Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

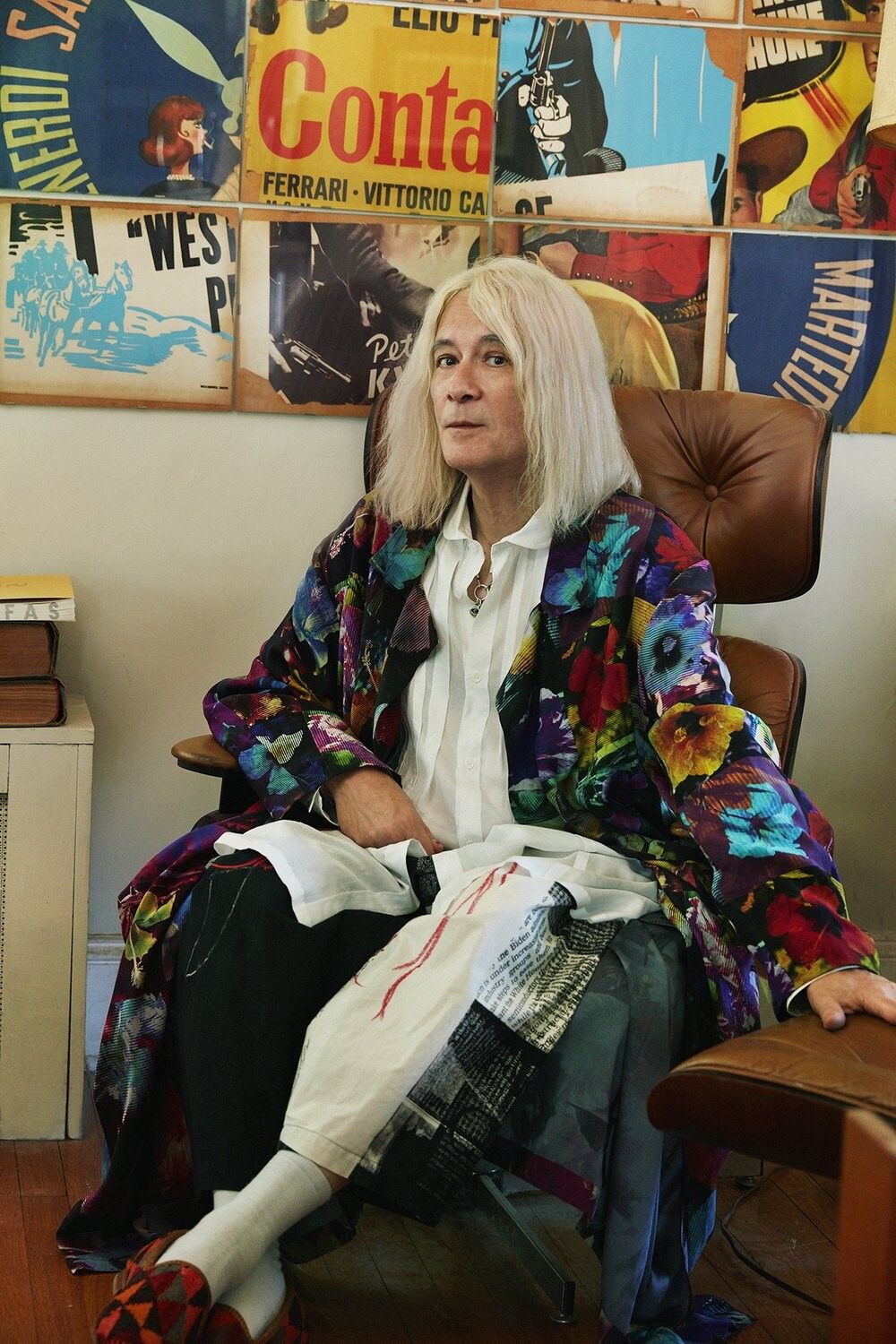

Lucy Sante. (Photo: Guzman)

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Lucy. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

LUCY SANTE: Hi. Thanks for having me.

SB: Before we get into I Heard Her Call My Name, your beautiful new memoir about your transition, I wanted to open up with your earlier memoir from 1998, The Factory of Facts. In it, you describe your childhood self at a curious remove, writing, “If the boy thought the phrase ‘I am a boy,’ he would picture Dick or Zeke from the schoolbooks, or maybe his friends Mike or Joe. The word ‘boy’ could not refer to him; he is un garçon. You may think this is trivial, that ‘garçon’ simply means ‘boy,’ but that is missing the point.” And elsewhere in the book you write, “I suppose I am never completely present in any given moment, since different aspects of myself are contained in different rooms of language, and a complicated apparatus of airlocks prevents the doors from being flung open all at once.”

LS: Wow. I forgot. I mean, I haven’t read that book in thirty years, or, well, twenty-five years. Huh. Of course, that makes complete sense, because at one and the same time, those statements are both true and a dodge, because I knew damn well there was a whole other part of me that I was concealing for other reasons, but also that there’s this weird rhyme between the dislocation between languages and cultures and nationalities—and genders.

SB: Yeah. And it wasn’t lost on me that, in the email you sent to around thirty friends, which you open up your new memoir with—you sent this between February 28th and March 1st, 2021—announcing your transition, or your intent to transition anyway. And you write in it that the “dam burst.”

LS: Mmm.

SB: In other words, you finally flung open all the doors at once.

LS: Right. Exactly. Yeah, that’s exactly what happened.

SB: [Laughs]

“I knew damn well there was a whole other part of me that I was concealing.”

LS: I could not have foreseen the degree…. I really did not allow myself to imagine transitioning before. Even if I very gingerly touched it, the surface, I still could not imagine all the waves, the repercussions, all the doors to have been flung open. You know, it’s not just like one or two, but many.

SB: Yeah. And I love that you just used the word waves. This is something I noticed because—and I think I have to mention your 2022 book here—I know we’re dropping a lot of books [laughs], but you’ve written a lot of books, Nineteen Reservoirs. That’s a book that tells the backstory of these reservoirs that supply New York City with its 1.1 billion gallons of fresh water each day. And you wrote this book just before you wrote I Heard Her Call My Name. I wanted to ask if you see a connection between the two books. They’re vastly different, of course, but what lines between them do you see, if any?

LS: Well, just very, very simply, I wrote that book for a number of reasons, but the big one is that it’s about where I live. And I’ve written about all the other places where I’ve lived, in Low Life, which is about New York City, in The Factory of Facts about Belgium, and, well, I could say the other is Paris, although I’ve been going there, like, all my life, and yet I’ve never actually lived there for more than a few months at a time. But it’s still a place that’s very close to my heart.

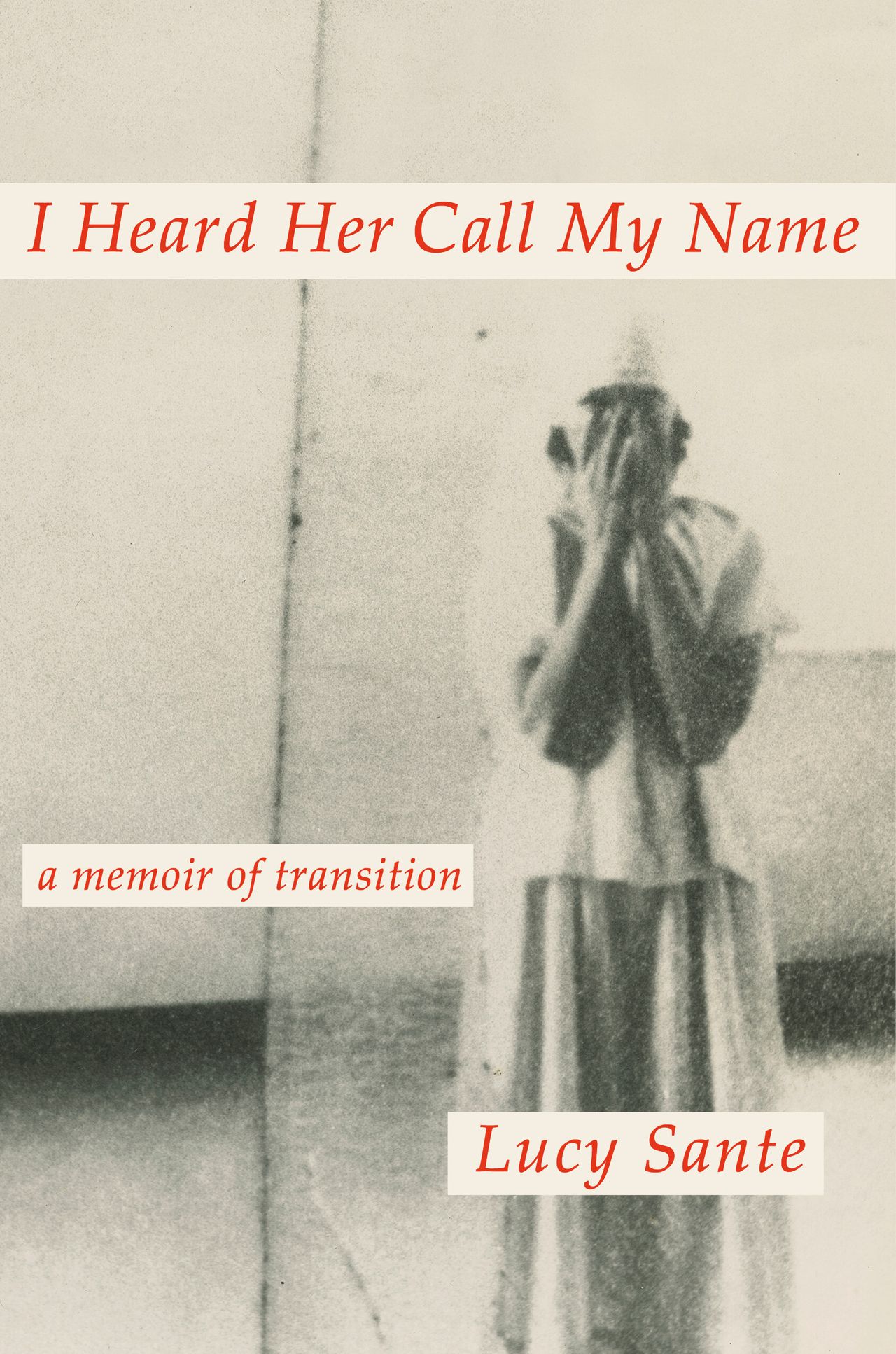

Cover of I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition (2024) by Lucy Sante. (Courtesy Penguin Random House)

So, Nineteen Reservoirs, it’s about where I live, and it also affects…. It’s an attempt to explain the division between what you might call “red” and “blue” up there, too, because I think the blue side has a lot of self-examining to do in the light of that colonization that New York City dominated over its… these counties that are ninety miles away and that have no contingent points, that New York City treated like colonies. And people today still feel that division very strongly.

