Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

(Courtesy Kate Young)

Kate Young: Did you ever see that SNL skit about the champagne Moët Chandon [pronounced “moe-et shan-don,” in an unapologetically trashy American accent]? It’s like my motto in my office. It’s these two girls trying to do a promo video for Moët Chandon champagne, but they’re porn stars. They are really drunk and keep going, “Luxury! Opulence!” [Laughs]

Andrew Zuckerman: [Laughs]

KY: And it’s what we do in the office, non-stop.

AZ: That’s how you respond to things?

KY: [Laughs] Yeah.

AZ: So, Kate, welcome to Time Sensitive. We’ll start there, actually.

KY: [Laughs]

AZ: Luxury and opulence. How do you feel about the pace of fashion right now?

“Designers have to produce four to eight, maybe ten, collections a year. And I just don’t think any creative person can do that—can create something new, of value and quality, every month. It’s too much work. There’s not the downtime to process.”

KY: I think it’s unsustainable. That’s the bottom line.

AZ: And what’s making it so unsustainable?

KY: Well, it’s too fast in high-end fashion. The designers have to produce four to eight, maybe ten, collections a year. And I just don’t think any creative person can do that—can create something new, of value and quality, every month. It’s too much work. There’s not the downtime to process. I think, because there are so many collections that are being produced, because the images are so consumable on Instagram, by the time the product’s available, you’re tired of it. There’s a disconnect right now, and nobody knows how to solve it. They tried the see it, buy it, wear it now model, and it didn’t really work. Nobody has figured that out yet.

AZ: Which they called “fast fashion,” or …?

KY: Well, fast fashion is cheaper clothes. Fast fashion is Zara and H&M and …

AZ: Well, what is that about? What is it?

KY: It means it’s trendy, it’s quickly produced, it’s quickly available. I think, by “fast,” they mean you can just buy it without thinking about it, too. That word has a lot of meanings in that context. It’s environmentally unsustainable. I think people are starting to realize that consuming so much clothing—specifically throw-away clothing—is really bad for the environment.

Hermès leatherwork. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Making an Hermès bag. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Hermès leatherwork. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Hermès leatherwork. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Making an Hermès bag. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Hermès leatherwork. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Hermès leatherwork. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Making an Hermès bag. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

Hermès leatherwork. (Photo: Alfredo Piola)

AZ: Is there still a “Slow Fashion” movement that’s alive?

“Hermès bags are expensive because they are put together by hand, by people—the person’s signature is in the bag. It’s not just because the Kardashians carry it.”

KY: Yeah, I think there is a sort of hipster Slow Fashion movement that’s about artisanal goods and plant-died, handwoven fabrics, that kind of a thing. But I think that there is, in the American psyche, a missing link where “luxury fashion” does not mean quality and slowness. In fact, what the price of luxury reflects most of the time is artisanal work. Like, Hermès bags are expensive because they are put together by hand, by people—the person’s signature is in the bag. It’s not just because the Kardashians carry it. It’s not an arbitrary number that they charge.

AZ: And is that becoming unsustainable?

KY: I don’t think so. That kind of fashion really sells. Even in a recession that sells like crazy because rich people never lose their money.

AZ: People talk about the definitions of art and fashion, which are really hard to define. What is your definition of fashion?

KY: Oh god, I have a problem with the conflating of art and fashion. It doesn’t really work for me.

AZ: No, I mean more that art is very hard to define, and fashion is very hard to define.

KY: Yeah, fashion is very hard to define. On a really fundamental level, it’s clothing. I think, for me, the reason celebrity styling worked instead of editorial styling is that I like clothes that work. I’m not that into it when clothes are extreme, or when it doesn’t work in a real context. I can be inspired by it, but what really gets me is something that makes someone seem cooler or more interesting, more beautiful, more glamorous. I like it when it actually works.

AZ: When it functions, like in design. That’s kind of the difference between design and art.

KY: Yeah, exactly.

AZ: Beyond clothing, you have this deep knowledge of objects.

KY: [Laughs]

AZ: In various ways, you certainly have a reverence for jewelry. What generally sparks your interest in these objects? What makes them endure in your life? What makes them stick around?

“There is something really satisfying about something that is perfectly balanced aesthetically.”

KY: I have a real weakness for beauty. It doesn’t always work out for me. It’s a little crazy. And what makes things stick around? Good design, I think. How do you describe it? I don’t know, but there is something really satisfying about something that is perfectly balanced aesthetically. I think those things just work, and they tend to keep working. There’s a calm feeling, for me, when I look at something. It’s like that egg Instagram post. I feel like it was so popular because it’s the perfect design. We all look at that and are satisfied by it.

AZ: With objects, there’s also the value of touch. Can you talk to me a little bit about how objects are not just visual, but there is some sort of sense—

The first Instagram post on the @world_record_egg account, which has received 53.3 million likes to date.

KY: Well, clothes—so much with clothes is how things feel. I think that is a weird missing link, actually, with online shopping, that you can’t touch things. And I buy all of my clothes online now, basically. But when I’m working with clients, I do all of my appointments in person, because I need to touch the clothes. I can’t usually tell you if I really like something until I touch it.

AZ: That makes a lot of sense.

