Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

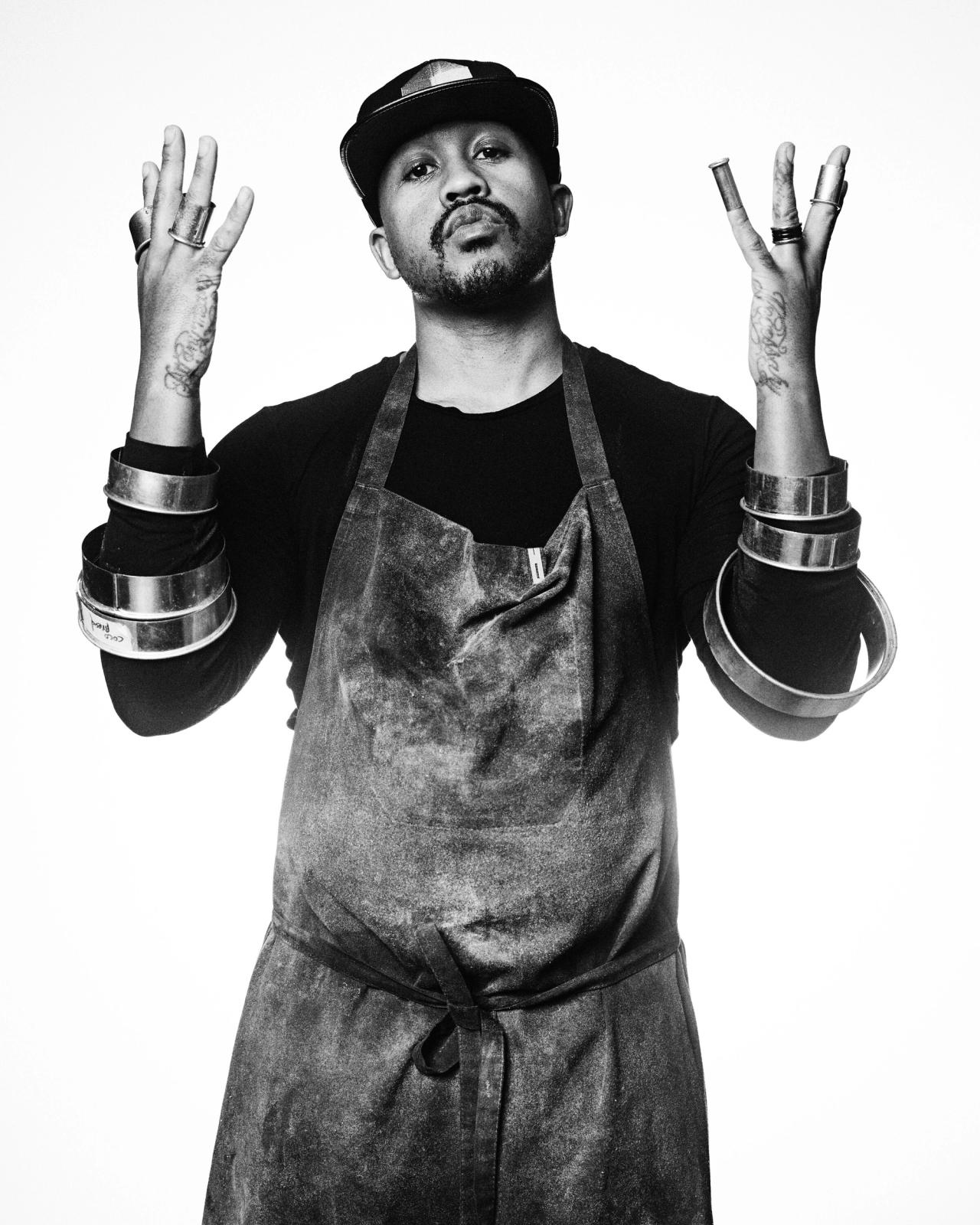

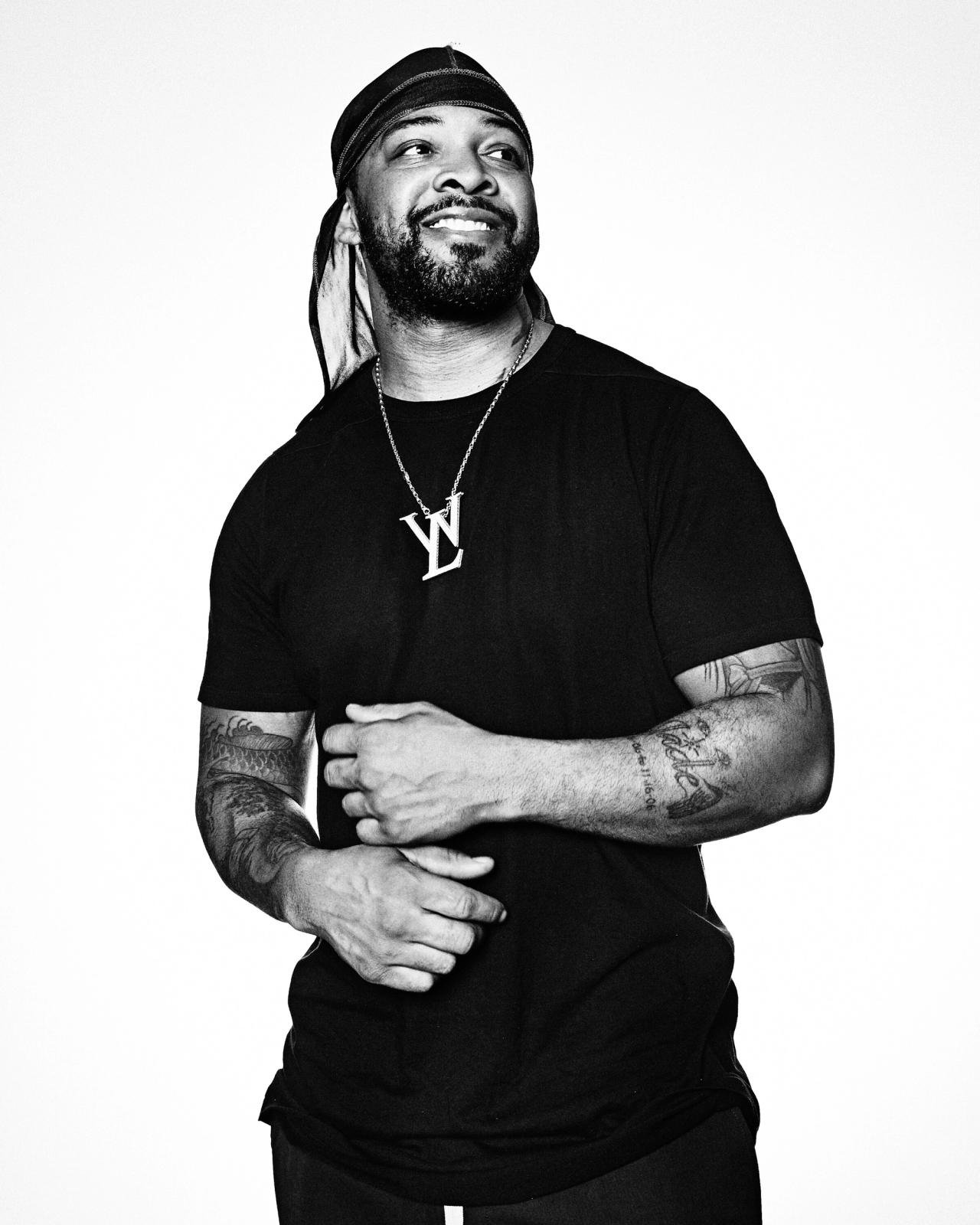

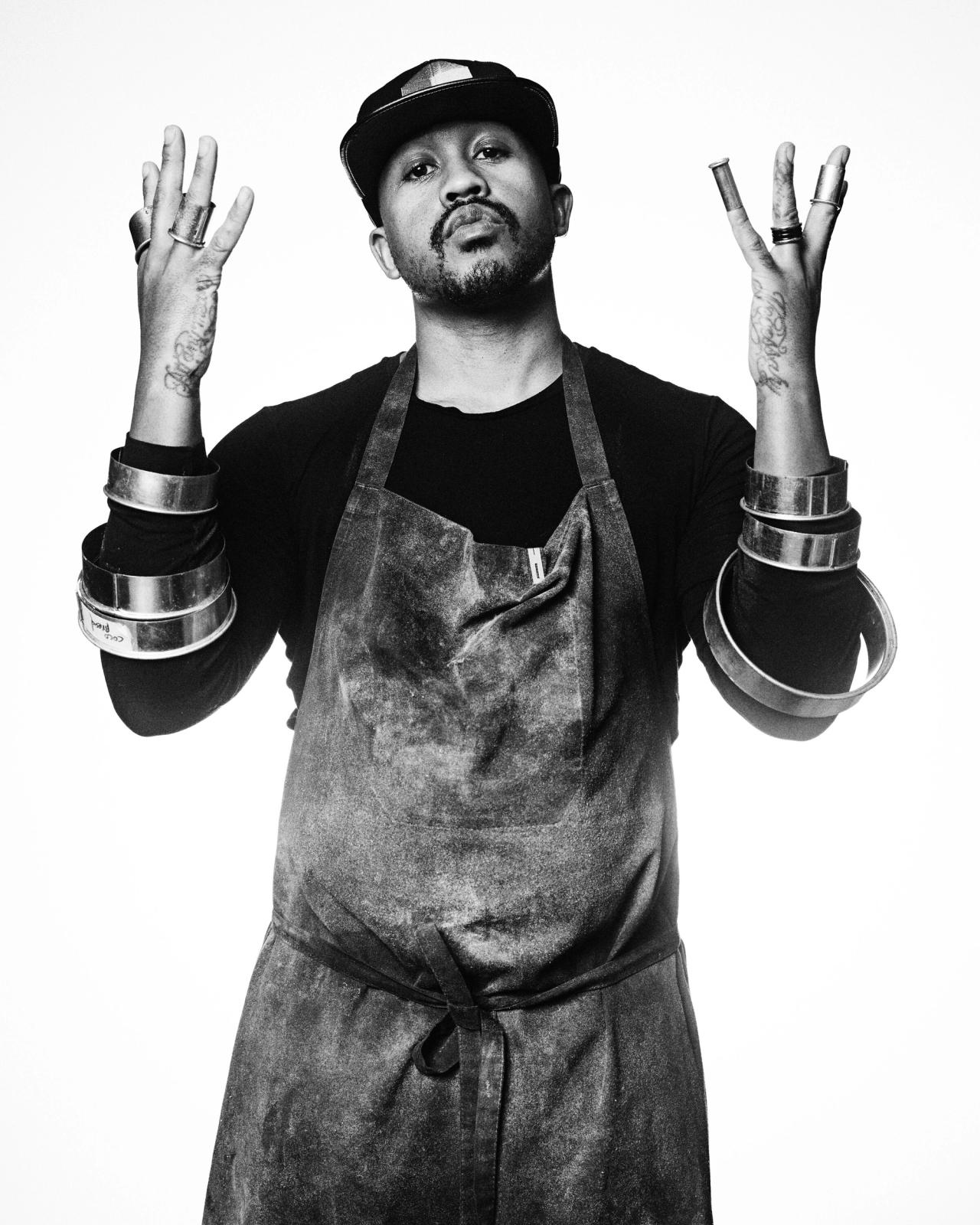

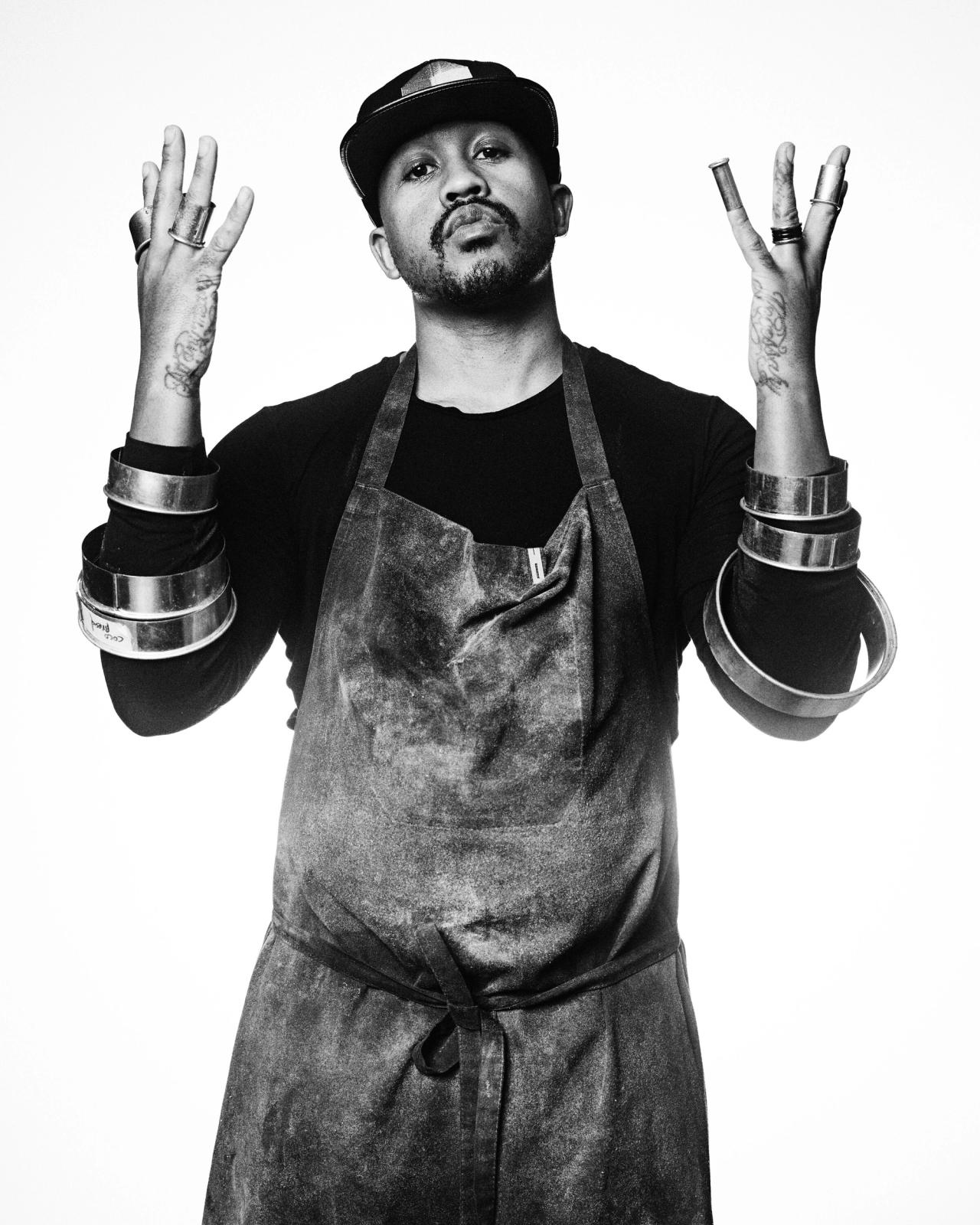

Jon Gray (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Spencer Bailey: Welcome, Jon.

Jon Gray: Spencer, thanks for having me.

SB: A lot of people now know of you, as well as this culinary outfit you’ve built, Ghetto Gastro. What a lot of people probably don’t know, though, is that you’re deeply embedded in the worlds of art, design, and architecture. Talk to me a little bit about that.