SB: Yeah, and this sort of, not to push the metaphor too far, but there is this division of self, this division of trying to think about that, and in I Heard Her Call My Name, you use all these descriptive words that have to do with water, which I found a kind of curious thing. Maybe appropriately, too, having to do with fluidity. But in addition to the dam-bursting description I mentioned earlier, you also use in that email to your friends the words and phrases “liquefy,” “under water,” “liquid,” “quivering mass,” and “ripples.” [Laughter]

LS: Okay. So what’s your interpretation here?

SB: I’m not sure, but I was wondering if that was intentional.

LS: No.

SB: [Laughs]

LS: No, I just, I do not keep a tally sheet for my metaphors.

SB: [Laughs] Age plays an important role, of course.

LS: Well, yeah.

SB: And we have to talk about that if we’re talking also about time. You’ve noted a “great gulf” that separates you from your youth and this regret you have about your lost girlhood. How you yearn hopelessly for it.

LS: Mm-hmm.

SB: Could you talk about this lost time? How do you think about those sixty years of holding that secret?

LS: Well, that’s what the book is about.

SB: [Laughs]

“I really did not allow myself to imagine transitioning before. Even if I very gingerly touched the surface, I still could not imagine all the waves, the repercussions.”

LS: The thing about it is, the way it got started was through this phone app, which used—what I didn’t even know at the time—just think of it as an app that uses A.I. to transform your face. You can be fat or thin or blond or redhead. But I wanted the gender-swapping feature, and so I put it in that first picture. Blew my mind. My very next action was to start feeding through every picture I could find of myself, which took about ten days to round them all up. And wow, it was…. It gave me that vision. This was my alternate life.

