Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Hiroshi Sugimoto

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Hiroshi. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

HIROSHI SUGIMOTO: Thank you for inviting me.

SB: I feel like if we’re going to talk time, we have to start with fossils.

HS: Oh, fossils. [Laughs]

SB: That seems to be the most obvious place to start with you, particularly because you have this incredible collection of fossils, pottery shards, hand axes, and other Stone Age objects. You’ve described fossils as “pre-photography time-recording devices.” A term I love.

HS: Yes.

SB: Could you elaborate on this “fossil time”? How do you think about fossils through time?

HS: It’s definitely, it’s recording the time…. [Pauses] Actually, the history of the time. When you find a stone and break it, and open it, one side is negative, one side is positive. It’s clearly the record of millions of millions of years ago. This is the beginning of our life formation on the planet Earth. I’m very curious about history itself—my personal history, human history, and the history of life—how it started and why only human beings became human beings. We have a consciousness, we have a mind, but no other animals have this kind of consciousness. Probably the gaining of a sense of time is the starting point of human consciousness. So I decided to use a camera to study my curiosity because the camera actually works as a time machine for me, going backwards in time to study what’s happened in the past.

“Petit Théâtre de la Reine, Versailles” (2018) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: You’ve talked about photography as a process of making fossils out of the present.

HS: Yes. Right.

SB: And your photographs are durational in the sense that you follow these series over long periods of time, but you’re also taking pictures across time. Sometimes it’s a twenty-minute exposure, sometimes a forty-minute exposure.

HS: Yeah. Sometimes, two-hour exposure or [in the case of my “Theaters” series] the duration of the film. People watch the movie as a kind of storytelling, but every single [time], the movies [in my “Theaters” series] always end up in white light, to bring it back to the origin of the white light. So it seems like a life for every single person. We came from somewhere and we disappear to somewhere, and life is in between.

SB: Would you say fossils, in that sense, are the world’s slowest photographs?

HS: Slowest photographs! [Laughs] Maybe longest photographs. No, that’s necessary, the long time exposure. I do quite normal short-time photography, like in my “Seascapes,” it’s very standard. The shutter speed is usually one hundred twenty-five or two hundred fifty, but it’s… Sometimes I stop time. Sometimes I just let the time go and see what’s appeared in my film.

SB: Mmm. Before we leave fossils, I just have to ask you about your collection. How did you begin collecting these fossils? What led you down this path of amassing and building this collection?

“I think about my camera as a fossilization of time.”

HS: Yes. I’m thinking about my camera as a fossilization of the time. It came from my concept, or words, and then I intentionally started paying attention to where I can buy it from, and I found a very funny auctioneer in California. They used to do a twice big auction, quite local, and I found it and they kept sending me a catalog. I didn’t have time to fly to California, but just through the catalog. About maybe twenty years ago I started, and at that time I was able to buy quite museum-quality, huge fossils, but it’s gone. I cannot find them anymore. So I was in a good time.

Then, very early stage of trilobite, the beginning of life through a step-by-step approach through our current time. I can visualize my concept, my time, touching the fossils. And then after collecting the fossils, I started collecting Stone Age tools—old Stone Age, new Stone Age. The human became human from an animal state. Then what they started to make were tools that separated the humans from the ape state to animal state. Then, touching those tools through my skin, I just remember, “Wow. Yes, that was it. That happened.” The feeling through my feeling of skin.

Part of Sugimoto’s collection of neolithic celts and axes. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Part of Sugimoto’s collection of stone implements from the Paleolithic era. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: It’s like time travel.

HS: Yes. I just feel clearly what [it felt like to be] a human being [back then]. You were making tools, and then it’s so easy; it fits your palm and then you can cut the nut, break the nuts, cut the tree. Just trace back my memory, not as a personal memory, but the human as form.

SB: In some sense, that spirit, that feeling of what it’s like when you hold a hand ax, for example. Do you seek to try to achieve some of that through photography? That feeling?

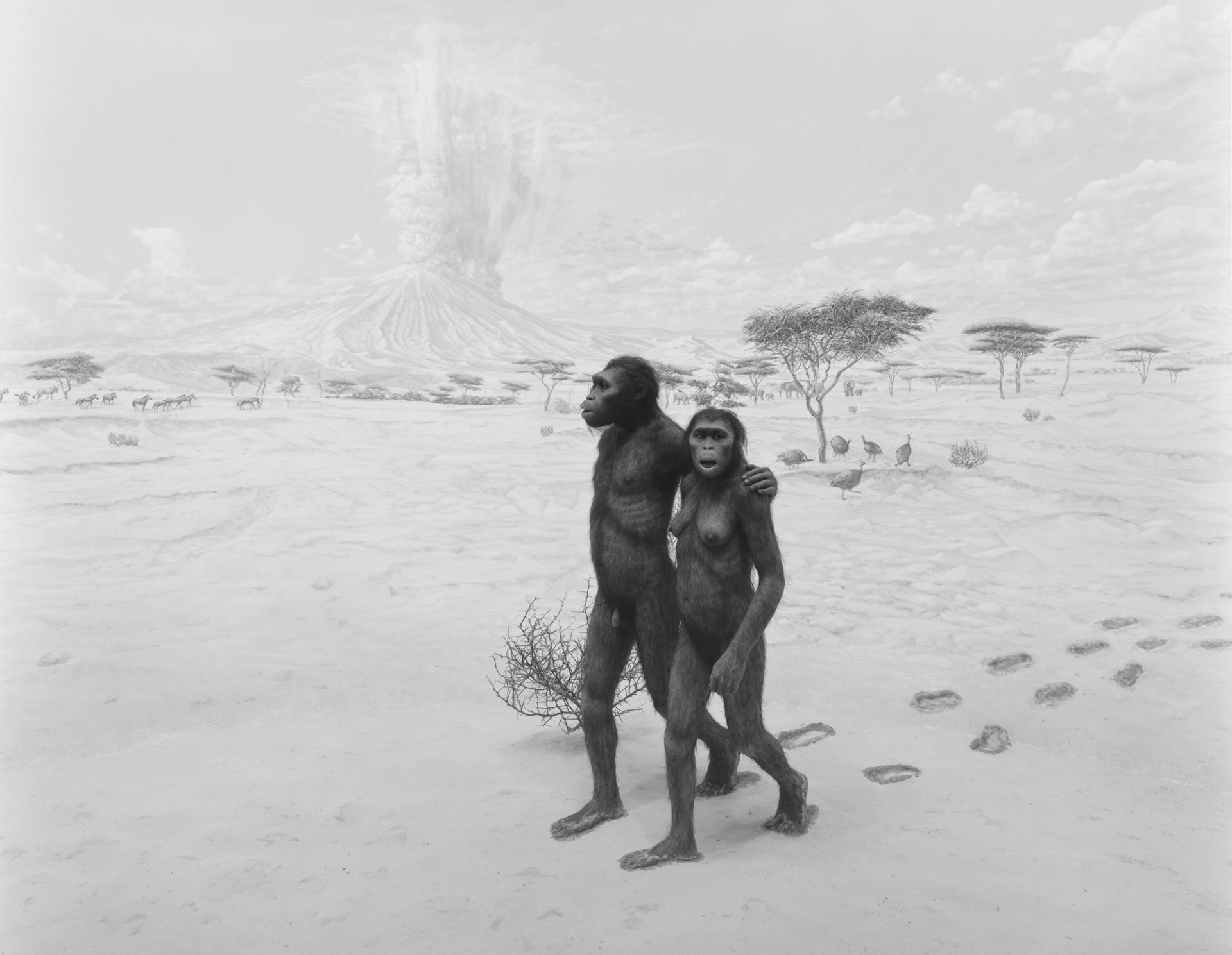

HS: Yes, yes. I reflect back [on] my memory and then I even take photographs of the dioramas at the American Natural History Museum. They have a series of dioramas of early humans. I have some pictures here—especially Lucy.

SB: Right, the Lucy photograph [“Earliest Human Relatives” (1994)]. Yeah.

HS: Lucy photograph. They used to have a diorama of Lucy [at the AMNH], but no longer because every time the scholars find a new fact, [it turns out] this was wrong, this is a new theory, and they didn’t make a new [diorama], but after ten years, some new theory comes so they have to change. So it’s just an estimation of many stories of origins of the human, which is interesting.

“Earliest Human Relatives” (1994) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: More generally, if we’re talking from a past time perspective, how do you think about the history of photography? This two-hundred-year long journey—Louis Daguerre, Henry Fox Talbot—how do you place what you do in that context?

“The invention of photography is as great as the invention of type or letters.”

HS: Yes, I owe them, those two people. That was 1839, the announcement of photography and then Fox Talbot followed. Actually, Talbot’s mother was surprised. “Wow. This is my boy’s invention and the French guy is trying to steal it.” [Laughs] But yeah, I think the invention of photography is as great as the invention of type or letters. Humans started writing and making records. And then also, probably the invention of painting is clear to the letter, I think. But that big stage of change of human history that—since photography was invented… It used to be a painter’s job to paint history, like Napoleon riding on a white horse and crossing over the Alps, that was the only way to make a visual record of history.

But then photography was invented. Photography believed that it should never be fantasized, history. That it’s not a fantasy, it’s a record of reality. But now, this no longer applies because digital photography can be changed. So only for a hundred—maybe seventy, eighty years—the police decided to use photography as proof of fact. But the police are no longer using photography as evidence. This particular time, I think, was a serious photography-practice time.

SB: The photograph is so omnipresent now in our lives. [Laughter]

Did you ever imagine it would be like this?

HS: No, people carrying the iPhone? Every meal, people photograph and send it to you, that’s amazing.

[Laughter]

Sugimoto as a child in 1957. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: Part of this conversation has to do with ancestral thinking, too. I think that there’s this idea of ancestors embedded in your work. Could you speak a little bit to that? How do you think about the ancestral line of—?

HS: Ancestral lines. I traced back my personal memory, and then I came to the image of seascapes when I was a child. Then, more and more, I got involved with the image of the seascapes. I felt like I was feeling it through, not my memory, but the memory behind my memory. It’s probably a memory of my blood. I can trace back my memories of my parents, memories of grandparents, and in hundreds of different ancestors’ stages, and maybe I came to think about, What would be the feeling of being the first man who appeared on this planet Earth? I imagined this person must be watching the seascapes, and then all of a sudden realize, “Well, I’m here. Who am I?”

This kind of ancestral memory—that came to me finally, and then I decided to photograph the seascapes. Suppose I’m the first man to be standing and facing the ocean, and then I can share this image with this ancestral image and the contemporary man—because seascapes might be the least changed places in the world. The ground, we touched it, we destroyed it, we changed it.

SB: Yeah, there’s this idea of recurring time. The water is always lapping back.

HS: Right.

SB: I was actually personally really taken with that work when I realized my own family history, in which there’s a line of ancestors in my family who come from the island of Rügen, where I know—

HS: Oh, Rügen!

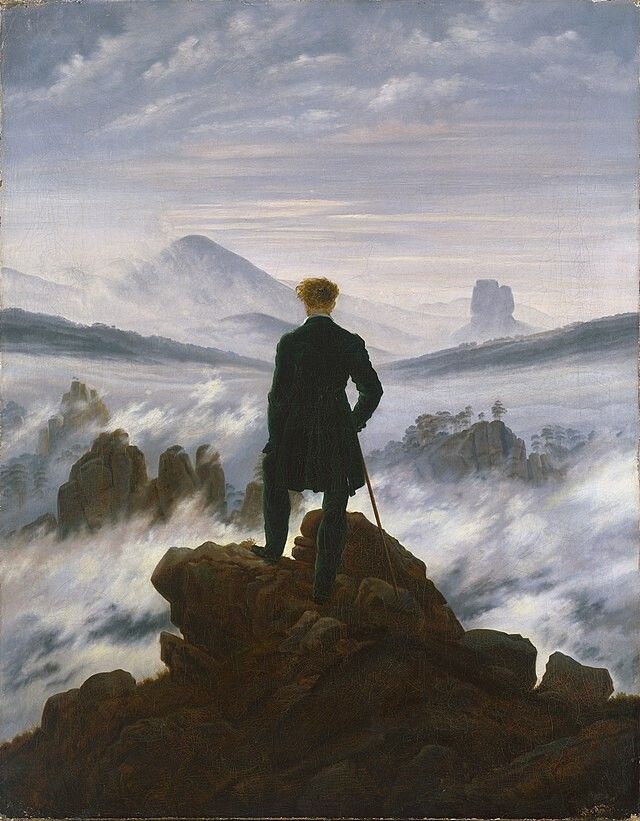

“Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (1818) by Caspar David Friedrich. (Courtesy Hamburger Kunsthalle)

SB: Yeah. Where I know that you photographed in the Baltic Sea. So when I saw your Rügen photographs, I was imagining my ancestors looking at the sea.

HS: That was intentional, I was thinking about Rügen because of Caspar David Friedrich, the German Romanticism painter who painted the Rügen island and gave me a very strong impression. So I went to see and went to find where this exact spot he painted was, and I think I found it. [Laughs] Avoiding the chalk cliffs on both sides, I just focused on the seascape between the chalk cliffs.

SB: Tell me a bit more about the “Seascapes,” and I want to get into some of your other series, too—some of which you’ve been continuing now for nearly fifty years, which is remarkable. From the “Seascapes” perspective, you’ve, from what I understand, photographed in more than two hundred locations around the world.

HS: Yeah, two hundred, two hundred and fifty. It depends how you count—on the same shore, different points. Every morning is different, but I just kept moving around and quite intentionally. Sometimes I think the direction of the sun is easy, but the moon… How big can the moon be on this particular day and which direction does the moon show up? This is a twenty-four-hour operation. I do night “Seascapes,” day “Seascapes,” morning “Seascapes.” Always I’m calculating, Where should I be, at what time or on which day? So it’s quite busy.

“Caribbean Sea, Jamaica” (1980) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Red Sea, Safaga” (1992) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Baltic Sea, Rügen” (1996) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Caribbean Sea, Jamaica” (1980) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Red Sea, Safaga” (1992) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Baltic Sea, Rügen” (1996) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Caribbean Sea, Jamaica” (1980) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Red Sea, Safaga” (1992) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Baltic Sea, Rügen” (1996) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: What do you make of all this time you’ve spent looking at the sea?

HS: I never get tired of it. Mostly the waiting time. When it’s raining, then I just have nothing to do.

SB: [Laughs]

HS: So I always bring many, many books to read and I enjoy reading. Probably the best chance is a few hours before the sunrise, and then the sky gets— You view the light, the presence of the light in very quiet, no human activities. And then slowly, the center part of the sky gets brighter and brighter and the surface of the sea reflects this first light of the day. This is the most mysterious time for me.

“I wait with my camera open; the camera is ready to receive anything, my mind is ready to receive anything, and then sometimes, a miracle happens.”

I usually wake up very early, before the sun. When I feel the light’s there, I just bring my camera out and set my camera. I’m ready to receive the message. It’s a very nice, quiet moment and listening to the birds start singing and the wind is… It’s just so meditative. I’m usually just by myself. So I just pay attention to myself. I almost, not like chanting, but I have expectancy that something might happen. I can feel it.

I just wait with my camera open, not the shutter open, but the camera is ready to receive anything, my mind is ready to receive anything, and then sometimes, a miracle happens. I think I’m very lucky. It’s very rare to get a good photograph of seascapes. People think, “Seascapes? Well, I can do it.” Of course you can do it. Please do it. Just copy me if you can.

[Laughter]

SB: This waiting time is so interesting to me, and I imagine that there’s also the time to journey to the edge to take these pictures.

“Hyena-Jackal-Vulture” (1976) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

HS: Well, I have to avoid any kind of human presence. If there’s a leisure boat or fishing boat, I can’t do it. So I end up just trying to go to places that are as remote as possible so that I don’t see any other people.

I went to Egypt, by the Red Sea coast. I rented a car in Cairo. I was told that you have a driver together with a car. I said, “No, I don’t need a driver.” They said it’s the same price. So I just rented a car, drove myself, but the car is so junky, so it’s very hard to keep it controlled. But through the driving, over the courses—how do you call it?—there were [landmines], explosives.

There are very few places that I can go to the beach or seashore. That was a beautiful Red Sea. I was wondering, Why is it called the Red Sea? I still don’t have an answer. But it was the most remote, quiet place. And then always, I encounter German people living at the edge of human civilization. Probably it’s a German romanticism. German people want to live in very remote places.

I rented a camping tent through this last German camp [near the Red Sea], and that was beautiful. I even dived in the coral of the sea was—well, the best ever I remember, the quality of the water.

