Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Christian Madsbjerg. (Courtesy Keller Center. Photo: Sameer Khan, Fotobuddy)

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Today in the studio, I’ll be speaking with Christian Madsbjerg. These days, Christian writes books and screenplays. He teaches human sciences and social theory in New York. He also co-founded ReD Associates, which is a strategy consulting firm that takes an interdisciplinary approach to advising big companies through a human-science approach to problem-solving.

Welcome, Christian. Thank you for joining us.

CHRISTIAN MADSBJERG: Thank you for having me.

AZ: So, you’ve spent the last twenty or so years observing human behavior and identifying change. I think right now a lot of people feel a sense of anxiety and confusion. I’m curious about how you, personally, feel about this moment in time. Are you feeling the sense of anxiety and confusion?

CM: I’ve been trying to think about my own emotional state about what’s going on. The best way I can describe it is directionless panic. It’s a little bit like a horse that’s stung by a wasp. It’s moving all over, but it doesn’t really know why. I think the relationship I have to technology, I think climate change—I feel it’s absolutely necessary to understand this and do something about it, but I have the faintest clue about even where to start. I think if there’s an emotion that defines the times, it’s directionless panic.

“If there’s an emotion that defines the times, it’s directionless panic.”

AZ: There’s a German word for that.

CM: Yeah. Scheuer is the German word for it, which basically means… It’s a little bit like a child that’s been hit by adults. They’re afraid of being hit again. That’s the feeling I get by observing the world. That’s, I think, my emotional state right now.

AZ: And it’s not just about politics.

CM: No, no, no. Politics is just a residual of it. It’s pretty general. I think all of us feel it. I mean, there might be bubbles [of people] that feel quite confident about everything, but I think most of us feel uneasy, and I certainly am.

AZ: Yeah. And you’re writing a comedy during this time?

CM: Right, right.

AZ: You’re writing a comedy about immigration. Tell me a little bit about why you chose immigration as a subject—how you came to trying the endeavor of writing screenplays.

CM: I’ve kept a notebook for twenty years. In order just to sustain sanity, being in big corporations, or spending time in big corporations… It’s not just corporations. It could be academia. It could be anywhere. The kind of nonsense you have to listen to is soul-crushing. So, to deal with it, I’ve had a notebook, and basically, written down the kind of stuff that I heard. I just observed it carefully, in order to stay sane.

I then took that notebook and I showed it to a comedian. He said, “Are you kidding me? This is amazing.” Basically, it’s the observation of twenty years of the kind of bullshit that people say, and the easy answers people accept, and the prepackaged notions that nobody thinks about that you have to live with if you have a thought in your head.

So I took that notebook and made it into a story about someone—I had to find a character that was someone that was stuck and had to listen to it. So, I, of course, thought about visas. In America, if you have a H-1B visa, you are connected to a company that grants you that visa. Otherwise, you have to get a new visa. So, if you are here on an H-1B visa, and you want to stay, you just have to take the nonsense.

It’s a story about a bright Indian engineer that comes here—because his kid and his wife likes being in America, he has to be here. He just gets taken through the constant bullshit of corporate America, the whole TED Talk sort of marketing nonsense that, you know, one has to do if you work in a big corporation. It’s just a way of exposing [some] of the things I’ve heard over time.

Some people say it’s funny. It’s not punch—set up punchline. It’s just observations, and it’s only funny because it’s true.

AZ: I can’t wait to listen to it and to read it, and to see it. I think that using that conceit of the immigrant on an H-1B visa actually relates to everyone, because when you’re working with corporation as a vendor, as an employee—you are, in a sense, owned, and corporations definitely use that, in a way, against you to sort of diminish the self, on some level. Did you see a lot of that as you were moving through corporations, and consulting?

CM: Yeah. You got to do what one does in those situations. It’s particularly sick in marketing, where people would say things like, “You have to surprise and delight your customers.” That’s something that people say a lot. They’re not surprising, and they’re not delighting at all, and everybody knows so, but they keep on repeating that. People go to workshops where nobody works. They write memos that are not thoughtful, or at all interesting, or even read.

It’s this tornado of constant new words that you just have to accept, and particularly if you an H-1B visa, you’re just, you know… You will be kicked out of the country if you don’t accept. So, you play along with it, and it crushes your soul.

Sensemaking: The Power of the Humanities in the Age of the Algorithm (2007). (Courtesy Hachette Books)

AZ: Yeah. You discuss the idea of breaking the spell that’s been cast on us, whether it’s any corporation, or particularly within the Valley—that you’re encouraging us to be circumspect of these companies. In particular, at the end of Sensemaking, your latest book, you talk about Steve Jobs saying, “This is going to change everything,” which is sort of the big trope of the Valley. What do you think about big categorical statements like that, like, “This can change everything?”

CM: Yeah. Well, my question is, everything? Really? Will it change our relationship to our kids? Somewhat. But is it really the most important thing in the world? I’m not so sure. So, even the biggest technology innovations of Silicon Valley—that have been amazing, in many ways—are not changing everything.

I showed my grandmother my iPhone, and I said, “Look at this thing, what it can do. It’s magical.” She said, “Really? Is that what you have? I mean, in my lifetime we made commercial flight available. We made diapers you can throw out instead of having to wash them. We made modern agriculture so that billions of people can be fed.You know that phone is based on the back of investments we made in the ’60s.” So, really, is that the biggest thing in history? No. Maybe, actually, there’s less innovation now than there was in her time. So, this whole thing about, “This changes everything,” you know, I just don’t buy it.

“Even the biggest technology innovations of Silicon Valley—that have been amazing, in many ways—are not changing everything.”

AZ: I think that’s a really healthy perspective right now. I think that a lot of people are adopting this realization that maybe this wasn’t so good for us. I’m interested in what you think about what occurs when one does break that spell. How do they begin to see the world?

CM: Sometimes ideologies break down, because they just don’t explain what they used to explain. I think something happened when Mark Zuckerberg sat in front of the congressional panel and had to explain what on earth happened to our democracy. Suddenly, it was the end of an era of social media making the world better. It’s still making the world better, in some ways, but it’s also something else.

I think in the food industry right now, they’re realizing that sugar, sweetness, is delicious, but it’s also dangerous, and maybe we ought to interact with both “delicious” and “dangerous.” If you talk to customers of big consumer packaged goods companies, particularly in South America, they are less … they are a little bit more concerned about, you know, what it was before. Suddenly, there’s a crack where you can start thinking a little bit about what’s going on.

