Episode 135

James Frey on Designing Your Life to Bring Joy

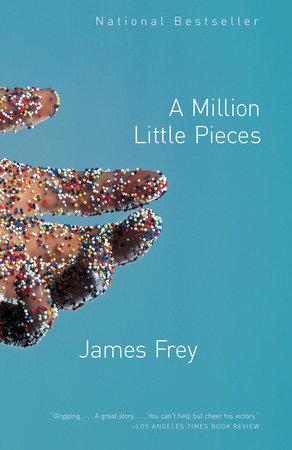

In 2003, when the author James Frey published his first book, A Million Little Pieces—a gut-punch account of his experience with addiction and rehab—nobody could have expected what would come next. Thanks to an Oprah Book Club endorsement, A Million Little Pieces was instantly catapulted to bestseller status, but soon blew up in scandal after Frey admitted to having falsified certain portions of the book, which had been marketed as a memoir. The drama that ensued sparked a media controversy—one that now, around 20 years later, feels petty and misplaced, especially in the context of today’s cancel-culture climate.

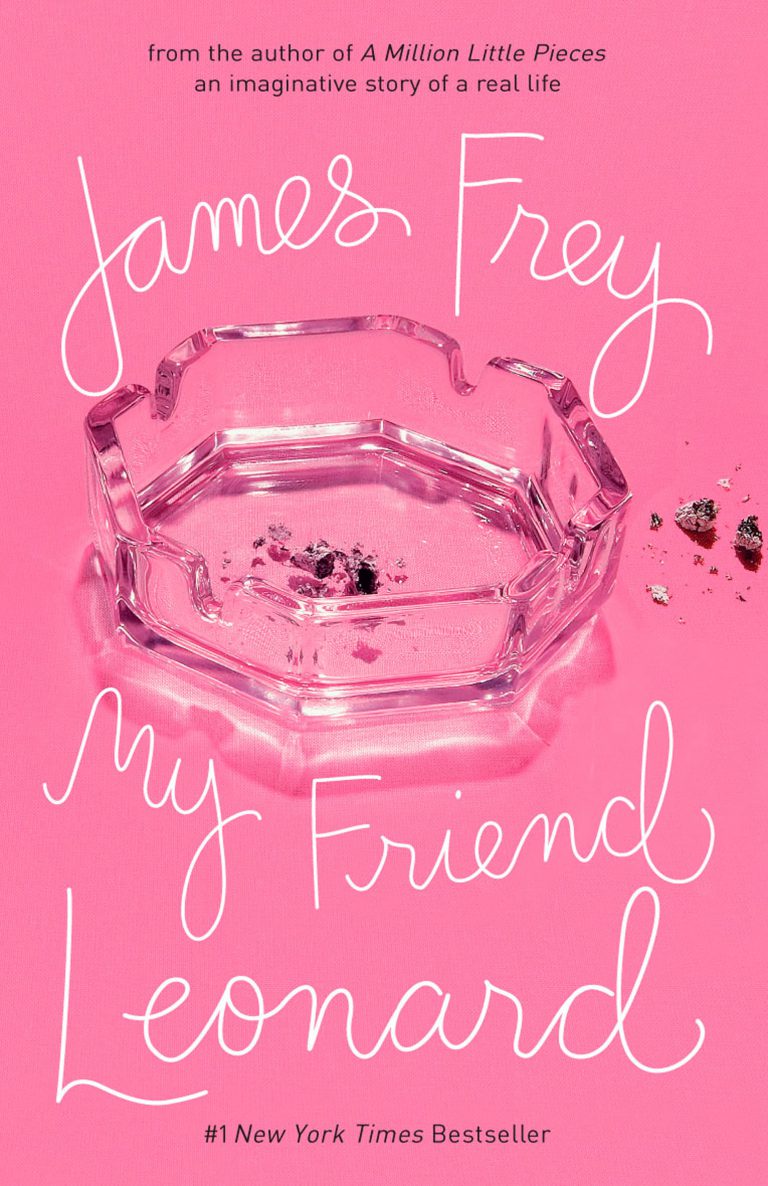

Two decades later, it’s clear to see that Frey was paces ahead of both the public and the publishing world. A Million Little Pieces, in some sense, forged the genre of autofiction and still shines today as a no-holds-barred showcase of Frey’s unfiltered, unflinching writing style. The book struck a chord with readers who gravitated toward Frey’s sharp, incisive understanding of not only his own heart-wrenching experience with addiction, but with various primordial, deeply human emotions and feelings. Millions of copies and many more books—including My Friend Leonard (2005), Bright Shiny Morning (2008), The Final Testament (2011), and Katerina (2018)—later, Frey is still writing, publishing, and pushing the boundaries of his art.

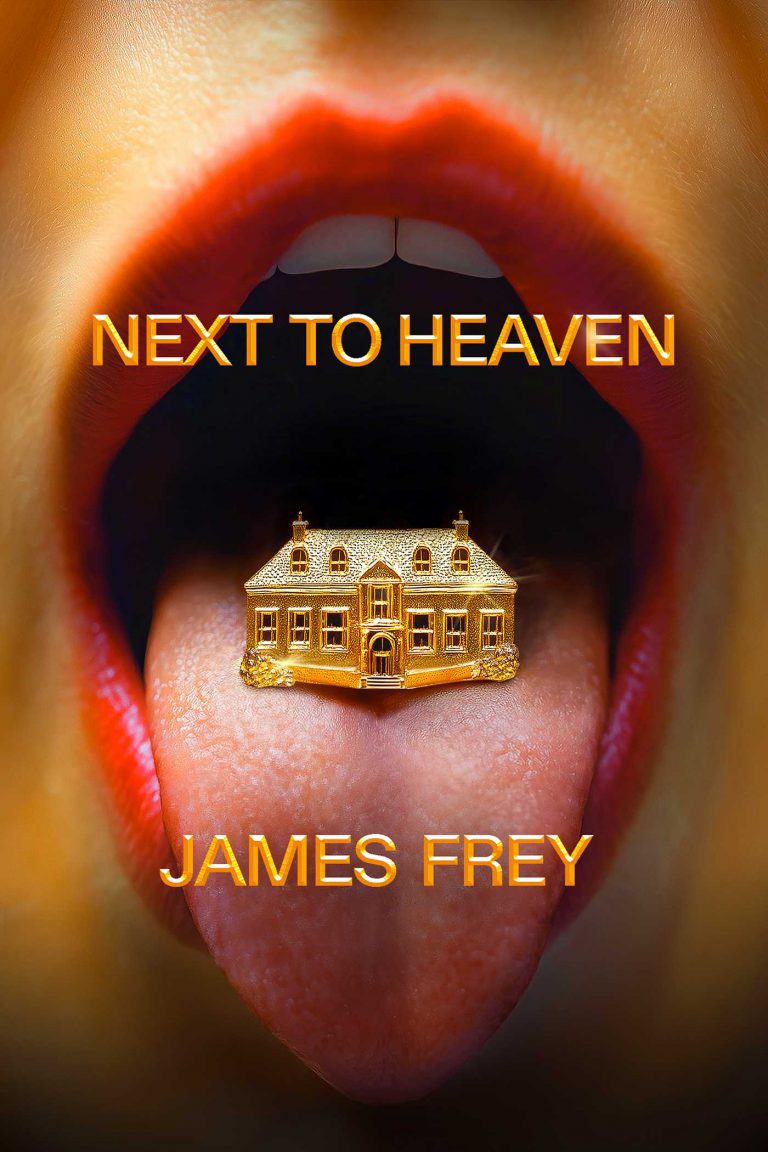

Arriving at an altogether different moment in time—as Frey puts it on this episode of Time Sensitive, “We have witnessed, over the past ten years, the greatest accumulation of wealth by the smallest number of people in the history of civilization”—his latest novel, Next to Heaven (Authors Equity), is a rollicking, raunchy, absurd-yet-not satire that takes place in a fictional moneyed enclave in Connecticut where the one percent of the one percent live out their wildest impulses and darkest secrets. A pulpy page-turner about money and murder, it’s also an exploration of the all-too-human desires for power, pleasure, and greed.

