Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Céline Semaan. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

SPENCER BAILEY: Welcome, Céline.

CÉLINE SEMAAN: Thank you so much for having me.

SB: I wanted to begin with this current moment in time, and the past two-plus pandemic years in particular. We’ve witnessed a slow-down perspective begin to emerge, sort of by reason of lockdown and, in part, necessity. There’s been a greater awareness around slow culture, I think—or at least that’s my hope. [Laughs] How are you thinking about this period in this context? What’s your take on it?

CS: We just wrote a piece that’s going to be published soon in the Slow Factory journal that’s called “Slow Is Beautiful.” It’s basically a wink to the book Small Is Beautiful. It’s essentially the idea that slowing down has always been looked at in a very stigmatized way in our society. The idea of being a sloth, or lazy, comes to mind when someone says, “I’m just going to slow down. I’m going to take it easy. I’m going to take a break.” All of these sentences make us feel like, “Oh, you’re going to miss out. You’re going to miss out on your life. You’re going to miss out on your career.”

“The Earth doesn’t spin faster if you’re going any faster. If it did, I think we would all be dead.”

We’re living in such urgency and such a need to go as fast as possible, like a Fast and Furious kind of vibe. Those are the positive things. “Slowing down” and “slow” are seen as negative. It’s actually the opposite in a lot of ways. Eating fast, for example, you’re not even tasting your own food. Eating slowly is when you’re being present with your body and just enjoying the ingredients.

The whole idea of slowing down has always been looked down upon and seen as stigmatized. We were forced to do it for two years, and now we’re back to “normal.” I hate that expression, but it’s the idea that now we need to catch up. We need to catch up on all the things that we’ve missed out on, which again, is so sad, because the whole point of the idea of slowing down is to be present. The earth doesn’t spin faster if you’re going any faster, and if it did, I think we would all be dead.

[Laughter]

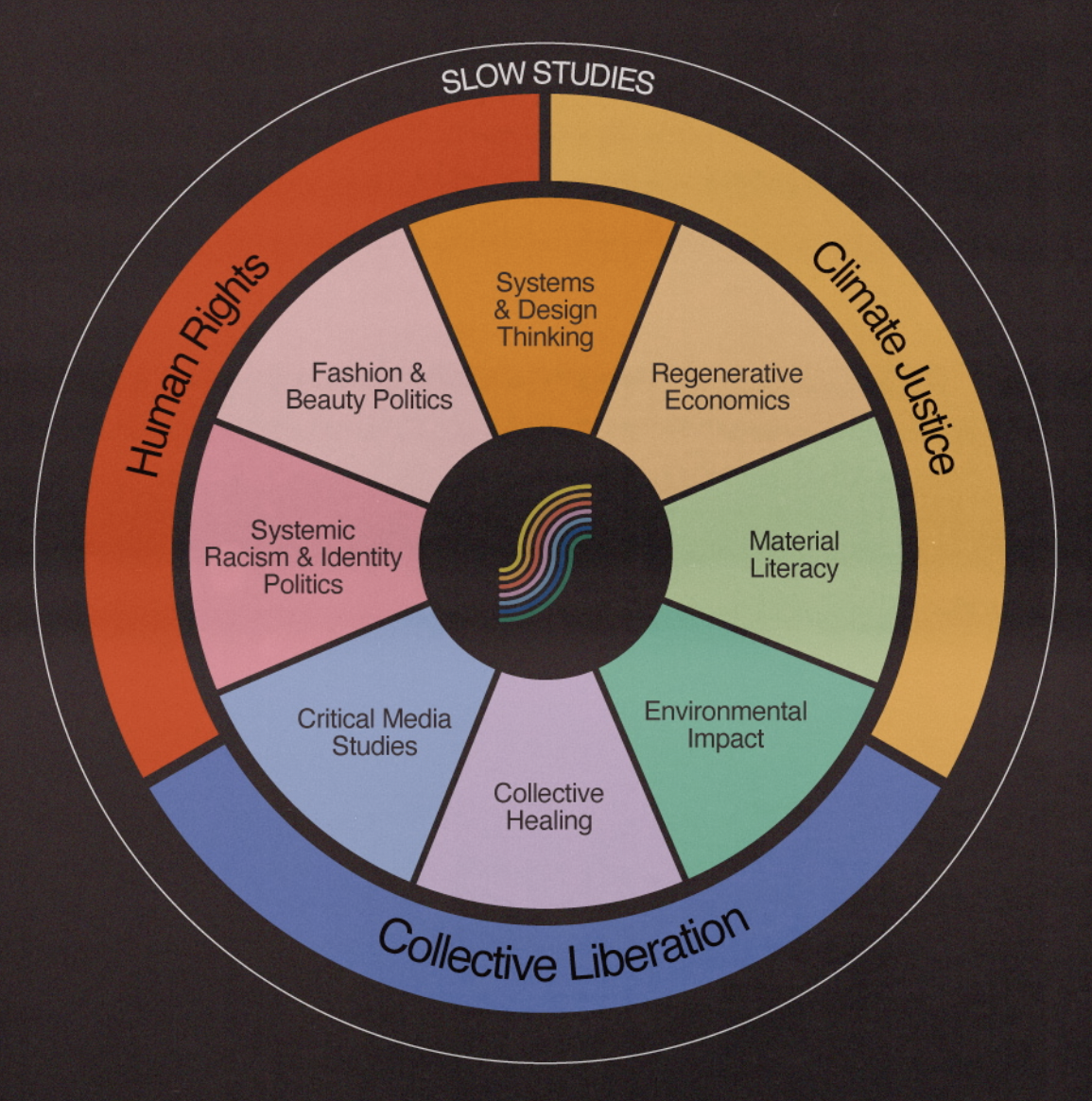

The Open Education mission spectrum. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

SB: It’s interesting you mentioned food, because I think Slow Food, of course, is so connected to this culture. In many ways, I think of what we might call “Slow Media,” or very much in the context of what you do, “Slow Fashion,” as these things that emerged out of the Slow Food culture, out of something that we were paying attention to, and really stemming out of and resulting from McDonald’s, the fast-food industrial complex of the fifties, sixties, seventies, TV dinners, that whole thing. How do you think about this evolution or transition from food to fashion, let’s say?

CS: That’s such a great question. There is a class on the Open Edu platform. Open Education, for those of you who don’t know, is a free online educational platform that we put together at the Slow Factory. There was a class, or a series of classes, called “From Food to Fashion.” I think the food industry has been the first industry to embrace slowness, or slowing down, or the word “slow” tied to sustainability, tied to this idea of farm-to-table concepts and organic food, eating organic. A lot of people embraced it because they understood that what I’m putting in my body is health. It’s my health. It’s my own health. But the concept of what I put on my body took a lot of time to be adopted. So Slow Food and the Slow Food movement was ahead of the Slow Fashion movement.

Of course, we built upon that movement to not only raise awareness, but build strategies for organizations and companies to embrace this idea of “farm-to-closet,” essentially. Is that even a concept? Could that be a concept? Sustainability in fashion has a lot it owes to the Slow Food movement.

“[People] cared a lot about what they ate, what they put in their body. But I was wondering, why don’t you care about what you put on your body?”

In 2012, when I started and would talk about Slow Fashion, people would laugh at me. They would say, “What are you talking about?” Fast fashion or fashion is something that’s frivolous. It’s to express myself. It’s not serious. It wasn’t looked at as serious, but they cared a lot about what they ate, what they put in their body. But I was wondering, why don’t you care about what you put on your body? You’re literally wrapping your body with plastic. Because polyester—which consists of 80 percent of what people own in their closets—if you look at it, polyester, acrylic, nylon, all of these things contain plastic. You’re putting that on your body. You’re putting that on your intimate parts because most of the underwear contains plastic. If not, they’re completely in polyester.

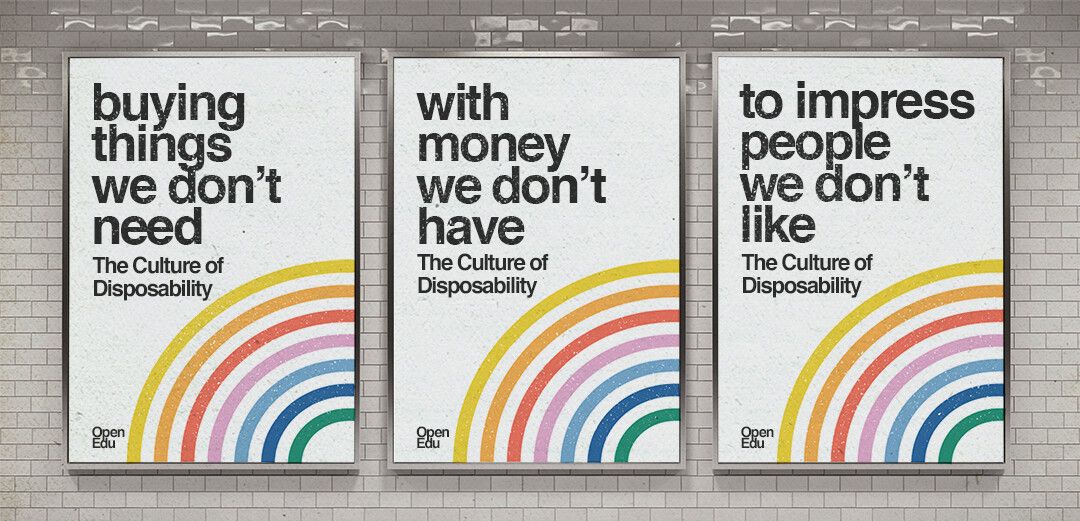

An Open Education subway billboard on the culture of disposability. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

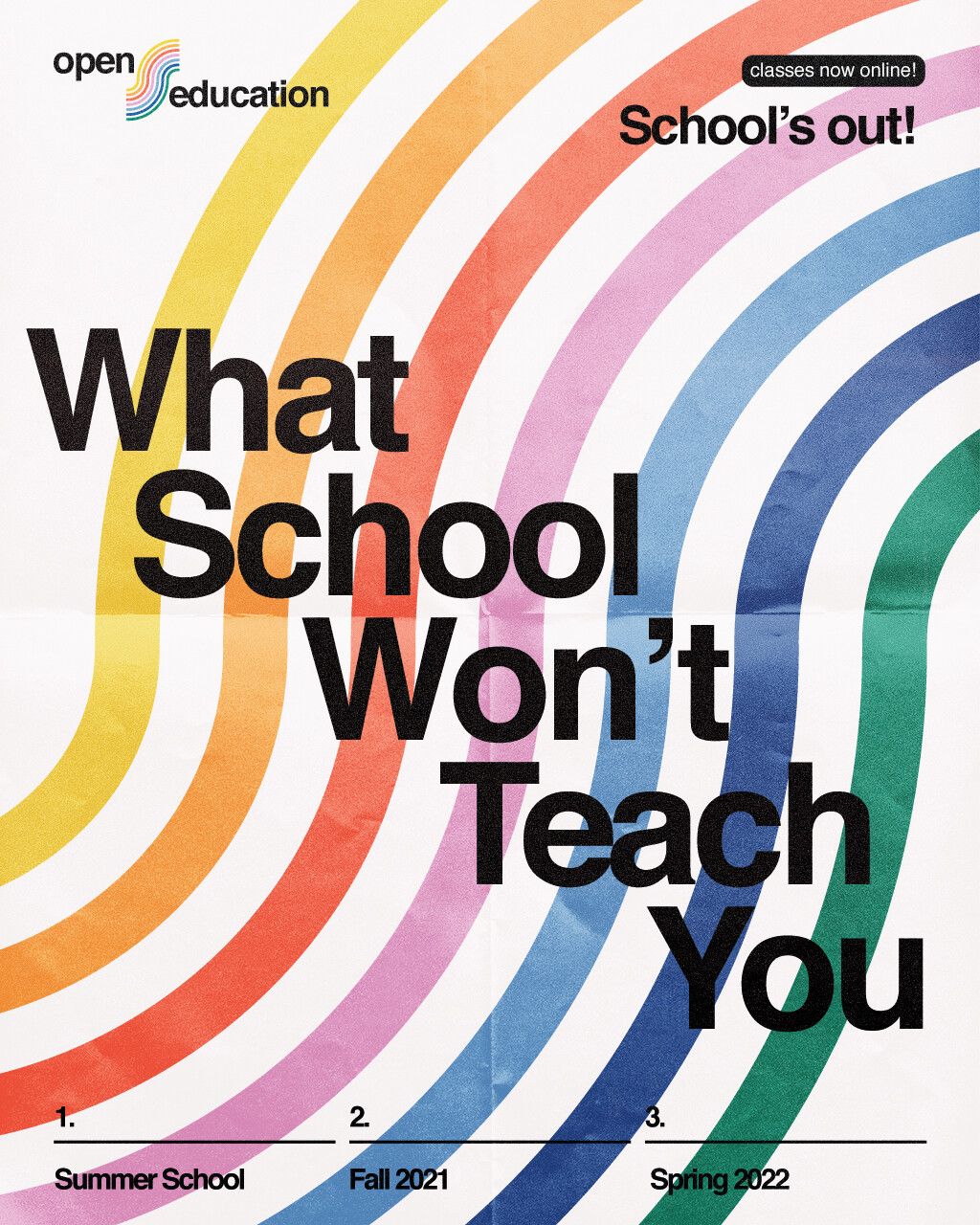

An Open Education advertisement poster. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Now there’s a whole movement of recycled plastic as polyester, and people feel good about that? But it’s still plastic! You’re still putting plastic on your body. Plastic shouldn’t be covering your body or be inside of your body. Plus, there’s this whole awareness that we had to work on, which is: When you’re washing these garments, they emit and they release particles into the atmosphere, into the water streams that are called microplastics. I know that now it has become a little bit more common or mainstream, this understanding that we’ve ingested at least a credit card worth of plastic into our systems because of these microplastics. They come from the fashion industry, sadly.

SB: I think we’ve been forced to think about these systems in a way that’s different. I definitely want to get to that in this interview because so much of what you do is about systems thinking.

While we’re on the topic of slow, I did want to bring up a conversation that Andrew [Zuckerman] and I had with the Ashtanga yoga teacher Eddie Stern in April 2020. This was for our At a Distance podcast. He said, “Maybe we need some regular ‘slow down’ days built back into our yearly calendar where everyone around the world agrees: Okay, for the sake of our planet, we’re going to close down for a couple of days each month and ease back on the pace that we’re consuming and polluting.” As someone who has been at this for a while, I was wondering what you think about that. How realistic do you think something like that could become with an organization like the Slow Factory, maybe partnering with The Slowdown, to realize something like that?

CS: Oh my gosh, what a dream that would be. Earth Day was not too long ago, April 22nd, and a lot of initiatives around Earth Day are about greenwashing: “Buy this because you’re going to save the earth. We’ll plant ten trees for you.” What we proposed was: What about closing down for Earth Day? What about not opening your stores for Earth Day? What about purchasing nothing for Earth Day? What about doing that gesture towards the planet?

There are lots of environmental movements, especially around light pollution, that are asking people to turn off the lights. Just turn off the lights. Imagine if Times Square would turn off the lights just for an hour. It would allow the whole grid to take a break, to take a breather because all of these lights are consumed by fossil fuel energy at the end of the day.

SB: Not to mention it would connect us to the cosmos. I mean, Andrew spoke with Andri Snær Magnason, the Icelandic poet, who did this in Reykjavik [Iceland]. Got the city to shut the lights off so they could see the stars.

CS: Wow. Yeah, we had a project like that in 2013, I believe. It was called “Cities at Night.” It was the cities that are the most polluting in terms of light pollution which are the cities that you see from space. They’re bright. They’re beautiful. New York! London! Paris! San Francisco! But those cities, when you’re in them, you can’t see the stars at night. It’s too bright. We raised awareness around that and we asked just globally, “Could we turn the lights off, please?” And to the question you asked, “How realistic is this?” Again, during the past two years, a lot of the things that were unrealistic became very possible. In fact, they were essential to our survival. Slowing down became the one and only thing that was essential to our collective survival.

“Slowing down became the one and only thing that was essential to our collective survival.”

So when we’re talking about “realistic,” what are we imagining? It comes to radical imagination again, here, about what it is that we’re allowing ourselves to imagine that is possible, that is realistic. It comes to the other question that I always get: Do you think sustainability is possible? I answer with another question, What are we trying to sustain? Is it that we’re trying to sustain our economic systems that are based on exploitation and on legalized pollution? Or are we trying to sustain a new form of living that is in tandem with the earth’s system? Because the way that we’re living is completely disconnected from how nature functions. It’s an artificial system that exists above the natural system, the ecological boundaries that we live in. We’re like, “F the boundaries. We’re going to live as fast as possible.”

SB: What struck me on a deeply personal level during the pandemic was being stuck at home or “on lockdown” and being in the same place or space for a period of several months—and actually understanding my relationship with the sun during that time, because of the way the sun would hit the apartment. As the weeks went by, not just the days, but the weeks, I had a very distinct understanding of the season, the time of day it was—I didn’t even have to look at the clock. There was an attunement to the earth that was very different than anything in our “normal,” hectic, day-to-day lives that we would get to experience. So in many ways, the pandemic, for those of us who were fortunate to be at home, I’m sure many people experienced something like that.