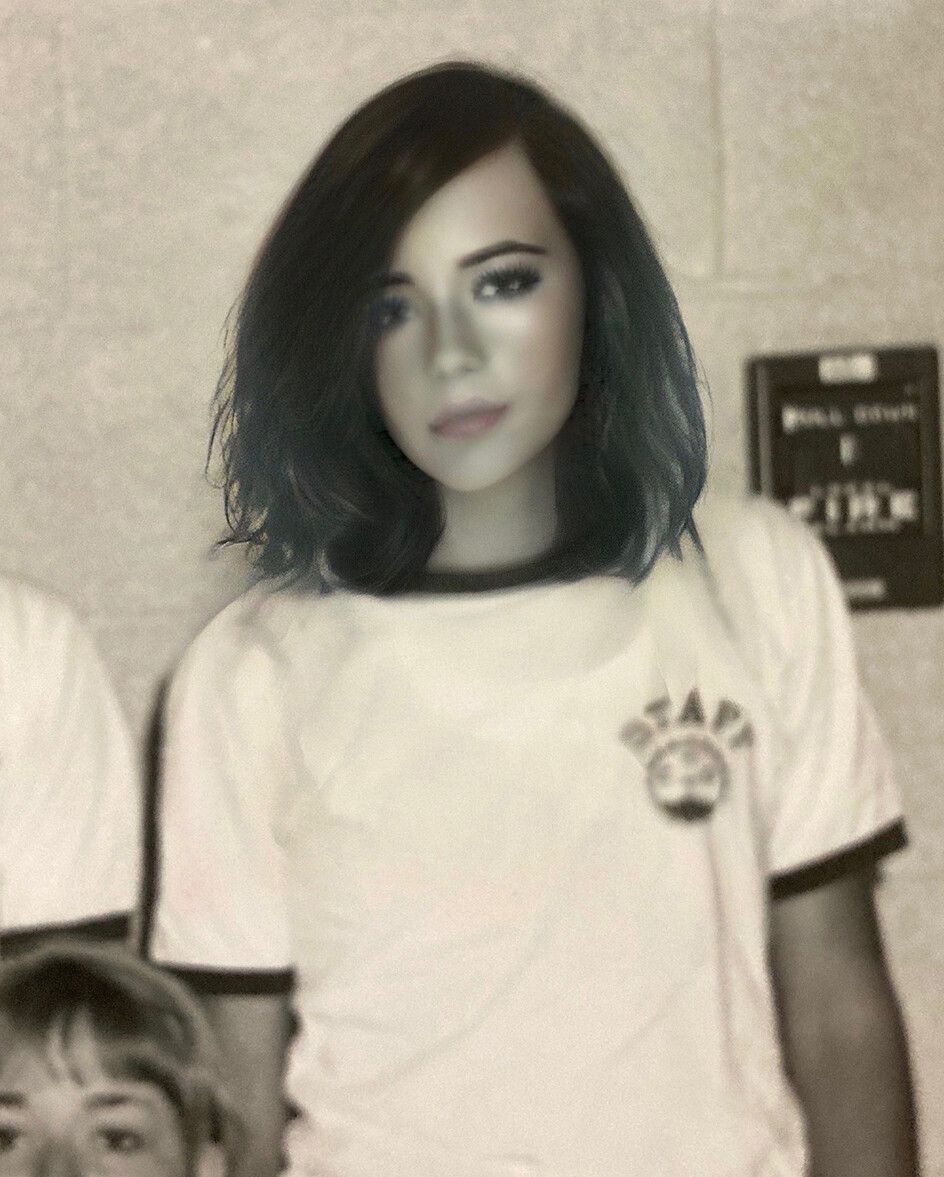

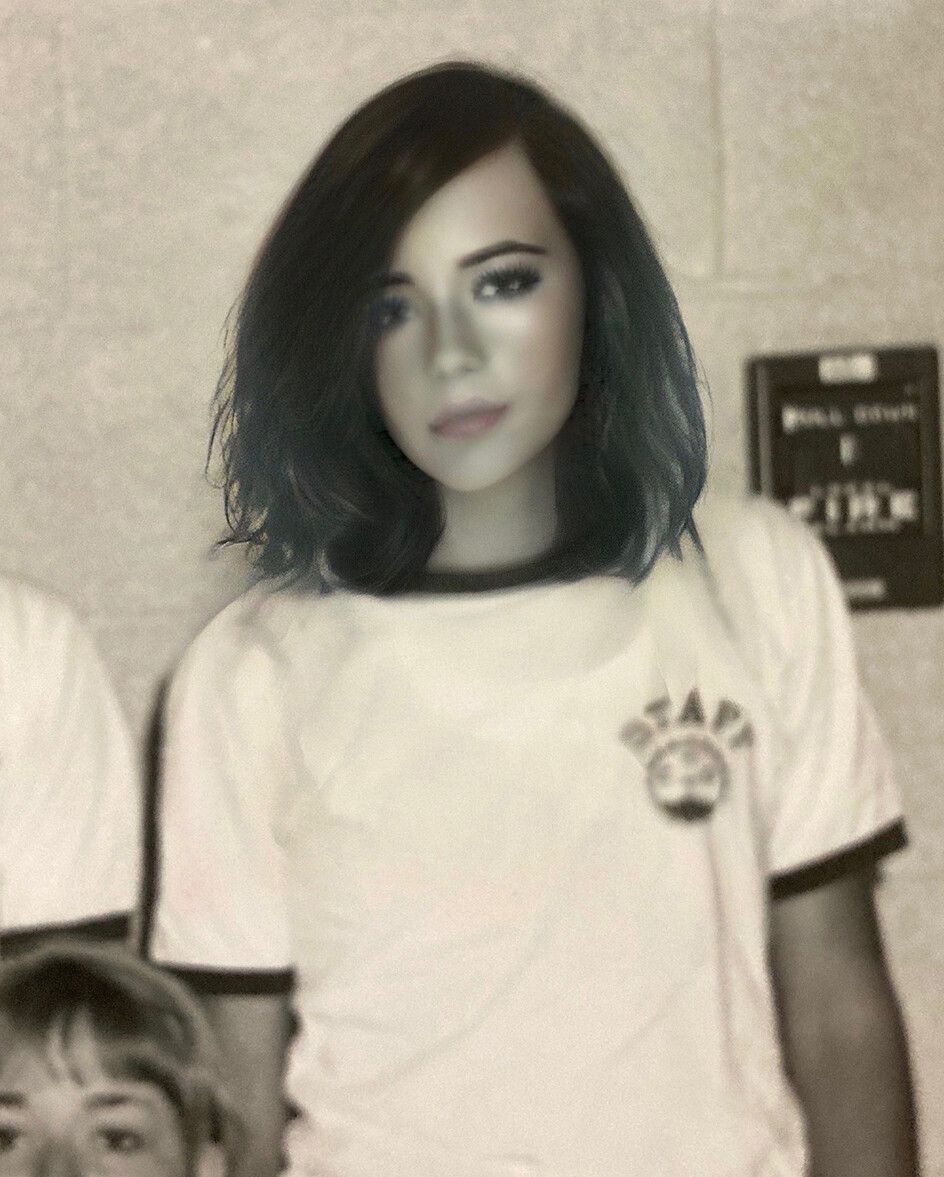

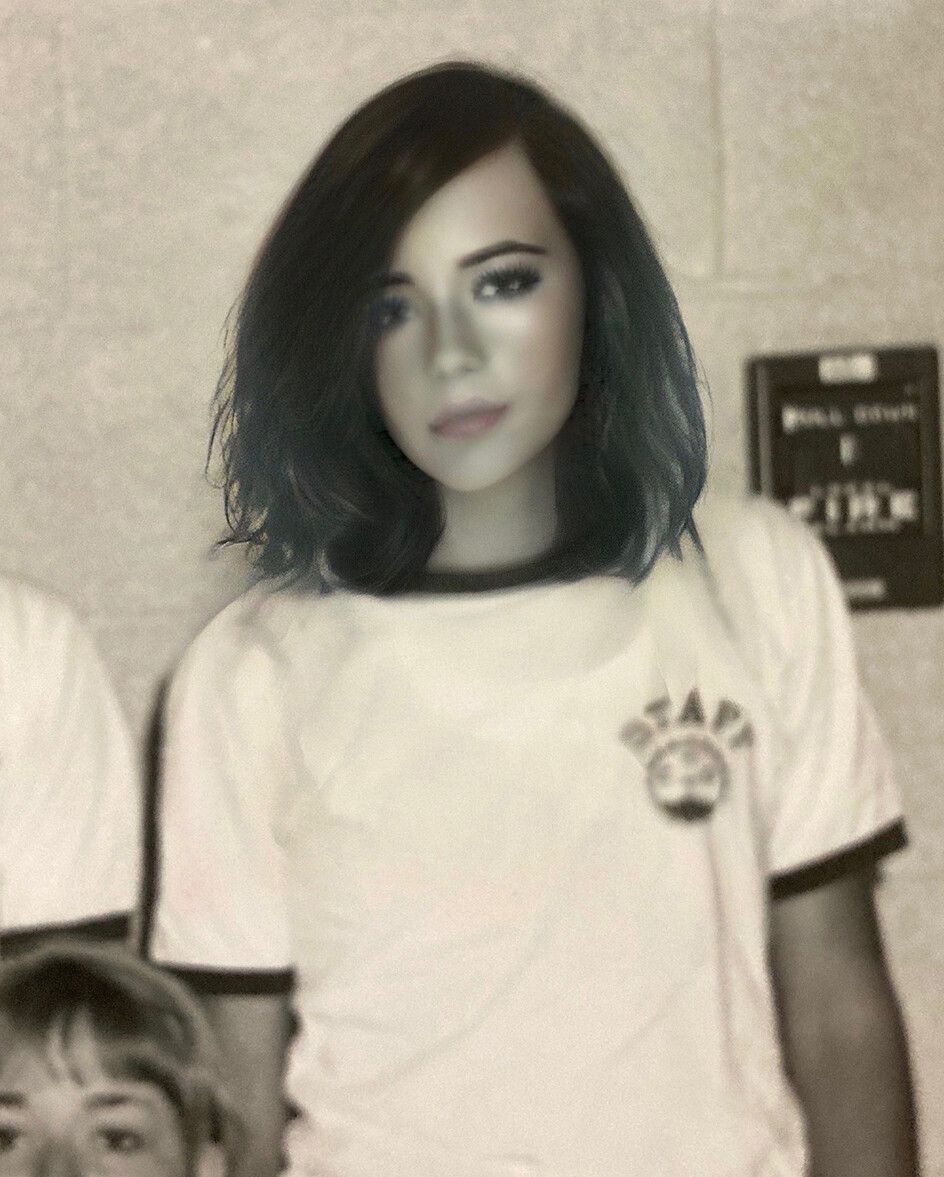

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

One of many photos of Sante created prior to her transition using a gender-swap filter overlay. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

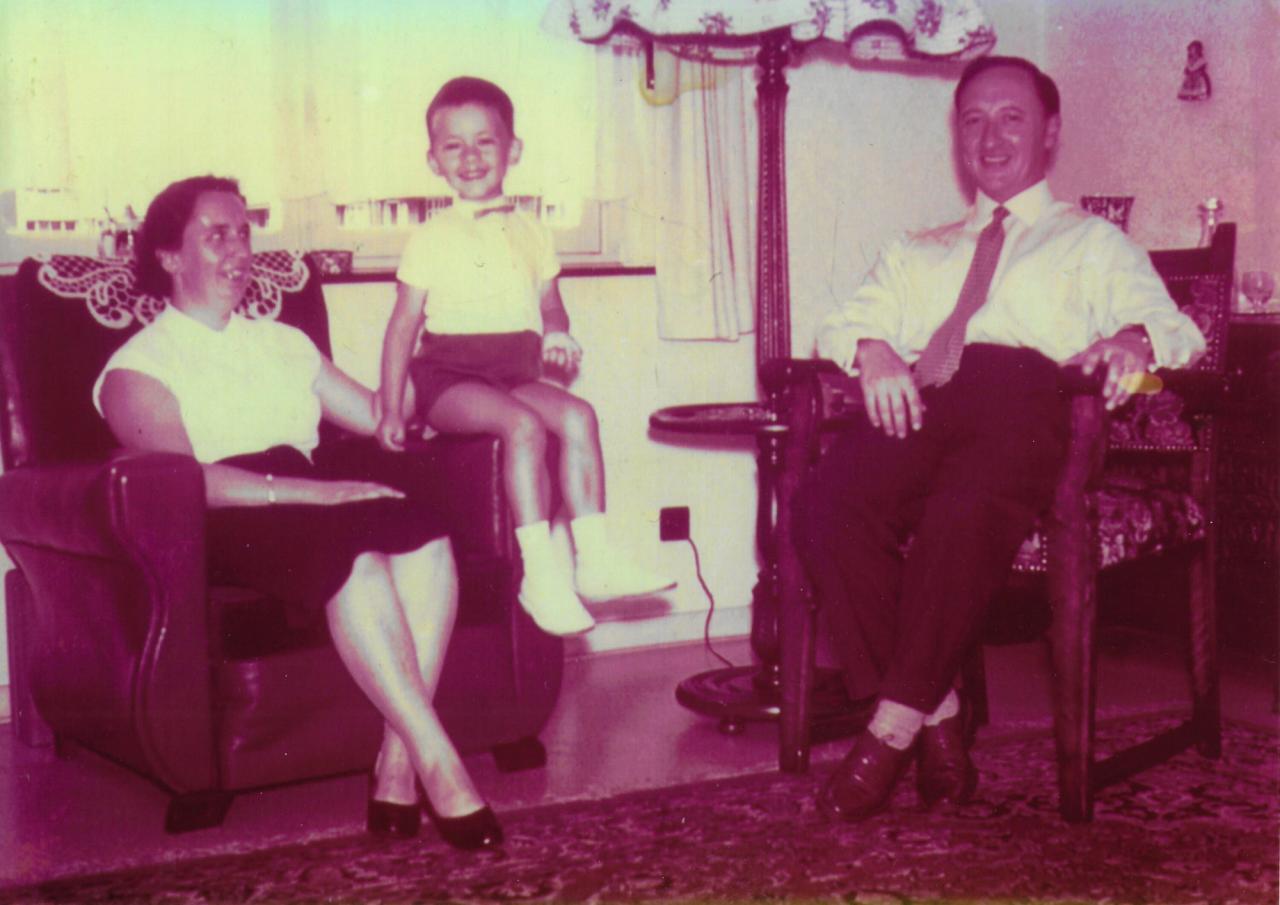

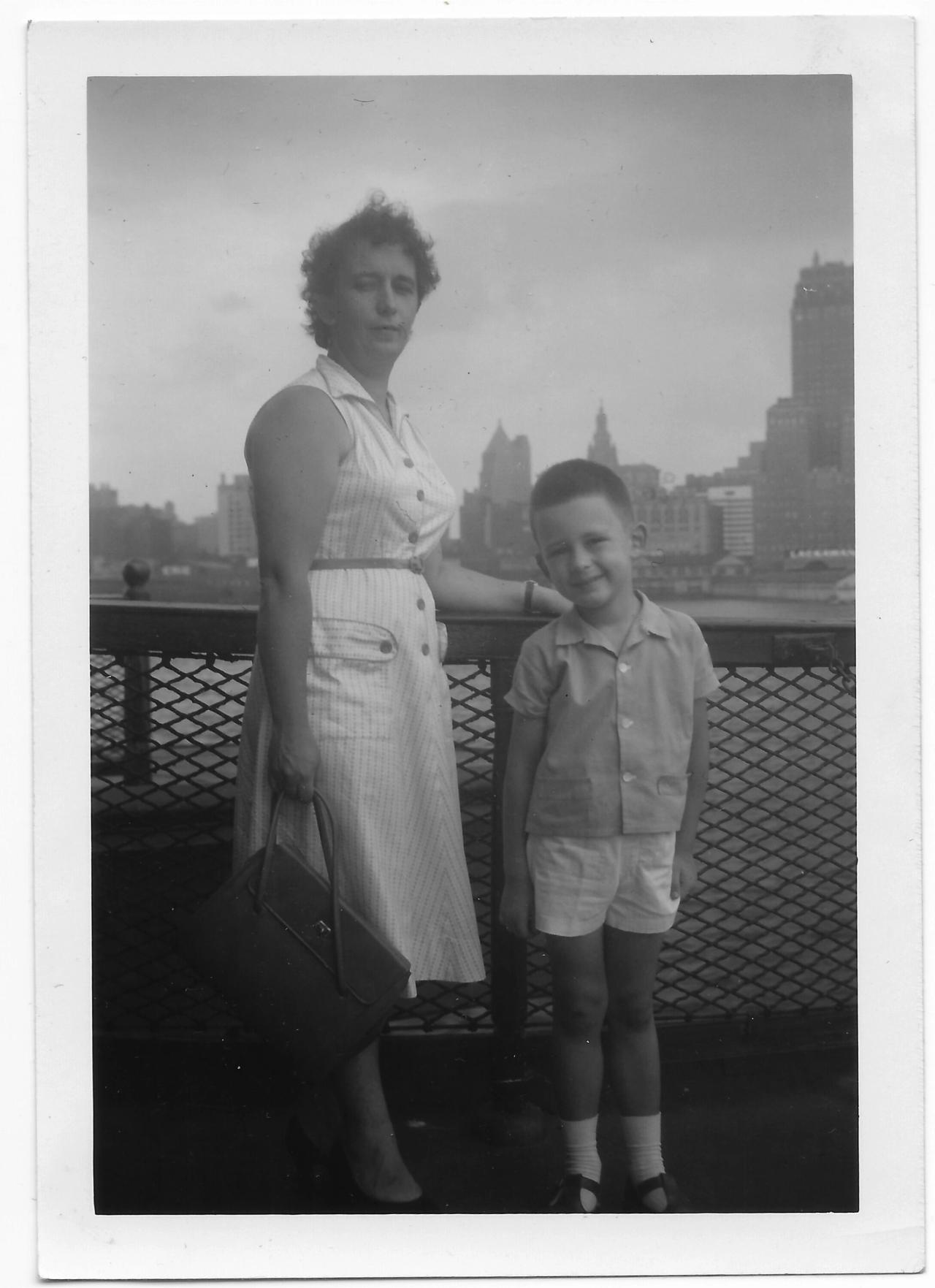

Sante as a child with her parents. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

Those pictures were so amazing that that was my first thought: I gotta write a book. I mean, it was going to happen anyway, the transitioning, but the pictures really clinched it immediately. Within twenty-four hours of my passing the first one through, I knew I was going to write a book. Anyway, so I have this life on film, as it were, and it was exciting and gratifying and kind of heartbreaking. And of course, as I say in the book, if I really think about what it would have been like to be my parents’ daughter, then, aye yi yi. My parents already— Everything I did was hyper-controlled. My mother was a helicopter parent avant la lettre, and raided my room, went through all my drawers all the time, cross-examined me about everything.