“Food was really just a good excuse for me to finesse my way into all of the worlds that I’m interested in.”

JG: Food was really just a good excuse for me to finesse my way into all of the worlds that I’m interested in. Being the ones that you just mentioned. I think it was just showing up. I feel like ninety-nine percent of the game is showing up. If I’m interested in something, I’m going to pull up to the function.

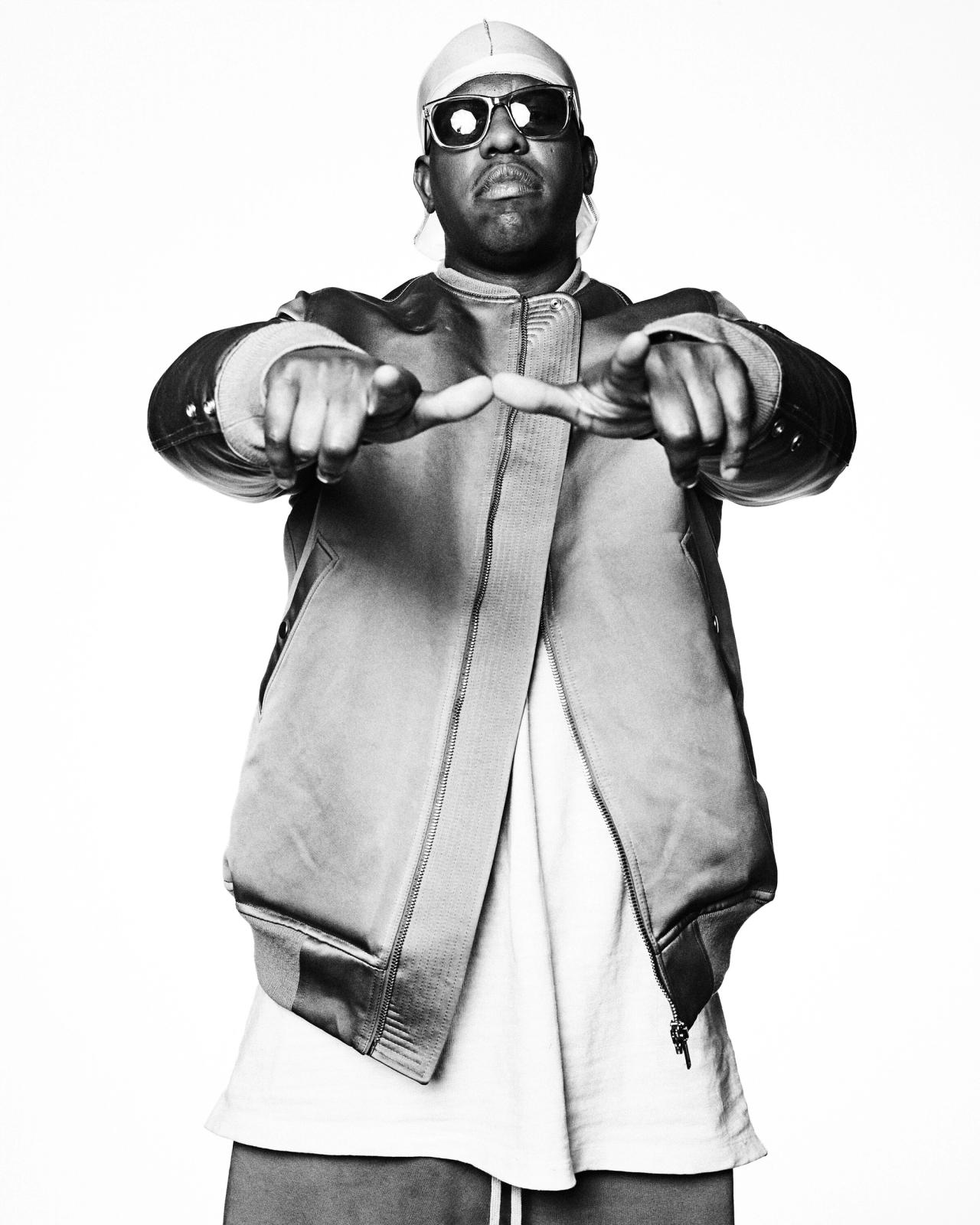

Design Miami—that’s where it started. A good friend of mine, Todd [Merrill], he told me, “You need to come down here.” He was showing at Design Miami in 2007 or ’08, and I went.

