Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

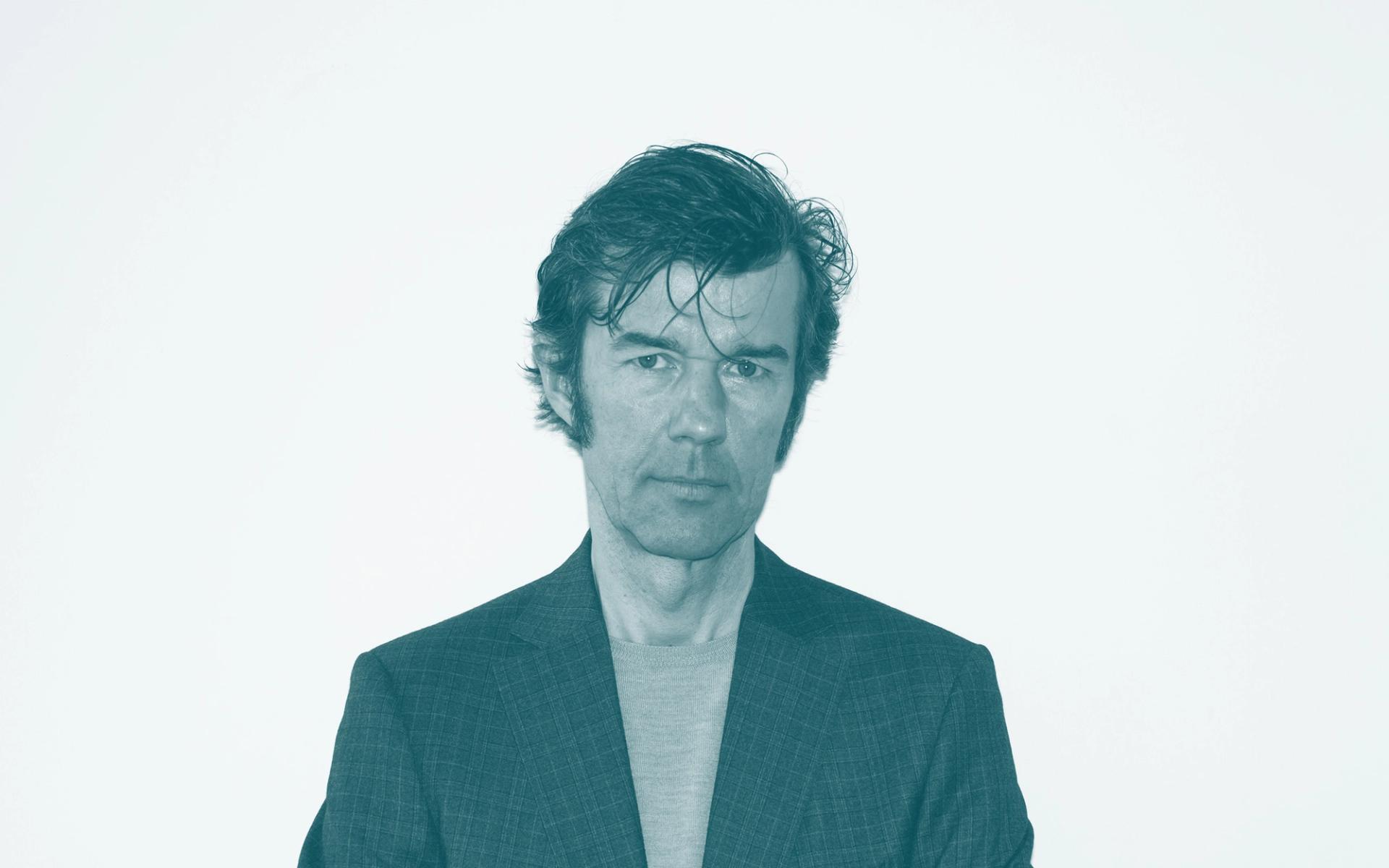

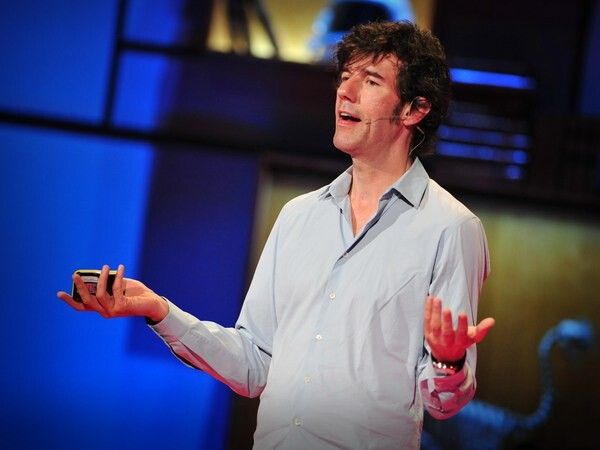

Sagmeister speaking at TED Global in July 2009. (Photo: Courtesy TED)

Spencer Bailey: I wanted to start this conversation around the idea of the sabbatical. Of course, you did a TED Talk on the subject [in 2009], and it’s been watched millions of times, but, I think, in this current moment we’re in right now, the sabbatical is becoming almost more interesting as an idea because of the pace in which the world is going. Going back to your first sabbatical in 2000, what led you to decide you needed to take a pause?

Stefan Sagmeister: If you think back to that time, this really was the height of the first internet boom. Our company at that point was about seven years old. All the companies that were run by friends—all other design companies in that space—were designing websites. You could charge crazy amounts of money for it because nobody had really figured out how much something like this could cost. Everybody was making a lot more money, and things were booming. And I felt that we were repeating ourselves. I had gone to do a workshop with students at Cranbrook, close to Detroit, and these were very mature graduate students who did some serious experimentations. I was quite jealous of that.

My big mentor, Tibor Kalman, had died the previous year, and that really had driven home again how short my time is—all of our times are—here on this earth. There’s a guy called Ed Fella, a designer who I admire, who came in with his “exit sketches.” He had these crazy typographic notebooks filled with ballpoint pen, which were totally nuts and wonderful. The reason he called them exit sketches was because he was quite old by then. So he thought it was the stuff you do before you die. I felt, that’s sort of strange, that you’d do these things at the end of your life. Why wouldn’t you do this in the middle? I made a little job for myself. A job that I showed later on, in the talk that you mentioned, where I figured out roughly that we seem to get educated for the first twenty years of our lives, and then we work for forty, until we’re sixty. And then we have another twenty in retirement. And then we’re gone. And it just seemed to me, why not take five or six years of these working years, and place them, every seven years, in between those forty years of working time? I literally did that randomly because I thought of it in the seventh year of the studio.

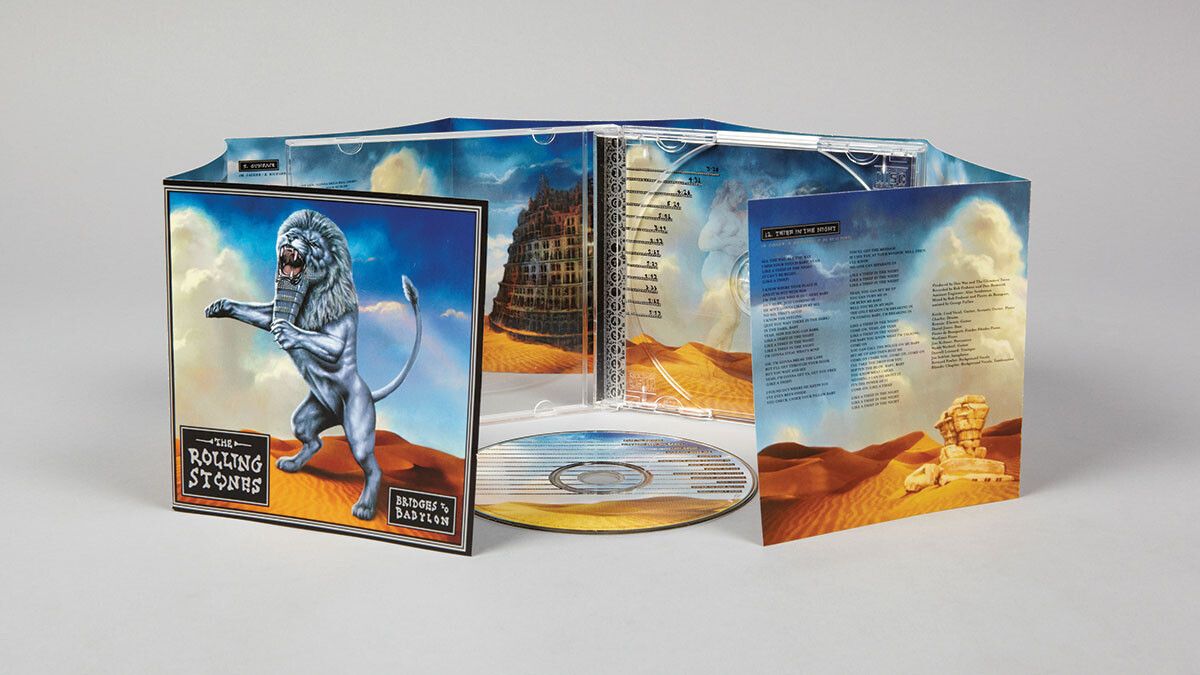

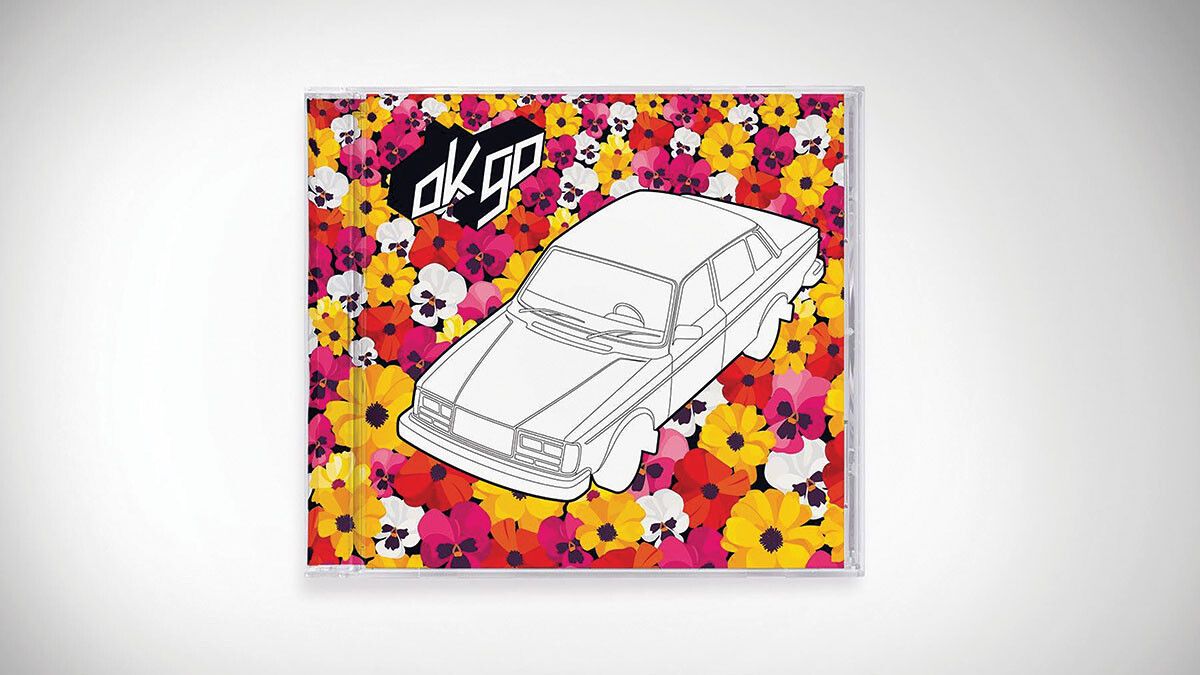

I did know that I had become a designer because I really felt it was a calling. When I was a student, I was engaged in this stuff. I then ran my studio exactly the way I wanted to. We were successful, we got exactly the kind of clients I really wanted to work for—which at that point was the music world; we worked on many [album covers for] bands that I liked. It was an ideal situation, and still, I felt that the routine was coming in, we were repeating ourselves. The latest album cover wasn’t as much fun as the first one was.

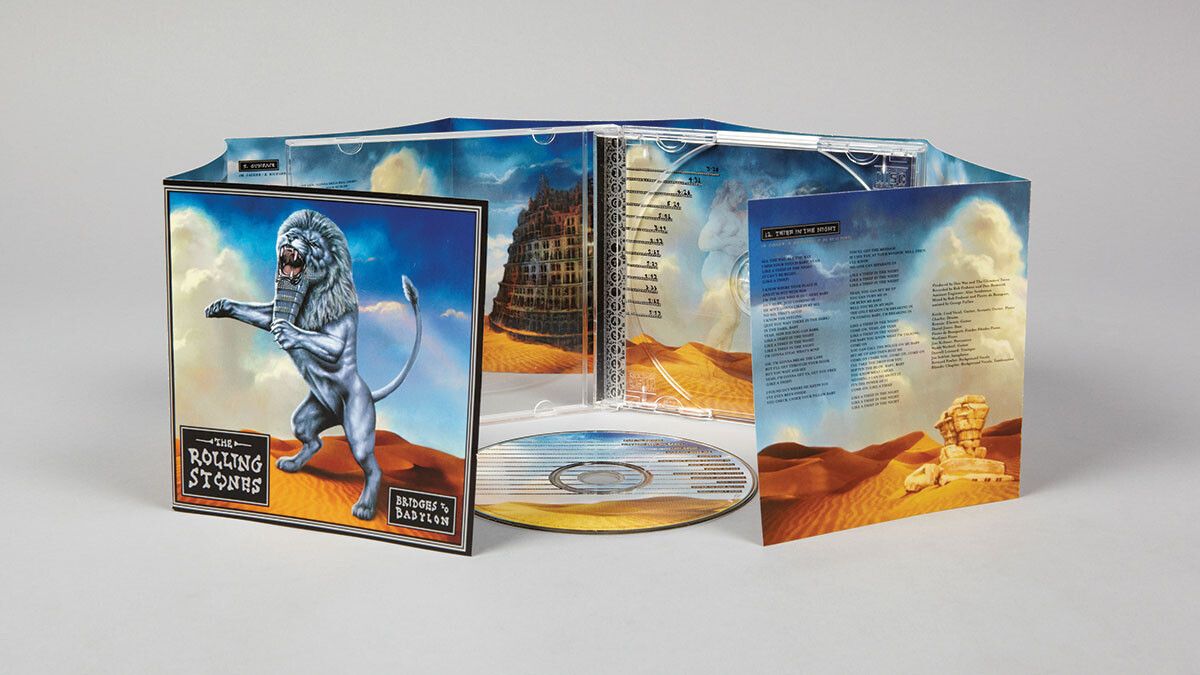

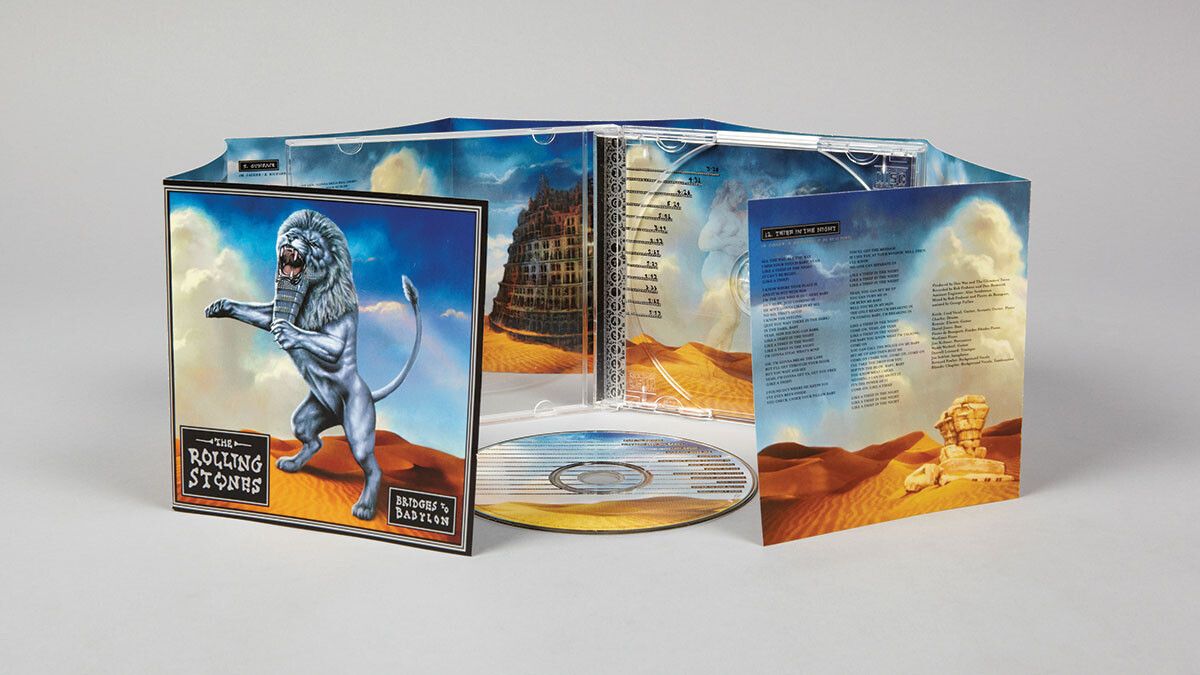

Cover design for The Rolling Stones’ Bridges to Bablyon (1997). (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

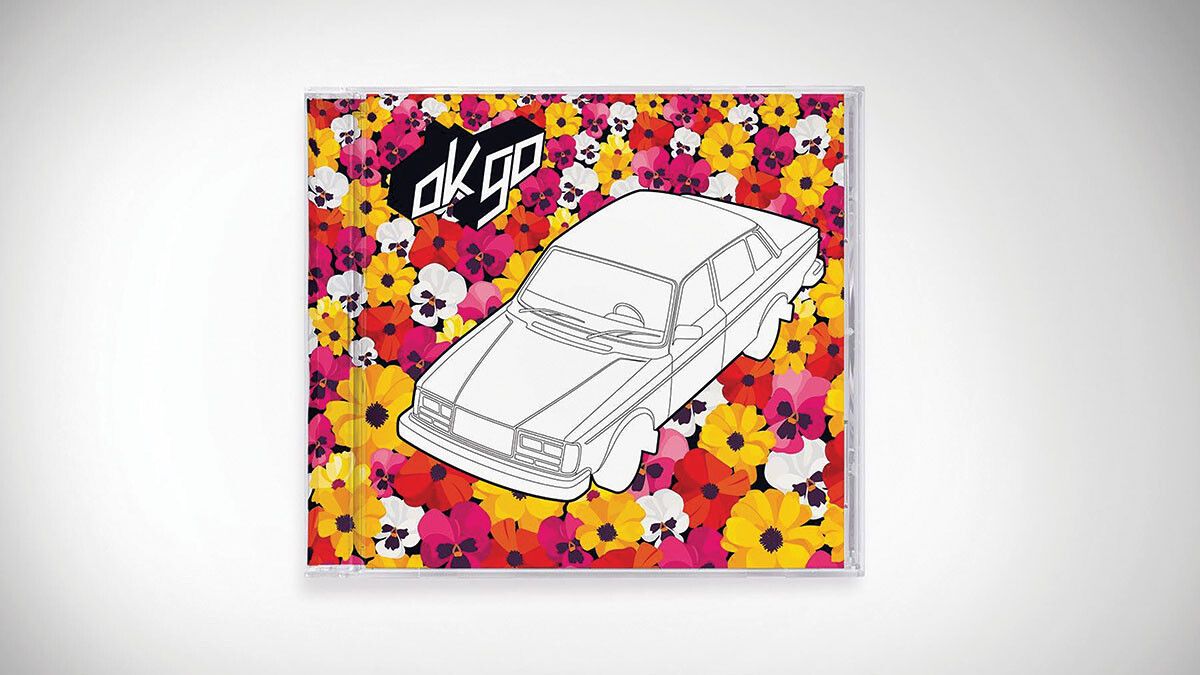

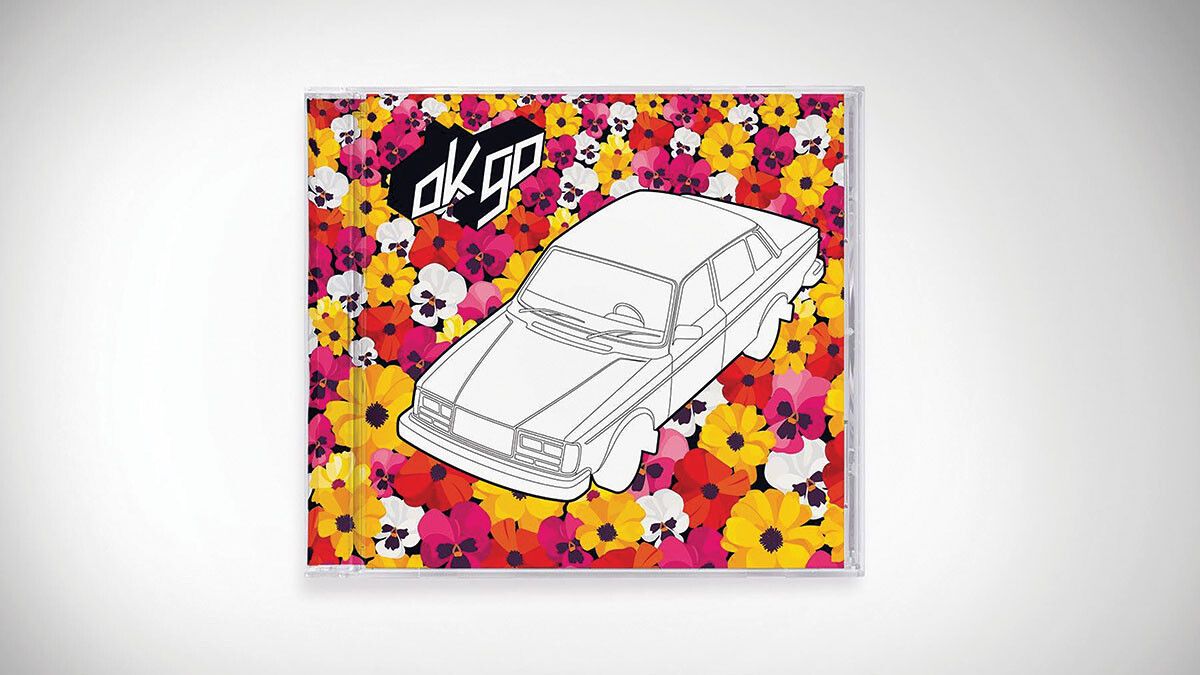

Cover design for for OK Go’s debut album, released in 2002. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

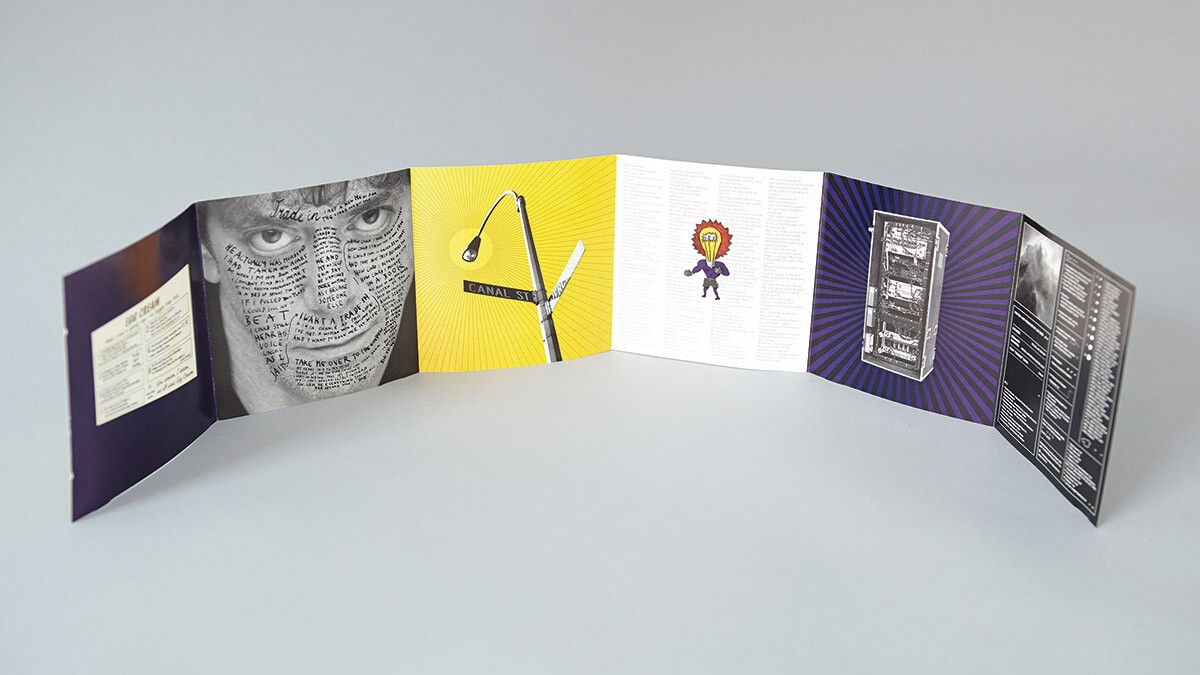

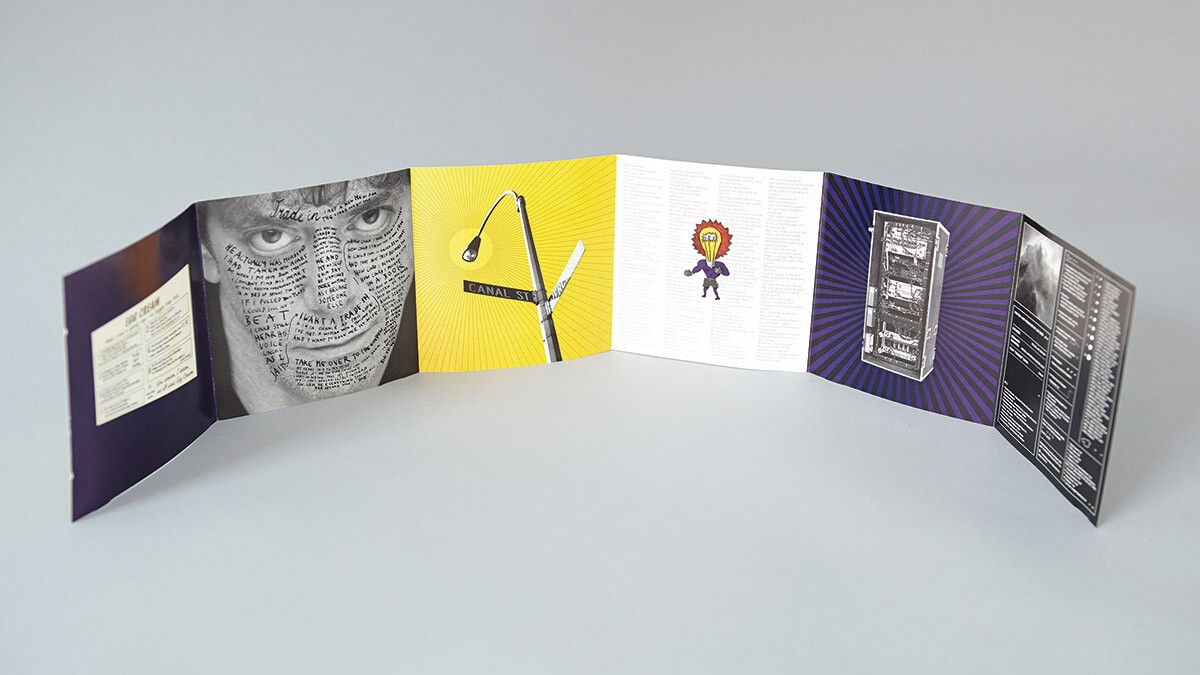

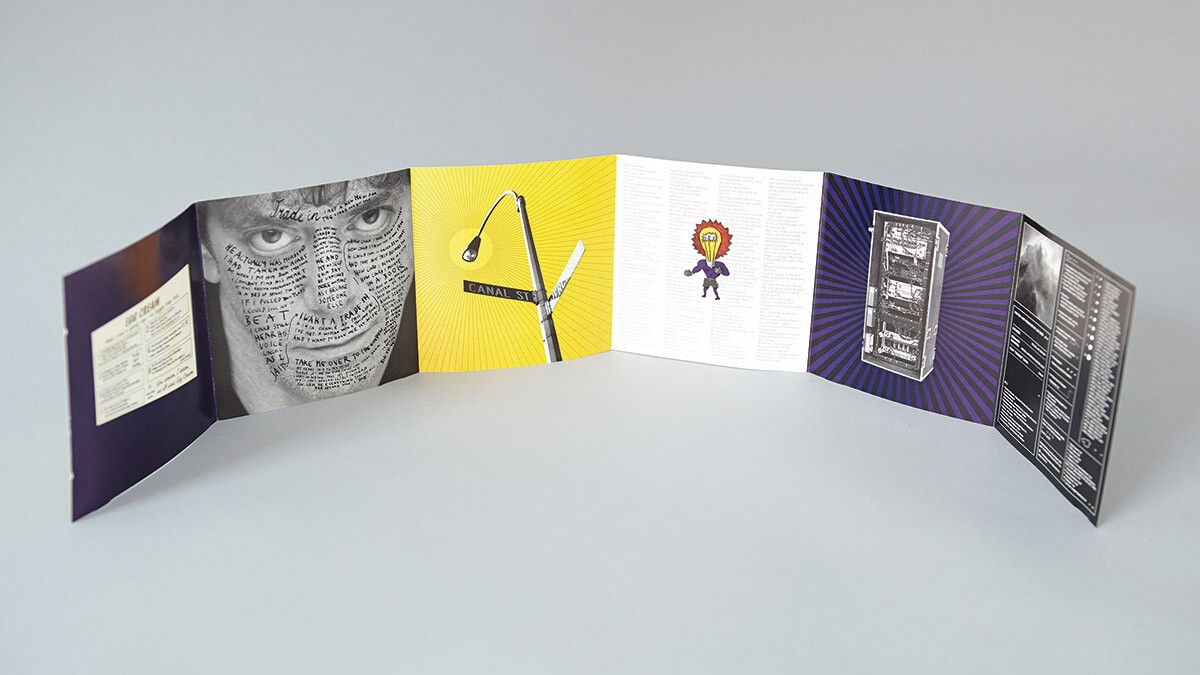

Cover design for Lou Reed’s Set the Twilight Reeling (1996). (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover design for The Rolling Stones’ Bridges to Bablyon (1997). (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover design for for OK Go’s debut album, released in 2002. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover design for Lou Reed’s Set the Twilight Reeling (1996). (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover design for The Rolling Stones’ Bridges to Bablyon (1997). (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover design for for OK Go’s debut album, released in 2002. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover design for Lou Reed’s Set the Twilight Reeling (1996). (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

I thought about [the first sabbatical] for a year, and the reason for that was because I didn’t quite have the guts to actually do it. I had all sorts of fear. One, of course, that we were going to be forgotten; the other that it would look unprofessional, especially toward my family—like, “Oh my god, well, now he’s building this company, and now he’s going away for a year.” Specifically, in that environment, where the economy was good, things were humming, to not work, to not take advantage of such an environment, felt a bit unprofessional. I thought clients might be angry at me. None of these things turned out to happen. When I finally did have the guts—and it did [require] overcoming my own barrier or fear—when I then did tell everybody, nobody was pissed, nobody was angry, nobody felt it was unprofessional. The normal reaction was one of slight jealousy: “I would like to do that, too.”

