Episode 131

Billy Martin on Finding Harmony in Rhythm and Life

The drummer, percussionist, and composer Billy Martin, whose name many Time Sensitive listeners may recognize—he created the Time Sensitive theme song, which he recently updated ahead of our current season—defies any boxed-in or limiting definitions of his work. Best known as a member of the band Medeski Martin & Wood (MMW), he’s spent the past three-plus decades making experimental, boundary-pushing, and uncategorizable instrumental jazz-funk-groove music alongside the keyboardist John Medeski and the bassist Chris Wood, shaping sounds that feel as expansive as they are definitive and distinctive.

Across all his artistic output, Martin continually, meditatively searches for harmony. In addition to his drumming and percussion work, he is a composer (with several soundtrack scores to his name), a teacher (he has been a part-time faculty member at The New School since 2016), a visual artist (working in printmaking, painting, and pastel- and pencil-drawing), and a builder and craftsman—someone for whom rhythm is not just something heard, but also seen and felt. From 2018 to 2024, Martin was also the executive director and president of the nonprofit Creative Music Studio. His expansive creative practice comes most alive at his home in Englewood, New Jersey, where he has cultivated a bamboo garden, crafted his own Japanese-style teahouse, and constructed a music studio. For Martin, each of these pursuits serves as its own form of rhythm.

On the episode, he goes deep into his journey with MMW, discussing the tracks “Shuck It Up” (1993), “The Lover” (1995), “Chubb Sub” (1995), and “Latin Shuffle” (1998), as well as the band’s 1996 album, Shack-man, at length. He also talks about his concept of “rhythmic harmony,” his reverence for bamboo (over the past year or so, he has begun making percussion instruments out of the material), and why he views sound creation as a sacred act.

CHAPTERS

Martin details three tracks from Medeski Martin & Wood’s ’90s catalogue—“Shuck It Up” (1993), “The Lover” (1995), and “Latin Shuffle” (1998)—unpacking some of his wide-ranging influences and rhythmic approaches.

Martin considers harmony—not just as a concept in music, but as a vehicle for living a rich emotional and spiritual life.

Martin discusses how drumming, music, and sound facilitate human connection across cultures, and explores the nuances between time and timing.

Martin, who was raised by a classical violinist father and a Rockette dancer mother, recalls a household thrumming with creativity and music.

Martin looks back on the band’s earliest days and shares how the trio came together to form MMW, reflecting on the improvisational approach that has fueled their decades-long collaboration.

Martin talks about bamboo’s resonance in his work, from growing it in his own backyard garden to crafting instruments with it by hand, and how it serves as both muse and material.

Martin shares his grounding belief in music-making as an intentional act—one that demands consciousness, love, and care.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Billy. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

BILLY MARTIN: Hi, Spencer. It’s so great to be here. I’ve been listening to your show for a long time. I’m honored.

SB: Well, at first, I should say, this episode feels like it’s long overdue. [Laughter]

BM: I’ve been wondering, “Hey, when is he going to give me a call?” No, I—

SB: Because of our friendship, which we’ll probably get to, but also your involvement in composing the theme music for Time Sensitive. In that sense, you’ve been a part of this project from the start. What was your approach to thinking about theme music for a podcast—this podcast—which, by the way, you recently updated. How did you think about composing it, thinking about time, thinking about notions of time, because the show is philosophical—it’s not literally talking about just industrial clock time.

BM: Yeah. Well, I had a lot of ideas. I went all over the place with the possibilities, my whole thing about rhythmic harmony and how time works. But I really wanted to get your direction. When we talked about it, it helped me hone it down to how it would work for you. I really was taking the lead from you. It was like, how do you feel time passing? What does that sound like? Of course, it being a podcast with information coming through the internet, like, okay, maybe there’s some electronic stuff. It was more electronic, working with my Ableton [synthesizer] and adding things. I had a lot of ideas, but it ended up being what it is thanks to your direction, which is, ultimately, what I want to do is get you what you need and what you like.

SB: You recently added some other sounds. Maybe you could talk about this.

BM: Yeah. That was really nice. I felt like, Oh, I’m so glad I’m getting a call to update it, because now I can do some of the things that I felt like, maybe, I couldn’t do then. The bamboo leaves are in there a little bit as a wash. Really, what my initial vision was, was the sound of multiple time-cycling sounds, which is the rhythmic harmony concept. That that’s there, like a veil, at the beginning, all these different bamboos—

SB: Yeah. [Makes chicka-chicka-chicka sound]

BM: —clicking away at their own rates, multiple rates, which I think really represents how the universe is working all the time.

SB: Let’s turn to your drumming. Given that many of our listeners may not be familiar with your work, I thought we could kick off the episode with a Billy Martin primer. [Laughs] We’ll sample some tracks by Medeski Martin & Wood, or MMW. Medeski Martin & Wood is a trio that you formed in 1992 with the keyboard player and composer John Medeski and the bassist Chris Wood. I don’t even want to use terms to describe MMW’s sound—I’d rather listeners just take it in. But from the title of that recent documentary that came out about the three of you, we could say that the music is not not jazz. [Laughs]

BM: Yeah, I think that’s good.

SB: How would you describe the sound? Obviously, this is now, what, three-plus decades of music making? What terms have worked for you in describing the sound of Medeski Martin & Wood?

BM: Well, the best compliment is “uncategorizable”—that it’s another thing that people can’t put into words, which I think is what music can do, art can do. That it’s a personal experience. But with that said, I would say that we definitely can groove our asses off.

SB: [Laughs]

BM: Our rhythmic sensibility is really strong. Also, our experience playing jazz, classical music, these general genres that I’m talking about.

SB: John and Chris came out of the New England Conservatory.

BM: Yeah. And then my experience with growing up listening to R&B and hip-hop as it was being born in my teenage years. I was really tuned in to that because I used to love to go out to clubs and dance and stuff, and D.J.s, listening to what they were doing. It’s really all the things that we love about music combined. Duke Ellington, he always talked about how the music that he was doing is not really a category. I agree because it taps on all the world influences. Of course, there’s a style of jazz dressed in a jazz way. Anybody who’s a rocker is going to say we’re a jazz band, and anybody who’s a hardcore jazz person is going to say we’re a rock band or a funk band. I have no word other than “uncategorizable.”

Some people say “avant-funk” and all that, but no. It’s not always groove, but I think that is the common thing that resonates with people. What really makes us popular is that we groove so well, it’s so compelling, and then all the other things—the harmony and the improvisation is really beautifully colored and expressed in a very personal way.

SB: Well, I like this sort of rock people, jazz people—

BM: Yeah, it’s all perspective.

SB: I actually didn’t know this fact about you and MMW until preparing for this episode, but you guys worked with Iggy Pop.

BM: Yes, we did. Right down the street.

SB: Yeah. And you backed him on his 1999 album, Avenue B?

BM: Yeah, and we played with him in Paris. It was a blast.

SB: What does he make of you guys?