On the episode—our Season 11 finale, in which Frey sat lotus for the entire duration—he reflects on the 20-plus years since the soaring publishing spectacle that was A Million Little Pieces; his long-term study of Taoism and how he tries to live according to the ways of the Tao as much as he can; his writing as a gateway to being as vulnerable, open, and bold as possible; and why love, for him, is the greatest drug there is.

CHAPTERS

Frey talks about how the tenets of Taoism—acceptance, progress, patience, simplicity, and compassion—are threaded into his artistic practice, sobriety, and life philosophy.

Discussing his latest release, Next to Heaven, a murder mystery whodunit set in a fictional town in Connecticut, Frey details his deliberate desire to write a book that, sure, gets a few laughs, but also explores the innate desires that govern peoples’ lives, no matter how wealthy or powerful they are.

Frey considers love and romance as recurrent themes in his books, and explores how writing about emotions for which there are no words for is an essential part of his art.

Looking back on the writers who served as his earliest literary influences, Frey talks about his desire to write books that “cause problems.”

Frey talks about dropping his semi-successful early career as a Hollywood screenwriter to go full-bore into writing his breakout book, 2003’s A Million Little Pieces, and shares a window into his writing process.

Nearly 20 years removed from the Oprah controversy that surrounded A Million Little Piece, Frey says, “My game hasn’t fucking changed. I’m a little mellower. I’m older. I think about heavy shit. I’m a Taoist who watches the river go by. But when I come to do what I do, I still want to fucking bring it.”

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, James. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

JAMES FREY: Hi, Spencer. Thank you for having me. I’m happy to be here.

SB: I wanted to start this interview with Tao Te Ching. The credits page of your first book, which we’ll of course talk about, A Million Little Pieces, notes, “The author is particularly grateful to the Chinese classic Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu, who is believed to have lived in the sixth century B.C. I have read many translations of this ancient text, but Stephen Mitchell’s, published by HarperCollins in 1988, is by far the best. I’ve made a few minor changes in the passages I’ve quoted with Stephen Mitchell’s permission.” Tell me about your “Tao Te Ching time.” How has it shaped your work and your life, your time with this book?

JF: I don’t know if this is being videotaped, but—

SB: It’s not. [Laughs]

JF: … you can see how I immediately sat down when I entered the space, right? I sit lotus, I sit with my hands in a specific position. I sit in a meditative position in a traditional Taoist meditative position. I read the Tao in rehab, thirty-two years ago. I got sent in there. I didn’t believe in god. I didn’t believe in the twelve steps. I had lived a relatively tumultuous and painful life. I was 23. I was a crackhead and an alcoholic. I was facing some real troubles and difficulties, and I had to figure out a way to stay alive. My brother gave me a copy of the Tao. He was like, “Hey, man, maybe you’ll be into this.”

I read it, and it was the first sort of religious or philosophical document that I had ever read in my life that made any sense to me. The translation of Tao Te Ching is “The Art of the Way,” and the book is The Art of the Way of Living. It’s a very simple book that preaches very simple things: patience, simplicity, and compassion. Patience with yourself and others; simplicity in thought, in action, in life; and compassion for yourself and others.

Even since rehab, I’ve had a tumultuous life. I’ve had all kinds of ridiculous things happen, most of which happened because, in some reason, I made them happen [laughter], but they were still difficulties. I’ve been meditating for decades. It keeps me sane. I meditate every day. Taoism has profoundly affected how I write. Taoism preaches a lot of things—it actually doesn’t. But one of the things it preaches is acceptance and progress.

When I write books, I don’t use outlines. I only write one draft. I believe in precision the first time. I have contractual clauses in all of my publishing contracts that publishers are not allowed to touch what I do. They are only allowed to put it through copyediting. I have to use specific copy editors who I’ve worked with for a long time because they—

SB: They know that you don’t like to use commas. [Laughs]

JF: They know that I write with a specific sort of system and rhythm where I don’t follow traditional grammar, punctuation, page layout…

SB: Yeah, it is very much yours. From book number one to present, it’s there.

JF: When I started out as a writer—we’re sort of digressing from Taoism, but—

SB: We’ll go back. [Laughs]

JF: …my education and my interest is in both art and literature, but I approach what I do much more from a position of an artist than I do as a writer or a person who exists in any sort of literary community. That being said, when I was working to become a writer, I looked at a lot of patterns in both art history and in literature. They are similar, although art’s a little bit different. In every case, the people who made the biggest impacts on the world, the cultural world, were the people who entered it with a hyper-specific voice, a hyper-specific position that was unlike anything that had ever been seen before they arrived and altered the landscape of what they do in ways that were irrevocable.

When you think about that, you have to approach that in two ways. One is the formal approach to it, which, in painting, would be Picasso. I’ll use Picasso as an example. When Picasso and Braque formulated Cubism, it was the first sort of true abstraction of visual art or painting. That’s the breakthrough. Suddenly we are working in the abstract instead of in the figurative; we have opened a new world. When you looked at a Picasso or a Braque, you knew exactly what they were and you understood the importance of them. Although Picasso’s career varied wildly for the rest of it, you could always see his hand in anything he did.

In writing, it’s similar, although writing and literature is vastly more conservative than art. People don’t think about literature as conservative, but it’s unbelievably conservative. It is essentially an artistic medium that hasn’t changed in five hundred years. There’s fiction and nonfiction and poetry, like there’s always been, and there’s words on a page, and there’s a set of rules you’re supposed to follow if you want to publish a book within one of these pre-approved segments of literature.

Literature’s scared of change; literature’s scared of controversy, whereas again, fine art does the opposite. Often the more controversial the work in fine art, the more important it is and the more impact it has, and the more sort of historical relevance it has.

SB: [Maurizio] Cattelan’s banana. [Laughs]

JF: A great example. [Laughs] There’s a million examples, but yes, that’s an example. Radicality is embraced. Radicality in literature is very much not embraced. There’s a whole system of schooling for both art and literature. In literature, they teach you to be very conservative: “Follow this set of rules. Write within these parameters. Write things that fit squarely within our three pre-approved genres of fiction, nonfiction, or poetry.”

SB: You experienced this all too well.

JF: The point is, as I started writing, the point was to write in a way that was absolutely singular, unlike anything that had ever come before it, absolutely identifiable if you read a quarter of a page of anything I’ve ever written. It blew apart all of the things I’m talking about. It blew apart the idea of being able to put it in any specific genre. It blew apart systems of grammar and punctuation that have existed for hundreds of years. It gave the finger to everything. I’m still doing it.

SB: I want to bring this back to Tao Te Ching. As you mentioned, you’re not religious, you don’t believe in god. But if you had to pick a faith, would it be that book? Would that book be—

JF: The Tao? Yeah. The difference between Taoism and other types of things, and Taoists themselves debate whether it’s a religion or not, is that we engage in a solitary practice. Taoism is something you do alone, as opposed to a religion, which is very much communal and community-based. But yeah, I’m a Taoist. I try to live according to the ways of the Tao as much as I can.

SB: There were a couple of references from A Million Little Pieces that I wanted to quote here that I loved. One is, “Be content with what you have and take joy in the way things are. When you realize you have all you need, the World belongs to you.”

JF: Yeah.

SB: This one’s obvious to me, but, “The slow will beat the fast.” [Laughs]

JF: Yeah. The turtle and the hare was not an original idea. [Laughter] It’s like I was saying before, slow, gradual, measurable progress. Another famous quote from the Tao that people don’t know is from the Tao is, “A journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step.” If you just keep taking steps forward every day, you’ll get to wherever you want to go. I’ve approached things my whole life like that, as well. Or at least as an artist, a relentless pursuit at a pace that is whatever it is, but pace isn’t important.

