Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

Adam Pendleton. (Photo: Holger Niehaus)

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Adam. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

ADAM PENDLETON: Hi, Spencer. Thanks for having me. I’m happy to be here.

SB: I’m going to start by saying that there is an eclipse happening in the middle of this interview. So I think we’ll have to take a quick pause and go see the eclipse [laughs], this once-in-every-twenty-years type of event.

AP: Yes.

SB: But I thought I would start here, actually, with a broad question about time—and it’s a question you’ve asked before. You once conducted an interview with the critic and poet Joan Retallack, [featured in your book Pasts, Futures, and Aftermaths]. It began with this question about time, and I thought it would be fun to ask you the same question [laughs]—

AP: Okay.

SB: Which is: How has time changed the way you figure yourself in relation to your work?

AP: Oh, I didn’t ask her a simple question then, did I? [Laughs] Well, I think there are different ways to approach that question. And how would I answer that? My first reaction was actually to think about it in very practical terms, of: How much time do I have to dedicate or commit myself to certain aspects of my work, of my studio?

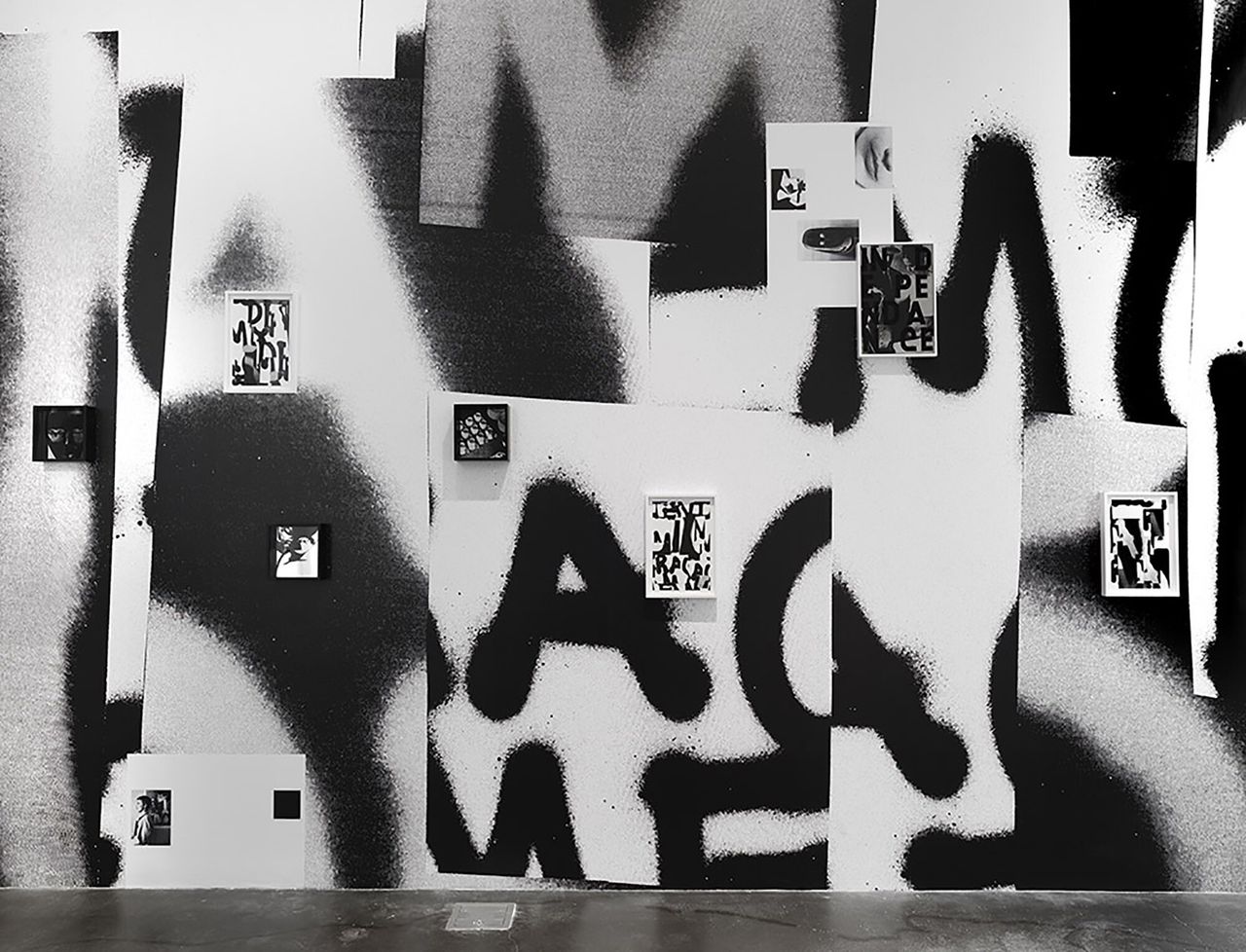

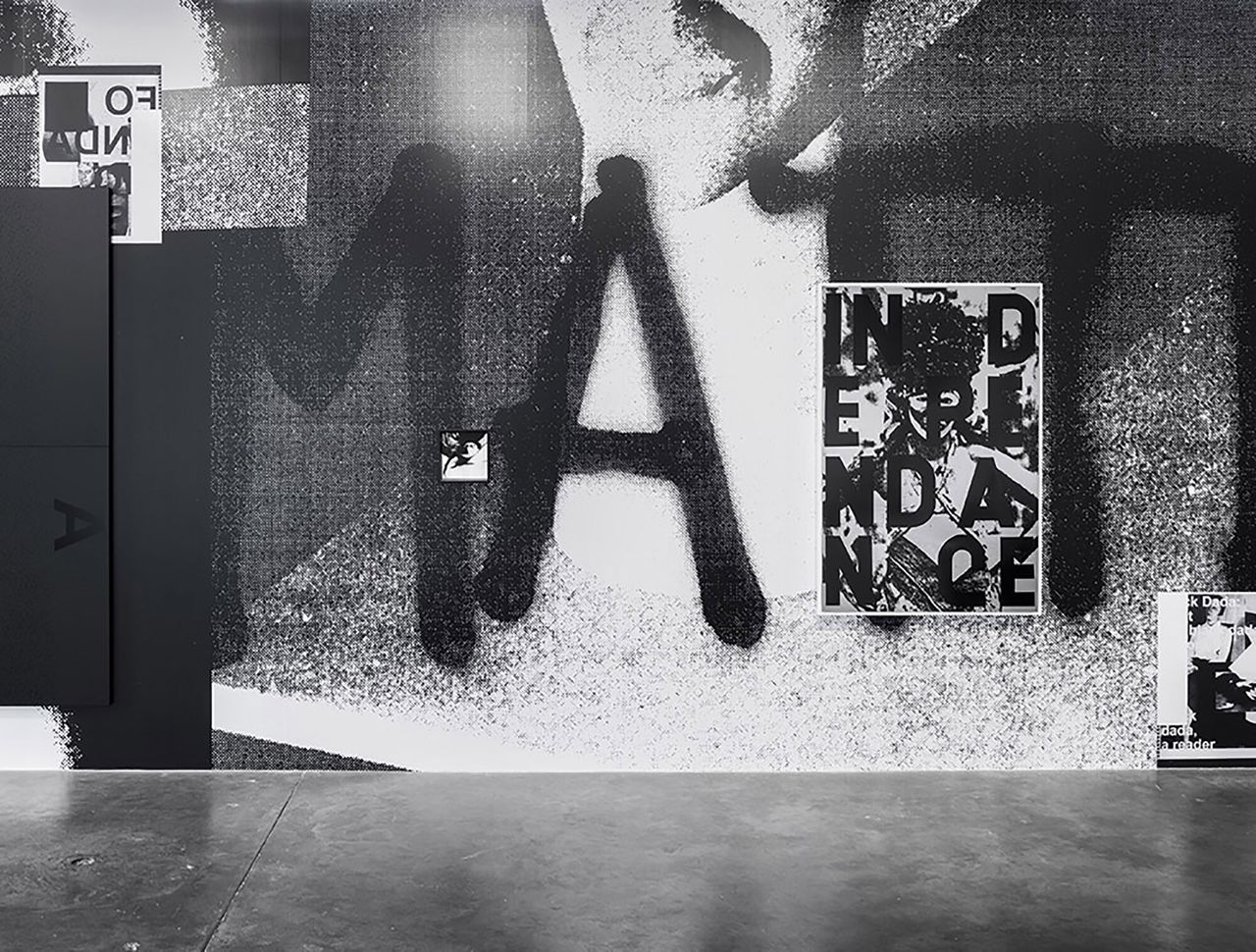

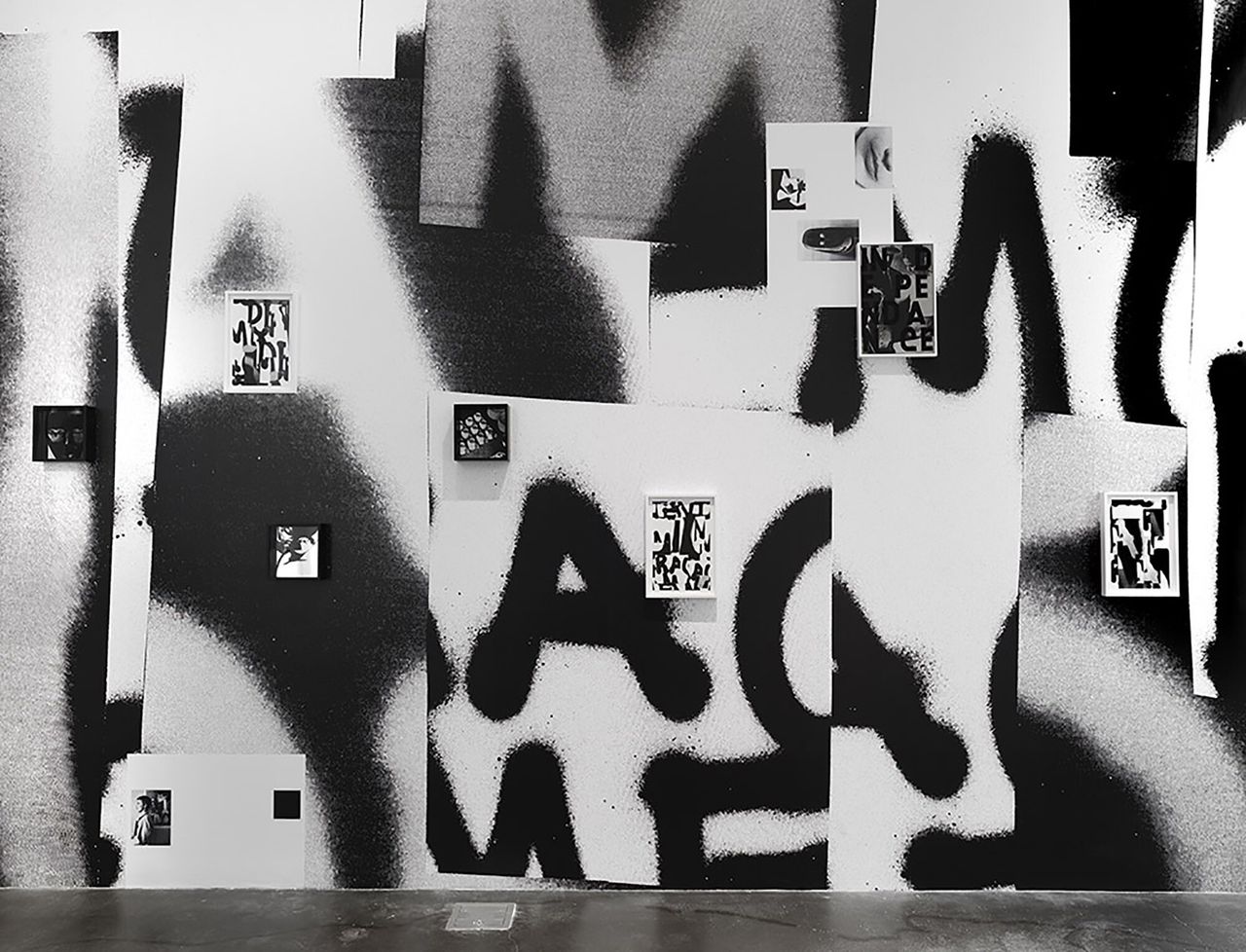

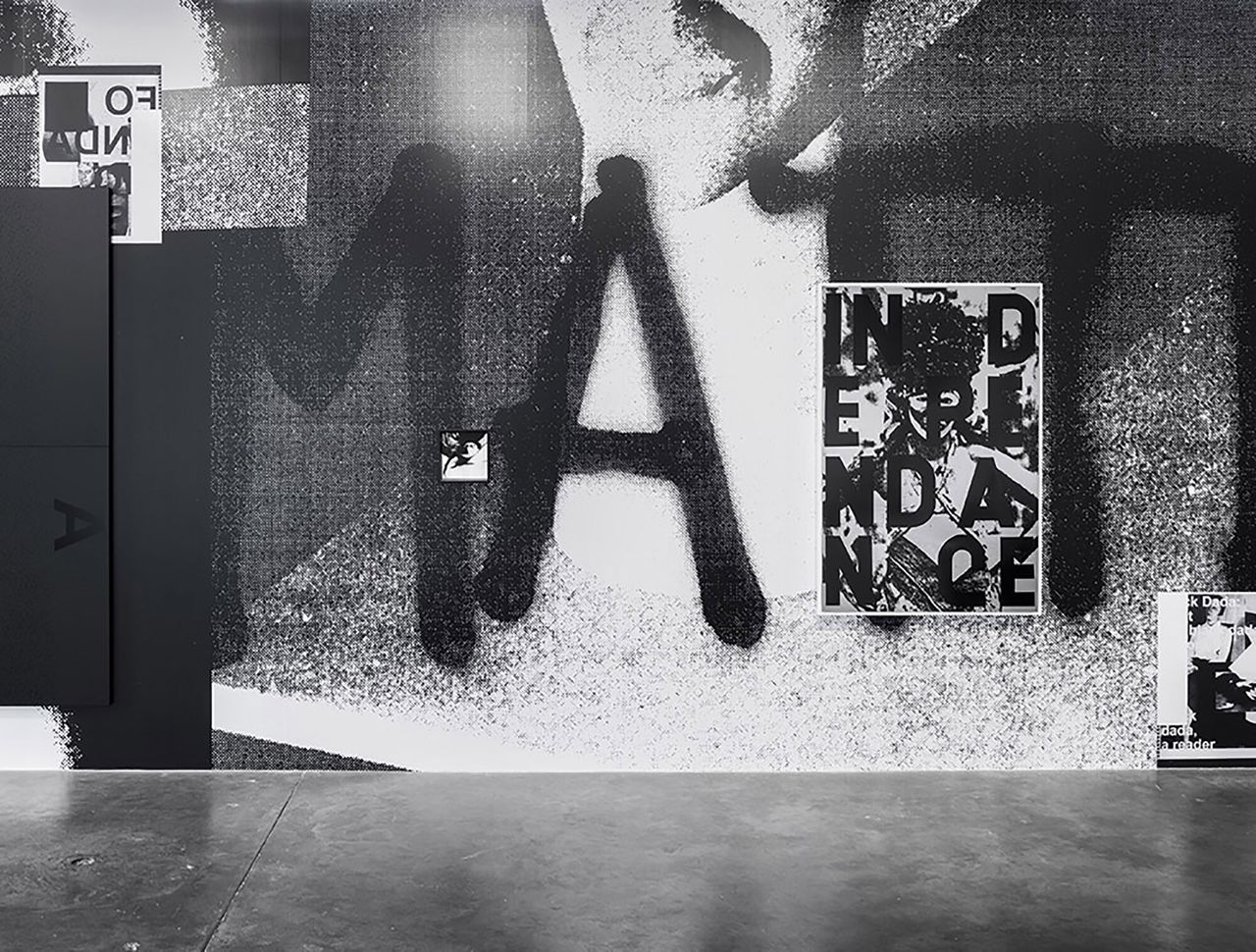

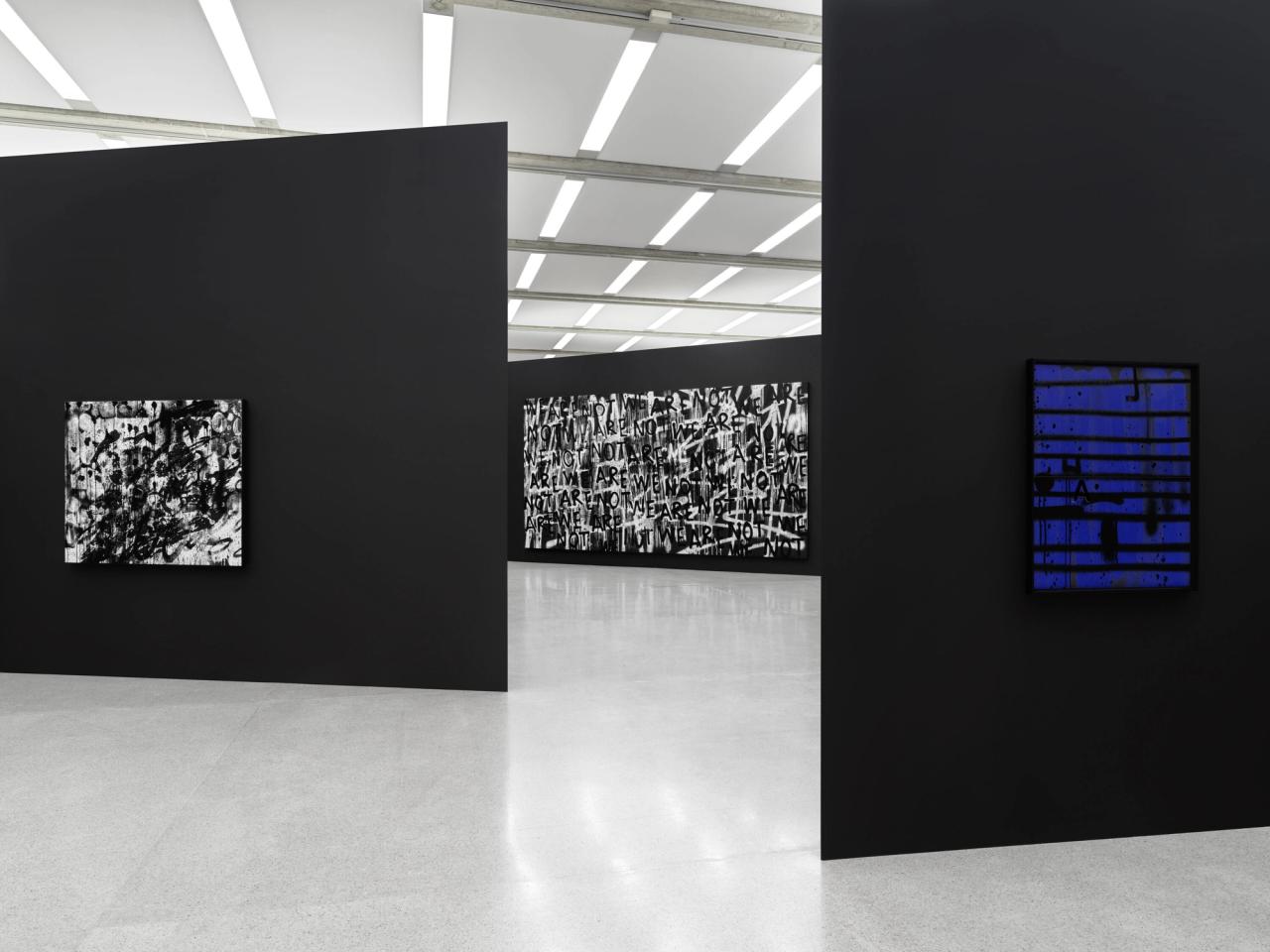

Years ago, I did a show—I think it was around 2016—called “Becoming Imperceptible,” which was very much about me disappearing or an idea of me disappearing in relationship to my work. And I almost—a little shy of ten years later—think that that has changed. If I think about becoming imperceptible in relationship to a show, and just the title of the show, “Who Is Queen?,” the show I did at MoMA, there’s obviously this query into subjecthood in relationship to authorship, in relationship to making, in relationship to identity or identities, real or imagined, possible or impossible.