I eventually found the means to dodge it, and my ticket out was a scholarship to a Jesuit high school in New York City. So that was a great thing.

But the fact is, if I’d been a girl, that wouldn’t have happened. And I probably would have been kind of surveilled. What kind of peasant parenting would I have been subject to then? Would they have allowed me to go to college out of state? Would I have had to get married to get away from them? These are very real thoughts.

I can’t help but feel mild twinges of guilt now and then when I realize how easy my life has been in certain regards as compared to women who were assigned female at birth. So my life as a girl would be like…. It did occur to me to try writing the alternative scenario, but the branch forked so far back that it’s arbitrary. I have no idea how my life would have proceeded, and if we’re going to go into total Candy Land and imagine that I could have transitioned when I was a teenager, which, in that time, I would have had to have not only very indulgent parents, but somebody close to me with extensive medical knowledge.

“I can’t help but feel mild twinges of guilt now and then when I realize how easy my life has been in certain regards as compared to women who were assigned female at birth.”

This was not information that you could come across, not even at the public library, to find one of the few doctors in America who was undertaking gender dysphoria. There were like two people or three people. If you read, a very, very enlightening book called Histories of the Transgender Child by Jules Gill-Peterson—it’s an excellent book, and it was so eye-opening about so many things. Anyway, I realize I try to project myself into that book and I can’t; there’s no point of contact. I could not have known. I have known people who knew then, and some were able to find— People I’ve met recently who were able to find their way through the channels, but….

Sixty-six years later, here I am. I’m damn glad I did this before I died. I don’t know how long I’ll have to enjoy it, but here I am. I wish it had come earlier, but it didn’t. So what can I do, right? Except live.

SB: An interesting nuance to your story, too, is that your mother had a miscarriage before you were born. You would have had an older sister, and your mother, at various turns, would refer to you almost as her daughter.

LS: Yes. Yeah. My sister, Marie-Luce was stillborn a year and a month before me. When I was born, my mother was warned not to try it again. So, basically, I was born an only child. A year and a month later, they gave me her names in reverse. She was Marie-Luce, and I became Luc Marie. And all I’ve done was add a “y” to that—basically it’s the same name.

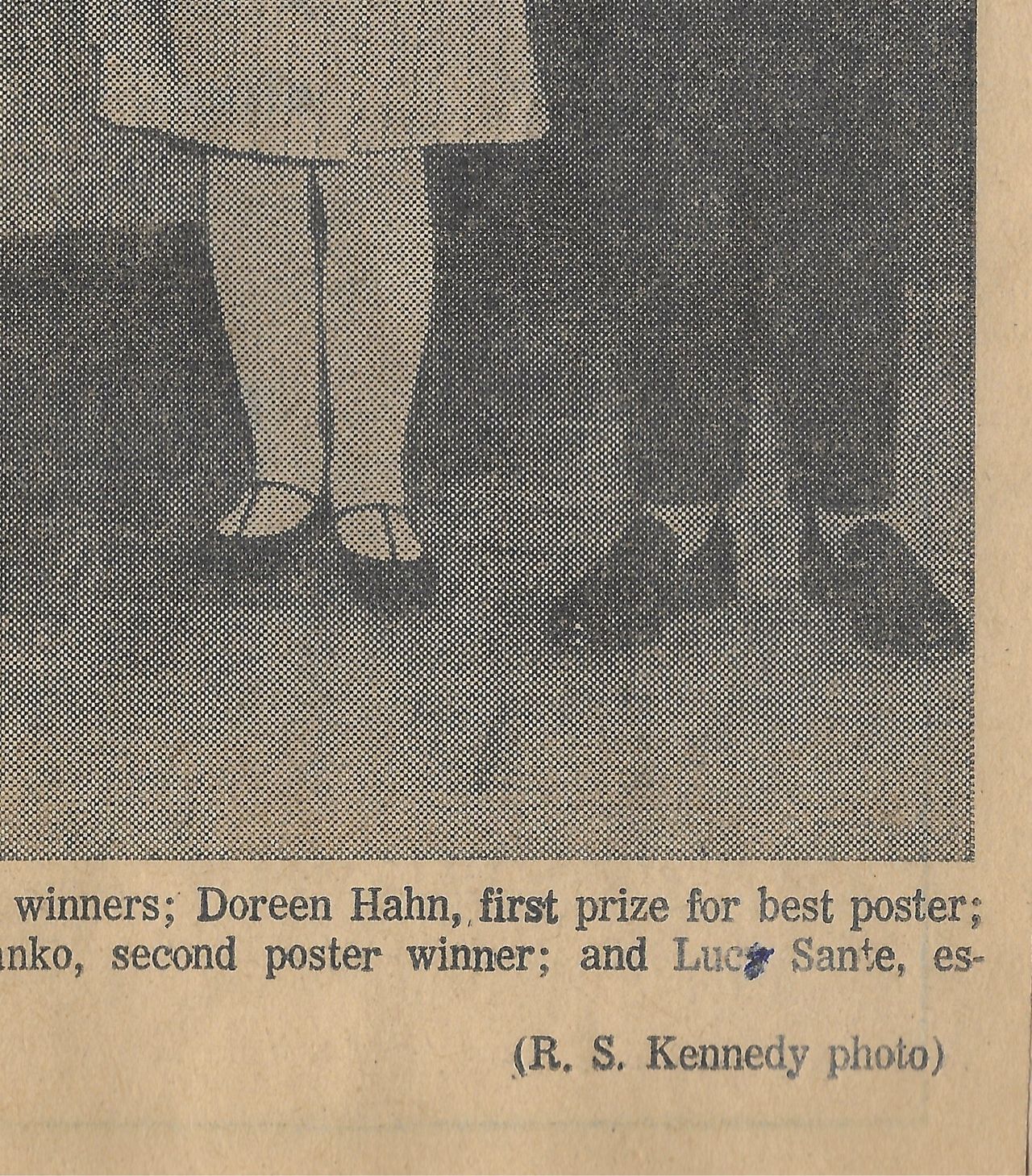

A newspaper caption with a typo misspelling Sante’s birth name of Luc as “Lucy” when she was 12. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

My mother was distraught. She never recovered from it. I have a feeling— Obviously, I didn’t know my mother before my birth, but I have a feeling that my mother was already a troubled person before that. But she had a certain naïve joie de vivre that popped up every now and again, at least in photographs. But then, after the death of this girl, she was never the same again. She was on mood drugs of every sort, all through her life. And, yeah, she conflated this…. She would often refer to “la petite,” the little girl, as if she might be somewhere in the house, but then she would conflate me and her and she always called me by female diminutives—ma fille-fille. Always. Until I was, like, a teenager, she was still doing that. Well, you know, simultaneously slapping me, right? Yeah. My mother was a complicated person.

SB: And you, as children do, imagined your sister being a presence—maybe a ghostly one amongst the house—but sometimes also, were like, maybe my sister is me.

LS: Right. I know this well. This is the very strange pattern of desire here, which combines longing and identification simultaneously. “She’s there.” “She’s my sister.” “She’s my love object.” “She’s me.” It’s kind of freaky, you know? I mean, when I realized that this is a primordial feeling from, what age, 3? I don’t know. It goes so far back, it’s unreachable.

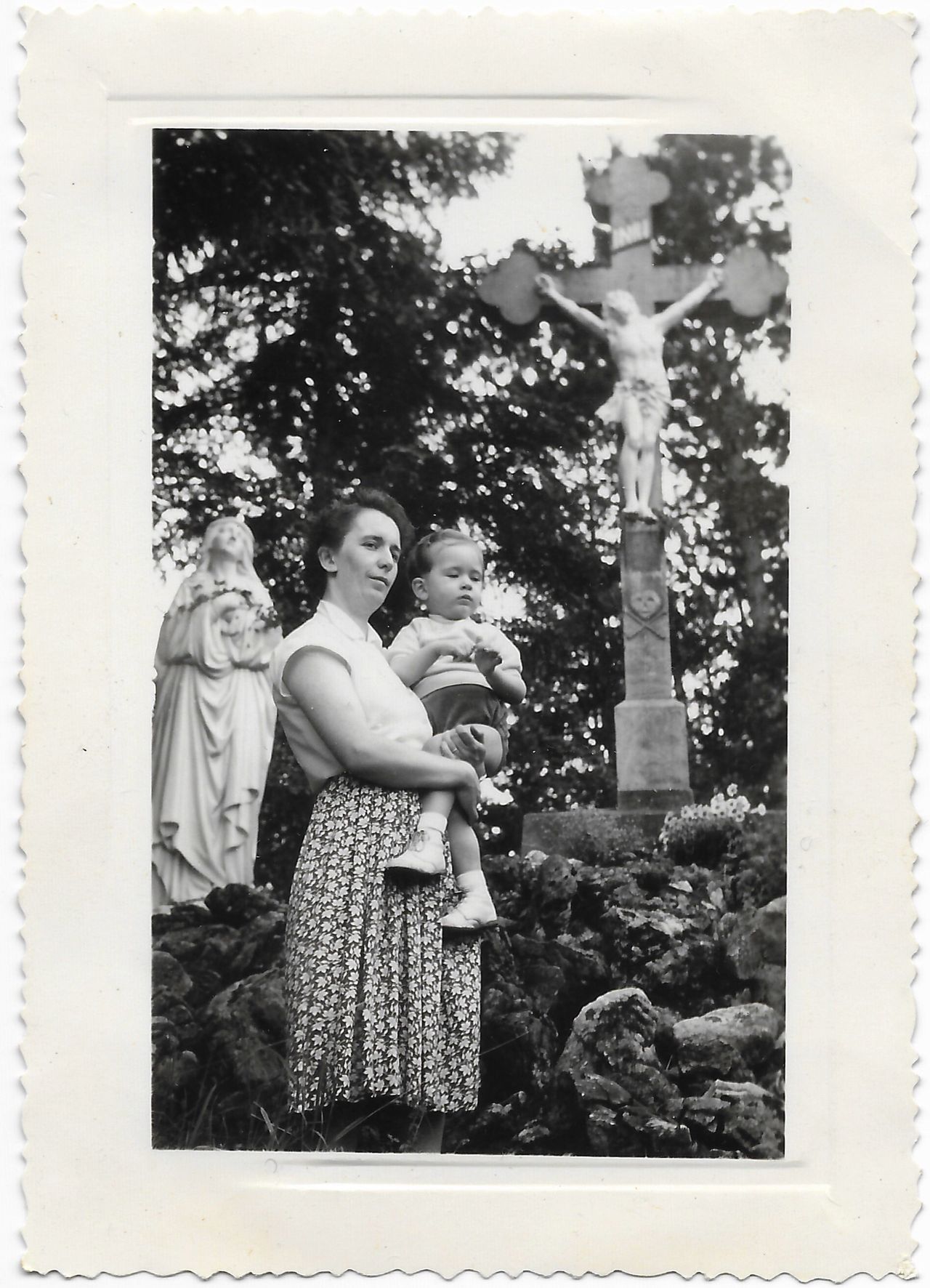

Sante as a young child. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

SB: Going back to your childhood, you note in the book that you had these out-of-body experiences, from early adolescence on. The first one occurred notably, I think, when you went to a Boy Scouts camp.

