Episode 140

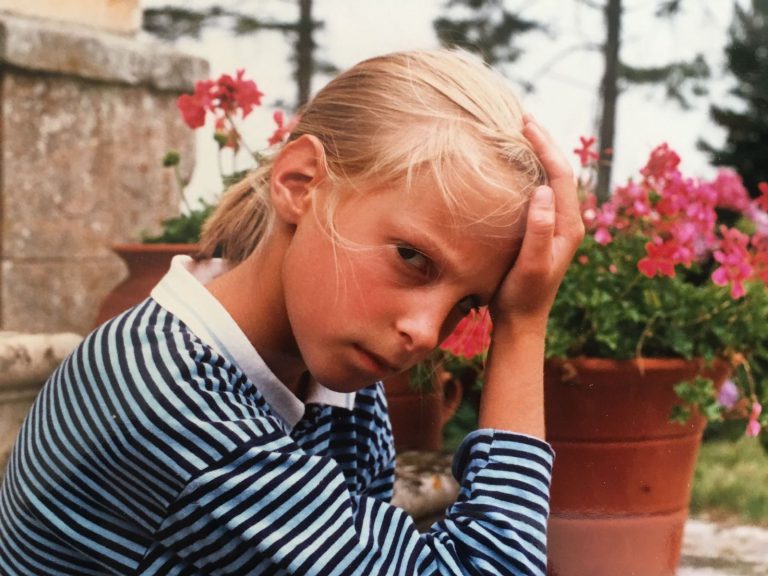

Camille Henrot on Tapping Into a Boundless Imagination

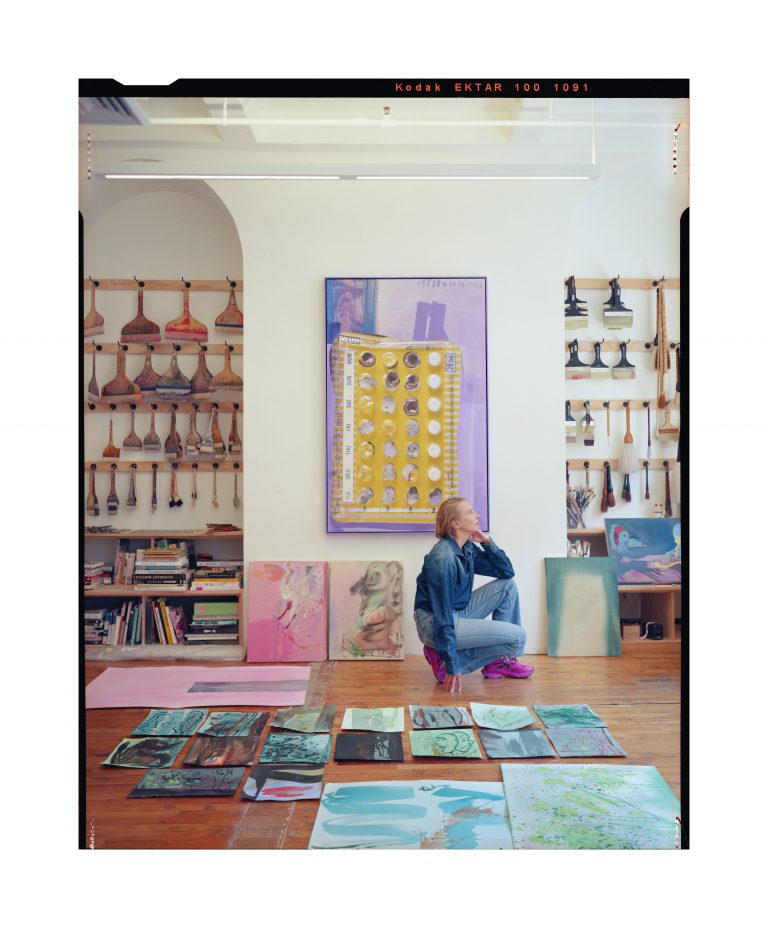

For the Paris-born, New York–based artist Camille Henrot, time practically never stands still. Across her work in film, drawing, painting, sculpture, installation—and soon, live performance—Henrot has developed ways of stretching and distorting time, seamlessly shifting from moments of potent intensity to quiet reflection. While her work carries a theory-driven ferocity and intelligence, it’s also incredibly playful, with humor and irony as key elements. Hers is serious art that manages—often with a knowing, subtle wink—to not take itself too seriously.

Henrot’s hunger to understand our world, in all its absurdity, and her fellow humans, in all their complexities and contradictions, frequently positions her in the role of translator, with a particular interest in uplifting often overlooked and quotidian aspects of society and culture. Questions of how knowledge is structured and how systems of control are formed—and the roles that time and coming of age play in that—are at the heart of her practice. Consider, for example, her breakout work, the 13-minute, intensely arranged film “Grosse Fatigue” (2013). The winner of a Silver Lion at that year’s Venice Biennale, the piece interweaves various origin stories of the universe across cultures via rapid-fire imagery and a pulsing, poetic voiceover.

On this episode of Time Sensitive, Henrot considers the subjectivity of speed and slowness; previews her upcoming first-ever performance-art piece, slated to premiere in 2026 and a collaboration with the nonprofit Performa; and reflects on why, for her, a work is technically never finished. She also shares her fraught fascination with animals, childhood, and the climate crisis—the intersection of which she examines in-depth in her soon-to-debut film “In The Veins.”

CHAPTERS

Henrot previews her forthcoming Performa project, which draws inspiration from the Italian Renaissance theater form commedia dell’arte.

Henrot discusses the making of her soon-to-debut film “In the Veins,” which examines the experience of raising children in a time of mass extinction and the climate crisis.

Henrot recalls her time spent studying the Japanese practice of ikebana, or flower arrangement, with a master from Tokyo’s Ikebana Sogetsu.

Henrot talks about the making of her breakout work, the film “Grosse Fatigue,” and shares a short audio excerpt of the voiceover by Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh with music by Joakim Bouaziz.

Henrot considers her ongoing interest in the beginning of life and coming-of-age experiences, how childhood impacts artists’ output, and her connection to the work of Louise Bourgeois.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Camille. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

CAMILLE HENROT: Thank you. I’m very happy to be here.

SB: So, let’s start with your plans for Performa, which, for those who don’t know, though I’m sure many of our listeners do know, is this incredible twenty-plus-year-old organization founded by RoseLee Goldberg. She’s been a guest on the show. This group has really been paramount, I think, in putting on groundbreaking performances over the past couple of decades, and I’m excited to hear about yours. I know, though, instead of debuting this fall for the Performa Biennial, your performance is now going to debut next year, allowing you more time, just figuring out all of the logistics and other things. Could you share anything about what’s emerging, what your plan is, what you’re working on for Performa—which will be your first piece of performance art, correct?

CH: Yeah. I’ve been really reluctant to do performance for a long time, and for me, the performance really feels at the opposite side of making films. When I got invited by RoseLee, I was excited because of the thematic—1925, that moment in history—but also working with RoseLee, and I felt I want to go back to my first experience of looking at a performance that I enjoyed, and I thought about The Muppet Show of commedia dell’arte with Harlequin and Pantalone, and Pierrot characters.

Researching that, I found out that it’s such interesting material, because the characters are very defined. Everybody knows what the role in society they’re expected to play. You basically have the doctors, which are the ones with power, knowledge, money, and you have the ones that are the innamorati, which are the lovers and that are naïve and innocent, and then you have the zanni, which are the thieves and mischievous and tricksters. I thought this is really so interesting to work with these categories as a given, as a structure.

