Episode 142

Jay Osgerby on Imbuing Objects With Meaning

The British designer Jay Osgerby believes in designing rigorously simple objects that are deeply felt and, hopefully, appreciated for generations to come. As the co-founder of the London-based industrial design studio Barber Osgerby, Jay and his partner in the firm, Edward Barber, emphasize experimentation, innovation, and a material- and craft-forward approach in all that they design, from products and furniture to architecture and interiors. Osgerby exudes a genuine curiosity for how things work and are made, and he often takes the long-view as a designer, carefully considering the importance and responsibility of what it means to be a good ancestor.

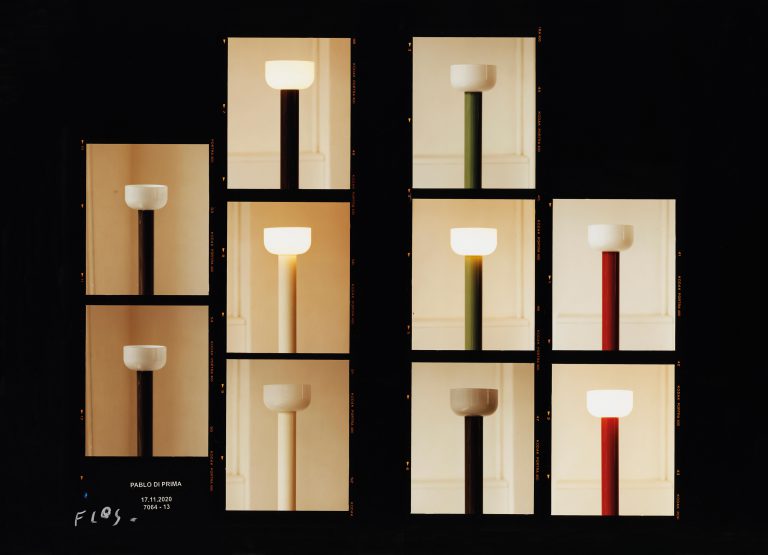

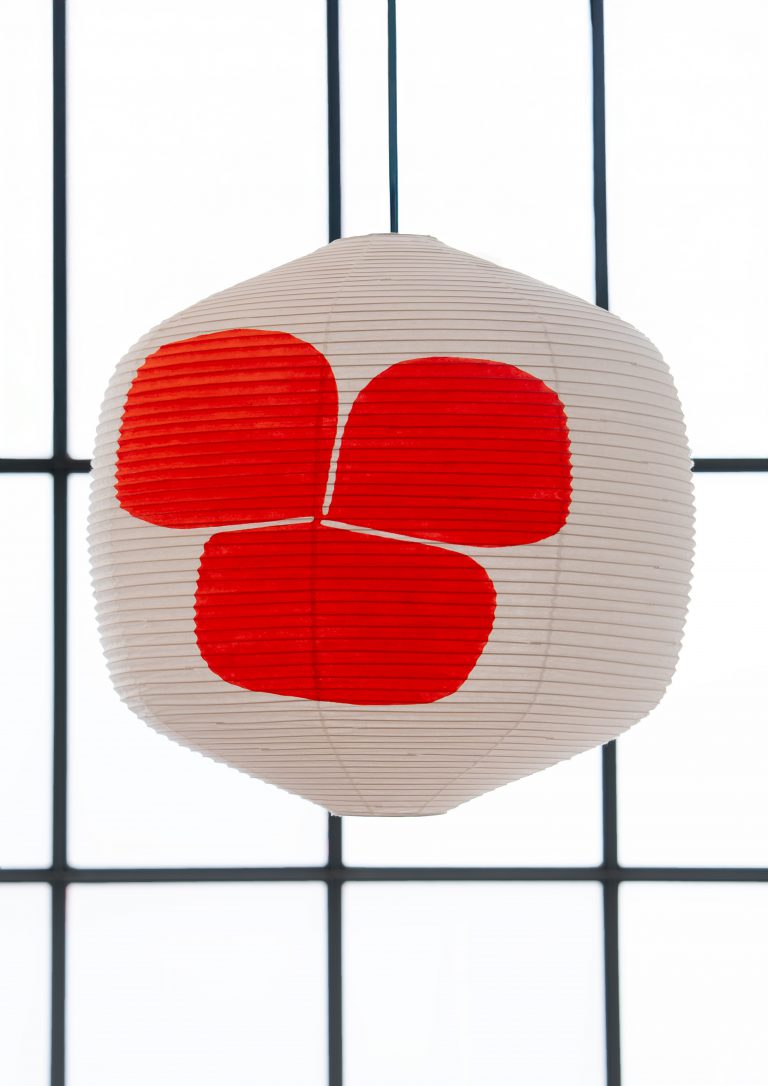

Across their nearly 30-year history as a studio, Barber Osgerby has taken a “fewer, better things” approach (in line with the ethos of curator and scholar Glenn Adamson, the guest on Ep. 50 of Time Sensitive). They have become known for their pragmatic, matter-of-fact designs rooted in poetic simplicity, material rigor, and, more often than not, a subtle social agenda. The firm’s rich and varied body of work includes the 2012 London Olympics torch, a commemorative £2 coin (2012), a Victoria and Albert Museum installation for BMW (2014), Vitra’s Tip Ton chair (2011), and paper lanterns crafted by Ozeki & Co. in Gifu, Japan, to name a few. Each project exudes clarity, calm, and consideration—and always a sense of character. The majority of their pieces—including two that Spencer lives alongside at home, the Loop table (1996) for Isokon Plus and the Bellhop light (2017) for Flos—are designed for everyday use and espouse a sense of timelessness.

