Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

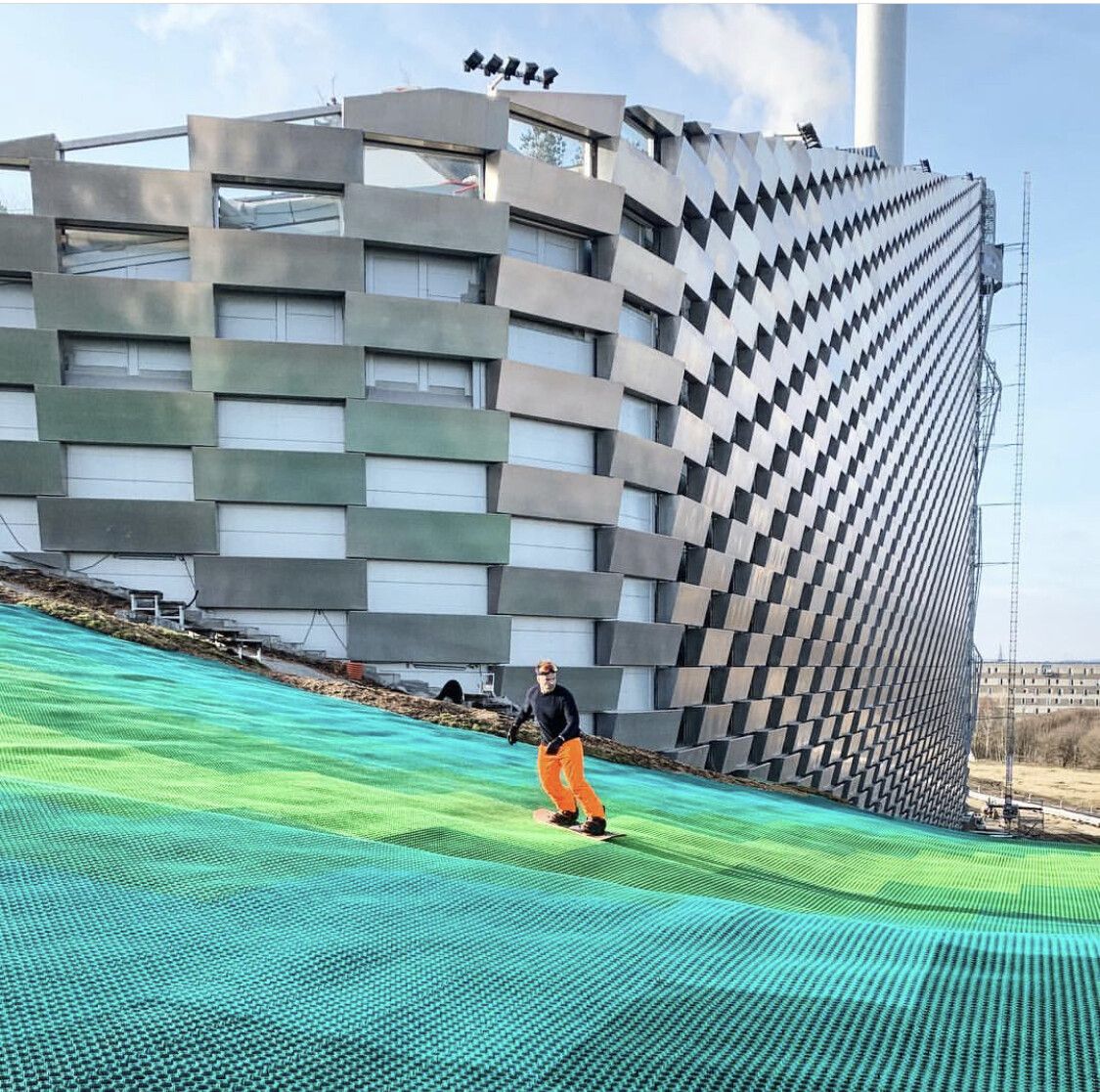

Bjarke Ingels in Copenhagen, with his Amager Bakke power station in the background. (Photo: Andrew Zuckerman)

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Welcome, Bjarke.

People know you as an architect, a designer, storyteller, a director of change. I want to talk to you about a subject dear to both of us: change. And I want to hear how you’re thinking about architecture these days in relationship to time.

BJARKE INGELS: The only constant in the universe is change, I believe Einstein has told us. [Editor’s note: Originally a quote from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, it was Einstein who proved this concept.] I think, since architecture is an incredibly old art form, you can say, whenever you design a school, someone has already designed some pretty amazing schools. One way to go about it would be to go and find the coolest school that has ever been built and make one more of them. It would be a pretty good thing to do, and it would improve on it in a lot of cases. But the only reason that that is not the full answer is that life is always changing.

“As an architect, if you can exercise your ability to listen and to look and to identify where change is happening, and where change is coming from, you actually have the opportunity to accommodate that change, to give form to that future that is about to happen.”

Whenever change is happening in the world we have built, the framework we have created for life will no longer fit exactly, because life has changed. As an architect, if you can exercise your ability to listen and to look and to identify where change is happening, and where change is coming from, you actually have the opportunity to accommodate that change, to give form to that future that is about to happen.

AZ: In your practice, you’ve often not just looked at the future or the present, but also the past. Can you give me basic idea of looking back into the history of architecture, from cave-dwelling to now?

BI: There are a lot of reasons why, if you want to gain confidence about the future—and you want to gain confidence about the future being different from the present—all you have to do is look back and see how different the past was from now.

If we start in a very large time scale, on one hand you can say that, as Darwin has told us, life has evolved by adapting to its surroundings. Life evolved, as we believe, at some sort of sulfuric events in the deep sea. Then, at some point, life migrated up on land, and in the beginning, land was a very hostile environment, because you had radiation from the sun that you didn’t really have under the ocean. But eventually, we found out that, to live there and then, life has migrated to new econiches and has constantly adapted to those econiches—until the point where we invent tools and technology and architecture. Because now, suddenly, in this case, man gets the ability to manipulate our environment and to create new environments. We’re not only in the position where we have to climb a tree to get away from our predators, we can actually build our own tree. We have to start thinking, What kind of a tree would we like to climb? What kind of tree would we like to inhabit? The same way we don’t have to just find a cave, we can actually build our own cave. Again, we have to ask ourselves, What kind of a cave would we like to inhabit?