BM: He loves us. He’s great. He’s down. I think Don Was, the producer, introduced him to us. The first time we worked with Iggy was in an old Yiddish theater that was defunct, and it was, like, a place where they were recording in the East Village. Then the second time he came out to do one more thing with us, and that was in our space, which we used to call “Shacklyn,” which was—

SB: In Brooklyn?

BM: Yeah, in Dumbo, in a basement. He loved it. He was like, “Oh, I love this neighborhood.” It was real funky. He’s just really sweet. Actually, I was taken aback by how intelligent he was and how poetic. That was really something. We had a good time while it lasted, that record and doing that one gig in Paris with him and Chrissie Hynde and Vanessa Paradis—and Johnny Depp sat in.

SB: Well, I thought we’d start with the track “The Lover.”

BM: Oh, yeah.

SB: This is from your 1995 album, Friday Afternoon in the Universe. The album title’s taken from the opening sentence of the Jack Kerouac poem “Old Angel Midnight.” Could you speak to this particular track from a rhythm, drumming, and time perspective? It’s the opening song on the album, and it really sets the scene, so to speak. It opens with this really funky cowbell thing going on.

BM: Yeah, I’m riding on the cymbal bell as a shuffle, and then there’s a cowbell that is incorporated there with… So both hands are going and it’s shuffling along, and that sets up the whole feel, the rhythmic feel, for the entire track, and then John comes in with the organ, and the bass, Chris. It’s a very special way that I play that you don’t hear too many people doing, and I think that’s one thing that attracted John and Chris to my playing, was that I could swing, but it wasn’t like a bebop drummer; it was more funky. Maybe you could think about New Orleans and you could think about a lot of other things. It has a swing and lilt to it—a swagger—that is mine, and more than most people would dare to do. It’s definitely a track that defines how I can shuffle, shuffle along. [Laughs] “The Lover,” by the way, is the title of a strain of weed that grows in Hawaii.

SB: Appropriate.

BM: Not the killer weed, the lover weed. [Laughter]

SB: We’ll give the listeners a sample here. [Plays the beginning 40 seconds of “The Lover.”]

It’s not lost to me that Friday Afternoon in the Universe is thirty this year. I wanted to ask what comes to mind for you when thinking about that milestone. What does it mean to you? What did that album mean to you? What’s it mean to you now?

BM: It was a breakthrough for us in taking back our creative expression, because the record before, we had signed a record deal with Gramavision Records, which was a real indie kind of jazz-fusion label. Bob Moses, my mentor, was on it; Jamaaladeen Tacuma from Ornette Coleman, John Scofield; all these great musicians. They were the one label that was interested in signing us. The problem was that the label, the woman who was running it, assigned her husband to produce our record, and we were like, “What? We produce our own music.” The record before that was a bit of a struggle for us. We weren’t really feeling bold enough to say, “Fuck you, we’re doing it our way.”

Friday Afternoon in the Universe was a real breakthrough. We were able to really… Even though the producer was still there, he was in the other room. The engineer friend of ours, David Baker, who took over, said, “Let us just do this. Come in and listen. But don’t tell them what to do. Let’s just capture who they are.” It was a successful record, and it was very exploratory. There were a lot of vignettes in there, there’s a lot of tunes in there. I think it really defined and paved the way for our real beginning.

SB: You guys ended up on Late Night with Conan O’Brien.

BM: [Laughs] Yeah. That’s right, yeah. We were on The Late Show, we were on… Wait, were we on The Late Show? I don’t know.

SB: I just know that it was this very welcome thing for your fans at the time, because they would see you live and you’d sound one way, and then the first two albums sounded maybe a little more conservative, a little less… funk.

BM: Yeah, it definitely didn’t have that energy of, what’s going to happen? It was a little bit more formulated. It sounds more formulated.

SB: For the next track, let’s turn to “Shuck It Up.”

BM: Oh.

SB: This is from the 1993 album It’s a Jungle in Here. That was the album right before Friday Afternoon in the Universe. The New York Times once described your backbeats as “rollicking.”

BM: Oh, interesting.

SB: I’d say that’s certainly the case with this track. Tell me a bit about your drumming here on “Shuck It Up.”

BM: This was definitely another breakthrough for us because the rhythmic sensibility is very sophisticated, the way we play. But this was something we were really expanding on. Basically, what I’m playing on the drums is what I call “polymetric.” I’m playing a New Orleans–style second line swing snare, and the bass drum and the hi-hat are playing in, like, four or three… It’s one of these things where you have duple and triple happening at the same time, which is another part of my rhythmic harmony rap—it’s having these two things married together. They’re combined, and it creates this other thing: harmony.

With that track, it was just very over the bar line playing and rhythm. Chris’s bassline was particularly challenging for him because he had never done anything like that. He would always curse us when he had to play it live. That track is really special. There’s nothing like that. It happens to groove and have this form, and it’s just the perfect blend of the right elements. Really, there’s a polymetric thing going on there; it’s not just like you’re beating to three or four, it’s like you have both in your… You feel it in your body.

SB: Yeah. [Plays the beginning 40 seconds of “Shuck It Up.”]

SB: Now we’ll get to the third track, “Latin Shuffle.” This is from MMW’s 1998 album, Combustication. This one seems to run deep for you. I’m saying this because there’s definitely a Brazilian tinge or some sort of Latin shuffle-y thing going on. Your connection to Brazilian music goes back to your samba classes that you took, at the Drummers Collective in New York, studying with Frankie Malabe. Does that connect to this track at all? What comes to mind for you with the rhythm and the music on this track?

BM: It does tie to Frankie Malabe because with Frankie, I would say, Frankie was an Afro-Caribbean drummer-teacher, congas and things like that. He could teach you the merengue from the Dominican Republic, he could teach you Haitian Vodou drumming, he could teach you Afro-Cuban drumming, and he was Puerto Rican—he could also teach you the different kinds of salsa stuff. What exists both in Brazilian and this Afro-Caribbean music is the rhythms; how, combined, they create the sophisticated feeling of time and the way you can count through it, dance through it. It’s not just one dimension; it’s many dimensions. That’s the first thing that happens.

With “Latin Shuffle,” which is a very generic title, which I thought works—

SB: Which is why I said “Latin shuffle-y.” [Laughs]

BM: That is probably the most popular and most questioned track for me as a drummer that people want to know: How do you do that? From drummers, like, “How do you play that? Show me that beat. What’s happening there?” There are different stages. It goes to three different… It has three chapters, and they evolve out of each other.

SB: And this beautiful solo moment in the middle of the track.

BM: Oh, right. Yeah. There’s a solo that breaks out of all of it. It definitely transitions from one to the next, and it’s a different way of feeling time, but you never lose the sense of the pulse. There’s always the same pulse, but it’s doing different things. I just basically tell the drummers, “Have you not heard Art Blakey, or Dizzy Gillespie playing with the Afro-Cuban drummers?” Because they all did this kind of thing. If you listen to folkloric Afro-Cuban music, especially on the Matanzas side of the island, you’re gonna hear a deep-rooted Yoruban African drumming, and you’re gonna hear how they make those transitions, and sometimes they’re both existing. It’s magic; it’s really beautiful. So it was just my way of doing that.