On this episode of Time Sensitive, Osgerby shares his optimistic views on A.I. as a means toward more people engaging in craft and handwork; considers what his years inside factories and surrounded by craftspeople have taught him about human ingenuity; and reflects on objects as vessels for memory, history, and soul.

CHAPTERS

Reflecting on the long-view legacy he hopes to leave as a designer, Osgerby pinpoints a few of the projects he’s most proud of, and revisits his foundational maker family history.

Osgerby defines what makes for good design and recalls how childhood visits to an Oxford museum inspired in him an early appreciation for objects. He also shares a glimpse into the design process for a few standout Barberg Osgerby projects, including the 2012 Olympics torch and the Bodleian Libraries chair (2014) for Isokon Plus.

Osgerby discusses how he and Edward Barber choose which new projects to take on. He also considers how technological shifts, including the rise of A.I., further refine and enhance his tactile design approach and respect for all things analog.

Osgerby talks about what he’s learned from collaborating with manufacturers, factory workers, and craftspeople and describes the satisfaction of “collectively creating something of beauty.”

As his firm approaches its third decade in 2026, Osgerby looks to the future and shares what this milestone means to him.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Jay. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

JAY OSGERBY: Hello. Thanks very much for having me.

SB: I wanted to start just by acknowledging that, for years now, all these Time Sensitive interviews have been conducted under the monastic glow of your Bellhop table lamp from Flos, here. It’s on the table in between us. So, technically, you’ve been present in all of these interviews.

JO: Well, I thought actually, you’d bought it for me, especially. [Laughs] I’m a little disappointed it’s been here all the time, but I do like the fact you’ve got a Loop table upstairs, as well.

SB: We record these in the basement of this home, and upstairs in the living room is your Loop coffee table. It’s one of my favorite furniture objects in our home.

JO: Oh, thank you. It’s great. It’s very nice to come here, actually, because it felt like home straight away to me.

SB: Oh, good. Well, it’s interesting because soon, it’s not going to be our home. My wife and I are moving, actually, this Friday. This is our grand finale interview of Time Sensitive in this space before we’re in a new space and recording in a new studio next week. In a way, it’s special to bring the designer who created some of the hominess into this space for this last interview.

JO: Well, we should call it “Just in Time,” then.

SB: Just in time. [Laughs] All right. Well, let’s begin with a big provocative question.

JO: Oh, God. Okay.

SB: Sip of coffee.

JO: [Sips coffee]

SB: In a recent magazine interview, Edward Barber, your partner at Barber Osgerby, and you pondered whether having an ancestor who was a designer might be “shameful.” Or that’s what the writer wrote.

JO: Oh yes, that’s right. Yeah. I think I described our business as being perceived in the future as the equivalent of having a slave trader in the family, for example. Somebody who… Or a career or somebody who was so involved with a system which was, by future standards—or by any standards, I suppose—noncompatible with the ethics of life.

SB: Such a big question to think about because a hundred years, two hundred, three hundred, four hundred years from now, it’s like, what is your legacy? I guess this was the big question I wanted to ask as—

JO: Yeah, thanks for that, by the way.

SB: [Laughs] As a designer, what do you hope to leave behind? What do you hope you’re remembered for?

JO: In a way, I think this comes back to the way that one’s career can be subdivided into epochs or periods of time. Part of me wants to say that I haven’t yet done what I hope I’m remembered for. I think that there are things that we’ve done over the years—which I’m incredibly proud of—in the studio and some of which will physically exist. Over the years, we’ve done some really crazy things, like we’ve designed currency. We designed a two-pound coin that was in general circulation. These things exist.

SB: That’s probably your most mass-circulated object, I would say.

JO: Well, technically it was… Yeah. I think they made 18 million of them, which, by some margin is by far the most-produced thing that I think we’ve ever done. So, we made 18 million of them, and it was really amazing to get them in your change when you bought something.

I think your question was, of the things that have been designed, what would be remembered? I guess the Olympic torch is another one. I think, on the whole, projects that we’ve done, that I’ve worked on over the years, which have a wider symbolism or wider meaning than purely something to buy, like a two-pound coin you don’t choose. Olympic torch, no one had the choice to have that. That was the object that represented the country. We’ve worked on installations for the Victoria and Albert Museum, for the first [London Design] Biennale. These are sculptures that represent a place and a time and other things. They, for me, have more meaning, I think, than a casual product, on the whole.

SB: We’ll definitely dig into the philosophy that underpins your practice, but I would say, in essence, being a good ancestor is part of what you’re trying to leave behind by making things that stand the test of time and, by reason of that, are sustainable. Would you agree with all of that?

JO: Well, yes, I would. The other thing I think that’s actually interesting, in terms of situating me in the world, is that I grew up in a time where I felt like I was surrounded by time and memory and an ongoing connection to my ancestors, actually. I had all my grandparents when I was young. They were still around. They were pretty young, and they carried lots of stories. The Second World War was very present in my family, in the seventies. I was born twenty-five years after the end of the Second World War.

SB: Right. Just after the moon landing.

JO: Yeah, exactly. Two months later. Both my grandfathers had seen very serious active service and that was definitely around in our families. It wasn’t really spoken about all that much, but it was present. There was a really intriguing discussion in our family about the past and about what people did. I was very aware that everybody that was talked about did something or made something. So, my dad’s side of the family, they were Swiss and they had been watchmakers and they had been—

SB: Perfect for…

JO: Camera makers.

SB: Perfect. Let’s talk about watchmaking.

JO: I was just born into this soup of history and storytelling about making. When we’re now talking about how to be a good ancestor, I have some really interesting role models.