I think I land in the gray, as in, I want people to think of me in relationship to my work. But I also think that’s an impossibility, because who or what are we at any given moment is in flux. It’s not fixed; it’s not stagnant. I am mutable; we are mutable. Our conception or conceptions of ourselves or of each other are mutable and changing all the time.

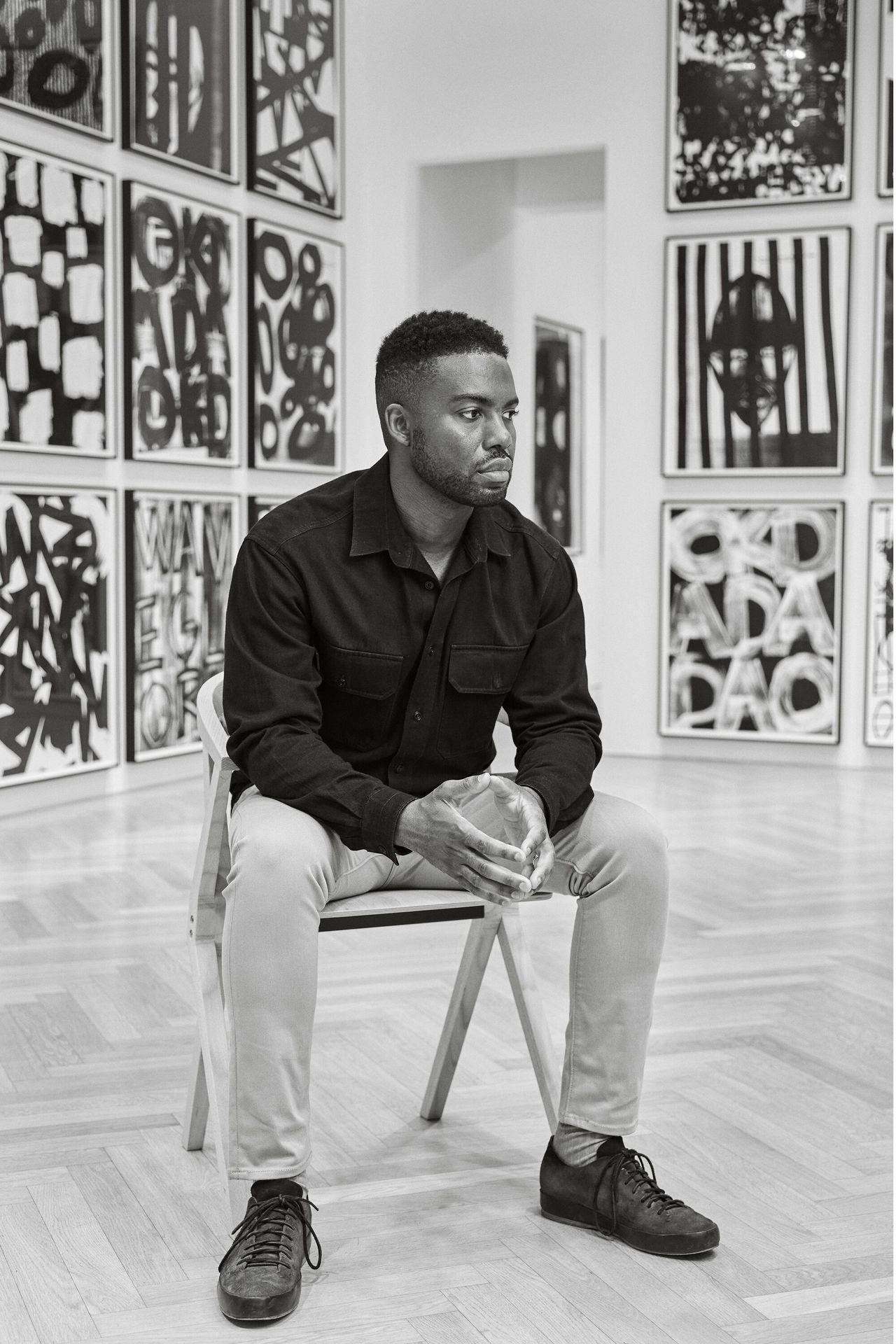

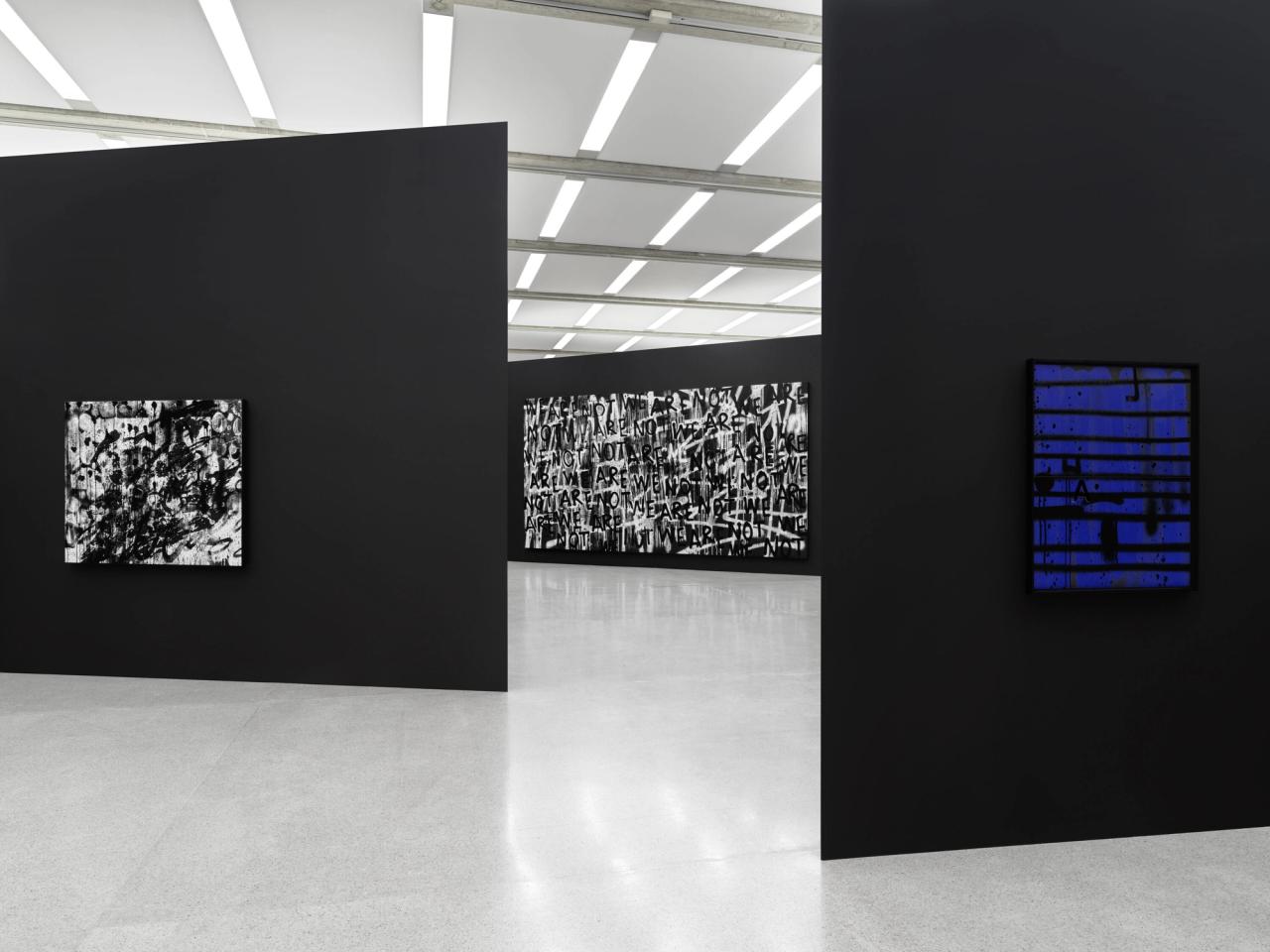

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Who Is Queen?” (2021) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