SB: This was in the Red Sea you’re talking about?

HS: Red Sea. Yes.

SB: I imagine that it’s become harder to find these kinds of places where it’s so remote and there’s no human activity.

“The morning of January 1st, there are no activities. Everybody takes a break. So this is the only day I am able to take a seascape.”

HS: Yeah, whenever I go back to the same place, it’s changed. The human, I think, the quality of the nature, we keep changing it, destroying it. So I was probably the last person to be able to photograph seascapes. No longer. I quit. Except one day a year, a very particular day. I established my own art foundation, Odawara, which is one hour from Tokyo. It’s open to the sea. January 1st, morning, there are no activities. Everybody just takes a break. So this is the only day I am able to take a seascape.”

[Laughter]

SB: There’s a quote I wanted to bring up here that you’ve said about your “Seascapes,” which is: “Time crosses the seas to wash up on the shore of ideas, whereupon ideas become the beach of equations.”

HS: Beach of equations, yes.

SB: Yeah. I like this idea of this “recurring time,” but it feels to me like that endless return is impossible with all the human interference and the boats.

HS: [Laughs] Well, even without the human presence… I studied some numbers of physics: Every year, 0.00017 seconds, the time’s longer, one year. Since the creation of the solar system, one year is three hundred and sixty-five days, but it’s spinning, the Earth. So it’s slowly, slowly, slowly slowing down. Time—people think it’s very solid fixed—one hour is one hour, but actually, an hour later, one hour is really longer than one hour. We are living as a human presence. Compared to the history of life formations or the history of the solar system, we just happen to be here for a very, very short moment. Dinosaurs existed for a few million years. Human beings—well, think about it, it was, like, five thousand years ago in Egyptian times, and Jesus Christ, two thousand years ago. This is extremely short, I think. [Laughs]

![Installation view of Sugimoto’s “Aujourd’hui, le monde est mort [Lost Human Genetic Archive]” exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in 2014. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/vsgtldqf/production/044312095249b97789919d355c1863e39ea4bd26-2000x3000.jpg?w=1280&fit=max&auto=format)

Installation view of Sugimoto’s “Aujourd’hui, le monde est mort [Lost Human Genetic Archive]” exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in 2014. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

The Industrial Revolution, two hundred years ago, we started it. We’ve changed so much within two hundred years. Now, we probably are no longer able to even live in those circumstances. Everything’s happening so quickly. I may be very happy to see how it ends, human civilization itself, within my life. If this happens, I’ll be very happy to witness it.

SB: It makes me think, a decade ago, you had this exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo that got into this. You were envisioning some of the—

HS: It was a story of how our civilization would end. Thirty-three case studies. That was only, that ten years ago?

SB: Yeah, ten years ago.

HS: But now, many of my guesses have actually started happening.

SB: Like what? What are some of the—?

HS: One of the most stupid things was that we are shooting up so many satellites and so there’s debris from satellites. We can no longer go out through these layers of satellite debris. It’s getting more and more dangerous, and then people start living in satellites, the way they process your poo-poo and pee-pee. [Laughs] And then, Saturn, it’s rings of human, well, debris. Those stupid stories. It may be. Yeah, we feel the reality.

SB: These end times, you’ve talked about them through a stopping-time perspective. You’ve said, “The day when mankind will realize its deep-seated desire to bring time to a stop is coming inexorably closer,” more or less what you just said—and “Time exists only through the agency of human perception.”

HS: Yes. No other animals—maybe physically feels—but are intentionally conscious about time. So it’s very abstract, the sense of time, but definitely the sense of time. Probably early humans get the sense of time, and then realize the sun is coming up from east and going back to west and it’s circulating. And then also a sense of the seasons: spring, winter, and then come back.

“When humanity ends, there will be nobody to pay attention to time.”

So we seed the plants and wait for six months, and then it’s grown, so we can crop it. This is a civilization: We make a trap for animals and wait, and then we get the catch of something. This is a sense of time. We forecast the future and then something waits to happen. This is an imagination for the future. That’s the sense of the time.

SB: It’s hallucination, almost.

HS: Yeah, very hallucinogenic of the desire or wish. Yes.

SB: Would you say that, in some sense—not every sense, but in some sense—that time will stop when humanity ends?

HS:Humanity ends, and then there will be nobody to pay attention to the time.

[Laughter]

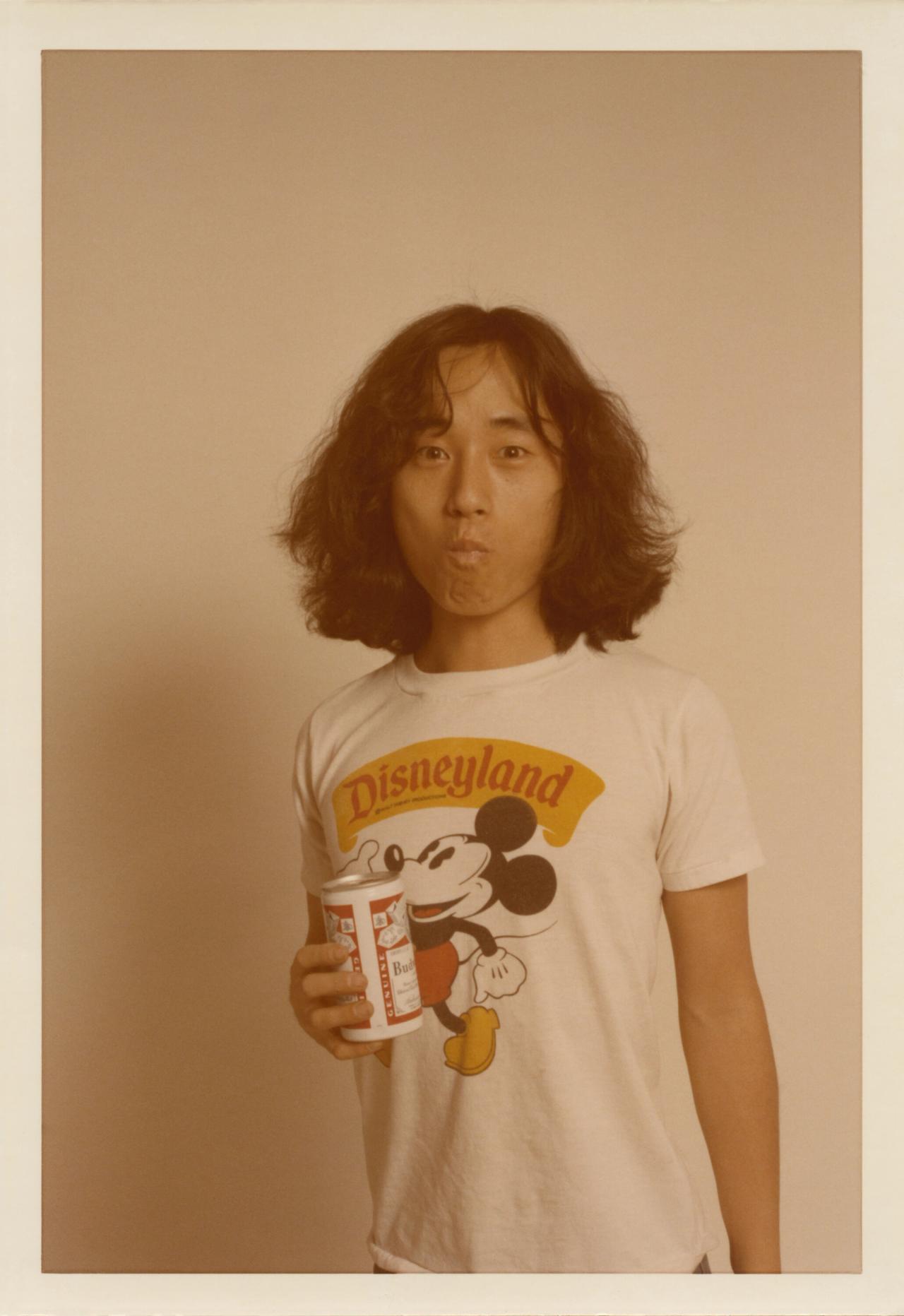

Sugimoto in his twenties. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: Well, this is a fun segue, I suppose, into your “Diorama” project, which is really a way of, it’s like taking a photo of frozen time already. So it’s stopping time twice.

HS: Right. Double frozen. [Laughs]

SB: You’ve been making these pictures since 1976. You’ve gone back to New York’s American Museum of Natural History in 1976, 1980, 1994, 1997, and 2012.

HS: Oh, five times already?!

SB: Yeah, five times. Tell me about these visits to the museum with your camera and what you’ve learned along the way.

HS: Well, the first time, I was just visiting as a tourist. So I had a 35-millimeter Nikon camera, a single lens reflex. Then I saw this polar bear first, and then that time, I was the year of, what, 24 or 25. I had hallucinogenic visions, not under the drug—at that time, it was very popular, LSD and everything—but in the very early stages of my childhood, I used to see very hallucinogenic visions. It was very strange. I was looking at the ceiling. It was a wooden ceiling with many knots there. I’m in bed and can’t sleep and looking at the knots of the wood. The knots, they’re just getting bigger and bigger, and then just flip me into a totally different world. It was scary, but I enjoyed it, just to let it happen. My vision changes.

I became like a child with this vision that reality itself is so fakely made up. This is just a very thin dance of my vision. There’s no solidness, no solid, the vision. It’s like a movie projection. It’s a fantasy only being shown as a fake vision. To me, there was no solid reality at all.

So when I saw this diorama, well, this is exactly what I always see it. It’s very thin and fake, and then maybe I can make it look like a live, fictional vision, but so real. I closed one eye, and I imitated myself as a single-lens camera. Cameras always have one lens, and the human has two lenses, so that measures the distance with two lenses, but the camera has only one lens. So when I close one eye, then I lose my sense of distance. That gives reality. So once anything is photographed, people tend to believe it. Photography is a sign of existence. I can use this technique to—even after twice frozen—bring the dead back to reality.

“Photography is a sign of existence.”

I was thinking quite philosophically, I was thinking the theory. So let’s try it, and use the highest quality camera ever being used, which is an eight-by-ten camera, which I can test it. But how can you prove that this is what I want to do and who will help me in to let me test my idea? I cannot convince any museum people that time. [Laughter] So I just called up the museum. I just asked, “I’m a tourist and I want to bring my camera in. Can I photograph it?” They said, “Well, of course, yes.” So I had approval.

So I brought in just by myself, it was a huge eight-by-ten camera, and then cut the reflection with the flag tent. Of course, the security came, “You have permission?” I said, “Of course I have.” [Laughter] This guy trusted me. I was quite lucky. I was probably easy to be kicked out with this huge production. So I was able to take three pictures. Amazingly, the way I imagined them is exactly what happened. First one was a polar bear—it looked so real. People couldn’t believe it. “Wow, you’re a nature photographer!” [Laughter]

“Polar Bear” (1976) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB:National Geographic.

HS: Yeah, so close. You are so brave.

[Laughter]

SB: Well, the “close” part’s true.

[Laughter]

HS: Yes. Only like a few, four or five feet away, with this wide-angle camera lens.

“Usually, a photographer goes out and hangs around and shoots so many things, but mine is to make my vision happen.”

SB: Well, I think it’s interesting that you mention this term “fake vision,” because I think in a way, so much of your work is playing with that—what’s real, what’s fake. And the next project—or projects, really—were “Theaters” and “Seascapes,” and the “Theaters,” of course, were where you would photograph entire films in a single, long exposure. These films, of course, that became a part of the public, national, sometimes international consciousness—what was it like for you to play with the idea of vision through the “Theater” series?

HS: This was also the start of my imagination. I always ask myself, “What if?” So that particular night’s question was, “What if I photographed the entire movie?” Then the answer came to me as a vision. It must be the white screens, brilliant screens, overexposed, technically. Then just all the images become a white light—quite shining white light—and then we enter inside of the interior of the theater. So I envisioned it. Somewhere from upstairs—it just came to me. Even a religious kind of feeling I felt.

So the next stage is to make it happen. Usually, a photographer goes out and hangs around and shoots so many things, but mine is to make my vision happen.

“Teatro Comunale Masini_Faenza, 2015, Le Notti di Cabiria (Screen side)” (2015) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: You’re almost seeing it before you make it.

HS: I’ve seen it. So I went to the cheapest movie theater, Cinemark Cinema, on Eighth Street and Third Avenue. It’s no longer there. A one-dollar theater, it used to be. So I snuck in with my eight-by-ten camera and set it from the corner, because the center is a projection room. The guy is watching me, so I have to hide myself. And then there’s no way for the exposure, eight-by-ten camera and a one hundred sixty millimeter, quite wide angle lens.

The f-stop was just wide open, f-16, that’s a not so bright lens before the eight by ten, and then I don’t remember the movie at all because I wasn’t watching it. I just kept hiding the screen so that I can be able to see the other details, and then just processed it at night. It just showed up, the vision that I had envisioned. I amazed myself.

If I get at least one sample, I can show it to the movie owners, “This is what I want to do.” So it’s getting easier and easier and I contacted the United Artists group that time, the movie theater chain. And then I discussed with the manager, “No, you cannot do it because we have a copyright of the movie.” I explained, “There’s no problem, no image shows up. It’s just a white light.” And I was able to convince this manager. So that’s how it started.

Now, I can place my camera where I wish to be, in the center. And then I gave them the first copy of the prints, twenty by twenty-four, maybe five, six, seven in the series. I remember, none of them they kept in a good condition. They just pinned them up on the wall. [Laughter]

SB: Like a celebrity photo or something.

[Laughter]

HS: Yes, I saw, one time, that they put the phone numbers on the screen. It might be valuable now if I can be able to find it.

[Laughter]

SB: It’s so interesting to me that, technically speaking, a film is hundreds of thousands of still images and you’re capturing just this one, and the one that you capture ends up effectively creating a void.

“A film is just a series of chains of single images accumulated that gives the illusion of movement.”

HS: A void.

SB: You’re almost staring into this void of Hollywood culture, which is fascinating.

HS: The movie was invented after the photography invention. It’s just a series of chains of single images accumulated that gives the illusion of movement. So it’s, again, double-killed, twice-frozen.

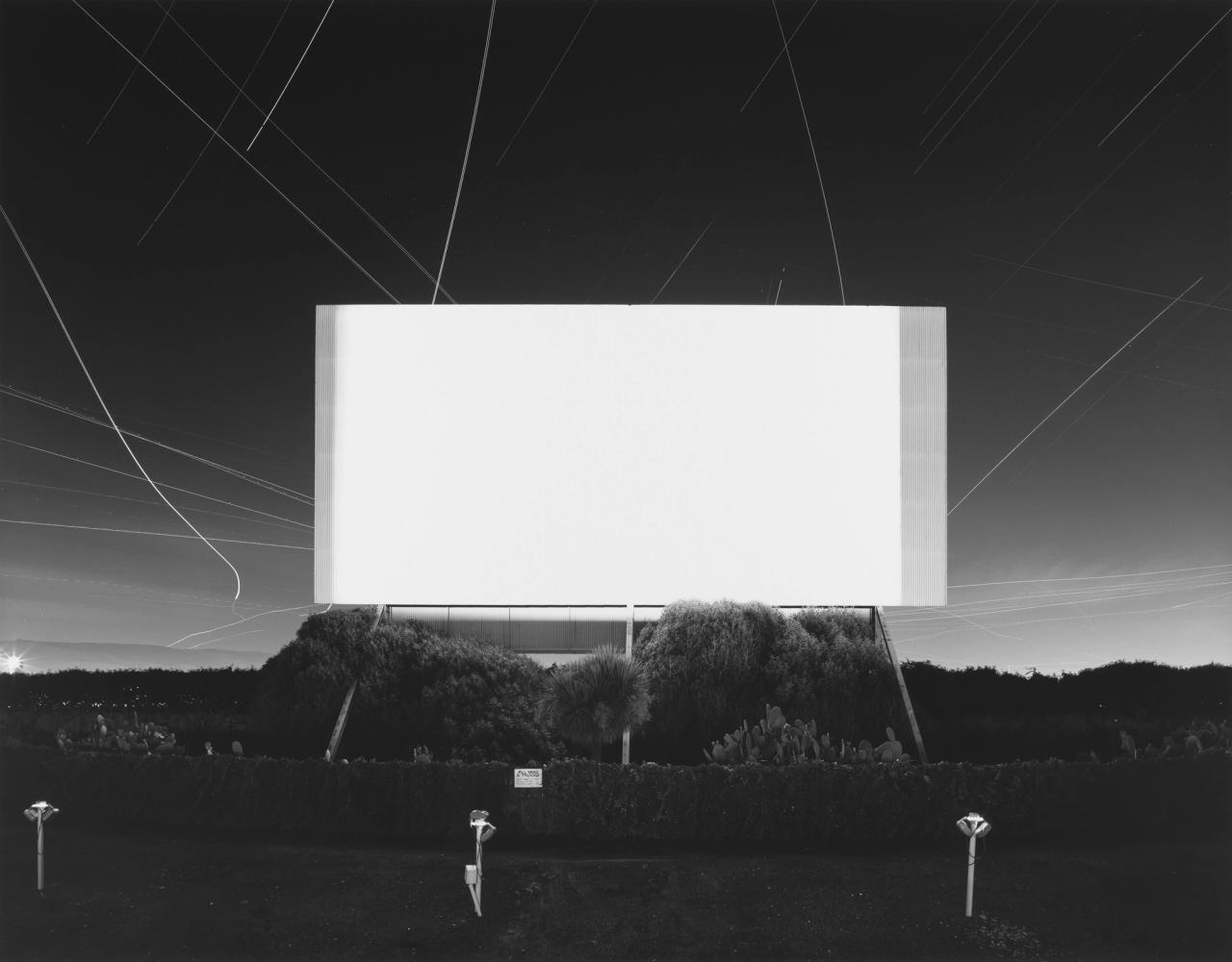

SB: And this project evolved into, effectively, three other series. You had the “Abandoned Theaters”; the “Opera Houses,” which is a little different, but connected; and the “Drive-In Theaters.”