Like one guy, this one great, great, great-grandfather, he was actually a chemist in Switzerland, and it was around the time that photography was exploding as a new medium. He developed the chemistry that enabled fast film to be used and processed. What that means is, until that point really, so much photography was just done in studios and people had to sit still for bloody ages and they had metal frameworks that held their arms in the right position so they could have a nice portrait. He created the chemicals, which enabled them to take fast shots in daylight.

He had a camera company, but he took tons and tons of photos just to see if his film was working. It became one of the first examples, really, of street photography, because he was just going out and shooting people: like kids skipping, people jumping into the lake to see if the water would be suspended in the air rather than just blurring. Those experiments and that legacy of thinking and making and exploring were foundational to me as a child.

SB: Another of your ancestors was a carriage-maker, right?

JO: Yeah, that was my dad’s granddad, Fred Osgerby. Famous Fred Osgerby, freeman of the town of Beverly in Yorkshire. He used to make hansom cabs and they obviously had wheelwrights and stuff. So, consequently, we ended up with all this stuff in our shed that was tools from 1920 and stuff. I guess so many of those skills were lost by the invention of the internal combustion engine. I can’t really be bitter about that, but so much of the woodworking skills were lost in that era.

SB: I’m struck that the Second World War created so many fractures, and yet, this tradition of making, we could say, persisted and led all the way to your path today.

JO: Yeah, of course it did. But I suppose that’s one of the benefits of growing up in a small town surrounded by family, because those stories endure, and it wouldn’t have been the same if we’d been disassociated or we were living in a different place. So those narratives… I find them really interesting. Not just the faculty of being able to produce, to make, but also the ability to tell stories is so important in our world of design, creation.

SB: Extending out of storytelling, ancestry, etc.: What, to you, makes good design? Or what is good design?

JO: Well, that’s an easy one, isn’t it? What makes good design? What is good design? Fuck.

SB: [Laughs]

JO: One of the interesting things that happened to me last year—this is a complete sideswipe, by the way. I was in Tallinn, [the capital of] Estonia], and I was doing a lecture there and the hosts took me to the Design Museum in Tallinn. I don’t know if you’ve ever been, but it’s actually a really beautiful design museum. That part of the world, in a way, was almost the birthplace of plywood, which was interesting to me, obviously, with the Isokon connection. But I was there with the host and a couple of other people. And what struck me was when we went into the twentieth-century gallery, how certain objects really resonated with everybody. It made me realize that, of course, as part of the Soviet Union, they’d had a real scarcity of supply of actual things.

The things that they had were common, and they shared them and they would talk about, I don’t know, let’s say it was a soap dish, but it was the soap dish that everybody had. If you were lucky enough to have two or three bathrooms, you’d have two or three soap dishes. There’s something there that taught me about the importance of scarcity and production, because with scarcity comes meaning more so than overproduction.

You also get the ability, then, to develop narratives and memories around objects which are scarce. Especially in this sense when it’s a collective memory, it’s really powerful. In terms of good design, what do I think? Of course, studying in the eighties and early nineties, we were very much swinging between the dichotomy of Dieter Rams and [Ettore] Sottsass. You’ve got Memphis fighting with Rationalism. We were taught very much that, obviously, the rationalism, effectiveness, cost focus, available for everybody was the answer, and that still is generally what most people would say. But I think there’s something that’s overlooked then. We used to talk about an object requiring a soul, something that spoke back to you, something that could maybe unveil new things to you, over time, so that an object which you fall in love with somehow—rather like a person—becomes more meaningful over time. I think that’s true, but I also think there’s one other thing that’s missing, and I think it’s the idea of somehow carrying memory in objects and how we do that. Because I think when an object carries memory and that’s part of its soul, then I think you’ve really got something special, something really wonderful, which somebody will fall in love with and want to keep for a very long time.

SB: Totally agree. The way objects tell stories. I’m a little spoiled in that I get to interview a lot of the people who design the things in my home.

One other definition that you’ve said in the past, which I love, is that good design is “something that listens as much as it speaks”: this idea of listening in an object, basically making room for, allowing multiple uses, maybe even multiple interpretations.

JO: Well, I think that’s interesting, looking at the Bellhop lamp, which is actually why I’m in New York. I’m here for Flos to talk about the family. But whilst we’re on the subject of objects, the Bellhop lamp [was] one of those projects that could only happen at a particular time. It happened at a time when battery power enabled us to be able to have a chargeable lamp, which, in turn, enabled us to create something that didn’t need to be plugged in all the time. This, in turn, enabled us to be able to create an object that you could walk around with, that you could take light with you. That plays with the collective memory of candlelight and portability of a candle, the little candles that you’d hold to walk up from a communal space up to your bedroom.

Even a hundred years ago, two hundred years ago, it’s a very common archetype, and it’s a really well understood way of using something. When I’m talking about memory, it enables us to trigger memories, the collective memories, the ancient memories of being able to be mobile with light and take light with you, which on one hand is functionally great. But of course, in a much more profound way, [it] makes us feel safe.

SB: Connects to your 2012 Olympic torch, too.

JO: Yeah, exactly. Slightly less dangerous than running around your house with a gas burner. But yeah, it’s true. The 2012 torch, of course, it had to have collective meaning, and we played on collective memory and storytelling, but it needed a level of, I suppose, symbolism, partly for people to engage with it, but also partly because the torch relay was so long—seventy days—we had to give the TV commentator something to talk about. So, it had to have layers of meaning, and there were so many in that project.

SB: There’s a certain sense of timelessness to your designs. I know this is such an overused term, timelessness, but I think it does really connect to what makes good design. I’m sitting next to Noguchi’s Prism table, which I know, for a benefit auction in France, you did this really wacky, orange, kind of wild version. But I think that there is something really special about how a design can stand the test of time, how a design becomes timeless by reason of its material and design integrity. It’s the way that it’s put together—it almost feels inevitable. Oftentimes, it disappears. You almost forget it’s there, because it just fits in.