SB: All right. Let’s go to your new book.

JF: All right.

SB: Next to Heaven. This is a book about a wealthy small town in Connecticut, one of the wealthiest towns in the country, a town that was founded, and this is the fictionalized part, by a man who, “Wanted the town to be, next to Heaven, the most beautiful place in existence.”

JF: That’s not fictional. That’s actually real.

SB: Oh, really?

JF: Yeah.

SB: Mudge is real? [Laughs]

JF: You can Google Amos Mudge and you will discover that he founded the town of—

SB: New Bethlehem, which is fictional.

JF: New Canaan, Connecticut, [laughter] in real life and New Bethlehem, Connecticut, in the world that I have created.

SB: Yes. This is a town where “You moved if you were rich, but never wanted to discuss money.” A town with, “Movie stars, rock stars, athletes, the hosts of all three major network news shows, famous comedians, and famous artists, a notorious writer…”

JF: Yeah. [Laughter] There’s a notorious writer who lives in New Canaan.

SB: “… a beloved writer, too many CEOs to count.” The notorious writer obviously sounds familiar. I would say, also, it’s a book about the one percent of the one percent.

JF: It’s a book about the wealthiest people in the world and how they live. There are these bubbles of insane wealth that exist around the country in various places, certainly in Connecticut, Silicon Valley and San Francisco, the west side of L.A., Palm Beach, Florida, certain parts of Dallas, Houston, Texas. There are these bubbles of extreme wealth, and they are different than the rest of the world. Living with people who have extreme wealth is a different experience.

It wasn’t anything I had ever seen accurately portrayed in literature, or at least in contemporary literature. There’s certainly been things about it. White Lotus is an easy example, about very, very wealthy people, but it’s also very wealthy people on vacation. [Laughter] Where do those wealthy people live? What is their day-to-day life like? How is it different? I’ve always said that whenever I write a book, all I’m doing is holding a mirror up to the world, and I show you. This is very much that.

SB: And this world, I would say, that you’ve gained access to. You’re writing about the art world, which you’ve learned a lot about. There’s this Gagosian-like gallery [laughs] in the book. The book starts with an art opening where there are “bankers, hedge fund managers, private equity partners, their wives and girlfriends, the art advisors who help build them their collections and make them feel important [laughs], other artists, friends and family of the artists,” all mingling. It’s a whodunit. This is a murder mystery book.

JF: Yeah, it’s a murder mystery set in the richest town in America. [Laughter] I live in New Canaan, Connecticut, which is, no shock to say, is the basis for the town I write about in my book, New Bethlehem, Connecticut.

SB: There is a Glass House.

JF: There is a Glass House. The greatest collection of Midcentury Modern architecture in the world is in a small town in Connecticut. It’s a cool place to live. I wanted to hold up a mirror and have a few laughs. The best way to do it was sort of a murder mystery. It’s not, like, a dreadfully serious book. When I write, I want people to have a good time. I came about this book because, during the pandemic, somebody asked me to read Jackie Collins’s Hollywood Wives and think about adapting it into a television show. I read it, and we didn’t agree on how to adapt it, but I loved it. I thought it was great. I read a couple of other Jackie Collins books. I read a couple of Danielle Steel books. People don’t give those books the credit they deserve. They’re great, they’re fun, they’re dirty, they’re easy and entertaining as hell. So I was like, “You know what? I live in this world I’m reading about, why not write about it?”

I’ve had entrée into this world in a few different ways. One is, I lived in SoHo and then New Canaan, Connecticut, for the last twenty-five years. Both are filled with rich people. When I moved to New York, I did become very involved in the art world. All of my closest friends in my life are somehow involved in art, whether they’re art dealers or artists or art collectors.

When you entered that world when I did, which was around 2000, around the turn of the century, I met a lot of cool young people, artists and collectors. Over the years, those artists have gone on to become the most famous artists in the world. Those collectors have gone on to become many of the wealthiest people in the world and the biggest art collectors in the world. So I’ve always been sort of part of that as this observer—not an artist, not an art dealer, not a billionaire [laughter], but somebody who moves very fluidly and fluently among all of them. The entrée to the book was that: art.

SB: It really sets a stage that’s also really believable. I do feel like this book is tailor-made for an HBO show, a Netflix show. I mean, it reads like that, and not in a pander-y way, like, “Oh, James is trying to make a TV show.” It’s an entertaining book, like in the Danielle Steel vein that you were talking about.

But also, it’s interesting. You mentioned White Lotus. I feel like there’s a bit of Billions in there, too. Obviously, that’s the Fairfield County, Connecticut, connection, [laughs] and even there’s this new show on Apple TV+, Your Friends and Neighbors.

JF: My buddy Jonathan Tropper makes that show.

SB: With Jon Hamm and Amanda Peet. I won’t spoil anything in the book, but there is, not a character overlap, but character-behavior overlap that happens on that show and in your book. [Laughs] I was like, “Man, there’s something happening in the zeitgeist here. This is just—”

JF: There is something happening in the zeitgeist, which is we have witnessed, over the past ten years, the greatest accumulation of wealth by the smallest number of people in the history of civilization. It has fucking changed the world. While that has been happening, we have seen the rise of social media, which contributed to that massive accumulation of wealth in huge ways, but also spreads information in ways that has never happened before. It has created this tsunami of greed, of addiction, of no morality.

SB: When you say tsunami, I can’t help but think of White Lotus. Sorry. [Laughs] “Tsunami.” [Laughs]

JF: There was a tsunami in Thailand. There’s a tsunami of wealth overcoming the Western world right now. I think people are thinking about it because it’s in our fucking faces all the time.

SB: Your epigraph for this book is Balzac, which I really appreciated that you kind of found this historical moment to couch it. The epigraph is, “Behind every great fortune lies a great crime.”

JF: There are truisms in that statement. A lot of the wealthy people I know live in the gray areas. I was setting the book up with a classical French literary reference, a reference to wealth, a reference to the past ten years and this accumulation of wealth, and it sets the book up to go where it goes.

While I wrote a book that I hope is entertaining—I hope once people start reading it, they can’t stop. I hope you laugh. I hope you get turned on. I hope you’re disgusted. I hope you’re thrilled and scared.

SB: Your other books aren’t murder mysteries, obviously, but it does achieve what those books achieve, too, in the sense that you feel all the feels. This is a book that’s exploring themes of desire, sex, hunger, pleasure, guilt, shame, fear, love…

JF: Hate.

SB: Power.

JF: Power, murder, greed.

SB: Themes, I would say, that exist as a constant thread in your work, but are also just really primordial, deeply human themes. I love how the narrator in, just to go to your 2018 book, Katerina, lays it out: “We are living in what is supposed to be an advanced society. Our desires, though, our desires are the same. The same as they have been since the first day one of us stepped out of a fucking cave. Love fuck eat drink sleep.” [Laughs]

JF: Yeah.

SB: I would love to hear your—

JF: Those are still our desires, and all money does is make them more accessible and let you buy more expensive versions of them. That’s it. Our desires are the same. We don’t like to think about it, but we’re fucking animals. There’s this whole trend on social media right now about could a hundred guys kill a silverback gorilla? [Laughter] It’s astonishing the amount of time people are devoting to debating this, but we’re just kind of very smart gorillas.

SB: It’s the stuff Werner Herzog movies are made of.

JF: We’re smart gorillas and our desires are the same. What wealth gives you is the ability to make any desire you have, any desire that fucking exists—even to go into space—possible. That’s what money gives you. Those are the types of people that I live with. I’m not judging them. Rich people have really nice fucking lives. I will say, I don’t think they have better lives than anybody else: Your problems are just different and you suffer in more comfort.

SB: Velvet coffin vibes.

JF: Yeah, I always say “the golden prison.” There’s a reason there’s a golden house on the front cover [of Next to Heaven] [laughter]—it’s a golden fucking prison.