Another desire was to reconnect what I liked in film with what I liked in performance. I thought a lot about Buster Keaton, for example, and Tex Avery. So we are using a lot of reference to that in terms of the way the body moves on the stage and the type of gags, but also the costumes. I say “we,” because, actually, one of the other attractions of that project for me was to do something collective. I’m working with a writer, Estelle Hoy, with whom I’ve already collaborated multiple times. We did an exhibition together at ICA Milano, and working with a scenographer, Adam Charlap Hyman [of Charlap Hyman & Herrero], with whom I’ve already done, oh, wow, five or six projects together.

SB: He designed your fireplace, didn’t he?

CH: Yeah, my fireplace, my exhibition at Hauser & Wirth last year, and for the exhibition before that. Then, he also invited me to his exhibition. If I put together all the projects, probably, it’s actually ten we’ve done together since we’ve known each other. Yeah. It’s a very exciting project because it’s combined music, dance, costume-making, and text in a way that I think I’ve never been able to do. [Editor’s note: Hyman has done scenographic installations in four of Camille’s solo exhibitions, including at the Salzburg Art Association in 2022, and Camille’s artworks have been featured in other exhibitions curated and designed by Hyman.]

SB: Well, I can’t wait to see it. I think here, I would love to ask you how you think about time and your art-making more generally. Performance, of course, is time-based—so is film—and it seems that, similar to the way your mind works, you stretch and distort time, just as you stretch and distort these ideas that you play with.

CH: Yeah, that’s correct. It’s exactly why I’ve been refusing to do performance for a long time. [Laughter] Actually, RoseLee did ask me [previously] to do Performa festival, and I told her that, for me, I felt really anxious about innovating in real time. Because one of the reasons I feel so attracted to film as a medium is the control you have over time—that you can stretch it, you can delay it, you can accelerate it. And the other thing is the control you have over space, too, because you can choose an angle, you can get a close-up, you can zoom in, zoom out—things that I feel with the stage you cannot really do.

Actually, as a matter of fact, while we were rehearsing, because we started to rehearse, I mean, to workshop, I would say more than rehearse, the characters and the movement, and very often, I was almost saying, “Okay, now we’re zooming in,” or “Now, can I get a close-up of that?” I realized, No, no, no, we cannot do a close-up. Then I was like, “Okay, the comedian needs to come more front stage, and the light…” You play differently with light and with body, but it’s definitely… I would say the main challenge of doing a performance is dealing with physical bodies in a physical space and with a physical shared idea of time.

SB: I mean, it’s much easier to make a mistake. You can’t go back and edit it, right?

CH: Yeah.

SB: Well, I think it’s also interesting that there’s a letting go that occurs in a performance, like acceptance, right? And your work, which we’ll get to, is at once totally wild and open and free, and still controlled in your way. Whereas, I think with the performance, you can only control so much. So, maybe this is a form of letting go as well, even beyond what you already…

CH: Yeah. It’s true that the whole idea of control is completely different in a performance. I would also say that one thing that makes this loss of control enjoyable is the personalities and the talents of the actors. Because what you’re losing in control, you’re gaining in improvisation and surprise, and, I would say, very often good surprise. I’m very lucky that we found already, not the totality of the cast, but most of the cast, and two of them are incredible actors, and it feels really like a blessing. I almost feel a little bit guilty, because I feel like, if the piece is a success, it’s not going to be so much because of my work. I feel like it’s going to be because of what they bring.

SB: Yeah, back to the collaborative that you were talking about. How do you see speed playing into this, and slowness, actually, like tempo, I guess I could say? In your work, I see both speed and slowness, and perhaps your work is actually interrogating the tension between the two.

CH: Hmm. Yes, that’s very accurate. I feel like maybe that’s because the way I perceive time, often, is with moments of intensity and moments of intense calm, in a way. I know that people who work with me or live with me say that I have basically two modes. One is extremely active. It’s basically raccoon mode. And the other is, like, sleeping-cat mode. [Laughter] So maybe that would be a little bit why I feel attracted to this idea of time being both really fast, but also really slow.

Maybe also because, in intensity, that’s the moment where we are aware of time the most. If you want to make time sensitive, in terms of sensible, like, being able to be perceived, you’d only be able to do that through an intensity of speed or an intensity of slowness, because there is no “normal” time. I mean, all these things are very subjective. Even the idea of speed and the idea of slowness is very subjective. What’s slow for someone might be very fast for someone else, and vice versa. You notice that a lot, actually, when you work across cultures, that some cultures understand time in a way that’s completely different. And the idea of the nervosity or concept of rhythm if you are in Naples or if you go to Switzerland or if you go to New York or if you go to Southern France will be completely different.

SB: Yeah. It’s like walking on the sidewalk in New York versus walking on a cobblestone street in Italy. You’re going to get a very different experience, right?

CH: I think Italy is actually very speedy. That’s why I feel very comfortable when I work in Italy, and there’s a lot of things from Italian culture in this project. The commedia dell’arte, I mean, as a start—the format of the commedia dell’arte and the characters. But I think it’s a very nervous culture and things happen really fast.

I would say the more you go north in Europe, the more things are slower in terms of rhythm… Patience has really a value rather than reactivity or impulsivity, or being in the flow.

SB: Yeah. The Norwegians invented Slow TV, so… [Laughter]

I know drawing is a core part of your practice. It’s a ritual, really. I mean, it’s more than a ritual. It’s just something you do every day. It’s like calisthenics or something. [Laughs] Could you speak to drawing as a ritual or as a habit, as almost something you impulsively need to do?

CH: It’s interesting, because the other day… During summer, I was in France, and I found out all the drawings that I was making as a child that my mom had kept. I mean, she probably didn’t keep them all, but she kept such a huge quantity of them.

Also, somebody asked me to create a little show with my drawings as [a child], so I had to dive in it. And what was really surprising is the extreme quantity of them, but also sometimes the fact that I would just repeat the same story. Very rarely it’s a drawing that’s unique. Very often, it’s more like a story. It’s like a storyboard, but in large format.

Basically, I’m repeating and imitating cartoons I’ve seen, but also, sometimes, it’s even like you just see a hand or a fist or the leg of a horse the same way in a manga or in a Tex Avery cartoon, you would just only see a moment of close-up. So, it’s funny because they were already storyboards in a way. And I guess maybe that explains why there are so many, and also why for me drawing is more a kind of training, or a process, rather than the desire to achieve something in particular.

SB: It’s a means to.

CH: Yes, exactly.

SB: Well, we’ll get to cartoons. I definitely want to talk about cartooning. But I next wanted to bring up “In the Veins”, this film you’ve been working on since 2020, and it explores the climate crisis language, and—I’m going to put it just very, very simply here, hopefully not too reductively, but—what it means to be a child in a time of mass extinction. Could you tell me about the status of this project, and also just what your aims are with it? What has it been like to work on this thing for the past five, almost six years?

CH: So the film right now is almost finished, edited. I have five more days of editing that I’m going to do in Paris in October, but I would say that now, we’re in a very good position. I feel the film is there, and the substance, the message, the shape of it, the style of it is very much defined, and I’m quite excited and happy. I mean, it’s rare that I’m actually really that happy about something I’m doing. So, it feels like a great joy actually to have reached that feeling. And now, we also have all the post-production to do. Most of my films have a sophisticated image treatment, and sometimes with animation, and it’s the case there. So there’s going to be a little bit of animation as well, and special effects tricks.