“Boy Scout camp. Oh, my God. That was a trauma of major proportions.”

LS: Oh, God.

SB: You describe it as an overwhelming sense of dislocation, writing that you were “like a character in a science fiction novel, trapped between dimensions.” What were some of these other out-of-body instances in your youth that you might recall?

LS: Oh, God, I don’t think I have any really good ones, because it would happen sometimes when I was like, Oh, my, I’m in a room with all these important people. What am I doing in this room with all these important people? That kind of thing. Probably there were some more psychosexual ones, but I don’t recall them. Maybe I’ve blocked them for various self-protective reasons. I don’t know, but certainly Boy Scout camp. Oh, my God. That was a trauma of major proportions.

Sante as a small child with her mother. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

SB: [Laughs] Earlier in your life, you had, of course, also experienced dislocation, namely your family’s move from Belgium to America. And I think it was actually—we should say here—several moves. You moved back and forth between America and Belgium, spending second and third grade split between these American and Belgian schools. And you also crossed the Atlantic seven times during this period of your youth.

LS: Mm-hmm.

SB: Do you see any links between this immigrant experience and your transition?

LS: Oh, I mean there are so many, it’s crazy. Because I was passing. I had to learn very fast, because not only did we not move into an immigrant community when we moved here, there was no immigrant community. There were no other immigrants. Seriously. There was a postwar immigration wave from Europe that lasted until the mid to late fifties, maybe. It was over by then. And it wasn’t until 1965 that the U.S. removed national quotas. We got in quickly because Belgium never came close to filling its quota.

Belgians don’t tend to move very often. And I started school not knowing any English. I had a memorable exchange with a nun where she said, “It’s a warm day. Why don’t you take off your sweater?” And she went over and, since I was unresponsive, she yanked it off me, and I had on a little undershirt and a shirt-collared dickey. [Laughter] That was a moment of revelation there.

Anyway, I wasn’t really persecuted or anything. I was laughed at, I was imitated—it wasn’t terribly traumatic—but I needed to figure out how to pass, quickly. Learning from being observant and aware of everybody and everything, you know, just like being covered with sensors and taking everything in and trying to mold these into something that resembled a personality. So transitioning, there’s all these elements about that that just felt incredibly familiar.

SB: Decades later, too.

LS: Yeah, yeah.

SB: I wanted to ask you about your family’s factory-worker background. It’s a lineage that goes back, as you’ve written, at least two or three centuries, and of your family across time, you’ve noted, “The generations pass in an endless parade of hunched women in kerchiefs and hunched men in caps, weighed down by the loads of sticks on their backs, without much to differentiate the centuries,” a profound take on time and family. Your father worked in a Teflon factory. You yourself even sort of in a moment of protest to your parents, [laughs] in a roundabout way, anyway—worked in a plastics factory.

LS: I did that for a year and a half, mind you.

Sante as a child with her mother. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

SB: [Laughs] What do you make of this ancestral history of factory work across generations, and how do you view it in the context of your life today?

LS: That’s an interesting one. Well, you know, because the waters of the Vesdre River are very low in calcium, it became an ideal spot for washing wool. It started being used for that in the Middle Ages. But then, at the start of the Industrial Revolution, Scottish engineers came over and they built the textile industry in Verviers. There were as many as a hundred factories at various points. This all started to crumble in the fifties, along with everything else in European industry. The factories were still there into the beginning of the twenty-first century. Now they’re gone. And with all these blank spots, the town looks like…. Well, maybe not quite Gary, Indiana, but on the road there.

Anyway, yeah as far as I can tell—because I’ve gone through genealogical records—because I knew nothing about my family history. I found out that we were in the first census, which was in 1221, our name inscribed for the first time. So we’ve been there for at least eight hundred years. And I know my grandfather and my great-grandfather both worked for the only textile company that still remains: Simonis. The reason they still remain in business is because they’ve got a near-monopoly on green baize for billiard tables worldwide.

SB: That’s a niche. [Laughs]

LS: Yes.

SB: Wow.

LS: Factory work was… it’s the only thing I knew. Well, my mother’s family had been tenant farmers until the Depression. Then they moved to the city and went to work in chocolate factories, which was another big item in the local economy. And I myself, I worked in the plastics factory when I was a teenager, beginning a full year illegally underage. And then I worked in a tool-and-die shop. When I got out of college, it was like, I didn’t know how to think about anything, any job other than manufacturing, so it took me a while to orient myself in that world.

SB: When did your literary aspirations begin? When did you imagine yourself to be a writer?

Cover of Tintin and the World of Hergé by Benoit Peeters. (Courtesy Benoit Peeters)

LS: I don’t know which came first, but both things happened in fourth grade, so when I was about 10. My teacher, Mrs. Gibbs, told me I had talent as a writer—the first glimmer I ever had of this. And probably after that, I wrote a composition, on “what I want to be when I grow up.” That was why I wanted to be a writer. Illustrated with a picture of Robert Louis Stevenson.

SB: And Tintin was your first magazine subscription, which of course is, it’s iconic in Belgium.

LS: Not only that, but my father’s nickname when he was a kid, he was short, blond, and wore plus fours. He’s going to be Tintin, right?

SB: [Laughs] Tell me about this influence on you, both as a writer and an artist. Digging through those magazines and books.

LS: Well, I mean, yeah, Tintin’s been part of my fabric all my life. And of course, I recognize now how, you know, horribly exploitative, colonial, and all that kind of thing they are, absolutely. At the same time, it wasn’t really the story or their set-up as it was the clear line of Hergé, which is derived from Japanese woodblock prints from ukiyo-e and, that’s very, very powerful and still, it’s the primordial essence of “picture” in my head, I think.

SB: Another big important literary influence in your early years was Terry Southern. There was this book, Writers in Revolt that you’ve written changed your life, which—this was an anthology Southern had co-edited in 1962, which you came across in the seventh grade. Tell me about that book. What was it about those essays or that particular collection?

Poets Allen Ginsberg (left) and Peter Orlowski. (Photo: Herbert Rusche)

LS: Well, it was not only Terry Southern, by the way. Also Alexander Trocchi, who wrote the only heroin-addiction novel anybody ever needs to read, which is Caine’s Book. It’s the one that tells all the truth. And he was also a member of the Situationist International. He was always fomenting revolution and, well, he was also a junkie, as so often happens. And Richard Seaver, who was the first big house publisher to publish a lot of this stuff. Well this book, I mention in I Heard Her Call My Name how a boy in my class, Frank Hourtel—may he rest in peace—got up in class and started talking about—he just did this to annoy the nun—sort of talking about Allen Ginsberg, the famous bearded poet, and his boyfriend, Peter Orlovsky. The nun was very upset. I think he was sent to detention or whatever.

SB: [Laughs]

LS: But I went to the library and I poked around until I found Allen Ginsberg. The first part of “Howl” is entirely in this collection there.

There’s also an excerpt, probably the only excerpt they could actually print, from Naked Lunch by William Burroughs and a whole lot of other writers who became important to me later on. Like, I realize now, one writer who I’ve been reading a lot of lately, I first encountered in that book and that’s Curzio Malaparte. Who’s this—

SB: Short-story writer.

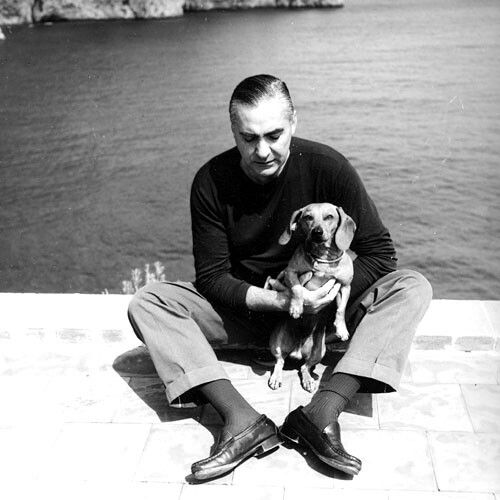

Writer Curzio Malaparte. (Photo: Maurizio Serra)

LS: —bananas, really ambiguous Italian writer from between the wars. Well, his book Kaputt, is one of the most extraordinary books I’ve ever read about World War Two. And really, anybody who wants to read about the Soviet war in the East—it’s got the most bloodcurdling stuff. But it’s also majestic and mute. It’s like a symphony, this book, like, really, truly like a symphony.

SB: Malaparte, of course, lived in this extraordinary house.

LS: Oh, God. Yeah, yeah. Which we all saw. And, in contempt with Brigitte Bardot sunning herself on the roof.

SB: [Laughs] Yeah. And on Ginsberg, you’ve written this line that I absolutely love, which is: “Poetic madness was something I thought I could feel in my body.”

LS: Yeah. [Laughter]

SB: About “Howl.” But I think it’s interesting, this idea of poetic madness. It’s like, was that actually what you were feeling? Or….