SB: It’s worth mentioning that you stayed put in New York. You were here for this first sabbatical.

SS: Exactly. It took a while to get the hang of it because I had planned purposefully to not have a plan. I’m a big planner, so I thought, I’ll do the opposite, I won’t have a plan. It didn’t work out at all. When I didn’t have a plan, other people planned my time. So I was basically reactionary to demands of the outside: files that needed to be sent to Japanese design magazines, or going to the post office about this, or getting that stuff. I felt I had become my own intern, and nothing of consequence was created. After I realized this some weeks into it, I then created a very tight plan. That seemed to work much better. I’ve been conducting a sabbatical every seven years since, and I’ve started each with a very tight plan.

SB: So you’re taking chunks of time [during your sabbaticals] and determining, Okay, I’m going to use this time for X and this time for Y.

SS: Yes, literally, there’s a daily, hourly plan, very much like in kindergarten.

SB: Or the military. [Laughs]

SS: Or whatever, yes. [Laughs]

Sagmeister in Bali during his second sabbatical, in 2008.

SB: Tell me a little more about this relationship to time, to scheduling in your life. What did you do when you got into this sabbatical, or the one in 2008, when you went to Bali? How did you take your work-life schedule and morph that into your sabbatical schedule?

SS: Let’s say, from a client perspective, every year was different. The first one, the studio was closed, and there was an answering machine that said “Call us in a year.” The second one, a designer stayed behind and answered the phone, and finished up a couple of long-term jobs. The third one, by that time, I had partnered with Jessica Walsh, and she had decided that [a sabbatical] really was too early for her, considering she was considerably younger than me. That meant she was leading the studio while I was away.

From my own time-in-a-sabbatical perspective, let’s say in Bali, throughout the seven working years, in between the first and the second, I kept a list of things where I thought this would be great to think about or great to pursue, but it’s too time-consuming to do right now, during the regular studio hours. Literally, I think on the way to Indonesia, on the plane, I looked at that list again and probably threw at least a third [of it] out, because it just wasn’t interesting anymore. Or I might have done parts of it, or lost interest. I kept the stuff that still seemed juicy, and depending on the kind of idea or the kind of subject it was, or depending on how much time I thought would be necessary to become fruitful, I assigned weekly hours to it. This one, an hour a week is fine; this one, five hours would be fine. There were bigger subjects: let’s say, explore the craft of Bali and do something with it. This could have included doing some research on it, driving around, visiting villages that do wood-carving or stone-masoning or silversmithing, and then see what kind of projects might be interesting, or literally designing things along those lines and commissioning them. This became quite big in the beginning, because while I was gone, the studio was renovated in New York and needed furniture. Rather than buying midcentury chairs, I just thought, I’ll have that budget of what a midcentury chair would cost, and I’ll use that as a prototype budget to design myself. I thought, Well, designing that kind of furniture might be a hoot. I’d never done it before, designing in that size, and in three dimensions, and getting it made in Bali, where you can get these things made. I thought it might be fun to do. And I did it.

SB: When you were in Bali, one of the big things to come out of that time there was “The Happy Show” exhibition and The Happy Film. How did you go about figuring out that happiness, I suppose, was something you were going to explore? Did you know that going into the sabbatical, or was that something that the time you had there led you to?

Elevator illustration from “The Happy Show” at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia in 2012. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

A gum-ball machine installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

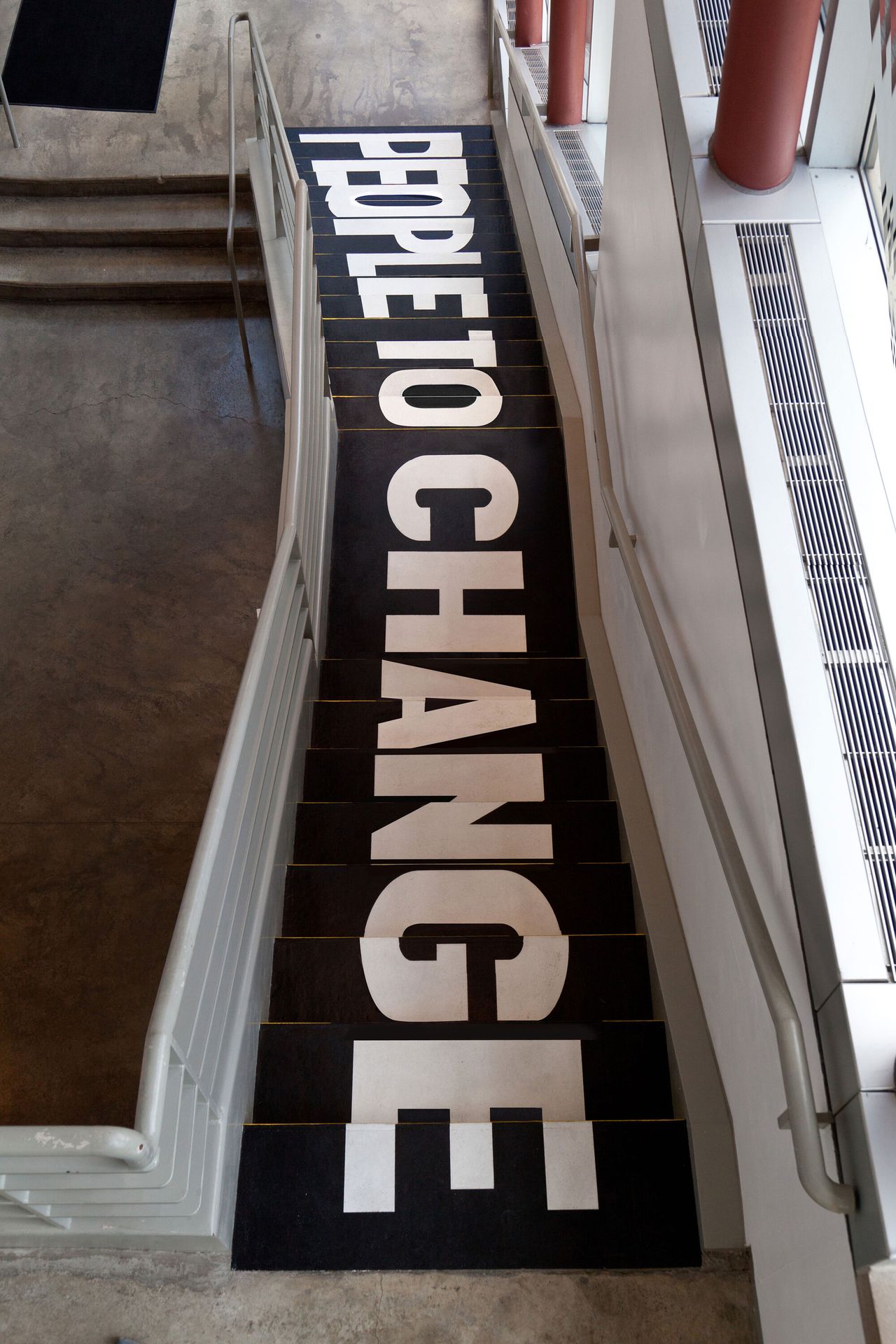

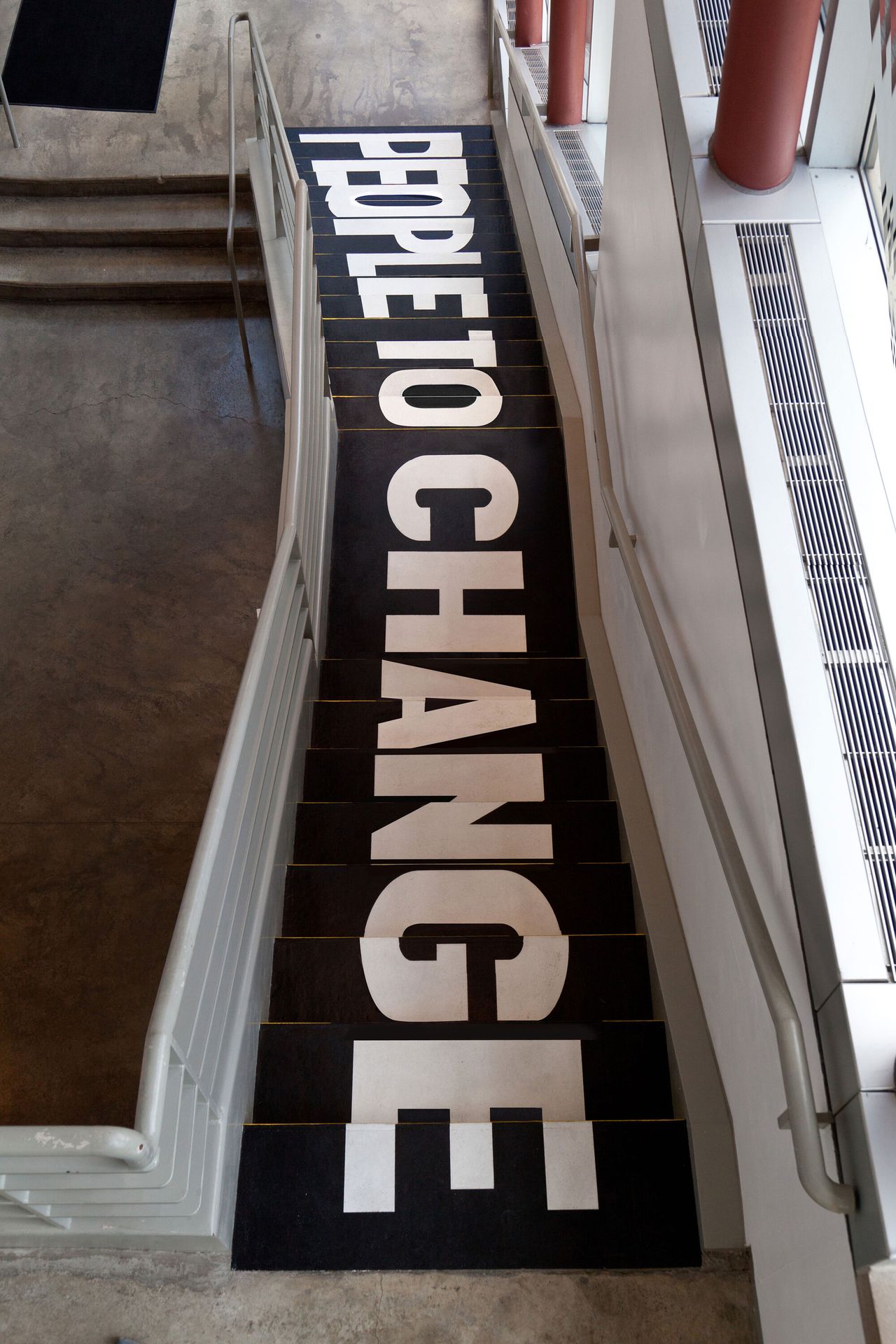

A staircase at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another staircase at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Elevator illustration from “The Happy Show” at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia in 2012. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

A gum-ball machine installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

A staircase at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another staircase at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Elevator illustration from “The Happy Show” at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia in 2012. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

A gum-ball machine installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

A staircase at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another staircase at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another installation at “The Happy Show.” (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

SS: No, I didn’t know that at all. Actually, that came about because my friend George [Azar], from New York, came to visit me in Bali. He saw, at that point—that was roughly after three months or so—we had a lot of prototypes standing around of furniture and benches and lights and things that were about to be built and made. The studio had a lot of one-to-one prototypes of furniture-y things. George thought this was a total waste of my time, that I went through this process of making this sabbatical happen, and now I’m building furniture for myself, and this was stupid. He thought that I had some sort of responsibility to do something that other people would have more benefit from—and he’s a convincing guy. I thought he had a point. While he was still there, I interrupted our little prototype-building and put some time away to really think about what else could this be. It was still early in the year. And really quickly, in a day or two, I thought to do a documentary film.

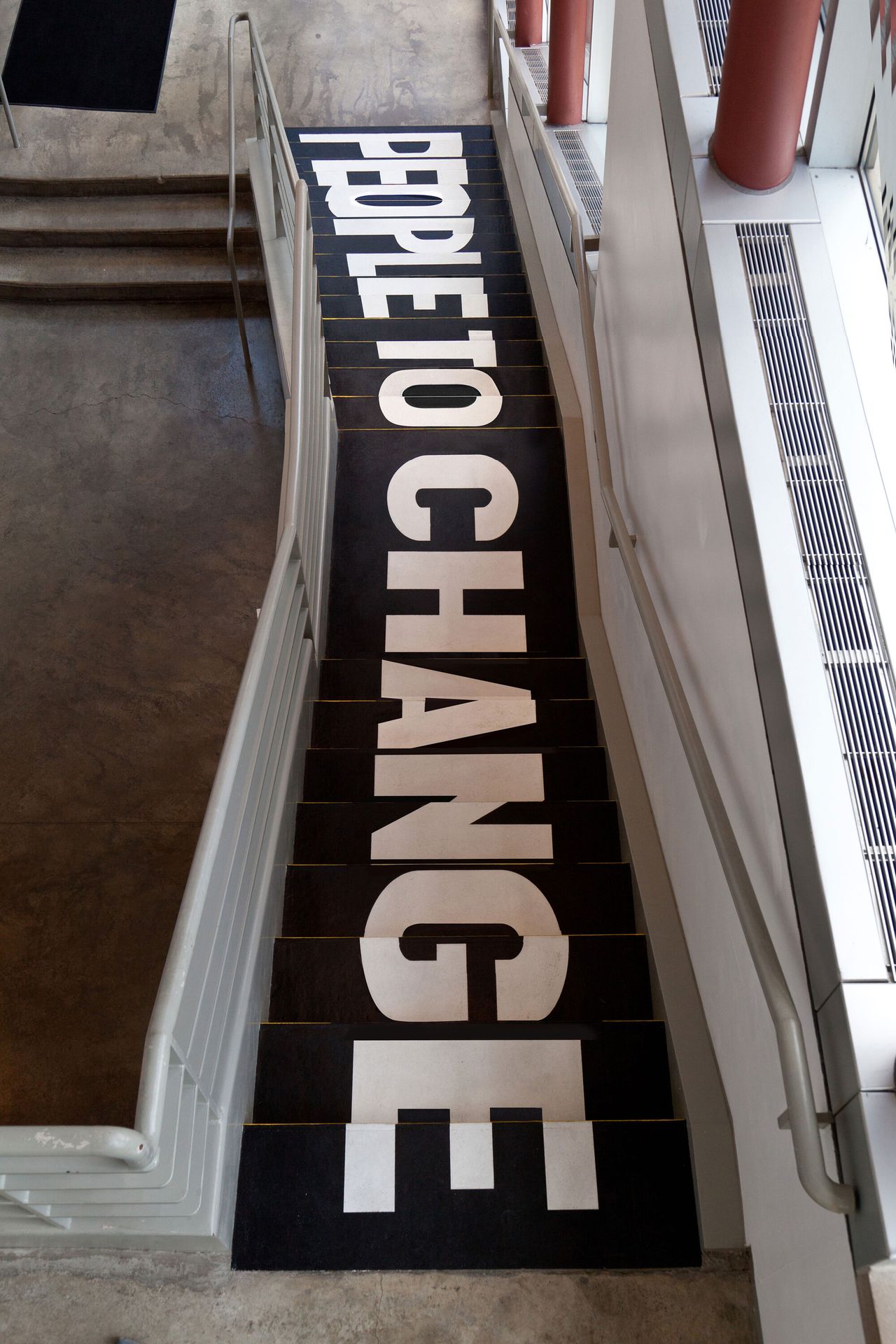

Cover art for The Happy Film, released in 2017.

[The Happy Film] was really the first idea. As soon as I thought about it, I had—which I don’t have very often—this little warm, nice feeling in my belly. It just felt like the right thing to do. The reason why it felt that way was I never had done a documentary film before. It felt like a big challenge. I had done talks on design and happiness, where the feedback was always great from the audiences, and I had a desire to do more research. But I knew if I didn’t do a big project about it, I’m probably not going to do it, I might read a book or two in the evening on my bedside table, but I’m not going to start meeting the scientists and go about this in a more planned and serious way. And I know if I make a big project out of it—a design project about it—that would be the ticket. So I felt that the worst that could happen is I’ll wind up with a film, and the best that could happen is maybe I’ll even find myself happier by doing the research.

SB: What was so fascinating about it was—in retrospect, and, at least, to me—is that you finished the sabbatical and basically spent the next five to seven years making the film.

SS: One of the down sides of doing this, of basically starting something that I didn’t really know how to go about—which was documentary filmmaking—was that [we mostly cut] the stuff that we did in Bali already, with very few exceptions. I think that the only thing that made it into the film, of the many things we shot in Bali, was the title sequence. And maybe a couple of seconds of other things. We really did not know what we were doing, and we went about it in such a stupid way. It took a long time afterward to actually make that film, but I would have never, ever, have had the idea to do it, and to create it, if it weren’t for the sabbatical, no doubt about it.

SB: Describe your most recent, and the third, sabbatical. Where did you go? And what came came out of that? Is this where the beauty project began?

SS: Yes, and this time, it was a more planned thing. With the third sabbatical, the idea was, let’s not repeat the same thing. The easiest idea would have been to go back to Bali. The house was still available that I had rented seven years earlier. By now, of course, I have many friends that I made in that year there, so the easiest thing would have been to go there. But I didn’t want to do the same thing. I didn’t want to basically repeat that thing, and maybe then Bali would have become a routine. I felt, let’s not just take another exotic location and do that. Let’s do three different places. Also, I felt a little bit like, after the Balinese year, things had become a little samey, so I thought, let’s try three [places].

Three locations that I felt were interesting right now—this was two years ago—were Mexico City, simply because it’s very much alive and things are happening there now; Tokyo, because I felt like Japan, particularly Tokyo, was throughout the second half of the twentieth century almost alone in first world countries still taking aesthetics and beauty seriously and not replacing it with function, like many other countries, definitely Europe and the States, had done; and then, for the third one, considering the first two choices were [among] the biggest cities in the world, I wanted to have the opposite of that, which turned out to be a tiny village in the Austrian Alps, Schwarzenberg, which I knew only a little bit about.

SB: But nothing was premeditated. You had chosen these locations basically on interests, not with any specific project or …

“We as people become awful, ugly, stupid, and aggressive if we are in environments that are not beautiful. We see this all the time. And now that we’ve done a lot of research on it, we can prove it. I mean, if you’re in an environment that is lacking beauty, you are becoming an asshole.”

SS: Well, I actually—not a year before, but months before—was pretty clear that I’m going to work on beauty. I had done a talk already on beauty and the importance of it. In design but also in architecture, and for sure in product design, there is a widely spread idea among practitioners that beauty is either commercial, or surface-related, or old-fashioned, or not something that a thinking person should really spend a lot of time worrying about. We ourselves in the studio had found that, for purely functional reasons, whenever we take form seriously, it works much better. So from a pure functionality point of view, this seemed to be wrong. And then, of course, there’s a completely just as valued humanitarian point of view, where we have much evidence that we as people become awful, ugly, stupid, and aggressive if we are in environments that are not beautiful. We see this all the time. And now that we’ve done a lot of research on it, we can prove it. I mean, if you’re in an environment that is lacking beauty, you are becoming an asshole.

SB: [Laughs] I completely agree.

SS: These are serious things. These are not surface-related, commercial crap.

SB: We laugh at it, but it’s serious.

SS: I had a feeling that [beauty] would be worthwhile, of not only contemplation but also of some proper research. And by research I mean this can be as easy as reading dozens of books on the subject, which if you read dozens of books, of contemporary books on aesthetics, you cover pretty much all [of it]. Because, strangely, as I discovered, [beauty] had also fallen out of the trend in other fields. Psychologists complained that there was really little research being made, because it was not in the time. In philosophy, all the way until the nineteenth century, this was a serious subject; in the twentieth century, not so much. So you could get a pretty good idea just by reading dozens of books.

I met many people in the field. One of my favorite scientists in that world, a psychologist who runs a very big lab on aesthetics in Vienna—his name is Dr. Helmut Leder—agreed to become our scientific expert, or collaborator, somebody to look over the things that we claim.

SB: What Jonathan Haidt was to your happiness project.

SS: Exactly. And that turned out very well. We opened up a fairly big “Beauty” exhibition last fall in Vienna. It’s 30,000 square feet, and it’s hilariously successful. It’s on it’s way to becoming the most-visited exhibition in the history of [MAK Vienna]—and that goes back to the nineteenth century.

SB: Beauty matters.

SS: Yes.

SB: Where is the exhibition going after?

SS: Frankfurt [at the Museum Angewandte Kunst]. Opening on May 10. And then it’s on its way—we have about five museums already where it will come through, and then, eventually, I think it will come to North America. We have one museum in Toronto that really wants it. And then we’ll see. It’s so far out. Because of the size of the show, museums tend to want it for a long time. So it runs for five months [at each institution]. We can only do two shows a year.