JO: Yeah, it just… Well, actually one of the things that I suppose got me into design in the beginning and thinking about that is as a kid [was] growing up in the countryside. We were quite close to Oxford, and there’s the most amazing collection of anthropological objects called Pitt Rivers Museum. I don’t know if you’ve ever been there.

SB: No.

JO: You must go the next time you’re there. What was fascinating about that, even to me as a kid, was that the collection, it wasn’t a curated region by region or timeframe by timeframe, but it was more about object types. So, what you could see was, for example, a hammer, or a spoon. They would be collected.You’d have something that was used for those functions in each of these vast cabinets. It was really easy to see how different societies across the world had used their resourcefulness to create something to solve the same problem, but all in a different way. All of these objects had something about them. There was obviously thought, there was years of evolution of hand work in them, so that the forms had become perfect representations of that culture. I know this is a departure from the Noguchi side table, but there is something about that level of thought and evolution of [an] idea that gives an object the right to exist. It’s just right.

SB: I love that you brought up Oxford, because I wanted to mention a couple examples of Barber Osgerby designs that I think really stand out in this way that you’re talking about. One of them is the Bodleian Libraries chair, which you did for the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford. So, that’s kind of a fun full circle.

JO: Yeah, that’s true. There have been a couple of projects over the years that Ed and I have really gone for. Often, they’ve been competitive. The Olympic torch was incredibly competitive. The Bodleian chair project was also a competition, but it was something that meant something to both of us. Obviously for me being a local lad, it meant an awful lot to me. Putting that aside, the commission itself was quite incredible, because it is one of the oldest—if not the oldest—library in the world. They’ve only had three chairs, I think, since seventeen-something.

SB: Yeah, across three hundred-plus years. That’s wild.

JO: Yeah, so that was quite a lot to live up to. Again, of course, like all of these things, what makes these projects so amazing is that the requirements were so crazy. It was like you have to create a chair that sits in this incredible architecture where a reader can sit for twelve hours a day. Then we actually studied, of course, what the readers are reading, and they’re not reading, like, paperbacks. They’re reading these massive books, which are maybe, I don’t know, three-foot wide when they’re open, and they’re having to wear white gloves, and they need a really interesting range of movement to be able to turn the page. So, I’m sort of demonstrating this for your listeners.

[Laughter]

Of course, having just done the Tip Ton chair for Vitra, or a couple of years before, we’d already established that some sort of movement was helpful to try and promote circulation and help you concentrate by oxygenating your brain. So, we took some of the good bits of the Tip Ton chair and incorporated them into the Bodleian chair, as well. [It’s] quite a big oak thing with a leather seat. It’s constructed like a drum. It’s super comfortable, but when you lean forward, the chair tips up so you can actually move, but without [a] mechanism, because you don’t really want office chairs in the Bodleian Library. That really wouldn’t do with it.

SB: No, and you’re designing this thing into this three-hundred-year history.

JO: That’s one of the things that I love most about what we do, or design generally, is that I think time is this thing which is a layer that sits over us every day. It’s like in the old days before digital radios: how you had a band on the top of a radio and it was like FM, medium wave, ultra-high frequency, whatever it was and you tracked that. In a way, that’s sort of how I visualize [myself] in time. You can track left and right to pick up different frequencies and different energies and different references. I think that’s one of the most lovely things about creating anything: how you borrow from the past, think about the future, but create now.

SB: The other design I wanted to bring up is an earlier one. The Portsmouth bench from 2002 for the Portsmouth Cathedral, I think connects very much to the Bodleian Libraries chair.

JO: Yes, it does.

SB: Share for the listeners a little bit about this bench, which, I know, it might sound dull to talk about a bench, but to do that for the Portsmouth Cathedral, this building that dates back to 1180.

JO: Well, the things that you’re talking about are actually really interesting. We don’t often talk about them,.There’s the time aspect. I think it was a time when that project was quite early on for us. We did it with Chris McCourt from Isokon, with whom we’ve done so many great things. In a way, that project emphasizes what I was talking about before, about functionality. If you’re designing something for an ecclesiastical interior, especially in the U.K., there’s something about less being more, in the sense that we’re talking about the Church of England; we’re not talking about the Catholic Church. So, bearing in mind Henry VIII, we had to do a really good job of creating something that was quite pared down and not too ornamented, which sat really well with our design aesthetic at the time.

Again, using oak was a perfect material because most woods, but certainly oak, has that incredible ability to almost vitrify over hundreds of years. You’re creating something that could well be there in five hundred years time. There’s something about the materiality of oak, which has some sort of frequency or resonance. When you hold it or touch it, it somehow talks back to you physically, as well as in the form of it.

Aside from that, the brief was interesting because it was, I think initially anyway, for the choir stalls. It was for the choirboys to sit on. Again, you can imagine rows and rows of fidgety, fidgety boys—and girls—waiting to stand up and sing. There was a visual quality of the brief, and the answer was something that needed to sit at a place in time that was ambiguous. As far as I’m concerned, they could well have been designed at any point after the Arts and Crafts movement—if not before, actually. So, it was about choosing something or creating something that we loved, but that we knew could sit anywhere on that radio band.

SB: There’s something about your studio that I think could be what the craft scholar Glenn Adamson calls the sort of “fewer, better things” approach. Even more so in recent years, you scaled this thing up, and now it’s almost like a rightsizing moment. Could you talk about that? How you’re doing less work now, by choice, and how you decide which projects to do? There’s this intentionality and restraint to the way you operate.

