Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

David Wallace-Wells.

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: David, thanks so much for joining us today.

DAVID WALLACE-WELLS: Really good to be here. Thanks for having me.

AZ: I think many of us, certainly our listeners, are highly concerned—maybe even panicked, if you’ve heard this before—about the speed at which our planet is changing. I thought we’d just begin, very simply, with the state of the planet, as you see it—

DW: [Laughs] Very simply.

AZ: Very simply, today.

DW: Depending on what data set you use—and this may get a little wonky, but I’ll try to be as clear as possible—we’re probably at about 1.2, maybe 1.3 degrees Celsius of warming, which is above the level that we saw on the planet before the industrial revolution—1.2 or 1.3. That doesn’t sound like very much, but it actually puts us entirely outside the window of temperatures that enclose the entire history of human civilization. It is warmer now on the planet than it has ever been when humans were around to walk on it. Which means that everything that we’ve ever produced as a species—our culture, our politics, our music, our movies, our agriculture, the nation state, family structure—everything, down to the most basic features of human life, are the result of climate conditions that we’ve already left behind. We’re already warmer than that, today. And, probably, we’re going to get considerably warmer from there.

“It is warmer now on the planet than it has ever been when humans were around to walk on it.”

All of the activism and advocacy has focused on this 1.5 degree Celsius of warming target. I think it’s unlikely we’ll hit that. I think something like two degrees, maybe a little cooler than that, is our best-case scenario. We’re looking at something like, absolute best case—if the world does absolutely everything it can to move quickly, to respond to climate change and stop putting carbon into the atmosphere—we’re going to end up with something like fifty percent worse warming than we have today.

What that means, according to the science, is quite grim. It means a hundred and fifty million deaths from air pollution. It means storms and floods that used to hit once a century hitting once every year. It means people in South Asia and the Middle East walking around in cities that are today home to ten or twelve million people, where it would be, in summer, so hot that it would be a potentially lethal risk. It’s one reason why the U.N. expects that at about that level of warming we could see hundreds of millions of climate refugees, and that’s in the not-too-distant future.

AZ: And irreversible?

DW: Well, we can talk about irreversibility. Conventional thinking, which I think is a good baseline to start from, is that, yes, it is irreversible. And that’s because carbon hangs in the air for at least centuries, and probably millennia. A climate scientist I spoke with recently told me that, through natural processes, it would take a million years for the earth to return to its pre-industrial carbon state. If we just stopped emitting today, it would take a million years to get back to where we were.

Among other things, that means that the damage we’re doing is cumulative. Carbon that we burned in nineteenth-century England is still warming the planet, and will warm the planet for several hundred years, at least, from now. In that sense, it is interchangeable with carbon that we are burning today, and carbon that we’re burning in the next decade.

“There’s a way in which we’re living in an eternal present of climate change, where what was done two hundred years ago, what’s being done today, and what will be done fifty years [from now] are all working together, essentially on the same timeline.”

There’s a way in which we’re living in an eternal present of climate change, where what was done two hundred years ago, what’s being done today, and what will be done fifty years [from now] are all working together, essentially on the same timeline, and we are living, as a species, waiting for that gas—carbon dioxide—just to dissipate in space. And this whole story, in which we are completely rebuilding, remodeling the planet on which we live, is unfolding in that amount of time—in the amount of time that it takes the carbon that we’re producing to dissipate in space, which makes the whole experiment seem quite fragile.

And I think that’s one really valuable lesson of climate change is that, it is. We are here today—conquerors of this world, feeling like we own this place—because of a long string of accidents, and what we are doing today, through burning carbon, is making the conditions that gave rise to that experiment, at the very least, much more uncomfortable and harder for us, and maybe even, in certain parts of the world, un-overcomable.

But to get back to the question that you asked at the outset, just to give one more data point: When I think about how much the world is today, different—so not at two degrees, but at 1.2, 1.3 degrees—the thing that I always come back to relates to time and the distortion of time. And it’s about the fact that the city of Houston was hit by five five-hundred-year storms in five years. We know now, as deep into climate change as we are—anyone who’s engaged, anyone who has their eyes open—we know that the term “five-hundred-year storm” is meaningless. It gets thrown about all the time. But it’s useful because it reminds us what we used to think of storms like these. We used to expect them—not because of old wives’ tales, but because of science. We used to expect them to happen once every five hundred years.

And five hundred years ago, there were no Europeans in North America. Hernán Cortés had just landed in Mexico. We’re talking about a storm that we would expect to hit once during that entire time—the arrival of Europeans in North America, the establishing of colonies, the fighting of a genocide against the native people, the building of a slave empire, the fighting of a revolution, the fighting of a civil war, industrialization, World War I, World War II, the American empire, the Cold War, the end of history, September 11, the financial crisis, Covid-19—that entire history we’re talking about, one storm we would expect during that entire time. And Houston has been hit by five of them in five years. Which means that one city, and it’s not at all exceptional, has been basically hit with several millennia of natural disaster and extreme weather in the space of half a decade.

“There’s the climate side of the story, and there’s the human side of the story, and human adaptation and resilience and response will play a major role here.”

Now, Houston’s still standing, and I think that’s a valuable and important point, too. There’s the climate side of the story, and there’s the human side of the story, and human adaptation and resilience and response will play a major role here. But it’s still a level of everyday climate disaster that nobody alive fifty years ago would’ve recognized as anything like normal. And yet, here we are today normalizing it quite rapidly.

AZ: The fire season in—

DW: Oh, my god. The fires really terrify me, in particular, because of the air pollution stuff that’s coming out of it. But yeah, I wrote a piece about wildfire in California in the spring of 2019 about wildfire in California in the spring of 2019. It was in the aftermath of their really awful 2018 year, which had been the worst year on record up to that point in modern history. I talked to Eric Garcetti, the mayor of L.A., who, among other things, told me that there was nothing that could be done to stop this. He was like, “No amount of fire engines, no amount of funding for Cal Fire, can stop this. The only thing that’s going to stop it is when the earth’s climate system, probably long after we’re gone, returns to its natural weather state.” That’s what the mayor of Los Angeles said—

The Woolsey Fire, a wildfire that burned in Los Angeles and Ventura Counties, ignited on November 8, 2018, and burned a total of 96,949 acres of land. (Courtesy United States Forest Service. Photo: Peter Buschmann)

A helicopter dropping water and fire retardant on the Harris fire in Southern California in 2007. (Photo: Andrea Booher)

AZ: I remember reading it. You were basically like, “This is a thing. It’s not going anywhere.”

DW: Yeah, and it’s going to get worse. A lot of people in California think, Okay, new normal. But actually, everything with climate, it’s not a new normal. It’s the end of normal. Things are going to get worse. We will still live in that world. It’s not apocalypse; it’s not end times. But if you think it’s hard to adjust to the things that are happening today, the future is really much harder.

Garcetti—I think he just turned 50—the year he was born, sixty thousand acres burned in California. The year he was elected mayor in 2013, it was six hundred thousand. So a tenfold increase. The year he was reelected, 2017, it was 1.2 million. So a doubling. Then 2018, the year before I’d interviewed him, it was 1.89 million. So a fifty percent increase in a single year. Whatever that is, that’s a twenty-five-fold increase from the year that he was born.

The Erbes Fire, which burned in Thousand Oaks, California in 2021. (Courtesy Ventura County Fire Department)

Then, last year, 2020, was considerably worse than that. It was over four million acres burned. That meant that last year, 2020, there was more air pollution in the Western U.S. from the burning of forests than from all other industrial and human activity combined. Which means, like, everything that we’re doing in a place like California, with all of its admirable green energy policies, can just be wiped out by the fire seasons that are getting worse every year, both in terms of carbon emissions—trees are like coal, they release carbon—and also in terms of this particulate matter, that’s really, really damaging and toxic to health in ways I think we’re really only beginning to understand, although—

AZ: Because it takes time to—

DW: Study it.

AZ: Yeah.

“A lot of people in California think, Okay, new normal. But actually, everything with climate, it’s not a new normal. It’s the end of normal. Things are going to get worse.”

DW: But looking globally, the W.H.O. and the British medical journal The Lancet say seven million people are dying from air pollution every year. I’ve seen more recent research by some quite smart people, who are not being irresponsible, who think that it’s 8.7 million dying just from the burning of fossil fuels. That’s 8.7 million people every year. You think about… That’s bigger than Covid was last year, globally. It’s happening every single year.

In terms of carbon emissions, this year, 2021, more carbon has been released from global wildfire than was released by the entire U.S. economy last year. And the U.S. is, of course, the world’s second-biggest emitter. When you think about the really big picture of wildfire, and the story of wildfire, carbon emissions are still a relatively small share of the global emissions chart, but they’re getting up there, and they’re only going to grow. And that’s going to make all of our efforts to halt warming a lot harder. Like a lot of things in this system, there are things we can control, and then there are things that we can’t really control. Unfortunately, wildfire is really…. There are some things we can do, but it’s, in a lot of ways, out of our control for the next fifty years.

