Tell me about these classes. Tell me about your time—it was at The Hotchkiss School and Phillips Exeter Academy where you were taking classes to really understand how to orate and speak publicly.

MJL: Well, I joined the debate team, which was free, my freshman year at Bronx Science. I was so bad at it, but I wanted to be good. I really admired people who can do this. Of course, because [in] literature, you want to be that heroine or the hero who could change people’s minds and persuade. I thought, I want to learn how to do that. I want to learn how to talk well. Because, in the West, it’s so important. I didn’t want to be ignored, and I didn’t want people to think that I was dumb. I still don’t. And I think this is the reason why I really have a chip on my shoulder.

In order to compensate for my chip on my shoulder and my insecurity, I work really hard to overcome it. There’s a part of me that thinks, Oh, if I’m going to be on stage, I’m going to kill it. I do so much work when I do a public performance, and that’s the reason why. But it’s work. You’re never going to see me phone it in, and I’m not sorry. There’s a real need for certain things to be said, and therefore, I go through the effort.

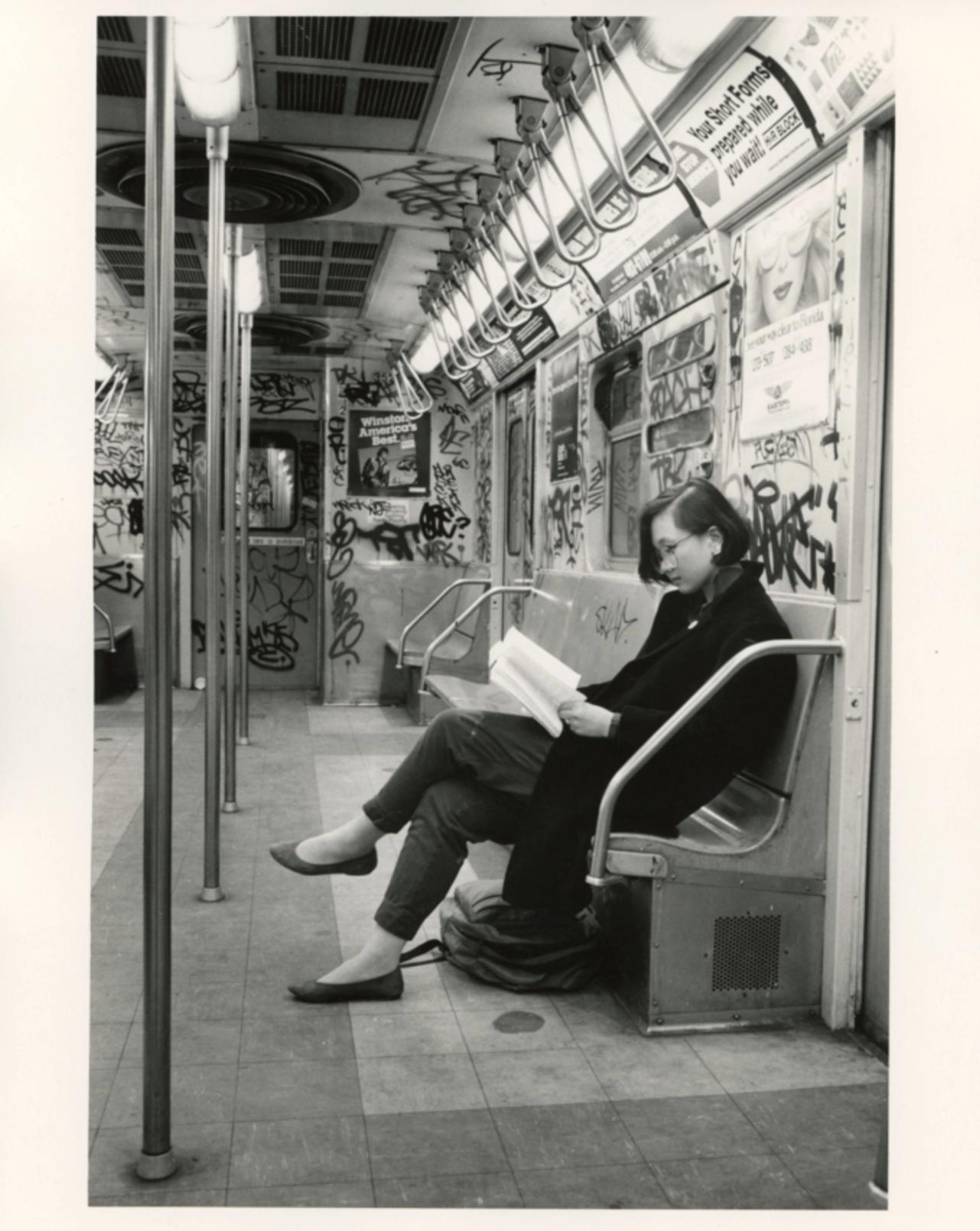

Lee reading a book on the train on her way to Bronx Science. (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

But those two classes that I took were on public speaking, those two summers, and it cost a lot of money and time for me to go. I had to persuade my parents: “I need to figure this out because I have no friends. I don’t know what to say in class. I think I need to take this class, and they don’t offer it at Bronx Science.”