CS: Oh, absolutely. There are so many studies that are around that show that just putting our bare feet on the ground enhances our internal chemicals. Putting our fingers into the soil—there are so many studies. There are a few of them, if you’re curious, on the Slow Factory channels, on social media, on our website that talk about these things. When you put your feet or toes on the earth or in the soil, there are some pheromones and chemicals that are being activated and it increases the dopamine within your brain. It’s actually an antidepressant, a natural antidepressant that is to connect with the earth.

“The way that our systems are built are damaging not only to our ecosystem, but to ourselves, because we’re completely disconnected, in a concrete jungle, from the earth.”

For us, the work that we do, we really talk a lot about ourselves as “climate doulas.” It’s really allowing people to go through the pain of this whole collective understanding that we messed up. The way that our systems are built are damaging not only to our ecosystem, but to ourselves, because we’re completely disconnected, in a concrete jungle, from the earth, from our natural rhythms.

So when you’re talking about the sun, just how it hits on your apartment and you being attuned to these systems, that’s exactly… It’s at our fingertips. It’s literally at our fingertips, the ability for us to connect back with our environment. There’s this disconnect between us and nature. We think, Oh, we need nature. We need to save nature. We need nature to survive. But there is a misunderstanding where we are nature.

SB: We are “of.”

CS: Yes, we are nature. We cannot exist without nature. We are nature. It’s not that we need to save it. We need to save ourselves.

Semaan while developing biofabrics in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

SB: This year marks a decade since you launched Slow Factory. I was wondering how you view this decade, the evolution of this project which has morphed in these really fascinating ways.

CS: Well, when you say that it’s been a decade, yes, I think it hasn’t sunk in properly for us that we’ve been here for ten years. So we are preteen in our existence [laughter], which means we have a lot of questions, a lot of rebellion. We’re very much the same as when we started in terms of feeling this deep feeling of rebellion—of working with and for the revolution that we are collectively experiencing.

We’re just a little bit more mature in articulating it. We’ve matured the language. We’ve matured our critical thinking, our way of reacting to the news. At first, we would just be in complete reactionary mode, and it burned us out. Basically, internally, at Slow Factory, the team was burnt out. We were tired, exhausted. So we started incorporating within our own culture and our own systems internally, a lot of community care, mental care, mental health, and movement—body movement. We were not moving. We were on the computer all crisped up like anyone who works behind the computer.

So we started to change. We started to look critically at ourselves. We are running so fast. We’re called Slow Factory and we’re burning out, essentially. So what are we doing? Can we slow down? Can we afford to slow down? We started incorporating a lot more pace into what we do. I think that’s the maturity that I’m slowly but surely absorbing in these ten years, and feeling like now we’re going to pace ourselves.

SB: There is an irony about having the name “slow” or “slowdown” and not actually being able to slow down.

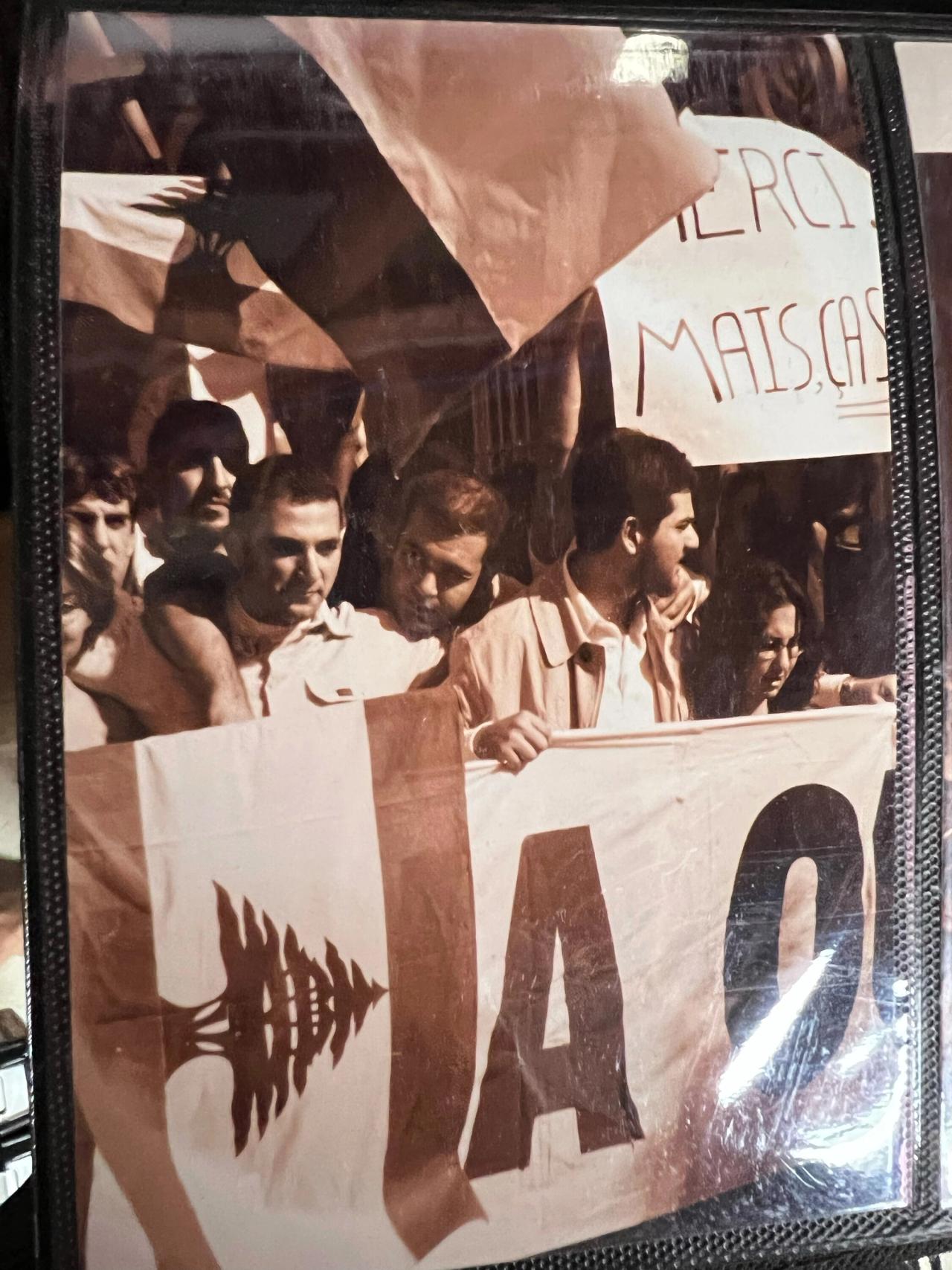

A photograph Semaan took, circa 1998, at a protest against the Syrian occupation of Lebanon. (Courtey Céline Semaan)

CS: Not actually being able to slow down. Actually, we’re trying to slow down capitalism. We’re trying to slow down this exploitation of the planet. On the front lines, we are working with urgency. We’re basically working with urgent action all the time—whether it’s support to a natural disaster, whether it’s support to even a school shooting, as we’ve seen this week, whether it’s support to an immigrant law that’s passing that is going to be detrimental to human rights, and therefore also connected to climate justice.

We’re constantly in this urgent mode because what we’re trying to slow down is this exploitative system. So it’s difficult. It was a difficult realization. Especially for me. I mean, personally, I’m a first-generation war survivor. I live with extreme PTSD and extreme anxiety. So I am all the time on the go. Being in survival mode is my natural state.

Even slowing down on a personal level was revolutionary for me. I felt like I wasn’t allowed because I can’t afford it. But I think that being here for ten years and looking ahead and seeing that we’re just getting started, I can’t go on if I go on just running. I have to pace myself. The team has to pace itself.

We have a lot of days off for collective health. For instance, after every tragedy we respond right away, and then we give ourselves 24 hours off afterwards where we are just on the phone calling each other or not, where we are engaging with healing. We had to redesign the way we function.

SB: You’ve been credited with coining the term “fashion activism.” I was wondering how the term, in the first place, came to you. And when did you realize fashion could be a tool, or a mechanism, or a medium for social and environmental change?

“Fashion carries meaning, and meaning carries action.”

CS: When I first started, people of course looked at me weird and said, “What are you talking about?” As I said earlier, “Fashion is frivolous. It’s fun. It’s glamour. It’s supposed to be light.” I said, “Yes. However, fashion is a sort of proletarian form of art. It’s actually illegal in most countries, including in the United States, to walk around naked. You are by default engaging in fashion, whether you like it or not. So whatever you put on your body has a meaning for you. If it has a meaning for you, just like everything is political, it has a meaning on a political level.”

That was way before 2016, when the government switched from the Obama era to 45. Isn’t that how it’s called? The era of 45. So it was before the pussyhats, before the T-shirts saying, “We should all be feminists.” It was way before that time. People thought I was looking at—it too farfetched, this idea that fashion carries meaning, and meaning carries action. That’s the definition of fashion activism.

Waste pollution in Beirut in 1982, during its civil war. (Photo: Luc Chessex)

I kept on going because I was extremely convinced having lived in the Middle East and having seen the rise of fast fashion post-war—seeing the first stores that opened up after the war ended were Zara and H&M and Mango and all of these fast-fashion stores, along with the fast food chains like McDonald’s and Burger King. There was this idea of, “Oh, we need to catch up. We need to catch up to modernity.”

Even our clothes started to change to portray that we’re “modern.” What does that even mean? Our traditional wear was left in the closet, so that we could wear jeans and crop tops and all of these things that made us look “modern.” So fashion to me was was not only a form of expression, it was a political tool to really differentiate yourself and to have a statement of where you’re at on your political beliefs.

Especially in Lebanon. We have over fourteen different religions. Whatever you’re wearing has a very specific meaning of what you’re trying to say, your status, your religion, and even your political influences. When I was observing that as a young teen, young adult, and articulating that fashion could be used. It’s a medium, just like design is. It’s a medium that we can use to raise awareness, but also to change the systems that are impacted around fashion. So a T-shirt that says we should all be feminist, and that very same T-shirt is exploiting women around the world, in the Global South, where they don’t even get to be paid a fair living wage. How are we being “feminist” with that T-shirt? Who gets to be a “feminist”? So all of these questions came around the body of work of fashion activism.

SB: A lot of layers. [Laughter]

You’ve previously mentioned the idea for Slow Factory basically came out of an identity crisis. I was wondering if you could—

CS: You did your research.

SB: I was wondering if you could elaborate a little bit on what that identity crisis was specifically?

CS: So after giving birth to my first child—and again, I wasn’t someone who was planning to have a family, I was deeply involved in my work. I was working in digital literacy, access to technology, access to information, working closely with the Creative Commons groups in the Middle East, but also in North America. Kind of bridging the gap, as we say, between East and West.

After my first child was born, I felt like all of the work that I was doing in the digital space needed to have a bigger mission than just access to information for the sake of information. At the same time, NASA had joined the Creative Commons. I was just sitting and looking at these images of the Earth during the day, the Earth during the night. The project was called Images of Change, and it’s a project that NASA has where they’re documenting the earth during the day, but comparing it year after year. You could see the erosion of the land or drought occurring. All of these things, when I looked deeper into them, they were tied to cities that were producing for fashion. They were producing for cotton. They were cotton fields, or related to cotton fields, or they were related to places where there was lots of fabric production—where they needed water to produce these fabrics at scale.

“That’s how I began working in fashion by accident. It’s because I wanted to materialize the immaterial and wrap people with these images—wrap them with the world so that they really can feel connected to it.”

I thought to myself, These images are digital. They’re very far away from us. They’re not in a physical space. Can we materialize the immaterial? How would it be if people could actually feel these images? What would it look like? I began the inquiry in my little notebook. I was actually in Lebanon at the time, and I was like, “I want to change what I’m doing. The digital space is wonderful, but I think we need to materialize it. We are too disconnected from the world that we live in.”

Even now, ten years later, with the metaverse and everything, we’re going further and further from nature. At the time, I had Slow Factory—the [.com] domain name—because we had bought it even in 2008 just as a commentary to how everything was fast, fast, fast. Everything that we were invited to work on was around fastness. Everything must be at the tips of your fingers. Immediately. You have to get it right away. I started to develop the concept around Slow Factory. How can we materialize the immaterial? Could we be printing these images on, perhaps, fabric? But how could I be printing images on fabric without destroying the planet or engaging in forced labor or unpaid labor? That’s how I began working in fashion by accident. It’s because I wanted to materialize the immaterial and wrap people with these images—wrap them with the world so that they really can feel connected to it. That’s how basically I started to see that it was about systems—How do I even source these materials?—and so on.

SB: Well, it’s so interesting you bring this up because it makes me immediately think of the overview effect, which is something you’ve talked about. It’s something that I think is so central to the conversations we should be having on Earth related to home and how we define that. I was just wondering if you could talk a little bit about this cognitive shift that happens and the impact it’s had on your thinking. I mean, obviously this is something that Stewart Brand did with Whole Earth Catalog, and was thinking about through that sort of early Silicon Valley lens. But what’s your fascination with this notion? What impact do you think the overview effect could have if everyone thought about it in their day-to-day?

Astronaut Leland Melvin floating in the International Space Station. (Courtesy NASA)

CS: This was all about connecting the dots for me. I left my country at the very young age of 5 as a refugee. I remember seeing the earth from the window of the plane and feeling both disconnected from my land. Of course, I felt deeply uprooted, but also connected, in a very big way, to humanity. I feel like I’ve always felt this idea that I’m a citizen of the world, just looking at the earth from not space, but from very high up in the plane.

Fast forward, a long time ago, or many years later, to a deep conversation with my dear friend Leland Melvin, who was a NASA astronaut. He was sharing with me his overview effect experience, of him being in the International Space Station and breaking bread with people from all over the world. Even people considered enemies of the United States, if you will, because they were with Russians and they were with all sorts of people from around the world. Breaking bread in space in the International Space Station, and looking at the Earth from space, and this cognitive shift—it’s almost like a chemical reaction within the brain that suddenly understands that we are all in this together. We’re floating in space on a rock. How magical is it?

SB: Spaceship Earth.

CS: Yes. It could be compared to taking a plant medicine and having an experience like that where you can make these connections with your brain that, Oh my gosh, we’re all connected. We’re all part of this world. We were just exchanging notes of me as a young child, watching the Earth from the closest I’ve been to space, which was a big, big cloud. Then him—and just these conversations—have helped me shape a lot more this idea that, in any case, what we’re talking about here is climate justice. We’re talking about human rights. These concepts can only be understood on a cultural level when we are understanding them in an empirical way. We can rationalize it. We can talk about it from an academic sense. But people don’t really get it until they live it, until they live it in their bodies.

SB: Feel it.

“We’ve had enough of the doom and gloom.”

CS: Feel it, exactly. So how can we make people feel this in a way where they open up on a compassion level, on an empathic level. They put their skills into action in a way where it doesn’t feel that it’s coming out from guilt. It’s coming out from love. Those were the questions we were trying to explore, if you will. Behind the scenes at the Slow Factory, that’s basically all the conversations we have. Even recently with the situation that happened this week, with the [Uvalde, Texas] school shooting and the shootings in Buffalo, it’s easy to say nothing’s going to change. Nothing’s ever going to change. Feeding into this idea of doom and gloom. We’ve had enough of the doom and gloom. There have been so many studies that looked at the doom and gloom rhetoric and connected it with apathy, connected it with inaction. It really does not inspire you to try to do anything, because what can you do?

The role that we take very seriously, the responsibility that we have with owning a big platform like the Slow Factory and having this type of influence, is that we will not be engaging in doom and gloom. We will not be adding to it. That’s also kind of connected to the overview effect because what we’re trying to build is a cognitive shift that it is actually possible to change this whole system.

Photo: Cynthia Edorh

SB: Right. You have this project that you’ll be launching soon, “Applied Utopia,” which connects directly to this. Could you share a bit about that?

CS: Absolutely. This has been a project we’ve been researching for the past two years. This idea of applying utopic ideas—utopia—so it’s called “Applied Utopia.” It’s a residency at Central Saint Martin’s that the Slow Factory will be leading in October, which we are very excited about. There will be a lot of design fiction, speculative design, where we’re projecting the public into a near future that is possible, that is a utopic future.

If we achieve that in a speculative design sort of way, can we reverse design this back to today? How did we get there? What are the steps that we took? It’s, again, around radical imagination. It’s around this idea that we are not only giving ourselves permission, but we’re also engaging with inexpensive thinking. We’re really refusing this idea of negativity. Of course, it’s so easy to say, “Nothing’s going to change and we’re all about to die.” We’ve already explored this scenario at length. Okay, there’s so many books about this. There’s so many movies about this. It’s a very wide perspective that has been dominating. But what about the Global South energy? What about the Global South perspective? That things are not as bad as they seem, and, to quote my peers at NDN Collective, “What if the best days… are ahead of us?” Which is their ethos.

SB: Just look at Indigenous culture. They’ve been existing for hundreds and thousands of years in these cultures and societies that self-sustain.

“What if we could change everything? Where would we start?”

CS: A hundred percent. Actually NDN Collective is an Indigenous-led group. I don’t know if you’re familiar with them. They’re wonderful. An amazing, super powerful group. They recently published a book called Required Readings. And the first sentence within the book is, “What if the best days… are ahead of us?”