To respond to your question about how it’s been to work on a film for so long: It was already my dream when I started to do the project “Grosse Fatigue,” the film that was in Venice Biennale in 2014, was already, for me, the idea of… I like this idea to take on something that’s too big for you. That’s something… I’m interested in that. And for “Grosse Fatigue,” I really wanted to work on it for 10 years. I remember even I told Massimiliano [Gioni, the curator and critic], I was like, “Oh, I’m not sure I’m going to get it ready for the Venice Biennale because I was planning to do it for ten years.” Massimiliano looked at me, like, “She’s insane. Okay.”

SB: How long did you work on that film in the end?

CH: In the end, less than a year.

SB: Yeah, ten months.

CH: It was super, super stretched.

SB: Yeah.

CH: But everybody was like, “Oh, Venice Biennale, Massimiliano, you can’t say no. You have to get it ready.”

SB: I also think about the intensity of that film. I mean, we’ll get to it. Let’s stay on “In the Veins.”

CH: So, I’ve been wanting to work on a film that captured a long period of time in a short format for a long time. And when I started to think about raising children and how to represent that, and what does that mean, how did that affect my conception of time, my perception of the world and the future—the idea of the future is different with children. I mean, that’s a cliché. That’s something that everybody feels. And because the idea of the future is different with children, obviously, the perception of the crisis, and specifically the climate crisis, which is the main concern, I think it’s probably the first thing people think about now when you say future. They see or they think climate change, climate catastrophe, mass extinction. And it’s a pretty new situation that, when we think about the future, we think about destruction. We’re not thinking anymore about innovation. We’re not thinking anymore about an improvement of life. We think about the destruction of life.

That situation has been really, I would say, a source of sadness and a source of questioning for me. And I wanted to put that in film. In a way, I wanted to do a film I would like to see myself. So, I thought I haven’t seen represented in culture climate in relationship with intimacy, domesticity, and specifically the act of raising children. So, this is a little bit the purpose of the film is to try to capture what does it do to you, what types of emotion are involved when you’re raising small children in the moment of mass extinction, specifically with the dissonance between the pedagogical books and representations that are all full of animals and animal representation, and the fact that mass extinction isn’t addressed or explained or talked about at all in the media around us. And this type of contradiction, the fact that we are actually so attracted to animal shapes, looking at animals, touching animals.

SB: Cookie cutters [laughs], it’s everywhere. I mean, I would say animals are synonymous with childhood.

CH: Yes! And this is also an association I wanted to question. Why is it that we associate animals with childhood? Why is it that all children’s books are featuring animals, and that animals are totally absent—not totally, but mostly absent—from adult literature? I wanted to question: Where does this animal attraction die, but also, why are we attracted to animals as children? Why are we comparing children to animals? The little nickname, “Oh, my little cat, my kitty, my baby bear.” I don’t know in English, but in French, I call my children chatonne, which is like “kitty,” all the time, but I also call them, “Oh, my little snow leopard,” or “my little jaguar.” When they are swimming, I would say, “My little dolphin.” I’m sure I’m not the only parent that has this sort of natural association. It almost feels as [if] tenderness is the connection. We have tenderness for the animal world, and we have tenderness for children also, because they remind us of the animal world.

In the end, we are all mammals, so maybe it’s the beginning of all life is what brings us together with the animal world. There’s no reason it should disappear, in a way. For me, I see the destruction of nature and the disregard for mass extinction as an extension also of the disregard for childhood. And we only pretend we care about children. The reality is that you have children being abused. You have terrible situations around childhood everywhere, and not just the U.S., [which] is terrible. Even in Europe, children being placed in families that are abusive, you have a lot of Dickens stories, and they make the big title in the newspaper, but nothing is really done. It almost feels like, with childhood and with children, there is… It’s the same as with animals. We have a natural tenderness, but it’s not matched with a real bienveillance, a real desire for things to be healthy and safe for them. So, why? Why is that? Is it possible to have tender feelings, but actually no care?

It’s more like I’m bringing on the table a bunch of questions. I’m only an artist, so I cannot resolve such a big problem. But it feels important, and actually even urgent, to question the disconnection between action and desire for action, and what’s missing. It becomes, also, a little bit of a communication crisis. In a way, the ecological crisis is a communication crisis. People are really genuinely worried about the climate crisis and mass extinction, but they’re not really able to act on [it]. There is always some kind of denial. This is also something I want to think about. And mostly, I would say the purpose of the film is also to put in the light the giant gap between the young generation’s perception of the crisis and the older generation’s perception of the crisis, and to start to put that a little bit into perspective.

SB: Where does the name “In the Veins” come from?

CH: You know, I have a very weird relationship with titles in my work that I have this list of titles I do. And when I think about a project, I just look at this list. And I like that it’s slightly random, the titles. But I don’t know exactly. I don’t remember. I think I was looking at the veins of the wood in a tree, and I noticed how close it is to the veins of our bodies. It was during Covid, so there was this obsession around health. And I was making all these drawings, where you can see through people, so you can see their venous system and the heart. I think I was very anxious about the health of my children and my health. One of my children has a heart condition, so it almost… I think Covid made us all realize our bodies are fragile and complex in the way that we didn’t really see before.

SB: We are of nature, not separate from.

CH: Yeah, exactly. I think that these similar patterns between the veins and the construction of the wood was something I thought was beautiful to highlight. And also because the idea of the veins goes… it’s a bit like a river, it’s a fluxus. I wanted it to be a film also about the movement of life and the idea of [the] cyclical. The same way the blood circulates in a cycle in our bodies. The same way, I think, the day, as you care for children or animals, or as a caregiver, the day is cyclical. It’s repetitive. The film really establishes a strong statement on maintenance. The idea that cyclical time is the time of maintenance versus linear time, the Christian time, where God has created the world, and then once it’s created, it’s done, and there’s nothing else to do.

SB: So, in that sense, this is a sort of—not sequel necessarily, but—continuation of “Grosse Fatigue”?

CH: Yeah. In a way, it’s a film also about beginnings, because childhood is the beginning, and it’s also a film about creation. Everything about beginning is also about death. I realize it’s very difficult to talk about childhood and the beginning of life without thinking about death, too. And often, this is something that is being really put to the side as it has nothing to do with childhood. This is a very separate environment, but death is lurking everywhere around the question of the beginning of life and childhood.

SB: I mean, a century ago, it was a different conversation because most children didn’t live beyond childhood.

CH: Yeah, exactly. Maybe we believe that we’re out of that, but we’re not fully out of that. A doctor once told me that, actually, the place in the hospitals that has the highest mortality rate is maternity.

SB: So many places to go. I did want to just ask about the making of this film. What, for you, have been some of the most impactful or memorable moments?

CH: Wow. Impactful? There is this moment where, in Costa Rica, I was filming an animal wildlife rescue. So, this is one of the big parts of the film, is filming animal wildlife rescue and their work in their daily activity. And there was a sloth that they pulled from a cage, and they were explaining we’re going to replace her bandage and she’s a mama sloth that was pregnant, and by accident thought the electricity wire where… How do you say? What’s the word?

SB: A tree branch?

CH: Yeah, a tree branch, but actually more like vines. So, it’s a mama sloth that grabbed electricity lines instead of vines, instead of a branch, and she got electrified and she fell and she lost her baby, and she lost her arm.

I was overwhelmed by the emotion, and I started crying while I was filming because, yeah, it felt really like the story of that. And also, the wound was pretty difficult to see. They were repairing the wound with fish skin, which is also a bit like … feels like science fiction. They were applying fish skin on the wound. Yeah, that whole scene. I remember the DP [director of photography] and I were a little bit like… And we did a little moment after to catch our breaths and collect. But that was maybe one of the most impactful moments.