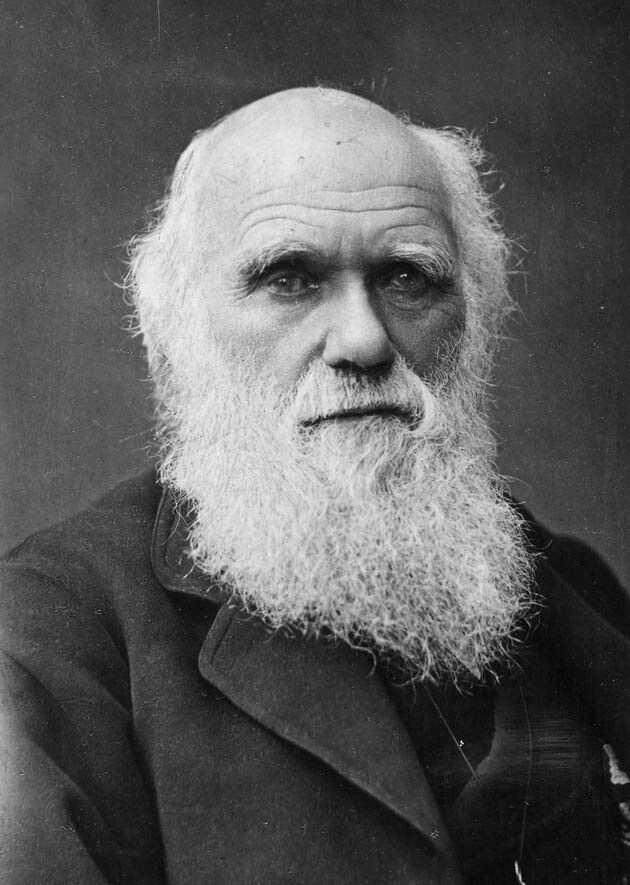

Charles Darwin. (Photo: The National Archives U.K.)

You can say, through evolution, we reach an inflection point where life that had been shaped by its environment over millions of years suddenly gains the power to shape our environment. So, rather than life shaped by the environment, now life can shape the environment. That’s truly where our superpower comes into being, that we now actually have this capability of shaping life around us.

I think a great way to explain the power of architecture and design is the Danish word for design, “formgivning.” Which literally means formgiving, to give form to that which has not yet been given form. In other words, to give form to the future, and more specifically, to give form to the future that you would like to find yourself living in, in the future. We’ve tried to look at those different evolutions of our environment through formgiving over time scales, and we’ve looked at what we call “the history and future of thinking.” Which is essentially the journey from the evolution of intelligence leading toward the genesis of artificial intelligence and collective intelligence. The history and future of sensing, which essentially is the journey from—you know, at some point, the Cambrian explosion, many believe, was when the ability of sight evolved. All of these different life forms that had been roaming around in the dark, only able to sniff and listen—suddenly, some of them started having the ability to see. Suddenly, predators that could see were much better at eating up others, and prey that could see was much better dodging predators. This new ability—sight—created this explosion.

But, of course, sensing is going to take us towards virtual reality and augmented reality, where we are going to blend virtual environments and physical environments into new multidimensional environments. We’re looking at the history and future of making, which is essentially the journey from craft to robotic manufacturing and robotic construction; the history and future of moving, which is essentially this journey of human migration, how humans probably evolved in East Africa and started migrating. Every time we went a little further, we had to invent new things, because in East Africa we can walk around as God has created us. But as soon as you get to Scandinavia, you need a fur coat, and you need a building; otherwise you’re not going to survive that winter. Essentially, as soon as we started inventing new technologies, we could migrate beyond our natural habitat, we could navigate the oceans. That history of migration is going to lead to a future of interplanetary migration. Definitely within our lifetime, we’re going to start migrating across a sea of space and get to other planets.

“Definitely within our lifetime, we’re going to start migrating across a sea of space and get to other planets.”

AZ: Formgiving has this inherent generosity to it: You’re giving a gift of something. I know that throughout your practice you’ve been exploring dogmas that you can attach yourself to, maybe through Lars von Trier.

BI: [Laughs]

AZ: A rigorous dogma is important to you. You have a big firm. It’s unwieldy. You have several different offices [in Copenhagen, New York, and London]; you need to develop large initiatives to lead these big teams. Tell me a bit about this idea of generosity that has come out of this exploration in formgiving.

BI: It came from the fact that, of course, by now we’re five hundred and fifty people. I’ve always been really skeptical of trying to put things too much into a method. Because I used to have this idea that if you write something down it’s already dead. But I’m also realizing that, for the feedback I’m giving, I often feel like a broken record. A lot of what I’m saying is based on some kind of fundamental principles, and maybe one last thing, if you look at law, or you look at the Constitution, it’s very rarely a list of things that you have to do. Because, if you prescribe something, you’re basically dictating what people have to do, and you’re dictating the outcome. Whereas when you’re saying you’re free to do whatever you want—there are certain things you can’t do, because it’ll inflict on the freedom of others, and there are certain questions you have to ask—then you are not dictating the outcome. But you’re imposing a certain rigor and what we’ve come to—

AZ: You’re recognizing an inevitable change that occurs since you’ve written a law.

BI: Exactly, if you’re dictating what people have to do, you won’t be able to address the inevitable change that people are going to face.

AZ: How do you accommodate for time amidst change? I mean, Aristotle talks about time being the measure of change. Time is our way of situating our self to that change. How do you develop principles that can accommodate change?

BI: What we’ve done now [at BIG] is decree this dogma of only three things—for now. Keep it simple. The first one is, basically, to oblige everybody to identify the change that’s happening, or has happened recently, within the field of their particular project. It can be in the neighborhood where the project is, it can be in the building code. But it can also be in the behavior of the program that’s going to go into that building, it can be in the technology that’s used to build the building. Whatever [you do] to make a survey of change, often you’ll find yourself to not just start doing what you already know, but really to identify those changes. You’ll be surprised to see how much change has just occurred in this particular field. Once you’ve identified the change, each project has to address the consequences and the conflicts and the problems and potentials that arise from this change.

AZ: That gives you a new purpose as an architect.

BI: That is exactly what it is. You have this new situation, nobody has really been here before because now we’re here, but ten years ago we were not here

AZ: You’re fighting the anxiety of influence that all architects face. In every field, it’s like, Who am I to the rest of the field?

BI: Exactly. Also, I know you mentioned Lars von Trier. He and I talked about a project recently, and he basically said he stopped watching movies when he graduated from film school. [Laughs] Which means he has a terrible time casting, because he doesn’t know any of the actors who are alive today. He has to rely on the kindness of others because he’s afraid of getting influenced. I think another way of dodging that cage of influence from others is to constantly remind yourself that the world has already changed since the last brilliant men and women did something. So that’s the first dogma.

The second dogma—and I think it came probably from this notion of formgiving—is: What do you form-give? You form-give a form gift.