KY: It does, but I can’t explain why that is. It’s hard to articulate.

AZ: Well, these are non-verbal senses. That’s why, I guess. But also, objects allow us to travel through time in a really interesting way. Things that you get attached to, you get attached to for a certain reason. And I think they have to do with time, probably. Do objects represent moments, relationships, things that—

KY: For sure. I keep clothes that I wore at certain times. I have a pair of pants that I bought on my first trip to Paris without my family. I have the T-shirt I wore the first time Keith and I made out. [Editor’s note: She’s referring to her husband, Keith Abrahamsson, co-founder of record label Mexican Summer.]

AZ: What is it about that? Why can’t you let them go?

“The way my mind works, I remember what I was wearing, rather than what happened a lot of the time.”

KY: Because, the way my mind works, I remember what I was wearing, rather than what happened a lot of the time.

AZ: Clothes help you travel back to that moment.

KY: Yeah, I like just seeing it. You know, when we move, or when I re-organize and I see those things, they make me happy.

AZ: Do you feel weird about objects that someone else lived with for a while? Like a vintage watch that someone else wore?

KY: Oh yeah, I always sage them and put the—I’m so hokey. The full moon shines on them, and I do all that stuff. I put jewelry in salt a lot of the time.

AZ: Why?

KY: Somebody told me to do that.

AZ: Because metal has memory somehow?

KY: Yeah, well, I think that’s part of the beauty of jewelry, too. When you wear something right on your body, that’s why peoples’ grandmother’s rings mean so much to them, or, like, some necklace. When my son has performances at school, I always give him a piece of my jewelry to wear or to hold because I feel like it’s got your stuff in it.

AZ: Mm-hmm.

KY: Don’t you think?

AZ: Absolutely. One hundred percent.

What are some of the pieces in your—I know you collect a lot of Cartier, a lot of various jewelry pieces. And it’s really extensive. What are some of the pieces that you love and why?

KY: Oh, I just got my favorite thing ever.

AZ: I want to hear all about it.

KY: I’ve been looking for it for so long, this nineties Cartier bracelet from the Nouvelle Vague collection. And it looks like the cheapest—you know the ball-bearing chains, like a bicycle chain, or something you would wear your keys on if you were a messenger? It looks like that. There’s a diamond in every single ball. And it’s platinum. It looks so simple, and so cheap. You know, it was the nineties, it was sort of grunge. But it’s actually super-fancy, and it’s really beautifully made and constructed.

I started working as an assistant at Vogue in the nineties, and when I was Tonne Goodman’s assistant, she loved that piece. She loved that collection. We had it on every shoot the first year I worked there. It was so much money, and I wasn’t making any money. Sofia Coppola had it—we’re friends—and she still has it, wears it sometimes. Over the years, I’ve just been like, “Ugh, that bracelet!” And this woman Ola [Itani-Chan], who was the head shopper at Prada—who had the chicest style—she also had it. These two women who represented great taste both had it, and I kept seeing it at work. So then, I finally made some money, went to Cartier, and was like, “I want to buy this bracelet.” But they were like, “We made about six of those bracelets, nobody bought that bracelet, it was too expensive, it didn’t look expensive, and we sold very few of them and haven’t sold them in twenty years.” So I’ve been looking for one.

A Cartier Tank watch on Young’s wrist.

AZ: And you’ve found one.

KY: And I’ve found one. I mean, I work with Cartier a lot—I’m friends with the archivists. And I was like, “Listen, do you have any of these bracelets, have you seen them? You guys go to auctions all the time, if you see one, will you just call me?” And so, I finally found one.

Top to bottom, from Young’s Instagram account (@kateyoung): closeups of Gucci, Prada, and Chanel couture looks.

AZ: Amazing. I wonder if it speaks to your sort of high-low thing? You love that contrast of high and low.

KY: Well, I don’t like anything flashy. Like, I love a disco ball evening gown, but I can’t wear anything flashy. I’m horrified by it. I’m made so uncomfortable by that idea. But at the same time, I really love luxury goods, I love diamonds, I love jewelry. I’m always interested in anything that is kind of inward-facing.

AZ: But you drink deli coffee, you don’t care about the small things.

KY: No, I love deli coffee.

AZ: When I was thinking about that before you came in, I was thinking that you think about dressing narratively. You think about it from a story perspective. Have you found that your interest beyond the body is about extending the narrative into an environment or dressing space in a way?

KY: They go together. I’m really interested in design and objects and beauty and color and form. And that is fashion. But that’s also jewelry. And that’s also furniture. And art. And sculpture. And ceramics. And flowers.

I’m really interested in any physically beautiful thing. They all go together. Part of it is my job. But it’s all informed by each other. I think I have a weird color sense for a stylist. It’s one of the things that I do—I like strange and surprising color. I use color in a way that isn’t traditional, and I think that comes from art and furniture. I’m not that inspired by watching fashion shows. That’s too easy.

AZ: Yeah, so do I.

KY: [Laughs]

AZ: You also have this interest in objects beyond the body, beyond clothing, beyond jewelry.

KY: Mm-hmm.

AZ: Yeah, you draw inspiration from the Russel Wright House more than the runway.