Having this chemistry, this relationship with John and Chris, it allowed me to do that. John’s a drummer when he plays piano, so we can really get that going on.

SB: Here’s “Latin Shuffle.” [Plays the first 50 seconds of the track “Latin Shuffle.”]

You’ve alluded to it, but present in all of your work is rhythmic harmony. Define that for me. What is rhythmic harmony? Speak about this concept a little bit for all the drummers and non-drummers alike that are listening.

BM: I always try to explain it to anybody no matter where they’re coming from. My definition of rhythmic harmony is two or more things happening at the same time. So, when you experience those things happening together, you experience a feeling, right? It could be visual, it could be… In the sound world, you could be listening to a drone and a baby crying, and you could go, “Wow, I’ve never felt that before,” or, “That’s familiar, but together with that…”

SB: [Laughs] I’m just imagining, “Bzzz, wah!”

BM: Drones can be just a sustaining chord, or two notes, or one note. Really, it goes back to the same fundamental principles of harmony and music, where it’s like you play one note, you play a C, and it vibrates at a certain frequency, and you play an E, and then that frequency blended with that frequency, you’ve got a beginning of a chord and you get a feeling. Of course, there’s the conditioned feeling that we get through learning about music and, “Oh, that’s happy. Oh, when we go to E-flat, that’s sad.” The idea that you’re combining these frequencies, it’s just rhythm cycling, really, is what it is, pulsing, the pulsing of waves. With rhythm, you can have just a downbeat, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, and then you can have something going [voices chick-chicka-chick rhythm]. Then you could play them together.

Drummers are really experiencing the rhythmic harmony more because they’re providing, often, a pulse and an accompanying rhythm, so it’s really counterpoint. But Now my concept of rhythmic harmony is really expanding into more things, where things are not locked in time. One thing is revolving—cycling—at a certain rate that’s not related to the other thing that’s cycling at a certain rate. Now you’re talking about physics and quantum physics in the universe, it’s like… Those things do exist in music, as well. Rhythmic harmony is everywhere. Just when people say “Rhythm is everywhere,” a very cliché thing to say, but…

SB: I was just thinking about the same way a photographer might see something no one else sees. Does that happen to you in the world with this? Are you hearing rhythmic harmony all around you all the time in ways that most people probably aren’t paying attention to, or…?

BM: I don’t know about that.

SB: Or are you walking down the street and you’re like, “Whoa”?

BM: I think I have an obsessive-compulsive thing where I count my steps, sometimes, when I’m going up the stairs, or I’m coiling up something and I’m counting it, and I’m like, “Why am I counting it?” I feel the pulse when walking, and then I hear someone else’s steps, and then all of a sudden I’m hearing that relationship, and I’m like, “That’s cool.”

SB: [Laughs]

BM: I can hear a truck idling and someone talking really fast and go, “That’s kind of cool.”

SB: [Laughs]

BM: I do hear those things, but I don’t have some special perception. I think it’s just an awareness that I—

SB: Yeah, that’s more what I meant, you’ve tuned your ear to be aware.

BM: Yeah, yeah. But I don’t live that every day; it’s not something that I talk about. No, it’s not. Sometimes, it becomes really obvious, it’s like…

SB: This is probably a good point in the interview just to, out of full disclosure, say we’re friends. Most of the time, guests come in and I’m meeting them for the first time—not always, but a lot of the time. I think it’s also worth mentioning that I’ve been listening to MMW for almost thirty years. I remember I was a 12- or 13-year-old, with braces, walked into a Blockbuster Music—which, for those of us who grew up in the nineties know that was a thing, it was trying to compete with Tower Records—and I bought Combustication, which “Latin Shuffle” is on. The guy behind the counter looks at me and he says, “You sure you want this, man? These guys are heavy.” I was just like, “Yeah, sure.” I didn’t really know what I was getting into but, little did I know, that album would go on to change my life and propel me on this decades-long drumming journey, which I’m still fooling around on the drums today.

BM: Were you drumming then, before…?

SB: Yeah. I started drumming right then. Basically, when I bought that album was when I discovered your music.

BM: It was simultaneous.

SB: It was sort of a kismet thing.

BM: Wow. That’s amazing.

SB: I think it’s fair to say that you quickly became my drum hero. Much in the same way that, after reading Jhumpa Lahiri’s book Interpreter of Maladies, she became my literary hero. That happened at 17, so a little bit later.

Fast-forward to almost ten years ago, a now ex-girlfriend of mine beautifully orchestrated our introduction. We’ve since drummed, hung out in your teahouse, which maybe we’ll talk a little bit about. I’m saying all this because, from a time perspective, it’s incredibly heady. Sitting down with you right now feels like this strange full-circle moment from the time I walked into Blockbuster Music and picked up this album. I’ve seen you guys live, I saw you with [John] Scofield at the Barbican in London in 2007 and a couple times here in New York. I just wanted to bring this up because, to me, our connection—yes, now we’re friends, but it actually is rooted in drumming and rhythm. I think this thing with drumming as a communication tool is so powerful.

Maybe could you speak a bit about that, this idea of drumming as a connective tool? Drumming, in some sense, while being about time, or of time, transcends time. What do you think about drumming and its ability or power to bind people together?

BM: The first thing that came to mind before you just asked that very last question was that if you could make the drums speak and resonate with people, that’s your master. I think that’s the goal: to make the drums speak. Even if you’re keeping time, you’re saying something that people are hearing and they’re getting some different feeling from you’re playing. That’s one thing, because you can play the drums in a very cliché way, like any instrument, and get by and read other music and not have a style, but be able to play certain music—and perfectly. the idea that you can make the drums speak literally and figuratively, I think it’s really important, and keeping time. I think it brings people together because everybody, I think, can relate to feeling a sense of pulse and—

SB: Heartbeat.

BM: Yeah, the heartbeat. When you hear something and you relate to the music in a rhythmic way, you’re usually bobbing your head or moving your body or tapping your foot or getting up and dancing, I always tell people that it’s really important to recognize that you have rhythm as a listener—you understand it. A lot of people say, “I don’t have rhythm,” all this stuff, but I think it’s just inherently in human nature—and in nature, period, it’s there. And I can see birds bobbing their heads sometimes. They’re getting into a rhythm.

I have a friend that has a highly autistic kid, and I see him walking around, moving his head, his shoulders when he walks, and he’s feeling something. I don’t know what he’s feeling or hearing, but I think it’s a very rhythmic way. I heard something else about a dancer that was a failure in school and was being evaluated by these academics, and most of them were just writing her off as she’s just not going to be able to really live a good life. Then one person played some music, and she got up and started moving and couldn’t stop dancing, and he said, “This is what she’s going to do.” So this idea that you’re feeling it. It’s a common way to bring people together. You talk about bringing people together. It doesn’t require a lot of thinking or intellectual thought; it’s just, you feel it with your body, and that is very fundamental to being human, is just feeling a pulse, a rhythm.

SB: Well, in the same way one can read a transcendent novel. I think of an album much the same way, and Combustication was that for me.

BM: Yeah. You’re dealing with code when you’re reading.

SB: Yeah. Is there anything else you would share here about your thoughts on drumming from a philosophy-of-time perspective?