Then I went, and it was torture. It’s so hard for an introvert who doesn’t talk to get up there and tell a joke. Over the years, I’ve gotten better, because I’ve had more practice. I’m like the marathon runner who couldn’t walk, and now I could run a marathon. I could do it. I could give a speech in front of five thousand people and hopefully persuade. But it’s very hard. I cry a lot. I think that’s when you really know that I’m an introvert, because I’d rather not need to do it. I would much rather be in the audience. I love clapping at other people. It makes me so happy. [Laughs]

SB: In fairness, some of the best public talks, I think, are when people cry. I think there is a strength in it, and there’s a form of persuasion to be found through tears.

MJL: I guess. But it’s very uncomfortable to be that vulnerable on stage. And for people to think that you can’t control your emotions. I would like to be more polished. So I feel like my content is often very well-managed or earned, but then I wish the execution could be more fluid. I love it when people can just be funny. Don’t you admire funny people?

SB: Flawlessly funny, yeah.

MJL: Oh, my gosh. When I see good stand-up, I think, Oh, that’s so good. I just want to clap all day.

[Laughter]

Lee giving the DeMott Lecture at Amherst College orientation on September 1, 2019. (Photo: Jiayi Liu. Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

SB: You mentioned this illness you experienced earlier, and I wanted to bring that up. Around 18 or 19, I guess, you learned you were a chronic hepatitis B carrier, and your doctor told you you’d get liver cancer in your twenties or thirties. And then, later on, after treatment, you were able to be completely cured of this disease—incredibly.

MJL: It’s incredible.

SB: Could you take me through this journey from then to now? And how did this shape your sense of your own mortality? And also, I guess even beyond that, your relationship to time and to writing?

MJL: I think we’re always thinking about death, all of us. It’s not a bad thing. Actually, I think it’s good. I think it’s good to think about death. It’s good to think that this life that we have is wild and beautiful and this crazy animal. I want to recite a Mary Oliver poem all of a sudden. I won’t. [Laughs] But I guess I learned when I was in high school, I gave blood because a friend of mine was running a blood drive, and then it turned out that I was a carrier. Then, when I was in college, I got really sick, because, when you are a carrier as a status, it doesn’t mean that you are sick, but then you can give it to yourself.

Lee (center) with her husband Chris (left) and son Sam (right). (Courtesy Min Jin Lee)

That’s what happened to me in college. Then the doctor, this very famous doctor at Yale New Haven Hospital, said, “You’re going to get cancer in your twenties and thirties, but it’s going to be okay, in some ways, because we have liver transplants now, and it’s an organ that grows back, but it could be very bad, too.” I was 18. I mean, it’s quite a bit of news to get. But it did make me immediately never drink. I don’t drink alcohol even now, even though I’m cured. Then I would be really mindful of the fact that if I ever got tired: “Oh, it’s like when I got sick in college.”

It allowed me to quit being a lawyer. I was a lawyer for almost two years, but because my hours were so absurd, I ended up quitting because I didn’t want to die on my desk. It did make me get married earlier. I met my husband when I was 22. I got married at 24. I’ve been married for thirty years to the most lovely human being. I never thought I would have children, but then I thought, Oh, maybe I do want to have children. After I had been with my husband for enough years, I thought, He’s such a good person. I could imagine having a child with him. And if I did die, he would be okay.

I was actually always thinking like this, even as a very little person. When I look back, I think, Well, how did you get through it? I don’t really know. But I do know that all of it, even now, even though I’m well…. And after I had my son, I got super sick. I was so sick. All my joints [were swollen] and I couldn’t walk because what happened was my liver became inflamed, and it affected every single toxin in my body. I was in constant inflammation. I couldn’t lift a coffee cup, and I couldn’t open a doorknob. So when I saw this very famous liver doctor, Dr. Magun, he said, “You know, I have this experimental program of interferon B, and you’re so young, and we think we should try it.”

I was like, “All right, let’s go.” And I did. It was three months of— It’s like chemo. You lose your hair, and you get sick all the time. I couldn’t ever leave the house. I had to cancel everything. The whole time, I had a little boy. He was only 3. I couldn’t imagine losing him or him losing me. I mean…. I’m sorry, I know a little bit about your background. [Tears up]

So I did the whole course of this treatment, and then about six months afterwards, I was cured. And I’ve been tested recently. And again, I’m totally cured.