SB: That’s great.

CS: That’s how we operate as well within the Slow Factory: First of all, there are more days ahead of us [than there are behind us]. Second of all, what if we could change everything? Where would we start? What if, to build on the works of so many before us—Frantz Fanon and Paulo Freire, and so many ahead of us—what if the last colonial cop were to disappear? What are we building from that point on?

SB: Will failed utopias be a part of this? I imagine you at least have to acknowledge that there have been so many failed examples of what we might define as “utopia.” Although the “we” there I’m saying has typically been white, wealthy northerners. So it is a sort of particular “we.”

CS: We are going to allow ourselves to make mistakes and to fail as well. I don’t think we’ve had that privilege to try and fail. As a child of refugees and immigrants and first generation war survivor, I was raised with the idea that you cannot fail. You cannot fail this. You have no chance. You have one chance. I feel like a lot of us coming from the Global South, we live with this urgency and also with this idea that we’re not allowed to fall. We’re not allowed to fail. We have to be perfect. We have to be irreproachable. We have to be on our best behavior. I would like to challenge that notion and say that we are allowed to make mistakes. Let us build a utopia that falls to its knees. We will have learned so much more than if we never tried.

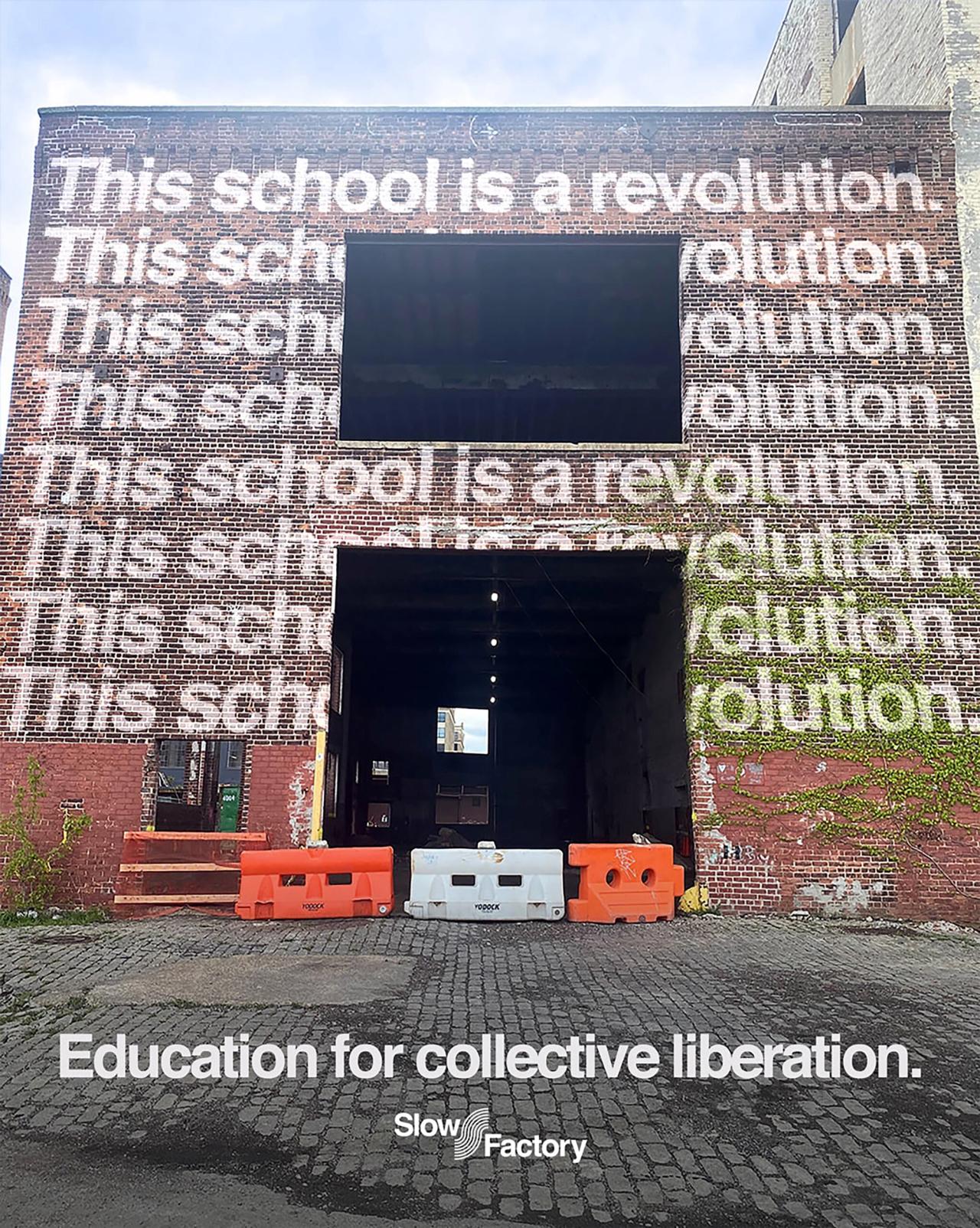

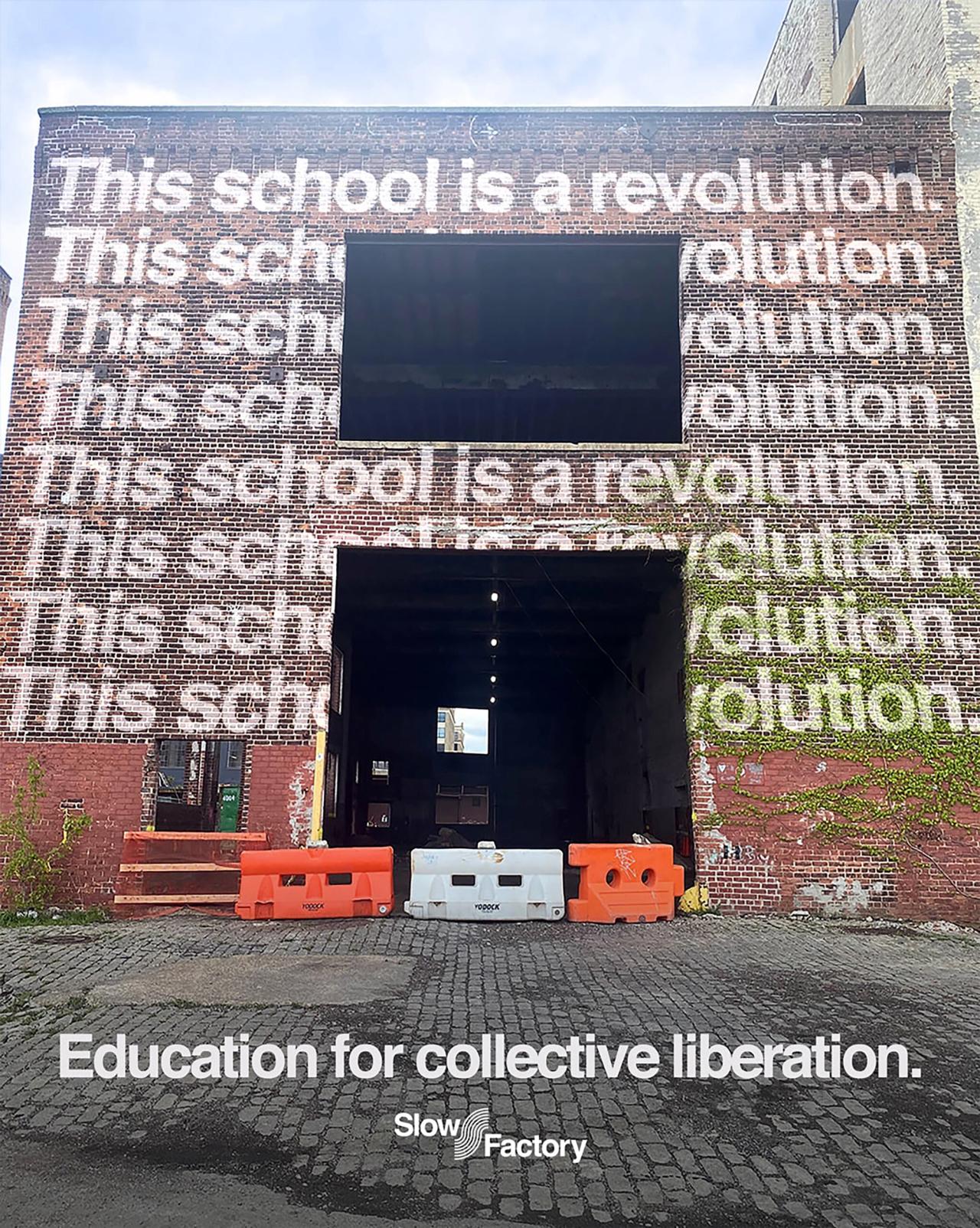

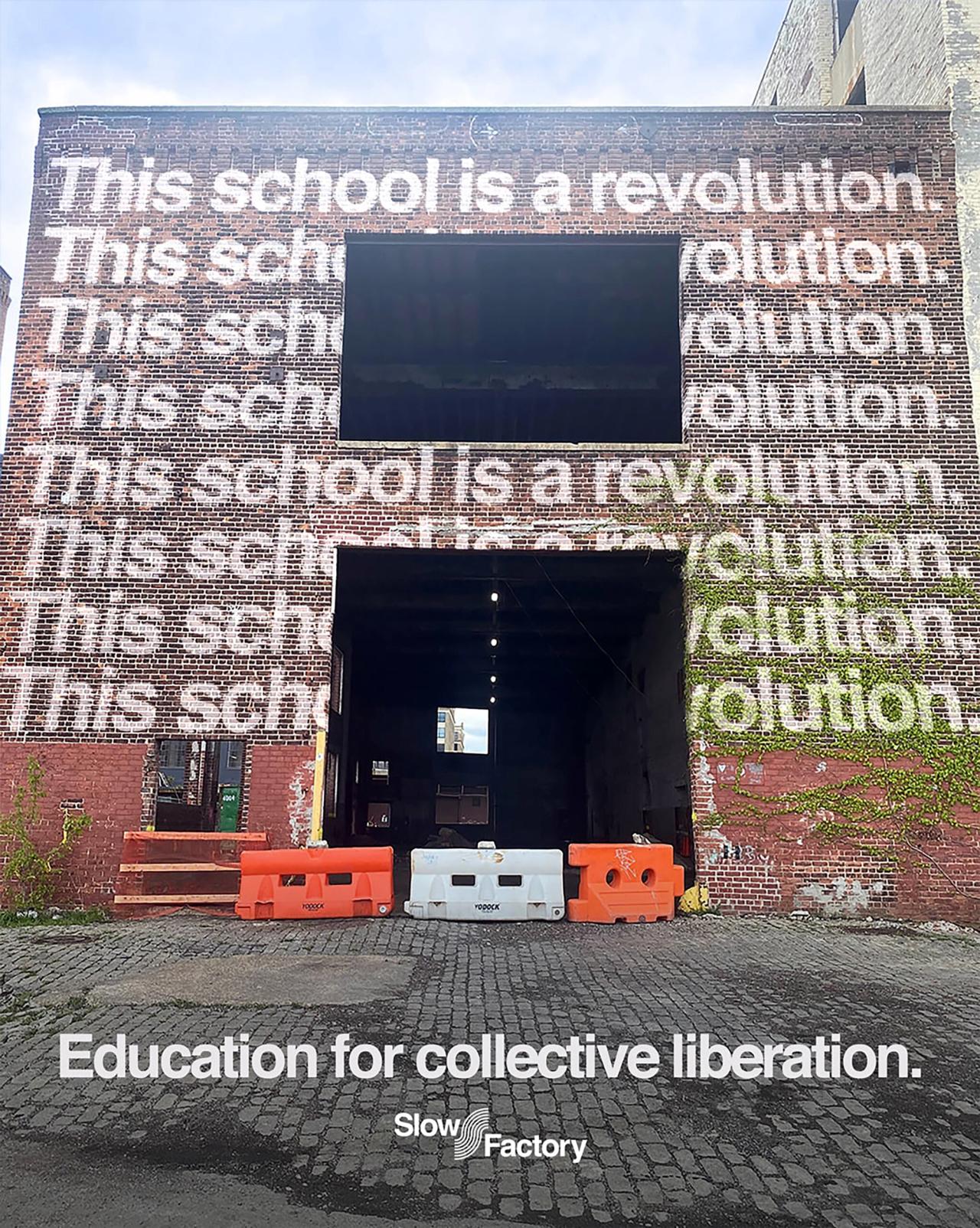

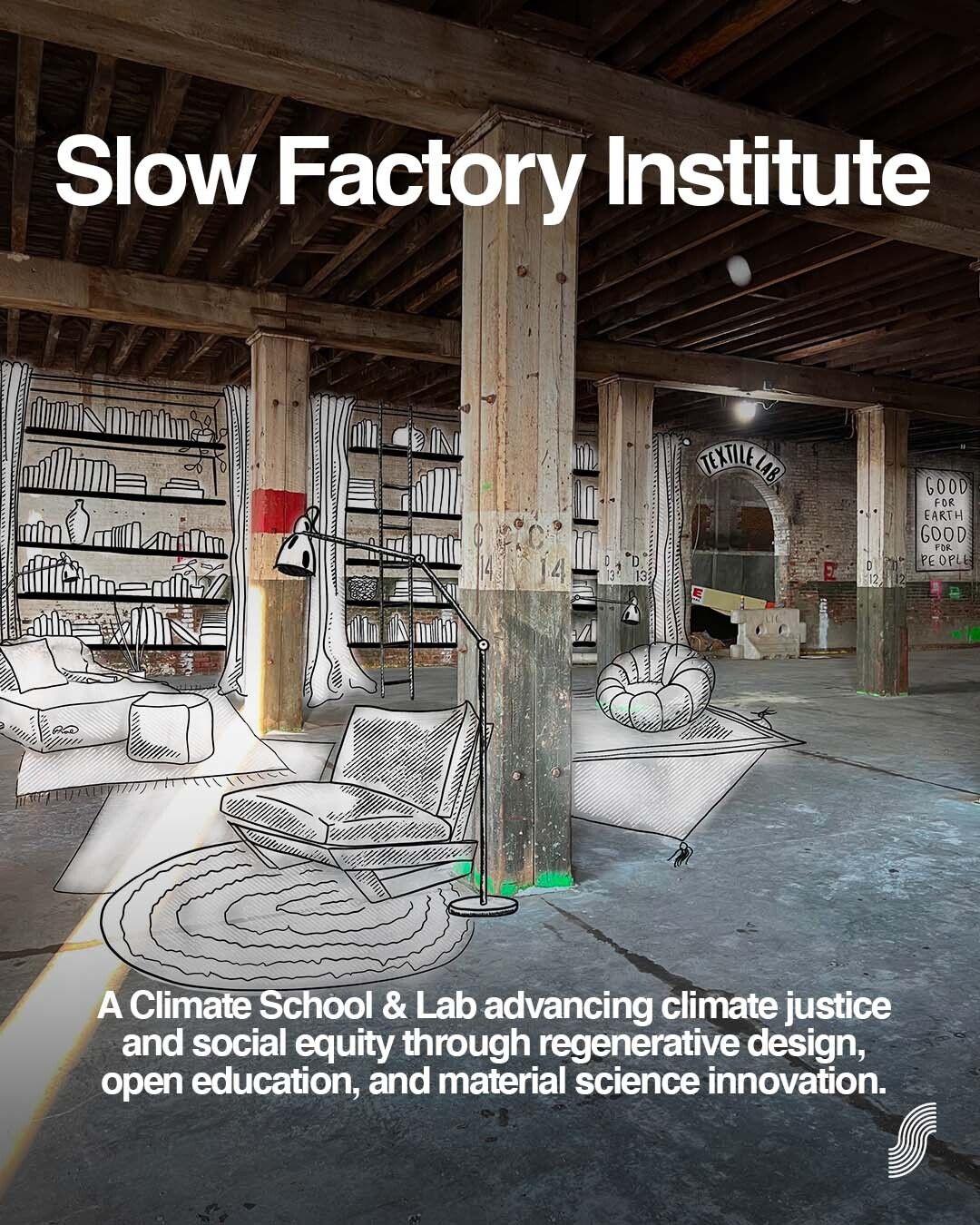

SB: You’re currently building this Slow Factory Institute at Bush Terminal in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, and this will provide educational programming, workforce training. There’s a product studio, an R&D lab, all of this under one roof. Basically, a full-fledged factory. [Laughs]

A sketch of the plan for the Slow Factory Institute over a photo of the space mid-construction. (Illustration: Paloma Rae. Courtesy Slow Factory)

CS: Yes!

SB: I’m wondering, did you ever imagine that Slow Factory would actually have a factory? What’s your vision for this project?

CS: A hundred percent. I feel like I start every sentence with “a hundred percent.” And if I’m really approving of what you’re saying, I would go to “one million percent!” [Laughs]

Yes, I feel like the dream of the Slow Factory was to have multiple factories around the world. They would be a little bit like a Willy Wonka factory where, on the one hand, we’re inputting waste and then we output new systems and new products that are waste-led designed. That was the concept since the beginning. I remember when my partner, Colin Vernon, last quit his tech job, and they came home and they were like, “We’re building the factory. I found a place. We’re going to build the Slow Factory. We’re doing it.” That was actually the first step that I felt like, Oh, it’s going to happen. We’re going to make it happen.