Outside of the Design Miami fair in 2008, which Gray attended. (Photo: James Harris)

I’ve always thought about design in terms of wanting to design the world around me, whether it was, like, you think about a house, interiors, urban planning—I’ve always thought about it in that sense. Or, actually, going to these gatherings, where it’s a lot of the so-called “world’s best designers.” I just like design thinking. I like how designers think. I’ve always wanted to surround myself with those types of people.

SB: Along the way, you’ve become friends with many of them, like David Adjaye or Kunlé Adeyemi.

JG: I consider those gentlemen family. David’s like a brother. He’s always in the background, kind of letting me know how to play, how to move, what to look at. And he doesn’t have to use a lot of words. Which is amazing. David introduced me to Kunlé. We’re cooking up some stuff right now.

SB: How have you navigated this world [of art, design, and architecture], which is obviously quite a stark contrast from the Bronx?

JG: I think the connective tissue is really just people who are curious and love life. A lot of times, it’s not good to judge, but if people care about where they’re eating and are considering those choices, usually they’re interesting and curious. It’s not just food as function; it’s like, This is a moment to gather, to have conversations, to enjoy and make a memory.

SB: Connected to design, you have this fashion background. You went to [classes at] the Fashion Institute of Technology and ran a small denim company for a while.

JG: Yeah, I was a partner at a denim company [Mottainai] with my buddies Luke [McCann] and Rob [Lindo]. They were actual students at FIT; I signed up for night classes and really just went for the library, and to stay out of jail, to show the judge and the D.A. that I was trying to be an upstanding citizen.

I think, when it comes to [design] objects, the first platform was definitely garments and thinking about construction, and seeing this start as an idea in my head and become something tangible.

SB: Tell me a little bit more about the denim company. How did that come about?

JG: My friend Keoka [Lancaster], who was going to FIT, she was studying menswear. And the menswear program was super competitive—they might have only accepted 20 students, maybe less than that, per year. She was in the program with Luke and Rob. And then I also got connected to Luke because he was selling T-shirts at my brother’s shop—like my “brother” as in soul brother, not biological one—on First Avenue, next to Patsy’s. It was called Everything Must Go. It was ahead of its time. Imagine Supreme in Harlem, like skate decks, trucks, really cool T-shirts, cool sneakers.

“I like to be a trojan horse, and for people to have some stereotype or perceived notion when they see me and for me to be more than what they might perceive. I’m sure I’m a lot of the things that they think, but that’s just scratching the surface.”

I was like, “I’m going to FIT—I need to connect with these cats.” And once we linked up, we had a lot of shared experiences and views. They were just killing it, and we were both into sustainability and how that could relate to apparel. We were doing the natural indigo dye, using the Kuroki denim out of Japan. I think we were one of the first small American brands that was able to access that fabric, besides maybe Double RL.

We were making jeans here in New York; we were getting ridiculous Italian trims. Whatever was the most expensive shit we could get, we tried to get it. I couldn’t afford a pair of the jeans we were making at the time. But we had some great accounts: Bergdorf Goodman, Harvey Nichols. It was funny, sometimes going to these stores to either train staff or see how everything was merchandised, people were like, “Oh, the messenger entrance is that way.” It was always a mindfuck.

SB: Wow. I’m sure navigating that experience probably impacted how you thought about some of these other “white worlds” you were—

JG: Yeah, well, it was always super-interesting. I’ve always liked the element of surprise. You know, I like to be a trojan horse, and for people to have some stereotype or perceived notion when they see me and [for me] to be more than what they might perceive. I’m sure I’m a lot of the things that they think, but that’s just scratching the surface.

Architect David Adjaye (left), artist Lynette Yadom-Boayke (middle), and Gray participating in the Serpentine Galleries’ Work Marathon at London’s Royal Geographical Society in fall 2018. (Photo: Plastiques Photography)

SB: We talked a little bit about design. You’re involved in the world of art, too, whether it’s doing a collaboration dinner during Art Basel or a talk with the Serpentine Galleries in London.

JG: Shoutout to Hans Ulrich [Obrist], Yana [Peel], Klaus, Amal [Khalaf], the whole Serpentine crew if I forgot you, sending big love.

Yeah, and Hans and Klaus had me do this thing called the Brutally Early Club.

SB: Klaus Biesenbach.

JG: Yeah, Biesenbach. During Frieze, we were waking up at seven a.m. to do these lectures. It was fun, though, it was a good exercise. The Germanic people are funny, man. They love waking up early or not sleeping.

SB: Did you have any roots in art?

JG: My mother always took me to museums as a kid. It’s funny, a lot of times you don’t understand why you’re interested in what you’re interested in. Especially if it starts young and maybe drops off.

I’ve always been interested in aesthetics and space-making and wanting to use my hands and make things and build these worlds. My mother’s like, “Yeah, we used to hang out at the MoMA.” She worked on Fifth Avenue as a hairdresser, and on her off days we would go to the MoMA, go to The Met, kick it, go eat food. A lot of my interests trickled down from my mother, and also from my aunt.

The cover of Richard Wright’s Native Son. (Courtesy HarperCollins Publishers)

There was this thing called the African Art Fair that used to happen in Chinatown. I remember being a kid, going to these art fairs with them. I also remember there were people selling black art, almost like Mary Kay, where they would come to the house and do a workshop for people. It was network marketing, but for art. So people would come through and talk about why art is a good investment, and also go to my grandmother’s house. My grandfather passed the Sunday before Thanksgiving [last year], but going to my grandmother’s house, and looking at what they had all the walls, I’m like, “Oh, I’ve just been surrounded.” I’ve never thought about it or recognized it.

SB: The aesthetic cues were just there.

JG: Yeah, and I’m like, “Oh, this painting is older than me.” And the Black Power stuff. A lot of this art was representational of the black aesthetic, Black Power, black liberation. I’m like, “Oh, so this is why I was reading Assata and Native Son in fifth and sixth grade.” It kind of explains my perspectives.

SB: I want to go back to your childhood in the Bronx. Your family is four generations deep in the borough. And you grew up in Section Five of Co-Op City, which most people don’t realize is, like, forty thousand people.

JG: Damn, there are that many people in Co-Op? Shit.

SB: It’s the largest housing development in the United States. I want to know your memory, your perspective, of that experience, growing up around that many people, and the impact of the environment you were in.

Co-Op City in the Bronx. (Source: David L. Roush/Wikimedia Commons)

JG: My mother, she’s from the West Bronx—they now call it the West Bronx after the Cross Bronx Expressway split the different parts of the South Bronx. My grandmother was actually born in Jersey City. My great grandmother moved to Harlem from Pittsburgh when she was eighteen, to be a nurse and dietician. My great grandfather came here by way of Chicago. He was in Chicago first, born in Texas. They linked, had my grandmother. My grandmother was the firstborn. They had three daughters. She was born in Jersey City, but moved to the Bronx when she was two. My great grandfather was really heavy in the community, especially when it came to community development and real estate. He was a treasurer for this organization called the Bronx Shepherds, which did low-income housing through the church. He has a block named after him in the Bronx.

From left, Gray’s aunt and godmother, Sheila Everett; his grandmother Ursula Jones Conway; his mother, Denise Lee; his great grandfather John Arthur Jones; his great grandmother Helen Jones; and a cousin from Pittsburgh.

I say all that to say this: I bounced around. I was born in the Bronx at Our Lady of Mercy [hospital]. I lived in Yonkers, maybe until I was one, and then my mom left my pops. We lived with my grandmother in the West Bronx, maybe for a year, and then my mom moved to East Harlem. I started in East Harlem, at One Hundredth Street between First and Second. I went to school at CPE2, and I say this because this was one of those weird alternative-curriculum schools, where we did art and cooked food, like, every class; where we made food before we even picked up books. That was my kindergarten and first grade experience.

I moved to Co-Op City when I was in second grade. I grew up there. Section Five was what some people would call one of the more “textured” parts of Co-Op City. It was interesting because it was mixed. There were a lot of Jewish people that lived in the first iteration of Co-Op City, when it was built in the seventies, and [they were] upper middle class or just middle class—but if you’re growing up in an urban environment, you might consider it upper middle class, because they maybe have two cars and two parents in the household. After the eighties, when I was born, the war on drugs, the gang violence, and all that stuff trickled in.