I wanted to write about money in a way that connected with people and reflects what I’ve seen and experienced over the past few years. The rich live in a different fucking world, and it’s a fun world.

When I think about it, I referenced Jackie Collins and Danielle Steel. They were in some way very involved in the creation of it. I also think a lot about Gatsby. We don’t think about Gatsby as an entertaining book or a fun book, but that really is the reason why so many people have read it. It hits on classic American themes and universal literary themes, but it’s also entertaining and fun to read.

SB: Like Gatsby, your book’s got a rollicking party. [Laughs]

JF: Yeah, mine’s a little different. [Laughter]

SB: I’ll just say it’s orgy-ish. Well, it is an orgy.

JF: We can say it. The plot of the book revolves around a murder that comes out of a swinger’s party at a billionaire’s house. [Laughter]

SB: That doesn’t actually give anything away. That’s not a spoiler.

JF: That actually also happens in all of these über-wealthy conclaves. The über-wealthy are bored. They look at their wife and think, “Well, my buddy’s wife’s hot,” and his buddy thinks, “Well, my buddy’s wife’s hot,” and they all hang out and fuck and that happens.

SB: [Laughs] This is taking it in another direction, but love is a theme that resonates in the book, but also across your work, like James and Lily in A Million Little Pieces, and Jay and Katerina in Katerina, the various love triangles in Next to Heaven. [Laughs]

JF: I write about love. When you’re a writer, people will always be like, “What do you write about?” They ask, and they also say, “Fiction or nonfiction?” I sort of chuckle when they ask that. But when they ask what I write about, I say, “I write about love and art and sex and human pain.”

SB: The thing about love, and I wanted to stick on this because you’ve written so beautifully about this in your books. Yet, I think, because you’ve been known as this “bad boy of American letters,” you haven’t been recognized—

JF: Thank you.

SB: … for this. And your books really do capture love in all of its nuances, from “new, fresh, thrilling, overwhelming, all-consuming love” to total, utter heartbreak.

JF: I’ve experienced those things in my life. I’m a romantic in my soul. I love love, I love being in love. I love the process of falling in love. I was married for twenty years. I loved being married most of the time. We all do, right? One of the things I try to do in my books is say the things we all think, but nobody else will ever say. In my books, I’m far more vulnerable than I am as a human being walking around in the world. I always say to myself, “Say everything. No filters. Be bold as fuck.” In our hearts, I think all of us, certainly, we all feel love. I always say love is truth in God. We all have our own experience of it. We all have our own view of it. We all have our own deeply subjective view of all of those things.

Love, to me, is the thing that counterbalances all the rest of the bullshit in life. You can be broke, you can be addicted, your body can be fucked, and you can be facing huge—insurmountable potentially—challenges. But if somebody loves you, none of it matters. So I write about it because it’s a big part of human existence and my human existence. I’ve been in love a lot: long loves, short loves, passionate loves, self-destructive loves. I write about emotions, really, like I said, human pain.

SB: There’s a bit from Katerina I wanted to quote here, which you write about “love that overwhelms. That justifies our existence. That provides proof we are here for a reason. That either confirms the existence of God and divinity, or renders it utterly meaningless. Love that makes life more than just whatever we know and see and feel. That elevates it. Love for which so many words have been spoken and written and read and cried and screamed and sung and sobbed, but is beyond any real description of it.”

JF: Yeah, that’s love, man.

SB: That love. [Laughs]

JF: I talk about a lot of stuff, and that’s an example of it. I love Jackson Pollock. I remember the first time I ever saw Jackson Pollock. I was about 8 years old. I was living in Cleveland, Ohio. I had A.D.D. I was a fucking rowdy, exceedingly difficult kid. My mom signed me up for art lessons at the Cleveland Museum of Art, thinking, “Maybe that’ll help him out.” I remember we were walking through the museum on a Saturday morning to get to where the class was, and I saw a Pollock. I just stopped, and I just looked at it.

I didn’t really understand it at the time, but I always was fascinated by Pollocks. Maybe when I was probably 18, I saw “Full Fathom Five” at MoMA. I understood that the reason I liked the painting on some basic fundamental level is that it expressed emotions for which there are no words. So I could look at a Pollock painting and understand the feeling he felt, or I believed I could, or interpreted it however. It made me feel in ways that there are no words for.

So when I talk about love, you can’t really write about it truthfully—or share the true experience of it—because there are no words for it. Maybe music gets the closest… Painting? They’re all limited in certain ways, but that’s part of the beauty of love is we don’t even know how to explain it. We don’t even know how to verbalize it. It’s the greatest drug that’s ever existed. I love writing about it. I love being in love. I love love. And thank you.

SB: [Laughs] Time and aging I also wanted to bring up because they’re under-layers to this new book. I would say time is just a central component of your work. In Katerina, which sort of goes back and forth between this twenty-five-year increment, but even in the new book, there’s this moment where one of the narrators says of one of the characters, Grace Hunter, “Days moved slowly and years moved quickly. And she woke up one day and she was in her forties. Time doesn’t fly, it vanishes, like mist in the morning, summer flowers, dreams.” I loved that moment. I really felt like you were capturing something very true about time, which is that we all get caught up in our lives, and then, one day, something occurs or we just feel something and all of a sudden there’s this time shift.

JF: I thought about that because I’m getting older, man, right? I’m 55 years old. I’ve been a writer now, a professional writer, for thirty years. I have children in college. I woke up and I was old, and it went by real fast. You always hear people talk about, they say these things, “Oh, you will love your children. Oh, they will grow up so fast. Oh, you’ll blink and you’ll be 60.” You’re always like, “Ah, yeah, yeah, yeah.” But I fucking blinked, man, and I’m 50-fucking-5.

You start having to stare down and think about and contemplate real things as you get older, like, what do I want to do with my remaining time? I’ve thought a lot about how old have the other males in my family lived, to try to guess how long I’m going to live. We were talking before this started about how I’m friends, actually independent of our friendship, with your wife. You guys are entering an incredibly exciting stage of your lives where you’re talking about [how it] might be time to have a baby.

SB: Yup. [Laughs]

JF: It’s going to be extraordinary for you, but you’re going to be 60 and you’re not going to know what the fuck happened.

SB: I’ll come back to this episode at 60.

JF: You can.

SB: “James was right!” [Laughs]

JF: I don’t think so much about my life, but I think a lot about: What do I want to do with it now? A lot of the things you’ve brought up today—Taoism, being accepting and joyful about whatever you have—are a lot of things I think about as I get older, especially when I think about rich people, like the book. I know so many rich people who have more than fifteen generations of their family could ever spend, and they still work fourteen, sixteen hours a day—they’re still fucking stressed out. I always say to all of them, “What are you doing, man? Don’t you have enough? Even if you just count your interest, it’s impossible for you to spend what you’ve got.”

One of the themes of the book is that money is a drug. That money is this addiction, that money—

SB: And work, power.

JF: Work and power, it’s all tied up. With money comes power, as we have a president who’s a simple example of that. Taoism, again, has had a huge part in how I think. I contemplate, what do I want to do for the rest of my life? Honestly, what I want to do is sit in the woods and meditate and read books and look at art and listen to tunes, and be the best dad and the best friend, and the best boyfriend, companion, lover, whatever word you want to be, I can be. I don’t give a fuck about any of the rest of it. Do things that bring me joy. That’s the only lesson I think that has any value in aging is: Design your life to bring you the most peace and joy that you can possibly do.

SB: Marie Kondo your life. [Laughter]

JF: Kind of. [Laughs] I’ve never watched Marie Kondo [laughter], but I live like— Marie Kondo would walk into my house and look around and be like, “You’re good, bro.” [Laughter] It’s incredibly simple. It’s mostly empty. There’s books, there’s stereo, there’s art. Beyond books, art, and musical devices, everything else that exists in my house has to have a function. It has to be there for a reason. So it’s very spare, very simple. It’s all white.

SB: Spartan.

JF: Yeah.