I still don’t know if I’m going to put it in the film, actually, because… I want to put it in the film, but my editor is very sensitive, and he keeps saying… I tell him, “Look, can we edit this?” And he is always like… I think he’s afraid of looking at that footage. So, we still have a conversation around whether this is going to be part of the film or not. So that was an impactful, heavy emotion.

I have a more funny story, too: I was directing my husband into washing the dog for the film. And the dog didn’t want to follow him, so I put treats in his pockets, but I also had treats myself because I’m usually the one who distributes the treats. She was following him, but every time she would just turn to me and look at the camera, and be like, “Am I doing well? Can I have a treat from you as well?” So then, in the end, I was like, “Okay, okay, I’m just not going to say anything.” But then, as she managed to go into the bathtub, without turning the head, I had this mom instinct to be like, “Good girl!” She jumped out of the bathtub and just ran away, and literally bumped the camera. [Laughter]

SB: Yeah. So, there’ll be beauty and heartbreak. I think a film like that should have all the feels, right? That’s what it means to be a human and a child in the face of climate catastrophe. I mean, facing the harshness of what reality is, what the world is, but also the wonder of what it is to be in the mind of a child.

CH: Yeah, exactly. Yeah, there’s a sense of wonder in that film, and I guess the post-production idea captured that, because I really wanted the film to have almost also the point of view of the child, too. So, there’s going to be drawing. It’s almost like you’re sketching an image to see through the image that follows. There are also animal stickers circulating on top of the image. Even though there’s a sense of drama and epic also in the film, but there is also a lightness to it. It’s difficult to actually describe it with words because it feels like nothing I have seen before, which is also why I’m so excited about it.

SB: I think, since we’re on childhood, we should stay there. And this is a subject you constantly return to in your work. And I wanted to ask you about your own. Your mother’s an artist and an engraver, and when you were growing up, your father worked in telecommunications, helped launch Minitel, which was this 1980s precursor to the internet. It was accessible through telephone lines. And I guess, without being reductive, but stating the obvious, it is striking—nd I wanted to ask—how do you think being surrounded by both art and technology impacted you as a child and, ultimately, today as an artist? There’s a through line. Again, not being too reductive, but…

CH: Yeah, yeah. No. I mean, it’s incredible how childhood impacts artists’ creation. Actually, when you exchange with other artists… I was talking with Ilana Harris-Babou, who’s a really good friend. She was explaining how she just realized that so much of our art is inspired by the subway station she was taking as a child to go to school, or, like, really specific… I guess it’s quite fascinating to be able to be connected to the intensity in which we perceive the world as children.

For example, if you touch an object or read a book that you haven’t seen since you were a child, you’re confronted a little bit with that emotion. Do you see what I mean? That the perception of everything was so much richer and mysterious, and intense. And sometimes you see a toy or an object, and you’re like, “Oh, this was such a magic object for me. This was so precious and so incredible.” Then you see that object and it’s just a little metallic box or an eraser, a mini eraser, that doesn’t have scent anymore, but used to have a scent, and seems to you at the time one of the most precious belongings you ever had.

I think maybe a lot of that impression of childhood survives in the work. And definitely, I can see how having so many telephones and Minitel and screens at home, but also that technology being a little bit weird at the time, because it wasn’t really… I mean, I didn’t perceive it as technology. For me, it was more like toys.

SB: Dad’s project.

CH: Not even. It was just, like, objects that were at home that we could play with, because with the Minitel, you could make drawings with the star and the different key. And I was spending hours doing that and drawing on the screen with a different key, aligning them. A little bit like writing codes, basically.

At the same time, yeah, my mom also was a taxidermist as well, as a side job. So there was also a lot of dead birds and wire, and weird—

SB: So, childhood and animals intersecting, right?

CH: Yes.

SB: Yeah. Which also, you’ve said, “I didn’t have a lot of friends. My friends were dogs.”

CH: Yeah. I found this really funny book at home also this summer, where there is a list of all the dogs I’ve ever met, with a bit like ID, like their name, age, estimation of age, and eye color.

SB: An Index of the Dogs I’ve Met.

CH: Yes, exactly. [Laughter]

SB: Well, I also wanted to ask about your grandmother, who you’ve described as a “professional storyteller.” She sounds really fascinating. You’re from the region of Brittany, in France, and she was deeply attached to the local folklore. Could you share a bit about her, how her love of storytelling left an imprint on you?

CH: Yeah. She was working mostly with schools, but also sometimes communities as a professional storyteller. But she was also a librarian, so she had a huge collection of children’s books and tales, in general. Yeah, there was a strong connection with the vernacular Brittany culture, which is very similar to Irish, in a way, where storytelling is also… It’s not so much only a children’s thing, it’s also an adult thing. Even something that just happened to you, your day, [can] become a storytelling somehow.

Then, also, in storytelling for children is integrated a certain darkness of life. I don’t know if you ever read Irish folkloric tales, but they are actually pretty dark. There’s ghosts and sometimes a character gets his arm cut, and then the head, and it doesn’t always have a happy ending. It’s interesting that there is no feeling of obligation for happy endings at all. In Brittany culture, you have a lot of that in the tales. You also have a lot of tales that make fun of Christian characters, like Jesus and Mary, and integrate them with the devil and with the hobbits. So we call them Korrigan, which are the hobbits of Brittany.

What really fascinated me as a child was the stories, the way different characters from different worlds of belief meet in the same story. It’s a bit like fan fiction. And the capacity also for storytelling to combine different sources of knowledge. It’s almost like a mash-up. I remember Roland Barthes in How to Live Together made that very interesting statement. You probably know about it. He said, “If a crazy man would decide to ban every department at the university but one, which probably will never happen,” he said. I mean, now, we are all worried it might happen. “If one department of the university needs to stay absolutely, it needs to be the Department of Literature because literature contains all the other forms of knowledge.” And he uses the example of Robinson Crusoe, saying that, in Robinson Crusoe, you have construction, you have architecture, you have economy, you have art of the military and war and animal care and agriculture, and spirituality, friendship, etiquette, social life. You have all these different areas of human knowledge combined in just one book.

SB: I mean, so beautiful and, in a very roundabout way, definitely connects to how you think and work as an artist.

If we’re talking about childhood, we also have to talk about cartoons—back to cartoons. And, in the case of your own childhood, that meant Japanese anime, which I was interested to learn was pretty common if you were growing up in a French household. That’s what was on TV. So, this Japanese-French exchange through anime. And you’ve said this later proved to be a huge inspiration or influence for you. Could you speak about some of your memories of watching Japanese anime? What do you recall?

CH: It’s funny. I remember that it was clear that some anime were not for my age. I was exposed to TV a lot as a child. I think my parents didn’t get the memo that you have to keep children away from screens. The programs of TV also were mixing adults’ and children’s production, as well. I remember looking at Cobra. It’s like an anime with a pirate character, and he’s really a little bit like a Don Juan, flirting a lot with women. And the women are super sexy, and there’s a lot of naked bodies in it. I was really curious. It was mysterious for me: What does it really mean? What happened between those characters? So this is an early memory.

I also remembered the one that I really hated. There was one called Princess Sarah, which was a character of a little girl who always behaved really well, and she’s always really nice to everybody, and proposing to help, but she’s also really badly treated. Everybody’s very mean to her, and she never rebels, and she’s always just crying. I really hated this cartoon. It provoked very deep feelings of rage. I felt there was like… I couldn’t understand this character not rebelling and not reacting to injustice.

