Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Michael Murphy. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

SPENCER BAILEY: Joining me in the studio today is Michael Murphy, the founding principal and executive director of MASS Design Group. Welcome, Michael.

MICHAEL MURPHY: Great to be here. Thanks for having me.

SB: I wanted to start this conversation with this notion of “Slow Spaces.” When Andrew [Zuckerman] and I interviewed you over Zoom a little more than a year ago, on April 9th, 2020, for our other podcast, At a Distance, you told us, “There’s an opportunity to create a Slow Food movement for the built environment—a ‘Slow Space’ movement, if you will. Slowing down doesn’t mean extending the time horizon of a building, which tends to scare developers and clients. What I mean by slowing down is being more intentional, more purposeful, and ensuring that the decisions we make are considerate of the chain effect they have on our world.” I was hoping you could elaborate a little more on this. What exactly would a world of Slow Spaces look like?

Cover of The Architecture of Health by Michael Murphy. (Courtesy Cooper Hewitt Press)

MM: Thanks for reading it back to me. I said it better than I was going to say it now. [Laughs]

But no, let’s dig into that. I think first I’d probably pull back and give some gratitude to the Slow Food movement, which has been, some would argue, a half-century of work, of advocacy, experimentation, and great meals, but a lot of incredible people working to really change our food culture and our food system through a very simple idea of binding what we eat back to where it was grown and who grew it. And that simple realignment of not just the things that go into our body, but acknowledging and recognizing where it was grown, its provenance, and who grew it, the people that transform it and labor to make it possible, and what that costs. Revealing the oftentimes invisible costs of our everyday consumption has transformed the way we see the food around us, and allowed much of our culture to ask different questions about what we’re consuming, and how we consume things, and its ethical implications, its environmental implications, its health implications.

SB: And MASS has done a lot of work, actually, around farms, and food, and agriculture. How has some of that work informed how you think about architecture and this Slow Spaces idea?

MM: We are starting to do a ton of work with folks who are in this space, but I think it has only further validated the idea, in my mind, that, at least in food systems and food culture, about, let’s call it twenty, twenty-five years ahead of building culture and building systems, they’ve been thinking critically about how we bind labor and place to what we eat, and I think we need to do the same thing in the built environment.

“[Slow Food has] been thinking critically about how we bind labor and place to what we eat, and I think we need to do the same thing in the built environment.”

The buildings that go up around us, where we spend ninety percent of our lives—each one of those bricks, each one of those screws, each one of those building materials has provenance, has an impact on a global supply chain, and has, of course, a big impact on the labor that creates it. There’s no way to untether those relationships. In fact, the true cost of what goes up around us, its environmental impact, its social impact, its health impact—those same variables that the Slow Food movement so righteously and accurately elevated in the conversation many years ago—we are finally now elevating in the conversation of the built environment. We’ve been too slow to use that term and acknowledge it. But I think now that we’re in that space and asking those hard questions, especially after this pandemic or in the middle of this pandemic, rather, I hope one outcome is that we start demanding much more from the buildings around us and the built environment around us, and how it performs, and how it’s responsible and accountable to these broader value strains that are inevitably impacting us every day.

The Gheskio Cholera Treatment Center in Port au Prince, Haiti, designed by MASS Design Group in 2015. (Photo: Iwan Baan. Courtesy MASS Design Group)

SB: Slow Food, of course, came out of this world of industrialized food. It was a response to McDonald’s, a response to TV dinners, to this fast mode of consumption that people, I think, started to realize, Whoa, this doesn’t make me feel so good as our cities become built quicker, cheaper in this more industrialized way without taking care to understand, as you were pointing out, each part, each brick. I think, in turn, we’re starting to feel a little bit more how buildings physiologically, psychologically impact us.

Do you think we might reach a point where people outside of, let’s say, the worlds of architecture or art or design are actually thinking about this? Where it can become somewhat more mainstream, the way Slow Food has become? Because now Slow Food, of course, is…. You could argue that Whole Foods is part of Slow Food, and Whole Foods is now owned by Amazon. [Laughs] So it doesn’t get more mass than that, really.

MM: You’re absolutely right. But the beginning was a couple of chefs, Alice Waters, in particular, [and] Dan Barber up at Blue Hill.

SB: Carlo Petrini, a farmer in Italy.

MM: These amazing, innovative advocates who were using their platform, and their trade, to weave a story that was not just about the mechanics of what we eat, but also about the spiritual dimension. That it was, in a sense, a piece of art. Architects are doing that, and have done that, but it hasn’t pushed into the broader marketplace, where the public is demanding these variables in a way that we are seeing in food. Which is why I say we’re kind of behind that movement, and I think that is exactly how it has to go. And also that we are accounting for that change—the costs and the time of what it would take to do it right—and pushing back against the efficiency-at-all-costs, at any cost, argument about how things are constructed in our world. Because, of course, we’re only calculating one variable in there: the dollars we spend before it goes up, but not the very expensive impacts it has on our environment and our communities after it’s living in our communities for generations to come.

“The built environment changes us every single day, whether we acknowledge it or not. And we have a responsibility to ask, ‘What is the true cost of these decisions?’”

For us, in our work, it does begin at a theoretical and philosophical foundation, that the built environment changes us every single day, whether we acknowledge it or not. And we have a responsibility to ask, “What is the true cost of these decisions?”, and to push back on the marketplace to say, “Maybe you can get this one product at a cheaper cost, but what’s the environmental and social impact of that cost decision, that value decision?”

SB: MASS stands for “model of architecture serving society.” I’m wondering, in the context of what we’re discussing, was there a model for you? Were there any architects practicing in a way that you were like, Oh, that’s how that’s a model closer to how things should be?

Murphy with the team at MASS Design Group. (Photo: Tony Luong. Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MM: The answer is yes. There [has] been a long history and trajectory—a strand—of architectural thinking practice and philosophy that goes all the way back, I would even say, to William Morris, from the Arts and Crafts movement in the 1860s and seventies and eighties that can carry forward. In some strands there is Frank Lloyd Wright. There’s strands that continue into [a] postwar-Italian form of architecture, like Giancarlo De Carlo, carry forward into the seventies and eighties. Our great friend and colleague—rest in peace—Michael Sorkin was an advocate and brilliant mind around architecture’s impact in the world.

One of the ones when we grew up, when we studied architecture in the early 2000s, Sam Mockbee at the Rural Studio was a beacon of what could be possible, at least with a school program, of how to build carefully, with intention and in partnership with place and people. So there’s always been a continuity. Although I think the story of that continuity, of that practice of architecture, has been fractured, under-theorized, and forgotten in some places.

When we began, in 2007, ’08, I really didn’t feel like I had a grounding of the past, of how so many practices are asking very similar questions, but are forced, or hindered, in the way the market performs, of how they can serve society as effectively and as much as they want.

“[MASS is] in service of something greater than ourselves. Not just as a practice, but greater than ourselves as people. We’re servicing community. We’re in service of place.”