AZ: [Laughs]

BI: Almost. Pardon my language. You can say an architect is a quite powerless profession, because we have to rely on the financial power of clients, developers, people that actually have the resources to build a building. We have to rely on the—

AZ: You have to rely on a provocation first.

Ingels snowboarding down the side of Copenhill ski slope on BIG's Amager Bakke plant. (Photo: Søren Solkær)

BI: Yeah. Someone has to be in the need of something, and to also have the resources to make it happen. But you also have to rely on the political power of the mayor of the city you’re building in, of the city-planning department and their regulations. Since we neither have the money nor the political power to make things happen [as architects], all we have is the power of interpretation. Then we can take all of the necessity that comes from the client, and we can take all of the rules and regulations that come from the city—there’s also a climate we have to respond to and all these other things. We can try to respond to that in a way that is not just answering all of the questions we’ve been given, but also putting something else forward in addition. We call this a gift. So the second dogma is that every project has to give a gift. And a gift is not philanthropy—it’s just making sure that as we’re solving this project we’re giving something back to the world, something that the world did not ask us for. It can be provoked by the identification of the change, it can be that the change actually allows us to do something that would have previously been unimaginable or impossible.

One clear example of this is the power plant we’re opening in Copenhagen at the end of April. Which is essentially the cleanest waste-to-energy power plant in the world. The change is that where a power plant used to be polluting—it used to be something that was noisy and dirty and you had to be as far away from it as possible—now we can actually turn the roof into an alpine ski park. You can hike, you can ski, you can climb one of the tallest climbing walls in the world. Suddenly, what used to be the symbol of a problem—pollution—becomes this celebration of a new kind of urban landscape. Obviously, the gift is that we turned the man-made mountain of the big building that the power plant is into an alpine park. We plant the seed in everybody’s heads that clean technology is not just better for the environment, it’s better for everybody. Because, suddenly, a power plant is not just some lost opportunity, a grey zone on the city map. It can be the most exciting place in the city, an alpine park in a city that doesn’t have any mountains. That gift becomes an exploration of the potential of that change. It also becomes not just a gift for the citizens in Copenhagen that can go and hike, climb, and ski there. It becomes a gift to the future. It becomes apparent that, with clean technology, everything we know about power plants and waste management facilities is no longer valid. It can be something completely different.

Darwin Ingels, posted on April 11, 2019, on the @bjarkeingels Instagram account.

AZ: It elevates expectations. From culture—

BI: Exactly, you can say—my son is four months old today.

AZ: Darwin.

BI: Darwin.

AZ: We should all hear why you named him Darwin.

BI: [Laughs] So I loved the idea—

AZ: Slight segue.

BI: Enter Darwin. I liked the idea that you could name your son after someone who has been very meaningful to you. I think Charles Darwin has, more than any other thinker, scientist, creative thinker, inspired me in how I look at the world, and how I look at the world of architecture, even though his field was obviously a different one. This idea that the simplest idea can be the interpretation that unlocks the most complex world. Not only has Darwin’s thinking unlocked how we look at the entire biosphere—everything that lives, and the complexity, the plethora of forms and ideas that inhabit the biosphere—his thinking also turns out to transcend the biosphere. Both the history [of it], because it also explains a lot of how non-organic landscapes have formed, but also how human societies evolved, how technologies evolved, leading deep into the future. That’s one reason why I think Darwin deserved—and you know I could call my son Charles, which would have been pretty brilliant, because he would have been Charles Ingels, which is probably the nicest dad you have ever seen, in The Little House on the Prairie. [Editor’s note: The Little House character’s surname is spelled Ingalls.] If anyone remembers so deep into our past. But Charles also sounded like the Prince of Wales. Then I looked up Darwin. Because English is my second language, I love looking things up. I’m often surprised what words actually mean—

“Charles Darwin has, more than any other thinker, scientist, creative thinker, inspired me in how I look at the world, and how I look at the world of architecture, even though his field was obviously a different one.”

AZ: Etymology, yeah.

BI: Darwin comes from Old English, which is much more similar to Danish, and it means dear friend. “Dar” is obviously dear and “win” comes from Danish—the word for friend is “ven.” So, dear friend. Actually, his mother’s name is Ruth, which means friend or companion in Hebrew. So I find myself surrounded by friends. Well, in any case, that was Darwin.

Enter Darwin, he’s now four months, and he probably won’t remember a thing until he’s two. He probably won’t even be aware that there was a time when you couldn’t ski on the roofs of the power plants in Copenhagen. Hiis entire generation is going to take it for granted: “Ahhh, we’re going to go to the power plant, that’s where we climb and ski and hike.” He’s going to have a completely different baseline, and therefore he’s going to have completely different demands and ideas for his future. In that sense, when you give the gift of form, you actually reset the foundation for the generations to come.

“Architecture is the medium; it’s not the message. It’s the container; it’s not the content.”

AZ: What’s the third [dogma]?

BI: Healing. Which is the history and future of human health, the human body. This goes, of course, from not only reactive medicine, but into proactive medicine, longevity, and also prosthetics. How we start not just healing what is broken, fixing what is broken, but also stopping it from even breaking—and even adding new abilities to our bodies.

Ingels as a young child.

I think, by requesting that each project has to insert itself into the future of one of these six fields, we ensure that we start maybe generating some new knowledge, start opening some new doors, start actually creating new avenues of exploration. One of the things that I find revitalizing about our practice [at BIG] is that once in a while I feel that we have exhausted possibilities, and I start feeling “Ugh, something new must happen.” And then we stumble upon one change, or we discover one new idea that opens up a door, and suddenly, through that door is an incredible unexplored landscape of possibility that somehow can feed us for many, many projects.

AZ: Well, maybe this is also where architecture has been moving toward: more social, more political, almost in a way that it’s less about buildings and more about the world outside of the buildings.

BI: Yeah, in some way, it’s a good reminder that architecture is the medium; it’s not the message. It’s the container; it’s not the content.

A cartoon by Ingels of his mother, drawn in 1992.

AZ: As a kid in Copenhagen, you took drawing pretty seriously. It was the first thing you were recognized for and got feedback from. Ultimately, why did you not become an illustrator, a graphic novelist, a—

BI: I had been drawing since kindergarten. It’s a little bit this idea that if you’re six foot seven, then you’re going to be better at basketball than your friends. You’re going to enjoy it a little bit more, and you’re going to be exponentially better at it. I was somehow just better at drawing than the people in my class. I got a lot of positive feedback for it, and it became rooted to my identity. Kids would come to me to draw this and that. And, of course, I enjoyed telling stories with those drawings.