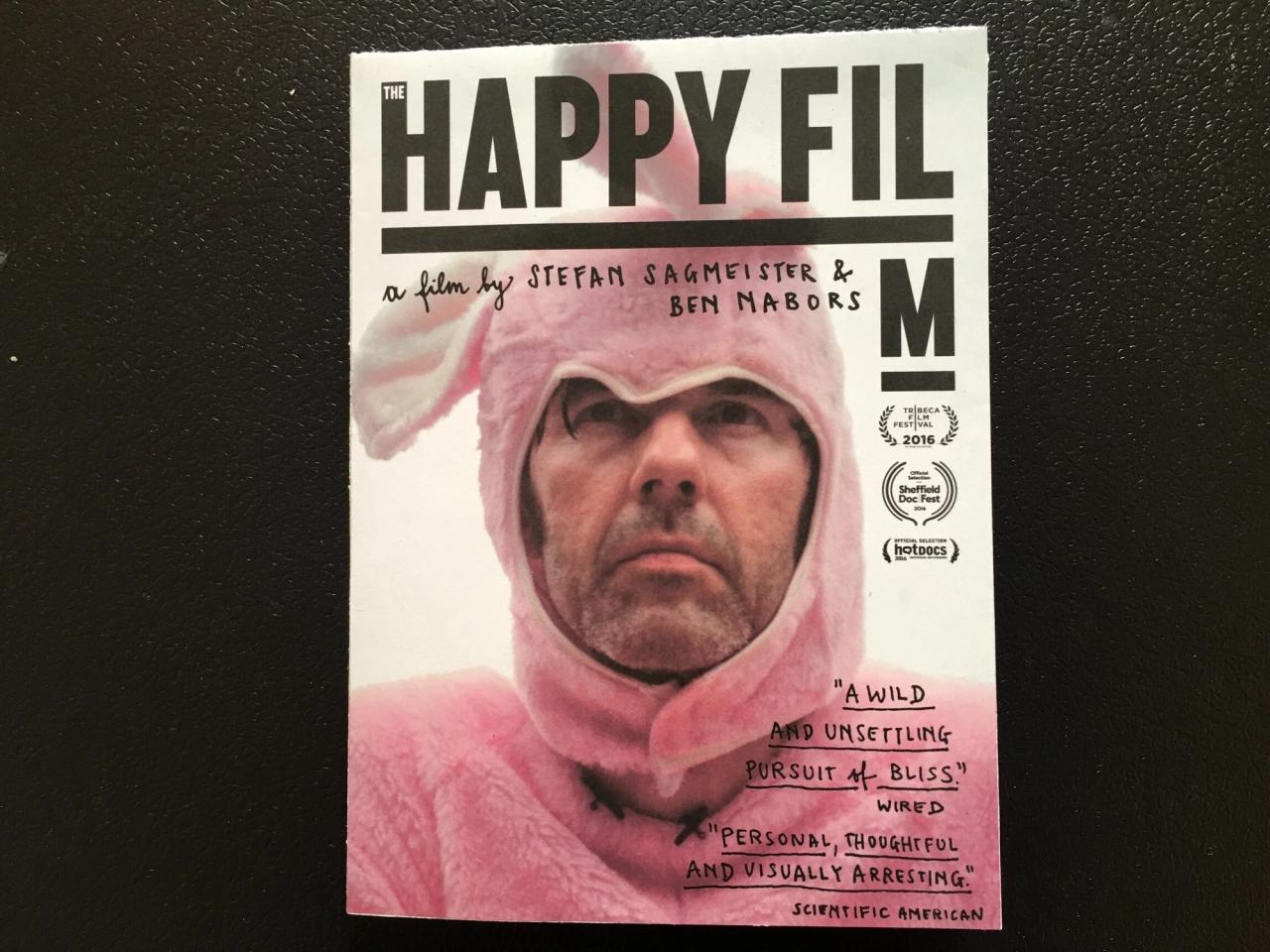

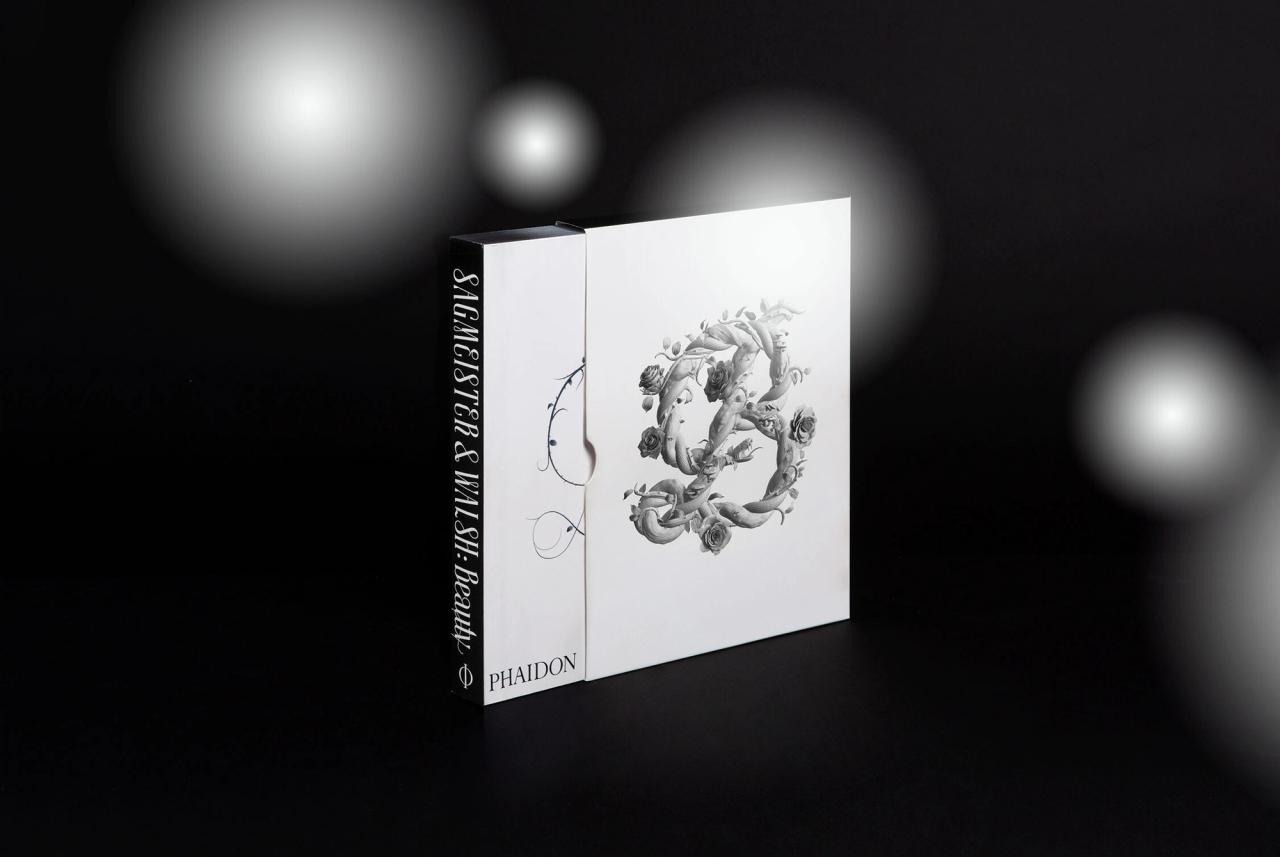

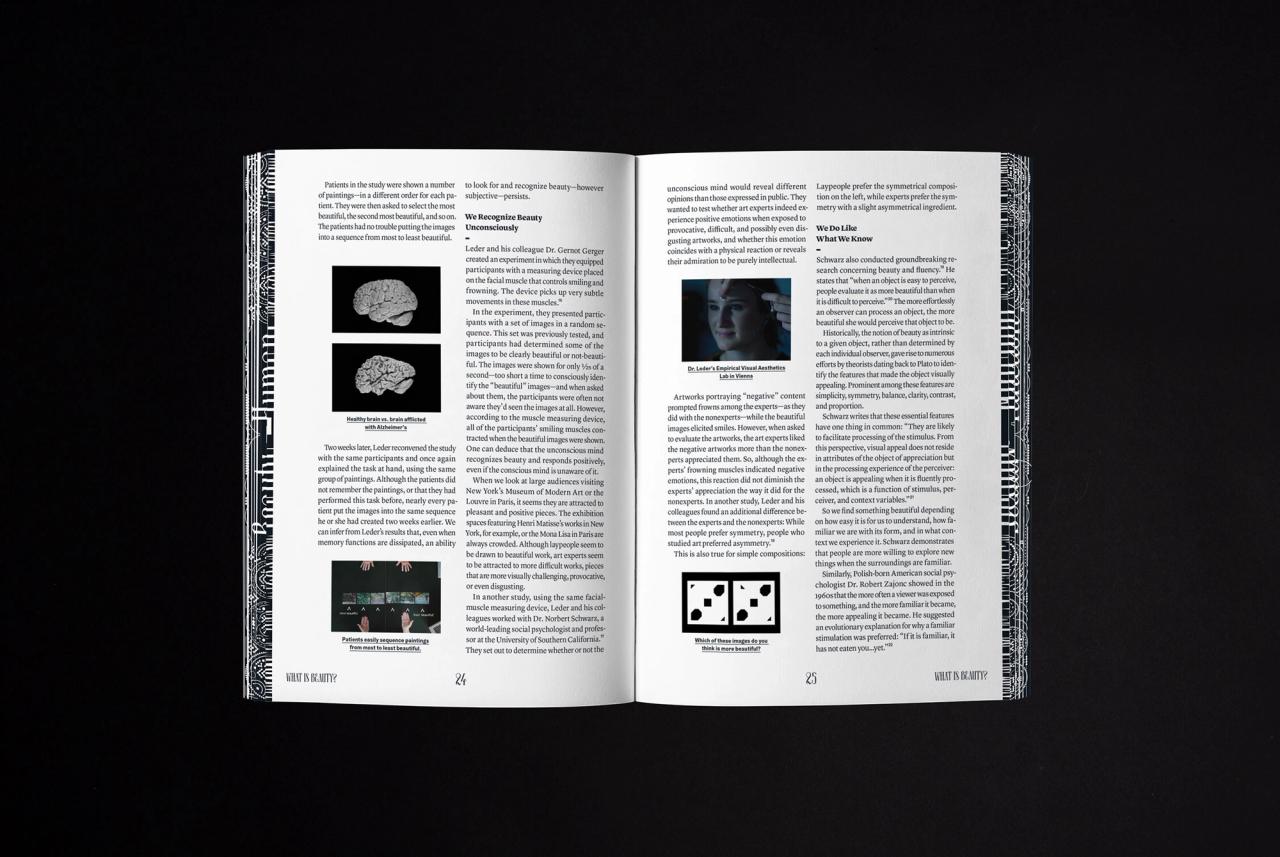

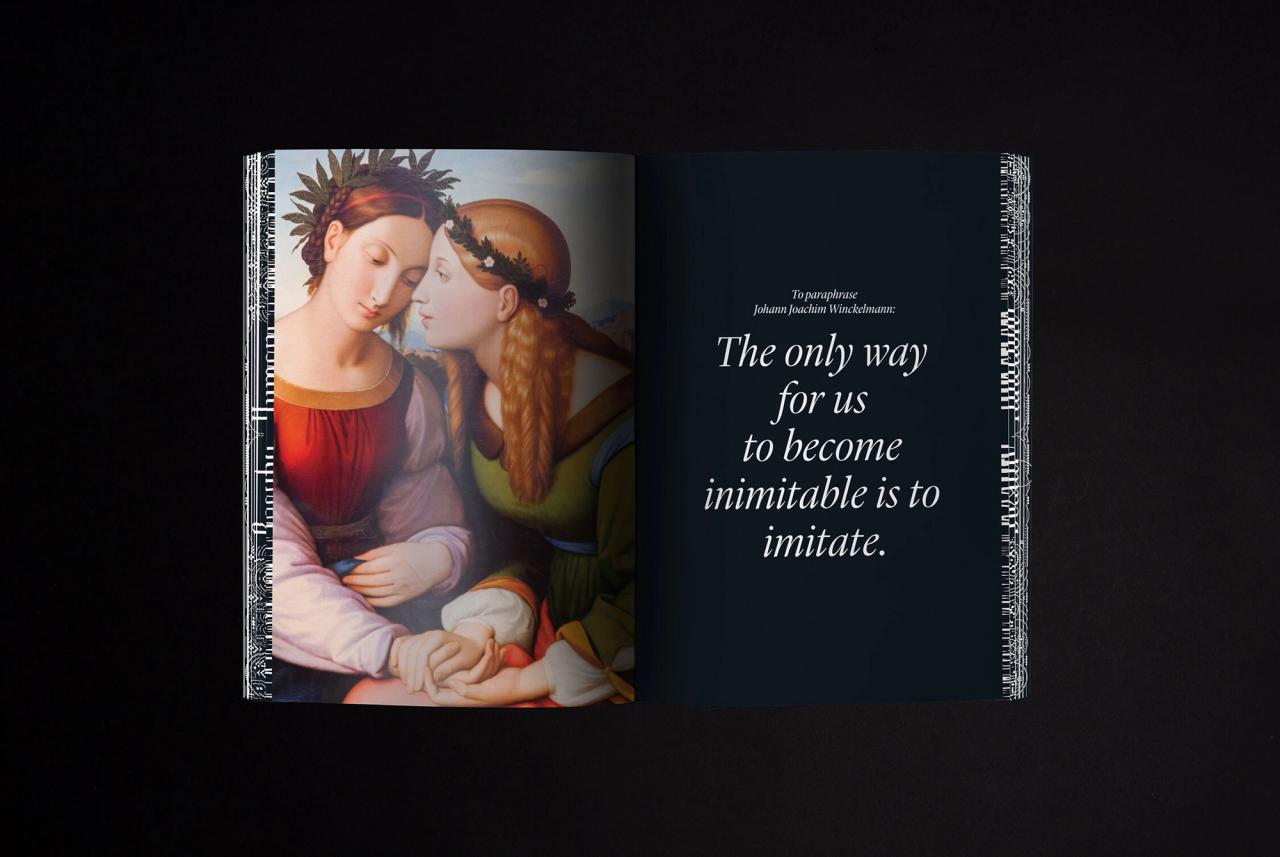

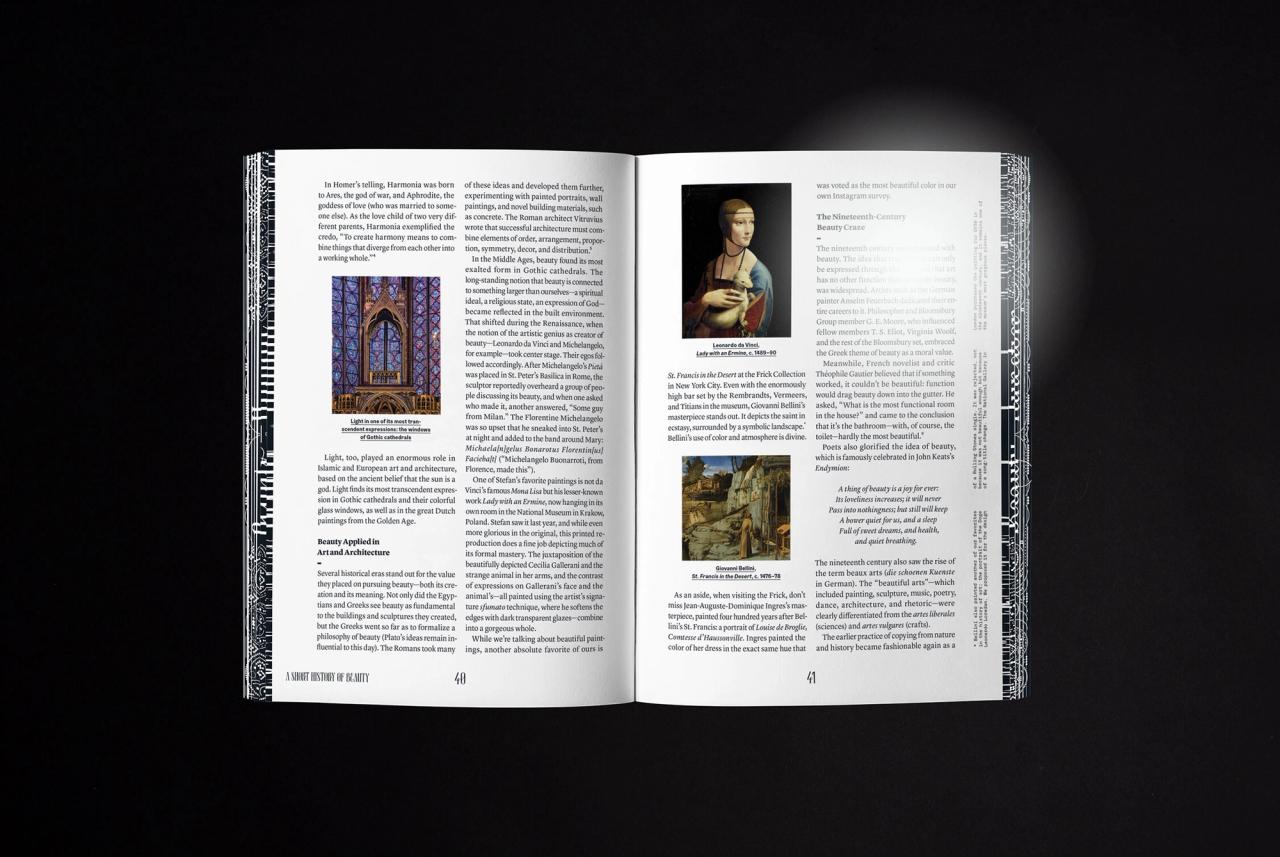

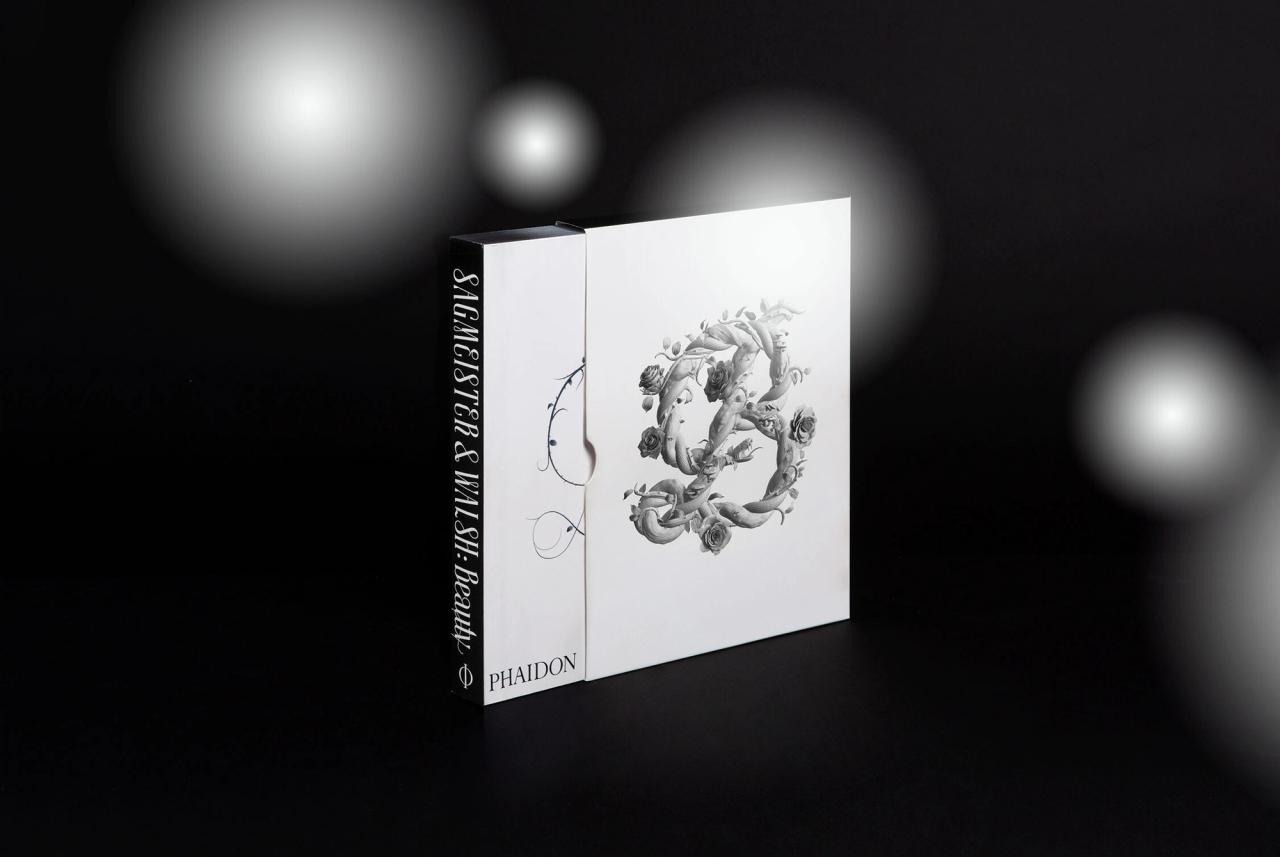

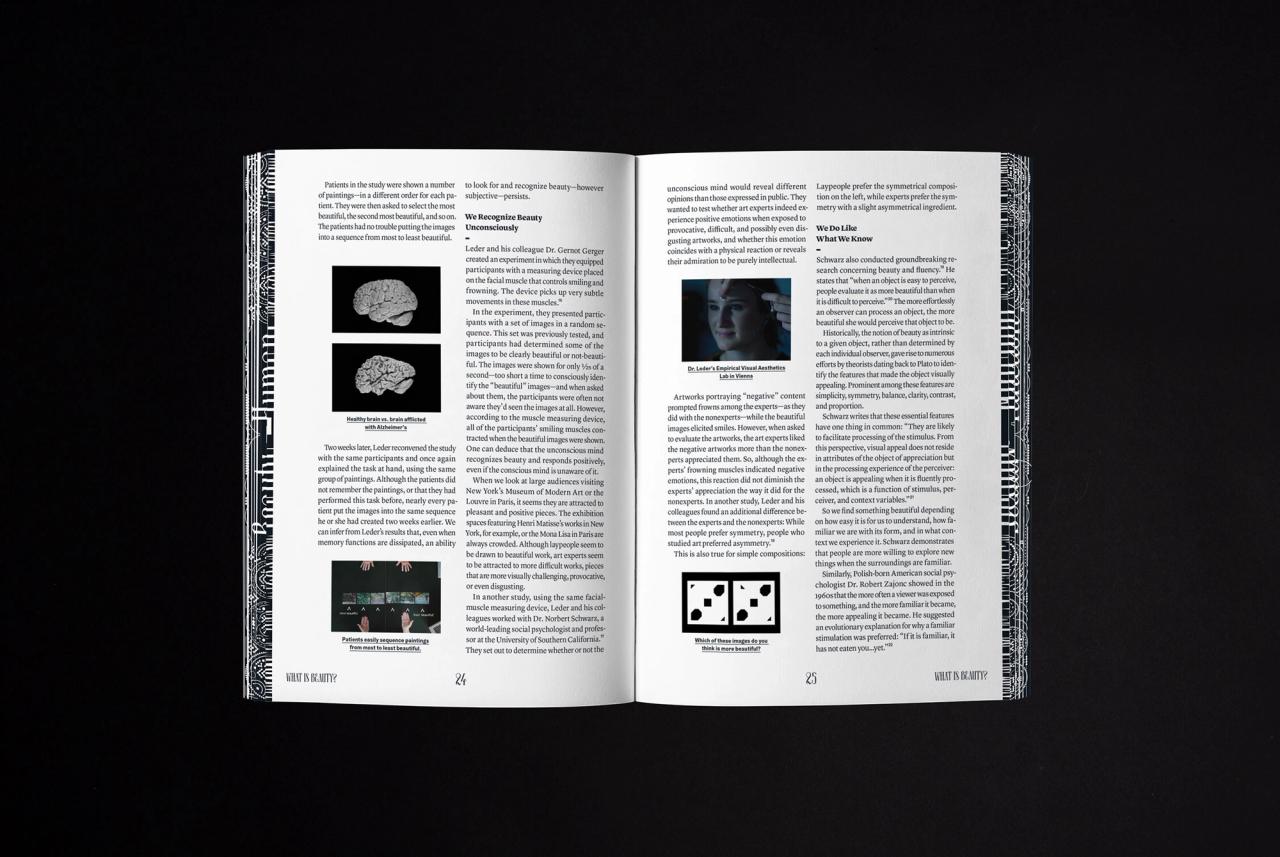

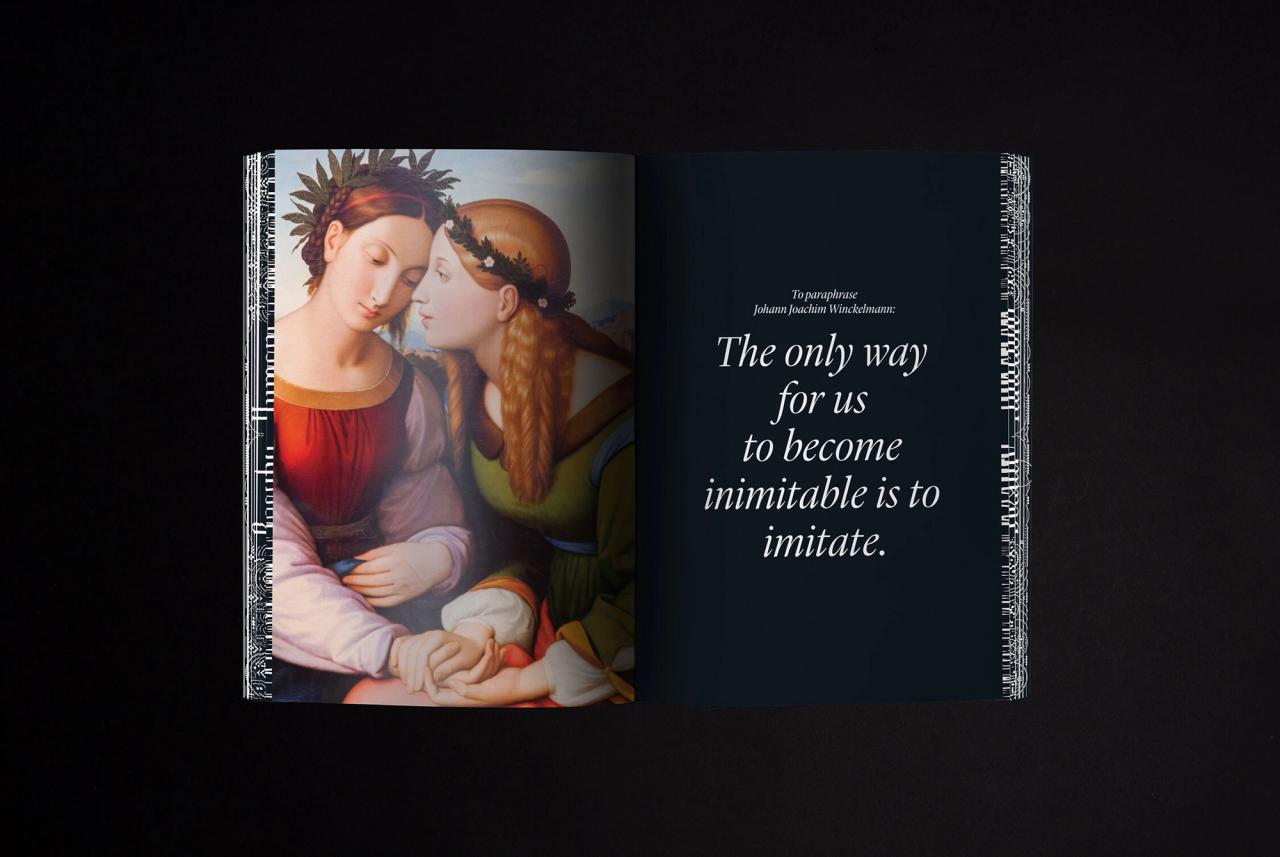

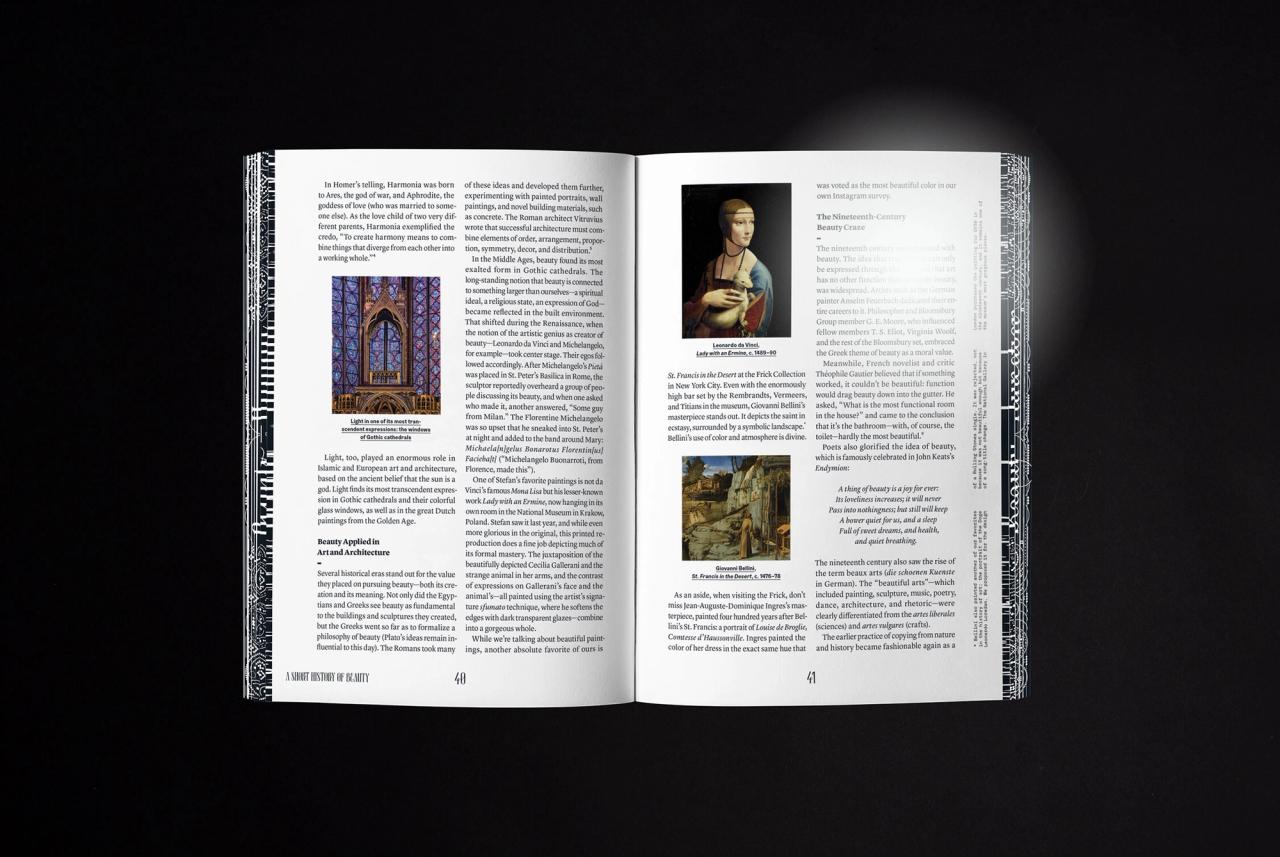

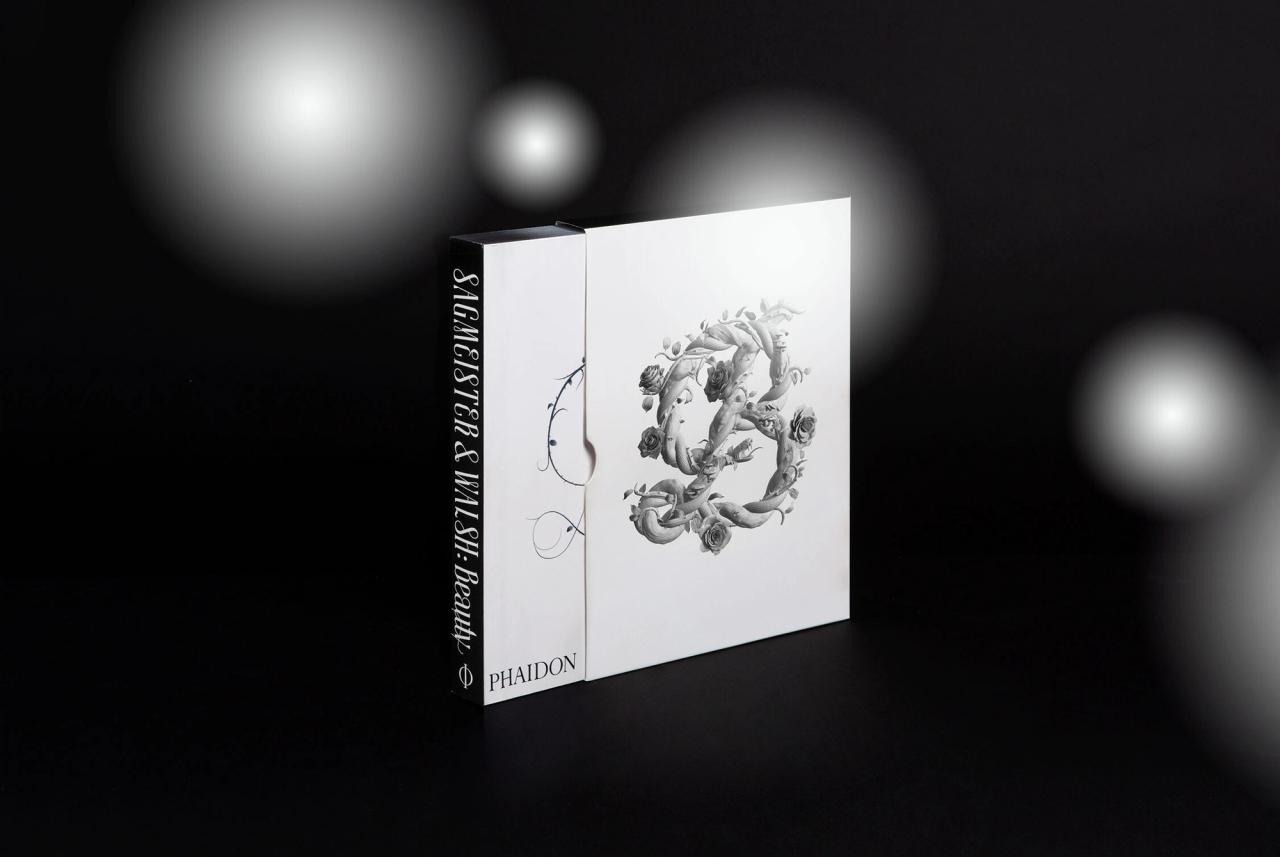

SB: There’s also the book with Phaidon.

