Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

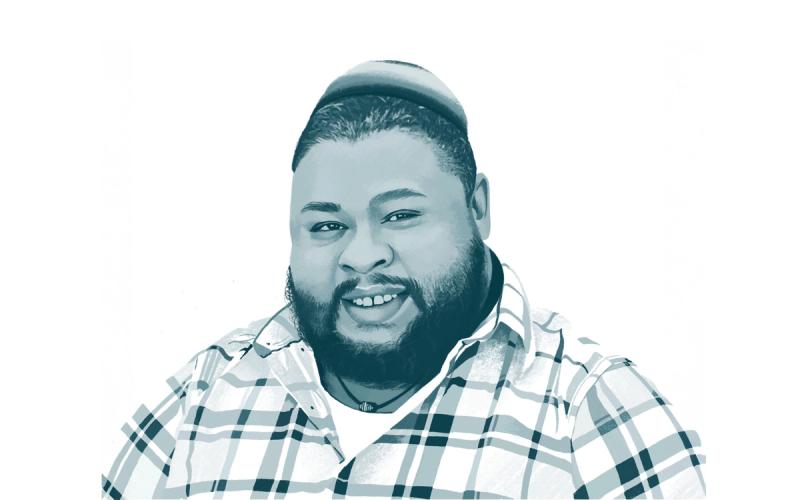

Alfredo Jaar. (© Jee Eun Esther Jang, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

ANDREW ZUCKERMAN: Welcome, Alfredo. It’s a pleasure to have you here in the studio.

ALFREDO JAAR: My pleasure.

AZ: You’ve said before, “I cannot act in the world before understanding the world.” And I want to spend time today talking about how and why your work helps you to make sense of the world.

I think a good place to start is, in March 2020, you made a work called “Manu,” in homage to Manu Dibango, and it was made at the very beginning of lockdown. I mean, we all remember the directionless panic of that moment. What was that work about, and how did making the work help you process that specific moment in time?

AJ: The lockdown started and I was at a loss because, as an architect that makes art, for me, context is everything. And suddenly I was stuck at home—I couldn’t move. So the only tools I had was internet and TV. And, as you remember, the pandemic really hit New York [hard] at the beginning. It was really, really tough. It was scary. I was at a complete loss and I didn’t know what to do. And then, I’ve been collecting contemporary African music for thirty years, and I read that Manu had died of Covid. I thought, I’ll make an homage to him, as a way to speak about Covid, almost as a kind of marker. This is happen[ing] right now, and Manu is one of the first victims.

So that’s what I did. I played one of my favorite songs. I told the story of the song, and I connected to that moment we were going through. I gave some numbers, some figures that looked ridiculous a few months later, because they kept going up and up and up. And so, that was the logic of that work. I really did it for myself, as a kind of therapy. I didn’t show it in a gallery or anything like that. I sent it to a few friends, then a museum [Maxxi] in Rome invited me to submit something. I sent them that video, and then it started circulating, but it was really…. I’ve always looked for music as a refuge. And of course, one of the things I was doing the most during the lockdown at home was listening to music. So it was quite logical, in the face of the loss of this extraordinary musician, to do something about him and with music.

A still from Jaar’s film project “Between the Heavens and Me” (2020). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

AZ: Then you made another work very shortly after, another work about Covid, in 2020, called “Between The Heavens And Me,” where you use silence, actually, and you slow the speed of what we’re watching. And it gave—I remember when I saw the work—this opportunity to look deeply at something that we hadn’t really confronted, making visible a reality that was almost impossible to understand at the time, of course, about the mass graves at Hart Island in New York City. So I’m curious how those two pieces are connected and how you came to make that, and how that started to evolve the way you were understanding the moment.

AJ: Just a month later, after releasing “Manu,” I was watching the BBC. I tend to watch a lot of foreign news. I watch everything. I’m very curious. I’m interested in how news circulates, and different points of view, and so on, in different languages. So I was watching the BBC and I see these scenes about Hart Island. And I learned something that I had never heard before about this island, where there are a million New Yorkers buried there. People with no next of kin, AIDS, death, unknown people—and that’s where they were burying poor people that had just died of Covid.

Aerial view of Hart Island. (Photo: Bjoertvedt)

And I was shocked. I had no idea we had mass graves, a few miles from my home. I had no idea. And so, an immense sadness invaded me, sadness and outrage. I looked at these images, and I couldn’t believe it. So I looked at them for a few days and I started researching, and I discovered that what we were looking at were Rikers Island’s inmates that were burying the poor that had died of Covid, in New York City.

AJ: For six dollars a day. I couldn’t believe it. And I thought, I have to do something. I wanted to show these images to people. I wanted them to see them, and I thought, I’m going to use this strategy of repetition. I want to show that footage once, twice, three times, at normal speed. I want to slow it down. I want people to see. I want this information to enter their beings.

Of course, I thought again about music, and I started looking at my collection again. I have a lot of music that is extremely sad and joyful at the same time, that communicates hope but at the same time is reflecting on tragedy. Music can do that without words, that’s the magic and the power of music. And also, music has this healing power. I remembered Trump talking about “shithole countries,” and I thought, Well, I’m going to use the music of “shithole countries,” according to Trump, to dignify this death of New York.

“I thought, Well, I’m going to use the music of ‘shithole countries,’ according to Trump, to dignify this death of New York.”

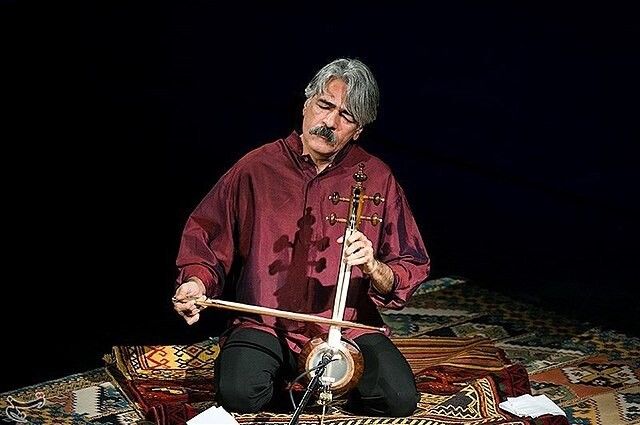

And so, I went first to the music of the enemy number one of this country, which is Iran, and I used the music of one of the most extraordinary musicians that you will ever hear, Kayhan Kalhor. I used his most melancholic, powerful song, which is called “Between the Heavens and Me,” and I played it on top of that scene of Hart Island.

AZ: It’s an oud.

AJ: Yes.

AZ: Yeah, which is a very particular sound.

Iranian musician Kayhan Kalhor. (Photo: Mohammed Delkesh)

AJ: Absolutely. And I thought, This is one plus one is not two. One plus one will make it three, will make it four, will make it five. Then I thought, Well, I’m going to play you another song. Let’s look at this scene again with another song, coming from Greece. So I did the exercise three times, with different music, forcing you to see it with different eyes and with the sound complicating matters, because that sound, of course, will make you see differently.

And that’s what I did. I ended up giving the numbers again, the Covid numbers that now look ridiculous, but at the time, were pretty high and pretty scary. I gave the numbers only for New York, and then for those three countries—Tunisia, Iran, and Greece—[of] which music had participated in the video.

AZ: And you were speaking, on some level, about immigration. You were speaking, on some level, about nationalism.

AJ: I was speaking about many, many things. I was mixing things up. But I really wanted people to see these images and to ask ourselves, How is it possible, in the richest city in the world, [that] we are putting these people in mass graves? How is that possible? And of course, these were deaths that could have been avoided completely.

“Sound will make you see differently.”

AZ: These are two examples of making something visible by making an object or a video out of it. There’s this idea of object journalism, right? Looking at an object and seeing what it testifies to, what it’s seen. And then there’s this idea that you do, which is making an object out of journalism. How do you think about this open-ended nature of the work? I keep wondering, when you make this object out of journalism, what completes the work? What makes it different? And when does it move from an exercise, as you talk about, to a final work?

AJ: Sometimes I feel I’m a frustrated journalist. I love journalism. I spend hours of my day—of my life—actually, reading papers from around the world. Before the internet, I would go to 42nd Street. There was this marvelous newsstand where you could buy newspapers from around the world, and you could get the physical copy sometimes a week late, but I just loved to see them.

“Very few media lie. They don’t lie. They just omit.”

Of course now, everything is through the internet, and I subscribe to an obscene amount of news media, and journals, and so on. I like to see how news circulates and how a different agenda, a different point of view, changes things. And so I realize that I need to see all the different points of view to understand exactly what’s happening. Very few media lie. They don’t lie. They just omit. They just avoid certain things—but not everyone does. So when you add up everything, you end up with something similar.

AZ: Consilience.