I think there’s an opening right now, particularly around technology, where it might not be possible to explain all human intelligence with algorithms. Data might not capture the entire human soul. There’s questions like that, that we couldn’t really ask five years ago. That’s why I wrote the book, because I was just desperate. People really thought that AI was better than human intelligence, which is just ridiculous.

And even if it was, we’re still humans. We still need to engage with the intelligence we have. We still need to do things in our life. I think, sometimes, these openings happen where people start challenging the ideology, or the assumptions, that they have.

AZ: These openings might provide kind of a restored sense of agency. Because what’s happening is, we feel powerless. Why is that? Why do we feel powerless?

“Apparently everything has to be ‘agile’ right now. In corporations, that’s all they talk about. What about slow? What about, sometimes you need to slow down and think about things?”

CM: Well, have you tried to go up against an ideology? Let’s say you go to Silicon Valley right now and you say, “Does everything have to be ‘agile’?” Apparently everything has to be “agile” right now. In all corporations, that’s all they talk about. What about slow? What about, sometimes you need to slow down and think about things? Maybe everything can’t be fixed by, you know, two-hour sprints, or whatever they call it now. They don’t understand what you’re talking about.

AZ: Yeah. The idea of speed and slowness… One of the reasons I wanted to have you in here is I had heard you speak once and say that every sentence read or written is on trial. Am I getting that right?

CM: Mm-hmm.

AZ: What’s required of trial, in a way, is time.

CM: Mm-hmm.

AZ: So, you read quite slowly, but you probably draw much more than most people can draw. How have you integrated slowness into your own philosophies in your life, and your approach to work?

CM: I don’t do many things at the same time. I read. Reading is just essential to people to [be able to] think. The slogan that you talk about, which is that every work needs to be on trial for its existence… If you have that as a basic way of looking at the world, you have to scrutinize a whole lot. That slows you down. It means you can’t handle sixteen things in your life. You can only handle a few.

“Sometimes you need substantial amounts of time where all you do is just reflect in a cloud of all the thoughts you have.”

Also, it means you have to have longer periods of time to think about the same thing. I rarely do anything that [takes] less than four hours. So, in a day I can do two things. That’s also a lot. I mean, you think about doing two things as more than it used to be, and all I can handle. I think, also, I need a lot of time with my own thoughts. You spend a lot of time with other people’s thoughts. Hopefully there are listeners now that spent time with our thoughts. But sometimes you need to be alone with your own thoughts. How often are you really?

If you look at the subway, if you look at people on airplanes, if you look at times when you really are on your own, everybody’s listening to podcasts. That’s lovely, and I do it myself, but sometimes you need substantial amounts of time where all you do is just reflect in a cloud of all the thoughts you have, in order to sometimes land at creative things, or important insight about what’s going on in your life, or around you, or at work, or—

Madsbjerg's Punkt cell phone, designed by Jasper Morrison.

AZ: I imagine this is one of the reasons you don’t use a smartphone. You came in here with just a phone. It’s a beautiful object to use. How has that shift from a smartphone to this “dumb” phone affected your life?

CM: A whole lot. Like, much more than I thought. It’s interesting when you get a simple phone back. You remember the time when that was the case. You have at least a week where you have almost the addiction really—getting rid of the addiction—and you constantly grab for the phone in your pocket. Really, what you’re doing when you grab your phone is checking emails, that you could do, you know, four hours from now, and you know, news that we already know what’s in there. Sometimes it’s important if, you know, Liverpool Football Club is playing, or something like that, but in general, it’s not so important. So, maybe you can do emails twice a day.

What happened to me is that it clarified my head. I could think better. I suddenly started mulling over things that I didn’t do before, that made me way more effective. Like, way, way more effective. I’m not into, sort of, “digital detox” or any sort of thing. It just doesn’t work for me. It’s fine if it works for someone else but, for me, it doesn’t work to have that sort of intensity of information in my life.

AZ: Yeah. It’s hard to be open in that state.

CM: Yeah.

AZ: We also don’t enjoy being in a state of doubt, which is something you talk about a bit in your books and in your other writing. What happens when we force ourselves out of that state? How does that shift us?

CM: It’s not what people want. Right? The business world in particular, even the academic world, is set up for easy, prepackaged answers. So, you know, the mobility industry is completely existentially in chaos right now. Will it be one technology or the other? Yet everybody has very quick answers and know everything about it.

Staying in the state of doubt and saying, “I don’t know. I don’t know what will happen, but I can try to think about it. I can try to understand the literature on it. I can try to understand what other people think about it,” and staying in that sort of doubtful, humble space longer, is not something people want to pay for. You can carve out a space for it—and I’ve tried—where you can carve out a space where you can get paid for it, but it’s not usually the norm.

The norm is you get paid for quick, easy answers that are not really accepting that you don’t know. You have no clue about what’s going on with how we cook, or how we eat, or how our love lives are changing—because they are, because of different kinds of technologies. If you don’t step back and [if you] stay in a state of doubt, you’ll not learn much. But that’s not how it’s set up right now. It’s set up for people already knowing.

AZ: When you stepped away from ReD [recently], which you had founded at 22, more than 20 years ago, what was that transition like? Did you experience this sense of doubt? What did that feel like, kind of day one? You were running a huge company.

CM: Of course, if you’ve done something for 20 years, there are lots of people you like. You have a lot of sort of muscle memory, in terms of clients, and client situations and problems, and how to deal with hiring the right talent, and so on. So, [there are] lots of muscles that you’ve created over 20 years that you no longer use, which is a weird kind of situation.

I still do commercial work, and I’m still involved in some of the ReD stuff, because they have some really juicy things going on. What I miss most is the talent development. What’s important is seeing people grow.

Madsbjerg with three colleagues at ReD Associates.

AZ: You just think about the people you worked alongside with.

CM: Yeah. Exactly. That’s what really matters.

AZ: Yeah.

CM: What I’m most proud of is seeing some of them just killing it, and just being amazing.

AZ: How you found candidates and what you looked for within candidates, I find really interesting. The hiring process in a company that’s rooted in observing the world and human behavior requires a really certain kind of person.

CM: Yeah.

AZ: What did you look for in the people that you hired? And who were the most successful of that group?