BM: There’s two things. The philosophy of time is one half. The other half is the philosophy of expression and nuance and feeling and sound. I think those two things come together, and it’s really important to really be able to see and hear and feel both, that the sound that you’re playing, it’s a choice that you make when you’re playing a rhythm, or not, or you’re maybe playing a long tone or just making some sounds that are not rhythmic. Being a good drummer, I think you need to have both of those things: You need to be able to make sound compelling, or doing what you’re really feeling, like an artist, you have a vision and you’re seeing it through and you’re developing that as a vocabulary.

Philosophy of time is two things. One is the ability to lock and connect with a pulse, and to be able to feel it and to be able to connect with other people and be locked in time together, to be in step with each other, and to also be able to play counterpoint and other parts that are… You’re all feeling the time. It is an eternal feeling of time. You don’t have to bang it out, but the idea that you’re all connected with this time going by, and that frames the form.

There’s also timing. When you play, when you choose to play a certain sound, when you choose to change the form, that’s a different kind of time, that’s like, “When is this going to happen? When am I going to move? When am I going to change? When am I going to change up the rhythm? When I’m going to say something different or say something at all? When am I not going to say anything? When am I not going to play?” It’s all timing. So it’s really two things when people talk about time.

SB: Yeah, presence and absence, too. I’ve had some architects on the show talk about the relationship between light and shadow, and I feel like this connects directly to that.

BM: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. All these things come from life. I’m 61 now, so I can really be… I’m very confident in what all the—where I’m getting my information, it’s not all from just studying drums. It’s expressing myself now in that way and being able to articulate things that I can relate to form and architecture. I have a lesson or a strategy I call “dancing about architecture,” and that is a way for a student to improvise, but framing themselves within a house and going through each room as a movement.

SB: Oh, I love that.

BM: Yeah, in spontaneous composition. They don’t need to know what they’re going to play; they just need to be in the moment and know when to stay in the room, explore it, and then leave the room and go into another room. It’s all tied together by the house.

SB: This reminds me of what you told me the first night we met. It was something along the lines of, “Next time you’re behind the kit, just pretend you’re telling a story.” Drumming is storytelling.

BM: Yeah. Yeah. Maybe I wasn’t… Dancing about architecture, yeah, I think that’s a good one, but I think that’s from Thelonious Monk: “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” So my thing was soloing about architecture, or drumming about architecture. Anyway, I forgot my own strategy. You get the point. [Laughter]

SB: In your 2011 film, Life on Drums, you say this brilliant thing about time and music that I wanted to quote here. You say, “Good musicians with a good sense of time don’t have to imply it; they have it internally. Everyone shares that internal time and pulse. No one has to play banging out the time.”

BM: Absolutely. Yeah. I actually had hinted on that just before. That’s what people have to remember. I’m going speak on this in terms outside of the music. You don’t have to spell it out for everybody to give them the feeling. You don’t have to bang out the time—especially for drummers who are conditioned to do that—just play time so other people can express themselves, keep the groove going. It’s more about feeling the time, and it’s internal, so that you can—it’s a second-nature expression. Like walking, you’re not thinking about it.

SB: Felt time. I like that.

BM: Yeah. Feeling it with your body. Yeah.

SB: Let’s go back to the beginning of all this for you, because it’s remarkable how you came into this earth, your parents, your—

BM: For everybody. Everybody’s remarkable.

SB: Everyone, yes. But your father was a classical violinist, and your mother was a Radio City Rockette, so I would say an extraordinary couple to birth Billy Martin. [Laughs]

BM: Yeah.

SB: What sort of music were you guys listening to in the home?

BM: Well, my mom had me tap dancing at about 5 years old. The stuff that I liked that I was dancing to was Count Basie and Duke Ellington and Sly Stone and some New Orleans stuff. My dad was… We would travel every summer up to the New York City Ballet in Saratoga and spend the summer there, so I was running around, playing around the Saratoga Performing Arts Center while they were rehearsing. He would take me to rehearsals and things, so I heard a lot of Russian composers: Tchaikovsky; Prokofiev; Aaron Copland, as well; Stravinsky, Russian composer; Copland’s American, but… He would play music also at home and I would hear a lot of classical music, and I loved it all. My brothers, who are really a decade, a generation older, they had the Woodstock record, they had Elton John, they had The Allman Brothers, they had James Brown and Frank Zappa and Lou Reed. That stuff was also very formative for me.

When I got into the drums, that’s where playing along with records was happening, with my brother’s records. But the rhythm started with my mom, with the tap dancing.

SB: Do you remember the first time you were sitting behind a kit?

BM: Yeah, I do. Actually, we still lived in New York. My brother Kenny, he’s the middle one, was the drummer. He was taking some lessons. So I was very young, to the point where if you sat me on the drum stool, my feet were just dangling. [Laughter] He sat me on the drums and he crossed my right hand over my left, the right hand was hitting the hi-hat, the left hand was hitting the snare, and he just [makes drumming sound]… That was the beat, that’s the beat that I play all the time, thanks to my brother Kenny, rest in peace. He taught me that beat. That was the first time I ever experienced a drum set.

SB: Who were some of the drummers that were important to you growing up?

BM: I think the first drummers were probably the bands The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, so John Bonham—

SB: Charlie Watts.

BM: Charlie Watts. Then Stewart Copeland, later, was really a big influence on me because the way he swang—swang, the way he could shuffle and things like that were very different, and also rooted in not only reggae music with The Police, but also, for Stuart, was his experience with Arabic music and Middle Eastern [music]. I think his father [Miles Copeland Jr.] was in the C.I.A., and he lived in the Middle East, and he heard music there that was really informing his playing. I could just hear all that. I was really into world music, too, what they called “world music.”

SB: Air quotes.

BM: Yeah, exactly. Folkloric music, really, right?

SB: Mm-hmm.

BM: Then it was Elvin Jones; Max Roach; Danny Richmond, who played with Mingus; Jack DeJohnette; the list goes on.

SB: Laundry list. Joe Morello, I’m sure.

BM: I studied with Joe Morello, yeah. Roy Haynes. My dad played with Roy Haynes on Focus, the Stan Getz record, he played strings. There are just so many, and not just drummers, but percussionists, like Airto [Moreira], and Naná Vasconcelos, and [Babatunde] Olatunji, and—

SB: I wanted to ask you about Gus Johnson because there’s that track “Whatever Happened to Gus” on Combustication.

BM: I didn’t know anything about Gus until Steve Cannon, the poet, did his spoken word, and he had a dream about Gus Johnson. iIt turns out that Gus Johnson was one of the drummers that played with Charlie Parker, but that wasn’t really celebrated. Steve Cannon knew about Gus Johnson, I guess, and it crossed his dream and he turned it into a poem. You know what’s interesting is that Gus Johnson’s son reached out to me and said, “Man, thank you so much for putting that track on. My dad… It’s so nice to hear him get some credit.”

SB: Yeah. When I was looking at his history, he passed away just a couple years after Combustication came out.

BM: Wow. I wonder if he’d heard it. What a wild story. Steve Cannon is just amazing, creative, literary genius.