HS: “Drive-In Theaters.” Yes.

SB: Now that you’ve been making these pictures for these five decades, what do you make of the time you’ve spent in these theaters and watching these films and capturing these spaces and images?

“Union City Drive-In, Union City” (1993) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

HS: Well, again, in the early stages, it’s very, very difficult to get good images. For four or five years, I studied what… Sometimes, it’s not sharp, even though the focus is quite focused. What happened is the temperature changes within film packed outside the theater. When you bring it in, it’s usually warmer. Film moves within the film holder, so I have to make a special film holder to tape it onto the holder. That took four or five years to discover.

So it’s getting better and better, and also the exposure—you cannot use the exposure meter. I have to guess how bright this movie was. In psychological movies or there’s a movie, very dark movies, and sometimes, the Western movie, the cowboy movie, mostly shot outside. This gives me more and more exposure, which means smaller f-stop. I get sharper images.

And then, finally, I try to get the architecture from the theater. Usually, a theater is a rounded shape, and then I just measure the walls and distance from the screens and decide my camera position where it can be an equidistant position, which means I get the sharpness everywhere. So it’s many factors and many discoveries. Maybe after ten years, I’m almost in the best position I can find and my guessing ability of the movie’s brightness.

The problem is that most of the movie theaters change—every show, you have four or five different kinds. Even if I take one exposure, but if the next movie is a dark movie, then I have to wait until the next day for the same movie and it’s not easy. I was very, very patient.

SB: You mentioned this religious feeling earlier, when you were talking about the—

HS: My vision, yeah.

SB: Yeah. And I was thinking about how, on some level, there is a sacredness or religiosity to so much of your work. Do you see it that way at all?

HS: Well, I hope to see it. But if you’re wondering whether I’m religious or not— I think I’m quite religious, in a sense. I think I’m spiritual, and some type of spirits keep descending on me. So I’m just followed by the voice of some spirits. It’s coming from deep inside of me or deep outside of somewhere. I don’t know. I think I have a capacity to receive these messages from somewhere. Then they tell me what to do, and I follow the order.

“There used to be no human will. The human will is quite recent, the last maybe thousand years or two thousand years.”

This can be religious, I think. Ancient people probably were able to listen to the voice of God, and then they followed. Reading the Greek poets and Romans, they were always paying attention to the messages coming from somewhere, and then they just acted according to the message. So there used to be no human will. The human will is quite recent, the last maybe thousand years or two thousand years. So I don’t trust myself as an artist: “I’m an artist; I’m like a God. I can create from nothing.” No, I’m waiting for the message. I’m only the tool to act it out.

SB: You’re channeling.

HS: Yeah, I’m channeling. [Laughs] God’s invisible hand. I’m just God’s invisible hand. [Laughter]

SB: I also wanted to talk about your “Architecture” series here, which started in 1997, where you abstract or, really, blur these—if I could call them that—iconic pieces of architecture, whether the Brooklyn Bridge, the Chrysler Building, the Seagram Building, the World Trade Center even. Where does time come into it for you with these pictures? There is a sort of—at least how I see it—a timelessness that is evoked by taking these iconic forms and abstracting them, blurring them.

HS: Right. This is the first commissioned work [I ever did]. I never [previously did] the commissioned work because I don’t want to work for someone else’s idea, but this was the MOCA [Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles], I remember. They were planning to exhibit twentieth-century architecture. At the time of the end of the century, they wanted to see, what was architecture in the twentieth century?

SB: 1997, this is the—

HS: Yeah, 1997.

Sugimoto’s sculpture “Point of Infinity” (2023) installed on Yerba Buena Island in San Francisco. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: This is the exact year that Frank Gehry’s Bilbao was unveiled. It was a very pivotal moment in architecture.

HS: Right. Well, I decided to take this job, and I was particularly questioning, well, what was it? What was modernism? What was the modernist movement, especially architecture? So I traveled around the world, picking the most famous buildings—Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe. And then I decided to give—again, the theory comes first.

So I came up with the theory. The concept is “twice infinity.” This is an impossible focal point. I can go beyond infinity, because my eight-by-ten camera has no stop at infinity. Infinity means if you use a 300-millimeter camera, the space between the lens and film must be 300 millimeters. Then that’s the infinity point. But what if I just press it, instead of 300 millimeter, 150 millimeter? That’s supposedly twice the infinity point, which is not in this world. It’s somewhere else. Automatically, it gives me an out-of-focus picture.

Then I think about the architect’s imagination. The architect usually probably imagines the ideal shape of the building before the actual building has been built. Then the architect is fighting with reality, the budget, and the client’s demand. So the actual building is usually less interesting than his imagination. So to give the twice as infinity focal point, it brings back the most ideal state of the shape of the architecture. That’s very ironic. It can be a statement and it might be even more beautiful than the finished building—that was my concept.

“Chrysler Building” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Seagram Building” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Villa Savoye Le Corbusier” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Eiffel Tower” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Brooklyn Bridge” (2001) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Leaning Tower of Pisa” (2014) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“World Trade Center” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Chrysler Building” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Seagram Building” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Villa Savoye Le Corbusier” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Eiffel Tower” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Brooklyn Bridge” (2001) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Leaning Tower of Pisa” (2014) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“World Trade Center” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Chrysler Building” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Seagram Building” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Villa Savoye Le Corbusier” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Eiffel Tower” (1998) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Brooklyn Bridge” (2001) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“Leaning Tower of Pisa” (2014) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

“World Trade Center” (1997) by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: Yeah, it’s dreamlike. There’s almost a dreamlike aspect.

HS: Yes. Especially the World Trade Center, that building wasn’t so well-received from the historians of architecture, but I liked it. I loved it. That was only two, three years [before 9/11], 1998, I was able to photograph—I rented the suite room, top floor of [The Millenium] Hilton hotel, just across, which was fifty-stories high, and this is a hundred and ten-story. So I was just in the center in between the hundred tens and fifties. Beautiful angle.

SB: Obviously, 9/11 happens.

HS: 9/11 happens.

SB: What’s it like for you to look at those pictures now?

HS: It turned out to be a very ghostly picture. It actually became a ghost. I was watching the tower just crashing in front of my eye. My studio is on 26th Street. I went outside on the roof and watched the two buildings burning, and all of sudden it’s crushed. This is something, the turning point of history, I think.

SB: I think your pictures become all the more poignant in that sense. You look at the Leaning Tower of Pisa or the Eiffel Tower, and you almost imagine a world without them. There is a ghostly presence.

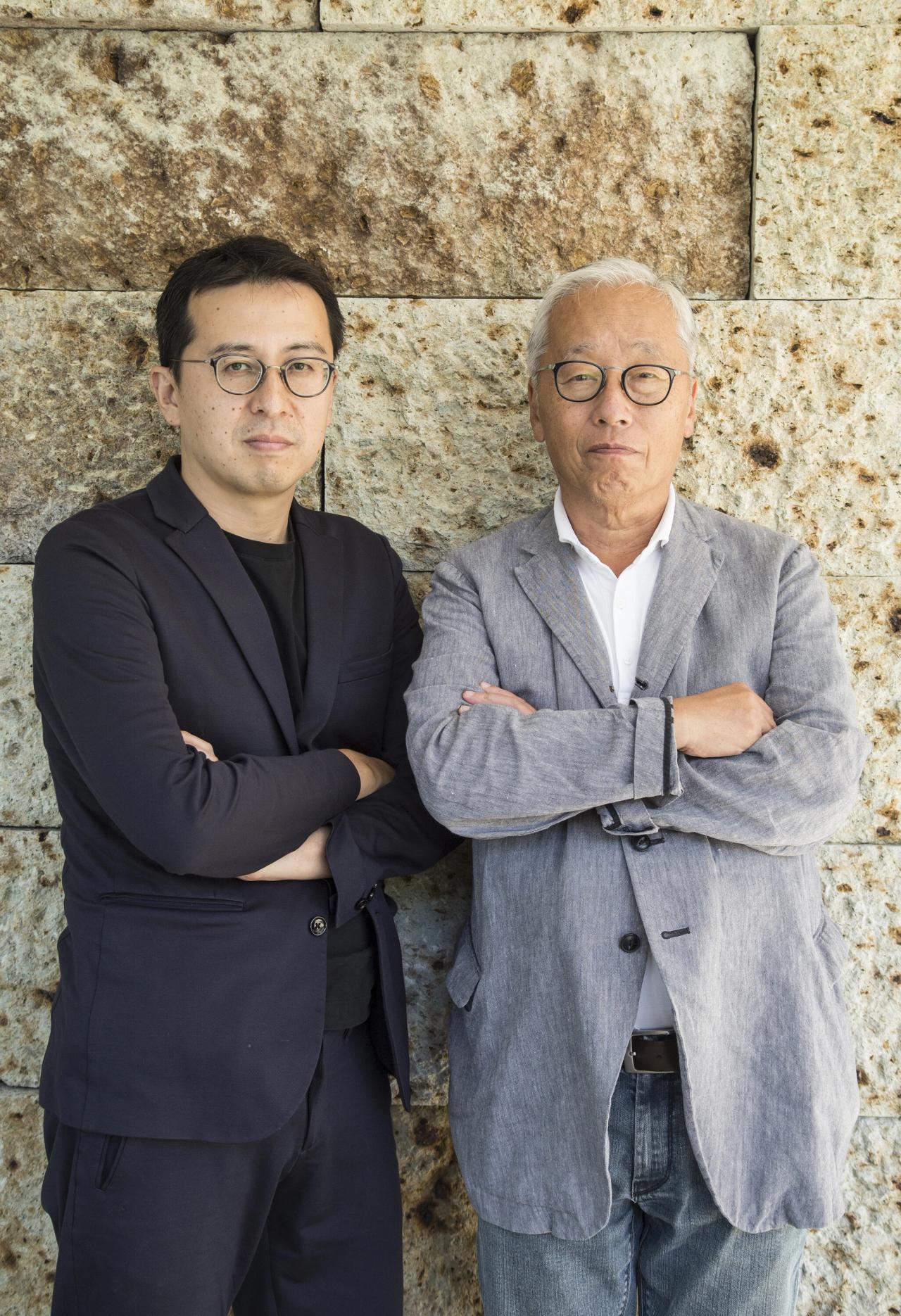

Sugimoto (right) with Tomoyuki Sakakida. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

HS: Yes, and I photographed new ones, but they’re not as elegant as before. So that was a turning point. We are declining. It’s just going down, downwards now. [Laughs]

SB: Well, I think we should mention, while we have the time, that you also practice as an architect. [Laughs]

HS: Yes. It’s very ironic. [Laughs]

SB: And I like the ironic name of your firm, New Material Research Laboratory, which you run with Tomoyuki Sakakida. You’ve said, “What I aim to achieve in architecture is not deterioration and degradation, but simply for plain materials to reveal, through the passage of time, a more sublime fact with a more lustrous patina.”

HS: Yes.

SB: Elaborate on that a little bit.

HS: Yes. So I became a collector of antiquities, especially Japanese Shinto and Buddhist sculpture. In that sense, I’m tracing up my memory and the architectural point of view, the old buildings, Buddhist temples, the wooden structures, even from the eighth century, this remained beautifully patinated, and then the structure was simple, but the simple is better. This is a modernist kind of concept.

I collected fragments of old buildings, sometimes old pieces from the eighth century, ninth century, tenth century. It’s painted once and then beautifully peeling off, and it just shows the passage of time, of thousands of years. And the walls, the stucco walls, of course it’s more beautiful than just paint on sheetrock. So more and more, I go backwards to recreate the craftsmen. I can still find the craftsmen with stucco and carpenters, but now it’s almost disappeared—it’s endangered species. People don’t pay much attention or money; it’s easier to paint rather than just making stucco walls. So I felt, Well, this is an endangered species. I want to work together. I want to save them and keep continuing the technique.

So I established my architectural firm. I had no intention to be an architect, but since I commissioned the renovation of Shinto shrine in Naoshima, on the Benesse Island—that was 2001 I commissioned and started working 2002, spent a few years and using all the material. This was a nineteenth-century Shinto shrine, but still to make it refurbished, the way I want, I added my own structures. I was quite pleased to be able to do that. Since then, a friend of mine started asking me, “Well, will you design my space? Will you design my garden?” I just started doing it as a hobby, side job. But the projects were getting bigger and bigger. Finally, I was commissioned to do one small museum, and then the general contractor, I have to sign the contract, but I can’t because I’m not a licensed architect. So I decided to work together with Sakakida, who was a young guy, my son’s age, but he had a license. We started this small architecture office, and we are still doing it.

A rendering of Sugimoto’s design for the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: Yeah. You’ve since created Enoura Observatory, and you’re now working on the Hirshhorn Museum Garden.

HS: Right. That’s a government job. That’s a pain in the ass. [Laughter]

SB: Well, the Smithsonian certainly does have its bureaucracy and it is on the National Mall, so….

HS: National Mall, and it’s been eight years. I make my plan, and there’s a movement against me. I don’t know, it’s the National Mall—because my nationality is not American. There’s many things, and paying respect to the original [Gordon] Bunshaft design. There are people, yes, against my project. So there was a debate for many, many years. Fortunately, the Washington Post and The New York Times sided with me. So finally it’s approved.

SB: It’s happening.

HS: It’s happening. Yeah, groundbreaking is happening this year.

SB: That’s great.

HS: I kept saying, if someone disliked me, please let me go. I don’t want to work under this condition—I’m an artist. But once I stepped in and the program was approved, then I cannot escape. But now, I’m happy that it’s finally happening.

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

View of the Enoura Observatory in Odawara, Japan, designed by Sugimoto. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Interior view of the Shokin-Tei teahouse at the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, Japan. (Photo: Jan Sobotka. Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: You and I share an affinity for a specific work of architecture, the Katsura Imperial Villa.

HS: Ah, Katsura Imperial Villa!

SB: Which I feel like is worth bringing up in this context. It’s this seventeenth-century villa in Kyoto.

HS: Yes.

SB: I think, from a time perspective, it’s one of the most remarkable examples of architecture on earth. Fastidiously maintained, and also, I think, in terms of understanding architectural history and its influence on modernism in so many ways.

HS: Ahhh. Yes, yes. Bruno Taut came and then he came by boat to get to the Japan Sea coast, but the next day he traveled, there was a group of Japanese who planned to show him what’s the best. The Japanese took him to the Katsura Villa, and he was so influenced. So he made the message to the modernists, to the European architects. This was the beginning. Then this simplicity, in a modernistic sense, was already established in the early seventeenth century. So the Japanese are proud of the discovery of the modernist sensitivities in its history.

Installation view of Sugimoto’s exhibition “Hiroshi Sugimoto: Five Elements in Optical Glass” (2011) at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: Just fast-forwarding many, many years to the early seventies, when you made New York your primary residence. I understand that you saw this Donald Judd exhibition that completely reshaped your mind around wanting to become an artist.