KY: Yeah. I feel like any fashion student can do that. You have to take what you see and have a different perspective on it. The only way to do that is to have a more developed, wider aesthetic sense.

AZ: We were talking a bit about luxury. I’m sure your personal definition and understanding of it has changed over time. What is luxury to you now?

KY: Ugh, I don’t know. “Luxury” is now a very weird word. It’s a word, to me, that’s tainted. You know how certain words become yucky?

AZ: Well, beauty was for a long time, and now it’s finally coming back.

KY: Oh, interesting!

AZ: Beauty was considered a bad word by many in the twentieth century. A critique of an artist would be, “Well, it’s beautiful, but what is it saying?” Now, I think, maybe because there is so much ugliness in the world, beauty is coming back. But luxury is taking the place of the negative connotation.

“‘Luxury’ is a very weird word. It’s a word, to me, that’s tainted.”

KY: Yeah, I think that, weirdly, reality TV and Instagram have put wealth in our face, and consumption in our face, in a way that—different people have different reactions to it. Some people are jealous because they want those things; some people just want to be more like that; some people are repulsed by it and disgusted by it. But I think that luxury used to be this—in my mind, it was these very wealthy people who had so much money, who didn’t have to work, and what they did was collect and find beautiful things. Like, people who collected Aprey salt shakers and little figurines with ruby eyes. Now I think of it more like these videos of these walk-in closets with thirty-five Birkin bags. That is kind of yucky to me. I don’t know why.

My former idea of luxury was this eccentric idea, and now it’s more a mass-consumption idea. Well, and I think it’s actually skewed, it’s not true. I’ve heard this story that Jackie Kennedy walked into the Chanel store in Paris and bought the entire store when she was with [Aristotle] Onassis. And that’s repulsive. But my idea of her is that she was super-refined and selective …

AZ: But she actually curated nothing.

KY: Yeah, so I think that maybe it’s all the same.

AZ: Maybe it has to do with time and not objects themselves. Does luxury now, for you personally, have to do with experience more than object?

KY: Oh, my personal luxury? The most luxurious thing in the world to me is to not work, and to be with my family, and not have homework, or emails, or obligations that are work-related. It’s hanging out, and having time, and cooking dinner, and being together, and having the sun shine. Stuff that you can’t control.

AZ: Being out in nature. Does nature have something to do with it?

KY: Definitely.

AZ: How does nature play into your life? Your family lives in an urban environment [New York City].

An Oscar de la Renta look from Young’s Instagram.

A Chanel couture look also from Young's Instagram.

Another Chanel look from her Instagram.

An Oscar de la Renta look from Young’s Instagram.

A Chanel couture look also from Young's Instagram.

Another Chanel look from her Instagram.

An Oscar de la Renta look from Young’s Instagram.

A Chanel couture look also from Young's Instagram.

Another Chanel look from her Instagram.

“I don’t know that I could work the way I do, and travel the way that I do, if I wasn’t in nature when I have time off.”

KY: Well, but in the summer we live upstate, and most weekends we live upstate. That’s luxury, the fact that I can split my life that way. But it’s become a bit of a necessity. I don’t know that I could work the way I do, and travel the way that I do, if I wasn’t in nature when I have time off.

AZ: Are you inspired by nature?

KY: Yeah, for sure, it just feels like a reset.

AZ: I couldn’t live without it, I don’t think. And I think that the older I get, the less interested I am in objects, in a way.

KY: Interesting. See, when I’m upstate, by the end of summer, I’m shopping. The FedEx man is coming to our house every day. Because I need—I’ve had enough of Birkenstocks. By that point, I want some pretty shoes, I want some fancy stuff.

AZ: Yeah, you need the contrast. I couldn’t live upstate all of the time.

KY: I need to go to a museum, I need to have a cocktail in a place where everyone has on nice clothes. [Laughs] Keith doesn’t. Keith is just like, “Ugh, I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

AZ: Keith, your husband.

KY: Mm-hmm.

AZ: Before we get to your current thing, actually, I want to go all the way back to your early life. Where did you grow up?

KY: New Hope, Pennsylvania. Like right there [points out the studio’s north-facing window on 26th Street, toward the Hudson River and New Jersey]. Right out your window, across the river.

AZ: What was your childhood like?

KY: I grew up in a farmhouse. My parents were professors. I was pretty bored. We didn’t live in a neighborhood. It was just land. And my parents didn’t work in the summers, which was great because we would travel. I have a younger brother. He’s really fun and weird. I don’t know, I would say the overarching theme [of my childhood] is boredom in nature.

AZ: Right, which gave you a lot of time to think.

KY: [Laughs] Yeah.

AZ: Were you interested in fashion when you were a kid?

KY: Always.

AZ: How did that start?

KY: My mom used to take us to the library, and I just wanted to read Vogue.

AZ: It was just immediately magnetized?

KY: Mm-hmm.

AZ: And what did they, this intellectual family, think of that?

KY: I think they indulged it. I mean, they definitely indulged it. They would check out books for me, we would go see any fashion exhibition. My mom—we would come into the city and go to a museum, and then go to lunch, and then we would go to Bergdorf’s. Because that’s what I wanted to do—go to Bergdorf’s. I wanted to go look at the people shopping there, and the people working there. And I wanted to try on clothes. I mean, even when I was tiny, that was really it for me.