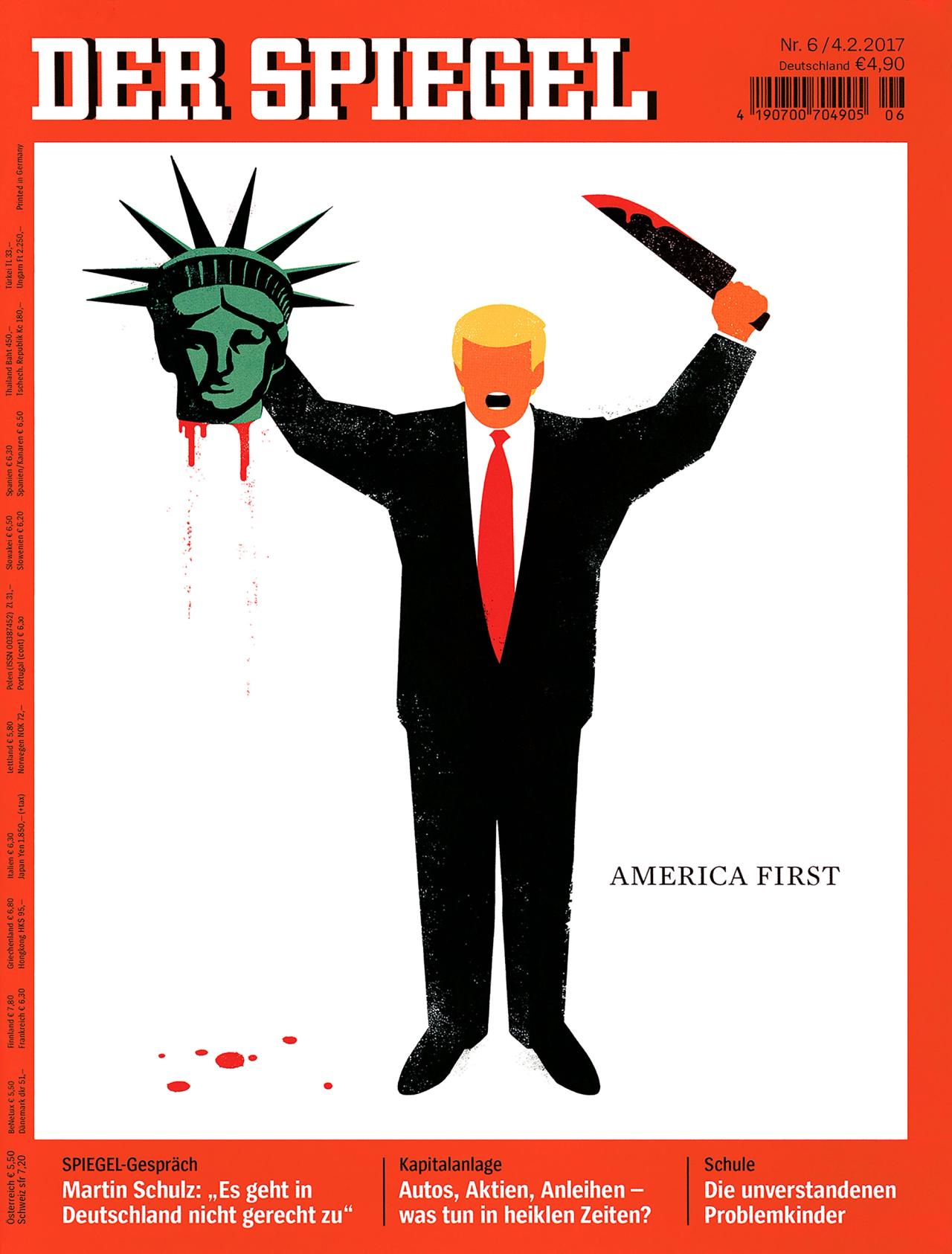

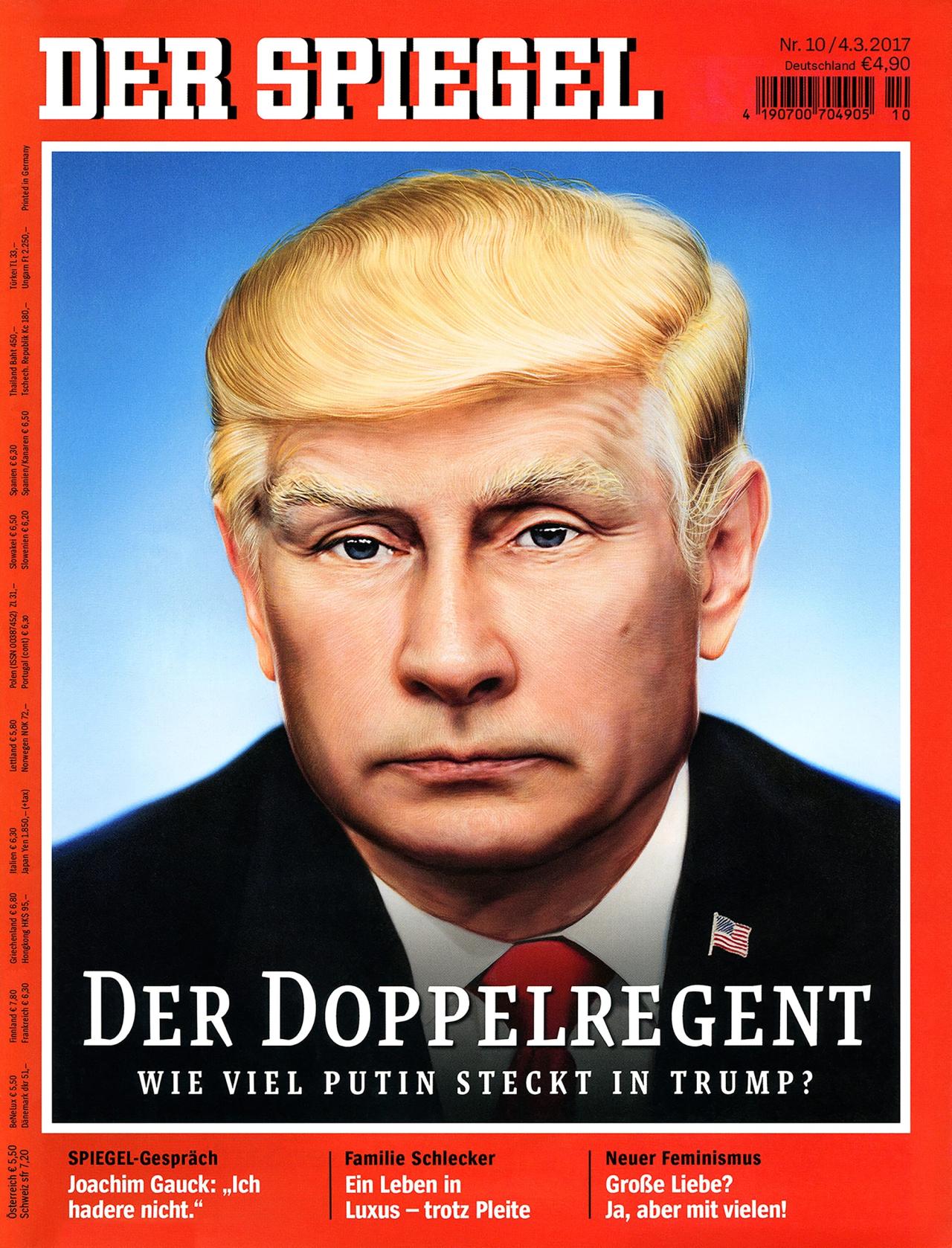

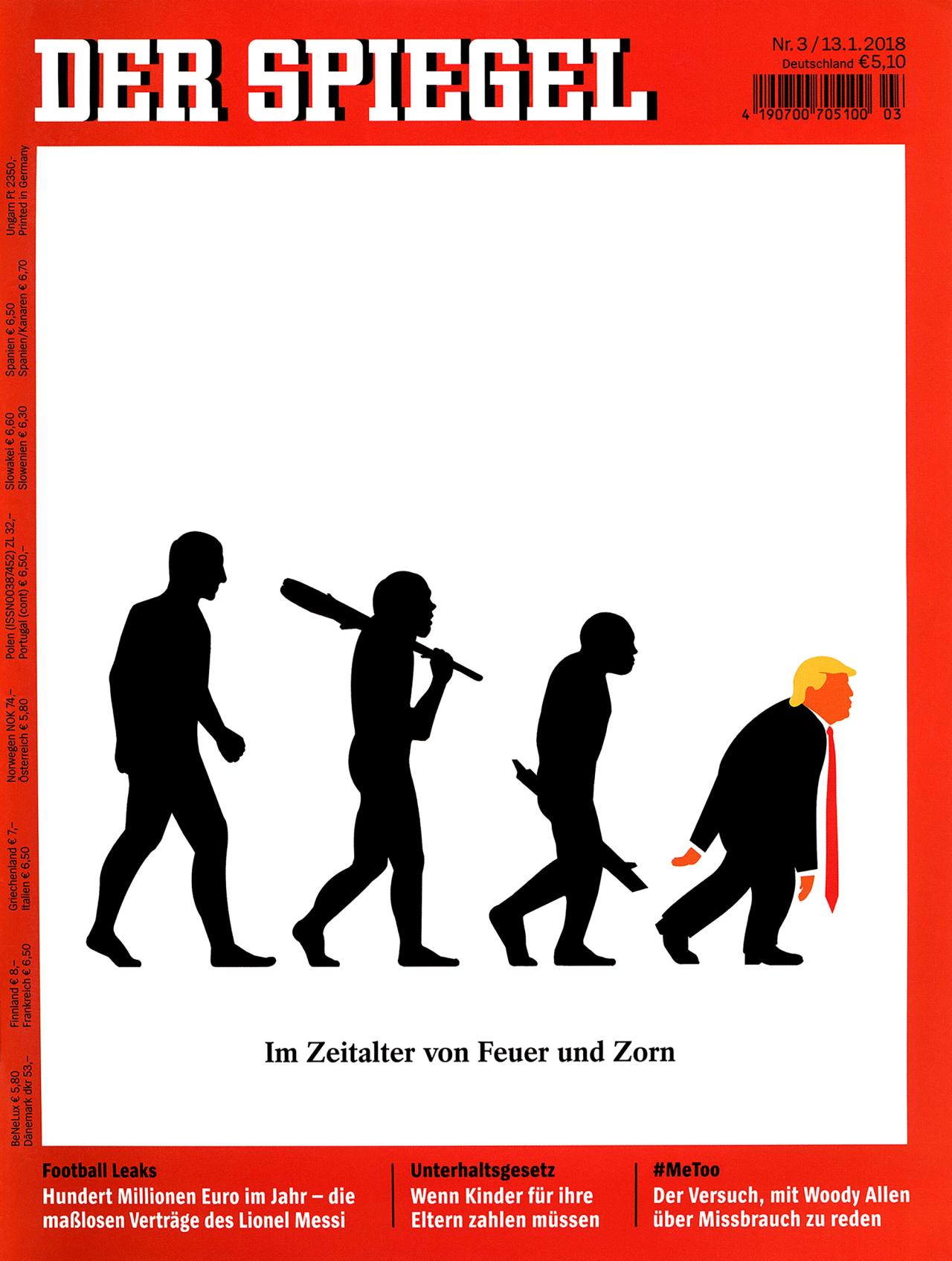

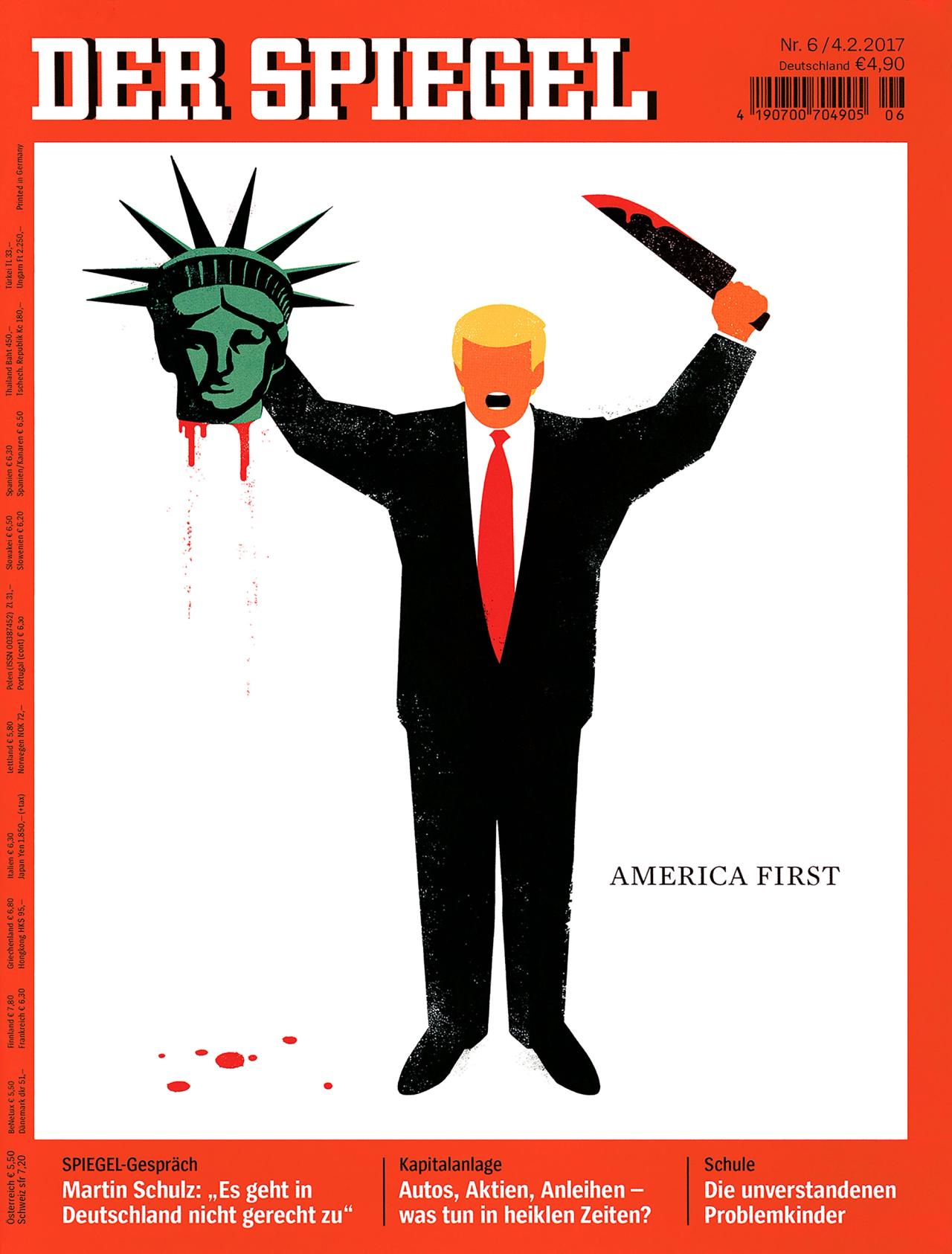

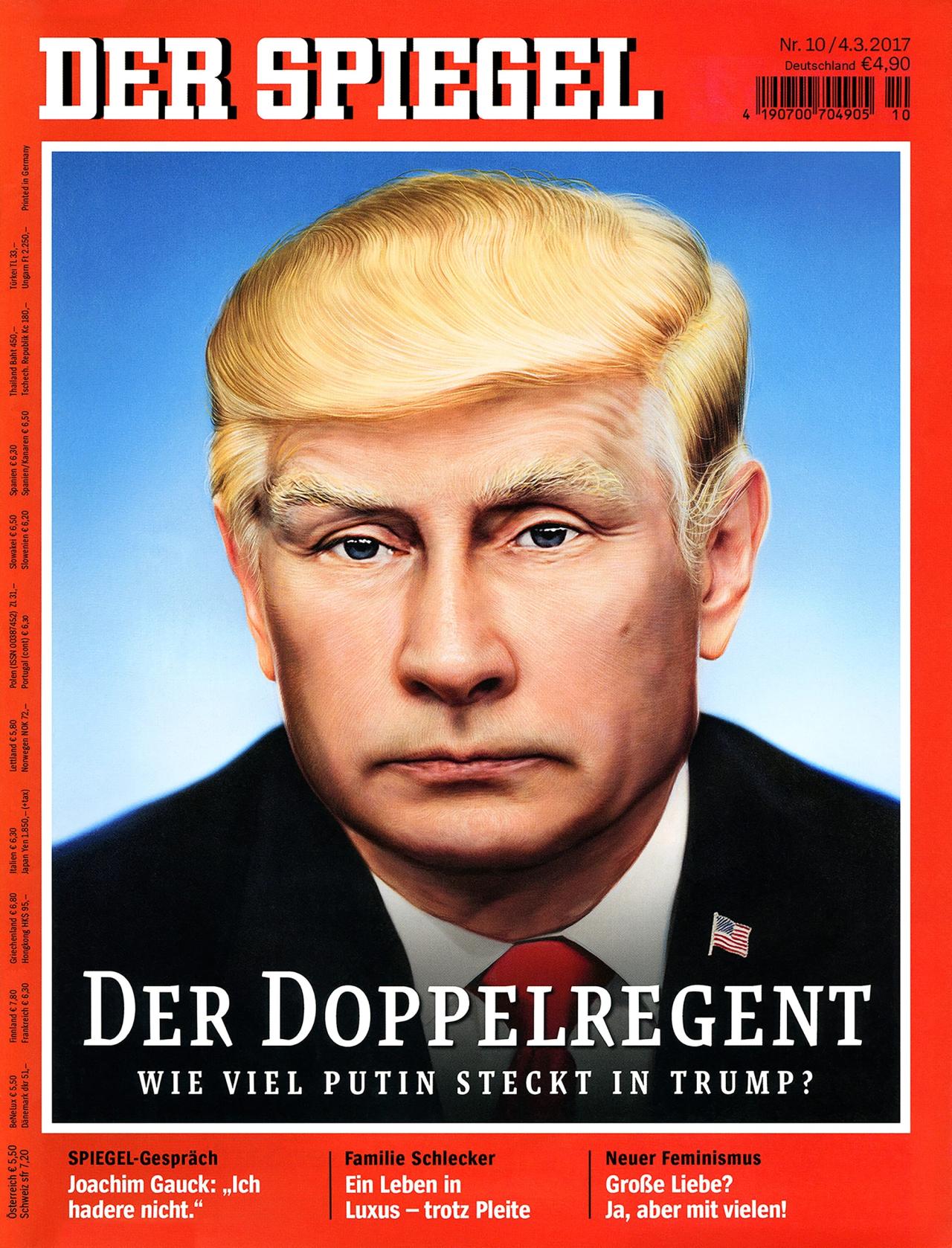

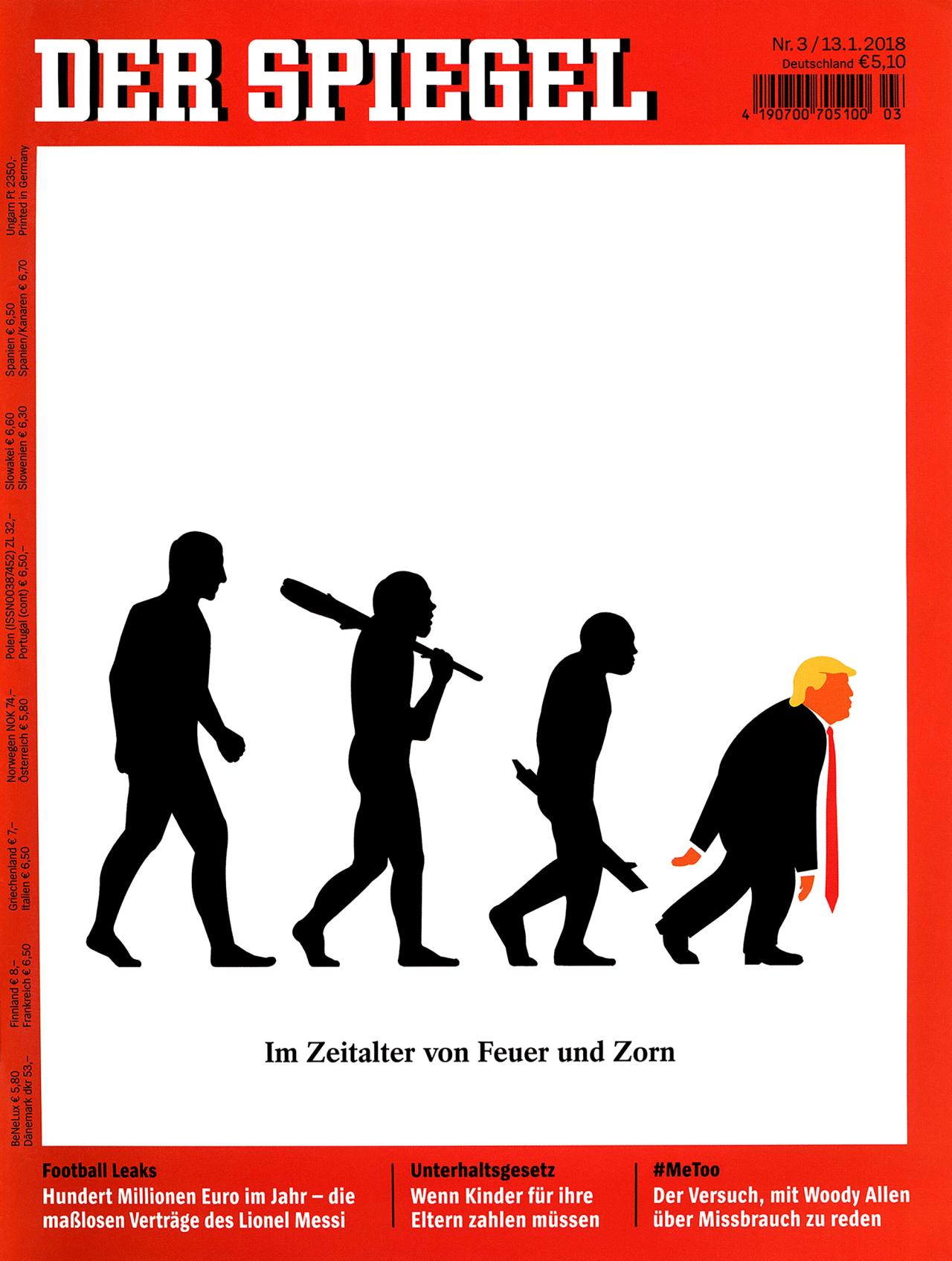

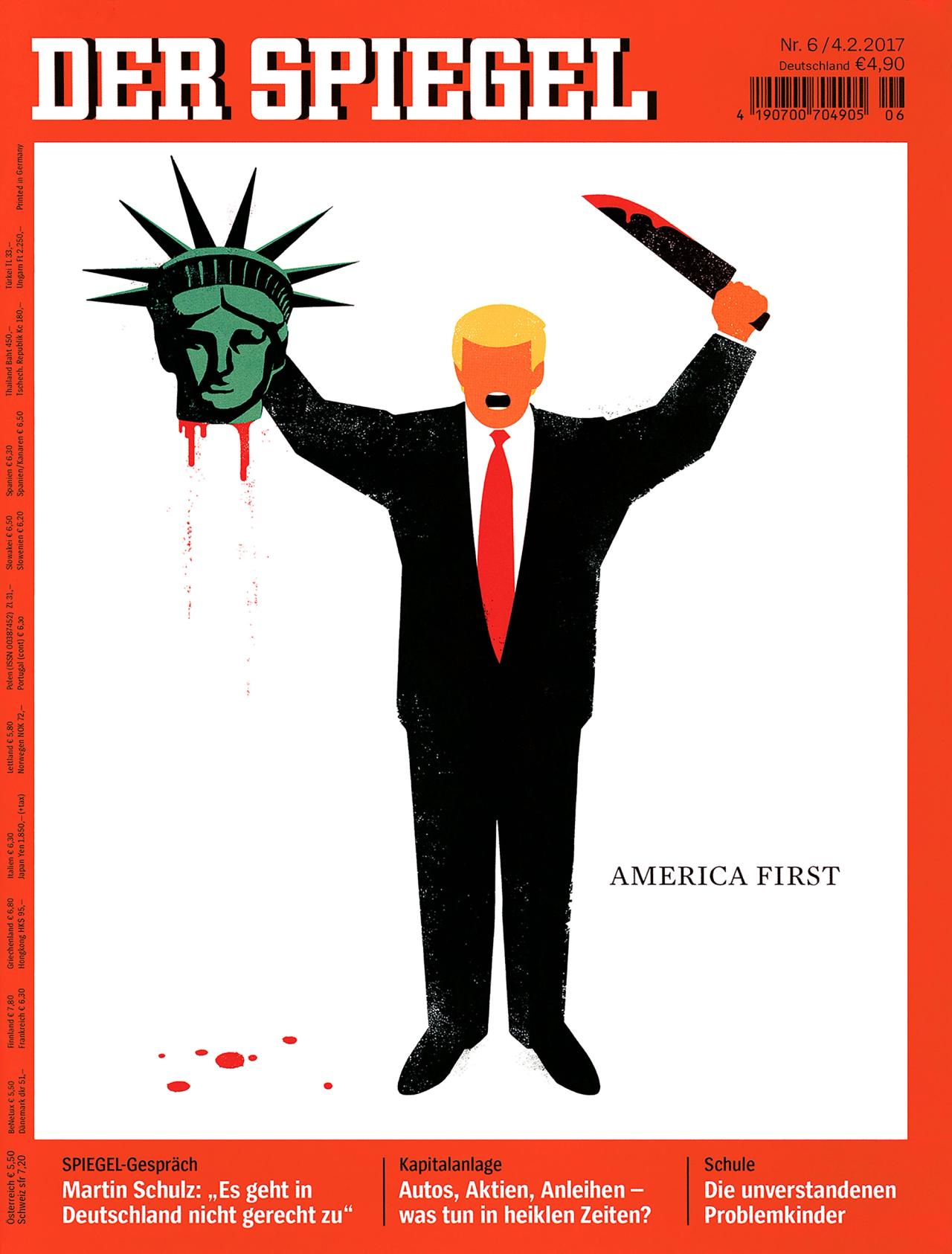

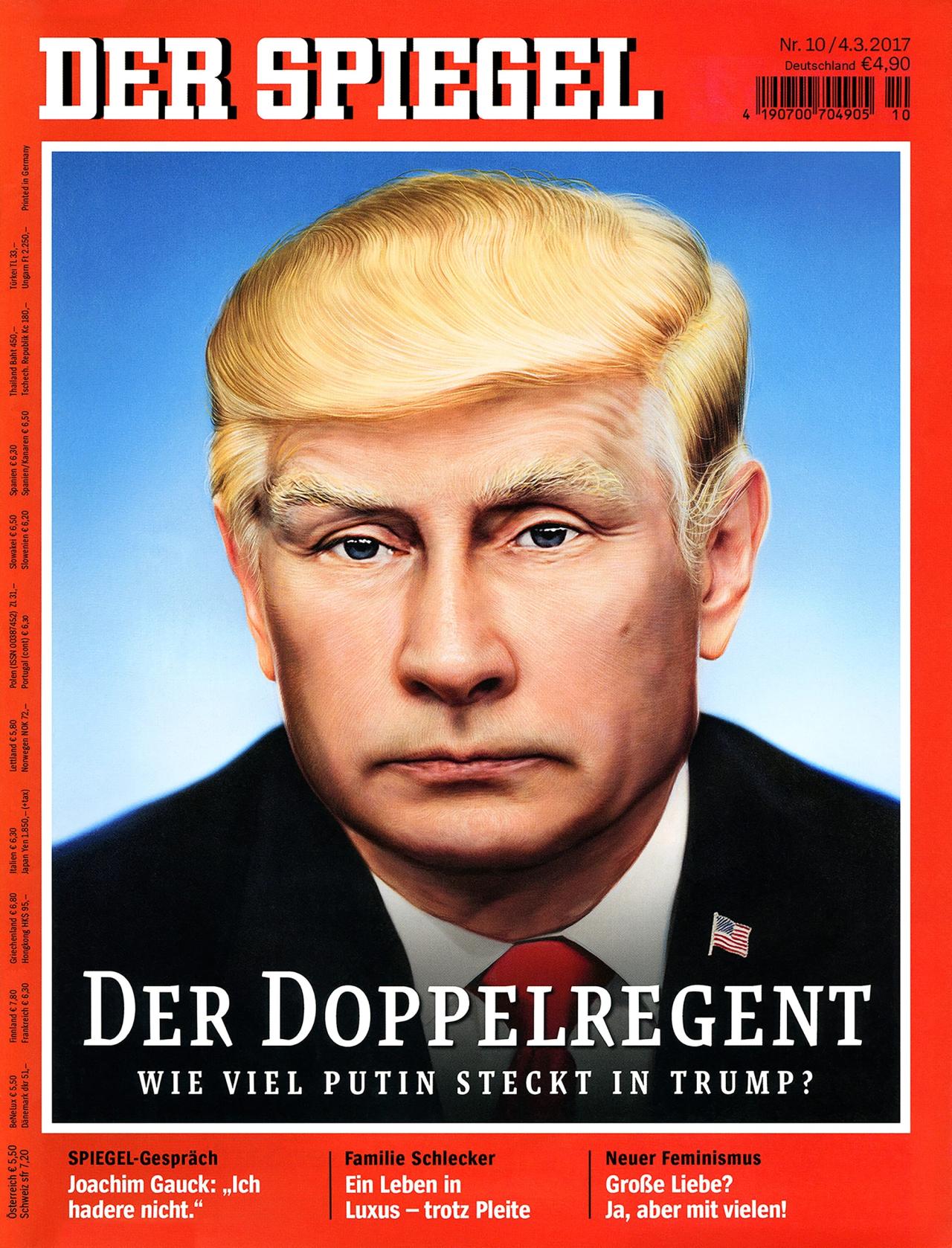

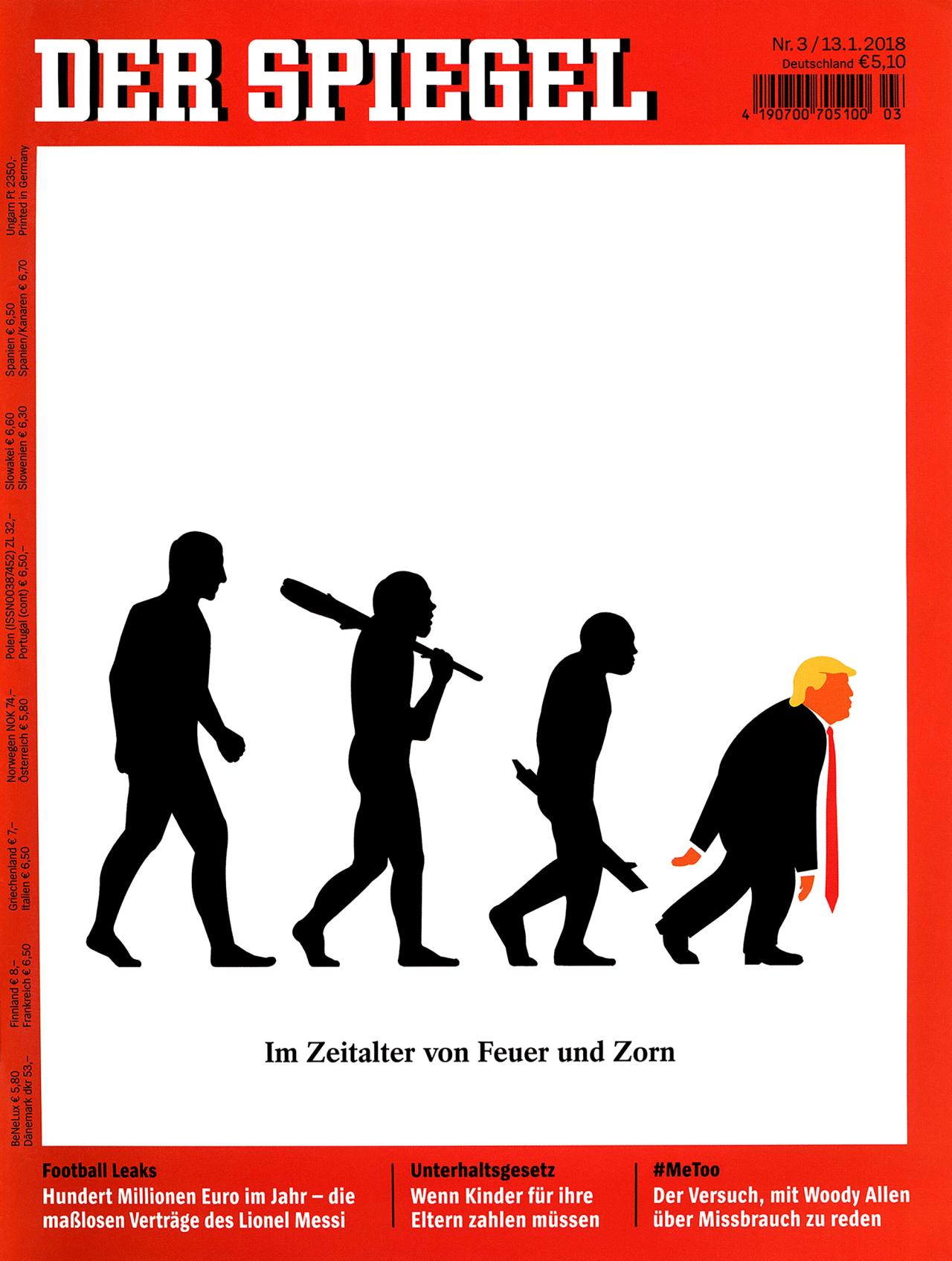

AJ: Absolutely. To the truth. So, as an artist who reacts to the world, I use this information. I want to displace it from the world of media, to the world of culture. But I have two types of work. One of them is a simple displacement. These are called the “Press Works.” These are covers of newspapers, of magazines that I see in the world of media and I found unbelievably outrageous. So I just scan them, print them, and frame them, and show them in the space of culture. I do not add anything, in hoping that this simple displacement—and inviting people from the culture world, from the art world to look at them—suddenly they see them differently, and they mean something else. So those are one series of works I started years ago. I’ve done more than a hundred of those, just magazines and newspaper covers.

“Welcome to the U.S.A.” in Time magazine (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“America First” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Der Doppelregent” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Im Zeitalter Von Feuer Und Zorn” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Welcome to the U.S.A.” in Time magazine (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“America First” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Der Doppelregent” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Im Zeitalter Von Feuer Und Zorn” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Welcome to the U.S.A.” in Time magazine (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“America First” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Der Doppelregent” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

“Im Zeitalter Von Feuer Und Zorn” in Der Spiegel (2018). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Sometimes there are images or information that I like to process myself, and I add something. And if there is a word to that additional element, it would be poetry. So I try to combine information and poetry, and I try to walk this very fine line, to do the perfect balance between the two. That balance is very difficult to reach. If it falls on the information side, it’s boring. It’s just propaganda, manipulation. It’s just text. You could have written an essay or a book, but it’s really boring and it’s talking to the converted. When it falls on the poetic side, the risk is that it is too beautiful. It is too sweet.

“I try to combine information and poetry, and I try to walk this very fine line, to do the perfect balance between the two.”

And so, you want to find the right balance. When the work informs the audience, they move them, they touch them, they illuminate them. That is the perfect balance I’m always looking for, which I’ve never reached. And I know when you reach that balance, the work would be absolutely sublime. I’ve been close.