The best way I could describe the Slow Factory Institute in Brooklyn is basically a Bauhaus for climate justice. It’s applying design thinking, applying design as a discipline to the climate issue because pollution is by design. Injustice is by design. Honestly, it did not happen by accident. It’s not like the Big Bang. It’s like, Ooh, we have pollution suddenly. It was designed this way. I mean, pollution is legal. This is a concept that I always say, “Wow, that’s so true. We have legalized ourselves to pollute.” At school, in design school—whether you’re working in fashion or product or anything—you’re designing with the authority that you are allowed to pollute. This is just how it is. At the Slow Factory, we are looking at it in a different kind of way. So it’s applied climate justice within the framework of design as a discipline where we are implementing waste-led design.

“Pollution is by design. Injustice is by design.”

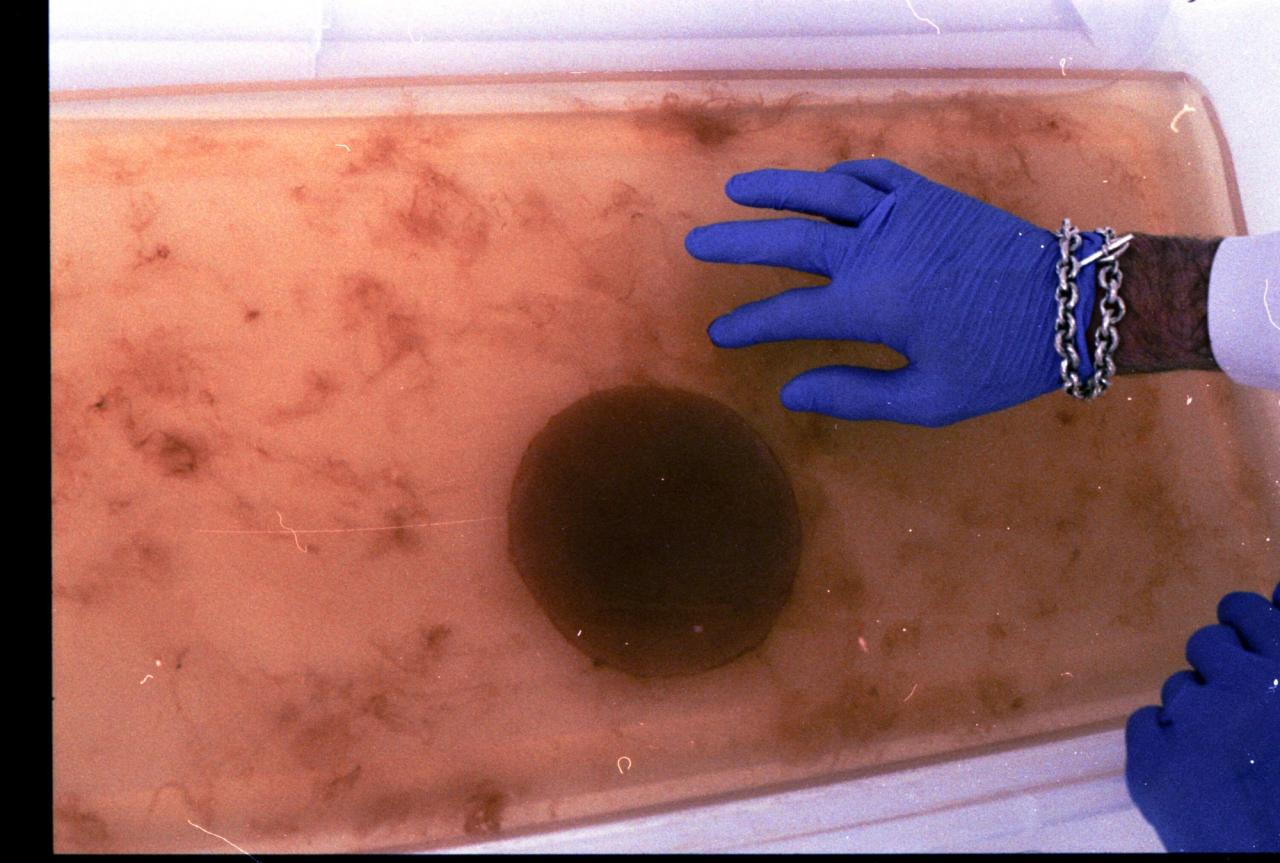

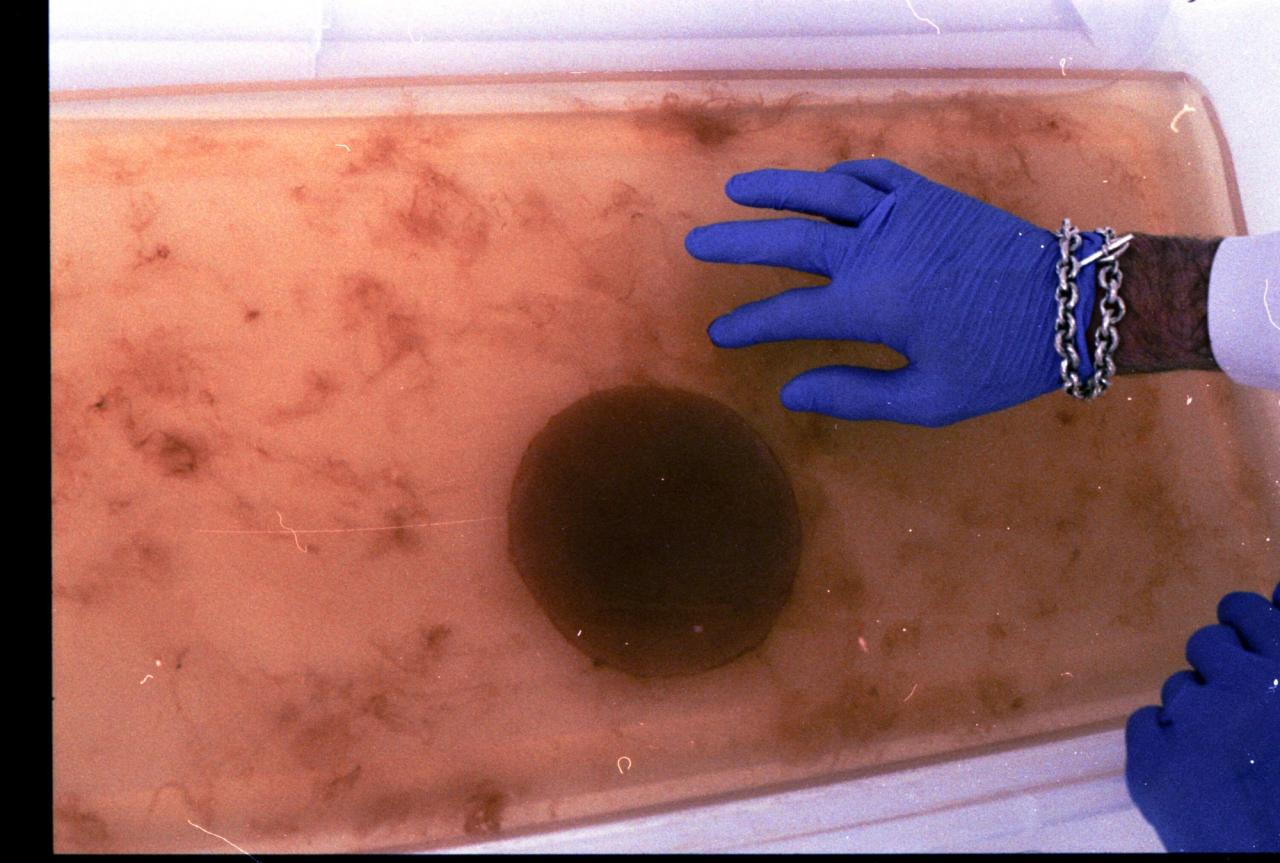

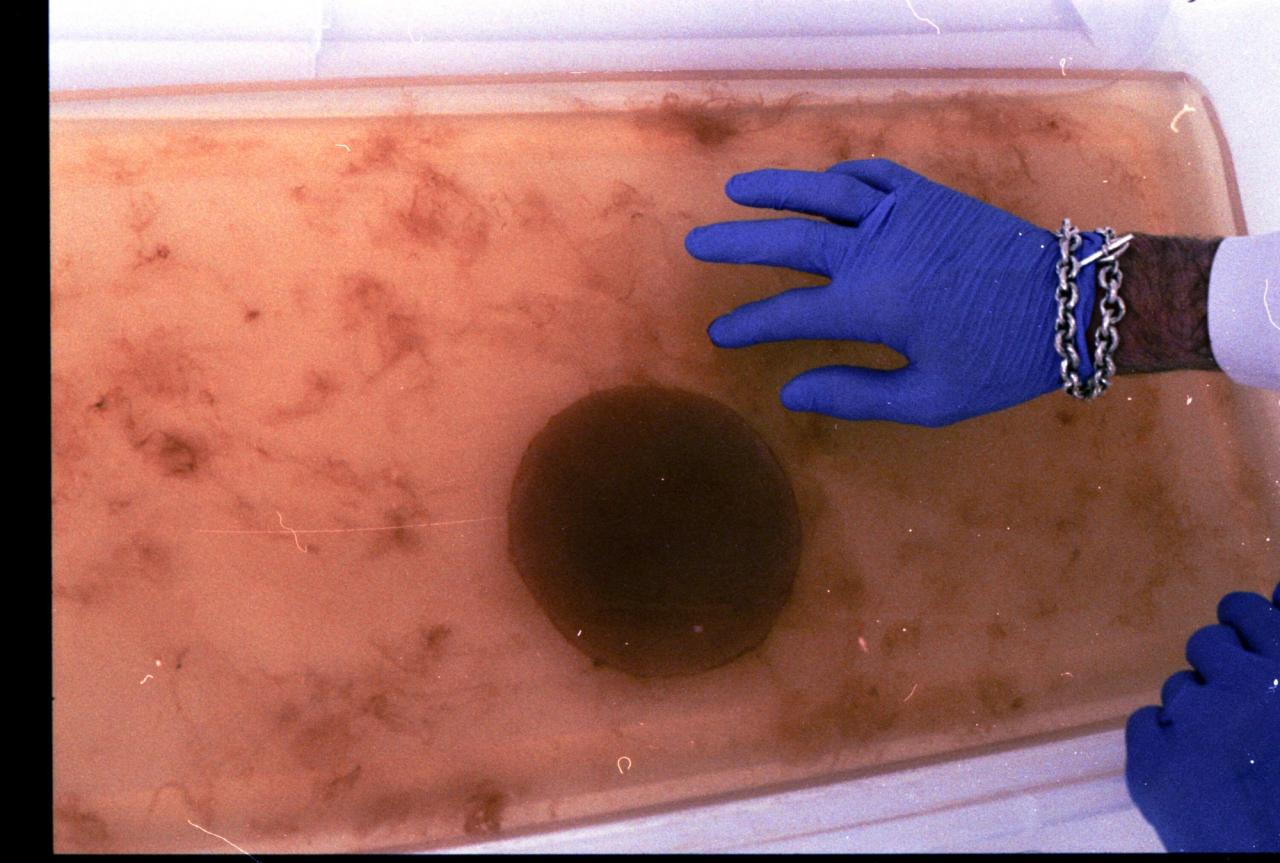

Everything that we’re doing is built on waste streams. We’re taking five tons of textile waste monthly, and we are going to be turning that into furniture, into clothing, into all sorts of things. That amounts to sixty tons of textile waste per year, which is wonderful for a small institute like ours. In the lab that you mentioned, we are building a new material—we’re actually not building it, we’re growing a new material. The input is tea and coffee waste, and God knows that New York City has enough tea and coffee waste to feed us in this endeavor. The output is a new leather, a bacterial nanocellulose leather, that’s called Slowhide. One word, like cowhide: Slowhide. We are growing it to work with furniture companies, car companies, and also fashion companies in replacing the leather that we’re currently using—whether it’s animal leather or plastic-based leather—with this Slowhide material.

The Slowhide vegan leather being developed in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Semaan and her partner, Colin Vernon, developing the Slowhide vegan leather in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slowhide vegan leather being developed in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slowhide vegan leather being developed in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Semaan and her partner, Colin Vernon, developing the Slowhide vegan leather in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slowhide vegan leather being developed in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slowhide vegan leather being developed in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Semaan and her partner, Colin Vernon, developing the Slowhide vegan leather in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slowhide vegan leather being developed in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

SB: I’m so interested in this Bauhaus idea. It’s something Andrew and I have thought a lot about. There was the Bauhaus. There was Black Mountain College. There was Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog. There was Buckminster Fuller and “Spaceship Earth.” There was a lot of this fascinating thinking happening. And then what? So I’m just curious how you’re thinking about it in this context of climate and human rights. In your mind, what does a modern-day Bauhaus look like?

“Design as we know it has been an extension of this colonial aesthetic.”

CS: It’s basically taking design back. For instance, a lot of these concepts are revolutionary in the space of design and the discipline of design. But design, if you look at it, has been extremely exclusionary of other voices, other talents, other perspectives. Design as we know it has been an extension, if you will, of this colonial aesthetic. At Slow Factory, we articulate it as the “oppressive aesthetic.” It’s the aesthetic that basically overwhelmed everything else. It was the aesthetic that defined modernism. Modernism is a key concept in the expansion of the colonial empire—the erasure of Indigenous cultures from the Global South, essentially. So what we are doing is we are taking back design. So Slow Factory uses Helvetica, but almost like against Helvetica as well. [Laughs]

The idea for us of Bauhaus—of using and taking back the concepts of Bauhaus—it’s not only reclaiming it, but it’s taking it back. It’s basically, what could we build with this concept, but from the Global South’s perspective? What could we be building with these concepts with an Indigenous-led movement? What does it look like with the Landback movement? Can we implement this? Could it serve us in our mission? Could it serve us in this revolution that we’re designing and building?

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

A sketch of the plan for the Slow Factory Institute over a photo of the space mid-construction. (Illustration: Paloma Rae. Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

Semaan at the Slow Factory Institute construction site. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

A sketch of the plan for the Slow Factory Institute over a photo of the space mid-construction. (Illustration: Paloma Rae. Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

Semaan at the Slow Factory Institute construction site. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

A sketch of the plan for the Slow Factory Institute over a photo of the space mid-construction. (Illustration: Paloma Rae. Courtesy Slow Factory)

The Slow Factory Institute mid-construction. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

Semaan at the Slow Factory Institute construction site. (Photo: Cynthia Edorh. Courtesy Slow Factory)

These are the questions we’re asking. Of course, there’s always a fine line in taking back anyone else’s discipline for our own collective good. Of course, there are a lot of questions that we’re asking behind the scenes. But it’s actually very freeing to be able to imagine this world, imagine the school, and use these concepts behind Bauhaus house for climate and human rights justice. There’s something that’s almost, I would say, defiant, that makes me feel very joyful about it.

An advertisement poster for the Slow Factory Institute. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

I know from the fact that over twenty-eight thousand students that we work with, none of them come from a traditional design background because design has always also been very exclusionary. I’ve been personally rejected from every single design school I’ve applied to when I started my career. The feedback I got was, ”You’re too conceptual. You need to go into the Beaux Arts. You need to go into arts. You’re not a designer. You’re too conceptual.” And I was always like, “No, no, I really want to work in design.” [Laughter]

So to be able to build our own design school feels very defiant, but kind of joyful as well. The fact of the matter is that we’ve seen so many of our students feel so empowered by understanding these concepts that are otherwise left to a certain group of people. A lot of our students are like, “But I’m not a designer. I’m not a designer.” I’m like, “But you’re making so many design decisions, whether you know it or not. You’re making these decisions, and they’re design decisions.” So that’s been very productive for us to see that being adopted by more people than just designers.

SB: Yeah. I think “design” as a term just gets too often put in a box because certain people in power and control put it in a box. Your mentioning of “oppressive aesthetics” got me thinking of a phrase by B. Ruby Rich, which is “prophetic aesthetics.”

CS: Wow.

“Whoever’s going to find this planet is going to be able to understand us based on the landfills that we’ve built.”

SB: Prophetic aesthetics definitely connects to a lot of your work. I’m thinking here of your “Landfills as Museums” project, which is a way of sort of meditating on: What is waste? What is trash? Does it even exist? Could you share a little bit more about this? I think people forget the volume of waste that we create, that literally piles up every day, every year. Just to put a figure out there, according to the World Bank, global waste is expected to grow by seventy percent by 2050. Staggering.

CS: Staggering. And we’re running out of land to store this waste. So it’s happening here in New York City, actually. Communities around landfills are advocating against having someone come in, dig a big hole, destroy the whole ecosystem of that region, dry up all of the rivers, to basically bury our waste. The concept of “Landfills as Museums” came about with the idea that this is like the archaeology of the future. This is what we’re leaving behind. Let’s say there is the end of the world. Let’s say the apocalypse, doom-and-gloom perspectives are to happen, and there are no more humans on this planet. Whoever’s going to find this planet is going to be able to understand us based on the landfills that we’ve built, going to be able to understand our civilization, and the complete madness of our existence on this planet.