The name really does focus on the idea of service, that we are in service of something greater than ourselves. Not just as a practice, but greater than ourselves as people. We’re servicing community. We’re in service of place. I don’t think that’s a critique of architecture more broadly. Architects are, and architecture is, always in service, and is always socially bound and environmentally bound. It’s just that the market doesn’t demand we acknowledge those pieces as much. When we began, we really wanted to elevate, and put a stake in the ground, around the idea that we are in service of place, and service of people, and then to try to find a practice model that can’t sell that off, that is always accountable to that. Which is why we configured ourselves as a nonprofit organization early on.

SB: Yeah, which, for those not in the world of architecture, is quite rare. The notion of a nonprofit architectural practice, and particularly how you’ve set it up, and maybe you can speak a little bit to that—how does that impact the work you do, and how has that allowed you to practice in this very service-oriented way? And I think “service” here in a more egalitarian sense, not just servicing a client.

“Architects are, and architecture is, always in service and is always socially bound and environmentally bound. It’s just that the market doesn’t demand we acknowledge those pieces as much.”

MM: There’s certain benefits, and there’s definitely certain constraints, for being a nonprofit. One thing I’ll just say at the outset is, when I say we’re a nonprofit architecture firm to other architects, I have often gotten the response from them, which is, “Oh, hey, so are we.” Which is supposed to be a joke about the fact that we as architects make zero money.

But I think there’s actually a kernel of truth in that. Which is, one, if you unpack that jibe, architects aren’t making that much money for the incredible amount of work they’re doing. Why is that? Why is the market really not supporting the excessive amount of research and study and innovation and iteration that goes on in architectural practice? So the business model isn’t really meeting the work, the labor, and there’s a problem there that is not being acknowledged and solved.

The second thing is that architects, historically, traditionally, do give away an enormous amount of work. Free labor, free intellectual capital, not just to get projects—though that certainly happens—but to nonprofits, to community groups. There’s always been this percentage of donated service in the practices that I know and that we love. That’s always been core to the work.

Cover of Justice is Beauty by MASS Design Group. (Courtesy Monacelli Press)

Structured as a nonprofit, we’re acknowledging those two things that are part of typical practice, and being accountable to them, and really counting them. Specifically counting how much we give away, who we give it away to, and how we can raise money to give more of it away. So now we give away about two million dollars a year in service, which, I would say, is more like a social-enterprise model. More like—I don’t want to say Tom Shoes, it’s not really the best analogue. Especially new Tom Shoes. Old Tom Shoes, maybe like a little bit more. But we still generate fees. We still charge fees to work, but we are very intentional about giving work away to organizations, nonprofits, [and] community groups that are not at a place yet where they can afford to not just pay for services, like really understand what it would be to pay for a building, at a really, really early stage. And that offers certain images. You’re helping these folks bring a brilliant idea into an implementable idea. We’re operating not just as architects, but as, really, consultants in project development, I think, would be more accurate terminology.

SB: How does having a board, and also getting donations, but then also having this revenue that continues to drive the firm forward, how does that all work together?

MM: That’s the other important piece, which is, we have a board of directors, and I serve at the behest of the board. So I don’t own the company, nor do my partners; we don’t own any equity. So that has certain, we call it, “integrity checks”: The decisions we make, what projects to do, for example, where we might work, where we might push the envelope and explore options or opportunities. We still have a lot of latitude, but to some degree, it still always has to be verified by the board. It’s not like the board is saying, “Okay, you can do this, you can do that.” But we have to report to them. And we’re reporting to them not on profit; we’re reporting to them on value. That’s a really interesting constraint that is structurally integrated into our practice.

Tomorrow, if someone called me and wanted to do a huge tower in downtown Manhattan across the street, with a huge profit margin and a lot of flexibility, I couldn’t say yes. I would have to make an argument why it has social, environmental, and cultural value. I would have to make the case to the team. I would have to make an argument to the board. And I’m not saying you couldn’t make the argument, you couldn’t produce a compelling or persuasive case, but we could never just say yes to something just for financial reasons. We’d have to say yes under the rubric of service of environmental, social, and cultural impact.

SB: It’s like a recalibration of the meaning of value, beyond something monetary.

MM: Another piece of it is, it’s de-centering the authorship of practice. We look back at great architecture, and we talk about architects, this kind of mythology of the sole practitioner and genius auteur.

SB: Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Kahn.

MM: Sure. Yeah. You know, I even fall into these traps. We all do. It’s not to say they weren’t great geniuses and brilliant visionaries. But you look around at the buildings outside the window—we’re in this beautiful setting now and around buildings, for those who are listening—those were all built by teams. It’s more like a symphony or a pit team; it’s less like a single, visionary auteur.

And I think for us to expand the expectation of the public to demand more from architecture, we also have to de-center that authorship component, to say that we can expect more from everything around us, invite new policy, expect and demand more engagement locally with community groups of what goes up, and [expect and demand] better design as well. Better breathability of buildings post-Covid, to make us healthier. We can do so through a multiplicity of different angles that isn’t just convincing one singular architect.

SB: How do you think about time in the work you do as an architect? And I’m thinking here not just in terms of a project’s timeline, but across the sweep of human history. Philosophically, where do you see the line between architecture and time?

MM: I sometimes refer to it as the superpowers of architecture. One of the things that may be the thing that I find the most compelling about it is that it operates on a longer time horizon than, let’s say, some of the other art forms or other creative disciplines, certainly media. If tomorrow we got a building contract signed, it might be three to five years before it’s built—and we’re celebrating its construction. So we are having to solve problems, [but] not the problems that we encountered today. We’re having to project forward the problems, or opportunities, that we think will be consistent from today till five years from now and beyond. Ten, fifteen, twenty years from now.

I think it’s a really privileged position to have to always be living in that space, to say, “How do we boil down these issues to their essential qualities that are going to consistently affect the human condition well beyond the challenges of today, but also well beyond, potentially, our own existence?” That’s not to say that buildings live forever. They don’t. Buildings, we like to refer to them as living things. And on average, buildings have a thirty-year lifespan. So they’re not permanent things. But thirty years is more than a lot of things. It’s more than a piece of furniture, often. It’s more than fashion, it’s more than things we purchase every day. Those are big, expensive investments in place. That means they take a lot of money, a lot of resources, and a lot of time to construct them. So we have to be very deferential to that time horizon, and live in that long time horizon, and be very patient with the decisions that we’re making that are going to affect folks a decade from now.

That’s really, I think, a privilege. It’s also the challenge. But it always, I think, forces us to ask questions about going back to first principles, going back to the human condition, going back to which things will consistently be shaping us and affecting us, whether there is a change in health care or a change in policy or climate change, for example. Things that we know are happening. How do we think fifty years down the line, and try to anticipate some of those changes?