AZ: The convergence of art and mind.

AJ: Exactly. I’ve been close in a few works, I think, but I’ve never reached that perfect balance.

AZ: So tell me more about this notion of the “exercise,” because you speak about that a lot and we hear the word practice, right? My yoga practice, my art practice—and it’s almost become a word that doesn’t mean anything. But exercise is a very different word. And you seem to delineate certain works as completed works, and some as exercises. What does reforming the context of a work by calling it “exercise,” allow you to do?

“One thing that happens with the greatest failures, the greatest exercises, is that you still learn something.”

AJ: I’m afraid that every work will fail. So I’m ready for that failure. By calling it “exercise,” I’m protecting myself in a way: Okay, it’s a test. I’m trying something out. It’s an exercise. So that makes me feel a little better with my failure that I know is coming. But one thing that happens with the greatest failures, the greatest exercises, is that you still learn something. And so each exercise gives me better tools for the next exercise. So I’m getting better, but there are still exercises in the sense that I edit down my works to the minimum. So I resist the need to say thirty-seven things at the same time. I edit down, down, down. I believe in the power of a single idea. So sometimes, I reduce it so much that I feel it’s not a complete work. It’s an exercise.

“I believe in the power of a single idea. Sometimes, I reduce it so much that I feel it’s not a complete work. It’s an exercise.”

When I have the courage and I feel that I have enough material, enough tools to go beyond the exercise, then I add more information. It becomes more layered. It becomes more complex, and becomes a work of art—and I declare it as a work of art. So these are parallel journeys, one with the exercise that feeds me every day and then suddenly I feel confident that I can release this as a work. And it’s a work that’s closed, that has a very clear objective, that, as a program, because those are the terms with which I work. I give myself a program. “In this exercise, I’m going to try to do this.” And most of the times, I cannot reach this, but that’s how I work.

This is based on the fact that I’m an architect. I never studied art. An architect is given a brief, given a space—he’s given a context, and then, you react. For an architect, it would be unthinkable to design anything without knowing where the sun [is] coming from, or who’s going to live in that place you’re going to design. Who lives next door? Who is across the street? Where is the wind coming from? How is the light at night in this place? All these questions that are so basic in architecture. I’m always amazed that in the art world, they do not exist.

“Who lives next door? Who is across the street? Where is the wind coming from? How is the light at night in this place? All these questions that are so basic in architecture. I’m always amazed that in the art world, they do not exist.”