Semaan at a landfill as part of Slow Factory’s “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

I’ve always been fascinated with landfills because they are literally the archaeologies of the future. We pitched this project to Waste Management, one of the largest companies of waste in North America. Of course, they didn’t want us to go there. We had to convince them that, “No, no, it’s going to be great. It’s going to be educational. No one’s going to cancel you.” Because everyone’s afraid to be canceled. So we managed to convince them. We took the first group, as a pilot project—twenty-three designers from Adidas, from the community—to come with us to the landfills. We surveyed them before they went, and we asked them, “How does a landfill make you feel?” And the response was: ”sad,” “guilty,” “terrible,” “depressed.” “I feel so bad.” All of these things.

We took them to the landfills and watched them walk on piles and piles of waste. Things that they probably consumed that very day. Everyday objects like a cup of coffee, a yogurt box, a bra, a pair of socks, a pair of shoes, a pair of pants, a box. All the things that you’ve used in a day—a toothbrush, a toothpaste, a razor, a box of soap. All of the things, literally, and watch them meditatively walk and walk and walk. We’re walking on mountains, literally. We have to climb on it. We’re hiking on a mountain of waste. After that, we took them inside of a conference room and talked about waste-led design, within even the landfill, because the landfill emits methane. Waste Management captures this methane and turns this methane into electricity.

They create so much of this methane and so much of this electricity that they end up selling it back to the grid. Some of the New York City electricity that we have comes from these landfills. That was very fascinating.

We talked about the anatomy of the landfill. What are the layers? It’s basically built like a cake. They also were face-to-face with some of the people behind waste management. Third generation working within landfills. One of them—I think his name was Bobby Brown—was saying, “I don’t want to be building another mountain. This is my third mountain in my lifetime. I don’t want to be digging up a hole anymore.” Of course, this experience brought tears to not only the designers, but also waste management folks were crying. It ended up in hugs and tears and so much emotion that happened during that day.

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

Image from one of Slow Factory’s trips to a landfill as part of its “Landfills as Museums” project. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

We surveyed them on our way home. “How does a landfill make you feel?” The answers were: “hopeful,” “empowered,” “inspired.” They were very much more empowered to do something about waste than whatever they were thinking about before going to the landfill. We did it two or three times, and then the pandemic started, sowe had to put this project on pause. We translated it into a digital interface—you could see it on slowfactory.earth/landfills-as-museums, where you could experience it in a way where we’re trying to guide you through the experiences. It’s of course not the same as being there. There’s a documentary at the very end that also helps you understand what happens when you walk and meditate on a landfill. What happens when a designer is involved in thinking about the end of life first, before thinking about functionality or aesthetic?

“As designers, we work around constraints pretty well. If we were to understand the constraints, I think we would be even more creative.”

I also wrote about ecosystems over aesthetics. I even got into a fight over email with an academic from Europe who was like, “They shouldn’t be over aesthetics. Aesthetics are part of design.” I’m like, “Yeah, but what if there’s no more ecosystem for you to design?” Talking about ecosystems over aesthetics doesn’t mean it’s going to end all aesthetics. But it’s also a hierarchy of priority. There should be climate justice. In fact, it’s applied climate justice. It’s looking at the constraints. As designers, we work around constraints pretty well. If we were to understand the constraints, I think we would be even more creative.

SB: You have said you don’t believe in trash, and I was wondering what a post-trash world would look like to you. How do we un-program our minds and redesign our systems around what we deem to be trash? I’m also thinking here that this is a place for you to talk a bit about regenerative design, which is so central to the Slow Factory program.

Semaan with her partner, Colin Vernon. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

CS: Yeah, a hundred percent. Such a deep question. I feel like this could be a whole podcast on its own because we’re talking about the gray area between throwing something into the trash and recycling something. What happens in between? I think that’s what the Slow Factory Institute is going to be exploring: this gray area between throwing something into the trash for it to decompose, which never happens, and then recycling it, which also never happens.

Only four percent of what we throw in the recycling bin gets recycled. Four percent. That’s in the United States. [Editor’s note: According to a recent report in The Guardian, the numbers are around 5 percent for plastic, 66 percent for paper, and 50 percent for aluminum cans.] But if you travel to the Global South and you go into these places where we are actually exporting our plastic waste to, sadly, there isn’t the infrastructure to support that amount of trash that we’re sending there—what we consider trash, because, of course, it’s trash just because we said it is. It’s not actually trash.

We’re using durable material like plastic for something that is supposed to be used within seconds and then thrown away. It doesn’t decompose. It doesn’t really recycle. So what are we doing with it? There’s this gray area of both upcycling and downcycling that we need to explore as a system in society, which the Slow Factory Institute will be dedicated to—this gray area between recycling and throwing into the garbage, of upcycling and downcycling.

Semaan and her partner, Colin Vernon, while developing biofabrics in the Slow Factory Labs. (Courtesy Slow Factory)

I can give you a bunch of examples. For instance, with downcycling, a very common example is taking both textile waste and paper and cardboard waste and shredding them and making them into industrial insulation. Instead of using plastic or harmful materials to create the insulation in buildings, that’s a solution that should be the solution. Why are we using virgin trash when we can use recycled trash to create these insulations?

Another example of downcycling is shredding these same materials and using them as filling for our furniture, filling for couches, and for car seats. So why aren’t we using that? Why are we needing to extract fossil fuel and turn them into these synthetic fibers to be able to fill our seats? They also release microplastics into the environment. We’re breathing that into our noses. So those are two examples.

In terms of upcycling, it’s basically taking two T-shirts and turning them into a dress, which is a program that we’re launching this fall. It’s called “Garment-to-Garment” and it’s teaching designers not to design from a roll of raw fabric, but to design from existing garments. Of course, the first idea that comes to mind is “Frankenstein design,” which is basically like patchwork. But can we push the aesthetic further here? Could we work with ecosystems over aesthetics and work with these constraints, push the aesthetic further so that it is not only comparable, but also, can we push the aesthetic of upcycling to the psyche of the general public for us to start accepting things that are imperfect? I just want to give an example. Balenciaga just released these terrible shoes not too long ago. They cost $1,800. They’re basically really run-down Converse.

The Balenciaga “Full Destroyed Sneakers.” (Courtesy Balenciaga)

SB: [Laughs]

CS: I saw so many of these Converse in the landfills and I was like, “Oh my God, this is almost evil and genius at the same time because what if instead of distressing the new Converse, why don’t you go fishing into the landfills? Get these Converse that are completely distressed, and sell them back to the consumer. Just create a normalized way of looking at an object in a different aesthetic.”

SB: It’s almost like an Onion article about fashion.

CS: [Laughter] Yes! But for me, when I saw the distressed Converse that Balenciaga had released, I was like, “Oh my God, this is genius. Are they taking them from the landfills?” Later on, I found out that, absolutely they are not. They’re taking new Converse and distressing them. Which I thought was a waste of energy. But that’s just me.

SB: A key component of what you’re doing, and you sort of touched on this, is climate positivity. It’s so refreshing, because I think we get bogged down when we think of the climate crisis, or the climate emergency, or the Anthropocene, or any of these terms are pretty defeating areas of engagement. There still are a lot of solutions-based opportunities and ideas and I think there aren’t enough platforms for that. So that’s one thing that I really admire with what you’re doing.

I was wondering what the phrase “climate positivity” means to you and the impact of this kind of thinking. If we could just steer a little bit further away, while not ignoring the fact that there are these really distressing factors in front of us. David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth is a book everyone should read, but that doesn’t mean that we should finish it and feel defeatist. If anything, we should want to act.

CS: Exactly. The whole doom-and-gloom philosophies are very much tied to a carceral thinking, a thinking around punishment. It’s almost like Protestant views of the world around austerity. It’s around lack. It’s around less. All of these do not necessarily lead us into innovation. You can’t really innovate from that point on. You can feel really bad about yourself and kind of stop what you’re doing and engage in austere practices, like, “I’m not going to do this, and I’m not going to do that.”

Individual thinking would have you believe that if you stopped eating meat and stopped purchasing anything new ever again, you’re doing great. But even if you did that, nothing’s going to change because it’s a systemic problem. Even if eight hundred thousand of you or eight million of you did that, we would still run with the same systemic issues. The math does not compute. So how do we create change? Because that’s the question. It’s not through individual action. It’s through collective action.

And collective action looks like not just voting. It looks like a community garden. It looks like community composting. It looks like education at school around climate justice, and then action related to that. It looks like instead of purchasing something new, hosting a swap party, or hosting a repair party, or hosting a “we’re not going to buy anything new” party with your whole community. So all of these things are interesting to us as, “How do we actually change things?” I think it’s a cultural movement that needs to happen. We need to look at it in a collective way.

“‘Sustainability’ is confusing. What are we trying to sustain? Oftentimes, the sustainability practices are trying to sustain the economic sustainability of a given company.”

But climate positivity, we didn’t invent that. I think the first time I read it was in a Fast Company article and I really adopted it for the Study Hall at the United Nations. That was the theme—“Climate Positivity at Scale”—because it was just a little bit more descriptive than “sustainability at scale.” “Sustainability” is confusing. Again, what are we trying to sustain? Oftentimes, the sustainability practices are trying to sustain the economic sustainability of a given company.

They’re going to make a small change that’s going to make them look good from a public perspective. But systemically, they’re just keeping the status quo as much as possible because that’s what their survival depends on, their survival as a company. So “sustainability” is not descriptive enough. “Climate positivity” allows us to understand that we need to be positive about the climate. What is it that you’re doing that’s actually contributing positively to the climate?

SB: It’s actionable.

CS: Yes. It’s a bit more actionable. You can hold people accountable a little bit more than “sustainability” can at the moment.

SB: Intersectionality and critical thinking are so central to this, but it does feel like we kind of have a dearth of both, these days. Education is pretty much the most logical and effective path forward. But I mention this also realizing that we do live in a moment of one-track mindedness, career-orientedness, rather than liberal-arts or cross-discipline thinking. This is to say nothing of Indigenous and ancestral wisdom that’s not being taught enough or passed down anymore. So how can we push for greater intersectionality and critical thinking amidst what is basically an M.B.A.-ization of America, and a country in which Tucker Carlson is our most watched news anchor?

CS: Yeah. Tucker Carlson did pick up on a bunch of things that the Slow Factory created, and it got us into a wave of hate mail. It was very scary. We are living in a polarized political climate where binary thinking is at its highest. It’s either good or bad. Are you for the vaccine or against the vaccine? Are you for Black Lives Matter or against Black Lives Matter? Are you for gun control or against gun control? And I’m not going to talk to you if you are in this or in that. There’s literally no nuance available to our understanding. It’s very hard to exist within these binaries.

At the Slow Factory, we’re trying so hard to create a space for understanding nuance. We’re also living in a place and a time where there’s a war on education. There’s a war on books. There’s a war on critical thinking. So of course, everything’s going to be good or evil, or black or white, or positive or negative. That’s what we’re designing at the moment when we are having a war on books, a war on women’s bodies, a war on our borders. We’re in a climate of war. We’re in a culture of war.

SB: Paola Antonelli called it the “Age of the Bully.”

CS: The age of the bully. Well, that’s interesting. I call it the “culture of war” really because it is this idea of war being completely inevitable—a climate war, a racial war, a war internationally, this elevation of the military, by all means necessary. Meanwhile, the U.S. military alone pollutes more than one hundred countries combined. This idea of weaponized states and weaponized culture is what is driving us into the abyss at the moment.

“The climate in the United States right now, this polarization, is very close to a civil war. Whether we see it or not, it is a civil war.”

This idea of the culture of war is something that I personally write a lot about because, again, having lived through a war, I’m just like, “How are we just living in a climate where we’re just inviting people to fight one another?” The climate in the United States right now, this polarization, is very close to a civil war. Whether we see it or not, it is a civil war.

SB: Yeah. It’s right in front of us. In prepping for this, I took a note of one of your recent tweets, which captures this complex—and I should say perplexed—situation that America finds itself in. It’s a pretty dark tweet. [Laughs]

CS: Just like all my tweets.

SB: But it’s a fragment, and it just hits home. You write, “The culture of war, of violence and impunity wrapped up in a white supremacist capitalist layer of plastic suffocating justice with a Crest smile, gaslighting an entire nation.”

CS: Yeah. I was very sad about the shootings that happened kind of back-to-back—the Buffalo shooting, the shooting in Austin… It’s so beyond sad, I can’t even compute. Just this morning, we were discussing it within my team at the Slow Factory. I couldn’t even get out of bed this morning. I was so sad about everything that’s happening. It really hits us. Working within the Slow Factory, as I said earlier, we’re constantly within the trauma that we are talking about.

There’s a book called Trauma Stewardship, and we tried to get the author to speak at Open Edu. Hopefully, we can get her for the fall, but that’s what we’re doing. We’re doing trauma stewardship, essentially. We’re bathing within this traumatic experience and trying to make sense of it. So when I tweeted that, it was just minutes after I heard about the shootings. I was just like, “Oh my gosh, we live in such a culture of war.”

SB: I wanted to circle back to this conversation of “home.” We’re talking about America, which is your home in the sense that it’s where you live and are planted right now, but you’ve lived in Lebanon, Montreal, Paris, and now New York. And you’re, as you said, a first-generation war survivor and child refugee. How do you define “home”?

“I came to the peace that home is inside of me, that home is within. Home is my own connection to myself and to my surroundings.”

CS: For my entire life up until now, and I’m turning 40 this year, I’ve been struggling with the notion of home, just like any uprooted person. I feel it’s a very universal question for anyone that had to flee someplace and had to watch their childhood memories burn or disappear. Everything is in a shoebox, literally everything that was able to be salvaged. What is home? You go home if you have the chance to, but some of us can’t even go back to their home because their home is still occupied.

But if you do go back home, you realize that you’re not really “home home.” You were the one who left, so are you home? I struggled with this my whole life. In my spiritual practice, I kind of came to the peace that home is inside of me, that home is within. Home is my own connection to myself and to my surroundings. I always say that my roots are in a terrarium. They’re not planted, even if I’m here. I’m a guest here. I’m on occupied land. I’m on unceded territory. How can I plant myself fully?

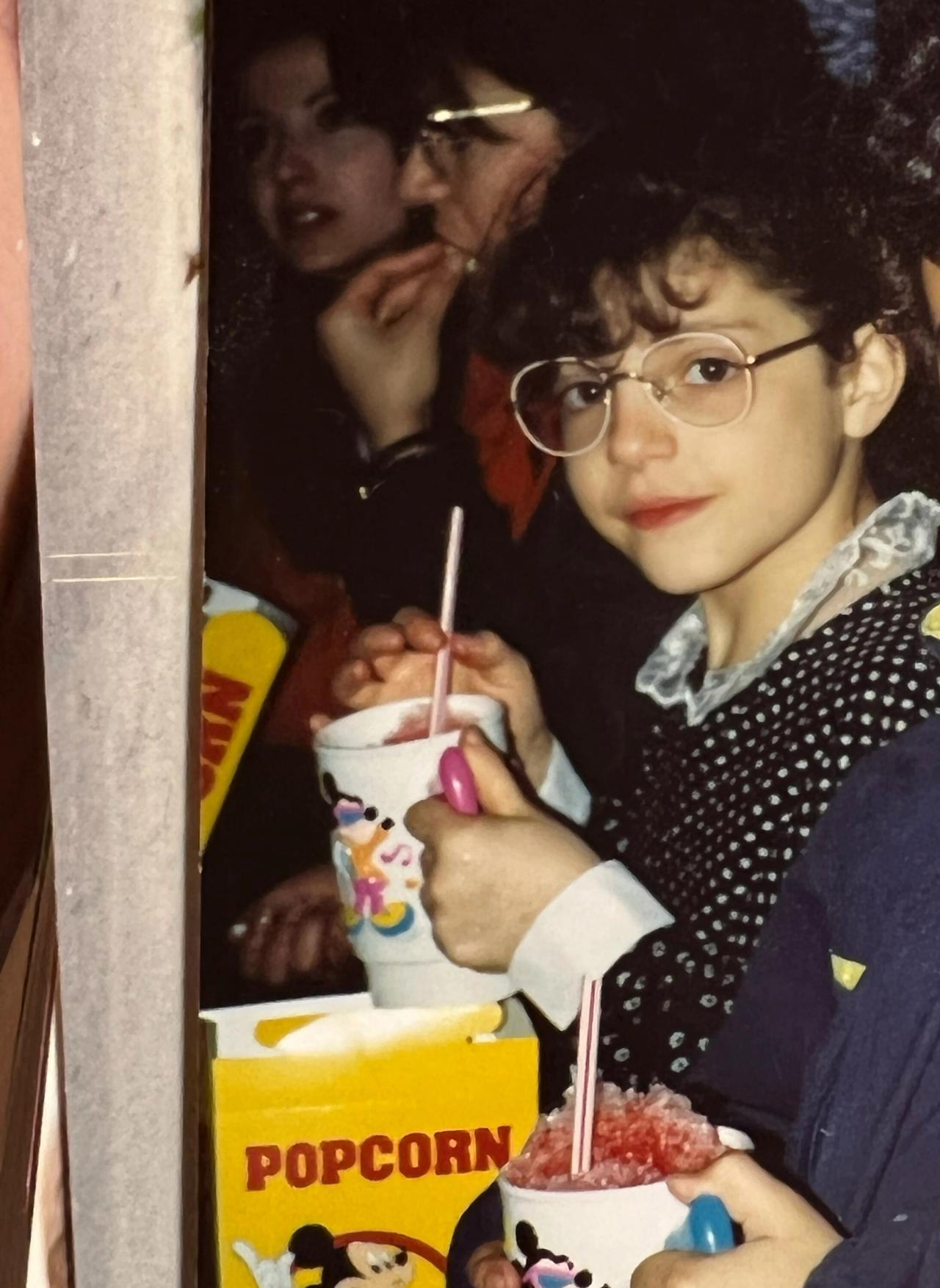

Semaan (left) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Beirut. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

When I go home to my country, my roots have changed, and they don’t fit the soil anymore. So home for me is something I explore constantly. I think as an artistic practice, it’s my eternal question: What are we considering as home? I think that’s where the notion of nature and climate justice and all of these things that are in my work, come to life. Because when I am in nature and close my eyes, I feel at home. It’s ephemeral because then I come back and I’m like, “I’m not at home anymore.” I think it’s an eternal question. The best answer for me is home is inside you.