CM: If you think about the two things that I’m interested in, which is observation and listening, which really is the same thing. It’s a passive thing, right? It’s not acting. It’s not creating. It’s none of that. It’s just looking at the world. So, it’s a quite introverted and passive thing.

“If there’s anything that’s unfashionable today, it’s passive. But you can see that in people, when they have that doubt, and unease about what’s going on, and have used the tool of observation to try to figure it out. After a while, when you’ve met hundreds of people, then you know how to spot it.”

If there’s anything that’s unfashionable today, it’s passive. But you can see that in people, when they have that doubt, and unease about what’s going on, and have used the tool of observation to try to figure it out. After a while, when you’ve met hundreds of people, then you know how to spot it.

It’s often people [who] are drifters. They’ve tried one thing, then they did a Ph.D., then they tried something else that didn’t really work. They’ve been hovering over, sort of figuring out how to use that skill of observation to [do] something meaningful. They couldn’t find it in academia because academia’s hell. It’s specialization mania. The business world wants you to accept easy answers, and then they try to find a place where they can be observers, and they can stay in “not knowing” a little longer, and they can ask the right questions.

So, instead of asking the question, “How do we optimize our retail channel?” they can think about, “What is shopping? Really, what is it? What is it about it?” I mean, some of it is necessary. Some of it is delightful. Most of it is not. You know, is not as delightful. What is shopping? Or, instead of asking, “How do we get more customers to our retail bank?” they can ask, “What’s money?” Really, what … How is money experienced? That’s not so easy.

I mean, if you think about it, money is money. But there are different kinds of money. There’s money for groceries, and there’s money for your children’s education. Those are vastly different kinds of money. You can add it up in a spreadsheet, and it’s all dollars and cents. But they’re really, experientially, very different. So, people that ask questions like that, that are basically human phenomena rather than business jargon, are the ones I’m always been attracted to and looking for, and like to hang out with.

AZ: It must have been the people that felt most lucky to have found a place to work like that?

CM: Just relief.

AZ: Yeah.

CM: Yeah. Just, all the noise goes away. There was one person [who] said, “It’s as if the exhaust in the kitchen is turned off.” That noise of exhaust in the kitchen, when you suck out the air of the kitchen, when you turn that off, there’s sort of a relief of something quieting down. That’s the way, I think, they feel about it.

AZ: As in the leadership position in that kind of community, you had to protect them from the forces working against it, which I’m sure were constant.

CM: Yeah. Yeah. Because they’re fragile, and I am, too. But you can learn—I’m sure you’ve done that, too—you can learn how to deal with it and how to play the game, but in the first years you need to protect them against just the relentless—

AZ: You can learn to protect yourself against it, but, at least in my own experience, what you do learn in the end is that you’re not of it.

CM: Right.

AZ: If you’re not of it, you will never fully understand it, and you will always be an enemy of it.

CM: Right.

AZ: In a way. Even when you’re embraced by it.

CM: Yeah.

AZ: Which is why ReD, as a company, and the thing that you’ve built, and the sort of approach to business thinking that you’ve built, that you’re really go into in Sensemaking, is so innovative, in a way, and so needed by companies, but probably thought of, often, as a soft kind of cost.

“There’s not a natural demand for complicated and slow.”

CM: Right. Yeah. It’s slow and expensive, and complicated, and different, and so on. There’s not a natural demand for complicated and slow.

AZ: But it can shift a company profoundly.

CM: Absolutely.

AZ: You did that several times, which I’ll get into a little bit later, but I did want to talk about your latest book, Sensemaking, which has come up a couple times already in this conversation. It came out in the spring of 2017. It sort of describes the tyranny of the algorithm.

You lay out this argument for why our reliance on big data comes at a cost where human judgment is kind of devalued. I’m curious, since that book came out, so much has occurred in the world. What do you think has changed in these two years since the book came out? Do you think that it’s proven how right the thoughts were in the book? Have you changed your mind about certain things? What’s shifted in those two years?

CM: That’s a good question. I was uncomfortable with some of the statements made by the technology industry, and that was the beginning of the book. Media companies would say things like, “We know more about you than you know about yourself.” So, Amazon, because it has been tracking all your purchases and all your behaviors, and listening in on you in your home, Amazon knows more about what you will buy next than you do.

There was this story at the time where it was said that the algorithms the target sits on could predict if people were pregnant before they knew. That’s not only ridiculous but also just a vast overstatement of whether that’s the case or not. But I was scared of that thought. I was scared of the thought that they really think that the machines know more about us than we do. I was just basically looking at my Amazon page. I’ve been heavy user of Amazon since 1995 or something like that. So, they should know something about me.

So, why is it they’re still presenting books by the same author that I just bought some other book by? That doesn’t seem, like, completely brilliant. Why is it that most of it is nonsense? Then I looked into it, and it turns out that they’re not very effective, in terms of predicting anything. Of course, at the time, it was the aftermath of the crisis, and it was quite clear that, even in the middle of it, the biggest users of advanced algorithms and all the data in the world couldn’t predict what on earth was going on right in front of them.

And, if that’s the case—if they can’t—who can then? I’m not saying that data is not important. I’m not saying it’s [not] significant. I’m just saying the claims were so dramatic. They were saying, “You humans, really, I mean, what are you for? You’re all going to lose your job. We can teach your kids better. We can run your love life way better. You’re awful at choosing partners. So, we should really do it.” That made me highly uncomfortable.

AZ: Yeah. You kind of just want to go, “Who the fuck do you think you are?”

CM: Exactly. Exactly.

AZ: Which no one was doing.

CM: I wouldn’t have sworn, but yes. [Laughs] Pretty much the same sentiment. It was just so outside of anything I know, from what human beings are and what we’re good at. It just seemed ridiculous to me.

“Humans have a skill that robots don’t, and probably never will.”

There were statements that the robots would take over everything, and we would just be leisure creatures that could be served by these robot overlords. It just seemed unreasonable and stupid. So, that’s why I wrote the book. Humans have a skill that robots don’t, and probably never will. There are probably a lot of cognitive scientists and data scientists that would disagree with that right now, but I think so.

The main argument is that they don’t care. The core of human beings is that we care about something. We care about our families. We care about their future. The care is what robots can’t do. They don’t give a damn. If you don’t give a damn, you’re not human, and you don’t have human intelligence. You can’t make our priorities. You can’t predict us. It turns out, again, and again, and again that the machines can’t predict much.

“If you don’t give a damn, you’re not human, and you don’t have human intelligence.”