LS: I think this was really common currency amongst school-age poets in the late sixties. We were all reading, you know, poetic madness, I mean, Ginsberg, but also, William Blake and [Charles] Baudelaire—all these people who were illuminated, you know, [Arthur] Rimbaud, all these people who were struck by lightning and [Antonin] Artaud. The Artaud anthology was prominently displayed in every bookstore. He was the man who wrote about Van Gogh, the man “suicided by society.” So this idea of the suffering artist was very, very big among all of us? I mean, come on.

“We were, like, 14 years old. How were we going to know about madness, poetic or not?”

We were, like, 14 years old. How were we going to know about madness, poetic or not?

SB: [Laughs] You moved to New York in the seventies, and. And this is skipping ahead a bit, but you find a job in the mailroom at The New York Review of Books, and later, one of the editors there, Barbara Epstein, asks you to be her assistant, which proves life-changing, actually.

LS: Mm-hmm.

SB: And this in another sort of roundabout way, led to your first published professional piece of writing, in 1981, at age 27. It was a review of Albert Goldman’s biography of Elvis. [Laughs] Tell me about this moment and seeing your byline for the first time.

LS:I happened to read an excerpt from the biography of Elvis in Rolling Stone. I just needed to pick up something to read on a bus trip. And I quickly realized that this was complete—can I use four-letter words on this show? It was complete bullshit. It was just a big lie from top to bottom.

Basically it was a more sophisticated version of what you’d read in like National Enquirer or something like that. It was shocking because Albert Goldman—something I didn’t mention in the piece at the time—but, frankly, he had been somebody kind of respected. He wrote a pretty damn good biography of Lenny Bruce. He was a hipster in the old mold, and he resented anybody that came after him. Plus, he had this weird cultural power because he was the pop culture critic for Life magazine. Think about what the implications of that were.

Anyway, he wrote this hatchet job, and it got a lot of attention. And I felt I needed to blow the whistle. I knew that Bob Silvers, who was Barbara’s coeditor, had sent the book out to, like, three people who turned it down. So I swiped the book from the “current titles” cart and wrote a review over the weekend, terrified they would discover that I had stolen the book. Lo and behold, they published it. I was reminded of this line from Raymond Roussel when he published his first book, which was a long poem—La Vue, I think? I forget.

Anyway, when he published his first book, which he financed—and it’s unknown how many copies ever were sold at least at the time of publication—but he imagined that his glory could be felt as far away as China. It was like, a sort of wind that would ruffle the clothing of people in faraway lands. And I immediately thought of that line because, in fact, my friends said, “Oh, wow, that’s great.” I heard from six or seven people about this.

In fact, the first ten years—I wrote for magazines for ten years before I published a book—and I never, ever, ever got any feedback from anybody except people who were already close to me. So it was an important life lesson.

SB: [Laughs] Yeah.

“Writing is not just throwing a rock into a well. It’s the most precious rock that you’ve made yourself through twelve thousand centuries of sedimentation. And you throw it into a well, and then it’s gone—bye.”

LS: Writing is not just throwing a rock into a well. It’s the most precious rock that you’ve made yourself through twelve thousand centuries of sedimentation. And you throw it into a well, and then it’s gone—bye.

SB: [Laughs] I wanted to read something from that review that you did, because looking back at it, I do find it interesting that you chose to write about, as you put it, this hatchet job on Elvis. But Elvis was, of course, this icon of masculinity, of American masculinity. And in part of the review, you described this culture of Elvis impersonators. [Laughs] You write, “Dozens of impersonators appeared. Seemingly any white male could pass muster as a ‘tribute’ if some six feet in height, weighing less than the 255 pounds of the King’s final tonnage, and able to wear a black vinyl rug and a gem-encrusted white jumpsuit open to the navel. Some, like transsexuals, went to the length of having their features surgically altered, the better to resemble Him.”

LS: Wow.

SB: Hearing that now, what does that bring up for you?

LS: Oh, that’s weird. Yeah, I’d forgotten that. I haven’t read that thing in… who knows?

SB: [Laughs]

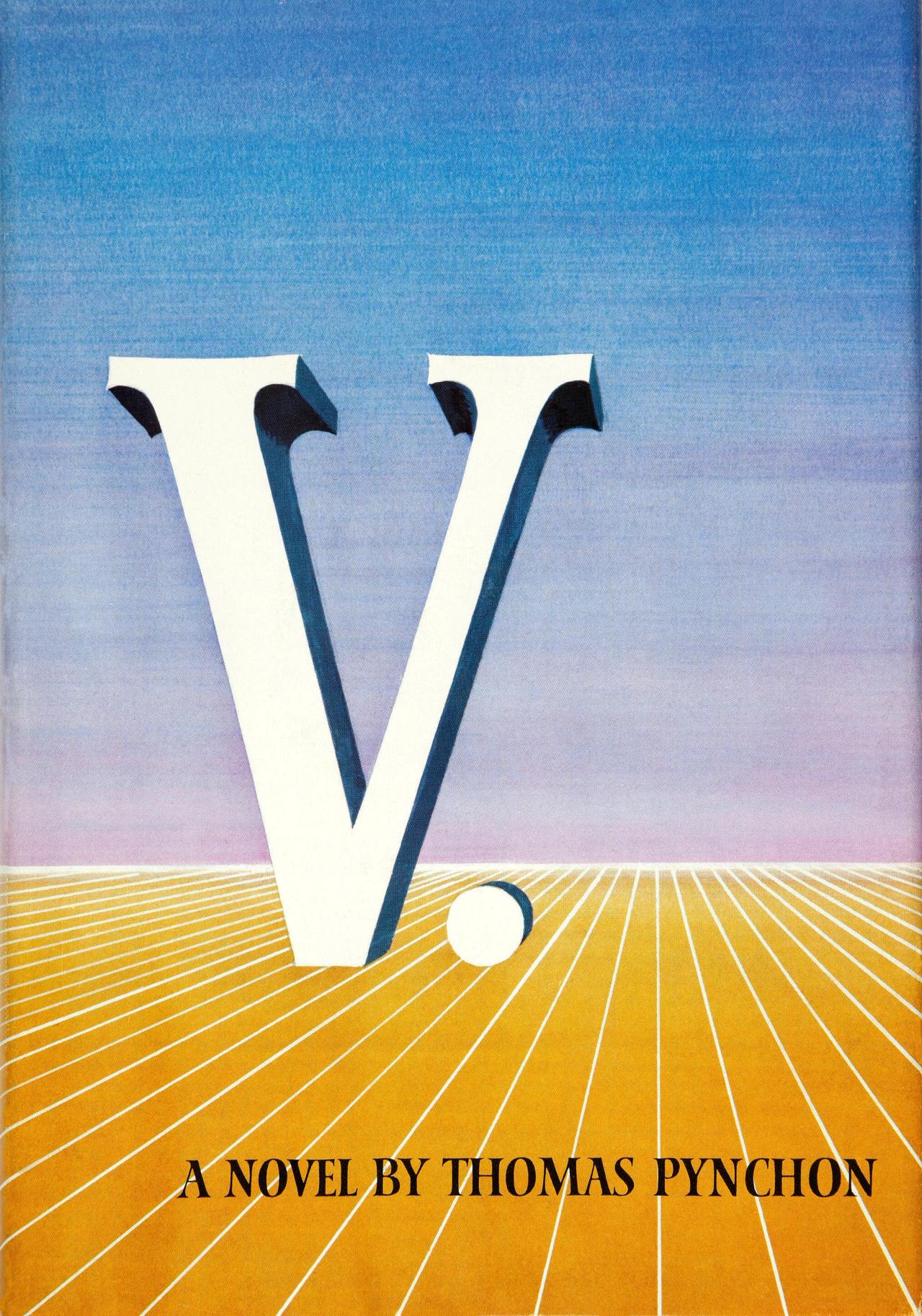

Cover of V. (1963) by Thomas Pynchon. (Courtesy J. B. Lippincott & Co.)

LS: Gosh. Well, I think that’s funny because I think I’ve always had…. I have a strong uncanny valley thing about me. It’s improved over the years, and I’ve known people and contexts vary and personalities and all that. But I’ve also had a weird thing about plastic surgery. I don’t know if you have ever read V. by Thomas Pynchon. The third chapter is a detailed description of a rhinoplasty… and aye yi yi. I remember even being in high school and some girl would come in with a new nose. And there was something just so disorienting about this, right? And even now, obviously I’m not having anything done because I’m too old. But when I think about plastic surgery—like, “It’d be nice to enhance my lips”—it freaks me out a little, too. I mean, I don’t know, it’s like, physical, this reaction—it’s not moral.

SB: Your literary breakthrough, if I could call it that, was Low Life, this book you mentioned earlier about New York City’s underbelly between particular years, 1840 and 1919, and about, as you put it in the introduction, “the poor, the marginal, the dispossessed, the depraved, the defective, the recalcitrant.” What was it like immersing yourself in that nineteenth-century world in those years? You’re in the late eighties writing about the nineteenth century. What did that do to you? And you were living on the Lower East Side, too.

LS: Yeah, yeah. I started thinking about the stuff in the mid eighties, just at the point where the landlords were moving in, basically, big time. We were being invaded. And it was my attempt to hold on. I was afraid of not so much what was happening then as what is happening now.

I was terrified that we would become the city that it is right now, which is lockdown. There’s no freedom and nobody can afford anything. Useful businesses are gone, and there’s nothing but high-end garbage.

Meanwhile, though, it was also a kind of balm for me, writing this book, because my youth had just ended, and I didn’t know where to go or what to replace that with. What does that mean, “my youth ended”? Well, it means a lot of things. I was in a bad marriage. My friends were all pursuing individual interests. We didn’t hang out the way we used to. And also, I didn’t feel that attachment to pop culture the way I did until about 1982 or so—that it spoke for me. It no longer spoke for me. So going into the past, I was entering a new world.

“It was also a kind of balm for me, writing Low Life, because my youth had just ended, and I didn’t know where to go or what to replace that with.”