SB: So, as an artist, you’re like the opposite character. [Laughter]

CH: Yeah, definitely.

SB: You’re like, “I’m not going to do that!” [Laughter]

CH: I’m definitely closer to Cobra the pirate than to Princess Sarah. [Laughter]

SB: Skipping ahead, at university in Paris, you continued on the cartoon journey. You studied animation, and then briefly worked in advertising. So, clearly, cartoons weren’t just something you loved as a kid. This was a transformative thing for you. You’ve said your intentions were not to become an artist, and yet you did. And I was curious, what was your initial path? When did you decide, “Okay, I guess I’m going to be an artist, after all”?

CH: Yeah, there was a lot of back and forth, I guess. During my studies, I felt a little bit conflicted because I was really interested in philosophy and literature, and a lot of the teachers said I was talented for this and that I should continue. But I felt such a strong drive towards drawing, and I felt all my school was really taking me away from drawing and painting what I wanted to. Also, music. I was very interested in music. I felt like I really wanted to do an art school. But I wanted to do an art school where I learned skills like craft. I was really interested in learning technical craft. I went to École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs.

It was the very beginning of learning programming to do websites, multimedia, using multiple screens. There was a video section. There was an animated-film section. It was really interesting for me and stimulating, and I chose that school because of that. I knew that there was a focus on media work. I was interested in learning the craft for that. I felt like I already had a lot of skills in drawing, because I had been drawing a lot, also with my mother, and I had taken a lot of drawing lessons. I was very agile in terms of drawing and academic drawing, so I didn’t feel like I would learn a lot if I [went] to an art school. And I wanted to learn how to make films, mostly animated and real-life films.

But once I was out of the school, it became really important for me to be able to make my own living. I wanted to go away from my parents’ house very quickly. I felt very unhappy there, so I needed a morning job right away. So, this is also where I started to work in music videos. Once I had all the contacts, I felt very happy. It felt really exciting, a very exciting chapter of my life, doing music videos. And very quickly, I also started to do advertisements and to direct teams for short films, advertisement-on-TV films.

There was a moment where there was a great sense of autonomy, and also a lot of learning how to use a machine, like the mechanical machine that moves the camera. I was very techy and nerdy. I loved learning, also the technique of post-production. But after a while, it felt a little bit like… I had all these meetings with marketing teams that lasted for hours. And there was a moment where also people were like, “I’m not sure you’re the right person for that. Maybe you have too strong of ideas.” My producer said, “I think you’re an artist.”

SB: “Oh, I am one.” [Laughter]

CH: Then I worked for Pierre Huyghe, because a common friend of ours said, “Oh, I think you should meet Pierre. You would get along. He wants to do something with anime, and he loves animals too. You two would get along. You should do an internship at his studio.” I went to work for him for a few months. Looking at him and the way he worked, I felt very similarly, and I think it really opened my eyes. It was an eye-opening experience for me in the sense I was like, “Oh, actually, this is something I could do,” or “I feel like this is maybe an environment I would be at ease and comfortable.” But I didn’t have the arrogance of thinking, “Oh, I’m going to be a contemporary artist.” But I just continued doing experimental films. But the idea was planted in my head.

Then a writer saw my work in a music festival, where I just did animated films to go with music, and he said, “Oh, I think I’d like to write an article on your work.” And when this article was published, I was contacted by a gallery. This is a little bit how it started. It wasn’t really completely planned and intentional. There was never a moment where I thought, “Oh, I want to become a contemporary artist.” But it happened in different stages and through a lucky series of encounters.

SB: And the thread also being film, right?

CH: Yes.

SB: Going all the way back to watching Japanese anime as a kid.

CH: Yes, exactly.

SB: Tell me about your project working in ikebana, because I found that was also pretty early on in your work as an artist. It’s called “Is It Possible to Be a Revolutionary and Like Flowers?”—exhibited at the New Museum also. You started this project shortly after moving to New York, I believe. And in simple terms, it’s a project about language, translation, literature, grieving, all of these things coming together. What was the process of making this work? Why ikebana? How did you choose that? And I know you also went to study at the Sogetsu School in Tokyo.

CH: Actually, no, I didn’t study with the Sogetsu School in Tokyo, but I collaborated with them when I did my first big solo exhibition in Japan. But I trained with a master from Sogetsu. But it all started really with a book I found on the street. Just before this podcast started, we had this long conversation about books, right? And I was just telling—

SB: And finding books on the street.

CH: Yeah, exactly. And I was living next to Sixth Avenue, and I was really interested with the books that people sold in the street there, and I often came home with a different book. One of the books I found on the street was a book about ikebana, an encyclopedia of ikebana. Shortly after, I found another book, but this way more like in a strip shop, with a different school of ikebana. And this is where I learned about Sogetsu, and I read that Sogetsu School’s philosophy was that anybody, anywhere, can do ikebana, that the teaching of ikebana has to be shared, and that you can use any material as well to do an ikebana. You can use metal. You can use wood. You can use found objects. You can use things that have been put in the trash.

I was really interested in this idea of ikebana being such an iconic image of beauty and perfection, but also the possibility to reach that sublime and that perfection through using materials that have been discarded. It was really the starting point. I started to collect things in the street,—a piece of pipe, tube, a vase—and use that as a material to start the ikebana. I would just buy a little bit of flowers, but I didn’t have a big budget at that time. So there were very few living flowers, a lot of them were dead flowers, or dried flowers, or paper even, or pieces of cable. That was really the beginning.

A little bit later, I started to think, when I had a studio visit in New York in my studio, I realized I often wanted to speak about a book, but I didn’t have my book with me. I also felt that my culture, where I come from, isn’t really known completely. I would say, for example, an author like Michel Leiris, very famous in France. He’s one of my favorite authors. I couldn’t meet a lot of people who know about him. If I had to explain why I like it, [it] was also difficult. I thought about a way to populate my studio with things that had been influential for me, as a homage, but also as a way to grieve that they’re not with me anymore. This is a bit how I thought, “Okay, I’m going to do this ikebana. They’re going to be an homage of the books that I’m missing.”

SB: So, it’s a transmutation from book to flower arrangement?

CH: Yeah, exactly. It felt like it really made sense because books are coming from plants. And also, we often think about the idea of ikebana as very specifically Japanese, but offering flowers for the dead or using flower arrangements to honor the dead is something that exists in the West and exists in many other cultures, as well. It felt a little bit like a very simple and consistent way to learn a new practice also for me. It became a little bit like drawing. It became like a training. At first, I didn’t really have an idea where it’s going to be shown. It wasn’t really a project. It was more something I was doing because I was interested in it, and it made me feel good.

Then, as I was working on it, I met Okwui Enwezor, who was creating the [Triennale] “Intense Proximities” in Paris, and I shared some pictures with him, and a little bit at the beginning of what I was doing. At that time, also, I had decided it was some kind of pause I wanted to take from making art and making film. I said I was planning to do that for two years, almost as an experience. I wanted to do two years of ikebana training and live in New York. And Okwui really liked the project. Because he invited me then to show them, they became a project, an installation, so to say. But in a way, for me, they are more a practice than a project or an artwork. And now, every time I’m—

SB: It’s like drawing almost, right?