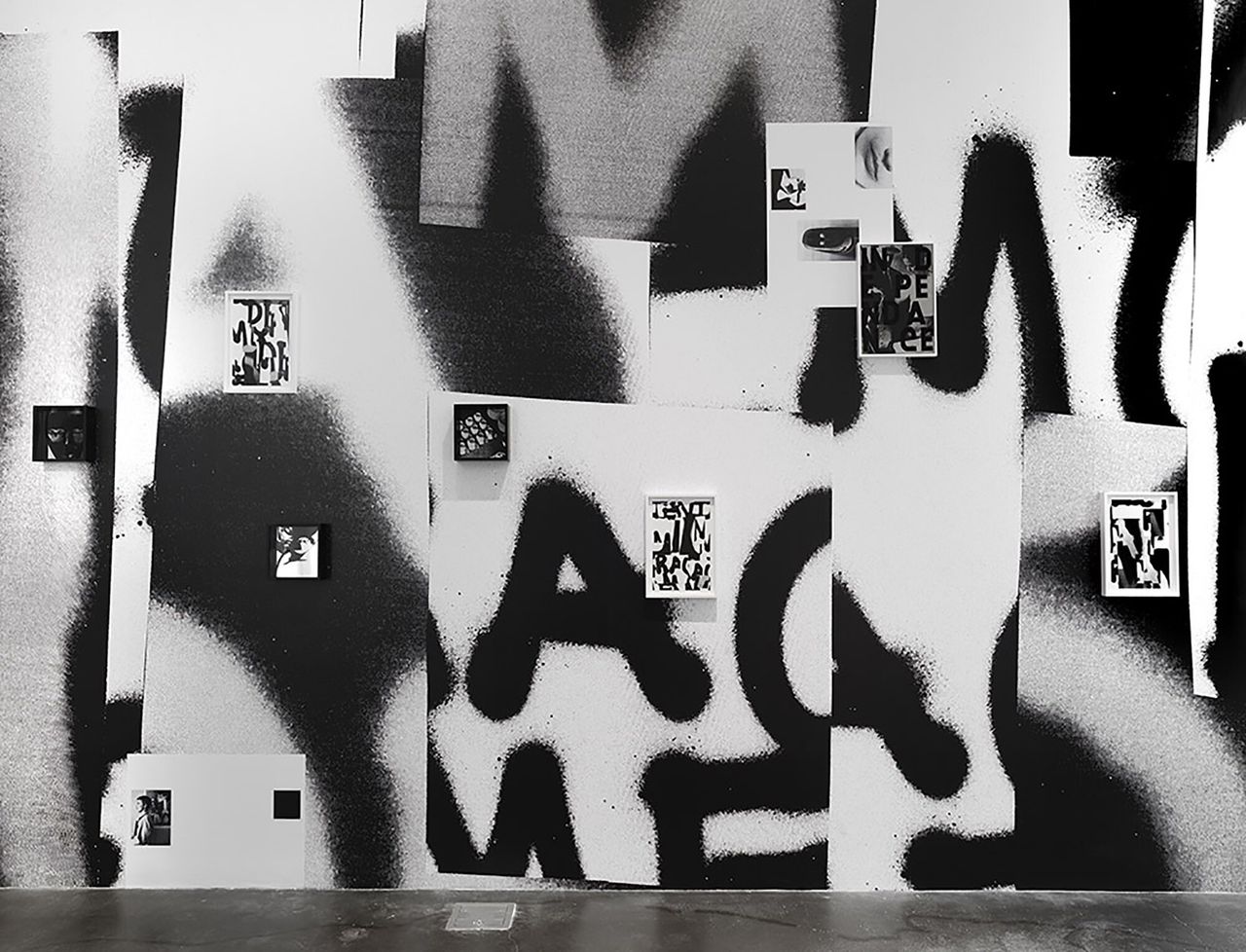

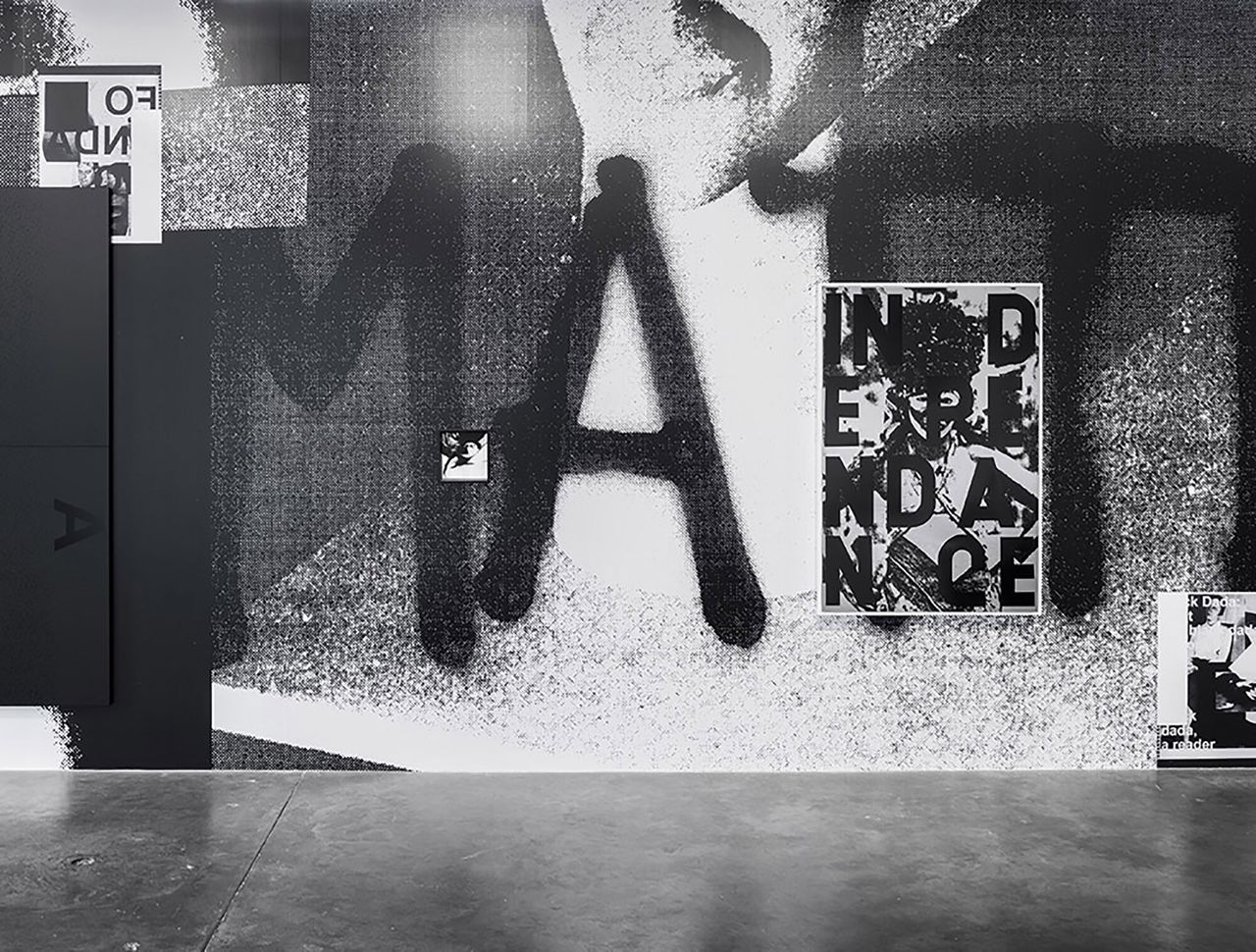

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Who Is Queen?” (2021) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Who Is Queen?” (2021) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Becoming Imperceptible” (2016) at Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

SB: I think most people also think of you immediately as this painter or filmmaker, but there’s so much else to your practice that I wanted to get into that I think is key to understanding your work. One component of that is your interviews, which—this is a selfish question as an interviewer—but you’ve published them in book form, you’ve also created these video portraits. Among others, you’ve interviewed the choreographer Ishmael Houston-Jones; the artist Joan Jonas; the artist, writer, and critic Lorraine O’Grady; and the dancer, choreographer, and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer. How do you think of these conversations in the context of what you do overall? How do you select and choose your subjects?

“Painting is a dialogic space. It’s about dialogue and communicating and being responsive—seeking potential and identifying potential in the simplest gesture or mark.”

AP: Painter, filmmaker, interviewer. [Laughs] I suppose, though, I think of myself primarily as a painter, albeit a painter who is preoccupied with how ideas exist in the world. And I think it is that preoccupation that leads me to operate slightly more discursively than the most traditional painter. So I’m interested in engaging in dialogic spaces or creating dialogic spaces. I think painting is a dialogic space. It’s about dialogue and communicating and being responsive—seeking potential and identifying potential in the simplest gesture or mark. And that’s also what a conversation is.

I have had and have people who I become very interested in or invested in speaking to, really. It’s really that simple. I think that’s also why I’m so invested in exhibition-making, because they’re also a way of creating space for conversation, for dialogue, for people to exist in relationship to each other, for ideas to exist in relationship to each other—in terms of the encounter, but also in terms of an object or the objects and how they relate to each other.

I think I often think of ideas as objects. So, in that way, let’s say the work of Joan Jonas and the ideas that are embedded in it are objects that I like to look at and study. And having a conversation with her is a very, I would argue, efficient way to engage. But it’s also mercurial; there’s also this strange alchemy that is at work, that is at play, and I’m curious about that. The films—the portraits you mentioned—document those dialogues, those interactions, and those encounters.

A lot of the portrait subjects—let’s say someone like Ishmael, or Jack Halberstam, or Lorraine O’Grady, for example—have remarked at how different each portrait is. And I offer to them when they have said that to me is, “Well, each one of you are so different, so of course, the films are different because I’m following your lead.” And to go back to painting, that’s something that interests me as a painter, is that even with these two hands, these same hands, every time I make a mark or a gesture, it’s different. It’s similar to being in conversation with someone. It’s near impossible to have the same conversation twice, which I think is endlessly fascinating.