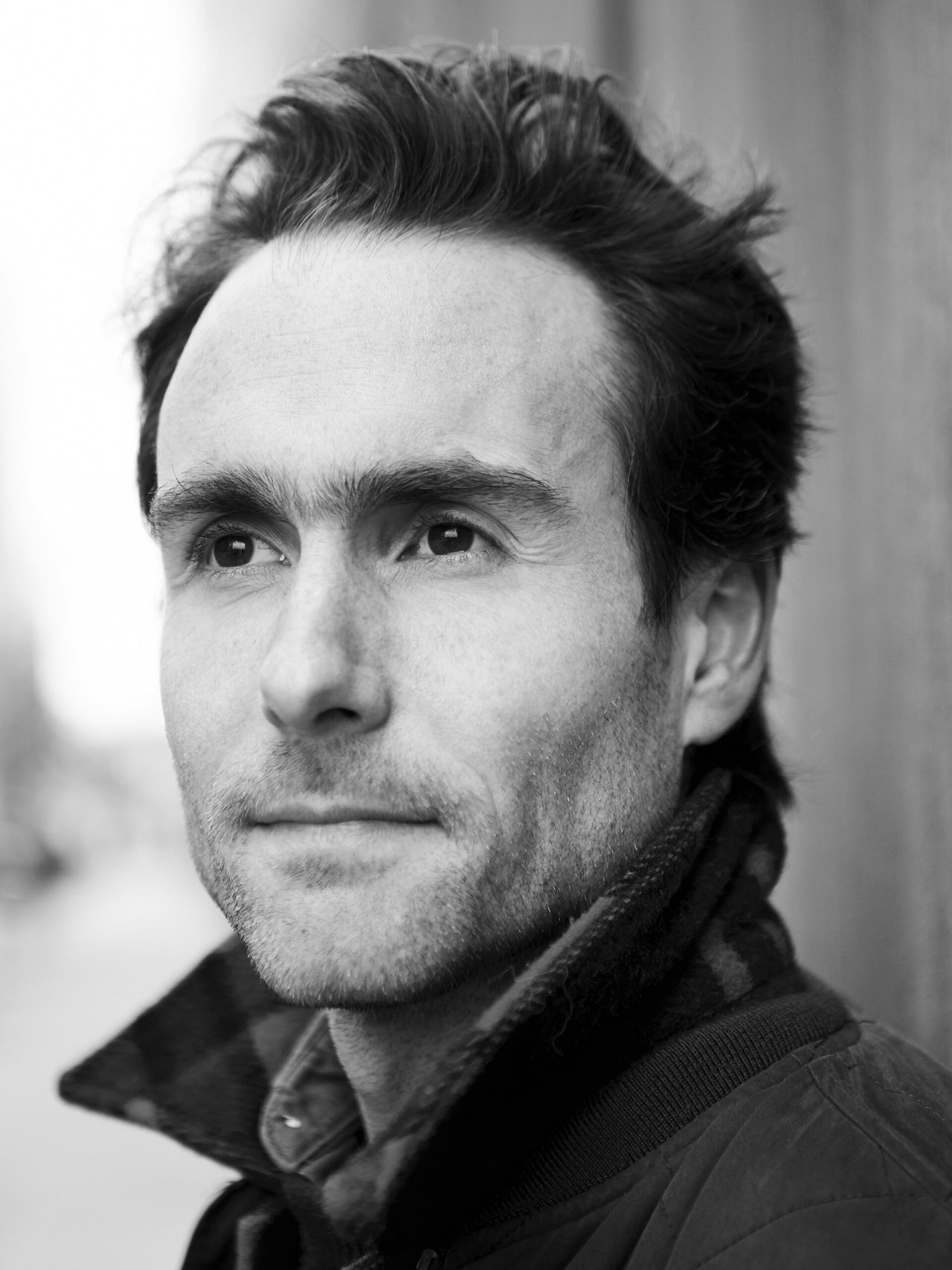

Cover of The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming (2020) by David Wallace-Wells. (Courtesy Crown Publishing)

AZ: Absolutely. And now it’s the season. That just confounds me.

DW: The Cal Fire people, they say it’s a year. They’re not even talking about seasons.

AZ: They’re saying it’s all year now.

DW: It’s all year. That’s a little misleading. Like, you can breathe easy in the winter months in California. But this year, the bad fires started in the late spring, early summer, and they ended a little early this year, actually. We haven’t seen a lot of stuff in December. But a lot of the biggest fires in the last couple of years have been in early December. So, it’s bad.

AZ: In your book The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming, you wrote this one thought that’s really stuck with me, which is that, “Climate change is fast, much faster than it seems we have the capacity to recognize and acknowledge. But it’s also long, almost longer than we can truly imagine.” What I was curious about was how you came to understanding the speed—how you got your head around this idea of the speed at which it was changing.

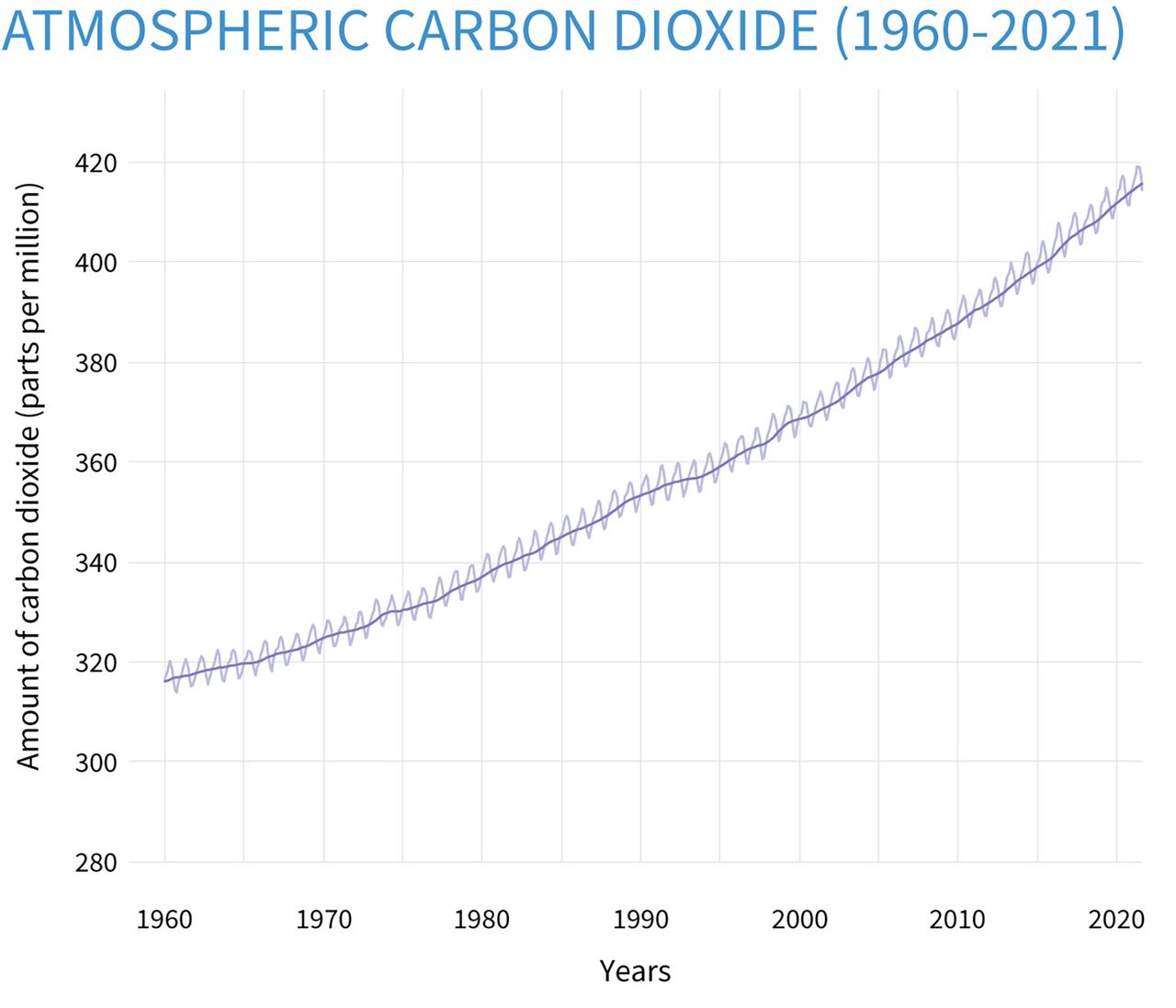

DW: Well, the fact that sticks with me most and was probably the really eye-opening thing for me to begin with—still really hard for me to believe—is about the speed at which we’ve put all this carbon into the atmosphere. I was born in 1982. I’m thirty-nine now. I don’t remember a time before we were talking about climate change. I talked about climate change in elementary school. It wasn’t like a dominant narrative, but it was like, we knew it was happening; we knew it was a problem. Until I really started working deeply in this, I simply didn’t appreciate that half of all of the damage that we’ve done to the planet in the entire history of humanity has come in the last twenty-five years. So that means, in my lifetime, it’s like sixty or sixty-five percent of the problem.