It was certain to me that I was going to become a graphic novelist or cartoonist. But I had no idea how to go about it. There’s no Disney in Copenhagen. European graphic novelists come from Belgium and from France, and I didn’t speak French at the time. I found the Art Academy in Copenhagen, which is where the architecture school also is. The basic thinking was, I’d spent most of my life drawing things happening: people, animals, vehicles, emotion, doing stuff. I hadn’t focused so much on the background. So I thought, Spend a few years years learning how to draw the background, the buildings, the landscapes, and then go back into graphic novels. Of course, what happened was I fell in love with the background, and I stayed in that environment. It just shows you, if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans. I clearly hand an idea, and I clearly went elsewhere.

“If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans. I clearly hand an idea, and I clearly went elsewhere.”

AZ: Growing up in Denmark—it’s a different culture. I think that it has a lot to offer in terms of fearlessness and tempering ambition, in a way. Tell me a bit about growing up in Copenhagen, and why the invention of the thermostat could only have come from Copenhagen. [Editor’s note: The history of the thermostat is disputed, with perhaps the earliest examples being credited to the Dutch innovator Cornelis Drebbel in early 1600s in England; a pioneer in the field was Mads Clausen, a Dane who in 1933 founded his company producing the first thermostatic expansion valves.]

A sketch by Ingels when he was a child.

BI: Denmark is a culture that is, in many ways, very successful. It has a deeply rooted sense of equality. Everybody is born with the same opportunity, education is free, there’s a social security network, there’s free healthcare. My parents are well-educated, and I come from a very nice neighborhood on the beach in the north of Copenhagen. But I’ve only gone to public schools, to public hospitals, to public universities, so I essentially had the same opportunity as anyone. Which is a great thing. But there is also a deeply rooted culture that we’re all equal; there is a certain skepticism if anyone rises above the crowd.

I love the idea that the thermostat, as a mechanism, is essentially a mechanism that, if the room gets too cold, it will increase the temperature and heat it up, but if the room gets too hot, it will decrease the temperature and cool it down. It will basically make sure that the room will stay at an even temperature. And that’s essentially how Danish society operates. It will definitely lift you up if you fall, but it will also try to push you down if you rise above everybody else. So it has it’s pros and cons.

I think one of the reasons why Denmark can still be a cradle of innovation is because nobody there expects to become a billionaire. Because hardly anyone is. You pay two thirds of your income in tax, so you have to really generate some excess value if you want to become a billionaire. No one expects to become a billionaire, but no one is afraid of failing. And no one is miserable because they failed to become a billionaire, because they didn’t expect to become one anyway.

Ingels on his first day of school.

Ingels with a friend on top of a fort he designed and built with his father.

AZ: Taking fear out of the equation shifts everything.

BI: Exactly. So, when I graduated from the Art Academy, I went to work [in Rotterdam, The Netherlands] for my favorite architect, Rem Koolhaas, for a year and a half. Then, having realized that dream—which was my wildest dream at the time—I was sort of left without any new goals, except maybe trying to do it on my own. What better place to do that, then, by going back to Copenhagen. I was certain that no matter how miserably we would fail, we wouldn’t starve. Because there is literally a limit to how wrong things can go.

In the beginning, the first couple of years, it can be very hard to imagine that you’re ever going to make it. You work insane hours, you submit to all these competitions, you don’t get any money for it, and, of course, you lose a handful of them.

AZ: You’re not even that competitive of a person.

BI: [Laughs] You find yourself doubting if it’s really worth it. And then, at some point, I just realized—I had been on a holiday in Ko Phi Phi in Thailand, where I took a diving-instructor course. There was this Austrailian dude who had found himself in Ko Phi Phi. He had met a local girl from the island, he had some kids, and he was instructing people in diving in the most beautiful coral reefs I had ever seen. I always reminded myself that no matter how bad we would fail at what we were doing, I could always spend my last money on a plane to get to Ko Phi Phi, use my diving-instructor license to become a diving instructor, and basically live a life that for anyone, including myself, would be paradise.

“I always reminded myself that no matter how bad we would fail at what we were doing, I could always become a diving instructor and basically live a life that for anyone, including myself, would be paradise.”

AZ: But we wouldn’t have any of the buildings you’ve made.

BI: I was just thinking that that’s as bad as it could possibly go.

AZ: That’s not so bad.

BI: That’s pretty goddamn amazing. If I’m doing what I’m doing, it’s because I’m really excited about what I’m doing, even if I feel like I’m suffering a little bit. I would actually rather do this than live in paradise.

AZ: Back to the idea of change, which seems to be the main theme of your life and work. What was it like to leave Copenhagen for the first time, when you moved to Barcelona? What did you learn from that experience?

BI: Migration is essentially the change of habitat. It’s the source of almost all innovation in the world. If we zoom back in time, it was the moment when the fish, stranded on land, started discovering all these whole new capabilities. It was the moment when the monkey stepped out of the jungle and onto the savannah that it had to somehow rise on its back legs to look out over the far horizon and become better and better at balancing.