AZ: Yeah. Kai-Fu Lee [who Andrew interviewed on Ep. 6] talks about this a lot, in terms of job loss. There will be more human-based jobs, more empathic, emotional intelligence–based jobs, and artificial intelligence will sort of take care of the things we shouldn’t be doing. What do you think about that?

CM: Yeah. I think that’s right. I think the Excel software program has been better at math or, you know, numbers, my entire life. It’s always been better. That is a machine, doing something better than I do. Just like so many other machines are better than we do. That’s great. But it isn’t human.

AZ: Can’t take your kid to the park.

CM: No. If it did, would that be so great?

AZ: Yeah.

CM: I don’t think that would be such a great experience for anyone.

AZ: Well, in the last two years, the one thing that has occurred since your book is that there is this “techlash” happening. It’s bigger than Facebook and Cambridge [Analytica], and all that. We’re having this response to the force of Silicon Valley. How does time play into this? Do you think that it has something to do with speed, and the way they’ve sort of weaponized speed, and [that] we’re coming to understand that?

CM: I think there are two sides to Silicon Valley. It’s an impressive generator of new ideas. A.I. is a huge idea, if you think about it. It just happened to be fifty percent wrong in all kinds of cases, but it’s a big idea. But then they seemed to stop thinking, and they just replicate the idea over and over.

So, they would say, “If A.I. is possible—let’s say it is—it can predict anything. So, we should use it for predicting human behavior related to earthquakes. What will happen if we introduce a product? What would happen… If you buy this, would you also buy that?” They think that it’s sort of a tool that is omnipotent. There’s a really thoughtful part of Silicon Valley, but then there is this sort of bullshit amplifier mechanism to it, where it gets taken to any part of life. Nobody really thinks about, “Is that really true?”

Let’s take love and courtship. It is true that we’re crap at choosing partners. I’ve certainly made my mistakes in life. I’ve also been incredibly lucky. But is it true that an algorithm can pick, you know, who you should be with better than you can? That’s the first question.

The second question is, if it was the case, would we want that? Would you want sort of algorithmic precision, in terms of love and courtship? No, thank you. Their assumption is just wrong. They’ve taken a technology they’re excited about, and then they implement it in every single area they can. That’s really dangerous and stupid. It’s really an engineering excitement, entering the area of social behavior that they don’t understand, and they don’t really care much for.

AZ: We’ve moved past arranged marriage. Why are we back? [Laughs]

CM: Right. Right. Exactly.

AZ: Do you think, in certain ways, that Silicon Valley is kind of chipping away at our intellectual life? I mean, how has their massive, meteoric success in the last ten years affected culture? Humanity?

CM: So, first, I’m impressed by their generation of ideas. I’m scared of going to a conference about work life, and how we arrange our offices and our work environment, and all they talk about is A.I. You would imagine there are other aspects to work life, and how we arrange our offices and furniture, and so on, than A.I. Then you go to a conference, or you talk to people in the philanthropic industry, who are trying to solve hunger and, you know, big, heavy topics, and all they talk about is [how] A.I. is going to fix it all.

“There is this sort of acceptance of the ideas of Silicon Valley that’s really scary. It’s thoughtlessness.”

I’m really scared about how the ideas are taken over, and not scrutinized, and no time for doubt, and no time for really, is A.I. going to solve world hunger? Maybe there’s something to it, but there is this sort of acceptance of the ideas of Silicon Valley that’s really scary. It’s thoughtlessness. I really felt that when the book came out, that they think it’s ridiculous. Like, how could someone think that it isn’t about Agile and A.I., and big data, whatever they talk about at their time.

They really think that they can create a brain and predict everything we do. To me, you know, I studied philosophy, so I know that that’s not the case from whatever I’ve learned. I don’t know what’s real, but I know that’s not true.

AZ: Yeah. You’re studying philosophy … also described the context related to time. I mean, Heidegger is still considered a sort of modern philosopher, and it’s over a hundred years old. You know, so, this idea of, move fast, break things, this moment, this idea of speed, I don’t think is necessarily adopted by someone who studied long history of philosophy and human thought.

CM: Right.

AZ: Do you think that this lack of context that exists in the Valley—in which they feel they need to innovate, they feel they need to move forward—is actually a great detriment to moving forward responsibly?

CM: Yeah. I think context is important. I don’t know what the numbers are, but kids are not interested in history anymore. The history departments are emptying out. Where are the historians, telling us that that idea of machines that can take over our intelligence has been repeated over, and over, and over again? It was big in the fifties. It was big in the sixties. It was big again in the eighties. It’s the same discussion, but there are no historians saying, “Wait a minute. This is an old discussion.”

“The lack of context in Silicon Valley, and how much they despise people that studied history, or literature, or art history—they really don’t like it. That’s scary.”

It really is, in this case, a discussion between Descartes and Heidegger. That’s, what, a hundred years old, or something like that? So, the lack of context in Silicon Valley, and how much they despise people that studied history, or literature, or art history—they really don’t like it. That’s scary, I think.

AZ: There was this great talk I watched with you and your co-founder at Google years ago, where you talk about the kitchen and the future of the kitchen. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

CM: Right. I haven’t thought about that for a while. The idea is—and it’s been repeated over and over again since the fifties—is that cooking is tyranny. Cooking is something that we should automate. Here is a machine that can automate cooking for you. Wouldn’t it be great? You push a button and a cake comes out. That idea’s been repeated—it’s being repeated right now. You know, there are Korean companies building kitchens that can do this—or they say they can do this.

Nobody’s scrutinized. Like, is cooking really tyranny? Sometimes it is, but it’s also pretty delightful core of human existence. I enjoy it. It’s part of other things, which is feeding your family and nourishment. You know, not just the food itself but making something for someone else. That idea that cooking is tyranny has been repeated over and over—and failed—over and over and over again. If anybody had a historical view of that idea, they would say, “Don’t do that again. Maybe there are parts of it you can help, but don’t have that idea, [for the] eighteenth time, where it’s been…”

AZ: I think it’s really indicative of this hubris that happens in forward-thinking technology and innovation, that we know better, and we can throw out all of history, which seems to be kind of the underlying sort of approach to everything right now with technology, is: We know better.

CM: Yeah.

AZ: This is what you want before you know you want it.

CM: Until you don’t.

AZ: Until you don’t.