SB: I feel like we have to talk Bob Moses here, who was this incredible influence, and who introduced the three of you, right?

BM: Yeah, he did. He was the messenger.

SB: How Medeski Martin & Wood came to be was through Bob Moses.

BM: Yeah, absolutely, because Bob talked about Medeski a lot. When I used to hang out with Bob—he taught at New England Conservatory in Boston, and John was there, Chris was there, and then they had even played together as a trio and with another saxophone player. I would hear about these stories. Bob is an incredible storyteller. I would always hear about certain students that he was just like, “Man, you got to hear this Medeski guy on a piano, he’s amazing.” I’m like, “Who is this Medeski guy he was talking about?” He was planting seeds. I think he probably talked to them about me. Then I met John in Boston, playing on a Bob Moses gig with his big band, Mozamba, and that’s where we met.

SB: Then you get John and Chris into the studio in Brooklyn, right?

BM: Well, yeah, I invite them. Well, the first thing is when I met John in Boston, he came backstage and introduced himself. I’m like, “Oh, wow. I heard a lot about you. Let’s play.” He said, “Yeah, well, when I come down…” I said, “When you come down to Brooklyn, let me know and let’s just come over to my place.” I had a place in Dumbo. I was living in a warehouse in Dumbo in the late eighties into the early nineties. This was around ’90, ’91 that John and I got to get… I picked him up in my van—he was staying at a friend’s house in Brooklyn—took him to my space in Dumbo, and I had a drum booth, and we just played duos for two hours, and we went everywhere. We were even speaking in tongues, we were using our voice, and it was really pushing each other across the envelope of… It was wonderful. He was like, “Look, I got this bass player. He’s coming down. I think he’s really good.” Then I invited him.

I had a little bit of recording gear, not anything fancy. That was the first thing that we played. The first notes we played together when the three of us got together was “Chubb Sub.”

SB: Oh, the song that became “Chubb Sub.”

BM: “Uncle Chubb,” “Chubb Sub.”

SB: I feel like we should play that right now. Let’s do a little… We’re going to do a little sample.

BM: Yeah, because it was literally the very first thing we played, spontaneously improvised, like, “That’s it!” John transcribed it and added horns later.

SB: We’re going to give a little listen. [Plays first 50 seconds of “Chubb Sub,” from the 1995 album Friday Afternoon in the Universe.]

I can only imagine what it was like to have that. You talk a lot about chemistry when it comes to music, and I can imagine the chemistry that just exploded in the room at that moment.

BM: It was an incredible feeling. I was so overwhelmed with joy and love for these guys. It really felt like, Oh, these are my brothers, right away. I think we all had the same feeling of, Man, they understand, and they’ve given me as much space as I would give them, and we’re really collaboratively equal and there’s no hierarchy. Even though I was so blown away by John’s playing, I was like, I was already like, “This is a band. Let’s call it the John Medeski Trio.” John was like, “No, no, no, no, I’m not…” He said, “We have to find a band name.” The feeling was incredible.

I was already aware of how important chemistry is between players and characters, but that was a real testament to, man, do we have just somehow…? Everything fits, everything works, just how we play and how we communicate, it’s unspoken. Of course, we did discuss things, but it was just so natural, and that’s just rare. I think that’s what makes a band special, is the chemistry. The real important bands that we recognize as bands, whether it’s The Rolling Stones or…

SB: I think it goes back to that “felt time” thing we were talking about earlier, where there’s just… You feel it. You know it in your bones; something’s occurring.

BM: Yeah, yeah, understanding something that’s abstract and just feeling it and relating to it.

SB: Improv connects to this, and improvisation is so much a part of your practice and life philosophy, I would say. You’ve said, “For me, improvisation is my way of life. I could not survive without it.”

BM: It is. [Laughter] I have no choice, really, so… I have to say that. We all improvise. [Laughter] That’s the thing. When I teach improvisation, I really try to go beyond the instruments, the music, and explain that we’re all improvising, and that if you get a chance to exercise that part of your expression and use it, you’re going to just be able to navigate your way through difficult times, as well as good times, and making decisions. I think it’s really important, improvisation. It needs to be in schools.

SB: We already touched on MMW’s second and third albums earlier, but I also wanted to bring up the fourth, Shack-man, from 1996, which seemed to be even more of a pivotal moment, I would say, than Friday Afternoon in the Universe.

BM: Absolutely.

SB: In some respects, or many respects—or in its entirety. This album was recorded in a solar-paneled plywood shack on Hawaii’s Big Island.

BM: That is true.

SB: How did you end up in this solar-powered shack? And could you talk about “shack time”? [Laughs] How did shack time impact the three of you?

BM: Again, thanks to Bob Moses, Ra-Kalam Bob Moses is his new… Well, not that new, but he goes by Ra-Kalam Bob Moses. When I went to Hawaii with Bob Moses, before I met John and Chris, he invited me… Well, he introduced me to Carl Green, who owns the shack and built the shack and lived in the shack in the seventies. After he went to the University of Hawaii there, in Honolulu, he moved to the Big Island. So I met Carl in my parents’ house in the basement when Ra-Kalam Bob Moses and I were recording Drumming Birds, a duo record. My dad had recording equipment, and I had stuff there, and so he introduced me.

Thanks to Bob Moses, I had already been introduced to Hawaii and Carl, and so when I met John and Chris, I was like, “You guys have got to come to Hawaii. We’ve got to hang out there. We’ve got to find a way.” The first time we went, we didn’t even go to the shack. When we made Shack-man, we had already been spending a couple of years there, maybe—in the winters, usually, in January, when no one’s touring, it’s cold, it’s miserable. We would just go to Hawaii. My friend Carl said, “I have this shack I rent it out, and it’s three hundred bucks a month.” We were like, “Well, let’s check that out.” Then after that, we decided, each of us, to pay the rent through the year, just to have it for a month or two, and also just to offer it to friends that might be passing through Hawaii and then they could stay there.

It was a place where we recorded. We hung out, we lived together, we had a vacation together, and they had instruments there. Carl had his drum set there, he had an upright piano there, some amps. We started accumulating gear that whenever we went to Hawaii, it was there. Then I started recording with a DAT tape player and some really good mics, I started recording our jams. A lot of writing was done there just by playing together every night. Then we decided, “Let’s record. This room sounds great.” We knew it sounded good in there; there was something about the instruments and being in the jungle. There was no traffic, it was dirt roads and there was no electricity, there was no plumbing, it was literally—

SB: Off-grid.

BM: In an off-grid place.

SB: Well, I asked about shack time because I knew there was more to this story and that it wasn’t just like you guys landed and started recording in this shack studio. There was a backstory.

BM: It started as just a place for us to go and hang out. Since we were touring a lot together, we started to do things together and started to have… Like, “Hey, let’s go hang out in this place.”

SB: It’s interesting how this off-time, or this winter tropical time, in some sense, led to this album.

BM: Yeah. Definitely. We wanted to capture the magic of playing there. Nowhere else could we quite be that comfortable, or just the solitude of a place, like an artist-in-residence kind of thing.