SB: Tell me a bit about your upbringing and family. What are some of the early memories you have, whether that’s in Lebanon or arriving in Canada with your parents in the late eighties?

CS: I remember one of my earliest memories is me in Lebanon dancing Arabic on tables, surrounded by adults in a shelter just encouraging this joyful moment to happen. Then feeling threatened, feeling rushed into a place, and then traveling. Another memory is traveling and trying to get all of the plush toys with me as much as I could, and running after my mom who was carrying my sister in the airport in Beirut. My mom was like, “You can’t carry all this!” “No, but I want them.” I’m running and running and seeing all the plush toys that I couldn’t carry fall behind me. I’m looking back and all of them are falling behind. I managed to get just one elephant with me to Montreal. Then the elephant fell behind the couch and burnt his trunk on the heater. And I really wanted to keep him. Of course, my mom threw him away as soon as she could. Which was very sad. I can’t believe she did that.

Semaan (left) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Beirut. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

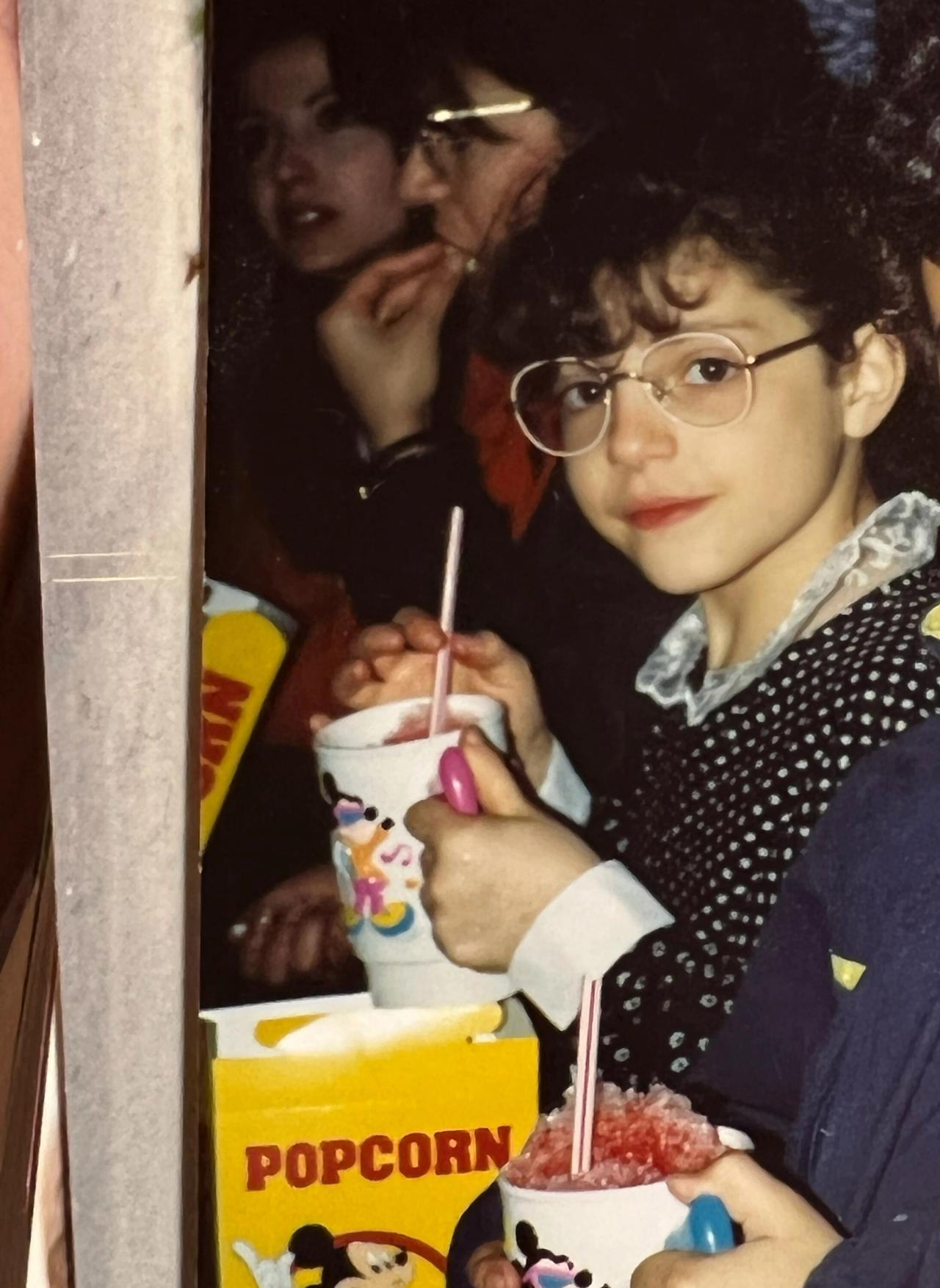

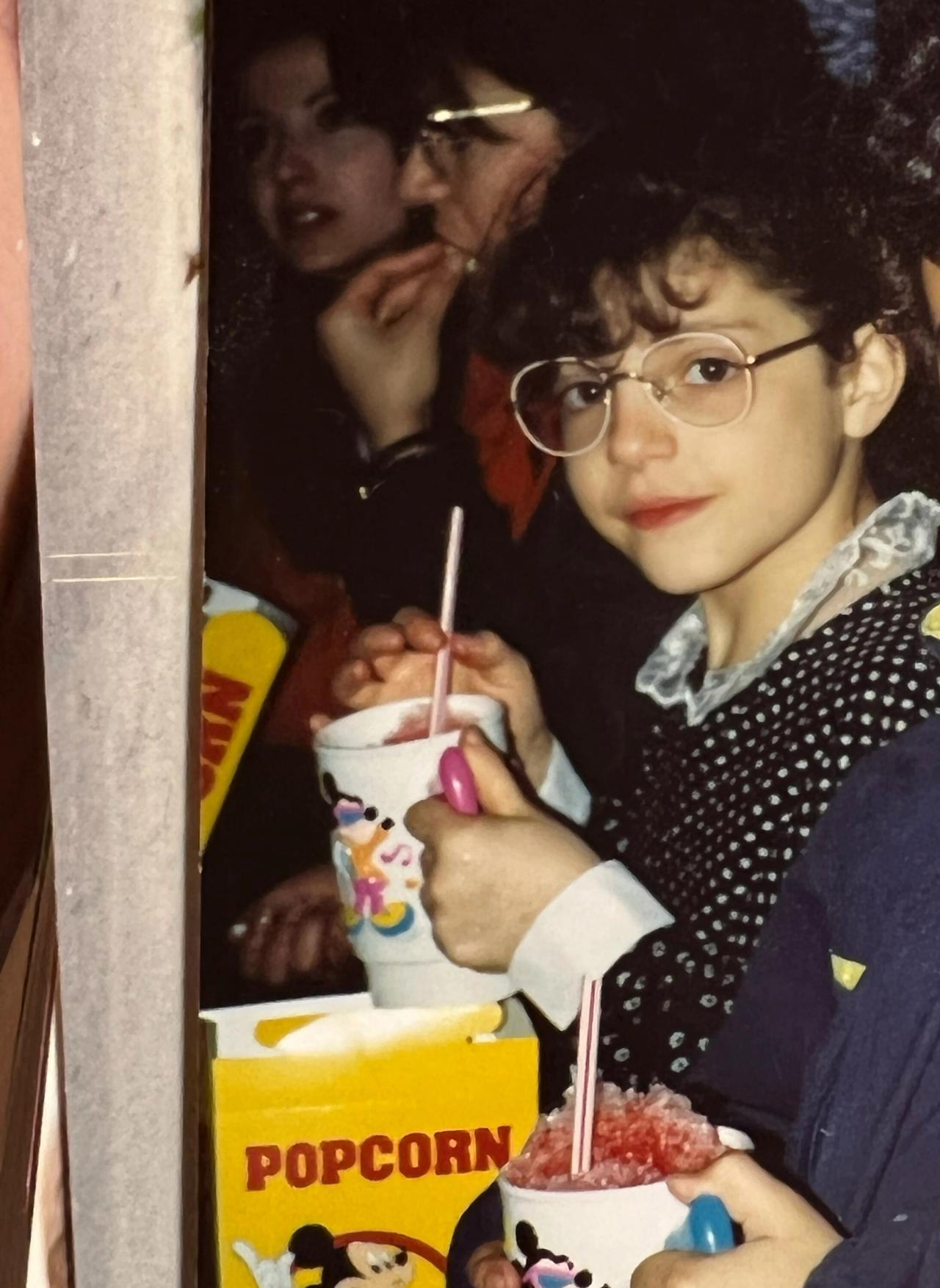

Semaan in Montreal during her childhood. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