AZ: Well in architecture—in good architecture—form is an outgrowth of program, not the other way around. And generally, within art, form precedes program and generally is where post-rationalized concept comes from. And it’s interesting how you are so rigorous about the inverse of that.

Your work deals with time in so many different ways—some durational, like your films—but the majority is a singular moment containing a number of moments. And actually, in the case of certain pieces that I’ll get to later, moments have occurred that relate to the work beyond the moment the work was made [in], like, [“A Logo for America.”] How do you think about time in relation to your work, both the time that the work is expressing and the need in this paradigm of your completed works, for it to exist and transcend time, which so many of your works seem to do?

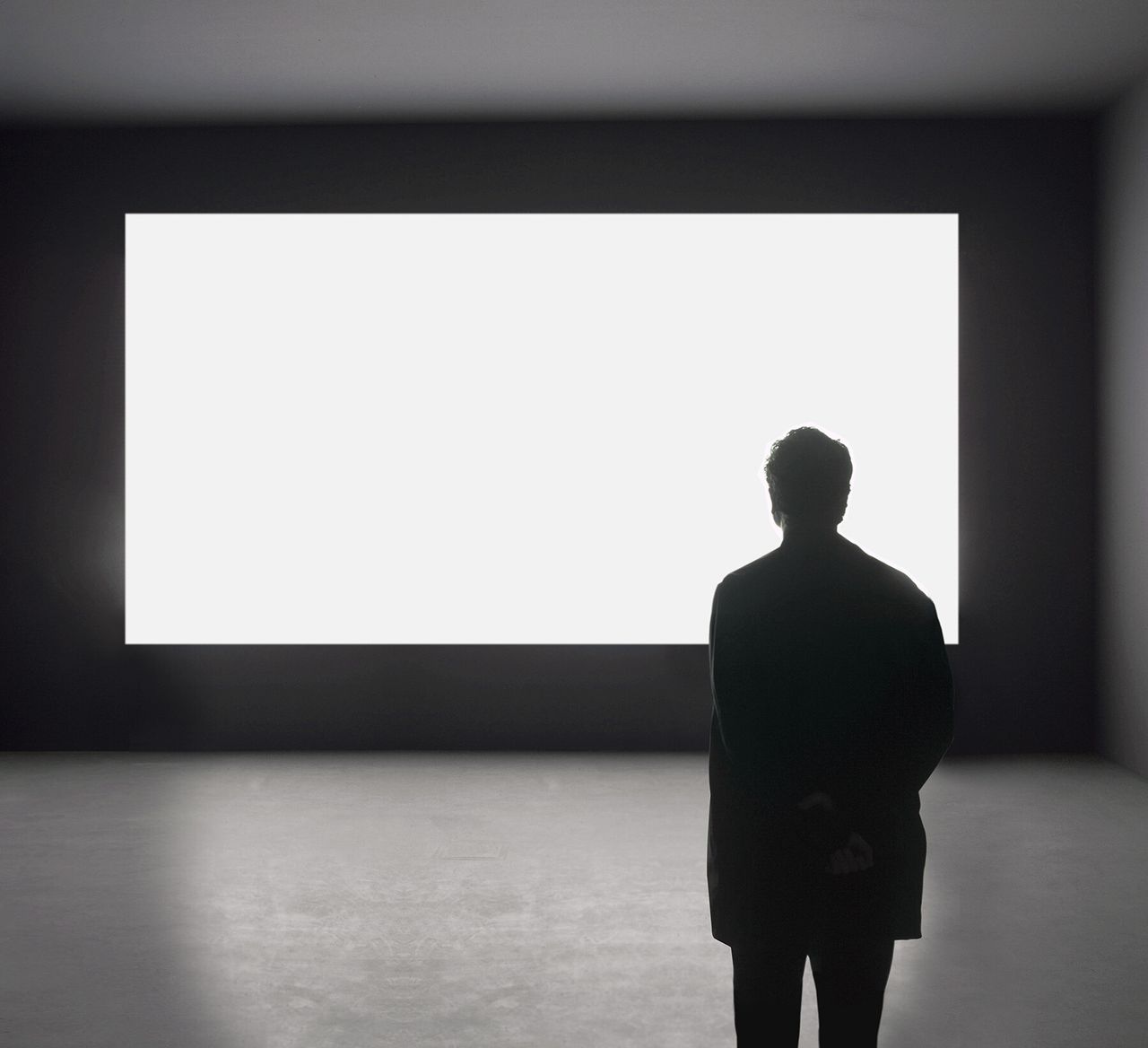

AJ: Yeah. This is a very important question for me and it’s related to your podcast project, The Slowdown. I’ve always been concerned with time. I discovered very early on that—and I read this study, this scientific study made about audiences in cultural institutions. I read something that really blew me away, and scared me. A study had concluded that the average time that a spectator spent in front of an artwork in a museum or gallery is three seconds. That is the average time: three seconds.

We spend half a life creating a project, a work, or three years. You put it up; it takes you a month to produce it. You put it up, and people walk by in three seconds. That’s a very scary thought, and I’ve always had this in mind. In some works—in most of my works—contains a plea, contains a demand: “Please stay with me. I’m going to tell you something, but please stay with me.”

“I try to slow down people. I have to. If they don’t, then they won’t see the work.”

So I invented this mechanism with a red light and a green light, or an architecture that forces you to come in; a work that forces you to move around, to see more. If you don’t [make] an effort, you don’t see anything. I try to slow down people. I have to. If they don’t, then they won’t see the work. So when I design a work, as part of the program, I’m always asking myself, Okay. What am I doing here to justify people spending more than three seconds with me? And if I do not have a good answer, then I don’t do that work. I have to have a good answer to that question. What am I doing? Why would people spend more than three seconds in front of this? It’s a huge dilemma that, I think, everyone of us confronts. Just go into a museum and see how people move around. It’s quite amazing and shocking.

AZ: I also want to mention that another mechanism you seem to do, aside from how people move through space, which is the same as a Japanese garden designer would do—the texture of the path shifting, and things changing to intentionally slow you down and directo your gaze—is, you seem to use beauty as a way to slow people down. The works you make are arresting. The two facing light boxes. The objects themselves always tend to have some novel approach through a kind of surface aesthetic that works to slow people down.

“I’ve never been afraid of beauty.”