SB: There’s a sort of rawness to that record, too.

BM: Absolutely. Yeah.

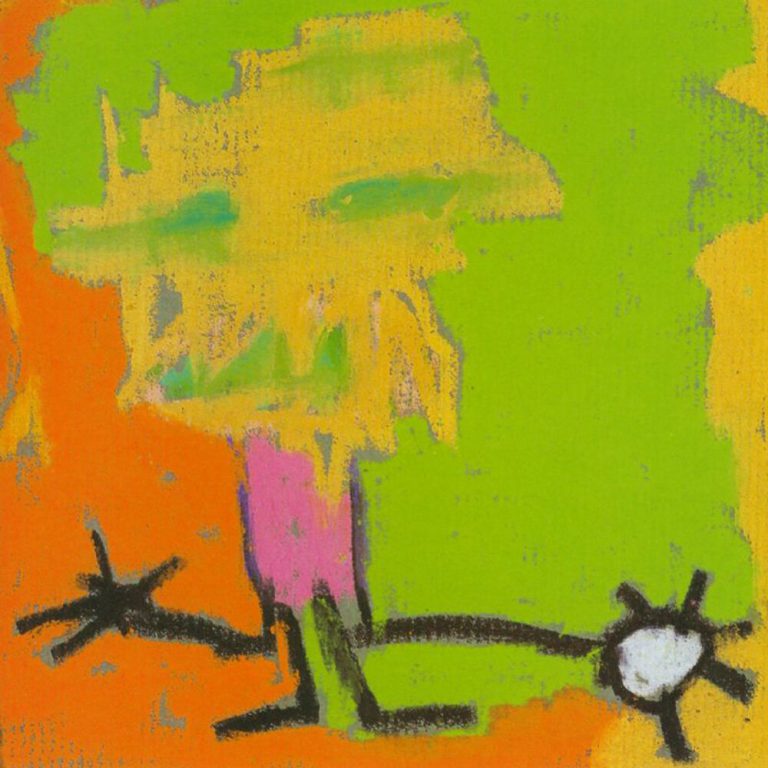

SB: Beautiful rawness, which, by the way, you did the album cover for, too—the art.

BM: I did. Yeah

SB: The visual art.

BM: Yeah, under candlelight. So it was interesting how the colors came out like that, because if I had light, a bright light, I wouldn’t have chosen those colors. What’s interesting is they’re very fluorescent colors.

SB: It feels very Hawaii, very kind of—

BM: Yeah. It was really interesting, the result of that. Then John loved it because he was like, “I don’t really like the image, something about it,” but he was like, “It’s the exact same size as a CD cover.” He said, “That’ll fit right and we don’t have to change it.” For some reason, he was really attached to that idea. So I was like, “Fine.”

But just a little bit more shack time is that, well, the story of recording there was really interesting because John was really nervous about recording there because he wasn’t necessarily so comfortable that, what if the keyboards don’t work? He doesn’t want to compromise, he wants to have a Hammond B3 there, he wants to have a Leslie speaker, he wants to have certain amps and certain mics, and it’s not a studio, and how are we going to do that? I was very much “On-location recording, I don’t care so much about fidelity or the kind of thing…” They’re just capturing how we play. But he was more like, “I want to make sure that I have what I need because I do express myself on the Hammond B3 a lot now, and I’ve got to have the power, and that thing’s got to be spinning, and I’ve gotta be able to use the draw bars.” I understood that.

David Baker had been with us from the beginning—he recorded our very first record—another mentor of mine, and somebody, through Bob Moses again, I met. David, he’s an on-location recorder of jazz-chamber music, jazz music—in other words, it’s not like you’re tracking, you’re just recording the band wherever they are. He brought two eight-track DA-88s, they’re multitrack things, and you join them together so you get sixteen tracks. He brought those over, a Mackie board. Some people are going to know what this is and [some] not, but it’s just basically the bare essentials to record, and his mics, and—

SB: Raw.

BM: Yeah, raw. Carl, in the meantime, knew a doctor who owned a Hammond B3 that he didn’t really play that much, but he had it, and he got that guy to lend it to us. Getting it in the jungle and all this in a pickup truck and all was crazy.

SB: It’s like a Werner Herzog movie.

BM: Yeah. The other thing is to convince our label. At the time, Rykodisc bought Gramavision. There was an advanced budget. We basically were like, “We’re going to use the budget to make the record.” It was too small for us to record, for John Abel’s keyboard, so they renovated the shack. Carl and his friend there, we gave them money to buy lumber and build it out a little bit. So we got there, they’re building the shack, we’re getting this [Hammond B3] from a doctor. We called him the “organ donor,” being a doctor.

SB: [Laughs]

BM: We put it all together, we turn on the power, only one of the units works, so now we’re down to eight tracks—eight tracks to record this record.

We didn’t tell the record label that we’re having problems. We just told them, “We have sixteen tracks, we’ll be fine.” They were very nervous. They did not trust us. They were very much like, “I don’t know how you’re going to do this.”

SB: Little did they know you’re doing a home renovation. [Laughs]

BM: At the same time, as we’re recording, the ants are finding the electricity. Ants are attracted to electricity, and sometimes they’ll come together and they will create a short: They’ll all connect from the negative and the positive poles because they’re attracted to it. They destroyed that thing, and they destroyed the DAT machine. Oh, no, the DAT machine didn’t get destroyed—we could see the ants crawling through the meter. We were like, “Oh, my God, this is crazy.” John was starting to have anxiety attacks about it.

We got the record done, and the record came out. Rolling Stone did this really good review. That was a huge breakthrough for us. It was such a defining moment that we could do this—we could do anything.

SB: Shortly after that, you were signed to Blue Note, from 1998 to 2005. Selling a few hundred thousand copies of these albums, which is practically unheard of for groups in that—

BM: Instrumental groups.

SB: Yeah, instrumental groups. Well, maybe this is a good moment to turn to Bamboo.

BM: Oh, yeah.

SB: We haven’t talked about it yet.

BM: That’s right.

SB: I feel like that’s an important—

BM: Bamboo is my teacher.

SB: I love that phrase. Back in 1999, you released this hour-long track called “Bamboo Rainsticks,” which, for the hour before recording this episode, I was listening to, and so starting this in a kind of meditative state today. [Laughs] I know bamboo has been this long interest of yours. The teahouse I alluded to earlier sits right next to this mini bamboo forest in your backyard in New Jersey. You recently started designing bamboo instruments, one of which is sitting on the table right in front of you. Tell me about your bamboo fascination, walk us through bamboo and time and instrument-making and material.

BM: Going way back to the bamboo rainsticks, I wasn’t really aware of bamboo, how it grows, where it grew, it seemed like an exotic plant to me. In the eighties, I bought a rainstick in SoHo, on Thompson Street; there was a place called Mbira, which is one of the many words for the African kalimba. This store had really beautiful instruments from Brazil and Africa and things like that, and they had a rainstick that was from the Amazon. I just fell in love with it—that, and a talking drum. I was just like, “I’ve got to have these instruments.”