CM: Right? So, it looks like social media is a great connector of people and has a lot of great things to it, but it’s also making our teenage girls miserable, and making them compare each other in a way that they haven’t done before. They can rule each other’s relationship online, and it means that the rate of suicide ideation and self-harm has doubled since the iPhone came out, and since the social media companies started.

Then, maybe, the hubris isn’t so funny anymore. Maybe we should think about that. If you think about 5G, that’s being rolled out as we speak. It sounds great that you can download Netflix movies a hundred times faster, doesn’t it? But what does it mean that it extracts a hundred times more data than what they do right now? Are we sure we know what that would do to us, our health, our cities, our relationships? Let’s think about that for a second before we completely, arrogantly, go out and say, “This is a hundred percent good for humanity.”

You know, it’s good for some things, but it’s also a way to manage unintended consequences. That’s what I lack. I lack that sense of doubt in Silicon Valley once in a while.

AZ: You know, you mentioned Zuckerberg in the Congressional hearing. You watched that, and it felt like he was describing how to use a microwave to his grandparents. There’s also the responsibility of government to be educated, in terms of the moments of change.

Why isn’t there a division of the government, like there may have been in Rome, that [could be], you know, considering the moves we’re making and how they affect generations ahead? It seems like it’s also not just the Valley, but it’s the responsibility of the individual and, really, the responsibility of government, which is not happening.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the leadership teams in Silicon Valley. I met a lot of them. One of the things I’ve found being common is that they have an abstract and statistical view of humans.”

CM: I agree. They seem to be busy with other things. I’ve been thinking a lot about the leadership teams in Silicon Valley. I met a lot of them. One of the things I’ve found being common is that they have an abstract and statistical view of humans. So, they would say things like, “Overall, we think that our platform increases happiness and social connections.“ That might be correct, but it’s not a first-person experience, and there’s a whole lot of things that fall through the cracks, or get broken when you move fast.

Without the thought that the first-person experience is also important. It’s not just the aggregate abstract version of it, it’s also just relationships between people, and they are very bad at that. They’re not very good at understanding that. They would say things like… I’ve heard them say this. “Gen Z seems to be very worried about their future, yet the future’s never been better. We’ve never had, you know, more jobs. We’ve never had a better economy. So, they shouldn’t be so worried.”

Correct. The economy is pretty good. Lots of things are getting way better. But that doesn’t mean they’re not experiencing it, at a first-person level, as being full of doubt and full of sort of existential dread about the future. That’s important too, whether that statistically it shows itself in the statistics, or if it’s just a subset of the statistics. It’s this sort of abstract statistical view at humans that I feel really scared about. It’s common in Silicon Valley.

AZ: And it’s not just the leaders—that sort of engineering leadership—it’s also the design leadership. I mean, for a moment I’d like to talk about this “design thinking” that has come into play in the last ten years, and the issues that come with that, and the elevation of literally, the industrial designer, or the graphic designer, as a social scientist.

CM: Right.

AZ: Tell me a bit about that.

CM: I like design, and some of the best things that happen are done by designers. I’m involved in design in all kinds of ways.

AZ: Yeah. You stood on the board at Fritz Hansen, you’re on the board of BIG, you helped form that company.

“Designers have taken on a role as the aggregator of all information, and become pretty arrogant, and the process with which they do that is this strange concept of design thinking.”

CM: Exactly. But just like everybody else, I think, designers have taken on a role as the aggregator of all information, and become pretty arrogant, and the process with which they do that is this strange concept of design thinking. Nobody can really explain to me what it is, but it’s some idea that designers have a special access that other people might not have to what people want. Why do they know that? Well, they’ve met a couple of them, or they’ve iterated on something with a few people around them. You know, sometimes that’s great, but sometimes that is a little bit too light, if you want to understand people.

It’s arrogant to think that you can sit in Palo Alto and know everything about what’s going on in … I don’t know … Venezuela. Maybe you’re different than them. Maybe you don’t know. I think there’s a lot of young designers, in their late twenties or early thirties, that seem to know everything. I always get scared of people that seem to know everything, and design thinking is sort of the sticker for that. But it really is just basic arrogance, and I think designers have taken that chance. Not all of them.

“I always get scared of people that seem to know everything, and design thinking is sort of the sticker for that.”

AZ: No, of course not.

CM: But they seem to have left the idea of beauty and aesthetics as the core of design to something about knowing what the user needs, and I like aesthetics. I like people that strive for beauty. I don’t think it’s the answer to everything, but it’s certainly a meaningful component of life. So, the designers we’re talking about here are not the best designers. They’re not aesthetically, technically the best, but they’re the most arrogant, and it seems to be taking over everywhere. I don’t like it.

AZ: Yeah. Well, I think it stems from—you know—design became monetized.

CM: Right.

AZ: You know, and it entered the business world, maybe, ten years ago or so, when people started to go, “Wow, when companies design nice things, they seem to make a lot of money, so we should elevate the designers to be part of the table,” which, I think, is important. I think design is crucial, and design is certainly the organization of existing material, or extracting beauty out of material, but design thinking, I don’t really understand.

You talk so much, in your books, and in your lectures, about, how can one understand what’s really happening unless you actually go and look? Because you can’t ask people questions and get answers that matter.

CM: No.

AZ: Something that concerns me, and I know concerns you, is this idea of, “Why go get a degree in philosophy? Why get a liberal arts degree?” is being challenged, you know, “You should just be an engineer, then you’ll have a job, or you should be a designer, then you’ll have a job.” So, what worries you most about where our education system is now, and how that’s been affected by the previous ten years?

CM: Well, I worry about, if you’re 16 years old, and you’re really into—or 19 years old and you’re really into art history. Because you’re scared of not getting a job, you won’t study art history, and you will become an accountant, or computer scientist, even though you don’t like it, and you’re not excited about it, you do it because your parents tell you, and you do it because it’s, somehow, safe.

I studied philosophy because… I don’t know, I just ended up studying philosophy. It wasn’t to get a job. If you work, and you try to think about how you make yourself available, and sort of meaningfully employed, you can study philosophy, or art history, and be perfectly successful. In fact, the most successful people did that. If you look at the top earners in North America, they over-index on humanities and liberal arts, and not computer science.

So, it’s sort of this idea that education has to be functional. I think education also has to be educational, and general, and follow what you want to do. If you study art history, you can certainly become really successful in other kinds of life.

AZ: Well, you had the great benefit of growing up in Denmark.

CM: Right. Cheating.