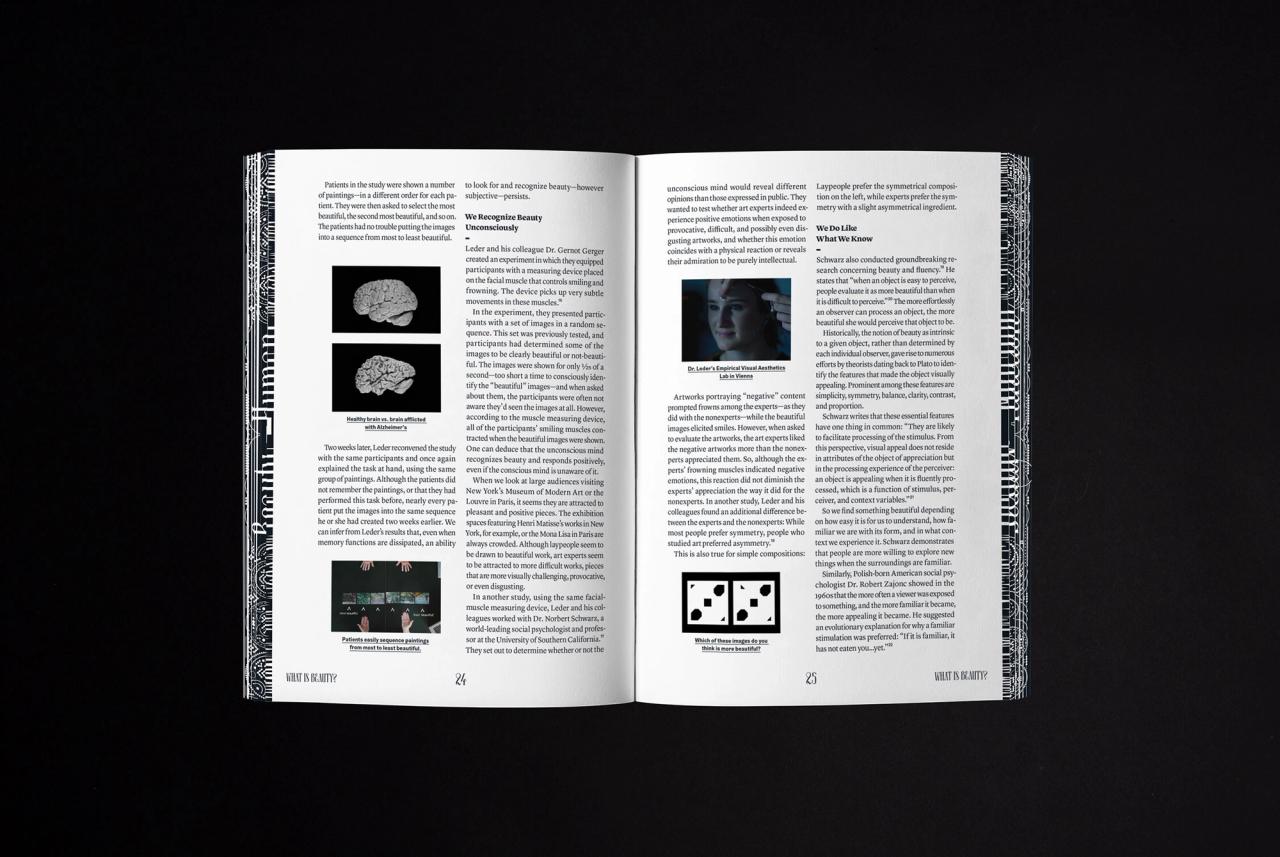

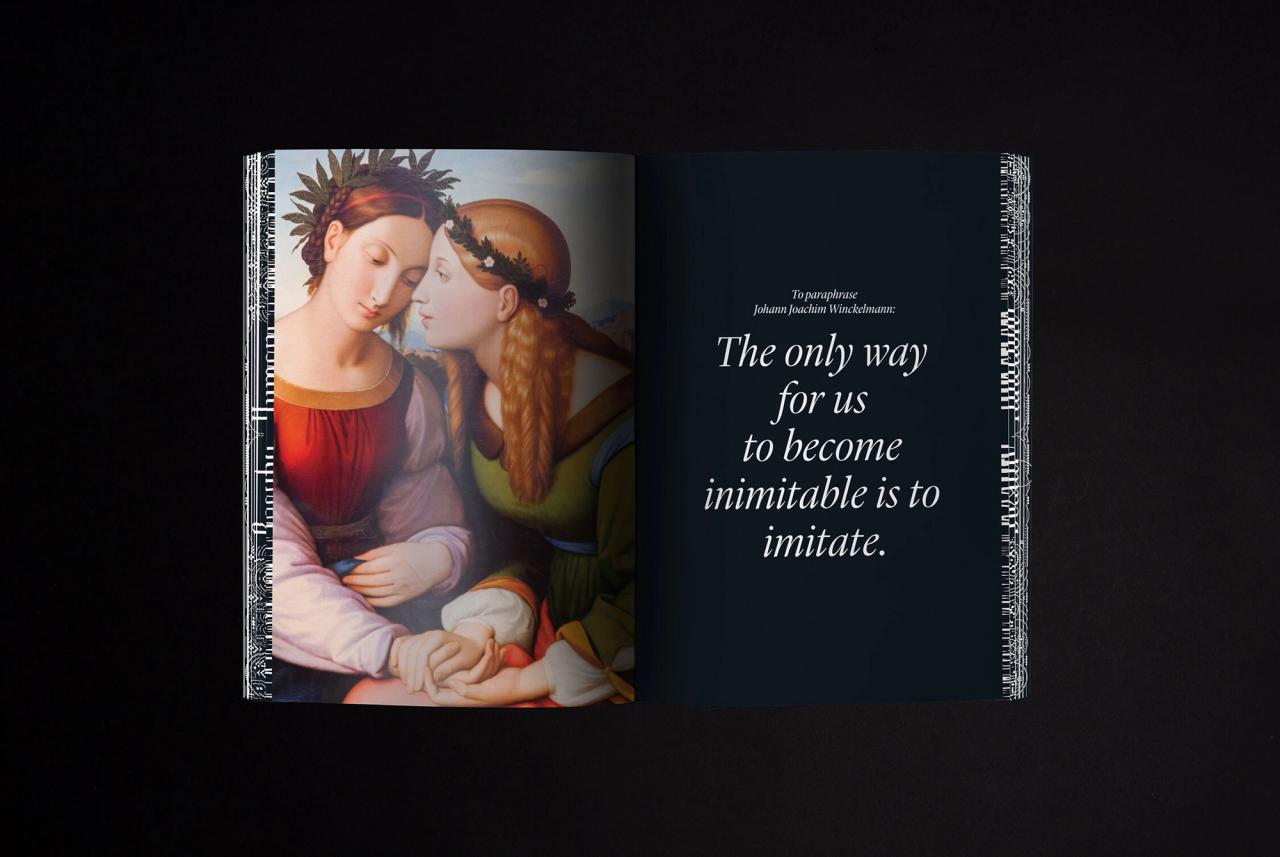

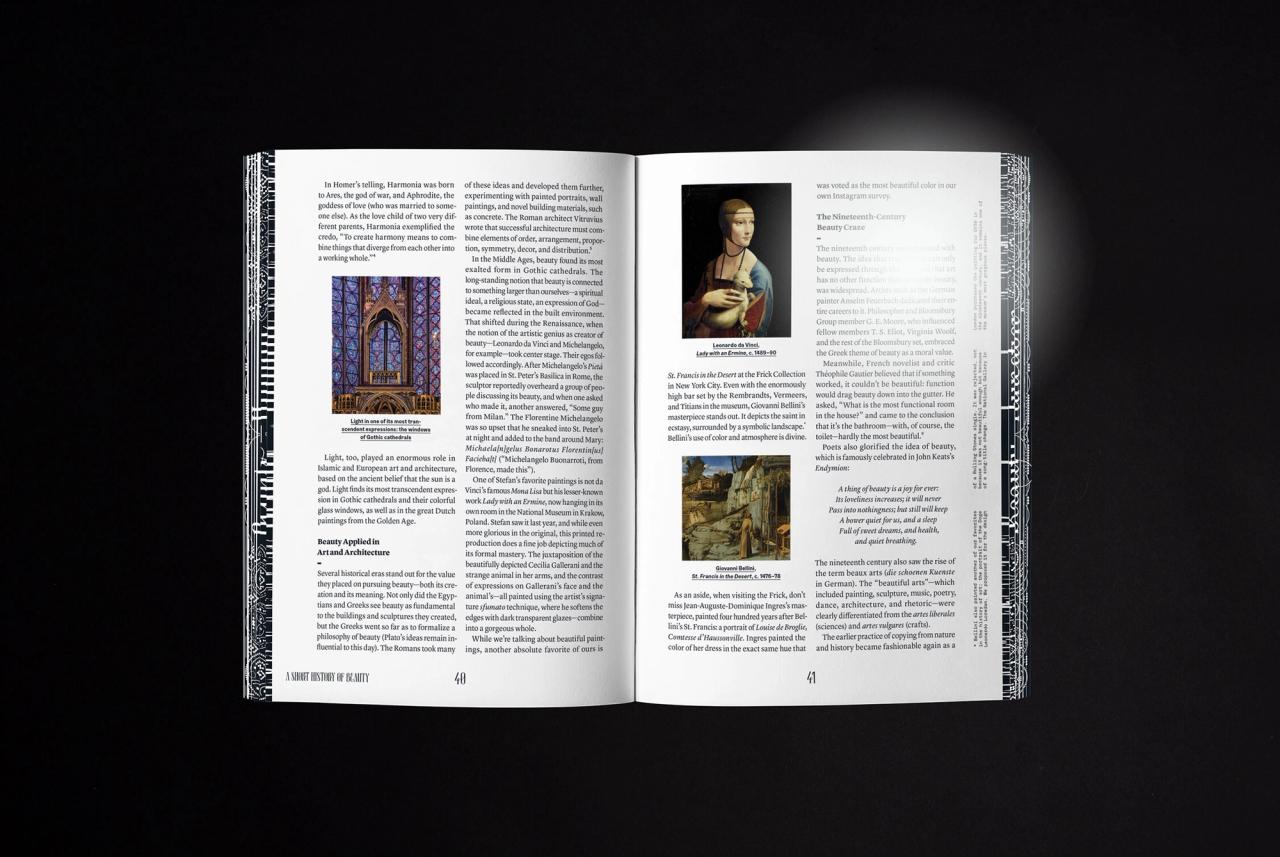

Cover of the book Beauty, published by Phaidon. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover of the book Beauty, published by Phaidon. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Cover of the book Beauty, published by Phaidon. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

Another spread of the Beauty book. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

SS: We were very happy that Phaidon agreed to publish it, so it has proper distribution. And, of course, in the book, you can be a little bit wider and a little bit deeper than you can in a talk or in an exhibition.

Sagmeister in Mexico City during his third sabbatical, in 2016.

SB: To circle back to the sabbatical, how did Mexico City, Tokyo, and this little town in Austria impact your views of beauty? And also, connected to that, having Jessica back in the office in New York, I assume she was also working on this at the same time? What did you learn from the third sabbatical year?

SS: From my point of view, the most fruitful part was definitely Mexico City. This was the beginning, I had lucked into a fantastic house that a friend of mine had rented for me—he lived next door. They were [in a row] townhouses that happened to be all filled with designers or architects. So I had already made a community. Some of these houses, people worked in them. I got up early every morning at six, and a neighbor brought me an espresso, we had a smoke together, and then started working. We basically worked until the evening, and then went to dinner with friends. That was just an ideal situation. I felt like I made what a writing retreat might be like. I’ve never been to one, but it felt like the Mexican Yaddo.

It was also at the very beginning of the idea-finding process. What’s the subject? We made gigantic maps of what could all fit in there: the work that should be a part of it, what can be communicated and how, what might be an interesting way of communicating this or that phenomena. This was also, of course, very much a fun thing to do. Jessica came to visit, and it turned out that after Mexico we were quite far [along in the process]. We were definitely far enough to start mocking ideas up, to basically create a presentation of how an exhibit like this could look. We thought, why not send it to museums to see how that could work? By the time I had moved on to Tokyo, my own time actually was occupied with dealing with museums, which was much less fun.

Villa Müller in Prague, designed by the Austrian architect and theorist Adolf Loos, who Sagmeister notes as a key figure in paving the way toward Modernism. (Photo: Miaow Miaow/Wikicommons)

By the time I hit Austria, this then became a much more real thing, where it was already, I think, by that point clear that we were going to start in Austria. Which was also very close to my heart, not only because I’m Austrian, but you could really argue truthfully that Modernism started out of Adolf Loos and people like him. A lot of the foundation for reasons why the second half of the twentieth century became so functionalist, you could argue, really started in Austria. It made a lot of sense to have that counter-argument exhibition be in Vienna. I also know the museum, know some of the fantastic curators, architects that they have there.

I was confident that we could create a very difficult-to-make exhibition there because this is an exhibition that is not about hanging readymade things onto the wall. The vast majority of the things we show there were built from scratch and needed to be made. There was lots of back and forth on the financial ramifications of these things: Who pays for this all? But also: How do we make it? Who’s responsible for it?

SB: It’s interesting, in the end, your third sabbatical doesn’t sound so similar to the second one, and the first one was also different, because for that you were grounded in your homebase. How did this third sabbatical open up this project to you without feeling like work? It was almost like a “beauty sabbatical,” I guess.

SS: You’re totally right. The three sabbaticals, now being able to look back, were quite different. The first one, I would say, was very much about thinking. I really executed almost nothing. The end result of the first sabbatical was a full sketchbook. The second one, we executed quite a lot. I had people, interns, and young designers coming to Bali to work with me. I basically had a design studio there. Not only did we execute all that furniture that was made, but also executed parts of the film—we were filming a lot. There were a lot of tangible results from this.

The desire for the third one was to be somewhere in between, to do a lot of thinking, but also to have some tangible results. And I think that that was true. But, looking back, the three parts were still quite different. My favorite one, without a doubt, was the first one, which was very much about thinking, and about making sketches, and how could you implement some of these ideas? I think you’re right in that the last two-thirds [of the third sabbatical]—particularly the middle part, in Tokyo—felt actually quite worky and not so much like a sabbatical.

A giddy Sagmeister in Tokyo during his third sabbatical, in 2016.

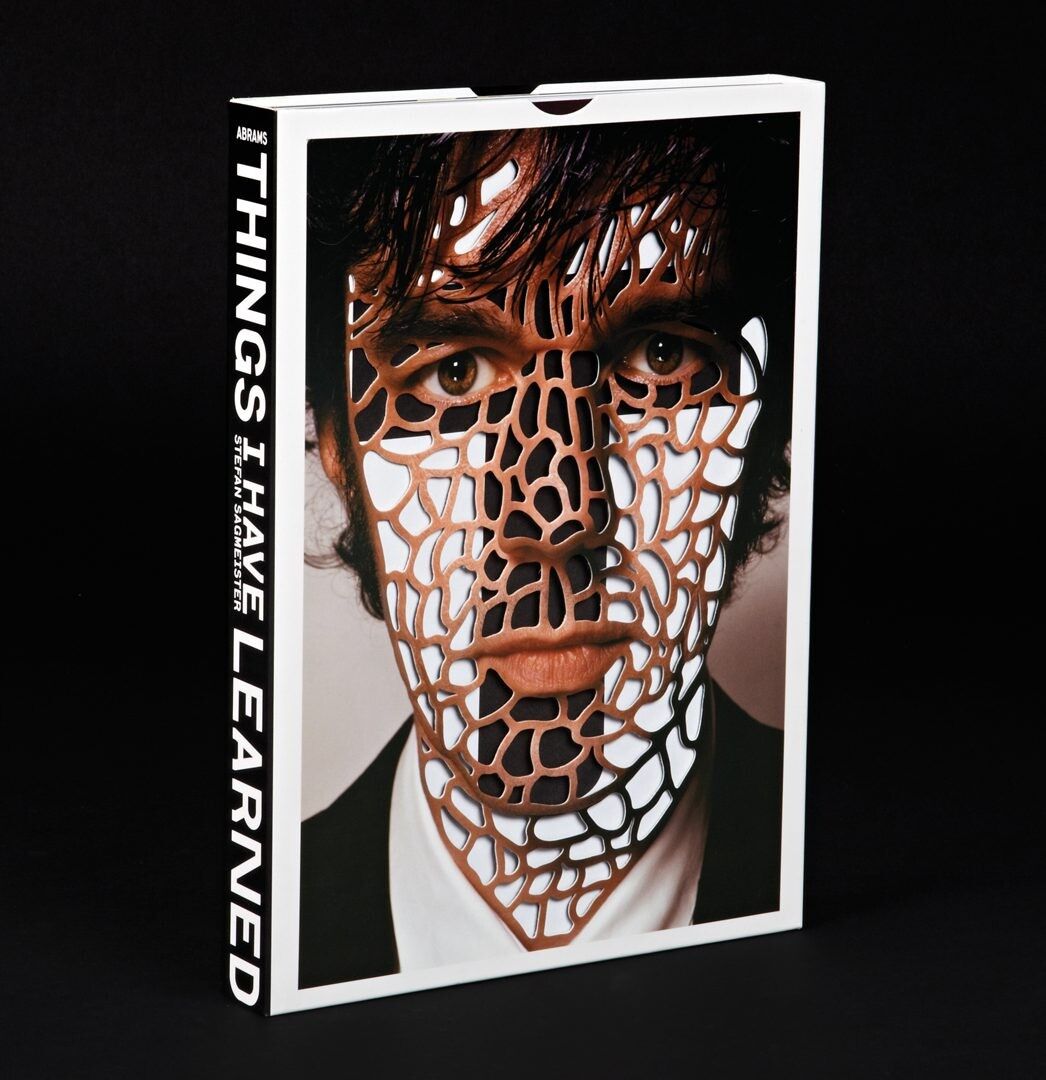

Book cover of Things I Have Learned in My Life So Far, published by Abrams. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

SB: [Laughs] Right. I think it’s interesting that the sabbaticals have shaken up your schedule, your life, and your mode of doing things. In 2013, you put out [an updated edition of] your book Things I’ve Learned in My Life So Far. One of those “things” is actually about time and, I think, a direct reference to why the sabbatical matters. That thing is, as you put it, “over time I get used to everything and start taking it for granted.” Tell me a little bit more about that idea. Why do you think it is that, in time, things become normalized? Why does something that might be extraordinary, happening before our eyes, somehow feel normal?

SS: At the time that I wrote that sentence down, or I think even made a thing out of it, I really thought that this was sort of a personal flaw of mine—that this was happening only to me. And then, when I started reading more psychology books for The Happy Film or “The Happy Show,” it turned out that there’s a giant field in psychology that is dealing with that, and that it’s a problem of humanity that most people go through.

Of course, as soon as that became clear to me, I thought, Well, of course, pretty much everyone I know, or even if I look at my students—I teach a graduate class at SVA—the majority of those students would see design as a calling. They really want to do this, and they want to do this as best as they can. I see my role as a teacher there not as one to motivate them—most students are pre-motivated. They really want to do this. But if I run into them five years after their graduation, many of them see what they do as a job. That feeling that it became a calling disappears somewhere, or is sort of knocked down through routine, through difficult situations at work or with clients, or just by having done things now over and over again. I remember talking to a very smart young fashion designer, and she said she worked for a big fashion brand in the city, with its own building. She said that the conversation in the elevator starting on Wednesday is basically reduced to “only two more days until the weekend. Tomorrow is Thursday, and then just another day until it’s Friday.” I understand it, but it’s also very sad. To work for a fashion brand that very likely you had to work hard to get into anyway, because it’s not easy to get a job in fashion, then to get sandpapered down to that sort of knobby attitude—a “thank god it’s Wednesday evening” feeling. I’m sure there are many strategies out there to reduce the possibility of this happening. The one that I found worked the best for me is the sabbaticals.

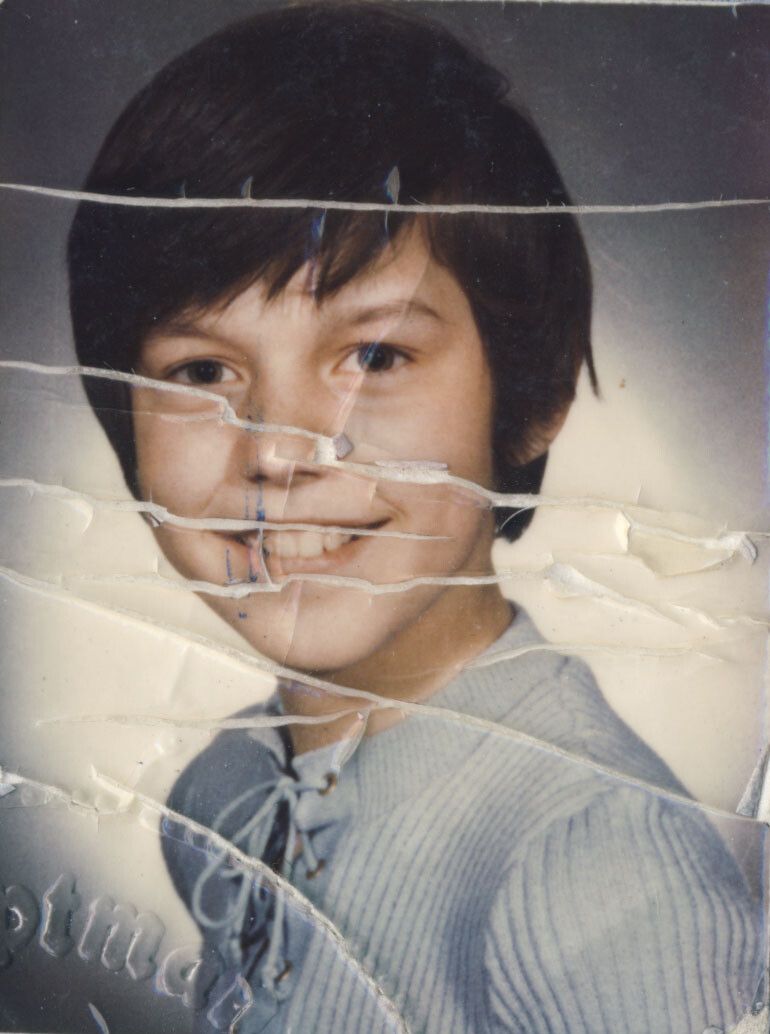

SB: I want to go back in time now, to little Stefan in Bregenz, Austria, in the 1960s. Watching your family run this multi-generational shop, and your grandfather, who was a sign painter—I think that’s fascinating to think about in terms of the beauty conversation. Your grandfather had to paint things to capture attention, to draw the eye in. This period, your youth growing up in Austria, this time in gestation, what sort of impact did Bregenz have on you, did your family have on you, on leading you on your path to becoming a designer?

Sagmeister as a child.

SS: Obviously, a big—a huge—influence. Bregenz is five miles from the Swiss and three miles from the German border; it sits in a three-country border. I would say that the people in the eastern part of Switzerland, the western part of Austria, and the southern part of Germany are probably more alike than how they are in comparison to the rest of their countries. We definitely have much more in common with our Swiss neighbors than we would with, say, the Viennese. I would almost call that [region] “the Japan of Europe” in many ways. The similarities would be that it’s a somewhat unemotional place—it’s not really seen as favorable to show emotion in public. Jobs are taken very seriously, and to do them well is taken much more seriously than to make a lot of money. There’s a pride in doing something well. That’s seen as a big moral value. You would get status from doing something well, and it wouldn’t really matter if that is doing a craft, like building a table, or if that is running a restaurant or a store, or being a graphic designer, for example, or being an artist.

SB: So what were some of the things as a youth that you were doing really well? What occupied your time?

SS: Well, I can tell you what I was doing really badly, which was being in a band. Terrible.

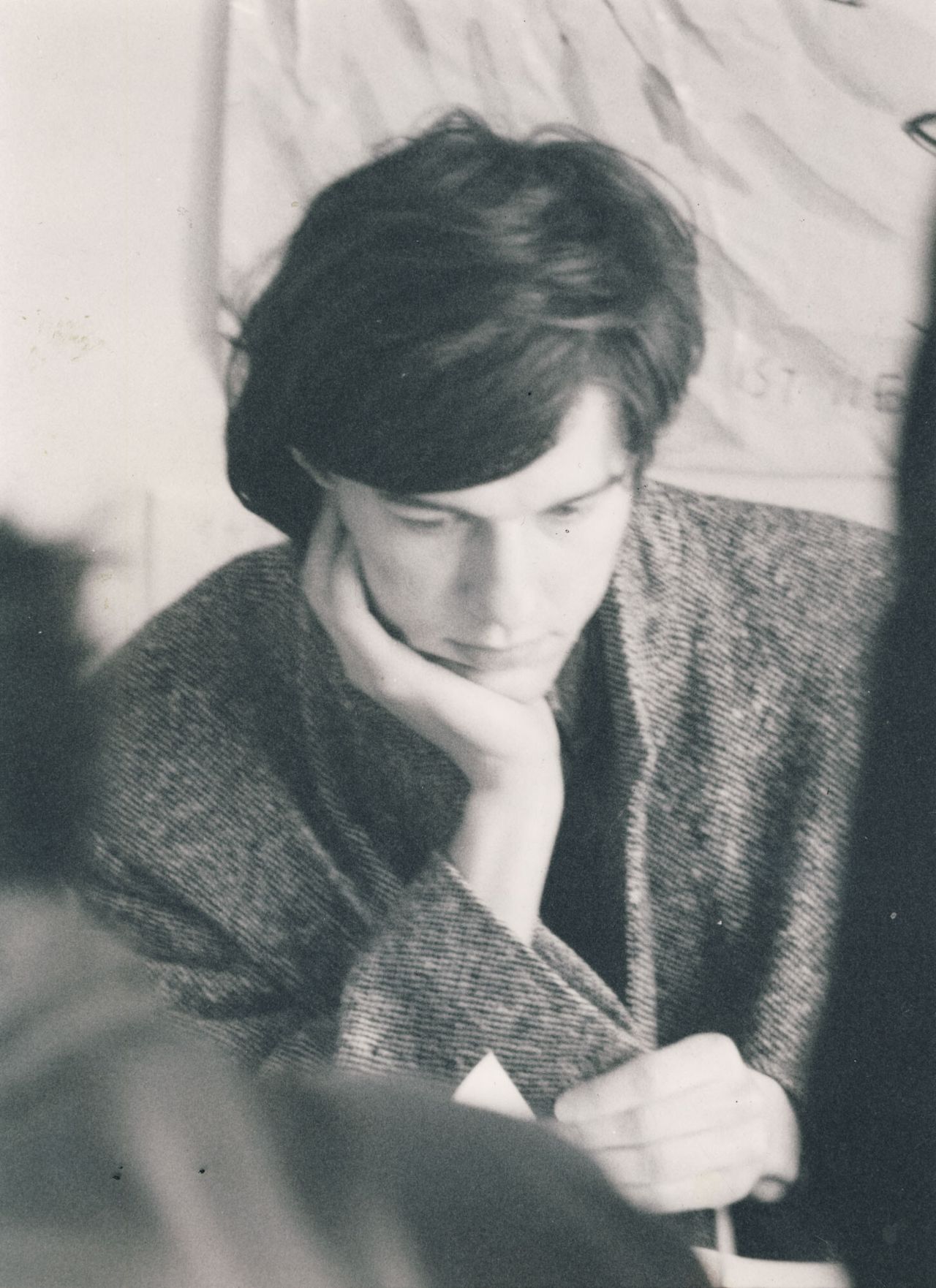

Sagmeister during his band years.

Sagmeister in high school.

SB: [Laughs] What instrument did you play?