SB: Minimalist.

JF: It is very minimalist. It is very simple. It’s hard to say it’s spartan when there are Warhols and Picassos on the wall [laughter], but it is simple.

SB: Let’s go back to your youth here. I want to start by asking you about your reading. You’ve said and spoken quite a bit about the influence of authors like Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac and Bukowski, Hunter S. Thompson, Ken Kesey…

JF: Baudelaire, Rimbaud.

SB: In preparation for this, I watched the Larry King interview you did. In it, you talk really eloquently about that your aim was really ultimately, in writing A Million Little Pieces, you wanted to belong to or be a part of this tradition, a “long tradition of what American writers have done in the past, people like Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Kerouac”—so back to Fitzgerald. Was that sort of your bad-boy dream? Growing up, I know that the thing you did consistently was read and then eventually start getting messed up on drugs and alcohol. Those were the two things that were your consistent companions, I’d say.

JF: I always read a ton and I got in trouble. That was my childhood. My parents were always told, “Oh, he’s a gifted boy if you can just figure out how to control him. He’s a very smart boy.” I didn’t want to be controlled, and I didn’t let anybody control me. And I read a huge amount. I have no memory of life without reading being a part of it.

As I read—I was talking about this with somebody recently—as our culture has changed, phones and social media have very much sort of pacified the youth of the world, and it has also sort of broken down subcultures that used to exist. There used to be punks and metalheads and hip-hop crews and skaters and whatever, but they were sort of set subcultures. The one I was a part of was the fuck-ups, the people who were self-destructive and blew every opportunity they ever had and loved drugs and alcohol. That was me, and that was my friends.

SB: Those people didn’t always love reading. And you loved reading, too.

JF: They didn’t always love reading. So I was this kid who loved reading and was a fuck-up. [Laughter] I vividly remember this. When I was 21, a friend of mine gave me a beaten-up copy of Tropic of Cancer and was like, “You should give this a read, man.” I read it, and I just couldn’t believe it existed. For all of my life, I had always read books, and I was a heavy reader. I was reading Tolstoy at 16, which wasn’t that uncommon back then. It’s exceedingly uncommon now. But I came across Henry Miller, and I’d always thought of writers as these magical people who went to Harvard—which wasn’t going to be an option for me—or who had special gifts. I was never one of them.

Then I read Henry Miller, and I was like, “That motherfucker’s just a shit-talker. That motherfucker is just letting it fucking rip. He’s letting it rip. I could do that. I could do my own version of that.” Henry Miller led me to Baudelaire and Rimbaud and Céline. I had already read Jack Kerouac and Charles Bukowski, and certainly Hemingway and Fitzgerald and all of them. When I started out, the goal was to be the most notorious writer in the world. [Laughter]

SB: Mission accomplished. [Laughter]

JF: The goal is to be—not just the most notorious. When I was coming up, being a famous writer was a whole thing. Tons of people wanted to be famous writers. I wanted to be the most notorious in the world. I wanted to write books that—when we talk about art—that shattered this safe, horseshit, conservative culture of literature where you are told, “Follow all of these rules. Your book is this, this, or this. You have to follow all these rules that have existed for hundreds of years.” Well, fuck that.

SB: Yeah, which the M.F.A. culture has only exacerbated.

JF: Oh, yeah. You go to get an M.F.A. to be taught to write like somebody else. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to blow the fucking world apart. When I talk about it in Katerina, I wanna burn the motherfucking world down.

SB: [Katerina is] a book that literally starts with Tropic of Cancer. Tropic of Cancer is the impetus for this character, Jay, going to Paris.

JF: If you read the first page and a half of Katerina, they very much are a heavily referential homage to the first two pages of Tropic of Cancer, which to me are the most powerful thing I have ever read for myself.

All my heroes were fuck-ups. Would I rather be Sonny Barger, the leader in the Hell’s Angels, or a politician? I’ve always admired the rebels. I’ve always admired the people who are willing to lift their middle fingers and be like, “Come at me. This is what I got. This is what I’m doing. Come at me.” I approached—from very early—becoming a writer from that perspective: Write books that cause problems. I remember I was like, “Henry Miller had a book banned in every English-speaking country in the world for thirty-five years? Fuck yeah. [Laughter] I want to pull that off.”

SB: But also, I read somewhere where you said, as soon as you read the final word of Tropic of Cancer, you knew—you were like, “Yes, this is my journey.” That final word is heart. I looked it up. [Laughs]

JF: I didn’t know that. I finished Tropic of Cancer, and in some way, I don’t know how to describe it or understand it, but I was like, “I’m going to do that. I’m going to do this. I’m going to do this. I’m going to be my generation’s Henry Miller or Baudelaire or Kerouac or Bukowski.” I remember when I was thinking a lot about it… There’s a couple of lines from a Bob Dylan song called “Up to Me” that was originally supposed to be on Blood on the Tracks, but got taken off at the last minute. You can hear the tune, but there’s a line from “Up to Me” and Bob Dylan says, “If I had thought about it, I never would have done it. I guess I would have let it slide. If I had paid attention to what others were thinking, the heart inside me would have died. I was just too stubborn to ever be governed by enforced insanity. Somebody had to reach for the rising star, I guess it was up to me.”

I remember hearing those lyrics and I was thinking all about this: “Could I fucking do this?” I was like, “You know what? Somebody’s gonna do it. Somebody’s gonna be my generation’s fucking Henry Miller or Kerouac or Bukowski.” I was like, “I guess it’s up to me. Go fucking do it. You can.” I knew, I was like, “I’m going to pull this off. It might take five years, it might take twenty-five, but I’m going to fucking do it.” I set about going to do it, immediately. I was a C-minus student and a fucking crackhead and a drug dealer. So it wasn’t like I had any sort of—

SB: Exactly. You graduate Denison College, you go off to Paris, you find yourself in London, Chicago, eventually make your way to L.A…

JF: Yup.

SB: In L.A. you’re hustling screenplays. [Laughter]

JF: Yeah, I had this whole plan.

SB: Which is sort of wild because I was thinking about your “L.A. time” and then thinking about Fitzgerald, not knowing that he’d come up earlier in this conversation. Fitzgerald had a hell of a time in L.A., famously.

JF: He died penniless in a puddle of his own piss writing movies for assholes. I’m not going out that way. [Laughter]

I sort of took things I knew from the art world when I was approaching being a writer. Artists will do a lot of things to make a living before they can make a living as an artist. But they all generally have to do something with art. They’re art handlers, or they work at a gallery, or they work for another artist. But they are in some way engaged with what they do.

I moved to Los Angeles in 1994. The movie business was booming, the screenplay business was booming. I had been working for the mob, and I had been working in bars, and I was like, “You know what? I’ve had enough of this.” I was penniless. I wasn’t penniless working for the mob, but then I quit. And so then I worked in bars and then I was penniless. But I was like, “Fuck it. Figure out some way to make money writing and you can keep trying to learn how to write books. Teach yourself how to write books.” So I wrote a dumb movie. I wrote a romantic comedy.

SB: David Schwimmer. [Laughs]

JF: It got made. It was ridiculous and commercial enough that I moved to L.A. I hustled it; I sold it. It got made with David Schwimmer. Doug Ellin, who went on to create Entourage, directed it. His first—

SB: It’s called Kissing a Fool, if you all want to watch it.

JF: Kissing a Fool. It’s about a novelist. I was even writing about what I wanted to be then, but… Then I suddenly had a career as a screenwriter at a pretty young age. So I just wrote movies and made money and supported myself while I kept teaching myself how to write books. I kept reading and I kept looking at art. I have a lot of fond memories of that time in my life, when I was teaching myself how to write.

SB: So from there, you go on to write A Million Little Pieces, in the spring of ’97, or I guess—

JF: I wrote it in—

SB: … that’s when it starts. But then you take this big pause, there’s this pregnant pause in the middle, and—

JF: You do a lot of good research.