Pendleton at work in his studio. (Photo: Jason Schmidt)

SB: One more key aspect here is what you’ve described as “poetic research,” a term I love, but wanted to dig into a little bit. Could you share a bit about what poetic research looks like and what makes that research specifically poetic?

AP: I think poetic research, if I had to quantify it, if I had to explicate [laughs], to put some language in relationship to it, it is research that is interested in the process, rather than the outcome. I know that—

SB: Well, it’s like this idea of, I think a lot of people research to an end, right?

AP: Yes.

SB: They conduct research because they’re looking for something that is almost like an answer. Whereas you’re looking for, not necessarily an answer, but things that extend beyond. There’s no final end to the research. It will endlessly go on. [Laughs]

AP: It could potentially, yes, endlessly go on. And I think that’s a part of the reason why, if you look at, again, the people who I have interviewed in a more official capacity—for a publication or to make a video portrait—I’m often having conversations with those people in different forms or formats. Because a part of what fascinates me is how the form or the format changes the interaction or the outcome. So yes, poetic research is invested in process and how process can relate or does relate to the end result, so to speak. But like you said, the results could be endless. You and I could talk all day, for example, right?

SB: Yeah. [Laughs] There was a reference I found in one of your books from Fred Moten, where he talks about poetry as a “mode of inquiry.”

AP: Yes.

SB: I like that idea, too, where it’s about inquiry. And your research, in an inverse way, fulfills that exact same thing.

AP: Yeah. That’s wonderfully generative, poetry as a mode of inquiry, indeed.

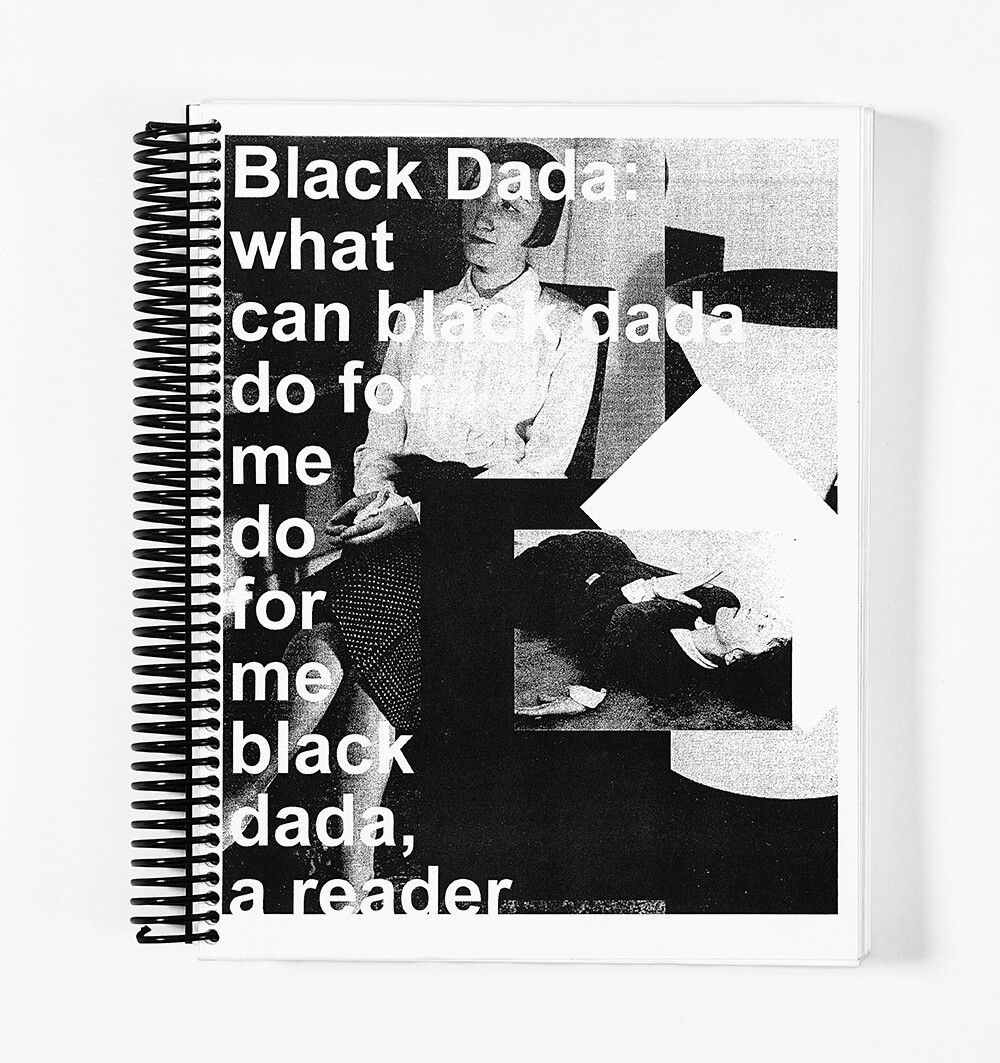

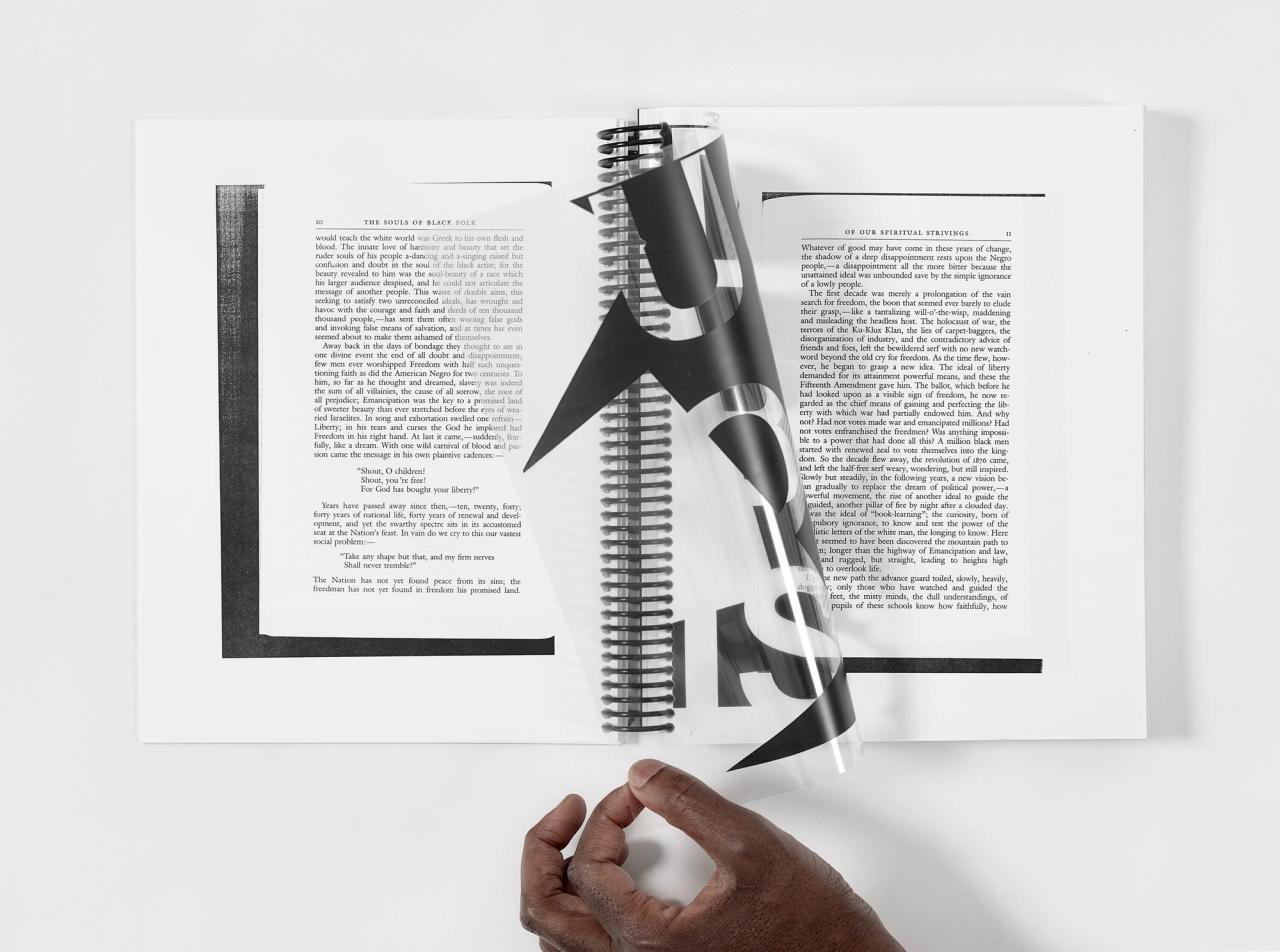

Cover of Adam Pendleton: Black Dada Reader (2017). (Courtesy Koenig Books)

SB: Reading, and beyond that, bookmaking, is the other end of this work, another essential aspect. And all the titles of your books—they’re source books really—have the word reader. [Laughs] And your books largely comprise, for those who aren’t familiar with them, these constellations, I would call them, of photocopied texts and other materials that clearly resonate with you. Reading them—or at least this was my experience—I was able to quite literally read between, beyond, into the lines of your work. For me, it was another way of understanding paintings I’d already looked at before in a totally new way, a deeper way, and maybe a less surface-level way. So, I guess, to turn this into a question, how do you view your reading in relation to your painting and to your filmmaking and to your installations?