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

MASS Design Group’s exhibition “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. (Photo: Matt Flynn. Courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

SB: Let’s discuss this specifically in the context of your new book, The Architecture of Health: Hospital Design and the Construction of Dignity, and this Cooper Hewitt, [Smithsonian Design Museum] exhibition, “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics” [which MASS curated and designed]. Time is such a fascinating subject to explore within health care and hospitals—like birth, death, illness. Could you speak to how you think about time in this context?

Murphy’s father restoring the family’s home in Poughkeepsie, New York. (Courtesy Michael Murphy)

MM: So much of what I’ve learned—and that’s what this book is really about, and to some degree, this show—I’ve learned everything about architecture by really thinking about the medical space of the hospital, to some degree. When I was in my first year of graduate school, my dad [Michael Murphy Sr.] was in remission from suffering from cancer. It’s a big part of my own journey, is coming home and working with him, when he got sick, on our family home. It’s what got me excited about architecture.

SB: You did a great TED talk on this.

MM: Yeah. I talk about that a little bit in my TED talk, about how he turned to me when we had finished restoring our old home and said that working on this house saved his life. He was in remission, and it was a powerful, transformative experience. Not just the mechanics of working on our home, this old 1896 home, which, if you talk about time, we were the fourth family that had lived in it and stewarded it. We were solving scars that had been made by families before, but restoring pieces of it. It was a beautiful thing to be a steward of that period of time.

SB: Home is a body, really.

Murphy’s childhood home in Poughkeepsie, New York. (Courtesy Michael Murphy)

MM: Yeah. I like that. It’s true. It’s a vessel that you’re able to inhabit for a while, and build your life around, and then, move on, in a way. And yet, it still has a deep spiritual connection to us.

When my father said [that] working on this home saved his life, it touched a deeper part of me in a way that was like…. You might say, “Oh, it didn’t really save his life.” But I think it actually did save his life. It gave him not just a thing to point towards in terms of hope. But he was fighting that cancer spiritually and physically, and this thing—along with great medical care—allowed him to survive for much longer than they anticipated. That being said, the cancer he had was virulent, and dangerous, and aggressive.

Then I went to architecture school inspired by this kind of spiritual dimension of the built environment, [but] found very little of it in my first studies, I would have to say. I was walking into my first final review—I’d been up for multiple days. Again, architectural labor is very intense. You’re on charette, they call it, and you never sleep, and you’re working on these models, and you’re just frenetically producing things.

Murphy’s father restoring the family’s home in Poughkeepsie, New York. (Courtesy Michael Murphy)

I walked out of my final review where I’d gotten butchered. Just like, torn apart, not a good review, which is very typical as well. I looked at my phone and there were like forty missed calls. And they were all from my mother. So I listen to the first one. My mother’s like, “Where are you? Please pick up.” The second one is, “Your dad is going into septic shock. We’re in an ambulance. We’re going to New York City”—we grew up about ninety miles north of New York City. The third one is…. I’m like, what’s the fortieth one? I collapsed, just slid down a wall, just sat on the floor, just afraid to listen to the rest of them.

Just at that moment, a friend of mine who knew my family, ran into the school, and was like, “I’ve come to find you. Your mother called me. Your father’s alive, but he’s in the hospital. He’s in New York. I’m taking you right now.” It was this amazing and horrifying moment of grounding. I’d been spending three days completely disconnected, focused on trying to stuff a Y.M.C.A. into a tiny parking lot in Brookline, Massachusetts, for this speculative initiative, which I’d gotten destroyed upon. Interesting, and somewhat not interesting. And in that period of time, I could have had this transformative existential change, which I would’ve missed. Fortunately, I didn’t, but it was scary, and I think, sobering.

Murphy’s childhood home in Poughkeepsie, New York. (Courtesy Michael Murphy)

We drove to New York almost immediately. And I came into this very—I won’t mention—famous and well-funded research institution of cancer care, one of the best in the world. And I was struck by its banality and the… lack of design. All those things that we had been learning about . How little design I could see, taste, feel, or experience, and just imagining my father passing away in this depressing institutional experience.

SB: Yeah.

MM: We went through the holidays there. In fact, actually, it was this week, December. It was December 6th, 2006, actually. We’re on the 7th [of December]. Today is the 7th?

SB: Yeah. Fifteen years.

MM: So fifteen years ago today was when that happened.

SB: Wow.

“Why does [architecture] fail so frequently to meet what is possible in that moment of great existential change?”

MM: I think it was the 6th or 7th. I remember walking out of that hospital with this seed planted in my head: If I ever design anything, it should be a hospital. So to go to your first question—we sidetracked all the way through these stories—is to say there was this other reckoning there, which was, this is a place of great transfer. This is where some of our greatest joys, which I’ve also experienced—our daughter was born eight weeks ago—and also some of our greatest fears and challenges, the loss of our loved ones. We have to go into this place, often, to experience that. What an incredible opportunity for design. And why does it fail so frequently to meet what is possible in that moment of great existential change? It’s a fascinating question, and one that I just can’t stop thinking about ever since then.

SB: My first memory ever, actually, is in a hospital. It was a month before my fourth birthday, and I had been in a crash, and I was playing with a red fire truck. And that’s my first memory. I remember the red fire truck. So it was an aesthetic experience, which is fascinating, that even at that age, the thing I grabbed onto was the beauty or the aesthetic, the thing, the object.

MM: Yeah. No, it is amazing. They are both invisible and very visible in our lives. Your fire truck story is a good one. I was thinking about what my father—what he was given. There was a moment where like, they brought in a care dog, wrapped in a bow and things. And you’re just like, “Please get this thing out of here.”

SB: [Laughs]

MM: They were trying to create joy and he was just not having it. He was thinking about his life, and how soon it would end. And we had a view of the East River, actually. And I think that was a really positive thing, of the experience, of the patient room, that there was this view that we could look out, and imagine something else while we were in that institutional space.

As I reflected back later and started to work on hospitals—I actually had the great experience—I had more of an ambivalent relationship to that. I returned to it thinking how lucky of us to be able to be given the space with some of the greatest doctors and greatest practitioners, who saved his life, physically. I talk about this in the [Architecture of Health] book a little bit, but I say, “It both served his body and his soul, but not often at the same time.” Sometimes it was serving the experience of being cared for, and sometimes he was a cog in the wheel of the institutional setting, where people were operating on him to save his life. And that binary, between serving the person—a whole person—and serving the public, that is the crux of what is at the heart of the hospital. But also at the crux, you might say—I would say—at the heart of architecture, because it serves two masters. It serves the individual, to great comfort and dignity, of feeling like we matter, and it has to serve this greater public order. That’s a really hard balance. Great architecture modulates between these two effectively, and poorly designed architecture does not. It makes us feel like we don’t belong. It makes us feel like we don’t matter, and sometimes, hurts the very places around us much more than it benefits them.

“Poorly designed architecture makes us feel like we don’t belong. It makes us feel like we don’t matter, and sometimes, hurts the very places around us much more than it benefits them.”