SS: I sang and I played the flute. [Laughs] Which already tells you about the kind of band it was. It was a sort of prog rock sort of thing, but still, a big learning experience for later on, because we took all the things seriously that I found out you shouldn’t take seriously, and left out all that was important.

Probably the first thing that I did well was around fifteen or sixteen, when I started to write for a magazine. I wasn’t really a good writer. I was an okay writer, but it turned out that no one was really interested in doing the design for this magazine, so that job was open, and I started doing it. I’m not sure if I did it better than other people, but I was the only person who was interested in doing it. It turned out that I then, over time, developed an interest in doing it well. And the magazine was culturally involved, organized music festivals or a demonstration here and there. It required graphic material—posters, leaflets, things like that. Considering that I already did the layout, it also fell to me to do those, and that seemed interesting. We printed stuff ourselves, so if you designed something, it got printed, we put it out there, it hung around, it showed a reaction. You’d put a poster up, and five hundred people would show up to that event, so it also seemed powerful, it seemed to work. It seemed a possible [career] route. And from my music days, of course, I got interested in that world, in music covers, and I figured this was a viable job—

SB: Then … [Laughs]

SS: Then. [Laughs] Very much so, yes. Then. And that seemed—

SB: A way to marry music and design.

SS: Exactly.

SB: From there, you went to study in Vienna at the University of Applied Arts, and then had a scholarship to come here to the States and study at Pratt Institute [in Brooklyn].

SS: You know everything.

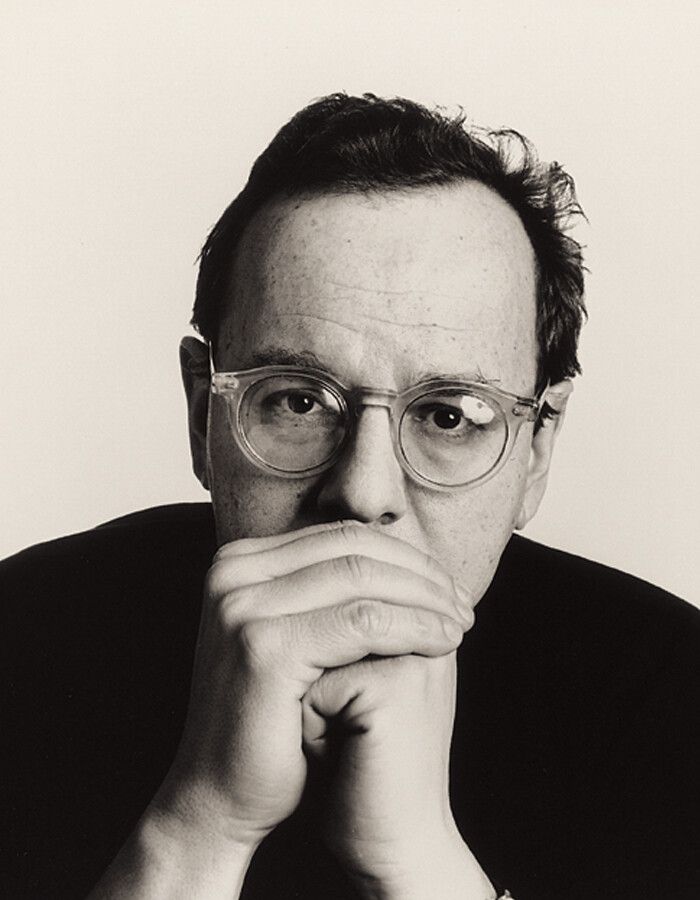

Tibor Kalman, who was Sagmeister's mentor. (Photo: Courtesy ADC)

SB: After that, you lived back in Vienna, then went to work in Hong Kong. Then you came to New York to work for your mentor, Tibor [Kalman]. How did it come to fruition that you came back to New York? Did you always know that you were going to come back to New York?

SS: I did not. Basically, because I had come with the scholarship, it came with a two-year home residency requirement. I had to go back, or I had to pay all the scholarship money back. So I went back to Austria. Then I worked in Hong Kong. But during my thesis time, I had bothered M&Co, the design company that Tibor had done, endlessly, [asking] to do an interview with Tibor. After thirty or forty calls, I actually did get that interview with Tibor. I sent him, at the end, the finalized thesis, which I found out much later he really liked and thought was well done. Even though it was a written thesis. From then on, I was in contact with him. He sent me stuff that he was proud of, and I sent him stuff that I was working on.

SB: It was a dialogue.