SB: Wow.

“It’s really quite something to be able to watch your son grow up and to stay married for thirty years, and then to work on books that you want to write.”

MJL: It’s really quite something to be able to watch your son grow up and to stay married for thirty years, and then to work on books that you want to write. And I think that…. I want to be alive. I do. [Laughs] I want to be well, and I want to be alive. Just the other day, I was with somebody that I really adore. I love her so much.

She said to me that if she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, she would do the Dignitas program in Europe and end her life, because she wanted to have dignity. Although I understand it perfectly well, her reasoning, I felt so selfish. I just said, “You know, my life would be so much less without you.” [Tears up]

This is why I’m an introvert, because I would rather not be doing this. [Laughter]

SB: Well, thank you for sharing that. So you’re now deep into working on American Hagwon.

MJL: I am. Not a funny book. [Laughs]

SB: The third novel in your trilogy.

MJL: Yes.

SB: And I found somewhere where you said the first line of it—and I hope this isn’t disclosing too much—is, “The rules of engagement have changed already.”

MJL: Mm-hmm.

SB: The first lines of your other two books often get brought up by interviewers. I’ve noticed as well.

MJL: Yeah.

SB: And one is, “Competence can be a curse,” from Free Food for Millionaires, and, “History has failed us, but no matter,” from Pachinko. Collectively, what story are you trying to tell with these three lines in particular?

MJL: I think one of the things about being a diasporic person is I’m endlessly aware that I’m a person who’s moved from one place to another, and I keep moving. And you wonder why. Why are some of us sent out into the world? Right now, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees states that, if you look at the numbers, and I check the numbers pretty often, I think there are over a hundred and ten million refugees or displaced people in the world—I think “displaced people” is a more accurate term. A hundred and ten million, and what, there are seven or eight billion people in the world. It’s quite a big number of people who don’t have a place to put down their head in the evening.

You wonder, are they being punished? It’s certainly very often without your own choice. Here I am, living somewhere else, and all those lines, [they’re] really about surviving. How do you survive diaspora? And also, is it something always negative, or how do we change the world as a result of diaspora? It could be that I just took in what America gave me, but it could also be that I could take what I have and change America. It takes a bit of grandiosity and ego to believe that you have the power to change another person. But I think that because I’m so upset about the world, I’d like to change things. I would. I’d like to change so many things, actually.

“If you have thought about that existential question—and I need it like a glass of water if I was parched—please, give it to me.”

SB: I wanted to finish on something you write in the introduction to Best American Short Stories.

MJL: You read that introduction. Thank you. It took me so long to write it.

SB: “Without stories” you write, “we cannot live well. Each of us would exist dimly, not understanding the value of our brightest moments.” And a little bit later, you add, “Fiction is a light source in a world that tells us that there is no daylight left.”

This notion of fiction as a light source I just love so much, and it’s a beautiful, romantic thought, but it’s also a pragmatic one. It’s like a beacon. Quite literally a lighthouse. I wanted to hear you speak a bit about what you think makes it so, and how vital these “light fixtures”—novels, short stories, literary essays—are for us to make sense of the world.

MJL: Well, you’re not alone. The questions that you have, or even the questions that we can’t even articulate, if you think about feelings—and I think about feelings a lot, and about memory—sometimes they’re so amorphous, you’re thinking, I don’t feel well, but why do I not feel well? Why do I feel this sense of unease? Well, other people have thought about it. They’ve thought long and hard about it, and then they’ve explained it. Sometimes, they’ve even dramatized it. In fiction, you see the struggle of how a person handles that specific question.

If you want to, whatever that troubles you or ails you or where you feel alienated and in the dark, it gives me so much consolation to know that there are others who have thought about it throughout time. I don’t need to know that that author is alive. I don’t care what gender, sexuality, class, background you are. If you have thought about that existential question—and I need it like a glass of water if I was parched—please, give it to me. [Laughs] I feel that way. Then because I feel that way, I want to point somebody toward something.

Like, somebody was talking about being an English professor and how difficult it is, and immediately I thought, “Have you read Stoner by John Williams? Because he’s thought about it too, and I think you might like it.” [Laughs] And then I thought, “He didn’t ask you. Shut up. He didn’t ask you.” [Laughs] But of course, I definitely feel the sense of taking people out of suffering. There’s so much suffering. Maybe it could take you out of suffering. And again, it’s grandiose to think that any of us can make a difference. But I hope that we can.

SB: Min, thank you so much. It was a joy to be with you here today.

MJL: Oh, thank you, Spencer.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on October 20, 2023. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, Mimi Hannon, Hazon Mayo, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo based on a photograph by Art Streiber.