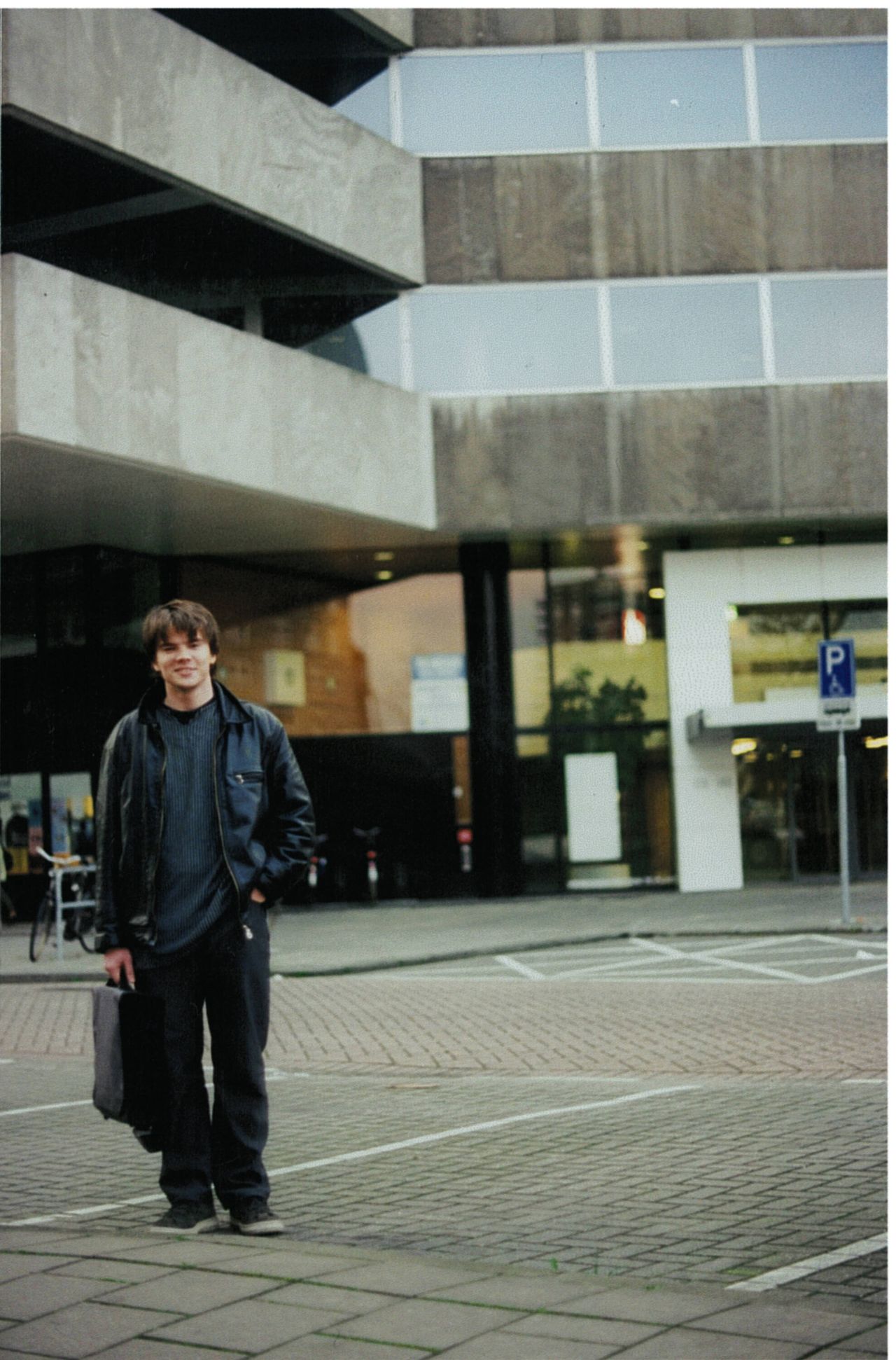

Ingels, age 23, in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, when he worked for OMA.

Everytime you migrate, new things evolve. One of the things, as a person, I actually believe—just looking at my son, they say, in the beginning, a baby doesn’t really have a sense of self. And the sense of self, actually, is not a deeply personal thing, It’s actually a deeply social thing. It’s something that happens in the interaction with the mother, the father, the family, the environment.

In Hermeneutics, you talk about the philosophy of interpretation and understanding. In Hermeneutics, you talk about having a horizon of interpretation, a horizon of understanding. Which is the world around you, with which you understand yourself. But because you are immersed in your own horizon of understanding, you can’t see it, because it’s the very background with which you see everything else. That’s why it’s so easy to see things that are foreign and so hard to discover things that are everyday. When you move to another culture—like when I was twenty-one, I moved to Barcelona to live there for one year—you immerse yourself in a completely different culture. Although still European, it’s Medeteranian and Latin—

AZ: You didn’t know anybody there.

BI: I didn’t know a soul. I also ended up meeting other people from other countries—a German, a Swiss, a Chilean, a woman from Corsica. I discovered that these people were taking certain things for granted. I was like, “That’s so weird” or “Wow, I’d never thought about that.” They would be puzzled by things I would say, that I would take for granted, that would allow me to sort of understand, “Oh yeah, I get it, I’m actually completely taking these aspects of life or society as if they were automatic and they’re totally not. They are an invention of Danish culture.”

“Every time you make a change of habitat, you open up a door for you to change.”

[Moving to another culture] allows you to adjust, because another aspect of this being so much a product of your environment is that your environment actually also keeps you captive. Your environment already knows—your friends, your family, they already know—who you are. So if you start being very un-Andrew-like, then suddenly they’ll be saying, “Andrew, what are you doing? That’s so weird.” Your environment has a tendency to keep you boxed in to the form that they already recognize as Andrew. But once you go to a new place—and I really discovered this right before going to Barcelona; we’d had a theme party where I was living, which was film-themed. This was in 1996. I was madly in love with Trainspotting, one of Danny Boyle’s early films. And I came as Sick Boy, with white bleached hair, a crew cut. Of course, you can’t unbleach your hair once it’s bleached. So I came to Barcelona with completely bleached hair. It attracted a completely different group of people, because I looked radically different then the way I normally did. I realized this sort of amazing thing: When you arrive to a new place, people will see you for who you are right now, and they’ll hear what you say right now, because they don’t have decades of history to lock you in. Not knowing already who you are, they’ll see who you are now. That actually allows you to become who you are now, and then, when you move back a year later, you come back to where you came from as who you have become.

The cover of an El Croquis monograph featuring architect Rem Koolhaas's projects from 1987-1998, published in 2006. (Courtesy OMA)

That one-year break actually allows you to transcend your past and become your new you. I’ve done it many times in my life. Next I migrated to Holland for a year and a half, I migrated back to Denmark, then I migrated to America. I spent last year back in Barcelona. Every time you make a change of habitat, you open up a door for you to change.

AZ: I want to go into your time at OMA. There’s a great story of how you got the job, which people can find, but what I’m most interested in is what you learned while you were there, what you took away from the experience at OMA.

BI: You know what they say, be careful what you wish for because you might get it? It’s kind of daunting for me to hear this. I was so in love with the whole idea of OMA. I read everything Rem Koolhaas ever said or wrote. And I had a pretty fixed idea of how it was. I was somehow expecting every person at OMA to be almost some kind of mythological creature. I realized they came from all over the place and had all kinds of reasons for ending up here. I remember someone had worked for Daniel Libeskind, someone had worked for Peter Eisenman, and I couldn’t even understand how could someone who had—it was almost like I felt that they were not pure enough. It was some kind of obsessive idea.

AZ: [Laughs] They didn’t spend enough time with El Croquis.

BI: [Laughs] Then I realized that OMA was a very heterogeneous organism. It was not at all this uniform movement. It was a much more complex organism that was somehow steered by incidental input from the chief curator, Rem Koolhaas. One of the things I noticed was the importance of production. I was probably much more cerebral at the time, and because the projects are so clear, I was certain they had been thought in the head, and then, once the thought was fully formed, it was put into physical form. I realized that it was the opposite: There was all of this production going on, sometimes almost aimless production of ideas and forms. Sometimes, I was frustrated at how almost mindless—

AZ: How iterative it was.