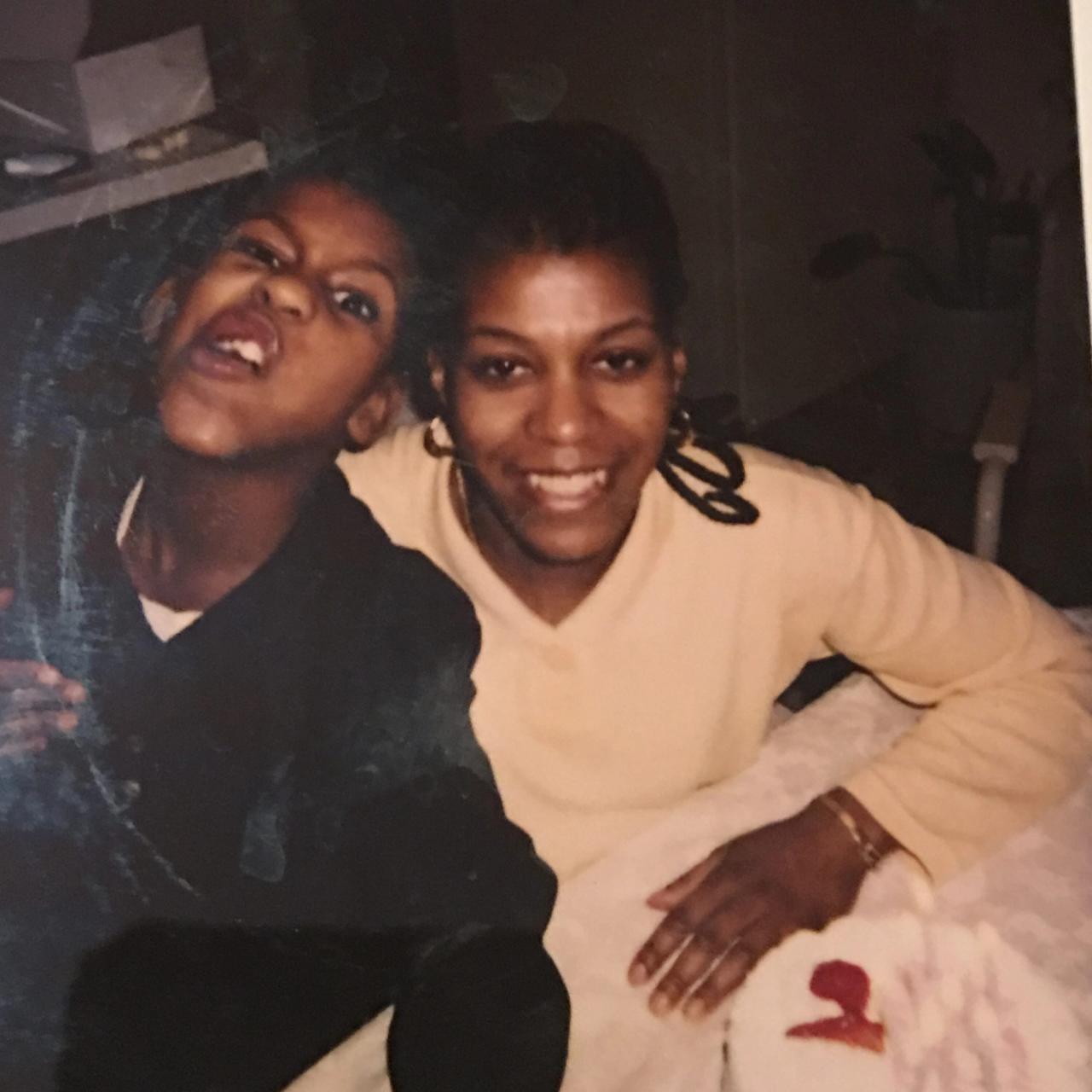

Gray with his mother.

Shit goes down. Someone got killed in front of my building a week ago. I came home from a Travis Scott concert, and there was police tape and a whole bunch of—

SB: I assume that [drugs, gangs, and violence] were impossible for you to avoid as a kid, growing up in that environment.

JG: I kind of chose not to avoid it. Like, I definitely could have avoided it. I have a cousin who was on a track [to success], and my mother tried to put me on this track. He was a Prep for Prep kid, went to St. Bernard’s [for kindergarten through eighth grade], Riverdale Country Day [for high school], Harvard for undergrad, and then Harvard for his M.D., to be a doctor, and then he did his residency. We had similar upbringings, but I struggled with following rules in school. I loved being social. I would finish the work, or I would find the work uninteresting—but I always finished the work. I always did good when I did work or showed up. I just liked to socialize. They considered that bad behavior, but these are the skills that allowed me to be where I am today. People try to truncate those parts of you and fit you in a box.

SB: So you ended up in that world. Talk about that.

“I gravitated toward the streets just to get money.”

JG: [Laughs] I can remember like it was yesterday. My grandmother lived on the same floor as me. She lived in Co-Op first, and my mother applied. We got an apartment literally on the same floor in the same building. So my grandmother lived down the hall from me. And she was a teacher at my elementary school. It was bugged out, because I was not the best-behaved student. But my grandmother worked in a school and was known as being a really great teacher—but very stern—and then, in junior high, when I got kicked out of one of the private schools I was going to, I ended up at the school that my grandmother worked at. I was raising hell—they called her every day.

I gravitated toward the streets just to get money. I had working papers, I had older brothers who were in Massachusetts doing the same thing. We have different mothers, same father. Their mother moved them to Massachusetts, to try to give them a better life, but they ended up tearing shit up over there, like really running shit on the streets. I remember, one summer, it kind of all trickled down. My brother came and picked me up, I went out there to Boston—well, Brockton, Mass.—for, like, two weeks, and just saw him dipping and dodging. I saw the commerce.

At that time, I still had hoop dreams. I wanted to play basketball and do all these things, and when mixtapes were out I thought I could go to the League. But I remember coming back, and my homies—all my friends—were two to three years older than me, and they were smoking weed. I was the square athlete that would walk around with a baseball and a baseball glove and throw the ball off the wall and do catching drills with it.

Gray, age 15, with “my lil homie” aboard a cruise. “I was high as hell,” Gray says of this picture, “rocking the [Marithé + François] Girbaud and durag sturdy.”

I remember when my mother told me that she tried drugs when she was a kid. A stay-away-from-drugs commercial came on the TV, and I remember asking my mother, “Did you ever smoke weed?” When she said yeah, I remember I was devastated. I was, like, thirteen or fourteen at the time. Fast forward to fifteen: I go away for that summer. It’s between ninth and tenth grades. I come back, I steal a bunch of weed from my brother, I start smoking with the homies that summer.

I remember asking my mother for some money, and my mother said no. Then I asked my grandmother for some paper, and she said no—and it was something small, like five dollars. It was like, All right, [I need to] get a job.

In Co-Op City, there’s a mall called Bay Plaza. I literally applied to every job there. And I went to catholic school, so I knew how to put it on—I knew how to throw on khakis, tie a tie, put on a shirt. I’ve always been a polite guy, and articulate, so I could do that thing. I remember just going to each and every spot, and they were like, “No, we can’t hire you, you don’t have any experience.” It was literally to do stock, or to wash dishes at Applebee’s, or be a waiter. How was I supposed to get experience? I’m like, “I’m not working at McDonald’s. I’m not doing that.” I remember the homies working at McDonald’s and smelling like burgers after. I was like, “Nah, I can’t do it.” So I had a scam, man. I saved up fifteen dollars of my laundry money. We used to put the Metrocards in the coin slot, and just keep the quarters.

So I took the laundry money that I took from my mom, which might have been five dollars each time. I did it, like, three times. I had fifteen dollars, and my homie Eli went half. There was this eccentric white dude named Kief, and we went to him to buy three dimes—fucking giant bags of garbage, but I broke out each dime into five nickels. You turn ten dollars into twenty-five to thirty. You do that three times, and then, after that, our first flip, I might have smoked one bag of it. I bought a half ounce of garbage after that for thirty or thirty-five dollars, and then, after that, there was just no looking back. I was going H.A.M.

SB: Eventually, that led you to FIT?

JG: It’s a lot of stuff between that. That thirty-dollar flip ended up with me probably at the peak grossing fifty to sixty thousand dollars a year when I was fifteen or sixteen years old. You know, grossing. I was doing a lot of wholesale, so it wasn’t all profit, but that type of money was in and out of my hands weekly. If I didn’t make five or ten thousand in a day, I was like, “What the fuck, this is a waste.”

“The reason I don’t sleep straight now is because as soon as I had a cellphone, when I turned sixteen, I never had a straight night’s sleep. My hustle was so ferocious.”

The reason I don’t sleep straight now is because as soon as I had a cellphone, when I turned sixteen, I never had a straight night’s sleep. My hustle was so ferocious. If someone called me at two a.m., and they were a mile out, I’d do that to make five dollars when I first started—ten dollars maybe; five dollars, nah. I tried to force them to get at least twenty to twenty-five dollars’ worth. I had Forced Hustle Tactics. My man Nes calls it FHT. He said I’m the master of the FHT. I’d call you, “It’s time to re-up, bro. Trust me, you don’t want to miss this.” He was like, “No, actually, I’m kind of good.” I’m like, “No, here, take this.” I mastered that tactic.

The week before I got arrested, I had been wanting to get out of the game, and my girlfriend at the time, she was like, “Yo, look, you got money.” [Drug dealing] was a threat to our lives, people were coming to her job, different types of altercations and bang-outs happening about her workplace. I’m like, “You know what? I promised myself I didn’t want to sell drugs as an adult.”

SB: You were nineteen at the time?

Gray as a young child with his family.

JG: I was twenty when I got caught, but I was nineteen when I started kicking it with her. I was like, “I don’t see myself doing this past the age of twenty.”

That ’05, ’06 year was crazy. A lot of violence, a lot of crazy shit, friends I thought were friends turning on me. My aunt, who was my godmother, passed away in ’06, in April. I feel like she held on to celebrate my birthday with me, and then she passed. She’s the person who’s probably been the biggest influence on my life after my mom. When I was thirteen, she used to collect Beanie Babies to talk to me about equity and stocks. She was a computer programer at IBM, but she started at Bankers Trust. She was successful. She had a nice house in Rockland County, and when I lost her, I felt really conflicted. I didn’t spend precious time with her in her last days because I was running these streets, making five to ten thousand dollars a day. I’m like, “What the fuck!” So I started having these internal [debates].

Also, I wasn’t just selling weed. I started selling coke. I made sure there was a balance, though. I never sold crack. And I made sure I put drugs in white communities, too. I had routes in Vermont. I was like, “We got to balance it out. I’m not just going to put this shit where I’m at [in the Bronx and New York City].”

I know I went on a tangent. So yeah, this leads me to FIT. A week before I caught my case, my mother’s like, “Yo, I had a crazy dream. Get rid of all your shit.” I’m like, “I don’t know if I can get rid of it, but what I’ll do is—this will be my last, I’m not going to re-up when I finish with what I got.” A week later, I got caught with the last of what I had. I was going to drop it off for someone else to deal with, because I had a spot in Harlem. The issue with me is, you couldn’t call me to spend twenty dollars, but I’ll still pick up your call if I’m in your area. And I’ll take twenty dollars from you, because I thought about it like lunch money. Like, oh, yeah, this is just lunch, whatever.

This kid calls me for a twenty [bag]. I had been serving him for years. We grew up together—I didn’t think anything of it. He ends up being with the police. But I didn’t know they were police. He’s at my car window, and maybe thirty meters away two guys are sitting on a stoop. I look at them. I’d never seen them before, but they were younger guys. They don’t scream cop, and I just give him, at this point, for something that small, I’m just grabbing the weed out of the bag. I’m like, “Here, just give me.” Lunch money, gas money, it’s nothing. And then he comes back. He was like, “Yo, do you happen to have any coke on you?” I thought it was strange because he never asked me for that, ever. So I do the same thing with the coke—I had a quarter key on me, two hundred grams. And I just snap off half a piece. I’m like, “Here, take it.”