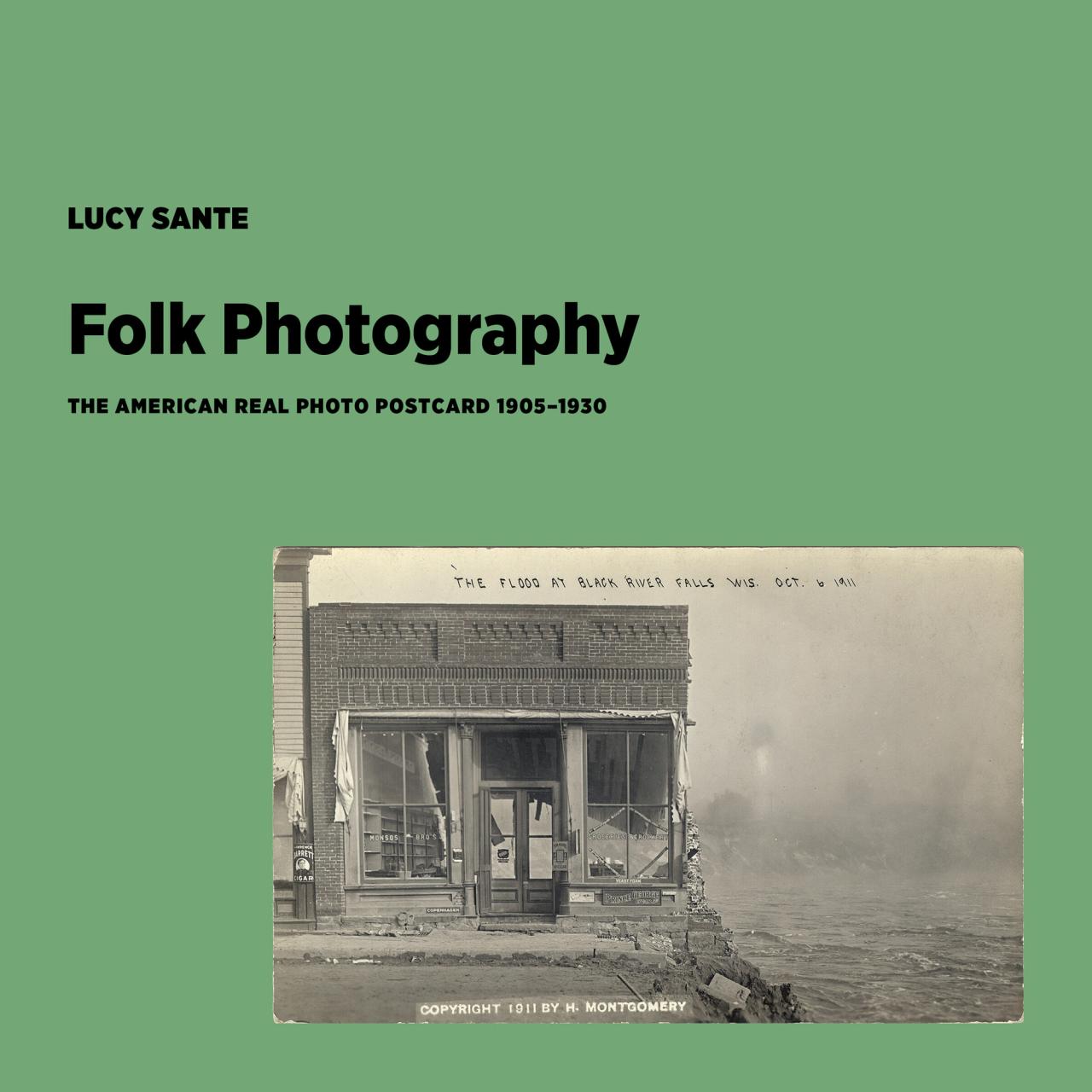

It was novelty for me. It wasn’t old. It was new. And I went into that so hard. There’s another part in I Heard Her Call My Name where I talk about these books I didn’t write. Those were all consequences of Low Life because— Well, one book I did write, for example, was Folk Photography, which was about photo postcards from the beginning of the twentieth century. That, too, was a result of immersing myself in the world of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which I practically lived there for about twenty years, actually.

SB: And, more recently, you have this other book, The Other Paris, where it’s a similarly engrossing take on another city and its deep past. There’s this line that I absolutely love from it, where you write that “The city’s principal constituent matter is accrued time,” which I think you could look at any city like that, but Paris.

LS: Oh, yeah. Well that’s the thing. You might not quite see it in New York because it tears everything down. But in Paris, they’ve been pretty good about that. There’s a lot of buildings that would not have survived in Manhattan. They’re still there in Paris—the equivalent. Institutions are another matter, but the buildings are at least preserved.

Cover of Folk Photography (2024) by Lucy Sante. (Courtesy Yeti Publishing)

SB: This deep interest in the past, as you mentioned in this book, Folk Photography, over the years, photography has been a deep interest of yours—beyond just writing, also as a collector of these early-twentieth-century photoreal postcards and found photographs, and many of your books, I should say, also include imagery alongside the text, so—

LS: Only one of my books doesn’t.

SB: Yeah, it’s almost these double readings, and they illuminate the text in a really interesting way. What led to this particular interest in photography?

LS: Well, I did think about photography beginning when I was a teenager, and I learned to develop and print and all that kind of stuff. And then, I went on a few photo expeditions and I thought, well, I’m a big fan of Walker Evans and Robert Frank, and I’m just going to be their imitator for the rest of my days. So what am I doing? This is not a direction I should be moving in. I kind of put that interest away until, as a consequence of doing picture research for Low Life, I stumbled on these police evidence photos in the municipal archives. And they blew my mind.

And it was like I said before about those gender-swapped photos that are in the current book. Same thing. When I saw these pictures, my first thought was, This is going to be a book. And bingo, it was. And as a consequence of that, I started getting like a million offers to write about photography.

Now there are more people, but thirty years ago, there were really not that many people who were writing about photography in a serious way—a serious and nonacademic way. So I kind of had a field to myself for ten years or something like that.

SB: And along the way, you also start collecting these postcards that become a collection of twenty-five-hundred plus. Tell me about this collection. And also, how did you go about building it up?

The Astor Place flea market in the 1980s, held in front of Cooper Union's Foundation Building. (Courtesy Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation)

LS: Well, it began when there was this kind of wildcat flea market on Astor Place in Manhattan from, I don’t know, ’80, ’81 until ’87, maybe? More or less left alone by the cops, at least in the early years, this vast profusion of every kind of stuff—it was just crazy. And one day I saw this guy standing in front of Cooper Union with these two small piles of photographs at his feet. And they were photo postcards from the American intervention into the Mexican Revolution in Veracruz in 1914, I think it was. Holy cats. It must have been some old guy who died, and his landlord put out his possessions on the sidewalk. He found them and I bought the whole inventory for ten bucks. It was almost thirty pictures, I think. That set me off.

Pretty soon I was going to every antique store I could find. They usually have a wire rack or a box or something, and they were five cents, ten cents, twenty-five cents—maybe fifty cents. And I’m buying old Pope photographs as well. But I started really directing myself to all these postcards because there were so many of them, they were so vast, there were so many crazily great pictures. I imagined I could map the whole phenomenon. And they were cheap—of course, that was a big goad.

I said to myself, Okay, I’m going to write a book, and when I write the book, I’m going to stop collecting. So I wrote the book in 2009, and I stopped collecting. I no longer collect postcards or photographs, unless something really crazily great turns up right under my nose—I won’t be able to resist it. But basically, that’s how I keep myself from outspending my wallet is by putting end dates on things like collections, you know.

SB: And these were produced during a very specific period of time, and number of years. You’ve described them as “slices of otherwise irretrievable times and places.” And of found photographs, you’ve talked about them as “memories that have gone feral.” I love both of these ideas, but this idea of a postcard as a way of looking, or almost time travel, really.

LS: Right. Because the thing about these cards—well, now nobody sends postcards at all—but the late-twentieth-century idea of postcards, they were for tourists. A tourist would go to a place and say, I’ll use the postcards as proof I have been to this place and look at you. You’re not here with me. But the postcards produced in the first couple of decades of the twentieth century—especially these photo cards—are very, very localized. Mostly from small, even flyspeck towns in the middle of the country. They are meant for the locals to send to their family. Who are so far away they’ll never see this town. And it’s like here I am. This represents me. Even if it shows, like, the barn burning down, somehow people take pride in the image.

SB: Are there any photos in particular in your collection that have a pride of place for you?

LS: I guess the ones that have pride of place are the ones I’ve got displayed on my walls. I’ve got a series of river baptisms. These are not postcards—river baptisms, twenties tabloid crime photographs, spirit photographs. Now, those—whenever I see a spirit photograph, if I can afford it I buy it; that will be an interest that will never die. And for a while, I was collecting photographic matter relating to the Paris Commune as well.

SB: One of the pictures in your collection that’s in the book, shows this streetcar riot in Muskegon, Michigan. And it was made by Radium Photo. Your caption states—and I looked this up—it states that this place has been in business since 1908. And then, fascinatingly, it still exists.

LS: Yeah, yeah.

SB: I was awed by this. This place that produced this picture back in 1908 is still in business.

“It was a bit different forty years ago, fifty years ago, where to see a place that had been in business for a hundred years was not that exceptional. Now, it’s amazing that such a thing can still go on.”

LS: It’s still in business, right? It’s crazy. Especially since our time, it was a bit different really, forty years ago, fifty years ago, where to see a place that had been in business for a hundred years was not that exceptional. But it’s partly the way capitalism became hyper-capitalism in the last fifty years. Now, it’s amazing that such a thing can still go on.

SB: Yeah. And with what’s happened with the digital, too.

LS: Right. Yeah, that too. Because I’d love it if there were like a local photo studio where I could go get my picture taken inside a brandy snifter or something like that, but they’re gone.

SB: [Laughs] Flipping through this book, I also couldn’t stop looking at this other picture, which was circa 1910. It’s a postcard, from Denver, Colorado, and it’s of this man who appears to be flying in a plane above the state capitol.

LS: Right. Yeah, they built elaborate props and a lot of places—like if you went to the beach, if you went to Asbury Park, New Jersey, for example—there would be a hall that would be lined on both sides with different operators who would have a camera and a shifting selection of backdrops which were more or less realistic, all of them hand-painted. There were artists who specialized in backdrops, there were three-dimensional props to give it additional depth, and you could take your pick. You could be in an airplane. You could be in jail behind bars. You could be behind the bar, like an alcohol bar, especially during prohibition, et cetera, et cetera. Sky’s the limit. Or popular imagination is the limit.

SB: [Laughs]

LS: And people still—I don’t know to what extent it’s still being pursued today—but there are really great pictures just like that from, like, Romania in the 1970s, or China in the 1980s. Elaborate fantasy images of people in their street clothes standing in front of wild backdrops.