The rainstick was with me for a while. I was using it; I loved it. At a certain point, much later, in ’95 or something, I started a label, Amulet Records, my own label, to really produce my own percussion music at first, and then it expanded into any music. I think the second record was… I had the idea to make a record of bamboo rainsticks, just a very minimal record where it could help people relax.

SB: It’s therapeutic.

BM: When I was living in Dumbo, my girlfriend was like, “That makes me just want to pee.”

SB: [Laughs]

BM: So I was like, “Oh, maybe you’re right.” But in general, it doesn’t.

SB: Earlier, when I was listening to it, I forgot my sense of time. It was like there’s something quite hypnotic in there.

BM: A lot of rhythmic harmony going on there, a lot of simultaneous sound, so much that you let go. That’s the “Wall of Sound” concept, or listening to rain or wind.

SB: It’s like when people tell you, “Be like water,” it’s sort of like that feeling.

BM: Yeah, for sure. Water has always been the sound of—all types of water, whether it’s a brook or the ocean or rain, waterfalls, I would listen to those recordings, environmental recordings. I asked my friend David Baker, once again, “Hey, I’ve got this concept. I want to record a multitrack ‘Bamboo Rainsticks’ song. Each one is an hour long, and I’m going to do multiple takes.” I did eight takes of one-hour bamboo rainsticks, and then we mixed it, and I put it out. My father photographed the bamboo rainstick.

SB: Oh, for the cover?

BM: Yeah. He was always helping with MMW and everything. He was a really key player with photographs and—

SB: He photographed you guys on your second album, too.

BM: Yep. That was really the first experience with a bamboo instrument. I wasn’t aware of bamboo until Phaedra and I, who was—

SB: Your wife.

BM: Yeah, my wife. We were just still dating when we moved to a place in Boerum Hill. We were on the second floor, and I would look out the window and you could see the tiny little yard. The perimeter of it was this really tall bamboo that went beyond the second floor. When I looked out, I saw these green… Through the winter, it was green. I’m like, “What is this evergreen plant?” I found out it was bamboo—it had been planted by the owner.

Then we got married, and we moved to Englewood, New Jersey, and I immediately looked for bamboo. I also had a vegetable garden. I wanted to grow things. The bamboo, it was really just for aesthetic purposes, and also my love of Japanese aesthetics and culture. Bamboo was always… A lot of it was in there, you’d just see it. So I wanted that, not only as a plant that grows outside, but also as a material that they use to build all kinds of implements and screens and things like that. It just grew and grew.

Not until the past maybe five years, I started experimenting a little bit with using the bamboo for… I would cut them into sections, the tubes, and I would play them like a marimba or xylophone and a balafon or gamelan—because there is a bamboo gamelan in Indonesia, as well as brass gamelan, or metal gamelan—and that just grew and grew. Then, last year, around this time, I ended up in the psych ward in Englewood. I had a “breakthrough,” is what Phaedra calls it.

SB: Right. Not a breakdown, a breakthrough.

BM: Not a breakdown, a breakthrough.

SB: I like that.

BM: I was extremely anxious. I had turned 60 the year before, late in the year, and I was just going through a dark passage of the soul. I wasn’t happy running a nonprofit [Creative Music Studio] as an administrator, really. I was an executive director, and I was not built for it, even though I did it for five years and I think I did a pretty good job of building an awareness.

I had reached the point of—I was really losing all of my creative energy. I was really lacking the energy to create because I was so worried about keeping the nonprofit going for a good cause. Creative Music Studio is a wonderful legacy. I was losing my dad. A little bit of dementia, and he was starting to lose interest in all the things that he did, so many things—I learned so much from him. And just Covid. All these things.

SB: Yeah. A confluence.

BM: Yeah. It was a perfect storm of questions and anxiety. I stopped eating and I stopped sleeping, and that put me in the hospital. When I got out of the hospital, I recovered, and after about a month of resting, mostly in the teahouse, in the daytime, I would take from one- to three-hour naps in the teahouse, and it was this time of year, spring, so it was warmer.

I woke up sometime in April out of a nap, and I looked at the bamboo grove that I planted twenty years ago, and it was like a revelation. It was speaking to me. Literally, I could hear it speaking to me, saying, “We’re here for you.” I don’t know how to explain the feeling I had. Then this epiphany of, “I’m going to take care of the bamboo. I’m going to start cleaning it up, I’m going to start pruning it…” Because actually, one of my catastrophic thoughts before I went to the hospital was that the bamboo’s taking over and it’s going to cost an arm and a leg to remove it and it’s going to destroy the house, and all these illogical thoughts I had. It literally became a monster. When I woke up from this nap, it was the opposite, it was like, “We’re here.” It was like—

SB: Iterative.

BM: Yeah.

SB: Improv.

BM: Yeah. I started basically just going around and cleaning up and looking at the bamboo, and cutting it out in certain places that it was moving into where I didn’t want it to go. I started looking at it and started saying, “It’s the most beautiful thing. It’s like it’s resonating with me, speaking with me.” I was like, “Let me make some instruments.” Now I have all the time in the world. Everybody told me, at the different jobs that I had, which were quite a few—New School and Creative Music Studio and all these things, and canceling a tour—everybody was like, “Take as much time as you need. We got you covered. Don’t worry.” I was like, “Man, I have all this freedom. I’m liberated. I’m going to follow that message. I’m going to work with the bamboo.”

One of the first things I did was the opposite of what a drummer would do: “How do you make a flute?” I went onto YouTube and the first video I saw was a guy with a pocket knife. He cut the bamboo into a section and, with a pocket knife, he made a little angle hole on it, the fipple part, which is where the wind blows through, and how to just simply put a piece of wood in there and make the wind hit it a certain way. I did that, and it was like a miracle. I started to hear this beautiful tone from the bamboo. It was an overwhelming feeling of joy and connection with sound and bamboo: I’m making an instrument! I’m making a flute! Because, being a composer, I’m using a lot of melodic instruments when I write, even though I don’t play them regularly, I have them around. That was a beautiful experience.

Then I started really inventing instruments. I was really excited about: How can I activate the sound of the bamboo? What does it want to sound like? I would look at a piece of bamboo, and I’d say, “I think that wants to be a shaker or percussion instrument.” I would collect certain different grades of gravel and rocks, and then I would put them in the bamboo. Each piece of bamboo has its own personality, is totally different. So I would make shakers. I started making knockers, things where I was like, “Oh, I saw this angklung in Thailand and Vietnam.” Then I was like, “I can’t make an angklung, I’m going to make my own thing that maybe will knock the bamboo.”

SB: Why don’t you play this so the listeners can hear what this sounds like? Or maybe just describe this instrument.

BM: Yeah. Well, so this instrument was inspired by a Japanese… Near a temple, they were selling these little instruments, like noisemakers. You wiggle this thing, and the little balls knock and hit the bamboo in your hand. [Makes chicka-chicka sound]

This is a bamboo tube. It has a hollowed-out part, just part of it is open, like a window, a long window, and then there’s two dowels that are holding these rings of bamboo that are also sections of the bamboo—I call them “nodes.” Then there are two other dowels that are holding larger root balls from a tree that fell in my yard, and those are the knockers, as well as the… These are the rings, and these are the knockers. When I shake it [shakes bamboo instrument], that’s everything together, just one… Now, if, with my hand, I hold the balls from moving, you’re going to only hear the rings.