AZ: Well, I mean, it’s kind of like, growing up in, like, a Bernie Sanders America or something, you know? So, for a moment, I want to get a little bit into your roots. Where were you born?

Madsbjerg as a child.

CM: I was born in Denmark. I grew up on this tiny island south of Sweden, which has forty thousand inhabitants. It was tanking, financially, because the cod fishing collapsed in the eighties. So, I grew up in this sort of depressive environment where, maybe, Dad didn’t have a job anymore, generally, but there’s a welfare state that makes it possible, even in that situation, to get a decent education, to have health care, and that means you don’t fall through the cracks.

So, people talk about Denmark as the happiest country in the world. I think it’s the least unhappy. You know? Because you don’t fall through the cracks. It’s not that they are so joyful. In fact, they’re not. The Danes are not. But it’s because there’s not the deep mystery of just not having a chance to get out of there. I was lucky that there was a public library that was incredibly well-stocked, and that sort of saved me, in the middle of all that.

AZ: You were a voracious reader as a child. Why was that? How did you find reading?

CM: I think there are two things. One is introversion. Sort of, being quiet, and just liking long stretches of quiet time. And two, I had asthma. So, if you have asthma, you can’t run around in the same way that other kids can. So, they play [soccer] and, you know, other things, which is, of course, what a child would do. But if you can’t do that, you do something else. In my case, it was reading.

It was not necessarily just a positive choice that I… It was wonderful. It was also just, you know, I couldn’t play soccer as the rest of the—

AZ: What did you think you were going to be?

CM: I thought I would be an academic. I thought I would be a professor. I ended up being one, which is kind of strange, but when I went to university I hated it because everybody seemed so miserable and unhappy. If you think about it, if you’re a professor, you get paid for life for doing what you want to do. That sounds pretty good. So, I was just like, “Why are they so miserable?” That’s why I ended up founding a company and doing other things.

AZ: And you founded a company at 22.

CM: Yeah.

AZ: Which is rare.

CM: Is it? Yeah. Maybe.

AZ: Maybe not in Denmark. Here it is.

CM: Yeah.

AZ: Maybe in the Valley it’s not.

CM: Yeah.

A park in Copenhagen near the ReD Associates offices there.

AZ: But it wasn’t just a company. It was kind of a new way of thinking. What was your first project? How did you form the company?

CM: Right. Well, it wasn’t really thought of as a company. I didn’t know what a company was. I didn’t know what the business world was like. I fell into it because I had to make a living. The first project was for the Danish, for the Copenhagen health care authorities [Danish Health Authority]. All the health care that was going on. So, that’s elder homes, it’s hospitals, it’s all of it.

They asked me, “Why is it that one in five people working in the system call in sick every day?” It’s a lot. Twenty percent sick leave are problems. It’s more than you would hope because it means that, you know, as a normal worker, every Friday you are out with some illness. They didn’t really know why. So, they said, “What about this kid? Couldn’t he take a look at it?”

So, we observed it, and spent time in wards, and people getting hooked up to dialysis machines, and just sitting, looking, following patients, and following nurses and doctors. We found that they spent most of their time on managerial things, on filling out forms, doing all kinds of things that had nothing to do with the reason why they came there. I said, “How about you make an experiment? You roll back some of the administrative tasks that people have to do, and see what happens?” It immediately fell to seven percent, instead of twenty.

Why? Because the people that were there got to do what they wanted to do. So, that made me think, “Well, maybe there is something to this observation thing. Maybe there is something to carefully looking. Maybe others didn’t think about it.” Of course everything is obvious once you know the answer. But it turned out it wasn’t obvious, and then Lego, the Danish company—

Legos.

AZ: I was about to ask that. What happened when you went to Lego?

CM: Right. There was a new CEO that arrived in the middle of the darkest time of this company that’s lost so much money…

AZ: $300,000 a day.

CM: Right. Systematically, for ten years.

AZ: Unbelievable.

CM: Yeah. They had owners with deep pockets but, you know, ten years of losing money like that was a problem. They were finally in the hands of the banks. The new CEO was humble enough to ask the question, “Why do kids play?” You would think that a toy company should know why kids play. They then asked us, “Could you take a look at that?”

We started by looking at them and saying, “What do you think?” They said, “Well, all we know about kid’s play is that the brick isn’t relevant anymore. It’s computer gaming now. Two, kids have ADHD, rising levels of ADHD.” So, again, an abstracted version of reality. And that’s why. Because computer games is more engaging, and kids have a lower attention span, so that’s why we need to design our toys for lower attention span.

We said, “Well, okay. Let’s go have a look.” We went out, and we looked at kids, in this case mostly boys, in Germany, and U.K., and China, and U.S., and we just sat on our knees, just playing with them, and looking at it. It turned out that they might have clinical diagnosis of ADHD, but they certainly like complexity. They like building things. They enjoyed learning hard things.

So, this whole story about [how] things need to be easy and quick, and fast traction, just wasn’t the case at all. For any educational historian, they would say, “Of course!” But for Lego, it was new. That meant that they could vastly reduce the portfolio of product, and they could change their product pipeline to be focused on more complexity in learning. Suddenly, Walmart came back, Target came back as retail partners. Now, they’re the most valuable company in the world.

AZ: Yeah.

CM: The CEO that’s still there would say, “That was an important, iconic moment, where we understood our assumptions were wrong about children’s play.” That story sort of took off. Suddenly, Adidas wanted to work with us, and Samsung, and Intel, and [Coca-Cola]Coke, and so on.

AZ: You continue to study and observe the underlying notions [that] what they were thinking was real, which may not have been in line with reality.

CM: That’s my interest.

AZ: Yeah.

CM: It is on the basis of what are you doing what you’re doing? On the basis of what kind of assumption are you thinking that this is a reasonable thing? Right? We do a lot of unreasonable things. So, right now, let’s give an example.

Right now, sales representatives of pharmaceutical companies are going out every day in their little car and getting kicked out of doctors’ offices, systematically, yet we’re doing it over and over again. So, I’m interested in what’s the assumption, underneath, that that’s a reasonable thing to spend your money and time on. Or in the kids’ play case, is it really true that what’s happening is that the attention span is getting shorter and shorter?

AZ: Or in the case of Samsung, something as simple as a television, what did you learn?