HS: Right. Yes. It’s like Bruno Taut meeting the Katsura Villa. It’s the same thing that happened to me in my mind.

SB: Yeah, and I see what you’re building at Enoura, and it makes me think of some of what Judd aspired to do in Texas, with Marfa.

HS: Ah, Marfa. Yes, I’ve been there. I was invited to do my show once [at the Chinati Foundation], even after his death, but I was quite impressed. And then, yes, that Judd plywood box show changed my life.

SB: What are your hopes for Enoura, say, a hundred years from now? What do you see this being?

HS: Well, I always say the target of completion is five thousand years from now. How beautiful can it be as a ruin? Like how we look at the Pantheon and the pyramids. It’s so beautiful. So I don’t know who will be able to see it in five thousand years, whether human beings are still present here or not, but I don’t care. Just imaginative ruins, that’s my final vision for my Enoura. This is my last piece. I’ll just keep making it till I die, and I will try to spend all my cash to make this as beautiful as possible. So my idea is a financial idea: I want to die with a cash balance of zero. I spend all my wealth to make another art as my foundation.

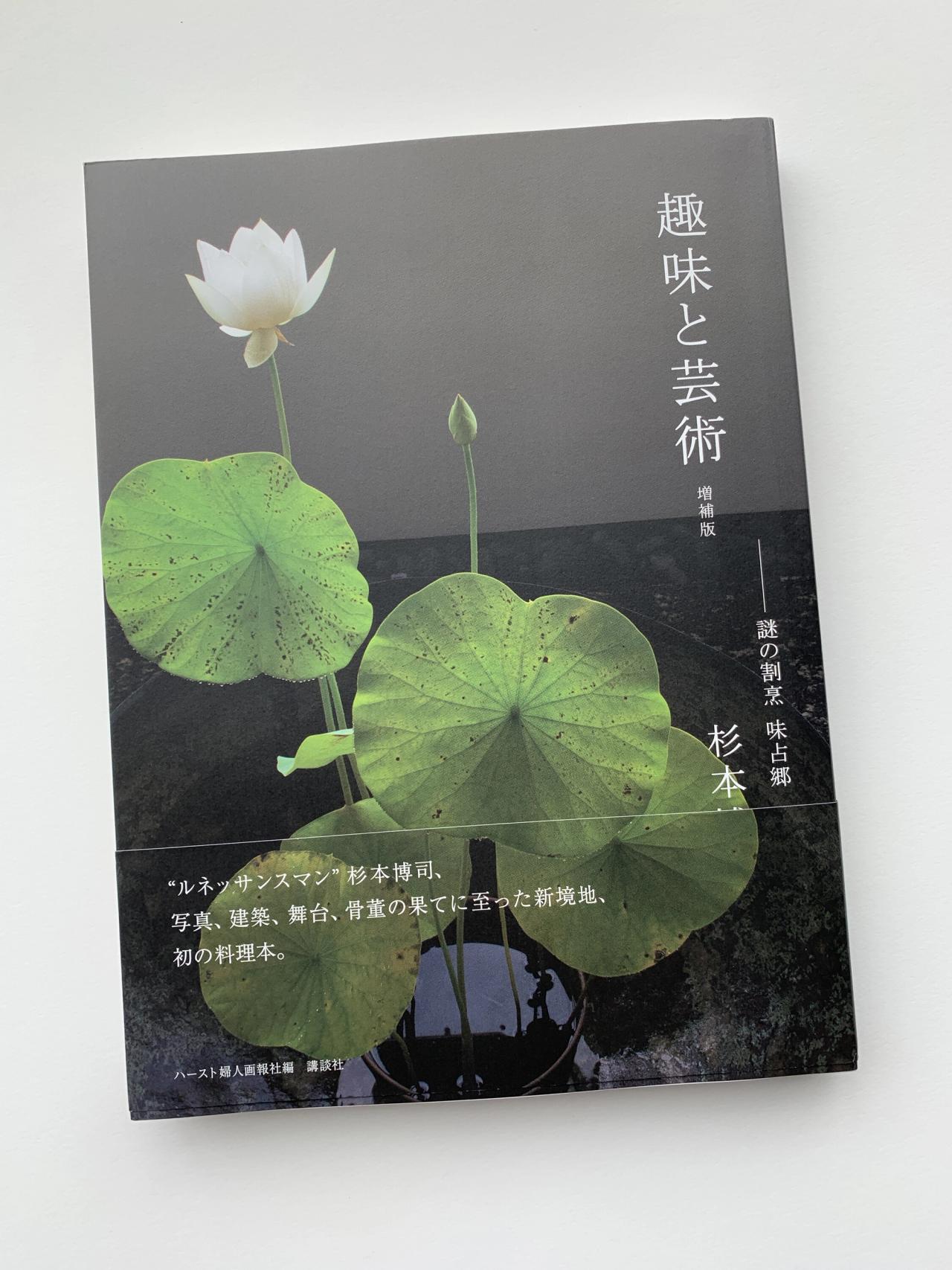

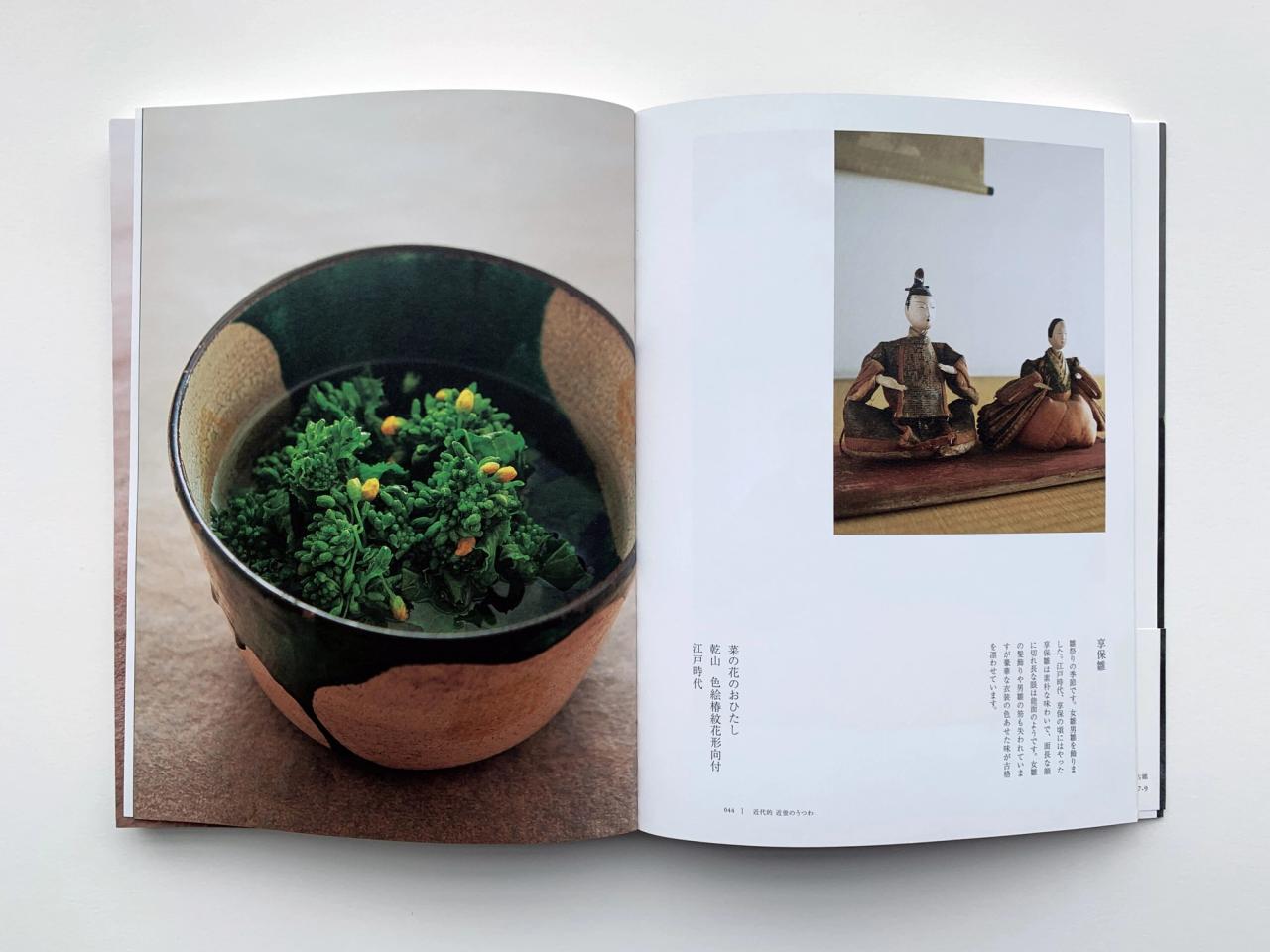

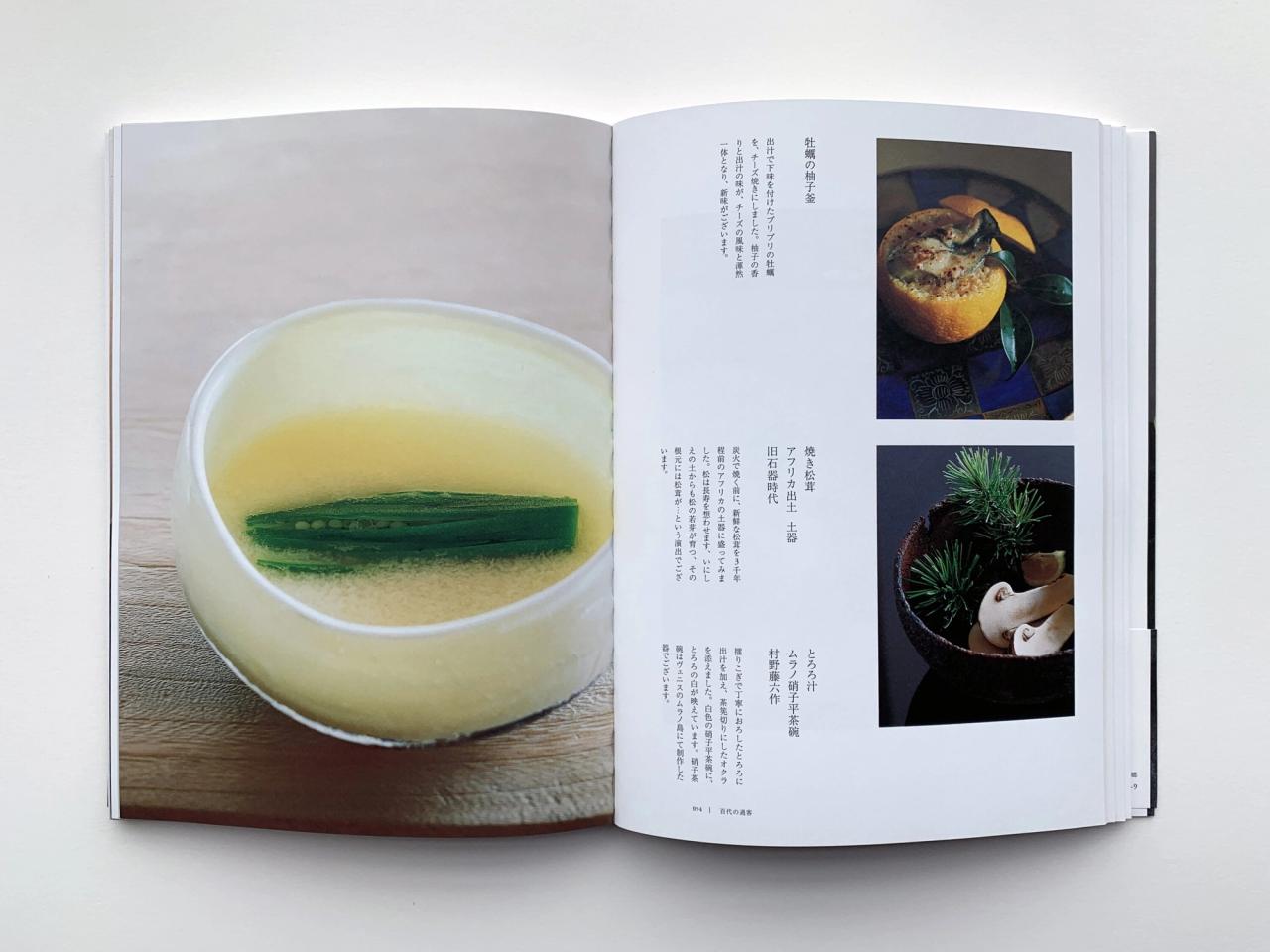

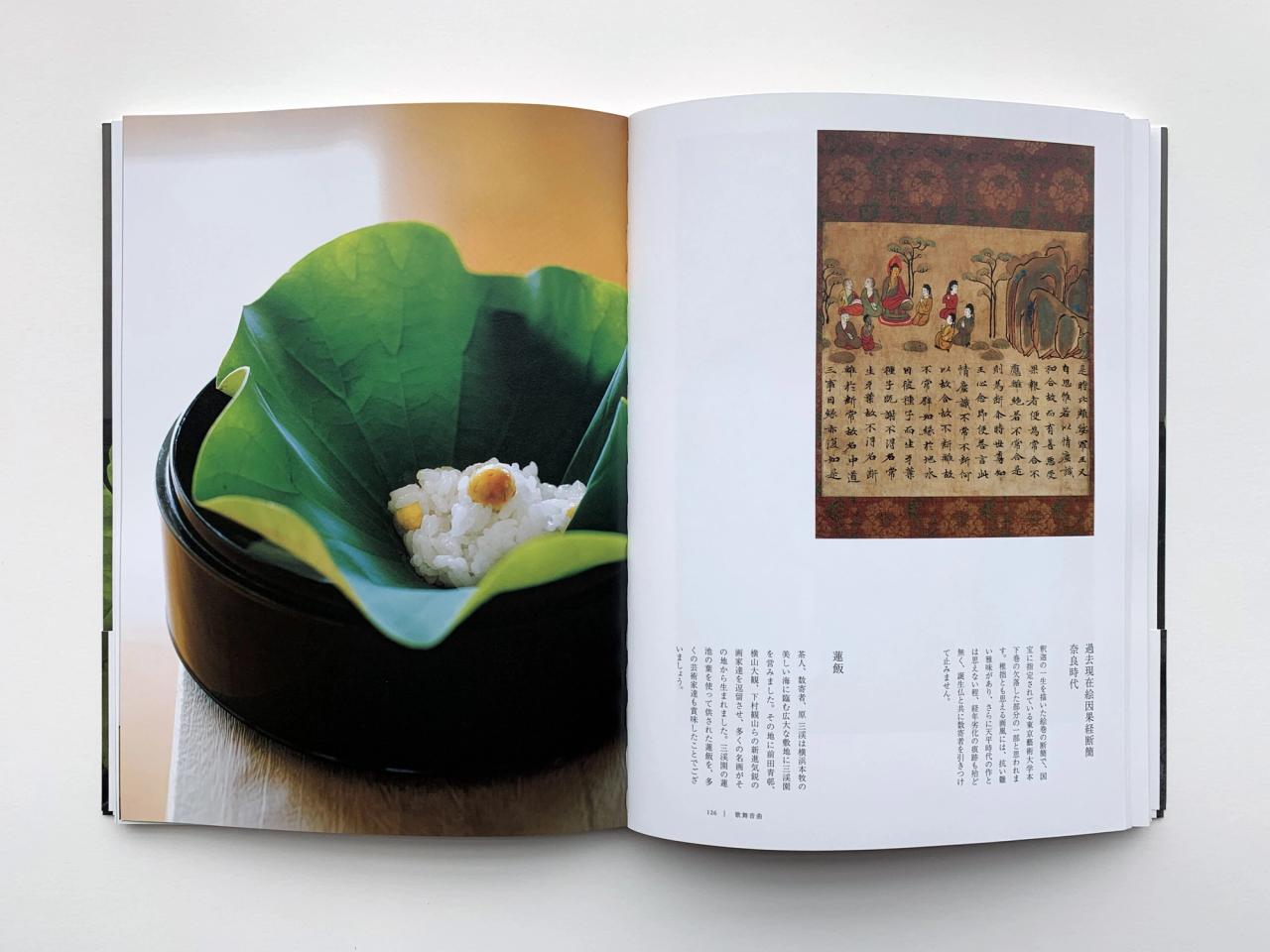

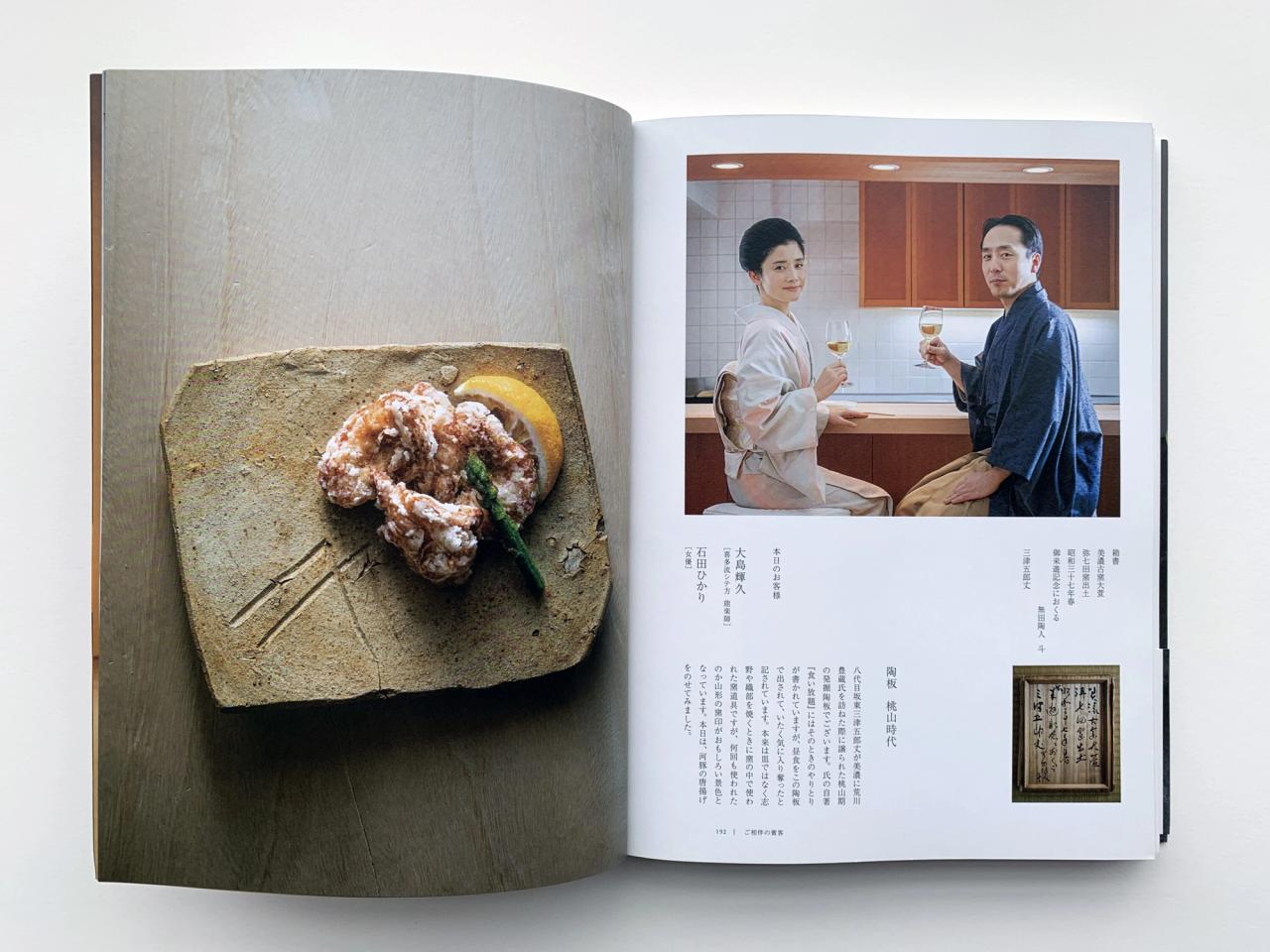

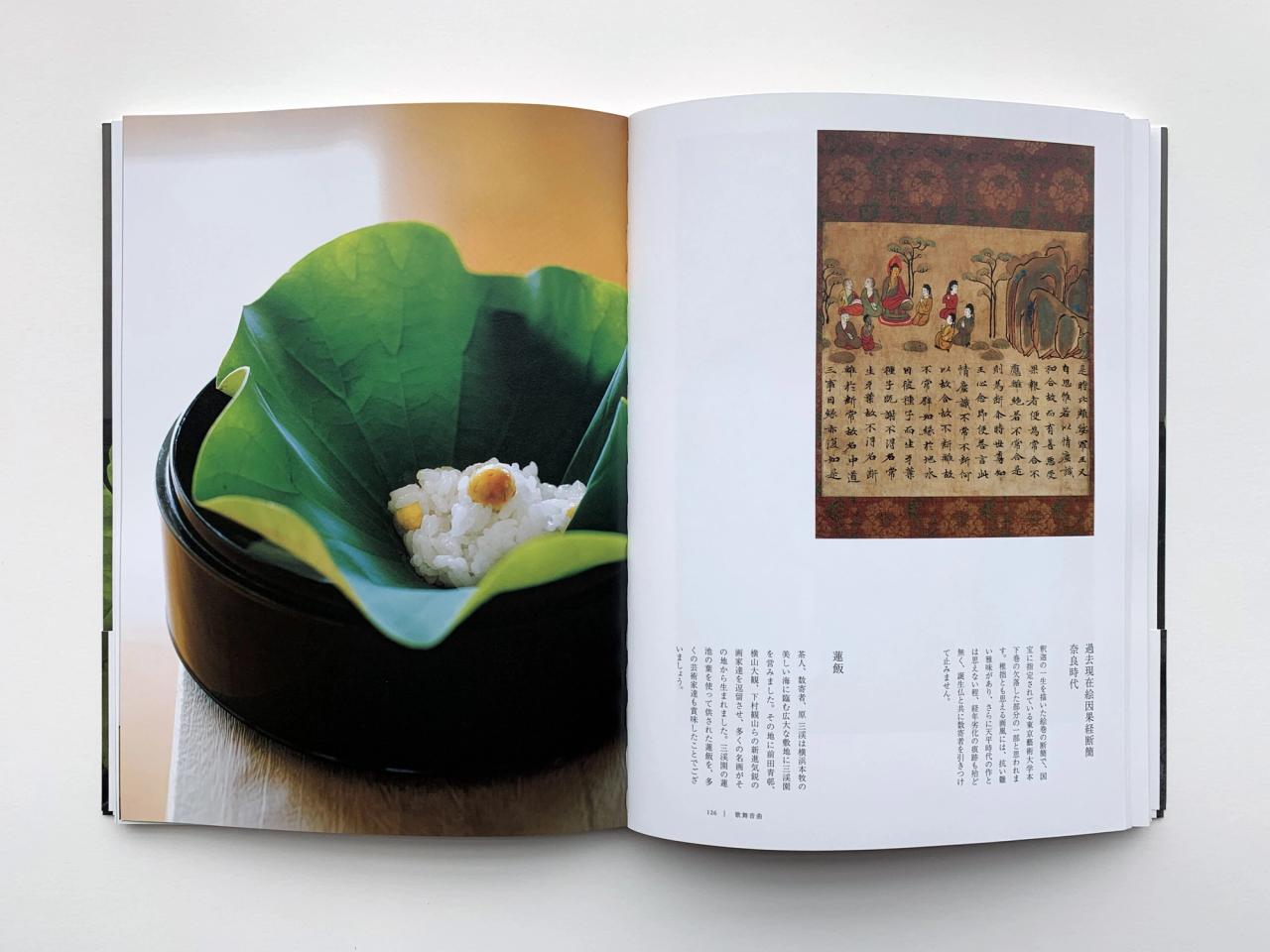

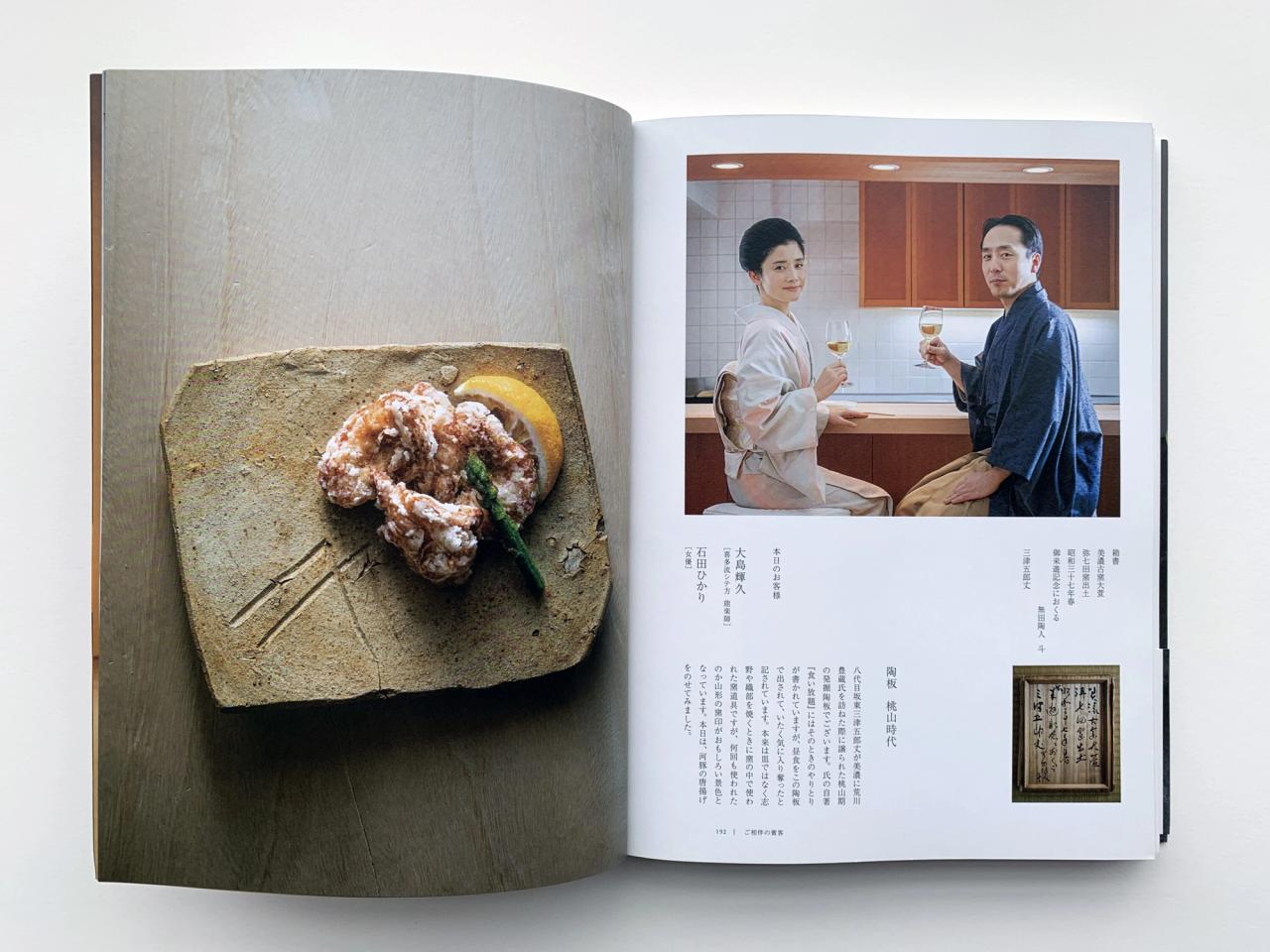

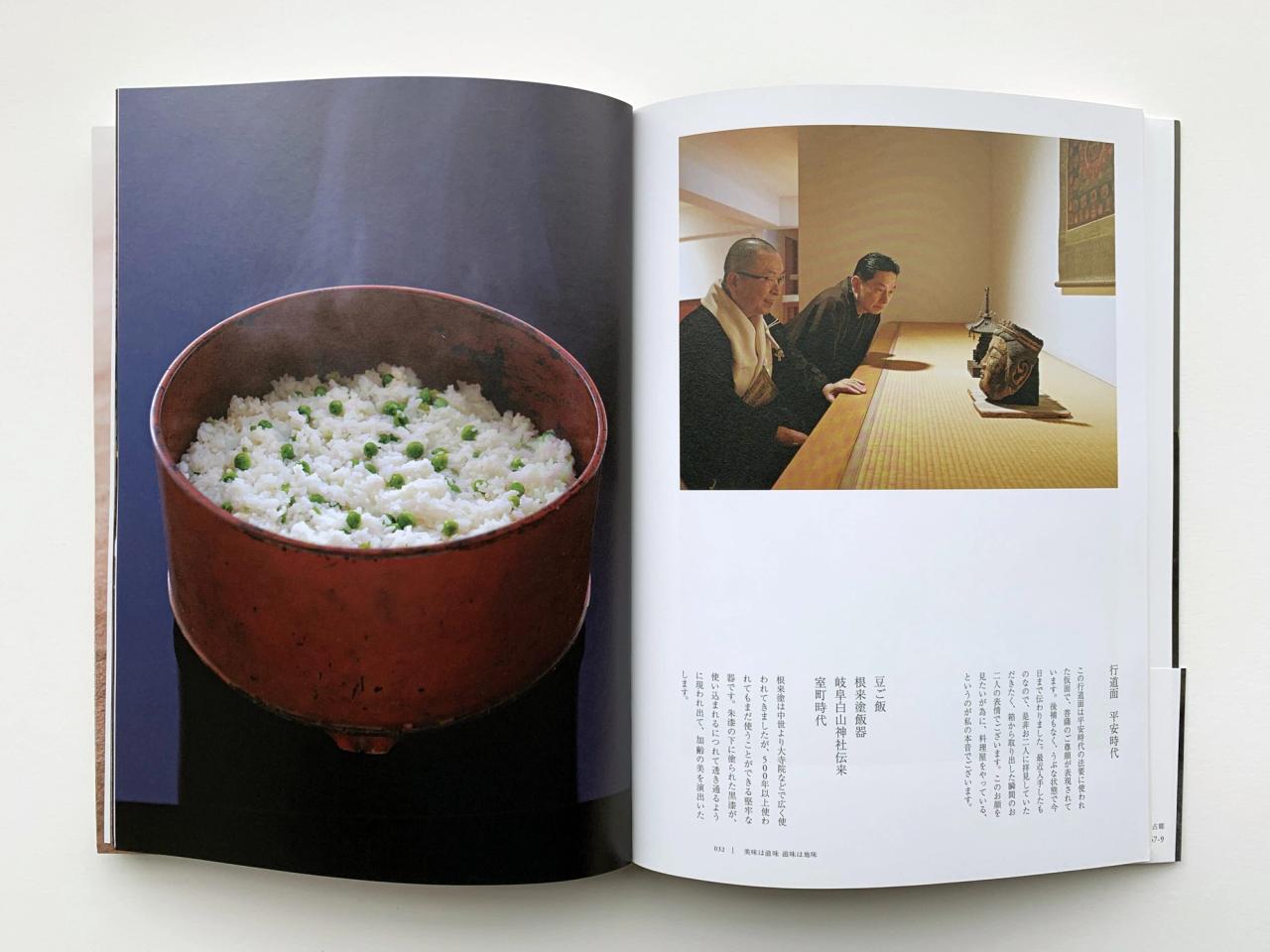

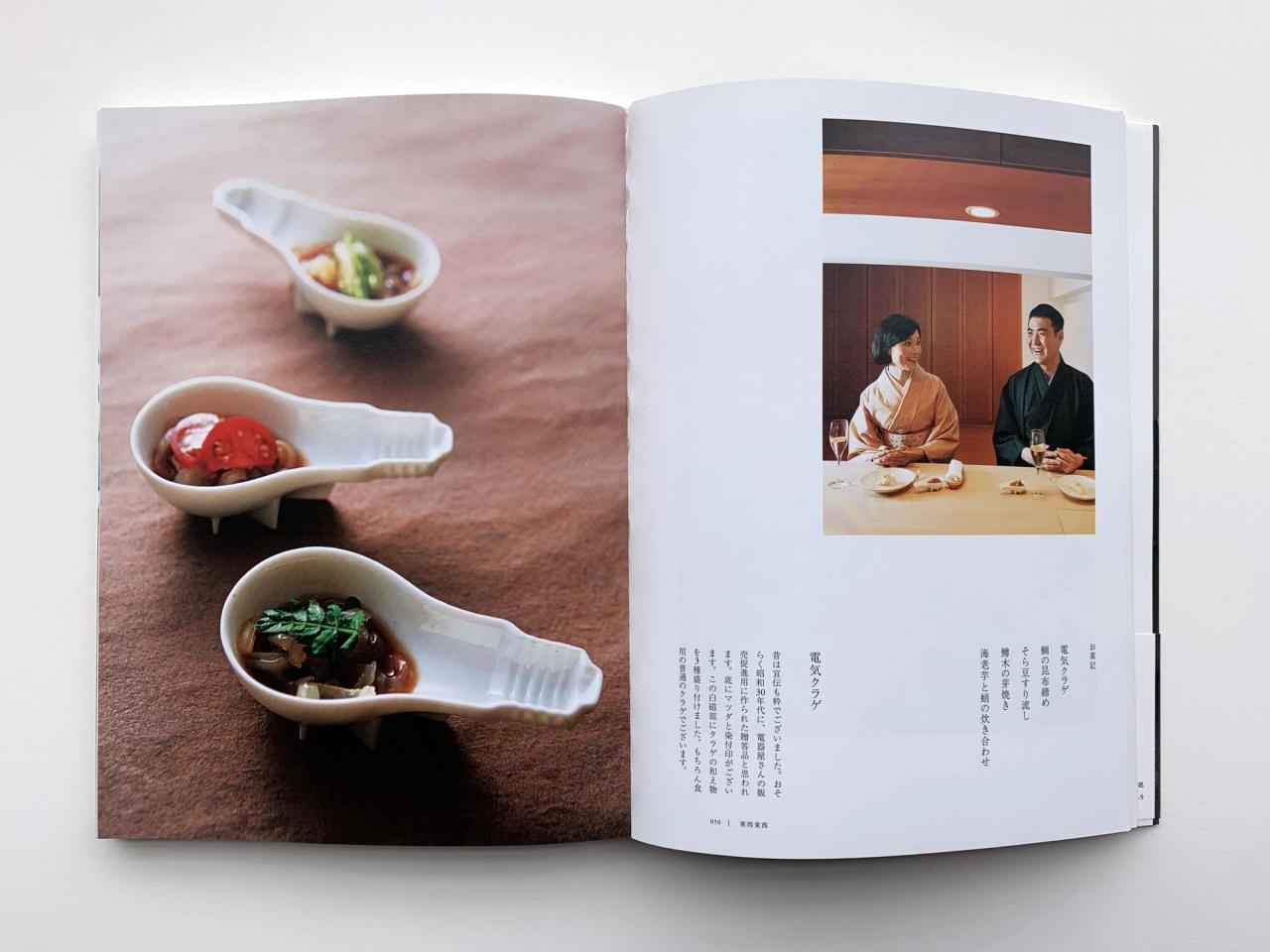

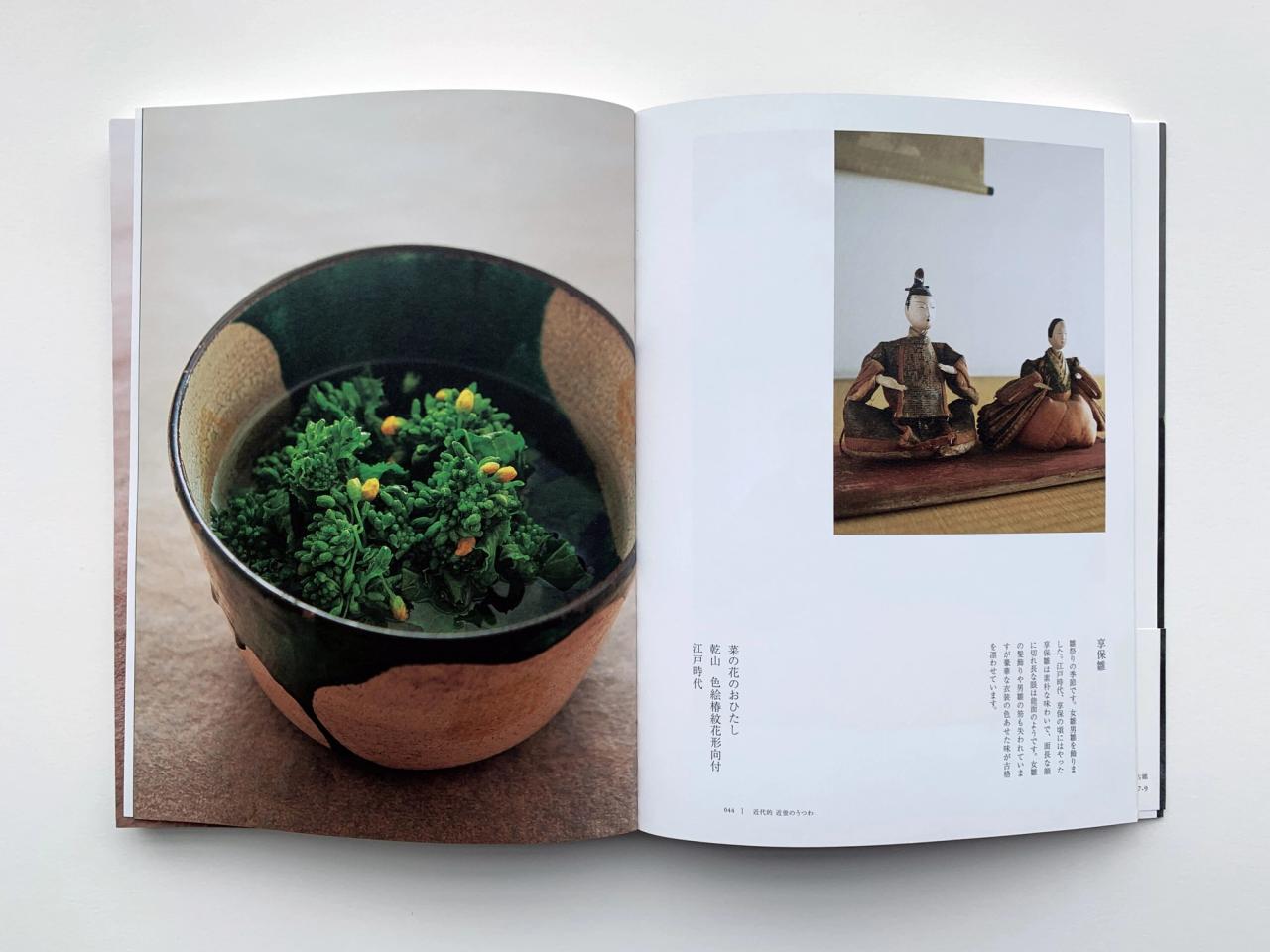

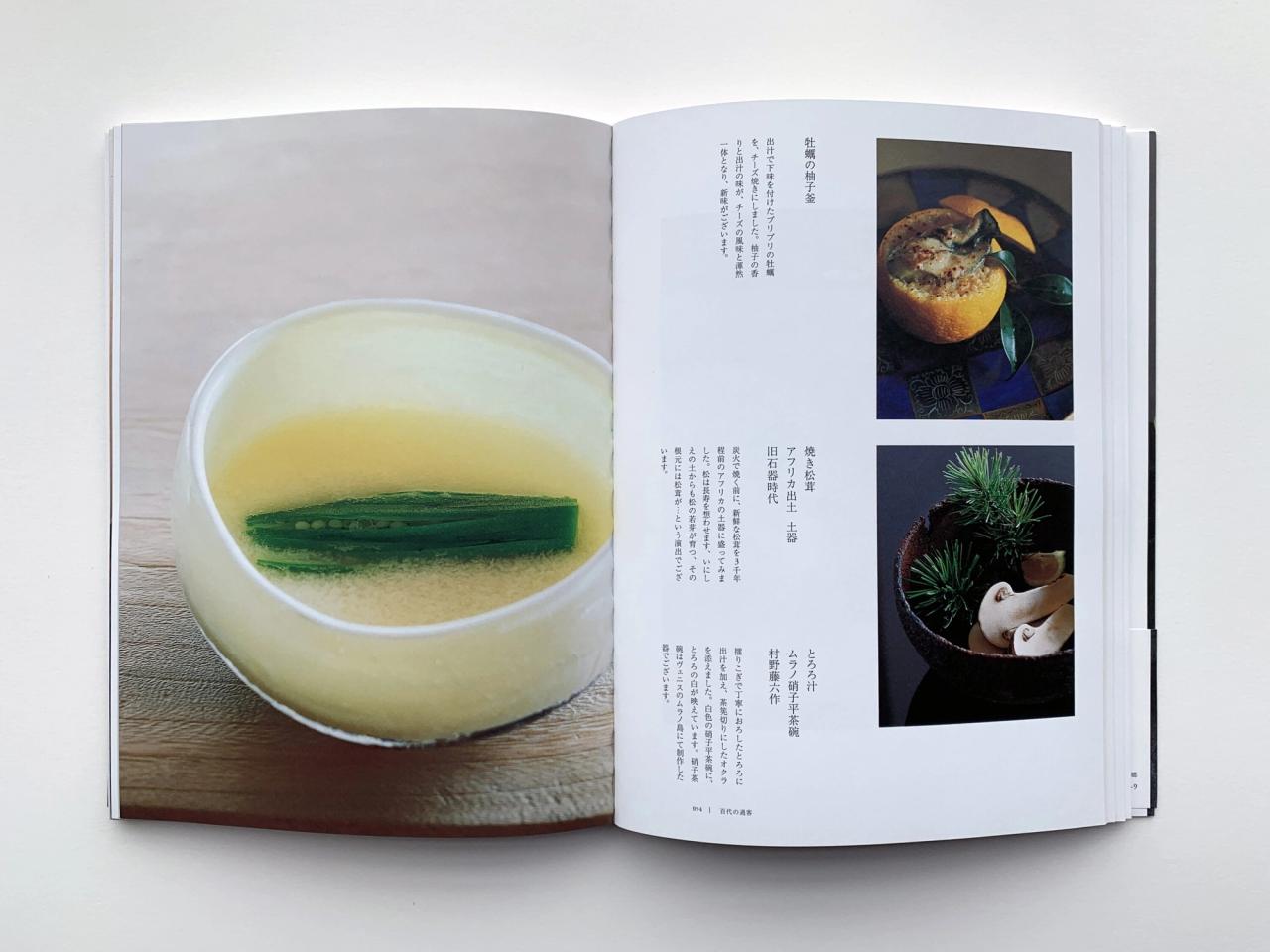

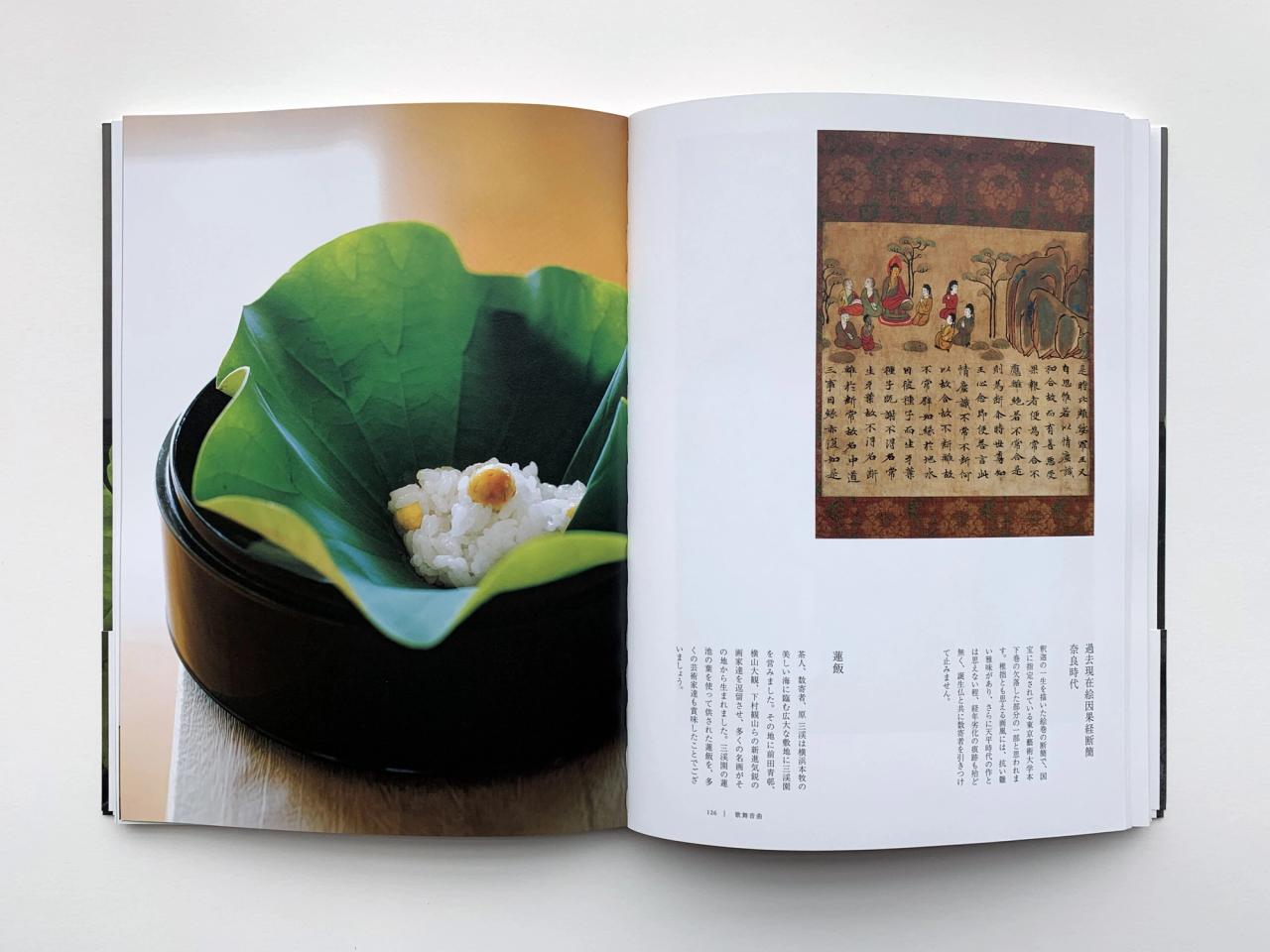

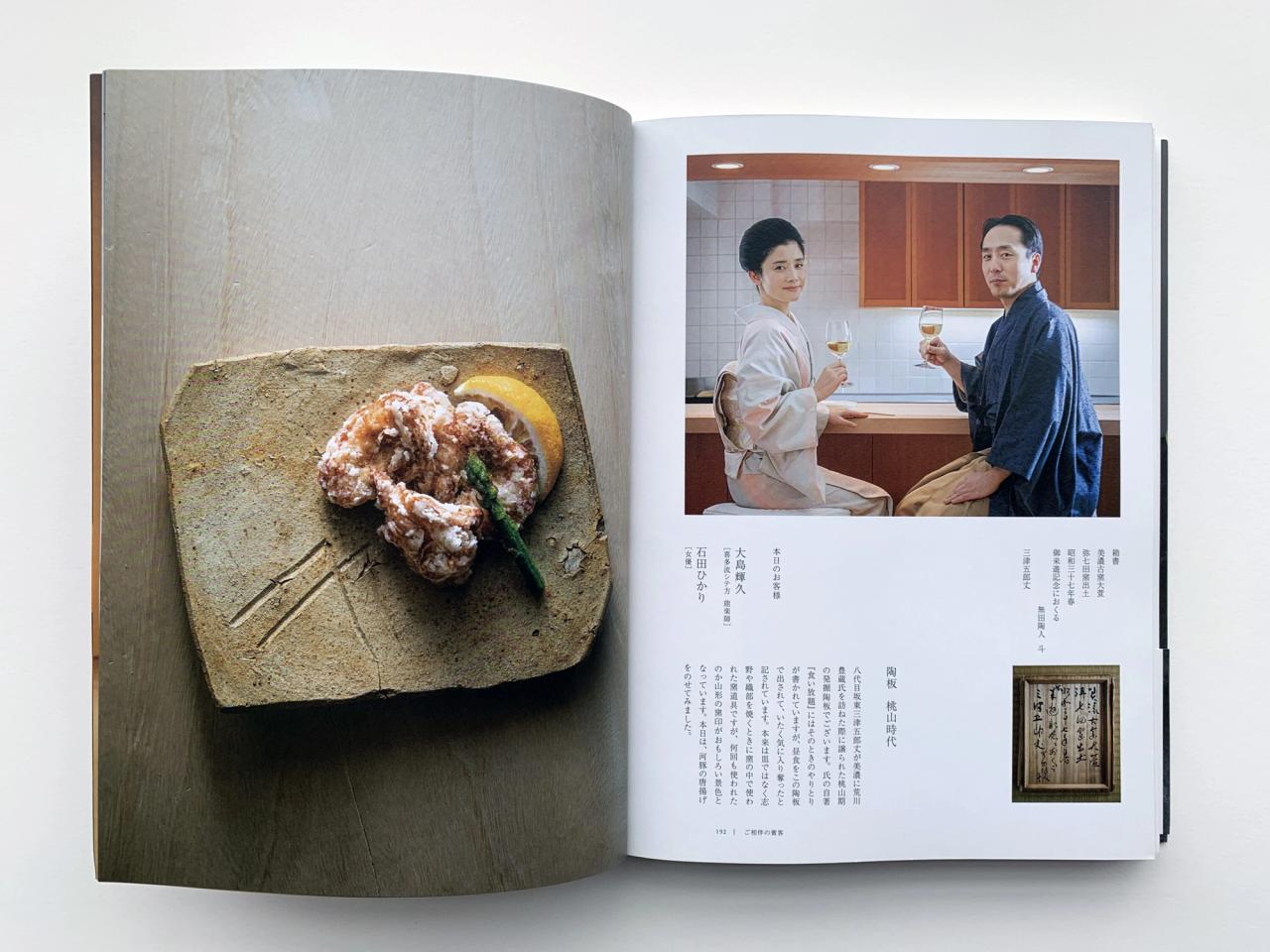

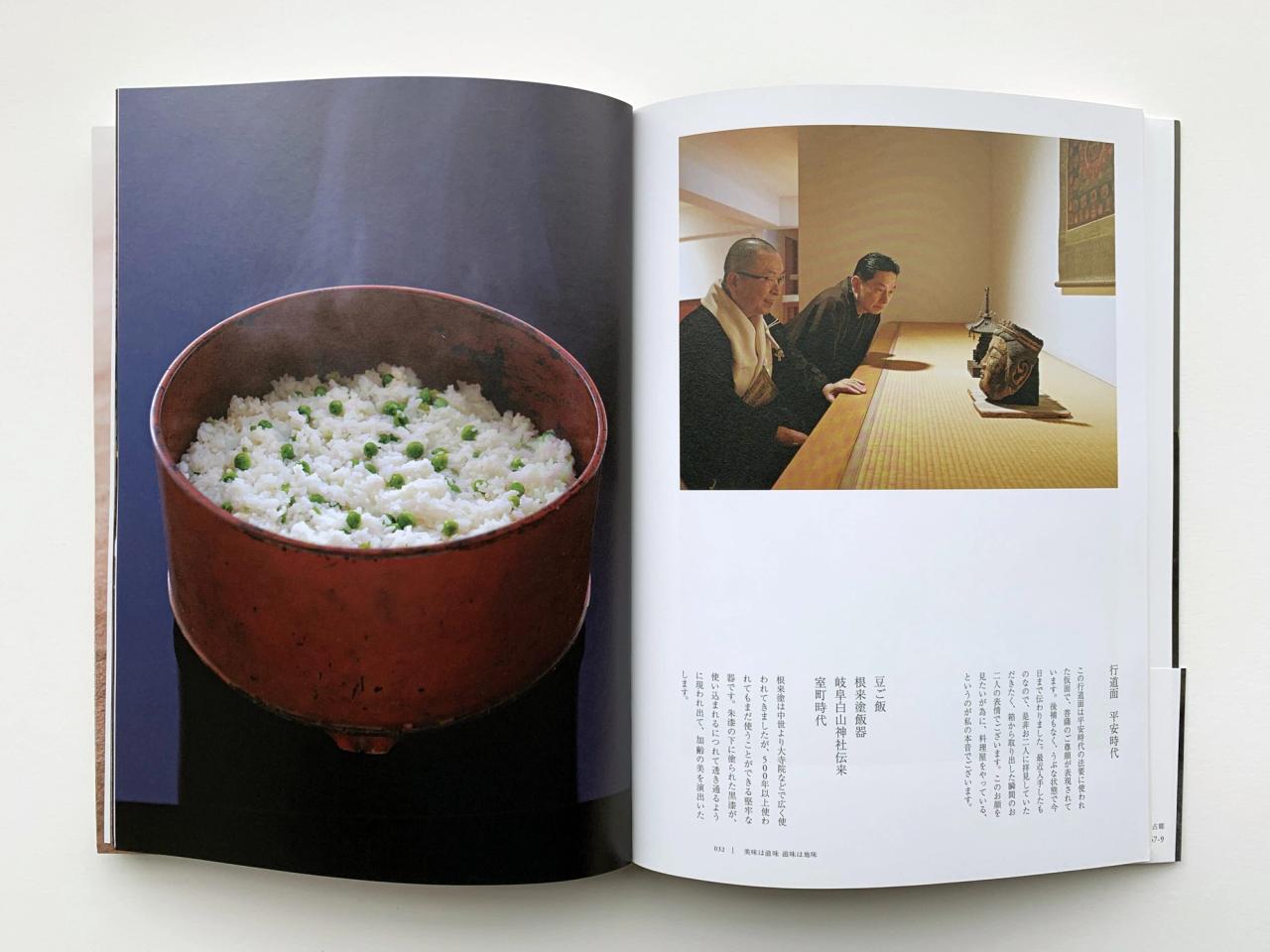

Cover of Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: It’s architecture as—not legacy necessarily—but a gift, a way of continuing your time.

HS: Yes, and a gift to the people. Left to this world.

SB: In the time we have, I have two final subjects I wanted to ask you about. One is cooking.

HS: Oh!

SB: Because I heard that you have a special relationship to cooking and maybe it’s a specific type of food?

HS: Yes. Well, particularly, traditional Japanese. But I even published a cookbook. Japanese women’s magazines are quite high-end culture magazines in Japan. There are no such things outside of Japan. I hide my name, and then supposedly there’s a very small restaurant receiving only four guests and then they serve for the particular guest, reading the mind of the guests and fitting the sense of their aesthetics, and also the fitting their I.Q. level, as well.

So I make a recipe and take a picture of the food sometimes by myself, and then six pages every month. I contributed for three years, and then finally, I showed my face when I published this book. Well, sorry, it’s me. [Laughter] But from the first, the presentation of the restaurant—sorry, we never announced the telephone number, the address. Our reservation is fully booked for a hundred years. [Laughter] So don’t call me. Very highly snobbish restaurant, I imagined.

[Laughter]

SB: So it’s an imaginary, make-believe restaurant.

HS: Yeah, imaginary, make-believe restaurant.