It’s always interesting to me how violence and beauty, or this duality in the work that you make, exists. How you can wrap a tragedy in some sort of aesthetic convention that’s beautiful. Is that one of the prerequisites for you? Do you ever stop and just look at work, no matter what the content is, and say, “Well, if it’s not beautiful, no one’s going to look at it?”

“There is no way we can produce anything and put it out in the world, without [it] being an ethical decision and an aesthetic decision.”

AJ: I’ve never been afraid of beauty. Early in my career, I was brutally attacked for using beauty in works that were dealing with tragedies. And my view was so simple, so logical, in my sense. My view was saying, “But listen. Okay, these people are poor. They have a difficult life. They have gone through this incredible tragedy. Why can’t I dignify the subjects of my work with beauty? Why? Why [does] the work have to look ugly, because these people are poor, or they have suffered these tragedies?”

And also, if you think about it, if you go to the concept itself, every representation is an aesthetic decision. There is no way to represent anything without taking an aesthetic decision. It’s impossible. So everything we do represents, or at least we have to be aware of—because some artists do it without realizing it—but everything we do is an aesthetic decision, and is an ethical decision at the same time. There is no way we can produce anything and put it out in the world, without [it] being an ethical decision and an aesthetic decision.

French-Swiss film director Jean-Luc Godard. (Photo: Gary Stevens)

That’s when I bring a quotation from Jean-Luc Godard, the filmmaker I love very much. Godard said, “It might be true that you have to choose between ethics or aesthetics, but it is also true that, whichever one you choose, you will always find the other at the end of the road.” So I’ve always had this in mind. And when I’m articulating the final thoughts on a work, and I have to realize something concrete, something visible, I’m aware of this duality, and I try to be perfectly aware. What is the ethical component, and what is the aesthetic component?

AZ: Which is why the question of, “How is art political?” is absurd, because it’s people, and politics are people. We’re always going to wind up there, no matter what, as Godard points out. We’re never at a loss of inspiration for rage these days, but being someone who begins their day with two hours of reading the news, thirty-plus media outlets, what events in this moment in time are keeping your focus?

AJ: There are so many. I think I’m following seventeen different tragedies around the world right now. That’s how I work. I keep track of different things, and suddenly something will happen when that forces me to go, and that’s how I start a project. That’s what took me to Rwanda. That’s what took me to Hong Kong. That’s what took me to Tijuana, et cetera, et cetera. But maybe I’d like to mention maybe two or three.

Jaar’s series “A Hundred Times Nguyen” (1994), which features Nguyen Thi Thuy, a young refugee born in a detention camp for Vietnamese refugees seeking asylum in Hong Kong. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Of course, it looks like we’re coming out of Covid. I say it with a little worry, but it looks like we’re coming out of Covid. But Covid, for me, was a realization that, whatever happens in the world, it’s still so obvious, so transparent, that the inequity that exists will be visible through these new tragedies. When I looked at the situation of the vaccines available in the world, I was shocked. I was shocked. When this country, or most European countries, had five, six times more vaccines that they needed, there were more than a hundred and thirty countries without access to a single vaccine. So there was really a vaccine apartheid, and that was extremely painful to watch. And, as you know, there have been a lot of demands for the big pharmaceutical companies to release their copyrights on their vaccines so it can be fabricated in developing countries, but they have refused that. I’ve been really shocked at that, at that issue.

“Covid, for me, was a realization that, whatever happens in the world, it’s still so obvious, so transparent, that the inequity that exists will be visible through these new tragedies.”

I’ll give you a shocking example. In South Africa, in Cape Town right now, there is a small lab called Afrigen. It’s a small lab run by women in Cape Town, in South Africa. And then, what are they trying to do with the help of the World Health Organization? They’re trying to reverse-engineer the Moderna vaccine. I repeat: to reverse-engineer the Moderna vaccine. That’s where we are now in the world. Instead of just getting the copyright and doing it now, they’re going to spend one or two years reverse-engineering these vaccines, so they can have it, to save their people.

I mean, when I read things like this, I’m ashamed of being a human being. Pfizer and Moderna are making more than a million dollars per hour right now. They make hundreds of billions of dollars per year thanks to the vaccine, but they won’t release the rights for people around the world that cannot afford this vaccine [and so have] to fabricate it themselves. And if you go into the small details, the E.U., the European Union, pays two dollars and fifty cents per vaccine to these pharmaceuticals. Uganda pays seven dollars. So this is just not acceptable. This subject kept me awake during the Covid times and it’s still going on, in spite of the fact that it looks like we are coming out [of the crisis] finally, at least in this country.

The second issue maybe we have to talk about is what’s happening in Ukraine. Ukraine is a tragedy. It’s a tragedy, and what’s happening to Ukraine is intolerable. But—there’s always a but—one of the things that has shocked me is that, before the war started in Ukraine, there were eighty million refugees in the world, and that’s one of the greatest subjects of my work. I’ve been following this issue for a long time. And we saw the despicable way Europe rejected those refugees.

And now, they’re opening their homes and their hearts to Ukrainian refugees with an extraordinary generosity. The E.U. now is working on a new law, which will allow Ukrainians to live and work in any European country for three years. That’s marvelous. What a generous and humane response to this tragedy. But a month before, was nothing of this. They were rejecting everyone. And so, what keeps me awake at night is, I’m thinking about those refugees that were rejected by Europe, that couldn’t get in, that were sent back, and they are now in refugee camps in Turkey, in Lebanon, in Jordan. There are more than seven million of them right now.

And these people, they’re watching the news, and they see how Europe is treating Ukrainian refugees. What are they thinking? What does it tell them about the state of the world? That thought—what are they thinking?—that thought is a torture for me. It pains my soul. So that thing is really right now, what keeps me awake.

AZ: And the way you’re looking at those two cases, is a very clear example of synthesizing for an insight, which is what you do. You look at stories across, and you pull pieces of disparate information to create a new thought. Will those two rocks in your shoes become work? And are you actively working through exercises in those spaces, in real time? And I ask that because I’m wondering, you look at a life like yours, and the journey you’ve had, and you think, So every day, he starts by reading the news for a couple hours, and then what does he do? What does he do after that? It happens in your mind most of the time, correct?

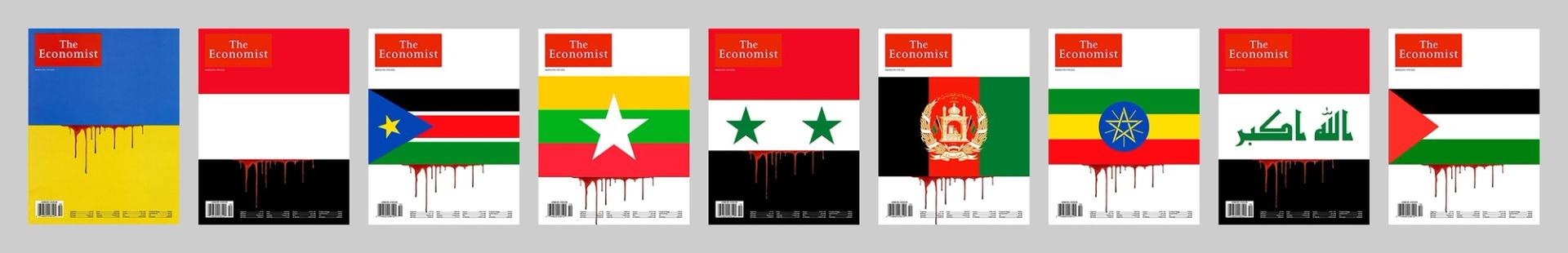

AJ: Yeah, absolutely. And I do exercises. I’m going back to the exercises. The last exercise I did was with the cover of The Economist two weeks ago. The Economist had an extraordinary cover, a very minimal cover. They just had a blue and a yellow area, very minimal. In the fine line between the blue and the yellow, they had a little blood coming out. So it was horrific and minimal at the same time. And I thought, Wow, this is a fantastic cover. This is absolutely brilliant. But The Economist—I’ve never cared about these issues, never. I’m a subscriber to The Economist, among other things. I disagree with ninety-five percent of The Economist, but I read it because it’s a marvelous, extraordinary, brilliant, intelligent paper. And in my thirty years as a subscriber, I’ve never seen anything like this. They have never cared about any other conflict in this way. Suddenly, they care about the blood being shed by Ukraine.

Jaar’s series “Mea Culpa” (2022). (Original cover by The Economist far left). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

So I took that cover, and I did other covers as a proposal for The Economist. I did a cover on Yemen, for example. Yemen is suffering a tremendous tragedy right now. Or South Sudan, or Ethiopia, or Afghanistan still, and Iraq, and Syria, and so on. I mean, all these countries have suffered the same or worse than what’s happening right now in Ukraine, sadly. And they never did anything. So I created eight alternative covers for The Economist, and I sent it to the chief editor, with my compliments. Of course, nothing will happen. But it’s an exercise as a therapy that will make me feel a little relieved. It’s not going to make a difference. I do it for myself, for my sanity.

AZ: Well, the question you’re asking them is, “With this barrage of information, how do you choose which one to work through?” And I guess my question before relates to that [which] is, what you deal with is a sort of sifting through what matters. And it’s in that sifting where you make your choices. And have you noticed a pattern through the choices you make, of which to select? Because you haven’t covered every tragedy in the world, like you’re asking The Economist to do. Yourself, how do you make that choice?

AJ: That’s when I just wait for my heart or my brain to explode with rage. I follow events. I read about them. I research them. I want to understand exactly what’s happening. Why is it happening? What’s the story? What’s the background? What is the interest of the United States in supplying the weapons to Saudi Arabia to attack Yemen? I need to understand why. There are two million Yemeni refugees. They have killed half a million people. These are the weapons that we give to the Saudis. I need to understand why.

“I research. I try to understand. Then something happens that I cannot control myself. I think, Okay. Enough is enough. I have to do something about this. That’s how a project is born.”

So anyway. I research, I research, I research. I try to understand. And then something happens that I cannot control myself. And I think, Okay. Enough is enough. I have to do something about this. That’s how the project is born.

AZ: Since the eighties, you’ve been investigating, as you say, so many of these tragedies. The Rwandan genocide, the gold mining in Brazil, the toxic pollution in Nigeria, the border between Mexico and the United States. If we were to take four decades of work and put it into one museum, or one context, you imagine all of the works in one space, what would the theme—if you reduced it essentially down to its true essential quality—what aspect of the human experience does the work speak to?

An image from Jaar’s series “Geography = War” (1991), which addresses the dumping of toxic waste in Nigeria by industrialized countries. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

AJ: All these events or tragedies might be very different, and include and concern different players. But in the end, I think that I’m a humanist, and I’m interested in human rights. I think this issue of human rights and justice is what moves me. I look at an event and when I see that it’s not being treated fairly, I react, and I follow it, and I end up doing something.

Hopefully, what these works would have in common would be to try to first, again, inform about this event, because I’m always not sure that people really know what happened here or there. So I need to inform them, to give them the facts, but present the facts with a certain amount of information and poetry, like I was saying earlier. And people will leave that space with a new understanding of that reality. And perhaps they will be moved to act, or at least to consider thinking about these issues that affected these lives, and how we are connected to these lives. It’s a lot to ask from my audience, but I’ve never been able to do any other kind of work.

“I’m not the artist that can sit in a studio in front of a white piece of paper and start something out of my imagination.”

Every single work of mine is a response to something that happens in reality. I’m not the artist that can sit in a studio in front of a white piece of paper and start something out of my imagination. There isn’t a single work that has done that. I just don’t know how to do it. Every work responds to something that is happening or has happened, and I feel the need to comment on it.

AZ: All of it seems to be you asking us, an audience confronting the work, “How is it possible that, as a human being, you can comply with inhumanity?”