SB: Yeah, thanks, I try. [Laughs]

JF: I’m impressed.

SB: I try. But you ditch screenwriting and you start up the book again in the fall of 2000. Your friends and family, and everyone’s like, “This is insane. What are you doing? But okay, fine.” [Laughs] You write this book.

Tell me about the time of writing that, like that in-between moment of, like, okay, you’ve basically become a reasonably successful screenwriter and you could definitely go down that path. Instead, you’re like, “Nah, I’m going to go have my Bukowski moment. I’m going to go write my book.”

JF: So I was 29. I’d had a couple movies made, I had written a couple, I had produced a couple, I had directed a movie. I had a really nice career. I was like, “Yeah, this is cool and you have done what you achieved,” which was: I had bought a house, I had a career, I had a little bit of dough in the bank. But I was like, “This isn’t what you came to do. You came to write the fucking book.”

The first stage of that was, in 1997, I wrote the first fifty-five pages of A Million Little Pieces in basically one long sitting. I don’t remember how long it was. It was probably twelve or fourteen hours long. I remember when I wrote it, it just came. It just showed up. I didn’t question it—Taoism—I didn’t question it. I was just sitting by a river watching it go by.

I read those fifty-five pages and I was like, “Fuck, this is it. You got it. This is fucking it.” So I started again thinking about, Okay, how can you do this from here? I needed a little more money to be able to take about two years off. So I wrote a couple other movies, made some money, and then took a second mortgage out on my house. I had enough money for about eighteen months. I sat down and I was like, “Fucking go.”

I remember saying to myself— When I write a book, I always have a wall where I put things and I confront myself, and I’m like, “Put up or shut up you motherfucking chump. If you got it, now is the time to do it.” I knew I had this fifty-five-page chunk of what I had been trying to do. So I started on page fifty-six and I just roared. It was great. I was living in Venice, California—as we talk about architecture—in a Morphosis house. I listened to music and I smoked cigarettes, and I just let it fucking rip.

I remember as I was writing that book, I was like, “Be as bold as you can. If you don’t think you should say something, say it more forcefully than you had imagined.” No rules, no boundaries, nothing, just fucking go. It was a joy. It was hard. It was grueling. It was all-consuming. It was some kind of fever dream. When I think about my books… The only book of mine that I have ever read cover to cover is A Million Little Pieces.

When I think about the books now, people ask me questions about them, as you read quotes from them, sometimes I remember writing that; oftentimes, I don’t. I don’t remember most of what’s in the books I have written because I have never read them. When I think about them, people are always like, “What’s your favorite book?” I don’t think about what I’ve written. I think always about the process of writing them. Where was I? What was happening in my life? Why did I write it? Most importantly, what did it feel like? What kind of music was I listening to? Music’s a big part of my writing process. I listen to music always. I listen to music basically twenty-four hours a day, but especially when I’m writing.

SB: What was the A Million Little Pieces soundtrack? Do you remember?

JF: I do. I use music very specifically when I write. You were talking earlier about how I try to get at a feeling.

SB: Mm-hmm.

JF: I try to make myself feel whatever that feeling is while I’m writing, which can be a manipulative process. The way I do it most often is music. So most of A Million Little Pieces, I was listening to seventies and eighties hard rock and punk. I was listening to early Black Sabbath. I was listening to non-acoustic Led Zeppelin. I was listening to the Sex Pistols and Black Flag and Minor Threat, The Vandals, and then occasionally punctuated with super corny eighties love tunes [laughter], fucking Jeffrey Osborne, James Ingram, Quincy Jones, literally “On the Wings of Love”-type shit. When I was writing about me and Lily, I remember when I was in the joint, all you had was radio. I remember, when I first met her, I sought out the soft-rock station in rural Minnesota. I’d be like, “Oh, fuck yeah, James Ingram, bring it to me, ahh.”

SB: [Laughs]

JF: I listen to music while I write and I manipulate myself into feeling the things that I want to write about.I think about the books much more as sort of the process of them and how it felt when I wrote them. I think about them as words. People will say A Million Little Pieces, and I’ll say, it was one long fucking scream. My Friend Leonard was like a hug. Bright Shiny Morning was a fuck-up walking down a street with his fingers up. The Final Testament’s a book about pain. It’s a long sob. Next to Heaven, the book I just wrote, it’s a giggle.

SB: It is actually. [Laughs] It is.

JF: It’s sort of a knowing giggle.

SB: Yeah, a wink.

JF: The process is the most important part for me, always. I write books in super specific ways, I don’t have outlines. At some point, I really start thinking about a book. At some point the book comes and, I don’t know how to describe it, but it just shows up. Then I think about my job as translating it as precisely as possible.

SB: What was the Next to Heaven music? What was the soundtrack there?

JF: It’s on my phone.

SB: [Laughs]

JF: It was a lot of fun classic rock, like Van Morrison live, a lot of party music, like some early Miley Cyrus, “Party in the U.S.A.,” like 2000s party music. It was a lot of eighties, just sort of pop and rock. I listened a lot to the eighties and nineties channels on SiriusXM while I was writing it. It was fun music, it was laugh music, it was party music. There were a few times where maybe I switched it up a little bit, but mostly it was like, you’re writing a funny, dirty, dark, dark, dark satire of wealth. It should be fun.

Like I said, I don’t use outlines. I write the book once. I’m super precise. My memories of my books are all about the process of them. The one thing I did differently with Next to Heaven than I had ever done is, I’d normally set pretty reasonable page quotas. When I start writing a book from the day I start till the day I finish, I take no breaks unless hospitalization is involved, which has only happened once. I go straight from the day I start to the day I finish. I work from eight-to-sixteen hours a day. I used to just say, if I can get two to three pages of perfect polished writing done, that’s the day. So some days it would take me two hours. Some days it would take me twelve.

With Next to Heaven, I just wanted to see how fast I could write a book from the day I started to the day I finished, going fucking hard every day. I wrote the book in fifty-seven days, and I worked probably fourteen-to-sixteen hours a day. When I write, it’s absolutely a solitary process. I have to be alone. I have to have control of my environment, meaning the music that’s around me, what I’m seeing, and what I’m sitting in. For Next to Heaven, I sat in a custom-made Eames lounge chair, lotus position like you see me sitting here. It’s custom-made because it’s bigger. It’s about fifty percent bigger than a normal Eames chair. So it lets me sit lotus in it, and then it’s covered in a very expensive black mohair. So it’s very comfy.

I started and I just wanted to see how fast I could do it. So it was these real long, long, hyper-intense days. And I sit in the chair, but I also sometimes get up and dance by myself, to the music. Sometimes it’s like headbanging. Sometimes it’s like, weird. Sometimes I pretend I’m slow dancing with a hot girl who I believe has a crush on me.

SB: [Laughs]

JF: It’s a very weird process to describe. It’s a fever dream of some kind where these words are flooding out of me. I don’t even know what the fuck they are. I don’t really remember them. It’s a very pure process of creation for me at least. It’s what I love and it’s what I think about when I think about the books.

I had this weird thing a few years ago. They have this thing in Lyon, France, called the International Symposium of the Novel. It’s every four years. It’s like the fucking World Cup for novelists. [Laughs] Each year they invite four people, and they have to be from different countries each time. So if there had been an American the time before me, I [would] have to wait. So I did it in, I think, 2012. While I was there in Lyon, I met with six or eight students who were writing their theses on my work. I had two sessions where I had one session with all of them, and then I had individual sessions with each of them, and they would ask me questions about my book, and I’d be like, “I don’t have any fucking idea what you’re talking about. I don’t know what you’re saying. I don’t know what you’re asking me. I don’t remember writing that, and I have no idea what it means. It means whatever you want.”