The balls, when I let them go, you can hear them making an accent. What I decided to talk to you about is not only is this an instrument that has never been— This is an invention; this doesn’t belong to any culture.

SB: [Laughs]

BM: That’s what I love about what I’m doing, is that I’m literally taking the cues from the bamboo: The bamboo is teaching me. Not only is it teaching me how to make something new, a new sound, but it’s also teaching me a technique that I didn’t even know… Now I can subdivide rhythms, in a way. [Plays bamboo instrument] This is a teacher of rhythm. I’m subdividing by the accents. This is just time passing by, pulse. What I’m doing is subdividing. Whenever I let my hand go… [Continues playing bamboo instrument] It’s a feel thing. Bamboo is my teacher, not only teaching me how to make an instrument, but also teaching me how to play an instrument.

In my bamboo workshops—which I invite people who are not just musicians, but people who want to just make sound with us—they’re learning, and they’re also teaching us how they play it. Then we have a discovery together, collective discovery, of how to approach these instruments. They’re going to pick it up, and you don’t explain to them anything about it; they just start shaking it, and we have these discoveries together. A lot of the instruments that I build have that message.

SB: I want to bring up the teahouse. I feel like we have to talk about the teahouse before we finish. You built this place—designed it, too, right?

BM: Yes.

SB: Obviously, it’s rooted in Japanese teahouse designs. I think there’s this whole craft element to your life and work that maybe we haven’t touched on. I don’t want to get cheesy and talk about the craft of drumming, necessarily, although I do think rhythm and drumming connect to making. Yeah, just share a little bit about this teahouse and what, for you, it fulfills in your creative practice.

BM: I’ve always been involved with engineering and building things with—watching my dad. My dad, when I was very young, he was always encouraging us to D.I.Y., do it yourself: “Okay, we’re going to make holiday cards, so here are some Sharpies and here are some index cards…” That was a huge inspiration for me. Then he would be building electronic devices. He would work with Radio Shack or Heathkits, you would call them… He was just such an engineer and such a productive person and interested in technology and microscopes, cameras, computers—he had the first computers, he had the first calculator, he had the first… He was fixing things all the time. He was more of a mechanical engineer. He wasn’t a carpenter.

I had a best friend that I met in New Jersey, and he was a carpenter and we were in woodshop together, and that was the beginning of me working with wood and crafts. Then my first girlfriend in high school, her dad was a Norwegian carpenter, and so I would work with him in the summers. I learned from him; I learned from my best friend. When I moved to Dumbo, we built a deck, we built a drum booth, I was his assistant on jobs when I needed some work. I had a little bit of this, “I could do this myself.”

When I moved to Englewood with Phaedra, the only thing on the backyard was a tool shed—a shitty little tool shed—that was just plywood, no interior walls, just the exterior wall with two-by-fours and two open doors you walk in, and there’s your shovel, there’s dirt, and stuff for gardening, landscaping. I was like, “I want to do something with this. I want to build something.”

I just love tatami rooms and Japanese architecture and the teahouse. Going back to David Baker: David Baker was married to Kyoko Baker. She was, actually, a famous costume designer in Japan. When I met her, and I expressed how much I loved Japanese architecture, the traditional spaces, she gave me six volumes of The Tea House magazine. Then they gave me another book, Japanese Architecture, on how to build the old-style homes, the timber-frame homes with the joinery and everything.

Then eventually, I got my shed, and I cut out the doors, I cut out a window in it, I made it lighter, and then I put wheels on it, and I rolled it way to the backyard, because my yard is long, it goes three-hundred-plus feet back, where I plant the bamboo. Then I raised it up. I built everything. I built the sliding doors, the sliding windows, the shoji screens, I put the tatami mats in, I framed everything out, it’s all cedar inside. It’s not traditional in the sense that it’s plaster mud, but it’s very close, it has a tokonoma, it has an engawa, the humble door that you come through, and—

SB: It’s not Home Depot vibes.

BM: No. Right. Yeah. [Laughs]

SB: This is wabi.

BM: Yeah, I’m using Japanese tools and learning about this process of building a private space that is intermediate between nature and an internal, solitudinal space that is free of the news—a space that is really peaceful.

SB: Yeah, it’s telling that that’s where you woke up from a nap and thought to start making bamboo instruments. You also built and created the Herman House, this music-making space, which is now your drum studio, which sits in between the teahouse and the house where Phaedra and you live.

BM: The Herman House is named after Alan Herman, my first drum teacher, who’s in Life on Drums as my co-host. Alan and I were really getting into the idea of education. He was really inspired by the direction I took as a creative improviser and composer. I told him I wanted to build this classroom, this black-box space that could be used, like a soundstage, not just for a drum studio, but for a recording studio, a gallery, exhibits, performances, classes and workshops. He put a down payment for me. He said, “Well, if you can raise enough money, I’ll pay for the foundation, whatever.” I did a Kickstarter, and then I ended up…

So I hired someone to do the foundation, which is just a concrete slab, and then I built off of that, designed it myself. It’s just a giant modern shed, but it’s an incredible space. It’s my recording studio, my soundstage, I project films in there, I’ve been working on a soundtrack there now. It’s also my craft workshop that I built, it’s like—

SB: Yeah, the drumming and the craft have collided.

BM: Totally. It’s all coming from the same place, and I think that’s what’s really important. People say, “I don’t know if I want to invest in just being a musician,” or, “I don’t think I’ll be able to make a living.”

SB: It’s handwork.

BM: Yeah. I’m like, “You can create with any material. You just have to start somewhere.”

SB: To finish, there’s a quote I wanted to end on. You’ve said, “I hold all of my sounds sacred.” That really resonates with me. This idea of the sacred is something I feel strongly about. I think of interviews as a sacred act, and it sounds like you think of sound as a sacred act. Could you talk about that notion of the sacred as it relates to sound?

BM: When I speak about sound being sacred, or expressing or playing your instrument in a sacred way, it’s really directed towards someone who needs to hear it, especially when they’re learning to improvise and they’re developing their voice. It’s not a casual act; it’s a sacred act. If you give it that weight and love of what you’re doing, I think the intention is going to sing and you’re going to have better results. Otherwise, if you’re just practicing your scales and watching TV at the same time, or whatever, or thinking about something and just doing the motions, whatever it is that you do—whether it’s paradiddles, stick control—that’s a technical exercise, and I understand that can be a little mundane, but there’s a certain point when you’ve got to get out of the technique and you’ve got to get into the performance of playing your instrument.

When you practice, you pick it up, and there’s a certain reverence just for the material, the shape, the form of it, the sound of it, how it looks, and it’s all a sacred act. When you make a sound, put your heart into it. Even when you’re alone, I think you have an audience.

SB: Let’s end there, Billy. Thank you so much.

BM: Thank you. Thank you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on March 26, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, Kylie McConville, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Elizabeth Penta.