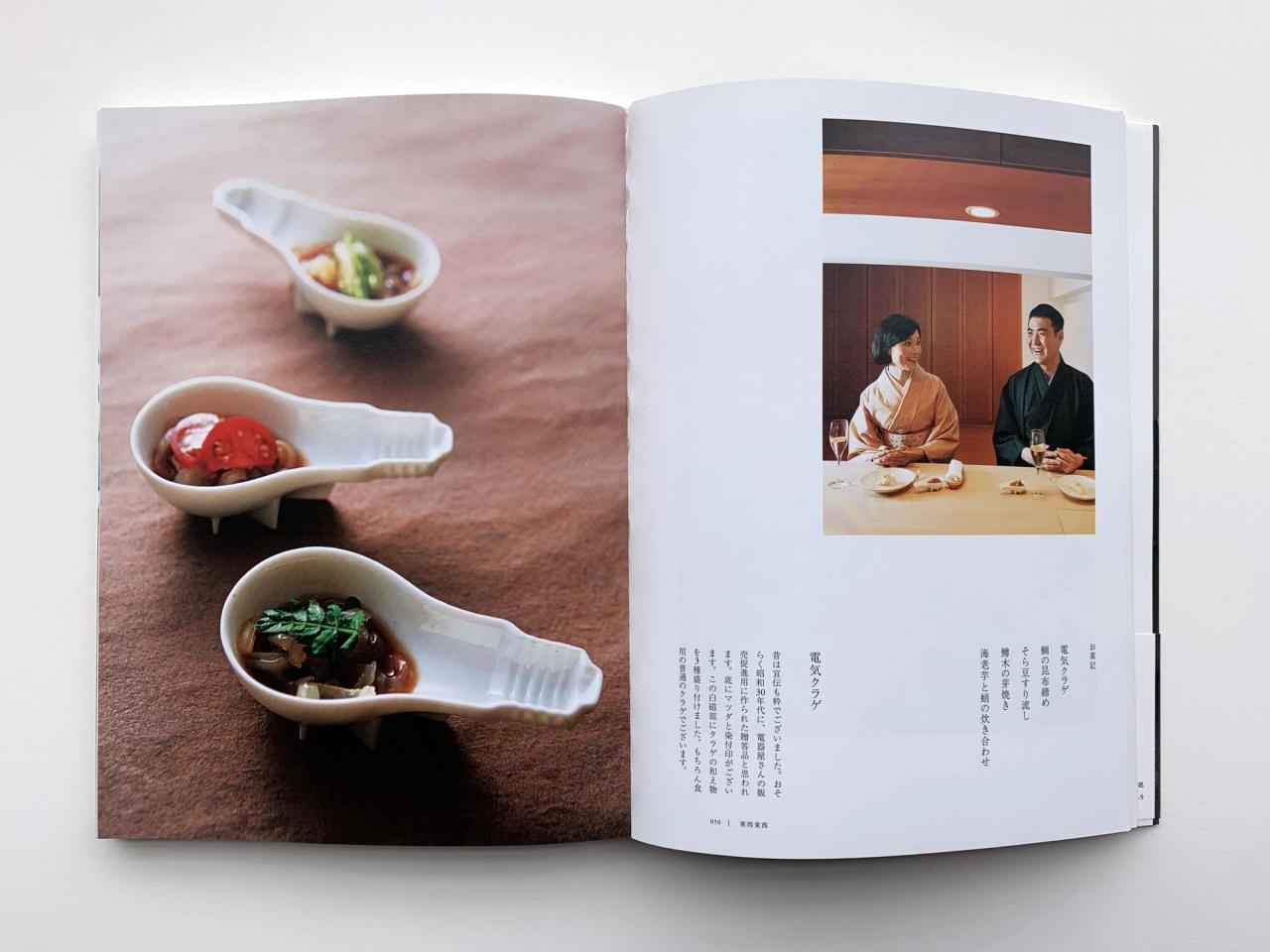

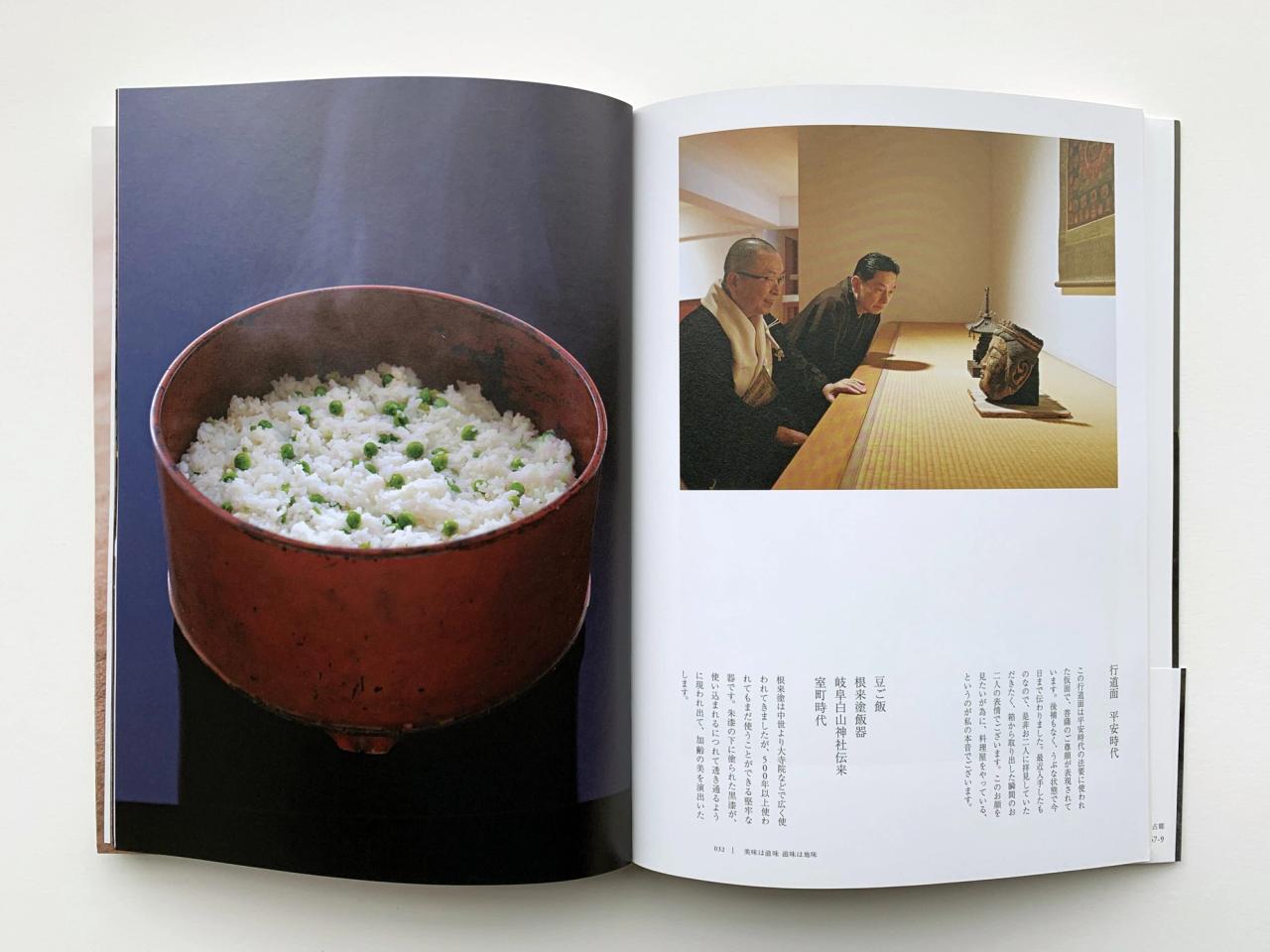

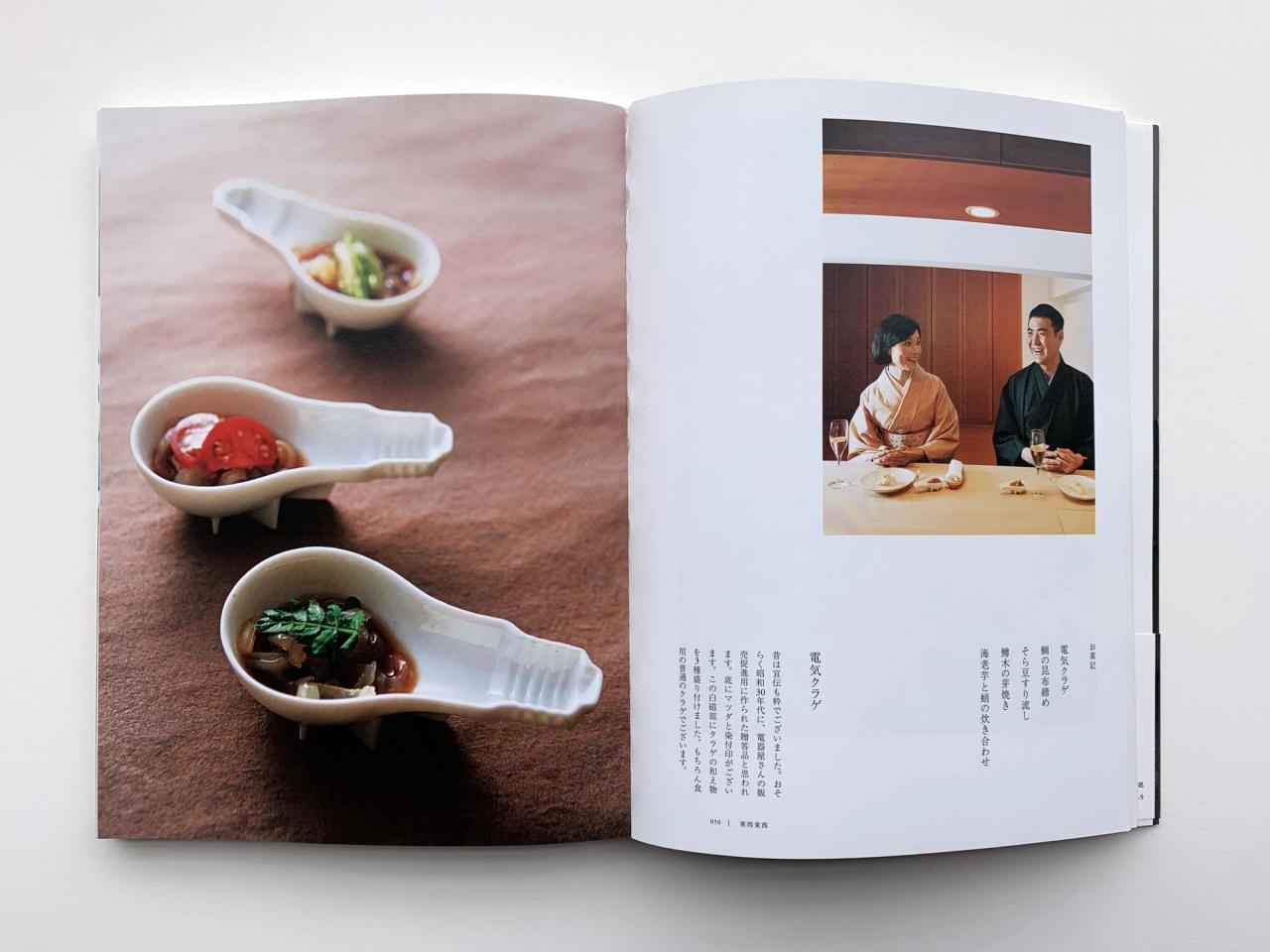

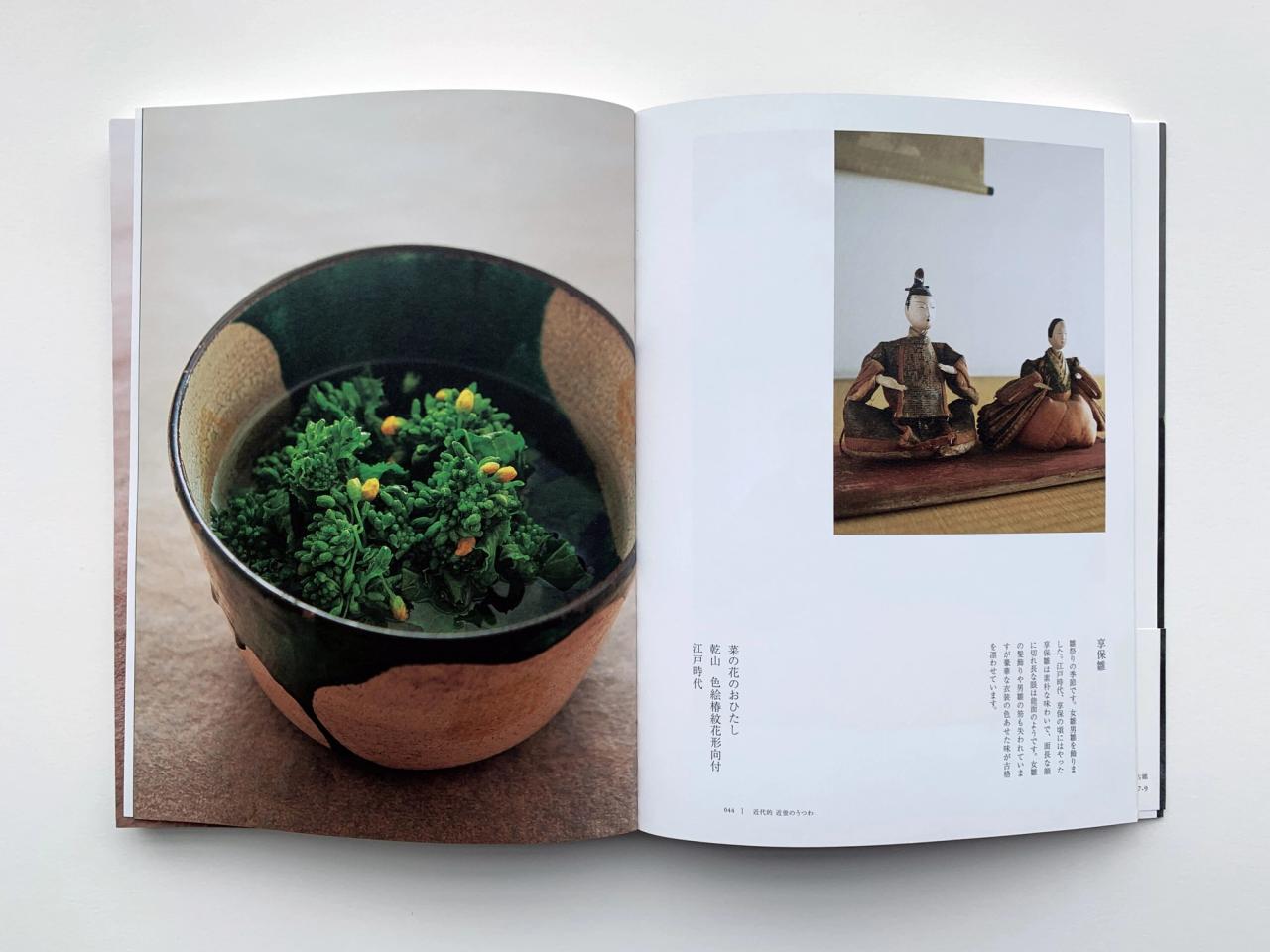

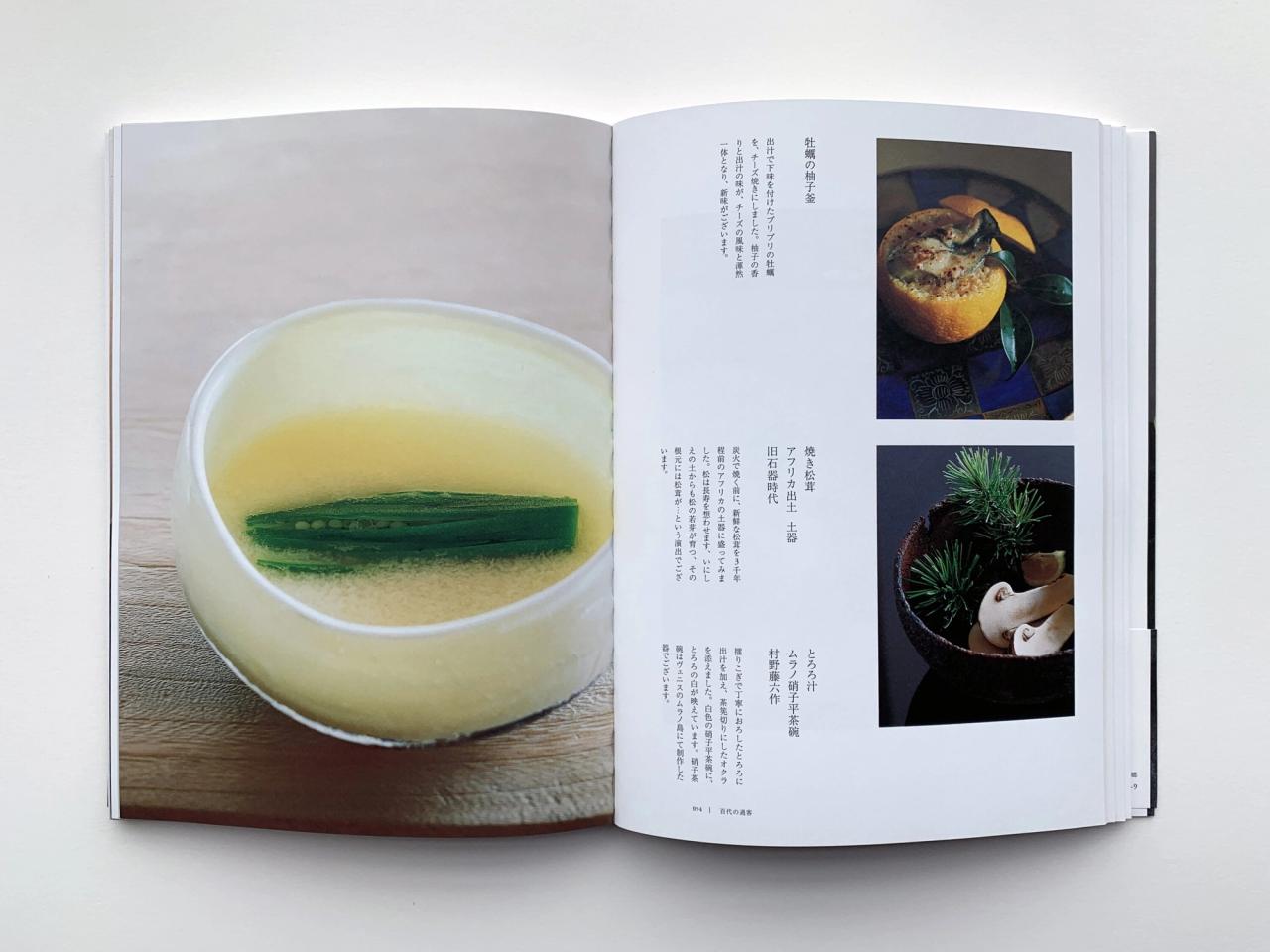

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

Spreads from Sugimoto’s cookbook, Shumi to Geijutsu (2020). (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

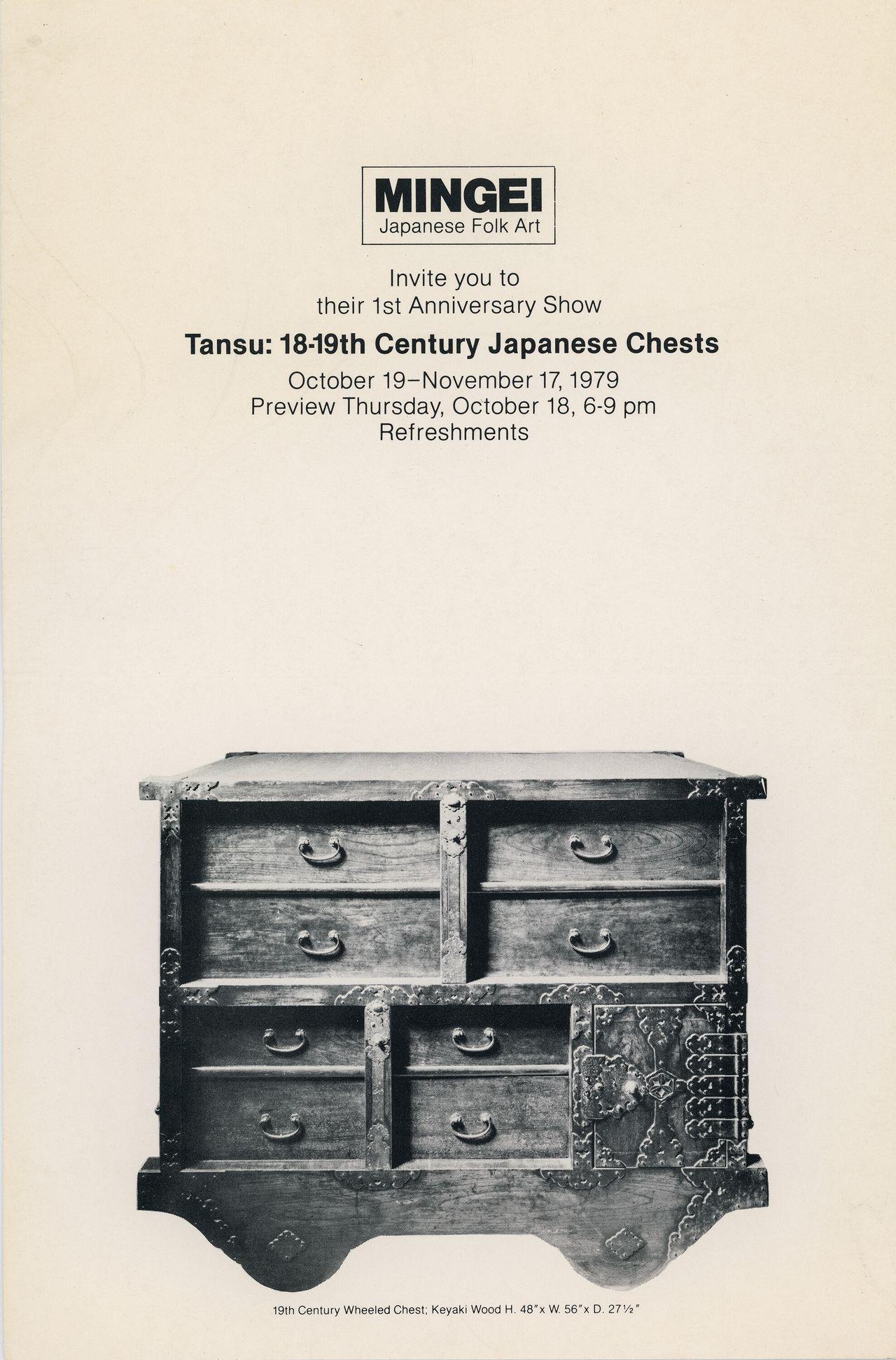

The invitation to an exhibition at Sugimoto’s Mingei store in 1979. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: What has this cooking time provided you?

HS: I never trained as a professional, but I had ten years of activities as an antique dealer from 1980 to ’90. I had a store called Mingei on West Broadway, 398 West Broadway. It was near Spring Street, when SoHo was “happening.” That was just by accident—my wife started, but she couldn’t carry on because of the baby. So I had to take it over, and then all of a sudden, I started going back and forth four times a year, Japan and New York. And then within the five years, the Metropolitan Museum [of Art] became one of my biggest clients.

So without any education of Japanese art history, I just trusted my eye. Just something I found in the countryside of Japan, and was so, so interesting. I bought hundreds of books to study and then just presented it to my client. And then! Isamu Noguchi became the first big client. And then Donald Judd and Dan Flavin, they were such close friends; they always came to visit me. I confess that you changed my mind, but he loves fifteenth-, sixteenth-century negoro lacquerware. I was looking for the lacquerware, particularly for him, particularly for Dan Flavin, who liked ceramics of the seventeenth century.

So I was quite experienced, and then what happened is, if I go to Kyoto for the top dealers—always welcome for the dinner and very secret, nice restaurant here and there. I became a very close friend of one of them, a very small restaurant. I ran all the recipes from him. Judd was involved in an antique dealership, and there’s just so many unexpected things that came to me.

SB: I love that it goes back to Judd. [Laughter] Well, final question.

HS: Yes.

A scene from Sugimoto’s bunraku puppet show, Sugimoto Bunraku Sonezaki Shinju: The Love Suicides at Sonezaki. (Courtesy Hiroshi Sugimoto)