“Half of all of the damage that we’ve done to the planet in the entire history of humanity has come in the last twenty-five years.”

We think of this as something that started in eighteenth-century England, and to some degree, that’s true. But the vast bulk of carbon emissions have been produced since World War II, something like ninety percent of all in the history of humanity, and a really large share have come in the very recent past. So you have fifty percent in the last twenty-five years, which is since Al Gore published his first book [An Inconvenient Truth] on warming; it’s since the U.N. [Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization] established its I.P.C.C. climate-change body.

Cover of An Inconvenient Truth by Al Gore. (Courtesy Crown Publishing)

I often joke, it’s like, since the premiere of Seinfeld, we’ve done more damage since then, than we’ve managed in all the centuries, all the millennia that came before. But even when you get a little closer to the present, one quarter of all the damage that we’ve done to the climate through the burning of fossil fuels has come since Joe Biden was elected vice president, running with Barack Obama on a ticket. Barack Obama, accepting the Democratic nomination, said, “This is going to be the moment when people look back and say, ‘That was when the rising of the seas began to slow.’” That’s what he said when he took the Democratic nomination, and we’ve done a quarter of all the damage that we’ve ever done in the entire history of humanity in that time. That’s really a vertiginous speed.

Because emissions are cumulative—because they just add up, they stockpile—it really…. What we’ve done in the recent past really changes what the near future has to look like, if we want to get a handle on things. If we had started cutting carbon emissions in 1988, when James Hansen first testified before the U.S. Senate about climate change, not only would we only have had to cut emissions by a couple of percentage points a year to stable at 1.5 degrees, which is now our goal, but we could have taken about a hundred and thirty-five years to get all the way to net zero. We wouldn’t have even had to complete that project by the year 2100.

But we’ve added so much more carbon to the atmosphere since then, that now, in order to stay stable at 1.5 degrees, we have to definitely, no matter what math you use, get to zero by 2050, which is only thirty years from now, and the models just say that gives us a fifty percent chance of staying below 1.5 degrees. It would also require a lot of what’s called “negative emissions”—carbon removal. Which connects to something else we touched on earlier about irreversibility, and we can talk about that, too, because carbon removal does allow for the reversibility of time here. But these timelines are just much, much shorter, and the descent from the emissions peak that we’re at now has to be so much more rapid than it would’ve been if we had started earlier.

Climate scientist Dr. James Hansen speaking at the CCAN (Chesapeake Climate Action Network) plunge, which raises awareness about global warming, with the aim to “Keep Winter Cold.” (Courtesy Chesapeake Climate Action Network. Photo: Josh Lopez)

I think a lot of people have this reflexive understanding of the challenge, which they think, Okay, we didn’t wake up when James Hansen talked to us. We didn’t wake up when Al Gore shouted at us. But we’re waking up now. They think what that means, then, is that we have to put in the policies that would’ve been recommended by James Hansen in 1988 or by Al Gore in 2007. But putting aside whether Al Gore was even saying things that were sufficient in 2007, they’re not sufficient now, by any stretch. And every year of delay makes the future task much, much harder, which means the transformation that we’re talking about—which will be beneficial in the long run if we undertake it—is just going to be much more disruptive and rapid than ideal.

AZ: Having a front seat for all of this—and you write about culture, you write about pandemics, you write about climate; you’re not just a climate journalist, this is fairly recent, actually—from your perspective on the human condition and how we behave and how we think, what do you think the next decade is actually going to look like?

“Every year of delay makes the future task much, much harder.”

DW: It looks a lot happier to me than it looked when I wrote the book, and certainly when I wrote the article that first kicked me off into this story, a few years ago. I think that the world is genuinely waking up [to the climate crisis]. I think that that has happened over the last couple of years. I think there are a few different things that really kicked it into high gear, but the U.N. released this big report on…. Technically it was just outlining the difference between 1.5 degrees and two degrees, but it was basically a case for urgency, and made in much more alarmist language than had ever been used before.

The abstract of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (I.P.C.C.) special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C. (Courtesy I.P.C.C.)

That was picked up by Greta Thunberg, who had just started protesting, actually, before that had come out, but was not at all a famous person, even in Sweden. And then, by all of the people who are pushing a Green New Deal—from Sunrise to A.O.C. [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez], and globally by other climate strikers and Extinction Rebellion—we now have a global climate movement in a way that, frankly, I wouldn’t have thought was possible when I was writing my book. I knew that we’d have to engineer our solution largely through politics, but I also looked back at the history of environmental activism and thought, There are not really many successes here. Like, what are we hoping for? But actually, the politics have really changed over the last few years. Not just with the activist base growing, but public concern is really growing. Not just like, progressive liberals, but normie liberals and even normie conservatives are worried, want more to be done.

AZ: And corporations see it as, like, a brand value now to care.

DW: Absolutely. And politicians.

AZ: Yeah.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (center) speaks on the Green New Deal with Senator Ed Markey (right) in front of the Capitol Building in February 2019. (Courtesy Senate Democrats)

DW: Now, the corporations and the politicians, I think, are complicated players here. They are often making promises I think they’re not really prepared to meet, essentially offering lip service to the cause. But on the one hand, I think, we have to treat that as progress anyway. They weren’t even acknowledging the necessity of this urgency a few years ago. At the same time, concretely, they are doing more.

AZ: The commitment to E.V.s—almost every car manufacturer—I mean, we are seeing a lot of shifts in the last year.

DW: Absolutely. A lot of that has to do with the economics of it. Renewables are now cheaper in ninety percent of the world than new, dirty energy. In fact, in a lot of parts of the world, it’s cheaper to build new renewable capacity than even continuing to run old, dirty energy capacity. I think that one thing that it tells you is that while for a long time this was conceived as an economic problem—like how can we ask our citizens to accept this burden, to pay more for electricity, for power, for their lifestyles, generally—it now seems pretty clear that the economics actually are arguing for a faster transition, and the forces that are standing in the way are entrenched interests, incumbency, status quo, people who don’t want change even separate from whether the change is going to make their lives good; they just don’t like change. So it looks like a little bit of a different battle.

I think, in the long term, that battle is going to be won, but it’s going to take longer than the scientists say we really have to give us a decent chance of stabilizing warming below a level that they call catastrophic. I think the medium-term future is that we move quite fast, that there is a lot of renewable build-out. There is even going to start to be some fossil-fuel retirement—we’re seeing that with coal plants already. There are a lot of people who are just buying up coal plants to shut them down, which is, to think about—that’s just crazy to think someone would do that, but it’s already happening. I think that may start to happen—

AZ: Happens in every other industry.

DW: Yeah, true.

AZ: Acquire things to shut them down.

“What we’re likely to see is a really fast period of change that is insufficiently fast to really deal with the crisis, but which is also really disruptive and disturbing to a lot of people, because their lives are being changed.”

DW: No, that’s true. Hopefully that’ll start to happen in oil and gas as well, but it’s also going to be important to manage that, so that we don’t have these major disruptions like we’re even seeing this winter, where energy prices are skyrocketing, and there’s backlash and disruption in China and across Europe. I think what we’re likely to see is a really fast period of change that is insufficiently fast to really deal with the crisis, but which is also really disruptive and disturbing to a lot of people, because their lives are being changed.

I think that’s basically exciting, but also a little treacherous, and I don’t know exactly how it’s going to play out. I don’t think there’s going to be, like, major global backlash that prevents climate action for thirty years, but I think that there are going to be micro-resistances here and there.

AZ: Oh, definitely. And from unlikely places. I want to get into a bit of that later, about the politics of it. But regarding you as a journalist, you work with storytelling to essentially change behaviors, on some level. Not that you definitely have an agenda, but specifically in this book, in the article that preceded it, I’m sure you were trying to make people aware on some level, and change behaviors. I’m curious now, in this moment, how you see your role as a storyteller in combating the climate crisis. What’s your position here? What’s the assignment? [Laughter]

Wallace-Wells’ 2017 article “The Uninhabitable Earth” in New York Magazine. (Courtesy New York Magazine)

“I often feel awkwardly cast in the role of advocate.”

DW: Well, it’s interesting. I often feel awkwardly cast in the role of advocate. I don’t think that there’s any denying that part of why I wrote the book, and part of why I wrote the article, was to make people think differently about what we were facing, presumably to inspire some more political engagement and movement. But at a core, who-I-am, reptilian level, I really still do think of myself as a journalist who is observing the story as it’s unfolding. I think probably my role in the present moment is to try to be as clear-eyed about that as possible, rather than succumbing to advocacy.

“At a core, who-I-am, reptilian level, I really still do think of myself as a journalist who is observing the story as it’s unfolding. I think probably my role in the present moment is to try to be as clear-eyed about that as possible, rather than succumbing to advocacy.”

I think denial’s dead, but on the climate delay side of things, there’s a lot of disinformation and bad-faith argumentation. But there’s also some willful blindness on the climate left. Not wanting to see, for instance, the energy problems that are unfolding right now as a problem, and just say, “We can snap our fingers and solve this immediately.” I think that’s kind of naïve. Sometimes not wanting to think about, or plan for, using certain tools that all of the climate models now say are necessary if we take seriously our collective goals.