CH: Yeah, it’s very much like drawing, in the sense also that it’s something that is easy to do, not very costly. It’s like there’s a lot of interest in the gesture. The gesture is important. There’s an economy of a medium as well. I guess because also I’m making films, and film is such a heavy… It’s a whole kind of… You have to put in motion so many people. You have to spend money. So, drawings and this ikebana practice was a little bit a way to breathe and stay active, and keep also a certain peace of mind, because it was very healing to practice the ikebana.

SB: I like that there was this ikebana pause, you could call it, or something.

SB: And shortly after that, you had what I think is fair to call your breakout project in 2013, 2014, “Grosse Fatigue,” this 13-minute video piece that, to put it really simply, it interweaves these origin stories of the universe across cultures via this rapid-fire stream of visual references and a spoken word voiceover that’s very powerful and repeats the phrase “In the beginning…”

I guess I just wanted to ask, because there was something you said connected to this project, which is that you really feel like it demands to be viewed in physical space, that it should be seen on a large screen in person, not on a computer screen. And I was just hoping you could elaborate a little bit on that. And maybe, if there’s an opportunity, we could play some of the sound here for the listeners because I think that the sound is almost as impactful as the film itself.

CH: Since “Grosse Fatigue” is imitating or mimicking the computer screen and the way the window opens and closes, it’s very important it’s not seen on a computer because the change of scale plays a role in the film. It was really the first time using and editing this technique of the window. Now it has a name. I don’t know if you read about that, that somebody was like, “Oh, ‘Grosse Fatigue’ is the first ’desktop film,’” because there’s many other—

SB: Oh, interesting.

CH: … film that reproduces [this style] later—

SB: Of course.

CH: … in art or advertisement, or even in cinema.

SB: Yeah. I was thinking about Adam Curtis’s film Hypernormalisation. I don’t know if you’ve come across that.

CH: I haven’t seen it.

SB: But it came out three years later, in 2016. And it very much is this idea of just being inundated, which, now, it almost feels like it’s just like we’re in an even more extreme time.

CH: Yeah. I was worried about the film being too much information. I was like, “How much information can people digest? Is this going to feel crazy for them?” And it’s funny for me now to think about that because we live in a reality that is so much more saturated.

SB: Twelve years later, it’s just like…

CH: But at the time, I was really worried about that. I remember I had my galleries and a few other people come to see the film, and I showed [it to] them in large screen, and I was like, “Do you feel it’s unbearable? Can you take it?” So, for me, it was really important that it was shown on a big screen. And still, now, I think it’s important because there’s a lot of detail you don’t see if you look at it on the screen. It’s very simple. It’s so condensed. It’s a very condensed film. It was made in a very condensed time and over a really incredible pressure. I think some of that intensity and compression needs, requires for you to have real space to digest it.

Then, also, yeah, the soundtrack, I think, is a big part of the film, and the vibration of it, the beat, the fact that it has a really strong bass system is really important. That’s why you always need a dedicated space in an exhibition. And when I insist on it, I try to tell curators that, “Look, it’s not really me who wants more space, is that if you put it in the space, it has this vibration to it. The sound is strong. And even if we lower—there’s this very low frequency that makes everything shake around it. So you don’t want to… Another artist wouldn’t want to share space with it.” It’s not so much like a luxury requirement of me being demanding—it’s just what it takes to show the work.

SB: Yeah, the felt intensity of it. But if it’s cool, I would love to share at least just a semblance of the audio with the listeners, because for those who haven’t seen the film, at least getting a taste of it, it is this speed we were talking about earlier, and rhythm.

[Plays first two minutes of audio of “Grosse Fatigue”]

[Editor’s note: The soundtrack of “Grosse Fatigue” is a creative work composed by Joakim Bouaziz, written by Camille Henrot and Jacob Bromberg, and voiced by Ghanaian American multidisciplinary artist Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh. The text is an assemblage of a collection of fragments of origin stories from scientific, hermetic, and oral discourses, researched and arranged by Camille Henrot and Jacob Bromberg.]

Could you also just share a little bit here about who made the music and the voice, which is so potent, I think?

CH: The soundtrack was written using a mythological story, a story of the beginning of the universe. He reassembled and he wrote it with the poet Jacob Bromberg. The music and the arrangement, and the recording was made by Joakim [Bouaziz] from the label Tigersushi. And the voice is performed by Akwetey Orraca-Tetteh, who’s an incredible artist. He’s also a visual artist. But at the time I met him, he was playing with a band called Dragons of Zynth, and now he’s also a visual artist.

SB: A great example, similar to what’s coming up with Performa, where you’re bringing in all these other collaborators to make this potent thing.

CH: Yeah. It was a really interesting experience, even though, I mean, we didn’t all meet, I remember, because we recorded in New York. And I’m not sure, actually, Joakim was there, but he directed the sound engineer, and there was just Akwetey and I. Oh, and somebody also from his band was playing the drum. And I liked the voice he had, and so I integrated him also. I asked. He has this voice that you hear that says, “Go on. Mm-hmm.” He has a lower voice that has this little moment of encouragement.

It’s interesting because we were all in different places, so it was like… I don’t think we ever had a moment where we were all together in the same room, even to celebrate the success of the film, because we were… Jacob was living in Paris, even though he’s a New Yorker; Akwetey was in New York; and Joakim was in between New York and Paris. The film was edited in Paris, but shown in Venice. I don’t know. It was a little bit like a puzzle with different pieces.

SB: And really, I think, introduced your work to all these new audiences and catapulted you in some respects.

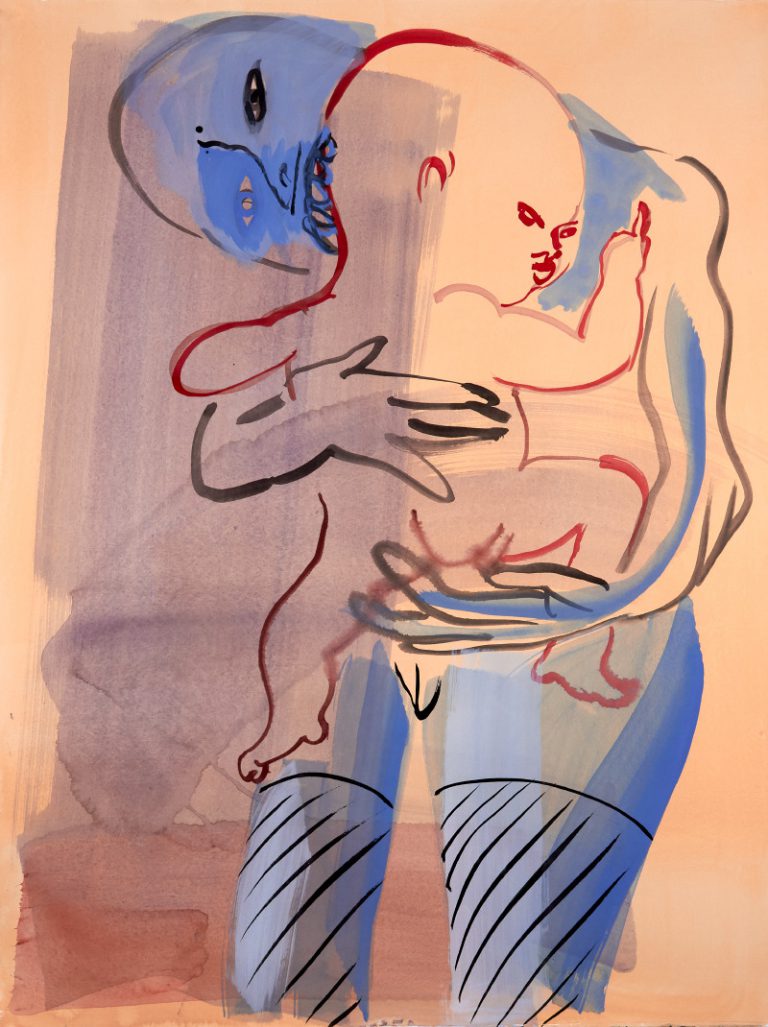

We’ve spoken quite a bit about childhood so far, but I also wanted to bring up parenthood—and motherhood. I feel like we have to have motherhood in this conversation, which is another theme you’ve extrapolated, I would say. I mean, one of the things I love about your work is you take these things that are so personal, and you’re able to extend them into the societal, the global, the universal. Perhaps we could start here with your Mother Tongue paintings and drawings that really explore in some sense the contradictions that come with both attachment and separation.