Me being young—and how I was at the time—I had an Audi. I still wanted to be discreet. Like, no rims. I wanted to look like a college kid. I wear durags and shit now, but when I was hustling, you wouldn’t catch me driving around with a durag. I’d be in a polo shirt, and maybe a blazer. I just wanted to look like a college kid. But I skirted off, hit the stop sign, hit the light. I’m about to get on the highway, and in my rearview is someone in a Nissan Ultima. They just cut me off. I’m like, Woah, that’s aggressive. Then vans swarm on me. Fast-forward, I’m facing ten years [in jail], but I had already been thinking about T-shirts and streetwear. When I saw kids who look like they’re from the suburbs doing Wu Tang Clan shirts, I’m like, “I think I can take a crack at this.”

This was a month before I got locked up. That seed was planted—that I was retiring [from selling drugs], just trying to finish out the summer, have a nice little summer run. I got caught in the middle of July, and it kind of fast-forwarded all of that.

SB: What happened in the case? How long was it?

JG: What happened was I went to FIT. I got a job at LensCrafters—shoutout to my man Kawami for getting me that job. Then my cousin Billy J. got me a job in the music industry, doing quality control for this company called Buddy Lube. Which was bugged out, because I was literally responsible for—I don’t know if you remember MySpace, but there was Snapvine, where you could call 50 Cent’s page and leave a voicemail on his page. I was responsible for deleting hate voicemail off of pages for 50 Cent, Slayer, all of these MySpace pages. These people made a business out of managing widgets. I guess they had a nice little run. So that was my job. I was working in Williamsburg [in Brooklyn].

Basically, my lawyer and I had money for bail—I had money for a lawyer. My lawyer went the D.A. and was like, “Look, we got this kid, he’s good.” My great grandfather from the Bronx Shepherds [helped], and Robert Johnson, who was the head of the D.A. in the Bronx at the time, he knew my family. So when I called on people to do character reference letters—

SB: You had a support network, you had a community.

JG: Yeah, my aunt came up from Virginia. My grandmother, my mom—they all came to court with me. I’m in a Tommy trench, button-up oxford shirt, tie, fitted pants. I’m speaking like, “Yes, sir.” I’m speaking like this to the D.A., to the judge. I pleaded guilty to my felony. It dropped from an A2 Felony—which I think carries ten-plus years—to a D Felony, which carries maybe three to nine years. They said, “We’re going to suspend your sentencing for two years.” It worked out good for my lawyer, because it still made me have to pay him. I had to go to court every three months for two years. I had to pay him every court day. He got paid out.

I stayed out of trouble for two years. And we’re talking—I’m taking the train, I don’t even want to look anybody in the eyes, because I don’t want any chance of conflict, I’m reading books, I’m a square, I’m just trying to get through this case. When you’re facing that, you get that feeling in the pit of your stomach. I’m like, “Yo, I can’t go to jail.” I was in the streets wilding. Both of my brothers had been in jail, so I was like, “What’s the odds all three of us go?” Even though the odds are that we all go. You know, when you look at the numbers and the stats …

SB: During this whole time—your youth—your mom was cooking some really good, healthful meals. I think it’s worth noting that she was interested in curative cuisine and studied at the Natural Gourmet Institute. What was the food like in your home? And what role did that play in your life?

JG: I’ll be honest, when I was in the streets, I remember there was a point when my mom didn’t know what to do with me. She called my godfather. I had a girl in the crib, we were doing things we shouldn’t have been doing. And I remember my godfather came to the crib, and the girl’s in the bathroom, not dressed, and they’re like, “Yo, either you leave, or the drugs leave.” I’m like, “I’m leaving with the drugs, fuck you talking about.” I’m sixteen. So me and my mother had a phase where I rented a room in the building I grew up in. I saw my mom in the elevator, and we didn’t even speak to each other. We looked at each other like total strangers, didn’t even say a word. She said that crushed her. It crushed me, too, because I didn’t feel like she loved me.

When my aunt got cancer, I think that was the impetus to start thinking about food as medicine. When you think about Dr. Sebi, and these natural curative methods, she really went into that. My food journey started with my mother, because she was a single mother, worked on Fifth Avenue, loved food. We would go out to eat Indian food, Chinese food, Vietnamese food. My young palate got trained for different flavors. I remember loving the bubbly bread at the Indian restaurant. It came out like a dome; I used to just love poking a hole in it, and ripping it apart, taking the chutneys, doing my thing. That’s how the whole food thing started.

I also went to the 92nd Street Y. I made a cookbook there when I was, like, five or six, after school. We used to make latkes with the applesauce and play draedle. But fast-forward to when I was a teenager: I wasn’t eating any of the shit my mother was making, because she was sprouting beans, she had a dehydrator. I’m like, “What the fuck is this science experiment going on in this refrigerator? I want to get a beef patty with cheese from the block.” I wasn’t really trying to eat that food. But yeah, she was doing her thing.

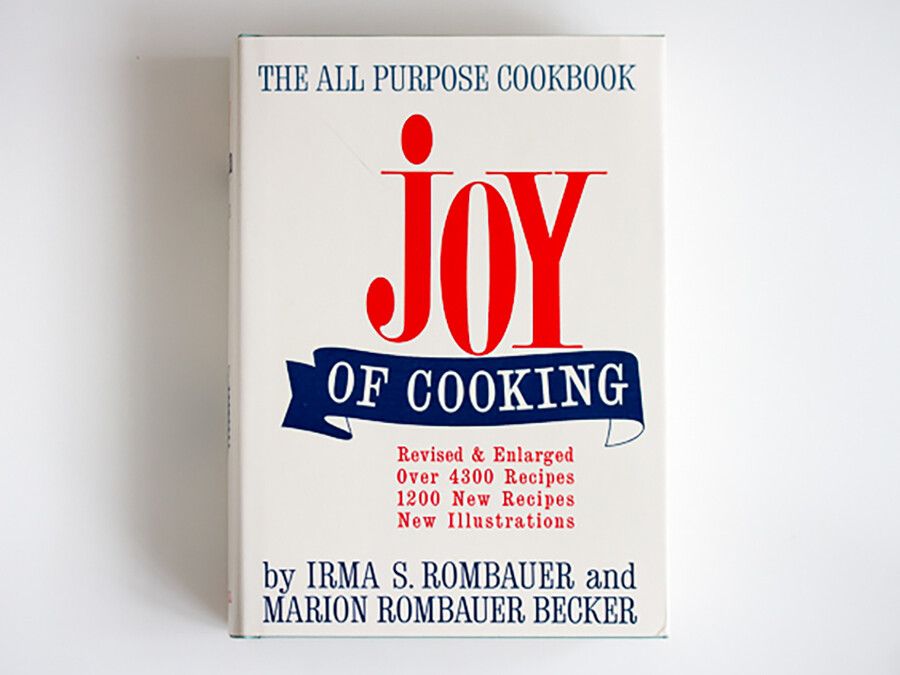

The cover of The Joy of Cooking, which Gray read closely as a child. (Courtesy The Joy of Cooking Trust and the MRB Revocable Trust)

SB: I read in a New York Times piece from 2016 that as a kid you were reading The Joy of Cooking.

JG: Yo, it’s crazy. I don’t know how I got through, like, twenty pages for a roasted chicken. But I was reading that shit. [My mom] had The Joy of Cooking, and I would read that before bed. The language was so dense, and I was really young. I don’t know how I did it.

SB: It was a meal, I understand, that you had in Brooklyn, at Abistro on Myrtle Avenue, that led you to conceive this idea of the collective you now run, Ghetto Gastro.

JG: I wouldn’t say I run it. We’re all partners.

My man Siah was a chef at Abistro. I was living in Dumbo at the time, with a lady friend of mine, and that was my spot. I would go to Myrtle, eat at Abistro. He had the fire fried chicken—and at the time I wasn’t eating a lot of chicken. I was doing pescetarian mostly, dairy-free, and he was killing it. He had a jollof couscous, amazing braised kale, really good salmon. I would get that to-go a lot.

I remember something was happening with the lease [of the restaurant]. He asked me if I would consider buying the restaurant and running it with him. At the time, I’m like, “I can’t really do it.” But I remember going to Abistro for dinner, taking a late nap, waking up, and the name Ghetto Gastro came to me. It was Ghetto Gastronomy, actually. I hit up my man Larry [Ossei Mensah], and I was like, “What do you think of Ghetto Gastronomy?” He was like, “Cut off the -onomy, and do Ghetto Gastro.” I still have the note in my iPhone [from that day]. It was February 2012, during [New York] Fashion Week, when I was like, “Yo, this fashion shit ain’t really it for me.”

SB: So that was the inception.

I want to talk about the word “ghetto,” because I think it’s really interesting in the context of how, by using it in your own specific way, you’re kind of reclaiming it. In a piece in Vogue [in 2018], you actually put it really nicely: “Ghetto is nothing but creativity that hasn’t been stolen yet.”

JG: And I stole that quote, because I heard that quote somewhere else. I might have seen it, but it wasn’t credited, so I don’t know who to credit for that …

SB: Someone.

JG: It’s a great quote, and it’s the truth. And, for me, I like the idea of some things being polarizing.

SB: Which the name is.

JG: Yeah.

“Even people that I love and trust have suggested, ‘Ahhh, the name “ghetto”—why don’t you just call it G Gastro?’ I’m like, ‘My dude, do you hear yourself? G Gastro?!’ That’s not us.”

SB: I mean, I was reading the comments section on a recent WSJ story about Ghetto Gastro.

JG: Oh, I never read the comments.

SB: There are only a few comments, but someone is like, “They should change the name.”

JG: Even people that I love and trust have suggested, “Ahhh, the name ‘ghetto’—why don’t you just call it G Gastro?” I’m like, “My dude, do you hear yourself? G Gastro?!” That’s not us.