That may sound a little abstract, but we’ve touched on negative emissions a couple of times. Just to be clear about what that is: It’s basically any process that takes carbon out of the atmosphere. Over time, at scale, you could, in theory—especially if we get to net-zero emissions—doing this in a large-scale way for a period of time, you could actually not just stop the amount of warming and halt the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, but actually undo that damage over time. Basically, all of the climate models that allow us to stay below 1.5, or 2 degrees, even, have some amount of these negative emissions built into them. We do not have a planet that is capable of producing that scale of negative emissions through natural approaches, like tree planting and reforestation—

AZ: Which was a narrative that—

DW: Took hold.

AZ: [Window shade comes down] I’m going to pull this down so you’re not so hot.

DW: Thanks.

AZ: So you can think clearly. We’re being warmed by the greenhouse effect. [Laughs]

A graph demonstrating the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from 1960 to 2021. (Courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

DW: Natural solutions have a role to play. But to really combat the emissions that we’re putting out there, and even dealing with the very hardest-to-abate emissions…. So assuming that we totally decarbonize our cars and our electricity and a lot of other stuff, and just the really hardest—they call it the hard-to-decarbonize, or hard-to-abate, sectors—would require huge amounts of land. Some estimates are as high as like half of the world’s arable land, which we need to grow food. I just think it’s not all that plausible that we do that through these natural solutions, which means we’re probably going to have to be doing it through tech, through industrial processes.

We have that technology today. It’s not some dream. It works. It’s expensive, but we have it and it works. But there has been, for a long time, a real resistance on the climate left to taking it seriously because it is the preferred solution of the fossil fuel business. Because they think, Well, if we just say, “We’re going to suck carbon out of the air” down the line, then we can keep burning it today. That’s obviously an unacceptable bargain, and I understand why many people who are fighting for climate don’t want to think about negative-emissions tech as a result. But ultimately, if your top goal is like, keep warming to 1.5 degrees, you need this tech, and we need to think seriously about it, invest in it, plan on it, start building it out now. Because those models I talked about that allow us to stabilize at 1.5 degrees, they require us to cut our emissions in half this decade; they require us to get to net zero by 2050. That would be an unbelievably rapid transformation of our energy systems.

But even beyond that, they would require so much negative emissions that we would need to be building a plant to do this every day until 2050. We have, all over the world today, one of them. On some level, I guess, I think of my role as being ultimately like just a … I don’t want to flatter myself too much, but just as someone who’s looking with clear, fresh eyes at the whole picture.

AZ: I don’t think that’s flattering yourself. I think that’s the reality. Someone’s got to bring some coherence and clarity to the situation, and that needs data, and it needs emotionality and story attached to that data. I think that’s why your book hit people, why your articles hit people. Throughout the pandemic, you were also reporting on Covid-19; we’re still in it. I was curious if you had an opinion on why we understand the urgency of a response to something like a pandemic, and the vaccine, in a way that we just can’t get our heads around the climate crisis?

DW: I think people are really scared, were really scared, for their own safety and the safety of those around them. I think that that was, in large part, because of how immediate and urgent it seemed. We have a lot of things that actually kill more people than Covid. I mentioned air pollution before. The difference between air-pollution mortality and Covid mortality is large. Cancer is killing more Americans than Covid is; I think heart disease as well. I don’t say that to downplay the pandemic at all.

AZ: Of course not.

“Old threats, we just kind of normalize. I think that that’s an unfortunate predictor of where we’re likely to head with climate.”

DW: But the new threats really terrify us, and you can see that. September 11th is another example. Old threats, we just kind of normalize. I think that that’s an unfortunate predictor of where we’re likely to head with climate, where things probably will get quite a bit worse, but we’ll just learn that that’s where we are, and that it’s acceptable for that many droughts, and those intense heat waves, to be hitting these poor people in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. I think that’s another interesting and important dynamic, that the pandemic hit the wealthy countries of the world first, because it was transmitted, essentially, by the system of globalization. Even within the U.S., it was like, it was New York City that was hit first, and hit worst.

AZ: We got it bad.

DW: We got it really bad. For a long period there, we were the epicenter of the global pandemic. It wasn’t precisely true within China, because it happened to start in Wuhan. But when you think about all the places around the world that really suffered, it’s a lot of the global capitals. While there was some disparity in how poor people, disenfranchised people within particular countries, got sicker and died, when you look at the global picture, most of the death is concentrated in the wealthy countries of the world. In part, that’s also because we’re all older, and the age skew of Covid is really extreme. When you think about…. I don’t know the exact figure for all of sub-Saharan Africa, but I’ve just been looking at the South Africa numbers, thinking about Omicron, the median age in South Africa is 28. There’s just not that many old people in the developing world, which means that the rich countries of the world died at much higher rates than the poor countries of the world.

AZ: It’s like Phnom Penh has very few old people, and for different reasons.

DW: Yeah. With climate, we’re like, “Oh, it’s going to be the poor people who suffer most.” And that means that people like you and me don’t pay all that much attention to it. With Covid, it was people like us who were getting sickest and suffering most and dying, and I think that was a lot scarier.

We did have this incredible, incredible response—I think most Americans, maybe even most people around the world, still don’t appreciate just how dramatic the global intervention last spring was. This is like, more than a billion school kids were out of school for a period of a couple of months there. That is insane. The lockdowns that we lived through weren’t complete. There were still some people going to work and risking their lives, both in genuinely essential jobs and then other jobs where they just didn’t have the power to demand protection.

But even so, the kinds of lockdowns that we had, the partial lockdowns that we had, were unprecedented in human history. As were the government responses in terms of making it mostly okay for most people. In America, the average unemployed person who lost their job because of the pandemic actually had more money coming to them during 2020 than they had from their previous job. That is again, a response beyond the imagining of…. If you had said to someone in November of 2019, “There’s going to be this huge disease outbreak,” I really don’t think that many people would’ve said, ”Okay, well, we’re going to shut down. Everybody’s going to just stay at home, and the governments are just going to pay for them to live for six months.” That would’ve seemed unthinkable. And yet, within a few months of learning about the disease, that’s where we were.

AZ: Not to mention the technological speed of getting the vaccine going. It’s unreal.

DW: I think most people still don’t really appreciate just how fast that happened. I wrote a particular piece about this last December that was called, “We Had the Vaccine the Whole Time.” Literally, the Moderna vaccine was designed within two days of the genome being released, in January of 2020. It was fully designed before the first American case had been identified. It had been put into production before the first American died.

Now, we have to do clinical trials. We don’t want to just inject random stuff into people’s arms. But we knew that the drugs were safe—we knew the vaccines were safe—from early clinical data that came out in May. Even the incredibly rapid, unprecedented in human history, insane speed of development and rollout that we’ve seen with the vaccines, actually could have been considerably shorter. If we had done that, if we had taken that May data and ran with it, and started rolling out the vaccines in, say, August or something, we could have prevented a huge amount of the winter surge deaths that we saw. So it’s possible that even that delay cost a hundred thousand, or maybe even more, American lives.

But there’s all of these responses that were unthinkable before the pandemic. We put them together really rapidly. But I think actually most Americans don’t think that that was … they don’t see it that way. They think of us as—which is also true, having bungled through it, like, failure of leadership from the presidency, which was abject failure, down through local government, and even down to the level of individual citizens where we see all these videos of people getting into fights about masks and now about vaccines. Both things are true.

“Because people are complicated and politics is really hard, no victory is going to be perfect, and that’s really where we are with Covid.”

I think that’s a lesson for thinking about climate. Which is, this is not a “hero swoops in, saves the day, and everything’s fine” narrative; or, “it’s an apocalypse, we’re all going to die” narrative. We’re going to live in the middle. We’re going to fight about the process; we’re going to muddle through. We might end up closer on the optimistic end of the spectrum or closer on the more pessimistic end of the spectrum. But we’re in a spectrum there. It’s not a binary thing. And because people are complicated and politics is really hard, no victory is going to be perfect, and that’s really where we are with Covid.

I mentioned to you before we started recording, I think really important, is Covid actually offered us this huge opportunity. There are some estimates that the U.S. spent $10 trillion on pandemic relief. A lot of that money was just throwing it out the door, like asking for people to take it. We could have done a much better job, not just in the U.S., but all around the world, in directing that money toward greening our economy, toward decarbonizing our economy. Some quite smart, reliable, responsible people who work on this did pretty sophisticated modeling to find that, if we had spent ten percent of what we spent on Covid over the next five years—so it’s, in total, fifty percent of what we spent on Covid—that would’ve been sufficient to totally decarbonize the global economy. And yet, we didn’t. That’s another big-picture thing I think is worth everybody keeping in mind.

AZ: Well, you always seem to do this. You always seem to take this incredibly long view while you deal with the present moment. The piece you just put out on Omicron— which what, you wrote Sunday?

DW: Yeah.

AZ: You must have written it over the weekend, and it’s happening.

DW: Yeah.