SB: In the book, you write, “Hospital architecture illustrates the contradiction inherent in nearly all public built spaces: the tension between an imagined population that will need public services—charity—and the systems’ overt need to shape that public’s behavior so its members may attain it—control.” So there’s this charity and control contradiction—contrast. Could you elaborate on that a little bit?

MM: One of the crucial arguments that we must accept if we move into this Slow Space movement—and [that] I think this historical lineage of architects, in thinking about social and environmental impact, would acknowledge—is that buildings shape our behavior. They shape what we do. There’s been some academic debate [about] whether that’s true or not, or whether we should accept that as true. But you talk to a nurse, or you talk to a medical professional, there is just no question, at all, that the way the space is designed is having a direct impact on their ability to work and their ability to perform care, which affects people’s lives.

“You talk to a medical professional, there is just no question, at all, that the way the space is designed is having a direct impact on their ability to work and their ability to perform care, which affects people’s lives.”

SB: There’s an amazing woman, Susan Magsamen, at Johns Hopkins University, who’s running a whole program around neuroaesthetics [called the International Arts + Mind Lab] that’s digging deep into this. I think it’s important work that is going to be more and more noticed in the next couple of decades.

MM: I think you’re absolutely right. There’s been theoretical resistance to diving deep into the questions of how buildings and spaces shape behavior. There’s been a lack of scholarship around it. We have many more ways to both measure, analyze, and capture—neurologically, physiologically—the ways in which spaces around us are shaping our health.

But as a statement of truth, I am not only persuaded. I think there is enough evidence around us to say, “Spaces shape behavior and shape our lives.” And after the pandemic, I think the world has woken up to this reality—everyone in the world—that the buildings we are in are keeping us from getting, at the bare minimum, fresh, uncontaminated air. That’s a powerful, transformational paradigm shift in the way we understand the built environment.

That has a piece of control in it. We have to almost give in to the idea that, when we walk into this room, we’re made vulnerable. You feel it every day when you take off the.… I felt it walking in here. Like, Do I take the mask off? Are we vaccinated? There’s a question there: Am I safe in here? That’s a very important moment of both hospitality and hostility. And we’re all experiencing that every day by where we enter and where we leave, and not fully knowing if we’ve been violently contaminated to some degree.

The inverse is also the piece of charity, which is, we have the capability to create those spaces of comfort, to clarify that this is a safe space, to make visible that you are safe in here. I use those terms both in a physiological sense, like, if the windows are open and we could visualize air flow to know that we’re getting enough air changes per hour, that contaminated air would not infect us, that’s one way. But we also can talk about that from a sense of lived experience, that we walk into a place and I recognize myself in it, that I don’t feel “othered” by it, that this is a place that belongs to me and belongs to us.

All of that conversation is emerging in a really productive way today. But at the core of it is the sense that it’s always modulating between the sense of charity and the sense of control. And hospitals deal with it every day. They’re forced to deal with it, because they can’t fully solve it all the time. And so we see, again, in hospitals, a theoretical kernel of all public spaces, [which] are challenged by this same categorization of protection and violence, to some degree.

SB: MASS runs what’s called a Restorative Justice Design Lab. This is a means to design decarceration and invest in restorative justice. In the U.S. alone, there are 2.3 million people incarcerated in more than 1,800 correctional facilities. Those are numbers that are staggering. I just don’t think people think about them every day. It’s an incredible scale. I imagine this project and lab has required spending a lot of time with inmates who are “doing time.” What has your time in prisons, or working with the team on this project, working with correctional facilities, taught you? What does this lab’s work entail? How are you thinking about time in relation to the whole thing?

MM: Maybe I can explain what we mean by “lab,” and then go into a little bit of the work in there, and then talk about some amazing folks we’ve been able to work with who have really changed the way I understand the built environment.

SB: And I am asking this in a very nuanced way. I want to stress that. Like this is—

MM: Yeah. That’s cool.

SB: There are, I think, a lot of misunderstandings around prison reform. And I think that there’s a lot that can be done in that space, and needs to be talked about in a way that’s productive.

MM: There’s no greater crisis, especially in America, than the situation of our carceral state. I think Bryan Stevenson said it right when he says [that] from slavery to mass incarceration, it is a continuity of our history of racial injustice and racial violence.

The question of, “Why work in prisons?” or “Why think about prisons at all?” as something to work on, again, goes back to two foundational realizations. One, if the buildings around us are causing injury or healing, which ones are doing it the most, and how do we both understand them, as well as try to cut them out at the root and try to address them directly?

“We can’t actually think about the future of architecture without thinking about prisons.”

As architects, the state of carceral facilities in our country—but also, it’s being perpetuated globally—is indicative of a negligence that we as a profession have failed to acknowledge and address. I think that just is the truth. We can’t actually think about the future of architecture without thinking about prisons. Because prisons are so offensive, and terrifying, and structurally violent, racist, and horrific—in our nation, in particular—I think, to some degree, the only response has been no response, like, to do nothing. To not engage at all. In fact, some would argue that engaging in any way with the design of prisons is itself an act of complicity and violence. There’s very, very valid arguments there to be made, especially in the United States. That argument abroad, in Germany or Norway, or in other places that have thought critically about at this, about carceral spaces and how they might be redesigned to address—

SB: Sarah Williams Goldhagen has written beautifully about this in her book Welcome to Your World, which is an encapsulation of a lot of what we’re talking about.

MM: Totally. Yeah. So I think this is a particular American thing, although there’s other places in the world that are replicating what we’re doing in America. Baz Dreisinger is writing about this and her Incarceration Nations Network, and doing incredible work.

All that is to say, it is fundamentally a built-environment problem. There is an architectural component of the carceral state, which is, you cannot detangle it from the issue of prison. And once again, Covid just reveals that. Where is it that Covid was the worst in the first outbreaks? Prisons. Nursing homes and prisons. It shouldn’t surprise us that we are talking about the architecture of where these people are contained, and where these outbreaks emerged. They’re unsafe, quite literally, physically [and] physiologically.

SB: And one of the worst offenders is right here in New York City: Rikers.

MM: Completely. It’s a very knotty issue, but it needs to be addressed. I think not addressing it is something that’s a crisis. As a nonprofit organization, one of the questions is, What can we work on, and what should we work on? It’s pretty evident that you have to be working on the condition of a carceral state, and the condition of the architectural prisons, in order to really understand where there is possibility.

Without designing new prisons, which is a very complicated place to stand, we could be in service of those that are directly affected by the system. And so we’ve been working with advocates, allies, small nonprofits that have been working inside of facilities with residents, and trying to ask them how they would redesign their spaces of containment. Baz Dreisinger is one of our partners. I speak with her, and it’s been amazing to see how she sees it. The most recent partner we’ve been working with is the amazing [Reginald] Dwayne Betts, who’s just—

SB: Incredible.