But if they wanted to ask me, like, where was I when I wrote— I wrote half of Bright Shiny Morning in France, immediately after the Oprah controversy. Then I came back and I wrote the second half of it in an apartment above where the nightclub Sway is, where Paul Sevigny currently has a nightclub. That apartment above that nightclub was uninhabitable because it was above a fucking nightclub. So the dude who owned the building rented it to me for two hundred and fifty bucks a month for six years. I wrote the other half of it right there. I remember I was fucking pissed. I was like, “These motherfuckers say my career is over? These motherfuckers say the only reason people read what I do is because of some bullshit? Well, it’s time to fucking show ’em.”

SB: Yeah.

JF: I listened to a bunch of metal and a bunch of punk, a bunch of the Rocky theme song, “Eye of the Tiger,” “Here I Go Again” by Whitesnake [laughter], “Highway to Hell” by AC/DC. I was like, “Motherfuckers.”

SB: We skipped over that part. So I do want to just at least touch on it. We don’t need to belabor the Oprah controversy. It’s been played out enough. I think a writer at The Guardian got it right when they described this moment as “one of those orgies of public uproar in which everyone seemed to lose all sense of perspective and wildly overstate their case.” [Laughter]

JF: I remember Jon Stewart once said something. I love that he said that. Jon Stewart, when it was all happening, was like, “Okay, America, time for a conversation.” [Laughter] He showed a picture of George Bush and he goes, “This guy lied and took us to war and you love him. This guy lied while he was writing a book he calls ‘art’ and made America read and you fucking hate him.” [Laughter] I was like, “Yeah, that about sums it up, man.” People don’t think about A Million Little Pieces—even the Oprah stuff—the way I do. I think about it very differently.

SB: It’s almost twenty years since that whole thing.

JF: I have a therapist who probably knows me better than any person in the world, and I started seeing that therapist about a month after the Oprah Book Club announcement. The book was selling.

SB: Good timing.

JF: Five hundred thousand copies a week. It sold five million copies in three months.

SB: It’s in twenty-eight different languages.

JF: No, it’s in forty-eight different languages.

SB: Wow.

JF: I went from being a well-known and successful, but anonymous writer to being famous overnight. I couldn’t walk down the street in New York. I couldn’t get on a plane, I couldn’t do anything. As a writer, it’s real jarring, because I was used to spending almost all of my time alone and being inside of myself. So I started seeing this therapist. I was like, “I hate being famous, and I hate fucking being on Oprah, man.” I was like, “I got in this to be the world’s most notorious author. Now I’m like Oprah’s little addiction guy, like her little fucking show pony.”

SB: “Self-help bro.”

JF: “Self-help bro.” [Laughter] I was like, “Fuck this. I hate this. This isn’t what I signed up for.” Then when it blew up, I remember I went in to see him, and he was like, “How’ve the last couple of weeks been?” Because there was the Oprah and the Larry King and then the Oprah, all this bullshit. I sort of laughed, and I was like, “Surreal, man.” He was like, “Well, you got what you wanted. How does it feel?” I was like, “I don’t know yet.” But at that moment, it shifted how I thought of it, like, “Oh, this is so terrible,” to him saying, “You got what you wanted.” I was like, “Yeah, I did.”

SB: I love that, at the end of 2006, New York magazine put you on their approval matrix as “highbrow despicable,” which is probably right exactly where James Frey pre the Oprah controversy wanted to be.

JF: Where James Frey to this day wants to be, man. [Laughter] My game hasn’t fucking changed. I’m a little mellower. I’m older. I think about heavy shit, I’m a Taoist who watches the river go by. But when I come to do what I do, I still want to fucking bring it. I save my ferocity for my work. In every other aspect of my life I want to be peaceful and quiet and kind and private. But when I write a book, I come. I’m bringing what I got.

SB: I think also it’s important to state here, as with any controversy or moment like that, there’s a before and there’s an after and there are decisions to make. You plodded on. You were just like, “Screw this. I’m gonna keep doing what I do, which is write books and tell stories.” I just think it’s interesting that—

JF: One thing about it that’s never really been talked about fully, I got hammered in the United States by the media, but if you want to look at the data, I was number one on the Times list for five months before the controversy and for twelve after. So it wasn’t—

SB: No, there was a positive thing. Even for Oprah, I mean, she later apologized to you of course [laughs] and maybe you have things to say about that.

JF: The only thing I have to say about that is, yeah, and I didn’t apologize back, and that’s it.

SB: What to me is so important about how you weathered that, I should say, is you didn’t quit. There was no quitting.

JF: No, there was the opposite. It was interesting, and this has been written about a little bit. I had a bunch of famous writer friends by that time, but they weren’t like the young guys. Bret [Easton] Ellis was a good friend of mine. Jay McInerney was a friend of mine and Norman Mailer and Kurt Vonnegut and, [to a] lesser [extent], Tom Wolfe were friends of mine. So I remember when the stuff first started happening, I would occasionally call Bret or McInerney for advice. I remember I called Bret after the Oprah stuff blew up. I was like, “What do I do here, man?” He was like, “You know what, James? You have so wildly exceeded anything I’ve ever done that I have no advice for you anymore. Good luck.” [Laughter] I sort of laughed and—

SB: Says the guy who wrote American Psycho.

JF: Says the guy who wrote American Psycho. [Laughter]

SB: Right.

JF: So then I was talking to Mailer about it, and Mailer was like, “Listen, man, it was going to happen when somebody wrote a book good enough and important enough and radical enough. It’s up to you what happens from here.” One of the things I appreciated about Norman was his knowledge of history, literary and art history. But he was like, “Listen, everybody hated Hemingway when he was alive. Everybody hated me. We’ll see if you’re good enough to stand up against it, but that’s what you’ve got now. They will hate you for as long as you’re doing it. And if you’re good enough, it won’t matter. And if you’re not, you’re done.” I took that to fucking heart. When Norman Mailer is saying that to you—

SB: Yeah, take it.

JF: … it’s meaningful. With Bright Shiny Morning, which I wrote next, after all of that controversy, the first line of that book is, “Nothing in this book should be considered accurate or reliable.”

SB: [Laughs]

JF: Then the book is filled with all kinds of lists and historical facts and statistics and all of this shit. I knew that, when that book was read, people were going to be like, “Well, is it all real?”

Then I got a fucking call at some point, I think it was from The New York Times, but I don’t remember exactly. They were like, “We’re finding all kinds of factual issues in Bright Shiny Morning. How do you justify manipulating and making up statistics about a city?” I was like, “Did you read the book?” They were like, “Well, of course we read the book.” I was like, “The first fucking line says ‘Nothing in this book should be considered accurate or reliable.’ If you don’t understand that fucking line, I can’t help you.”

I was also setting a trap, and the trap was if I write a book that gets published as nonfiction, they tear it apart to find out what in it is a lie. If I write a book that’s fiction, they tear it apart trying to find out what’s the truth. Ultimately, the point that I have been trying to make for years is that these genres are irrelevant. Fiction, nonfiction, poetry… We live in a world now where we can’t trust truth on the news and we want art to be the standard-bearer of it? I’m like, “Fuck that. The only truth is the truth I know when it comes to art.” I took a beating for it. I still take beatings for it.

SB: Now look at the state of media and our relationship to truth.

JF: Look at it in literature. I know I get shit for saying this stuff, so fucking be it, man. Look at literature, right?

SB: Yeah.

JF: People talk about, “Oh, James, blah, blah.” Literature has not been the same since I arrived. Every memoir after me is published with a disclaimer in front of it.

SB: Hillbilly Elegy. [Laughter]

JF: You know why they publish them? Because all those motherfuckers do the same shit I do, which is they just try to write the best book. Now there’s a whole new genre that’s been invented—even though I think genres are stupid—called “autofiction.”

SB: “Literary nonfiction,” whatever that means.

JF: The point was to destroy the ideas of these categories. When I look at a painting, I don’t have to say to somebody who I’m talking to, “Is this a nonfiction painting or a fiction painting?” [Laughter] “Is this a poetry painting? What is this?” It’s just a fucking painting.

SB: Maybe you should call your books “paintings.”