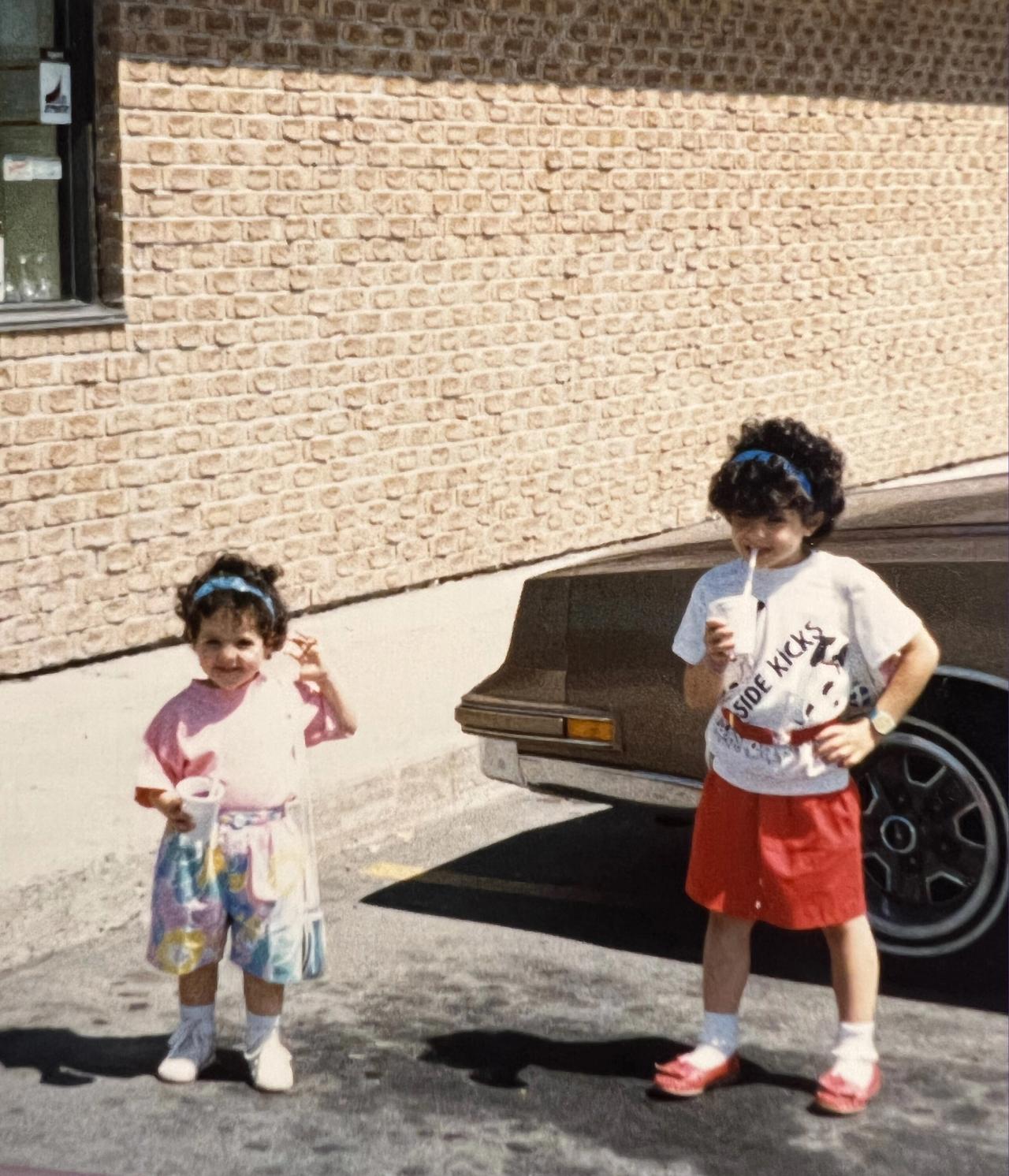

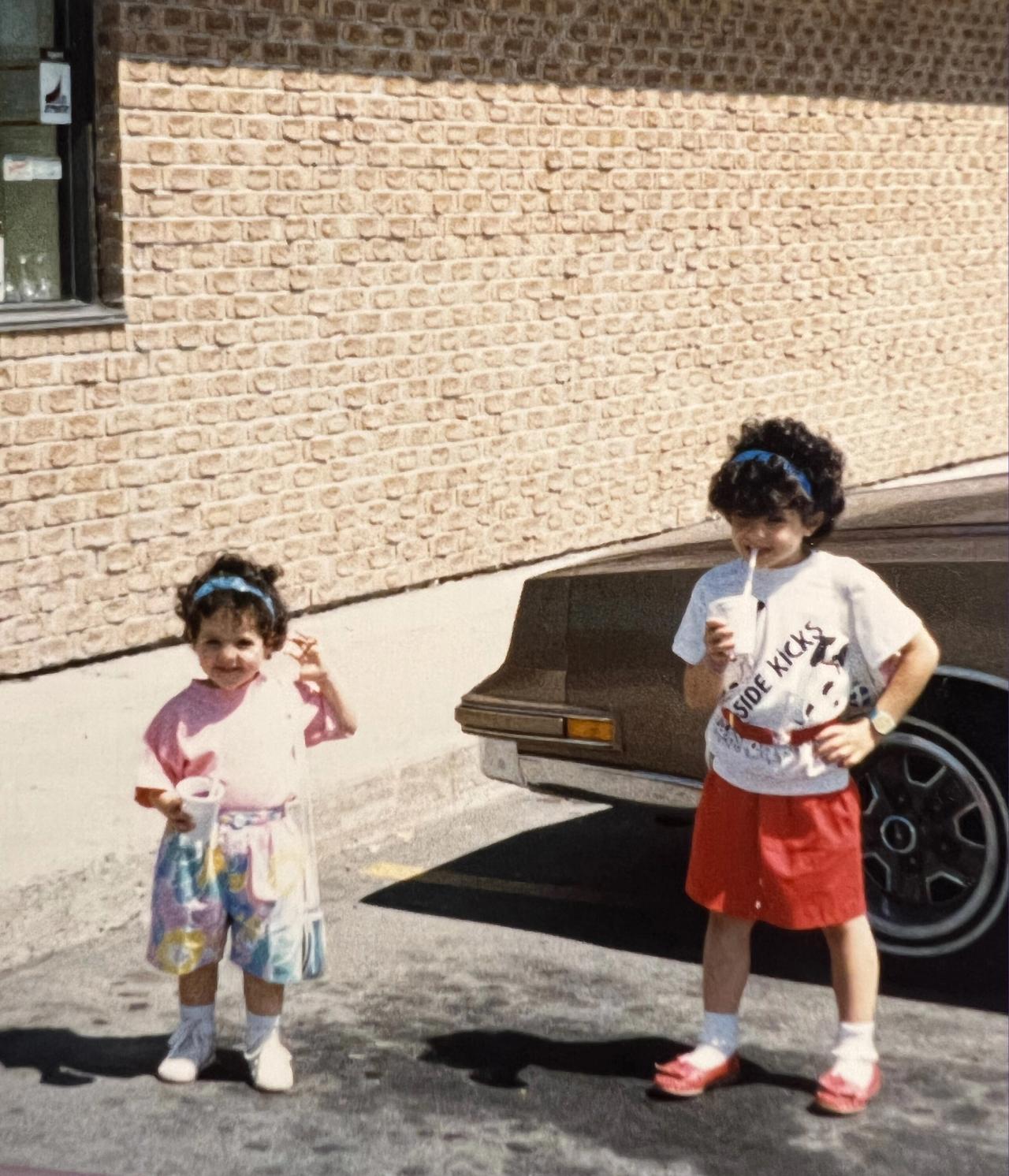

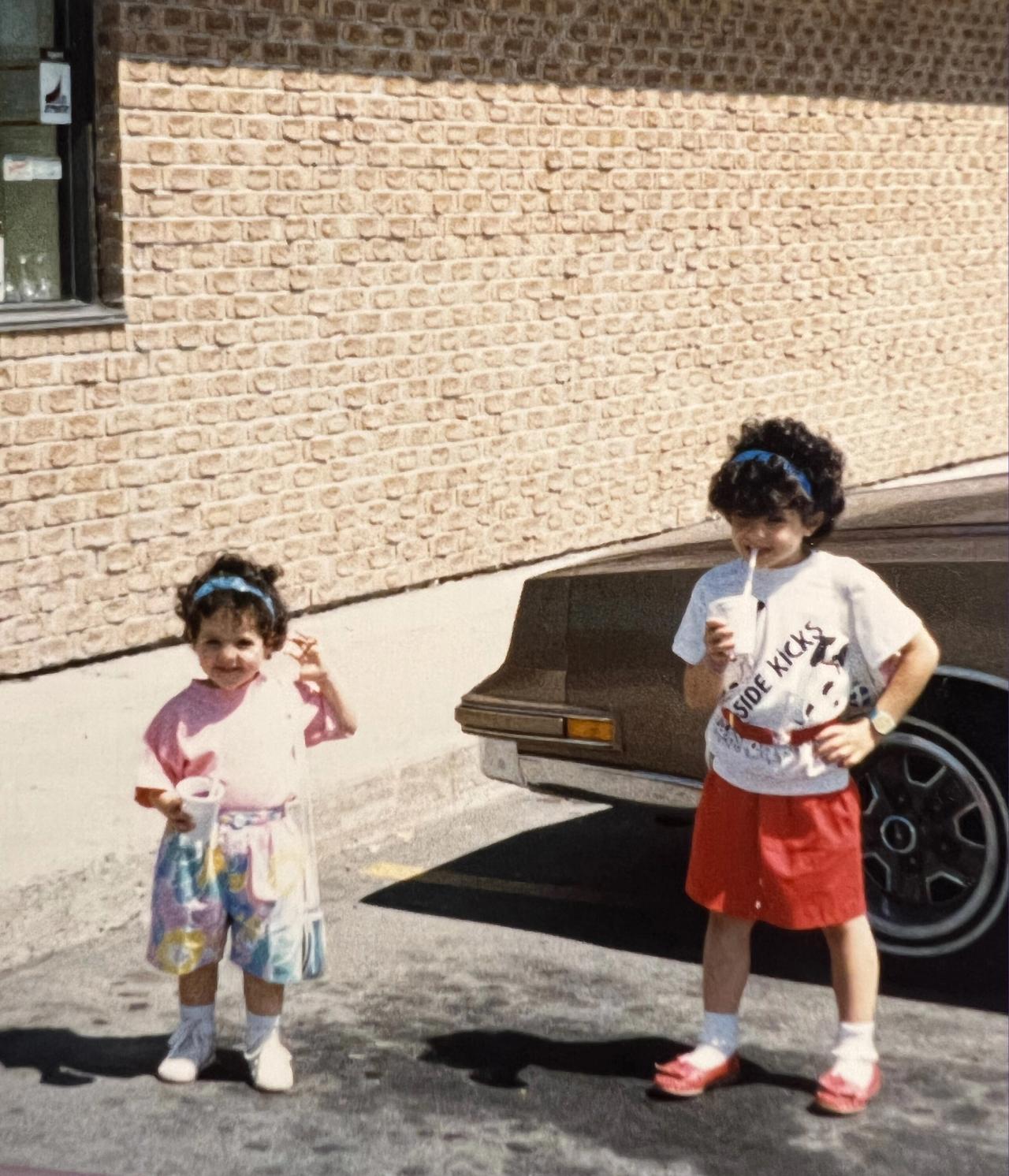

Semaan (right) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (center) and her younger sister, Laeticia, with their mother in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (right) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (left) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Beirut. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan in Montreal during her childhood. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (right) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (center) and her younger sister, Laeticia, with their mother in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (right) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (left) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Beirut. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan in Montreal during her childhood. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (right) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (center) and her younger sister, Laeticia, with their mother in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

Semaan (right) and her younger sister, Laeticia, as children in Montreal. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

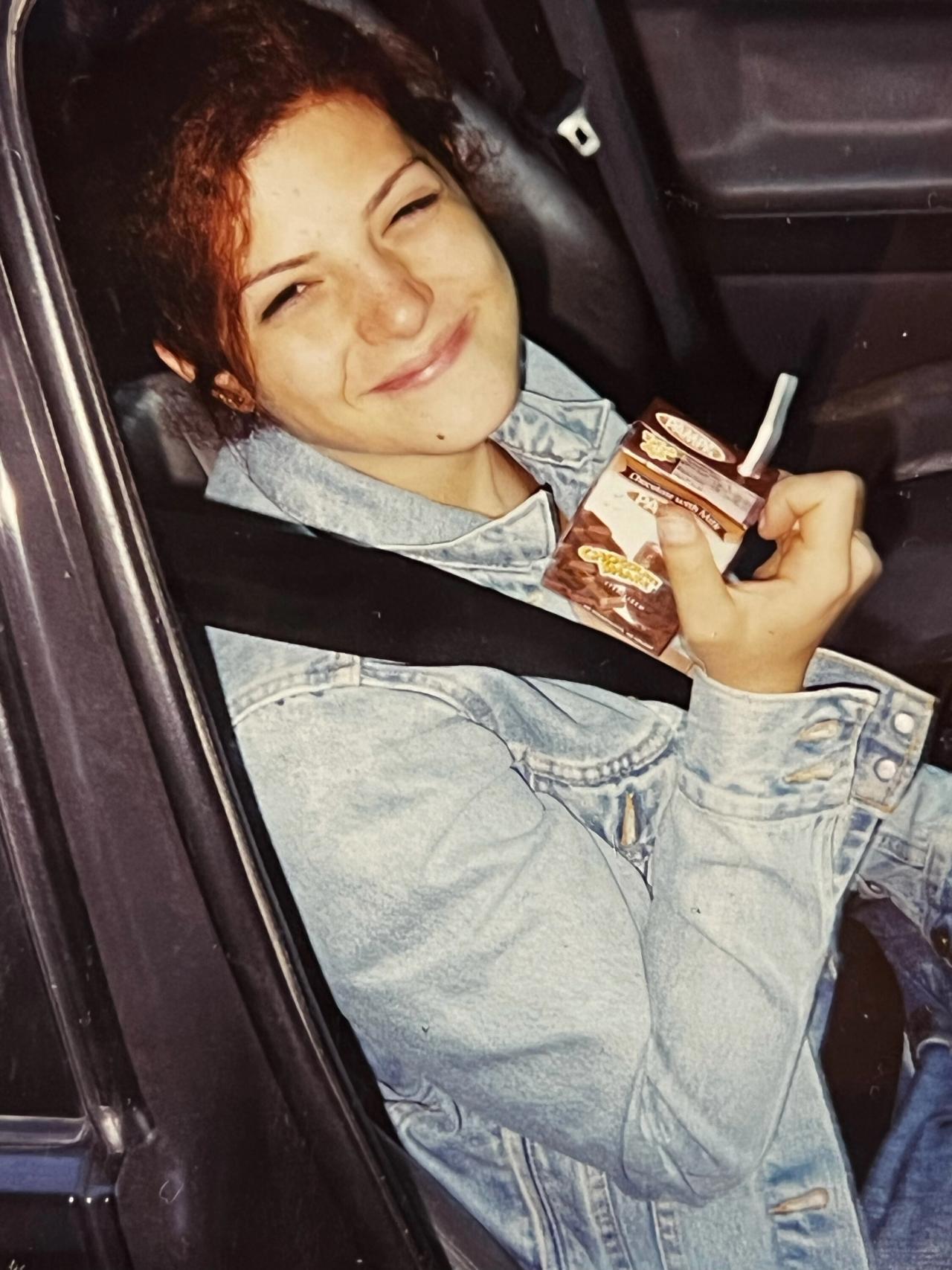

Semaan as a teenager upon returning to Beirut. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

So those are some of the earliest memories. Going to school in Montreal, I didn’t speak French very well, so I only spoke Arabic and I wanted to teach my peers Arabic. Apparently, my mom just shared this memory with me not too long ago. She was like, “You went to school and you danced [an Arabic dance] and talked to them in Arabic. That was your first day, and they made fun of you. They completely ridiculed you, including the teacher. You felt so hurt, and you came home, and you were so mad at the teacher.”

My mom was saying, “Well, don’t do that at school. Just don’t do that at school.” I was so mad at her! Like, “Why don’t you come in and defend me and tell them this is beautiful?” I carried this shame. I refused to speak Arabic from that point on. Nothing. Not one word of Arabic. Then, at age 13, we go back to Lebanon. There was the last cease-fire. My parents on a whim, within a month, they closed everything, packed everything, and my mom threw everything away.

We came back to Lebanon. It was a big cultural shock for me because I went from living in North America to living in the Global South in Lebanon post-war. No electricity. No water. That was okay. I had to speak Arabic, and I didn’t want to speak Arabic. I didn’t want to learn Arabic. I just had undealt issues that I’ve been experiencing and internalized so much racism about myself. I tried so hard to fit into this white world. Now I’m here, and I have this feeling that I’m better than everybody, because I come from a “civilized” land and you guys are “uncivilized.” So much internalized racism, internalized colonialism.

Semaan as a teenager upon returning to Beirut. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

My grandpa who passed away in 2019 was like, “What are you talking about? You’re civilized? We are civilized. We invented all of the numbers that you’re using. We invented the alphabet that they’re using. We invented all of this. We invented astronomy, mathematics.” All of this shift in my mind happened with my grandpa teaching me about colonialism, teaching me about the oppression that we’ve survived, and teaching me about the ancient wisdom that I carry. It has changed me forever.

I first hated my parents for bringing me back to Lebanon, and very soon after, thanking them for the perspective that I forever am grateful for—forever is leading me today. I’m literally building Slow Factory with the wisdom that my grandpa gave me and this idea that like, “What are you talking about? Who’s civilized? Is the military civilized?”

SB: Listening to this, I just couldn’t help but think that there’s this sort of survival mode you also had to put yourself in. First in Canada, and then upon your return to Lebanon. I’m wondering how being in that space, that mindset, has led you on your path and creative journey.

CS: Yeah. It’s actually a big topic in the book that I’m writing. It’s called A Woman Is a School. It will be published with Astra Publishing, and it’s coming up in April 2024. I believe it may come up sooner, but we’ll see.

Those are the things that I’m writing about in that book. It’s this journey that has led me to build this school, and the learnings that I’ve received from my ancestors and from my culture, from the women in my family, in my lineage. It’s a lot of vignettes and stories, a bit like the one I just shared. There’s also a chapter in it where a childhood friend of mine in Montreal comes with me to Lebanon. We’re in our early twenties. I haven’t reckoned completely yet with this idea of the Global North and the Global South. I’m still living it. I haven’t had my findings yet. I’m still deep in my research at the time. She comes with me, and she comes with so much entitlement and so much judgment over my culture, over my people.

Semaan at her high school graduation in Beirut. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

I share this in the book about seeing my country through her eyes and seeing the judgment that she is putting upon it—that we are uncivilized, we’re unruly, we’re savages, just the way we drive, and the way we can’t even stand in line to get bread. Because the culture of the Global South is a case-by-case culture. It’s not a standardized culture like in the Global North, where one rule is unanimous. You have to abide by the rule. In the Global South, we don’t have that you abide by the rule. It’s case-by-case, and you can totally break the rules.

I talk a lot about this notion of the case-by-case notion, which I think is key in understanding equity. Equity is not going to be a standardized rule that, “Oh, all people of all skin tones that are all da da da da da.” It’s not going to happen this way. Equity is a case-by-case rule. It must be something that is from the Eastern philosophies that has to be understood from a Global South perspective. It won’t be applied in the Global North perspective. You know what I mean?

SB: I’m so struck hearing you say all this, that you must have some internal wrangling between this North and South self. I was wondering how you view your work at Slow Factory within that, and how you see fashion within that, too? What roles do fashion, beauty, and aesthetics play in that internal navigation of North and South?

CS: These questions are definitely things that I ask myself constantly. The Slow Factory is trying to restore balance and create a counterbalance from the Global South as the Global South perspective, if you will. I keep saying that—“Global South perspective”—but one of the chapters in my book is called “Global South Baby.” It’s this energy that I’m talking about. It’s this perspective, this philosophy—the ease with contradiction. I have no problem with contradiction. I’m actually very at ease with contradiction. When you live in Beirut, you understand contradiction on a whole other level. I recently wrote an article for GQ Middle East, and it’s about the new masculinity in the Arab world. I talk about contradiction and the ease with contradiction. I mean, I feel like in the Global North, any type of contradiction is like, “I’m a hypocrite. I’m a hypocrite because A, B, C, D. I’m a hypocrite.”

Why do you need to be so hard on yourself? You don’t need to be a hypocrite. It’s, again, this carceral thinking that’s very Protestant. That’s very much ingrained in austerity. Austerity is not the solution at all, okay? It’s resulting from this colonial thinking. I don’t like that. [Laughs] I don’t embrace that at all. I’ve never did. I feel like in Lebanon, there’s this joyful defiance of that very colonial austerity. Whenever we can defy it, it’s like “hee hee hee hee,” a bit like school children, like [whispers] “fuck you!” kind of energy. [Laughs] But yeah, no way. That’s not the perspective, but you must be at ease with contradiction. There is no way around it. We are contradictory beings, period.

“You must be at ease with contradiction. There is no way around it. We are contradictory beings, period.”

There’s no purity. Purity is a colonial construct. We are made of these contradictions. Yes. I am, as a designer, super conflicted with how do I reconcile East and West? My whole life I felt like I was a diplomat trying to explain the East to the West and the West to the East. I was trying to make sense of it all in my mind because I’ve been uprooted from the East, going into the West. I tried so hard to fit into these constructs. Came back to the East at a time where I am rebelling. I’m a teenager. I’m confused. I’m rebelling against everything that has happened to me.

I remember my father telling me just as I am about to get married, and he’s like, “Oh my God, we took you from place to place, from place to place. You have never felt anchored anywhere. I’m so happy now that you are finding your home and feeling anchored.” I’m crying. I’m like, “I don’t even know what you’re talking about. I don’t know if I will ever feel anchored.” I’m embracing contradiction because that’s my life.

SB: Tell me about your return to the West, to New York and to this first dozen or so years of your career before starting Slow Factory. What was that transition back like?

CS: Yeah. In Lebanon, I had the opportunity to study art with a French teacher that was living in Lebanon. She had an apartment in Beirut and her name is Poppy Arnold. She was a French artist who lived in Beirut and taught a lot of children art. A friend of mine was studying under her and she told me, “Céline, you have such a gift in drawing.” I was born with this gift from my grandfather, I think, because he also has this gift, and my auntie. I always drew. I was always drawing. She said, “You have such a gift. You should come with me to this class, this art class.” Of course, I had to beg my parents because they were like, there’s no way I was going to learn art. “Why? Why would you need that?”

Semaan during her years attending art school in Paris. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

We begged them. We begged them, “Please, please, please, please. Give me one class, one Saturday a week.” Through this one Saturday a week, I learned how to draw, I learned how to paint, sculpt, everything. I became very close to my teacher. Obviously she was such a role model for me. She taught me so much about slowness, actually, and about pointing out that in Lebanon we have this urgency because we’ve lived a war and children are always forced to be, “Yalla, yalla, yalla.” “Hurry up, hurry up.” Everything must be fast, fast, fast. We lost this slowness in our culture and she was teaching us to slow down. All these techniques that we were learning were so ancient, like oil painting. You have to do it so slowly. There’s no way it’s going to dry faster even if you use a hair dryer. [Laughs] So this whole idea of slowness.

Poppy Arnold, the teacher, said to me, “You should pursue art. You should pursue design and art. You should do this as a career. You should go to Paris.” So of course I go back home, and I’m telling my father and mother, “I’m going to go to Paris. I’m going to study art. I’m going to be an artist.” Of course, they’re like, “Are you kidding me? There’s no way we survived all this for you to go blow it away in drugs and alcohol, and becoming an artist and being a useless person on this planet. There’s no way you’re going to be useless.” And I said, “No, but it’s not useless. It’s useful. It’s useful to be an artist.” “No, there’s no way you’re being an artist.”

Of course, I had to convince them. Poppy Arnold had to come and talk to them: “Give her one year. Give her one year. Give her one year in Paris. Help her. Help her be there for one year.” My dad said, “You have one year. And if you fail after this one year, you’re done. You’re going to go back and be useful—to society, to the world. You have so many skills. You have to be useful. You cannot be useless.” For them, an artist is useless. It’s arguable. [Laughs]. But I was like, “Okay, one year. One year.” After this one year, my design school failed me. They were like, “You’re not a designer. You’re an artist. You can’t be a designer.” Because I had been doing applied arts. I chose applied arts to be as useful as I can with the skills that I have.