JO: Yeah, that’s interesting.There was a period of time when we were producing a lot more, and in a way, maybe this comes back to the time thing. There was a period of time—certainly I felt this—where life was too short. There were various things that have happened in my life that have given that more meaning, needing to really take advantage of every minute. I think that was reflected in the work. Suddenly, we actually became highly productive. But I feel like maybe we’re in a new chapter where things are generally more thought through, considered, and I think, more than ever, we have to be certain that the object and the ideas justify the production of something. I don’t know whether that’s just a natural part of getting older, where you become more reflective and look for more meaning in things. But it’s an interesting observation. It feels like the studio is pretty busy, but actually, I think there’s a lot of energy that’s going into thinking.

SB: I think you’re also coming of age at this time in which the climate crisis wasn’t something people were talking about, back in the late eighties, early nineties, so much. It was just bubbling up. Bill McKibben was just publishing his early work. I would also say, yeah, naturally, you reflect, but I think in terms of globalization, the cost of production, the way things are made, A.I.—We can get into all these subjects—but this is all happening at the same time as your time is evolving.

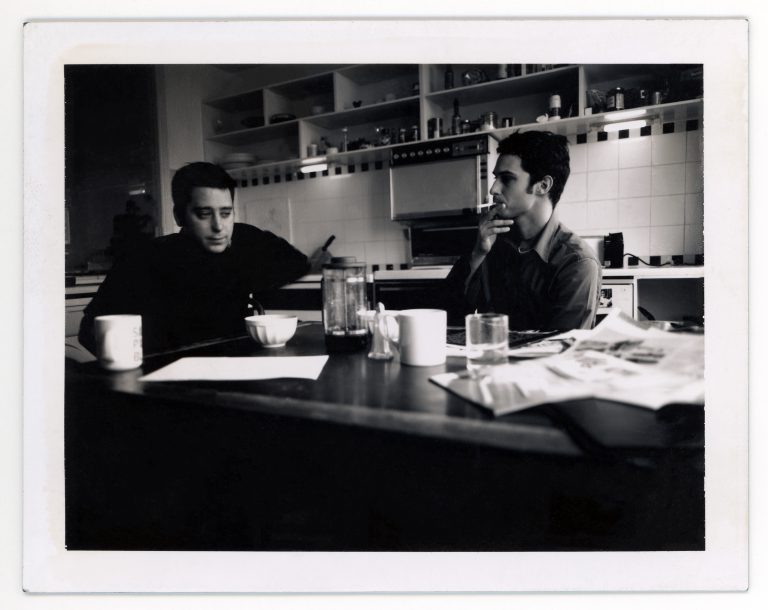

JO: Yeah, that’s true, actually. I think we’ve always been, as a studio, conscious that we want to make good stuff. In the early years, we made the difficult decision as young, kind of penniless student-strike-designers that we didn’t want to just take on any brief from anybody. We were very lucky early on that we started working with Isokon and with Chris, because he taught us a lot about making, and also the pace of working with a small producer like Isokon.

SB: And simple, humble materials, like plywood.

JO: Simple, humble materials, yeah, and being so intimately connected with the production. I mean, they had bag presses and lathes and pillar drills and all the stuff that you could use. We rented a small space near a workshop. We were in there the whole time. I think that was probably more important than the RCA years, because we learned so much about what goes into making something. So, that was great. But those years were a self-imposed restriction on what we produced, because we dreamt of working with the great producers. We wanted to work with Flos and Vitra and those people, so we waited and waited and waited. Then it finally happened, of course. Even back in the mid-nineties, people were already switched on to the fact that we are not here to damage the world; we’re here to actually make great stuff. And that’s been consistent with them over the years.

SB: Next year marks thirty years of Barber Osgerby. What does this time marker mean to you, and how do you think about the role of the designer evolving in that time? What’s changed since you began in 1996?

JO: So much has changed. I don’t even know where to start with what’s changed. I’m not talking about our studio, particularly, but the landscape has changed so radically. There are some really exciting things now that are present. I think it’s very typical for an older person to be critical of the world, but it’s totally not about that. It’s just really different. There was a lot of effort that went into getting work out then. So, to give you an example: We designed the Loop table originally for nobody, particularly.

SB: It was for a restaurant, right?

JO: It was for a restaurant, yeah, and the restaurant didn’t have the budget for it, so it sat on the shelf as a card model for a couple of years, until a friend said, “Oh, that’s interesting.” What’s interesting about the Loop table is that it personifies, for me, the intersection between architecture and furniture, because even as a model, it was ambiguous. Was it a pavilion or was it a table? What was it? It could have been either, actually. But it was always supposed to be a table.

Of course, in 1996, you had to get a camera from somewhere, take some transparencies, put the transparencies in an envelope, send them to magazines and hope, keep fingers crossed and chase these things up that they were received, to try and just get your work out and about. What’s interesting about that I think is that the sheer friction of trying to be a designer in those days was actually quite a good barrier to entry. If you wanted to be a designer, you really, really, really had to want to, because it was really hard work to get your work out in a way that. It’s so different today, because you can have an idea and it can be rendered on Instagram in twenty-five minutes, and it can look real.

SB: You can have thousands of people responding to it.

JO: Yeah, and they can love it, and if they love it enough, then you can make it, which is wonderful, on the one hand. But it comes back to the thing I was saying before about the importance of scarcity, because I think what happens is there’s an oversupply. We’re all bombarded with an oversupply of visual stimulus. What happens now is, when you have a really brilliant idea for something, very often it’s been done in a form or it’s been claimed visually, even if it hasn’t been realized. That’s super off-putting.

I’m sure that, for the young guys and girls today who are wanting to be designers, it’s incredibly difficult to be able to find your own position, because it feels like the entire landscape has already been well-trodden. I do have a real concern for them. Because, actually, design is oversupplied as an image—not necessarily the actual thing.