AZ: When I was reading it, I was thinking like, There’s so much noise, and you have a platform, and people are listening. So, what are you thinking about when you’re sitting down to write, in terms of a responsible contribution to the conversation? How do you clear out the noise, in a way? How do you make sure that you’re not adding to the noise? Most of your work, if not all of it, results in this long view, while at the same time, this very tangible, present fact. You exist in these extremes, in your work.

“At core, I’m just like a marveling stoner, who’s just like, ‘Wow, look at this saga that’s unfolding,’ and is always pulling myself back to the really big picture.”

DW: It’s funny—that’s a very generous way of putting it. I think it is also, to some degree, an accurate description of my mind, which is, at core, I’m just like a marveling stoner, who’s just like, “Wow, look at this saga that’s unfolding,” and is always pulling myself back to the really big picture.

But when I’m actually thinking about writing a piece, honestly, it’s that old, is it an xkcd cartoon? I don’t remember. It’s like, “Somebody’s wrong on the internet.” That is really my…. I’m like, “No, no, no, wait. Everybody’s saying that it’s good news, that Omicron is less severe. But if it’s only thirty percent less severe and six times more transmissible, that adds up to a lot more deaths. Nobody’s talking about—let me shout this out there.” I am often motivated by that impulse. I’m observing a particular, often elite privileged, but quite powerful, influential discourse, and feeling like there’s some part of it that’s being misleading, or inaccurate, or where the moral emphasis is wrong.

For instance, the last couple of months, I just keep astonishing myself by looking, like a lot of people, just looking at the Covid data on The New York Times website and just being like, “Wow. Still one thousand people dying, every day.” That made September and October of this year, aside from last year’s winter surge, the deadliest two-month period in the entire pandemic in the U.S. And nobody I know, and not really anybody I even see, like, speaking to journalists or writing on Twitter or whatever, is putting that fact front and center. In this period, with vaccinations where they are, with liberal Americans in places like New York feeling relatively well protected—which they are—there are still an awful lot of people dying.

AZ: Yeah. But it’s not as cinematic. We’re not looking at imagery of freezer trucks outside the Javits Center.

DW: I’m trying to be cautious in how I’m thinking about Omicron, but I do think that hospitals-getting-overwhelmed narrative could happen again. And I think we’re very much not prepared for it, in part, because we’ve all mentally turned the page there. Now, I’m not saying that it is going to happen. I think there’s a huge amount that we still don’t know.

AZ: But this week it’s like, holiday parties. There was a holiday party at a friend’s company the other day. Eighty people were there. Twenty people got Covid.

DW: Well, on some level, there is wisdom in an approach to this that says, “If I’m vaccinated, especially if I’ve gotten a booster, an infection is much less meaningful than it used to be.” That is true at the individual level. To some degree, you can say that it’s true at the population level, although I’ve been so astonished that we are here now in the late fall, early winter, and we’ve got sixty percent of Americans vaccinated, something like eighty, maybe even higher, percent of seniors vaccinated—those numbers are a little unreliable. The C.D.C. has been really bad about it. And yet, the ratio of cases to hospitalizations, and the ratio of cases to deaths, is the same that it was before vaccines, last winter.

AZ: Oh wow.

DW: This is maybe a little technical just to even state the problem, and I actually don’t understand what explains it precisely, but given the same number of cases, we would expect to see today, and we are seeing today, the same number of deaths, and the same number of hospitalizations—in fact, more hospitalizations—than we saw before mass vaccination last winter. Which means that vaccines are doing their job; they’re protecting individual people. But first of all, there are enough unvaccinated people that the disease can still kill. And, I think Delta was considerably more severe than we were told, which means that, overall, the effective vaccines and the effect of Delta basically cancel each other out. They fought to a draw.

Last winter peak, we saw two hundred and fifty thousand cases a day, basically. In the Delta surge, we saw between one hundred thousand and one hundred and fifty thousand. So, a little more than half. Last winter, we saw between two and three thousand people dying a day. This time, we’re seeing between one thousand and two thousand. The ratios are exactly the same.

Which means that if you’re thinking about what you owe the society at large, any case actually has the same mathematical relationship to death that it did at a national level, that it did before vaccines. You yourself may feel protected, but because of these complicated dynamics of spread, because of the severity of Delta, because of how many unvaccinated people there are, you getting sick and possibly infecting other people actually represents the same kind of social risk and social imposition that it would’ve represented a year ago.

AZ: Wow.

DW: And I don’t think anybody is thinking in those terms, at all.

AZ: Yeah. It’s kind of bringing these poetic terms to it. I think it was on the Longform podcast, but there was something I heard a while ago—I mean, this is going back a couple of years when you were doing press for that book—where someone was asking about your inspiration to write the book on this interview, and you said, “Well, actually, Twitter, and the stacking of data….” But then, somehow, you’re taking that, and you’re figuring out a way to make it poetic or understandable. So, I want to hear a bit about that from you. Process, basically, and how you’re thinking about these things. Because like what we just talked about—the only way to get an understanding there, globally or in a populist way, is to use, somehow, poetry to make that work.

David Wallace-Wells in 2019 speaking at Climate One, a public forum and podcast series for conversations on climate change and its implications for society, energy systems, economy and the natural environment. (Courtesy Climate One)

DW: Yeah, I think that is more or less what I do. But it’s a little bit of a black box to answer, just because when I see those numbers, I’m marveling at them, in addition to just tabulating them. I wrote this long piece about air pollution a couple of weeks ago—it came out in the L.R.B. [London Review of Books]. And the headline was, “Ten Million a Year.” I actually had been working on this piece for a long time, in part because I didn’t entirely know what to make of the fact, given my background on climate, that the mortality toll of air pollution is considerably bigger than the mortality toll of climate. It was a mind-bending experience to go through. But basically I just spent a couple of years going around being like, “Fuck. Ten million people a year. Ten million people a year.” And that number meant something to me, emotionally, in a way that…. A lot of people deride statistics, but I just saw the stats and found them—I mean, you said the word “poetic.” I just think “human,” “majestic”—

AZ: Full of wonder. Yeah.

DW: Yeah. Really felt like there weren’t all that many people who had the same disposition, or perspective, writing in these areas. I felt that really keenly with climate. Where it used to be for so long, people would talk about climate journalism and be like, “Well, we can’t talk about the stats. We got to find someone. We got to find a family that got displaced because their house flooded in rural Louisiana or whatever.” Frankly, I find those stories kind of boring. They all feel very paint-by-numbers, especially like in the newspaper format, which is how they often appeared. I was just like, “We’re not talking about transformation of a scale where like, there are going to be some tragedies. We’re talking about ten million people a year.” That’s a Holocaust every year. Nobody’s talking about it in those terms.

AZ: Even that’s hard to understand. But when you go to Birkenau or something, and you see the piles of shoes…. How we make meaning through symbol, and through story, is what makes understanding. And I think that that’s the thing. It’s like, ten million. You’re struggling with that, and then you go, “Okay, how do I make other people think, Ten million? What makes that work?” Because there’s such a delta of understanding there.

DW: Totally. And it’s funny, because I often, in talking about those stats, use the Holocaust comparison. And I often get people being like, “How dare you!” And I’m like, “My grandparents were Holocaust refugees!” I don’t want to say that gives me exclusive access, but I think I could use that as a comparison point without offending people.

AZ: Yeah.

DW: My grandfather’s entire family was incinerated in the Holocaust.

AZ: You carry the generational trauma, ancestral trauma—

DW: Totally. My mother is very much dealing with it still, today.

I do think that finding the right comparison point there is really useful and powerful. One of the things that has been really interesting to watch unfold with Covid, is conservatives, who were reluctant to embrace restrictive measures early on, were very eager to make comparisons, and were like—

AZ: Totally.

DW: “It’s the flu.” They were wrong. The infection fatality rate is higher than the flu, and the infection fatality rate—which is the proportion of people who get sick, who ultimately die—that’s misleading, because when it’s a new disease, it spreads much more quickly, many more people get it, so it’s not a total picture. But there was no real effort on the other side to contextualize the numbers usefully.

AZ: Make facts touch humanity somehow.

DW: Yeah. There’s been a lot of commentary since, that like, we didn’t see enough dead bodies. You mentioned the morgue trailers or whatever. I think that was one of the few…. We didn’t even see those people, but that was one of the few illustrations of mortality that—

AZ: Made visible, touched.

DW: Yeah.

AZ: Speaking to the Holocaust, partly how it was kept a secret for so long was, those images didn’t travel for quite a while.

“There are all these things that we blithely accept, which are really, really horrifying, immoral, grotesque, cruel. And climate change is probably Exhibit A.”

DW: But it’s interesting in the sense that we basically don’t believe that we are capable of that kind of moral monstrosity anymore. Whatever we say about Donald Trump, and however awful his regime was, we don’t think he’s going to…. I mean, I didn’t think he was going to be killing millions of people like that. Our civilization has just moved past that.