SB: I thought we’d finish today’s conversation on music, another subject you’ve written about at length and a deep passion of your childhood. You’ve written that “dancing to pop music gave me proof that there was a better world somewhere.” And in your essay Maybe People Would Be the Times, you write, “Almost everything of interest in New York City lies in some degree of proximity to music.” What is it about music that moves you and that you see as omnipresent, or this connective tissue to everything?

“For people of my approximate age, it really began with The Beatles on Ed Sullivan sixty years ago. We all watched this, and it marked all of us.”

LS: Partly, it was a phenomenon of my youth, beginning—well, you can date it variously to the birth of jazz, whatever. But really, for people of my approximate age, it really began with The Beatles on Ed Sullivan sixty years ago. We all watched this, and it marked all of us. Then I became aware, eventually, of music I was already hearing around me that I hadn’t noticed. Rhythm and blues. Years later, I got this shivery feeling from realizing, Oh, my God, I must have heard that in 1961. That’s why it sounds familiar.

And the cult of music—everybody wanted to be a rock star. This was a complete phenomenon that really lasted through to the end of the twentieth century, roughly. Twenty-first-century music has a completely different set of meanings because the media have changed, because there aren’t any record stores anymore. Young people certainly build communities around music, via various electronic means of transmission that are different. The sixties were like the big-tent model, where we all listened to all the same music, you know, soul, R&B, country, rock ‘n’ roll, British rock ‘n’ roll, et cetera—everything was swirled into this large big pot, and I liked almost all of it.

I liked ninety-nine percent of the music that you heard in the sixties. By the seventies, we were starting to drift apart into different constellations. Punk was more or less the camp where I was, and I could see my high-school classmates drifting away on the Laurel Canyon singer-songwriter iceberg, which was floating down the river.

SB: [Laughs]

LS: And other people were in

SB: Disco. [Laughs]

LS: Well, we were on disco, too.

SB: Yeah.

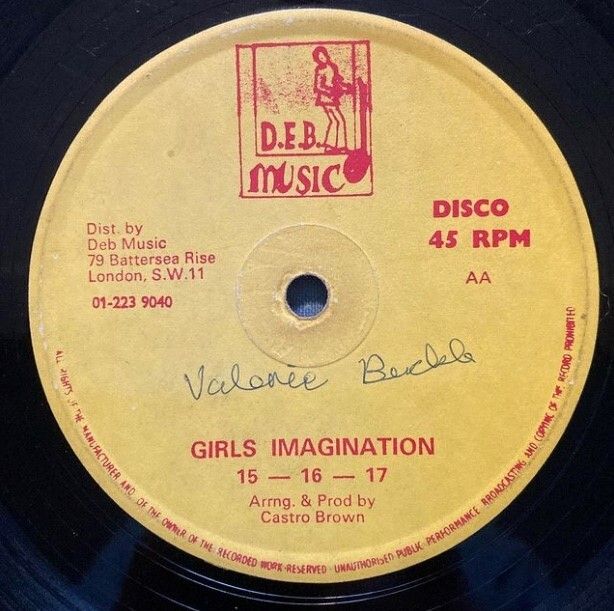

Sante’s record of “Girls Imagination” by 15 - 16 - 17. (Courtesy Lucy Sante)

LS: See, that’s the thing. Punk and disco, which is not a contradiction. It wasn’t in those days, and, but it wasn’t maybe the same disco as the people who bought “A Fifth of Beethoven,” you know what I mean?

There were different shadings of disco, but we liked the hard disco. I think I first went to a disco in 1973, and I can date it. You know why? Because of the cover of “Shame, Shame, Shame,” by Shirley & Company. And on the cover was a cartoon version of Shirley. And she’s finger shaming a cartoon version of Richard Nixon, who was to resign the following year. I remember being at the original Limelight on Sheridan Square, which was this big open-to-all gay club of that period, dancing to “Shame, Shame, Shame” by Shirley & Company.

SB: Thinking about the music connective tissue of your life, it’s like you were reading Rolling Stone and read this review, and then you’re like, I gotta write my own review of this book about Elvis.

LS: Right, right. It wasn’t a review; it was an excerpt in Rolling Stone.

SB: Oh, an excerpt. Yeah. You’ve also written these essays such as “The Invention of the Blues,” an essay that—if my numbers are right—took eight years to put together.

LS: Well, you know, I wasn’t working on it all that time.

SB: [Laughs] Right. But, what was it like putting that particular piece of writing together? Because the blues are an interesting example of time where it’s within the century, but there’s sort of a murky history that you had to….

LS: Right, to unearth. And since we’re sitting here in Brooklyn, it reminds me of my term in Park Slope and how this essay began with my trudging from my apartment on Saint John’s Place to the Y on Ninth Street with my Walkman and listening to—I had this very big stack of blues cassettes like Yazoo and I was listening to them on this walk back and forth to the Y like four times a week, and I got really deeply into what I was listening to. It became an obsession and I had to hunt it down. The blues didn’t just show up.

“The blues didn’t just show up. Somebody came up with it. But we’ll never know who.”

You read accounts of the blues and it’s all about how they evolved from field hollers. But yeah. Come on. It’s actually a very sophisticated, very specific form. Somebody came up with it. But we’ll never know who that was. The New York Review even made me fudge the line when I said “somebody,” “some person”—they still wanted it to be a collective—not that I deny the collective work. Very important to me. But something as specific as this was hatched by some unknown genius. There’s no other way to phrase it.

SB: You’re now also writing about music in your next book. I should mention here that it’s focused primarily around the sixties and The Velvet Underground. Could you share a bit about it? How did this project come about and what can you share?

LS: Well, the backstory is that I had a contract that I got myself into somehow. [Laughs] I almost wanted to say it happened without my knowing it. But I ended up with a contract to write a biography of Lou Reed. It was set up actually by Andrew Wylie, who was Lou’s agent, but not mine. But I did wind up with this contract, and I did realize I didn’t want to do it because, well, for one thing, I’ve never wanted to be a biographer. The idea of interviewing kindergarten classmates just freaks me out.

SB: [Laughs]

LS: But it was a lot of money, and I had already spent some of that money.

Transitioning came to my rescue, and my agent made a swap. Two books for one. Number one of the two books is I Heard Her Call My Name. And this is number two. The way I described it officially is “the Velvets and their times.” It is about the Velvets, but for me it’s even more about New York City in the sixties, which is something I’ve been fascinated by for a long, long time. It’s something I saw sidelong as a child, and then saw just as it was beginning to go away, in my first two years of high school, commuting, which began in September ’68. It was a completely different city, the sixties, than it was in the seventies. Most of my friends came to the city in the seventies. The sixties were a kind of magic time.

“The sixties were a kind of magic time. The sculptors and the composers and the poets and the speed freaks and the peace marchers and the civil rights marchers—they all knew each other.”

It was a much, much smaller world than anybody today can really imagine. And people like the sculptors and the composers and the poets and the speed freaks and the peace marchers and the civil rights marchers—all of these people were, how many, a hundred, two hundred people? And they all knew each other. It’s remarkable. And it was a kind of openness. It was the city where you could find Igor Stravinsky in the phonebook, think about it.

SB: What do you think that world—as you’re diving into it—says about the now?

LS: Well, I mean, that culture had to die and be reborn a few times in between. It seems at such a drastic distance from today. I mean, in the seventies it was much clearer. We were living in the ruins and somebody bought up all the ruins and reconstructed whatever had been there, and made them expensive. But the sixties, which was this magic postwar moment…. It was the peak of American prosperity. The peak of American liberalism. You already had the crazies, you had the Birchers, et cetera, but it was still the peak of American liberalism. The Voting Rights Act, the anti-poverty measures, all kinds of civil rights legislations happened then.

“Everything seemed groovy for a little while, and then it all went to shit.”

And, and right up to and including Roe v. Wade, it seemed like we were winning. Then this heavily militarized reaction set in some time later accompanied by the real estate— But, you know, I’m not going to go into writing you a conspiracy theory wall chart here, but it’s heartbreaking. It was a time when people actually genuinely thought that we don’t maybe need a revolution because we’re on the way to liberation through the system, and everything seemed groovy for a little while, and then it all went to shit.

SB: Do you think any of that spirit can return?

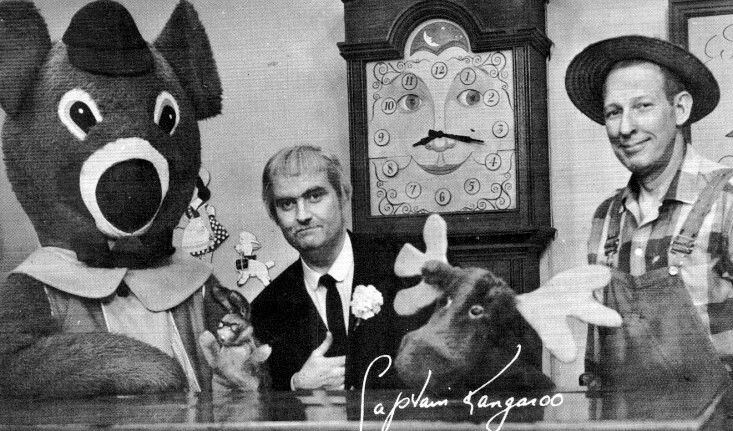

A 1961 promotional postcard for the television show Captain Kangaroo. (Courtesy The Kellogg Company)

LS: Well, you know, you can try to animate within yourself or your friend group or whatever. As far as it having much impact on the culture, that seems dubious because the circumstances are just so different. There’s the money angle. There’s the fact that everything is refracted into a million pieces. It was the last era of the big tent when everybody was paying attention to— Everybody watched Walter Cronkite. Everybody read Life magazine. Everybody listened to AM radio.

There was no segmentation by race, creed, gender, religion, sexual persuasion, any of that. Everybody attended to the same culture with their own…. Then, on the side, you’d be reading Genet or whatever. But you still knew about Walter Cronkite and Johnny Carson and Captain Kangaroo. And now, I don’t know whether anybody on my street attends to the same culture as I do. At all.

SB: [Laughs] It’s so—yeah—segmented.

LS: Yeah.

SB: Lucy, thank you. This was such a pleasure.

LS: Great. It was fun. Thank you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on February 23, 2024. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo based on a photograph by Bob Krasner.