What has changed over the last thirty years is that, as a graduate and as a young designer, you had to really try and find design. You could buy a couple of magazines. I worked in a newspaper shop as a teenager, actually. It was my great uncle’s shop, and I managed to persuade him to get a Blueprint magazine, knowing that nobody in my small town would really be interested in Blueprint magazine. But it enabled me to read it, in my tea break. But finding design was difficult. I would come to London as a slightly older teenager and go to see Ron Arad’s shop or go to Paul Smith’s shop and try to find design. I remember how exciting it was to come see the Lloyd’s building when it was first built. I actually hitchhiked to London to go and see it, just because I wanted to somehow be near design—that sounds really sad, doesn’t it, now?

SB: [Laughs]

JO: Coming from a small town, it meant everything to me to be able to have that kind of contact. There were a few places, late eighties, early nineties where design existed, but they were few and far between. Of course now, good design is—we would’ve understood it then—ubiquitous. It’s everywhere. You can buy it in every shop, you can buy it on so many websites. Of course, that’s wonderful, because people have access to affordable design, but we run the risk of creating something where there’s just so much sameness.

SB: Yeah, and no meaning.

JO: And no meaning.

SB: Back to what we were talking about, having objects that are imbued with meaning, with story.

JO: Yeah. That’s one of the reasons that I’ve enjoyed working with Kreo, which is the—

SB: Galerie Kreo.

JO: Galerie Kreo. It’s like coming off the motorway and going onto a small road into another place where you can take time to create fewer objects that have more meaning. That’s the antithesis of the [Dieter] Rams way of thinking and Modernism, because we are creating a few things for a handful of people. As a creative mind, it’s a playground for experimentation. Actually, being able to imbue meaning into objects that don’t necessarily make sense to hundreds of thousands of people, but it makes sense to eight people—for me, that’s one of the most interesting places to work at the moment.

SB: I wanted to bring up just the fact also that A.I. was not really a conversation in 1996.

JO: No, it was the internet.

SB: Yeah, barely. I mean, 1996 was also a moment in which you were just creating this table, doing your first restaurant. I think it was Tyler Brûlé, right, who saw and published the Loop table?

JO: That’s correct.

SB: That was sort of your first media moment. To think that things felt—

JO: I would just add, though, we did send the transparencies to Wallpaper magazine after a very funny conversation when Wallpaper phoned the studio and we kind of hung up. We were like, “A magazine about wallpaper? That’s a hundred percent not what we are into.” Luckily, they called back.

SB: [Laughs] Everyone needs their early press moment, just some way to launch.

I wanted to bring it back to this moment, thinking about how everything felt so analog then: photography for the print magazine. But then, of course the internet happens, the iPhone’s created, smartphones are in our pockets, and now with A.I… I don’t know that A.I. is going to “change everything,” like everyone talks about, but I do think it is going to, and already has had, this incredible, transformative impact on the way things are made, on the way we consume information, probably in how some people have discovered this very podcast, just how digital life moves. Probably even a conversation to be had with an A.I. expert on time, the relationship to time.

JO: I can talk to you a little bit about that because, whilst I spend a lot of time working with Ed on furniture and products, I have my head in a number of other things. In fact, Ed and I started a company called MAP in 2012. In fact, we started a couple of other studios with other disciplines because… Well, there’s a whole other story there, but I think we just tried to create college again around us. But one of the departments in this new college that we created was a very technologically focused studio called MAP. And MAP does a tremendous amount of work with IBM and worked on IBM’s quantum program, including Series/1. In fact, I’m probably going to go to Yorktown on Thursday to go and see them.

I’ve also recently been working on A.I. products and services for a client, but through MAP. I have to admit, I find it fascinating. I love the fact that I can be working in Murano with Venini on a project with Kreo one minute, and I can be talking about the future of humanity through technology the next. It’s that type of diversity that keeps me interested and engaged and thinking. And I think the way to think about A.I.—and actually technology as a whole is—it’s optional. As I said before, about the idea of coming off the motorway and going onto a side street or side road to find things, we always have the option not to engage with it. It’s there for us as a tool or another layer, as we were saying before, but I think we always have the capacity and the option to live in an analog environment.

SB: Completely agree.

JO: Switch off.

SB: Completely agree.

JO: Yeah.

SB: That’s why I think A.I. is not going to change everything. I think it will change a lot of things, but it’s how we engage it. I mean, even Sam Altman has talked about things like human creativity, attention to detail, the human touch. In our age of A.I., these aspects of craft, they’re not going to disappear. In fact, they’ll probably become more important, not less.

JO: I think that they really are essential. Actually, if ever there was a moment to think about what a product means, it’s when you’re introducing a new technology to people. Because people are terrified. They don’t understand it. They don’t understand how to interact with it. I mean, this is a thing that doesn’t really need buttons. It doesn’t need the classic kind of modes of interaction that we grew up with. We’re talking about: How do you create a form and a materiality that actually enables a character to coexist with your life in terms of an A.I. agent? What does that look like? That’s what I’ve been thinking about. It really is fascinating. It brings reality to the notion of objects and meaning, doesn’t it? The other thing, of course, to think about, we’ve spoken about how important memory is in association with objects, but what does that mean in an era of A.I. when memories can be created, recreated and reconstructed and constructed from scratch? There’s so many interesting things to explore here.