CM: Yeah. So, the assumption of Samsung, when I started working with them, was that TV, a TV, is a piece of electronics. It’s sold on pixels. It’s sold on little stickers on the bottom of the screen, and it should be positioned as, designed as, talked about as, a piece of electronics. Then we went out and looked at families, to see, is that true? Is it true that it really is electronics? And it turned out no. It’s furniture. It works as furniture. It fits into a room.

Of course, that’s obvious, but that’s not what they thought about. So, again, we switched the assumption from it’s a piece of electronics to it’s a piece of furniture. That’s when the TV business of Samsung really took off. They would also say that it’s that insight that, we have to design it as—talk about it as—furniture, and really, it should disappear.

AZ: Why is it that large companies fall so out of touch with changes in the real world? I mean, over and over and over again. What is that? Why?

“it seems like the [big tech] companies that we have now are going to be there forever, but there’s no historical evidence that that’s the case.”

CM: Yeah. If you look at the list of the biggest one hundred companies in the 1950s, or the 1980s, not many are left. Right? They die. You know, it seems like the companies that we have now are going to be there forever, but there’s no historical evidence that that’s the case. So, why do they not connect to reality?

It really is [that] there’s no program inside of most companies to say, “Let’s understand why we think the way we think, and whether our assumptions are still healthy, or whether they’re toxic. If they’re toxic, what do we do about it?” Why do they not do that? I don’t understand. It’s too “agile.” It’s too fast. It’s too… We need to meet the next, you know, third-quarter call with investors. They don’t have the time to think like, “Wow, what’s really going on here?”

AZ: Then they get into a lot of trouble, enough trouble, that they call you.

CM: Yes.

AZ: Then they call you, and you’re stepping into what you described earlier in the conversation, this sort of directionless panic. What’s that like to step into over and over and over?

CM: Yeah.

AZ: You know, you’re like Mister… Like “The Wolf” in Pulp Fiction. You sort of show up in the most panicked moment.

CM: Right. I quite enjoy it. There’s nothing more healthy for change and understanding than a good crisis. It’s just the time where you can change things. If people are just, you know, doing really well, you can’t convince them of anything. Even the most obvious things, you can’t convince them of.

So, I like these kind of moments of unease, and that’s mostly when they are interested. Then the move is very simple. It is, they would say, “What’s our portfolio?” They have jargon. So, they would say, “What’s our portfolio, our price points, and our product, and our…” They have all this, sort of, business language. Then the move is always to say, “Well, what’s the human experience underneath that?”

So, if it’s a bank, what is money? How is money changing? Or if it’s a dating app, it’s not about competing against other dating apps. It’s, what’s happening to courtship? That’s the human experience underneath. Then that’s what we go study, or I have been studying for my whole life.

AZ: You talk about these four rules you would use at ReD. Can you take me through those?

CM: I can’t remember.

AZ: Your first rule— I’ll line you up, alright? The first rule is about the underlying assumptions, and the second rule—my favorite—is the slowdown. This is when your idea about scrutinizing the underlying assumptions. The third rule was counterexamples, which was the one that I found the most interesting. Tell me about the process of that rule, and how you came to that.

CM: The counterexamples?

AZ: Yeah.

“It’s so easy to trick yourself into thinking you know the answer, and it’s so easy for a whole organization to think that they know everything, but if you explore what the opposite would be like, or what the opposite argument would be like, suddenly it isn’t so easy anymore.”

CM: It’s so easy to trick yourself into thinking you know the answer, and it’s so easy for a whole organization to think that they know everything, but if you explore what the opposite would be like, or what the opposite argument would be like, suddenly it isn’t so easy anymore. It really is a trick from John Stuart Mill.

John Stuart Mill wrote a book, called On Liberty, that every single listener to this program should pick up as fast as they can, especially chapter two. It is about when do you have an opinion? When does anyone have an opinion about anything? He says the bar is, you have explored the opposite. If you haven’t meaningfully and honestly explored the opposite, you’re not allowed to have any opinion.

So, if you hate a wall to Mexico, you have to explore what it must feel like to want a wall to Mexico. Otherwise, you’re not allowed with easy opinions and quick statements. That is so healthy in an organization, or in a situation, where everybody seems to know the answer, just passing along easy answers about something. So, counterexamples is a way to trick people into thinking, “Hmm, there might be other ways of thinking about this.”

AZ: Your fourth rule, which I also love, was about protecting the time to not ground ideas. What happens when you actually spend the time to travel through ideas, to not be as linear, to be more thoughtful?

“Some clients have told me over the years, ‘What we really buy from you is slow time, and forcing us to think about what we’re doing, because we don’t have time for that.’”

CM: It’s very strange for people. Some clients have told me over the years, “What we really buy from you is slow time, and forcing us to think about what we’re doing, because we don’t have time for that.”

I had a client at Coke that I really enjoyed working with, and she had her days organized in fifteen-minute slots. So, think about that. Sometimes you could get two with her. So, you get two fifteen-minute slots. How do you think straight if you have that kind of life? It turns out that all the executives in most of the companies I work with have that kind of crazy life. So, unless you have a way of protecting, really scrutinizing whether what you’re doing is right or wrong, whether you could think about things in a different way, you’re just lost in this sort of endless, you know, quarterly-earnings reports and fifteen-minute slots. If you think about that, how stupid is that?

AZ: Well, we talk a lot on this program about time, and the difference between kind of “natural time” and our perception of it. What are your thoughts on those differences? That idea of like, “I can’t believe it’s already 3 [o’clock].”

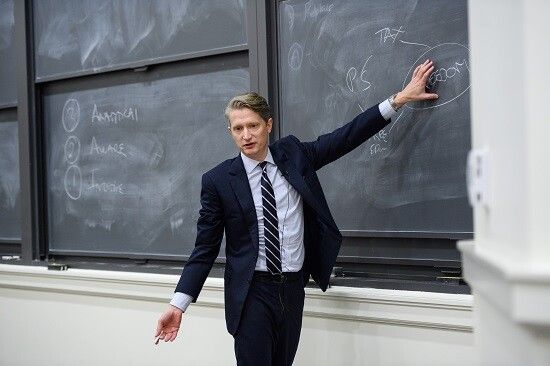

Madsbjerg presenting on Heidegger.

CM: Right, right. Yeah. So, that’s a core Heidegger topic.

AZ: Well, maybe we should take a moment right now, because you’re probably the best person to talk to about this, who is Martin Heidegger? When did he live? What did he contribute—

CM: Right.