Ingels in his firm's first New York City office, in the Starrett Lehigh building. (Photo: Thomas Sweertvaegher)

BI: Exactly. But it doesn’t really matter where it comes from, or why it has been proposed; what matters is why it’s selected. Why do we choose to produce or pursue more of this and less of this? It’s the moment of choice that gives direction, not the moment of creation. Later on, of course, I’ve brought it back to Darwin: In Darwinian evolution, each new individual, each child that is born, is a random mixture of maternal and paternal DNA, combined with random mutation. The moment of creation—and I mean this literally—is never aimed at anything. There is no direction. But it is aimed through evolution, and in nature, it happens through selection pressures, which is basically that the individuals that are so successful at inhabiting the world that they live long enough to have offspring and to make sure that that offspring survives long enough to have offspring themselves. Those attributes are remembered, and all the other attributes are forgotten. That means that, again, it is the selection, it is the external pressures of the environment that give direction.

AZ: The thinking comes later. If you think about projects like [Rem Koolhaas’s book] Delirious New York, as you have had the great fortune now of taking the wheel at shifting the skyline of New York—as we will see over the next few years—do you think about Delirious New York? Do you think about New York as a unique place to fearlessly process, to fearlessly move forward?

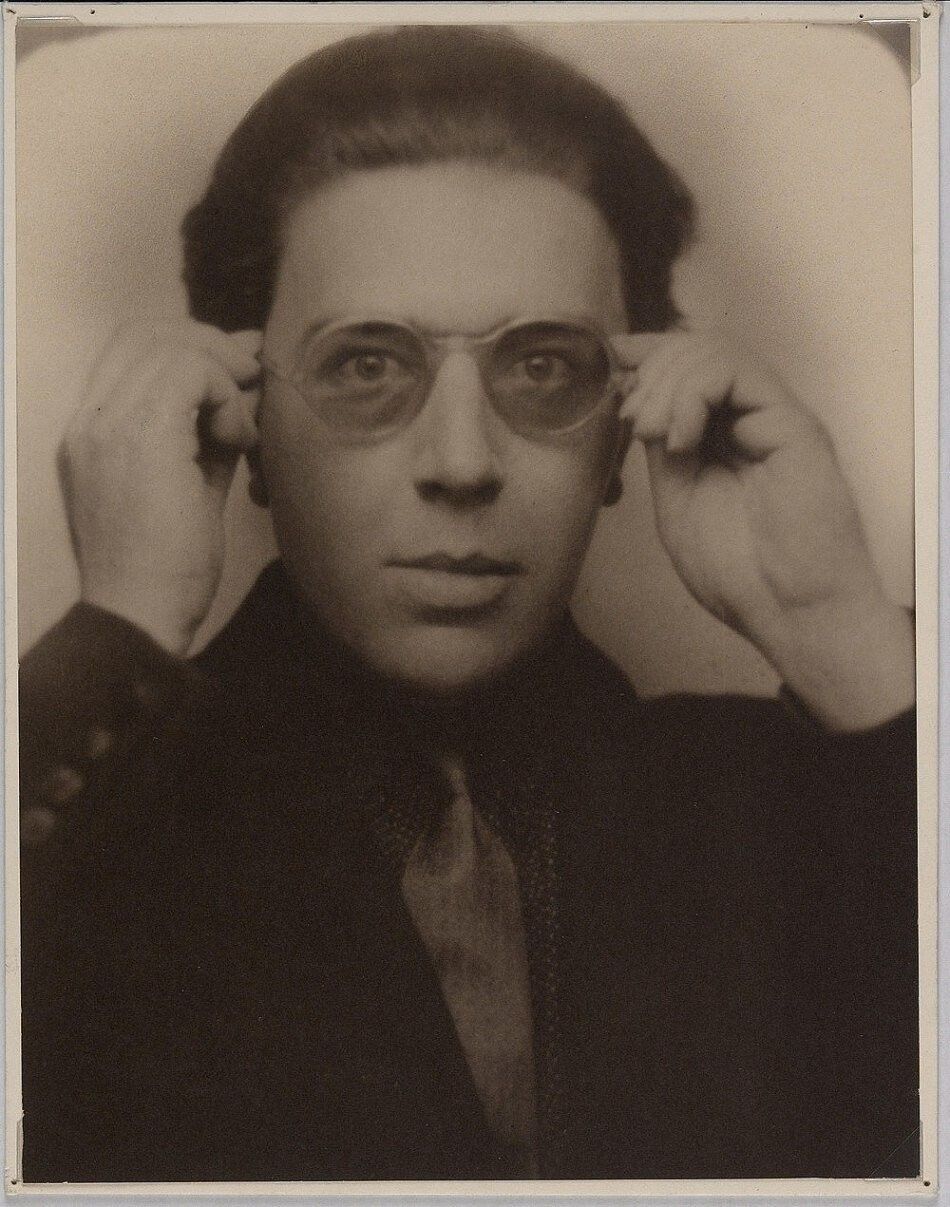

André Breton. (Photo: Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

BI: I think Delirious New York was a brilliant invention. It was Rem Koolhaas trying to say there was too much theory in Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century. All these manifestos of surrealism, modernism, international style, blah blah blah. But very little production, because, inherently, a manifesto is what you do before you have any evidence to back it up.

The brilliance of André Breton, when he wrote the Surrealist Manifesto, was because there were no declared surrealists. He starts pointing at [Pablo] Picasso, saying, “He’s a surrealist painter.” He points at Edgar Allan Poe, saying, “He’s a surrealist writer.” He just starts labeling all of these people that have nothing to do with surrealism and almost drafting them for his army of surrealism. Essentially, that is what Rem did with Delirious New York: He says there’s this mountain of evidence, with all of these skyscrapers, but there’s no formulated agenda.

AZ: There’s no plan.

BI: Exactly. So he retroactively writes the manifesto that produced Manhattanism. Which is a brilliant idea, and especially speaks to the power of the architect. You can’t really instigate the change, but you can interpret it and make it yours.

AZ: You can be the raconteur of the change.