AZ: That’s so the antithesis of the craft movement of New Hope, Pennsylvania, which is not chic at all. You said something to me once that I thought was really funny: You’re not really a fan of George Nakashima’s furniture.

Inside the Conoid Studio on the grounds of George Nakashima Woodworkers in New Hope, Pennsylvania. (Courtesy George Nakashima Woodworkers)

KY: Well, where I grew up, everybody had it. [Laughs]

AZ: Right, so to you it represents …

The apartment from the film 9½ Weeks. (Courtesy MGM)

KY: I grew up seeing that stuff in everyone’s house—everybody’s messy house. Everybody in the town I grew up in was a professor, and you know professors’ houses. Now I actually have a soft spot for them. But it’s what I wanted to—I wanted to live in a Zen Japanese minimalist house. I wanted to live in the 9½ Weeks apartment. And everybody had oriental rugs with holes in them, furniture upholstered in velvet with holes in it, and cat hair in it, and piles and piles and piles of books everywhere, and art from flea markets. And macrame because, you know, it’s the seventies and eighties. New Hope was just this brown, cozy vibe, and there was a lot of Nakashima around.

The catalogue of a 2013 Christie’s auction of items from the New York City loft of Anita Calero, who had a collection of Nakashima furniture and is Young’s former neighbor and good friend.

AZ: It must be funny for you to see Nakashima all over the place now.

KY: Anita Calero, who we were just talking about [before recording this episode], lived down the street from me [in New York]. The first time I went to her loft, I was like, “Oh yeah, of course you have all this Nakashima stuff …”

AZ: For the listeners, who is Anita Calero? I don’t think a lot of the people know who she is.

KY: Anita is an old friend of mine. She’s a still-life photographer, and she and—is her name Maria? The woman who was her partner [Maria Robledo] basically invented the look of Martha Stewart Living—that minimalized, fetishized, everyday object. That color sense, that restrained beauty in homemaking, that Zen thing Martha presented that was so new—that was them. Anita had this loft with a massive collection of Charlotte Perriand, [Jean] Prouvé, and Nakashima pieces. I went to her house the first time and was like, “Oh!” Because I didn’t know—well, I knew about Prouvé, but I didn’t know about Charlotte Perriand back then. And I had never seen Nakashima out of an environment that was so homey. It was like a revelation.

AZ: It’s interesting how context can frame objects. And also, in these early days, before we’re educated on these things, how we still respond to them in some way. We have a response system, the aggregate of which is our vision or our taste. Those early experiences are really important because you learn what you like.

KY: Well, now, I like a lot of that stuff. The idea of that homey house is very charming to me. I wouldn’t mind living in one for a little while.

Young as a child.

AZ: Maybe because we respond to something when we’re young. And then we come back to it when we’re adults.

KY: Yeah, I don’t want to live in the 9½ Weeks apartment any more. But at the time … [Laughs]

AZ: Yeah, it was pretty chic. You also come from a family of athletes?

KY: Yeah. Well, they’re professors of exercise physiology. [Laughs]

AZ: Tell me all about that. They’ve been involved in the Olympics, I’ve heard.

KY: [Laughs] The sporty side. Well, my brother moved to the Olympic Training Center [in Colorado Springs, Colorado] when was, I don’t know, maybe thirteen. He was a world champion cyclist, and my dad was one of the coaches of the U.S. Olympic [cycling] team. Everybody else—my mom went to the Olympics for ping-pong. [Laughs] She was a pro tennis player, and then she was the director of athletics at Lafayette College [in Easton, Pennsylvania], where she was also the tennis coach. My cousin went to Korea for volleyball. My two uncles—one played professional basketball, the other one professional soccer. Everybody’s run a marathon …

AZ: You’ve dealt with the body in a different way. Were you interested in sports like them?

Young, with a tennis racket, from her early years.

KY: There was no option in my family. You had to play sports. I had to play a sport at all times. I played tennis, I ran cross country. I played field hockey for a little while, but I wasn’t very good at that. And then … my college application essay was “I Hate Sports.” It was about why I hated sports. Because I had grown up going to bike races. It wasn’t until I was fifteen that I was allowed to not go to the bike races. My brother was the prodigy bike racer, so every Saturday and Sunday we had to wake up at, like, four in the morning and drive to some random place in New Jersey to watch him win another race. And if he didn’t win, he’d vomit all over the place and have fits the whole way home. [Laughs]

We’re competitive by nature. I wanted out of it. But then I got to be—I don’t know. I mean, I guess I didn’t really exercise. I wasn’t really into sports at all until I got to be maybe thirty. I ran the New York City Marathon, I started playing tennis competitively again. Now I’m super into pilates. I decided yesterday that I’m going to get certified and become a pilates instructor, because then I can do that when I retire. [Laughs]

AZ: You should really do that now, because you have nothing going on [said in a sarcastic tone].

KY: No, but I like it. I like to learn. I like to understand the whole thing—if I’m really into something.

AZ: It’s about rigor. What [your parents] taught you was rigor.

KY: Yeah.

Young on a ski mountain in her teens.

AZ: Which could have been applied to anything.

KY: Exactly.