SB: I mean, these people with aging parents who have them get their voices recorded, the idea that your parent can speak to you from the afterlife, it’s wild. [Laughs]

JO: I mean, I personally would stick to the medium there. Just, what is it? Cross the palm with silver and actually engage with the real… I love this part of what’s happening at the moment. Let’s just talk about it from an industrial-design point of view. I had this conversation with my kids when we were arguing about when they were going to get a mobile phone. They said, “Well, how old were you when you had your first mobile phone?” I was like, “26.” [Laughter]

The fact is, during that period, so mid-nineties to the early 2000s, think how many form factors and shapes, and God knows what, there were for mobiles, cell phones. It was a whole candy store of options and interactions. It was a real playground for industrial design at that time. Here we are again, this is it: We are going to have the same thing happen, because it’s going to be a decade probably before the form of A.I. gets consolidated into a form factor that’s universal, as we have with a phone now, so it’s an open season for industrial design with A.I. Which in itself is really interesting. But putting aside the form and the materiality of the task, how we as designers enable this new intelligence to coexist with people, in people’s homes, think about how diverse humans’ homes are across the planet, how do we find a universality of meaning in this new paradigm? It’s fascinating.

SB: I mean, we talk about “screen time,” but really we’re only twenty, thirty years into the computer as we know it, and not even twenty—eighteen years into the iPhone.

JO: Yeah.

SB: It’s wild to me. If we take a long view here, in the far-off future, they’ll be like, “Oh, that was the ‘Screen-Time Era.’”

JO: It’s true. No, you’re right. It’s like the typing pool in the office. It’s going to just seem so out of date. I think what’s interesting about this new world of voice-activated intelligence is that we will be liberated from looking down at screens, and we’ll be able to look up again at the world. We’ll actually be able to look around us and experience the real world that we live in again, instead of what they call in some parts of the world “smart walking,” which is just walking with your phone and then being hit by a car. I do believe that one of the great things about this new paradigm is that it’ll make people… It’s actually more human than the way that we have been interacting with devices. That’ll enable us, consequently, to be more human in our environments.

SB: Yeah, slow down, engage the senses. Pay attention.

JO: Yeah. And look—look at the world.

SB: The critic Rowan Moore has written about Ed and you, how it’s when you talk about making things that you really come alive.

JO: Oh, really?

SB: He wrote this a while back. I think it’s fair to say that, even though you’re not necessarily makers yourselves, in the traditional maker sense, you’re obsessed with making.

JO: Mmm. Yeah.

SB: It’s through materials and manufacturing that the work you’ve done has really come to life. Process-wise, when you’re making something, or designing something, Iit’s a process of model making, it’s a process of learning how the thing would be manufactured. It’s going to factories, it’s learning about machines. That’s everything when it comes to your work, in some sense.

JO: I think you are quite right about that. What I’d say about that is that our experience of creating objects has been a continuation of our learning. Part of that continuation of learning has been that sometimes when we work on projects, you’re not always clear on what your constraints are. It’s when you get the opportunity to interact with the makers, whether it’s a craftsperson or whether it’s a semiconductor factory, you understand another level of complexity. We’ve never worked in isolation. Even at the beginning, it was two of us. We started our practice as a collaborative practice. I think one of the successes of our studios has been the fact that they were all created to collaborate. We are not pointing and saying, “This is how it has to be.” We’re saying, “This is how we see it. How do we get there?”

When we talk a lot about the making process, it’s very often to do with the fact that we’re listening to people who really understand. It’s that collaboration that helps us create a beautiful object, on the one hand, but also continues this collegiate style of learning. I think, so long as there’s an opportunity to learn in what we’re doing, we’ll remain engaged. At some point, when the learning stops, that’ll be when it’s time to stop.

SB: How would you classify or think about your “manufacturing time,” or your “factory time,” if I could call it? You’re somebody who has spent an incredible amount of time around machines and craftspeople and different forms of maker.

JO: Yeah, the most extreme things, really, when you think about it. So, how do I feel about that? I feel like it’s the best bit of the job. For me, spending a day with a craftsperson— I can think of so many, real diverse characters, as well. Really diverse.

There’s another thing, of course, which is that sometimes the manufacturers are really grumpy. Guys are really like… They don’t want to help. They don’t want to go the extra ten percent. So there’s something in there, as well, about being coercive. Not coercive, that’s the wrong word. Persuasive.

SB: Convincing.

JO: Convincing. Thank you. That’s the word. It’s about having enough energy in the room to try and bring people on—that… Oh, God, I can’t say I believe, I’m going to say—bring people on the journey. [Laughter] That’s so naïf. You know what I mean. Get people to do what you want—in a nice way.

SB: Yes.

JO: The feeling of satisfaction from collectively creating something of beauty that starts the day as not beautiful, and ends the day as something when even the guy who was grumpy in the morning is sitting there scratching his head, and you can see that he’s proud of what’s happened in the day, that’s a real, wonderful thing. I feel so happy that they’ve spent the last thirty years being able to work with these characters. A lot of the characters are people who have been on the scene at the time of our heroes. These are people who have worked with Vico Magistretti, who have worked with [Achille] Castiglione, who have worked with… Just the greats, the people who we looked up to as our heroes. Those people in those workshops, with those overcoats on, are still there. They were young people back in the day, and now they’re the old guys who are really, really wise, and who you learn everything from—especially in Italy. But it happens everywhere. I think the most amazing thing about the position I am in, really, is that I get to spend time with such diverse and interesting people across the world.

SB: Who are such incredible specialists in what they do.

JO: Yeah, who are complete specialists. You can only imagine what the homes are like. I mean, I just look at some of these people and I think, I wish I could see what your chez vous is like. Can you imagine some of these people, such incredible attention to detail, but very often on one thing. They fixate. They’re very, very knowledgeable about one particular technique, in leather, for example, or in, I don’t know, in other forms of upholstery, or in injection molding or tooling. It’s incredible. That’s the best bit of the job. It’s definitely not the bit of where you are getting slapped on the back at a launch of something. It’s not that for me at all. It’s the struggle to get there.