And yet, there are all these things that we blithely accept, which are really, really horrifying, immoral, grotesque, cruel. And climate change is probably Exhibit A. We literally, with our daily lives, are poisoning the future of the planet. We are wealthy today because we, and those who came before us, poisoned the planet and poisoned the future. And the entire structure of global power and wealth is the result of the scarcity of this energy resource, hoarded by the countries that we now call the Global North, and used, and producing, pollution that is ultimately toxic to the lives of people living in what we now know as the Global South. That’s not—

“We literally, with our daily lives, are poisoning the future of the planet. We are wealthy today because we, and those who came before us, poisoned the planet and poisoned the future.”

AZ: That’s just fact.

DW: That’s just fact. There was no history of economic growth before the discovery of fossil fuels. Now, the history of economic growth is more complicated than the simple input of fossil fuels, but it played a huge role. That energy source has basically not been used by the Global South, which, today, is already poorer than it would be without climate change—by some measures, as much as twenty-five percent.

AZ: Wow.

DW: They’ve lost twenty-five percent of their growth over the last couple of decades because of climate change, and the gap is only going to widen.

AZ: I don’t even think we think about that.

Arctic sea ice is now declining at a rate of 13% per decade. (Photo: Andreas Weith)

DW: Yeah. There’s this whole narrative that’s like, “What happened to Africa in the sixties?” There’s a right-wing narrative that’s basically like, “They got independence and they couldn’t govern themselves. So it’s this problem of governance.” I’m not here to say that there aren’t problems of corruption in African government—there are, definitely. But also, we were like, essentially dumping toxic waste into their world, not dealing with the pollution here in the same way, and watching their famines become more common, their droughts become more common, and assuming that it was just natural, that it was some feature of their culture or their civilization, which doomed them to that kind of suffering. And not because it was essentially a story that we had written, or in part written, by producing fossil fuels. In part because we don’t want to acknowledge that we have any kind of moral responsibility to the…. That’s where we all flip past the pleas on TV when we see starving kids. But also because it makes us feel shitty about the comfortable lives that we have, if it really did come on the back of billions of people living elsewhere in the world.

A polar bear showing signs of malnourishment due to the melting of ice caps, which prevents it from migrating to an area with more prey during the summer months. (Photo: Andreas Weith)

AZ: You wrote this New York magazine article that spawned the book in 2017, and I was thinking back to that time, especially here in New York, where we both live. And you definitely faced some heat on the other side of it, and you wrote a book in the context of how polarized and hyperbolic everything was. We mentioned Trump. You wrote this with a canvas, and in an arena, that was so crazy hyperbolic at the time. But somehow you managed to aikido that. You were like, “Well, let me maybe use fear as a weapon for good, because they’re using fear as a weapon for maybe not so good.” That’s, at least, how it felt in a way. It was like, “Finally.” [Laughs] You know what I mean? Were you thinking actively about that? Were you like, “How do I take this moment, and this zeitgeist, and this feeling, apply it to the climate crisis…?”

DW: I think I was responding at a subconscious level more than a conscious level. I mean, I definitely was scared. When people ask me how I got turned on to climate and climate alarm, in particular, I often say, “In the months after my father died, I started seeing a lot…. I was keeping an eye on the future news from—”

AZ: You lost your father in 2016.

An image depicting methane leaking through cracks in the Arctic ice cap, a phenomenon which contributes to global warming. (Courtesy NASA)

DW: Yeah. I was seeing some more scary news about climate. Trump got elected. And then a couple of weeks after that, there was this string of days in the Arctic where the Arctic was like forty degrees warmer than it was normally. And I had a panic attack. I thought to myself, This story that we’re living in is really scary. And I felt that I had not been told that story honestly. I had to discover it because I was reading some relatively obscure academic papers.

Now, that’s not to say that nobody had raised the alarm about climate change before. Of course they had. And we didn’t listen, and I was one of the people who was not listening. But one of the reasons that that message hadn’t gotten through in the way that I think it really has over the last couple of years is that there were a series of conventions around climate communication, and climate storytelling, that were really restricting the canvas, essentially, to more optimistic possibilities, and not really wanting to talk about the scarier end of the spectrum.

“If science says something is possible and it’s scary, I want to know about it. I don’t want to have it shielded from me.”

Just on a storytelling level, I was like, There are things that are possible that I, as a well-informed person, didn’t know were possible, and I think that that’s a communications crime. If science says something is possible and it’s scary, I want to know about it. I don’t want to have it shielded from me. Secondly, I was someone who became kind of a climate person because of that fear. I didn’t trust anyone who told me that fear was a counterproductive messaging tool. I knew, also, it wasn’t for everybody. I knew there were other ways to tell the story; I still feel that way. But I knew that, at least, in this case study of one—me—I had had an awakening out of fear. I assumed that there were other people like me, and maybe they numbered in the thousands, maybe they numbered in the millions, but they were out there.

And I looked back at this history of environmental activism, [and] activism in general, and I just saw all of these instances where fear had worked. I thought, If it’s true that this is scary, if I know that I was activated by fear, and I know from analogies in the historical and the recent past that fear can work, what possible argument could there be against using it? So my first impulse was really like, I got a story that isn’t being told, and is a really big deal. But thinking through the strategic implications of that, I thought, Whatever reluctance people had towards fear-based messaging, whatever skepticism they had, was really blinkered.

Climate activist Greta Thunberg outside the Swedish parliament building at the first School Strike for Climate in August 2018. (Photo: Anders Hellberg)

I didn’t know that I would be surfing a wave of alarmism when I started out. I think a lot of that was coincidental, but a lot of it just is, probably a lot of people were picking up on what I was picking up on. When Greta goes outside of the Swedish parliament with her sign, all by herself—a lonely, literally friendless teenager, no platform at all—and starts talking about how big the gap is between what scientists say is happening and what politicians and journalists are saying is happening, she had an enormous response. She started doing that in August of 2018, by January, she was like the star at Davos.

AZ: Yep.

DW: From total obscurity, not even surrounded by friends, to, effectively, like, the cover of Time magazine, in four months time, that just tells you how much audience appetite there was for this very direct—

AZ: Yet you caught all this flack from climate journalists—specifically, Eric Holthaus and Chris Mooney—who were not totally gracious in welcoming you to the climate journalist club. Why do you think that is? I don’t mean to just call out those two people, but you have mentioned them in things before. Who are, by the way—

DW: Good journalists.

AZ: Great journalists. Why was there this sort of like…. I mean, was it classic schoolyard stuff? Like, who do you think you are? We’ve been here for a minute. What was it?

DW: I think it’s complicated to understand the psychology of that pushback. I think of it in terms of two different…. There were sort of two different schools of criticism. And this is, just to be clear, really talking about this article I wrote in 2017, which was explicitly about worst-case scenarios, and was really, really scary. The book is also quite scary, but—

AZ: The article that preceded the book.

DW: Yeah. The book that came out of the article was—

AZ: With an amazing image, by the way. We just note what an image you illustrated that with, which we’ll put in the podcast.

DW: The book, it’s quite scary. It looks at a range of scenarios that are more likely not worst-case. To some degree, I guess that’s a response to that criticism. But I think of the initial criticism as being of two different kinds. One was that I was being inaccurate with the science, and the other was that it was irresponsible to talk about worst-case scenarios at all. I think that a lot of people raised the first objection really meaning the second. But we did, I think, a pretty good job of quite quickly annotating the story I’d published, showing where everything came from. There are still some things, as with all of these papers, they’re not going to be precisely accurate—

AZ: Your book I’m holding here has seventy-seven pages of notes, the paperback.

DW: Yeah. I think it’s always important to keep in mind with this stuff, it’s like, we’re not talking about a study, we’re talking about a literature. And many of those studies are going to be revised. Some of them are going to be revised to be, Actually, we were too worried about that. That’s going to happen. The recent history shows there’s much more like, We were not worried enough about it, but there’s going to be some stuff that gets debunked and that’s how science works.

But when you take, in totality, the full literature on what this high-end emissions scenario that the U.N. said was possible would mean, it was really terrifying. I was sketching that out in an unapologetic, fear-mongering way. And it was not the way that any of these people did business. And the reasons for that are, as I say, complicated. I think there was some new-kid-on-the-block stuff to it. If I was writing that same piece now, I’m sure I’d get more…. I mean, the culture has changed. We’re more receptive to alarmism, but also just, my position has changed, so—

AZ: This is before Greta got up and yelled at everyone.

DW: Yeah, and before anybody knew who I was. I think that the reception would be different now.

But I think there also was this quite baked-in conventional wisdom about climate communication and messaging, which is that scaring people doesn’t work, and you need to inspire them instead. You need to be clear about the stakes, but you also need to be clear about the opportunities, and that those things need to be balanced. And that anytime you’re talking about really high-end scenarios, you’re essentially out of balance and out of whack. Because we can expect that humans will do something, those curves will bend, and we’re not going to end up in what looked, at the time, to be worst-case scenarios.

AZ: That’s a big assumption.

DW: Now, at the time I thought it was a big assumption. I thought it was bullshit, because I thought, I look at these trajectories, and they’re all—we’re not doing anything to bend the curve. Emissions are going up. Maybe we won’t get all the way to this one particular scenario that that article was based a lot on—it’s technical, but it’s called RCP8.5. Maybe we’re not going to get all the way there. But like, can we count on our not getting there when we’ve done so little to this point? That seems like a big bet. And given the stakes, let’s just be clear about what the stakes really are.