AZ: And then you went on to study English and art history [at University of Oxford]. Tell me a little bit about that.

KY: Well, in that [Hollywood Reporter] video that we talked about, they asked me about my education. I said, “My parents laughed when I told them you could do a fashion degree.” And that’s something that I think is a weird feature—that I didn’t know that you could study fashion. And even when I heard it, my family dismissed it so wholeheartedly. I’m glad in retrospect, but my dad’s advice was to always do what comes easy to you. And to figure out a way to make your job what you do anyway. English and art history, it’s still what I do. If I have time off, I read a book or I go to an art gallery. And it was easy. So that’s why I chose that.

AZ: I’m interested in how it informed what you actually do for your job now.

KY: Things are a little different now, because fashion is so available on the phone. But art history was very practical because it teaches you to write and speak in such a descriptive way. When I first started, it wasn’t “Givenchy Look No. 2.” You had to wait for a month for the lookbook, so when you requested a look, you had to call and say, “I’m looking at the slides, Audrey Marnay is the model, and the dress is a short silver, possibly silk, with knife pleats.” We had to request by description, and I think art history teaches you that. So much of art history writing is just in-depth description and observation.

Young in Oxford, England, during college.

AZ: Yeah, it taught you how to look. I’m also wondering if the English major taught you how to think about story. The work you make is so much informed by story.

KY: I read novels. That’s what I do with all of my time: read novels. I was trying to figure out why I do that. I actually think what it does is make me empathic. I think it is a lot of what I do, is try and figure out what it would feel like to be my client, in their body, doing what they’re doing, and then what I would wear. Reading novels makes me feel what people who aren’t me feel.

AZ: That gets into this idea of how you deal in that moment. Think about awards season. You just finished it, and that’s high-stress. You have some of the best clients in the world, at the height of their careers. How do you navigate that space, doing your work, holding their hand, making it work as an incredibly intimate collaboration?

KY: You know, it’s different with every client. Because some people thrive on it and are not that stressed. Some people enjoy it. They’re psyched to be nominated, they’re psyched to be going to this, they like the attention, they’re excited about the dresses. And some people just about lose it every single time they have to walk out of the room to go to an award show. They’re nervous, they’re uncomfortable, they don’t like doing this, they don’t want to be seen. It varies.

AZ: But all are navigated with this empathic approach.

KY: I’m in service, right? My service is that I make it so that they don’t have to think about their clothes. All they have to do is think about themselves, and how they’re going to feel confident and good. For some of them, I like to provide a sort of alter ego, through the clothes, that they can act. When they’re really nervous, sometimes it’s better if they can act like a movie star going to something.

AZ: That makes a lot of sense.

KY: That’s what they’re good at. If that’s what they need, maybe we can cook up a person that they’re playing. Or I try to—even the most perfect physical specimen is nervous and uncomfortable with something about themselves. I try to hide their flaws and highlight the things they’re comfortable with, and give them a part to play if they need it, and make them feel taken care of.

It’s weird, [my relationship with my clients has] changed a little bit. I feel like I used to be the cool friend, and I’m now turning into the mom. [Laughs] Not to all of them, some of them. If I’m younger than they are, I’m still the cool friend. But now I have these younger clients, and now I’m like, “God, I’m turning into the mom.”

AZ: Well, you have this experience that you can apply. Because it’s so intimate.

“When you get naked with someone, you have to trust them.”

KY: Yeah, they get naked with me. That’s something. When you get naked with someone, you have to trust them.

AZ: You didn’t start in celebrity styling, right?

KY: No, I started at Vogue.

AZ: Was that your first job?

KY: I had a job for six months at a fashion [public relations] company before.

AZ: And then?

KY: Then I went to Vogue.

AZ: What did you do there?

KY: I was Anna’s assistant. The second assistant.

AZ:Anna Wintour.

KY: Mm-hmm. I did that for a year—eleven months—and then I was a market editor for three years.

AZ: What did you learn from working with Anna Wintour? What did you take away? Or what do you think about and remember from that time?

KY: First of all, she was beautiful. I feel like, now, she’s such an icon, and [her look is] like a costume. But she was shockingly attractive in person back then. The next thing is that I felt she worked on a different plane of time, which applies to this podcast really nicely.

AZ: Tell me about that.

KY: She just got more done. Things happened like this [sound of fingers snapping] all day long. She had two young kids at the time—she’d drop one of her kids off and be at work so early. Five to eight—she’d be there. She left every day at five fifteen, because she was going to be at home with her kids. But it was like meeting, meeting, meeting, meeting. There was no playing music and staring at the screen or chatting on the phone to a random friend about this and that. There was not one wasted second when she was there. She just seemed to me to get more stuff done in one day than most people did in two weeks.

AZ: Focus.

KY: Just utter focus, yeah.

AZ: Well, time for everyone is different. Generally, the markers we make for time depend on how we choose to do it. She created these markers that she had to hit all day long. You don’t work that way, right?

KY: I actually do. That’s exactly how I work now. I try not to mess around.

AZ: You’re hyper-scheduled?

KY: Yeah.

AZ: I only say that because I think about these fits and spurts you have to do.