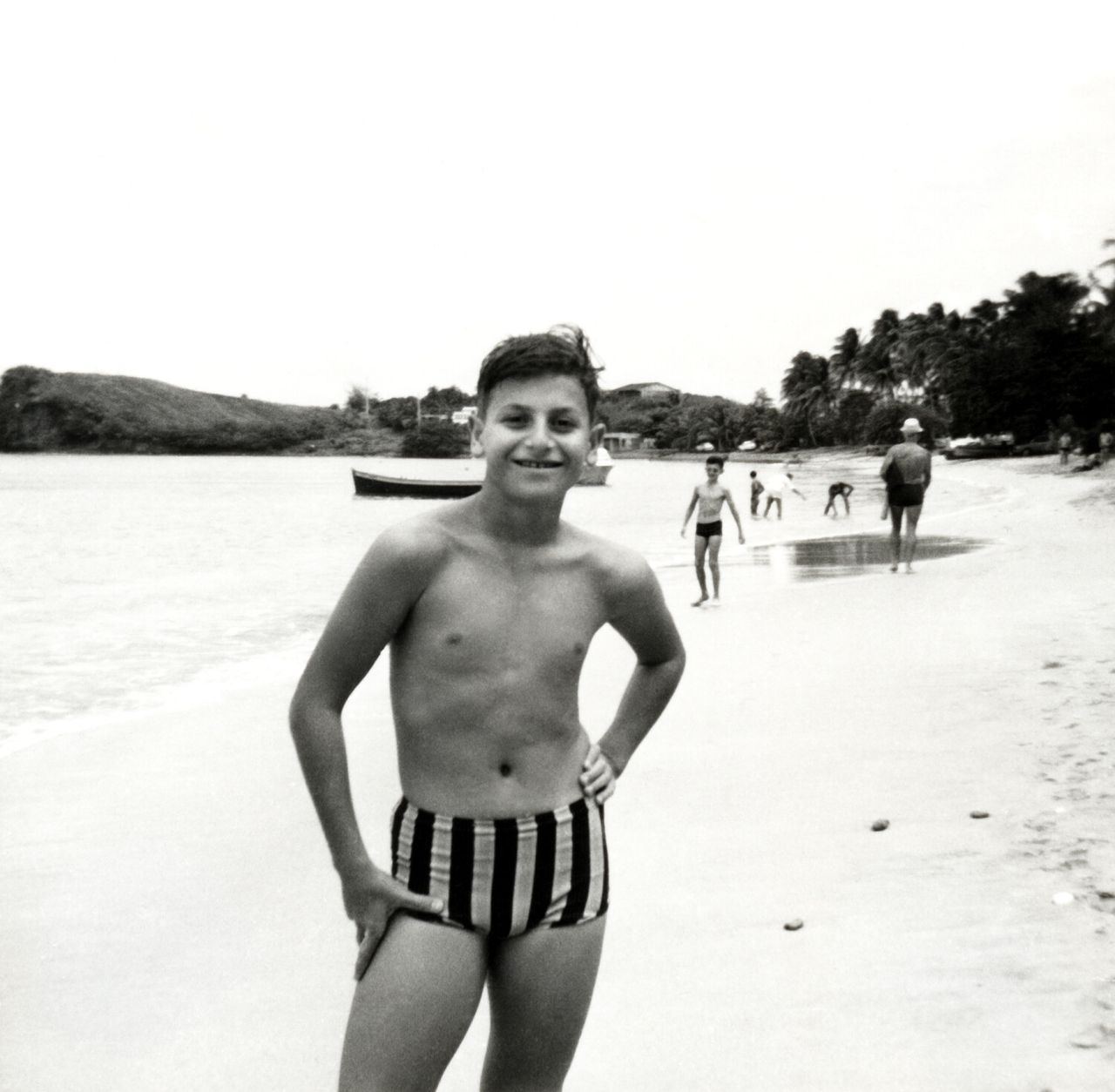

Jaar as a child in Martinique in 1970. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Totally dumb, but I do want to go there. Will Smith slapping Chris Rock, which took over a genocide … I mean, of all of the crises in the world, it sort of took over. But the most interesting aspect of it was, how did people applaud him in the room? And this question of, how did people, who were in the room, not get up and say something? How do these echo chambers in our current society create a space where you can equivocate your own validation of a moment that you’re witnessing? Does this seem to consistently come up to you with all the information? How is the world applauding this, or standing by?

AJ: Well, these types of things are happening all the time, and we are bombarded by these distractions. I just keep a healthy distance from these things. I’m very rigorous in the sense that I try to focus on what’s important, what’s relevant, and I don’t fall into those traps. I just don’t. I know what’s happening. I realize what’s happening, it’s very transparent. It’s very sad, but these are distractions, absolute distractions. I just don’t go for them. So I try to keep aware of the big picture.

AZ: Yeah. The long view.

AJ: Yeah.

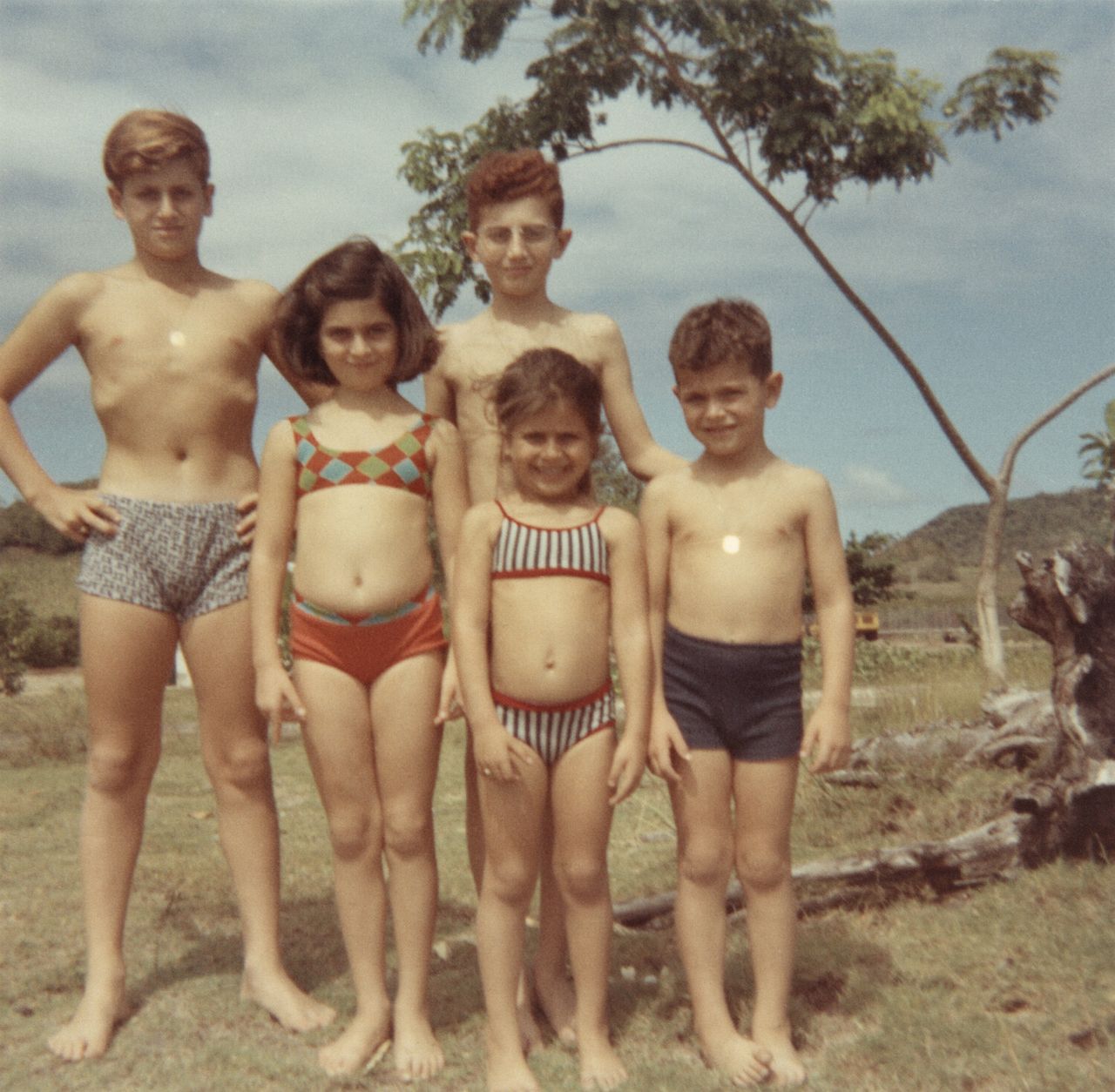

Jaar (right) with his brother Eduardo (left) in Fort-de-France, Martinique in 1963. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

AZ: You grew up in Chile during a time of very high censorship—[with the] entire media system controlled by the military. How did this experience of growing up during that time influenced the nature of your work, and the way you think about truth and justice?

AJ: We lived through censorship. And worse than censorship is self-censorship, because we were afraid.

AZ: Even as a child, you remember feeling this way?

AJ: Yeah, absolutely. We were afraid of saying certain things, talking about certain things. People could be disappeared if [they] expressed dissident views. So we learned how to speak in between the lines, in a poetic, cryptic way.

AZ: Since hearing your parents talk.

AJ: Yes, and going to school and…. There are things that you wouldn’t touch with language. And so we learned that kind of language in between the lines, and we also learned how to fix our red lines: This is a red line I cannot cross because it’s dangerous. So in a way, it was an exercise in learning how to navigate in a situation like this. And I’m sure, consciously or not, I apply some of these lessons in working today with media.

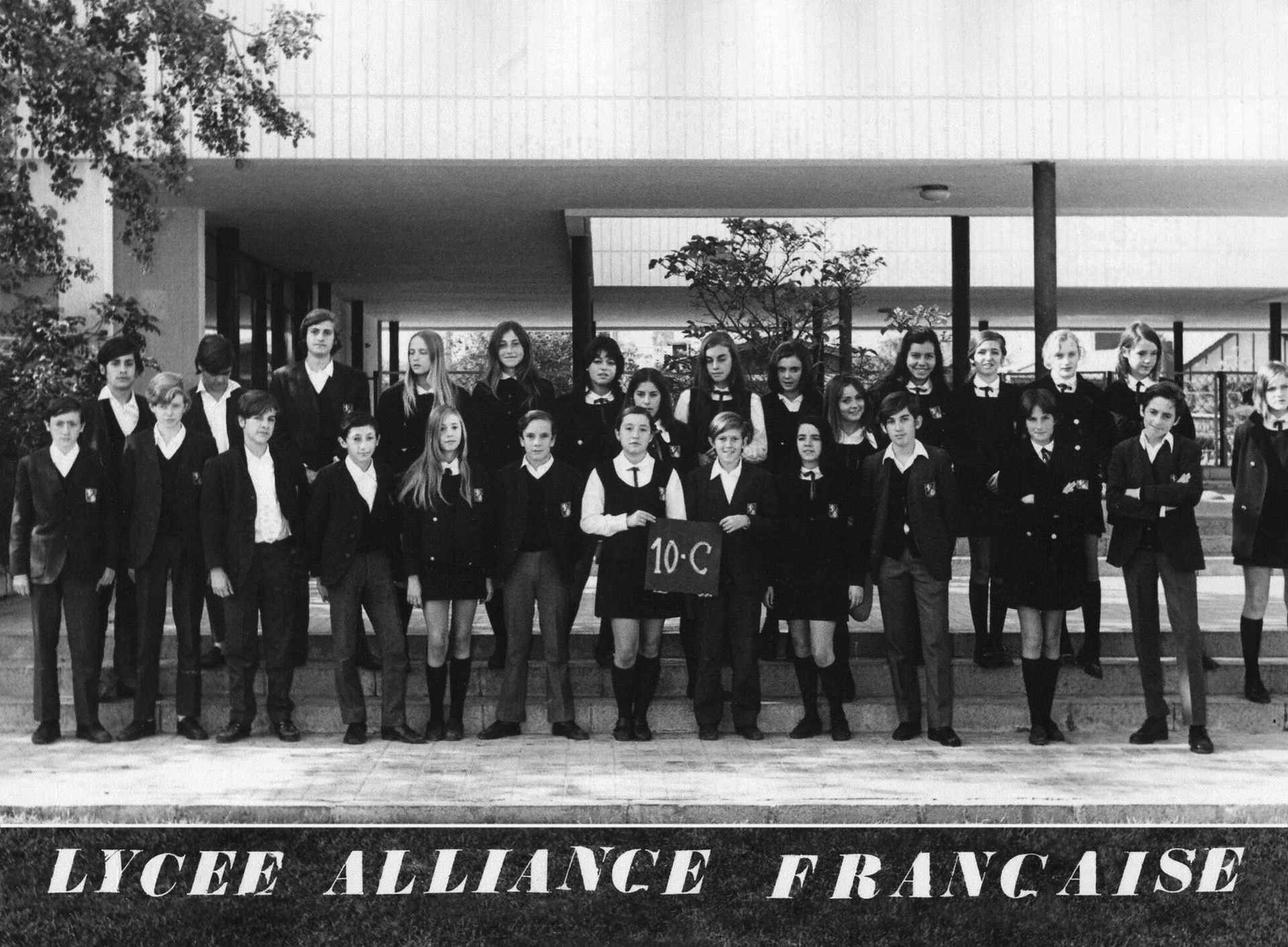

Jaar (third from left in back row) in high school in Santiago, Chile, in 1972. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

AZ: What was your childhood like? How do you conceive of it now, when you think back?

Jaar with his siblings in Martinique in 1968. Top row, from left: Alfredo, Eduardo. Bottom row, from left: Beatriz, Maria Cristina, Antonio. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

AJ: I was a very shy kid. Very shy.

AZ: Siblings?

AJ: We are five siblings. I was the oldest. I was extremely shy, so much so that when I was getting a prize at school…. At the end of the year, you had to go up on a stage to get the prize and to get some books and so on. I would refuse to do it. I was really scared. And so my father took me to a psychiatrist, and asked about this extreme shyness. And this psychiatrist suggested not pills, not treatments. He said, “Why don’t you buy him a box of magic tricks?” And my father thought, Well, yeah. Why not? It’s a good idea. Yes, let’s try that first.

So a week later, I received this box of magic tricks and I was fascinated, and I started learning magic tricks with cards, with different things. And of course, I had to practice in my room, in front of a mirror. When I was ready, I would call my parents, my siblings, and make a little spectacle, a little show, and show them the trick. And of course, when you’re a magician, you know that people know that they will be tricked. And so they try to catch the trick, and you try not to [let them] catch the trick. There is a kind of understanding between you and the audience that you’re doing something, that they’re being tricked. And so you have to learn how to do it, and you have to do it well, and so on.