AZ: Yeah.

DW: I now actually feel a little differently about that. I think that it’s very unlikely that we get to that emissions level. I think in part that’s because of the changes that we talked about, where renewables have gotten much cheaper, politics have changed, corporate politics have changed, all that is really different. But I also think some of it was, honestly, a problem of scientific communication at the outset. Which is to say that, that scenario—and I’m sure your listeners will be so bored hearing me talk about this detail—but that scenario assumed something like a five-fold increase in the use of coal over the course of the twenty-first century—

AZ: Which shifted.

DW: Maybe that was defensible as a worst-case scenario when the scenarios were first being cooked up in 2007 to 2012 or whatever, because at the time China had gone through this huge coal boom. And you could say, “Well, everybody in the developing world’s going to do the same.” It was defensible, I think, as a high-end scenario. But then it was messaged as business as usual. That was the language that was used. “This is our business-as-usual trajectory. This is what’ll happen if we don’t implement any policy at all.”

I think that that was, at the time, in ways that I didn’t understand, misleading, in the sense that it required the world to really turn away from any climate action at all. While I was not confident that rapid action was going to take place, I would’ve told you, if you asked me, in 2017, “If you imagine the course of the twenty-first century, do you think something’s going to be done?” I would say, “Yes, something is going to be done.” And doing anything means that RCP8.5 is really unlikely.

Now, that’s not to say that some scary things are not quite likely; some scary things are not baked in. As we talked about at the beginning, they absolutely are. But I do think that there may have been also something that those journalists and other scientists understood about the basic plausibility of that scenario that I didn’t, that allowed them, or led them, to be more critical of me than I would’ve been, to someone else doing the same thing at the same time.

It is one of the things I think about a lot, like, if the last major U.N. report on this had not used RCP8.5 as its high-end scenario, but had used RCP6.0, which is a slightly lesser one, where would that have led me? Those scenarios are really scary. I would’ve written quite a similar piece, and really would’ve written a quite similar book, but it’s also possible that that very initial pushback might have been lighter, because people would’ve considered that a more likely future.

AZ: Right. And I mean, you engaged with other scientists.

DW: Totally.

AZ: Michael Mann, the [lead] author of the Hockey Stick graph…. Who was critical, but you then used that to collaborate, and to have understanding further. Was there anyone in particular that really had a major supportive effect on you at the time?

DW: Oh, many.

AZ: You felt more supported than criticized at that moment?

DW: Yeah. The scientist-scientist who I’m probably closest to, who was, I think, very helpful to me then, and very supportive then, is a guy named Michael Oppenheimer, who’s at Princeton, but has been involved in the I.P.C.C. We did a bunch of events and podcast/radio stuff together. He was not exactly where I was, but he said, “You know, the science says these things are possible. We should be talking about them. Maybe we should also be talking about them in terms of probabilities. We don’t really have the math to do that, but it’s worth airing them.” And I think that’s really true. If the world’s scientists are saying, “This is plausible enough to model,” then we need to be worrying about it.

Cover of The Lorax by Dr. Seuss. (Courtesy Penguin Random House)

More recently, I’ve spent a lot of time talking to Marshall Burke and Sol Hsiang and Drew Shindell. I’m now quite plugged into that world. In general, the picture is brighter. Most people believe progress is being made, but we waited too long, and we’re moving too slowly, to avoid levels of warming that we were quite comfortable and confident defining not that long ago as unacceptable. And we’re now heading for them, almost inevitably.

AZ: You were in a conversation about a year ago with Ezra Klein and Leah Stokes. At the end of it, you were asked to recommend a book, and you brought up The Lorax. I was curious why that book is relevant to you. What is it about The Lorax that’s relevant in this moment?

DW: The reason that I brought it up is that I’ve been thinking a lot about the way that our relationship to nature is being changed by climate change. What I mean by that is, for a long time, really, since the industrial revolution, Westerners have regarded the natural world—which is a conceptual idea that only came about during the industrial revolution—as a retreat, an escape, a source of solace and comfort, but also of perspective and grounding, a reminder that we are guests on this planet, as well as stewards.

AZ: We’re of nature.

DW: We are of nature, not above nature. Even as someone who spent my whole life living in New York City, I have a lot of those same values. Like, I do feel that the natural world is awesome, in the original meaning of the word, and perspective-giving, and essentially, in that sense, a model for how we should live here on this planet.

“We are of nature, not above nature.”

In the climate context, it has also been an incredible friend to us, in the sense that all of those trees, all they’re doing all day long is eating up carbon, and putting out oxygen for us to breathe. They’re literally taking our pollution, and feeding us clean air. We have only as much warming as we have now because they have been such efficient allies in the fight against climate [change]. About half of all of the emissions that we’ve ever put up into the air have made their way into the atmosphere. The rest of them have been absorbed by trees and oceans. That means that, in the present moment, we may not just be turning to nature as a source of perspective, but also as a backup plan. All of the science says, we really can’t be counting on that for much longer, at least at the levels that we’ve seen to this point.

“We have only as much warming as we have now because they have been such efficient allies in the fight against climate [change].”

So because we’ve done so much damage to the atmosphere in general, through warming and through direct emissions and pollution, almost all scenarios suggest that this carbon-uptake mechanism is going to become less efficient going forward. In some cases, especially through wildfire, many places that have done an enormous amount of work saving us from ourselves, like the Amazon, are not only going to become less efficient in taking carbon out of the atmosphere, they’re going to start being sources of carbon, which means that they’re going to go from being our friend that is so good to us—that it shames us to be a better person—they’re going to go from that, to being our enemy. They’re going to be a source of ongoing, in some cases uncontrollable, emissions that are going to make our future worse and our climate situation darker. That is a really profound shift.

“A lot of the conceptual models that we’ve inherited from past generations about nature and our relationship to it are going to have to be, at the very least, remodeled.”

I don’t know how long it will take us to process it. I don’t know how complete it will be. We may choose not to process it. We may choose to continue thinking of the natural world as this majestic, untouched, better-than-us system. But within a few decades, it’s quite possible that many of these largest forest and rainforest systems are going to be working against us, rather than working for us. In the book, I talk about it. I call it—sometimes, I think, “war machine” is the best…. We’ve been arming this system for a really long time, and it’s about to go to town. I don’t really know where that leaves us, but it means that a lot of the conceptual models that we’ve inherited from past generations about nature and our relationship to it are going to have to be, at the very least, remodeled.

AZ: Beginning with Enlightenment.

DW: Yeah.

AZ: What’s a terrarium? You gotta think about these things, in terms of when that really shifted. Did enlightenment create the climate crisis, in many ways?

“We didn’t even really think of the ‘natural world’ as the natural world until we started despoiling it.”

DW: It is the case, though. We didn’t even really think of the ‘natural world’ as the natural world until we started despoiling it. The category, it’s like the parts that we haven’t touched yet. Although, as we know, we now think of a lot of things as natural that are not at all natural. Like, we bulldozed [American] Indians out of all of the national parks. There’s a lot of engineering going on there, too. In places like the Amazon, there were civilizations there in the past. It’s not like perfectly, perfectly untouched. On the other hand—

An area of the Amazon rainforest that was decimated by forest fires in 2020. (Courtesy Amazônia Real. Photo: Bruno Kelly)

AZ: Nothing is.

DW: Nothing is. But we want to believe in the… not just the moral virtue of untouched nature, but also it as an asset. We may soon be getting to a place where like, yes, trees are good, but, like, if we’re planting them at an industrial scale and managing them like a factory farm, is that nature?

AZ: No. We know that now.

DW: Yeah.

AZ: So you had a child while you were writing this book. Which, to me, is amazing. Having a few myself, I can understand the cognitive shift of before and after becoming a parent, and having lost a parent just before that, which opens you up, I imagine. I haven’t, but my wife did at a similar time that you went through it, and I know that there’s a kind of being that I don’t understand quite yet, because I haven’t experienced that. But being this present with life cycle—someone passing, someone coming—and you’re writing this book, how do you think about raising a family during an ecological crisis? And how do you think about your child’s future and the planet you brought them into?

DW: I think there are a couple of different ways of thinking about it, and I can’t say that I have a perfectly coherent, or even defensible, perspective on it. I think, if I were to sum it up in general, it’s something as crude and reflexive as, You gotta live your life.

“I don’t think that global warming is likely to proceed at a level that makes life miserable for my children, or indeed, most people on the planet.”

Now I do think, reflecting on it more, it takes me in a bunch of different directions. I guess the first thing I would say is, I don’t think that global warming is likely to proceed at a level that makes life miserable for my children, or indeed, most people on the planet. I think that there is going to be an enormous challenge of responding to this crisis. It will introduce a lot of pain and suffering, but that alongside that we will adapt, but we will also normalize. We will come to accept conditions that are much more brutal, climate-wise, than the ones we live in today, without feeling like the world has ended. That’s true globally, I think.