Gray at a Ghetto Gastro Waffles + Models party in 2016. (Photo: Liz Barclay)

SB: What does ghetto mean to you?

JG: I’ll unpack it a little. I’m very aware that for many black and brown people that the word “ghetto” being used in the context of what we’re doing could seem retroactive. It could seem like a performative blackness, for clients that are usually white males of means. But it’s not.

I’ve never been one to care about respectability politics, because then also, with black and brown people, there’s a lot of blurriness. We’re not just one people with one mind. There’s a lot of different ideas. In the art world, I’ve also noticed different levels. It’s like, you have your Yale MFAs—who I love; a lot of my friends are Yale MFAs—but then I got banned from all New York City high schools. I have a GED. There are different types of social classism within the world, so, for me, the name is commentary on that. And then it’s just brash. I like being brash. Like, yeah, we’re coming through with durags, chains, and we’re going to cook some of the best food, we’re going to do some of the best design. I want you to think differently about the next brother or sister you see on the train and what they could do.

Also, ghetto for me is home. When I think about how people in Mumbai, Kinshasa, and Nairobi use the word “slum,” its identifying a place and a people, and it’s also implicating the systems and the neglect that have created these conditions.

SB: There’s also this nature that you’re alluding to about ghetto meaning raw or unadulterated. There’s a kind of in-your-faceness to it.

JG: Yeah, it’s like, this is what we are, this is who we are, and this is what we’re doing. This is premium; this is luxury.

It’s an odd thing I’m trying to do. I’m trying to reject the white gaze, and white supremacy and white privilege being the validating force in which we work out of. But then, the other side of that is, those are our clients. For me, it’s the Robin Hood approach: How do we take the work we do and then reinvest and create infrastructure in these neighborhoods—ghettos, slums, favelas—and create a model where, because a lot of my conversation is with me when I’m fifteen, I didn’t have me to look at as an option. Usually the people who came back to the school assemblies to talk about their successes, I thought they were squares. It’s like, who’s talking to who? A lot of times, that’s my driver.

SB: The mission of Ghetto Gastro is to bring Bronx to the world and the world to the Bronx. Talk about that. Tell the listeners what Ghetto Gastro is.

“I would hope that people reflect on what we’re doing as not just a style of food, or a type of social sculpture—like in the vein of a Joseph Beuys or David Hammons. It’s more or less a school of thought.”

JG: It’s a state of mind. It’s a philosophy. Down the line, I would hope that people reflect on what we’re doing as not just a style of food, or a type of social sculpture—like in the vein of a Joseph Beuys or David Hammons. It’s more or less a school of thought, of taking what you have and then just presenting it in a way that’s what you believe is world-class.

Me and my partners, we put in the work. We were able to learn what so-called “world-class” is, then deconstruct and reconstruct what our vision is. I think it’s a state of mind. It’s a vibe, really. That’s what Ghetto Gastro is. When we talk about bringing Ghetto Gastro to the world, it’s celebrating flavors, celebrating aesthetics, celebrating the sounds that were birthed in the Bronx. It’s kind of like The Empire Strikes Back. It’s really just me being upset at Brooklyn getting all the love. People are like “Where Brooklyn at?” in the club, and it’s really loud, and then they’re like “Where the Bronx at?” and people are like, “Ehhh …”

SB: Much is happening with food in the Bronx. You’ve got the Bronx Brewery, and a lot of restaurants coming up.

Gray arriving in Paris for the Bronx Brasserie, which Ghetto Gastro produced as part of Cartier’s Clash de Cartier activation in April 2019. (Photo: Jose Cota)

JG: We love Bronx Brewery, but they also aren’t from the Bronx. But I got mad love for them. We work with them, and I really like what they’re doing.

For me, it’s also this notion of homegrown—for us, by us. Like, yeah, you might think we’re so-called “successful” because you see us in Paris with Virgil [Abloh], but you also see me in the corner store. I’m avoiding plastic, but you might see me buying a Poland Spring because I’m thirsty on your block, or getting a slice of pizza on the block. It’s like that: being accessible and also showing that it’s important that we’re not taking our moneybags and going to Tribeca. Although I did live in the West Village at one point. It was more for market-research purposes.

SB: [Laughs] Elaborate on the community element of what you’re doing. You’ve had aspirations of building a community garden.

JG: Yeah, we wanted to do a community garden. Our buddy Hugo McCloud, who’s an artist, designed this beautiful landscape garden. Then we actually had to change locations, so we don’t have the outdoor space anymore. But we’ll still do it.

For us, right now, like this weekend, Kiara Cristina [Ventura], who’s a really dope young curator from the Bronx—she assists my boy Larry [Ossei Mensah]—she’s hosting an art workshop in the community, where we’ll do a little bit of food, but then she’s walking through art history. We have a space, so we’re thinking, how do we use this space to engage and interact with the community, and still stay true to us?

SB: The space is Labyrinth 1.0.

JG: Labyrinth 1.1. And we’re going to have to move into 1.2 soon, because they’re going to start demo on that building this summer. I’m actively looking for new spots.

SB: Tell me a little bit about your business model, because I think it’s also really interesting to understand that this isn’t a catering company.

JG: Yeah, it’s weird, if people hear that you work with food, the first question is: So the goal is to open a restaurant? I’m like, “Nah, we’re grossing a restaurant’s week in one event.” For us, it’s commission-based. Ultimately, our clients commission us to create these works, which are live sculpture. They’ll include food, music sometimes, and we actually make art or we collab. Like, we did the Radical Kitchen with the Serpentine, with Frida Escobedo. That was a conversation about colonialism, empire, who decides—

SB: Yams.

JG: Yeah, yams. And the transatlantic slave trade, and reappropriation of food and culture, and names from Africa to be marketed for mass culture.

It runs the gamut. Our market is—we don’t do any sales. People holla at us. I get crazy emails. They’ll send an email to hello@ghettogastro.com or Ari [Hayward, our operations assistant]. Someone might respond and say, “Thanks for calling us. Before we start …”—unless it’s something for a friend, or something we really want to support. If you’re a brand that’s reaching out to us, and we don’t know you, it’s like, yeah, this [price] is what it is. Sometimes people get so offended. It’s like if you walk into any store: “This is price. This water bottle might be ten dollars, but you don’t have to buy it. There’s a water fountain right there. It’s cool, this might not be for you.” But people get brash. Sometimes I really love just fucking spanking them on the email if they’re talking crazy to my people.

SB: Your business model is interesting in relationship to time, because, you know, you mention a restaurant—which would probably require being open for lunch, dinner, all those hours, all that turnover—and you can do the same thing, revenue-wise, with one event.

“Proximity to wealthy people isn’t success.”

JG: Yeah, and enjoy it. Whatever we do, we want to do it with excellence. I’m not interested in doing a restaurant. You know, I don’t want to create a job for myself. This whole thing came from reverse-engineering what I wanted my life to be. I spent so much time with money being my guide, taking up my time.

Losing my aunt, and not having that time to spend with her, I’ve really been reflecting on time and thinking about how I want to spend it, who I want to spend my time with, and also realizing another thing in these communities I’ve had the privilege to be around: Proximity to wealthy people isn’t success, and a lot of these motherfuckers are wack. Spending time with wack people was not fun, no matter how much money somebody else might have. It’s not going to change your life, and you could really get caught in that toilet bowl canoe of just being in that. That’s why I went back [to the Bronx]—I’m like, “I’m not feeling this.” My neighbors in Co-Op didn’t speak to me until I dogsat my mother’s poodle. It was like, “Oh, hi! Don’t you live …?” I’m like, “I’ve been living in this building for a year now, and now you want to speak to me?!”

Going back home, and the way people ask—like, I was in the elevator today. My grandmother taught this lady’s granddaughter in fourth grade, and she’s like, “How’s your grandmother doing?” Those types of things have really made me understand how important community is.

I also really enjoy walking into a great restaurant, where I can eat food I want to eat, which is a struggle sometimes at home, especially in Co-Op, because it’s so isolated. I don’t drive, but having people ask about my family kind of tips the scale.

A table setting at the Bronx Brasserie for Cartier. (Photo: Jose Cota)

The bar setting at the Bronx Brasserie. (Photo: Jose Cota)

SB: It’s so refreshing to hear you say this, understanding that you’ve gotten to travel the world doing Ghetto Gastro and experience these polar extremes. I mean, your clients have included Airbnb, Bank of America, Jack Daniels, and Instagram. You mentioned Virgil earlier.

JG: Yeah, Virgil. And Byredo. We’re also doing some stuff with Beats [by Dre]. Apple in Hong Kong next week. Cartier [in Paris] after that. We have a partnership with Audemars Piguet.

It’s a very interesting thing. Like, I was just in Big Sky, Montana, skiing, and then I’m back in the Bronx right after—the Yellowstone Club to the Bronx. It just reinforces the work that I’m supposed to be doing.

SB: You’re this bridge that shows it’s actually not that far from the Yellowstone Club to the Bronx.