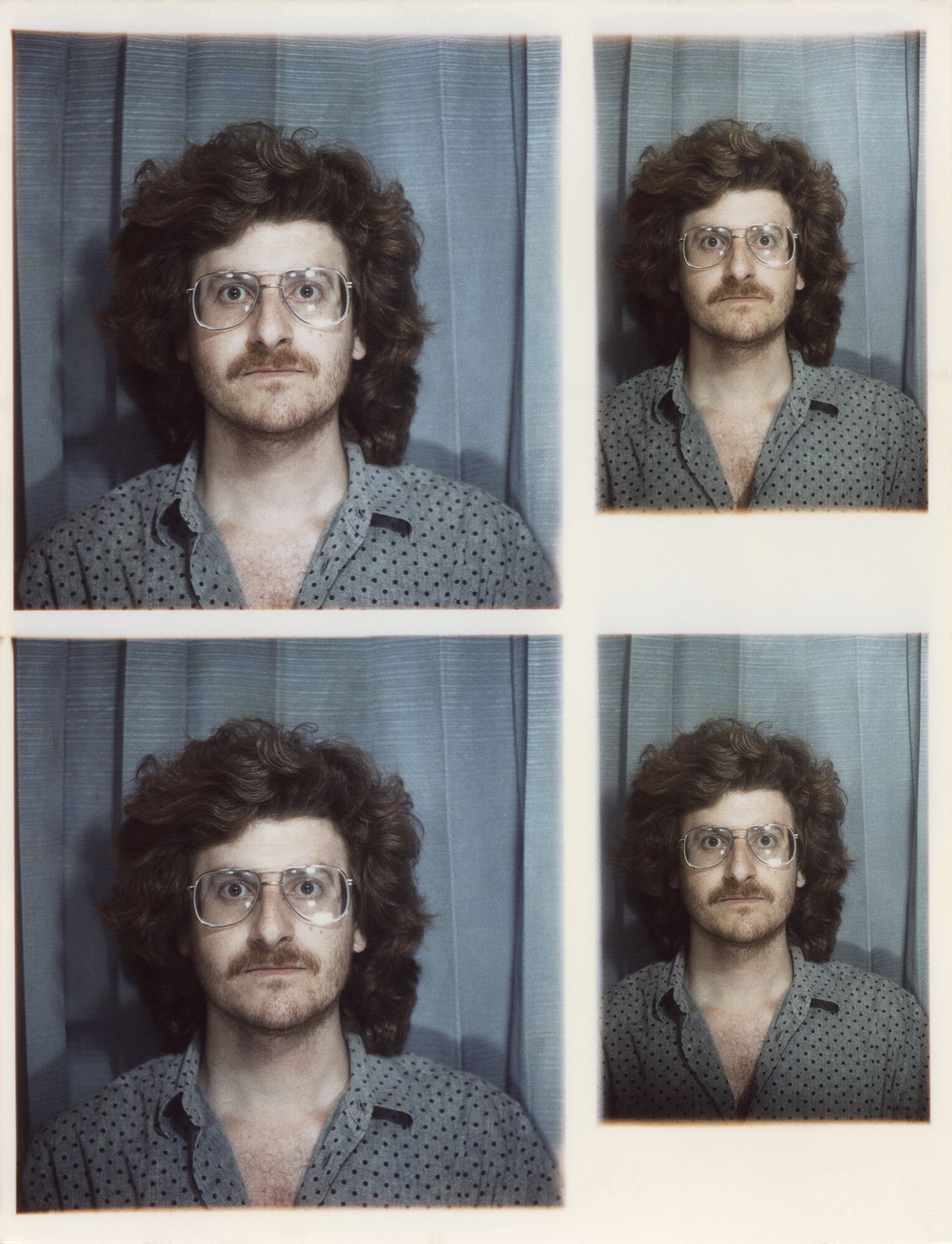

“The Magician” (1979/2012). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Little by little, I got into this. I created a magic club, and I developed and designed new magic tricks, and I got a huge collection of magic books, and magic boxes, and so on. And a few years later, I realized that my shyness was gone, because [through] this exercise of doing magic and presenting the tricks to an audience, I had gotten rid of the shyness. But this magic aspect of my life that lasted for at least ten years has never left me. And when I’m creating a work of art, I’m always thinking about that. Where’s the magic? Where’s the surprise? People is coming to see this, and suddenly they will see something else, that they do not expect.

So this part of my practice is highly influenced by the way I grew up with magic. And actually, I still go to see magic spectacles. I love it. I’m like a kid when I go to see that, and sometimes I try to catch the trick, and sometimes I just enjoy the magic.

AZ: So you went through school, and then you wound up studying architecture and cinema. The two specific themes of architecture and cinema, how did that affect—not just you make videos and you think about program—but how did architecture and cinema, which are two very distinct fields, inform where you wound up going, do you think?

AJ: I wanted to be an artist, but my father thought it was a bad idea, and he suggested that I study architecture. And I agreed with him, I studied architecture. Early on in architecture, I discovered that I was the luckiest man on the earth. Architecture helped me to understand the world, gave me tools to understand the world, to understand the context in which I was living, and so on. So I do what I do as an artist, thanks to architecture, but this was the Pinochet years. And after five years of architecture, I realized that the architecture profession in Chile was at the service of this new neoliberal economy, that the Pinochet regime, thanks to Milton Friedman and the Chicago Boys, was imposing in Chile. And I was disgusted by the lack of political awareness. They were just following the dictatorship.

“Architecture helped me to understand the world, gave me tools to understand the world, to understand the context in which I was living.”

So I abandoned architecture, and went into film. I studied film for three years. I got my degree as a filmmaker, and I didn’t know where to go next. We were still under dictatorship. There was very little money for filmmaking, and I had abandoned my architecture studies. I was already interested in media and I was subscribed to many magazines, among them, a very important film magazine called Cahiers du Cinéma. So I get the new issue of Cahiers du Cinéema, and there is a kind of survey among eleven filmmakers, and they asked them all the same questions. The last question they asked to these eleven filmmakers was, “If you were not a filmmaker, what would you do?” This is a true story. Ten out of eleven responded, “I would be an architect.”

Jaar (front, center) with other architecture students at the University of Chile in 1981. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

So suddenly—you know, I was young, I was a kid—suddenly I realized, Wow, so there is a connection between architecture and film. I had not never thought about it consciously. I had gone from architecture to film, and that was it. And I thought, I have to finish my architecture studies. So to the great delight of my parents, it was this magazine that convinced me to go back to architecture, not them. I went back and finished, and then I think I started exploring the links between those two disciplines. And of course, they’re extremely connected.

“Architecture is not creating a space. It’s about bodies moving in that space.”

Architecture is not creating a space. It’s about bodies moving in that space. When you’re filming space, you are moving. You’re filming a scale, you’re filming light. It’s all connected. It’s quite extraordinary. So I feel very privileged, because those two things are my background. And with this background, I come into the art world and I start doing these things that react to the world with these two disciplines in my pocket. And so that explains what I do.

AZ: That’s interesting, this idea of containment that you talk about. The frame, the film, the architecture, is where life occurs within that. You talked about how we’re taught to read, but not how to see an image. And I was thinking about architecture and cinema as a period of your life where possibly you were taught how to see, and taught how to look. Were the studies that you were doing at that time in architecture and cinema mostly just looking? Was that the period where you learned how to look at something critically?

AJ: Absolutely. Absolutely. That’s where I learned how to look, and how to see, and how to understand. My architecture studies and my film studies include a lot of semiotics. I was very privileged with that education, and they formed me. They really formed me [into] who I am. Unfortunately, the dictatorship was in the background, but still we were able to live and to keep going.

AZ: I want to talk about how you got to New York and a number of things you did at the beginning. But before that, you are a parent, and you experienced being a child and a parent. And I found an interesting link—I’m a big fan of your son Nicolás’s work, as I’m sure many of our listeners are. Just a phenomenal musician. But I was reading, randomly, an article. He was quoted as saying, “When I was making Pomegranates, for example, I failed at doing the kind of ambient record I really wanted to do, but I have this thought in me. I can’t wait to make the next one. I already know the title of the next ambient record.” And I thought, that failure—and you talk about failure a lot. And I was kind of curious how this idea of failure integrated into your dialogue as a parent and how you approach the idea of failure as a parent.

AJ: Nicolás was born in a very musical house. We have a great collection of music from around the world. A lot of jazz, a lot of African contemporary music, a lot of Portuguese music, a lot of Asian music, a lot of Arabic music, a lot of folkloric music. I was really interested in all kinds of music, and it’s a huge collection. It was really—and classical music and avant-garde music. My wife was a dancer. She was studying in the Merce Cunningham school, so that’s also brought another kind of music to home, from John Cage, and so on. This was the context in which he grew up.

And obviously, I suppose it made such an effect that he ended up being a musician, but he’s totally self-made. He went to Brown University, studied comparative literature. He didn’t study music. Everything he does, he learned himself. He took a few piano lessons, and that was enough for him to decide that, “I don’t want to learn piano lessons. I want to unlearn the way music is done.” And that’s—

AZ: He’s in a field of his own. I found it interesting that both of you embraced the idea of failure. And that stuck out to me, because it’s not often that failure is taught as an attribute, and failure is taught as a possible driver for moving forward. And I felt that, if there was a connection between the two, which I don’t see from the work itself, anything beyond just that idea.

AJ: Yeah.

AZ: Of failure.

AJ: Honestly, on that point, I don’t know. He probably heard me talking about failure all the time in interviews and stuff like that, but I don’t know if he got it there or he arrived at this through his own experience. I wouldn’t be able to—

AZ: Very hard to know, but it is an interesting parallel.

Photos of Jaar upon his move to New York in 1982. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

You get to New York from Chile. What brought you to New York? Why New York? You could have gone anywhere in the world.

AJ: I wanted to be an artist. I had those two degrees. At the time, the early eighties, New York was the center of the art world—no question about it. So, I thought, I need to go and see what’s happening. I need to see art. During the dictatorship, we never had international exhibitions. We didn’t have access to art from around the world. So I was hungry. I wanted to see new art, and I thought New York was the best place to do that. That’s why we came to New York and I immediately found a job as an architect.

AZ: At SITE.

AJ: At SITE.

AZ: Very interesting firm, at that time.

AJ: I was very happy and privileged to find work there. So I worked there with James Wines for five years. And during those years, I had a double life. I worked as an architect during the day, and in the evening, I went to my studio and worked as an artist, and so the architect was financing the artist. I was perfectly happy, and I thought that this would be my life forever, because I didn’t see how I could possibly make it as an artist, and that was fine with me.

As an artist, I was already thinking as an architect. So I needed to understand the context of the art world in New York before starting to show and act. In those first years, I was an architect, a young artist, trying to find his way, but I was also an anthropologist, a cultural anthropologist. I needed to understand the New York art world. I would go to every single gallery exhibition, every museum exhibition, every lecture, every performance. I was subscribed—

AZ: Field research.

AJ: I was subscribed to every magazine. I needed to understand before acting. And after those years, I discovered two things. One, New York was an exciting place. Really, really extraordinary institutions, collections, museums, programs, blah, blah, blah. But I also discovered that New York was extremely provincial, that artists were looking at themselves, and the work was extremely self-referential. There were maybe twenty-five conflicts around the world, but you would walk around galleries and museums—you wouldn’t know about that. At all.

So that gave me an idea. I thought, Well, maybe I should bring the world to New York. It’s an incredibly ambitious project for a young kid in his twenties. But conceptually, I thought, This is what you have to do. You have to bring the world to this place, because they are too self-centric.

I had read about this gold mine in the eastern part of the Amazon, in Brazil. I had read five lines in a French magazine [Paris Match], no photographs, that described a hundred thousand men leaving their families and going to look for gold and that it was like a Dante-esque landscape of gold mining. They had opened this mine with their own hands, no machines involved. The description sounded extraordinary. And I thought, Well, I’m going to go there. So I applied for a Guggenheim [Fellowship], and I was told, “Do not apply. You’re not 30. You have to be 30 or older.” But I thought, Well, why not? I’ll apply for a Guggenheim because I want to go there.

I applied, and the miracle happened. They gave it to me. So thanks to the Guggenheim, I went to this gold mine. I spent two weeks there. I photographed the miners. I talked to them. I interviewed them and I understood what happened there. I came back and I thought, What do I do with this? And thanks to the Guggenheim, and another grant that I received from the New York State Council of the Arts at the time, I rented an entire subway station in Spring Street in SoHo, and we put posters in every advertising space in the Spring Street station in SoHo.

Jaar’s series “Rushes” (1986) displayed in the Spring Street subway station in lower Manhattan. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s series “Rushes” (1986) displayed in the Spring Street subway station in lower Manhattan. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s series “Rushes” (1986) displayed in the Spring Street subway station in lower Manhattan. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

An image from Jaar’s series “Gold in the Morning” (1986). (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

So we had eighty-one posters of the gold mine operation, the miners. And every six or seven posters, I had the price of the gold in different world markets, in Zürich, in London, in Paris, in New York. And you know, the 6 line is the one that goes down to Wall Street—

AZ: It takes you from your Upper East Side apartment to your Wall Street office.

AJ: So I wanted—

AZ: To trade gold.

AJ: Exactly. So I wanted people that trade gold to look at where is the gold coming from, to give them a human vision of what it is, really, and not this abstract notion of working on a computer and playing with this commodity. So that’s what I did and—

AZ: It was called “Cries and Whispers,” of course.