SB: Opera. I wanted to ask you about opera, because I know you sing opera, but also, Japanese Noh theater is a big interest of yours. What is it about opera and how do you think about the time you’ve spent engaging in opera?

HS: Engaging in opera and opera career is, well, the top of the top. I never expected to be doing these kind of theater things, but it just happened. I was asked to do whatever you want because my bunraku puppet show [Sugimoto Bunraku Sonezaki Shinju: The Love Suicides at Sonezaki] went to Paris [in 2013] and then the people saw this opera. It’s a long story, but many people got involved. And then I was asked to do something interesting [at the Opéra national de Paris in 2022]. It’s an opera, but it’s a ballet piece. So I decided to make a Noh theater concept [At the Hawk’s Well]. Noh theater is a kind of ballet, so contemporary dancers together with traditional Noh theater dancing teams.

Then W.B. Yeats had written the story. Yeats was quite heavily influenced by the story of Noh because the Celtic myth is very similar to the Noh story. And, toward the end of his life, he saw the first translated English text, and then, wow, this is his last moment, his life, and he wrote this piece, At the Hawk’s Well. So this story performed in London first in the nineteenth century, but it came back to Japan and was rewritten as a Noh play.This is circulating—this kind of Japanese spiritual ghost story. So I think this is a perfect piece to make it happen. As an anniversary, the three hundred fiftieth year of the opera—not the Garnier, the Opéra [national de Paris] theater by Louis XIV, I think, started it, and I was given this particular celebration moment of the three hundred fiftieth anniversary, the first season opening piece. What a burden! “Why do you give it to me? Give it to the French!” I said. [Laughter]

So I’m really into the theater now. I don’t know which way I go. Started from photography, then architecture, and cooking, and theater….

SB: Antiques.

HS: Antique collections. Well, I don’t know who I am.

[Laughter]

SB: I think we should end there. Thank you, Hiroshi. Thank you.

HS: Thank you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on May 7, 2024. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo based on a photograph from Sugimoto Studio.