CH: It’s funny because it’s always the body of work that’s closer to you, but you’ve just kind of finished it that feels the most distant. So, what can I say? Yeah, “Mother Tongue,” I think it’s… No, sorry. It’s because “Mother Tongue,” actually isn’t the title of the body of work. Sorry, it’s because-

SB: It’s a work within… Yeah.

CH: “Mother Tongue” is the title of the show I did, which gathered this series of works. But the title of the series of work is called “System of Attachment.” And it all started, I think, in 2018, after I had my first child and I returned to the studio, and I thought that I wanted, really, to go back to work and just put everything behind. But then it was just like… I was just making those drawings, but they were very red. It’s so red that even somebody who came to the studio was like, “Oh, this is a blood factory.” It felt really like—the whiteness of the paper, I couldn’t handle it anymore.

Something about drawing became much more organic. Somehow, the energy behind those drawings became much more visceral. Very quickly, I started to layer it much more color. I also actually was interested in painting, which I never was before. I even had some strong disgust for painting itself—the texture, the odor, the smell. The whole kind of preciousness against oil painting, I really didn’t like it. But it felt like a medium I was attracted [to] at that moment, maybe because of the dirtiness of it, actually, but also because all of a sudden I was interested in the layering. And also, I had a different way to look at color, it felt. So this is how it started.

Quickly, I was also looking at my child and the way he touched objects, putting things in his mouth as a way to understand them. And I was reading all these books about how to be a good mother, which is basically how to understand your child when he cannot speak, how to understand what he means, and what’s happening in his brain. That becomes, really, a source of wonder and fascination, and questioning: what’s happening in the brain at the very beginning. The possibilities of connections are so vast. And somehow, I think artists, maybe we all have a little memory of that, this way of thinking that’s very impulsive, but also, like a monkey, can jump very quickly from one topic to another and connect those heterogeneous topics that aren’t determined too much by education. This is the way we artists have to think and function, but this is very much how the brain functions at the very early stages of our being.

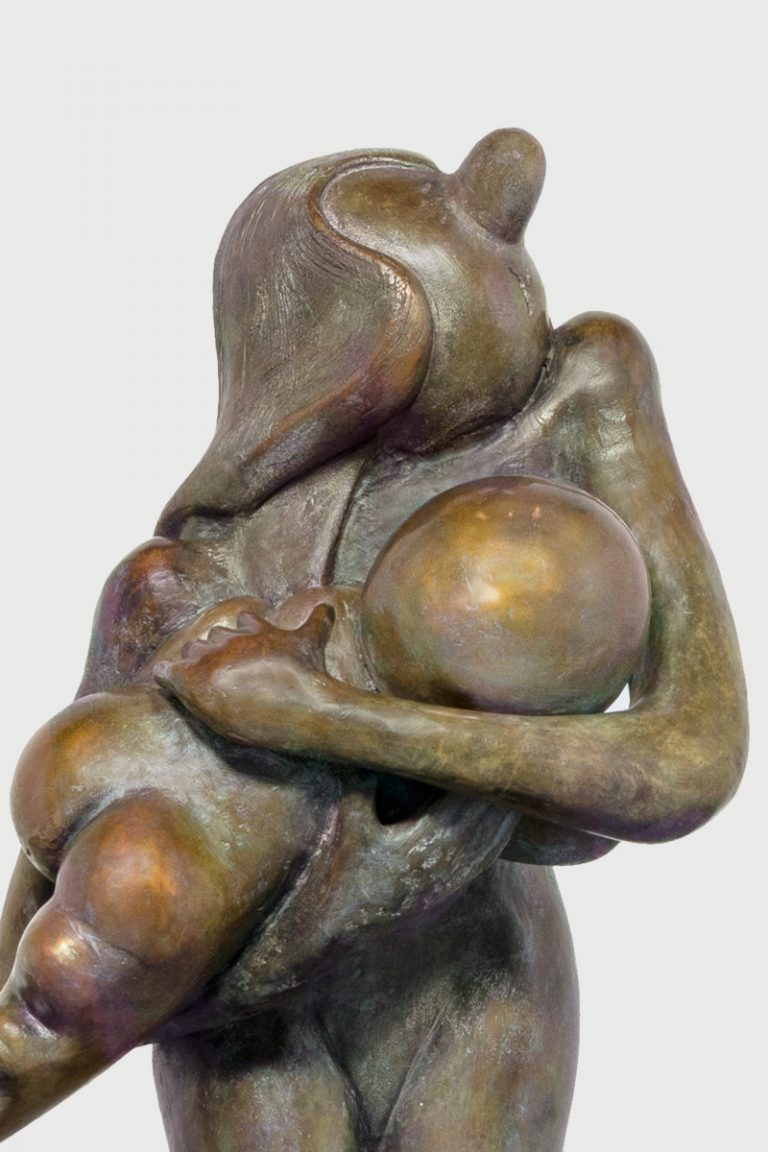

I became really interested in that, and basically, in the image and thinking before there’s words. And this is a little bit how the “System of Attachment” sculpture came from this questioning around how to think without words, how to think without image. The sensation of the touch, the tactile, as a type of perception being dominant, and how much, in the process of sculpture-making, but also, as when we appreciate sculpture, how much these early emotions of childhood are engaged or triggered or reactivated. So this was really a very exciting ground, it felt, for me, I would say, especially for sculpture, because of the possibilities that sculpture has. It is quite unique to be both an image, but also an object that you can touch and that you can turn around.

SB: There’s this dissonance at play between, let’s call it, childhood and adulthood, right? And I think your work, in a lot of ways, really gets at that: Where does childhood end and adulthood begin?

CH: Yeah, which is also why when you have a small child, you question also: Where do we separate, really? And do we separate, really? I guess that a lot of the experience of childhood caregiving questions the limits of our being: Where do my sensations end, and when is it that I’m actually feeling the emotion of the other person next to me? And I think this is a really interesting area of thinking: the porosity of emotion, bodies, and categories. I think if there is really one lesson from motherhood it’s how strong of an earthquake it is in terms of putting to the ground all the institutions, all the established knowledge, all the categories, how all those things get completely dismantled, and you want to build something new after that.

SB: Yeah. In that sense, your work isn’t really about motherhood—or this body of work. It’s actually about all the other things. It’s using motherhood as the vehicle toward those things.

CH: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I’m always surprised when people say motherhood is the theme, because I felt like, well, I don’t know, trauma and language and [the] tactile and the brain, and neurodivergence, these are all elements that are actually at play in this body of work. I don’t feel so much that questions around the emotion towards the child, which would be like motherhood, per se, are the topic of the work. It’s much more questions around the beginning of life and the development of life as it starts, basically. But it’s also, I guess, maybe the word motherhood is so problematic because it’s been subject to so many prejudices that it’s difficult. There is almost a shame to it.