KY: I really like to not work. I like to work really hard or not at all. I don’t like to be in the office messing around. It’s not a creative time for me. It makes me feel anxious, actually, that there’s something I should be doing and am not doing. What I like to do is I try to schedule everything really packed in the front, so I can get home earlier. I just don’t like downtime at work.

I don’t usually listen to music at work. I try to be as effective there as possible so that I can get out.

AZ: How do you deal with these insane sprints through awards season?

KY: I’m just used to it. You know, everybody talks about it now: “Oh, it’s so insane and so stressful.” I’ve been doing this for so many years. It’s really just what I do. And weirdly, I really suffer when it’s over. That’s the hardest part of award season for me.

AZ: Why?

KY: Getting back to normal. I have a very hard time making that shift. Maybe in the last week or so, I’ve been feeling like, “Okay, I’m back to normal, I know how to do this again.” Because I’m on high alert when I’m super-busy. I’m very effective. I get up with my kids, I make them breakfast, I walk them to school, I go exercise, I have meetings all day, I come back I make them dinner. It’s scheduled. I’m able to meet all of my goals all of that time. And I know exactly how long it’s going to last, and when it’s going to end, and that makes it really doable for me. But then, when it ends, I just don’t know how to live without all of that.

Usually, during award season, any time that I check my phone I have thirty to fifty new emails and most of them are just PR people trying to pitch me stuff. But as soon as award season is over, everyone in my industry goes to sleep for a month. So I don’t have any emails, I don’t really have much to do, and I don’t really know how to be. It just takes me a while to get used to it. I usually think that I’m going to go to museums, and go to yoga, and see my friends for lunch, and then I end up on my couch watching Netflix.

AZ: Well, there’s a depression that people talk about, when they finish a film or when they finish any sprint. You feel useless, in a way. Maybe over time we learn to respond better, use our time differently. But it takes time.

KY: Yeah, it takes me a whole month of this bizarre feeling.

AZ: I’d imagine that for some people there’s a version that is years. Like, “I just went five years straight, can I chill for a year?” The sabbatical idea. Which is really interesting. We had someone on another Time Sensitive episode, the designer Stefan Stagmeister, who does these sabbaticals every seven years. [Editor’s note: The episode with Sagmeister will be released this summer.] Which is so interesting. Instead of having retirement, spread years out across your entire career. But we all can’t do that if we’re in service to an industry that has a schedule.

But back to the awards: One thing I’m really interested in hearing about from you is, there’s an in-person experience when someone is wearing clothing, and then there’s the mediated experience when it’s presented on TV.

KY: Mm-hmm. They’re very different.

AZ: That seems to have changed over time, and has gotten more and more saturated. Do you design for the photograph?

KY: Yes. It’s all for the photograph.

AZ: Tell me about that.

KY: Well, all that matters is the photograph, because what we’re doing is press. I don’t do much real-life clothing. I will do it if a client asks me, but I don’t do a lot of real-life—what you should actually wear. I do press tours. It’s advertising, so it doesn’t really matter if it looks cool in person. Three people see it in person. The world sees the picture, so all the looks are for the picture.

I actually was talking to somebody about this the other day, because I tend to use these simple shoes a lot of the time. I’m repetitive with shoes. The reason for that is that a fussy shoe can make the leg look short and also can distract from the look. Whereas, in real life, I love a fussy shoe. I think it’s wonderful, when you go to a party, to have something that gives someone something to chat about. If you have a nice leg, and a fussy shoe on, and somebody says,“I like the cherries on your shoe,” you have a conversation. That’s the point of a cocktail look: to have some fun with it, to have something pretty, to have something interesting, to have something that makes people remember you or gets them talking to you. But in a photograph or movie press tour, that’s not what I want to see.

From Young’s Instagram, a Louis Vuitton dress.

AZ: Shoes are like a plinth for the body in that context.

KY: I don’t want to see a fussy shoe [in a photograph]. It’s bad on the leg. It’s distracting. It muddles the message.

AZ: Are you only focused on the front of the dress because of that?

KY: Yeah. A lot of times, that’s another thing: In real life, a plain dress in the front with a very dramatic back is divine for someone’s wedding, or a cocktail party, or an art opening, because it’s interesting. There’s something secretive about that. And bold. And sexy. For a press tour, though, it’s utterly boring and useless.

AZ: Right. And I read somewhere that you don’t use double-sided tape.

KY: No, I hate it. It’s so gross.

AZ: How do you get away with not using it? What do you use instead?

KY: Good tailoring. I mean, I have—I do use it. Sometimes it’s necessary. But if I can not use it, I won’t. I think it’s so gross. It’s always balled up with dirt on it. It’s disgusting.

AZ: [Your work] is all about tailoring in a way. Because you’re starting from the body. Do you have a team of tailors that you travel with?

KY: Yes. I have two tailors in New York and two tailors in L.A. that I really like. I have someone in London. I have two people in Paris.

AZ: Do you have ideas for how to alter the clothing to fit?

KY: The people that I work with are incredibly talented and skilled. I’m particular about tailoring.

AZ: Celebrity styling is one part of your life. But then you also move across a lot of different worlds, and now you’re designing, you’re doing all sorts of different things. Is there a throughline between these endeavors?