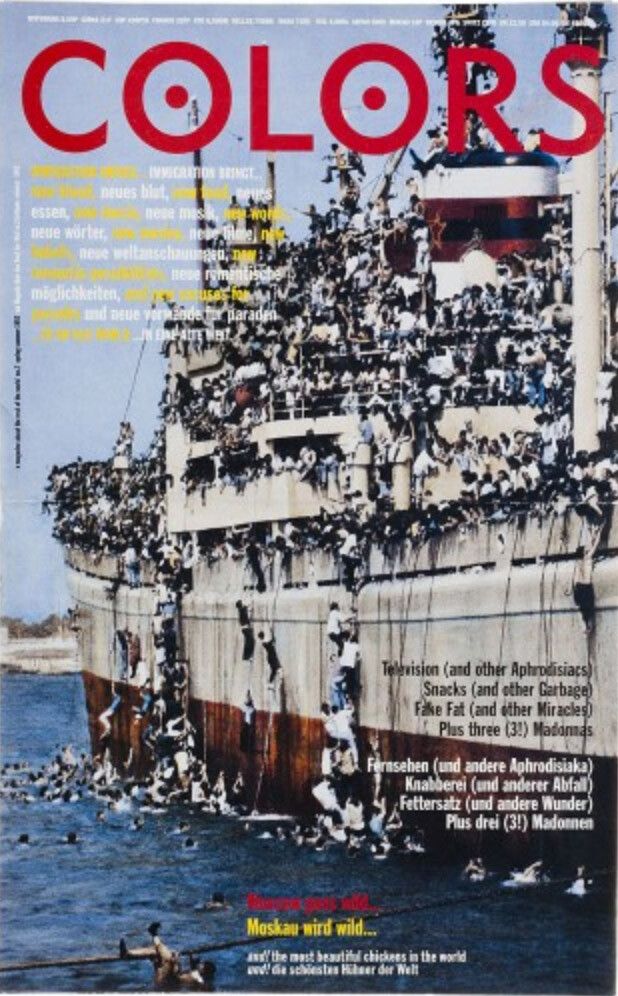

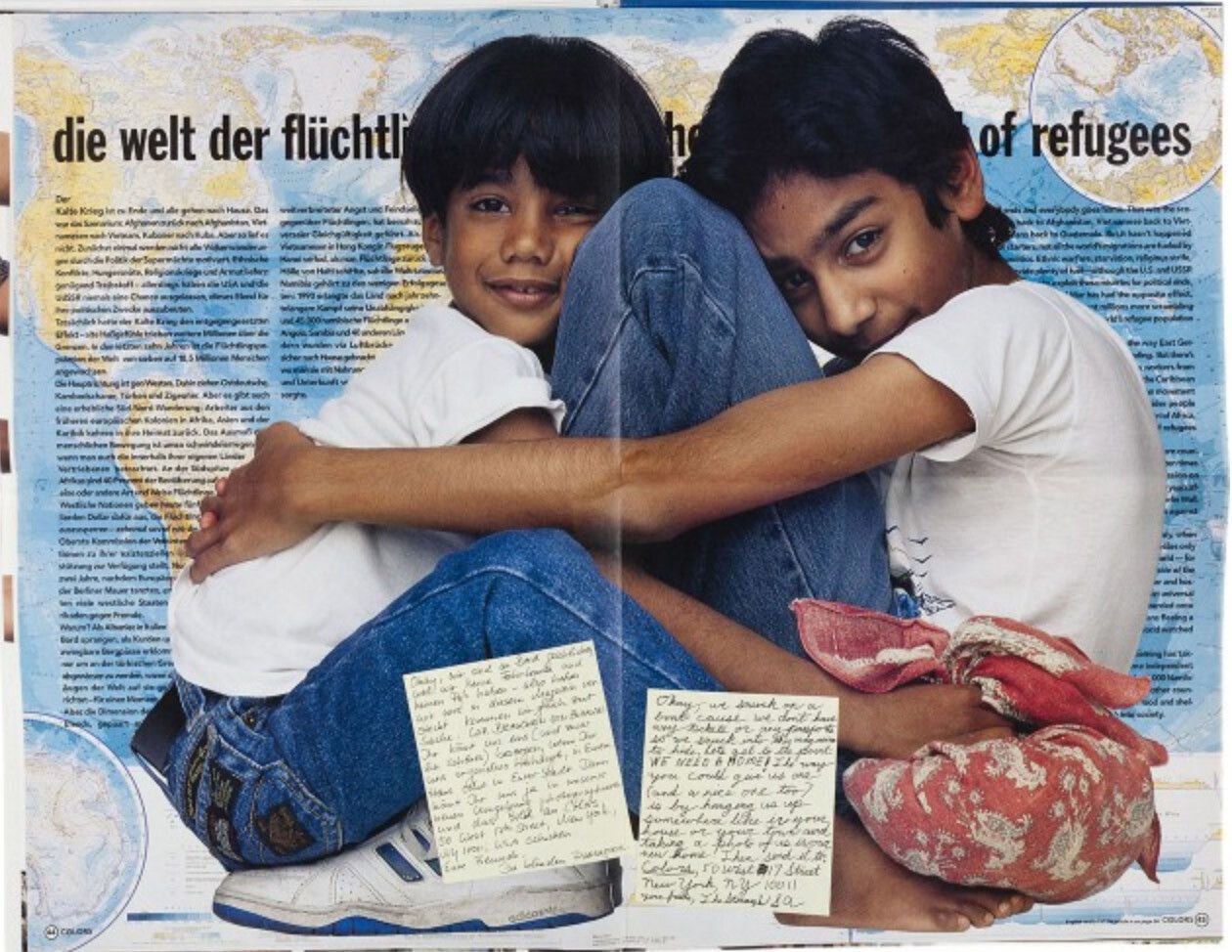

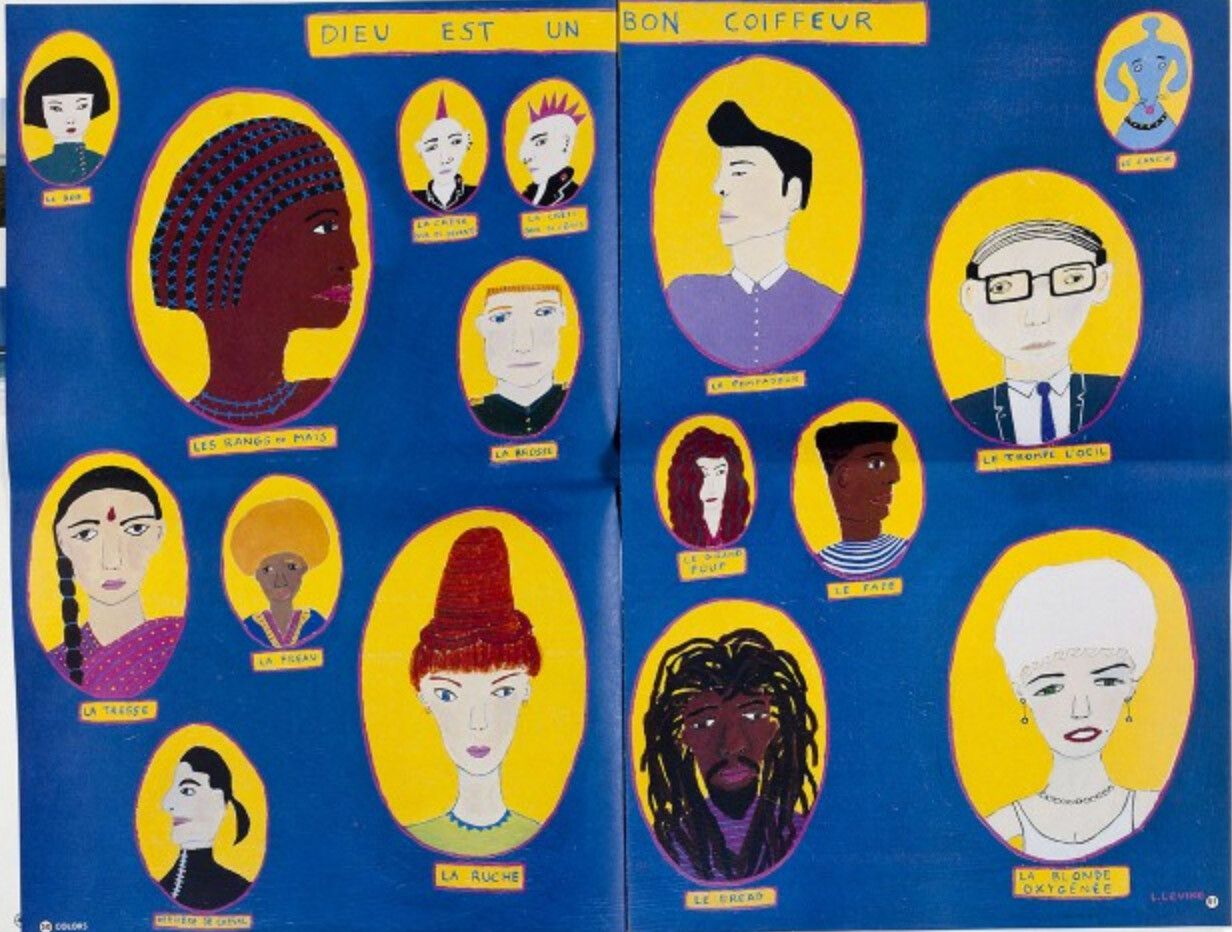

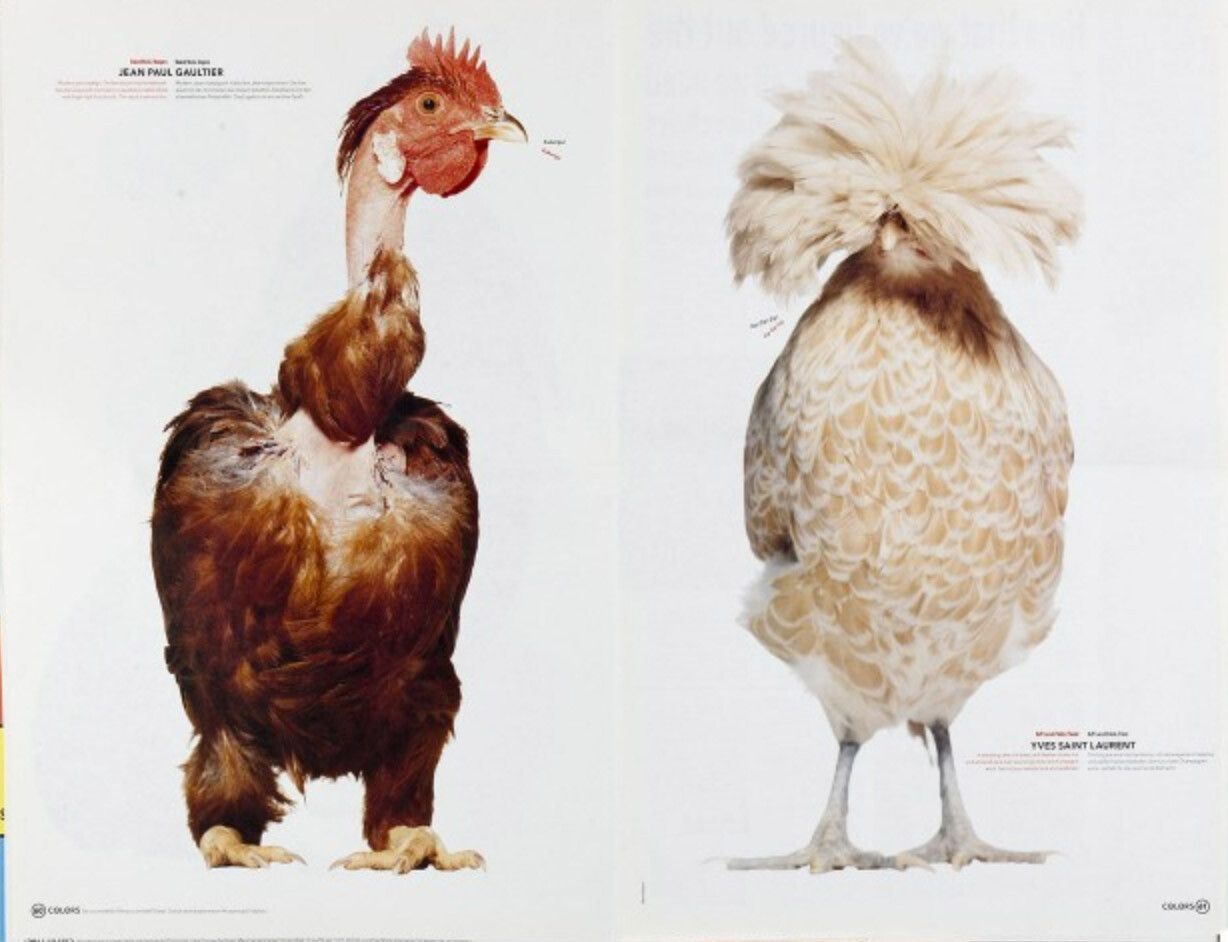

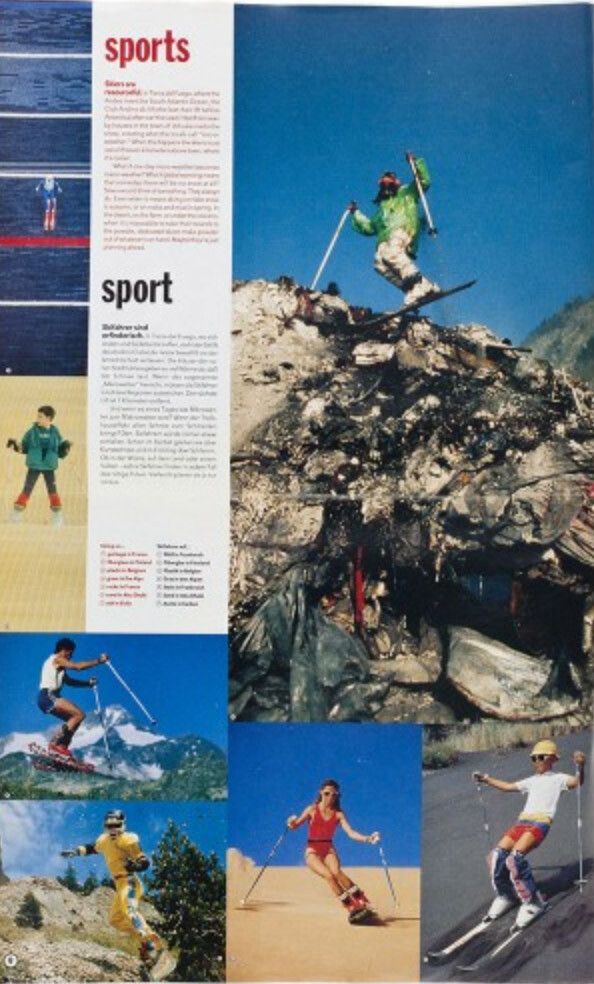

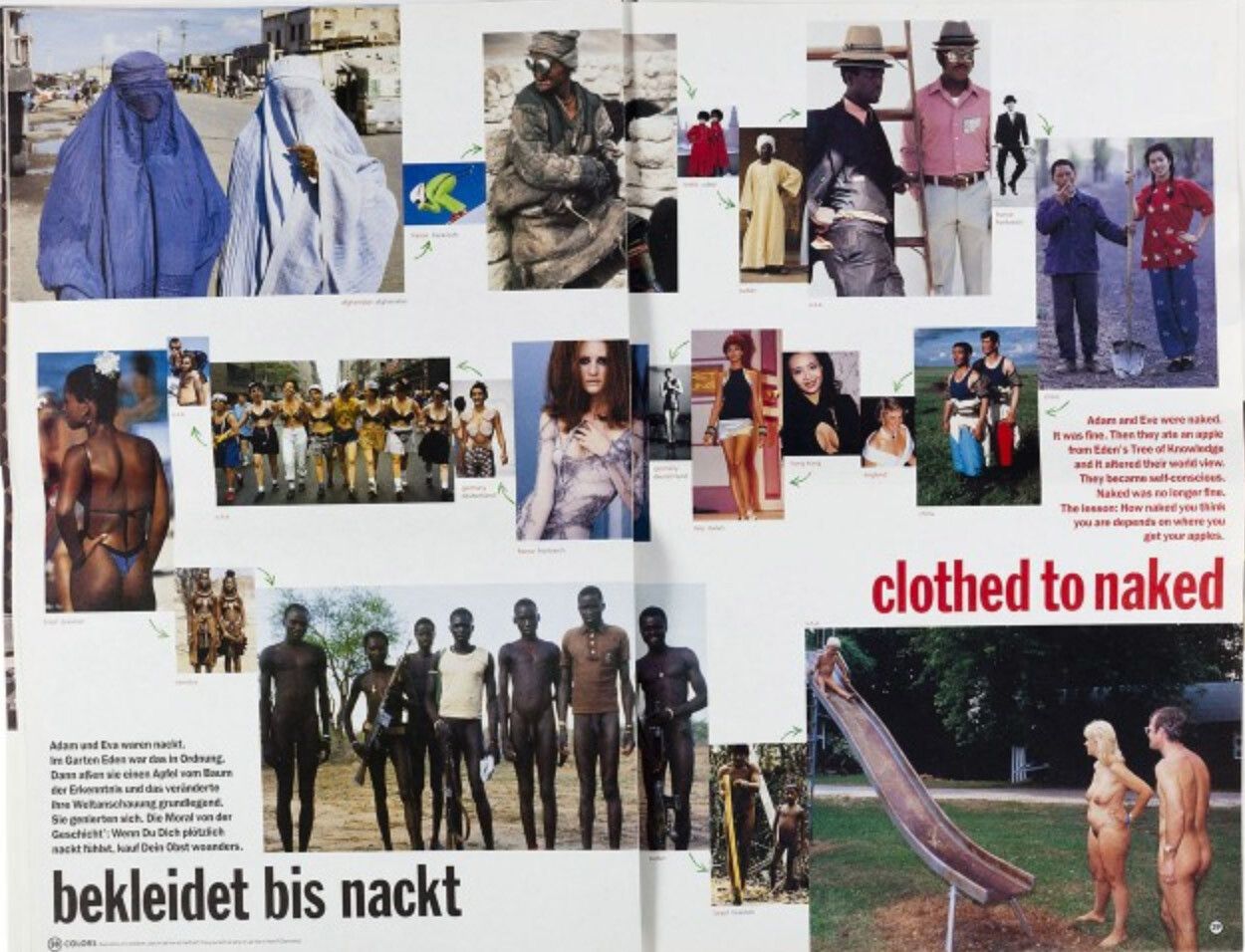

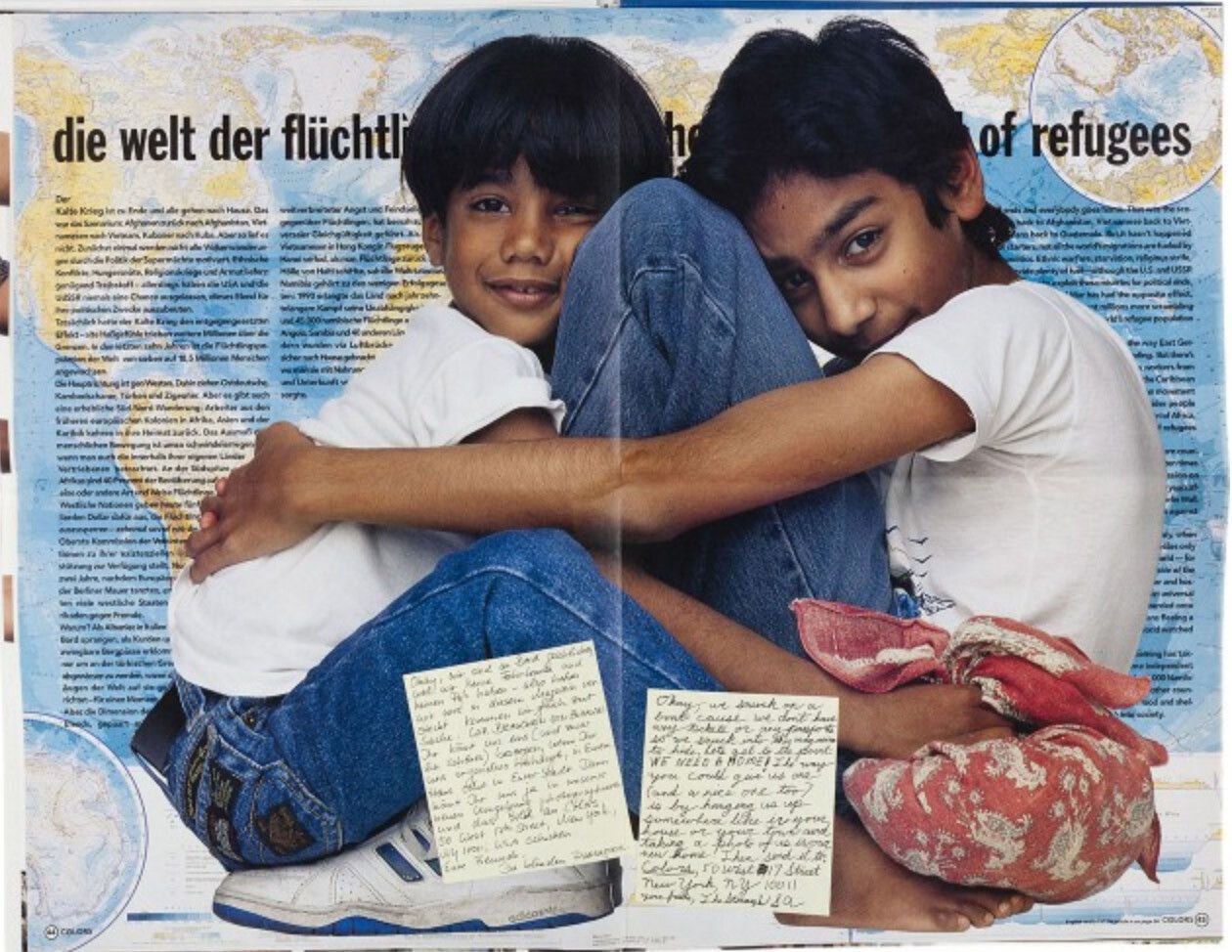

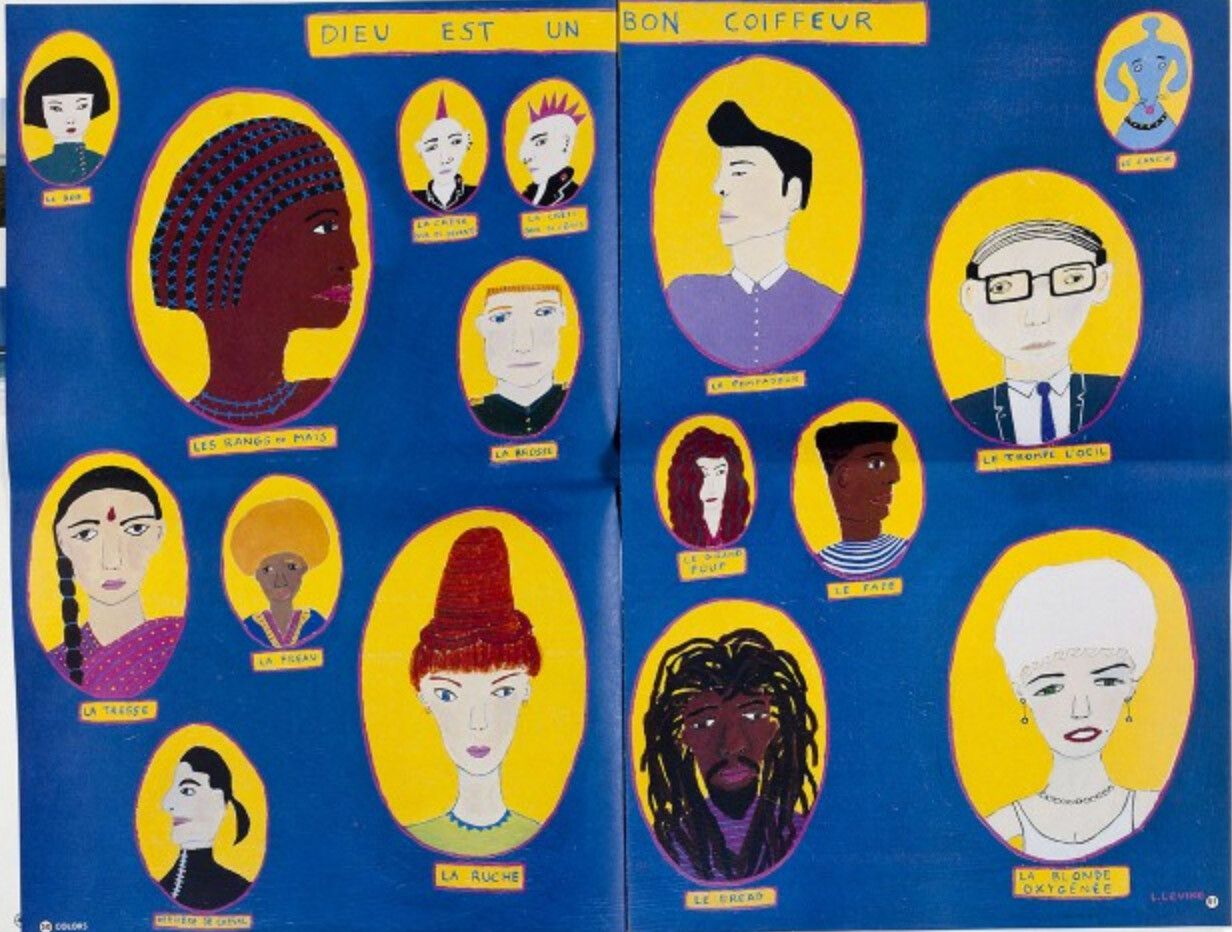

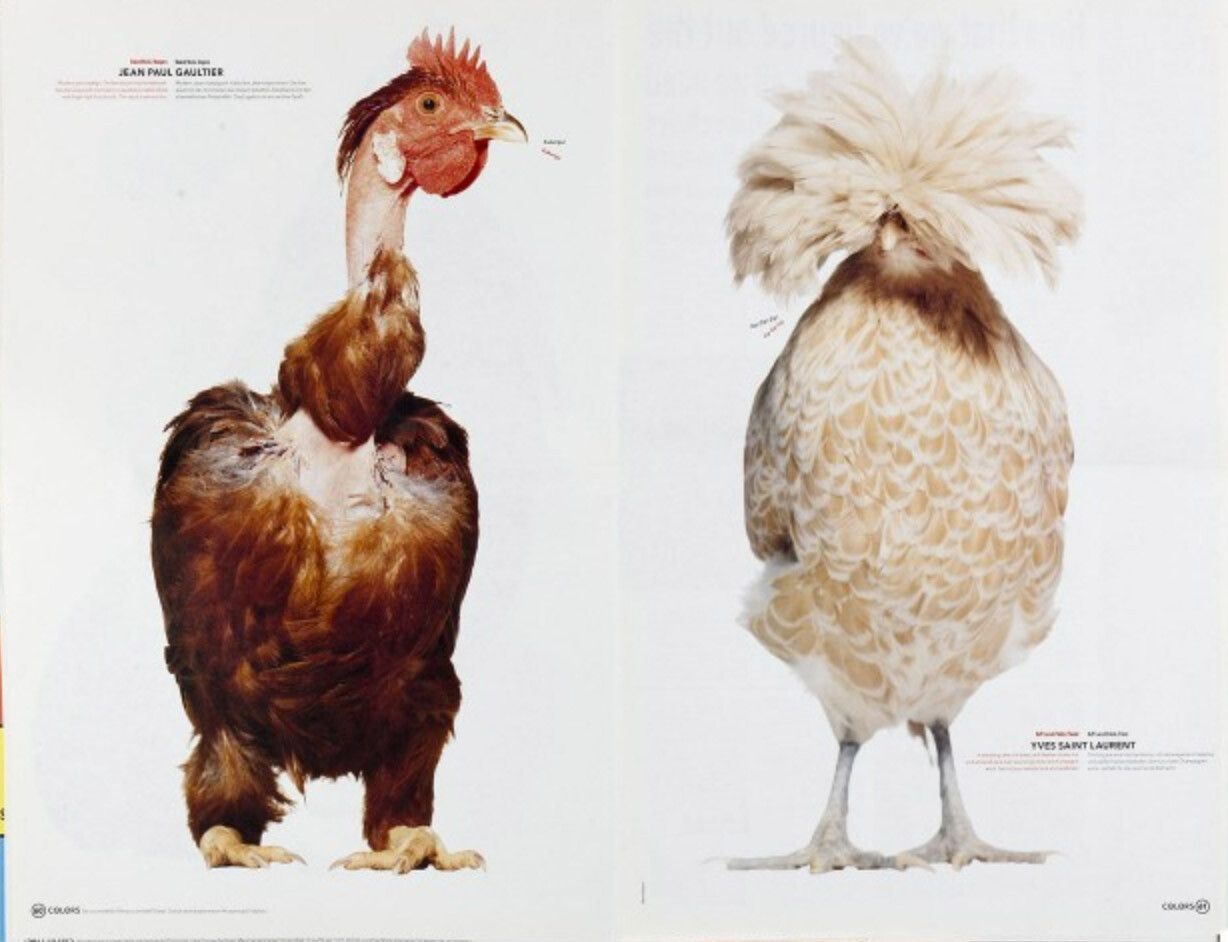

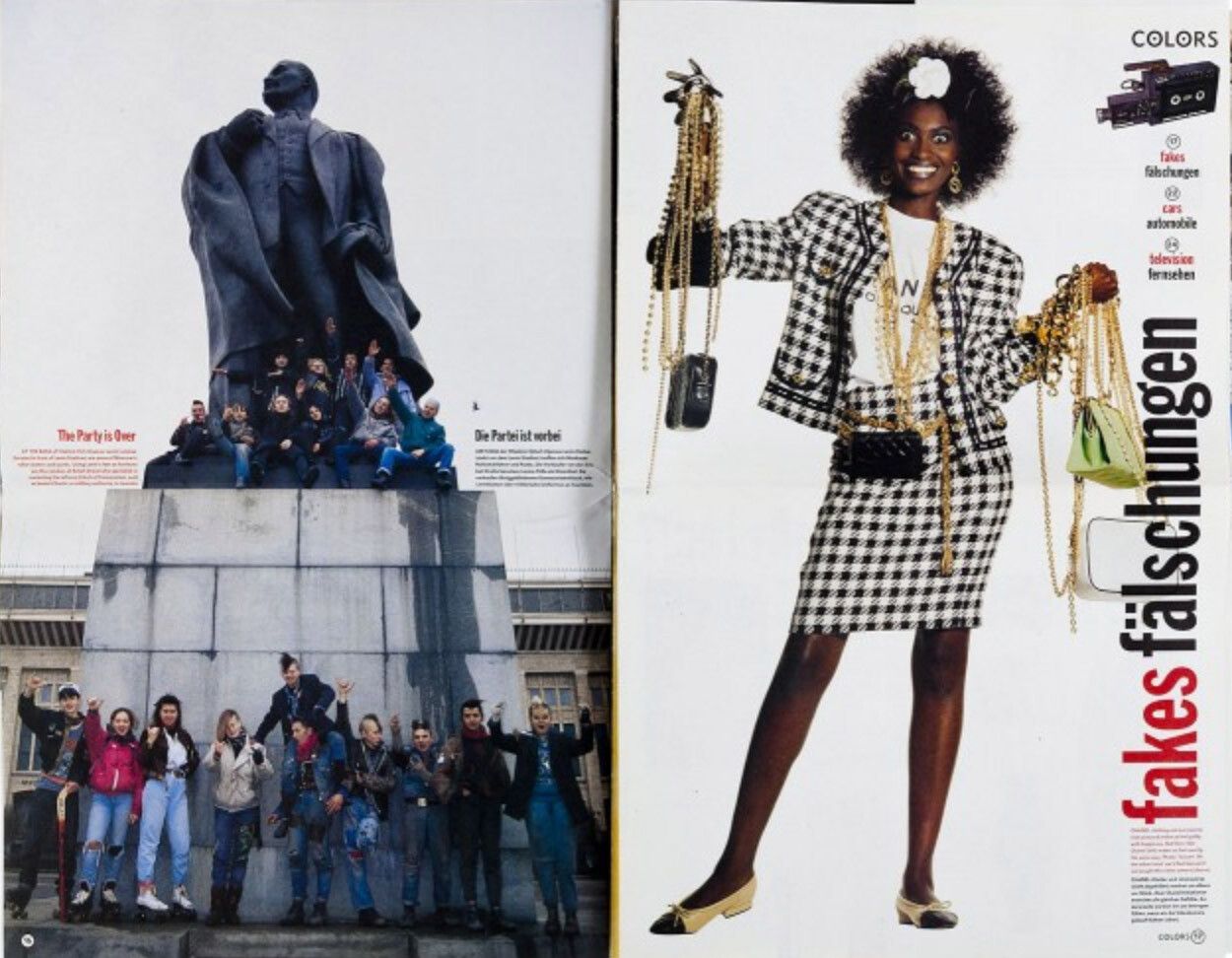

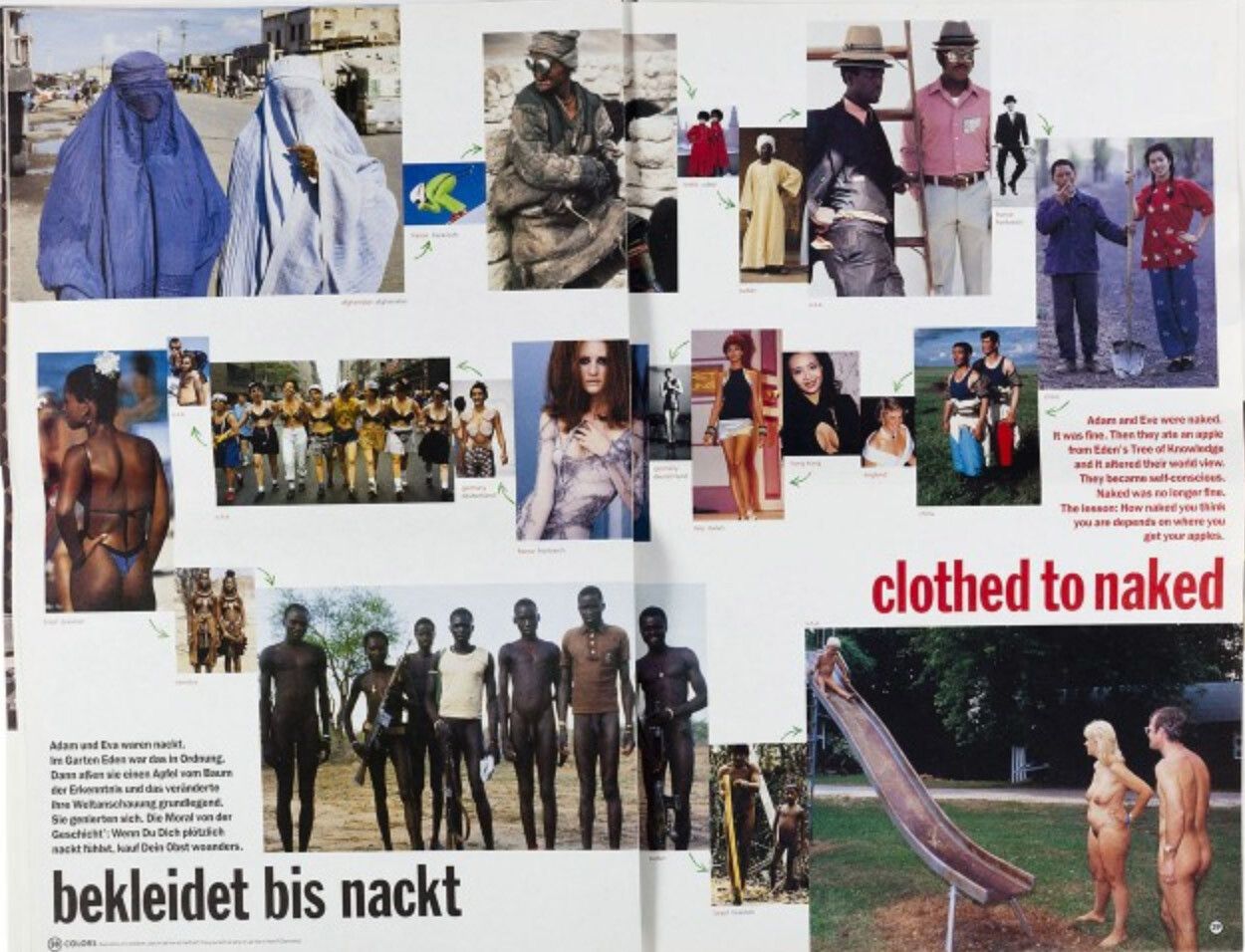

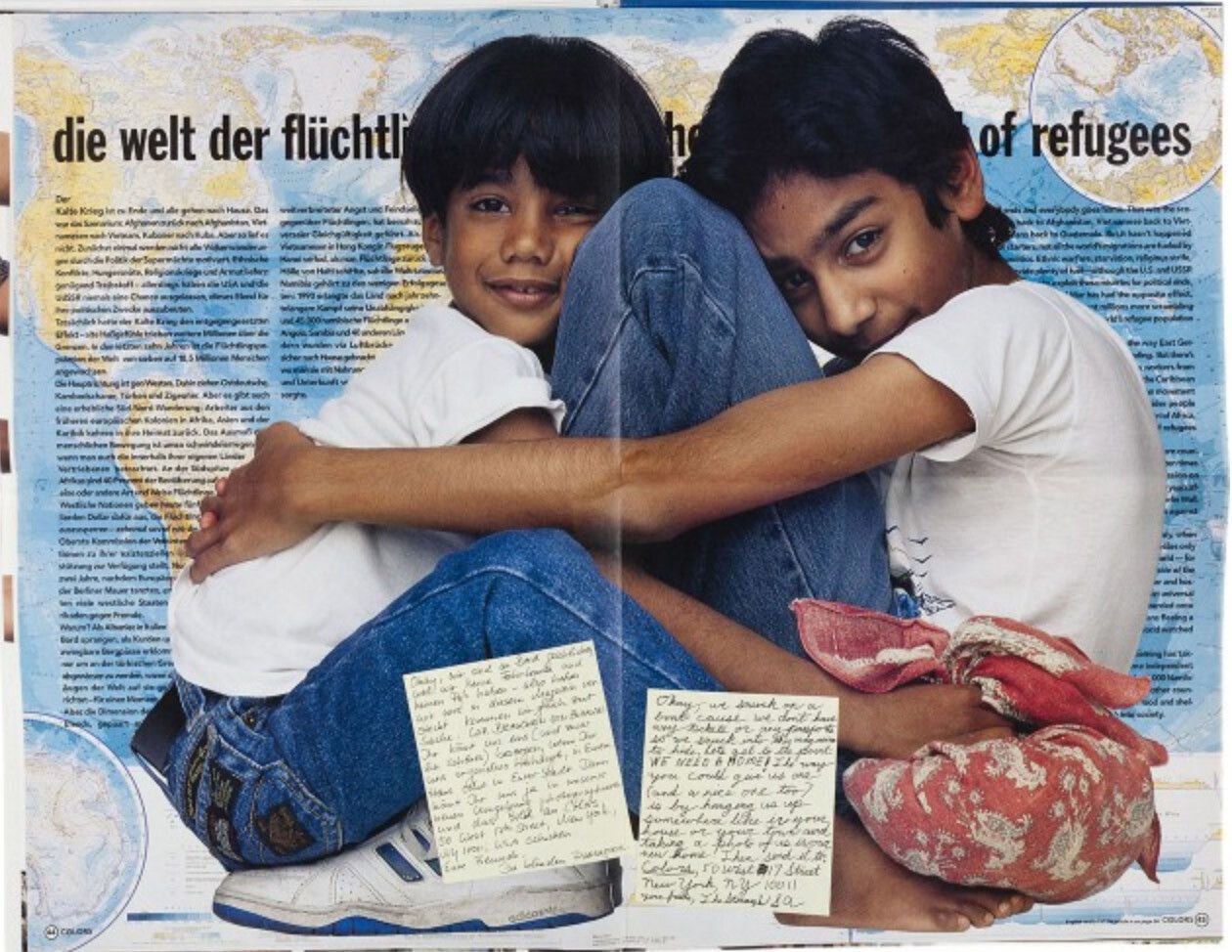

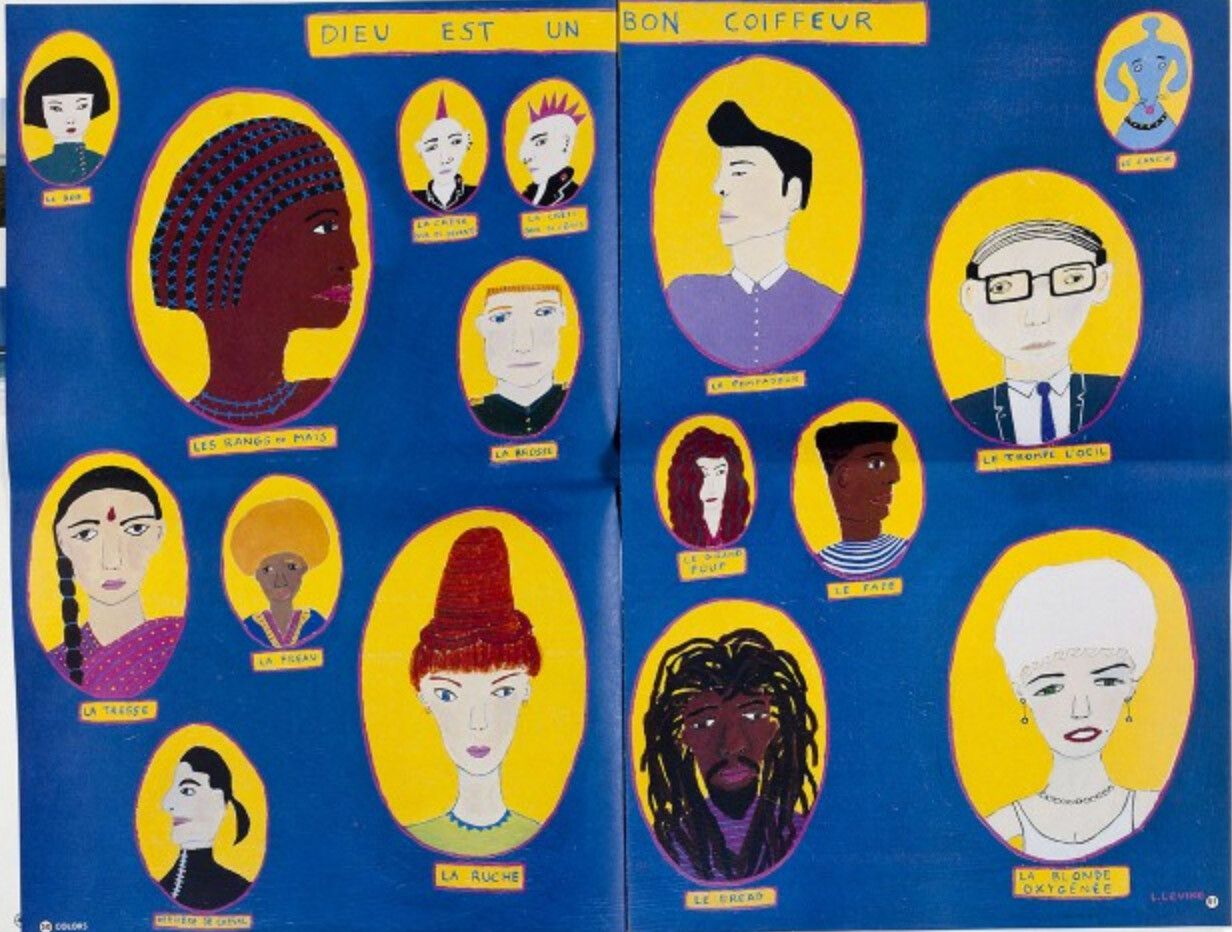

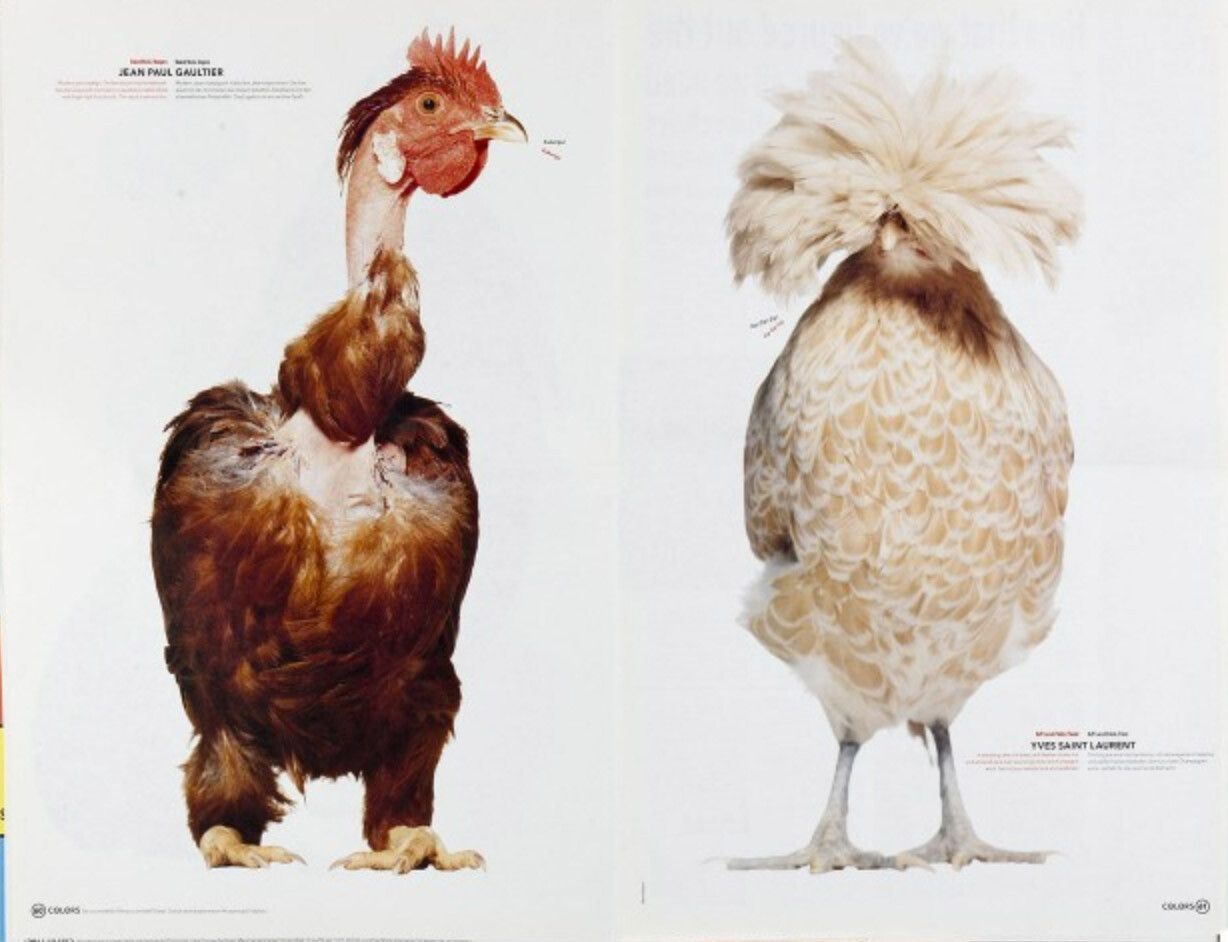

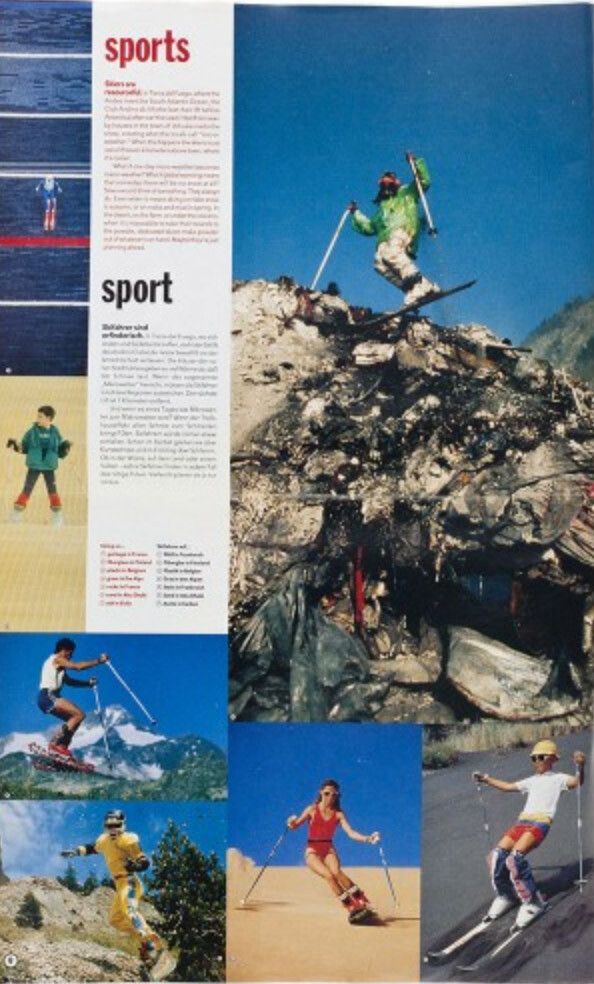

SS: It was a dialogue, yes. I remember working in Hong Kong, and he sent me the second issue of Colors magazine. The first issue was kind of crappy—I hadn’t seen it—but the second issue was the first big Colors magazine issue. It was fabulous, and I was so jealous. I thought, Oh my god, why am I wasting my time in Hong Kong when these guys in New York are doing such a brilliant thing? It must have been 1991 or [around then], and [Colors was] a revolutionary thing. I had never seen anything of that sort of quality. Two years later, Tibor offered, as a job, to come to M&Co, and at that point, I think, even run it. I of course jumped on that opportunity. I really felt that I needed to get out of Hong Kong.