SB: I know, also, in interrogating this subject, you went deep into the literature, including books by Adrienne Rich, Ursula Le Guin, Annie Ernaux. Could you talk about some of that reading and how that shaped you?

CH: Yeah. Actually, it all started with this incredible book by Moyra Davey, called Mother Reader, that a friend of mine, Jenny Schlenzka, who’s a curator—she was working at PS1 at the time, and she offered it to me. I guess now I remember. It’s because I asked her to pose for me, because I couldn’t remember the position of the hand when you breast pump, which is the act of pumping milk so that you can work and breastfeed your child at the same time, and I wanted to make drawings about that. I couldn’t remember the position of the hands, so I asked Jenny to pose for me. We talked a little bit about how little-represented this thing is, the pumping machine, how much it is like a dead angle, something quite taboo or unrepresented in culture. And she offered me the Mother Reader at that moment.

And she also sent me this Maggie Nelson extract from The Argonauts, when she’s talking also about the breast pump being this sort of dead angle of culture. But I would say that the Moyra Davey book was really amazing for me because it’s a compilation of texts, and some of them were authors I really loved. Some were authors I didn’t know very well. But it was very specifically about the complexity of being both an artist or a writer, and a mother, and how there was a very specific emotion connected to it. Some of them are emotions that are very rarely talked about. And I feel like it’s interesting, because at the same moment I was starting to work on it, mostly with images and sculpture, there were also a lot of writers who started to publish new books. There is a—

SB: Jacqueline Rose.

CH: Yeah, Jacqueline Rose’s [Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty] was one of them that I saw. Also, a huge inspiration for me. Amazing book. Yeah, it was interesting for me to feel that I was in sync with the moment, in a way, that at the same time, I was making those paintings and those drawings, and feeling a little bit conflicted if I’m going to exhibit them, or what should I do with it. Why am I feeling slightly ashamed to talk about it? I felt really supported because there were all these authors. Moyra Davey published Mother Reader a while ago [in 2001]. I think she was really in the avant-garde. Then, Maggie Nelson, as well.

SB: Right.

CH: Later, Jacqueline Rose with [Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty] and Donna Bassin’s Representation of Motherhood [from 1994]. So many other authors started to publish—or, we started to talk about [it]. Some authors actually published a while ago, but the books were not talked about at that moment. It became a little bit less taboo, or I wouldn’t say it became less taboo, because I’ve encountered sometimes very violent reactions to this body of work. But I would say that the awareness of the taboo was there. So there was an awareness that it’s a topic that’s difficult, that sometimes people react very violently to, or are very judgmental [about], or have really strong opinions. And this felt a little bit encouraging in a way. I guess I always was attracted a little bit to unresolved problems. So, in a way, seeing all these authors, this complexity, feelings of resistance was, in a way, even more attractive to me and a reason to continue.

SB: Yeah. Coming out of that time, the Metropolitan Museum did an incredible exhibition of Louise Bourgeois’s work connected to motherhood that I feel like really links to your work in profound and powerful ways, too.

CH: When I was a child and when I was younger, Louise Bourgeois was actually not so much shown in France. I started to know her work as I moved to New York. And it is really interesting because she was French, coming to New York, and she also was the daughter of an artsy, crafty mom, because my mom was also an artist, but a little bit like crafty. A little bit of a spider too, always doing something with her hands.

Yeah. I was just noticing the other day that we both married a protestant. Probably even, I think, I married a protestant also for the same reason. I mean, I fell in love, but I guess we were attracted to men who are not openly libidinous and have manners because… And also, a little bit like Louise, this very strong reaction to our family situation or family trauma. I guess I feel very connected to her work, to a point that, actually, somehow I couldn’t really… It felt almost too intense to look at it sometimes. A friend of mine wrote her biography and sent it to me, and it was really moving for me to read the biography of Louise Bourgeois. I could see a lot of commonalities.

SB: There’s a quote I wanted to bring up here that you’ve said, and this isn’t really a question. It’s just a beautiful quote, and I wanted to quote it. You said, “I don’t see myself as a mother when I work. I guess I see myself more as a child.”

CH: Yeah, it’s true, I guess, because I mean, if you see yourself as a mother, I’m not sure you can actually really make artwork, because so much about mothering, I would say, is to be reacting to the child’s need and desire and the moment. I’m not sure you can really build something. I mean, it would be an interesting artist work too, actually. I think the closest to being a mother as an artist would be the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles. The idea of practicing maintenance, that would be, motherhood put into an artwork, I would say. But, as for my work, I would say, yeah, I’m definitely more of a child.

I also think about this quote of Louise Bourgeois that I love so much, and I feel very similar to her. She said, “In my life, I’m a victim, but in my work, I’m a murderer.” I feel this is maybe the best quote about doing sculpture as well, because there’s something about sculpture that’s really violent. You use tools that are actually weapons: it’s knife, it’s hammer, and jigsaw.

And there is something pretty aggressive in the action of making sculpture, which is something maybe that she’s thinking about when she says, “I’m a murderer.” But there’s also another thing: the anger. The anger is a big motivation in my work, and often, when I’m being asked… I remember Massimiliano [Gioni], actually, in a talk, was saying, “Oh, some artists, they work with joy and also with anger.” I was like, “I’m definitely the one who works with anger”” I wish I would be working with joy, but I work with anger. But there is a joy in anger, as well.

SB: Anger can shift to humor.

CH: Yes.

SB: Anger can be funny if you let it.

CH: Exactly, yeah. There is definitely a connection with humor and anger. For example, a lot of my drawings come from satirical drawings. We talked about cartoons. And actually, cartoons come from satirical comic books, and comic books come from political satirical drawing. A lot of my references in drawing come from caricatures and the cartoonists in The New Yorker, but also the very old… I have a collection of reference [material] from the old revolution satirical drawing during the revolution in France in the seventeenth century. I have so many of them in my binder of references because I am really fascinated by those drawings, the way they caricature society into one image, and this is something that… Yeah, it’s a big motto in my work: a certain type of anger or resentment that then also manifests with humor, I guess.

SB: Mmm. Well, I think, as is clear to me—and I’m sure all the listeners—the way your mind works, it just goes in so many beautiful, wondrous [laughs], sometimes probably anger-led directions. Is there a place you would want to end this conversation? Because I feel like, unlike so many conversations, where it feels like there’s a natural progression toward an end—and I’m saying this intentionally because I feel like your work does this, too—it’s like… When do you know work is finished?

CH: Well, it’s actually really difficult. I mean, as you can imagine, I’m not good at putting limits.

SB: [Laughs]

CH: This is not my forte: endings, limits, simplifying, framing. This is not what I’m good at. When do I know that it’s over? I’m always trying to resist. I think it’s mostly external pressure that says, “We don’t have money. We don’t have time. This is over.” Very often, it’s under these external pressures that I have to decide, “Okay, this is going to be finished.” Except for drawing. Because I think with drawing, it’s really important to know when to end. And I also don’t like heavy-handed drawing or painting. I don’t like when it’s overdone, when it feels like you didn’t know how to detach and stop it. I know when to end a drawing, for sure. A film, a conversation, a bit less.

SB: Well, let’s end there. [Laughter] Thank you, Camille. This was a joy.

CH: Thank you. Yeah, it was so very fun.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on Tuesday, September 9, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Olivia Aylmer, Mimi Hannon, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Maria Fonti.