KY: I don’t know. I think the aesthetic is always kind of the same. With the celebrities, they look like themselves. But there is the color, the minimalism—there’s a theme. Like, when you line all of my clients up, you can see there are similarities.

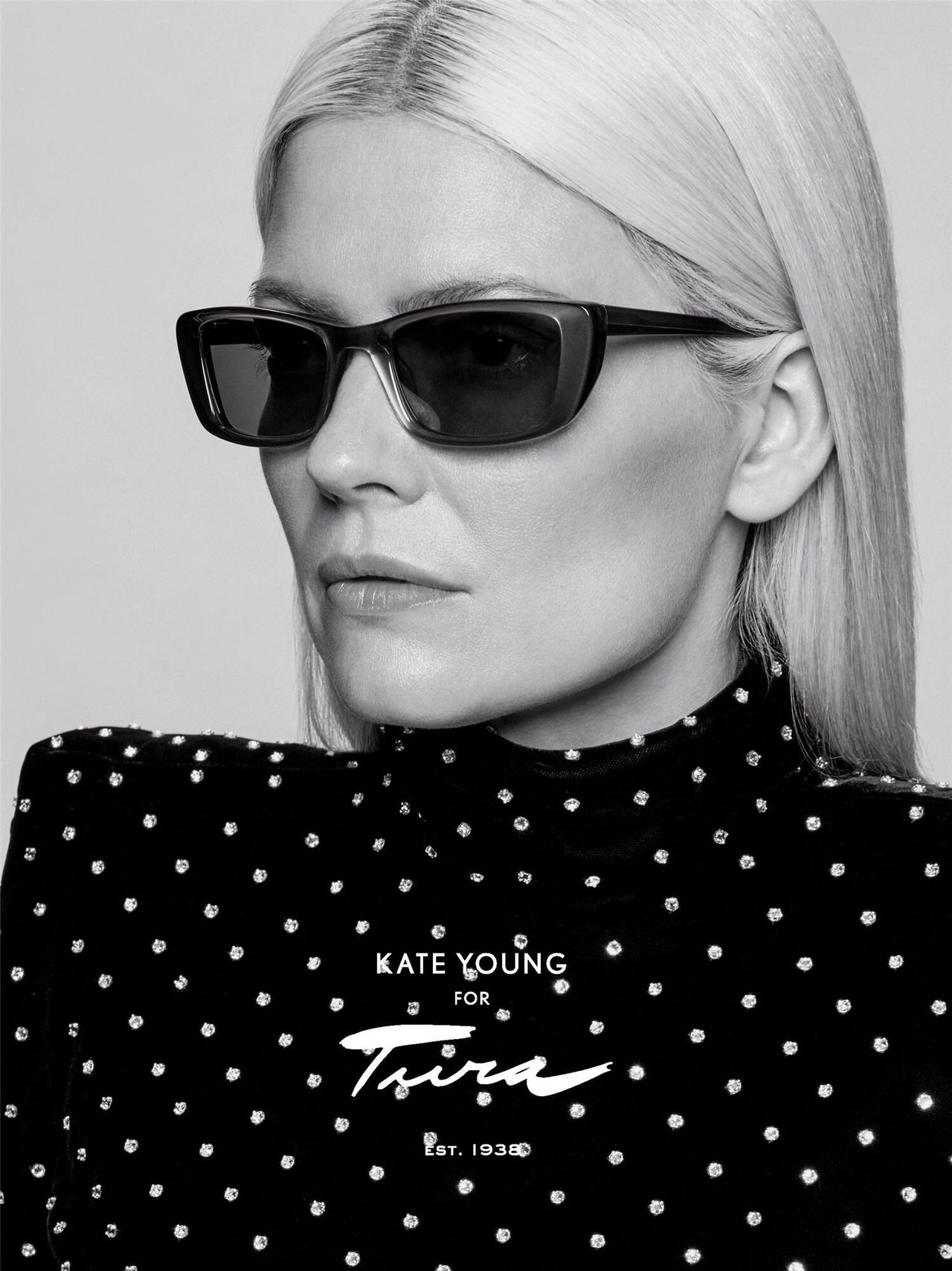

A campaign image of Young’s eyewear collection for Tura. (Courtesy Tura)

AZ: They also feel like the other things you’ve designed. There’s a simple elegance, especially in your sunglasses for Tura. What is that process like? Had you ever designed three-dimensional objects like that before?

KY: I had a line of lingerie in Japan for four years. Which was so fun. Yeah, but I love—

AZ: Is Japan a culture that loves lingerie? It’s not like the French.

KY: Yeah, it’s so interesting. In Japan, they have two kinds of lingerie: regular/everyday and then what they call “aggressive lingerie.” [Laughs] Which is actually like just what we would consider fancy underwear. For an out-to-dinner night or a date, they buy that. A matching fashion set goes with the outfit. It was super-fun.

AZ: How did you get into that? How did that happen?

KY:Jed Root was my agent at the time. He was hooked into Japan. You know that company Itochu Fashion System? I met with them, and they introduced me to Triumph, which is who I made the lingerie with for all those years. This was before street style was thing here, but in Japan street style was a huge thing. They had magazines devoted to street style, and they would photograph editors at the shows. I was really big in Japan fifteen years ago. I look like anime, and I think they liked that. The big eyes, small face—it’s a Japanese beauty ideal that doesn’t really apply here. But my small head and big eyes really did it for them, I think. I had a couple pages in Japanese Vogue where every month I would say what I was buying for the month and what I was wearing. And I worked with Figaro Japan a lot. So Triumph was super into working with me, and I had this line for four years.