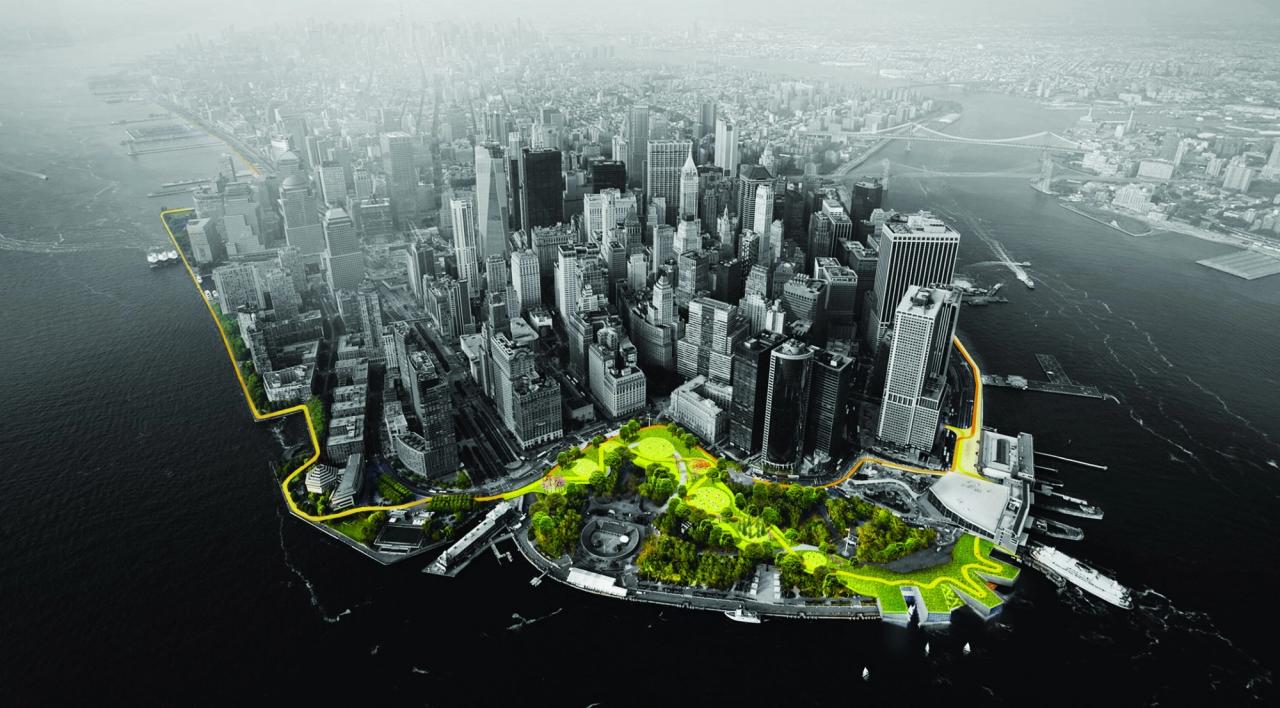

BI: Exactly. You don’t have the power to push the wave, but you can surf it when it flows through. I think, in a maybe somewhat similar way, one of the huge projects we’re doing here in New York that’s going to unfold over the next decade is The Dryline. Which is essentially the ten miles of resilient waterfront that we are designing for Lower Manhattan. It’s basically interpreting all of the necessary flood protection that’s going to keep Manhattan dry, but giving it form so that it becomes undulating hills, pavilions, giant pieces of furniture. Essentially, there will be a much more lively, much more environmentally and socially active waterfront. But it’s also what’s going to be protecting the city from the next flood.

A rendering of The Dryline. (Courtesy BIG)

AZ: It’s not an outlier. You’ve been grappling with these issues from the beginning of your firm: man and nature, how you democratize experience for the populus, how you protect from nature, how you engage with nature. Do you find that, even though every project that you’re doing now looks so new, it lacks a certain cohesive style? I don’t think of your buildings in the way I think of signature architects’ buildings. Hopefully you can’t pick out one of your buildings from it’s form, but more from its use.

BI: I would definitely take it as a compliment, because I would normally say that having a style is almost the sum of all of your inhibitions. It’s like a straightjacket that keeps you confined to who you were and inhibits you from who you could become.

AZ: You could have a functional style, an emotional style. But a visual style, we’re past it.

BI: I would like to stay rigorous in how we approach things, but I would rather be rigorous in the questions I ask more than the answers I come up with. Hopefully, the answers should always be informed by new information.

Another rendering of The Dryline. (Courtesy BIG)

AZ: People talk about vision all the time. Less now, but it used to be the hot word—“vision.” Now it’s “disruption.” But vision is—what is it? It’s an aggregate of our responses, and, in your case, an aggregate of your questioning. But as you move through all of these extraordinary projects that deal with nature in some way, it seems that your projects are becoming more and more long-term, more and more projective. The Smithsonian [master plan] is not going to be completed until you’re in your mid-sixties. The Dryline’s [completion] is years ahead. And then, your work on Mars—that’s deep into the future. Do you think about how—well, I want to tie it to one of your favorite writers, Philip K. Dick, and how he says that in science fiction the plot is triggered by some form of innovation.

So many of your projects now are in some state of waiting for innovation, or are in a state of innovating, and they just simply take a lot of time. Now in your career, which is quite young for an architect, you’re forty-four—

A rendering of BIG's Smithsonian masterplan. (Courtesy BIG)

A rendering of BIG's Mars simulation city for Dubai. (Courtesy BIG)

Another rendering of the Mars simulation project. (Courtesy BIG)

Another rendering of the Mars simulation project. (Courtesy BIG)

A rendering of BIG's Smithsonian masterplan. (Courtesy BIG)

A rendering of BIG's Mars simulation city for Dubai. (Courtesy BIG)

Another rendering of the Mars simulation project. (Courtesy BIG)

Another rendering of the Mars simulation project. (Courtesy BIG)

A rendering of BIG's Smithsonian masterplan. (Courtesy BIG)

A rendering of BIG's Mars simulation city for Dubai. (Courtesy BIG)

Another rendering of the Mars simulation project. (Courtesy BIG)

Another rendering of the Mars simulation project. (Courtesy BIG)

BI: Yes.

AZ: Which is a baby in architecture.

BI: [Laughs]

AZ: Are you moving into a space now where the projection of time is so far ahead to accomplish the huge ambitions that you have [at BIG]?

The BIG-designed Panda House at the Copenhagen Zoo. (Photo: Rasmus Hjortshøj)

BI: Definitely. When you start your practice, and I started twenty years ago—nineteen years ago with my first company, PLOT, which somehow grew to where we are now—you’re so impatient for evidence of what you’re capable of doing, because there is always a huge discrepancy between the reality that you know you’re capable of and the reality the world can see. The reality the world can see is coming five or ten years later. For example, this year we are opening eleven buildings: three museums, three skyscrapers, the power plant with the ski plant on the roof, a habitat for pandas in the Copenhagen Zoo. Some of the projects have been nine years underway. That means that this year—2019—the world can see finally what we somehow knew nine years ago. You’re dying to catch up.