AP: Well, I think what I’m reading affects the way I interact with and understand the world around me. It is a way of changing my understanding of the things that stimulate all of us. That can be a smell or a texture or a taste or even a temperature. If my mind has a different encyclopedic breadth to it than if I never read anything, I can have a wider array of reactions to the things I encounter and stimulate me. I can have a different—I wouldn’t say understanding—but I’m opening myself up to a wider set of possibilities, I would say, by diversifying and increasing the number of, really, [pieces of] input. How much information is stored in my mind, really, and how do I call those things, knowingly or unknowingly, at different moments—at different times?

A spread from Pendleton’s book Adam Pendleton: Black Dada Reader (2017). (Courtesy Koenig Books)

Because it’s not as though when we read something…. I don’t know about you, but I don’t remember every word. I certainly have, depending on the text, will try to. I think about [Jean] Baudrillard, this idea of “smooth traveling,” which is about: The way in which we interact with things is superficial sometimes, but inevitably deep, because everything we interact with leaves an imprint or impression on us. And so I enter textual spaces to interact, and again, give myself a deeper variety of associations and possibilities.

SB: It’s sort of bookmaking as mark-making, which is interesting.

AP: Mmm. That’s a nice way to put it. Yeah.

SB: Many artists, I think it’s worth noting, are wary of revealing their sources, or they at least often obscure them. You’re basically saying, “Here they are.” You’re indexing them for all to see. I looked at your books as archives or library bookshelves in book form. They’re like, here’s what Adam looked at, here’s what he paid attention to. And the way you mix it up with this cut-up technique too, it’s like you’re jumping shelves, but everything connects. Is that how you see it?

AP: Well, you’ve touched on something, because I think I am interested in things that are indexical. Painting is indexical, at least in the way in which I approach it. So I’m making a library of marks, for example, in the same way one makes a library of books. And you pull from that library as one perceives it to be necessary or unnecessary, and you make something out of it. So yes, that is very much so how I go about the bookmaking, at least when it comes to the readers. It is not a fast process. It’s very slow and decidedly deliberate. And a lot of the texts you see in the readers, they are texts that I have spent years with, typically. They’re not—

SB: Flippantly selected.

AP: No, they’re not one-night stands.

SB: [Laughs]

“Almost like a flavor memory, in the way the taste of something can trigger childhood, for example—that’s how these texts function for me.”

AP: These are deep and sustained relationships, with often both the individual, but also the text itself. So they’re really things that have to stay with me, almost like a flavor memory, in the way the taste of something can trigger childhood, for example. That’s how these texts function for me. They trigger something very deep and very meaningful for me, but also something I can’t quite put my finger on. I think that’s also what fascinates me.

SB: We’ll return to a few of those texts that you selected later in the interview, but for now we have to go see an eclipse. [Laughs]

AP: Okay. Sounds good.

SB: So we’ll take a break and then come back.

AP: Okay. Great.

SB: All right. We’re back from the eclipse. [Laughs]

AP: Yes.

SB: What’d you think?

AP: I’m still processing. [Laughter] My most immediate thing is the graphite color that the eclipse created. It wasn’t light or dark—it was like this cool, sharp, graphite-like color, which was pretty astonishing.

SB: I guess this brings me to the current moment. This year marks fifteen years since you performed your “Black Dada” text.

AP: Oh, wow.

SB: And this was, for the listeners who aren’t familiar with it, a poem-like script, I guess, you could call it? And in it you declared, “History is an endless variation, a machine upon which we can project ourselves and our ideas. That is to say it is our present moment.” “Black Dada” is also this theoretical framework that you’ve continuously engaged now for fifteen years, and it’s rooted in these two texts, Hugo Ball’s Dada Manifesto, from 1916, and Amiri Baraka’s poem “Black Dada Nihilismus,” from 1964. So now that I’ve got all that out of the way [laughs], what has it been like for you to engage in this “Black Dada” framework for this period of time, and what has it been like to watch it evolve, shift, morph?

“‘Black Dada’ is a contrapuntal space. It is about the way in which things exist in relationship to each other, a series of radical juxtapositions—historical, aesthetic, theoretical.”

AP: It doesn’t feel like fifteen years. Honestly, I still get nervous when people ask me what “Black Dada” is.

[Laughter]

SB: That’s why I tried to define it! [Laughs]

AP: Because my innate reaction is really, “Oh shit, what is it?” To put it very simply. [Laughter] Which is fascinating that, fifteen years on, I don’t have a packaged or concise response. And that’s what makes it important to me, is that what it is something that I grapple with every time I encounter it as an artist. And also, just when I encounter it as a question, as a query: What is it? That’s such an important part of my project, is figuring out what it is, both visually—what does it look like?—and sometimes I reside in the space of thinking that “Black Dada” is solely a visual project. It’s really trying to figure out what this looks like.

Other times, it is a more theoretical project, where I’m trying to figure out, what does it do? Or what does it mean? I think that’s to say I call upon it in different ways, so it nourishes me in different ways, at different moments. It’s alive for me, fifteen years later, which I think is, again, what is so wonderful about it. To hear someone say that to me fifteen years later—what is something?—is fascinating.

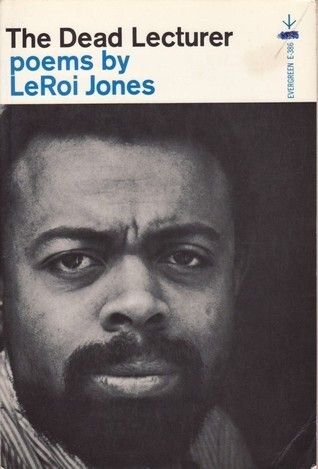

Cover of The Dead Lecturer (1964) by Amiri Baraka, published under the name LeRoi Jones. (Courtesy Grove Press)

SB: From a time perspective of “Black Dada,” you’ve described it as “about looking back at multiple things at once, many of them sort of simultaneous,” which I love. To engage history and time in this way that is destabilizing, and that is never fixed. Could you elaborate a little bit on this, your thoughts about the temporal nature of “Black Dada”?

AP: Sure. Well, I think that “Black Dada” is a contrapuntal space, so it’s many things happening at once. It is about the way in which things exist in relationship to each other, so a series of radical juxtapositions—historical, aesthetic, theoretical. It’s Amiri Baraka and Jean-Luc Godard. It’s Joan Retallack and Gertrude Stein. It’s Pope. L and Joan Jonas. I could keep going.

It’s in that way, too, about interpretation, how I interpret these ideas and why I read them as “Black Dada,” and why there’s a utility to that—me having that understanding. I will say that I think there’s a misunderstanding that exists around “Black Dada.” So Amiri Baraka, yes, the text, 1964, from The Dead Lecturer, Hugo Ball, early twentieth century, The Dada Manifesto.

It is not a conflation of those two texts. It touches on “Black Dada” as a concept of ideas that circulate or are at work in those texts, but it exists without them as well. I would probably not go as far as to say that it would exist without the gift that Baraka offered me. Just putting those two words together, Black and Dada, that certainly spurred this entire project—really just the curiosity of, why these two things? Which I don’t think he was thinking about it from—but I don’t know, maybe he was—from an art-historical standpoint. He could have been thinking about it just in terms of noise or texture, just simply, really, he just liked the way those two words existed in relationship to each other or sounded in relationship to each other.

SB: It’s interesting you’re saying that because as you were describing this, I just kept thinking about music, and what happens when sounds collide, and how through a certain sieve of sound, the way that those things are combined, in a specific way, by a specific person, you get something totally different than what the other person would do.

AP: Mm-hmm.

“System of Display, E (PLANET/Quartz)” (2022) by Pendleton. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

SB: So in a way, there is that [correlation] to music.

AP: Absolutely. And I think “contrapuntal” usually is a musical term that I apply to visual and conceptual operations or spaces. I think time is contrapuntal, and I think the reality of how we experience and move through the world is a contrapuntal experience.

SB: There’s another fifteen-year anniversary this year, which is the residency you had at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, in 2008, out of which you developed your “System of Display” paintings. You’ve returned to that museum multiple times since. So I was wondering, looking back on it now, how you view this time and engagement with that particular museum and the time you had there as an artist-in-residence?

AP: Wow, I didn’t realize there would be so much reflection. [Laughs] It’s funny, reflecting on certain moments, what they trigger. I remember when I was asked to do that residency, and I think there was a monetary component to it. I remember, frankly, actually at that time, really needing the money, as a very young artist. The relationship I’ve had with the curator there, Pieranna [Cavalchini], has been so sustaining. And I think the way in which that institution engages with living artists is so unique, because it’s not, “Oh, do the residency and get out,” or even, “Do the show and get out.” I’ve done so many different kinds of things there. I did the residency, which led to a body of work, which you accurately referenced, “The System of Display,” which I continue to make to this day, fifteen-some years later, although they have changed radically over the years.

View of Pendleton’s “Untitled (Giant Not to Scale),” as seen displayed on the façade of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston from 2019 to 2020. (Photo: Amanda Guerra. Courtesy the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum)

I was in a Joan Jonas performance, “Reading Dante,” at the Gardner Museum. So I was a part of someone else’s project at the museum. I did a show at the Gardner Museum years after the residency. I erected a banner on the façade of the museum. I did a public conversation with Lorraine O’Grady—one of our three or four proper meetings of the minds, one was at the Gardner Museum. What a rich way for the museum to facilitate different possibilities. And I think that’s a really interesting thing to think about in relationship to museums and what they do, what they can do for artists, and of course, from a critical standpoint, what they don’t do for artists. It’s really nice to think about that relationship. The impact it has had on my work has been very, very deep, actually, when you prompt me with that question. [Laughs]

SB: Yeah. Those are the only fifteen-year anniversaries I have.

AP: Okay. [Laughs]

SB: But there is a ten-year one, which is that this year marks, of course, the ten-year anniversary since you had your last gallery show, solo show, at Pace Gallery here in New York.