“Can we imagine an active project where we’re both serving the daily needs of people who are suffering in that system, as well as seeking to break our country’s reliance on the dominance of that system in order to survive?”

MM: Incredible, inspiring, visionary thinker, advocate, of course, himself, incarcerated in his youth. [Went] on to get a Ph.D. at Yale, [a] law degree, recently won the MacArthur “Genius” award, poet. Just the most amazing guy. His project is this thing called the Freedom Reads project. That liberation comes from access to literature, to books, to knowledge, and he wants to put libraries in every prison in America.

We have this discussion a lot: Is it right to put them in, or should we just not work at all within the system? And he goes like, “People are living every day within the space of torture.” To leave them behind for ideals that we may get closer to, but to leave them behind in the process, is itself an unethical act, or an act of negligence. So we should do both. The conditions of confinement are horrifying. They are literally torture, and people are suffering in them every day. Can we imagine an active project where we’re both serving the daily needs of people who are suffering in that system, as well as seeking to break our country’s reliance on the dominance of that system in order to survive?

Cover of American Prison: A Reporter's Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment (2018) by Shane Bauer. (Courtesy Penguin Press)

Some things emerge when you ask that question of service again, which is that you think about the prison as a place and, suddenly—if you’re focused on human dignity, like the dignity of the individuals that have to suffer through that—that it’s not just the residents who are incarcerated, whose lives are affected every day. It’s also the correctional officers, the C.O.s, the staff. These folks live in a work environment which is insufferable, which literally is making them crazy. There are so many examples of folks—we’ve talked with a lot of these folks and worked with them—where the space itself is so anxiety-driving, so threatening, that it makes them violent. It makes them terrified. It puts them on the defense. It puts them into a position of aggression. They’re self-medicating. They’re paid terribly. Their turnover rate is so high, the burnout rate is so high, that they’re constantly churning through new folks, many of whom cycle through the prison themselves.

A good example of this would be Shane Bauer’s stunning work American Prison, where he, as an investigative journalist, went undercover as a prison guard in [Winnfield], Louisiana, into a private prison. The experience of someone making barely minimum wage, the people he worked with, the residents that he dealt with every day and oversaw, that kind of threat of violence in his own mind, how he transformed as an individual, is a brilliant and shocking exploration of the American psyche. And it’s spatially determined.

We are, as professionals of the built environment, required to deeply consider the conditions of power that we are complicit in when we build things, and the prison reveals that. So that’s the control piece. But we’re also responsible to consider how the spaces we design shape the possibility of dignity in the individual. That’s the charity piece. The hospital and the prison are the two clearest examples of where design—the architecture of space—is intended to have some outcome by the individuals it’s serving or containing or protecting. That’s why this book is really digging deep into those as typologies that we need to explore and understand in order to understand the world around us and ask bigger questions about it.

“[Architects] are also responsible to consider how the spaces we design shape the possibility of dignity in the individual.”

SB: Another area MASS spends a lot of time working on is memorials. You’ve designed the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, with and for Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative. And you’re currently working on a memorial [called “The Embrace”] celebrating and honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Coretta Scott King in the Boston Common. These are projects—or portals, really—designed for people to spend time in and respond to, and at their best, I think they really allow people to come away feeling changed, somehow. How do you think about and process time in this memorial context?

A rendering of MASS Design Group’s memorial “The Embrace” in collaboration with Hank Willis Thomas, which depicts an embrace between Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MM: The really successful memorials, in my mind, are those that demand something of us, and that force us to contribute and participate in the making and remaking of the memorial itself. That’s a little abstract, but I can be very specific. When we started our work in East Africa and Rwanda, a lot of our colleagues, friends, partners are themselves survivors, or family members of survivors, of the genocide against the Tutsis in 1994. When we were asked to design an addition to the national memorial, we worked very closely in partnership with survivor groups and our own team to ask, “What should and can this memorial landscape do to advance healing in one of the most horrific atrocities ever perpetrated on mankind?” The Rwandan genocide was just absolutely indescribably terrifying.

SB: And on a continent that’s really lacking in memorials for various reasons—cultural, social, financial. Compared to our obsession with memorials in the West, particularly in America, there are far fewer in Africa.

“The really successful memorials, in my mind, are those that demand something of us, and that force us to contribute and participate in the making and remaking of the memorial itself.”

MM: I think there’s pieces of that that are definitely true. Although, I would say, at least with the Equal Justice Initiative’s aspirations, Bryan would often say, “South Africa, Rwanda, Germany—places that have suffered through incredible atrocities—have spent enormous amounts of resources on their memorial landscape.” South Africa certainly has. And I would say in Rwanda, you’ll see genocide memorials in nearly every community. Most of them put up small plaques or statues, reinterred public graves put up by survivor groups.The Memorial landscape is vast, actually.

SB: It’s just different in the sense that it’s not heavily financed the way it is here in America.

A rendering of MASS Design Group’s planned addition to the Kigali Genocide Memorial. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MM: That’s true. It’s incrementally financed. There’s a national [Kigali Genocide] Memorial there.

One of the things that really transformed the way I understand what memorialization might be, as an act—as a living act, as a ritualized act—is that, every year, during Genocide Remembrance Week in the first week of April, the public comes to the national memorial, and for many years, would bring remains of people that were found throughout the year to the national memorial to add them to the open grave that sits beneath the museum.

SB: Wow.

MM: A completely transformative, sobering, and powerful experience to watch, and also recognize, that that annual, ritualized, active remembrance is also part of their reconstruction of their country in so many powerful ways. It taught me that the museum itself is really the location of these—it’s a place for information, but it’s really a location for ritualized acts that need to be necessary to reconstitute the kind of future they’re interested in constructing.

When I thought about the other memorials that we loved—I know you’ve done incredible work on this, and we’ve talked about this, and thank you for the brilliant book [In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials]—I obviously think about Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial. And the thing that I think about there—beautiful, of course, a stunning project, transformational in terms of how we think about the memorial landscape, but it was always the rubbing that really made me think differently. That people would go—

SB: Touch.

MM: Hunt for the name, touch it, and leave with something. There’s something in that act of tactile memory that you engage [with] directly. You’re not just passively walking through it. You’re not just walking past it. You’re looking for something; you’re on a hunt, you’re searching, and then you’re engaging it tactically, and you’re pulling something away, and you’re leaving with a remnant. That is a multi-stage act—a procession, if you will—a way in which the location ingrains itself in you, as an individual, to create what I would call “deep memory.” You don’t forget that, because you’ve engaged with it in multiple ways: emotionally, mentally, but also tactically.

When we were asked by the amazing Bryan Stevenson, his amazing team, to help think about the memorial [for the Boston Common], we went back to both his writings and teachings about what transformation is. What is the goal here? The goal is to achieve something closer to racial justice, closer to a society that isn’t reliant on systems of white supremacy and domination, and to go through something individually. To go through a form of transformation.