AZ: —and why is he so relevant today?

CM: Right. I think he’s the biggest philosopher of the 20th century. He’s incredibly, almost tortured—complicated—to read, which is why, maybe, most people have a hard time dealing with him. But he was a German philosopher from Schwarzwald. So, the Black Forest, in the southern part of Germany.

He wrote many books, and they are all very important, but the main one is called Being and Time. It was out in 1927, ’28, that period. It was just a bestseller at the time. It was just crazy that a book like that can be a bestseller, because anybody that deals with it feels, you know, that’s a heavy book. I mean, that’s maybe the most complicated book in the world.

That book, basically, defines, in my opinion, everything that came out of—anything important in philosophy after that has either been challenging it, adding to it, or somehow dealing with his insight. It’s my thing. That book is my thing. I’ve been reading it over and over and over again. I teach it. When it comes to time, the insight is kind of simple. Maybe I should backtrack.

The main innovation, and the main thing he finds in that book, is that we have a set of background practices, things that are so much a part of ourselves that we never see. So, I do things every day that are based on the kind of life I lead, and it feels completely natural to me, but if somebody else looked at it, they would say, “Why are you doing this?”

“The way we look at time is what defines us as human beings.”

We have a set of practices that come from the culture we are part of. Language is like that. How we drive in the streets is like that. What we eat at night, how we treat our children, is all based on what he calls “being.” The way we are right now, in this world. That’s a very complicated thing. But he then treats us as time is what defines… The way we look at time is what defines us as human beings. And time is not so simple. You could think about time as very simple. A second is a second, and an hour is an hour, and every day it’s 3 [o’clock], pretty much at the same time, adjusted for a little bit.

Scientific time is that every second is the same amount, and every hour is the same amount. That’s the way you can look at it, and that’s sort of the abstract view of time. That’s the way physics works. That’s the way the natural sciences work. But he says there’s something else, which is human time, or experiential time, which is that even though a second is a second and an hour is an hour, it can be experienced vastly different.

So, a second can be more than an hour. Right? And an hour in your past can change based on where you are now. So, your twenties can be completely rethought and feel every differently if something happens in your thirties. Right? So, time is experiential, as well as scientific. Both are the case. That’s why we need natural science to deal with natural things like quarks and atoms, and planets, and human sciences to deal with the human experience of something.

So, a river or a mountain is not a river or a mountain unless there are humans experiencing them. That’s why he says the humanities is a different thing altogether than the natural sciences, and trying to use natural science tools to understand the experiential thing is a misunderstanding. There’s scientific time and experiential time, but if you take that to money, what does that mean for other things than time? That’s where I learned from it.

You could think about money as money, as money, and you can add it up in a spreadsheet, and every dollar is the same as every other dollar. It’s not true, though, right? Some money is worth more than others. The first money you made in your first paycheck is very different from the second one, experienced. The money you save up for your children’s education is very different from what you spend on groceries. So, even these things that are sort of quantitatively and abstractly completely banal, in a way, are not so banal when it comes to human beings.

Who can understand that? Well, humans can understand that. We can see this in each other. I think you have the experience, if you come from a particular background and you go to a different place, it feels very strange, what people are doing. You can also see that you are doing things that are, maybe, very American in a place where those things are, maybe not, as natural.

So, one thing could be distance standing. How far away we are from each other. Just banal. Just in a room, how far are we from each other? I find myself, with Americans, I always end with my back against the wall, because I need more distance than Americans. They need to get closer, and I need to get further away. That sort of dance is not something we think about much, but that’s the background practices. The things that we feel as most natural and most everyday, and most average, really, are the things that define everything about us.

The Moment of Clarity: Using the Human Sciences to Solve Your Toughest Business Problems (2014). (Courtesy Harvard Business Review Press)

He found that, pointed it out, and it seems, to me, that sociology, anthropology, literature, all these other sciences, other parts of the humanities, are completely defined by that idea. Sensemaking, and the book before, that’s called The Moment of Clarity, is trying to hide, as well as it can, that it’s a book about Heidegger. [Laughs] I’m writing a new one that’s really about the next iteration, which is called Merleau-Ponty. [Maurice Merleau-Ponty was] a French philosopher that talks about the human body and perception. I’m trying to hide that, really, that’s what it’s about.

AZ: Well, that’s why it’s so necessary. I mean, I got interested in Heidegger. I read it. But it’s tough to decode Heidegger in the modern world. Something like “standing reserve.”

CM: Right.

AZ: You know, can you describe what he means by that, and how it relates to now?

CM: Right. He wrote a lot, enormous amounts, and he wrote an essay much later in life, I think in the late fifties—no, even earlier—that people [call], the technology essay. It’s called “The Question Concerning Technology.” He’s trying to understand what is it that’s natural to us now? What is the background practices that we never question, that’s just going on around us, and the way we think about ourselves.

He calls the state of being right now “standing reserve.” The idea is that we are resources—we call it human resources—but we see the world as resources that we can optimize. So, a piece of land is something you can make condos on and sell. A forest is not mysterious anymore, it’s not holy anymore. It’s something you can optimize as a timber business, or something like that. Food is no longer food. It’s carbohydrates and, you know, molecules, really.

Looking at the world as just resources available to be optimized is the way we look at the world right now, but we rarely think about it. His problem is if we start thinking about each other that way, as resources available to be optimized, we have a problem, because there’s not much soul left in thinking about others as human beings—as available to optimization of resources. Yet, that’s how we talk about it, right?

“We have started to look at each other as optimizable resources, which, if you think about it, is very different from before, when we thought about each other as God’s creation.”

We talk about human resources in businesses. We talk about FTEs, full-time employees. We talk about head count. You know? That’s the language of standing reserve. That’s the language of technology, and looking at each other as resources. It’s kind of a profound essay, that people can try to read. It’s a simple idea. It’s written in the most horrible way, but it’s a very simple idea, really, that we have started to look at each other as optimizable resources, which, if you think about it, is very different from before, when we thought about each other as God’s creation. It’s a different thing to look at each other as God’s creation than it is to look at each other as resources available to be optimized.

AZ: Well, that’s why we need modern thinking, like yours, to make sure we don’t forget these things, and to make sure that we’re looking at these things from the lens of the past into the future.

CM: And yours, if I may add.

AZ: Thank you for joining us today. This was fantastic.

CM: Thank you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on Aug. 12, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by our director of strategy and operations, Emily Queen, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.