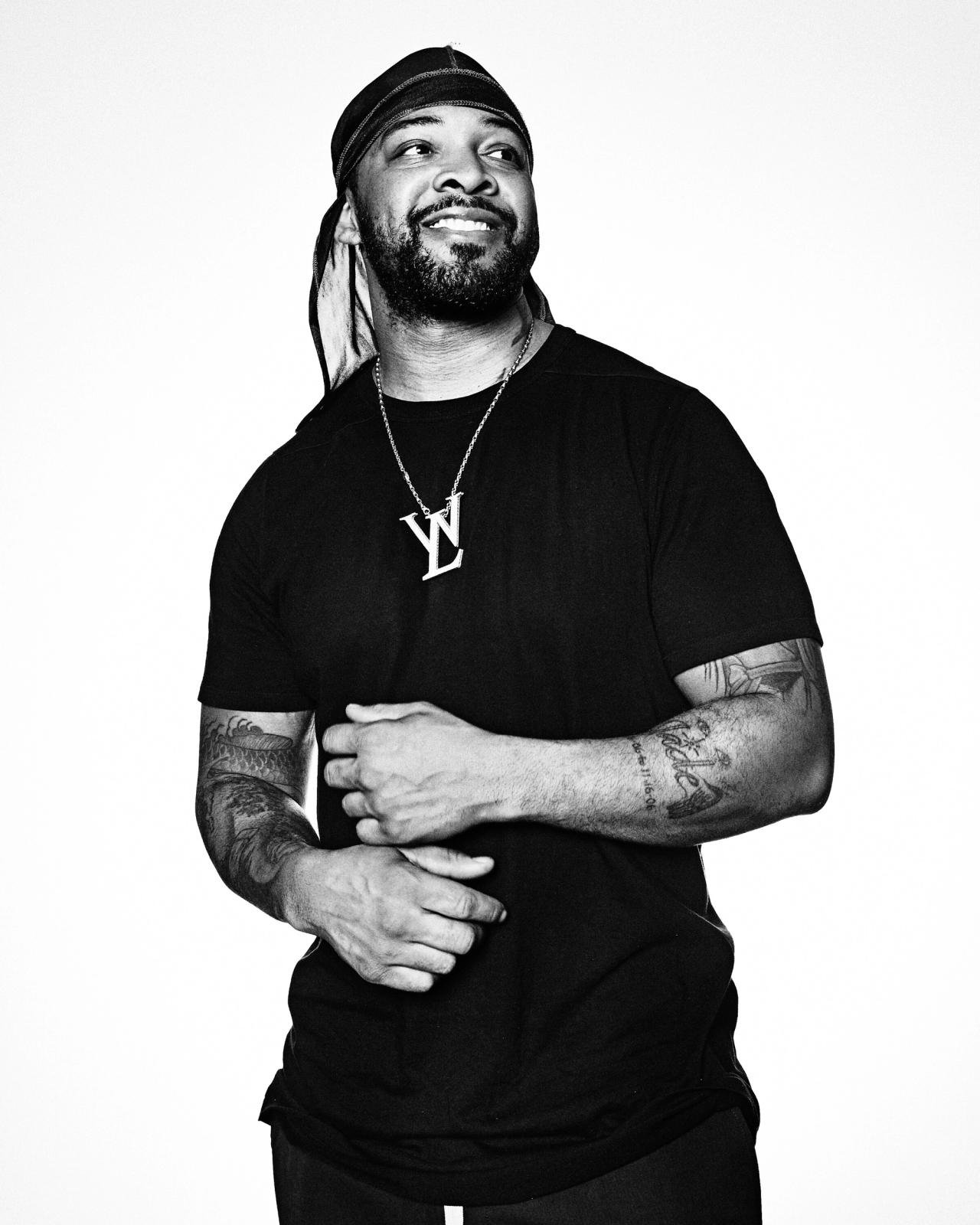

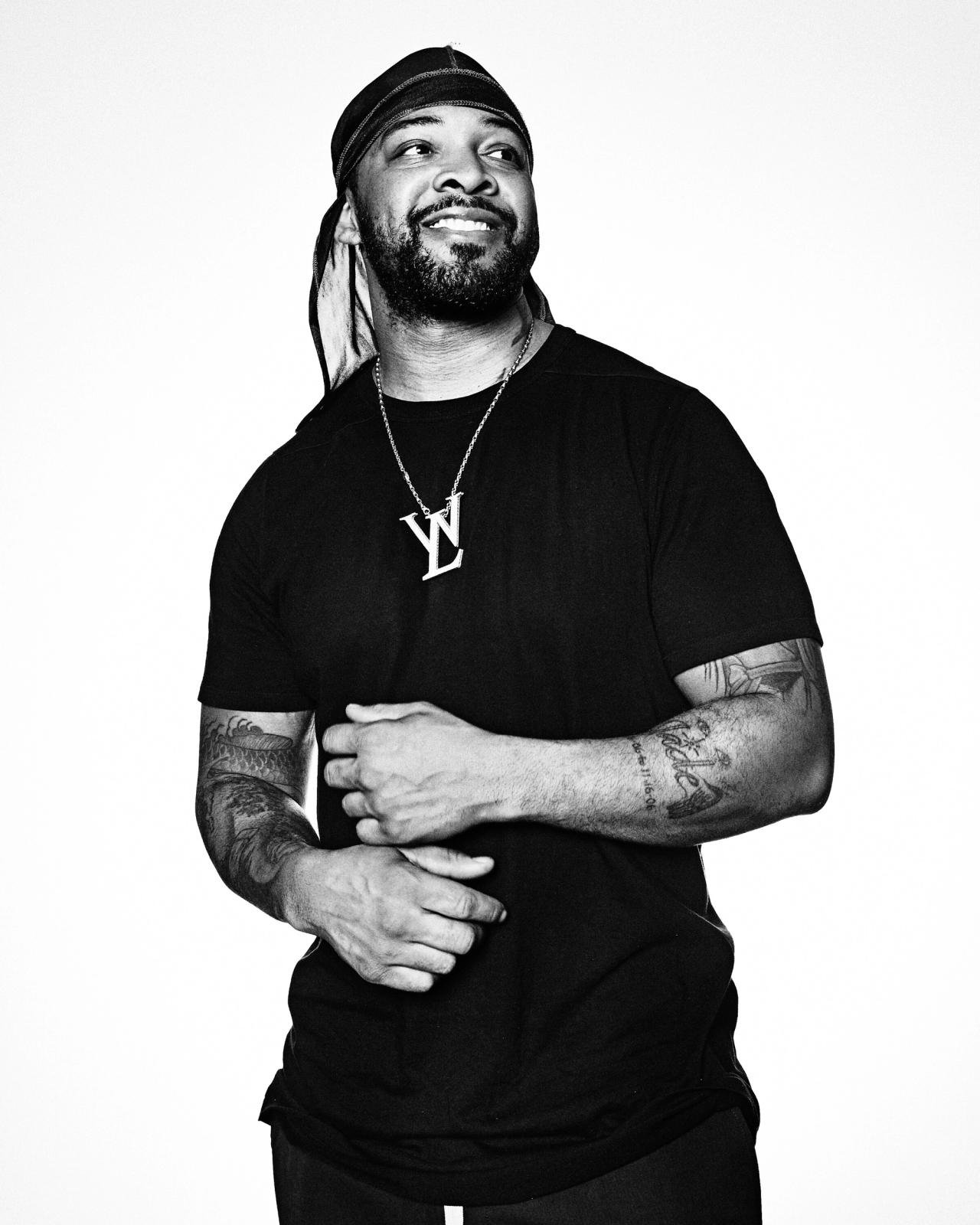

Pierre Serrao (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Malcolm Livingston II (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Lester Walker (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Pierre Serrao (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Malcolm Livingston II (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Lester Walker (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Pierre Serrao (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Malcolm Livingston II (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

Lester Walker (Photo: Revivethecool and Jose Cota)

“People respond to you when you’re comfortable, and when you’re yourself and doing something from an honest place.”

JG: Yeah, and you can be yourself. Like, decide who you are, and just ride with that, because a lot of times you’ll just spend time, or waste time, trying to present ourselves in ways to fit these ideas of what you think you’re supposed to be, ideas that are presented and marketed to us. People respond to you when you’re comfortable, and when you’re yourself and doing something from an honest place.

SB: Food, by its very nature, is about comfort. It was amazing and inspiring watching Lester Walker, who’s one of your Ghetto Gastro co-founders and partners, on [the Food Network show] Chopped.

JG: That was a funny episode, right?

Chefs plating a chicken dish at the Bronx Brasserie. (Photo: Jose Cota)

SB: Great episode. He talks about when he had this deep anger at a young age, because his dad had died. But then cooking saved him—cooking was the thing that pushed him forward, gave him momentum. He did the Careers Through Culinary Arts Program (C-CAP), ended up working for Jean-Georges Vongerichten. This idea of food as a way to turn your life around, or, in your case, just creativity—talk about that from the perspective of the partners and you.

It’s also worth noting that Malcolm Livingston II was the pastry chef at Noma [in Copenhagen, rated the world’s-best restaurant four times].

JG: [Wylie Dufresne’s] WD-50 before that.

Waiters carrying marble plates at the Bronx Brasserie. (Photo: Jose Cota)

SB: Malcolm is a celebrity chef in his own right.

JG: Top five in the world pastry dude. Just in general, yeah.

SB: The third partner is Pierre Serrao, who trained in Italy, working at Cracco in Milan, and later at several restaurants here in New York. How did you bring all these guys together? And how would you view, collectively, the role that food has played in all four of your lives?

JG: Well, it started with me and Les. We’re from the same block. Anybody who knows, knows these [guys from our block] are bonafide street dudes. You could probably see it, just by looking and feeling. But he was always in the kitchen. Me and Les connected on our love of food. Actually, his younger brother, Chad, who’s closer in age to me—two years older than me—is someone I looked up to. We used to play ball, and he would always hold me down, because my grandmother was his teacher and she held him down. We always had that kinship. Then me and Les connected on the food. I let Les tell the story of some of our first early conversations, because I don’t want to put him on blast, or I don’t want to put myself on blast through him.

I was younger than him. A four-year age difference, when you’re thirteen, fifteen, seventeen, or twenty, it’s a big difference. We started bonding when I was maybe seventeen or eighteen, really heavy in the streets, doing my thing. We always discussed the ideas. I remember he had an idea he wanted to do—some catering stuff, food trucks—and I was always down to maybe be an investor if he needed it. I always looked at it from that point of view, and when I had caught the case, I also went to a business-plan program that Allan Houston sponsored with Citibank and the Harlem Y. I was working on putting together a formal business plan and giving it to Les. I was like, “Yo, here, this is what I’m reading, this is what I’m looking at. You want to do this food truck? Look at this.” We just really started bonding heavy in 2007, ’08.