The Panda House at the Copenhagen Zoo. (Photo: Rasmus Hjortshøj)

I think, at this point, we’ve reached some level of satiation, and we’re starting to understand that because something takes a long time that’s exactly why you have to start now. Some of the biggest challenges we face right now, like if you look at projections of climate change and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, you’re often talking about plans for 2030. Which sounds far into the future but actually 2020 is next year, right? And 2050 sounds really abstract, but human beings used to build cathedrals. Cathedrals take between one to three centuries to make, and back then the average life expectancy was, like, forty-five years. So three hundred years—that was many generations. And we still built the cathedrals. Like in Barcelona, they’re still building the Sagrada Familia, because it’s only been underway for one hundred years.

We have to somehow regain—you know, just because it is going to take one hundred years, maybe, to put a small city on Mars means that we actually have to start now, because otherwise we won’t get there in one hundred years. All of these huge projects that take long-term commitment are actually the most important projects we can engage with, and the fact that we might not see them realized in my lifetime is even more of a reason for getting them started now. I think all we need to do is visit the Duomo in Milan and marvel at this incredible feat of engineering and art and architecture, and know that centuries and generations were put into this. Many of the people involved never saw it finalized. The people who actually saw it finalized had no idea how it was initiated. But everybody still saw the importance of realizing it, and I think we have to look at our future on this planet and our future on other planets in a similar timescale.

AZ: The hyper-digitalization of today, the onslaught of the Silicon Valley explosion that happened in the last ten years—do you think this is in some ways informing your concerns with nature? Do you think that you’re actually being pushed away from technology, or the way that technology has been presented to us in the last ten years, and toward nature? Are you hoping that your buildings and projects will help us engage more in human connection and less in a straight relationship to mediated experience?

An aerial view of the BIG-designed Lego House in Billund, Denmark. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

BI: I think we’re at the dawn of this new era, where we’re about to step back into physical space. A lot of invention, a lot of ingenuity, a lot of investment has been focused on the digital, on the virtual, and on the tiny—in Silicon Valley, in the last four decades.

If you say the first global platform was the internet that connected all information, and the second global platform was social media that took human relationships and connected them and made them subject to the power of algorithms, the third platform is when everything else gets connected and becomes self-aware. Somehow, the digital and physical world are going to come back together again.

I just looked at some statistics, and if you look at—we just took an arbitrary marker, or maybe not so arbitrary, the launch of the iPhone in 2007. You see how the sense of loneliness has just started spiking, and has been going up ever since among eighth, tenth, and twelfth graders. The decrease in sex. All of these sorts of symptoms. Being connected digitally is making us disconnected socially and physically, and I think there’s a huge opportunity now to rediscover and reinvent the significance of meeting in physical space. It’s the rediscovery of collective intimacy in physical space and the communal. That’s one thing.

Another thing I see is, if you look at the most exciting projects that have happened in Manhattan over the last decades, it’s actually the Hudson River Park, The High Line, Brooklyn Bridge Park. The Dryline is coming now on the east part [of Lower Manhattan]. It’s basically making the city more inhabitable for the citizens living there, and in some ways bringing nature back in. You have Brooklyn Grange on the rooftop of a warehouse in the Navy Yard—it’s the largest roof farm in New York State. I think nature, agriculture, all of this is coming back into the city. The dichotomy between countryside and city is unproductive and makes more sense to have it around us.

The last thing why—and this is something we’re trying to actually to imitate it in the city—is that cities environments are so over-coded. Anyone who is—Andrew, you have three kids who have grown up partially in New York City, you have to teach them that you have to walk on the sidewalk, you have to stop at the crosswalk, you have to wait for the green light before you can go, and if you hang out too long on a stoop, you’re loitering. A city is such an over-coded environment that you can only do what you’re supposed to do. If you’re a grownup without a kid, you can’t hang out on the playground, because then you’re a potential pedophile. There are all these things that you’re not supposed to do. You’re not supposed to walk on the grass, whereas in nature, it’s uncoded, it’s free for interpretation.

In some ways, nature is a grownups playground. You can actually do whatever the fuck you want in nature. You can climb a rock, you can try and climb a tree, you can fall down, you can walk through the swamp, get wet feet. You can do all of those things you wouldn’t really do [in a city]. Like, if you’re walking through the fountain in Lincoln Center, you’re probably asked by the guards to get the fuck out of there. In that sense, nature also has this freedom of codification that makes you rediscover random experimentation and freedom of movement that you have somehow lost in the urban environment.

A view of the BIG-designed Via57 residential complex on Manhattan's West Side. (Photo: Nic Lehoux)

Ingels' Serpentine Pavilion in London in 2016. (Photo: Iwan Baan)

AZ: So many of your projects are trying to reintegrate that and trying to bring that in. And are why architecture might save us.

BI: One of the gifts that architecture can actually give us is opening up some places that are not yet fully coded, where human behavior is not yet fully dictated. It actually opens up the possibility of free behavior and of a human encounter.

AZ: Amazing. I think we’ll wrap it there, unless there’s anything …

BI: Um, I think you can cut here …

AZ: I’ve done this once before—cut you off before you were finished.

BI: [Laughs] I think there’s maybe one sort of general thing, but it’s not a fully formed thought.

AZ: I like that.

“Maybe time, combined with space, is just an arbitrary measurement of movement. And maybe, just like how the only constant in life is change, the only thing we really have is movement.”

BI: It’s also something you and I have talked about previously. Because your medium is film, among others, and if architecture is—you know the medium of architecture is space. But what makes it life is when people start moving through space. Sometimes I’ve had this sense, which is maybe meaningful or not—just like you can say length and height and depth, the X, Y, and Z axis are arbitrary measurements of that which we know is space. Maybe time, combined with space, is just an arbitrary measurement of movement. And maybe, just like how the only constant in life is change, the only thing we really have is movement. And time and space are just arbitrary markers, or dimensions, of that. Both space and time become these ways for us to fathom movement, this much more hard-to-grasp object. Because we are part of that movement, we have a hard time seeing it. But by focusing on either time or space, we can see aspects of it. The one true thing that is really there is movement, and we are part of that movement.

AZ: What you’re focused on is tracking that movement, and trying to accommodate that movement, and making space for what’s ahead that we move into.

BI: Exactly.

AZ: Which is what I think makes your practice so special, and your whole potential for what we see from you in the next fifty years.

BI: [Laughs]

AZ: Thanks very much for coming on.

BI: A pleasure, man.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on Feb. 6, 2019. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. This episode was produced by our director of strategy and operations, Emily Queen, and sound engineer Pat McCusker.