SB: Tell me about your experience in Japan with Ozeki & Co., because I think this is an interesting example in the context of specialists who are really good at making something. This is an old, family-run company that used to make those Japanese paper lanterns—still do; that’s part of their business—but they were reinvented in the forties and fifties by [Isamu] Noguchi, and now you’ve come to work with them.

JO: Yeah, in fact, they were in the studio last week. They were in London. Again, when we’re talking about the heroes—and I know that Noguchi is a big hero for you, as well. He was a sculptor that dabbled in design, but in the most effective, precise way you could imagine. He’s another really good example of a maestro, really, somebody who actually managed to put a sort of soul into everything he did. Of course, the paper lights that you’re referring to are a really good example of him being able to create sculpture in a way that was so different from everything else he did, because most of the work he did was so … it was concerned so much with the weight of the material, the density of the material, whether it’s stone or wood. I think the ability to be able to play with light and lightness, light weightness is a really interesting extension of that in sculpture. Our relationship with them started… I can’t remember when it was. It was a long time ago, actually, and it was because Ed was traveling to Japan, I think, for a project called Japan Creative that we did a number of years ago.

He went to visit them, and obviously we’ve been incredibly familiar with them, partly because of Vitra, the main distribution in Europe, but it was something that we’ve always wanted to do. So, Ed went there and managed to persuade them that it would be a really good idea to do a collection with Barber Osgerby, which is a really great situation. Then we actually had to help them construct a new business model, because they didn’t really have any way of distributing in the U.K. In the way—and this is something that happens quite a lot for us—design as an approach extends into business, as well. We actually had to use our creative-thinking skills to try and figure out how on earth we could persuade this beautiful company to do something new outside of the Noguchi collection, but also that could be distributed in a design world in Europe. It’s been an ongoing relationship for a number of years, and really successful for us, but always so difficult for us to find a language that is meaningful outside of the Noguchi realm, because he did so many lights. He cornered the market, you could say.

SB: [Laughs]

JO: We’re just trying to sort of work around the edges to try and find something that justifies its existence—that’s meaningful, but doesn’t tread on the toes of the master himself.

SB: I mean, it’s not totally unlike that bench we were talking about earlier. It’s extending something into the future, respectfully, as a real evolution, not as a copy.

JO: That’s interesting, as well, because when you look at paper lights, in a way it’s the antithesis of what we’re talking about. You think, well, that’s going to last about ten minutes. But of course, they’re not. They’re made from an incredibly thick Mulberry paper and, as we can all see, they can last for a hundred years. They really do last a long, long time. They’re such an amazingly powerful object to create atmosphere in a space.

Funnily enough, I’m just coming to the end of a big project that I’ve been doing personally in the South Downs, in England, where we bought an old cart lodge, which was originally built around 1750, 1780. Anyway, I’ve got Noguchi lights going really high up in the eaves of this thing. Again, I suppose that’s another example of something [with] the time factor: making something or repairing something to extend its life. We found this old thing that was falling down, a beautiful barn in a beautiful part of the world, but still, it was minutes away from collapsing, and I stupidly bought it.

SB: [Laughs]

JO: It’s been a really interesting process of trying to, I don’t know, architecturally save something. It’s a very fine line between overdoing something and respecting what was there. The oak there—bearing in mind it was constructed, we think, around 1780 or ’90—was already previously used on another building or on a ship, because it always had the cutouts in it from previous use. Thinking about the timeline of that, we’re working on the basis that those trees were probably planted around 900 and something or 10 something. Some of the beams are really crazy. They’ve got apotropaic marks, which are anti-witch marks, which [were] put on structures to ward away witches. So, I’m hoping they still work. They’re going to be enjoying the light, the soft light that comes from some very large Noguchi lights, in a couple of months’ time.

SB: The place I really want to go back to is sort of where we began this interview with the Loop coffee table, which next year, like your firm, will be 30. I love this idea of it being a loop: this sort of full circle, right?

JO: Oh, yeah.

SB: Thinking about your practice as a loop, or time as a circle, how do you think about this moment right now? Perhaps that table in the context of it, but maybe even everything we’ve discussed, your ancestry, going back, the circles of time that we exist in, object-wise or…

JO: That’s an interesting one. When you talk about a loop, immediately, I suppose, I think about an envelope—an envelope of time or a package. Perhaps, in a way, as you say, it envelops thirty years of work that I’m really proud of. It’s been an amazing thirty years. There was a time before and there’s a time to come, but those thirty years were amazing. You’re right, it’s a really nice way of finishing up.

SB: So, what’s next? I know you work on dozens of projects at any given moment. What’s occupying your mind right now as you look forward?

JO: Well, again, I think it’s a lot of this diversity that I was talking about before, really. I think we as a studio are always restless. We’re always thinking about the challenges. As we were saying earlier on, some of the technological aspects are presenting us with the most challenging things, the most challenging questions to answer. That’s what we’ve always wanted to do: answer those difficult questions. I don’t think the future is about a bunch more chairs. I think there will be more chairs, there will be more things, but I think each time that we create something new, we have to really think about why we’re doing it. I don’t just mean from an environmental point of view. I think that goes without saying. I think it’s in terms of legacy, too. I think you need to be careful that everything you do still has that kind of creative energy and authenticity—and longevity. Of course, the more you do, the harder that gets.

SB: Let’s end there.

JO: Yeah.

SB: Thank you so much.

JO: Thanks very much. Thanks for the coffee. It was very good.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on Tuesday, November 4, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Olivia Aylmer, Mimi Hannon, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Ivan Kašša.