Semaan during her years attending art school in Paris. (Courtesy Céline Semaan)

I failed. My dad came to Paris and he picked me up, and he said, “You have two choices. You go back to Beirut, or you go to Montreal and you have a proper education.” I said, “But I want to stay here. I want to be an artist.” He said, “No, you have two choices. You can’t stay here.” So I left for Montreal and I kept in close touch with a new teacher that I met in Paris. His name is Patrick André. And his artist name is “Patrick André depuis 1966,” which means Patrick Andre since 1966, which was his art practice. He was our conceptual teacher. I kept in touch with him for seven years. I continued to build my practice through our correspondence as I was in Montreal.

But the first thing that I noticed when I left the East to the West, through this whole experience of trying to be a designer, was realizing that I came with radical generosity. That was part of my culture, radical generosity. For example, I’ll feed you. I’ll help you. I’m not expecting anything out of it because I know that, through my culture, we both share this radical generosity. We’re going to compete on generosity. But in the West, there’s no such thing. The first thing that I had to learn, that I didn’t know before, was that I’m going to be taken advantage of every time that I practice radical generosity. It will never be reciprocated. Until this day, I’ve struggled with this, because it’s true that it’s not part of the West’s culture to reciprocate any form of generosity. It’s not going to be reciprocated. That’s the first thing that I had to reckon with.

I had two choices. One is I become austere just like them or I continue being radically generous, but I find ways to protect myself from disappointments. Those are the things that I reckon with being from the East and living in the West. I feel like a lot of these conversations I was able to find peace with my Indigenous peers because the idea of radical generosity is a concept in Indigenous culture. There’s a book called The Gift that’s very beautiful that talks a lot about that and about the exploitation that was just normalized in the Global North about just how it’s just part of.… Yeah, it’s part of the entitlement that I don’t understand.

SB: Let’s end on the subject of colonialism. So much of your work is about an anticolonial education as a means toward narrative change and highlighting various cultural erasures. Just showing how colonialism has wrapped its serpent tail around so many areas, and succeeded and expanded in all these ways. I use the word succeed there in the sense that it is omnipresent. Now that you’ve had Slow Factory for a decade plus, what are your views in terms of decolonization reaching the mainstream, whether that’s celebrities, politicians, corporations? This year, it was at least mentioned in the 2022 I.P.C.C. report. So some in the Global North are finally starting to see colonialism as the root cause or problem that it is.

“Decolonization is essentially land back. There is no other way around decolonization.”

CS: Yeah. There’s a great piece of information that we share at the Slow Factory. It’s a white paper by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang called “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” It talks about the fact that decolonization is essentially land back. There is no other way around decolonization. Of course, we need to decolonize certain thought processes, education, and so on, but it cannot be used as a metaphor and a pacifying way to just keep things as they are. We’ve seen that there has been a co-opting of this term decolonization. Now, there’s “decolonize your makeup routine,” “decolonize your hair,” “decolonize your dance moves,” and all of these things. “What are you talking about?” Decolonization is about land back. That’s the foundational knowledge piece that needs to be retained from this.

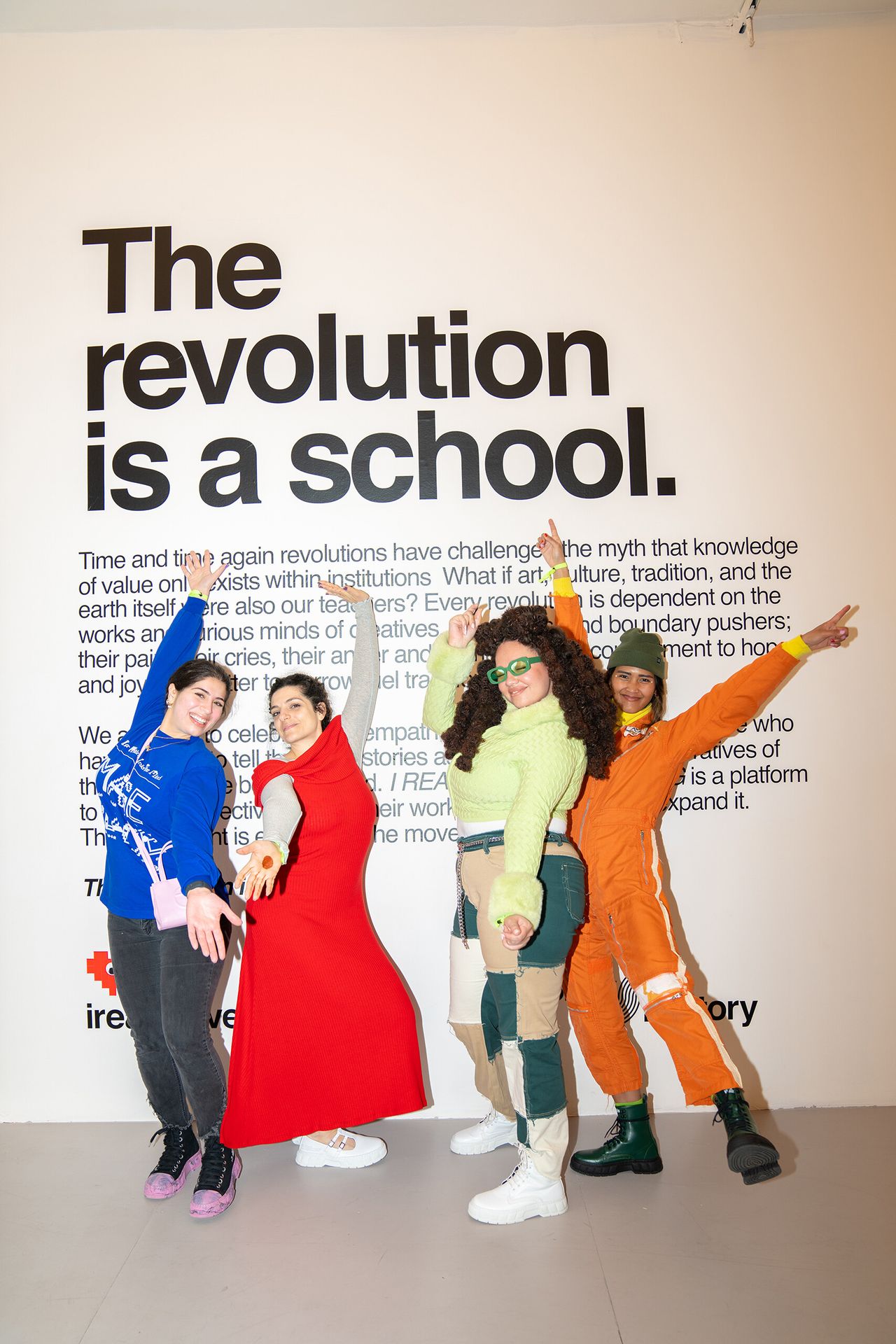

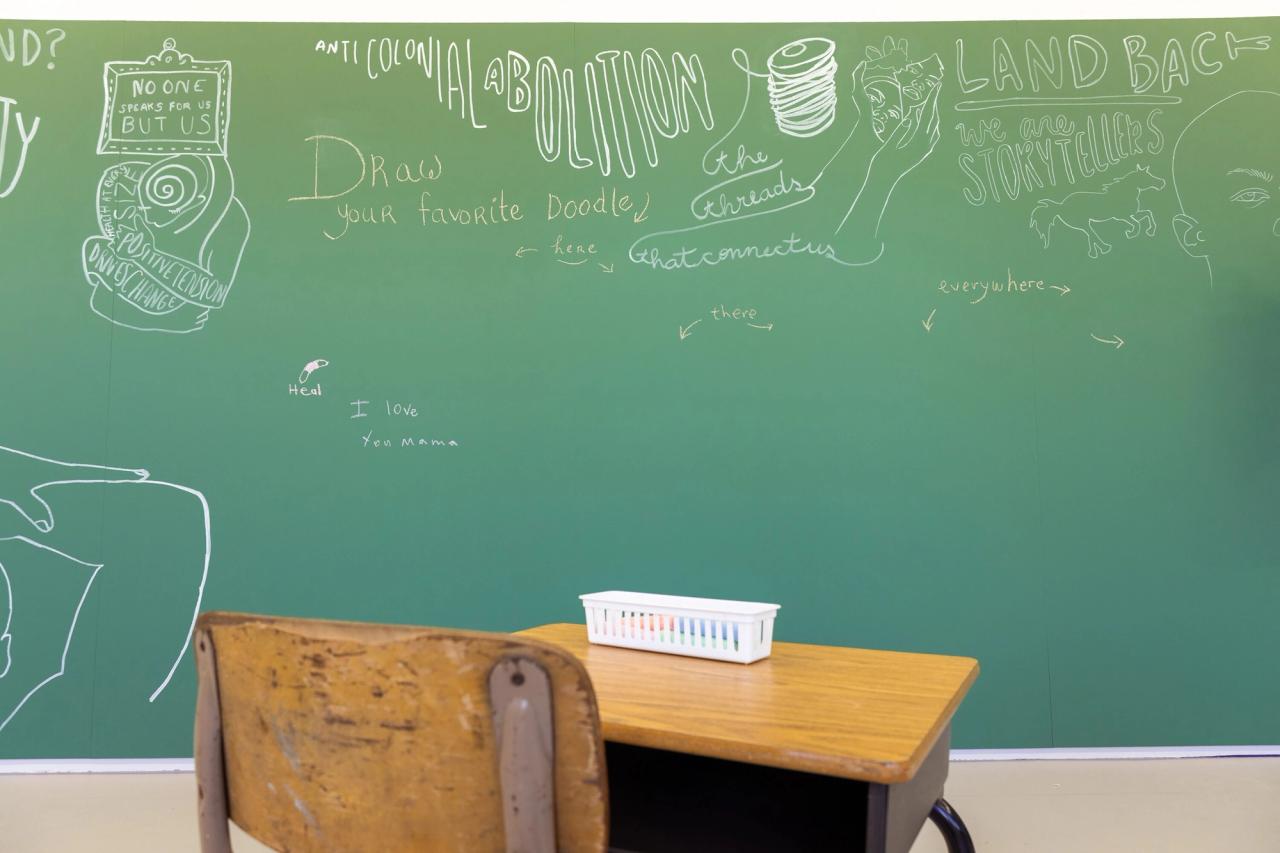

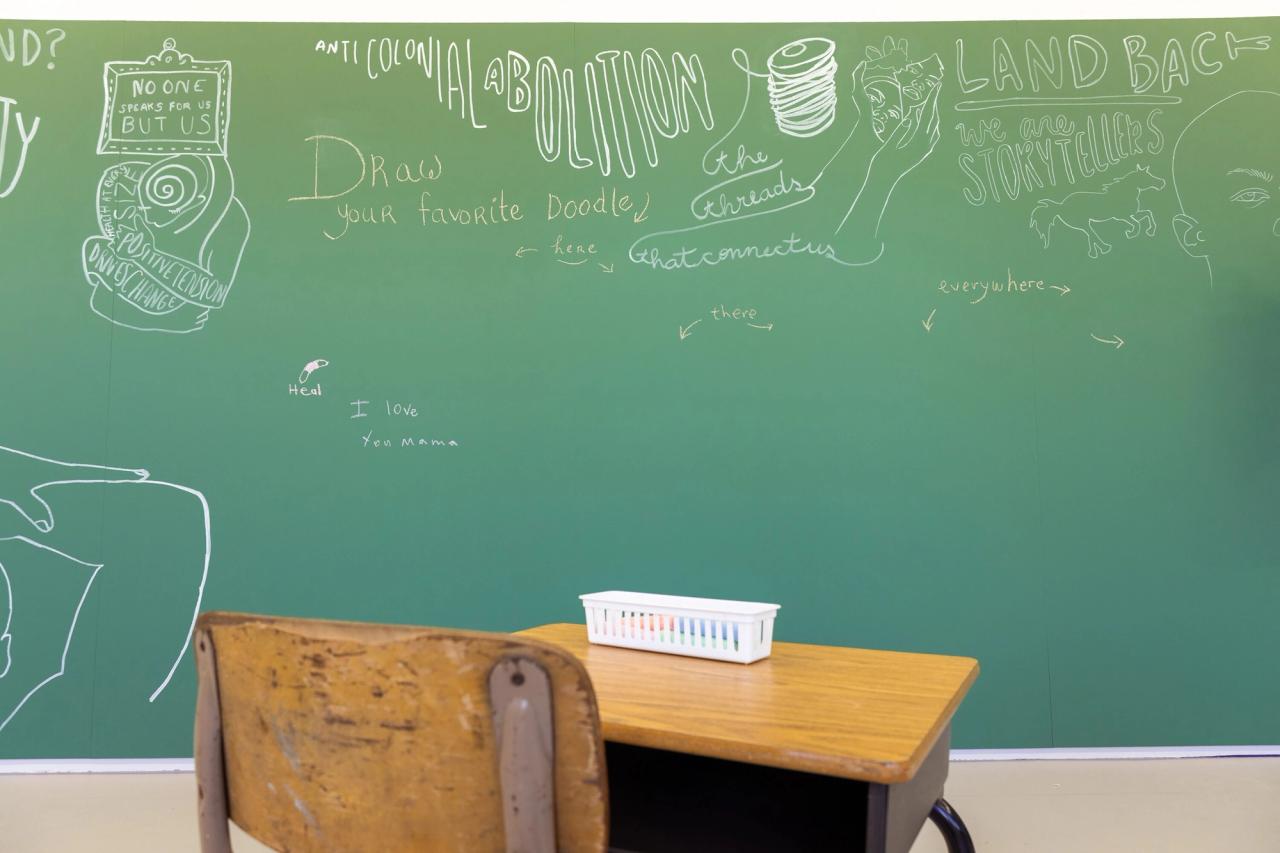

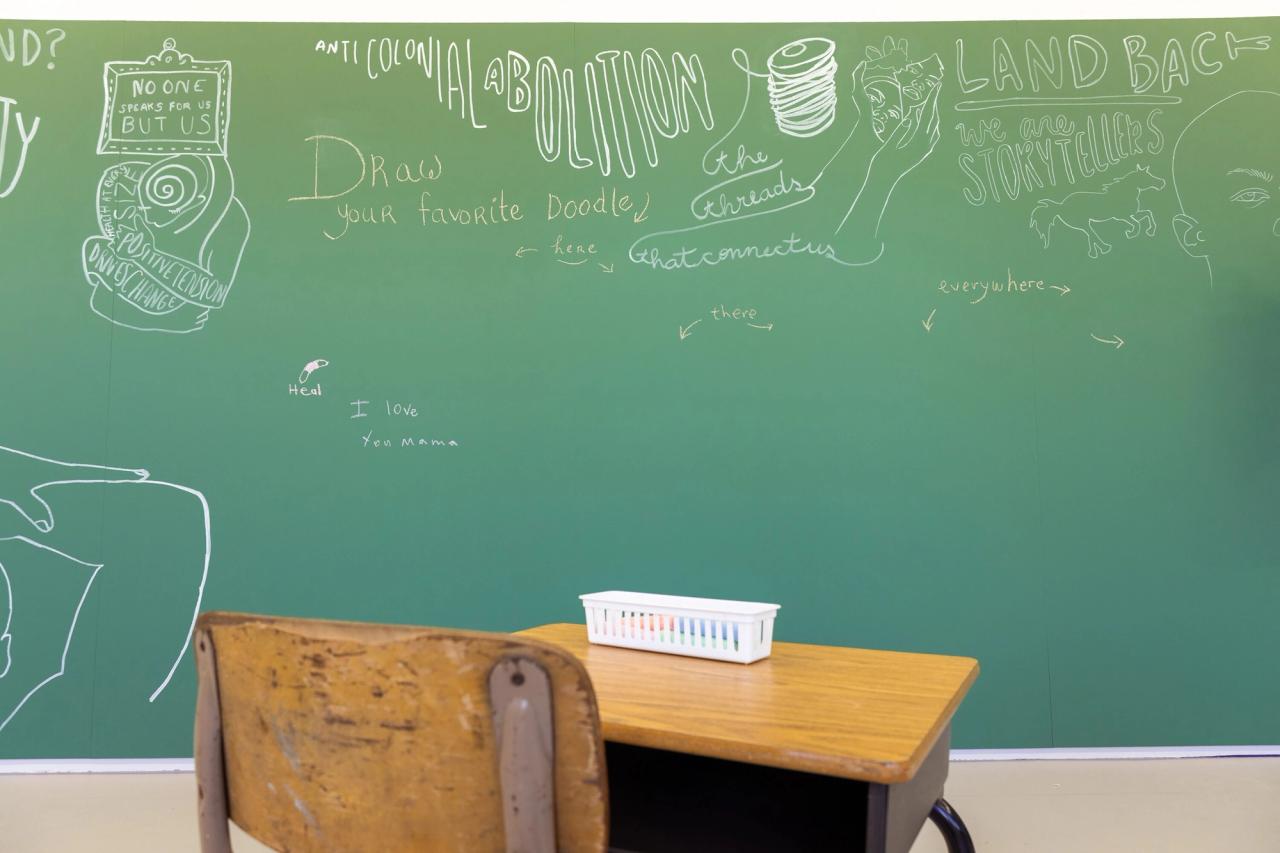

Semaan and other Slow Factory members at the opening of Slow Factory’s presentation “The Revolution Is a School” at MoMA PS1. (Courtesy Slow Factory)