I think there are going to be regions, like the Sahel, that grow, that are truly uninhabitable. But I think for the most part, people are going to continue living their lives with more difficulty in them. I do think that the air-pollution point is really illustrative there. The W.H.O. says, between 2030 and 2050, climate change could get so bad that 250,000 people are going to die every year from its various effects. That sounds really bad, which it is. But ten million people are dying right now from air pollution. I’m not trying to say that nobody noticed. Like, the people who are dying are noticing. The people who are getting—

AZ: It’s staggering though.

“Our capacity for normalization is so large. And it is especially large in wealthy parts of the world by privileged people like you and me.”

DW: It’s so large. Our capacity for normalization is so large. And it is especially large in wealthy parts of the world by privileged people like you and me. When I think about raising my daughters, the lesson that I want to impart to them, to the extent that I can impart any lessons, is that the life of people living elsewhere who have less, who are suffering more, is equivalent to your life. You cannot just look away from five hundred thousand people on the brink of starvation in Madagascar, and just be like, “Oh, that’s some backward corner of the world,. That’s just what life is like there.” You can’t just look away at a billion Indians facing really intense climate impacts in the decades ahead. Or, all of those people living in sub-Saharan Africa whose agricultural yields are already falling, who are already struggling, in various ways. These are all humans whose lives are meaningful, and whose suffering is, in part, a reflection of your prosperity. Those things are connected. There are other things at play, but those things are connected. It is a factor. And to just try to inculcate a moral imagination that is global, as opposed to extremely local, or tribal, or national. That’s hard. I can’t say that I see the world that way all the time—

AZ: Of course not.

“To understand the basic value and dignity of people living elsewhere is, I think, a really, really, really important lesson.”

DW: But to understand the basic value and dignity of people living elsewhere is, I think, a really, really, really important lesson. I think it’s the lesson that we need to learn as a globe, so that if we have a hundred million or two hundred million climate refugees, we don’t just think, Stop clogging up our country, you brown people. We think, Let’s help you.

I think it’s important on the individual level, too. What the world looks like thirty years from now, fifty years from now, eighty years from now…. I don’t want to sound too optimistic about any of this, but I also think it’s really important to keep in mind, like, it’s really hard to project the future. We can’t really see it. We tell ourselves we can, we model it in this way and that, but like, what’s the world going to be like in 2080? I think I have a pretty good sense of what the global temperature is going to look like. I think that means I have a pretty good sense of what some climate impacts are going to be like. But like, does New York City have a sea wall? I don’t know.

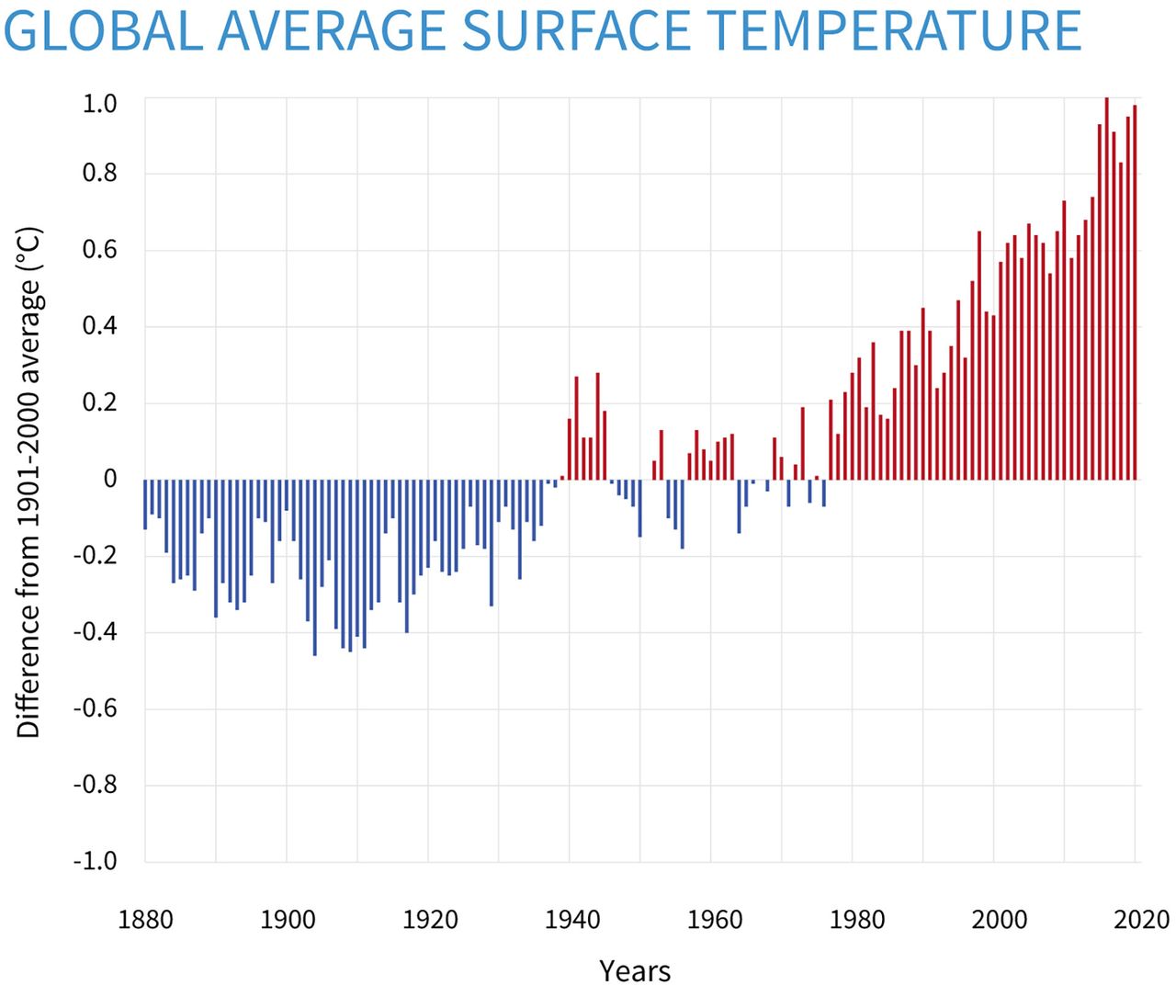

Graph demonstrating the increase in global average surface temperature from 1880 to 2020. (Courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

AZ: Hopefully.

DW: Well, there are some arguments against it, too. But I think probably, we would be better off with it, yes. Is today’s coastline of Bangladesh totally uninhabited? I don’t know. But a disruption like that, while tragic and horrifying, if you imagine it playing out—is also a positive adaptation. So when we talk about a hundred million, two hundred million people, maybe even—the U.N. says as many as a billion climate refugees by 2050, which is as many people as living today in North and South America combined—on some level, that seems horrifying. And given the geopolitics of the present, it is really scary.

On the other hand, it would mean people relocating from places that are bad to live in to places that are better to live in. That’s what that movement would mean. We don’t look at Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia and going to Western Europe and the U.S. and thinking, That was a horror. I mean, it was that. But it’s also like, well, those people found some better lives, and that’s probably going to be a part of the story with climate, too. What worries me most is our capacity for normalization, our capacity to dehumanize people who are living elsewhere, especially when they’re suffering.

“What worries me most is our capacity for normalization, our capacity to dehumanize people who are living elsewhere, especially when they’re suffering.”

AZ: But what gives you hope?

DW: Is like, all of that’s variable. All of that’s to be engineered and to be determined. The climate conditions are going to make things hard. They’re not just going to make things hard in terms of hurricanes and droughts. They’re also going to make it hard because they’re going to teach us that the world is full of scarcity and difficulty. And when we have that idea, we tend not to be very kind to one another. That’s, I think, really likely to be bad news on climate.

But, while I do have a pretty bleak baseline, I also think that we’re doing quite a lot to bring ourselves into the range of that baseline. I think that we may end up quite close to what I think of as a best-case scenario, or what I used to think of as a best-case scenario. And above all, that’ll be an amazing accomplishment. We dug ourselves into a horrible hole and we didn’t manage to get all the way out. But we didn’t drown in the water at the bottom of that hole, either. So, we’ll see.

AZ: I guess we’ll have to just continue reading what you write to know what the hell’s going on.

DW: Yeah, and like, check back in fifty years. Who knows?

AZ: Exactly. [Laughs]

DW: This thing in particular, this fact in particular is really, really hard. This set of facts. The future is going to be grimmer than we were willing to accept up until even a few years ago, and grimmer than our parents and grandparents would’ve recognized as even possible. But it’s also going to be, I think, better, more comfortable, more stable. And as a result, ultimately, relatively speaking, more prosperous and more just than most people looking at it would’ve thought was likely a couple of years ago.

Now, how you process those two really divergent facts is kind of up to you and your emotional temperament. You can probably hear it coming through the way I’m talking now. It’s like, for all the stuff I’ve written about, for all the stuff I talk about and think about, I actually am, temperamentally, an optimistic person.

AZ: You just had to wait around to hear that. [Laughter] If you’re still here, good for you.