AP: Literally, yes.

SB: How do you think about the time between that first show and this one, “An Abstraction,” that’s about to open?

AP: It will be just over ten years. Because I think that my first show at Pace’s Gallery in New York was April 2014, and this show will open in May 2024. So just a little over ten years. And I was saying to Sam[anthe Rubell], the person who I work with at Pace, when we were looking at the work that will be included in the show, and I said to her, “I couldn’t have done these works ten years ago,” which is really interesting to think about. I’m sure it’s a thought that occurs to a lot of artists all of the time, that you look at what you’ve just done and you think to yourself, Oh, I couldn’t have done that five years ago or ten years ago.

“The reality of how we experience and move through the world is a contrapuntal experience.”

The shows are radically different. This show is very much so about painting and abstraction and color and perception—the perception of color, the perception of space, of time, of experimentation, and how all of those things relate—or possibly don’t relate—to painting, and all the things that painting can be and do. I love how Amy Sillman talks about painting as a kind of technology. I think it’s a very exciting way to think about, What is it? It’s a specific technology. So my vocabulary has changed so much as an artist in that ten-year span, and I think I’ve distilled, for this show, the critical aspects or components of how my vocabulary—my visual vocabulary—has evolved. Vocabulary is an interesting terminology when I think about applying it as a painter, as a visual artist. I was saying this to Arlene Shechet, an artist friend of mine.

SB: Who you had a show with.

AP: Yes, who I recently did a show with in Madrid. You develop these vocabularies, these visual vocabularies, and you use them, but you also want to escape them. At least you don’t want to be like a hamster; you don’t want to be on a repeat loop. You want to always push past and move on. That’s, in a strange way, what I’m doing when I’m painting. I’m always trying to push past or push beyond the last thing that I’ve done.

SB: Mmm. But still somehow kind of circling back. I wouldn’t say it’s a full repetition, but it is this back and forth.

AP: Yes. There’s an element of call and response. But I think when I say “push past,” I think people might think of sweeping changes. I am maybe speaking about it on a more molecular level—things that everyone might not notice.

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of the exhibition “Adam Pendleton x Arlene Shechet” (2024) at Pedro Cera gallery in Madrid. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

SB: [Laughs] I want to go back to painting as technology, because I find that really interesting. Immediately my mind was going to the cave paintings at Lascaux—thinking about painting as technology in that sense, across time.

AP: Mm-hmm. Absolutely. I think, well, if you specifically think about early, early, it does often suggest a series of, or set of, future possibilities for the human imagination, for making, for images, for the way in which images are understood or interpreted or encountered. So it is something, as I perceive it or as I relate to it, that pushes past or pushes forward. And the history is cumbersome and problematic and sometimes suffocating, but it can also be a liberating force as well.

“I’m always looking for visual prospects in unusual spaces.”

SB: One more “news” thing, I guess, happening at this moment is you’re working on this big show at the Hirshhorn Museum, that’s going to open next year. It’s timed to the Hirshhorn’s fiftieth anniversary. What does it mean to you to be inhabiting that space on the National Mall, and how have you been thinking about that exhibition, whatever you can share?

AP: It’s an exhibition that will primarily focus on recent paintings and drawings. Some might come from the exhibition that’s about to take place in New York. There is an aspect of the show that does touch on the National Mall, specifically Resurrection City, which was an ad hoc protest camp or city that was erected on the Mall in the sixties, and is often considered or is considered the culmination of Martin Luther King [Jr.]’s “Poor People’s Campaign.” I’m always looking for visual prospects in unusual spaces. There were these triangular structures that were erected on the Mall as a part of Resurrection City. They were dwellings, but they were also clinics or libraries. A lot of the paintings that I’ve been working on also have these triangular forms.

Archival image of Resurrection City in Washington, D.C., in 1968. (Photo: Marion S. Trikosko. Courtesy the Library of Congress)

Before I started working on these paintings, I was looking at images of Resurrection City. So now, with just a little bit of space to think and reflect, I wonder if seeing those images of these triangular structures—dwellings—was the point of origin of these triangular things in the paintings. I don’t know. But in any case, I think the Hirshhorn is such an—when we think about art and culture in the national museum of modern contemporary art—I think that’s very meaningful and exciting: What is our national museum of modern and contemporary art? I think the Hirshhorn has done an extraordinary job of being on the forefront of modern and contemporary art.

SB: It’s its own profound geometry on the Mall, too. [Laughs]

AP: It certainly is, yeah. Having to deal with that architecture is also interesting, because I think since, say, the show at MoMA, and the show that I did at MUMOK in Vienna, and the architecture people will encounter for the show at Pace, I think it has become clear to me—and I’m sure to people who have seen the last several shows that I’ve done in museums in particular know—how important the architecture is for me. But even more than that, exhibition as form. So if painting is form, drawing is form, sculpture is form—now let’s think about exhibition as form as well.

SB: Yeah. There’s something about the collective, when you put it all together within this, the architecture, this space, it’s almost, maybe it’s a bit hyperbolic to describe it as “sacred space,” but it is a form of that. There’s something that profoundly happens—and alchemy maybe is a good word here—where when you’re in that space, you feel something different than when you’re just looking at one painting.

AP:I’ve realized increasingly how uninterested I am to just put ten of the most recent things on the wall. I want the space that I create for the ten most recent things to be as meaningful as the ten most recent things. So I’m expanding the potential of the space, and in that way expanding the potential of the thought.

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

Installation view of Pendleton’s exhibition “Blackness, White, and Light” (2023) at MUMOK in Vienna. (Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery)

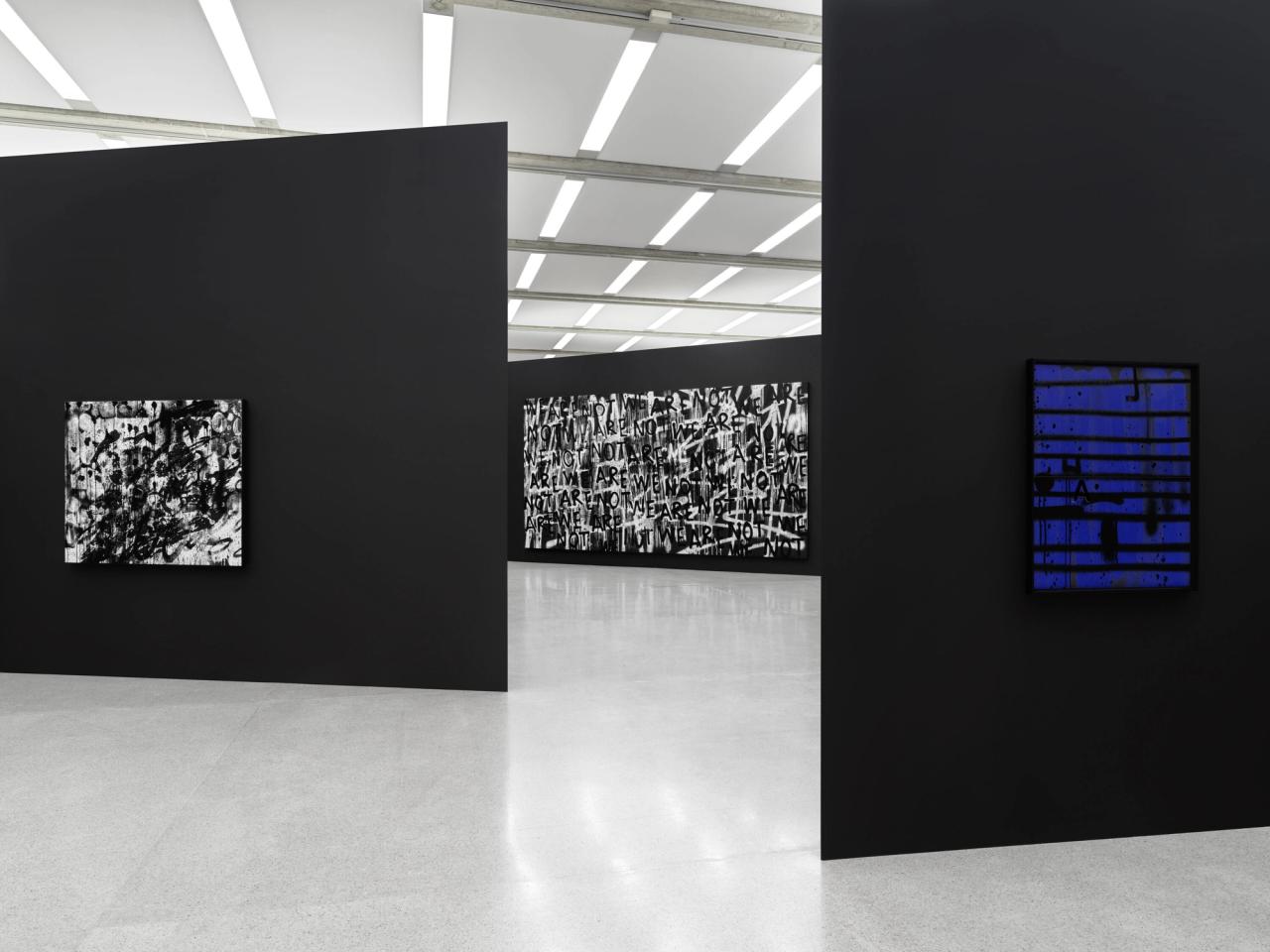

Cover of Twenty-One Love Poems by Adrienne Rich. (Courtesy The Melting Pot)

SB: Let’s go back to your childhood home here, to go back deeper into memory, in Richmond, Virginia. You’ve previously mentioned your school-teacher mother wanted to be a writer. She had all these books all over the house…. And your father, who was a contractor, is also a musician, I understand. So you grew up around poetry, literature, music, all these encounters, and you started writing poetry at a young age—plays also. Paint a picture of this environment a little bit. It sounds like your parents really instilled a sense of creativity, or at least gave you space for that creativity to unfold?