AJ: No, this is called “Rushes.”

AZ: What is “Cries and Whispers”?

AJ: It’s a work from that series, but it’s another—

AZ: Ah.

AJ: Yeah.

AZ: So the work that was in the subway is called….

Jaar in front of his installation piece “Lament of the Images” at the 2002 Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

AJ: “Rushes.” And so that work put me on the map. A lot of people saw it, and I started getting invitations. I got invited to the Venice Biennale. I got invited to Documenta. In both cases, I was the first Latin American artist they have invited. That tells you how closed the system was. It was very difficult to penetrate. At the time, an international exhibition meant artists from the U.S. or from Germany.

AZ: Yeah.

AJ: That was international. It was not the global world we are seeing now.

AZ: This idea of public and private space. So you begin in the public realm with the work. I’m curious when you first were able to translate that into the private realm, and what it felt like for you to not depend on the context of the work itself, as you did, on people’s route to work. Now you’re going to a space intentionally—a museum, an exhibition. How did you deal with that?

AJ: It’s an interesting question. The public works came out naturally because I was an architect. So I was just intervening in the city, and taking the city as a kind of laboratory. That’s why I didn’t get a gallery before the mid-nineties. I functioned as an artist in New York for fifteen years without a gallery.

AZ: Wow.

AJ: Or maybe the late eighties. I don’t remember when my first gallery show [was]. Before Lelong, I worked with a gallery called Diane Brown. I would have to look at the dates. But it was very natural for me to work in the city first. And then when the opportunity came to show inside a gallery, the dilemma—or the challenge—was, how do I work? How do I function? How do I translate all this information I have about this site, for example, the gold mines, how do they become works of art in a gallery context?

I spent a lot of time thinking about this. And I created installations that, I think, some were the perfect answer to that question, some were not as good answers, but I was trying. As I said, I was not trained as an artist and I was converting this information into art, into the gallery context. It was an interesting challenge, but slowly I got into the system.

AZ: Yeah. And you also tend to create new context within the gallery. The gallery itself is generally not the context. You seem to create an envelope within that.

AJ: Absolutely.

AZ: And some of the ways you do that I’m curious about are triptychs. You have a curiosity about triptychs. You like triptychs. You like threes. Tell me about that.

AJ: I have no idea. [Laughs] It’s the attempt to inform, and I feel that sometimes, or most of the time, a single picture doesn’t make it. So I discovered the triptych structure and I thought, Well, that helps. That helps because it’s not one, it’s not two—it’s three, and one plus one plus one is not three; it’s six or ten. So basically the triptych helps me to say more, even though I’m focusing in a very, very specific single idea. I believe in the power of a single idea.

AZ: Yeah.

AJ: So sometimes, I need more than one image to express that.

AZ: But also style doesn’t seem relevant to you. You don’t care about style, you know?

“For me, the art world—the world of art and culture—is the last remaining space of freedom, and I exercise that freedom every day.”

AJ: No, not at all.

AZ: And your work’s not connected in really formal aesthetic terms. It’s connected in this sort of socially conscious way, right? What does this freedom of style that you’ve given yourself afford you in the work?

AJ: Oh, I love it. When people see my work, they think that there are like twenty-five different artists creating these different works, because they’re all completely different. I love that freedom. For me, the art world—the world of art and culture—is the last remaining space of freedom, and I exercise that freedom every day. I’m not interested in having a signature at all, because I’m working with reality and I’m working with ideas. So basically, this reality will require this idea, and this idea will trigger this kind of work, which will be forcibly different from the previous one. That’s the nature of the things I do.

“I’m not interested in having a signature at all, because I’m working with reality, and I’m working with ideas.”

AZ: A couple minutes ago, you mentioned that, after those works about the gold mine [were first presented] in ’86, you were invited to participate in the Venice Biennale, the first artist from Latin America to be invited. And while installing your work, you had an insight that would take thirty years to realize. What was that work about? And what does it say about your perspective on the larger role art can play in people’s lives? Maybe you can just begin by the experience of going to the Biennale in ’86, as a super-young artist.

AJ: It was extraordinary because for the first time, I felt part of a community that I had felt rejected [from] before. As an artist from Chile, trying to make it in New York, I was, of course, invisible. And so suddenly, I was part of a large community and I realized, I discovered, what’s called today, the art world.

But I also discovered the systematic exclusion that existed in the art world system. I was happy to be in Venice, of course, but later, in another appearance in Venice, I did a critique of Venice, because you go to the Giardini, you have twenty-eight countries representing twenty-eight pavilions, national pavilions, and most of the world is completely excluded. And people go and see Venice and visit the Giardini and go to parties and dinners. What happens when an African artist goes to Venice, and goes to the Giardini and they ask themselves, Where is Africa? How is it possible? This is the Venice Biennale. And so, it was at first a discovery, and then slowly, I start to getting deeper into the system and I discovered its positive aspects, but also its failings. So that’s how I started really participating in the art world at large.

“We create models of thinking about the world. That’s what we do as artists.”

But as an artist, I always believed that we create models of thinking about the world. That’s what we do as artists. And we share these ideas, these models, with our audience, and sometimes these models create an effect. They have a life of their own. They circulate. And sometimes, they disappear. They have no effect. Or maybe they have a later effect you’re not even aware of. But they definitely create—in my view, and that’s what I try to do—a model of thinking [about] the world.

My best known project is from ’87, around that period where I was invited to Times Square to do this project.

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

Jaar’s piece “A Logo for America” (1987) displayed in Times Square. (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

AZ: “A Logo for America.”

AJ: Yeah, to do this project on the Spectacolor sign. And [ever] since I had moved to New York, I was disturbed by the fact that people were saying, “America this. America that.” And they were not referring to the continent, but just to the United States. And I felt that, by this daily use in the language of the word America, the continent was being erased. And I thought it was unfair and I wanted to react to that.

So I created this work. And at that moment, in ’87, it had really a semiotic impulse. Please, if you say “America,” talk about the continent. Do you want to talk about this country? Talk about the United States. Why are you mixing them up? I’m from Chile: Soy Chileno—Soy Americano—in the sense that I belong to this continent. I am American, but if I say that, people would think I’m a United States citizen, and I am not.

“Language is not innocent. Language represents a geopolitical reality.”

Anyway, I did this work in ’87. The NPR, National Public Radio, they sent a journalist to Times Square to review this work. He did it live, in front of the sign, and you could hear, in the program, someone saying, “This is illegal. Why did they let him do this?” So I thought, Well, [laughs] this is a futile attempt to correct a language. Because, of course, you quickly realize that language is not innocent. Language represents a geopolitical reality—in this case, of domination of this country, of the entire continent—and language will not change until this domination is gone. So, until today, people keep saying “America” referring to the United States, and it’s totally wrong.

AZ: You showed the piece in ’87, but then it comes back [in 2014], and this is what’s fascinating about, when works are really successful, when they transcend time, when the original intent of the work actually takes on a whole new meaning. What was it like to re-look at, and hear a re-response, and a re-contextualization and definition of the work, thirty years later?

AJ: It was fascinating. The Guggenheim purchased the work, twenty-five years later, and they put it up in Times Square again—in sixty-five screens, not in a single screen like in ’87—and the impact was phenomenal, and of course, the reading is changed. For me, it started as a semiotic project, but some people were taking it as it was an anti-Trump statement, because I was saying, “This is not America. This is not the America we know.” So, they keep committing the mistake of talking about the United States as America. And so, in Europe they were talking: “This is an anti-American propaganda project, et cetera, et cetera.” I mean, ridiculous things. But it’s fascinating to see how a work can have a life of its own. And by now, I cannot control this work, at all.

AZ: I mean in, “This is not America,” the irony of them owning—no, the domination of the America we own—that you were commenting on in the original piece…. I mean, it’s just so interesting how works can do that, especially when they contain text, because everyone can have an opinion on that text, and the language can travel.

We have fascism growing everywhere, obviously. And your work has long been looking at this idea of nationalism and fascism. What do you think is the main drive of nationalism on a human level, from having thought about it through a human lens for so long? And, despite the fact that we all shared a global pandemic, why do we have such a strong compulsion to create division as human beings—not as political systems, but as human beings?

AJ: I think, unfortunately, it’s the fear of difference. It has a racist root. Everywhere it has happened, it has a racist root, and it’s a total fear of people that is different from you—not only racially, but in terms of what people think.

Ukrainian refugees arriving at Warsaw Central Station in Poland in March 2022. (Photo: Kamil Czaiński)

So basically, once in a while, you have a dictator showing up and trying to impose their ideas, because they cannot stand that people think differently. So they’re all ideologically based or racially based. And there are wings of fascism blowing up in Europe. This has been happening for quite a while. Hungary, with Viktor Orbán, is a very good example. And, interestingly, the second after Orbán was Poland, which has also had incredible fascist connotations in the last few years. And now we are looking at Poland being the savior of Ukrainian refugees. Poland was one of the worst defenders of democracy before Ukraine.

AZ: And deeply anti-Semitic.

AJ: Absolutely.

AZ: And now, they’ve reversed that.

AJ: Now they have cleaned their image, welcoming the Ukrainians.

AZ: Yeah.

AJ: It’s absurd. It’s ridiculous. But this is happening all around the world, and it’s quite shocking to see that we haven’t learned anything. We haven’t learned anything. History keeps repeating itself. Brazilians elected Bolsonaro. They went to the [polls] to vote and they selected Bolsonaro, and they knew exactly who he was. Now, hopefully, in October, things will change. Chile itself was strongly divided and they still think, perhaps a third of the Chilean population, that it’s still pro-military. A third.

AZ: Is it fear?

AJ: It’s so many things. It’s fear. It is protection of their wealth. It’s so many things. We would have to go into the complexities of each case. It’s very complicated, but basically it’s happening all around us.

AZ: The Rwandan genocide, which is a subject you focused on deeply for six years, more than a million people were killed in a hundred days. You went there; you took pictures. You interviewed people. When you went on the initial trip, during that time, did you have a sense that there was going to be an output—that you were going to make something? And why is it that you returned to that same source material and event for six years? And did you ever get somewhere that felt final?

AJ: I went with zero preconceived notions of what I was going to do. I just wanted to witness and to express solidarity, because the world was looking the other way, and I couldn’t stand it. I thought, I need to go. I need to go. And that was the craziest thing I’ve ever done in my life. But I witnessed the genocide. I saw too many bodies to count. My body smelled [like] death for many months after I came back, and I had a block. I spent six months to a year thinking, What do I do with this? I’m not going to show these images. They won’t make any difference. What do I do?

“Six Seconds” (2000), an image from Jaar’s series “The Rwanda Project.” (© Alfredo Jaar, Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. and the artist, New York)

That’s when I came up with this program of doing exercises, philosophical essays of representation of the genocide that had been invisible in the world media. And I started, and one brought me to the other, and to the other, and to the other, and I couldn’t stop. So I developed different subjects, different ideas, different strategies, and that went on for six years—and I couldn’t get out of it. I was obsessed with it.

But after six years, I was tired. I was physically tired. I needed to get out. I was psychologically tired, and I needed to do a last project, and [make] it complete. There was an image I had taken in Rwanda, in ’94, of a girl. And it was a beautiful image. She was seen from her back. She was out of focus. She had a beautiful school dress, which is blue, and she was against a green background. It looked very much like a painting by Richter called “Betty,” of his daughter.

That image was in my mind for six years, and I couldn’t use it because it was out of focus, and I hated the fact that it was out of focus. As an architect, very rigorous, I mean, the thought of using an out-of-focus image was not in my brain, in my system. Then suddenly, in the year 2000, six years after I took that picture, I realized that perhaps it was the most important picture I had ever taken. Because I realized that, as an artist, I’m trying to tell you the story of someone else in another country, in another context. How much can I tell you? How much can I really tell you? And how much can it touch you?

So in a way, everything I do is out of focus. And then suddenly, that image became like a symbol of “The Rwanda Project.” It’s of a girl. I don’t know her name. I was going to talk to her, because I had learned she had lost her parents in the genocide, and she was visibly disturbed. I approached her, and I introduced myself. She looked at me, and she couldn’t talk. She just turned around and left. I had a little camera hanging from my neck. I spontaneously took a picture, just to mark that moment. That’s all. And that’s the one that [was] out of focus because, of course, it was very quick.

“Everything we do is out of focus when we deal with these tragedies, and we are trying to communicate them to another audience outside of ourselves.”

And I called that work “Six Seconds,” because I estimated that I didn’t spend more than six seconds with her. And I thought, But this is it. Everything we do is out of focus when we deal with these tragedies, and we are trying to communicate them to another audience outside of ourselves. She lived it in the first degree. I met her; I saw the horrors, but I lived it maybe on a second or third degree. And then, when I show it in a museum or in a gallery in New York City, we are on the fifth or sixth degree. So how much can it really contain or communicate? That’s when I thought, Well, it’s good that it is out of focus. And I accepted the fact that it was out of focus. And that was the last project, on the Rwanda project.

AZ: Alfredo, thank you so much for spending time with us today. This was really fantastic.

AJ: My pleasure. Thank you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on April 8, 2022. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity by Mimi Hannon and Tiffany Jow. The episode was produced by Emily Jiang, Mike Lala, and Johnny Simon.