After I caught my case, I met Malcolm [Livingston II]. I was on a date with the lady friend I was living with in Dumbo. I went to WD-50, did some research, because she had really crazy eating restrictions, dietary restrictions—like, is there anything on this menu that she could eat? One thing she liked: ribs. It was definitely not a normal rib at WD-50, if you know anything about the cuisine there. But I saw Malcolm on the website, and I was like, “Yo, this young black dude is running a pastry kitchen?!” This was when WD-50 was still doing an à la carte. So we went through the menu, got to the dessert, and then, yeah, I just ran down on him. He did this crazy aerated ice cream. He made an ice cream, and then vacuum-sealed it, but it was just—imagine cotton candy ice cream. It was like air. And cold. It was root beer flavored. Actually, Mac, when you hear this, man, maybe we need to bring that back to the lab!

I was like, “Yo, I gotta meet this guy.” He was getting changed downstairs—he didn’t want to come back upstairs and meet me. But he came upstairs, we connected. I told him about Ghetto Gastro, which was just an idea at this point. I’m like, “Yo, if you have time. I know you’re crazy-busy doing what you’re doing here”—he was about to get married, too. “If you have time, let’s jam on this together. I think we could really do something.” Me, being an outsider, I was able to see the opportunity. And because of the world I had access to, through my time in fashion and via art, I’m like, “We could come through. We got something to say. It’s an open lane that we could carve.”

The scene at a Ghetto Gastro Waffles + Models party in 2016. (Photo: Liz Barclay)

SB: Your breakthrough event was—

JG: Waffles + Models.

SB: Was that the event with Solange [Knowles]?

JG: It was with Cardi B—when Cardi B was still a dancer. I had met her the night before, dancing, and I was like, “Yo, we’re doing this party Waffles + Models, would you be down?” She’s like, “Yeah, I’ll be making money?” And I was like, “Yeah, you’re going to make some money.” She was super-cool. That was where our story with Cardi B started: She was dancing at our first Waffles + Models, and the photojournalist from the New York Observer—before they were pro-Trump; I’d never be in them now—photographed us. They did a story on Waffles + Models, and that was our first piece of print press. The photography was good, and it was definitely the best party of [New York] Fashion Week. That’s where it started.

Rest in peace to my man Nelson [Campbell], who put up some bread for us to execute that. He passed away this past Friday. Had a brain aneurysm, man. That shit really fucked me up.

SB: I’m sorry.

JG: But I know he’s up there looking down on us, happy.

SB: In the years since, you’ve done things like converting a 125th Street apartment building into “Harlem World” for Airbnb. You’ve cooked jerked bone marrow with Martha Stewart.

JG: Yeah, yeah.

From left, Pierre Serrao, Rachael Ray, Lester Walker, Malcolm Livingston II, and Gray on the Rachael Ray Show in 2017.

SB: You’ve been on the Rachael Ray show. You’ve done a Black Lives Matter–inspired pie with Hank Willis Thomas.

JG: Shoutout to Hank and Ruje[ko Hockley] and their new baby. Big up to y’all.

SB: Even during Art Basel, you did this freeze-dried coconut powder, atop these plates, that looked like cocaine.

JG: Yeah, it was mirror plates, and it was bugged out. We did the party with [the French fashion brand] Pigalle and [the production company] Grit. We rented this mansion. The dude who owns the mansion, I guess he planted a spy in the party that night, and It was crazy. Like, Virgil [Abloh]’s djing, and all these things—Theophilus [London], [A$AP] Ferg, Hiroki [Nakamura], everyone was coming through. We had this dish, and it really showed who the fiends were, because people were walking across the kitchen, thinking it was coke, and they wanted to party.

The next day, Grit, my friends who had rented the spot, they were like, “Yeah, the owner just called about all of these drugs that were being done at the party.” They had had a drone flying outside. It was wild.

SB: But it wasn’t cocaine. It was food.

JG: It was food, it was food. Just us having fun. We approach projects like, “What do we want to do?” The commission is the opportunity for us to do something that we wouldn’t necessarily do that we want to do.

SB: Now you’re creating your own sort of media platform, too, with the YouTube video series Stease The Day.

JG: We’re dropping those on the first and fifteenth of every month—you know, quick. People have been wanting recipes from us for a while now. Like, I look at Bon Appétit—let me not say Bon Appétit, because we might be doing a project with them. Shoutout to Bon Appétit!

But I look at some of these traditional food outlets, and I’m like, I don’t want to do just—top down, it’s like, how do we make this us and bring a vibe to it, make it somewhat entertaining, something that’s interesting to us? That’s what Stease The Day came out of.

It’s also a platform to highlight the spice line we’re working on, called Steasoning. It’s going to be a line of spices and sauces, just so people could make things that are super-tasty but relatively easy. If you don’t have an hour to prep, here’s some recipes make some fly shit. You have a significant other you’re hosting? Some friends? We’re going to give you the tools to make some easy fly shit.

SB: You’re also working on a kitchenware collection, Triple Beam Dream.

“That’s what I do with my practice in general: take pain and present it in a precious way.”

JG: Yeah, TBD. I’m actually going to Murano [in Italy] in a week to work on the first samples. We’re doing a film with Nowness about the whole process, because it really relates to CorningWare and Pyrex, and how that played into the crack era. We’re taking some of those aesthetics, and really turning the pain into something precious. I think that’s what I do with my practice in general: take pain and present it in a precious way.

SB: And there’s a knife line, Ogun, you’re launching soon.

JG: Ogun, yeah. I was super-interested in the deities, and thinking about what we were doing on a continent before missionary work, before slavery, and some of these traditions. Ogun is a [state] in Nigeria; it means war, but it’s also the god of iron, the orisha of iron, the deity of iron. But if you think of ogun, it relates to Shōgun. We’re making the blades in Japan. We love the bladesmiths over there—some of the best, like Takamura and people in Takefu Knife Village. We’re like, how do we bring these ideas and aesthetics together in a way that’s truly us? That’s how we started it.

SB: I also read [in WSJ. Magazine] that you’re going to be running a Carribean-style patty chain, and that you’re thinking about doing a vegan ice cream.

“The world needs better rich people. We’re going to become them, and do what we want to do for our community with the funds. We don’t want to ask permission to do anything.”

JG: Oh yeah, we’re doing dairy-free gelato. That’s 36 Brix. And Patty Posse are the patties. The patties are crazy. Malcolm created this flaky crust—the patties are all about the crust. We have some really dope fillings that are nonconventional, too. We’re really just taking the culture—things that we grew up with—and presenting them with a different skin.

We’re not doing rocket science or curing cancer; a lot of this stuff is selfless selfishness. The world needs better rich people. We’re going to become them, and do what we want to do for our community with the funds. We don’t want to ask permission to do anything.

SB: I wanted to end our conversation on the Bronx, and specifically thinking about both the work that you’re doing and the impact you hope it has on the borough. But also sort of the inverse of that. Like, how you hope the work you’re doing, in a way, is exporting the Bronx to the world? Because there are a lot of interesting things to talk about here. Of course, there are the realities of the hardships of the Bronx, like the South Bronx has the highest rate of food insecurity in the country.

JG: Shit, I didn’t even know that.

SB: Yeah.

JG: Fuck. And you know what’s ironic about that? Hunts Point is also the home to the largest food distribution center of its kind in the world. The Fulton Fish Market that moved from South Street Seaport to up there [in the Bronx] is the second-largest in the world, next to Tsukiji [fish market] in Tokyo. This is the type of shit that really frustrates me, where I want to get on some gangster shit, but I’m just doing it a different way—in a way that really resonates.

SB: I was reading online that Hunts Point generates more than two billion dollars in annual sales. The disparity of that. And there’s the highest rate of obesity in New York City in the Bronx.

JG: Diabetes, asthma …

SB: Yeah, asthma. Children who are more likely to be hospitalized, period. All of that happening in the midst of this really robust economic situation for Hunts Point. What sort of impact could you see happening, or what would you hope to have happen?

“The Bronx is a mindset. There’s a Bronx in every city and state in the world.”

JG: For me, it’s really hopefully impregnating—not impregnating, that’s maybe not a good word to use these days, but being infectious. I just want to shine a light on how great we are [in the Bronx]—as a culture, as a people—and what we’ve been able to create. When you think about hip-hop, salsa, the emergence of street art, the writer’s benches, all of these things that were the genesis of these forms—a lot of it started in the Bronx. But the trickle-down impact of it has never really impacted the Bronx or these communities that create these beautiful art forms out of blight, out of divestment, out of neglect. It’s like pointing a light on what we do. What we create is valuable.

The Bronx is a mindset. There’s a Bronx in every city and state in the world. I’ll be ecstatic if I see some kids in a favela in Brazil making their own icees and selling them all over [the world], and bringing those economics back [to the favela]. For me, it’s like it’s a case study in doing work you believe in. I’ll work first, I’ll be honest. It’s about the work, and I think it’s going to have these effects.

Gray on the mic during the Bronx Brasserie activation for Cartier in Paris in April 2019. (Photo: Jose Cota)

When we’re thinking about cultural centers, innovation labs, creating jobs—these types of things are some of the milestones when I start to reverse-engineer what success might look like. And that might change; it’s a constant evolution. But, to me, it’s really making the Bronx a world-class art destination, where the people are actually benefiting from this creativity that spawns, because wherever you have poverty, you have to get creative, to home into that, and hopeful reverse some of those engineered effects.

SB: Food is kind of just setting the table for this conversation, in a way.

“I think food is one of the best connective tissues that humans have.”

JG: Yeah, because when you’re thinking about this food insecurity, when you’re thinking about Hunts Point bustling and supplying a lot of the East Coast with its food, the irony is crazy. I think food is one of the best connective tissues that humans have. The first social network was the table or the cave where they shared a meal. That’s where things were discussed, and where people broke bread and decided if they liked somebody, and decided if they had similar tastes. Food’s about nourishment. There’s also the residual effects of creating it, contextualizing a language through it.

SB: Thanks, Jon. This is great.

JG: The culture will not be colonized.

SB: Great to have you here today.

JG: Thanks for having me. I know I went on fucking weird tangents and drag-ons and shit, but you can fix that in post-[production].

SB: No, it’s great. It’s all relative in the end.

JG: No doubt, no doubt, thanks for having me.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on March 19, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by our director of strategy and operations, Emily Queen, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.