We designed the memorial very specifically around what we would call these five stages of transformation that he talks about, [which] are consistent with some of these things that we’ve seen internationally, but [have] particular characteristics that Bryan brilliantly theorizes. It’s the procession through, the time it takes to journey through this location, that we think is what starts to sink these ideas deeper into us, and force us to be engaged instead of just a passive agent walking past, or saying, “I was there,” but not really participating in being there.

SB: It’s bodily, that experience of walking, particularly I’m talking about the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. When I walked out of that memorial, I had to sit down on a bench for probably thirty minutes and recover. It was not recovery in the sense of feeling totally traumatized. It is a very harrowing memorial to walk through, but it’s also, at the same time, uplifting. There’s a lot of sense of hope: the water feature, the park-like break in the middle. And yet I think, just to process that properly, what you walk through, what you experience, requires the time to sit. So I was glad there were some benches right outside. [Laughs]

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by MASS Design Group in 2018. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MM: I love hearing your reflection on that experience.

We talk about five stages of transformation, and we try to design the physical vignettes that respond to those specific transformational moments. Those five stages are: identity matters; that we must feel discomfort, number two. The third is that we must change narratives, historical or contemporary narratives, to be more truthful. The fourth is, we must get proximate. We must get proximate to place in our communities, because they know how to answer the questions that we may not even know how to ask. And fifth, we have to remain hopeful. Hopelessness is the enemy of justice, he often talks about.

At the end of the memorial, we have a moment where we aspire to, or at least hope, that folks feel a sense of that empowerment, and also some ability that they, too, can be a part of that transformational change. When you climb up the center, we thought a lot about those images of lynchings in the public square, where ten thousand people—there’s an image from Paris, Texas, where ten thousand people came out to see this horrific killing, bringing their family members, traumatizing children. They built this structure for everyone to see, and they would lift it up above, in that public spectacle. We thought a lot about that and wanted to invert that, that when you were on the top of the hill, you were looking out over the city of Montgomery, and you were in judgment of the dead, instead of the inverse—that you were being judged on your own participation in the system and resistance against it.

SB: And the only way of actually experiencing the city is to look through these pillars.

MM: That’s right.

SB: Eight hundred of which are hanging, and as you walk through this procession, your neck begins to crane up, and you realize: You are the observer, and then, in the middle, you’re being observed.

“It is incumbent upon [architects] to leave tools that others can develop on their own to address very complex and challenging issues locally.”

MM: That’s right. It’s amazing you had that experience, because it’s not didactic. We’re not telling you how to experience that. You have to feel that, and be able to process that through that journey. So it’s exciting to know that you had some of that experience.

SB: I think every American should visit this memorial. I think it would completely change this country.

MM: Wow. That’s quite a…. Thanks for saying that.

One of the things I’ll just add on the end, though: One of the lessons that we learned from Rwanda, in particular, is that people are desperate to come, but they’re also desperate to participate. And they don’t know how to participate. And it is actually, I think, incumbent upon us to leave tools that others can develop on their own to address these very complex and challenging issues locally.

“People are desperate to come [to memorials], but they’re also desperate to participate, and they don’t know how to participate.”

So, outside, there are these markers that can be moved to your home community if you claim them through a series of acts of collective engagement. There’s a sense of vulnerability. I don’t know how it will end, how many will be moved, if any will be moved, how many people will claim them, what it will look like in the future. But that radically vulnerable position of a living thing, I think it’s also part of the architecture being open to its own amendment over time, but grounded in, let’s say, the essential principles that it wants to continually reproduce and ritualize through its experiential journey.

SB: I did want to also mention the Gun Violence Memorial Project. This is an ongoing effort that MASS has been working on with the violence-prevention organizations Purpose Over Pain and Everytown for Gun Safety. It was first shown [during] the Chicago Architecture Biennial in 2019, and [now is] on view at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., as part of the “Justice is Beauty: [The Work of MASS Design Group]” exhibition. What has it been like working on this project? Could you share your vision for it, what you’ve learned? It seems like it’s set to be this long-view memorial in many ways, like ongoing, something that could one day become much more of a permanent fixture in the nation’s psyche.

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

The “Justice is Beauty: The Work of MASS Design Group” exhibition at the National Building Museum. (Photo: Elman Studio. Courtesy National Building Museum)

MM: The Gun Violence Memorial is something that I think, if successful, will live for decades, and continually be constantly changing. Because the epidemic that we’re in is changing every day, and is not ending. It’s getting worse. This kind of memorial has a different time horizon than one which is looking at past events that are encapsulated and framed by a period of time. The challenge in the lynching memorial is to communicate and narrate how these historical events are present in today’s contemporary landscape—hence the linking to mass incarceration and other acts of racial terror. But I think that was the historical challenge, to bring it to why it’s relevant today.

Where the Gun Violence Memorial is so relevant today, the challenge is a slightly different one, which is to…. Everybody has an opinion about it. So it’s to depolarize our position on the very complex and polarizing debate around guns in America, and try to shake the bias that we have around this debate, and bring you into a memorial to see these individuals, all of them who have died from gun deaths in America as individuals, as human beings, who have a life, and whose human dignity matters, and that has been lost in the debate itself.

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

MASS Design Group’s Gun Violence Memorial Project in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy MASS Design Group)