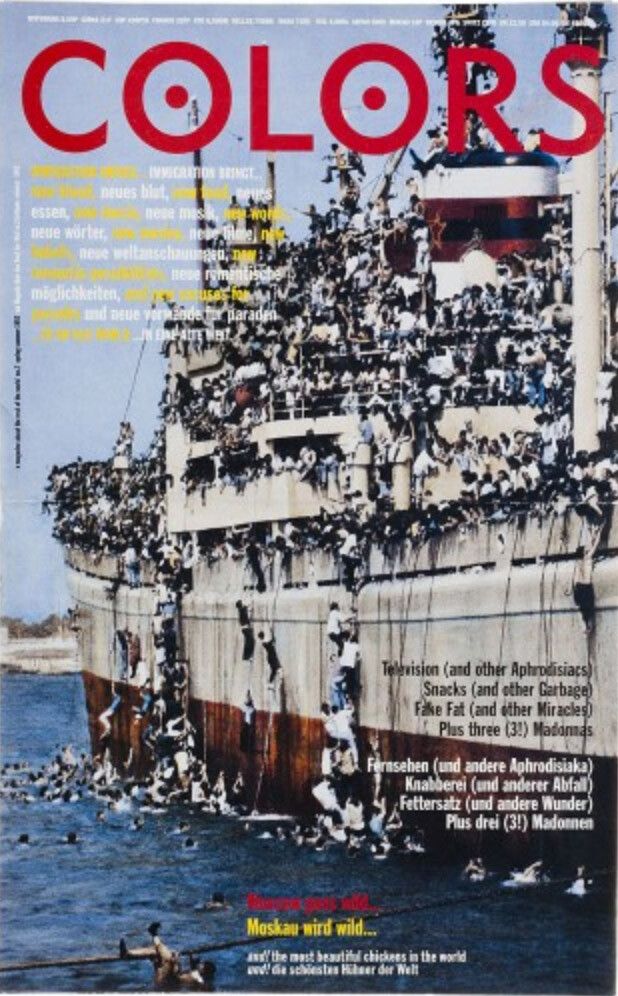

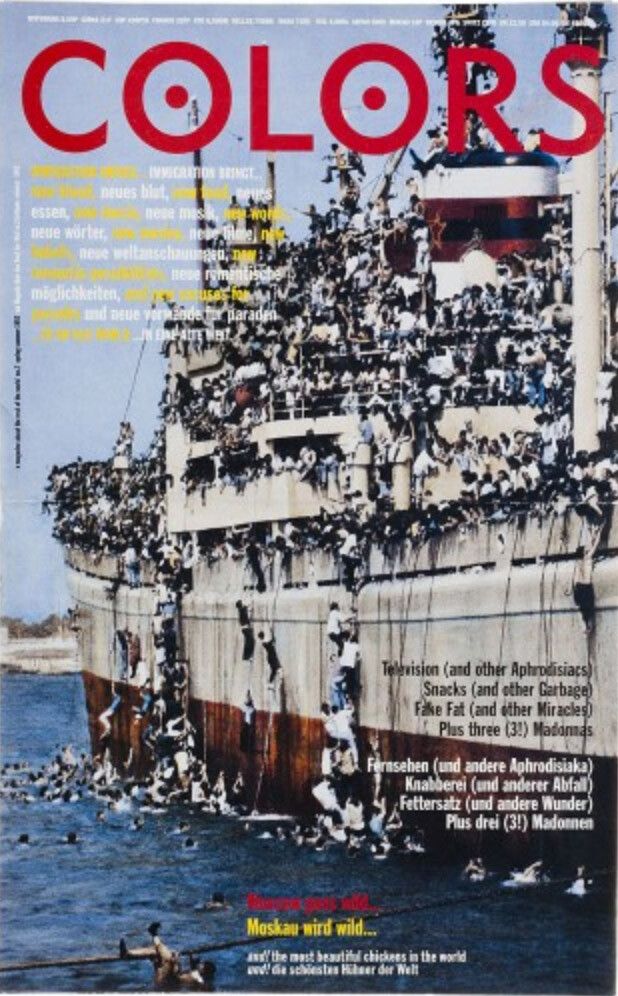

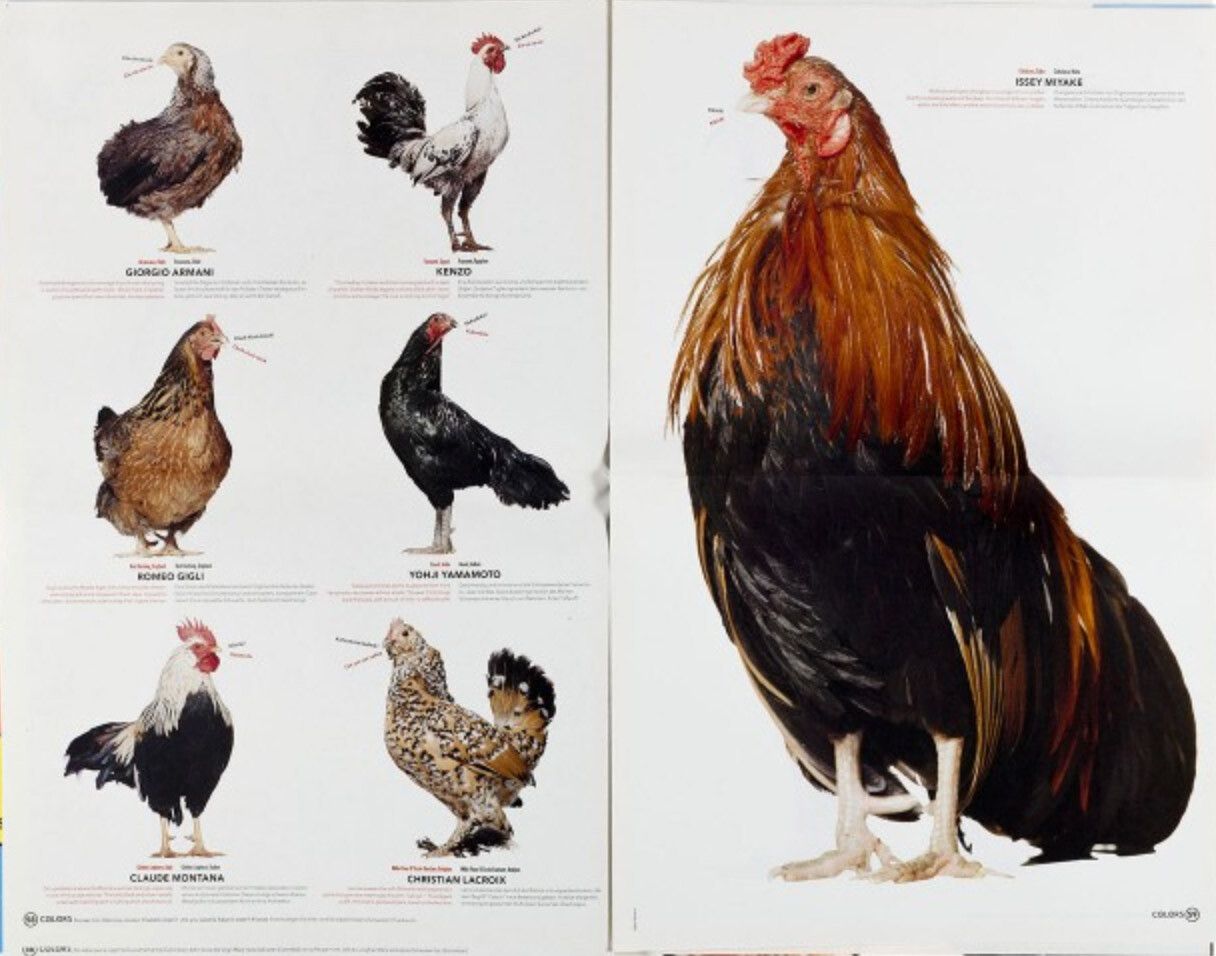

The cover of Colors magazine Issue No. 2, published in Jan. 1992. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