JF: I just call them books. [Laughter] People say, “What do you write, nonfiction or fiction?” I say, “I write fucking books.”

SB: Love it. Well, in 2009, after Bright Shiny Morning came out, you said, “I find the older I get, the more radical my work becomes.” Do you think that still holds true?

JF: In some ways, the most radical thing I could do is just write a Jackie Collins book.

SB: That skewers the town you live in. [Laughs]

JF: Not just skewers the town I live in, but the people that I live amongst, right?

SB: Yeah, the very wealthy. There are some lines in there that are pretty good. There’s softballs like, “There is nothing rich people love more than cocktail hour.” [Laughter] But then you have some other ones that are like—

JF: It’s true.

SB: “For as with most great and wealthy families, after a few generations, its descendants had grown lazy.”

JF: Yeah, they do.

SB: “Despite their advantages, rich people were rarely ever cool, though they spent huge amounts of money trying to achieve it. And cool people were rarely rich because they were lazy, and part of being cool is not giving a fuck.” [Laughs]

JF: Yeah, I think that’s all true. I talk at another part in the book, I think, about the currency of coolness at art galleries, that half the reason rich people buy art is so they can feel like they’re cool like an artist. The fundamental conflict there is, every artist I know looks at hedge fund billionaires and they’re like, “Wow, why didn’t I do what that dude does? How rich is that guy? The guy’s got it on easy street.” Every hedge fund billionaire I know looks at an artist and is like, “Why the fuck did I devote my whole life to sitting in a bank office staring at a Bloomberg screen?” They’re each trying to get something from—

SB: But I feel like sometimes you find someone who’s in between.

JF: Occasionally.

SB: Not quite hybrid. I would say Rashid Johnson is an artist who has—he lives in the Hamptons a bunch, but he’s—

JF: I’ve known Rashid for—

SB: Has a show at Guggenheim. He’s incredibly successful. He’s not a billionaire, but he’s—

JF: No, there is now a separate class of artists—Rashid is definitely among them—Koons, Richard Prince, Rashid, Amy Sherald, plenty of artists who now not only sell their art to the point-one percent, but live amongst them and have almost the same resources as they do. I think that’s great. I’ve known Rashid for a long, long time.

SB: Yeah, he’s been a guest on the show.

JF: He’s a lovely, kind, good-hearted, sober man who deserves every success he has seen. Rashid sort of straddles those worlds in the same way I do. And good on Rashid. He makes great art. Like I said, he deserves all the success. The show at the Guggenheim is breathtaking.

SB: Made a film, actually, that really—

JF: Made a movie.

SB: … explores this dynamic of the rich and the haves and the have-nots.

JF: He did. I’ve tried to convince him to go make another movie with me.

SB: He should. Rashid, if you’re listening, make another movie. [Laughs]

JF: Rashid, let’s go. We’ve talked about it a bunch, let’s go do it. I’m a big fan.

SB: You dropped an Easter egg earlier, which is that you said you were hospitalized while writing a book. I want to hear that story if you can share it, if you’re open to it.

JF: I used to have this company called Full Fathom Five. Basically what I did was I took the ancient idea of an artist studio or the contemporary one. You could say—

SB: The Damien Hirst model.

JF: The Warhol model, the Hirst model, the Murakami model, the Koons model—everybody uses that model now. I applied it to the creation of storytelling. I would come up with ideas for books, movies, TV shows, video games, and I had a staff of people who would create the material necessary to try to get those things made. That company published two hundred and fifty books over seven years with forty-one New York Times bestsellers.

SB: Made a movie, right?

JF: We made a few movies, we made a few TV shows, we made a bunch of video games. It was fun, but I sold it to a French billionaire who I worked for for five years. It was a fun job, but I used to fly back and forth between New York and L.A. every other week, and one week out of every twelve I was in Paris. I was writing Katerina while I was doing that, and I got food poisoning twice in one week in Paris from the same thing, which was stupid of me. In France—

SB: You don’t have a trip to Paris without some good food poisoning, really. [Laughter]

JF: Well, in France, they—

SB: Café de Flore food-poisoned me, for the record. [Laughter]

JF: Café de Flore, I’ve never had food poisoning there. I’ve had food poisoning in a lot of places. I’ve had it across the street, at Brasserie Lipp. My favorite thing to eat in France are called bulots. Bulots are giant sea snails. They’re delicious. Americans hate them. I love them. They steam ’em. You scoop them out of the shell, you dip ’em in mayonnaise.

SB: I love a good snail.

JF: I got food poisoning twice from bulots in a week. It was the middle of summer and I was flying home and I fell down while I was walking to the bathroom on the plane—I have pictures on my phone—and hit my head just from exhaustion and from food poisoning twice in five days. I woke up on the plane, I was covered in blood and the attendants all thought I was on drugs. I was like, “No, I’ve just been sick.” There was a doctor on the plane, patched up my head. I got off the plane, they put me in an ambulance, took me to the hospital. I was there for three days for clinical exhaustion, which I didn’t know was real. I had always smirked when I read people were in the hospital for that.

My heart rate dropped; my blood pressure dropped. I had to wear—my kids thought it was delightful—a big orange wristband that said “fall risk” for two weeks. [Laughs] But that’s when I got sick in the middle of writing a book, hospitalized in the middle of writing a book.

SB: Wow. It’s kind of eerie because, actually, the opening scene of A Million Little Pieces, you’re on a plane and you’re waking up and you’re super disoriented.

JF: That happened, too. People are like, “How did that happen?” I’m like, in fucking 1992, there was no security at airports, right? You walked through a metal detector, got on the plane. You could buy a ticket two minutes before the thing took off. My buddy carried me through security with a doctor’s letter and put me on that plane.

I don’t like to fly much anymore. I have a girlfriend now who loves to travel and I’m always like, “I traveled too much in my fucking life. I just want to sit in my yard.”

SB: Very Tao of you.

JF: Watch the river go by, literally.

SB: I want to end on a Tao note. This is quoting from your new book. Maybe some of this definitely comes out of this, but when I was reading this paragraph, I was like, “This is channeled from James Frey, but it reads a bit like it could be Tao.” So I wanted to leave this with you and the listeners.

JF: All right.

SB: “No beauty exists without flaws, however hidden. Absolute safety is but an illusion. No matter what we think or see or believe or feel, perfection isn’t real. And beneath the beauty and safety and perfection of New Bethlehem, there are secrets and there are lies, and there is sadness and there is rage, there is failure and there is desperation, betrayal and heartbreak, hate and violence.” This is the beginning of the book. It sort of tees it up.

JF: I remember this.

SB: But I think people will now want to go read your book after hearing that. [Laughs]

JF: I hope so. That’s kind of what the book’s about. The town I live in, I think, from 1880 to 2014, was consistently the wealthiest town in the United States. Now it’s like one of the top five, as certain Silicon Valley towns have overtaken it. But it’s a description of where I live, this beautiful place with the most beautiful homes, the most high-achieving, most successful, wealthiest people, the best school system, the best sports, the most beautiful parks and the most of them, the safest place literally in the country. Beneath it, there is all of those things. There is humanity beneath the veneer of beauty and wealth and perfection. There is what we started with, which is humanity. There is love and hate and secrets and violence and rage and terror and revenge. And that’s what I wrote about.

SB: Let’s end there. Thanks, James. [Laughs]

JF: Thank you, man. This was one of the best conversations I’ve ever had about what I do. I deeply, deeply appreciate all the reading and research. As a guest, it’s very humbling to know you spent so much time—and awesome. So I thank you so much for having me. Anytime you want me to come back, I’d love to come back.

SB: I appreciate it.

JF: Aside from being a host, I love you just as a human.

SB: Oh, thank you.

JF: If I’m allowed to say this, you married a wonderful woman.

SB: [Laughs] Appreciate it, James. Thank you.

JF: Thanks for having me.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on May 1, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Kylie McConville, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Dutch Doscher.