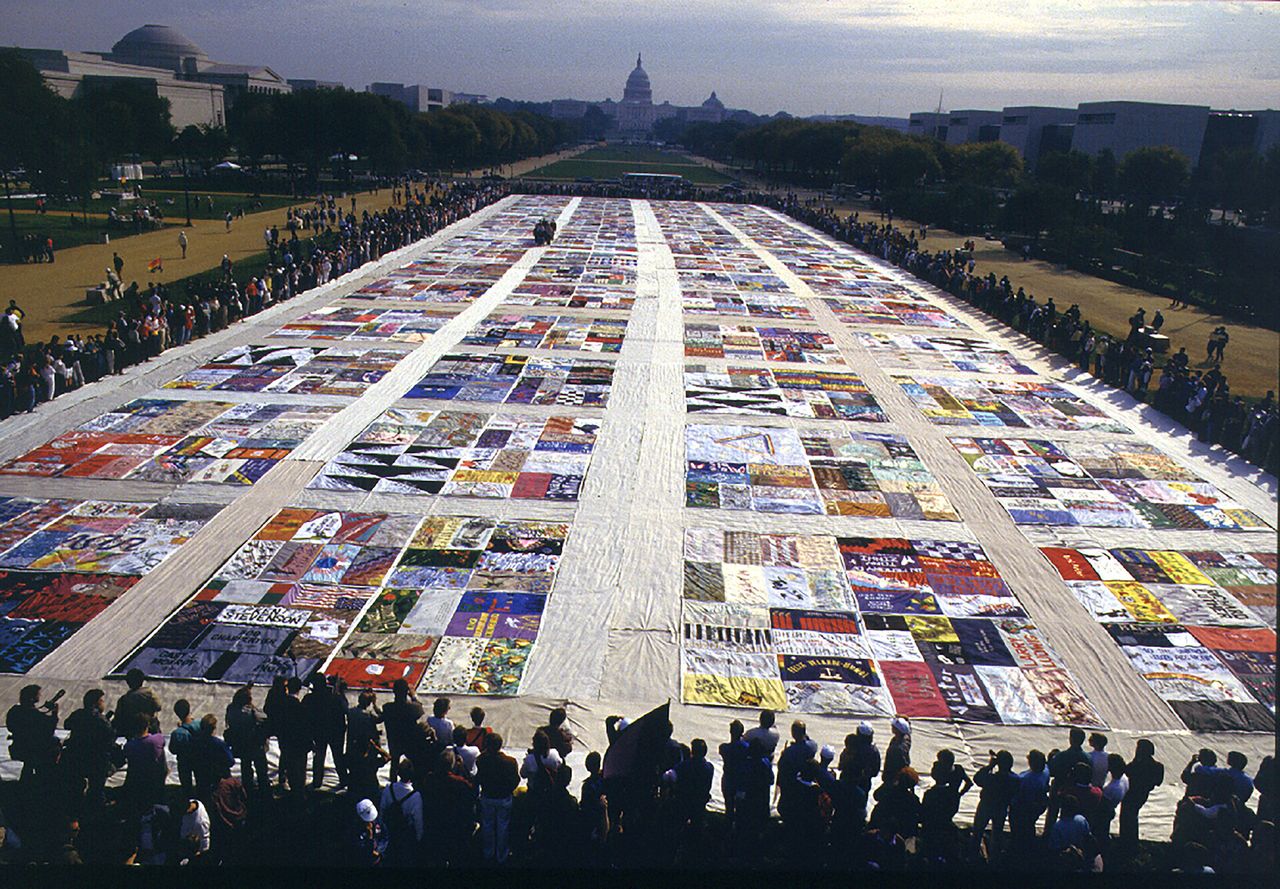

The AIDS Memorial Quilt, first displayed in 1987 on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy National AIDS Memorial)

Operationally, what that memorial looks like is something very different. The best example, and what we pay homage to, is the AIDS Memorial Quilt, the NAMES Project, which, as many of us know, is just one of the greatest memorials ever, and is also ongoing. It’s a living thing, and it was a simple participatory request: Create a panel of a consistent size, and do with it what you will to honor and recognize your family members who have died of the epidemic of AIDS. In 1988, ’89, at that period of time, the debate was one that was being…. There was resistance at the government level of acknowledging the disease, of advancing policy, of naming it, fighting for, especially, the L.G.B.T. community that was dying of it, in particular. But of course, many others were as well.

This gave names to the disease. It gave names to these individuals. It elevated their dignity, and through stories, touched the human condition. And when placed on the National Mall, covered the National Mall, becomes the biggest memorial in the country, and then is immediately able to be removed, packed up, and moved somewhere else, and made powerful.

In that project, we really learned, in thinking about it, a kind of theory of what memorials must do. My colleague Jha D Amazi, who leads our memorial work, theorized it well to me. She said, Memorials must touch. They must touch the intimate and the infinite both. They must modulate between the sense of the overwhelming, uncountable, unquantifiable mass of this topic, this issue, the infinitely huge sense of horror, and trauma, and pain that so many events in our world have projected on communities and made communities suffer. And yet, we must have a way in to talk, to see the individual as a human being, and connect with them as an individual human being. And that’s the intimate.

Modulating between those two things, always going back and forth, I think is the role of spatializing loss. Because we can’t do that, necessarily, very easily on a digital screen. There are some graphic experiments that have been done, and some good graphic design that has tried to do that powerfully. But it’s really hard to really feel that, and that’s why so many of these names just become numbers.

Pam Bosley and Annette Nance-Holt, who are the co-founders of Purpose Over Pain, approached me at the opening of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in 2018 in April, and said, “We need a memorial to our children who died of gun violence.” They told me about their sons who were killed on the streets of Chicago. They said, “Our sons have become numbers. Their lives, their identities, their stories, have been lost in this debate, and we need to reclaim them.” Terrell Bosley was Pam’s son, and he was killed outside. He was just going to church band practice. Just horrifying. And Blair, [Nance-Holt’s] son, was going to a job [in] downtown Chicago on a city bus, a C.T.A. bus, and somebody came on the bus and just shot up the bus.

These are two stories of thousands, hundreds of…. We have [more than] a hundred people killed a day in America.

SB: There was a school shooting last week.

MM: School shooting last week. And [the] indifference, or like, the sense of inability to know what to do, has created this casing around all of us of our inability to act, and a lack of commitment to searching for those stories that would transform us all.

So I was very touched. I had another one of those moments where I just started to like, collapse and weep, just hearing those stories. It just changed me. And I said, “Okay, we have to do something.” I was sitting next to my friend and collaborator, Hank Willis Thomas—

Hank Willis Thomas’s installation “Raise Up” at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. (Photo: Spencer Bailey)

SB: Whom you’re working with on the Boston memorial, and collaborated with on the Gun Violence Memorial, and actually had an installation at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice?

MM: Yeah, that’s right. It’s the last part of the public park of the memorial in Alabama. I was sitting next to him, and I told this story about meeting these women. He said, “You know, my cousin was killed in the streets. It’s [who] my company’s named after, Songha. I think about him every day.” So we agreed [at] that moment to do this thing.

We developed this memorial for the Chicago [Architecture] Biennial, and the idea is very simple, much like the AIDS quilt. It’s only made real if people contribute and participate. We imagined a glass house, where there’d be seven hundred glass bricks, or spaces for glass bricks. Seven hundred people killed a week; one house a week. And we would ask family members to contribute a personal object or memento to fit into that brick space, to help construct that house.

The Brick-a-day Church (also known as the First Baptist Church) in Montgomery, Alabama. (Courtesy Alabama African American Civil Rights Heritage Sites Consortium)

There’s an analogue to this. In Montgomery, actually, Ralph Abernathy, the great minister and partner to [Dr. Martin Luther] King, [Jr.], his church, which he preached at, they called it the Brick-a-Day church, because the congregants would bring a brick. Each brought a brick to construct this place of community and spiritual deliverance. That idea of each individual bringing a stone or a brick is an old, cross-cultural idea about constructing community and constructing place. You think about barn-raising in the Amish tradition, or you think about the mosques of Mali, where the re-mudding every year is a ritualized effort to reclaim and rebuild the things that are important to us. There is such a powerful and transcendent notion that we take care of the things we love. And each one brings one. That idea that we all bring a story, and we all bring something to these things that we then need, or rely on, to survive.

The house, obviously, [is a] domestic form that has a lot of symbolic and spiritual dimensions. It’s a place of comfort, safety. It’s also the place of nightmares. It’s the place of domestic violence, and the hatred around the dinner table, the things we won’t say in public, it’s the place of care, protection, and fear, and survival. And it’s like the most original piece of architecture. It’s our homes. It’s what matters to us and what we base our identities upon.