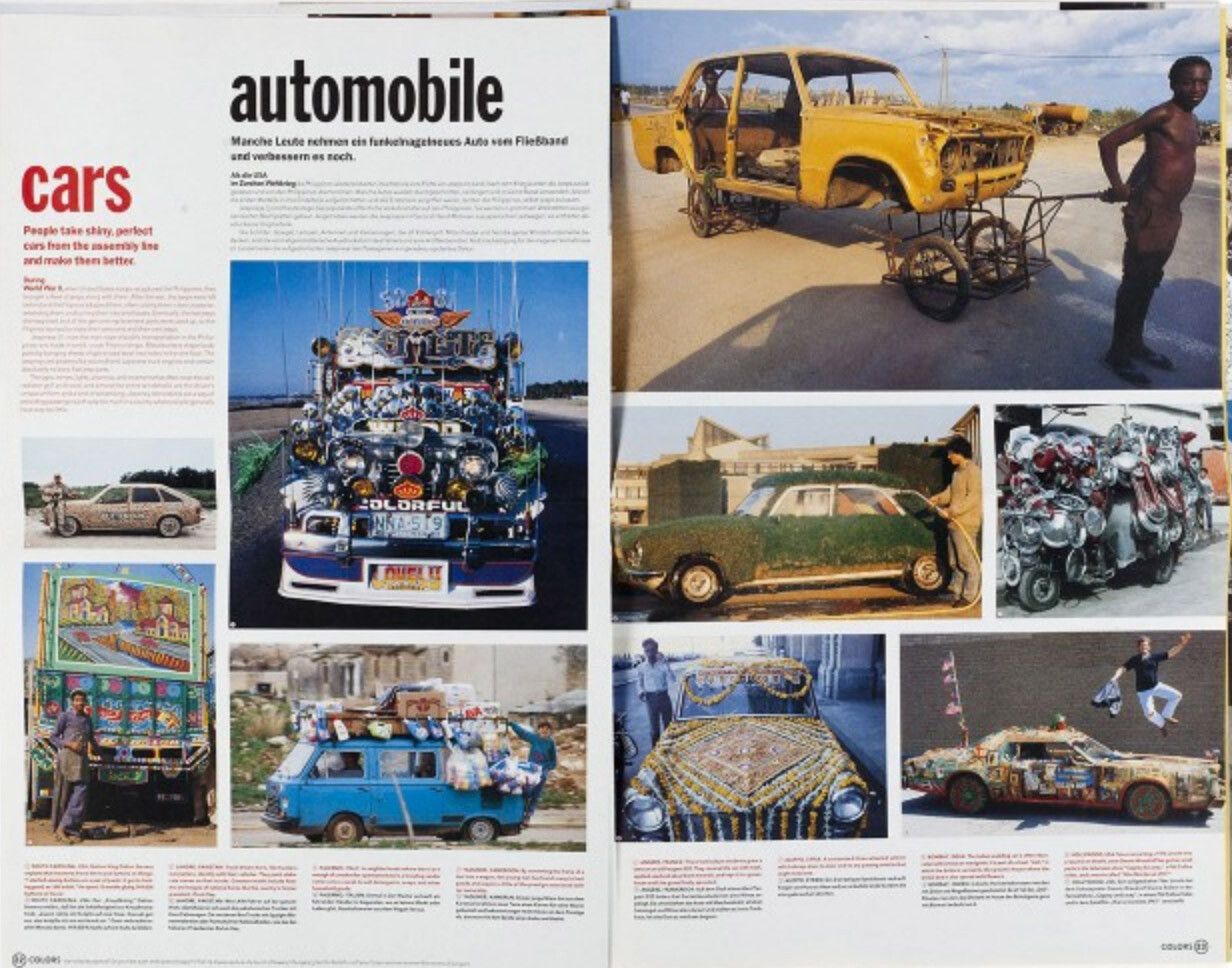

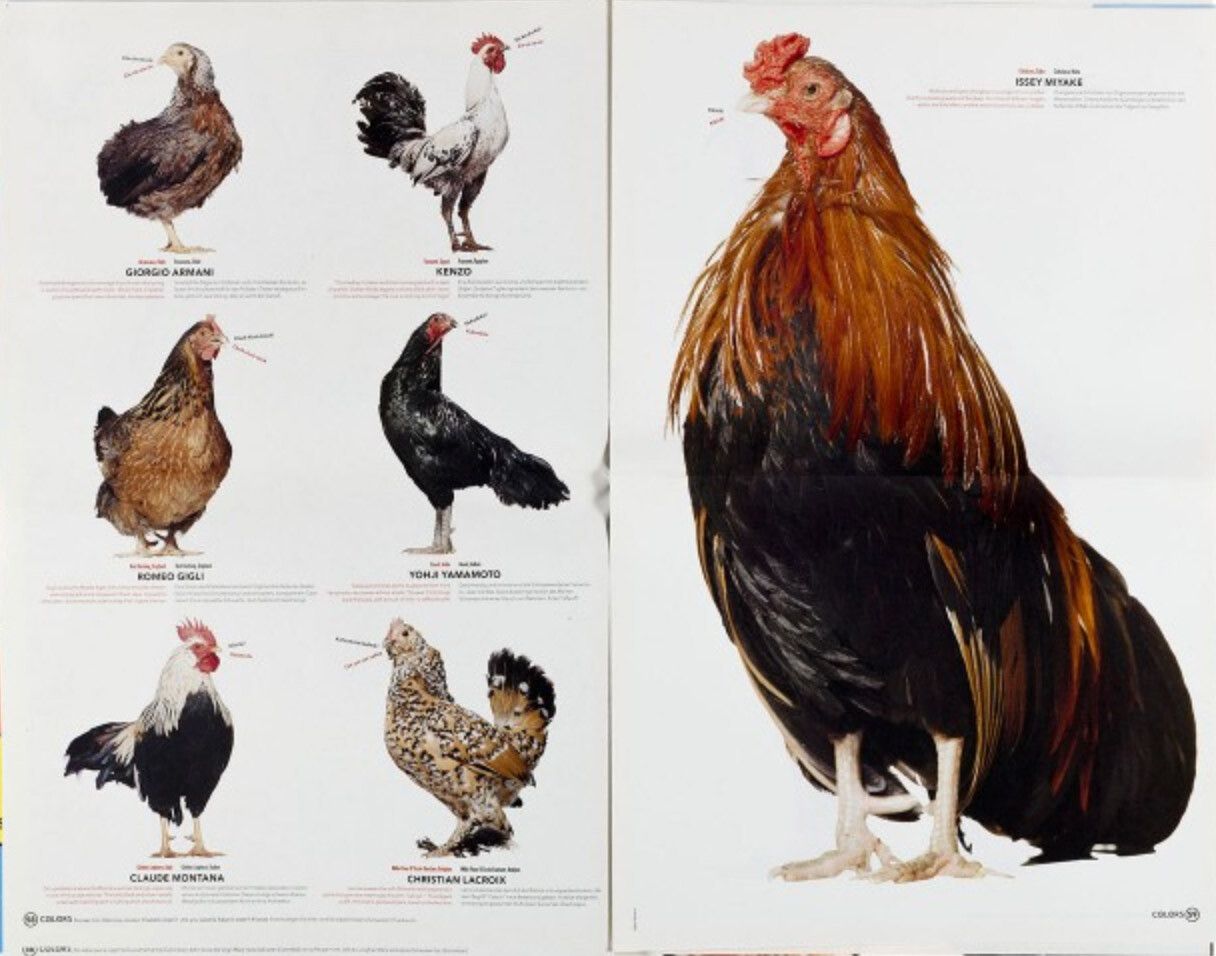

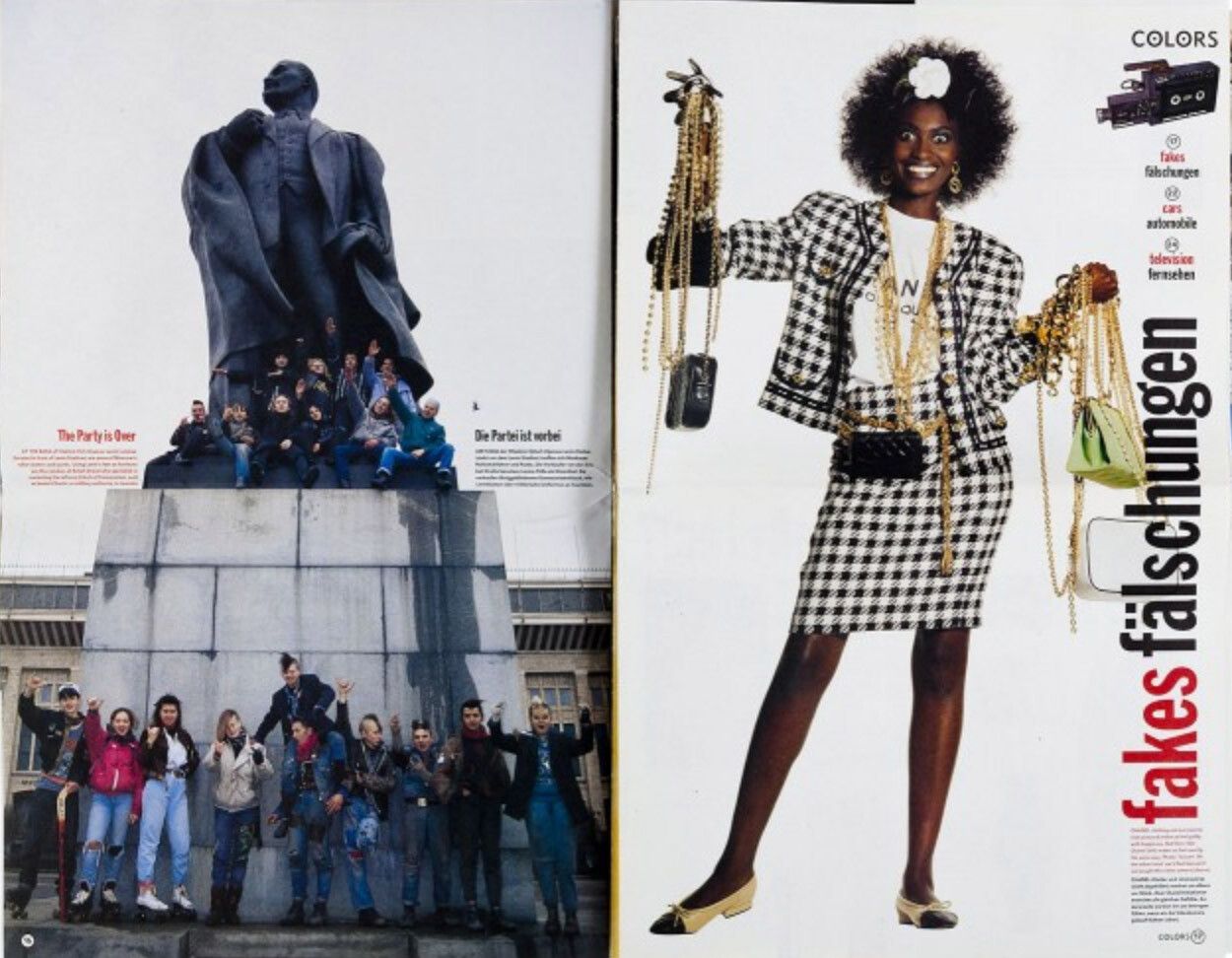

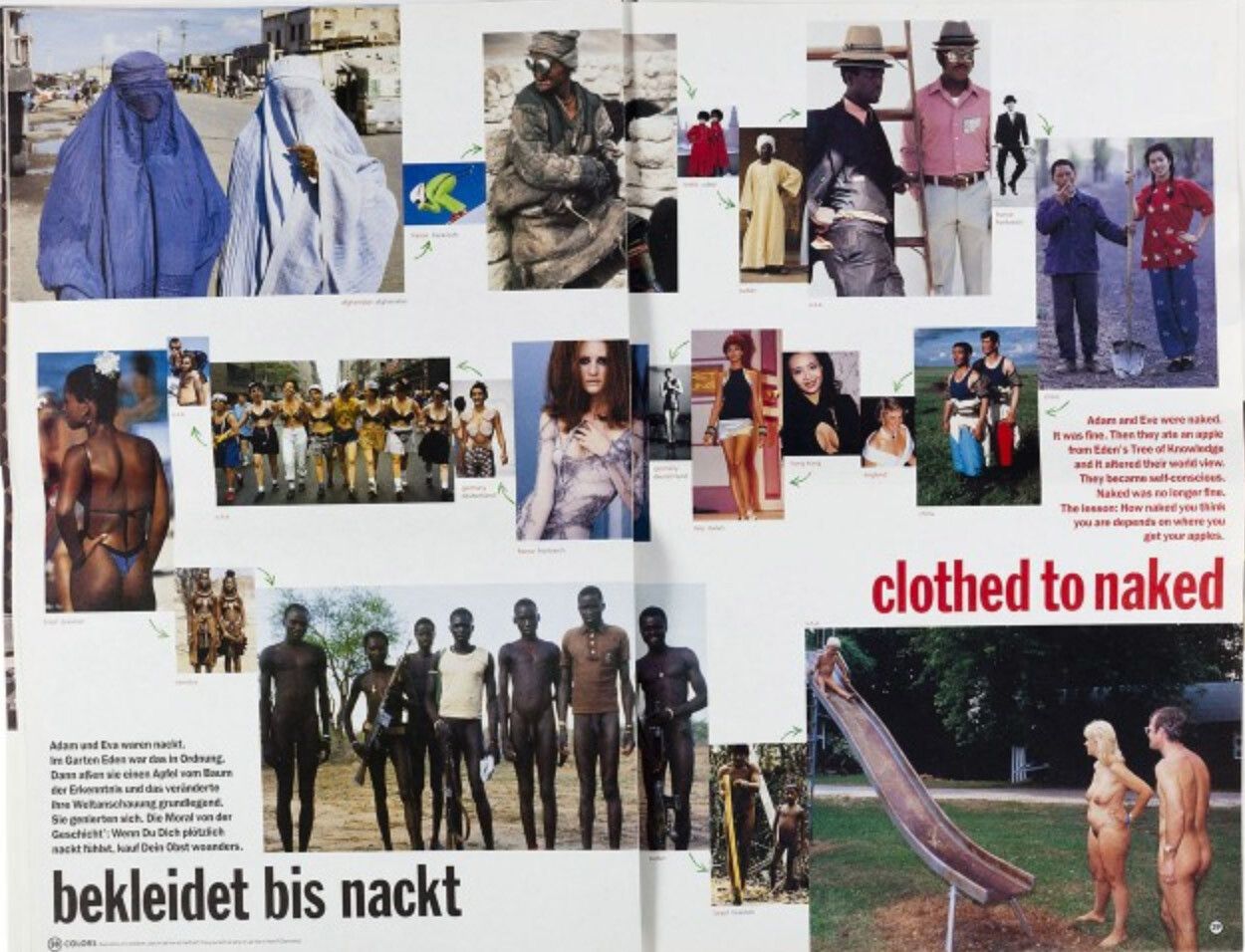

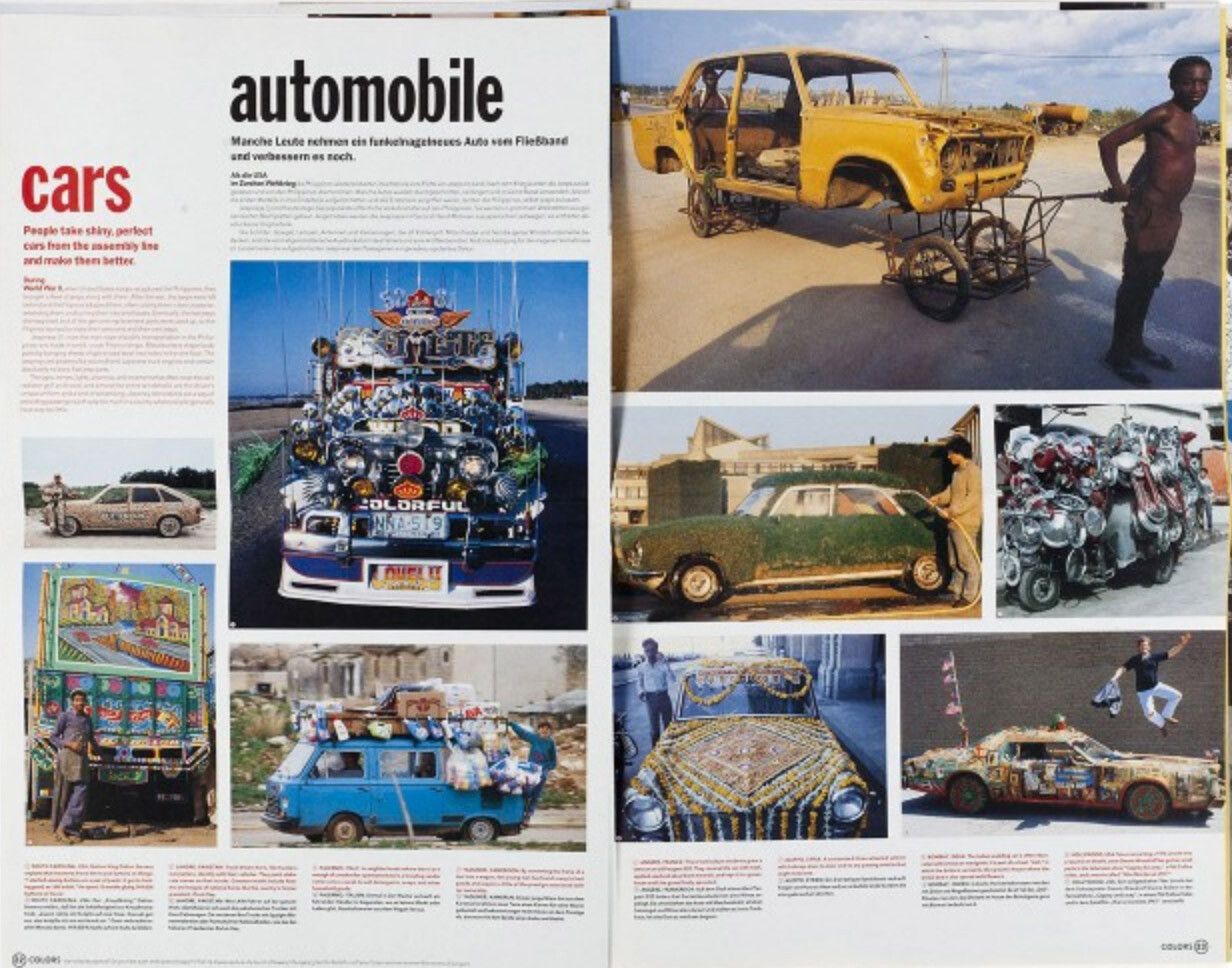

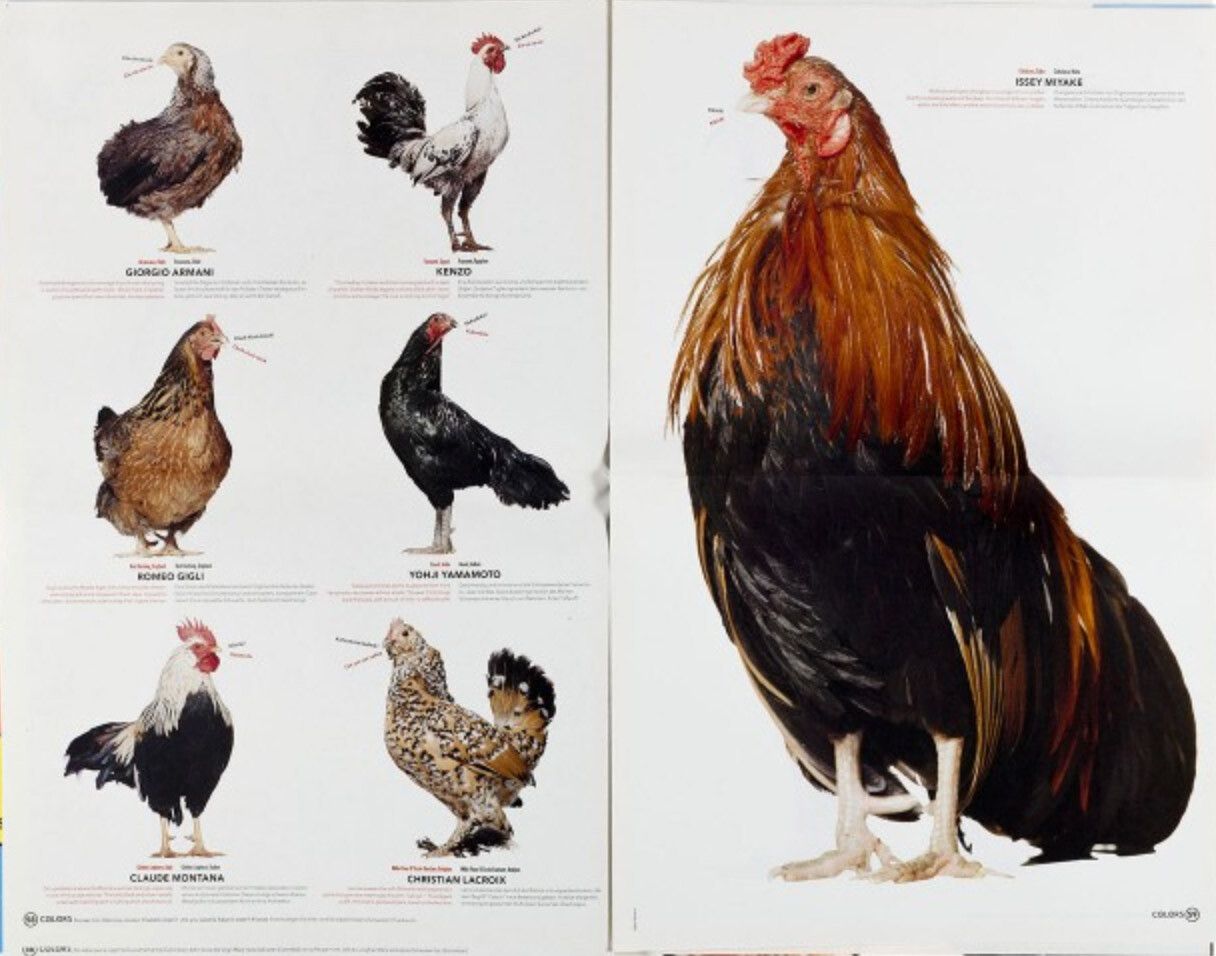

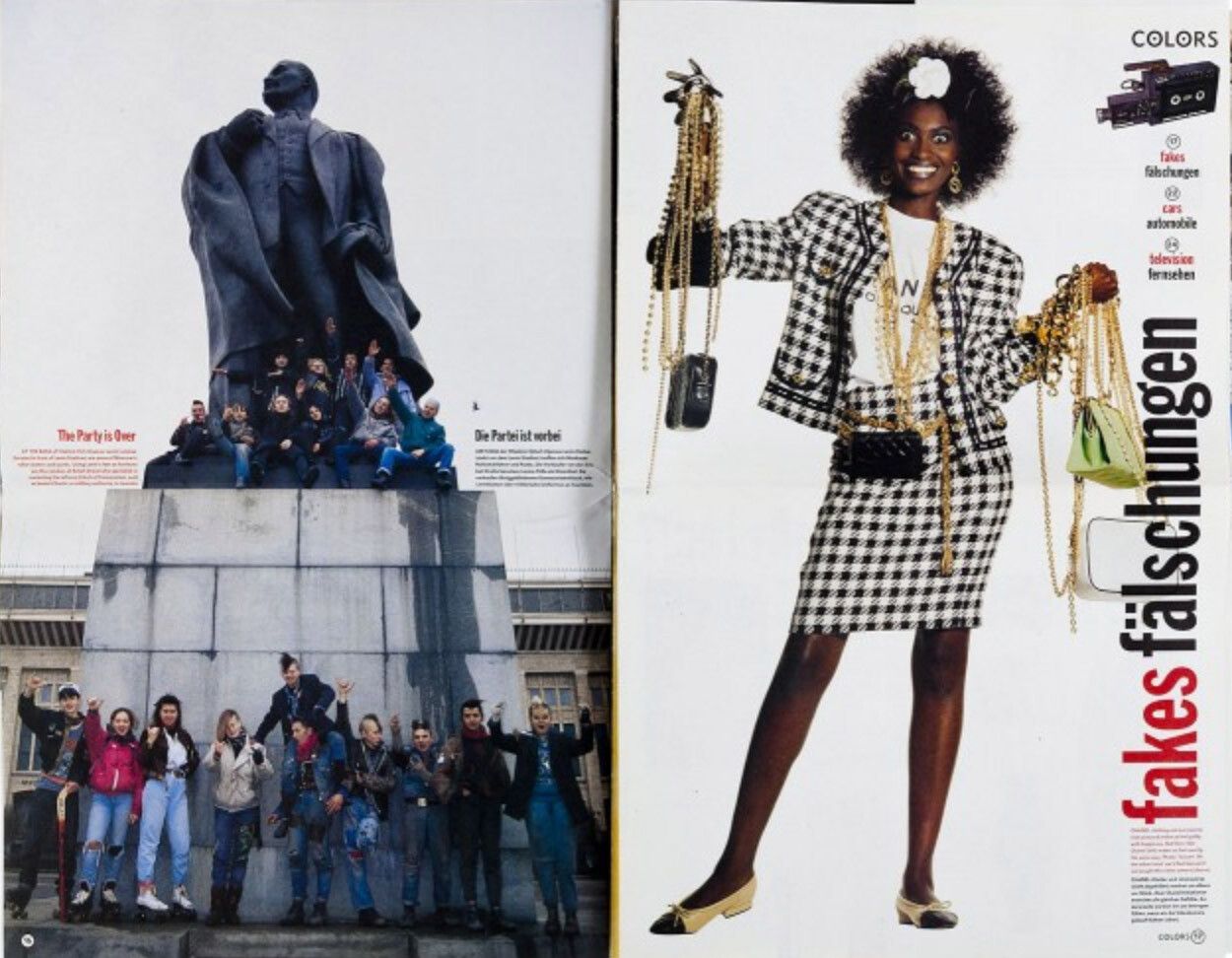

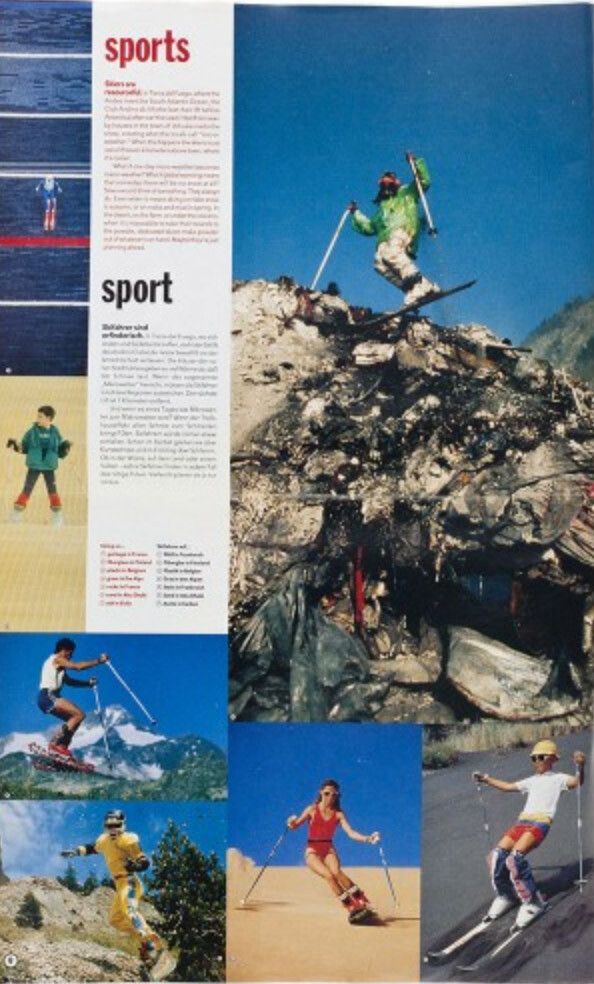

A spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

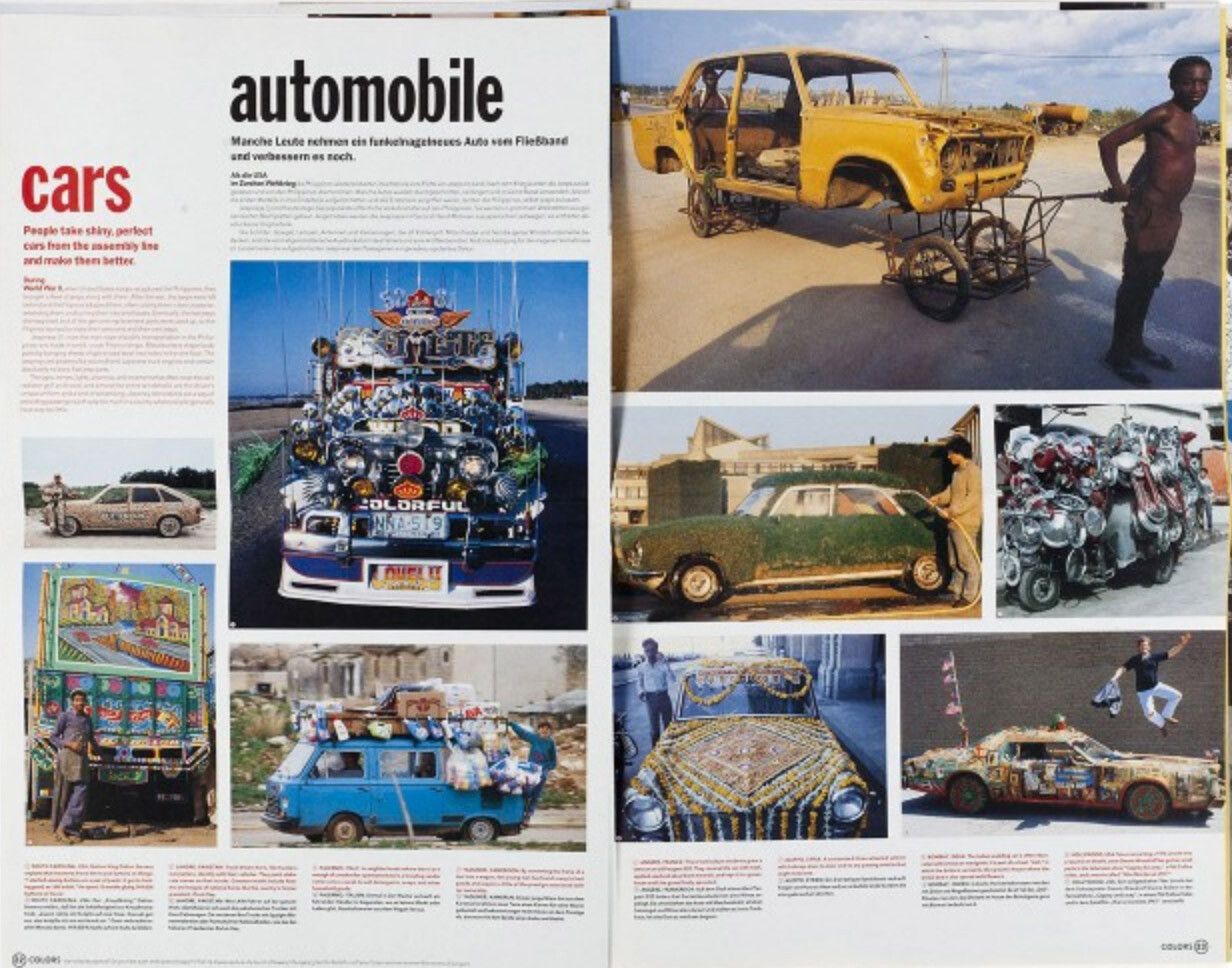

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

The cover of Colors magazine Issue No. 2, published in Jan. 1992. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

A spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

The cover of Colors magazine Issue No. 2, published in Jan. 1992. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

A spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

Another spread from Colors Issue No. 2. (Courtesy Colors Magazine)

SB: This was 1993, and within a few months of your returning to New York, Tibor decided to move to Rome, right?

SS: Yes.

SB: So that kind of left you thinking, Okay, I need to start my own thing?

SS: What really happened was, while he had offered to me to run M&Co, that never really happened. I never ran M&Co. I also think that he never told anyone else at M&Co that he had hired me to run it. I actually, at that point, had run a department of my own group in Hong Kong, so I wasn’t really ready to become a senior designer again. When he said that he was going to move to Rome and do Colors full-time, it was totally fine with me, because it basically meant I would have to open my own little thing.

“It felt like the right thing to do, a small company. Two, three, four people, low overhead. We wouldn’t need to take on a lot of corporate jobs; we could basically do design for the music world.”

I looked back at my time when I was sixteen, and why did I actually become what I became, a graphic designer? I thought, Well, now is really the time to go out and do what I set out to do, to create design for music, which at that time meant CD covers. We did a vinyl here and there, but it was mostly for the U.K. market only. But I had, at that thought, that warm feeling back in my belly. It felt like the right thing to do, a small company. Two, three, four people, low overhead. We wouldn’t need to take on a lot of corporate jobs; we could basically do design for the music world.

SB: You ran this out of your own apartment in New York for about fifteen years with a very specific rule that I found fascinating when it comes to your relationship to time, which was that arriving [at the office] around 9:30 or 10 and having a hard out at 7. And no weekend work. Can you talk about that in relationship to the work you were actually producing? What did that allow for the creative process, setting a limit on the time in which you could work?

SS: The time limit was a necessity because I was also living there. It was [sort of] separate, but I also didn’t want designers to be around after 7, and didn’t want this to be happening over the weekend. So those were the rules.

“Within design, almost any limitations are helpful as long as you know them in advance.”

I found that, within design, almost any limitations are helpful as long as you know them in advance. We knew every day that we have from 10-7 to do this thing, which meant that we were hardworking during the day. There was no looking through design magazines, or, you know, updating—well, at that time Instagram didn’t exist, but if it did, you knew that was not the kind of thing that you did during the day. You were busy because you had to be out of there by 7. But it also created, of course, an automatic proper balance between work time and play time. I think it’s healthy to have two days off during the weekend, where, yeah, you might think about something that comes to your mind—it’s not like you’re not allowed to think about [work]—but where you really are recharging. I know this from Hong Kong. In my time in Hong Kong, those two years, I worked extremely hard.

“I’ve now heard of many young designers—it seems to be particularly bad in the motion world—that feel that they are burned out in their late twenties, early thirties, and actually leave the profession. I think that’s awful.”

SB: Sixteen-hour days, I read.

SS: Yes. Including the weekend. I knew that if I allowed the work in my studio to go that way that I won’t be a designer by the time I’m thirty-five. I liked it too much for that to happen. I’ve now heard of many young designers—it seems to be particularly bad in the motion world—that feel that they are burned out in their late twenties, early thirties, and actually leave the profession. I think that’s awful.

SB: Yeah, because there’s no cadence or rhythm that they can go at that’s healthy. It’s completely stifling.

SS: In our studio, those rules are not really true anymore, because now that the studio has its own space, there is no really need to be done by 7. There’s no hard-out thing.

SB: There’s a livestream [on your website] now, though. [Laughs] So anyone can go on the website and watch your staff and see how late they work.

SS: You can check. I actually don’t, but if other people are interested in checking out how hard we are working, [or in checking] if there’s people around at 11 at night, they are of course welcome to. I still think that we are not, in the world of small or midsize design studios, among the bad ones [who overwork their staff].

SB: I want wrap the conversation with the idea of attention, because attention is one of those things that relates to time, and how do you capture other peoples’ attention. Ultimately, a lot of the work you’re doing—and have done—has, if not a sensationalist factor, a “wow.” There is an unexpected nature to your practice.

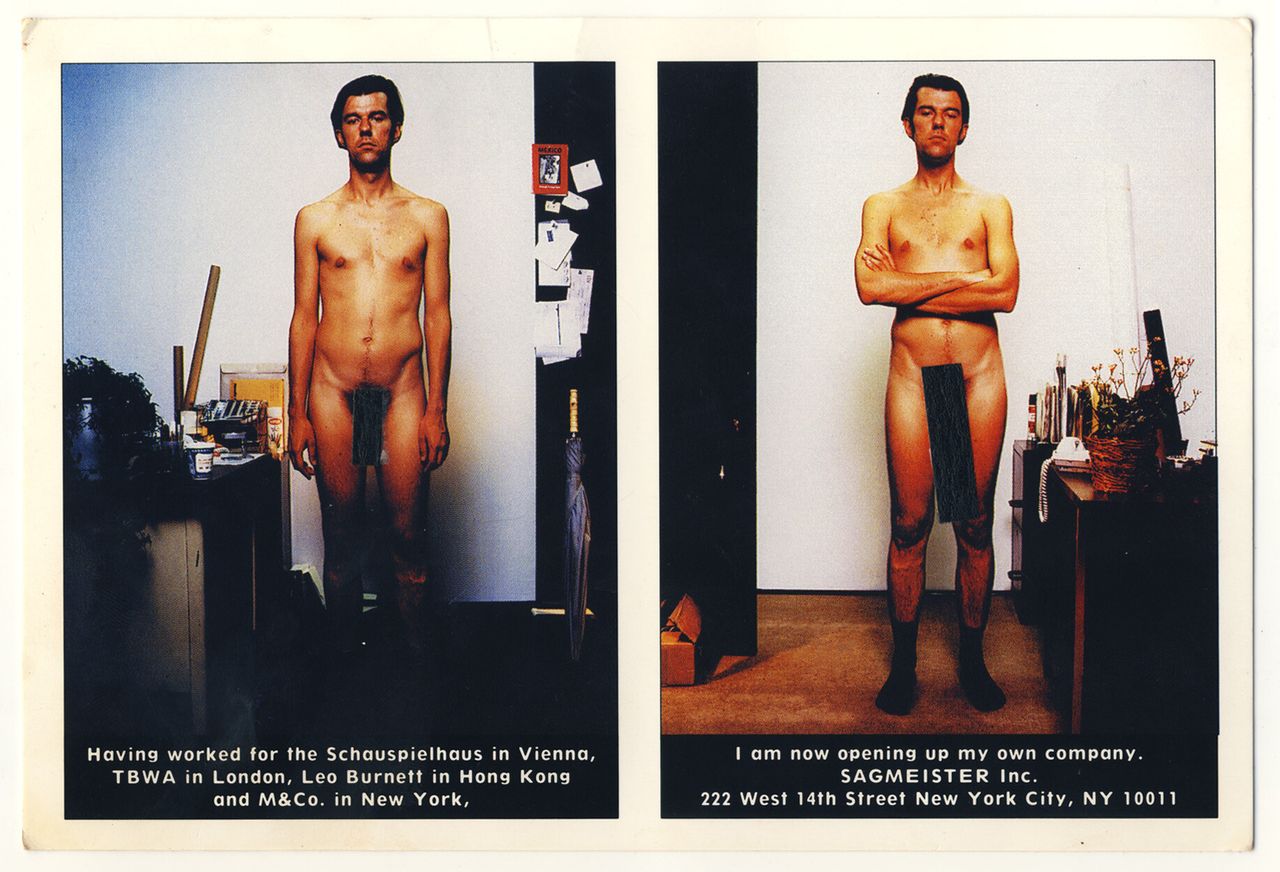

Maybe it’s best to talk about a couple of examples. The first one that comes to mind is that, when you launched your firm in 1993, you did so by putting out a naked photo of yourself into the world, announcing, “Hey, I’ve got this firm.” Then again in 2012, when Jessica joined the firm as a partner, you decided to repeat the practice with a series of photos of both of you naked. How did you conceive of that the first time? And how did you know that, even if it wasn’t necessarily the most professional thing to do, it was something that was going to draw attention and perhaps even, despite what impulses might tell you, the right attention to grow a successful firm out of?

A card announcing the 1993 launch of Sagmeister’s studio.

A photograph taken as part of the 2012 launch announcement of Sagmeister & Walsh.

SS: Well, the first one was one of those things where, I have to admit, I needed to overcome my own fear. The second one, not at all, zero. But the first one was. Because I remember, at the time, my girlfriend really thought that this was going to get the single client that I had to leave. She thought, Maybe you could do this shit in Europe, but not in the United States. This is just not done [here]. I went ahead with it anyway.

I remember going to my single client’s office three weeks later. He had a pretty empty office, but that card was actually pinned up on the wall. And there was a Post-it note on the card, where he had almost written to himself with this ballpoint pen something along the lines of “the only risk you can take is not taking any risks.” Something along those lines, pretty much validating my whole concept. And we got three follow-up clients from this one client. Pretty soon, a week or two later, we had four clients. It all worked almost immediately.

The photoshoot with Jessica was much later and, by that time, this was also not so new. It was kind of a joke on our own thing. I had originally suggested to Jessica that she would be dressed very conservatively, like in a long skirt with a conservative sweater, and I would be naked. And then she complained and said, “Why do I have to be the conservative one?” Of course, it wasn’t possible to have her naked and me not, so it meant that we both had to be.

SB: I think, in relationship to time, it’s interesting to look at those two photographs side by side. I’m sure you did that exercise—did anything pop into your head about, Wow, this is 1993 and this is 2012, basically twenty years time?

SS: Well, I used to be better-looking.

SB: [Laughs] You still look good at fifty-six, I think.

SS: Oh, well, thank you.

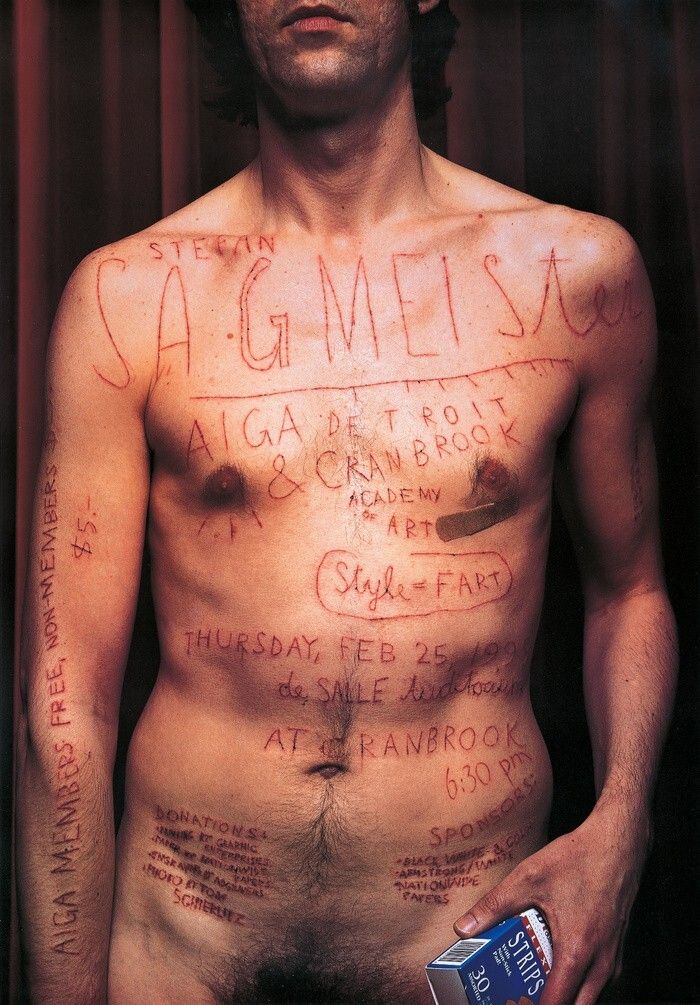

Sagmeister's torso, cut with an X-Acto Knife, for a 1999 AIGA Detroit poster.

SB: The other most well-known example of this [kind of “wow” project] would be the time you carved into yourself with an X-Acto knife for an AIGA Detroit poster in 1999. That, in relationship to time, is fascinating on multiple levels, because of how long it must have taken you to actually carve that thing; and then you have the consideration, of course, of pain; and how long it took for you to deal with the pain; and then the healing. Can you talk about that specific project? Why did you decide to go through with it? What was the relationship to time and that healing process like?

SS: At the time, the buzzword in design and in graphics was very much “process.” Tomato, a British design group, had done a book about it. People talked [a lot] about process—how do you do things? And, considering I was talking to other designers, and the poster was about that talk, it seemed like an interesting thing to do, to basically create a poster where the process of its making would be very clearly visible in the final poster.

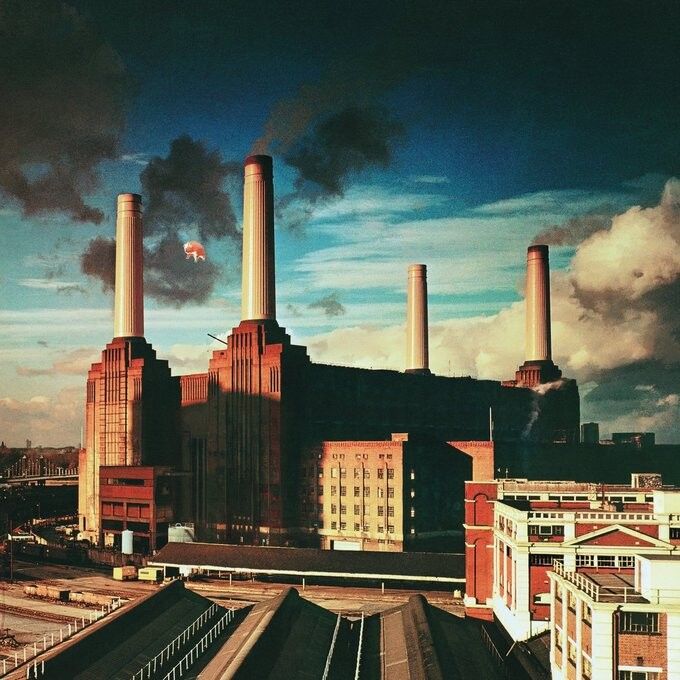

The way we went about this is our intern carved into me. It hurt much more than I had expected, because I had done a little test a couple of weeks earlier, which was doable. The test was a couple of scratches on my arm. To do the whole torso, just by the amount of typography, including sponsors and things, it was just a lot of type to be dealt with, which then turned out to be very painful. But by the time it became very painful, it was already three quarters of the way done. So the choice was just, basically, do we stop now, and I have to come up with a new idea, and I have half of my body ruined, or three quarters? Or do I just bite my tongue and we go through with it? Which seemed at the time to be the less painful strategy than to also come up with a new idea. We then shot it with an eight-by-ten camera that really showed every single pore. Photoshop was just in existence, but you could not have Photoshopped it. What you don’t really see in the reproductions of it—but you definitely saw in the real poster—was that this was done for real. It wouldn’t have been humanly possible to Photoshop something in that crazy of detail. In that sense, I think it’s in the traditions of projects that I have always very much admired, specifically Pink Floyd’s Animals, which had done the flying pig over the Battersea Power Station in London. I think there was some retouching going on, because they had their own sets of difficulties doing that, but ultimately, I had always admired projects that told the story of their making within the image.

The album cover for Pink Floyd’s 1977 album, Animals. (Photo: Courtesy Pink Floyd Music, Ltd.)

Only much later, I discovered that, of course, there was a group that was quite prominent when I was studying in Vienna, called the Viennese Actionists, who did a lot of work with blood and guts and slaughtering of animals. The most prominent people in that group would be [Rudolf] Schwarzkogler or Hermann Nitsch or Günter Brus. I was very aware of [them] as a student, but had forgotten about them, having been in the States and in Hong Kong for a long time. I’m sure that there was an influence there.

SB: How long did it take to heal?

SS: It actually didn’t take that long. I think it was roughly three or four months until it was all gone. I have good, fine-healing skin. But it did all come back when I tanned that summer on the beach as outright typographic outlines. Suddenly, I had typographic sponsors on my crotch. [Laughs] It’s debatable if that was that attractive.

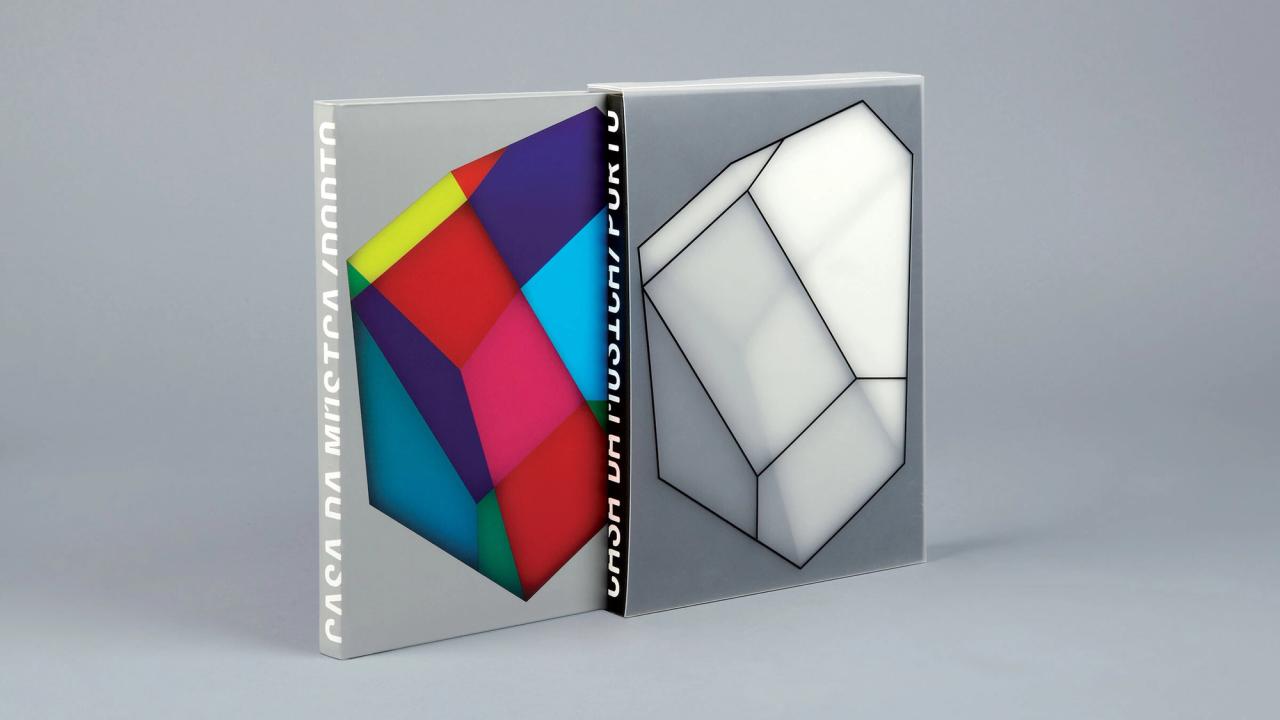

SB: You’ve cut yourself with an X-Acto knife; you’ve posed naked, twice; you’ve produced an incredible amount of work in the music industry [including album covers for David Byrne, Lou Reed, Pat Metheny, and others]; done identities, like the one for Casa da Música in Porto, Portugal; worked with brands like BMW. What’s next? Where do you want to go from here?

The identity for Casa da Música in Porto, Portugal, as seen on a book cover. (Courtesy Sagmeister & Walsh)

SS: Well, I think that I’m very happy with how the “Beauty” project is going. It’s a subject that I feel is important. I think I’m at the right stage in my life to promote a thing like this. It’s this mixture of—you need ideas to do it, but there also needs to be some sort of standing in the industry, or some sort of power, to sort of make that happen. I think that this is what I’m supposed to be doing. I’d be very happy to do some more, together with Jessica, in that world.

Right now, I’m working with changing the exhibition for Frankfurt. In Frankfurt, it’s a Richard Meier building, so it’s a completely different situation than the 19th-century fake Renaissance building in Vienna. And there are projects coming out of [the “Beauty” project], like work for a public-housing project in Vienna that’s, in the best sense of the word, a “beautification” project. We can see how the theories we promote in the show work in real life. I’m very interested in all of that. And I myself have to say I’m less interested in commercial work, and I’m very happy that Jessica is willing and able to take more of that on.

SB: You’re busy trying to make the world a more beautiful place.

SS: In an ideal way, yes. It’s not quite that, but if it would go down that route, yeah, that would make a lot of sense to me. I would find that meaningful in the actual meaning of the word.

SB: Well, Stefan, it’s been great. Thanks for joining us today.

SS: Thank you so much. Obviously, the listeners can’t see this, but we are actually in a gorgeous space. Definitely the most good-looking sound studio that I’ve been inside in ages. So thank you for making this happen, in such a gorgeous environment.

SB: Glad you could be here.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on Feb. 14, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by our director of strategy and operations, Emily Queen, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.