“I was really big in Japan fifteen years ago. I look like anime, and I think they liked that.”

AZ: Woah. And did you spend time there and learn design there though that space?

KY: Yes, I had to go three or four times a year. I would go and do design meetings, and then we would usually go have some kind of party or launch for a new season, or I would do an in-store appearance.

AZ: Did you get into ryokans and the bathing culture of Japan?

The Kakou room at the Gôra Kadan hotel in Kanagawa, Japan. (Courtesy Gôra Kadan)

KY: Yes! Keith and I went and stayed at—did you ever go to Gora Kadan [on the grounds of Kan’in-no-miya Villa in Hakone]? Ugh, it’s the best.

AZ: [My wife] Niki and I went there on our—what do you call it when you get married and you on a …?

KY: Honeymoon!

AZ: Honeymoon. We went to Gora Kadan.

KY: [Laughs] Amazing, right?

AZ: Yeah, we went, like, fifteen years ago.

KY: Same.

AZ: It’s a very special place.

KY: Did you want a burger so bad when you got out?

AZ: It was just …

KY: So much gel.

AZ: Little fishes, little dishes.

KY: [Laughs]

AZ: For people who don’t know what ryokans are, they are these traditional bath inns that are really about texture. And I know people talk about this a lot, but I feel like I’ve learned more in Japan than I have anywhere else.

KY: Interesting.

AZ: About scale and texture. There’s something about Japan that we don’t—people think things are small there. They’re not. It’s not about being small. It’s just the proportions are different. In the meals, in the clothing…

KY: Yeah.

AZ: Did you ever get into Japanese vintage clothing?

KY: A little bit. Honestly, the vintage stuff in Japan is a little fetish-y. It’s not really my vibe. At the time that I was doing that, I had a vintage store. Do you remember when Rogan [Gregory] had a shop? Rogan and I had this shop …

AZ: Really? You had a store?

KY: Yeah, I had two retail things going at the time. I was sort of partners with Lorraine Kirke in that Geminola shop and then Rogan had a store called R Store. At the time, I was basically dealing vintage and had all of these people I was working with in Paris, New York, and L.A. I would go to Japan and try and figure it out, but found it all—it was too deep for me.

AZ: Yeah, they take vintage stuff seriously in Japan.

KY: It was also too expensive—they know too much about everything. But actually, Keith had a really amazing time shopping for records there. He would buy so many records. And I would go vintage shopping and be like, “Ugh!”

AZ: We’ve mentioned Keith a couple of times, we should probably tell people who Keith is.

KY: [Laughs] Keith is my husband.

AZ: What does Keith do?

KY: He has a record label [Mexican Summer] and now a couple of record stores. And he publishes books, reissues rare records, and made a movie [Self Discovery for Social Survival].

AZ: He’s a cool dude.

KY: Did he send you the link [to Self Discovery for Social Survival]?

AZ: I saw the movie.

KY: What did you think?

AZ: I loved it. And I’m not someone who can [sit and] watch surfing or skiing movies.

KY: They’re boring, right?

AZ: Kind of. I need conflict.

KY: But that movie is good.

AZ: It’s interesting because—we should probably plug that.

KY: Yeah, Keith’s movie. Netflix.

AZ: Netflix is putting it out?

KY: No!

AZ: Oh, they should know about it. Netflix should know that there’s a surfing movie produced by Mexican Summer and directed by Chris Gentile. About music and surfing, the relationship between the two. It’s very beautiful, it’s very exciting.

Do you find that Keith and you sort of inspire each other in different ways? He brings things into your life that you wouldn’t know about otherwise?

KY: Definitely.

AZ: And vice-versa?

KY: [Laughs] I don’t know about that.

AZ: Do you dress Keith?

KY: I tried to get him to wear a watch yesterday. I bought this watch, and I was like, “I think you should wear this.” Mainly because I want to wear it.

AZ: But it’s a man’s watch.

KY: I don’t think I inspire him in terms of his clothes. But I think we both have very different lives and aesthetics that intersect really nicely. I think we both really appreciate what the other one does. I do this sort of “luxury,” for a lack of a better word, this glamorous, glossy commercial work, and he does indie counterculture.

AZ: [His work is more] niche.

KY: Artistic. I think we both like what the other one does, and also can’t do it at all. At the record store opening [of Brooklyn Record Exchange] last night, I’m like, “Yeah, okay, this is a bunch of record pickers talking about stuff.” I literally didn’t understand an entire conversation I had. They were talking about some house music producer from the nineties and how the records are generally non-collectible, but this particular pressing … I was like, “I don’t know what you’re saying.” [Laughs] I might as well have been in Japan.

AZ: Like a knife pleat.

KY: [Laughs] Yeah, exactly.

AZ: Which is, I think, a good place to end. Thank you, Kate, for coming on the podcast, this was really nice.

KY: Thank you, yeah!

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on March 29, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by our director of strategy and operations, Emily Queen, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.