So that house, and the bricks that make it, being made up of stories, of individuals that lost their lives, for us, as a punctum, a way in to try to ask this deeper question of, How do we survive this thing, this epidemic? How did we let it fester? How can we let it fester any longer? The goal is to build a house for every state—fifty-two houses, one for every state in the United States, plus D.C. and territories, to have fifty-two, one for every week, and put them on the National Mall, and collect objects from all over the country, to build, like the AIDS quilt, a kind of national movement and march, that is a cultural project, which is bringing us all together to not forget those names.

SB: Before we finish, I did want to mention, I found it interesting when researching you to learn that you were exploring becoming a journalist before becoming an architect. And in fact, you were working on a story in South Africa [as a freelance writer] when you first found out your father was sick with cancer. In your life story, where does storytelling come into this? Because it seems to me, and there are predecessors in architecture who have—Rem Koolhaas, perhaps being one of the foremost, in terms of being a journalist and then becoming an architect. How do you see this junction between a journalistic approach, or reportorial approach, where you’re going out, you’re collecting the data, you’re finding the stories, you’re talking to the people. Where does that intersect with the work that you do as an architect? It seems to me that it’s very important within MASS’s practice, and within what you do on an individual level.

“Architecture is a narrative vessel.”

MM: I’ve become persuaded that architecture is a narrative vessel. It is a storytelling device. It tells the story of place. As we were just talking about, each one of these bricks is itself a story. Each one of these human handprints, we talk about—not just the environmental footprint, the human handprint. Each one of the stones of the [Butaro District] Hospital we built in Rwanda was crafted by an individual, who cut it to fit perfectly into place. When we drill deep into provenance, we find human—not just labor as it’s fetishized—but the human act of constructing things together, in tandem with each other, to build the things that matter.

The Butaro District Hospital in the Burera District of Rwanda, designed by MASS Design Group in 2011. (Photo: Iwana Baan. Courtesy MASS Design Group)

The doctors’ housing at the Butaro District Hospital in Rwanda, designed by MASS Design Group in 2011. (Photo: Iwan Baan. Courtesy MASS Design Group)

That Brick-a-Day church is really powerful because we’ve seen it happen in other forms. I saw it directly when I worked in the house with my father. That experience will never leave me. It’s actually been the fuel which has given me purpose in my life. It was just forgetting everything else, and just trying to restore the house and with care, attention to detail, and intimacy that would be viewed by very few people, but actually was deeply meaningful for me. Working together—less like what [would] result in something we care about, but it was really the working and partnership, often without saying anything—that, I think, really made me prepared for when he ultimately did pass away. That experience itself was a gift to allow me to live unburdened by his loss.

I think about it now with my son, who’s twenty-one months, born at the beginning of the pandemic, and now my daughter, born at the mid-pandemic. What do we want to leave behind? What’s the legacy that we have? It is the things we make together, that take care of us, that seem to be the most profound. I think I would end with those statements, that the things around us have this other spiritual dimension. They heal us in lots of different ways, and challenge us in lots of different ways.

“It is the things we make together, that take care of us, that seem to be the most profound.”

But yes, I agree with storytelling as something that has been informative to me. I was a literature major. I thought I wanted to be a journalist. I’m not a very good journalist. I’m not as good as you, Spencer. I can’t ask good questions. I was so interested in, and changed and challenged by, learning the stories of places and communities.

When I was working in South Africa, I was trying to write about—actually, I ended up writing about the architecture. I was writing about the proliferation of security infrastructure, razor wire and fences that were emerging after the end of apartheid. Suddenly, the fake open society, which was of course gated, racially gated. Then, when it was opened as a society, gates emerged everywhere around all the houses, and some residents had…. At some point you had to put up gates, because if you didn’t, you would definitely get broken into. But some residents were trying to aestheticize the fence infrastructure, in a way to modulate through design to try to deal with the offensive defensiveness of the fence.

“The things around us have this other spiritual dimension. They heal us in lots of different ways, and challenge us in lots of different ways.”

SB: Makes you think of Trump’s wall.

MM: Exactly. And trying to actually modulate that intersection in a way that says, “We still respect you as a public, but we’re also protecting the home.”

There was a fence that was developed with customized steel work that was of baobab trees and these things that I found really beautiful, and an attempt to try to wrestle with the reality of the everyday, while also trying to, through aesthetics and through design, manage that interface, that threshold between love, trust, respect, and security.

For me, buildings, the ones we love, tell stories. They tell stories about who we are and who we want to be, and what we believe in as a community. They don’t tell stories about a single author and what he believes that frequently. If we care about them, we protect them. Shigeru Ban said that: “We take care of the things we love.” I thought that was a great quote from him.

The last piece of this is, I’ve been really informed and I think, convinced, by the amazing Marshall Ganz, who is an organizer. I don’t know if you know his work at the [Harvard] Kennedy School. He was with Cesar Chavez in the sixties, he was in Mississippi in the civil rights movement, and came as a social organizer to persuade folks that it’s the stories that move us to political and social change. He talks about how every great story is driven by the narrative of self, us, and now. Why this matters to us, why it matters that I am here as an individual, my story, and why it matters now. And if we can tell a story of self, story of us, tell it now, we can move the needle in social change.

And buildings—great buildings—do that. But we’ve lost our way a little bit. I think we’re really good as architects at telling the story of self, this auteur story. We’re great at telling the story of now, like the flashiest newest thing is really the most beautiful, and that’s why you should like us. But I think we’ve stumbled on how to tell the story of us. At least that’s what we’re trying to do at our organization. But I think increasingly, designers around us are trying to develop the story of us, which tells a story of community, tells a story of purpose, in a way that—you can see it. You can look at it and say, “It’s ours. That’s ours. We deserve it. That’s the church. I brought a brick to it. It’s mine. I feel at home in it.”

When we go back to the Gun Violence Memorial—just last week, Pam and Annette came down to Washington, D.C., to see it, and we’ve been adding… We put in seven hundred new objects [that have] been collected over the last couple months, and Pam was talking about it as her house. “Where’s my house? Where’s Terrell? That’s my house. It’s my house.” That sense of ownership, because we contributed, and [that] we have something that is left here, I think, carries on.

It’s how I feel about my house in Poughkeepsie, New York. It will always be my house, even though somebody else owns it now. But I think it’s how we feel about the places that we’re from. It’s how we feel about the places we inhabit. It’s stories that matter for us to understand the built world around us. If they don’t tell a story, we don’t really understand why they matter.

SB: Michael, thank you so much for coming in today. This is great.

MM: Thanks. I appreciate it.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on December 7, 2021. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity by our executive editor, Tiffany Jow. The episode was produced by our assistant editor, Emily Jiang; managing director, Mike Lala; and sound engineers Pat McCusker and Johnny Simon.