AP: Sure. Absolutely. I’m sure there are people who grew up in homes where there was no poetry, there was no music. I grew up— I would go from listening to Joni Mitchell, to Miles Davis, to Pat Metheny, to Tracy Chapman’s most recent album—so an array of musical tastes—to reading all kinds of books, Audrienne Rich, Audre Lorde. And at a young age, not when I was, say, 18, but really when I was maybe 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. It’s amazing what imprints on your mind, like Audrienne Rich’s “Twenty-One Love Poems”—“Rain on the West Side Highway,/red light at Riverside.” And I remember that particular text because it conjured an idea of New York for me, of the West Side Highway, red light at Riverside. I think it’s “Across a city from you, I’m with you” or something like this.

SB: It’s funny, you hear people talk about the formative books in their lives, but this one, to me, hearing you describe this, it’s formative beyond just the word formative. It is ingraining this form in your mind in a way.

AP: It was about a way of life, and I think art is a way of life. It’s always been a way of being in the world, a way that I make sense of the world and interact with it, and I dedicated myself to art as a way of being at a very young age.

SB: Yeah. We have to bring this up. [Laughs] You graduated from high school at age 16. You go to study art through a two-year independent study program in Pietrasanta, Italy, and then move to New York at age 18 to become an artist.

AP: Mm-hmm.

“If I called myself an artist, let’s say when I was 15 or 16, that was one thing, but when someone else says to you, ‘You’re an artist,’ that means something else.”

SB: [Laughs] And just three years later, you’re 21 and get your first solo show at a gallery. This is remarkable—does not typically happen. But looking back, I guess, how do you think about that period of time, from age 16 to 21, those years?

AP: Well, I commend my parents, because if I had a child who laid this out to me, I would say, “No, no, no, no. Bad plan.” [Laughs] So I have to commend my parents for being supportive, encouraging, and also for encouraging me to take risks. Yeah, I don’t have more to say than that. [Laughs]

SB: Tell me about this time in Pietrasanta, though. I think for those who aren’t familiar, this is the land of Michelangelo. This is stone country.

AP: It is, yes.

SB: Carrara.

AP: Yes, yes. Well, I had a series of great teachers, and during my very formative years. And the teacher that I had, Kyle Smith, in Pietrasanta. You can call yourself anything, but it’s always so much more meaningful, I think, at a certain point in your life when someone else calls you it. So if I called myself an artist, let’s say when I was 15 or 16, that was one thing, but when someone else says to you, “You’re an artist,” that means something else. And that’s what she said to me. She said, “You’re an artist.” And I think, mentally, that just opened so many doors for me, and understanding what I could do and what was possible.

SB: Did you work in stone when you were there?

AP: I did. I worked in stone. And so when she said to me, “You’re an artist,” she basically said, “You’re an artist, but you should not be working in stone.”

[Laughter]

SB: Well, there’s obviously so many places we could go with this conversation, but I thought I would take this next moment to do what you do in your books, which is this cut-up technique, and turn it into a cut-up session, where I reference some of the references that have been key for you. So there’s three of them here that are these photocopied texts from your books, and one of them is a 2013 essay, “Occupy Time,” by Jason Adams. And it looks at the Occupy [Wall Street] movement through the lens of time and space. There’s a quote I wanted to read that really—even though it was written eleven years ago—still really hits me.

“Today, the experience of time has become greatly accelerated, much more so even than just one decade ago. Whether or not one has access to the social media sites or smartphones that are increasingly turning the old, spatially defined continents into new, temporally defined telecontinents, trillions of dollars in financial transactions still speed around the globe daily.” He adds, “This ever-increasing speed of realization is a primary basis of contemporary capitalism.” Hearing it now, what does that bring up for you? Aside from the fact that we live in a super sped-up capitalist society. [Laughs]

“That’s the real Cassandra, so to speak: Do we have time to consider each other and to be considered? I think that’s increasingly getting lost.”

AP: That was ten years ago, and so it’s nerve-racking, I think, might be the best way to put it [laughs], to think that things are even more sped-up. We have less time for reflection and being considered and considerate. I think that that first part is really key, “considered”—considering each other and where you might be coming from or where I might be coming from as individuals, but also even on a geopolitical level, spatially. I think that’s maybe the real Cassandra so to speak, is do we have time to consider each other and to be considered? I think that’s increasingly getting lost. To put an optimistic spin on it, I think— [Laughs]

SB: It is a dark time.

AP: I do think this is tried and true, but when one thing is lost, something else is gained.

SB: And I do think that idea of making time to consider, and then in turn to be considerate, I think the considerate part comes from the considering. You take time to wrestle with contradiction or boredom or whatever it is you’re dealing with, and you oftentimes will come out on the other side a more considerate person. That is the reality. But if we have something pinging in our pockets every five minutes, it’s much harder to find time for that consideration.

AP: Yeah. It’s something that I ask myself often: Do I still have the ability to work outside of distraction? Even in this moment, while I’m talking to you, I’m stimulating myself with picking out different titles.

SB: We’re surrounded by books. [Laughs]

AP: Yes. The distracted mind, it’s one state of being, and so it’s like…. Sometimes I do these quasi–junk science experiments where it’s paint with music versus paint without music, or I have an idea for something that I want to paint or a medium I want to use. Like, over the weekend, I became very preoccupied with wanting to do certain things with or in watercolor. This was Saturday, and I said, “Okay, I’m going to do that tomorrow, on Sunday.” And then I didn’t do it on Sunday. I did it briefly today before coming here, and then I always—maybe you do this as well—but I thought to myself, I wonder how much this changed what I did by not doing it on Saturday when I immediately had the idea and didn’t do it on Sunday, but waited until Monday…. I’m always wondering what would have happened? “Time shapes all things,” one says, but how?

SB: The stroke’s different on Saturday than it would be on Sunday. Just like if I sit down to write a sentence, it’s going to be different on Saturday than it is on Monday.

AP: Absolutely.

SB: Yeah. Wow. Fascinating. Okay, next one. Another of your references I wanted to quote from is Toni Cade Bambara’s “What It Is I Think I’m Doing Anyhow.” She writes, “I’m attempting to blueprint for myself a merger of these two camps: the political and the spiritual.The possibilities of healing that split are exciting. The implications of actually yoking those energies and of fusing that power quite take my breath away.”

AP: Mmm.

SB: I have to say, when I read that, I just thought that that’s the experience I have looking at your paintings. And out of everything I read in your readers, this particular text really stood out to me.

AP: Yeah, that’s pretty darn good. It’s hard to respond to, frankly. “What It Is I Think I’m Doing Anyhow,” I think, kind of says everything [laughs], just the title of the piece.

SB: Alright. The third one is: In Adrienne Edwards’s essay “Some Thoughts on a Constellation of Things Seen and Felt,” from 2020, she writes about “our overwhelming visuality.” And we were just talking about the bombardment of devices, smartphones—just, the noise. But I wanted to ask, in your own work, how do you deal, grapple, contend with this overwhelming visuality that she writes about?

Pendleton in the process of creating a work with spray paint at Art Basel. (Photo: Matthew Placek)

Cover of Jazz (1992) by Toni Morrison. (Courtesy Alfred A. Knopf)

AP: Well, I think she’s speaking about it in a social, societal space or reality—realities. I am creating visual spaces that occasionally overwhelm. One of the ways that I deal with it, as an artist, is I return to visual spaces and create different relationships between them. So, to put it more plainly, I paint in layers, and often these layers are photographed. And because they’re photographed, I can often—and often do—create different relationships between these layers. I might have layer A, B, C, and D. And at first I put A and D together, and then one day I’ll put C and D together and something else emerges. I deal with or contend with this overwhelming visuality, this overwhelming visual experience—that I arguably am creating—by many returns. I go back and back and back again, to move forward. [Laughs]

SB: To finish, I thought we’d end on the subject of jazz.

AP: Mm-hmm.

SB: Your books reference and/or include interviews with a number of jazz musicians: Charles Mingus, Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, Ornette Coleman. And I also read somewhere that your favorite Toni Morrison book is Jazz. Improvisation, repetition—we’ve already talked a bit about repetition—and also this idea of “the cut.” These are all themes in jazz; they’re also things I sense in your work. And I was wondering if you could speak to this, the power of jazz and how you see it manifest or live in your work?

AP: I wish I could speak to the power of jazz, but I think jazz, like “Black Dada,” is— When someone poses that question to me, too, “What is jazz?,” I begin to stutter and fall silent, because I don’t want to quantify what it is or how I exist within it or in relationship to it. I’m driven by curiosity. I’m driven not by what I know, but what I don’t know. I don’t know what jazz is. I don’t know what “Black Dada” is. And that’s what drives me.

“I’m driven by curiosity. I’m driven not by what I know, but what I don’t know.”

SB: Beautiful. I thought we’d end on a quote from the great Ishmael Reed, which, yes, I also pulled from one of your books. And it’s, “Time is a pendulum. Not a river. More akin to what goes around comes around.”

AP: Mmm. Nice. [Laughter]

SB: Adam, thank you. This was a pleasure.

AP: Yeah. Thank you so much. I enjoyed this very much. Thank you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on April 8, 2024. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Emily Jiang, Mimi Hannon, Emma Leigh Macdonald, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Diego Mallo based on a photograph by Matthew Septimus.